Abstract

Moral Reconation Therapy (MRT), an evidence-based intervention to reduce risk for criminal recidivism among justice-involved adults, was developed and primarily tested in correctional settings. Therefore, a better understanding of the implementation potential of MRT within non-correctional settings is needed. To address this gap in the literature, we evaluated the adoption and sustainment of MRT in the US Veterans Health Administration (VHA) following a national training initiative in fiscal years 2016 and 2017. In February 2019, surveys with 66 of the 78 VHA facilities that participated in the training were used to estimate the prevalence of MRT adoption and sustainment, and qualitative interviews with key informants from 20 facilities were used to identify factors associated with sustainment of MRT groups. Of the 66 facilities surveyed, the majority reported adopting (n = 52; 79%) and sustaining their MRT group until the time of the survey (n = 38; 58%). MRT sustainment was facilitated by strong intra-facility (e.g., between veterans justice and behavioral health services) and inter-agency collaborations (e.g., between VHA and criminal justice system stakeholders), which provided a reliable referral source to MRT groups, external incentives for patient engagement, and sufficient staffing to maintain groups. Additional facilitators of MRT sustainment were adaptations to the content and delivery of MRT for patients and screening of referrals to the groups. The findings provide guidance to clinics and healthcare systems that are seeking to implement MRT with justice-involved patient populations, and inform development of implementation strategies to be formally tested in future trials.

Keywords: Criminal recidivism, Moral reconation therapy, Justice-involved veterans, Veterans health administration, Adoption, Sustainment

Introduction

Among formerly incarcerated adults in the United States (US), criminal recidivism is the norm. Data from the US Bureau of Justice Statistics on incarcerated adults who were released from prison in 2005 found that 68 and 77% were rearrested within 3 and 5 years, respectively (Durose et al. 2014). Recidivism is also common among veterans who have been detained by, or are under the supervision of, the criminal justice system (“justice-involved veterans”). Among all veterans in the US, the rate of incarceration is 0.86%. However, among veterans in behavioral health treatment, up to 75% have been incarcerated at some point in their lifetime (Blonigen et al. 2020). Further, data from the 2011–2012 US National Inmate Survey shows that 62% of veterans in jails report four or more prior arrests and 68% of veterans in prison report at least one prior episode of incarceration (Bronson et al. 2015). Data from the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) also indicate that those served by VHA’s Veterans Justice Programs (VJP) have an average of eight arrests over their lifetime (Department of Veterans Affairs 2012). Collectively, these data suggest that many justice-involved veterans have a chronic history of criminal justice involvement and have recidivated at some point in their lifetime.

A chronic cycle of contact with the criminal justice system can limit an individual’s access to healthcare services. For example, per federal regulations, VHA cannot provide healthcare services to veterans while they are incarcerated (Department of Veterans Affairs 2011). The adverse impact of not receiving, or having intermittent, healthcare may be especially pronounced for the behavioral health of justice-involved adults, given the high rates of mental health and substance use problems in this population (Blonigen et al. 2019). Accordingly, the VHA has placed a high priority on implementing best practices for reducing criminal recidivism among their justice-involved patient population (Blue-Howells et al. 2013; Hartley and Baldwin 2019).

Best Practices for Recidivism Reduction: Moral Reconation Therapy

In the offender rehabilitation literature, cognitive-behavioral treatments are regarded as best practices for reducing criminal recidivism among justice-involved adults (Andrews and Bonta 2010). Interventions that use a treatment manual to standardize their protocol and target criminogenic thinking (i.e., antisocial attitudes, cognitions, and behaviors) have the strongest evidence for reducing recidivism risk (Aos et al. 2006; Landenberger and Lipsey 2005; Milkman and Wanberg 2007). Moral Reconation Therapy (MRT) is a cognitive-behavioral intervention that aims to modify criminogenic thinking among justice-involved adults to reduce their likelihood of criminal recidivism (Little and Robinson 1988). The intervention protocol is standardized using both a participant and provider manual to guide treatment. These manuals help participants advance through 12 steps of moral development. Participants attend groups with open enrollment (i.e., group sessions can incorporate new members at any time). Participants complete homework assignments and exercises in a workbook between group sessions and then present their work to group members at the next session. The efficacy of MRT is supported by multiple reviews, including a meta-analysis of 33 studies which found that the rate of recidivism among MRT participants is reduced by one-third relative to control samples (Ferguson and Wormith 2013).

MRT Implementation in Non-correctional Settings

MRT was originally developed for use within correctional settings in which there are strong external incentives and/or mandates to participate in the intervention. Consequently, knowledge about the implementation potential of MRT in non-correctional settings, such as VHA, is limited. Interviews with VJP specialists regarding their perceptions of the implementation potential of treatments for recidivism in VHA provide some insights by highlighting cross-service (e.g., VJP and behavioral health) and cross-system (e.g., healthcare and criminal justice system) partnerships as potential facilitators to MRT implementation in this non-correctional setting (Blonigen et al. 2018a). The broader literature on implementation of evidence-based practices for justice-involved populations also point to facility characteristics such as appropriate staffing levels (Prendergast et al. 2017), collaborations across stakeholders (Abdel-Salam et al. 2015; Green et al. 2015; Lamberti 2016), communities of practice among practitioners (Pearson et al. 2015), and partnerships with treatment courts (Abdel-Salam et al. 2015) as positively impacting adoption and sustainment of these practices.

The gap in knowledge regarding implementation of MRT in non-correctional settings is significant, given that the majority of justice-involved adults in the US are on parole or probation and reside in the community (Kaeble and Glaze 2016). In addition, there has been a policy shift in the US criminal justice system in recent years away from incarceration and towards diversion of justice-involved adults (Scott et al. 2013). Treatment courts in which justice-involved adults can participate in mental health and/or substance use treatment as an alternative to formal charges and/or incarceration are one example (Tsai et al. 2018). For example, the number of Veterans Treatment Courts have expanded rapidly over the past decade, with 128 such courts operating in 2011 and 575 operational by 2020 (Clark and Flatley 2019; Department of Veterans Affairs 2020). Healthcare systems that partner with treatment courts are often tasked with providing behavioral health services to justice-involved adults (Hartley and Baldwin 2019). In VHA, the number of veterans served by the program that coordinates with Veterans Treatment Courts increased from 18,303 in 2013 to 49,816 in 2019 (Blue-Howells et al. 2013; Department of Veterans Affairs 2020). Consequently, the responsibility of rehabilitation and recidivism reduction for justice-involved veterans is falling increasingly on the VHA.

MRT Implementation in VHA

VHA has been a national leader in the care for justice-involved adults in non-correctional settings through the work of the VJP (Clark and Flatley 2019), which provides outreach to justice-involved veterans across all points of the criminal justice system. VJP specialists link justice-involved veterans to VHA and non-VHA services to address their healthcare and psychosocial needs (Blue-Howells et al. 2013; Clark and Flatley 2019), and serve as the healthcare partner in Veterans Treatment Courts by working with VHA behavioral health and homeless services to coordinate care (McCall and Pomerance 2019; Tsai et al. 2018). In 2013, a structured evidence review of the treatment needs of justice-involved veterans that was sponsored by the VJP concluded that, among interventions that target criminogenic thinking, MRT had the strongest evidence for reducing risk for criminal recidivism (Blodgett et al. 2013). Subsequently, VJP worked to increase access to MRT for justice-involved veterans by consulting in the development of a veteran-specific version of the MRT manuals (Little and Robinson 2013). In addition, in fiscal years (FY) 2016 and 2017, the VJP supported training in MRT by providing funding for tuition and travel costs for 155 VHA providers across 78 VHA medical centers. The goal of this national training initiative was to increase the adoption of MRT in VHA homeless programs and behavioral health services system-wide.

The Current Study

The present study evaluated the adoption and sustainment of MRT at VHA medical centers following the national training initiative in FY16-17. To guide this evaluation, we used the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, and Sustainment (EPIS) framework, which describes distinct phases in the implementation of an evidence-based practice into a system (Aarons et al. 2011; Moullin et al. 2019). Consistent with this framework, we conceptualized adoption and sustainment as distinct phases in this evaluation. Specifically, adoption (corresponding to the Implementation phase of the EPIS framework) was defined as having started an MRT group after the initial training, and the adoption phase as the time period in which there was active support for the implementation of MRT (see “Training Program Overview” section). Sustainment was defined as maintenance of MRT after the active support ended (Moullin et al. 2020). Accordingly, we (1) estimated the prevalence of MRT adoption and sustainment across VHA facilities, (2) identified facility characteristics associated with MRT adoption and sustainment, and (3) used qualitative approaches to understand the facilitators and barriers to sustainment of MRT across facilities.

Methods

Training Program Overview

In July 2016, the VJP disseminated a solicitation for interest in MRT training to each of the 21 regional VHA Homeless Coordinators and Mental Health Liaisons. These individuals were asked to identify up to one VJP specialist and one behavioral health provider for training from each VHA medical facility in their region with the expectation that these individuals would jointly initiate and co-facilitate an MRT group, post training. A total of 155 individuals (77 VJP specialists; 60 behavioral health providers, 10 homeless program providers, 8 unknown) employed across 78 VHA medical facilities were supported to attend an MRT training in either FY16 (n = 139) or FY17 (n = 16). The mean number of individuals trained per facility was 1.99 (SD = 0.61; Min = 1, Max = 4). MRT trainings were provided by Correctional Counseling Inc., the copyright holder of MRT. Trainings were held in-person over four days (32 h total) at sites across the US. After this initial training, there was a period of active support by VJP for MRT implementation, which lasted approximately one year and consisted of regional calls to provide guidance on procedures for establishing the MRT groups, a community-of-practice email listserv, and a monthly call series focused on MRT group implementation. At the time of the present evaluation, this active support had been terminated for approximately 16 months.

Design and Procedures

The study used a mixed-methods approach to evaluate MRT adoption and sustainment. Of the 155 individuals who attended an MRT training, 148 who were still employed by the VHA were contacted by email in February 2019 and asked to complete a brief survey inquiring whether their site had started an MRT group after the training (i.e., adopted MRT). Respondents who had were also queried on how long the MRT group was active, if the group was currently active, and in which settings the group was implemented: behavioral health (e.g., mental health and/or substance use inpatient, residential, or outpatient treatment program), homeless programs (e.g., HUD-VASH), or a Veterans Treatment Court.

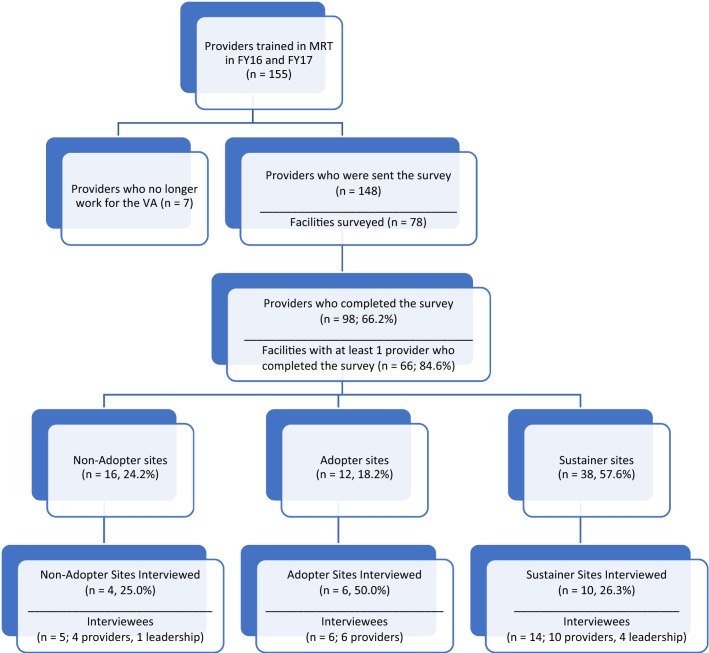

Out of 78 facilities that were contacted, 66 (84.6%) had at least one individual who completed the survey (n = 98 individuals). The survey results were used to identify which VHA facilities after the initial MRT training by Correctional Counseling Inc. (a) never started an MRT group—Non-adopters (n = 16 sites; 24.2% of facilities responding to the survey), (b) started an MRT group but discontinued the group after one year or less—Adopters (n = 12; 18.2%), or (c) adopted and sustained an MRT group until the time of the survey, with the group duration extending beyond the period of active support for implementation (i.e., more than one year)—Sustainers (n = 38, 57.6%). Following the survey, a subset of respondents from each site type (Non-adopters, Adopters, and Sustainers) participated in a one-time, semi-structured phone interview (approximately 45–60 min) to elicit perceptions of MRT and experiences with its implementation. As VHA employees, they were not able to receive financial compensation. Interviews were conducted by three trained research assistants from March 2019 to July 2019. All procedures were reviewed by the local Institutional Review Board, which determined that the study did not meet criteria for human subjects research and was exempt from further review.

Sampling Strategy

A stratified purposeful sampling strategy was used to recruit survey respondents from each site type (Non-adopters, Adopters, and Sustainers) to complete the qualitative interview. Within each site type, facility selection was based on obtaining representation across five broad geographic regions of the US: North Atlantic, Southeast, Midwest, Continental, and Pacific (Department of Veterans Affairs 2016). For Adopters and Sustainers, facility selection was also based on an effort to obtain representation across the different settings in which an MRT group was implemented at the facility. Survey respondents from selected facilities were contacted by email with a letter of invitation to participate. Recruitment continued until at least 25% of facilities in each site type (Non-adopters, Adopters, and Sustainers) had been enrolled and thematic saturation was reached (Hennink et al. 2017). At the end of the interview, participants were asked to provide the name and contact information for someone in leadership at their facility who could comment further on why MRT was (or was not) adopted by the facility. These leadership referrals were then contacted via email and invited to participate.

Data Sources

Facility Characteristics

Facilities were categorized as urban or rural (USDA Economic Research Service 2020). Records provided by VJP were used to determine (a) the number of VJP specialists employed at the facility and (b) whether a Veterans Treatment Court was affiliated with the facility’s VJP service at the time of the MRT training, as well as (c) whether a provider from that facility had joined the MRT community-of-practice listserv following the training. Facilities that had started an MRT group were categorized according to whether the group was implemented into a behavioral health program (yes/no), a homeless program (yes/no), and/or a Veterans Treatment Court (yes/no); this information was obtained from the survey.

Qualitative Interviews

In considering an implementation science framework to guide the qualitative interviews, we sought one focused on contextual factors given the study’s aim to understand MRT implementation at the facility level. Accordingly, we selected the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) since it focuses on contextual factors that can affect the implementation of new clinical practices (Damschroder et al. 2009). CFIR comprises a menu of constructs that can impact the successful implementation of an intervention and is organized into five broad domains: Characteristics of Individuals, Inner Setting, Outer Setting, Intervention Characteristics, and Implementation Process.

We adapted CFIR and used it to inform the content of the interview guide. Specifically, prior to data collection the authors reviewed the interview guide tool on the CFIR website (https://cfirguide.org) and used a consensus process to identify the domains and constructs most relevant to the intervention (i.e., MRT), patient population (i.e., justice-involved veterans), and clinical context (e.g., VHA medical centers; behavioral health and homeless programs, and Veterans Treatment Courts and other criminal justice settings). Based on prior and ongoing research on the implementation potential of MRT in VHA (Blonigen et al. 2018a, b), participants were questioned on CFIR constructs in the domains of Characteristics of Individuals (Knowledge & Beliefs about the Intervention, e.g., “What did others at your site think of your decision to attend the training?”), Inner Setting (Implementation Climate [e.g., “To what extent were people receptive to implementing MRT at your site?”], Compatibility [e.g., “How did MRT fit with existing services and treatments for justice-involved veterans at your site?”], Available Resources [e.g., “Did you have all the necessary infrastructure and resources to implement MRT such as staff, space, time?”]), Outer Setting (Patient Needs & Resources, e.g., “Tell me about how veterans were able to access MRT groups at your site.”), Intervention Characteristics (Adaptability, e.g., “Please describe any changes you made to MRT?”), and Implementation Process (Planning, Engaging, e.g., “Who was involved with implementation of MRT at your site?” “Who were the key partners to get on board with implementing MRT?”). Interviews with participants were used to better understand the implementation process at that facility. All interviews were audio-recorded (with permission) and transcribed verbatim. After each interview, the interviewer also took detailed notes by CFIR domain, which were used to summarize responses to each question.

Analysis

To examine facility characteristics associated with adoption (i.e., starting an MRT group after the initial training), we conducted 2-group univariate chi-square tests to examine if Adopter and Sustainer sites differed from Non-adopter sites on the following: urban vs. rural, number of VJP specialists employed, Veterans Treatment Court affiliation (yes/no), and provider joined community-of-practice listserv (yes/no). To examine facility characteristics associated with sustainment, we conducted 2-group univariate chi-square tests to examine if Sustainer sites differed from Adopter and Non-adopter sites on these variables. We also examined if Sustainer sites differed from Adopter sites on settings of MRT group implementation (behavioral health [yes/no], homeless program [yes/no], Veterans Treatment Court [yes/no], and whether MRT was implemented in more than one setting).

Textual data from the qualitative interviews was analyzed using the framework method, a form of thematic analysis that can be applied to deductive and/or inductive approaches (Gale et al. 2013). The defining feature of this method is use of a matrix or spreadsheet to organize the textual data in which rows refer to cases, columns refer to codes, and cells represent summaries of the data (e.g., excerpts from interview transcripts, detailed summaries of participants’ responses from interviewer notes and/or audio-recordings; Neal et al. 2015). This approach allows researchers to systematically reduce large amounts of textual data to facilitate analysis. The analytic process begins with each analyst independently coding and analyzing a subset of interviews and then meeting to compare the initial codes and themes identified. During these initial meetings, visual aids or diagrams are used to map out commonalities and differences between emergent themes from each analyst. This process continues iteratively until consensus is reached among the analysts and the final set of themes and codes is applied to the rest of the interviews.

In applying the framework method, the research team developed a matrix in Microsoft Excel, with rows being cases and columns being each question of the interview guide, grouped by CFIR domain. This first step was a deductive approach such that the CFIR domains represented an initial set of pre-defined codes from which broader, cross-cutting themes could be identified using inductive approaches. Three analysts used this matrix to conduct thematic content analysis of the textual data from the qualitative interviews. Each analyst was initially assigned a site type (i.e., Non-adopter, Adopter, Sustainer) and reviewed the detailed notes from each interview and entered the data into the relevant cell in the spreadsheet. Analysts also used the transcription of the audio-recording to fill in any gaps or missing information in the spreadsheet based on the interviewer’s notes. We then conducted thematic analysis using an inductive (emergent) approach by having each analyst independently review the data from one of the site types and identify an initial list of barrier and facilitator themes relevant to sustainment of MRT groups. The analysis was conducted across participants’ comments, not by the specific interview questions or corresponding CFIR domain. The analysts then met to review their independently-derived lists of themes, mapped out commonalities and differences between their emergent themes, and engaged in a consensus process to rectify disagreements and refined the themes to identify similarities and differences between site types. This step was facilitated by Venn diagrams to group similarities and differences by site type. Systematic comparisons were made between the different site types to identify the most robust themes that were barriers or facilitators to sustainment of MRT groups. After this initial review, a consensus list of barrier and facilitator themes to sustainment was developed and each analyst then applied those themes to a second review of the matrix, which included interviews from all site types. The analysts met again to discuss these themes and revise them into their final structure.

Results

Prevalence of MRT Adoption and Sustainment

Of the 66 facilities that responded to the survey, 52 (78.8%) reported starting an MRT group after the training (adoption), and 38 (57.6%) reported having an active MRT group at the time of the survey (sustainment) (see Table 1). Out of the 52 facilities that started a group, the majority (82.7%) reported starting only one group. On length of time groups were active, the majority (65.4%) were active for more than one year and 44.2% were active for at least 2 years. Of the 52 facilities that started a group, the majority of facilities reported that the group was implemented in a behavioral health program (71.2%), and 42.3% of facilities each reported the group was implemented in a homeless program or a Veterans Treatment Court (percentages are over 100% as MRT groups could have been implemented into more than one setting at a given site). A majority of the same 52 facilities reported only one setting in which an MRT group was implemented (58%).

Table 1.

Survey results regarding adoption of MRT post-training (n = 66 facilities)

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Facilities that started an MRT groupa | 52 (78.8%) |

| Facilities with an active group | 38 (57.6%) |

| Number of MRT groups started (out of 52) | |

| 1 group | 43 (82.7%) |

| 2+ groups | 7 (13.5%) |

| Unknown | 2 (3.8%) |

| Length of time group(s) were active (out of 52) | |

| < 6 months | 5 (9.6%) |

| 6 months–1 year | 6 (11.5%) |

| 1–2 years | 11 (21.2%) |

| 2+ years | 23 (44.2%) |

| Unknown | 7 (13.5%) |

| Settings in which an MRT group was implemented (out of 52)b | |

| Behavioral health program | 37 (71.2%) |

| Homeless program | 22 (42.3%) |

| Veterans treatment court | 22 (42.3%) |

| Unknown | 2 (3.8%) |

aTwo facilities did not indicate whether their MRT groups were active, therefore we were unable to categorize these facilities as either an Adopter or Sustainer site

bPercentages are over 100% as MRT groups could have been implemented into more than one setting at a given site

Facility Characteristics Associated with Adoption and Sustainment of MRT

Of the 66 facilities that responded to the survey, a majority were from urban areas (n = 55; 83.3%) and had a Veterans Treatment Court that was affiliated with the local VJP service at the time of the training (n = 61, 92.4%). A minority of facilities had a provider that joined the MRT community-of-practice listserv following the training (n = 28; 42.4%). On average, 1.82 VJP specialists (SD = 0.96) were employed by these facilities. In terms of facility characteristics associated with MRT adoption, Adopter and Sustainer sites were more likely than Non-adopter sites to have a provider that joined the MRT community-of-practice listserv (50 vs. 19%), χ2 = 4.85, p = 0.041. In terms of facility characteristics associated with MRT sustainment, Sustainers were more likely than Adopters to report that a Veterans Treatment Court was involved in the implementation of an MRT group at the facility (52.6 vs. 16.7%, χ2 = 4.79, p = 0.029).

Qualitative Interview Sample

Individuals from 32 facilities (11 Non-adopters, 10 Adopters, and 11 Sustainers) were contacted and invited to participate. Out of the facilities contacted, 20 (62.5%) agreed to participate (4 Non-adopters, 6 Adopters, and 10 Sustainer sites). Interview participants were 13 VJP specialists, 4 behavioral health providers, and 3 homeless service providers who had attended one of the MRT trainings. Out of 11 leadership referrals that were provided by these participants and contacted by the research team, five (45.5%) agreed to participate and included Directors of Substance Use Treatment Services, Social Work, or Homeless Services at their respective facility. In total, 25 key informants were interviewed (see Fig. 1 for a flowchart of study participation). Participants were mostly female (n = 13; 52.0%) and non-Hispanic Caucasian (n = 20; 80.0%), with a mean age of 47.44 years (SD = 10.44). Participants reported being in their current role for 4.73 years (SD = 2.82). Across the site types, participants did not differ on any of these sociodemographic variables.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of study participation

Facilitators of MRT Sustainment

Five themes characterized the sustainment of MRT groups across facilities: (1) Buy-in among VHA colleagues and leadership; (2) Multiple co-facilitators; (3) Partnerships with the criminal justice system; (4) Screening of referrals; and (5) Adaptations to intervention content and delivery. These themes are described below. Illustrative quotes are also provided below and in Table 2.

Table 2.

Facilitators of MRT sustainment

| Themes | Sample quotations |

|---|---|

| Buy-in among VHA colleagues and leadership |

I’d go to a monthly behavioral health staff meeting and we have a monthly social work staff meeting. I went to both of those meetings and presented MRT when we decided to open up and accept referrals…just to educate staff on what it was and who would be an appropriate referral. [Site ID: 309–Sustainer] It was supported by my immediate leaders. And then also the person who went with me from our site was from my substance abuse clinic, so her supervisor and chain was supportive as well. We’ll go back every now and then just to say, hey, we still have this program, don’t forget about us. [Site ID: 303–Sustainer] We sent out emails initially…and I made a lot of effort, so I tried to initiate staff, made myself available for Veterans if they were interested. I’ve done presentations too, of the social workers at our medical center. I did a lunchtime presentation about our program as well. [Site ID: 324–Sustainer] |

| Multiple co-facilitators |

[The VJOs] we co-facilitate one group together so that we can try to maintain that fidelity with each other and at least, just to keep that cohesion. [Site ID: 309–Sustainer] We added a second group that was run by myself and a co-facilitator that went to the same training I did. He joined and started a new group and co-facilitated. I think it had us communicating to make sure we had a consistent message. [Site ID: 321–Sustainer] |

| Partnerships with the criminal justice system |

They’re making it a requirement in their court that everyone participate in MRT. [Site ID: 309–Sustainer] Two of the courts actually require the Veteran to complete MRT prior to graduation. [Site ID: 327–Sustainer] I made it mandatory that any Veterans who are in the drug court have to do MRT during phase 2 because that’s when [they] have few obligations. And this keeps them on track for me to help them through the drug court. [Site ID: 304–Sustainer] |

| Screening referrals |

The way we do that in Veterans Court…it’s in phases. When they’re in Phase 1 of Veteran’s Court, they do not participate in MRT until they’re at least in Phase 2 because they need to get used to Veterans court first and then have some time of sobriety. We want them to have 90 days of recovery before starting MRT. [Site ID: 309–Sustainer] We realized that some of those Veterans were not ready for MRT and needed a level of motivational interviewing at first to identify just even a behavior or a goal that might be able to be targeted or addressed within MRT. So we changed resident referrals…a consult process to get a sense of what supports the referrals. [Site ID: 327–Sustainer] |

| Adaptations to intervention content and delivery |

We have a fishbowl, and in the fishbowl we have a mixture of inspirational quotes, as well as gift cards. Every time they complete a step they draw from the fishbowl…We also started an evening group to accommodate people who had to work. [Site ID: 309–Sustainer] We do a group that is ‘MRT informed.’ [MRT] is more shame-based than strengths-based. [MRT workbook]…I really like the activities, but some of the wording in the chapters is [shame-based]. I like to focus more on the positive…Some patients after they graduate call in and do it over the phone. [Site ID: 337–Sustainer] Not every veteran was going to be able to be face-to-face in person. Our medical center made the agreement to offer video health available at every one of our outpatient clinics to allow Veterans to appear closest to their residence and do it telephonically or through webcam to our site. [Site ID: 327–Sustainer] My Veterans court is a ways from the medical center and some of the Veterans live in outer parts of the county, so it was next to impossible for them to attend face to face meetings. We addressed that by starting a video on demand group. [Site ID: 324–Sustainer] |

Buy-in Among VHA Colleagues and Leadership

Participants at Sustainer sites described the importance of buy-in and support for MRT among colleagues and leadership at their facility. In particular, participants at all of the Sustainer sites reported that after they attended the MRT training they gave a presentation on MRT to their colleagues at their VHA facility to clarify the purpose of MRT as well as which patients would be appropriate referrals to these groups. Further, VJP specialists also specified the importance of establishing buy-in with colleagues and leadership from behavioral health services at their facilities. Participants described these outreach efforts as an ongoing process that occurred through regular meetings with colleagues and also highlighted the value of these efforts for generating referrals to the groups.

We sent out emails initially…and I made a lot of effort, so I tried to initiate staff, made myself available for Veterans if they were interested. I’ve done presentations too, of the social workers at our medical center. I did a lunchtime presentation about our program as well. [Site ID: 324–Sustainer].

Multiple Co-facilitators

Participants at Sustainer sites noted the importance of having multiple group facilitators at their facility who could deliver MRT. For example, more than half of Sustainer sites reported having at least one other individual at their facility who was also trained in MRT and had the bandwidth to help co-facilitate groups or provide coverage when the other facilitator was not available. To provide sufficient coverage, some Sustainer sites used interns or trainees. Participants at these sites also highlighted the value of multiple facilitators in terms of maintaining fidelity to the protocol and a consistent message to group participants.

We added a second group that was run by myself and a co-facilitator that went to the same training I did. He joined and started a new group and co-facilitated. I think it had us communicating to make sure we had a consistent message. [Site ID: 321–Sustainer].

Partnerships with the Criminal Justice System

Participants at Sustainer sites reported strong partnerships with the criminal justice system, particularly Veterans Treatment Courts that were staffed by VJP specialists. Participants noted the importance of such partnerships for establishing a reliable stream of referrals into their facility’s MRT groups. They also highlighted the value of these courts in terms of either incentivizing veterans’ participation in MRT (e.g., offering early graduation to court participants who completed their MRT program) or mandating veterans’ attendance at these groups as a condition for remaining in the treatment court.

They’re making it a requirement in their court that everyone participate in MRT. [Site ID: 309–Sustainer].

Screening Referrals

In addition to having reliable referral sources from VHA services and/or criminal justice system partners, participants from Sustainer sites described a process of screening the referrals they received in order to maximize the veterans’ outcomes. For example, screening was used to assess whether the veteran would be an appropriate referral based on their progress on their treatment plan as well as their recovery from substance use (e.g., the veteran was making progress on their requirements for the treatment court; the veteran had achieved sobriety for at least 90 days). In other cases, the screening process included psychoeducation to veterans on the purpose of the group and probing their internal motivations for attending these groups (e.g., conducting motivational interviewing to determine veterans’ readiness for change).

We realized that some of those Veterans were not ready for MRT and needed a level of motivational interviewing at first to identify just even a behavior or a goal that might be able to be targeted or addressed within MRT. So we changed resident referrals…a consult process to get a sense of what supports the referrals. [Site ID: 327–Sustainer].

Adaptations to Intervention Content and Delivery

Participants at Sustainer sites described various adaptations that were made to the content and/or delivery of MRT at their facility. In terms of content, adaptations were typically described as efforts to increase patient engagement in the groups. For example, one site described adding contingency management (e.g., fishbowl prize drawings) to promote attendance. Another site described modifying the curriculum to make it more strengths-based because of a perception among facility staff that the content focused too much on shame, and another site noted the addition of office hours to allow patients to receive assistance with their homework outside of regularly scheduled groups. In terms of adaptations to delivery of MRT, these were typically changes to overcome barriers to patients’ access to groups, particularly those who worked during the day (e.g., evening groups) or those living in rural settings (e.g., offering video telehealth options for attendance).

My veterans court is a ways from the medical center and some of the Veterans live in outer parts of the county, so it was next to impossible for them to attend face to face meetings. We addressed that by starting a video on demand group.” [Site ID: 324–Sustainer].

Barriers to MRT Sustainment

Four themes emerged with respect to barriers to sustaining MRT groups at a facility: (1) lack of referrals, (2) conflicts with in-person attendance, (3) low patient engagement, and (4) insufficient staffing. These themes are described in detail below. Illustrative quotes for each theme are provided below and in Table 3.

Table 3.

Barriers to MRT sustainment

| Theme | Sample quotation |

|---|---|

| Lack of referrals |

[VJO] wanted to collaborate with us in the substance abuse treatment program to offer this service to Veterans. But the VJOs are rarely at the hospital to co-facilitate a group. And so the plan that we had to partner with them fell through. So that was how we had hoped to get referrals to the group…We needed folks who were court involved or had recent history of being involved with the courts. And we didn’t get those referrals. [Site ID: 101–Non-adopter] VJO was heavily encouraged by MRT, but not something that was mandated. We didn’t get too many referrals from them, so I would have to say that the receptiveness was there, but the referrals weren’t. [site ID: 206–adopter] I felt supportive in going to the training, but when I came back and I needed to get clients into the group I was not being supported. I didn’t get one referral. I could implement it if I had support from the residential unit; then there would be enough people. [Site ID: 202–Adopter] |

| Conflicts with in-person attendance |

Some of our Veterans don’t drive, so transportation may have been an issue. [Site ID: 206–Adopter] I think transportation is [a barrier]. I am in a very rural area. I can’t get enough people to do a group. I will be able to get one person in the group, but then they’re going to have to drive two hours to the VA to attend a two hour group and drive home two hours. They’re rural, and they’re poor, and they don’t have vehicles, so it gets really hard. [Site ID: 202–Adopter] I had opened it up to outpatient. The scheduling was difficult. There’s so many groups going on here, so trying to find a group time. Sometimes we’d find Veterans that were appropriate, but had conflicting appointments. [Site ID: 208–Adopter] |

| Low patient engagement |

Those few that we got to get the group going were already kind of motivated individuals. We were trained as if [MRT] was held in jail [and] they had a captive audience that they knew would be there and would have to participate. So trying to change it for an outpatient setting with volunteers was kind of tough…. [Site ID: 208–Adopter] I didn’t have anybody being mandated to be there…When you have that type of external motivation for the person to be there it seems to work better. [A veteran who was referred] never showed back up because there was nothing other than just his own motivation driving him because there was nothing external whatsoever other than just being recommended. [Site ID: 209–Adopter] |

| Insufficient staffing |

It probably would have been better to train somebody who’s actually on the main campus, who has access to the substance abuse clinic, or the clinics where they have readily available Veterans there…the girl that was doing it got moved to a different position. So it just dissipated right there. [Site ID: 201–Adopter] I tried to get our SUD coordinator involved a little bit and that didn’t really work well…there’s really not a lot of help. I realized that it was going to be up to me to do this. Everybody’s stretched pretty thin already. I was trying to get somebody else trained right here, so we could have two of us, and it never happened. [Site ID: 209–Adopter] Our VJO had very limited staff. Two social workers from our VJO were at the training also…they were overwhelmed with work already. They couldn’t really add this on to their plate…they did not have time to co-facilitate the group so the model that we had planned could not be implemented. [Site ID: 101–Non-adopter] |

Lack of Referrals

Sites that did not sustain MRT highlighted an inability to establish a consistent referral stream as a key barrier. For example, Non-adopter sites reported being unable to get enough referrals to start a group. In some cases, sites indicated that VJP specialists at a facility who were tasked with providing referrals to MRT group facilitators had multiple responsibilities and did not provide referrals on a regular basis. Other sites highlighted a lack of stronger partnerships with other VHA treatment services and/or the criminal justice system as limiting opportunities for receiving referrals to the groups.

I felt supportive in going to the training, but when I came back and I needed to get clients into the group I was not being supported. I didn’t get one referral. I could implement it if I had support from the residential unit; then there would be enough people. [Site ID: 202–Adopter].

Conflicts with In-Person Attendance

Another barrier to MRT sustainment pertained to patients’ ability to attend MRT groups in person. A lack of transportation for patients living in the community, particularly those living in rural settings, was highlighted by participants as a barrier to MRT attendance. In addition, some sites highlighted scheduling conflicts due to competing treatment demands for patients (e.g., conflicts with other outpatient groups; work attendance as part of compensated work therapy that precluded attending groups during the day) as a barrier to MRT sustainment.

I had opened it up to outpatient. The scheduling was difficult. There’s so many groups going on here, so trying to find a group time. Sometimes we’d find veterans that were appropriate, but had conflicting appointments. [Site ID: 208–Adopter].

Low Patient Engagement

Sites that struggled to sustain MRT highlighted low patient engagement as a significant factor. Some sites highlighted a lack of internal motivation on the part of the patient to engage with the time-intensive curriculum of MRT (e.g., homework assignments). Similarly, sites highlighted a lack of external pressures for patients to attend, such as a mandate from a treatment court or parole/probation services.

I didn’t have anybody being mandated to be there….When you have that type of external motivation for the person to be there it seems to work better. [Site ID: 209–Adopter].

Insufficient Staffing

Sites that struggled to sustain MRT discussed a lack of sufficient staff at their site who were trained and/or had the time to facilitate MRT groups. For example, several sites indicated that sustainment was not feasible because only one person was trained in MRT. In some cases, the lone staff member who was trained changed positions and the groups ended thereafter. In other cases, sites noted the lack of sufficient staffing at key services at their facility (e.g., behavioral health) to either help with facilitation of the MRT groups or to provide referrals to the groups.

It probably would have been better to train somebody who’s actually on the main campus, who has access to the substance abuse clinic, or the clinics where they have readily available veterans there…the girl that was doing it got moved to a different position. So it just dissipated right there. [Site ID: 201–Adopter].

Discussion

We evaluated the adoption and sustainment of MRT at VHA facilities following a national training initiative in FY16-17. In one respect, the training initiative was successful, given that the majority of VHA facilities that sent providers to be trained in MRT reported adoption of MRT at some point thereafter. Perhaps more notably, the majority of facilities also reported that their MRT group(s) had been sustained up until the time of the survey, nearly half of whom had sustained their group(s) for at least 2 years. Consistent with the stated expectation of the VJP that support for the training include a collaboration across VJP and behavioral health services at each facility, the majority of VHA facilities that adopted MRT reported that the group was implemented into a behavioral health program. However, nearly half of the facilities that adopted MRT also reported that the group was implemented in the facility’s homeless programs and/or a local Veterans Treatment Court. The brief survey limited our ability to discern the specific ways in which these services and settings were involved in implementation of MRT, although the qualitative findings provide some insights. Nonetheless, the survey results indicate that cross-service and cross-system collaborations were common following the training, which may have contributed to the high prevalence of MRT post-training.

In terms of facility characteristics, MRT adoption was associated with having a provider that joined the MRT community-of-practice listserv. This listserv was organized and managed by VJP leadership to disseminate information to individuals involved in the implementation of MRT in VHA and to provide a forum for these individuals to seek guidance regarding the planning, implementation, and sustainment of MRT groups. For example, VJP leadership would post information such as how to purchase patient workbooks for MRT groups and dates of consultation calls hosted by VJP leadership and representatives from Correctional Counseling Inc., and listserv members would post lessons learned from starting up groups at their local facility. Communities of practice have been promoted in healthcare as a means of enhancing knowledge, promoting standardization of practices, and facilitating innovation and quality of care for patients (Ranmuthugala et al. 2011). Although causality cannot be determined in the present evaluation, the association between engagement in this listserv and adoption of MRT at a facility suggests that this approach may be beneficial to include in an implementation strategy to support the uptake of MRT in a healthcare system.

Among facilities that did adopt MRT post training, those that sustained their group(s) were more likely to report involvement of a Veterans Treatment Court. This finding was echoed in the qualitative data, which suggested that these partnerships facilitated sustainment of MRT groups at a facility by establishing a reliable referral stream and providing a strong external incentive (i.e., mandate) to engage in the intervention (Lamberti 2016). This notwithstanding, concerns have been raised in the criminal justice literature that mandated treatment can be perceived as coercive and lead to poorer outcomes for offenders compared to voluntary treatment (Parhar et al. 2008). Conversely, other research with justice-involved adults has suggested that rates of criminal recidivism (Young et al. 2004) and substance use outcomes (Kelly et al. 2005) are comparable between those who are and are not mandated to treatment. Further, a recent review argued that the risk of perceived coercion can be mitigated through participatory decision-making and attending to clients’ internal motivations (Hachtel et al. 2019). The qualitative data from the current evaluation provide some support for this argument as Sustainer sites tended to have a process of screening referrals to their MRT groups to provide psychoeducation to referred veterans and assess for their internal motivations, which may have helped to minimize any perceived coercion.

In addition to collaborations between VHA and the criminal justice system (Becan et al. 2018), sustainment of MRT groups were also marked by collaborations within VHA facilities. Indeed, participants from Sustainer sites highlighted the importance of buy-in from other VHA services, particularly behavioral health services. Establishing these collaborations was perceived as impacting the ability of a facility to have sufficient staffing to sustain groups and to have a reliable referral stream for the MRT groups. Whether inter- or intra-agency collaborations, successful partnerships between justice program and behavioral health services likely requires discussion of differences in the goals and practices of these services and how to integrate them (Lamberti 2016). For example, behavioral health providers may consider a treatment for recidivism such as MRT as outside their scope of practice. Through didactics, in-services, and other forms of outreach, justice program providers can clarify the potential impact of MRT on outcomes that are more typically the focus of behavioral health providers (e.g., reduced substance use; better interpersonal relationships), thereby generating buy-in and building a coalition of implementation partners in the facility (Powell et al. 2015).

As is often required with interventions that are implemented in contexts outside of where they were their originally designed, sustaining MRT in a healthcare system will likely require adaptations that are carefully tailored to the non-correctional context (Stirman et al. 2019). Given that MRT was designed for correctional settings with a captive audience that has few barriers to attendance, it is perhaps not surprising that sites that were able to sustain MRT tended to make adaptations to both the content and/or delivery of MRT to increase access and engagement. As MRT becomes implemented more widely in non-correctional settings, understanding what adaptations are beneficial and can guide healthcare providers on when and how to modify MRT is a critical area for future research. Such efforts will help establish when adaptations are fidelity-inconsistent and can adversely impact the core elements of the intervention. For example, video telehealth can greatly increase access to MRT to justice-involved adults who are not able to attend in-person groups—an issue that is all the more salient in the era of COVID-19 (Heyworth et al. 2020). However, it is not clear if this format for delivery of the intervention adversely impacts the social processes that are inherent in many group-based interventions (Gerhart et al. 2015) and whether this would limit the potential effectiveness of MRT.

Limitations and Future Directions

Several limitations should be noted. First, most participants were trained in MRT in 2016 or 2017 but were not surveyed or interviewed until 2019; therefore the accuracy of the data may be limited due to retrospective recall biases. Second, no data were systematically collected to assess the impact of adoption and sustainment of MRT on either criminal recidivism or other health-related outcomes at the patient or facility level. This limitation is underscored by the lack of randomized controlled trials of MRT in general; thus, additional outcome data are sorely needed. In particular, the evidence of MRT’s effectiveness among individuals with mental illness is lacking, which is a notable gap given the high prevalence of mental illness among justice-involved veterans (Blodgett et al. 2015). The pending results from a multisite, Hybrid I trial of MRT in VHA will help to address this gap in the literature (Blonigen et al. 2018b). Third, despite the high response rate to the email survey, the data collected were limited in scope. Further, the numbers of qualitative interviews for participants at Non-adopter and Adopter sites were modest. Future evaluations should endeavor to collect more detailed descriptions of MRT groups and interview a wider range of participants and sites to increase the generalizability of the findings. Fourth, this initiative did not involve a formal implementation platform such as Getting to Outcomes (Chinman et al. 2017) or Facilitation (Ritchie et al. 2017), which are designed to systematically implement an evidence-based practice into large healthcare systems. Finally, although it was a national evaluation, the findings may not generalize beyond the VHA, which has a well-established outreach and linkage program (i.e., VJP) that other healthcare systems may not have.

Summary and Conclusions

MRT sustainment was facilitated by intra- and inter-agency collaborations; these collaborations likely facilitated both the referral and engagement of patients into MRT groups as well as adequate staffing to initiate and maintain the groups. Adaptations to the content and delivery of MRT are likely critical to facilitate the uptake and maintenance of MRT in non-correctional settings, as are efforts to screen referrals to minimize the perception of coercion among referred patients. Collectively, the findings provide guidance to healthcare systems that are seeking to implement MRT as well as help develop an implementation strategy, grounded in the building of coalitions and promoting adaptability (Powell et al. 2015), that can be formally tested in future implementation trials (Landes et al. 2019).

Funding

This work was supported by supplemental funding from the VA Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (Grant No. QUE 15-284). Christine Timko was supported by a Senior Research Career Scientist Award from VA HSR&D (Grant No. RCS-00-001). Joel Rosenthal is now retired from the Veterans Health Administration. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Veterans Health Administration.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures were reviewed by the local Institutional Review Board, which determined that the study did not meet criteria for human subjects research and was exempt from further review.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Aarons GA, Hurlburt M, Horowitz SM. Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implemenation in public service sectors. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2011;38:4–23. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0327-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Salam S, Kilmer A, Visher CA. Building bridges in New Jersey: Strengthening interagency collaboration for offenders receiving drug treatment. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. 2015;61(2):210–228. doi: 10.1177/0306624x15598959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews DA, Bonta JL. Rehabilitating criminal justice policy and practice. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law. 2010;16:39–55. doi: 10.1037/a0018362. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aos S, Miller MG, Drake E. Evidence-based adult corrections programs: What works and what does not. Olympia, WA: Washington State Institute for Public Policy; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Becan JE, Bartkowski JP, Knight DK, Wiley T, DiClemente R, Ducharme L, Welsh WN, Bowser D, McCollister K, Hiller M, Spaulding AC, Flynn PM, Swartzendruber A, Dickson MF, Fisher JH, Aarons GA. A model for rigorously applying the exploration, preparation, implementation, sustainment (EPIS) framework in the design and measurement of a large scale collaborative multi-site study. Health and Justice. 2018;6(1):9. doi: 10.1186/s40352-018-0068-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blodgett JC, Fuh IL, Maisel NC, Midboe AM. A structured evidence review to identify treatments needs of justice-involved veterans and associated psychological interventions. Menlo Park, CA: Center for Health Care Evaluation, VA Palo Alto Health Care System; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Blodgett JC, Avoundjian T, Finlay AK, Rosenthal J, Asch SM, Maisel NC, Midboe AM. Prevalence of mental health disorders among justice-involved veterans. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2015;37(1):163–176. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxu003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blonigen DM, Cucciare MA, Timko C, Smith JS, Harnish A, Kemp L, Rosenthal J, Smelson D. Study protocol: A hybrid effectivenes implementation trial of moral reconation therapy in the US Veterans Health Administration. BMC Health Services Research. 2018;18(1):164. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-2967-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blonigen DM, King CM, Timko C. Criminal justice involvement among veterans. In: Tsai J, Seamone E, editors. Intersections between mental health and law among veterans. Cham: Springer; 2019. pp. 13–43. [Google Scholar]

- Blonigen DM, Macia KS, Smelson D, Timko C. Criminal recidivism among justice-involved veterans following substance use disorder residential treatment. Addictive Behaviors. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blonigen DM, Rodriguez AL, Manfredi L, Nevedal A, Rosenthal J, McGuire JF, Smelson D, Timko C. Cognitive-behavioral treatments for criminogenic thinking: Barriers and facilitators to implementation within the Veterans Health Administration. Psychological Services. 2018;15:87–97. doi: 10.1037/ser0000128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blue-Howells JH, Clark SC, van den Berk-Clark C, McGuire JF. The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs veterans justice programs and the sequential intercept model: Case examples in national dissemination of intervention for justice-involved veterans. Psychological Services. 2013;10:48–53. doi: 10.1037/a0029652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronson J, Carson AC, Noonan M, Berzofsky M. Veterans in prison and jail, 2011–12. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chinman M, McCarthy S, Hannah G, Byrne TH, Smelson DA. Using getting to outcomes to facilitate the use of an evidence-based practice in VA homeless programs: A cluster-randomized trial of an implementation support strategy. Implementation Science. 2017;12(1):34. doi: 10.1186/s13012-017-0565-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark S, Flatley B. VA programs for justice-involved veterans. In: Tsai J, Seamone E, editors. Intersections between mental health and law among veterans. Cham: Springer; 2019. pp. 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science. 2009;4:50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Veterans Affairs . Medical benefits package (38 CFR § 17.38) DC: Veterans Justice Program Washington; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Veterans Affairs . HOMES: Veterans justice outreach and health care for re-entry veterans summary data. Washington, DC: Veterans Justice Program; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Veterans Affairs (2016). Retrieved from https://www.va.gov/myva/. Accessed 1 Feb 2020.

- Department of Veterans Affairs (2020). Veterans treatment courts and other Veteran-focused courts served by VA Veterans Justice Outreach Specialists (fact sheet, July 2020). Retrieved from http://www.va.gov/homeless/vjo.asp. Accessed on 1 Dec 2020

- Durose MR, Cooper AD, Snyder HN. Recidivism of prisoners released in 30 states in 2005: Patterns from 2005 to 2010. Washington, DC: U.S Department of Justice, Office of Justice Program, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson LM, Wormith JS. A meta-analysis of moral reconation therapy. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. 2013;57:1076–1106. doi: 10.1177/0306624X12447771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2013;13:117. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhart J, Holman K, Seymour B, Dinges B, Ronan GF. Group process as a mechanism of change in the group treatment of anger and aggression. International Journal Group Psychotherapy. 2015;65(2):180–208. doi: 10.1521/ijgp.2015.65.2.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green AE, Trott E, Willging CE, Finn NK, Ehrhart MG, Aarons GA. The role of collaborations in sustaining an evidence-based intervention to reduce child neglect. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2015;53:4–16. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hachtel H, Vogel T, Huber CG. Mandated treatment and its impact on therapeutic process and outcome factors. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2019;10:219. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley RD, Baldwin JM. Waging war on recidivism among justice-involved veterans: An impact evaluation of a large urban veterans treatment court. Criminal Justice Policy Review. 2019;30:52–78. doi: 10.1177/0887403416650490. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hennink MM, Kaiser BN, Marconi VC. Code saturation versus meaning saturation: How many interviews are enough? Qualitative Health Research. 2017;27:591–608. doi: 10.1177/1049732316665344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyworth S, Kirsh S, Zulman D, Ferguson JM, Kizer KW. Expanding access through virtual care: The VA’s early experience with Covid-19. NEJM Catalyst. 2020 doi: 10.1056/cat.20.0327. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaeble D, Glaze L. Correctional populations in the United States, 2015. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Finney JW, Moos R. Substance use disorder patients who are mandated to treatment: Characteristics, treatment process, and 1- and 5-year outcomes. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;28:213–223. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamberti JS. Preventing criminal recidivism through mental health and criminal justice collaboration. Psychiatric Services. 2016;67(11):1206–1212. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201500384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landenberger NA, Lipsey MW. The positive effects of cognitive behavioral programs for offenders: A meta-analysis of factors associated with effective treatment. Journal of Experimental Criminology. 2005;1:451–476. doi: 10.1007/s11292-005-3541-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Landes SJ, McBain SA, Curran GM. An introduction to effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs. Psychiatry Research. 2019;280:112513. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little GL, Robinson KD. Moral reconation therapy: A systematic step-by-step treatment system for treatment resistant clients. Psychological Reports. 1988;62:135–151. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1988.62.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little GL, Robinson KD. Winning the invisible war: An MRT workbook for veterans. Memphis, TN: Eagle Wing Books; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- McCall JD, Pomerance B. Veterans treatment courts. In: Tsai J, Seamone E, editors. Intersections between mental health and law among veterans. Cham: Springer; 2019. pp. 89–110. [Google Scholar]

- Milkman, H., & Wanberg, K. (2007). Cognitive behavioral treatment: A review and discussion for corrections professionals. Retrieved from https://s3.amazonaws.com/static.nicic.gov/Library/021657.pdf. Accessed 1 Feb 2020.

- Moullin JC, Dickson KS, Stadnick NA, Rabin B, Aarons GA. Systematic review of the exploration, preparation, implementaiton, sustainment (EPIS) framework. Implementation Science. 2019;14:1. doi: 10.1186/s13012-018-0842-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moullin JC, Sklar M, Green A, Dickson KS, Stadnick NA, Reeder K, Aarons GA. Advancing the pragmatic measurement of sustainment: A narrative review of measures. Implementation Science Communications. 2020;1:76. doi: 10.1186/s43058-020-00068-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal JW, Neal ZP, VanDyke E, Kornbluh M. Expedting the analysis of qualitaive data in evaluation: A procedure for the rapid identification of themes from audio recordings (RITA) American Journal of Evaluation. 2015;36(1):118–132. doi: 10.1177/1098214014536601. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palinkas LA, Aarons GA, Horwitz SM, Chamberlain P, Hurlburt M, Landsverk J. Mixed method designs in implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2011;38:44–53. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0314-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parhar KK, Wormith JS, Derkzen DM, Beauregard AM. Offender coercion in treatment: A meta-analysis of effectiveness. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2008;35(9):1109–1135. doi: 10.1177/0093854808320169. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson M, Brand SL, Quinn C, Shaw J, Maguire M, Michie S, Briscoe S, Lennox C, Stirzaker A, Kirkpatrick T, Byng T. Using realist review to inform intervention development: Methodological illustration and conceptual platform for collaborative care in offender mental health. Implementation Science. 2015;10:134. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0321-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, Damschroeder LJ, Smith JL, Matthieu MM, Proctor EK, Kirchner JE. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: Results from the expert recommendations for implementing change (ERIC) project. Implementation Science. 2015;10:21. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prendergast M, Welsh WN, Stein L, Lehman W, Melnick G, Warda U, Shafer M, Ulaszek W, Rodis E, Abdel-Salam S, Duvall J. Influence of organizational characteristics on success in implementing process improvement goals in correctional treatment settings. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research. 2017;44(4):625–646. doi: 10.1007/s11414-016-9531-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranmuthugala G, Plumb JJ, Cunningham FC, Georgiou A, Westbrook JI, Braithwaite J. How and why are communities of practice established in the healthcare sector? A systematic review of the literature. BMC Health Services Research. 2011;11:273. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie MJ, Parker LE, Edlund CN, Kirchner JE. Using implementation facilitation to foster clinical practice quality and adherence to evidence in challenged settings: A qualitative study. BMC Health Services Research. 2017;17(1):294. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2217-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott DA, McGilloway S, Dempster M, Browne F, Donnelly M. Effectiveness of criminal justice liaison and diversion services for offenders with mental disorders: A review. Psychiatric Services. 2013;64(9):843–849. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stirman S, Baumann AA, Miller CJ. The FRAME: An expanded framework for reporting adaptations and modifications to evidence-based interventions. Implementation Science. 2019;14(1):58. doi: 10.1186/s13012-019-0898-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai J, Finlay A, Flatley B, Kasprow WJ, Clark S. A national study of veterans treatment court participants: Who benefits and who recidivates. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2018;45:236–244. doi: 10.1007/S10488-017-0816-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USDA Economic Research Service (2020). Rural-urban commuting area codes. Ag Data Commons. Retrieved from https://data.nal.usda.gov/dataset/rural-urban-commuting-area-codes

- Young D, Fluellen R, Belenko S. Criminal recidivism in three models of mandatory drug treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2004;27:313–323. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]