Abstract

Sarcolipin (SLN) is an inhibitor of sarco/endoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) and expressed at high levels in the ventricles of animal models for and patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD). The goal of this study was to determine whether the germline ablation of SLN expression improves cardiac SERCA function and intracellular Ca2+ (Ca2+i) handling and prevents cardiomyopathy in the mdx mouse model of DMD. Wild-type, mdx, SLN-haploinsufficient mdx (mdx:sln+/−), and SLN-deficient mdx (mdx:sln−/−) mice were used for this study. SERCA function and Ca2+i handling were determined by Ca2+ uptake assays and by measuring single-cell Ca2+ transients, respectively. Age-dependent disease progression was determined by histopathological examinations and by echocardiography in 6-, 12-, and 20-mo-old mice. Gene expression changes in the ventricles of mdx:sln+/− mice were determined by RNA-Seq analysis. SERCA function and Ca2+i cycling were improved in the ventricles of mdx:sln+/− mice. Fibrosis and necrosis were significantly decreased, and cardiac function was enhanced in the mdx:sln+/− mice until the study endpoint. The mdx:sln−/− mice also exhibited similar beneficial effects. RNA-Seq analysis identified distinct gene expression changes including the activation of the apelin pathway in the ventricles of mdx:sln+/− mice. Our findings suggest that reducing SLN expression is sufficient to improve cardiac SERCA function and Ca2+i cycling and prevent cardiomyopathy in mdx mice.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY First, reducing sarcopolin (SLN) expression improves sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ uptake and intracellular Ca2+ handling and prevents cardiomyopathy in mdx mice. Second, reducing SLN expression prevents diastolic dysfunction and improves cardiac contractility in mdx mice Third, reducing SLN expression activates apelin-mediated cardioprotective signaling pathways in mdx heart.

Keywords: calcuim, cardiomyopathy, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, mdx, sarcolipin, SR Ca2+-ATPase

INTRODUCTION

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), a severe form of muscular dystrophy is an inherited X-linked disease affecting 1 in 5,000 male births . DMD is caused by mutations in the DMD gene that encodes dystrophin, a cytoskeletal protein, which contributes to sarcolemmal stability and links the cytoskeleton to the extracellular matrix in skeletal and cardiac muscles (1–4). Although DMD is primarily classified as a neuromuscular disorder, cardiac and respiratory failures are the common causes of death (5–9). However, as respiratory support has improved, cardiomyopathy has become an increasingly important source of morbidity and mortality (10,11). There is no curative treatment for this devastating disease. The current therapeutic strategies aimed to either replace or compensate for the lack of dystrophin face difficulties in targeting cardiac tissues (12–15). Outcomes from animal model studies have also suggested that skeletal muscle rescue may not ameliorate dystrophic cardiomyopathy or vice versa (12, 16–19). Therefore, the identification of common therapeutic targets to ameliorate skeletal muscle pathology and cardiomyopathy in DMD is necessary.

The mechanisms causing dystrophic cardiomyopathy are multifactorial, and abnormal intracellular Ca2+ (Ca2+i) load is one of the key mechanisms, which also causes muscle pathogenesis in DMD (20, 21). The activity of sarco/endoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA), which plays a major role in cytosolic Ca2+ removal and muscle contraction (22), is significantly reduced in dystrophic cardiac and skeletal muscles (23, 24). Therefore, enhancing the SERCA function is anticipated to improve the Ca2+i cycling and ameliorate DMD and associated cardiomyopathy.

We have recently shown that the expression levels of sarcolipin (SLN), a 31 amino acid SR membrane protein, is significantly high in skeletal (23) and cardiac (24) muscles of DMD patients and animal models. Given the role of SLN as an inhibitor of the SERCA pump, its upregulation could cause a sustained inhibition of SR Ca2+ uptake and elevation of Ca2+i concentration in both skeletal and cardiac muscles, which may exacerbate disease pathogenesis in DMD. Consistent with this notion, the germline ablation of SLN expression mitigates severe muscular dystrophy in a dystrophin and utrophin (mdx:utr−/−)-deficient mouse model of DMD (24). However, a causal link between SLN upregulation and abnormal Ca2+i handling and their effect on the progression of cardiomyopathy in DMD has not yet been established clearly. The disease progression including cardiomyopathy is rapid in the mdx:utr−/− mice. In addition, the skeletal muscle and diaphragm are severely affected in the mdx:utr−/− mice (25, 26). Therefore, it is difficult to distinguish the role of SLN upregulation in the development of dystrophic cardiomyopathy in mdx:utr−/− mice. Thus we chose mdx as a mouse model system and tested the hypothesis that reducing SLN expression improves cardiac SERCA function and Ca2+i cycling and subsequently prevents the development of dystrophic cardiomyopathy.

METHODS

Animals

All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of New Jersey Medical School (NJMS), Rutgers University (Newark, NJ) according to the Guide to the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the United States National Institutes of Health (NIH; 8th ed., 2011). Mice were kept under a 12-h:12-h light-dark cycle with a temperature of 22–24°C and 60–70% of humidity and fed ad libitum under a normal chow diet. For echocardiography, mice were anesthetized using 2.5% avertin (0.012 mL/g body wt ip) and for tissue collection, mice were euthanized using sodium pentobarbital (150 mg/kg ip) as approved by the IACUC, NJMS, Rutgers University (Newark, NJ).

The sln−/− mice (27) and mdx mice (Jackson Labs) in the C57BL/10 background were intercrossed for five generations to obtain the wild-type (WT), mdx, SLN-haploinsufficient mdx (mdx:sln+/−), and SLN-deficient mdx (mdx:sln−/−) mice in the isogenic background before used for experiments. Mice were identified by PCR genotyping as described previously (23, 27). Both male and female mice were used for all the experiments. We used 6-mo-old mice for Ca2+ uptake, Ca2+i measurements, RNA-Seq analysis, and biochemical studies. For disease progression studies, we used 6-, 12-, and 20-mo-old mice.

SR Ca2+ Uptake

The SR Ca2+ uptake was measured following the Millipore filtration technique as previously described (28). The rate of Ca2+ uptake and the Ca2+ concentration required for EC50 were determined by nonlinear curve fitting analysis using GraphPad Prism v6.01 software.

Ca2+ Measurements

Ca2+ transient amplitude and SR Ca2+ content were measured in isolated myocytes using Ca2+ indicator Fluo-4 AM (Molecular Probes F14201) at 34–36°C, as described earlier (29). Briefly, ventricular myocytes were isolated following Langendorff heart perfusions, loaded with the Ca2+ indicator Fluo-4 AM, placed in a heated chamber on an inverted microscope, and field stimulated at 0.5 Hz to maintain consistent SR Ca2+ load. The fluorescence was excited at ∼485 nm and the emissions were measured at ∼530 nm using a Nikon Eclipse TE200 inverted microscope. Fluorescence intensity was measured as the ratio of the fluorescence (F) over the basal diastolic fluorescence (F0). The amplitude of the 10 mmol/L caffeine-induced Ca2+ transient was used as a measure of total SR Ca2+ content. Fractional SR Ca2+ release was calculated by dividing the height of the last twitch transient by the height of the caffeine transient.

Western Blot Analysis

Total protein extraction and western blotting were carried out as described before (24). Briefly, after protein transfer, the nitrocellulose membranes were stained with Ponceau S and cut into strips based on the molecular weight of each protein studied. The membrane strips were then blocked with 3% milk in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and probed overnight at 4°C using antibodies specific for SLN (anti-rabbit, 1:3,000) (30), phospholamban (PLN; anti-rabbit, 1:5,000, custom made) (30), RyR2 (anti-rabbit, 1:1,000, Thermoscientific, PA5-77717), SERCA2a (anti-rabbit, 1:5,000, custom made) (30), calsequestrin (CSQ; anti-rabbit, 1:5,000, ThermoFisher Scientific, no. PA1-913), dihydropyridine receptor-alpha (DHPRα anti-mouse, 1:1,000, Affinity Bioreagents, MA3-921), apelin (APLN; anti-rabbit, 1:500, Boster Biological Technology, PA1501), phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K; anti-rabbit, 1:1,000, CST, no. 4255), Akt (anti-rabbit, 1:1,000, CST, no. 9272), phospho-Akt (S473) (anti-rabbit, 1:1,000, CST, no. 4058) p44/42 MAPK (anti-rabbit, 1:1,000, CST, no. 9102), phospho-p44/42 MAPK (Thr202/Thr204) (anti-rabbit, 1:1,000, CST, no. 4255), myosin light chain 20 (MLC20; anti-mouse, 1:500, Sigma, M4401), sodium-calcium exchanger (NCX; anti-rabbit, 1:1,000, Novus Biologicals, no. NB 300-127), or GAPDH (anti-mouse, 1:10,000, Sigma, G8795). Membranes were incubated with appropriate secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature and visualized with SuperSignal West Dura Substrate kit (ThermoFisher Scientific) using Bio-Rad ChemiDoc MP Imaging System. Quantitation of signals was performed using Image Lab version 5.1 software and normalized to GAPDH levels.

Immunostaining

Five-micrometer formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded ventricular sections were deparaffinized with xylene and ethanol followed by antigen unmasking using Tris-HCl buffer, pH 10. The sections were washed thrice with PBS containing 0.3% Triton X-100 (PBS-T). The antigen-retrieved tissue sections were blocked with 5% BSA for an hour followed by incubation with anti-rabbit F4/80 antibody (CST, no. D2S9R) overnight at 4°C. The sections were washed with PBS-T and incubated with Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated secondary antibody (Invitrogen, A11072) at room temperature for 2 hours. DAPI was used to stain nuclei. Images were obtained using an Olympus BX51 microscope and cellSens imaging software. The percent of F4/80 positive (F4/80+) macrophages were calculated using the NIH ImageJ 1.43 u program.

Histology

Five-micrometer paraffin-embedded myocardial sections were used for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Masson’s trichrome staining. The necrotic areas containing mononuclear cells from H&E staining and fibrosis indicated by the blue-stained collagen areas by trichrome were calculated using the NIH ImageJ 1.43 u program.

Echocardiography

Echocardiography was performed on anesthetized mice using a high-resolution ultrasound machine VisualSonic/Vevo 770 system as described previously (28). The left ventricular (LV) systolic function was assessed by measuring LV interventricular septal thicknesses, LV internal dimensions (LVID), and posterior wall thicknesses at diastole and systole from M-mode images at the level of the papillary muscles. LV ejection fraction (EF) and LV fractional shortening (FS) were calculated using the software. Additionally, LV diastolic function was evaluated using Pulse Wave Doppler by imaging Transmitral inflow Doppler via an apical four-chamber view. The Doppler indexes include the ratio of peak velocity of early to the late filing of mitral inflow (E/A), deceleration time (DT) of early filling of mitral inflow, isovolumetric relaxation time (IVRT), and isovolumetric contraction time.

RNA-Seq Analysis

RNA isolation from the ventricles of 6-mo-old WT, mdx, and mdx:sln+/− mice and RNA-Seq analysis (sequenced as 42-bp paired-end reads) were performed at Active Motif. The raw fastq files obtained from the Active Motif were aligned to the mm10 assembly genome using STAR 2.6.1d. Transcripts were then quantified to mm10 Ensembl Transcripts 91. Data were normalized to a logarithmic model, and the batch effect between replicates was removed using a log normal model with shrinkage. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) analysis was done on the final filtered counts, and significant results were retained. Differential expression using GSEA, a lognormal model with shrinkage, returned the genes in each category that were found to be differentially expressed. These genes were visualized in Morpheus. To determine functional significance and upstream regulators of the genes of interest Qiagen's Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) was carried out on the differentially expressed genes (fold change = 1.5, false discovery rate = 0.1).

Data Sharing

The RNA-Seq data have been deposited under the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) Accession No. GSE144596.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA from the ventricles was extracted using the Qiagen RNA isolation kit. Complementary DNA was prepared using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The quantitative (q)RT-PCR analysis was performed using the Superscript RT-PCR kit (Invitrogen). The primer sequences used were as follows: SLN (forward, 5′-TCAGGAAGTGAAGACAAGCC-3′, reverse, 5′-GGAGCCACATAAGGAGAACG-3′), APLN (forward, 5′-GTTGCAGCATGAATCTGAGG-3′; reverse, 5′-CTGCTTTAGAAAGGCATGGG-3′), TGF-β (forward, 5′-TCAGACATTCGGGAAGCAGT-3′; reverse, 5′-ACAGCCACTCAGGCGTATC-3′), IL-1β (forward, 5′-CTCCATGAGCTTTGTACAAGG-3′; reverse, 5′-TGCTGATGTACCAGTTGGGG-3′), CD68 (forward, 5′-TTACTCTCCTGCCATCCTTCACGA-3′; reverse, 5′-CCATTTGTGGTGGGAGAAACTGTG-3′), and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; forward, 5′-GTCGTGGATCTGACGTGCC-3′; reverse, 5′-ATGCCTGCTTCACCACCTTC-3′). The mRNA levels of SLN or APLN were normalized to the mRNA levels of GAPDH.

Statistical Analysis

No samples, mice, or data points were excluded from the data analysis. Each experiment was repeated at least three times. Experiments and data analysis were carried out in a blinded manner to ensure that the results are consistent and reproducible. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism v6.01 software. Differences in values between two genotypes were determined using a two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test with Welch’s correction. Two-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni correction was used for multigroup comparison when necessary. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Reduction in SLN Expression Improves SERCA Function and Ca2+i Handling in mdx Heart

To determine the functional relevance of SLN upregulation in dystrophic cardiomyopathy, we have generated the mdx:sln+/− and mdx:sln−/− mice. The mdx:sln+/− mice breed well and both mdx:sln+/− and mdx:sln−/− had a normal life span. We used 6-mo-old mice for biochemical analysis, SR Ca2+ uptake, and Ca2+i measurements.

We first examined whether SLN deletion affected the expression of major SR Ca2+ handling proteins in the ventricles of mdx mice. There was a significant reduction in SLN mRNA expression in the ventricles of mdx:sln+/− mice (Fig. 1A). At protein levels, SLN was undetectable in the ventricles of mdx:sln+/− mice and similar to that of WT mice (Fig. 1B). The protein levels of SERCA2a, phospholamban (PLN), ryanodine receptor 2 (RyR2), calsequestrin (CSQ), dihydropyridine receptor-α (DHPRα), and sodium-calcium exchanger (NCX) were similar in the ventricles of WT, mdx, mdx:sln+/−, and mdx:sln−/− mice (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Ablation of sarcopolin (SLN) improves sarco/endoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) function and intracellular Ca2+ (Ca2+i) handling in the dystrophic myocardium. A: quantitative RT-PCR data showing the SLN mRNA levels; n = 4 mice per group. B: representative Western blots showing the protein levels of SLN, SERCA2a, PLN, ryanodine receptor 2 (RyR2), calsequestrin (CSQ), and dihydropyridine receptor α (DHPRα) in the ventricles of wild-type (WT), mdx, mdx:sln+/−, and mdx:sln−/− mice; n = 6 mice per group. Uncropped scans of the Western images are shown in Supplemental Fig. S7A. C: rate of Ca2+-dependent Ca2+ uptake (n = 4 mice per group). D–H: summarized data for twitch Ca2+transients (D), SR Ca2+ content (E), the 50% decline in the duration of twitch Ca2+ transient (T50; F), fractional SR Ca2+ release (G), and the 50% decline in the duration of caffeine-induced Ca2+ transient (Caff-T50; H), in the ventricular myocytes of WT, mdx, mdx:sln+/−, and mdx:sln−/− mice. The total number of myocytes shown within the graphs were from 4 mice per group. NS, not statistically significant. Values are means ± SE.

We next examined the SERCA activity by measuring the SR Ca2+ uptake in ventricular protein extracts. Results show that the rate (Fig. 1C) and the maximum velocity (Vmax; Supplemental Fig. S1A; all Supplemental Material is available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12690068) of Ca2+ dependent Ca2+ uptake were decreased in the ventricles of mdx mice, whereas the Vmax of Ca2+ uptake was significantly increased in the ventricles of both mdx:sln+/− and mdx:sln−/− mice. The EC50 of Ca2+ uptake was not significantly different between the ventricles of all four groups of mice (Supplemental Fig. S1B).

We then examined the Ca2+i handling properties in isolated ventricular myocytes from 6-mo-old mice. The original Ca2+ traces are shown in Supplemental Fig. S1C. Results show that both the amplitude of electrically stimulated Ca2+ transient (Fig. 1D) and the SR Ca2+ content as measured by caffeine-induced Ca2+ transients (Fig. 1E) were significantly increased in the mdx myocytes compared with that of WT controls. Furthermore, the 50% decline in the duration of twitch Ca2+ transient (T50) was significantly increased (Fig. 1F) and the fractional Ca2+ release was significantly decreased (Fig. 1G) in the mdx myocytes suggesting defects in SR Ca2+ uptake and release mechanisms. The amplitude of electrically stimulated Ca2+ transient, SR Ca2+ content, T50, and the fractional Ca2+ release were restored as close to normal in the mdx:sln+/− myocytes (Fig. 1, D–G). Although the Ca2+ transient amplitude was restored as close to normal, the SR Ca2+ content, T50, and fractional Ca2+ release were not improved in the mdx:sln−/− myocytes (Fig. 1, D–G). The 50% decline in the duration of caffeine-induced Ca2+ transient (Caff-T50) was significantly decreased only in the mdx:sln+/− myocytes (Fig. 1H).

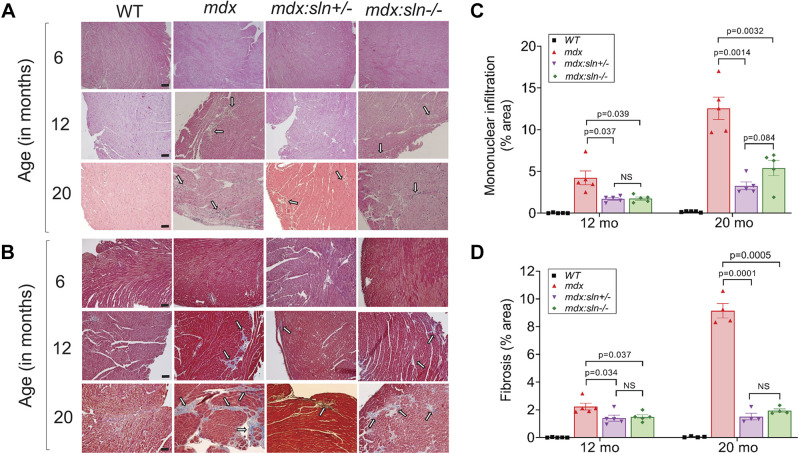

Reduction in SLN Expression Reduces Necrosis and Fibrosis in the mdx Heart

We next examined cardiac structural remodeling in mdx mice deficient for SLN at 6, 12, and 20 mo of age. Morphometric analyses show that there was no significant difference in heart weight to body weight ratio between WT, mdx, mdx:sln+/−, and mdx:sln−/− mice at all ages (Supplemental Fig. S2). H&E and trichrome staining shows no apparent cardiac pathology in 6-mo-old mdx, mdx:sln+/− and mdx:sln−/− mice (Fig. 2, A and B). At 12 mo of age, necrosis/infiltration of mononuclear inflammatory cells (Fig. 2, A and C) and fibrosis (Fig. 2, B and D) were significantly increased in mdx ventricles, particularly in the epicardial region. By 20 mo of age, necrosis (Fig. 2, A and C) and fibrosis (Fig. 2, B and D) were further increased in mdx hearts. On the other hand, cardiac necrosis and fibrosis were significantly reduced in 12- and 20-mo-old mdx:sln+/− and mdx:sln−/− mice (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Histopathological examination of the myocardium. Representative for hematoxylin and eosin (A) and Masson’s trichrome-stained (B) ventricular sections from 6-, 12-, and 20-mo-old mice. Arrow indicates mononuclear infiltration and fibrosis. Original magnification: ×10. Scale bar = 100 µm. Quantitation showing necrotic (mononuclear infiltration; C) and fibrotic areas (D) in the ventricles of 12- and 20-mo-old mice. WT, wild type; NS, not statistically significant. Values are means ± SE.

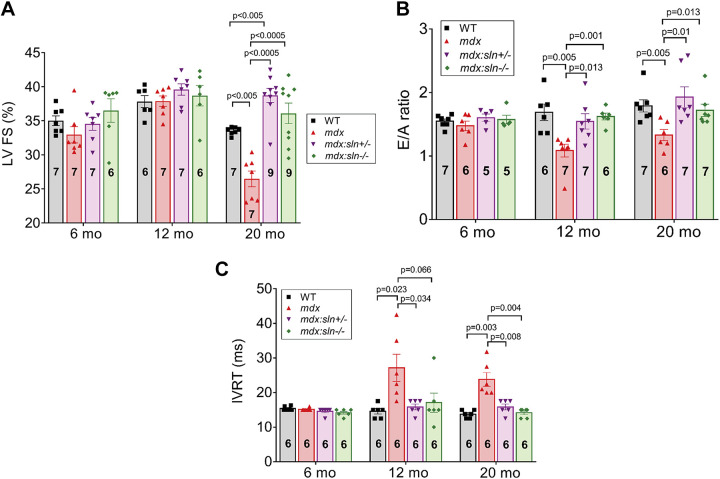

Reduction in SLN Expression Improves Cardiac Function in Aged mdx Mice

We next determined cardiac function in 6-, 12-, and 20-mo-old mice by M-mode echocardiography (Supplemental Fig. S3). At 6 and 12 mo of age, the systolic function was preserved in WT, mdx, mdx:sln+/−, and mdx:sln−/− mice compared with that of WT age-matched controls (Table 1 and Fig. 3A). At 6 mo of age, the LV diastolic function as measured by the E/A ratio (Fig. 3B) and the isovolumetric relaxation time (IVRT; Fig. 3C) was not significantly different between all four groups. On the other hand, the E/A ratio was significantly decreased (Fig. 3B) and the IVRT was significantly increased (Fig. 3C) in 12-mo-old mdx mice. The E/A ratio and IVRT were normal in 12-mo-old mdx:sln+/− and mdx:sln−/− mice and similar to that of WT controls.

Table 1.

Baseline echocardiographic data for 6- and 12-mo-old mice

| 6 Mo |

12 Mo |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measurements | WT (n = 7) | mdx (n = 7) | mdx:sln+/− (n = 7) | mdx:sln−/− (n = 6) | WT (n = 6) | mdx (n = 7) | mdx:sln+/− (n = 7) | mdx:sln−/− (n = 6) |

| IVSd, mm | 0.87 ± 0.04 | 0.95 ± 0.05 | 0.95 ± 0.03 | 0.82 ± 0.06 | 0.81 ± 0.07 | 1.05 ± 0.05 | 0.97 ± 0.04 | 1.09 ± 0.09 |

| IVSs, mm | 1.26 ± 0.05 | 1.35 ± 0.05 | 1.3 ± 0.04 | 1.23 ± 0.05 | 1.40 ± 0.05 | 1.43 ± 0.06 | 1.43 ± 0.06 | 1.56 ± 0.11 |

| LVIDd, mm | 3.84 ± 0.51 | 3.39 ± 0.14 | 3.08 ± 0.15* | 3.64 ± 0.17 | 3.42 ± 0.23 | 3.34 ± 0.06 | 3.06 ± 0.19 | 3.04 ± 0.19 |

| LVIDs, mm | 2.50 ± 0.11 | 2.29 ± 0.12 | 2.02 ± 0.09* | 2.32 ± 0.17 | 2.13 ± 0.15 | 2.05 ± 0.05 | 1.85 ± 0.12 | 1.87 ± 0.13 |

| LVPWd, mm | 0.79 ± 0.07 | 0.92 ± 0.07 | 0.99 ± 0.02 | 0.90 ± 0.08 | 0.71 ± 0.81 | 0.94 ± 0.07 | 0.94 ± 0.08 | 0.91 ± 0.09 |

| LVPWs, mm | 1.19 ± 0.05 | 1.24 ± 0.12 | 1.29 ± 0.05 | 1.24 ± 0.07 | 1.12 ± 0.05 | 1.30 ± 0.06 | 1.23 ± 0.09 | 1.24 ± 0.07 |

| FS, % | 35 ± 0.7 | 33 ± 1.2 | 35 ± 0.9 | 37 ± 1.7 | 38 ± 0.9 | 38 ± 0.8 | 40 ± 0.8 | 39 ± 1.5 |

| EF, % | 67 ± 1.1 | 69 ± 0.9 | 70 ± 0.6 | 68 ± 3.0 | 67 ± 1.2 | 68 ± 0.9 | 71 ± 0.9$$ | 69 ± 1.8 |

| HR, betas/min | 449 ± 13 | 459 ± 12 | 458 ± 12 | 480 ± 11 | 424 ± 17 | 452 ± 18 | 427 ± 20 | 434 ± 12 |

Values are means ± SE. IVSd, interventricular septal end-diastole; IVSs, interventricular septal end-systole; LVIDd, left ventricular internal diameter, end-diastole; LVIDs, left ventricular internal diameter, end-systole; LVPWd, left ventricular posterior wall, end-diastole; LVPWs- left ventricular posterior wall, end-systole; FS, fractional shortening; EF, ejection fraction; HR, heart rate; WT, wild type. *P < 0.05 vs. WT; $$P < 0.05 vs. WT and mdx.

Figure 3.

Reduction or ablation of sarcopolin (SLN) expression prevents diastolic dysfunction and improves cardiac contractility in mdx mice. Left ventricular fractional shortening (LV FS; A), early to the late filing of mitral inflow (E/A; B) ratio, and isovolumetric relaxation time (IVRT; C) in wild-type (WT), mdx, mdx:sln+/−, and mdx:sln−/− mice at 6, 12, and 20 mo of age. Values are means ± SE.

At 20 mo of age, the LV EF and FS were significantly decreased and the LV internal diameter, end-systole (LVIDs) was increased in the mdx mice (Table 2 and Fig. 3A) indicating impaired systolic function and development of dilated cardiomyopathy. In the mdx:sln+/− mice, the LV EF and FS were significantly increased in comparison with those of age-matched mdx and WT mice. On the other hand, the LV EF and FS were preserved in the mdx:sln−/− mice. The LV internal diameter, end-diastole (LVIDd), and LVIDs were significantly reduced both in mdx:sln+/− and mdx:sln−/− mice in comparison with those of WT and mdx mice (Table 2). Also, the LV posterior wall thickness, end-systole (LVPWs), and end-diastole (LVPWd) were significantly (P < 0.05) reduced in the mdx:sln−/− mice (Table 2). Doppler echocardiographic measurements showed that the E/A ratio was significantly decreased (Fig. 3B) and the IVRT was significantly increased (Fig. 3C) in 20-mo-old mdx mice compared with that of other groups.

Table 2.

Baseline echocardiographic data of 20-mo-old mice

| Measurements | WT (n = 7) | mdx (n = 7) | mdx:sln+/− (n = 9) | mdx:sln−/− (n = 9) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IVSd, mm | 0.94 ± 0.04 | 1.13 ± 0.12 | 1.06 ± 0.19 | 1.04 ± 0.08 |

| IVSs, mm | 1.37 ± 0.03 | 1.47 ± 0.09 | 1.42 ± 0.16 | 1.44 ± 0.10 |

| LVIDd, mm | 3.88 ± 0.08 | 4.05 ± 0.19 | 3.20 ± 0.20$$ | 3.18 ± 0.23$$ |

| LVIDs, mm | 2.58 ± 0.06 | 2.98 ± 0.16* | 1.95 ± 0.11$$ | 2.05 ± 0.17$$ |

| LVPWd, mm | 1.14 ± 0.02 | 1.36 ± 0.21 | 1.17 ± 0.14 | 0.80 ± 0.05* |

| LVPWs, mm | 1.61 ± 0.04 | 1.63 ± 0.16 | 1.61 ± 0.14 | 1.04 ± 0.06* |

| FS, % | 34 ± 0.2 | 26 ± 1.2** | 39 ± 1.0$ | 36 ± 1.5 |

| EF, % | 65 ± 0.7 | 56 ± 1.2** | 70 ± 1.1$ | 67 ± 2.0 |

| HR, beats/min | 457 ± 15 | 462 ± 9 | 470 ± 20 | 476 ± 10 |

Values are means ± SE. IVSd, interventricular septal end-diastole; IVSs, interventricular septal end-systole; LVIDd, left ventricular internal diameter, end-diastole; LVIDs, left ventricular internal diameter, end-systole; LVPWd, left ventricular posterior wall, end-diastole; LVPWs- left ventricular posterior wall, end-systole; FS, fractional shortening; EF, ejection fraction; HR, heart rate; WT, wild type. *P < 0.05 vs. other groups; $P < 0.005 vs. WT; **P < 0.0005 vs. other groups; $$P < 0.05 vs. WT and mdx.

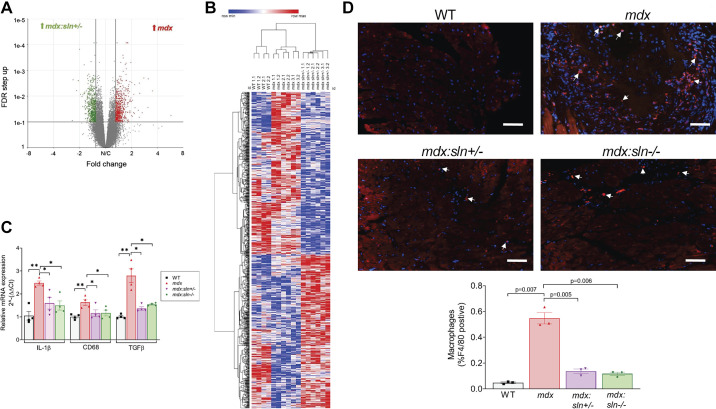

Reduction in SLN Expression Alters Gene Expression in the mdx Ventricles

To determine whether normalizing the Ca2+i cycling alters gene expression in the mdx myocardium, we studied the transcriptomic changes in the ventricles of mdx:sln+/− mice by RNA-Seq. The mRNA expression ratios between WT, mdx, and mdx:sln+/− ventricles were analyzed by the volcano plot. Results show that 1,033 transcripts were upregulated and 1,113 transcripts were downregulated in the mdx ventricles in comparison with those of WT mice (Supplemental Fig. S4A), whereas 1,097 genes were upregulated and 1,227 genes were downregulated in the mdx:sln+/− ventricles in comparison with those of WT mice (Supplemental Fig. S4B). In comparison with those of mdx mice, 620 genes were upregulated and 651 genes were downregulated in mdx:sln+/− ventricles (Fig. 4A). The t-statistic Stochastic Neighbor Embedding analysis showed that there was a clear clustering of genes between WT, mdx, and mdx:sln+/− mice (Supplemental Fig. S4C). A heat map depicting the hierarchical clustering shows that there were two clear gene clusters in the mdx:sln+/− ventricles (Fig. 4B). These clusters contained ∼35% of the differentially expressed genes between mdx and mdx:sln+/− ventricles.

Figure 4.

Inflammation is reduced in the ventricles of mdx:sln+/− and mdx:sln−/− mice. A: volcano plot of all the transcripts detected by the RNA-Seq in mdx vs mdx:sln+/− ventricles. The differentially expressed genes are marked by a line at the false discovery rate-q value of 0.01. B: heat map of differentially expressed genes from the ventricles of wild-type (WT), mdx, and mdx:sln+/− mice; n = 2 for WT and n = 3 for mdx and mdx:sln−/− mice. C: quantitative RT-PCR data showing the mRNA levels of IL-1β, CD68, and TGF-β; n = 4 mice per group. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.005. D: representative ventricular sections stained with an anti-F4/80 antibody (red) for macrophages and DAPI (blue) for nuclei. Original magnification: ×20. Scale bar = 100 µm. The bar diagram shows the quantitation of F4/80+ macrophages; n = 3 mice per group. Statistical significance was determined by unpaired Student’s t test with Welch’s correction. P values are shown within the histograms. Values are means ± SE.

Reduction in SLN Expression Reduces Cardiac Inflammation in mdx Mice

GSEA shows that TGF-β, IL-1, and TNF-α signaling pathways were increased in the mdx ventricles (Supplemental Fig. S4D), whereas autophagy, ribose phosphate, and fatty acyl-CoA biosynthetic pathways were increased in the mdx:sln+/− ventricles (Supplemental Fig. S4E). We, therefore, next examined the mRNA levels of genes involved in inflammation such as TGF-β, IL-1β, and CD68 in 6-mo-old mice. The quantitative PCR data (Fig. 4C) show that the expression levels of TGF-β, IL-1β, and CD68 were significantly increased in the mdx heart, whereas the expression levels of these genes were significantly decreased in the hearts of mdx:sln+/− and mdx:sln−/− mice. We next examined the macrophage infiltration in 20-mo-old mice hearts by immunostaining with anti-F4/80 antibody. Results show that the F4/80+ macrophages were significantly high in the mdx hearts. On the other hand, the F4/80+ macrophages infiltration was significantly decreased in both mdx:sln+/− and mdx:sln−/− hearts (Fig. 4D).

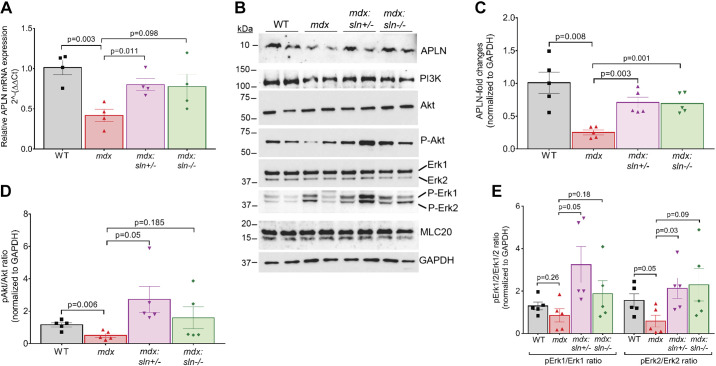

Reduction in SLN Expression Activates Apelin Signaling in mdx Hearts

We next performed pathway and upstream regulator analyses using Qiagen's Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA). These results show that the pathways associated with angiogenesis, fibrosis, and cardiac hypertrophy were affected in the mdx versus mdx:sln+/− ventricles with a Benjamini-Hochberg corrected P < 0.01 (Supplemental Fig. S4F). Many of these pathways are associated with the activation of apelin (APLN) signaling in the mdx:sln+/− ventricles. We, therefore, examined the APLN expression by qRT-PCR and Western blot analysis. Results show that the expression levels of APLN mRNA (Fig. 5A) and protein (Fig. 5, B and C) were significantly downregulated in the ventricles of mdx mice, whereas its level significantly increased in the mdx:sln+/− ventricles. IPA predicted the activation of APLN-mediated cardioprotective PI3K-Akt and p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/Erk2) pathway (Supplemental Fig. S5) in the mdx:sln+/− ventricles. We, therefore, examined the major proteins involved in this pathway by Western blot analysis. Results show that the protein levels of PI3K, Akt, Erk1/2, and MLC20 were unaltered between all four groups (Fig. 5B). However, the phosphorylation status of Akt (Fig. 5, B and D) and Erk2 (Fig. 5, B and E) was significantly reduced in the ventricles of mdx mice. The phosphorylation levels of Erk1 also decreased but not to a significant extent in the mdx ventricles (Fig. 5, B and E). On the other hand, the phosphorylation status of Akt and Erk1/2 was significantly increased in the mdx:sln+/− ventricles. There was a considerable but not a significant level increase in the phosphorylation status of Akt and Erk1/2 in the mdx:sln−/− ventricles.

Figure 5.

Apelin (APLN) pathway is activated in the ventricles of mdx:sln+/− and mdx:sln−/− mice. A: quantitative RT-PCR analysis showing APLN mRNA levels in the ventricles of wild-type (WT), mdx, mdx:sln+/− and mdx:sln−/− mice. B: representative western blots showing the protein levels of APLN, PI3K, Akt, phospho-Akt, p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/Erk2), phospho-Erk1/Erk2, myosin light chain 20 (MLC20), and GAPDH in the ventricles of WT, mdx, mdx:sln+/− and mdx:sln−/− mice. Uncropped scans of the western images are shown in Supplemental Fig. 7B. C–E: quantitation showing the APLN protein levels (C), ratio of phospho-Akt to Akt (D), and ratio of phospho-Erk1/2 to Erk1/2 (E) in the ventricles of WT, mdx, mdx:sln+/−, and mdx:sln−/− mice. P values are shown within the histograms. Values are means ± SE.

DISCUSSION

We have previously demonstrated that reducing SLN expression can ameliorate severe muscular dystrophy and cardiomyopathy phenotype in mdx:utr−/− mice. However, the disease progression in the mdx:utr−/− mice is rapid and these mice die prematurely, possibly, due to diaphragm dysfunction (25, 26, 31). Thus it is difficult to ascertain the role of SLN upregulation in the development of dystrophic cardiomyopathy in mdx:utr−/− mice. Therefore, in this study, we used the mdx mouse model of DMD and demonstrated that reducing SLN expression is sufficient to 1) improve cardiac SERCA function and Ca2+i cycling, and 2) prevent the development of dystrophic cardiomyopathy. In addition, for the first time, we have demonstrated that the APLN signaling pathway, which was impaired in the ventricles of mdx mice normalized after a reduction in SLN expression. Together these findings provide new mechanistic insights into the role of SLN upregulation in the development of dystrophic cardiomyopathy as well as the therapeutic potential of targeting SLN expression in preventing dystrophic cardiomyopathy.

Recent studies have provided a clear proof-of-concept that enhancing the SR Ca2+ uptake by overexpressing SERCA2a can improve cardiac function in mdx mice (32, 33). Despite these studies, the role of endogenous cardiac SERCA function in dystrophic cardiomyopathy is not fully explored. A recent study shows that the total loss of PLN, a key regulator of SERCA2a, significantly enhanced the Ca2+ handling in cardiac myocytes but worsened cardiac function and exacerbated cardiomyopathy in mdx mice (34). Unlike PLN, SLN expression is significantly elevated in the ventricles of mouse models and DMD patients (24) and therefore anticipated to play a key role in SERCA dysfunction and abnormal Ca2+i homeostasis in dystrophic myocardium. The present study validated this hypothesis by demonstrating that reducing SLN alone can improve the SERCA function and Ca2+i handling and prevent dystrophic cardiomyopathy.

Our findings show that the SR Ca2+ content is increased, and the T50 of Ca2+ transient decay is decreased in the cardiac myocytes of mdx mice and corroborate with a previous study (35). Although we do not know the reason/mechanism for the increased SR Ca2+ content in mdx cardiac myocytes, it is reasonable to speculate that this could be a compensatory alteration to maintain the SR Ca2+ content despite the decreased SERCA activity. In support of this notion, reduction in SLN expression improved the SERCA activity and restored the electrically stimulated Ca2+ transient amplitude, caffeine-induced Ca2+ transients, T50, and fractional Ca2+ release in the mdx cardiac myocytes. Although the total loss of SLN restored the electrically stimulated Ca2+ transient amplitude and reduced the SR Ca2+ content in mdx cardiac myocytes, T50 and fractional Ca2+ release were not significantly improved. Our earlier studies have shown that the cardiac SR Ca2+ uptake, Ca2+ transient amplitude, and fractional Ca2+ release are unaffected in the ventricular myocytes of sln−/− mice (27). Together, these findings suggest that the basal level expression of SLN may be indispensable for normal SR Ca2+ handling in dystrophin-null myocytes. However, further studies are warranted to identify the mechanisms associated with these changes in the mdx:sln−/− myocardium.

We also found that the Caff-T50 was significantly decreased in the mdx:sln+/− myocytes, suggesting increased sarcolemmal NCX activity. However, NCX protein expression was unchanged in the mdx:sln+/− hearts (Fig. 1B). Thus increased NCX activity could be due to functional protein modifications. Together our studies suggest that the functional increase in NCX may help to prevent cytosolic Ca2+ overload in the mdx:sln+/− myocytes. The disrupted transverse-tubule (T-tubule) architecture in the aged mdx heart has also been attributed to Ca2+ mishandling in the mdx heart (36). However, we did not analyze the cardiac T-tubular function in our mouse models. An extensive analysis of T-tubular architecture, as well as the simultaneous recordings of action potential and L-type Ca2+ channel function, is necessary to understand whether SLN ablation has any effect on the T-tubular remodeling in the mdx hearts.

The development of cardiomyopathy in mdx mice is progressive and takes at least 10 mo to show functional defects (35, 37). The mdx mice do not exhibit a prominent dilated cardiomyopathy phenotype but show signs of ventricular dilation upon aging (38). Consistent with these reports, the hearts of 6-mo-old mdx mice show no structural and functional abnormalities; however, they display decreased SERCA function and abnormal Ca2+i handling. At 12 mo of age, cardiac fibrosis and necrosis were more prominent and associated with diastolic dysfunction. At 20 mo, in addition to diastolic dysfunction, the mdx mice showed systolic dysfunction and increased LVIDs. These findings indicate the development of dilated cardiomyopathy in aged mdx mice. On the other hand, SLN reduction or ablation in mdx mice resulted in improved cardiac function until the study end point. A previous study demonstrated that the 22-mo-old female mdx mice develop severe systolic dysfunction in comparison with the age-matched male mdx mice (39). Consistent with these findings, our results show that the LV FS was significantly decreased in 20-mo-old female mdx mice compared with that of age-matched male mdx mice. However, there was no significant difference in LV FS between male and female mdx:sln+/− or mdx:sln−/− mice (Supplemental Fig. S6). These findings suggest that SLN ablation has a similar beneficial effect on cardiac function in both male and female mdx mice.

In mdx mice, SLN ablation is associated with decreased LVIDd and LVIDs and LVPWd and LVPWs indicating hypertrophic remodeling of the heart. These changes could contribute to the enhanced systolic and diastolic function in the mdx:sln+/− and mdx:sln−/− mice. In addition, SLN ablation prevented the age-dependent adverse cardiac structural remodeling in mdx mice, which is manifested by decreased necrosis/inflammation and fibrosis. These findings, together, suggest that cardiac remodeling in mdx:sln+/− and mdx:sln−/− mice could be beneficial rather than converting the dilated cardiomyopathy to heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. It is also important to note that the SERCA function, Ca2+i handling (27), and echocardiographic parameters (Supplemental Table S1) are not altered in the aged sln−/− mice. Thus, the above described beneficial changes associated with SLN ablation are unique for the dystrophic myocardium.

The present study for the first time demonstrates that normalizing Ca2+i cycling via SLN reduction is associated with the activation of multiple signaling pathways including apelin (APLN) signaling. Reduced levels of APLN have been reported in patients with LV hypertrophy and implicated in reduced myocyte contractility and systolic dysfunction (40). Studies using the APLN gene knockout mouse model suggest that APLN expression is important for the maintenance of cardiac structure and function during cardiac stress and aging (41–43). In rat cardiac myocytes, APLN treatment was shown to decrease the T50 of Ca2+ transient and the SR Ca2+ content and improve the SERCA function (44). Activation of the APLN receptor has also been shown to increase cardiac contractility in a p42/44 MAPK-dependent manner (45, 46). Our study shows increased expression of APLN and increased phosphorylation of Akt and p42/44 MAPKs in the mdx:sln+/− hearts. However, the current study did not show a causal link between SLN reduction and activation of APLN signaling in the mdx heart. An extended study by treating the mdx mice with an APLN peptide and/or knocking down APLN expression in mdx:sln+/− mice should be performed to validate the direct impact of SLN reduction on APLN signaling and cardiac function in mdx mice. Given these study limitations, at present, we can only speculate the possible involvement of APLN signaling in the cardiac functional improvement in mdx:sln+/− mice.

Another limitation of our study is that we only examined cardiac function in these mice. A recent study shows that the homozygous knockout for SLN exacerbates skeletal muscle pathology in mdx mice. However, these studies were restricted only to the soleus and diaphragm muscles of 3–6 mo of age (47). On the contrary, Tanihata et al. (48) have demonstrated that SLN ablation can ameliorate the cytosolic Ca2+ homeostasis and the dystrophic phenotype in mdx mice. Although we did not find the reason for these discrepancies in findings, our previous studies have also shown that the total loss of SLN is not beneficial to the diaphragm function in mdx:utr−/− mice. Nonetheless, our present study demonstrates that reducing SLN expression is not detrimental to the life of mdx mice.

In summary, our studies suggest that SLN upregulation is the major cause of SERCA dysfunction and abnormal Ca2+i handling in dystrophic myocardium. Most importantly, our findings indicate that reducing SLN expression is sufficient to restore cardiac SERCA function and prevent adverse cardiac remodeling in the mdx mouse model of DMD. Furthermore, our findings suggest that reducing SLN levels may exert cardioprotective effects through the activation of multiple signaling pathways. These findings along with our previous studies (24, 49) suggest that reducing SLN expression or activity represents a potential therapeutic strategy to ameliorate DMD and associated cardiomyopathy.

GRANTS

This work was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases Grant 1R01-AR-069107 (to G.J.B.), and American Heart Association (Founders Affiliates) Grant in Aid 16GRNT30960034 (to G.J.B.).

DISCLAIMERS

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

G.J.B., S.M., and L.-H.X. conceived and designed research; S.M., R.P., J.T., R.B., N.N., and N.F. performed experiments; S.M., R.P., J.T., R.B., N.N., and N.F. analyzed data; S.M., R.P., L.-H.X., and G.J.B. interpreted results; S.M., L.-H.X., and G.J.B drafted the manuscript; G. J. B., S.M., L-H.X., R.P., J.T., R.B., N.N., and N.F. edited and revised the manuscript; G. J. B., S.M., L-H.X., R.P., J.T., R.B., N.N., and N.F. approved the final version of the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Pranela Rameshwar and Markos H. El-Far for helping with the RNA-Seq experiments.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bonilla E, Samitt CE, Miranda AF, Hays AP, Salviati G, DiMauro S, Kunkel LM, Hoffman EP, Rowland, LP. Dystrophin muscular dystrophy: deficiency of dystrophin at the muscle cell surface. Cell 54: 447–452, 1988. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90065-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoffman EP, Brown RH, Kunkel, LM Jr.. Dystrophin: the protein product of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy locus. Cell 51: 919–928, 1987. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90579-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kornegay JN, Childers MK, Bogan DJ, Bogan JR, Nghiem P, Wang J, Fan Z, Howard JF, Schatzberg SJ Jr, Dow JL, Grange RW, Styner MA, Hoffman EP, Wagner, KR. The paradox of muscle hypertrophy in muscular dystrophy. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 23: 149–172, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2011.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matsumura K, Ervasti JM, Ohlendieck K, Kahl SD, Campbell, KP. Association of dystrophin-related protein with dystrophin-associated proteins in mdx mouse muscle. Nature 360: 588–591, 1992. doi: 10.1038/360588a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Judge DP, Kass DA, Thompson WR, Wagner, KR. Pathophysiology and therapy of cardiac dysfunction in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs 11: 287–294, 2011. doi: 10.2165/11594070-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lanza GA, Russo Giglio DA, De Luca V, Messano L, Santini L, Ricci C, Damiani E, Fumagalli A, De Martino G, Mangiola G, Bellocci, F. Impairment of cardiac autonomic function in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: relationship to myocardial and respiratory function. Am Heart J 141: 808–812, 2001. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2001.114804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mayer OH Pulmonary function and clinical correlation in DMD. Paediatr Respir Rev 30: 13–15, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2018.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Romfh A, McNally, EM. Cardiac assessment in Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophies. Curr Heart Fail Rep 7: 212–218, 2010. doi: 10.1007/s11897-010-0028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spurney CF Cardiomyopathy of Duchenne muscular dystrophy: current understanding and future directions. Muscle Nerve 44: 8–19, 2011. doi: 10.1002/mus.22097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buddhe S, Cripe L, Friedland-Little J, Kertesz N, Eghtesady P, Finder J, Hor K, Judge DP, Kinnett K, McNally EM, Raman S, Thompson WR, Wagner KR, Olson, AK. Cardiac management of the patient with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Pediatrics 142: S72–S81, 2018. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-0333I. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meyers TA, Townsend, D. Cardiac pathophysiology and the future of cardiac therapies in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Int J Mol Sci 20, 4098, 2019. doi: 10.3390/ijms20174098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bostick B, Shin JH, Yue Y, Wasala NB, Lai Y, Duan, D. AAV micro-dystrophin gene therapy alleviates stress-induced cardiac death but not myocardial fibrosis in >21-m-old mdx mice, an end-stage model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy cardiomyopathy. J Mol Cell Cardiol 53: 217–222, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bostick B, Yue Y, Long C, Marschalk N, Fine DM, Chen J, Duan, D. Cardiac expression of a mini-dystrophin that normalizes skeletal muscle force only partially restores heart function in aged Mdx mice. Mol Ther 17: 253–261, 2009. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lai Y, Duan, D. Progress in gene therapy of dystrophic heart disease. Gene Ther 19: 678–685, 2012. doi: 10.1038/gt.2012.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malik V, Rodino-Klapac LR, Mendell, JR. Emerging drugs for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs 17: 261–277, 2012. doi: 10.1517/14728214.2012.691965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bish LT, Yarchoan M, Sleeper MM, Gazzara JA, Morine KJ, Acosta P, Barton ER, Sweeney, HL. Chronic losartan administration reduces mortality and preserves cardiac but not skeletal muscle function in dystrophic mice. PLoS One 6: e20856, 2011. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ermolova NV, Martinez L, Vetrone SA, Jordan MC, Roos KP, Sweeney HL, Spencer, MJ. Long-term administration of the TNF blocking drug Remicade (cV1q) to mdx mice reduces skeletal and cardiac muscle fibrosis, but negatively impacts cardiac function. Neuromuscul Disord 24: 583–595, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jorgensen LH, Blain A, Greally E, Laval SH, Blamire AM, Davison BJ, Brinkmeier H, MacGowan GA, Schroder HD, Bushby K, Straub V, Lochmuller, H. Long-term blocking of calcium channels in mdx mice results in differential effects on heart and skeletal muscle. Am J Pathol 178: 273–283, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wasala NB, Bostick B, Yue Y, Duan, D. Exclusive skeletal muscle correction does not modulate dystrophic heart disease in the aged mdx model of Duchenne cardiomyopathy. Hum Mol Genet 22: 2634–2641, 2013. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burr AR, Molkentin, JD. Genetic evidence in the mouse solidifies the calcium hypothesis of myofiber death in muscular dystrophy. Cell Death Differ 22: 1402–1412, 2015. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2015.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Law ML, Cohen H, Martin AA, Angulski ABB, Metzger, JM. Dysregulation of calcium handling in Duchenne muscular dystrophy-associated dilated cardiomyopathy: mechanisms and experimental therapeutic strategies. J Clin Med 9: 520, 2020. doi: 10.3390/jcm9020520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Periasamy M, Kalyanasundaram, A. SERCA pump isoforms: their role in calcium transport and disease. Muscle Nerve 35: 430–442, 2007. doi: 10.1002/mus.20745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schneider JS, Shanmugam M, Gonzalez JP, Lopez H, Gordan R, Fraidenraich D, Babu, GJ. Increased sarcolipin expression and decreased sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+ uptake in skeletal muscles of mouse models of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 34: 349–356, 2013. doi: 10.1007/s10974-013-9350-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Voit A, Patel V, Pachon R, Shah V, Bakhutma M, Kohlbrenner E, McArdle JJ, Dell'Italia LJ, Mendell JR, Xie LH, Hajjar RJ, Duan D, Fraidenraich D, Babu, GJ. Reducing sarcolipin expression mitigates Duchenne muscular dystrophy and associated cardiomyopathy in mice. Nat Commun 8: 1068, 2017. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01146-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deconinck AE, Rafael JA, Skinner JA, Brown SC, Potter AC, Metzinger L, Watt DJ, Dickson JG, Tinsley JM, Davies, KE. Utrophin-dystrophin-deficient mice as a model for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cell 90: 717–727, 1997. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80532-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grady RM, Teng H, Nichol MC, Cunningham JC, Wilkinson RS, Sanes, JR. Skeletal and cardiac myopathies in mice lacking utrophin and dystrophin: a model for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cell 90: 729–738, 1997. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80533-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Babu GJ, Bhupathy P, Timofeyev V, Petrashevskaya NN, Reiser PJ, Chiamvimonvat N, Periasamy, M. Ablation of sarcolipin enhances sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium transport and atrial contractility. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104: 17867–17872, 2007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707722104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shanmugam M, Li D, Gao S, Fefelova N, Shah V, Voit A, Pachon R, Yehia G, Xie LH, Babu, GJ. Cardiac specific expression of threonine 5 to alanine mutant sarcolipin results in structural remodeling and diastolic dysfunction. PLoS One 10: e0115822, 2015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xie LH, Shanmugam M, Park JY, Zhao Z, Wen H, Tian B, Periasamy M, Babu, GJ. Ablation of sarcolipin results in atrial remodeling. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 302: C1762–C1771, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00425.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Babu GJ, Bhupathy P, Carnes CA, Billman GE, Periasamy, M. Differential expression of sarcolipin protein during muscle development and cardiac pathophysiology. J Mol Cell Cardiol 43: 215–222, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang P, Cheng G, Lu H, Aronica M, Ransohoff RM, Zhou, L. Impaired respiratory function in mdx and mdx/utrn (+/-) mice. Muscle Nerve 43: 263–267, 2011. doi: 10.1002/mus.21848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shin JH, Bostick B, Yue Y, Hajjar R, Duan, D. SERCA2a gene transfer improves electrocardiographic performance in aged mdx mice. J Transl Med 9: 132, 2011. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-9-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang NB, Yue Y, Lostal W, Wasala LP, Niranjan N, Hajjar RJ, Babu GJ, Duan, D. Single SERCA2a therapy ameliorated dilated cardiomyopathy for 18 months in a mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Mol Ther 28: 845–854, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2019.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Law ML, Prins KW, Olander ME, Metzger, JM. Exacerbation of dystrophic cardiomyopathy by phospholamban deficiency mediated chronically increased cardiac Ca2+ cycling in vivo. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 315: H1544–H1552, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00341.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Williams IA, Allen, DG. Intracellular calcium handling in ventricular myocytes from mdx mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292: H846–H855, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00688.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prins KW, Asp ML, Zhang H, Wang W, Metzger, JM. Microtubule-mediated misregulation of junctophilin-2 underlies t-tubule disruptions and calcium mishandling in mdx mice. JACC Basic Transl Sci 1: 122–130, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.jacbts.2016.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quinlan JG, Hahn HS, Wong BL, Lorenz JN, Wenisch AS, Levin, LS. Evolution of the mdx mouse cardiomyopathy: physiological and morphological findings. Neuromuscul Disord 14: 491–496, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spurney CF, Knoblach S, Pistilli EE, Nagaraju K, Martin GR, Hoffman, EP. Dystrophin-deficient cardiomyopathy in mouse: expression of Nox4 and Lox are associated with fibrosis and altered functional parameters in the heart. Neuromuscul Disord 18: 371–381, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bostick B, Yue Y, Duan, D. Gender influences cardiac function in the mdx model of Duchenne cardiomyopathy. Muscle Nerve 42: 600–603, 2010. doi: 10.1002/mus.21763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dalzell JR, Rocchiccioli JP, Weir RA, Jackson CE, Padmanabhan N, Gardner RS, Petrie MC, McMurray, JJ. The emerging potential of the apelin-APJ system in heart failure. J Card Fail 21: 489–498, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2015.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kuba K, Zhang L, Imai Y, Arab S, Chen M, Maekawa Y, , et al. Impaired heart contractility in apelin gene-deficient mice associated with aging and pressure overload. Circ Res 101: e32-42–e42, 2007. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.158659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang M, McKinnie SM, Patel VB, Haddad G, Wang Z, Zhabyeyev P, Das SK, Basu R, McLean B, Kandalam V, Penninger JM, Kassiri Z, Vederas JC, Murray AG, Oudit, GY. Loss of apelin exacerbates myocardial infarction adverse remodeling and ischemia-reperfusion injury: therapeutic potential of synthetic apelin analogues. J Am Heart Assoc 2: e000249, 2013. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang ZZ, Wang W, Jin HY, Chen X, Cheng YW, Xu YL, Song B, Penninger JM, Oudit GY, Zhong, JC. Apelin is a negative regulator of angiotensin ii-mediated adverse myocardial remodeling and dysfunction. Hypertension 70: 1165–1175, 2017. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.117.10156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang C, Du JF, Wu F, Wang, HC. Apelin decreases the SR Ca2+ content but enhances the amplitude of [Ca2+]i transient and contractions during twitches in isolated rat cardiac myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294: H2540–H2546, 2008. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00046.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Perjes A, Kilpio T, Ulvila J, Magga J, Alakoski T, Szabo Z, Vainio L, Halmetoja E, Vuolteenaho O, Petaja-Repo U, Szokodi I, Kerkela, R. Characterization of apela, a novel endogenous ligand of apelin receptor, in the adult heart. Basic Res Cardiol 111: 2, 2016. doi: 10.1007/s00395-015-0521-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Perjes A, Skoumal R, Tenhunen O, Konyi A, Simon M, Horvath IG, Kerkela R, Ruskoaho H, Szokodi, I. Apelin increases cardiac contractility via protein kinase Cepsilon- and extracellular signal-regulated kinase-dependent mechanisms. PLoS One 9: e93473, 2014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fajardo VA, Chambers PJ, Juracic ES, Rietze BA, Gamu D, Bellissimo C, Kwon F, Quadrilatero J, Russell Tupling, A. Sarcolipin deletion in mdx mice impairs calcineurin signalling and worsens dystrophic pathology. Hum Mol Genet 27: 4094–4102, 2018. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddy302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tanihata J, Nagata T, Ito N, Saito T, Nakamura A, Minamisawa S, Aoki Y, Ruegg UT, Takeda, S. Truncated dystrophin ameliorates the dystrophic phenotype of mdx mice by reducing sarcolipin-mediated SERCA inhibition. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 505: 51–59, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Niranjan N, Mareedu S, Tian Y, Kodippili K, Fefelova N, Voit A, Xie LH, Duan D, Babu, GJ. Sarcolipin overexpression impairs myogenic differentiation in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 317: C813–C824, 2019. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00146.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]