Cyanobacteria are important organisms for the ecosystem, considering their contribution to carbon fixation and oxygen production, while at the same time some species produce compounds that are toxic to their environment. As a consequence, cyanobacterial overpopulation might negatively impact the diversity of natural communities.

KEYWORDS: cyanobacteria, protein secretion, two-partner secretion, TpsA, TpsB, antibiotic resistance

ABSTRACT

The outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria acts as an initial diffusion barrier that shields the cell from the environment. It contains many membrane-embedded proteins required for functionality of this system. These proteins serve as solute and lipid transporters or as machines for membrane insertion or secretion of proteins. The genome of Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 codes for two outer membrane transporters termed TpsB1 and TpsB2. They belong to the family of the two-partner secretion system proteins which are characteristic of pathogenic bacteria. Because pathogenicity of Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 has not been reported, the function of these two cyanobacterial TpsB proteins was analyzed. TpsB1 is encoded by alr1659, while TpsB2 is encoded by all5116. The latter is part of a genomic region containing 11 genes encoding TpsA-like proteins. However, tpsB2 is transcribed independently of a tpsA gene cluster. Bioinformatics analysis revealed the presence of at least 22 genes in Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 putatively coding for substrates of the TpsB system, suggesting a rather global function of the two TpsB proteins. Insertion of a plasmid into each of the two genes resulted in altered outer membrane integrity and antibiotic resistance. In addition, the expression of genes coding for the Clp and Deg proteases is dysregulated in these mutants. Moreover, for two of the putative substrates, a dependence of the secretion on functional TpsB proteins could be confirmed. We confirm the existence of a two-partner secretion system in Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 and predict a large pool of putative substrates.

IMPORTANCE Cyanobacteria are important organisms for the ecosystem, considering their contribution to carbon fixation and oxygen production, while at the same time some species produce compounds that are toxic to their environment. As a consequence, cyanobacterial overpopulation might negatively impact the diversity of natural communities. Thus, a detailed understanding of cyanobacterial interaction with the environment, including other organisms, is required to define their impact on ecosystems. While two-partner secretion systems in pathogenic bacteria are well known, we provide a first description of the cyanobacterial two-partner secretion system.

INTRODUCTION

Cyanobacteria are Gram-negative organisms that are characterized by a cell envelope composed of an inner membrane, a peptidoglycan layer, an outer membrane, and an exterior layer (1, 2). One of the functions of the bacterial cell wall is to maintain the cell shape and to prevent bursting from osmotic pressure. Nevertheless, like every living system, cyanobacteria depend on an efficient interaction with the environment, which includes the exchange of nutrients, communication with other species, and selection of growth environments (3–6). This requires macromolecular complexes in the inner membrane and cell wall. Much attention has been given to developing an understanding of the cyanobacterial inner membrane proteome, comprising components involved in transport of metals (2, 7), organic molecules (8), or proteins (2, 9). In contrast, the understanding of transporters in the outer membrane is just emerging. In general, the outer membrane proteome of Gram-negative bacteria can be dissected into proteins involved in structural integrity, outer membrane or cell wall assembly, nutrient exchange, or protein transport (1).

The porin outer membrane protein family is involved in structural stabilization of the cell wall system and in the transport of solutes. Porin-like proteins were predicted in cyanobacterial genomes (10), but their function has to be experimentally confirmed. Moreover, it is currently argued that the unicellular freshwater cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 “lacks putative porins” with classical function in organic solute transport (11).

The outer membrane proteins of the LptD and Omp85 family are involved in the assembly of lipids, e.g., the lipopolysaccharide layer (LPS) (12–16), and proteins (17–19) into the outer membrane, respectively. Both are encoded by genes that belong to the core genome of cyanobacteria (14) and are essential for cell survival (15, 16, 18–20). Cyanobacterial Omp85 proteins are homologues of the pore-forming protein of the chloroplast translocon (18, 19). Notably, the genomes of some species, like Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 (referred to here as Anabaena sp.), encode multiple forms of Omp85 (20).

A large family of outer membrane proteins consists of components of different secretion systems. With respect to cyanobacteria, outer membrane proteins of the type I (TolC, annotated as HgdD in Anabaena sp.) (21–24) and of the type IV pilus systems were described previously (3, 25). In addition, cyanobacterial proteins of the large type V secretion system family were identified by bioinformatics methods (10) but are not yet functionally characterized.

The outer membrane proteins of the type V secretion systems, also assigned to the category “autotransporters” (26), are divided into six subgroups (27). Proteins of type Va consist of a 12-stranded β-barrel membrane domain and an N-terminal passenger domain which is exported to the extracellular environment. Type Ve proteins are similar to type Va proteins but with inverted topology, as they contain a C-terminal passenger domain. Proteins of the type Vc system form a trimer in the outer membrane. After assembly, the topology becomes comparable to that of type Va proteins. In contrast to the other autotransporters, type Vf proteins have a surface-exposed passenger domain that is part of a loop between two β-strands.

Type Vb and type Vd proteins consist of a 16-stranded β-barrel with similarity to the proteins of the Omp85 family (28, 29). An additional similarity to the Omp85 family is supported by conserved elements between the two protein families (30). In addition, the proteins of type Vb contain two N-terminal polypeptide transport-associated (POTRA) domains (31) in addition to the membrane-embedded barrel region, while type Vd proteins contain only one POTRA domain. Whereas the type Vd proteins contain an N-terminal passenger domain, the passenger protein and the translocation pore of type Vb transport systems comprise two individual proteins. Consequently, the type Vb secretion system is annotated as a two-partner secretion system (Tps), with TpsA representing the substrate or passenger and TpsB the outer membrane-embedded protein (27, 32).

In proteobacteria, the genes for the transporter of the two-partner secretion system and corresponding substrates are often found to be organized in an operon, though exceptions have been reported (33). TpsA proteins contain an N-terminal conserved domain required for recognition by TpsB (34). In the periplasm, TpsA proteins are associated with proteins of the DegP family (35) and are processed by periplasmic and extracellular proteases (36). It has been proposed that TpsA proteins are involved in interbacterial competition and cooperation or in modification of host membranes (37). Thus, it is of interest to clarify the function of the two-partner secretion systems in cyanobacteria.

Here, the bioinformatics analysis of protein sequences with similarity to the membrane-embedded autotransporter (type V family) is revisited. Based on the identification of sequences of the type Vb family, we addressed the functionality of the two TpsB-like proteins in Anabaena sp. In contrast to proteobacteria, the genes coding for substrates of the TpsB proteins are not exclusively organized in an operon. We confirmed the function of the TpsB proteins in protein secretion for two representative substrates and found that mutants show an accumulation of transcripts of components of the DegP system. Also consistent with a function as an autotransporter, mutations of the two genes coding for the TpsB proteins result in a phenotype related to altered outer membrane biogenesis and antibiotic resistance.

RESULTS

Type V secretion systems in cyanobacteria.

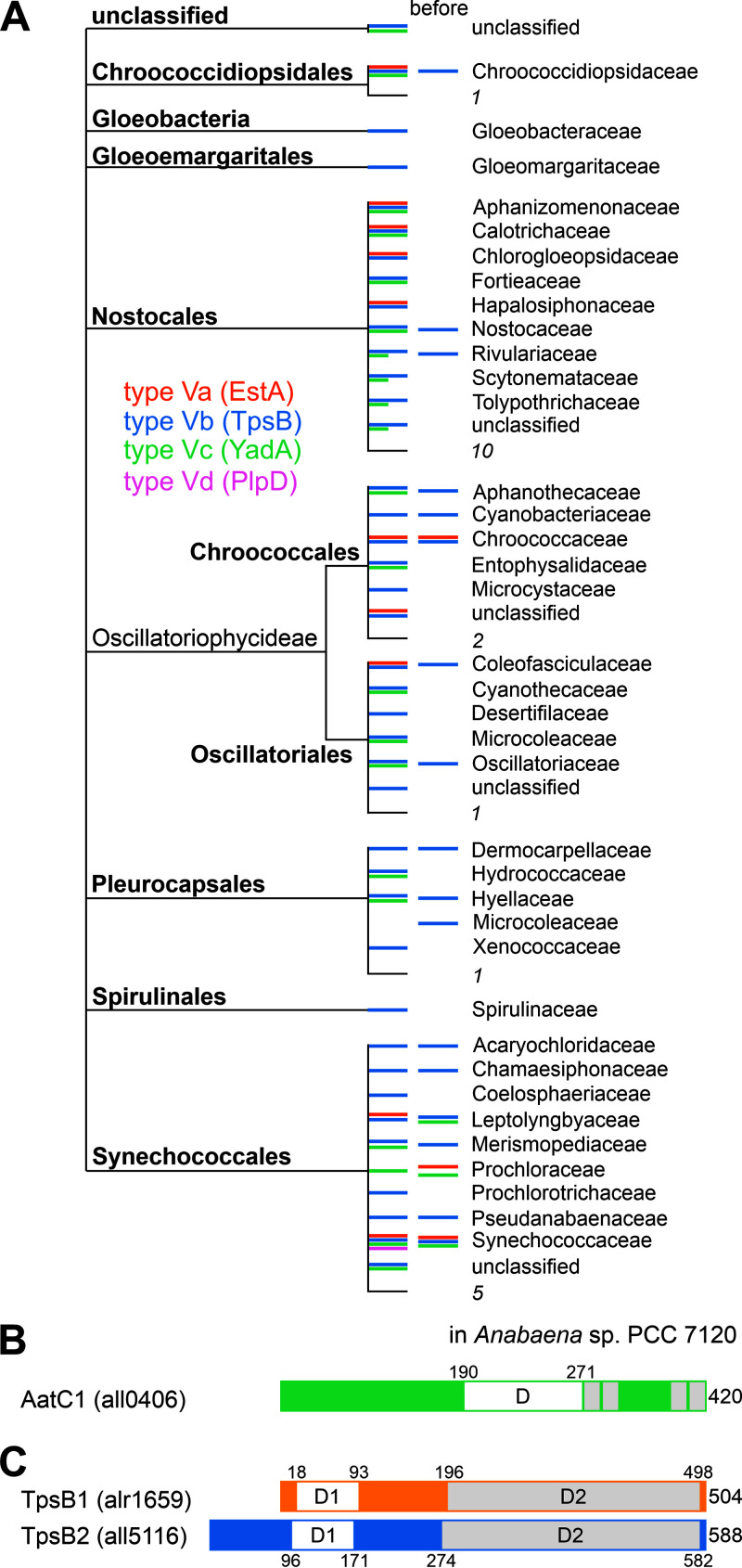

To complement previous studies (10, 38), a systematic analysis of the presence of type V-like sequences in cyanobacterial genomes was performed. Baits representing the six type V subgroups were selected and used to identify cyanobacterial genes coding for corresponding family members. Cyanobacterial sequences with similarity to type Va proteins were identified utilizing the sequence of EstA (Pseudomonas aeruginosa) but not with the sequence of IgA (Neisseria meningitides) as bait. In total, 41 cyanobacterial sequences (see File S1 in the supplemental material) were identified, representing 13 protein groups with 90% identity (File S2). Using the cyanobacterial sequences for a BLAST search of cyanobacterial genomes did not yield additional sequences. Cyanobacterial type Va-like sequences have been detected in five of the nine cyanobacterial orders (based on NCBI taxonomy [39]), while the previous analysis proposed the existence of such sequences in two cyanobacterial orders (Fig. 1A) (38). Nevertheless, the type Va-like sequences were not found in all families of each order (Fig. 1A; Fig. S1). For example, a sequence with similarity to type Va proteins was not found in Nostocaceae, and thus, a type Va secretion system appears not to be present in Anabaena sp.

FIG 1.

Type V secretion proteins in cyanobacteria. (A) The cyanobacterial order and the family (based on NCBI nomenclature [39]) in which a protein sequence with similarity to the type Va (orange), type Vb (blue), type Vc (green), or type Vd (purple) was identified is shown to provide an overview of the occurrence of sequences. The families in which a sequence was detected in the previous study (38) are indicated (“before”). Numbers are numbers of families in which type Va-, Vb-, Vc-, or Vd-like proteins were identified. (B) Domain structure of the Anabaena sp. autotransporter of the type Vc family 1 (AatC1). D, cl17507 (LbR-like superfamily)/cd12813 (LbR-like trimer) interface; gray boxes, β-strands. (C) Domain structure of the two TpsB proteins in Anabaena sp. D1, PF08479 (polypeptide transport-associated [POTRA] domain), ShlB type; D2, PF01103 (Bac_surface_Ag [barrel domain]).

By a similar approach, 50 cyanobacterial sequences with similarity to the type Vc protein family represented by YadA (Yersinia enterocolitica) were identified, but with low E values (File S3) and a high sequence divergence of the C-terminal membrane anchor domain. Further, some of the sequences found in Synechococcus species are remarkably longer than the bait, while sequences of the expected length were observed as well (File S3). The proteins with such extended sequences were previously assigned to the category “YadA-like family protein” (e.g., WP_170953694.1, a protein with 4,803 annotated amino acids), but their function as type Vc autotransporters has to be experimentally confirmed. Here, sequences longer than 1,000 amino acids (twice the size of the bait protein) were omitted from the subsequent analysis as long as another sequence was identified in the same genus. Additional cyanobacterial sequences were identified using the initially identified sequences as bait. After analysis of the presence of the two domains in the identified sequences by manual inspection of the alignment, 51 groups according to CD-HIT were identified (Fig. 1A; Fig. S1; File S4). For sequences of 20 groups, the membrane anchor domain could not be identified by our alignment strategy, while the N-terminal domain featured good similarity (Fig. 1A; Fig. S1; File S5). Altogether, the previous study proposed the existence of type Vc autotransporter to be restricted to Synechococcales (38), while in our approach, sequences in seven cyanobacterial orders were identified.

The previously annotated autotransporter encoded by all0406 in Anabaena sp. (10) was identified as well. In contrast, a protein with similarity to type Vc transporter was not identified in the unicellular cyanobacterial model strain Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. The protein encoded by all0406 was annotated as an Anabaena sp. autotransporter of the type Vc family number 1 (AatC1). For AatC1, a signal peptide could not be identified by prediction (40), while a left-handed beta-roll domain is found in the protein sequence between amino acids 190 and 271 (Fig. 1B), which is characteristic of YadA. The C-terminal domain shares low similarity with YadA, though four β-strands were predicted in this region (amino acids [aa] 272 to 280, 304 to 312, 404 to 411, and 413 to 420) (Fig. 1B).

Type Vd family cyanobacterial proteins with similarity to FplA (Fusobacterium nucleatum) were not found, while when PlpD (P. aeruginosa) was used as the query, one cyanobacterial gene coding for both passenger and membrane-embedded domains was identified in the Synechococcaceae cyanobacterium SM1_2_3 (NJM12355.1) (Fig. 1A; Fig. S2). Remarkably, sequences with similarity to the encoded protein could not be identified in other cyanobacterial species, while a high similarity to sequences encoded by proteobacteria, especially gammaproteobacteria, was found. Hence, the annotated gene is a result of either contamination or a recent horizontal gene transfer.

It has been proposed that in Anabaena sp., two genes (alr1659 and all5116) code for proteins with similarity to the type Vb protein family (10). The two TpsB-like proteins are termed Anabaena two-partner secretion proteins B1 and B2 (anaTpsB1 and anaTpsB2). For better readability, the abbreviations TpsB1 and TpsB2 are used here. When the two protein sequences were used as bait, many cyanobacterial sequences could be identified which are clearly distinct from the sequences found when Omp85 protein sequences were used as bait (not shown). Selecting all sequences identified with an E value of <10−70 for either one of the sequences from Anabaena sp. and filtering for 90% sequence identity by CD-HIT yielded more than 1,000 protein groups (File S6). They represent sequences of all cyanobacterial orders and more than 60% of all assigned cyanobacterial families (Fig. 1A; Fig. S3). In Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803, the type Vb like protein is encoded by slr1661, which is distinct from the Omp85 homologue encoded by slr1227.

Thus, based on our analysis, it can be concluded that type Va, type Vb, and type Vc secretion systems exist in cyanobacteria as previously proposed (38). The type Va and type Vc systems were not found in all cyanobacterial orders. Further, homologs were not present in all families of the orders where protein sequences were identified. Sequences with similarity to the type Vb secretion proteins are found in all cyanobacterial orders, suggesting an ancestral occurrence. In contrast, cyanobacterial genes coding for proteins with similarity to the membrane anchor and the passenger domain of type Ve (using intimin from Escherichia coli as the query) could not be identified. The same holds true for type Vf proteins using BapA (Achromobacter ruhlandii). Type Vd, if it is present at all, is limited to a small set of species (Fig. 1A) (38).

TpsB proteins in Anabaena.

The proteins TpsB1 and TpsB2 are characterized by a ShlB-type POTRA domain (Fig. 1C, D1 region) and a barrel-forming region (Fig. 1C, D2 region). In addition, a signal peptide was predicted for TpsB2 comprising amino acids 1 to 40, whereas within TpsB1, a signal could not be predicted. Both tpsB1 and tpsB2 are expressed under standard growth conditions and upon nitrogen starvation, as judged from the occurrence of a PCR product (Fig. S4). This is consistent with previously obtained analyses of the global transcriptome (41).

The genomic region containing tpsB2 codes for 11 type Vb substrates.

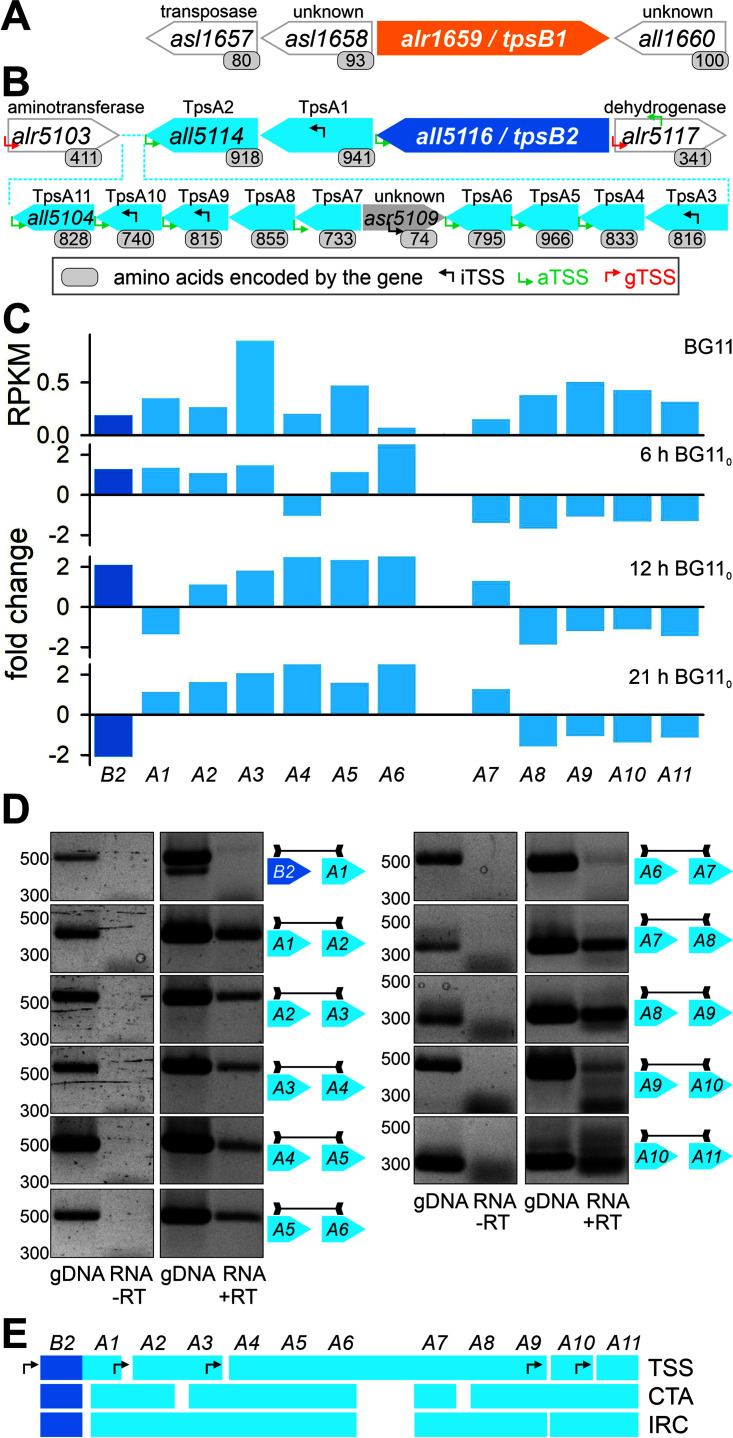

While tpsB1 is transcribed monocistronically (Fig. 2A), tpsB2 is part of a large genomic cluster. The genomic region with tpsB2 contains 11 genes coding for proteins with a TpsA signature (annotated as anaTpsA1 to anaTpsA11 and referred to here as TpsA1 to TpsA11) (Fig. 2B). The cluster also contains a gene oriented in the opposite direction (asr5109, coding for a peptide of unknown function).

FIG 2.

Genomic regions with tpsB genes in Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. (A) The genomic region encoding TpsB1 (orange) is shown. White arrows with gray frames indicate genes encoded in the opposite direction compared to tpsB1; the function of the encoded protein is given on top. (B) The genomic region with tpsB2 (dark blue). Gray frames indicate genes defining the border of the genomic region. The putative function of the encoded protein is indicated (Alr5103 is ll-diaminopimelate aminotransferase; All5115-All5110 and All5108-All5104 are large exoproteins involved in heme utilization or adhesion [TpsA]; Alr5117 is l-iditol 2-dehydrogenase), and the numbers below the arrows indicate the number of encoded amino acids. The small arrows indicate gene intrinsic transcriptional start sites (iTSS; black), transcriptional start sites in the 200 nt upstream of the gene (gTSS; red), or transcriptional start sites with inverse orientation to the annotated genes (aTSS; green) (42). (C) Reads per kilobase per million (RPKM) values for the transcript abundance in Anabaena sp. grown in BG11 as well as the fold change in transcript abundance 6 h, 12 h, and 21 h after transfer to BG110 for tpsB2 and tpsA1-tpsA11 were taken from reference 41. (D) Genomic DNA (gDNA) or RNA was isolated from Anabaena sp. cDNA was generated from RNA in the presence of the reverse transcriptase (+RT). PCR with oligonucleotides amplifying the intergenic region as indicated on the gene models was performed on gDNA, RNA (RNA −RT), or cDNA (RNA +RT). The intergenic region amplified is highlighted on the right of each panel; for better readability, “tps” has been omitted. (E) The organization of the transcriptional units deduced from obtained transcriptional start sites (B; TSS), from correlation of transcript abundance under different conditions (C; CTA) or amplification of intergenic regions from cDNA (IRC).

Previous analyses predicted intragenic transcriptional start sites (iTSS) in alr5117, tpsA1, tpsA3, tpsA9, and tpsA10 (42). Assuming that these are start sites for transcripts of the downstream gene, five transcriptional units might exist (tpsB2/tpsA1, tpsA2/tpsA3, tpsA4 to tpsA9, tpsA10, and tpsA11) (Fig. 2B). The correlation of transcript abundance (CTA) under different conditions is also used as an indication for transcriptional units. Based on analysis of the accessible data for nitrogen starvation of Anabaena sp. (41), the transcript abundance profile and its regulation in response to the stress application might suggest the existence of up to five independent units as well (Fig. 2C) (tpsB2, tpsA1/tpsA2, tpsA3 to tpsA6, tpsA7, and tpsA9 to tpsA11). However, the transcriptional units assigned according to the transcript profile contradict the units defined by the observed transcriptional start sites.

To explore this further, the composition of transcriptional units was analyzed by PCR on genomic DNA (gDNA; control) and cDNA generated in the absence (−RT; control) or presence (+RT) of reverse transcriptase to probe for the presence of intergenic regions in the cDNA (intergenic region from cDNA [IRC]). Each pair of oligonucleotides produced a product of the expected size when gDNA was used as the template, whereas in the −RT controls, no fragments were detected (Fig. 2D). In the cDNA sample (+RT) a product for all intergenic regions except those between tpsB1/tpsA1 and tpsA6/tpsA7 was obtained (Fig. 2D). However, the PCR product for the intergenic region between tpsA9 and tpsA10 was of low abundance compared to the product obtained using the gDNA template (Fig. 2D). Based on these analyses, the presence of at least four transcriptional units is likely, namely, tpsB2, tpsA1-tpsA6, tpsA7-tpsA9, and tpsA10-tpsA11 (Fig. 2E). The independent transcription of tpsB2 is consistent with the expression profile, while the last unit (tpsA10-tpsA11) is supported by the identified transcriptional start site in tpsA9.

The individual TpsB-like proteins are not essential for growth of Anabaena sp.

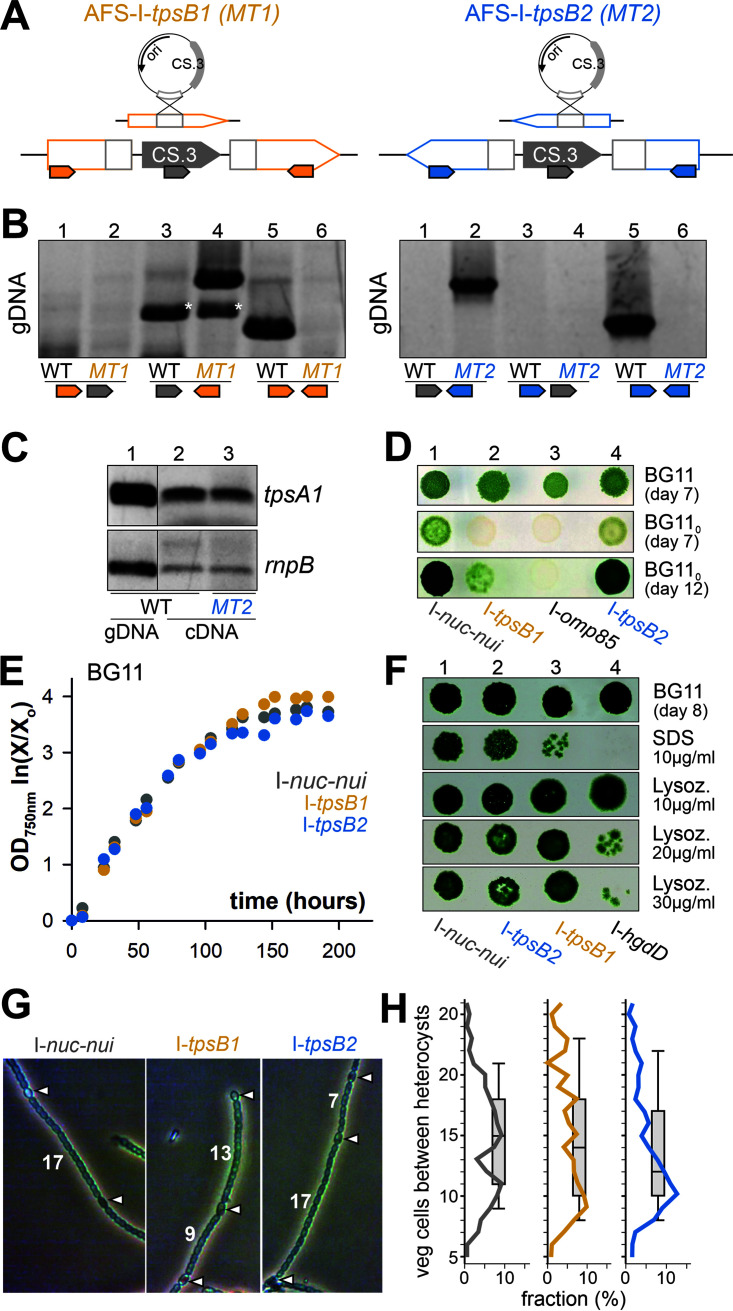

Loss-of-function mutants of the two genes were generated by plasmid insertion. A fragment of either tpsB1 or tpsB2 was cloned into pCSV3 (43). The resulting plasmids were used for conjugation of wild-type Anabaena sp. to achieve plasmid insertion into the genome by single recombination (Fig. 3A). The generated mutants were annotated as Anabaena sp. mutant created in Frankfurt by the Schleiff group by plasmid insertion into the genomic region with the indicated gene (AFS-I-[gene]) (44).

FIG 3.

Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 mutants of tpsB1 and tpsB2. (A) Diagram of the generation of the mutants. (Top) Strategy of the single recombination yielding plasmid insertion into the genome; (bottom) genotype of the mutant. The positioning and directionality of oligonucleotides used for segregation analysis are indicated by small arrows. (B) Confirmation of the segregation of the generated plasmid insertion strains AFS-I-tpsB1 (MT1) and AFS-I-tpsB2 (MT2) by PCR on genomic DNA isolated from wild-type (WT) or mutant strains utilizing oligonucleotides, as indicated on the model of the genomic region. Stars indicate unspecific products of the primer pairs. (C) PCR on gDNA isolated from the wild type (WT) or cDNA generated from RNA isolated from the wild type (WT) or AFS-I-tpsB2 (MT2) with gene-specific oligonucleotides. (D) Anabaena sp. strains AFS-I-nuc-nui, AFS-I-tpsB1, AFS-I-omp85, and AFS-I-tpsB2 were spotted (5 μl at an OD750 of 1) onto BG11 (top) or BG110 (middle and bottom) plates, and growth was monitored for the indicated times. (E) Anabaena sp. strains AFS-I-nuc-nui (gray), AFS-I-tpsB1 (orange), and AFS-I-tpsB1 (blue) were incubated in liquid BG11, and the OD750 was monitored at the indicated times. A representative result is shown. (F) Anabaena sp. strains AFS-I-nuc-nui, AFS-I-tpsB2, AFS-I-tpsB1, and AFS-I-hgdD were spotted (5 μl at an OD750 of 1) onto BG11 plates containing the indicated compounds, and growth was monitored after 8 days. (G) Representative images of filaments of the indicated strains highlighting the heterocysts (arrowheads) and showing the numbers of vegetative cells between them. (H) The number of vegetative cells between two heterocysts was counted (wild type, 171; AFS-I-tpsB1, 127; AFS-I-tpsB2, 138) in >60 randomly selected filaments. The percentage of a defined distance with respect to all counted distances is shown as a line, and the distribution is shown as box plot with a horizontal line at the median.

AFS-I-tpsB1 and AFS-I-tpsB2 were segregated, since PCR of isolated genomic DNA did not yield a product for the endogenous gene (Fig. 3B, lanes 6), while the insertion of the plasmid could be confirmed (lanes 4 and 2). Consistent with the analysis of the transcriptional unit, expression of tpsA1 in AFS-I-tpsB2 was observed at a level comparable to the expression level in the wild type (Fig. 3C, lane 3 versus 2). Thus, the mutants were used to analyze the functions of these two genes. For comparison, a control strain was generated by cloning a fragment of the neutral nucA-nuiA region of the α megaplasmid of Anabaena sp. into pCSV3, resulting in the published plasmid pCSEL24 (45), followed by conjugation of the wild type to obtain single recombined fully segregated mutants (AFS-I-nuc-nui). This mutant served as a control, as it has the same antibiotic resistance as the other mutants, while it does not show a phenotype (46).

The growth of the two mutants on BG11 plates (Fig. 3D, lanes 2 and 4) was indistinguishable from that of AFS-I-nuc-nui (lane 1). The same held true for growth of the strains in suspension (Fig. 3E). Only AFS-I-omp85 bearing a plasmid insertion in alr2269 did not grow as fast as the other three strains (Fig. 3D, lane 3), which is consistent with the previously reported phenotype (20). In contrast, the growth the hgdD mutant (AFS-I-hgdD) (22, 47, 48) was comparable to that of the other three strains (Fig. 3F, top panel).

As tpsB1 and tpsB2 are induced under diazotrophic conditions (Fig. S4) (41), the growth of the respective mutants on BG110 (i.e., BG11 without a combined nitrogen source) was analyzed. After 7 days, AFS-I-tpsB2, but not AFS-I-tpsB1, had grown on BG110 plates, although not to the same extent as AFS-I-nuc-nui (Fig. 3D, middle). AFS-I-tpsB2 had fully and AFS-I-tpsB1 had partially recovered after 12 days of growth on BG110 plates compared to AFS-I-nuc-nui (lower panel). Hence, both mutants showed a growth delay phenotype in BG110, which is more pronounced for AFS-I-tpsB1. Analysis of the heterocyst morphology did not reveal a difference between AFS-I-nuc-nui and the two mutants (Fig. 3G). Analysis of the number of vegetative cells between two heterocysts in AFS-I-nuc-nui yielded two peaks. The first peak represents about 9 to 11 vegetative cells and the second peak about 15 to 18 vegetative cells (Fig. 3H, left). The median of the distribution is 15 cells. For AFS-I-tpsB1, the first peak was observed as well (8 to 10 cells), while the second peak is rather broad, 12 to 20 cells (Fig. 3H, middle). The median of the distribution is 14 cells. For AFS-I-tpsB2, the first peak (9 to 11 cells) dominated the distribution, yielding an overall median of 12 cells (Fig. 3H, right). Hence, a variation of the distances between heterocysts was observed in the mutants, but the median is not significantly different and the strains do not show a fox− phenotype (“incapable of fixation in the presence of oxygen” [49]), as observed for AFS-I-omp85 (Fig. 3D, bottom) (20).

The delayed growth on BG110 plates might suggest that the disruption of tpsB1 and tpsB2 results in an altered outer membrane integrity, as previously reported for mutants of omp85 (20) or hgdD (22, 47, 48). Hence, the strains were spotted onto plates containing 10 μg/ml SDS. The presence of SDS resulted in a slight growth reduction of AFS-I-nuc-nui compared to the growth on BG11 plates (Fig. 3F, first and second panels, lanes 1 and 4). The growth of AFS-I-tpsB2 was comparable to that of AFS-I-nuc-nui (Fig. 3F, first and second panels, lane 1 versus lane 2). In contrast, the growth of AFS-I-tpsB1 was strongly reduced, but not as strongly as the growth of AFS-I-hgdD (Fig. 3F, first and second panels, lane 3 versus lanes 1 and 4). Addition of increasing amounts of lysozyme yielded a concentration-dependent growth delay of AFS-I-hgdD compared to AFS-I-nuc-nui (Fig. 3F, third to fifth panels, lanes 1 and 4). Here, AFS-I-tpsB1 was not affected (lane 3), while AFS-I-tpsB2 showed a growth reduction in the presence of 30 μg/ml lysozyme (Fig. 3F, lane 2; Fig. S5). Thus, the disruption of the two genes affects the outer membrane integrity but to a different extent.

The individual TpsB-like proteins affect antibiotic uptake of Anabaena sp.

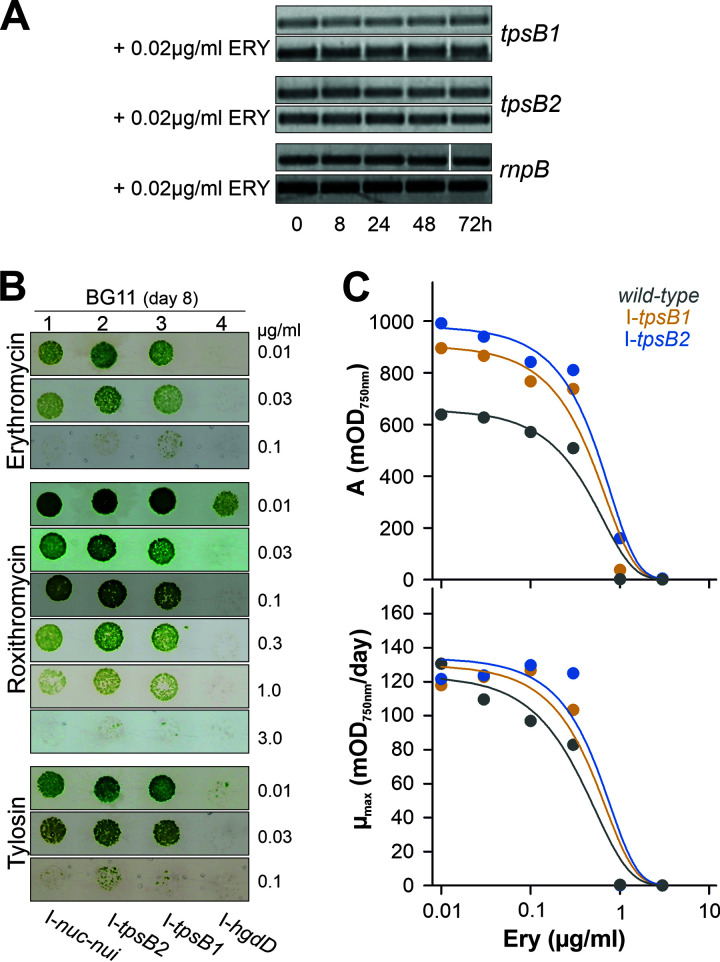

It was demonstrated that autotransporters can be involved in the transport of antibiotics (28, 50). Thus, the transcript levels of tpsB1 and tpsB2 were analyzed after transfer of the wild-type culture into BG11 medium containing 0.02 μg/ml erythromycin by PCR on cDNA generated from isolated mRNA (Fig. 4A). However, the transfer of Anabaena sp. into BG11 supplemented with erythromycin did not yield a drastic change of transcript abundance.

FIG 4.

Antibiotic sensitivity of tpsB1 and tpsB2 mutants. (A) Anabaena sp. grown for 7 days in BG11. RNA was isolated from Anabaena sp. at the indicated times after transfer to fresh BG11 (top panel in each pair) or BG11 supplemented with 0.020 g/ml erythromycin (bottom panel in each pair). The presence of transcripts of tpsB1, tpsB2, or rnpB was probed by RT-PCR. A representative result of three independent repetitions is shown. (B) Anabaena sp. strains were spotted (5 μl at an OD750 of 0.1) onto BG11 plates with indicated additions, and growth was monitored after 8 days. (The loading control on BG11 plates is shown in Fig. 3E.) (C) Wild-type Anabaena sp. (gray), AFS-I-tpsB1 (orange), and AFS-I-tpsB2 (blue) were grown in liquid BG11 with different concentrations of erythromycin. Growth curves were analyzed by the modified logistic equation, and the values for the maximal biomass gain (top) and the maximal growth rate (bottom) relative to antibiotic concentration are shown. Error bars are omitted for clarity; standard deviations for individual values were <15%. Lines show the least-square fit analysis to a sigmoidal equation for EC50 determination.

Although the transcript levels were not altered by addition of antibiotics, an importance of the type Vb system for antibiotic transport cannot be excluded. Thus, the sensitivity of the mutant strains to erythromycin, roxithromycin, and tylosin was investigated, as a loss of transport should result in enhanced resistance. Erythromycin and tylosin represent 14- and 16-membered lactone ring macrolides, respectively. Roxithromycin is comparable to erythromycin but contains an additional N-oxime chain. The growth of the two mutant strains was compared to that of AFS-I-hgdD, because HgdD is involved in metabolite export (22).

For the control strain AFS-I-nuc-nui, a differential sensitivity to the antibiotics was observed. When cultures with an optical density at 750 nm (OD750) of 0.1 were spotted, growth of the control strain was effectively inhibited by the addition of 0.1 μg/ml erythromycin and tylosin to the growth medium (Fig. 4B, lane 1). For roxithromycin, an inhibition of AFS-I-nuc-nui growth was observed only at 3 μg/ml (Fig. 4B, lane 1). As described before (22, 48), AFS-I-hgdD was hypersensitive to the selected antibiotics, as growth was observed only in the presence of 0.01 μg/ml roxithromycin (Fig. 4B, lane 4). In turn, AFS-I-tpsB1 and AFS-I-tpsB2 were slightly less sensitive than AFS-I-nuc-nui, which was most obvious at 0.01 or 0.03 μg/ml erythromycin, 0.3 and 1 μg/ml roxithromycin, and 0.1 μg/ml tylosin (Fig. 4B, lanes 2 and 3 versus lane 1).

To substantiate the difference in growth of the two mutant strains and wild-type, Anabaena sp. strains AFS-I-tpsB1 and AFS-I-tpsB2 were grown in liquid BG11 in the presence of different concentrations of erythromycin, and the growth curve was analyzed by a logistic equation (Fig. 4C; also, see Materials and Methods). The maximal biomass gain (A) reflected by the increase of the optical density (Fig. 4C, top) (for all strains, an A value of 1.7 ± 0.2 OD750 units was obtained in BG11) was lower in the wild type than in AFS-I-tpsB1 and AFS-I-tpsB2 at low concentrations of the antibiotic. In contrast, the maximal growth rate (Fig. 4C, bottom) (in BG11, the Anabaena sp. μmax was 0.16 ± 0.02, AFS-I-tpsB1 μmax was 0.17 ± 0.03, and AFS-I-tpsB2 μmax was 0.17 ± 0.02) of the wild type is reduced only at a concentration of 0.1 μg/ml erythromycin. Thus, the initial growth appears to be comparable in the presence of this antibiotic, while the maximal density differs between the cultures. The 50% effective concentration (EC50) of erythromycin is 0.6 ± 0.1 μg/ml for the wild type, 0.74 ± 0.04 μg/ml for AFS-I-tpsB1, and 0.93 ± 0.07 μg/ml for AFS-I-tpsB2, which is consistent with the observed higher tolerance of the mutants on plates. Thus, the two mutants have a phenotype related to the functionality of the outer membrane and exhibit an increased resistance against antibiotics.

The depletion of the TpsB-like proteins induces the Clp and Deg protease system.

TpsB proteins generally act as transporters. In a corresponding loss-of-function mutant, protein secretion is reduced or abolished. The retained substrates must be either stored in the cytosol or degraded. In AFS-I-hgdD, a strain with nonfunctional type I secretion system, upregulation of genes coding for proteases was documented (23). Hence, the transcript abundance of the genes coding for the Clp proteases, i.e., clpP1 (alr1238), clpP2 (alr3683), clpP3 (all4357) and clpR (all4358), as well as of genes coding for the Deg proteases, i.e., degQ1 (alr0702), degQ2 (all2008), degQ3 (alr5164), and degS (alr2758), was analyzed in wild-type Anabaena sp., AFS-I-tpsB1, and AFS-I-tpsB2 by quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

qRT-PCR values for genes coding for Clp and Deg proteasesa

| Gene | Wild-type 2−ΔCT | AFS-I-tpsB1 |

AFS-I-tpsB2 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2−ΔCT | P value | 2−ΔCT | P value | ||

| clpP1 | (2.1 ± 0.2) × 10−3 | (4.0 ± 1.0) × 10−3 | >0.050 | (1.1 ± 0.3) × 10−2 | 0.013 |

| clpP2 | (7.0 ± 1.0) × 10−4 | (1.5 ± 0.3) × 10−3 | 0.050 | (1.0 ± 0.4) × 10−2 | 0.001 |

| clpP3 | (6.0 ± 2.0) × 10−4 | (7.0 ± 2.0) × 10−4 | >0.050 | (8.0 ± 3.0) × 10−3 | 0.002 |

| clpR | (1.0 ± 0.2) × 10−3 | (9.0 ± 2.0) × 10−4 | >0.050 | (1.2 ± 0.4) × 10−2 | 0.001 |

| degQ1 | (9.0 ± 1.0) × 10−4 | (1.4 ± 0.4) × 10−3 | >0.050 | (3.4 ± 0.9) × 10−3 | 0.027 |

| degQ2 | (6.0 ± 1.0) × 10−5 | (7.0 ± 2.0) × 10−5 | >0.050 | (6.0 ± 2.0) × 10−4 | 0.005 |

| degQ3 | (1.0 ± 0.2) × 10−4 | (1.3 ± 0.3) × 10−4 | >0.050 | (8.0 ± 0.3) × 10−4 | 0.008 |

| degS | (2.4 ± 0.4) × 10−4 | (6.0 ± 1.0) × 10−4 | 0.034 | (3.1 ± 0.9) × 10−3 | <0.001 |

The 2−ΔCT values were determined by qRT-PCR and normalized to rnpB values. P values were determined by t test for statistically significant differences relative to wild-type values. Boldface highlights P values smaller than or equal to 0.005.

All genes coding for the proteases analyzed were significantly enhanced in AFS-I-tpsB2, and for clpP2, clpP3, clpR degQ2, and degS, an induction of more than 10-fold was observed (Table 1). In contrast, in AFS-I-tpsB1, only clpP2 and degS were significantly induced, but only 2- to 3-fold compared to the wild type (Table 1). However, both strains have a phenotype with respect to the upregulation of the cyanobacterial proteases. Hence, this result supports a function related to transport of the two proteins.

The genome of Anabaena sp. codes for 22 putative TpsA-like proteins.

The typical substrates of type Vb systems contain a hemagglutination activity domain with a characteristic NPNGI or NPNL amino acid motif (51). By bioinformatics approaches, 22 proteins with the form of this domain containing the NPNGI motif were identified in the Anabaena sp. proteome; however, none of the sequences contained the NPNL motif (Table 2). Remarkably, these 22 proteins have not been characterized previously. As expected, TpsA1 to TpsA11 (Fig. 2) constitute 11 of these candidates. For 19 of these 22 proteins, a secretion signal was identified (Table 2). For tpsA1 to tpsA11, as well as for five additional randomly selected candidates, a transcript was detected via PCR on cDNA when Anabaena sp. was grown in BG11 (Fig. 2; Fig. 5A, lanes 2).

TABLE 2.

Predicted substrates of TpsB-like proteins

| Protein | Length (aa) | Motif (aa position) | Signal sequence (CSa) |

|---|---|---|---|

| All5104 | 828 | NPTGI (120–124) | Yes (26–27) |

| All5105 | 740 | NPSGI (29–23) | No |

| All5106 | 815 | NPAGI (108–112) | Yes (26–27) |

| All5107 | 885 | NPSGI (110–114) | Yes (26–27) |

| All5108 | 733 | NPNGI (25–29) | No |

| All5110 | 795 | NPNGI (110–114) | Yes (26–27) |

| All5111 | 962 | NPNGI (119–123) | Yes (29–30) |

| All5112 | 833 | NPAGI (120–124) | Yes (26–27) |

| All5113 | 816 | NPAGI (120–124) | Yes (26–27) |

| All5114 | 918 | NPNGI (129–133) | Yes (35–36) |

| All5115 | 913 | NPSGI (128–132) | Yes (34–35) |

| All5280 | 770 | NPNGI (121–125) | Yes (28–29) |

| All4433 | 1,033 | NPNGI (124–128) | Yes (28–29) |

| Alr0366 | 1,152 | NPNGI (119–123) | Yes (25–26) |

| Alr0367 | 1,158 | NPNGI (119–123) | Yes (29–30) |

| Alr1906 | 805 | NPNGI (137–141) | Yes (38–39) |

| Alr1397 | 1,280 | NPNGI (91–95) | Yes (29–30) |

| Alr1184 | 850 | NPYGI (128–132) | Yes (27–28) |

| All2171 | 814 | NPQGI (127–131) | Yes (28–29) |

| All7313 | 688 | NPNGI (122–126) | Yes (27–28)b |

| All7235 | 843 | NPNGF (119–123) | Yes (28–29) |

| All7072 | 1,205 | NPNGI (135–139) | No |

CS, predicted cleavage site (amino acid positions).

The signal sequence for All7313 was predicted with a likelihood smaller than 0.5 but larger than 0.4.

FIG 5.

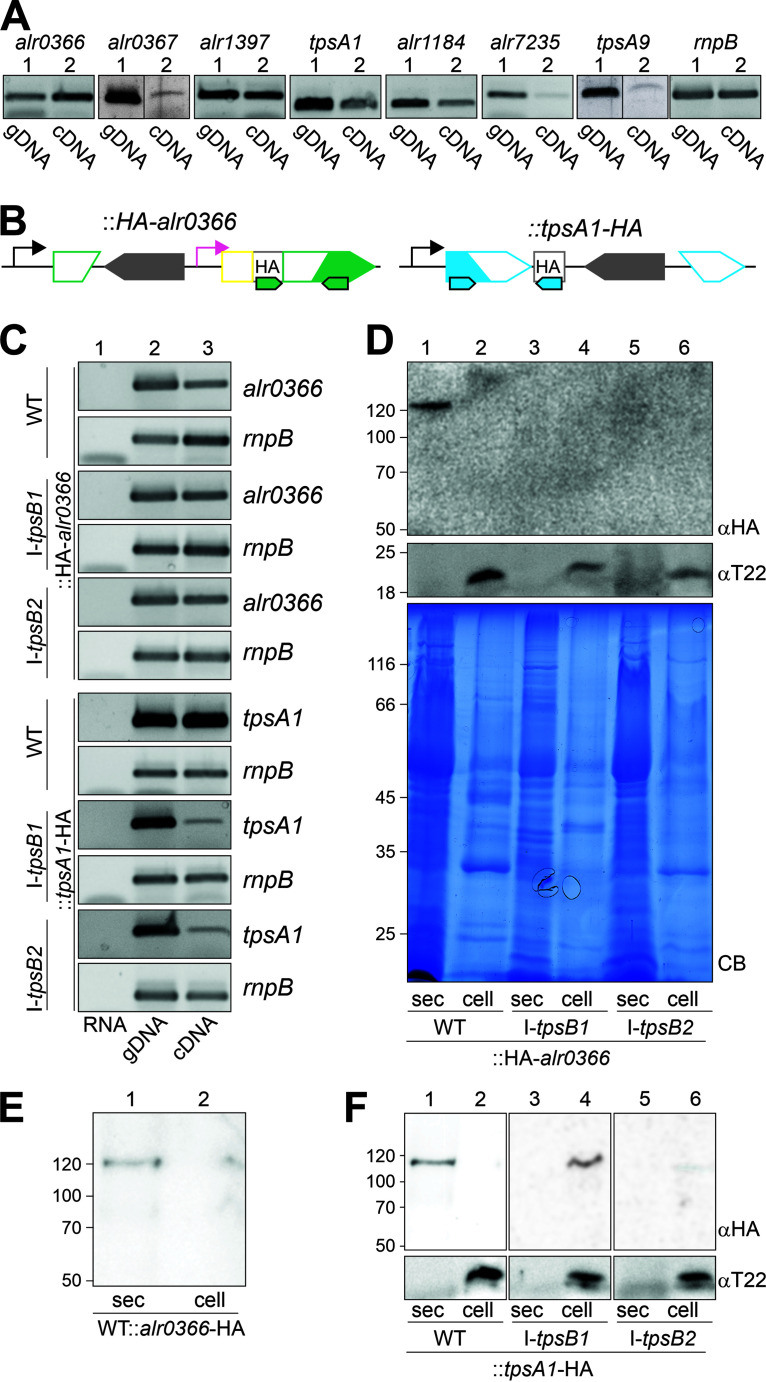

TpsB1 and TpsB2 are involved in the secretion of proteins in Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. (A) PCR on genomic DNA (gDNA; lanes 1) isolated from wild-type (WT) or cDNA generated from RNA isolated from the wild type (WT; lanes 2), with oligonucleotides to amplify the indicated genes. The amplification of rnpB from Anabaena sp. is shown as a control. (B) Strategy for HA tagging of the TpsB substrates. Pink indicates the –100 bp promoter fragment of the alr4215, yellow indicates the coding region of the signal sequence of All5112, and gray indicates the HA tag. (C) PCR on RNA in the absence of the reverse transcriptase (lane 1), gDNA (lane 2), or cDNA (lane 3) generated from RNA isolated from the strains indicated on the left with oligonucleotides to amplify the gene indicated on the right. The amplification of rnpB from Anabaena sp. is shown as a control. For all5115 and alr0366, oligonucleotides that amplify the transcript including the sequence coding for the HA tag were used. (D) The isolated and precipitated secretome (exoproteome [sec]; lanes 1, 3, and 5) and intact cells (lanes 2, 4, and 6) of the indicated strains were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie blue staining (CB) or Western blotting and decoration with antibodies against the HA tag (αHA) or the periplasmic Tic22 of Anabaena sp. (αT22). (E) The secretome (sec; lane 1) and intact cells (lane 2) of WT::alr0366-HA were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting and decoration with antibodies against the HA tag. (F) The secretome (sec; lanes 1, 3, and 5) and intact cells (lanes 2, 4, and 6) of the indicated strains were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting and decoration with antibodies against the HA tag (αHA) or the periplasmic Tic22 (αT22).

The cyanobacterial TpsB-like proteins are involved in TpsA-like protein secretion.

To probe for the function of the TpsB proteins in secretion, hemagglutinin (HA) fusion proteins of selected substrates with high expression were generated (Alr0366 and TpsA1) (Fig. 5B). The plasmids created for in vivo expression were integrated into the genomes of the wild type, AFS-I-tpsB1, and AFS-I-tpsB2. First, the transcription of the mutated gene that replaced the wild-type allele was confirmed by RT-PCR on isolated RNA from the individual strains (Fig. 5C). The method was controlled by amplification of rnpB in the absence (Fig. 5C, lane 1) or presence (lane 3) of the reverse transcriptase, and the primer efficiency was confirmed by PCR on genomic DNA (lane 2). Hence, the genes coding for the HA-tagged proteins were transcribed in all strains (Fig. 5C, lane 3). Thus, our result confirms that the promoter of alr4215 is active with respect to production of the HA-Alr0366 protein.

The strains were used to separate secreted and cellular proteins (Fig. 5D). The efficiency of the protocol for enrichment of proteins of the two fractions was confirmed by immunodecoration with antibodies against periplasmic Tic22 (Fig. 5D, αT22) (47, 52). In addition, the amount of proteins isolated was analyzed by Coomassie blue staining (Fig. 5D, CB).

The N-terminal HA-tagged Alr0366 was detectable in the secretome but not in the cell lysate of the wild type (Fig. 5D, lane 1 versus 2). The same was observed for the production of a C-terminal HA fusion of Alr0366 in the wild-type background (Fig. 5E, lane 1 versus 2). Thus, HA-tagged proteins were secreted and were detectable in the exoproteome with the expected molecular weights.

When the fractions of AFS-I-tpsB1 and AFS-I-tpsB2 producing the HA-tagged Alr0366 were analyzed, the HA-tagged protein could not be detected in either fraction (Fig. 5D, lanes 3 to 6), while the transcript of HA-alr0366 could be detected (Fig. 5C, lane 3). A similar result was reported for type I secretion substrates that accumulated in the cytoplasm or the periplasm (23). It is known that mRNA levels do not necessarily correlate with protein levels, which holds true especially for the changes of their abundancy in response to environmental alterations (53, 54). Thus, an impact of the tpsB disruption on protein translation cannot be ruled out completely. Nevertheless, by the following argumentation, it appears likely that the proteins are degraded in the mutants as result of a cytosolic accumulation due to reduced secretion efficiency. (i) All strains were grown under similar conditions, and results were reproducible at different ODs; thus, steady-state levels were analyzed rather than variations due to environmental alterations. (ii) Transcripts for the HA-tagged gene were obtained in wild-type and mutant strains. (iii) Differences in mRNA and protein abundance were attributed to regulation by noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs), posttranslational modifications, and variation of the protein half-life (55). However, ncRNA expression was not targeted by the mutation of tpsB1 and tpsB2. (iv) It has been noted that mRNA decay is generally faster than protein decay, and thus, single-cell studies yielded protein observations in the absence of detectable mRNA, but rarely vice versa (56). (v) The proteins monitored were detectable in the wild type, which confirmed their production in Anabaena sp. Thus, degradation of the HA-tagged protein is likely the result of cellular accumulation through reduced secretion and enhanced expression of protease-coding genes in the mutant (Table 1). In agreement with the conclusion, TpsA1-HA accumulated in the cells of the mutant strains (Fig. 5F, lanes 4 and 6), while in wild type, the protein was detected in the exoproteome (Fig. 5F, lane 1 versus 2). Thus, AFS-I-tpsB1 and AFS-I-tpsB2 show a reduced protein secretion efficiency.

DISCUSSION

Anabaena sp. contains two TpsB proteins, named TpsB1 and TpsB2 (Fig. 1). While the proteins share many similarities on the sequence level, a signal sequence was predicted only for TpsB2. The two proteins are encoded by genes that are not transcribed in an operonic structure together with putative substrates (Fig. 2), as typically found in pathogenic proteobacteria (26, 27, 37). In turn, 22 substrates were predicted (Table 2), of which only 11 are encoded in the same genomic region as TpsB2 (Fig. 2). Hence, the concept of an operonic organization of TpsB substrate- and transporter-coding genes is not conserved in cyanobacteria, at least not in Anabaena sp.

The function of the substrates and, consequently, the physiological relevance of the two-partner secretion system are still unknown and remain to be further investigated. However, the tested substrate-encoding genes are expressed in Anabaena sp. under normal growth conditions (Fig. 2 and 5). Several of them are induced in expression upon nitrogen starvation, as judged from the RNA deep sequencing data (41). This is consistent with the observed enhanced expression of the two tpsB genes under nitrogen starvation (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material) (41). The function of each individual gene is important but not essential for heterocyst formation, because growth of the mutant strains on BG110 is delayed but not abolished (Fig. 3).

Whether this is a result of a complementary function of the TpsB proteins resulting in an overall lower rate of substrate secretion by individual gene disruption remains to be explored. Such an overlapping function, however, would be consistent with the observed phenotype showing impairments in TpsA transport as exemplified for two substrates. A lower transport rate in the individual mutants would result in a low abundance of secreted HA-tagged proteins, and the final concentration might be too low for detection (Fig. 5). Consequently, the protein would not be detectable in the cellular fraction as observed for Alr0366. A similar observation was made for type I secretion system substrates (23). In turn, TpsA1-HA is detectable in the cell lysate, confirming the delay of secretion and the function of the two identified TpsB proteins in two-partner secretion (Fig. 3).

The participation of TpsB proteins in the uptake of antibiotics as proposed in other organisms (28, 50) might be proposed for the cyanobacterial system as well. While the disruption of the individual genes did not alter the maximal growth rate in the presence of low concentrations of erythromycin compared to the wild type (Fig. 4), the maximal biomass, as measured by OD750, was higher for the two mutants (Fig. 4). Consistent with a function of the two proteins in this process, the growth in the presence of antibiotics leads to a reduction of the maximal biomass by almost 2-fold for the mutants as well (from an A value of 1.7 in the absence of antibiotic to 1.0 at the lowest antibiotic concentration). As a consequence of the mutation, the EC50 for the toxicity of erythromycin is higher in the mutants than the wild type, but not to a large extent. Nevertheless, a feedback mechanism for tpsB1 or tpsB2 expression does not exist, because addition of erythromycin does not alter the transcript abundance of the two genes in a drastic manner (Fig. 4).

The two TpsB proteins are not essential for maintaining normal growth. However, especially for AFS-I-tpsB1, a careful analysis was required, as the strain was prone to back-recombination. This suggests at least an important function of the gene. Moreover, while a certain functional complementarity exists between the two TpsB proteins, the phenotypic analysis of the according mutants argues for an in part distinct function (Fig. 3 and 4). The disruption of the individual genes shows a certain alteration of outer membrane integrity, as AFS-I-tpsB1 shows a higher sensitivity to SDS than a control strain, while AFS-I-tpsB2 is somewhat more sensitive to lysozyme (Fig. 4). Both substances were used to probe for membrane integrity, and strains defective in outer membrane assembly through disruption of Omp85 (20), lipopolysaccharide export (15), or type I secretion (Fig. 3) typically demonstrate dramatic growth defects in the presence of these substances. We conclude that disruption of the TpsB protein function does not severely affect the outer membrane biogenesis per se. It is rather likely that the reduction of substrates alters the membrane integrity as a consequence of reduced secretion activity of the mutant strains. With respect to the function of the substrates, recent assumptions point, for example, to a function of TpsA in growth inhibition of neighboring cells and biofilm formation (57, 58). In addition, some of the systems are involved in metal uptake (59, 60). Hence, it will be important to further explore the function of the substrates of TpsB1 and TpsB2 in Anabaena sp. in order to understand the functional distinction of the two proteins on the one hand and the communication behavior of Anabaena sp. on the other.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

General procedures.

The isolation of genomic DNA from Anabaena sp. was carried out using the standard protocol (61). Plasmid DNA from E. coli cultivated in LB medium was performed according to standard methods (62). PCR with Taq or Pfu polymerase and the oligonucleotides listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material to amplify defined DNA sequences was performed as described previously (63). Plasmid preparation was performed by standard methods (e.g., see references 20 and 21). Constructs were confirmed by sequencing (GATC Biotech).

Identification of putative cyanobacterial autotransporters.

Sequences of cyanobacterial proteins putatively involved in type V secretion were identified by BLAST search on NCBI (64) (settings: blastp; BLOSUM62; gap costs, existence, 11, and extension, 1; top 500 sequences). Based on references 26 and 27, the amino acid sequence of IgaA (N. meningitides; accession no. AHW75314; type Va), EstA (P. aeruginosa; accession no. AEV51797.1; type Va), YadA (Y. enterocolitica; accession no. CAA32086.1; type Vc), PlpD (P. aeruginosa; accession no. KAF0594254.1; type Vd), FplA (F. nucleatum; accession no. WP_158412434.1; type Vd), intimin (E. coli; WP_073514622.1; type Ve), and BapA (A. ruhlandii; CAB3655883.1; type Ve) were used as queries. Identified cyanobacterial sequences were used as bait to identify further putative cyanobacterial protein sequences. Sequences of type Vb were searched for with TpsB1 and TpsB2 (10) sequences as queries. For discrimination between Omp85 and TpsB, sequences of Alr0075, Alr5893, and Alr2269 (10, 20) were used as bait, but an overlap with proteins of the type Vb family was not observed using the above-mentioned settings. Subsequently, sequences annotated as partial were removed. All identified sequences were filtered for redundancy with CD-HIT using a 90% cutoff (65), and a representative sequence for each group was selected.

Bioinformatic characterization of sequences identified in Anabaena sp.

To predict potential signal sequences, the SignalP server was used (40). Information about domains was extracted from public resources like NCBI (64). Prediction of β-strands was performed as previously established (66, 67) and with PRED-TMBB (68, 69).

Generation of plasmid insertion mutants of Anabaena sp. for gene disruption.

A 563-bp fragment of the coding region of tpsB1 and a 588-bp fragment of the coding region of tpsB2 were produced by PCR on genomic DNA isolated from wild-type Anabaena sp. BglII restriction sites were introduced for cloning into BamHI-digested pCSV3 containing the spectinomycin-streptomycin (Sp/Sm) resistance cassette (43). The generated plasmids were used for conjugation to generate AFS-I-tpsB1 and AFS-I-tpsB2, respectively. Conjugation of Anabaena sp. was performed as described in reference 70.

Generation of plasmid insertion mutants of Anabaena sp. for substrate tagging.

pALH11 with a neomycin resistance cassette (23) was modified as follows. To allow fusion of an HA tag to the N and C termini of the encoded protein, two multiple cloning sites were inserted with recognition sequences for the endonucleases NdeI and XhoI at the 5′ end and HindIII and NheI at the 3′ end of the coding region for the HA tag. For that, NdeI sites were removed from the coding region of the HA tag within the origin of replication (Ori) and in the neomycin resistance cassette, an NcoI site was removed from the neomycin resistance cassette, and one XhoI site was removed from the vector backbone by mutagenesis PCR introducing silent mutations. In addition, the coding region for the signal sequence of all5112 was introduced preceding the NdeI cleavage site. This vector allows the cloning of the mature domain of the protein while fusing an N-terminal HA tag. The plasmid is annotated as pALH11_SP_HA. DNA fragments of alr0366 and all5115 representing the 3′ ends without a stop codon or the 5′ end coding for the N terminus of the mature domain of Alr0366 were amplified by PCR on genomic DNA isolated from Anabaena sp. The fragment was inserted after restriction with according enzymes and the generated plasmids were used for conjugation in the wild type, AFS-I-tpsB1, and AFS-I-tpsB2. Conjugation of Anabaena sp. was performed as described in reference 70.

Growth of Anabaena sp.

The strains of Anabaena sp. used here are listed in Table 3. Anabaena sp. cultures were grown in liquid BG11 (100× BG11 [1 liter]: 7.5 g MgSO4·7H2O, 3.6 g CaCl2·2H2O, 0.6 g citric acid, 0.6 g ferric-ammonium citrate, 93 mg Na2EDTA, 2 g Na2CO3, 286 mg H3BO3, 181 mg MnCl2·4H2O, 22.2 mg ZnSO4·7H2O, 39 mg NaMoO4·2H2O, 7.9 mg CuSO4·5H2O, 4.94 mg CoCl2·6H2O) with 17.6 mM NaNO3 or in BG110 (same composition as BG11 but without NaNO3) at 30°C with white light (70 E; OSRAM L 58 W/954 Lumilux De Luxe, daylight), irradiated, and shaken at 85 rpm (71). Growth on solid medium was performed on BG11 plates with 1% Bacto agar (Otto Nord Wald, Hamburg, Germany) including additions as indicated. For growth of mutants, spectinomycin and streptomycin (5 μg/ml for plates and 3 μg/ml for liquid cultures) were used as selection markers. For phenotyping on plates, Anabaena sp. strains were grown in BG11. Portions (5 μl) of cultures at an OD750 of 1 were spotted onto plates in three dilutions (1:10, 1:100, 1:1,000). Incubation was performed under constant white light at 30°C. For phenotyping in liquid medium, Anabaena sp. cultures were inoculated to an OD750 of 0.05. The OD750 was then measured at indicated intervals with a Jasco V-630 spectrophotometer. For the analysis of the growth in liquid BG11 in the presence of erythromycin, growth curves were recorded and analyzed by the modified logistic equation (76): y = (A − y0)/{1 + exp[4μ(λ − t)/A + 2]} + y0. The values for the maximal biomass yield (A), the maximum of the growth rate (μ), the lag time (λ), and the starting absorbance (y0) were determined by least-square fit analysis and analyzed by a sigmoidal dose response curve to determine the EC50: f = y0 + [(m − y0)/(1 + 10logEC50 − log[C])], where y0 is the baseline, m is the maximal value, and [C] is the concentration of the antibiotics.

TABLE 3.

Strains of Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 used in this studya

| Strain | Genotype | Resistance | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anabaena sp. wild type | Enrique Flores, Seville, Spain | ||

| CSR10 | alr4167::pCSV3 | Sp/Sm | 75 |

| AFS-I-nuc-nui | nuc-nui:: pCSV3 | Sp/Sm | 46 |

| AFS-I-omp85 | alr2269::pCSV3 | Sp/Sm | 20 |

| AFS-I-hgdD | alr2887::pCSV3 | Sp/Sm | 22 |

| AFS-I-tpsB1 | alr1659::pCSV3 | Sp/Sm | This study |

| AFS-I-tpsB2 | all5116::pCSV3 | Sp/Sm | This study |

| WT::HA-alr0366 | Neo | This study | |

| AFS-I-tpsB1::HA-alr0366 | alr1659::pCSV3 | Sp/Sm/Neo | This study |

| AFS-I-tpsB2::HA-alr0366 | all5116::pCSV3 | Sp/Sm/Neo | This study |

| WT::alr0366-HA | Neo | This study | |

| WT::all5155-HA | Neo | This study | |

| AFS-I-tpsB1::tpsA1-HA | alr1659::pCSV3 | Sp/Sm/Neo | This study |

| AFS-I-tpsB2::tpsA1-HA | all5116::pCSV3 | Sp/Sm/Neo | This study |

AFS, Anabaena sp. mutant created in Frankfurt by the Schleiff group; I, plasmid insertion into the gene; HA, human influenza hemagglutinin tag; Sp, spectinomycin; Sm, streptomycin; Neo, neomycin.

RNA isolation, RT-PCR, and qPCR.

Isolation of RNA from Anabaena sp. cultures grown in 10 or 50 ml BG11 medium and subsequent cDNA synthesis was performed as described before (46, 72). qRT-PCR was performed using a StepOnePlus cycler (Thermo Fisher Scientific); gene-specific oligonucleotides utilized are given in Table S1. Template cDNA was diluted 1:3 at minimum, and PowerUp SYBR green master mix (Applied Biosystems) was used as described in the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA from each sample was tested similarly to cDNA in order exclude DNA contaminations. Cycling conditions were initially 50°C for 2 min and 95°C for 2 min followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s. rnpB was utilized as a housekeeping gene.

Isolation of the secretome/exoproteome.

Cultures were grown for 6 days to an OD750 of >0.5. Cells were pelleted by gentle centrifugation (5,000 × g, 10 min), and supernatant was separated. Cells were collected and used as intact cell lysate. The supernatant was filtered and ammonium sulfate was added (706 g/liter). The solution was stirred at 4°C overnight. The proteins were pelleted by centrifugation (20,000 × g, 25 min, 4°C), and the pellet was resuspended in 1 ml HEPES-KOH (pH 7.6). The protein fractions were loaded on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel and plotted on polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes for 3 h. The antibodies used were described before (antibody against Tic22) (47) or purchased (HA; Hiss Diagnostics, Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany).

Software.

Information on genes was extracted from public resources like the KEGG database, ALCOdb, NCBI, and others (60, 73, 74). Clone Manager professional suite 9.0 (Scientific & Educational Software) was used to plan cloning and restrictions. Sequencer 4.9 Demo (Gene Codes Corporation) was used to align sequenced DNA sequences with corresponding reference sequences. SigmaPlot was used to analyze and visualize the quantitative data. The identification of proteins with the hemagglutination activity domain (PF05860) was performed with the Pfam protein family database (http://pfam.xfam.org/search) (77). Identified proteins are listed in Table 2.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Maike Ruprecht and Daniela Bublack for constant support and Rafael Pernil for critical discussion. We thank Christina Lehmann, Marie Heß, and Alessia Girschik for help in preparation and testing of constructs and mutants.

The work was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft DFG SCHL585/7-2 to E.S. and by IMPRES to G.N.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mirus O, Hahn A, Schleiff E. 2010. Outer membrane proteins, p 175–230. In König H, Claus H, Varma A (ed), Prokaryotic cell wall compounds. Structure and biochemistry. Springer-Verlag, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hahn A, Schleiff E. 2014. The cell envelope, p 29–87. In Flores E, Herrero A (ed), The cell biology of cyanobacteria. Caister Academic Press, Norfolk, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schuergers N, Wilde A. 2015. Appendages of the cyanobacterial cell. Life (Basel) 5:700–715. doi: 10.3390/life5010700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huertas MJ, López-Maury L, Giner-Lamia J, Sánchez-Riego AM, Florencio FJ. 2014. Metals in cyanobacteria: analysis of the copper, nickel, cobalt and arsenic homeostasis mechanisms. Life (Basel) 4:865–886. doi: 10.3390/life4040865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lutzu GA, Turgut Dunford N. 2018. Interactions of microalgae and other microorganisms for enhanced production of high-value compounds. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 23:1487–1504. doi: 10.2741/4656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ger KA, Urrutia-Cordero P, Frost PC, Hansson LA, Sarnelle O, Wilson AE, Lürling M. 2016. The interaction between cyanobacteria and zooplankton in a more eutrophic world. Harmful Algae 54:128–144. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2015.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fresenborg LS, Graf J, Schätzle H, Schleiff E. 2020. Iron homeostasis of cyanobacteria: advancements in siderophores and metal transporters, p 85–117. In Singh PK, Kumar A, Sing VK, Shrivastava AK (ed), Advances in cyanobacterial biology. Academic Press, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stebegg R, Schmetterer G, Rompel A. 2019. Transport of organic substances through the cytoplasmic membrane of cyanobacteria. Phytochem 157:206–218. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2018.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Day PM, Theg SM. 2018. Evolution of protein transport to the chloroplast envelope membranes. Photosynth Res 138:315–326. doi: 10.1007/s11120-018-0540-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nicolaisen K, Hahn A, Schleiff E. 2009. The cell wall in heterocyst formation by Anabaena sp. PCC 7120. J Basic Microbiol 49:5–24. doi: 10.1002/jobm.200800300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kowata H, Tochigi S, Takahashi H, Kojima S. 2017. Outer membrane permeability of cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803: studies of passive diffusion of small organic nutrients reveal the absence of classical porins and intrinsically low permeability. J Bacteriol 199:e00371-17. doi: 10.1128/JB.00371-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dong H, Tang X, Zhang Z, Dong C. 2017. Structural insight into lipopolysaccharide transport from the Gram-negative bacterial inner membrane to the outer membrane. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids 1862:1461–1467. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2017.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sperandeo P, Martorana AM, Polissi A. 2017. The lipopolysaccharide transport (Lpt) machinery: a nonconventional transporter for lipopolysaccharide assembly at the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria. J Biol Chem 292:17981–17990. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R117.802512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simm S, Keller M, Selymesi M, Schleiff E. 2015. The composition of the global and feature specific cyanobacterial core-genomes. Front Microbiol 6:219. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsueh YC, Brouwer EM, Marzi J, Mirus O, Schleiff E. 2015. Functional properties of LptA and LptD in Anabaena sp. PCC 7120. Biol Chem 396:1151–1162. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2014-0322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haarmann R, Ibrahim M, Stevanovic M, Bredemeier R, Schleiff E. 2010. The properties of the outer membrane localized lipid A transporter LptD. J Phys Condens Matter 22:454124. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/22/45/454124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Konovalova A, Kahne DE, Silhavy TJ. 2017. Outer membrane biogenesis. Annu Rev Microbiol 71:539–556. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-090816-093754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reumann S, Davila-Aponte J, Keegstra K. 1999. The evolutionary origin of the protein-translocating channel of chloroplastic envelope membranes: identification of a cyanobacterial homolog. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96:784–789. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.2.784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bölter B, Soll J, Schulz A, Hinnah S, Wagner R. 1998. Origin of a chloroplast protein importer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95:15831–15836. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nicolaisen K, Mariscal V, Bredemeier R, Pernil R, Moslavac S, López-Igual R, Maldener I, Herrero A, Schleiff E, Flores E. 2009. The outer membrane of a heterocyst-forming cyanobacterium is a permeability barrier for uptake of metabolites that are exchanged between cells. Mol Microbiol 74:58–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moslavac S, Nicolaisen K, Mirus O, Al Dehni F, Pernil R, Flores E, Maldener I, Schleiff E. 2007. A TolC-like protein is required for heterocyst development in Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. J Bacteriol 189:7887–7895. doi: 10.1128/JB.00750-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hahn A, Stevanovic M, Mirus O, Schleiff E. 2012. The TolC-like protein HgdD of the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 is involved in secondary metabolite export and antibiotic resistance. J Biol Chem 287:41126–41138. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.396010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hahn A, Stevanovic M, Brouwer E, Bublak D, Tripp J, Schorge T, Karas M, Schleiff E. 2015. Secretome analysis of Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 and the involvement of the TolC-homologue HgdD in protein secretion. Environ Microbiol 17:767–780. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oliveira P, Martins NM, Santos M, Pinto F, Büttel Z, Couto NA, Wright PC, Tamagnini P. 2016. The versatile TolC-like Slr1270 in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Environ Microbiol 18:486–502. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilde A, Mullineaux CW. 2015. Motility in cyanobacteria: polysaccharide tracks and type IV pilus motors. Mol Microbiol 98:998–1001. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leo JC, Grin I, Linke D. 2012. Type V secretion: mechanism(s) of autotransport through the bacterial outer membrane. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 367:1088–1101. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meuskens I, Saragliadis A, Leo JC, Linke D. 2019. Type V secretion systems: an overview of passenger domain functions. Front Microbiol 10:1163. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clantin B, Delattre AS, Rucktooa P, Saint N, Méli AC, Locht C, Jacob-Dubuisson F, Villeret V. 2007. Structure of the membrane protein FhaC: a member of the Omp85-TpsB transporter superfamily. Science 317:957–961. doi: 10.1126/science.1143860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Noinaj N, Kuszak AJ, Gumbart JC, Lukacik P, Chang H, Easley NC, Lithgow T, Buchanan SK. 2013. Structural insight into the biogenesis of β-barrel membrane proteins. Nature 501:385–390. doi: 10.1038/nature12521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moslavac S, Mirus O, Bredemeier R, Soll J, von Haeseler A, Schleiff E. 2005. Conserved pore-forming regions in polypeptide-transporting proteins. FEBS J 272:1367–1378. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sánchez-Pulido L, Devos D, Genevrois S, Vicente M, Valencia A. 2003. POTRA: a conserved domain in the FtsQ family and a class of beta-barrel outer membrane proteins. Trends Biochem Sci 28:523–526. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2003.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jacob-Dubuisson F, Villeret V, Clantin B, Delattre AS, Saint N. 2009. First structural insights into the TpsB/Omp85 superfamily. Biol Chem 390:675–684. doi: 10.1515/BC.2009.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Julio SM, Cotter PA. 2005. Characterization of the filamentous hemagglutinin-like protein FhaS in Bordetella bronchiseptica. Infect Immun 73:4960–4971. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.8.4960-4971.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Delattre AS, Saint N, Clantin B, Willery E, Lippens G, Locht C, Villeret V, Jacob-Dubuisson F. 2011. Substrate recognition by the POTRA domains of TpsB transporter FhaC. Mol Microbiol 81:99–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baud C, Hodak H, Willery E, Drobecq H, Locht C, Jamin M, Jacob-Dubuisson F. 2009. Role of DegP for two-partner secretion in Bordetella. Mol Microbiol 74:315–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nash ZM, Cotter PA. 2019. Regulated, sequential processing by multiple proteases is required for proper maturation and release of Bordetella filamentous hemagglutinin. Mol Microbiol 112:820–836. doi: 10.1111/mmi.14318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guérin J, Bigot S, Schneider R, Buchanan SK, Jacob-Dubuisson F. 2017. Two-partner secretion: combining efficiency and simplicity in the secretion of large proteins for bacteria-host and bacteria-bacteria Interactions. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 7:148. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abby SS, Cury J, Guglielmini J, Néron B, Touchon M, Rocha EP. 2016. Identification of protein secretion systems in bacterial genomes. Sci Rep 6:23080. doi: 10.1038/srep23080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Federhen S. 2015. Type material in the NCBI Taxonomy Database. Nucleic Acids Res 43:D1086–D1098. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Almagro Armenteros JJ, Tsirigos KD, Sønderby CK, Petersen TN, Winther O, Brunak S, von Heijne G, Nielsen H. 2019. SignalP 5.0 improves signal peptide predictions using deep neural networks. Nat Biotechnol 37:420–423. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0036-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Flaherty BL, Van Nieuwerburgh F, Head SR, Golden JW. 2011. Directional RNA deep sequencing sheds new light on the transcriptional response of Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 to combined-nitrogen deprivation. BMC Genomics 12:332. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mitschke J, Vioque A, Haas F, Hess WR, Muro-Pastor AM. 2011. Dynamics of transcriptional start site selection during nitrogen stress-induced cell differentiation in Anabaena sp. PCC7120. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:20130–20135. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112724108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Picossi S, Montesinos ML, Pernil R, Lichtlé C, Herrero A, Flores E. 2005. ABC‐type neutral amino acid permease N‐I is required for optimal diazotrophic growth and is repressed in the heterocysts of Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. Mol Microbiol 57:1582–1592. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nicolaisen K, Moslavac S, Samborski A, Valdebenito M, Hantke K, Maldener I, Muro-Pastor AM, Flores E, Schleiff E. 2008. Alr0397 is an outer membrane transporter for the siderophore schizokinen in Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. J Bacteriol 190:7500–7507. doi: 10.1128/JB.01062-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Olmedo-Verd E, Muro-Pastor AM, Flores E, Herrero A. 2006. Localized induction of the ntcA regulatory gene in developing heterocysts of Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. J Bacteriol 188:6694–6699. doi: 10.1128/JB.00509-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stevanovic M, Lehmann C, Schleiff E. 2013. The response of the TonB-dependent transport network in Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 to cell density and metal availability. Biometals 26:549–560. doi: 10.1007/s10534-013-9644-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tripp J, Hahn A, Koenig P, Flinner N, Bublak D, Brouwer EM, Ertel F, Mirus O, Sinning I, Tews I, Schleiff E. 2012. Structure and conservation of the periplasmic targeting factor Tic22 protein from plants and cyanobacteria. J Biol Chem 287:24164–24173. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.341644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hahn A, Stevanovic M, Mirus O, Lytvynenko I, Pos KM, Schleiff E. 2013. The outer membrane TolC-like channel HgdD is part of tripartite resistance-nodulation-cell division (RND) efflux systems conferring multiple-drug resistance in the Cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. PCC7120. J Biol Chem 288:31192–31205. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.495598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ernst A, Black T, Cai Y, Panoff JM, Tiwari DN, Wolk CP. 1992. Synthesis of nitrogenase in mutants of the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 affected in heterocyst development or metabolism. J Bacteriol 174:6025–6032. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.19.6025-6032.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oomen CJ, van Ulsen P, van Gelder P, Feijen M, Tommassen J, Gros P. 2004. Structure of the translocator domain of a bacterial autotransporter. EMBO J 23:1257–1266. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Clantin B, Hodak H, Willery E, Locht C, Jacob-Dubuisson F, Villeret V. 2004. The crystal structure of filamentous hemagglutinin secretion domain and its implications for the two-partner secretion pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:6194–6199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400291101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brouwer EM, Ngo G, Yadav S, Ladig R, Schleiff E. 2019. Tic22 from Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 with holdase function involved in outer membrane protein biogenesis shuttles between plasma membrane and Omp85. Mol Microbiol 111:1302–1316. doi: 10.1111/mmi.14222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Waldbauer JR, Rodrigue S, Coleman ML, Chisholm SW. 2012. Transcriptome and proteome dynamics of a light-dark synchronized bacterial cell cycle. PLoS One 7:e43432. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xiong Q, Feng J, Li ST, Zhang GY, Qiao ZX, Chen Z, Wu Y, Lin Y, Li T, Ge F, Zhao JD. 2015. Integrated transcriptomic and proteomic analysis of the global response of Synechococcus to high light stress. Mol Cell Proteomics 14:1038–1053. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M114.046003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen WH, van Noort V, Lluch-Senar M, Hennrich ML, Wodke JA, Yus E, Alibés A, Roma G, Mende DR, Pesavento C, Typas A, Gavin AC, Serrano L, Bork P. 2016. Integration of multi-omics data of a genome-reduced bacterium: prevalence of post-transcriptional regulation and its correlation with protein abundances. Nucleic Acids Res 44:1192–1202. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Taniguchi Y, Choi PJ, Li GW, Chen H, Babu M, Hearn J, Emili A, Xie XS. 2010. Quantifying E. coli proteome and transcriptome with single-molecule sensitivity in single cells. Science 329:533–538. doi: 10.1126/science.1188308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ruhe ZC, Low DA, Hayes CS. 2013. Bacterial contact-dependent growth inhibition. Trends Microbiol 21:230–237. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Garcia EC, Perault AI, Marlatt SA, Cotter PA. 2016. Interbacterial signaling via Burkholderia contact-dependent growth inhibition system proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:8296–8301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1606323113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Molina MA, Ramos JL, Espinosa-Urgel M. 2006. A two-partner secretion system is involved in seed and root colonization and iron uptake by Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Environ Microbiol 8:639–647. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cope LD, Thomas SE, Latimer JL, Slaughter CA, Müller-Eberhard U, Hansen EJ. 1994. The 100 kDa haem:haemopexin-binding protein of Haemophilus influenzae: structure and localization. Mol Microbiol 13:863–873. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cai Y, Wolk CP. 1990. Use of a conditionally lethal gene in Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 to select for double recombinants and to entrap insertion sequences. J Bacteriol 172:3138–3145. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.6.3138-3145.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Birnboim HC, Doly J. 1979. A rapid alkaline extraction procedure for screening recombinant plasmid DNA. Nucleic Acids Res 7:1513–1523. doi: 10.1093/nar/7.6.1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mullis KB, Faloona FA. 1987. Specific synthesis of DNA in vitro via a polymerase‐catalyzed chain reaction. Methods Enzymol 155:335–350. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)55023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.NCBI Resource Coordinators. 2018. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res 46:D8–D13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Huang Y, Niu B, Gao Y, Fu L, Li W. 2010. CD-HIT suite: a web server for clustering and comparing biological sequences. Bioinformatics 26:680–682. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mirus O, Schleiff E. 2005. Prediction of beta-barrel membrane proteins by searching for restricted domains. BMC Bioinformatics 6:254. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Flinner N, Schleiff E, Mirus O. 2012. Identification of two voltage-dependent anion channel-like protein sequences conserved in Kinetoplastida. Biol Lett 8:446–449. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2011.1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bagos PG, Liakopoulos TD, Spyropoulos IC, Hamodrakas SJ. 2004. PRED-TMBB: a web server for predicting the topology of beta-barrel outer membrane proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 32:W400–W404. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tsirigos KD, Elofsson A, Bagos PG. 2016. PRED-TMBB2: improved topology prediction and detection of beta-barrel outer membrane proteins. Bioinformatics 32:i665–i671. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Elhai J, Vepritskiy A, Muro-Pastor AM, Flores E, Wolk CP. 1997. Reduction of conjugal transfer efficiency by three restriction activities of Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. J Bacteriol 179:1998–2005. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.6.1998-2005.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rippka R, Deruelles J, Waterbury JB, Herdman M, Stanier RY. 1979. Generic assignments, strain histories and properties of pure cultures of cyanobacteria. J Gen Microbiol 111:1–61. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Stevanovic M, Hahn A, Nicolaisen K, Mirus O, Schleiff E. 2012. The components of the putative iron transport system in the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. PCC 7120. Environ Microbiol 14:1655–1670. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kanehisa M, Furumichi M, Tanabe M, Sato Y, Morishima K. 2017. KEGG: new perspectives on genomes, pathways, diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Res 45:D353–D361. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Aoki Y, Okamura Y, Ohta H, Kinoshita K, Obayashi T. 2016. ALCOdb: gene coexpression database for microalgae. Plant Cell Physiol 57:e3. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcv190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pernil R, Picossi S, Mariscal V, Herrero A, Flores E. 2008. ABC‐type amino acid uptake transporters Bgt and N‐II of Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 share an ATPase subunit and are expressed in vegetative cells and heterocysts. Mol Microbiol 67:1067–1080. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zwietering MH, Jongenburger I, Rombouts FM, van 't Riet K. 1990. Modeling of the bacterial growth curve. Appl Environ Microbiol 56:1875–1881. doi: 10.1128/AEM.56.6.1875-1881.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Finn RD, Bateman A, Clements J, Coggill P, Eberhardt RY, Eddy SR, Heger A, Hetherington K, Holm L, Mistry J, Sonnhammer EL, Tate J, Punta M. 2014. Pfam: the protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res 42:D222–D230. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.