ABSTRACT

Objectives:

The aim of this study was to compare the efficacy and safety of intravenous levetiracetam and fosphenytoin in the management of pediatric status epilepticus.

Materials and Methods:

This is an open-labeled randomized controlled trial, conducted at tertiary care pediatric intensive care unit. Subjects between 1 month and 18 years who presented with status epilepticus were enrolled. If seizures persisted even after two doses of lorazepam, participants were randomized to receive either fosphenytoin 30 mg/kg or levetiracetam 30 mg/kg intravenously and followed up till 48h, for seizure recurrence and adverse drug effects. Outcome measures were cessation of seizures within 10–20 min following the end of the infusion of drugs fosphenytoin and levetiracetam, respectively, and no recurrence of seizures was noted over next 48h.

Results:

Subjects in both study groups were comparable in baseline characteristics. Seizures stopped in 54 (93.1%) and 53 (91.4%) in fosphenytoin and levetiracetam groups, respectively (P = 1.000). Seizure recurrence was noted in 13 (22.4%) and 10 (17.2%) patients in fosphenytoin and levetiracetam groups, respectively (n = 0.485). In fosphenytoin group, one (1.7%) child had bradycardia, two (3.4%) children required inotropes, and three (5.2%) children required intubation. In levetiracetam group, none had bradyarrhythmia, required inotropes, and intubation was required in one (1.7%) child each. No statistically significant difference was observed in outcome parameters in two groups.

Conclusion:

Levetiracetam is as efficacious as fosphenytoin in control of pediatric status epilepticus and is associated with lesser side effects.

KEYWORDS: Antiepileptic drugs, fosphenytoin, levetiracetam, status epilepticus

INTRODUCTION

Status epilepticus (SE) is a life-threatening condition particularly if treatment is delayed. SE is a common pediatric neurological emergency.[1] In 1993, the American Epilepsy Society Working Group on Status Epilepticus had put forward definition of SE as “seizure lasting more than 30 min or occurrence of two or more seizures without recovery of consciousness in between.”[2] Operational definition of SE refers to more than 5min of continuous seizures or two or more discrete seizures between which there is incomplete recovery of consciousness.[3] There are many antiepileptic drugs available for treatment of SE. Benzodiazepines remain the first choice;[4] seizures which do not get terminated with benzodiazepines may require second line of drugs such as phenytoin, phenobarbitone, valproate but these have serious side effects and drug interactions. Hence, these cannot be administered in children with cardiac, renal, and hepatic dysfunction, and intense monitoring during administration is required. Newer drugs, such as levetiracetam (LEV), through various studies are found to have decreased incidence of serious side effects. The results of recently published EcLiPSE trial[5] suggest that LEV could be an appropriate alternative option to phenytoin in the treatment of convulsive SE in children. Overall, evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with LEV in pediatric SE is limited especially in the developing countries. Hence, we conducted this study with the objective to compare the efficacy and adverse effects of LEV and fosphenytoin (FHP).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was undertaken in the emergency department in a tertiary care hospital. It is a randomized controlled study conducted from November 2013 to June 2015. The study group included all the children who presented with SE in the age group from 1 month to 18 years and did not respond to two doses of lorazepam 0.1 mg/kg/dose. We excluded patients who were previously on oral phenytoin and LEV for seizure prophylaxis, with known allergy to above drugs, myoclonic and absence seizures, seizures due to hypoglycemia (<50 mg/dL), hypocalcemia (serum ionized calcium: < 4.5 mg/dL), and acute hyponatremia (serum sodium: < 120 meq/dL). Randomization carried out into two groups with help of computer-generated random number list (even numbers: FHP and odd numbers: LEV); intravenous LEV 30 mg/kg over 10 min and intravenous FHP infusion 30 mg/kg over 20 min were given to children in SE. This study was approved by ethical committee. An informed consent was obtained from parents of enrolled children in the study.

Primary outcome measures were cessation of SE, defined as cessation of clinical seizures at 10/20 min following the end of the infusion of drugs LEV/FHP, respectively. Infusion started immediately after randomization. Separate person was assessed the time of randomization, initiation, and end of infusion and cession of clinical seizures. Secondary outcome measures were absence of clinical seizures in next 48h of administration of drugs and requirement of inotropes and intubation within 24h of administration of drugs. Side effects were monitored at 10 min, 24h, and 48h post-administration of drug. Side effects monitored were respiratory depression, cardiac arrhythmias, hypotension, and extravasation after intravenous administration causing purple glove syndrome in FHP group and respiratory depression, cardiac arrhythmias, hypotension, thrombocytopenia, and behavioral disturbances in both groups. Hypotension was defined as >20% reduction from baseline blood pressure. Respiratory depression was defined as >20% reduction from baseline respiratory rate. Baseline blood pressure and respiratory rate are blood pressure and respiratory rate before starting infusion. Thrombocytopenia was defined as >20% reduction in platelet count from baseline.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive and inferential statistical analysis has been carried out in this study. Results of continuous measurements are presented in mean ± standard deviation (SD) and results on categorical measurements are presented in number (%). Significance is assessed at 5% level of significance. Student’s t test (two-tailed, independent) was used to find the significance of study parameters on continuous scale between two groups (intergroup analysis) on metric parameters. Chi-square/Fisher exact test was used to find the significance of study parameters on categorical scale between two or more groups.

RESULTS

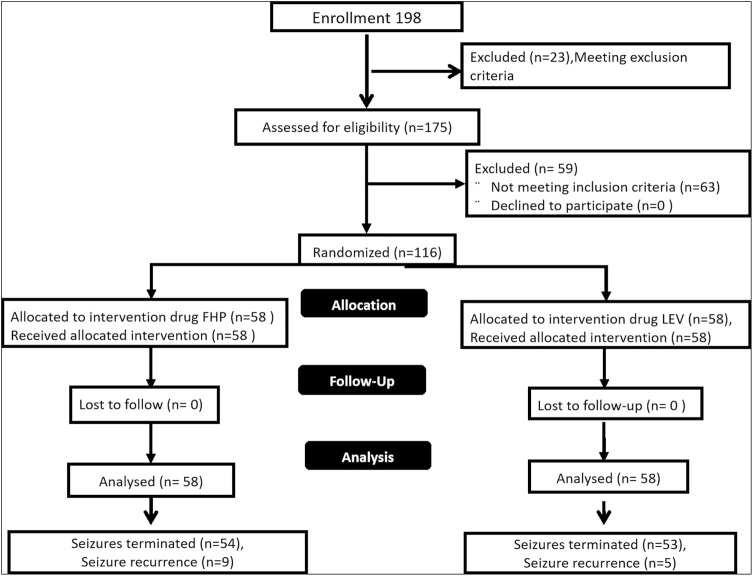

A total of 198 children were enrolled in the study, of which 82 children were excluded as they did not meet the inclusion and exclusion criteria. One hundred and sixteen children were randomized in into two groups [Figure 1]. The baseline characteristics and outcome measures are shown in Table 1. The baseline characteristics were comparable in both groups.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study populations

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and outcomes

| FHP (n = 58) | LEV (n = 58) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) mean + SD | 3.77+3.79 | 3.09+2.98 | 2.83 |

| Gender | |||

| Male n (%) | 36 (62.1%) | 32 (55.2%) | 0.498 |

| Female n (%) | 22 (37.9%) | 26 (44.8%) | |

| Seizure type | |||

| Generalized seizures n (%) | 47 (81.0%) | 44 (75.9%) | 0.430 |

| Partial seizures n (%) | 11 (19.0%) | 14 (24.1%) | |

| Duration of seizures (min) | 30.60+27.11 | 27.50+12.43 | 0.430 |

| Altered sensorium | |||

| Yes n (%) | 12 (20.7%) | 7 (12.1%) | 0.210 |

| No n (%) | 46 (79.3%) | 51 (87.9%) | |

| Past history of seizures | |||

| Yes n (%) | 10 (15.5%) | 11 (19.0%) | 0.623 |

| No n (%) | 49 (84.5%) | 47 (81.0%) | |

| Family history of seizures | |||

| Yes n (%) | 3 (5.2%) | 3 (5.2%) | 1.000 |

| No n (%) | 55 (94.8%) | 55 (94.8%) | |

| Perinatal insult | |||

| Yes n (%) | 10 (15.5%) | 10 (17.2%) | 0.802 |

| No n (%) | 49 (84.5%) | 48 (82.8%) | |

| Developmental delay | |||

| Yes n (%) | 14 (24.1%) | 15 (25.9%) | 0.830 |

| No n (%) | 44 (75.9%) | 43 (74.1%) | |

| Etiological diagnosis | |||

| Acute symptomatic | 35 (60.3%) | 28 (48.3%) | 0.192 |

| Remote symptomatic | 14 (24.1%) | 17 (29.3%) | 0.529 |

| Febrile status | 3 (5.2%) | 7 (12.1%) | 0.322 |

| Idiopathic | 5 (8.6%) | 5 (8.6%) | 1.000 |

| Cryptogenic | 1 (1.5%) | 1 (1.5%) | 1.000 |

| Primary outcome | |||

| Seizures terminated | |||

| Yes n (%) | 54 (93.1%) | 53 (91.4%) | 1.000 |

| No n (%) | 4 (6.9%) | 5 (8.6%) | |

| Secondary outcome : adverse drug reactions | |||

| Bradycardia | 1 (1.7%) | 0 | 1.000 |

| Need for inotropes | 2 (3.4%) | 1 (1.7%) | 1.000 |

| Need for intubation | 3 (5.2%) | 1 (1.7%) | 0.618 |

| Recurrence of seizures | 13 (22.4%) | 10 (17.2%) | 0.485 |

Primary outcome measure, that is, cessation of SE, was observed in 54 (93.1%) and 53 (91.4%) patients receiving FHP and LEV, respectively. No statistically significant difference in efficacy was observed between two drugs (P = 1.000). Seizure recurrence was noted in 13 (22.4%) and 10 (17.2%) patients in FHP and LEV groups, respectively (n = 0.485) and majority of the seizure reoccurrences were between 5 and 20 h after administration of the first dose of study drug. Bradyarrhythmia was noted in one patient in FHP group and none in LEV group. Inotropes were needed in two (3.4%) and one (1.7%) patients in the FHP and LEV groups, respectively. Intubation was required in three (5.2%) and one (1.7%) patients receiving FHP and LEV, respectively.

DISCUSSION

LEV is being used in SE and proved by various studies, but there are few studies comparing the efficacy of LEV with standard drugs such as FHP especially in pediatric SE. In this study, we compared the efficacy and safety of LEV and FHP in the management of pediatric SE.

The mean age of study participants was similar to reported in a study by Depositario-Cabacar et al.[6] Both the study groups predominantly had males. In seizure type, most of the children had generalized type of seizures and was comparable to another study by Chakravarthi et al.,[7] generalized 20 (90%) and focal 2 (10%). The duration of status in our study groups was lesser as compared to Chakravarthi et al. The reasons for shorter duration of seizures may be early referral, good transport facilities, initial treatment, and stabilization at the primary health center. Past history of seizures was comparatively less in this study as compared to that reported by Chakravarthi et al. The reasons may be difference in age of sample population and etiology of seizures.

Lyttle et al.[5] in recent multicenter RCT showed termination of clinical SE in 106 (70%) in the LEV group and in 86 (64%) in the phenytoin group as a second-line treatment in pediatric SE. Our study results are comparable to this multicenter RCT. Kirmani et al.[8] (n = 32) studied retrospectively efficacy of LEV as first-line drug and favorable response was seen clinically and electrographically seizure termination was observed in all study subjects. Depositario-Cabacar et al. (n = 9) (pediatric) studied use of high-dose LEV administered to patients who were having refractory SE (not responded to lorazepam, phenytoin, and phenobarbitone); seizure termination was seen in eight (88%) of study subjects. Chakravarthi et al. (n = 44) studied LEV (n = 22) versus phenytoin (n = 22) as second-line drug after failure of response to first-line lorazepam in adult patients. Seizure termination was seen in 13 (60%) of study subjects. Tripathi et al.[9] (n = 41) studied efficacy of LEV (30 mg/kg/day) versus valproate in refractory SE as second-line drugs after failure of respond to lorazepam and showed response rate of 28 (68%) to LEV in adults. Data from various studies suggest that LEV when used for treatment of SE has good response with seizure termination in 68%–100%. We also noted that adult studies have poorer results when compared to studies in pediatric age group; reason for different response in adult population is due to different etiologies, associated comorbidities, and slightly different pharmacokinetics in adult population.

Follow-up of subjects whose seizures were terminated by study drugs was carried out up to 48h after study drug administration; we observed that at 48h after administration of study drug LEV, and 17.2% of them had seizure recurrence compared to 22.4% in FHP group which indicates good seizure control which is better in comparison with other studies. Higher seizure recurrence in subjects treated with FHP was not statistically significant as compared to LEV.

In this study, in FHP group one child had bradyarrhythmia requiring discontinuation of drug and none in LEV group. Requirement of inotropes and intubation in FHP group was more as compared to those receiving LEV. Above data indicate that LEV is not associated with serious side effects. As prolonged SE can itself lead to hemodynamic instability and airway compromise requiring ventilator support, these facilities are lacking in developing countries such as India, where LEV can be considered.

Our study has some limitations. Clinical evidence of seizure termination was taken as end point due to lack of bedside EEG. Subjects with nonconvulsive status could not be assessed. Drug levels were not monitored; hence, peak concentration of drug leading on to seizure termination was not deductible.

CONCLUSION

LEV is as efficacious as FHP in control of pediatric SE with less adverse events and hence LEV is an effective alternative to FHP for management of SE in pediatric population.

Ethical policy and institutional review board statement

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from Institute Ethical Committee, Indira Gandhi Institute of Child health, Bengaluru, India.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Loddenkemper T, Goodkin HP. Treatment of pediatric status epilepticus. Curr Treat Opt Neurol. 2011;13:560–73. doi: 10.1007/s11940-011-0148-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brodie M. Status epilepticus in adults. Lancet. 1990;336:551–2. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)92098-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lowenstein DH, Bleck T, Macdonald RL. It’s time to revise the definition of status epilepticus. Epilepsia. 1999;40:120–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1999.tb02000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meierkord H, Boon P, Engelsen B, Göcke K, Shorvon S, Tinuper P, et al. EFNS guideline on the management of status epilepticus. Eur J Neurol. 2006;13:445–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lyttle MD, Rainford NEA, Gamble C, Messahel S, Humphreys A, Hickey H, et al. Paediatric Emergency Research in the United Kingdom & Ireland (PERUKI) collaborative. Levetiracetam versus phenytoin for second-line treatment of paediatric convulsive status epilepticus (eclipse): a multicentre, open-label, randomised trial. Lancet. 2019;393:2125–34. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30724-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Depositario-Cabacar DT, Peters JM, Pong AW, Roth J, Rotenberg A, Riviello JJ, Jr, et al. High-dose intravenous levetiracetam for acute seizure exacerbation in children with intractable epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2010;51:1319–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chakravarthi S, Goyal MK, Modi M, Bhalla A, Singh P. Levetiracetam versus phenytoin in management of status epilepticus. J Clin Neurosci. 2015;22:959–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2014.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kirmani BF, Crisp ED, Kayani S, Rajab H. Role of intravenous Levetiracetam in acute seizure management of children. Paediatr Neurol. 2009;41:37–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2009.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tripathi M, Vibha D, Choudhary N, Prasad K, Padma Srivastava MV, Bhatia R. Management of refractory status epilepticus at a tertiary care centre in developing country. J Seizure. 2010;19:109–11. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]