Abstract

Extracellular diphosphate and triphosphate nucleotides are released from activated or injured cells to trigger vascular and immune P2 purinergic receptors, provoking inflammation and vascular thrombosis. These metabokines are scavenged by ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase-1 (E-NTPDase1 or CD39). Further degradation of the monophosphate nucleoside end products occurs by surface ecto-5′-nucleotidase (NMPase) or CD73. These ectoenzymatic processes work in tandem to promote adenosinergic responses, which are immunosuppressive and antithrombotic. These homeostatic ectoenzymatic mechanisms are lost in the setting of oxidative stress, which exacerbates inflammatory processes. We have engineered bifunctional enzymes made up from ectodomains (ECDs) of CD39 and CD73 within a single polypeptide. Human alkaline phosphatase-ectodomain (ALP-ECD) and human acid phosphatase-ectodomain (HAP-ECD) fusion proteins were also generated, characterized, and compared with these CD39-ECD, CD73-ECD, and bifunctional fusion proteins. Through the application of colorimetrical functional assays and high-performance liquid chromatography kinetic assays, we demonstrate that the bifunctional ectoenzymes express high levels of CD39-like NTPDase activity and CD73-like NMPase activity. Chimeric CD39-CD73-ECD proteins were superior in converting triphosphate and diphosphate nucleotides into nucleosides when compared with ALP-ECD and HAP-ECD. We also note a pH sensitivity difference between the bifunctional fusion proteins and parental fusions, as well as ectoenzymatic property distinctions. Intriguingly, these innovative reagents decreased platelet activation to exogenous agonists in vitro. We propose that these chimeric fusion proteins could serve as therapeutic agents in inflammatory diseases, acting to scavenge proinflammatory ATP and also generate anti-inflammatory adenosine.

Keywords: bifunctional fusion, ectonucleotidase, inflammation, platelet aggregation, purinergic signaling

INTRODUCTION

Damaged cells, activated immune cells, platelets, and stressed cells release large amounts of adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP) and adenosine 5′-diphosphate (ADP) during tissue injury, inflammation, hypoxia, apoptosis, vascular thrombosis, and mechanical perturbation (4, 9, 10, 12, 13, 19, 42). In addition to passive release via ruptured cell membranes, active mechanisms of nucleoside movement to the extracellular space include exocytosis of intracellular vesicles and transport by membrane-bound channels or transporters (7, 13, 19, 26, 42). Extracellular nucleotides serve as potent signaling molecules and stimulate ligand-gated ion channel P2X receptors (P2XR) and G-protein-coupled P2Y receptors (P2YR) to drive inflammation, platelet activation, clotting, immune response regulation, tissue blood flow control, and neuronal signaling (7, 12, 13, 19, 30). This purinergic signaling pathway is also crucial to the activation of inflammasomes, via P2X7R, with subsequent proinflammatory cytokine release in response to damage-associated molecular patterns and pathogen-associated molecular patterns (39). To prevent overstimulation and desensitization of P2XRs and P2YRs, ATP and ADP are quickly hydrolyzed to produce adenosine 5′-monophosphate (AMP), and eventually the nucleoside adenosine. Elegantly, adenosine is an anti-inflammatory signal that binds to P1 purinergic receptors (14, 24), which consist of four G-protein-coupled receptors (A1, A2A, A2B, and A3). Activation of A2A and A2B receptors by adenosine deactivates inflammatory responses and mediates immunosuppressive effects on immune cells and antithrombotic effects on platelets within the vasculature (1, 16, 37).

To modulate purinergic signaling circuits and their consequential biological events, the hydrolysis of extracellular nucleotides is regulated by several groups of ectonucleotidases (31, 42, 47). They include ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolases (E-NTPDase), ecto-5′-nucleotidase (eN), ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterases (E-NPPs), alkaline phosphatases (ALP), and acid phosphatases (HAPs). E-NTPDases hydrolyze extracellular diphosphate and triphosphate nucleotides in the presence of divalent cations (31). Eight members of this family have been cloned and functionally characterized, including plasma membrane-bounded CD39 protein/NTPDase1, CD39L1/NTPDase2, CD39L3/NTPDase3, NTPDase8, and four intracellular organelle-localized NTPDase 4, 5, 6, and 7. This family represents the major nucleotide-hydrolyzing enzymes that modulate purinergic signaling but do not hydrolyze dinucleoside polyphosphates, ADP ribose, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, or AMP. eN CD73 is a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored homodimeric enzyme that converts AMP into adenosine and inorganic phosphate (46). There are seven vertebrate members of the E-NPP family (38). Hydrolysis of nucleotides by E-NPPs typically releases AMP and pyrophosphate. Human prostatic acid phosphatase (HAP) is expressed as either a membrane or a secreted protein (28). Previous work has shown the activity of a murine isoform to be pH dependent and able to dephosphorylate AMP and some ADP at neutral pH but with activity toward ATP, ADP, and AMP under acidic conditions (35). Alkaline phosphatases belong to one of the best-studied GPI-anchored plasma membrane enzymes (18, 25). The human genome encodes four ALP genes. ALPs are typically homodimeric proteins and can hydrolyze ATP via ADP and AMP intermediates to adenosine at alkaline and neutral pH (32).

The conversion from proinflammatory ATP or ADP to anti-inflammatory adenosine is further regulated by the spatial and temporal expression patterns, enzymatic activity variation, enzyme concentration, exposure duration, and localization of the ectonucleotidases. CD39 is the major vascular ectonucleotidase that hydrolyzes both ATP to ADP and ADP to AMP (8, 31). It terminates purinergic P2X signaling events under normal conditions; however, its biological activity is rapidly lost with vascular inflammatory events (12). CD73 converts AMP to adenosine that maintains vascular barrier function and elicits anti-inflammatory responses, even though CD73 importantly does not directly ameliorate ATP and ADP proinflammatory signaling (8, 11, 16). The expression and surface localization of CD73 are different from those of CD39 in a variety of tissues, including the heart, placenta, lung, liver, colon, brain, and kidney (6, 31). Even in human peripheral blood cells, conditions for the induction or repression of CD39 and CD73 are different. CD39 can be transcriptionally induced following exposure to proinflammatory conditions, and expression has been linked to both T-cell regulation and exhaustion; in contrast, CD73 expression may be selectively repressed in these settings or in lymphocyte subset development, suggesting partial discordance of ectoenzyme functions (1).

ALP seems to be the only ectonucleotidase with activity sufficient to sequentially hydrolyze nucleoside triphosphates to a nucleoside (31, 42, 47); however, the intrinsic ectonucleotidase activity appears to contribute only minor components toward overall ATP scavenging. No direct comparisons of the activity of ALP, HAP, CD39, and CD73 have yet been reported.

In this work, we produced novel bifunctional enzymes engineered to sequentially hydrolyze ATP to adenosine, through the genetic fusion of the ectodomains (ECD) of CD39 and CD73. We demonstrate that such enzymes possessed full activity of hydrolyzing ATP or ADP via AMP to adenosine. The enzymatic properties and hydrolysis kinetics of the bifunctional enzymes were compared with ALP-ECD, HAP-ECD, and CD39-ECD and CD73-ECD. The data indicate that the bifunctional enzyme is a superior enzyme in converting triphosphate and diphosphate nucleotides into nucleosides compared with ALP-ECD and HAP-ECD. The results also reveal a pH sensitivity and enzymatic property difference between the bifunctional fusions and the parental molecules. The investigation shows that the bifunctional enzymes decreased platelet activation and aggregation in vitro and have potential as a therapeutic pharmacological agent.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

Adenosine-5′-triphosphate disodium, adenosine-5′-diphosphate disodium, adenosine-5′-monophosphate disodium, uridine-5′-triphosphate trisodium, uridine-5′-diphosphate disodium, uridine-5′-monophosphate disodium, TRAP-6, Chrono-log, Collagen P/N 385, malachite green hydrochloride, ammonium molybdate, polyoxyethylene 10 lauryl ether, and sodium citrate dihydrate were purchased from Millipore Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

Expression constructs.

DNA fragments, encoding human CD39 (Thr45-Thr483; GenBank No. NP_001091645.1), human CD73 (Trp27-Ser549; GenBank No. NP_002517.1), human testicular and thymus alkaline phosphatase (ALP, Ile20-Thr502; GenBank No. NP_112603.2), human prostatic acid phosphatase (HAP, Lys33-Asp386; GenBank No. NM_001099.5), and human immunoglobulin γ1 Fc fragment (CH23, constant region starting with Gly236, the numbering of the European Union (EU) amino acid sequence), were gene-synthesized by Blue Heron Biotech (Bothell, WA) and GenScript Biotech (Piscataway, NJ). Corresponding full-length DNA fragments with an NH2-terminal signal sequence of glycoprotein 1b α chain (MPLLLLLLLLPSPLHG) and a Gly4 linker in between each protein domain were assembled by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and cloned into a human cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter mammalian expression vector at EcoRI and BamHI restriction sites (pEZ1002, HAPCH23; pEZ1006, ALPCH23; pEZ1007, CD73CH23CD39; pEZ1009, CD39CH23CD73; pEZ1010, CD39CD73CH23; pEZ1011, CD73CH23CD39; pWZ1013, CD73CH23; pWZ1014, CD39CH23). All constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Cell culture and transfection.

Human embryonic kidney 293 (Expi293F) cells were grown and maintained in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 at 37°C in Expi293 medium (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA). DNA transfection procedures in Expi293F cells were followed as described in Thermo Fisher manufacturer’s protocols. Briefly, DNA and lipofectamine complex were inoculated with 3.0 × 106/mL cells, and expression enhancers were added 24 h after transfection. Conditioned media were harvested at day 4 and filtered with 0.2-µm filters.

Protein purification.

In all, 5 mL of Protein A column (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) pre-equilibrated with 50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.5 (TBS), was loaded with conditioned medium and washed with 10 column volumes (CV) of TBS, before the protein was eluted using 100% step of 150 mM glycine, pH 3.5, in TBS. The protein was dialyzed overnight against 1,000-fold TBS buffer overnight. Protein samples were pooled and concentrated to 0.5–1.0 mg/mL using a 10-kDa MWCO centrifugal device.

Colorimetric NTPDase and NMPase assays.

The colorimetric assay was performed as previously described (22, 44). Aqueous solutions of 0.045% malachite green hydrochloride (MG), 4.2% ammonium molybdate in 4 N HCl (AM), 4% C12E10 (polyoxyethylene 10 lauryl ether, MilliporeSigma) (CE), and 34% sodium citrate dihydrate (w/v) were prepared. Prior to the assay, MG and AM were mixed in a 3:1 ratio, incubated for at least 20 min, and filtered through 0.2-µm membrane. Then, 0.1 mL of CE solution was added to every 5 mL of MG/AG solution. The NTPDase buffer contained 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 120 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, and 0.5 mM EDTA. Also, 5mM CaCl2 was added to the calcium-plus reaction buffer. During the NTPDase assay, CD39 fusions or bifunctional samples (100 ng) were added to initiate the reaction at 37°C for 10 min. Then, 0.8 mL of MG/AG/CE solution and 100 µL of citrate were added sequentially to terminate the reactions. A660 baseline absorbance was measured using 1 mL of MG/AG/CE buffer, and phosphate concentrations were calculated with a standard curve and subtraction of enzyme absorbance. Similarly, 200 ng of ALP-ECD or HAP-ECD was used. For the reaction buffer of pH 5.8, 200 mM histidine, pH 5.8, 120 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, and 0.5 mM EDTA were used. For the reaction buffer of pH 9.0, 200 mM N-cyclohexyl-2-aminoethanesulfonic acid, 120 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, and 0.5 mM EDTA were used.

High-performance liquid chromatography.

Perchloride acid (PCA)-treated samples were neutralized with 0.4 M K2HPO4 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and ATP, ADP, AMP, and adenosine concentrations were analyzed with an Agilent 1260 Infinity HPLC system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) equipped with a G1312B binary pump, a G1367C high-performance autosampler, and a G1314C Variable Wavelength Detector VL+ set at 254 nm. Nucleotides were separated by ion-pair reversed-phase chromatography using an Atlantis dC18 column (3 mm × 150 mm, particle size 3 µm; Waters Corporation, Milford, MA). The samples were loaded on the column equilibrated with buffer A (0.1 M KH2PO4, 4 mM tetrabutylammonium hydrogen sulfate, pH 6). The mobile phase was developed linearly from 0% to 100% buffer B (70% buffer A/30% methanol) during the first 13 min and remained isocratic at 100% buffer B for 15 min. Subsequently, the column was re-equilibrated with buffer A for 7 min. The flow rate was 0.5 mL/min. Adenosine, AMP, ADP, and ATP were identified by their retention times, and concentrations were calculated using known standards run in parallel.

Analysis of platelet activation in vitro.

Platelet aggregation was measured by a Lumi-aggregometer (Chrono-Log, Havertown, PA) as described previously (34). Platelet-rich plasma was generated, as based on prior studies (20). In short, whole venous blood was drawn into 0.4% sodium citrate (final concentration w/v) from healthy donor volunteers, who provided written informed consent, in accordance with institutional review board (IRB)-approved protocols. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) was obtained by centrifugation at 200 relative centrifugal force (RCF) for 16 min, and the platelet concentration was adjusted at 3 × 105 per μL with platelet-poor plasma. PRP was kept at 37°C for 30 min before platelet aggregation assay. Platelet aggregation assays were carried out using Chrono-log model 600 with indicated agonists, according to the instruction manuals provided by Chrono-log Co. (Havertown, PA); here, ∼0.3 mL of the solution was incubated at 37°C with platelet agonists at final concentrations of 2 µg/mL collagen or 12.5 nM TRAP-6, and the fraction of light transmission over time was measured. For bifunctional ectoenzyme treatment of platelets, various amounts of the recombinant proteins were added to the PRP, as indicated.

RESULTS

Production of novel CD39 and CD73 bifunctional fusions as well as other control fusion proteins.

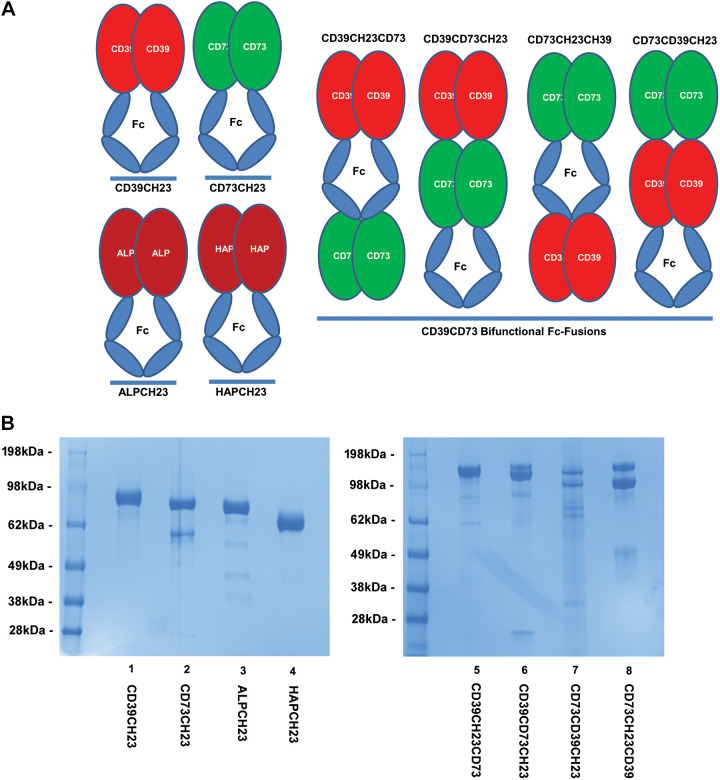

To design a novel bifunctional enzyme able to hydrolyze triphosphate and diphosphate nucleotides completely to nucleoside products (Fig. 1A), the ectodomain of human CD39 (Thr45-Thr483), with the amino acid boundaries defined by structural modeling on rat CD39 structures (43), was fused to either the NH2- or COOH-termini of the ectodomain of human CD73 (Trp27-Ser549), with amino acid boundaries defined by structural modeling on human CD73 structure (21). The ECD of CD39 or CD73 was then fused to either the NH2- or COOH-termini of the IgG1 Fc. These protein domains were connected with Gly4 linkers. The Fc domain fusion permitted a protein-A resin purification strategy and also enabled in vivo FcRn binding (29), extending circulating protein half-life.

Figure 1.

Engineering novel bifunctional fusions of CD39-CD73 and control fusion proteins. A: novel CD39-CD73 bifunctional chimeric proteins were bioengineered by fusing the ectodomain (ECD) of human CD39 and CD73 to either the NH2- or COOH-terminus of the Fc region of human IgG1 and to the other domain through gene synthesis and PCR cloning, as described in materials and methods. To generate activity comparison controls, human CD39-ECD-Fc fusion (CD39CH23), human CD73-ECD-Fc fusion (CD73CH23), human alkaline phosphatase ECD-Fc fusion (ALPCH23), and human acid phosphatase ECD-Fc fusion (HAPCH23) were also generated through gene synthesis and PCR cloning, as described in materials and methods. B: production of CD39-CD73 bifunctional fusions and the control fusion proteins. The resulting constructs shown in A were then transfected into Expi293F cells as described in materials and methods. Chimeric recombinant proteins, secreted into conditioned media, were affinity-purified through protein A resin and buffer-exchanged, as described in materials and methods. As described, 4 µg of protein samples was run, under reduced conditions, on 4%–12% SDS-PAGE and then stained with Coomassie blue. SDS-PAGE, sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

To generate the control fusion proteins (Fig. 1A), CD39-ECD-Fc fusion (Thr45-Thr483, CD39CH23), CD73-ECD-Fc fusion (Trp27-Ser549, CD73CH23), human alkaline phosphatase ECD-Fc fusion (17, 23) (Ile20-Thr502, ALPCH23), and human acid phosphatase ECD-Fc (48) (Lys33-Asp386, HAPCH23) were also generated by fusing domains to the NH2-terminus of IgG1 Fc with a Gly4 linker. It has been reported that both alkaline phosphatase (32) and acid phosphatase (35) have activity toward triphosphate, diphosphate, and monophosphate nucleotides, but their enzymatic activities have not yet been compared with each other or with other ectonucleotidases.

The resulting constructs were transfected into Expi293F cells for protein expression. The chimeric recombinant proteins were purified and as shown in SDS-PAGE of Fig. 1B, control fusion proteins migrated as expected. CD39CH23 (lane 1) migrated around 95 kDa (expected aglycosylated MW: 74 kDa; glycosylated MW: ∼95.2 kDa). CD73CH23 (lane 2) migrated around 90 kDa (expected aglycosylated MW: 81.9 kDa; glycosylated MW: ∼98 kDa). ALPCH23 (lane 3) migrated around 85 kDa (expected aglycosylated MW: 76.5 kDa; glycosylated MW: ∼88 kDa). HAPCH23 (lane 4) migrates around 70kDa (expected aglycosylated MW: 65 kDa; glycosylated MW: ∼79 kDa). CD39CH23 and HAPCH23 migrated as a homogeneous single band in SDS-PAGE, whereas minor low-molecular-weight species were detected for CD73CH23 and ALPCH23. For bifunctional fusions, CD39CH23CD73 (lane 5) migrated as a homogeneous 160-kDa protein band (expected aglycosylated MW: 132.2 kDa; glycosylated MW: ∼162 kDa). CD39CD73CH23 and CD73CH23CD39 contained the expected 160-kDa band and one slightly smaller protein species (lanes 6 and 8). Significant degradation products were detected for CD73CD39CH23 (lane 7).

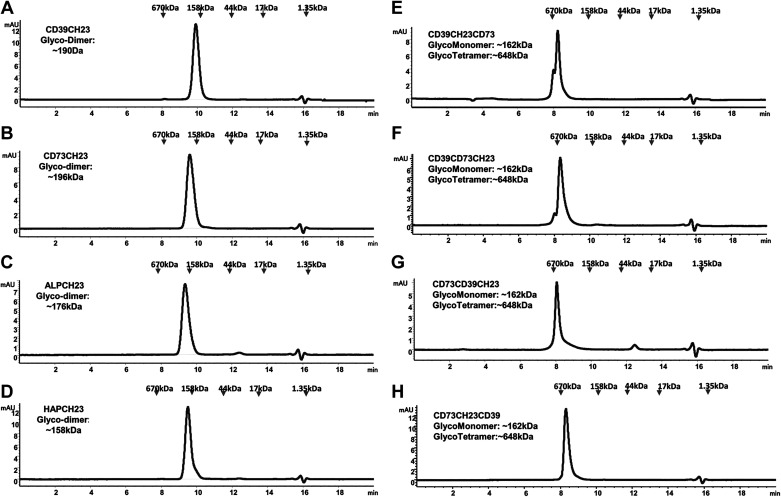

When the fusion proteins were analyzed in size-exclusion chromatography (Fig. 2), CD39CH23, CD73CH23, ALPCH23, and HAPCH23 were eluted slightly earlier (larger) than bovine γ-globulin marker (158 kDa), consistent with dimer species (Fig. 2, A–D). All four bifunctional fusions eluted slightly later (smaller) than thyroglobulin (670 kDa), consistent with tetramer species (Fig. 2, E–H). They could be a dimer of Fc dimer, as CD73 is a homodimer (21).

Figure 2.

Size-exclusion chromatography analysis on CD39-CD73 bifunctional fusions and the control fusion proteins. Purified proteins (∼10 µg) described in Fig. 1 were analyzed by size-exclusion chromatography by use of Superdex 200 columns, equilibrated with PBS (137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 8.1 mM Na2HPO4, 2.7 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.2). Gel filtration standard components (Bio-Rad) were vitamin B12 (1.36 kDa), myoglobin (17 kDa), ovalbumin (44 kDa), γ-globulin (158 kDa), and thyroglobulin (670 kDa). PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

Enzymatic characterization of bifunctional fusions and control proteins.

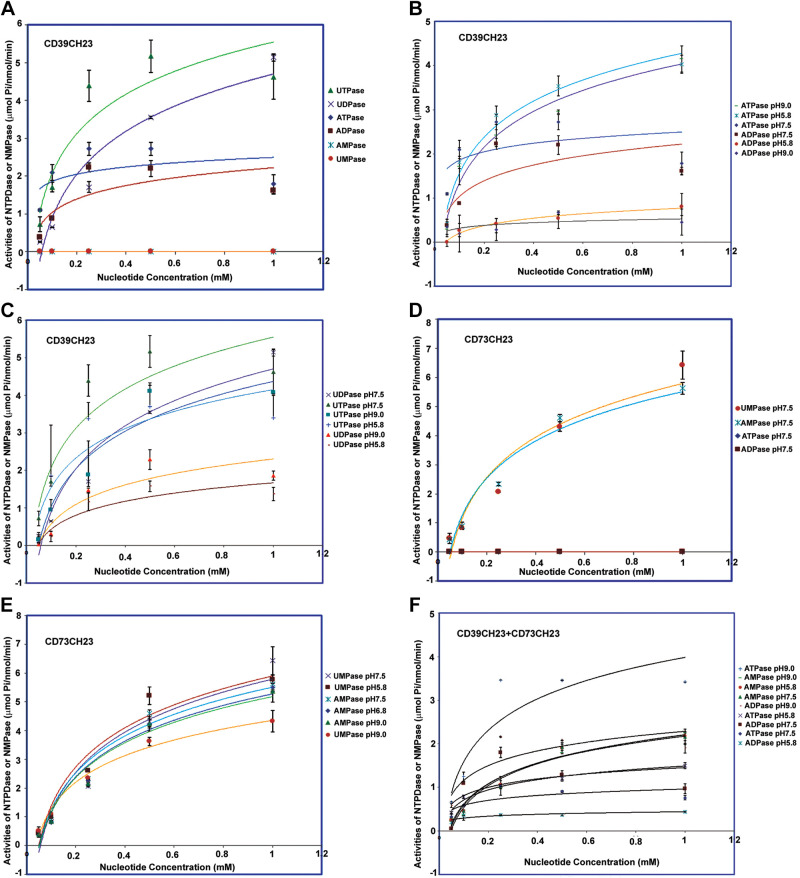

Next, we set out to determine the enzymatic activities of the purified fusion proteins with a colorimetric functional assay commonly used for NTPDase enzymes. As shown in Fig. 3A and Table 1, the CD39CH23 fusion exhibited the activities of ATPase (Km, 0.037 mM; Vmax, 2.57 µmol/nmol/min), ADPase (Km, 0.11 mM; Vmax, 2.34 µmol/nmol/min), UTPase (Km, 0.18 mM, Vmax 6.26 µmol/nmol/min), and UDPase (Km 1.51 mM; Vmax, 13.13 µmol/nmol/min), but did not exhibit NMPase activity. These enzymatic parameters were similar to those reported (15, 41). As shown in Fig. 3B and Table 1, CD39CH23’s ATPase activity was elevated in both acidic, pH 5.8 (Km, 0.21 mM; Vmax, 5.02 µmol/nmol/min), and alkaline, pH 9.0 (Km, 0.31 mM; Vmax, 5.24 µmol/nmol/min), conditions. Its ADPase activity was lower under acidic and alkaline conditions relative to a physiological pH. In contrast, as shown in Fig. 3C and Table 1, CD39CH23’s UDPase activity was lower at acidic pH (Km, 0.31 mM; Vmax, 2.09 µmol/nmol/min) and alkaline pH (Km, 0.33 mM; Vmax, 2.93 µmol/nmol/min) than at neutral pH; its UTPase activity was not affected significantly by pH changes (pH 5.8: Km, 0.16 mM; Vmax, 4.53 µmol/nmol/min; pH 9.0: Km, 0.52 mM; Vmax, 6.75 µmol/nmol/min).

Figure 3.

Enzymatic characterization of CD39CH23 and CD73CH23. CD39CH23 (A–C), CD73CH23 (D and E), or their mixture (F). Colorimetric NTPDase and NMPase activity assays are described in materials and methods. For NTPDase assays, 100 ng of CD39 fusion was added to initiate the reaction at 37°C for 10 min. In all, 0.8 mL of MG/AG/CE solution and 100 µL of citrate were added sequentially to terminate the reactions. A660 baseline absorbance was measured using 1 mL of MG/AG/CE buffer, and phosphate concentrations were calculated with a standard curve and subtraction of enzyme absorbance. For NMPase assay, 100 ng of CD73 fusion protein was used for the reaction at 37°C for 10 min. The error bars at each data point (n = 3) are standard deviations, as calculated from experiments run in triplicate. NMPase, ecto-5′-nucleotidase.

Table 1.

Vmax and Km of CD39CH23 at various pH levels for NTPDase and NMPase activities

| CD39CH23 | Km, mM | Vmax, µmol Pi/nmol/min |

|---|---|---|

| ATPase (pH 7.5) | 0.037 | 2.57 |

| UTPase (pH 7.5) | 0.18 | 6.26 |

| ADPase (pH 7.5) | 0.11 | 2.34 |

| UDPase (pH 7.5) | 1.51 | 13.13 |

| AMPase (pH 7.5) | 0 | 0 |

| UMPase (pH 7.5) | 0 | 0 |

| ATPase (pH 5.8) | 0.21 | 5.02 |

| ATPase (pH 9.0) | 0.31 | 5.24 |

| ADPase (pH 5.8) | 0.52 | 1.20 |

| ADPase (pH 9.0) | 0.084 | 0.56 |

| UTPase (pH 5.8) | 0.16 | 4.53 |

| UTPase (pH 9.0) | 0.52 | 6.75 |

| UDPase (pH 5.8) | 0.31 | 2.09 |

| UDPase (pH 9.0) | 0.33 | 2.93 |

As shown in Fig. 3D and Table 2, the CD73CH23 fusion at neutral pH possesses robust AMPase (Km, 0.77 mM; Vmax, 10.32 µmol/nmol/min) and UMPase activities (Km, 1.57 mM; Vmax, 16.73 µmol/nmol/min) but lacks ATPDase activity. As shown in Fig. 3E and Table 2, CD73CH23’s NMPase activity is less affected by acidic or alkaline conditions. When CD39CH23 and CD73CH23 were added to a solution in an equimolar ratio, the mixture had both NTPDase activity and NMPase activity (Fig. 3F, Table 3) reflecting active contributions of two ectonucleotidases.

Table 2.

Vmax and Km of CD73CH23 at various pH levels for NTPDase and NMPase activities

| CD73CH23 | Km, mM | Vmax, µmol Pi/nmol/min |

|---|---|---|

| AMPase (pH 7.5) | 0.77 | 10.32 |

| UMPase (pH 7.5) | 1.57 | 16.73 |

| ATPase (pH 7.5) | 0 | 0 |

| ADPase (pH 7.5) | 0 | 0 |

| AMPase (pH 5.8) | 0.89 | 10.69 |

| AMPase (pH 9.0) | 0.85 | 10.24 |

| UMPase (pH 5.8) | 0.63 | 9.94 |

| UMPase (pH 9.0) | 0.41 | 6.25 |

Table 3.

Vmax and Km of the mixture of CD39CH23 and CD73CH23 at various pH levels for NTPDase and NMPase activities

| CD39CH23 + CD73CH23 | Km, mM | Vmax, µmol Pi/nmol/min |

|---|---|---|

| ATPase (pH 7.5) | 0.062 | 1.97 |

| ADPase (pH 7.5) | 0.074 | 1.82 |

| AMPase (pH 7.5) | 0.51 | 3.40 |

| ATPase (pH 5.8) | 0.13 | 1.62 |

| ADPase (pH 5.8) | 0.04 | 0.44 |

| AMPase (pH 5.8) | 0.52 | 3.46 |

| ATPase (pH 9.0) | 0.164 | 4.42 |

| ADPase (pH 9.0) | 0.098 | 2.40 |

| AMPase (pH 9.0) | 0.69 | 3.92 |

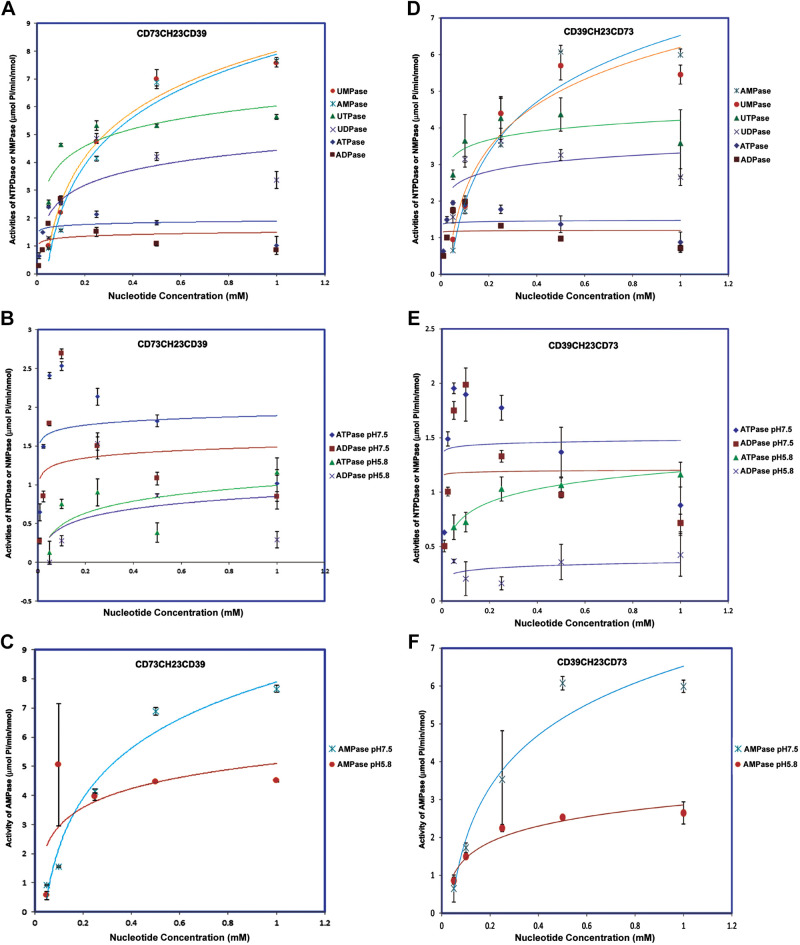

The bifunctional fusion CD73CH23CH39 possessed both NTPDase activity and NMPase activity at physiological pH (Fig. 4A and Table 4). The Km for NTPDase activity was significantly lower in the bifunctional fusion than in the CD39CH23 fusion (ATPase: Km 0.008 mM vs. 0.037 mM; ADPase: Km 0.011 mM vs. 0.11 mM), whereas Vmax was similar (ATPase: 2 µmol/nmol/min; ADPase: 1.57 µmol/nmol/min). The Km and Vmax for the NMPase function were similar between the bifunctional fusion (AMPase: Km, 0.46 mM; Vmax, 11.73 µmol/nmol/min; UMPase: Km, 0.32 mM; Vmax, 10.50 µmol/nmol/min) and CD73CH23. With regard to the pH sensitivity, CD73CH23CD39 bifunctional fusion’s ATPDase and AMPase activities decreased at acidic pH (Fig. 4, B and C, and Table 4). CD39CH23CH73, a fusion protein linked in the reverse orientation, displayed similar NTPDase and NMPase activities to that of CD73CH23CD39 (Fig. 4D and Table 5). Its ATPDase and AMPase activities were also sensitive to acidic pH (Fig. 4, E and F, and Table 5).

Figure 4.

Enzymatic characterization of bifunctional fusions of CD73CH23CD39 and CD39CH23CD73. Fusion protein CD73CH23CD39 (A–C) and CD39CH23CD73 (D–F) were measured for colorimetric NTPDase and NMPase activity assays as described in materials and methods. In total, 100 ng of the fusion proteins was used for the reaction at 37°C for 10 min. The error bars at each data point (n = 3) are standard deviations, as calculated from experiments run in triplicate. NMPase, ecto-5′-nucleotidase; NTPDase, nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase.

Table 4.

Vmax and Km of CD73CH23CD39 at various pH levels for NTPDase and NMPase activities

| CD73CH23CD39 | Km, mM | Vmax, µmol Pi/nmol/min |

|---|---|---|

| ATPase (pH 7.5) | 0.008 | 2.00 |

| UTPase (pH 7.5) | 0.048 | 6.05 |

| ADPase (pH 7.5) | 0.011 | 1.57 |

| UDPase (pH 7.5) | 0.066 | 4.55 |

| AMPase (pH 7.5) | 0.46 | 11.73 |

| UMPase (pH 7.5) | 0.32 | 10.50 |

| ATPase (pH 5.8) | 0.023 | 1.04 |

| ADPase (pH 5.8) | 0.003 | 0.79 |

| AMPase (pH 5.8) | 0.063 | 5.1 |

Table 5.

Vmax and Km of CD39CH23CD73 at various pH levels for NTPDase and NMPase activities

| CD39CH23CD73 | Km, mM | Vmax, µmol Pi/nmol/min |

|---|---|---|

| ATPase (pH 7.5) | 0.023 | 2.57 |

| UTPase (pH 7.5) | 0.022 | 4.26 |

| ADPase (pH 7.5) | 0.019 | 1.93 |

| UDPase (pH 7.5) | 0.059 | 4.27 |

| AMPase (pH 7.5) | 0.34 | 8.73 |

| UMPase (pH 7.5) | 0.21 | 7.29 |

| ATPase (pH 5.8) | 0.047 | 1.19 |

| ADPase (pH 5.8) | 0.014 | 0.38 |

| AMPase (pH 5.8) | 0.10 | 3.02 |

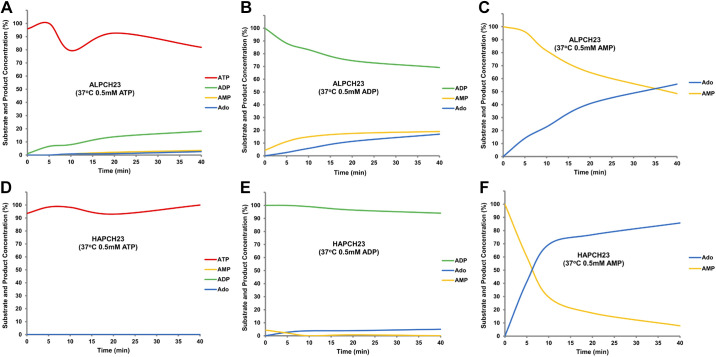

As shown in Fig. 5A and Table 6, the human alkaline phosphatase fusion protein, ALPCH23, had AMPase activity that was more than 55-fold lower than that of the bifunctional fusions at pH 7.5 (Km, 0.078 mM; Vmax, 0.20 µmol/nmol/min) and pH 9.0 (Km, 0.14 mM; Vmax, 0.42 µmol/nmol/min), with little activity at pH 5.8. It did exhibit some ATPDase activity at neutral, acidic, and alkaline conditions (Vmax, 0.1–0.23 µmol/nmol/min), yet this was 10- to 20-fold lower than those of the bifunctional fusions (Fig. 5B and Table 6).

Figure 5.

Enzymatic characterization of ALPCH23 fusion and HAPCH23 fusion. Either ALPCH23 (A–C) or HAPCH23 (D and E) was measured for colorimetric NTPDase and NMPase activity assays. In all, 200 ng of the fusion proteins was used for the reaction at 37°C for 10 min. The error bars at each data point (n = 3) are standard deviations, as calculated from experiments run in triplicate. NMPase, ecto-5′-nucleotidase; NTPDase, nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase.

Table 6.

Vmax and Km of ALPCH23 at various pH levels for NTPDase and NMPase activities

| ALP-CH23 | Km, mM | Vmax, µmol Pi/nmol/min |

|---|---|---|

| AMPase (pH 9.0) | 0.14 | 0.42 |

| AMPase (pH 7.5) | 0.078 | 0.20 |

| AMPase (pH 5.8) | N/A | N/A |

| ATPase (pH 7.5) | 0.026 | 0.15 |

| ATPase (pH 5.8) | 0.0048 | 0.10 |

| ATPase (pH 9.0) | 0.090 | 0.20 |

| ADPase (pH 7.5) | 0.018 | 0.16 |

| ADPase (pH 5.8) | 0.024 | 0.14 |

| ADPase (pH 9.0) | 0.038 | 0.23 |

Human acidic phosphatase fusion HAPCH23 possesses ATPase (Km, 9.08 mM; Vmax, 2.21 µmol/nmol/min), ADPase (Km, 2.1 mM; Vmax, 1.91 µmol/nmol/min), and AMPase functions (Km, 2.58 mM; Vmax, 6.77 µmol/nmol/min) at acidic pH (Fig. 5, C and D, and Table 7). It had no AMPase activity detected at alkaline pH but showed some ATPase (Km, 1.42 mM; Vmax, 1.74 µmol/nmol/min) and ADPase activity (Km, 0.92 mM; Vmax, 2.37 µmol/nmol/min) (Fig. 5C and Table 7). At neutral pH, HAPCH23 displayed AMPase (Km, 2.59 mM; Vmax, 6.89 µmol/nmol/min) and ADPase activities (Km, 8.39 mM; Vmax, 1.38 µmol/nmol/min) but little ATPase activity (Fig. 5D and Table 7).

Table 7.

Vmax and Km of HAPCH23 at various pH levels for NTPDase and NMPase activities

| HAP-CH23 | Km, mM | Vmax, µmol Pi/mg/min |

|---|---|---|

| ATPase (pH 5.8) | 9.08 | 2.21 |

| ATPase (pH 7.5) | N/A | N/A |

| ATPase (pH 9.0) | 1.42 | 1.74 |

| ADPase (pH 5.8) | 2.1 | 1.91 |

| ADPase (pH 7.5) | 8.39 | 1.38 |

| ADPase (pH 9.0) | 0.92 | 2.37 |

| AMPase (pH 5.8) | 2.58 | 6.77 |

| AMPase (pH 7.5) | 2.59 | 6.89 |

| AMPase (pH 9.0) | N/A | N/A |

N/A, not applicable.

These data reflect that CD39- and CD73-containing bifunctional fusion proteins exhibit robust NTPDase and NMPase activities with a low Km and a high Vmax. The enzymes were active at physiological, acidic, and alkaline pH levels. As measured by a colorimetric assay, the bifunctional fusions were superior to alkaline phosphatase and acid phosphatase in converting triphosphate and diphosphate nucleosides into nucleosides.

HPLC kinetic analysis of bifunctional fusions and control fusion proteins.

To further understand the enzyme kinetics of the bifunctional and control fusion proteins, we performed a time course study on the ATPase, ADPase, and AMPase activities at 0 min, 5 min, 10 min, 20 min, and 40 min at 37°C at pH 7.5. Initially, 2.1 pmols of each protein was added to a 100-µL reaction with 0.5 mM of ATP, ADP, or AMP. The reaction was terminated with 5 mM of perchloride acid and subjected to high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis to quantify nucleotide and nucleoside products.

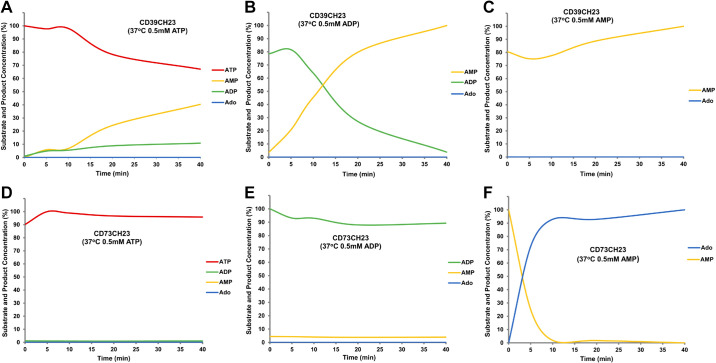

As shown in Fig. 6A, CD39CH23 facilitated a decrease in ATP over time and concurrent AMP accumulation; a small amount of ADP was also detected, consistent with previous studies suggesting the CD39 can release ADP as an intermediary by-product during ATP hydrolysis (5). No adenosine was detected during the reaction. Similarly, when ADP was the starting substrate, CD39CH23 depleted ADP over time and its AMP accumulated over time without the generation of adenosine (Fig. 6B). As shown in Fig. 6C, CD39CH23 lacks the ability to hydrolyze AMP, consistent with the colorimetric data. As shown in Fig. 6, D and E, CD73CH23 had no activity toward ATP and ADP, and yet, it exhibited potent enzymatic activity and hydrolyzed most of AMP within 5 min (Fig. 6F).

Figure 6.

HPLC kinetic characterization of CD39CH23 fusion and CD73CH23 fusion. In all, 2.1 pmol of either CD39CH23 (A–C) or CD73CH23 (D–F) was added to 100 µL of reaction buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 120 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 5 mM CaCl2) with 0.5 mM ATP (A and D), 0.5 mM ADP (B and E), or 0.5 mM AMP (C and F) at 37°C for 5 min, 10 min, 20 min, and 40 min. Each reaction was terminated by the addition of 5 µL of 8 M PCA in ice and then subjected to HPLC analysis. ADP, adenosine 5′-diphosphate; AMP, adenosine 5′-monophosphate; ATP, adenosine 5′-triphosphate; CD39CH23, CD39-ECD-Fc fusion; CD73CH23, human CD73-ECD-Fc fusion; HPLC, high-performance liquid chromatography; PCA, perchloric acid.

When equimolar CD39CH23 and CD73CH23 were mixed with ATP, the concentration of ATP decreased gradually and AMP, ADP, and adenosine accumulated sequentially (Fig. 7A). Similarly, with ADP as a starting substrate (Fig. 7B), the ADP was quickly hydrolyzed within 20 min with AMP concentrations accumulating, peaking, and then decreasing; the adenosine concentration increased throughout the entire reaction. When AMP was the starting substrate for a reaction with equimolar concentrations of CD39CH23 and CD73CH23 (Fig. 7C), the AMP was consumed completely within 5 min, similar to reactions with CD73CH23 alone indicating that CD39 did not interfere with the CD73-dependent hydrolysis of AMP to adenosine and inorganic phosphate.

Figure 7.

HPLC kinetic characterization of the mixture of CD39CH23 and CD73CH23 and the bifunctional fusion CD73CH23CD39. The mixture of 2.1 pmol CD39CH23 and 2.1 pmol CD73CH23 (A–C) or 2.1 pmol bifunctional fusion CD73CH23CD39 (D–F) was added to 100 µL of reaction buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 120 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 5 mM CaCl2) with 0.5 mM ATP (A and D), 0.5 mM ADP (B and E), or 0.5 mM AMP (C and F) at 37°C for 5 min, 10 min, 20 min, and 40 min. Each reaction was terminated by the addition of 5 µL 8 M PCA in ice and then subjected to HPLC analysis. ADP, adenosine 5′-diphosphate; AMP, adenosine 5′-monophosphate; ATP, adenosine 5′-triphosphate; CD39CH23, CD39-ECD-Fc fusion; CD73CH23, human CD73-ECD-Fc fusion; EDTA, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid; PCA, perchloride acid.

The HPLC kinetic profile for the bifunctional enzyme CD73CH23CD39 reactions with adenosine nucleotides was similar to that of the CD39CH23 and CD73CH23 mixture (Fig. 7, D–F). With a starting substrate of ATP (Fig. 7D), the CD73CH23CD39-dependent accumulation of ADP, AMP, and adenosine occurred at a slightly slower rate than that of the CD73 and CD39 mixture. Similarly, with ADP as the starting substrate for CD73CH23CD39 hydrolysis (Fig. 7E), the AMP concentration reached its peak in 20 min as compared with 10 min for the mixture. The accumulation of adenosine was also delayed proportionally when compared with that of the enzymatic mixture. AMP was completely consumed when incubated with CD73CH23CH39 in a similar amount of time when AMP was incubated with CD73CH23 (Fig. 7F), suggesting that the delay in enzyme kinetics was not due to a decrease in CD73 functional activity.

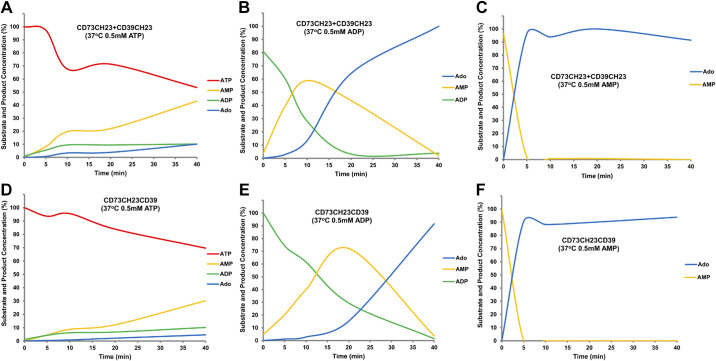

Activity of the alkaline phosphatase fusion protein (Fig. 8, A–C) toward ATP was slower than that of CD73CH23CD39 or purified CD39CH23 and, in contrast to enzymes containing CD39, ADP accumulated (Fig. 8A). Turnover of ADP (Fig. 8B) was slightly greater than that of ATP (Fig. 8A). In all cases, whether starting with ATP, ADP, or AMP as an initial substrate (Fig. 8, A–C), adenosine as a degradation product was identified. The acid phosphatase fusion (Fig. 8, D–F) did not exhibit ATP hydrolysis (Fig. 8D), consistent with the colorimetric data; however, it did have the ability to catalyze the formation of AMP and subsequently adenosine from ADP as the starting substrate (Fig. 8E). This was also observed when AMP was the starting substrate (Fig. 8F) and nearly 50% of the initial AMP concentration was consumed within 10 min, a significantly faster rate of conversion compared with alkaline phosphatase.

Figure 8.

HPLC kinetic characterization of ALPCH23 fusion and HAPCH23 fusion. In all, 2.1 pmol of either ALPCH23 (A–C) or HAPCH23 (D–F) was added to 100 µL of reaction buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 120 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 5 mM CaCl2) with 0.5 mM ATP (A and D), 0.5 mM ADP (B and E), or 0.5 mM AMP (C and F) at 37°C for 5 min, 10 min, 20 min, and 40 min. Each reaction was terminated by the addition of 5 µL of 8 M PCA in ice and then subjected to HPLC analysis. ADP, adenosine 5′-diphosphate; AMP, adenosine 5′-monophosphate; ATP, adenosine 5′-triphosphate; EDTA, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid; HPLC, high-performance liquid chromatography; PCA, perchloride acid.

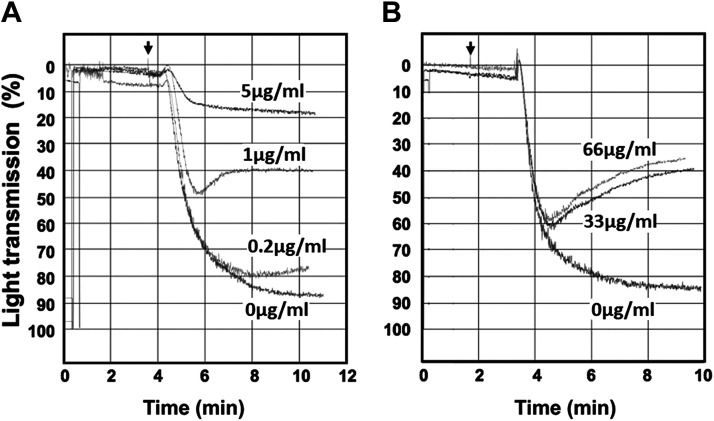

Platelet aggregation in vitro inhibited by CD39CD73 bifunctional fusion protein.

The initiation of platelet aggregation and clumping is a multifactorial pathway that is influenced by the ADP-dependent receptors P2Y1, P2Y12, and P2X1, as well as collagen acting through integrin α2β1 with surface glycoprotein VI and TRAP-6 acting through the thrombin receptor. Here, we assessed platelet aggregation in the presence of two agonists, collagen and TRAP-6, with aggregation measured by increase in light transmission with respect to the effects of CD73CH23CD39 on these reactions. As previously published (34), 2 µg/mL collagen initiates platelet aggregation, and treatment with the CD73CH23CD39 bifunctional fusion at the concentrations of 0.2, 1, or 5 µg/mL inhibited the collagen-induced platelet aggregation. Similarly, treatment with the CD73CH23CD39 bifunctional fusion at concentrations of 33 µg/mL or 66 µg/mL inhibited the platelet aggregation induced by 12.5 mM of TRAP-6 (Fig. 9B). These data together demonstrate that CD73CH23CD39-induced ADP phosphohydrolysis, in modulating platelet P2 receptor-dependent pathways, is highly effective at inhibiting platelet aggregation.

Figure 9.

Platelet function in vitro was inhibited by CD39CD73 bifunctional fusion protein. The CD73CH21CD39 recombinant fusion protein was added to donor platelet preparations, 2 min before adding either collagen or TRAP-6 agonists. Arrow: agonist addition. A: collagen 2 µg/mL; CD39-CD73 bifunctional fusion protein at concentrations depicted. B: TRAP-6 12.5 nM; CD39-CD73 bifunctional fusion at depicted concentrations.

DISCUSSION

Regulating the conversion of proinflammatory ATP and ADP into immunosuppressive adenosine by multiple ectonucleotidase families casts a profound impact on inflammatory and thrombotic biological processes. By fusing the ectodomains of CD39 and CD73 into a single polypeptide, we engineered bifunctional enzymes that hydrolyzed triphosphate and diphosphate nucleotides directly into nucleosides. These engineered enzymes should simultaneously terminate P2 receptor signaling and activate P1 receptor signaling, thus bypassing spatial and temporal expression patterns, enzyme activity variation, enzyme concentration, and localization of CD39 and CD73 in different tissues and cell types. We demonstrate that the bifunctional enzymes efficiently hydrolyze ATP and ADP into adenosine via an AMP intermediate and are superior to human alkaline phosphatase and acid phosphatase. Given that the enzymes also inhibit platelet aggregation, the data suggest that the bifunctional enzymes could potentially be used as a therapeutic supplement for both reducing proinflammatory ATP and producing anti-inflammatory adenosine.

The engineered bifunctional enzymes in this study appear well behaved functionally and biochemically, even though they contain three different functional domains: the Fc domain and the ECDs of CD39 and CD73. Among four versions of the bifunctional fusion, the dumbbell-shaped form with CD39-ECD and CD73-ECD flanking an Fc domain appears to be superior to the tandem arrangement. In eukaryotic cells, multidomain proteins with different functions are quite common (45), and our data indicate that bifunctional ectonucleotidases are functional biochemically. It is intriguing that no such enzyme exists in nature as scenarios of two independent proteins and a functionally similar bifunctional enzyme each existing have been identified. For instance, peptide amidation is catalyzed by two critical enzymes, peptidylglycine α-hydroxylating monooxygenase and peptidyl-α-hydroxyglycine α-amidating lyase, in some organisms, yet in higher organisms, they exist as a bifunctional single-polypeptide chain (27). An explanation for the absence of a single bifunctional enzyme could be that the separation of CD73 and CD39 or other E-NTPDase family member function into different individual proteins is for the purpose of modulating purinergic signaling in different tissues and cell types.

This study has enabled a direct enzymatic comparison among several major ectonucleotidases. The CD39-ECD had much greater phosphatase activity toward ATP and ADP than alkaline phosphatase in three pH conditions tested. Acid phosphatase had no such activities at neutral pH, whereas it had some at acidic or alkaline pH. As expected, CD73 had no ATPDase activity; however, it had the greatest NMPase activity among three enzymes compared. This activity was not affected by pH. Alkaline phosphatase had its highest activity at alkaline pH, some activity at neutral pH, and minimal activity at acidic pH. Acid phosphatase’s NMPase activity was greater than that of alkaline phosphatase in neutral pH and acidic pH. Acid phosphatase had no NMPase activity at alkaline pH. Based on our data, alkaline phosphatase is mainly an NMPase at alkaline and neutral pH and has some activity directed toward ATP and ADP. This result is in line with the data from rat and mouse alkaline phosphatase in chondrocytes (3, 32). A loss-of-function CD73 mutant gene can be compensated for by the increased expression of alkaline phosphatases (36), suggesting ALP typically functions biologically in the role of an NMPase. Acid phosphatase also exhibits primarily NMPase activity at neutral and acidic conditions, with some activity toward ATP and ADP at acidic and alkaline pH. This is consistent with the data for a mouse acid phosphatase in nociceptive neurons (35). During ATP hydrolysis, both alkaline phosphatase and acid phosphatase sequentially release reaction products of ADP, AMP, and adenosine. Our results indicate that the CD39-CD73 bifunctional fusions are the only ectonucleotidase that potently hydrolyze ATP and ADP to adenosine through an AMP intermediate under the conditions tested.

The protein engineering efforts in this study also reveal a pH sensitivity difference between the bifunctional fusion proteins and their parental domains. The CD39CH23 fusion’s ATPase activity in alkaline pH and acidic pH was higher than that in neutral pH, whereas its ADPase activity was opposite (Fig. 3B). A similar trend was also observed in the mixture of CD39CH23 and CD73CH23 (Fig. 3F). For CD73CH23, AMPase activity was not affected by pH (Fig. 3, E and F). For the bifunctional fusions, the activities of ATPase, ADPase, and AMPase in neutral pH were the highest (Fig. 4). Moreover, other ectoenzymatic property differences were observed between monofunctional fusions and bifunctional functions. The Km for ATPase and ADPase of the bifunctional fusions was significantly lower than the mono-functional function (Table 1 vs. Tables 4 and 5), whereas the AMPase activity difference was marginal (Table 2 vs. Tables 4 and 5). These results suggest that CD39’s NTPDase activity was more affected by the bifunctional fusions than CD73’s NMPase activity. The investigation detected low-molecular-weight species in the purifications of some bifunctional fusions, but the mixture activity was not affected, consistent with previous reports that clipping of CD39 at its COOH-terminus by trypsin does not affect its activity (33).

The study has suggested that bifunctional enzymes should presumably have therapeutic applications. Similar to soluble CD39, the bifunctional fusion could inhibit inappropriate platelet activation causing myocardial infarction, restenosis after angioplasty, and stroke (2, 15). Due to concurrent expression of the P1 receptor in platelets (16, 37), adenosine generated by the bifunctional fusions should further inhibit platelet activation and aggregation. Further, tissue injury often results in inflammation (40) with ATP released from damaged cells activating P2 receptors on all immune cells and triggering proinflammatory responses. The bifunctional fusions not only terminate these responses but also generate immunosuppressive adenosine. This bifunctional fusion activity could be used to treat patients with acute elevations in blood pressure (31). The nucleosides generated by ectonucleotide catalysts are key mediators of vasculature activity. When sympathetic nerves release ATP, it binds to P2X receptors that result in the constriction of vascular smooth muscle tissue by breaking down extracellular ATP and decreasing P2X receptor agonism, thereby stopping a rise in blood pressure. In addition, adenosine itself causes vasodilatation through the binding of adenosine to smooth muscle P1 receptors. The bifunctional fusion could therefore decrease blood pressure by decreasing extracellular ATP concentration while also increasing extracellular adenosine concentration.

In conclusion, a bifunctional enzyme that catalyzes extracellular nucleotides by sequential phosphohydrolysis was engineered by fusing the ectodomains of CD39 and CD73. When compared with the human alkaline phosphatase and acid phosphatase constructs, this bifunctional ectoenzyme was superior in converting triphosphate and diphosphate nucleotides into nucleosides. The ectoenzyme exhibited, with favorable effect, differential pH sensitivity and enzymatic properties from the parental molecules. This CD39-CD73 construct was found to be highly active in platelet aggregation assays, suggesting that the bifunctional enzyme could potentially serve as an anti-inflammatory therapeutic agent to convert proinflammatory extracellular ATP into anti-inflammatory adenosine.

GRANTS

This work was supported by the NIH (R21 CA164970 to S. C. Robson) and Department of Defense Award (W81XWH-16-0464 to S. C. Robson; R01 HD-098363 and R35 GM-136429 to W. Junger).

DISCLOSURES

S. C. Robson is a consultant to Tizona and scientific founder of Purinomia and ePURINES, where interests are in the development of purines as mediators of inflammation in cancer, renal-liver disease, and metabolic syndrome. None of the other authors has any conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

E.H.Z. and S.C.R. conceived and designed research; E.H.Z., C.L., P.D.A.M., K.E., and J.M.L. performed experiments; E.H.Z., P.D.A.M., K.E., J.M.L., and S.C.R. analyzed data; E.H.Z., C.L., P.D.A.M., K.E., W.J., and S.C.R. interpreted results of experiments; E.H.Z., C.L., P.D.A.M., and K.E. prepared figures; E.H.Z. and S.C.R. drafted manuscript; E.H.Z., C.L., K.E., J.M.L., W.J., and S.C.R. edited and revised manuscript; E.H.Z., C.L., P.D.A.M., K.E., J.M.L., W.J., and S.C.R. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank all Robson and Junger laboratory members for technical support and discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allard B, Longhi MS, Robson SC, Stagg J. The ectonucleotidases CD39 and CD73: novel checkpoint inhibitor targets. Immunol Rev 276: 121–144, 2017. doi: 10.1111/imr.12528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atkinson B, Dwyer K, Enjyoji K, Robson SC. Ecto-nucleotidases of the CD39/NTPDase family modulate platelet activation and thrombus formation: potential as therapeutic targets. Blood Cells Mol Dis 36: 217–222, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2005.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bessueille L, Briolay A, Como J, Mebarek S, Mansouri C, Gleizes M, El Jamal A, Buchet R, Dumontet C, Matera EL, Mornet E, Millan JL, Fonta C, Magne D. Tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase is an anti-inflammatory nucleotidase. Bone 133: 115262, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2020.115262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burnstock G, Knight GE. Cell culture: complications due to mechanical release of ATP and activation of purinoceptors. Cell Tissue Res 370: 1–11, 2017. doi: 10.1007/s00441-017-2618-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen W, Guidotti G. Soluble apyrases release ADP during ATP hydrolysis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 282: 90–95, 2001. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colgan SP, Eltzschig HK, Eckle T, Thompson LF. Physiological roles for ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73). Purinergic Signal 2: 351–360, 2006. doi: 10.1007/s11302-005-5302-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corriden R, Insel PA. Basal release of ATP: an autocrine-paracrine mechanism for cell regulation. Sci Signal 3: re1, 2010. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.3104re1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Csóka B, Németh ZH, Törő G, Koscsó B, Kókai E, Robson SC, Enjyoji K, Rolandelli RH, Erdélyi K, Pacher P, Haskó G. CD39 improves survival in microbial sepsis by attenuating systemic inflammation. FASEB J 29: 25–36, 2015. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-253567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Di Virgilio F, Sarti AC, Coutinho-Silva R. Purinergic signaling, DAMPs, and inflammation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 318: C832–C835, 2020. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00053.2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dubyak GR, el-Moatassim C. Signal transduction via P2-purinergic receptors for extracellular ATP and other nucleotides. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 265: C577–C606, 1993. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.265.3.C577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eckle T, Füllbier L, Wehrmann M, Khoury J, Mittelbronn M, Ibla J, Rosenberger P, Eltzschig HK. Identification of ectonucleotidases CD39 and CD73 in innate protection during acute lung injury. J Immunol 178: 8127–8137, 2007. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.8127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eltzschig HK, Sitkovsky MV, Robson SC. Purinergic signaling during inflammation. N Engl J Med 367: 2322–2333, 2012. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1205750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faas MM, Sáez T, de Vos P. Extracellular ATP and adenosine: the Yin and Yang in immune responses? Mol Aspects Med 55: 9–19, 2017. [Erratum in Mol Aspects Med 57: 30, 2017]. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2017.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fredholm BB, IJzerman AP, Jacobson KA, Linden J, Müller CE. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXXI. Nomenclature and classification of adenosine receptors–an update. Pharmacol Rev 63: 1–34, 2011. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.003285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gayle RB III, Maliszewski CR, Gimpel SD, Schoenborn MA, Caspary RG, Richards C, Brasel K, Price V, Drosopoulos JH, Islam N, Alyonycheva TN, Broekman MJ, Marcus AJ. Inhibition of platelet function by recombinant soluble ecto-ADPase/CD39. J Clin Invest 101: 1851–1859, 1998. doi: 10.1172/JCI1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haskó G, Csóka B, Koscsó B, Chandra R, Pacher P, Thompson LF, Deitch EA, Spolarics Z, Virág L, Gergely P, Rolandelli RH, Németh ZH. Ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) decreases mortality and organ injury in sepsis. J Immunol 187: 4256–4267, 2011. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoylaerts MF, Ding L, Narisawa S, Van Kerckhoven S, Millan JL. Mammalian alkaline phosphatase catalysis requires active site structure stabilization via the N-terminal amino acid microenvironment. Biochemistry 45: 9756–9766, 2006. doi: 10.1021/bi052471+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoylaerts MF, Manes T, Millán JL. Mammalian alkaline phosphatases are allosteric enzymes. J Biol Chem 272: 22781–22787, 1997. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.36.22781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Junger WG. Immune cell regulation by autocrine purinergic signalling. Nat Rev Immunol 11: 201–212, 2011. doi: 10.1038/nri2938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaczmarek E, Koziak K, Sévigny J, Siegel JB, Anrather J, Beaudoin AR, Bach FH, Robson SC. Identification and characterization of CD39/vascular ATP diphosphohydrolase. J Biol Chem 271: 33116–33122, 1996. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.51.33116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knapp K, Zebisch M, Pippel J, El-Tayeb A, Müller CE, Sträter N. Crystal structure of the human ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73): insights into the regulation of purinergic signaling. Structure 20: 2161–2173, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lanzetta PA, Alvarez LJ, Reinach PS, Candia OA. An improved assay for nanomole amounts of inorganic phosphate. Anal Biochem 100: 95–97, 1979. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90115-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Le Du MH, Stigbrand T, Taussig MJ, Menez A, Stura EA. Crystal structure of alkaline phosphatase from human placenta at 1.8 A resolution. Implication for a substrate specificity. J Biol Chem 276: 9158–9165, 2001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009250200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Linden J. Molecular approach to adenosine receptors: receptor-mediated mechanisms of tissue protection. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 41: 775–787, 2001. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Llinas P, Stura EA, Ménez A, Kiss Z, Stigbrand T, Millán JL, Le Du MH. Structural studies of human placental alkaline phosphatase in complex with functional ligands. J Mol Biol 350: 441–451, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.04.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Praetorius HA, Leipziger J. ATP release from non-excitable cells. Purinergic Signal 5: 433–446, 2009. doi: 10.1007/s11302-009-9146-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prigge ST, Mains RE, Eipper BA, Amzel LM. New insights into copper monooxygenases and peptide amidation: structure, mechanism and function. Cell Mol Life Sci 57: 1236–1259, 2000. doi: 10.1007/PL00000763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quintero IB, Araujo CL, Pulkka AE, Wirkkala RS, Herrala AM, Eskelinen EL, Jokitalo E, Hellström PA, Tuominen HJ, Hirvikoski PP, Vihko PT. Prostatic acid phosphatase is not a prostate specific target. Cancer Res 67: 6549–6554, 2007. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raghavan M, Bonagura VR, Morrison SL, Bjorkman PJ. Analysis of the pH dependence of the neonatal Fc receptor/immunoglobulin G interaction using antibody and receptor variants. Biochemistry 34: 14649–14657, 1995. doi: 10.1021/bi00045a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ralevic V, Burnstock G. Receptors for purines and pyrimidines. Pharmacol Rev 50: 413–492, 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robson SC, Sévigny J, Zimmermann H. The E-NTPDase family of ectonucleotidases: structure function relationships and pathophysiological significance. Purinergic Signal 2: 409–430, 2006. doi: 10.1007/s11302-006-9003-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Say JC, Ciuffi K, Furriel RP, Ciancaglini P, Leone FA. Alkaline phosphatase from rat osseous plates: purification and biochemical characterization of a soluble form. Biochim Biophys Acta 1074: 256–262, 1991. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(91)90161-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schulte am Esch J II, Sévigny J, Kaczmarek E, Siegel JB, Imai M, Koziak K, Beaudoin AR, Robson SC. Structural elements and limited proteolysis of CD39 influence ATP diphosphohydrolase activity. Biochemistry 38: 2248–2258, 1999. doi: 10.1021/bi982426k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sévigny J, Sundberg C, Braun N, Guckelberger O, Csizmadia E, Qawi I, Imai M, Zimmermann H, Robson SC. Differential catalytic properties and vascular topography of murine nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase 1 (NTPDase1) and NTPDase2 have implications for thromboregulation. Blood 99: 2801–2809, 2002. doi: 10.1182/blood.V99.8.2801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sowa NA, Vadakkan KI, Zylka MJ. Recombinant mouse PAP has pH-dependent ectonucleotidase activity and acts through A(1)-adenosine receptors to mediate antinociception. PLoS One 4: e4248, 2009. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.St Hilaire C, Ziegler SG, Markello TC, Brusco A, Groden C, Gill F, Carlson-Donohoe H, Lederman RJ, Chen MY, Yang D, Siegenthaler MP, Arduino C, Mancini C, Freudenthal B, Stanescu HC, Zdebik AA, Chaganti RK, Nussbaum RL, Kleta R, Gahl WA, Boehm M. NT5E mutations and arterial calcifications. N Engl J Med 364: 432–442, 2011. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stagg J, Smyth MJ. Extracellular adenosine triphosphate and adenosine in cancer. Oncogene 29: 5346–5358, 2010. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stefan C, Jansen S, Bollen M. Modulation of purinergic signaling by NPP-type ectophosphodiesterases. Purinergic Signal 2: 361–370, 2006. doi: 10.1007/s11302-005-5303-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Trautmann A. Extracellular ATP in the immune system: more than just a “danger signal”. Sci Signal 2: pe6, 2009. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.256pe6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vuerich M, Harshe RP, Robson SC, Longhi MS. Dysregulation of adenosinergic signaling in systemic and organ-specific autoimmunity. Int J Mol Sci 20: 528, 2019. doi: 10.3390/ijms20030528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang TF, Ou Y, Guidotti G. The transmembrane domains of ectoapyrase (CD39) affect its enzymatic activity and quaternary structure. J Biol Chem 273: 24814–24821, 1998. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.38.24814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yegutkin GG. Nucleotide- and nucleoside-converting ectoenzymes: important modulators of purinergic signalling cascade. Biochim Biophys Acta 1783: 673–694, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zebisch M, Krauss M, Schäfer P, Sträter N. Crystallographic evidence for a domain motion in rat nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase (NTPDase) 1. J Mol Biol 415: 288–306, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhong AH, Gordon Jiang Z, Cummings RD, Robson SC. Various N-glycoforms differentially upregulate E-NTPDase activity of the NTPDase3/CD39L3 ecto-enzymatic domain. Purinergic Signal 13: 601–609, 2017. doi: 10.1007/s11302-017-9587-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhou X, Hu J, Zhang C, Zhang G, Zhang Y. Assembling multidomain protein structures through analogous global structural alignments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 116: 15930–15938, 2019. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1905068116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zimmermann H. 5′-Nucleotidase: molecular structure and functional aspects. Biochem J 285: 345–365, 1992. doi: 10.1042/bj2850345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zimmermann H, Zebisch M, Sträter N. Cellular function and molecular structure of ecto-nucleotidases. Purinergic Signal 8: 437–502, 2012. doi: 10.1007/s11302-012-9309-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zylka MJ, Sowa NA, Taylor-Blake B, Twomey MA, Herrala A, Voikar V, Vihko P. Prostatic acid phosphatase is an ectonucleotidase and suppresses pain by generating adenosine. Neuron 60: 111–122, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]