Abstract

Roadkill estimates for different species and species groups are available for many countries and regions. However, there is a lack of information from tropical countries, including from Latin America. In this study, we analyzed medium and large-sized mammal roadkill data from 18 toll road companies (TRC) in São Paulo State (6,580 km of monitored toll roads), Brazil. We extrapolated these roadkill numbers to the entire system of major paved roads in the State (36,503 km). The TRC collected mammal-road- mortality data both before (2-lanes) and after (4-lanes) road reconstruction. We used the “before” data from the TRC to estimate annual mammal-road-mortality along 2-lane roads that remained public roads. Combined with the data for the new 4-lane highways, this allowed us to estimate annual mammal road mortality for all the paved roads in the State. During 10 years of roadkill monitoring along toll roads, a total of 37,744 roadkilled mammals were recorded, representing a total of 32 medium to large-sized mammal species (average number of roadkilled individuals/year = 3,774 ± 1,159; min = 1,932; max = 5,369; 0.6 individuals roadkilled/km/year). Most roadkilled species were common generalists, but there were also relatively high roadkill numbers of threatened and endangered species (4.3% of the data), which is a serious conservation concern. Most of the roadkill was reported occurred during the nocturnal period (66%, n = 14,189) and in the rainy months (October–March) (55%, n = 15,318). Reported mammal roadkill tended to increase between 2009 and 2014 (R2 = 0.614; p = 0.065), with an average increase of 313.5 individuals/year. Extrapolation of the results to the entire São Paulo State, resulted in an average estimate of 39,605 medium and large-sized mammals roadkilled per year. Our estimates of the number of roadkilled individuals can be used as one of the input parameters in population viability analyses to understand the extinction or extirpation risk, especially for threatened and endangered species.

Keywords: Roadkill, Mammal, Road, Estimate, São Paulo state, Biological conservation

Roadkill; Mammal; Road; Estimate; São Paulo state; Biological conservation.

1. Introduction

Although roads are key drivers of social-economic development, roads and traffic have a wide variety of environmental impacts, during their construction (Daigle 2010; Caliskan 2013) and their operational phase (Forman and Alexander 1998; Trombulak and Frissell 2000; Forman et al., 2003; Coffin 2007; Laurance et al., 2014). There are numerous indirect and direct negative consequences of roads, but one of the most visual and direct impacts from traffic, is the mortality of individual animals through animal-vehicle collisions (Collinson et al., 2014; Son et al., 2016; Ascensão et al., 2017).

Direct road mortality has the potential to alter the demographic structure of populations (Ascensão et al., 2016) and can result in local population sinks (Nielsen et al., 2006). The extent of these impacts depends on the characteristics of the roads, such as road width and road density, traffic volume and speed, landscape features, proximity to natural areas, and the species of interest, including their regional population size and life history (Fahrig et al., 1995; Ament et al., 2008; Frair et al., 2008; Freitas et al., 2015; Rytwinski and Fahrig 2013).

Worldwide, many studies have estimated road mortality for different species and taxa along roads with different characteristics. Sometimes researchers also aimed to identify spatial and temporal trends. For example, annual roadkill estimates include 159,000 mammals and 653,000 birds in the Netherlands (Forman and Alexander 1998), seven million birds in Bulgaria (Van der Zande et al., 1980), and five million amphibians and reptiles in Australia (Bennett 1991). In the United States, it has been estimated that 80 million birds are killed on roads each year (Erickson et al., 2005), while another study estimated that one million vertebrates per day are roadkilled (Forman and Alexander 1998).

In Brazil, there are three estimates available for vertebrate roadkill: 14.7 (±44.8) million and 475 million roadkilled vertebrates per year (Dornas et al., 2012; CBEE, 2019) and over two million mammals are estimated to be roadkilled every year (González-Suárez et al., 2018). The CBEE (Centro Brasileiro de Ecologia de Estradas) estimated that approximately 430 million small animals (<1 kg) die on Brazilian roads. The remaining 45 million are divided into medium- (40 million, e.g. Didelphis spp., Lepus europaeus, Alouatta spp.) and large-sized vertebrates (five million; e.g. Puma concolor, Chrysocyon brachyurus, Panthera onca, Tapirus terrestris, Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris).

Quantifying roadkill numbers and identifying patterns in space and time is important to justify, plan, design, and implement effective mitigation measures. However, it is hard to reliably quantify the number of roadkilled animals due to the length of the road network, high temporal and spatial variability in roadkill hotspots, and the low detectability of small and rare species (Smith and Dodd 2003; Dodd and Dorazio 2004; Santos et al., 2016). In addition, not all studies thoroughly documented the methods used to arrive at the estimates.

In this study, we estimate the direct road mortality per year of medium- and large-sized mammals (≥1 kg) along all paved roads in São Paulo State (36,503 km). We base our estimate on roadkill data collected by toll road companies along a selection of these roads (6,580 km; 18.02% of all paved roads in São Paulo state). Our study is the first well documented approach that estimates the minimum, maximum, average and median roadkill numbers for medium- and large-sized mammals in São Paulo State. This State has the highest human population density and densest road network in Brazil and is dominated by human-modified landscapes (HMLs). We also discuss the implications for species conservation, especially for threatened and endangered species as well as the relative importance of roadkill compared to other sources of unnatural mortality such as poaching.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study area

The State of São Paulo (248,209 km2) is one of 26 states in Brazil and is located in the southeast of the country (Figure 1). It is the most developed and prosperous State of the country, generating 34% of the Brazilian Gross Domestic Product. In addition, São Paulo State is home to ~44 million people, (~21% of the total population in Brazil (IBGE 2017)). In general, the State has a tropical climate with seasonal differences in temperature and precipitation (22–28 °C on average; with an annual precipitation of 1450–2050 mm), there are however regional differences in weather patterns because of elevation, slope and distance to the Atlantic Ocean (INMET, 2019).

Figure 1.

Location of the São Paulo State, Brazil, the paved road network (gray lines) and the toll roads that were monitored for roadkill (black dots represent the roadkill observations along the toll roads; the black dots are so dense that they appear as black lines in this figure).

Over the last decades, the State of São Paulo experienced rapid land use changes. This included substantial loss of Atlantic Forest and savanna (Cerrado) biomes, both of which are considered world biodiversity hotspots (Mittermeier et al., 2011). The natural vegetation was converted into pasture and croplands, urban areas (Dean 1997; Ribeiro et al., 2009, Instituto Florestal 2010; Projeto MapBiomas 2020). Additional habitat loss was associated with an expansion of the road network (33% increase in length between 1988 and 2013) (DER, 2019). The intensity by which the road network is used has also increased substantially; the number of registered vehicles increased 329% between 1998 and 2018 (DETRAN 2019).

São Paulo State has 199,371 km of unpaved and paved roads (81.7% unpaved, 18.30% paved; 0.8 km roads/km2), one of the highest road densities in Brazil (DER 2019). Starting in 1990, some Brazilian states including São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, and Minas Gerais initiated a road concession program to improve road networks that meet driver safety and other engineering standards. The program aims to transform public highways into highways managed by private toll road companies, under the condition that the toll road companies will improve the roads, including an upgrade from 2-lane to 4-lane highways. This modernization is paid for by the users through tolls (ARTESP 2019). Road concessions in São Paulo State started in 1998 and not only aimed to improve the safety and other engineering standards of roads, but also aimed to improve their environmental and social sustainability (ARTESP 2019). This strategy to improve the road network seems to have been a success. In 2018, the CNT (Confederação Nacional do Transporte) evaluated all highways in Brazil, and 18 of the 20 best highways in Brazil were located in São Paulo State, all managed by toll road companies (CNT, 2019).

The total length of paved roads in São Paulo state is 36,503 km. These roads are managed by four types of administrators: (i) public state roads are managed by Departamento de Estradas de Rodagem (DER) (2 or 4-lanes); (ii) state toll roads are managed by different private toll road companies (2 or 4-lanes); (iii) federal roads are managed by the federal transportation agency (2-lanes) and different private toll road companies (4-lanes); and (iv) municipal roads are managed by different municipalities (2-lanes only) (Table 1) (ARTESP 2019, DER 2019).

Table 1.

Total length of paved roads in São Paulo State, Brazil, per type of road administrator and the number of lanes.

| Road description | Nº lanes | Length (km) | Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Municipality paved roads (MPR_2L) | 2 | 13,376 | 36.64 |

| State paved roads (SPR_2L) | 2 | 14,500 | 39.72 |

| State paved roads (SPR_4L) | 4 | 979 | 2.68 |

| State paved toll roads (SPTR_4L) | 2 and 4 | 6,580 | 18.02 |

| Federal paved roads (FPR_2L) | 2 | 447.160 | 1.22 |

| Federal paved toll roads (FPR_4L) | 4 | 621.250 | 1.7 |

| Total | 36,503.410 | 100 |

The roads managed by DER or municipalities usually have two lanes, narrow or non-existent clear zones, frequent absence of streetlights, and relatively slow and poor medical assistance. In comparison, toll roads tend to be major four lane highways that have been reconstructed over the last few decades. These highways tend to have wide clear zones with rights-of-way that are dominated by frequently mowed in roadside verges. Also present are guard rails and median barriers (e.g. concrete Jersey median barriers) along some sections, streetlights in selected areas, and relatively fast-responseand modern medical and mechanical assistance provided through the respective toll road companies. The traffic volume and posted legal speed limit is typically higher on toll roads (varying between 80-120 km/h) than roads managed by DER or municipalities (e.g. 80–100 km/h) (ARTESP 2019).

2.2. Roadkill data

The toll road companies are responsible for the operation and maintenance of the roads they manage. This includes checking the entire length of their highways at least every three hours for stranded vehicles and drivers if they need help, which contributes to higher standards for traffic safety and free flowing traffic, debris and animal carcasses on the pavement or adjacent to it (e.g. shoulder or roadside verge). Since 2005, the toll road companies are required to remove and report animal carcasses of both wild and domestic species (required by Agência de Transportes do Estado de São Paulo – ARTESP – see http://www.artesp.sp.gov.br/). For each animal carcass, maintenance personnel are required to collect the date, time, road number or name, kilometer reference post (accurate to 100 m) or Global Positioning System (GPS) coordinates, the Portuguese common name of the species, and the status and destination of the animal carcass (e.g. whether the carcass of the animal was sent to a specific institution or if it was buried).

2.3. Species identification and corrections to the toll road roadkill data

We analyzed mammal roadkill data from 18 different toll road companies managing 6,580 km of roads. The data were collected from 2005 through to 2014 (10 years) (Table S1- see Supplementary Material). Because the roadkill data were collected by non-experts, there are errors and inconsistencies in species identification (Abra et al., 2018). Thus, we applied correction factors to the species identification by the non-experts based on Abra et al. (2018). These correction factors were based on a subset of the same roadkill data and calculated based on a comparison of the Portuguese species description provided by road maintenance personnel (non-experts) to the identification provided by experts after evaluating the photographic images provided by the toll road companies. For the corrected database, we used the scientific name of species. However, for Portuguese species descriptions that were not encountered in the subset of the data used by Abra et al. (2018), we kept the Portuguese common name and added “unconfirmed” to the species name. To improve understanding for international readers, we also included the common English name for these unconfirmed species.

Not all toll road companies collected roadkill data in all years between 2005 and 2014, mainly because the private companies entered in new toll road contracts in different years. Rather than reducing years or the road length for our roadkill estimates, we calculated average values for the missing data based on the average number of roadkilled individuals (species/year) for years that data were available for (Table S2 - see Supplementary Material). The missing data (or estimated data) comprised 13% of the total dataset. After providing estimates for the missing data for these specific toll road companies, we estimated the total number of roadkilled individuals of each species per year using the corrected identification reports of roadkill individuals.

2.4. Roadkill temporal patterns

We conducted exploratory analyses of the temporal patterns of the mammal roadkill data for the years we had data available from all 18 toll road companies (2009–2014). All roadkill records included the date when the carcass was found, but not all records included the hour of day. We distinguished between the diurnal period (from 6:00 h to 18:00 h) and the nocturnal period (from 18:01 h to 5:59 h). We also distinguished between the dry season (April–September) and the rainy season (October–March) (Alvarenga 2012).

We conducted analyses for all species combined. However, to reduce the influence from very common species that dominate the data, we conducted separate analyses after removing the observations for the most common species (i.e. species that each represented more than 20% of the roadkill data). For the records for which the species name was validated (Abra et al., 2018), we conducted an exploratory temporal analysis, including season, month, and time of day when the roadkilled animals were found. We only considered species with more than 45 records (Data S5 - see Supplementary Material). Finally, we investigated potential changes in the total number of reported roadkill per year (2009–2014) through a linear regression analysis.

2.5. Roadkill estimates

We used the roadkill database from the toll road companies to estimate roadkill numbers for the entire São Paulo State road network, corrected for the number of lanes of a road (Table 1).

To estimate mammal mortality along 2-lane public roads (DER, municipality and Federal roads), we used roadkill data collected by toll road companies before they duplicated the roads from 2 to 4-lanes. Because we extrapolated roadkill data from 2-lane toll roads to the remaining 2-lane roads in São Paulo State, we not only wanted to have an estimate for the average number of roadkilled mammals per road length unit, but we also wanted to provide a measure of uncertainty around these averages. Therefore, we divided the 2-lane toll roads into 10-km long sections (n = 27 sections), reflecting a balance between sample size and reducing the likelihood of extreme values (for more explanation see the following sections). Using relatively long sections (10 km) was also appropriate as the total road length that we were calculating an estimate for was very long (28,323 km of 2-lane roads, not managed by toll road companies) (see Table 1, Table S3 - see Supplementary Material).

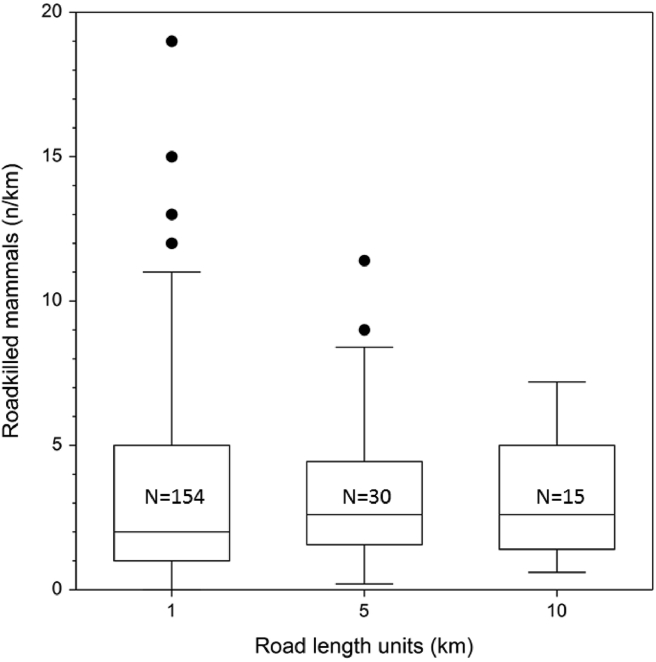

We investigated the effect of road length on the average number and variation of roadkilled mammals using data from one toll road in São Paulo State: Rodovia dos Bandeirantes (SP-348). We divided this toll road into sections of 1, 5 and 10 km, and calculated the number and variation of roadkilled mammals for the different road length units and summarized it in boxplots (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Number of roadkilled mammals in each road section of Rodovia dos Bandeirantes (SP-348). Box: middle 50% of the data (25–75 quartile); horizontal line: median; whisker boundaries: 1.5 times inter-quartile range; outliers greater than 1.5 times the inter-quartile range. N corresponds to the number of road sections.

The variation in the number of roadkilled animals per km decreased with longer road sections (Figure 2). There is a greater likelihood of extreme values, including zero observations, with short road sections compared to long ones.

None of the 27 road sections had data for lowland tapir (Tapirus terrestris), southern tiger cat (Leopardus gutullus), Brazilian guinea pig (Cavia sp.) and collared peccary (Pecari tajacu). This is partly because of their limited distribution in São Paulo State. For example, lowland tapir and collared peccary are restricted to high quality forest remnants (e.g. protected areas such as Morro do Diabo, Carlos Botelho and Serra do Mar State Parks). Other explanations for the absence of roadkill observations for some species include small body size (e.g. Brazilian guinea pig), especially when monitoring occurs from a vehicle (Teixeira et al., 2013), the fact that some species are rare (e.g. jaguar, Panthera onca; margay, Leopardus wiedii; Pampas cat, Leopardus colocola), and because rare species may be removed, legally or illegally, by others before road maintenance crews pass by. For species with limited distribution, small body size or low population density, we realize that our roadkill estimates are possibly underestimating the true number of carcasses. Other species such as hoary fox (Lycalopex vetulus) occur only in habitat patches of Brazilian savannah (Cerrado), making extrapolation to roads outside of this habitat invalid.

For 2-lane toll road roadkill data, we applied the same correction factors previously described. We calculated the number of roadkilled individuals per species for each of the 27 road sections, and then calculated descriptive statistics for each species including average, standard deviation, median, minimum, and maximum. Finally, we used these values to estimate the total number of roadkilled individuals/species/year (and associated variation) along the 2-lane roads not managed by toll roads companies.

For 4-lane roads not managed by toll road companies, we used the same values we obtained for 4-lane toll roads (per km) and multiplied them by the total length of each type of 4-lane road. The total length of 4-lane roads managed by DER and Federal Highways was 1,595 km.

We then proceeded to calculate the estimated number of mammal roadkill per species for all paved roads in São Paulo State. To do this, we summed the average, minimum, maximum and median number of roadkill per species/year of all road types assessed, i.e., Municipality, State and Federal paved roads with 2-lanes, State and Federal paved roads with 4-lanes, and State paved toll roads with 4-lanes. We also classified the species according to state, national and international conservation status, when applicable (Decreto Nº 63853/2018, ICMBio/MMA 2018; IUCN 2019).

3. Results

3.1. Species identification and correction factors for toll roads

Toll road companies recorded 37,744 medium- and large-sized roadkilled mammals (average = 3,774, SD ± 1,159 individuals, min = 1,932, max = 5,369 per year, and 0.6 animals roadkilled/km/year), totaling 32 wild species (Table 2; see Roadkill_data_Raw.csv file). Capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris, 33.4%), European hare (Lepus europaeus, 14.3%), crab-eating fox (Cerdocyon thous, 13.1%), nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus, 6.3%), porcupine (Coendou sp., 6%), six-banded armadillo (Euphractus sexcinctus, 4%), southern tamandua (Tamandua tetradactyla, 3.1%) and crab-eating raccoon (Procyon cancrivorus, 2.4%) were the most frequently reported roadkilled species, accounting for more than 80% of all records. Eight of these species are considered threatened with extinction on State, Federal or International levels: maned wolf (Chrysocyon brachyurus), hoary fox, giant anteater (Myrmecophaga tridactyla), puma (Puma concolor), black-horned capuchin (Sapajus nigritus), lowland tapir, jaguarundi (Herpailurus yagouaroundi), and southern tiger cat. Only two species in the data are considered non-native in Brazil: European hare and wild boar (Sus scrofa).

Table 2.

Numbers (total and average) and frequency (FR) of roadkilled medium- and large-sized mammals along toll roads in São Paulo State, Brazil, from 2005 to 2014, including threat categories at State (Decreto Nº 63853/2018), National (ICMBio/MMA, 2018) and World (IUCN 2019) levels.

| English Common Name | Scientific Name | São Paulo | Brazil | World | Total | Average | FR. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capybara | Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris | LC | LC | LC | 12,614 | 1261 | 33.42 |

| European hare | Lepus europaeus | IS | IS | LC | 5,406 | 541 | 14.32 |

| Crab-eating fox | Cerdocyon thous | LC | LC | LC | 4,957 | 496 | 13.13 |

| Nine-banded armadillo | Dasypus novemcinctus | LC | LC | LC | 2,375 | 238 | 6.29 |

| Porcupine | Coendou sp. | NA | NA | NA | 2,299 | 230 | 6.09 |

| Six-banded armadillo | Euphractus sexcinctus | LC | LC | LC | 1,537 | 154 | 4.07 |

| Southern tamandua | Tamandua tetradactyla | LC | LC | LC | 1,193 | 119 | 3.16 |

| Crab-eating raccoon | Procyon cancrivorus | LC | LC | LC | 906 | 91 | 2.40 |

| White-eared opossum | Didelphis albiventris | LC | LC | LC | 773 | 77 | 2.05 |

| Non identified opossum | Didelphis sp. | LC | LC | LC | 615 | 62 | 1.63 |

| Maned-wolf | Chrysocyon brachyurus | VU | VU | NT | 570 | 57 | 1.51 |

| Hoary fox | Lycalopex vetulus | VU | VU | VU | 565 | 57 | 1.50 |

| Non identified armadillo | Armadillo ni | NA | NA | NA | 563 | 56 | 1.49 |

| Dasypodidae | Dasypus sp. | NA | NA | NA | 504 | 50 | 1.34 |

| Gray brocket deer | Mazama gouazoubira | LC | LC | LC | 437 | 44 | 1.16 |

| Striped hog-nosed skunk | Conepatus semistriatus | LC | LC | LC | 290 | 29 | 0.77 |

| Giant anteater | Myrmecophaga tridactyla | VU | VU | VU | 233 | 23 | 0.62 |

| Lesser grison | Galictis cuja | LC | LC | LC | 193 | 19 | 0.51 |

| South American coati | Nasua nasua | LC | LC | LC | 169 | 17 | 0.45 |

| Brocket deer | Mazama sp. | NA | NA | NA | 163 | 16 | 0.43 |

| Puma | Puma concolor | VU | VU | LC | 152 | 15 | 0.40 |

| Coypu | Myocastor coypus | LC | LC | LC | 139 | 14 | 0.37 |

| Ocelot | Leopardus pardalis | VU | LC | LC | 137 | 14 | 0.36 |

| ∗ Unconfirmed Marmoset | NA | NA | NA | NA | 127 | 13 | 0.34 |

| ∗Unconfirmed Porcupine | NA | NA | NA | NA | 109 | 11 | 0.29 |

| Black-and-gold howler monkey | Alouatta caraya | EN | LC | LC | 103 | 10 | 0.27 |

| Marmoset | Callithrix sp. | NA | NA | NA | 82 | 8 | 0.22 |

| Black-horned Capuchin | Sapajus nigritus | LC | LC | NT | 62 | 6 | 0.16 |

| Lowland paca | Cuniculus paca | LC | LC | LC | 57 | 6 | 0.15 |

| Non identified mammal | Mammal ni | NA | NA | NA | 51 | 5 | 0.14 |

| Neotropical otter | Lontra longicaudis | VU | LC | LC | 41 | 4 | 0.11 |

| Small spotted cat | Leopardus sp. | VU/EN | NA | NA | 41 | 4 | 0.11 |

| Jaguarundi | Herpailurus yagouaroundi | VU | VU | LC | 38 | 4 | 0.10 |

| ∗Unconfirmed Sloth | NA | NA | NA | NA | 36 | 4 | 0.10 |

| ∗Unconfirmed Squirrel | NA | NA | NA | NA | 32 | 3 | 0.08 |

| Wild boar | Sus scrofa | IS | IS | LC | 29 | 3 | 0.08 |

| Naked-tail armadillo | Cabassous sp. | LC | LC | LC | 25 | 3 | 0.07 |

| ∗Unconfirmed Rodent | NA | NA | NA | NA | 20 | 2 | 0.05 |

| Non identified marsupial | Marsupial ni | NA | NA | NA | 16 | 2 | 0.04 |

| Brazilian guinea pig | Cavia sp. | NA | LC | LC | 12 | 1 | 0.03 |

| Lowland tapir | Tapirus terrestris | EN | VU | VU | 10 | 1 | 0.03 |

| ∗Unconfirmed Armadillo | NA | NA | NA | NA | 9 | 0.9 | 0.02 |

| Tayra | Eira barbara | LC | LC | LC | 9 | 0.9 | 0.02 |

| ∗Unconfirmed Giant river otter | NA | NA | NA | NA | 7 | 0.7 | 0.02 |

| ∗Unconfirmed Howler monkey | NA | NA | NA | NA | 5 | 0.5 | 0.01 |

| ∗Unconfirmed Lion Tamarin | NA | NA | NA | NA | 5 | 0.5 | 0.01 |

| ∗Unconfirmed Capuchin monkey | NA | NA | NA | NA | 4 | 0.4 | 0.01 |

| ∗Unconfirmed Puma | NA | NA | NA | NA | 4 | 0.4 | 0.01 |

| ∗Unconfirmed Primate | NA | NA | NA | NA | 3 | 0.3 | 0.01 |

| Southern tiger cat | Leopardus guttulus | VU | VU | VU | 3 | 0.3 | 0.01 |

| ∗Unconfirmed Jaguar cub | NA | NA | NA | NA | 2 | 0.2 | 0.01 |

| ∗Unconfirmed Pig | NA | NA | NA | NA | 2 | 0.2 | 0.01 |

| ∗Unconfirmed Black pencilled marmoset | NA | NA | NA | NA | 2 | 0.2 | 0.01 |

| ∗Unconfirmed Collared peccary | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1 | 0.1 | 0.00 |

| ∗Unconfirmed Marsh deer | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1 | 0.1 | 0.00 |

| ∗Unconfirmed White-eared opossum | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1 | 0.1 | 0.00 |

| ∗Unconfirmed Margay cat | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1 | 0.1 | 0.00 |

| ∗Unconfirmed Wild boar | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1 | 0.1 | 0.00 |

| ∗Unconfirmed cub | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1 | 0.1 | 0.00 |

| ∗Unconfirmed Red brocket | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1 | 0.1 | 0.00 |

| Collared peccary | Pecari tajacu | LC | LC | LC | 1 | 0.1 | 0.00 |

| TOTAL | 37,744 | 3,774 | 100 |

Legend: NA = Not applicable, LC = Least concern, VU = Vulnerable, NT = Near threatened, EN = Endangered, IS = Invasive species.

Unconfirmed animal species identification.

3.2. Roadkill temporal patterns on toll road companies

For 26,542 out of 27,573 mammal carcasses (96.26%) reported along the toll roads (2009–2014), the hour of day of the observation was reported. Most roadkill (53.45%) was reported during the nocturnal period (n = 14,189) and 46.54 % (n = 12,353) during the diurnal period (Figure 3). Excluding capybara, the most frequently observed species in the roadkill records (33.42% of all roadkill data), the proportion of roadkill reported during the day (54.58%) vs. the night (45.41%) was reversed. The peak of reported carcasses for all mammal species was between 6:00 h and 8:00 h (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Number of roadkilled medium- and large-sized mammals reported during diurnal and nocturnal periods, with and without capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris), from 2009 to 2014 in toll roads of São Paulo State, Brazil.

Figure 4.

Number of roadkilled medium- and large-sized mammals reported per hour of day, with and without capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris), from 2009 to 2014, along toll roads in São Paulo State, Brazil.

The number of mammal carcass records showed a slight seasonal variation, with more reports during the rainy season (55.55%, n = 15,318), than during the dry season (44.45%, n = 12,255). When capybaras were excluded, the difference between seasons was slightly reduced (rainy = 52.95%; dry = 47.05%).

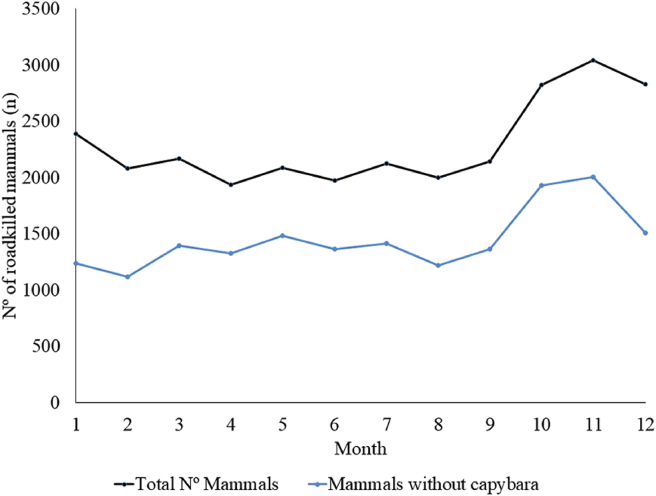

The highest number of the roadkilled mammals was reported in November (n = 3,042), followed by December (n = 2,827) and October (n = 2,821) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Number of roadkilled medium- and large-sized mammals reported per month, with and without capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris), throughout 2009 to 2014 along toll roads in São Paulo State, Brazil.

Mammal roadkill tended to increase between 2009 and 2014 (R2 = 0.614; p = 0.065), with an average increase of 313.5 individuals per year (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Number of roadkilled medium- and large-sized mammals reported per year (2009 through 2014) along the toll roads in São Paulo State, Brazil.

3.3. Roadkill estimates

The twenty-seven 10-km long road sections had 993 (min = 1, max = 116, average = 37) reported roadkilled mammals (Figure 7; Table S4 - see Supplementary Material).

Figure 7.

Number of roadkilled medium- and large-sized mammals in the twenty-seven 10-km long road sections. A) Roadkill numbers per species ranging from 0 to 13 individuals and B) Roadkill numbers per species ranging from 0 to 1. Box: middle 50% of the data (25th–75th quartile); horizontal line: median; whisker boundaries: 1.5 times inter-quartile range; outliers greater than 1.5 times the inter-quartile range. The N correspond to the number of road sections. Black dots correspond to outliers and gray dots to extreme outliers.

The total number of roadkilled mammals per year for 2 and 4-lane paved roads in São Paulo State was estimated at an average of 39,605 (min = 5,563; max = 175,963; median = 16,662) (Table 3). The average estimate show that 11% of roadkill occur along toll roads and 89% along public roads (S6 - see Supplementary Material).

Table 3.

Estimate of the number of roadkilled medium- and large-sized mammal individuals per species or taxonomic group per year for all paved roads in São Paulo State, Brazil.

| English name | Scientific name | Average | Median | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capybara | Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris | 5,435 | 4,051 | 1,793 | 15,595 |

| Crab-eating fox | Cerdocyon thous | 6,889 | 2,477 | 740 | 36,050 |

| European hare | Lepus europaeus | 7,018 | 2,464 | 788 | 29,976 |

| Nine-banded armadillo | Dasypus novemcinctus | 3,572 | 2,007 | 361 | 13,887 |

| Six-banded armadillo | Euphractus sexcinctus | 2,332 | 1,296 | 233 | 9,062 |

| Porcupine | Coendou sp. | 5,945 | 1,055 | 362 | 29,964 |

| Non Identified armadillo | Non Identified armadillo | 845 | 475 | 85 | 3,284 |

| Crab-eating raccon | Procyon cancrivorus | 857 | 499 | 139 | 3,136 |

| Non Identified armadillo | Dasypus sp. | 766 | 430 | 76 | 2,984 |

| Hoary fox | Lycalopex vetulus∗∗∗ | 457 | 338 | 84 | 1,692 |

| White-eared opossum | Didelphis albiventris | 1,113 | 340 | 121 | 5,823 |

| Opossum | Didelphis sp. | 801 | 258 | 96 | 4,041 |

| Giant anteater | Myrmecophaga tridactyla | 149 | 132 | 33 | 453 |

| Striped hog-nosed skunk | Conepatus semistriatus | 425 | 126 | 45 | 2,237 |

| Lesser grisson | Galictis cuja | 289 | 79 | 30 | 1,513 |

| Naked-tail armadillo | Cabassous sp. | 38 | 21 | 4 | 149 |

| South American coati | Nasua nasua | 100 | 41 | 26 | 402 |

| Agouti | Cuniculus paca | 39 | 18 | 8 | 144 |

| Maned wolf | Chrysocyon brachyurus | 156 | 84 | 75 | 585 |

| Non Identified mammal | NI mammal | 26 | 12 | 8 | 94 |

| Coypu | Myocastor coypus | 368 | 34 | 30 | 2,231 |

| Small spotted cat | Leopardus sp. | 78 | 6 | 6 | 554 |

| Jaguarundi | Herpailurus yagouaroundi | 74 | 5 | 5 | 553 |

| Black-and-gold howler monkey | Alouatta caraya | 50 | 15 | 15 | 304 |

| Marmoset | Callithrix sp. | 40 | 12 | 12 | 243 |

| Black-horned capuchin | Sapajus nigritus | 30 | 9 | 9 | 183 |

| Southern tamandua | Tamandua tetradactyla | 770 | 173 | 173 | 2,148 |

| Gray brocket deer | Mazama gouazoubira | 189 | 59 | 59 | 1,000 |

| Deer | Mazama sp. | 76 | 29 | 29 | 370 |

| Non Identified marsupial | Non Identified marsupial | 8 | 2 | 2 | 47 |

| Wild boar | Sus scrofa | 27 | 4 | 4 | 350 |

| Neotropical otter | Lontra longicaudis | 95 | 6 | 6 | 736 |

| Ocelot | Leopardus pardalis | 112 | 19 | 19 | 997 |

| Puma | Puma concolor | 47 | 21 | 21 | 376 |

| Southern tiger cat | Leopardus guttulus∗∗ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| Unconfirmed squirrel | ∗NA | 156 | 5 | 5 | 2198 |

| Tyara | Eira barbara∗∗ | 26 | 1 | 1 | 367 |

| Unconfirmed porcupine | ∗NA | 61 | 16 | 16 | 658 |

| Unconfirmed rodent | ∗NA | 47 | 3 | 3 | 633 |

| Unconfirmed armadillo | ∗NA | 64 | 2 | 2 | 896 |

| Collared peccary | Pecari tajacu∗∗ | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.21 |

| Lowland tapir | Tapirus terrestris∗∗ | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Brazilian guinea pig | Cavia aperea∗∗ | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Unconfirmed giant river otter | ∗NA | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Unconfirmed sloth | ∗NA | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Unconfirmed howler monley | ∗NA | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Unconfirmed marsh deer | NA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Unconfirmed capuchin monkey | ∗NA | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Unconfirmed lion tamarin | ∗NA | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Unconfirmed marmoset | ∗NA | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 |

| Unconfirmed puma | ∗NA | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Unconfirmed red brocket | ∗NA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Unconfirmed collared peccary | ∗NA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Unconfirmed white-eared opossum | ∗NA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Unconfirmed margay | ∗NA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Unconfirmed wild boar | ∗NA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Unconfirmed jaguar/puma cub | ∗NA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Unconfirmed jaguar cub | ∗NA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Unconfirmed pig | ∗NA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Unconfirmed black-pencilled marmoset | ∗NA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Unconfirmed primate | ∗NA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 39,605 | 16,662 | 5,563 | 175,963 |

Legend: Min = Minimum, Max = Maximum. Species with “∗” refers to Unconfirmed animal species which did not have reference values from Abra et al. (2018) and the Portuguese common names could not be validated by pictures into scientific names. Species with ∗∗ are considered underestimated, and species with ∗∗∗ are considered overestimated.

The mammal order that was most frequently reported as roadkill was Rodentia, followed by Carnivora and Cingulata, which together summed about 73% of all average estimate for São Paulo State (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Roadkill by taxonomic group (order) of the most frequently roadkilled medium- and large-sized mammals reported in São Paulo State, Brazil, based on the average estimate (only for orders that represented ≥0.7% of the data).

4. Discussion

4.1. Roadkill on toll roads

The roadkill monitoring program for the toll roads in São Paulo State is extensive and has a relatively consistent and frequent search and reporting effort as the entire length of the toll roads is checked at least once every three hours. Though the roadkill data demonstrate the direct road mortality for different species, it is important to emphasize that not all roadkill are recorded. Potential causes for underreporting are carcass removal by scavengers (Ratton et al., 2014; Santos et al., 2016) or people (Medici and Abra 2019), and it is almost impossible to detect and record carcasses obscured by vegetation in the right-of-way, let alone the carcasses of animals that died beyond the right-of-way (e.g. the animals get hit on the road but die off the road (Huijser et al., 2006).

Carcasses of species with some sort of economic value, such as armadillos (especially Dasypus spp.), lowland tapir, lowland paca (Cuniculus paca) and brocket deer (Mazama spp.) are sometimes removed for meat by people that travel the road. Carcasses of puma, and small spotted cats (Leopardus spp.) also have the potential to be removed (Correio do Estado 2011, G1, 2011) due to the commercial value of their fur, skull, teeth or other body parts as a trophy, amulet or medicinal use (Macdonald et al., 2010).

The ten years of roadkill monitoring revealed a chronic loss of mammal species in São Paulo State, including threatened species, which represent 4.3% of all data. Direct road mortality is considered one of the most severe impacts on threatened species according to the Brazilian National Action Plans from Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade (ICMBio), the Brazilian red list and on the Brazilian Assessment of Species Conservation Status (ICMBio 2011a; ICMBio 2011b; Medici et al., 2012; Lemos et al., 2013; ICMBio 2018).

Species such as capybara, European hare, crab-eating fox, nine-banded armadillo and porcupines, were the most frequently reported roadkilled mammals along toll roads in São Paulo State. All these species are considered common habitat generalists that thrive in most human-modified landscapes (HMLs) (Lyra-Jorge et al., 2008; Bueno et al., 2013; Freitas et al., 2015; Magioli et al., 2016; Ascensão et al., 2017; Azevedo et al., 2018; Bovo et al., 2018).

A high loss of common species is also ecologically relevant as they might severely affect ecosystem services provided by them. Armadillos, for example, are important ecosystem engineers through their burrows (Desbiez and Kluyber 2013) and also provide important other ecosystem services (Rodrigues et al., 2020).

European hare is an invasive species and has succeeded in colonizing and expanding its distribution in Brazil (da Rosa et al., 2020). The species is widespread in São Paulo State, and was one of the most frequently reported roadkilled mammals in our study.

The changes in landscape composition and structure, partially associated with the construction of transportation corridors, tend to affect wildlife species that are relatively sensitive to the loss of habitat and other resources (Gascon et al., 1999; Fahrig 2003; Lyra-Jorge et al., 2008). Human disturbance in the landscape favors generalist species that are capable of exploiting new environments such as agricultural crops or disturbed habitats (Downes et al., 1997, Magioli et al., 2019a, b). Capybaras account for more than one third of all reported roadkill, stressing the urgency of management actions that limit the access of this particular species to roads. Capybara is the largest living rodent species, averaging about 50–90 kg in HMLs in São Paulo State (Ferraz et al., 2005, Marcelo Labruna, Pers. Comm). This species is now the most common mammal in HMLs in São Paulo State, especially in landscapes dominated by sugarcane crops in Southeastern Brazil (Verdade and Ferraz 2006; Ferraz et al., 2007). Their abundance is related to food availability and a decline in natural predators (e.g. pumas) (Ferraz et al., 2007; Nielsen et al., 2015; Verdade et al., 2012; Bovo et al., 2016). The impact of collisions with capybara on human safety and vehicle repair costs is extensive (Huijser et al., 2013).

Abra et al. (2019) showed that the number of animal-vehicle collisions is increasing in São Paulo State. Although marginally significant, our current study also showed a trend of an increase of 313 reported mammal carcasses per year along the toll roads. An increase in traffic volume, new roads in remote areas, and increasing population size of species that thrive in HMLs, are factors that are likely to contribute to the increase in roadkill (Abra et al., 2019).

4.2. Temporal patterns

Most mammal carcasses were reported during the night, from dusk to midnight, but also from dawn to 9:00 h, similar to temperate regions (Groot Bruinderink and Hazebroek 1996; Huijser et al., 2008). This pattern is also consistent with animal-vehicle crashes (wild and domesticated mammals) in São Paulo State (Abra et al., 2019). We believe that the time day of the roadkill reported is mainly related to activity period of the species (most are nocturnal and crepuscular) and the traffic volume. Unfortunately, we could not obtain data on traffic volume for all roads in this study, but we suspect high traffic volumes from 6:00 h to 8:00 h am, which contributes to the high number of roadkilled animals in the early morning (Pedro Romanini - ARTESP, Pers. Comm). The roadkill data do not allow for disappearance rate analyses as only roadkill reports are available, and each report is always associated with the removal of the carcass. The time of day of the reports is influenced by the ability to see the carcasses. It is possible that the observers see capybara all night long because of their large body size. We suspect that the difficulty of detecting carcasses in the dark mainly applies to small species. This would then result in the observers to only start seeing these carcasses when it gets light in the morning. Thus, especially small animal species may have been hit earlier during the dark hours rather than at first light, rather than at the hour of the carcass report.

The number of roadkilled individuals for all the mammal species combined during the rainy season was slightly higher than in the dry season. For herbivores (grazers and browsers), the rainy season increases the availability of green vegetation, including areas adjacent to roads because of runoff. This can increase the exposure of the animals to traffic. Moreover, the constant mowing and cutting of vegetation in the rights-of-way, stimulates regrowth which can attract herbivores. Along toll roads, most of the space in the rights-of-way is dominated by grasses (Poacea species). This is an attractive food source, available all year around, for species such as capybara, coypu (Myocastor coypus), European hare and brocket deer (Richard and Juliá 2001; Borges and Colares 2007; Puig et al., 2007; Colares et al., 2010).

In HMLs, the first peak of activity of capybaras is around 5:00–6:00 h and the second peak around 18:00–21:00 h (Lopes et al. Accepted). This activity pattern matches our results, as the roadkill rate of capybaras was highest around dawn and dusk.

During the dry season, some species tend to expand their habitat range in search of food and water sources, which implicates higher movement rates and movements over greater distances, and thus an increase in road crossings (Silveira et al., 2010). Roadkill was higher during the dry months for certain species in our study, mainly for carnivores such as crab-eating fox, maned-wolf and ocelot. Lemos et al. (2011) also found that the number of roadkilled crab-eating foxes and hoary foxes were higher during the dry season.

4.3. Roadkill estimates for São Paulo state

The wide variation in species roadkilled per road section along the Rodovia dos Bandeirantes (SP-348) was expected because this highway crosses different types of landscape, from natural to urban areas, which directly influences species richness and abundance (Freitas et al., 2015; Ascensão et al., 2017). Despite choosing a long length for the road sections (10-km long), which reduced variation in roadkill numbers, we still had considerable variation between the number of roadkilled individuals for each species. More importantly, along the twenty-seven 10-km long road sections certain species were entirely absent as roadkill. This included lowland tapir, southern tiger cat, Brazilian guinea pig and collared peccary, all of which are present in the State. The absence of observations for certain species along the road sections resulted in an underestimate of the number of roadkilled individuals for these species.

Even though 27 sections (each 10 km long) is a decent sample size, a higher sample size would have resulted in better estimates, and a reduction of zero observations for some species.

For this study, we believe that the main limitation is not the methodology but the lack of roadkill observations from 2-lane roads managed by DER and roads managed by municipalities. Nonetheless, we believe that our roadkill estimates for São Paulo State can be useful and should allow environmental and transportation agencies improve their planning, regulations, and investments in effective mitigation measures aimed at addressing the negative effects of roads on wildlife (Rytwinski et al., 2016).

The roadkill estimate for hoary foxes needs to be interpreted with great caution. This species is the only truly endemic carnivore of the Cerrado biome of Brazil (Jácomo et al., 2004). All validated records of hoary fox by Abra et al. (2018) were inside the limits of the Cerrado biome in the State of São Paulo, but the estimates in this study were extrapolated to the roads in the entire State, including areas outside of the Cerrado biome. This likely resulted in an overestimate of the number of individual hoary foxes roadkilled in the State of São Paulo.

4.4. Implications for biological conservation

There is a general lack of information on the unnatural mortality of mammals in the State of São Paulo and in the rest of Brazil. Poaching (illegal hunting), for example, is one of the sources of unnatural mortality. Between 2006 and 2015, the Environmental Police from São Paulo State recorded 1,913 poaching events in São Paulo State, in which 9% of the cases involved capybara (n = 173), 4.6% nine-banded armadillo (n = 94) and 1.1% lowland paca (n = 22) (Azevedo 2018). Obviously, the official numbers of poaching for São Paulo State are a severe underestimation because it depends on having caught poachers red-handed. Even with these limitations, the number of medium- and large-sized mammals killed by poachers is likely to be much lower than the number of roadkilled mammals. In addition, roadkill affects almost all species whereas poachers tend to target specific species (Cullen et al., 2000; Fernandes-Ferreira and Alves 2017). Another perspective on the impact of roadkill on an endangered species comes from a radio collar study on maned wolves. Of the seven maned wolves monitored in northeast of São Paulo State (Lobos do Pardo Project) between June 2018 and June 2019, one individual was roadkilled (Rogerio Cunha - ICMBio, Pers. Comm).

5. Final considerations

When planning for and implementing conservation actions, it is important to have a good understanding of where our actions are likely to have the greatest benefit. While habitat loss, reductions in habitat quality, and habitat fragmentation are main drivers that can cause extirpation of a species in an area, it is also important to know about the causes of direct mortality and the chronic loss of individuals. We not only need enough habitat, good habitat quality, and well-connected habitat. We also need the animals that live in this habitat to stay alive. This is where our roadkill estimates have a role. We now have a good idea of the magnitude of direct road mortality for medium- and large-sized mammal species in São Paulo State. Combined with the results from other studies that document other sources of unnatural mortality (e.g. poaching), parameters related to natural demographics, and the results from population viability analyses, we can formulate more effective conservation strategies. Based on the limited information available, it seems that direct road mortality is likely to be a much bigger problem than wildlife poaching. This does not mean that wildlife poaching should not be fought or taken seriously, but it does mean that direct mortality as a result of collisions with vehicles is likely a very serious issue, and that measures aimed at reducing these collisions are needed as part of a more comprehensive conservation strategy.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

F.D. Abra and M.P. Huijser: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

M. Magioli, A.A.A. Bovo and K.M.P.M de Barros Ferraz: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

K.M.P.M de Barros Ferraz was supported by Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (308632/2018-4).

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Wildlife Ecology, Management and Conservation Lab (LEMaC), Forest Science Department (Escola Superior de Agricultura “Luiz de Queiroz”, Universidade de São Paulo), the Interdisciplinary Program in Applied Ecology (PPGI-EA), the São Paulo Research Foundation (Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo) and we also thank ARTESP to provide roadkill data from toll road companies in São Paulo State. This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - Brasil (CAPES) - Finance Code 001 (AAAB), and the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) (productivity fellowship to KMPMBF; processes 308632/2018-4).

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- Abra F.D., Huijser M.P., Pereira C.S., Ferraz K.M. How reliable are your data? Verifying species identification of road-killed mammals recorded by road maintenance personnel in São Paulo State, Brazil. Biol. Cons. 2018;225:42–52. [Google Scholar]

- Abra F.D., Granziera B.M., Huijser M.P., de Barros K.M.P.M., Haddad C.M., Paolino R.M. Pay or prevent? Human safety, costs to society and legal perspectives on animal-vehicle collisions in São Paulo state, Brazil. PloS One. 2019;14(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0215152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarenga L.A. Precipitação no sudeste brasileiro e sua relação com a Zona de Convergência do Atlântico Sul. Rev. Agrogeo. 2012;4(2) [Google Scholar]

- Ament R., Clevenger A.P., Yu O., Hardy A. An assessment of road impacts on wildlife populations in US National Parks. Environ. Manag. 2008;42(3):480. doi: 10.1007/s00267-008-9112-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ARTESP . Agência de Transporte do Estado de São Paulo; 2019. http://www.artesp.sp.gov.br Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Ascensão F., Mata C., Malo J.E., Ruiz-Capillas P., Silva C., Silva A.P. Disentangle the causes of the road barrier effect in small mammals through genetic patterns. PloS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ascensão F., Desbiez A.L., Medici E.P., Bager A. Spatial patterns of road mortality of medium–large mammals in Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil. Wildl. Res. 2017;44(2):135–146. [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo O.A.B. São Carlos; São Paulo: 2018. Uma avaliação dos padrões de caça do Estado de São Paulo. Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Conservação de Fauna, para obtenção do título de Mestre Profissional em Conservação de Fauna da Universidade Federal de são Carlos. [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo F.C., Lemos F.G., Freitas-Junior M.C., Rocha D.G., Azevedo F.C.C. Puma activity patterns and temporal overlap with prey in a human-modified landscape at Southeastern Brazil. J. Zool. 2018;305(4):246–255. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett A.F. Roads, roadsides and wildlife conservation: a review. Nat. Conserv. 1991;2 the role of corridors. [Google Scholar]

- Borges L.D.V., Colares I.G. Feeding habits of capybaras (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris, Linnaeus 1766), in the ecological reserve of taim (ESEC-Taim)-south of Brazil. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2007;50(3):409–416. [Google Scholar]

- Bovo A.A.A., Ferraz K.M.P., Verdade L.M., Moreira J.R. Biodiversity in Agricultural Landscapes of southeastern Brazil. Sciendo Migration; 2016. 11. Capybaras (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris) in anthropogenic environments: challenges and conflicts; pp. 178–189. [Google Scholar]

- Bovo A.A.A., Magioli M., Percequillo A.R., Kruszynski C., Alberici V., Mello M.A.…Ramos V.N. Human-modified landscape acts as refuge for mammals in Atlantic Forest. Biota Neotropica. 2018;18(2) [Google Scholar]

- Bueno C., Faustino M.T., Freitas S. Influence of landscape characteristics on capybara roadkill on highway BR-040, southeastern Brazil. Oecol. Aust. 2013;17(2):320–327. [Google Scholar]

- Caliskan E. Environmental impacts of forest road construction on mountainous terrain. Iran. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 2013;10(1):23. doi: 10.1186/1735-2746-10-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CBEE . 2019. Centro Brasileiro de Ecologia de Estradas.http://cbee.ufla.br/portal/atropelometro/ Available at: [Google Scholar]

- CNT . 2019. Confederação Nacional de Transporte.https://www.cnt.org.br/home Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Coffin A.W. From roadkill to road ecology: a review of the ecological effects of roads. J. Transport Geogr. 2007;15(5):396–406. [Google Scholar]

- Colares I.G., Oliveira R.N., Liveira R.M., Colares E.P. Feeding habits of coypu (Myocastor coypus Molina 1978) in the wetlands of the Southern region of Brazil. An Acad. Bras Ciências. 2010;82(3):671–678. doi: 10.1590/s0001-37652010000300015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collinson W.J., Parker D.M., Bernard R.T., Reilly B.K., Davies-Mostert H.T. Wildlife road traffic accidents: a standardized protocol for counting flattened fauna. Ecol. Evol. 2014;4:3060–3071. doi: 10.1002/ece3.1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correio do Estado . 2011. Onça Atropelada Tem Patas Arrancadas. Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Cullen L., Jr., Bodmer R.E., Pádua C.V. Effects of hunting in habitat fragments of the Atlantic forests, Brazil. Biol. Cons. 2000;95(1):49–56. [Google Scholar]

- da Rosa C.A. Neotropical alien mammals: a data set of occurrence and abundance of alien mammals in the Neotropics. Ecology. 2020 doi: 10.1002/ecy.3115. Accepted Author Manuscript. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daigle P. A summary of the environmental impacts of roads, management responses, and research gaps: a literature review. J. Ecosyst. Manag. 2010;10(3) [Google Scholar]

- Dean W. Univ of California Press; 1997. With Broadax and Firebrand: the Destruction of the Brazilian Atlantic Forest. [Google Scholar]

- DER . 2019. Departamento de Estrada e Rodagem do Estado de São Paulo.http://www.der.sp.gov.br/website/Home/ Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Desbiez A.L.J., Kluyber D. The role of giant armadillos (Priodontes maximus) as physical ecosystem engineers. Biotropica. 2013;45:537–540. [Google Scholar]

- DETRAN – Departamento Estadual de Trânsito de São Paulo. Available at: https://www.detran.sp.gov.br/. (Accessed 18 March 2019).

- Dodd C.K., Jr., Dorazio R.M. Using counts to simultaneously estimate abundance and detection probabilities in a salamander community. Herpetologica. 2004;60(4):468–478. [Google Scholar]

- Dornas R.A.P., Kindel A., Bager A., Freitas S.R. Avaliação da mortalidade de vertebrados em rodovias no Brasil. Ecologia de Estradas: Tendências e Pesquisas. In: Bager A., editor. 2012. pp. 139–152. [Google Scholar]

- Downes S.J., Handasyde K.A., Elgar M.A. The Use of Corridors by Mammals in Fragmented Australian Eucalypt Forests: uso de Corredores por Mamíferos en Bosques de Eucalipto en Australia. Conserv. Biol. 1997;11(3):718–726. [Google Scholar]

- Erickson W.P., Johnson G.D., David P., Jr. A summary and comparison of bird mortality from anthropogenic causes with an emphasis on collisions. In: Ralph C. John, Rich Terrell D., editors. 2005. Bird Conservation Implementation and Integration in the Americas: Proceedings of the Third International Partners in Flight Conference. 2002 March 20-24; Asilomar, California, Volume 2 Gen. Tech. Rep. PSW-GTR-191. Vol. 191. US Dept. of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Research Station; Albany, CA: 2005. pp. 1029–1042. [Google Scholar]

- Fahrig L. Effects of habitat fragmentation on biodiversity. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2003;34(1):487–515. [Google Scholar]

- Fahrig L., Pedlar J.H., Pope S.E., Taylor P.D., Wegner J.F. Effect of road traffic on amphibian density. Biol. Conserv. 1995;73(3):177–182. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes-Ferreira H., Alves R.R.N. The researches on the hunting in Brazil: a brief overview. Ethnobio. Cons. 2017;6 [Google Scholar]

- Ferraz K.M.P.M.D., Bonach K., Verdade L.M. Relationship between body mass and body length in capybaras (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris) Biota Neotropica. 2005;5(1):197–200. [Google Scholar]

- Ferraz K.M.P., de Barros Ferraz S.F., Moreira J.R., Couto H.T.Z., Verdade L.M. Capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris) distribution in agroecosystems: a cross-scale habitat analysis. J. Biogeogr. 2007;34(2):223–230. [Google Scholar]

- Florestal Instituto. Secretaria do Meio Ambiente; 2010. Inventário florestal da vegetação natural do estado de São Paulo.http://www.ambiente.sp.gov.br/sifesp/inventario-florestal/ Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Forman R.T., Alexander L.E. Roads and their major ecological effects. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Systemat. 1998;29(1):207–231. [Google Scholar]

- Forman R.T., Sperling D., Bissonette J.A., Clevenger A.P., Cutshall C.D., Dale V.H.…Jones J. Island press; 2003. Road Ecology: Science and Solutions. [Google Scholar]

- Frair J.L., Merrill E.H., Beyer H.L., Morales J.M. Thresholds in landscape connectivity and mortality risks in response to growing road networks. J. Appl. Ecol. 2008;45(5):1504–1513. [Google Scholar]

- Freitas S.R., de Oliveira A.N., Ciocheti G., Vieira M.V., da Silva Matos D.M. How landscape patterns influence road-kill of three species of mammals in the Brazilian Savanna. Oecol. Aust. 2015;18(1) [Google Scholar]

- G1 . 2011. Onça é encontrada morta e com patas cortadas em MS.http://g1.globo.com/brasil/noticia/2011/02/onca-e-encontrada-morta-e-com-patas-cortadas-em-ms.html Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Gascon C., Lovejoy T.E., Bierregaard R.O., Jr., Malcolm J.R., Stouffer P.C., Vasconcelos H.L.…Borges S. Matrix habitat and species richness in tropical forest remnants. Biol. Conserv. 1999;91(2-3):223–229. [Google Scholar]

- González-Suárez M., Zanchetta Ferreira F., Grilo C. Spatial and species-level predictions of road mortality risk using trait data. Global Ecol. Biogeogr. 2018 [Google Scholar]

- Groot Bruinderink G.W.T.A., Hazebroek E. Ungulate traffic collisions in Europe. Conserv. Biol. 1996;10(4):1059–1067. [Google Scholar]

- Huijser M.P., Gunson K.E., Abrams C. Report No. FHWA/MT-06-002/8177. Western Transportation Institute – Montana State University; Bozeman, MT, USA: 2006. Animal-vehicle collisions and habitat connectivity along Montana Highway 83 in the Seeley-Swan Valley, Montana: a reconnaissance. [Google Scholar]

- Huijser M.P., McGowen P.T., Fuller J., Hardy A., Kociolek A., Clevenger A.P., Smith D., Ament R. U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration; Washington D.C., USA: 2008. (Wildlife-vehicle Collision Reduction Study. Report to Congress). [Google Scholar]

- Huijser M.P., Abra F.D., Duffield J.W. Mammal road mortality and cost-benefit analyses of mitigation measures aimed at reducing collisions with capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris) in São Paulo State, Brazil. Oecol. Aust. 2013;17(1):129–146. [Google Scholar]

- IBGE . 2017. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística.https://cidades.ibge.gov.br/brasil/sp/sao-paulo/panorama Available at: [Google Scholar]

- ICMBio – Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade . 2011. Plano de Ação Nacional do Lobo-guará (Chrysocyon brachyurus)http://www.icmbio.gov.br/portal/faunabrasileira/plano-de-acao-nacional-lista/2120-plano-de-acao-para-conservacao-do-lobo-guara Available at: [Google Scholar]

- ICMBio – Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade . 2011. Plano de Ação Nacional da Onça parda (Puma concolor) Available at: [Google Scholar]

- ICMBio - Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade . 2018. Livro Vermelho da Fauna Brasileira Ameaçada de Extinção: Volume II - Mamíferos. [Google Scholar]

- http://www.icmbio.gov.br/portal/images/stories/docs-plano-de-acao/pan-onca-parda/sumario-on%C3%A7aparda-icmbio-web.pdf

- INMET . 2019. Instituto Nacional de Meteorologia. Normais climatológicas do Brasil, período 1981-2010.http://www.inmet.gov.br/http://www.inmet.gov.br/portal/index.php?r=clima/normaisclimatologicas [Google Scholar]

- IUCN Red List International union for conservation of nature. 2019. https://www.iucnredlist.org/ Available at:

- Jácomo A.T., Silveira L., Diniz-Filho J.A.F. Niche separation between the maned wolf (Chrysocyon brachyurus), the crab-eating fox (Dusicyon thous) and the hoary fox (Dusicyon vetulus) in central Brazil. J. Zool. 2004;262(1):99–106. [Google Scholar]

- Laurance W.F., Clements G.R., Sloan S., O’connell C.S., Mueller N.D., Goosem M., Van Der Ree R. A global strategy for road building. Nature. 2014;513(7517):229. doi: 10.1038/nature13717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemos F.G., Azevedo F.C., Costa H.C., May J.R., J A. Human threats to hoary and crab-eating foxes in central Brazil. Canid News. 2011;14(2):1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Lemos F.G., de Azevedo F.C., de Mello Beisiegel B., Jorge R.P.S., de Paula R.C., Rodrigues F.H.G., de Almeida Rodrigues L. Avaliação do risco de extinção da Raposa-do-campo Lycalopex vetulus (Lund, 1842) no Brasil. Biodiv. Brasil. 2013;(1):160–171. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, B., McEvoy J., Morato, R.G., Luz, H.R., Costa F.B., Benatti, H.R., Rocha, V.J., Piovezan, U., Monticelli, P.F., Nievas, A.M., Pacheco, R.C., Leimgruber, P., Labruna, M.B., Ferraz, K.M.P.M.B (Accepted). Human Modified Landscapes Alter Ecological Spatial Patterns of Capybaras.

- Lyra-Jorge M.C., Ciocheti G., Pivello V.R. Carnivore mammals in a fragmented landscape in northeast of São Paulo State, Brazil. Biodivers. Conserv. 2008;17(7):1573. [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald D.W., Loveridge A.J., Nowell K. Dramatis personae: an introduction to the wild felids. Biol. Cons. Wild Feild. 2010;1:3–58. [Google Scholar]

- Magioli M., Ferraz K.M.P.M.B., Setz E.Z.F., Percequillo A.R., Rondon M.V.D.S.S., Kuhnen V.V.…Rodrigues M.G. Connectivity maintain mammal assemblages functional diversity within agricultural and fragmented landscapes. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2016;62(4):431–446. [Google Scholar]

- Magioli M., Bovo A.A.A., Huijser M.P., Abra F.D., Miotto R.A., Andrade V.H.V.P.…Ferraz K.M.P.M.B. Short and narrow roads cause substantial impacts on wildlife. Oecol. Aust. 2019;23(1) [Google Scholar]

- Magioli M., Moreira M.Z., Fonseca R.C.B., Ribeiro M.C., Rodrigues M.G., Ferraz K.M.P.M.B. Human-modified landscapes alter mammal resource and habitat use and trophic structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Unit. States Am. 2019;116(37):18466–18472. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1904384116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medici E.P., Abra F.D. Lições aprendidas na conservação da anta brasileira e os desafios para mitigar uma de suas ameaças mais graves: O atropelamento em rodovias. Bol. Soc. Brasil. Mastozoo. 2019;85:152–160. [Google Scholar]

- Medici E.P., Flesher K., de Mello Beisiegel B., Keuroghlian A., Desbiez A.L.J., Gatti A.…de Azevedo F.C. Avaliação do risco de extinção da anta brasileira Tapirus terrestris Linnaeus, 1758, no Brasil. Biodiv. Brasil. 2012;(1):103–116. [Google Scholar]

- Mittermeier R.A., Turner W.R., Larsen F.W., Brooks T.M., Gascon C. Global biodiversity conservation: the critical role of hotspots. In: Zachos F.E., Habel J.C., editors. Biodiversity Hotspots. Springer; Berlin: 2011. pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen S.E., Stenhouse G.B., Boyce M.S. A habitat-based framework for grizzly bear conservation in Alberta. Biol. Conserv. 2006;130(2):217–229. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen C., Thompson D., Kelly M., Lopez-Gonzalez C.A. 2015. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015: e.T18868A97216466. Puma concolor (errata version published in 2016) [Google Scholar]

- Projeto MapBiomas Coleção 5 da Série Anual de Mapas de Cobertura e Uso de Solo do Brasil. 2020. http://mapbiomas.org/ Available at:

- Puig S., Videla F., Cona M.I., Monge S.A. Diet of the brown hare (Lepus europaeus) and food availability in northern Patagonia (Mendoza, Argentina) Mamm. Biol. 2007;72(4):240–250. [Google Scholar]

- Ratton P., Secco H., Da Rosa C.A. Carcass permanency time and its implications to the roadkill data. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2014;60(3):543–546. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro M.C., Metzger J.P., Martensen A.C., Ponzoni F.J., Hirota M.M. The Brazilian Atlantic Forest: how much is left, and how is the remaining forest distributed? Implications for conservation. Biol. Conserv. 2009;142(6):1141–1153. [Google Scholar]

- Richard E., Juliá J.P. Diet of Mazama gouazoubira (Mammalia, cervidae) in a secondary environment of yungas, Argentina. Iheringia. Série Zool. 2001;(90):147–156. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues T.F., Mantellatto A.M.B., Superina M., Chiarello A.G. Ecosystem services provided by armadillos. Biol. Rev. 2020;95:1–21. doi: 10.1111/brv.12551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rytwinski T., Fahrig L. Why are some animal populations unaffected or positively affected by roads? Oecologia. 2013;173(3):1143–1156. doi: 10.1007/s00442-013-2684-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rytwinski T., Soanes K., Jaeger J.A., Fahrig L., Findlay C.S., Houlahan J., van der Ree R., van der Grift E.A. How effective is road mitigation at reducing road-kill? A meta-analysis. PloS One. 2016;11(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0166941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos R.A.L., Santos S.M., Santos-Reis M., de Figueiredo A.P., Bager A., Aguiar L.M., Ascensao F. Carcass persistence and detectability: reducing the uncertainty surrounding wildlife-vehicle collision surveys. PloS One. 2016;11(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silveira L.F., Beisiegel B.D.M., Curcio F.F., Valdujo P.H., Dixo M., Verdade V.K., Mattox G.M.T., Cunningham P.T.M. Para que servem os inventários de fauna? Estud. Avançados. 2010;24(68):173–207. [Google Scholar]

- Smith L.L., Dodd C.K., Jr. Florida scientist; Alachua County, Florida: 2003. Wildlife Mortality on US Highway 441 across Paynes Prairie; pp. 128–140. [Google Scholar]

- Son S.W., Kil S.H., Yun Y.J., Yoon J.H., Jeon H.J., Son Y.H. Analysis of influential factors of roadkill occurrence-A case study of Seorak National Park. J. Korean Inst. Landsc. Archit. 2016;44:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira F.Z., Coelho A.V.P., Esperandio I.B., Kindel A. Vertebrate road mortality estimates: effects of sampling methods and carcass removal. Biol. Conserv. 2013;157:317–323. [Google Scholar]

- Trombulak S.C., Frissell C.A. Review of ecological effects of roads on terrestrial and aquatic communities. Conserv. Biol. 2000;14(1):18–30. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Zande A.N., Ter Keurs W.J., Van der Weijden W.J. The impact of roads on the densities of four bird species in an open field habitat—evidence of a long-distance effect. Biol. Conserv. 1980;18(4):299–321. [Google Scholar]

- Verdade L.M., Ferraz K.M.P.M.B. Capybaras in an anthropogenic habitat in southeastern Brazil. Braz. J. Biol. 2006;66(1B):371–378. doi: 10.1590/s1519-69842006000200019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdade L.M., Gheler-Costa C., Penteado M., Dotta G. The impacts of sugarcane expansion on wildlife in the state of São Paulo, Brazil. J. Sustain. Bioenergy Syst. 2012;2(4):138. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.