Abstract

Background

Pediatric bacterial meningitis (PBM) remains a devastating disease that causes substantial neurological morbidity and mortality worldwide. However, there are few large-scale studies on the pathogens causing PBM and their antimicrobial resistance (AMR) patterns in China. The present multicenter survey summarized the features of the etiological agents of PBM and characterized their AMR patterns.

Methods

Patients diagnosed with PBM were enrolled retrospectively at 13 children’s hospitals in China from 2016 to 2018 and were screened based on a review of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) microbiology results. Demographic characteristics, the causative organisms and their AMR patterns were systematically analyzed.

Results

Overall, 1193 CSF bacterial isolates from 1142 patients with PBM were obtained. The three leading pathogens causing PBM were Staphylococcus epidermidis (16.5%), Escherichia coli (12.4%) and Streptococcus pneumoniae (10.6%). In infants under 3 months of age, the top 3 pathogens were E. coli (116/523; 22.2%), Enterococcus faecium (75/523; 14.3%), and S. epidermidis (57/523; 10.9%). However, in children more than 3 months of age, the top 3 pathogens were S. epidermidis (140/670; 20.9%), S. pneumoniae (117/670; 17.5%), and Staphylococcus hominis (57/670; 8.5%). More than 93.0% of E. coli isolates were sensitive to cefoxitin, piperacillin/tazobactam, cefoperazone/sulbactam, amikacin and carbapenems, and the resistance rates to ceftriaxone, cefotaxime and ceftazidime were 49.4%, 49.2% and 26.4%, respectively. From 2016 to 2018, the proportion of methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative Staphylococcus isolates (MRCoNS) declined from 80.5 to 72.3%, and the frequency of penicillin-resistant S. pneumoniae isolates increased from 75.0 to 87.5%. The proportion of extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing E. coli fluctuated between 44.4 and 49.2%, and the detection rate of ESBL production in Klebsiella pneumoniae ranged from 55.6 to 88.9%. The resistance of E. coli strains to carbapenems was 5.0%, but the overall prevalence of carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae (CRKP) was high (54.5%).

Conclusions

S. epidermidis, E. coli and S. pneumoniae were the predominant pathogens causing PBM in Chinese patients. The distribution of PBM causative organisms varied by age. The resistance of CoNS to methicillin and the high incidence of ESBL production among E. coli and K. pneumoniae isolates were concerning. CRKP poses a critical challenge for the treatment of PBM.

Keywords: Bacterial meningitis, Pediatric, Bacterial pathogens, Antimicrobial resistance

Background

Pediatric bacterial meningitis (PBM) is a devastating infectious disease that causes substantial neurological morbidity and mortality worldwide [1]. Studies have estimated that the annual incidence of PBM in China fluctuated between 7.0 and 22.3 cases per 100 000 children under 5 years old [2]. The case fatality rate was estimated to be 3.0–10.6% [3–5], and survivors had relatively high percentages of neurological complications [3, 5, 6]. Therefore, early diagnosis and prompt use of rational antimicrobial therapies are vital to alleviate the burdens of this disease.

The options of empirical antimicrobial agents in clinical practice mainly depend on the causative organisms and their antimicrobial resistance (AMR) patterns. Immediate and effective antibiotic use for pediatric populations with PBM is relevant for achieving a favorable outcome [7]. However, the spectrum of pathogens causing PBM varies in different reports [8–11]. Data from England and Wales during 2004–2011 indicated that the predominant organisms responsible for PBM were Neisseria meningitidis (N. meningitidis), Streptococcus pneumoniae (S. pneumoniae), and Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) [8]. Meningitis surveillance during 2011–2016 in African regions demonstrated that the two leading causative agents identified were S. pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae (H. influenzae) [9, 10]. One study from the southwestern province of China reported that approximately 46.0% of PBM cases were caused by Escherichia coli (E. coli) and S. pneumoniae from 2012 to 2015 [11]. The etiology of PBM varies greatly based on several factors, including geography, time, and patient age [8, 11–13]. In addition to their isolation rates, their AMR patterns vary substantially [14]. Therefore, timely analysis and reporting of the causative agents of PBM and the AMR profiles play vital roles in helping physicians choose the proper empirical therapy.

To the best of our knowledge, there are limited large-scale studies examining the pathogens of PBM in China. Data on the susceptibility patterns of prevailing causative bacteria in pediatric populations are also lacking in China. To gain a better understanding of evidence-based empirical antibiotic treatment and infection control for children with PBM, the present multicenter retrospective survey investigated the features of the etiological agents responsible for PBM and characterized their AMR patterns in China from 2016 to 2018.

Methods

Study design and participating hospitals

This national multicenter survey was based on the diagnosis of bacterial meningitis (BM) by cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) culture and was performed retrospectively in 13 children’s hospitals (11 tertiary hospitals and 2 secondary hospitals) in China from January 2016 to December 2018. Thirteen hospitals in 12 provinces provided data for our research. Most of these hospitals were the largest local medical institutions that provided treatment, health consultation or other clinical services for children and/or women. The geographic locations of the participating hospitals are shown in Fig. 1. All participating hospitals have adequate facilities and qualified specialists to conduct bacterial culture and assess antimicrobial susceptibility.

Fig. 1.

Locations of participating hospitals (red dots) in this study

Study population

Children (< 18 years of age) with BM were enrolled at each hospital based on the review of CSF microbiology results. Patients with clinical manifestations and a positive CSF culture were diagnosed with confirmed BM on the basis of the World Health Organization (WHO) case definition [15]. All eligible patients received antibiotic therapies against target CSF bacterial isolates according to the attending physician’s comprehensive assessment [16]. The exclusion criteria were tuberculous meningitis and fungal meningitis. Duplicate isolates from the same child during hospitalization were not included in the present research. Locally trained researchers collected the data of the enrolled patients from the participating hospital computer data systems, which included the date of sample collection, type of specimen, hospital ward, basic information on patient demographics, causative organisms, antimicrobial susceptibility testing results, and final diagnosis.

Microbiological methods

All participating hospitals strictly complied with the standard operating procedures for CSF collection and culture. According to the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines, local experienced laboratory members of each hospital independently completed the isolation and identification of isolates, and antibiotic susceptibility testing was performed using semiautomated or automated systems. The CLSI guideline was used as the standard for the interpretation of the antimicrobial susceptibility test results [17]. Isolates showing intermediate resistance or resistance to the tested antimicrobial agents were categorized as resistant. The resistance of isolates to carbapenems referred to nonsusceptibility to one or more of the three carbapenems [ertapenem (ETP), imipenem (IMP) and meropenem (MEM)].

Statistical analysis

We calculated the counts and percentages for categorical variables and analyzed them using the chi-squared test. Continuous variables are presented as medians with the interquartile range. All of the data were collected, stored and sorted in a Microsoft Excel workbook. We performed data analyses using SPSS 22.0 (IBM Corp., New York, NY, USA) software.

Results

Demographic characteristics

From January 1, 2016 to December 3, 2018, 1161 patients (< 18 years old) with PBM were enrolled for screening. In accordance with the exclusion criteria, 1142 confirmed PBM patients were ultimately included. Less than half of the enrolled patients were boys (501/1142), and the median age was 3 months (range: 0 days to 17 years, 7 months). Up to 65.9% of patients were < 1 year old, 44.9% were < 3 months old, and a sharp decline in the percentage was observed with increasing age.

Pathogen composition

A total of 1193 bacterial pathogens were obtained from 1142 patients. Gram-positive organisms accounted for nearly 69.6% (830/1193) of the isolates, and 30.4% (363/1193) were gram-negative organisms. The three leading pathogens causing PBM were Staphylococcus epidermidis (S. epidermidis) (197/1193; 16.5%), E. coli (148/1193; 12.4%) and S. pneumoniae (127/1193; 10.6%), followed by Enterococcus faecium (E. faecium) (115/1193; 9.6%), Staphylococcus hominis (S. hominis) (85/1193; 7.1%), group B Streptococcus (GBS) (59/1193; 4.9%), Staphylococcus haemolyticus (S. haemolyticus) (42/1193; 3.5%), Klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumoniae) (40/1193; 3.4%), S. aureus (39/1193; 3.3%), and Acinetobacter baumannii (A. baumannii) (27/1193; 2.3%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Common bacterial pathogens isolated from PBM patients in China, 2016–2018

| Pathogen | 2016 N (%) |

2017 N (%) |

2018 N (%) |

Total N (%) |

Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gram-positive organisms | |||||

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | 72 (17.4) | 75 (16.7) | 50 (15.1) | 197 (16.5) | 1 |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 41 (9.9) | 44 (9.8) | 42 (12.7) | 127 (10.6) | 3 |

| Enterococcus faecium | 46 (11.1) | 32 (7.1) | 37 (11.1) | 115 (9.6) | 4 |

| Staphylococcus hominis | 15 (3.6) | 39 (8.7) | 31 (9.3) | 85 (7.1) | 5 |

| Group B Streptococcus | 20 (4.8) | 22 (4.9) | 17 (5.1) | 59 (4.9) | 6 |

| Staphylococcus haemolyticus | 20 (4.8) | 11 (2.5) | 11 (3.3) | 42 (3.5) | 7 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 16 (3.9) | 13 (2.9) | 10 (3.0) | 39 (3.3) | 9 |

| Other gram-positive organisms | 56 (13.6) | 72 (16.1) | 40 (12.1) | 168 (14.1) | |

| Gram-negative organisms | |||||

| Escherichia coli | 49 (11.9) | 64 (14.3) | 35 (10.5) | 148 (12.4) | 2 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 13 (3.1) | 10 (2.2) | 17 (5.1) | 40 (3.4) | 8 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | 10 (2.4) | 12 (2.7) | 5 (1.5) | 27 (2.3) | 10 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 6 (1.5) | 12 (2.7) | 4 (1.2) | 22 (1.8) | 11 |

| Other gram-negative organisms | 49 (11.9) | 42 (9.4) | 33 (9.9) | 124 (10.4) | |

| Total | 413 (34.6) | 448 (37.6) | 332 (27.8) | 1193 (100) | |

PBM, pediatric bacterial meningitis

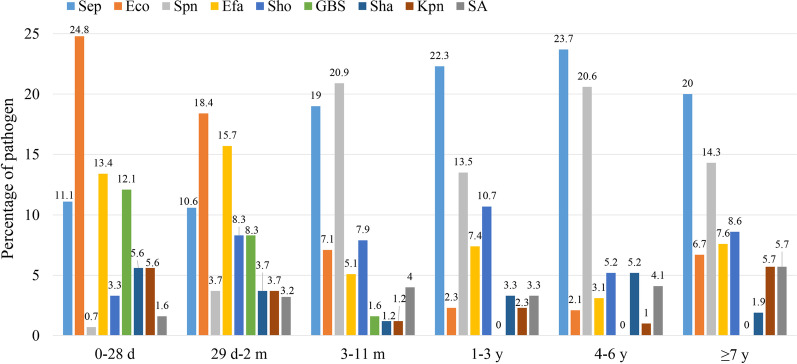

Distribution of major PBM pathogens according to age and clinical ward

The spectrum of pathogens causing PBM was highly variable in children of different ages (Fig. 2). In infants under 3 months of age, the top 3 pathogens were E. coli (116/523; 22.2%), E. faecium (75/523; 14.3%), and S. epidermidis (57/523; 10.9%). However, in children more than 3 months of age, the top 3 pathogens were S. epidermidis (140/670; 20.9%), S. pneumoniae (117/670; 17.5%), and S. hominis (57/670; 8.5%). As shown in Fig. 2, the other prevalent bacteria also varied by age group. Children less than 1 year old had the greatest abundance of pathogenic species, the leading pathogen among which was E. coli (134/776; 17.3%), followed by S. epidermidis (105/776; 13.5%) and E. faecium (88/776; 11.3%).

Fig. 2.

Distribution of major PBM pathogens by age in China, 2016–2018. PBM, pediatric bacterial meningitis; Sep, Staphylococcus epidermidis; Eco, Escherichia coli; Spn, Streptococcus pneumoniae; Efa, Enterococcus faecium; Sho, Staphylococcus hominis; GBS, group B Streptococcus; Sha, Staphylococcus haemolyticus; Kpn, Klebsiella pneumoniae; SA, Staphylococcus aureus

In terms of clinical ward distribution, these common pathogens were detected in the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU), surgical department and other departments (Additional file 1: Figure S1). S. epidermidis was detected more commonly in the surgical department (31.1%) than in the PICU (10.8%) and other departments (13.9%) (P < 0.001). However, E. coli, S. pneumoniae, E. faecium, and GBS were detected more frequently in the PICU and in the other departments than in the surgical department (all P < 0.05).

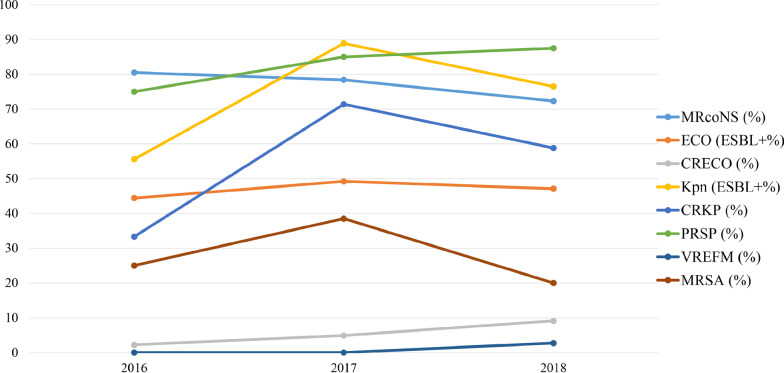

AMR patterns of the major gram-positive bacteria

As shown in Table 2, the three main species of coagulase-negative Staphylococcus (CoNS), namely, S. epidermidis, S. hominis and S. haemolyticus, were isolated from CSF cultures. The resistances of these isolates to penicillin (PEN) and erythromycin (ERY) were greater than 71.0%. Resistance to methicillin depended on oxacillin (OXA) resistance. Therefore, the overall detection rate of the methicillin-resistant CoNS (MRCoNS) isolates was approximately 80.0% and declined from 80.5% in 2016 to 72.3% in 2018 (Fig. 3). All of these three species were susceptible to linezolid (LNZ) (100%) and vancomycin (VAN) (100%). Over 65.0% of the isolates, except S. haemolyticus, were also susceptible to aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones, co-trimoxazole (SXT), rifampin (RIF) and tetracycline (TET). For S. pneumoniae isolates, resistance to fluoroquinolones, LNZ, or VAN was not detected in this study. The susceptibility to amoxicillin (AMX), cefotaxime (CTX) and ceftriaxone (CRO) was 74.8%, 59.0%, and 50.0%, respectively. However, over 84.0% of the S. pneumoniae isolates were resistant to ERY, clindamycin (CLI), SXT, and TET. The resistance of S. pneumoniae isolates to PEN was 82.8%, increasing from 75.0% in 2016 to 87.5% in 2018 (Fig. 3). More than 95.0% of E. faecium isolates showed susceptibility to VAN, LNZ, and tigecycline (TGC), but the resistance rates to other antibacterial drugs were over 62.9%.

Table 2.

Resistance rates (%) of major gram-positive bacteria of PBM patients in China, 2016–2018

| Antimicrobial agent | Sep A/B (%) |

Sho A/B (%) |

Sha A/B (%) |

Spn A/B (%) |

Efa A/B (%) |

GBS A/B (%) |

SA A/B (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxacillin | 132/165 (80.0) | 51/67 (76.1) | 31/36 (86.1) | – | – | – | 9/31 (29.0) |

| Penicillin G | 143/159 (89.9) | 58/66 (87.9) | 28/33 (84.8) | 92/116 (82.8) | 90/92 (97.8) | 1/58 (1.7) | 1/29 (96.6) |

| Amoxicillin | – | – | – | 26/103 (25.2) | – | – | – |

| Ampicillin | – | – | – | – | 106/111 (95.5) | 1/27 (3.7) | – |

| Cefotaxime | – | – | – | 48/117 (41.0) | – | – | – |

| Ceftriaxone | – | – | – | 17/34 (50.0) | – | – | – |

| Erythromycin | 134/160 (83.8) | 50/70 (71.4) | 35/36 (97.2) | 112/116 (96.6) | 107/109 (98.2) | 28/31 (90.3) | 22/31 (71.0) |

| Clindamycin | – | – | – | 60/65 (92.3) | – | 45/49 (91.8) | 9/25 (36.0) |

| Gentamicin | 44/163 (27.0) | 14/69 (20.3) | 23/36 (63.9) | – | – | – | 2/31 (6.5) |

| Ciprofloxacin | 46/165 (27.9) | 15/69 (21.7) | 30/36 (83.3) | – | 102/110 (92.7) | – | 1/32 (3.2) |

| Moxifloxacin | 29/94 (30.9) | 13/55 (23.6) | 10/17 (58.8) | 0/78 (0) | – | – | 0/19 (0) |

| Levofloxacin | 30/98 (30.6) | 8/58 (13.8) | 10/19 (52.6) | 0/118 (0) | 58/65 (89.2) | 28/59 (47.5) | 2/21 (9.5) |

| Rifampin | 27/163 (16.6) | 8/66 (12.1) | 12/35 (34.3) | – | – | – | 1/31 (3.2) |

| Nitrofurantoin | – | – | – | – | 66/105 (62.9) | – | 0/30 (0) |

| Co-trimoxazole | 57/164 (34.8) | 17/67 (25.4) | 30/36 (83.3) | 101/119 (84.9) | – | – | 8/31 (25.8) |

| Tetracycline | 45/165 (27.3) | 19/68 (27.9) | 14/37 (37.8) | 107/117 (91.5) | 83/111 (74.8) | 33/48 (68.8) | 7/32 (21.9) |

| Vancomycin | 0/164 (0) | 0/71 (0) | 0/37 (0) | 0/120 (0) | 1/111 (0.9) | 0/50 (0) | 0/31 (0) |

| Linezolid | 0/192 (0) | 0/82 (0) | 0/41 (0) | 0/94 (0) | 5/114 (4.4) | 0/56 (0) | 0/38 (0) |

| Tigecycline | – | – | – | – | 0/63 (0) | – | – |

PBM, pediatric bacterial meningitis; Sep, Staphylococcus epidermidis; Sho, Staphylococcus hominis; Sha, Staphylococcus haemolyticus; Spn, Streptococcus pneumoniae; Efa, Enterococcus faecium; GBS, group B Streptococcus; SA, Staphylococcus aureus

A/B (%), number resistant/number tested (percentage resistant)

A dash (–) indicates that antibiotics were not tested against the isolated pathogens

Fig. 3.

Trends of common multidrug resistant strains isolated from PBM patients in China, 2016–2018. PBM, pediatric bacterial meningitis; MRCoNS, methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative Staphylococcus; ESBL, extended-spectrum β-lactamase; CRECO, carbapenem-resistant Escherichia coli; CRKP, carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae; PRSP, penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae; VREFM, vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

AMR patterns of the major gram-negative bacteria

As shown in Table 3, more than 93.0% of the E. coli isolates were sensitive to cefoxitin (FOX), piperacillin/tazobactam (TZP), cefoperazone/sulbactam (CSL), amikacin (AMK) and carbapenems, and the resistance rates for ampicillin (AMP) and piperacillin (PIP) exceeded 82.0%. The sensitivities of E. coli to third-generation cephalosporins, aztreonam and fluoroquinolones were 47.6–73.6%, 65.3%, 44.3–46.4%, respectively. Moreover, the detection rate of ESBL-producing E. coli was stable and fluctuated between 44.4 and 49.2% in 2016–2018. The proportion of carbapenem-resistant E. coli (CRECO) isolates was 5.0%, increasing from 2.2% in 2016 to 9.1% in 2018 (Fig. 3). K. pneumoniae isolates exhibited susceptibility rates greater than 50.0% to aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones, TET, SXT, IMP, and ETP, but the resistance rates to other antibiotics were greater than 50.0%. The proportions of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae and carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae (CRKP) were 74.3% and 54.5%, respectively. The data from 2016 to 2018 demonstrated that ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae and CRKP showed an upward trend (Fig. 3).

Table 3.

Resistance rates (%) of major gram-negative bacteria of PBM patients in China, 2016–2018

| Antimicrobial agent | Eco A/B (%) |

Kpn A/B (%) |

Aba A/B (%) |

Pae A/B (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ampicillin | 105/125 (84.0) | 25/26 (96.2) | 14/18 (77.8) | 12/13 (92.3) |

| Piperacillin | 56/68 (82.4) | 11/14 (78.6) | 3/5 (60.0) | 5/13 (38.5) |

| Cefazolin | 52/104 (50.0) | 18/23 (78.3) | – | – |

| Cefuroxime | 11/21 (52.4) | 4/8 (50.0) | – | – |

| Cefoxitin | 0/30 (0) | 5/8 (62.5) | – | – |

| Ceftriaxone | 44/89 (49.4) | 10/15 (66.7) | 8/15 (53.3) | – |

| Cefotaxime | 30/61 (49.2) | 14/20 (70.0) | 5/8 (62.5) | – |

| Ceftazidime | 38/140 (26.4) | 20/32 (62.5) | 8/21 (38.1) | 5/16 (31.2) |

| Cefepime | 45/140 (32.1) | 17/32 (53.1) | 7/21 (33.3) | 3/17 (17.6) |

| Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid | – | – | 8/13 (61.5) | – |

| Ampicillin/Sulbactam | 58/102 (56.9) | 20/26 (76.9) | 5/15 (33.3) | 7/7 (100) |

| Piperacillin/tazobactam | 3/122 (2.5) | 20/30 (66.7) | 5/12 (41.7) | 4/10 (40.0) |

| Cefoperazone/sulbactam | 1/17 (5.9) | – | – | – |

| Tobramycin | 23/56 (41.1) | 2/8 (25.0) | 1/10 (10.0) | ¼ (25.0) |

| Gentamicin | 49/127 (38.6) | 13/30 (43.3) | 5/19 (41.7) | 2/13 (15.4) |

| Amikacin | 0/142 (0) | 11/31 (35.5) | 2/16 (12.5) | 1/16 (6.2) |

| Ciprofloxacin | 73/131 (55.7) | 12/29 (41.4) | 5/20 (25.0) | 1/13 (7.7) |

| Levofloxacin | 74/138 (53.6) | 12/32 (37.5) | 5/21 (23.8) | 3/16 (18.8) |

| Aztreonam | 43/124 (34.7) | 17/26 (65.4) | – | 2/4 (50.0) |

| Tetracycline | 60/76 (78.9) | 9/30 (30.0) | 5/9 (55.6) | – |

| Co-trimoxazole | 97/141 (68.8) | 5/34 (14.7) | 13/22 (59.1) | – |

| Meropenem | 6/88 (6.8) | 16/25 (64.0) | 6/11 (54.5) | 2/13 (15.4) |

| Ertapenem | 0/79 (0) | 1/12 (8.3) | – | – |

| Imipenem | 4/140 (2.9) | 5/22 (22.7) | 6/19 (31.6) | 6/16 (37.5) |

PBM, pediatric bacterial meningitis; Eco, Escherichia coli; Kpn, Klebsiella pneumoniae; Aba, Acinetobacter baumannii; Pae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa

A/B (%), number resistant/number tested (percentage resistant)

A dash (–) indicates that antibiotics were not tested against the isolated pathogens

For A. baumannii and P. aeruginosa isolates, the susceptibility rates of A. baumannii isolates to aminoglycosides and fluoroquinolones exceeded 55.0%. The susceptibility of isolates to cephalosporins and carbapenems ranged from 37.5 to 66.7% and 45.5 to 68.4%, respectively. The susceptibility rates of P. aeruginosa isolates to PIP, third-generation cephalosporins, TZP, aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones, and carbapenems were greater than 60.0%, but the resistance of isolates to AMP and ampicillin/sulbactam (SAM) exceeded 92.0%.

Discussion

PBM remains a serious threat to children’s health worldwide despite significant progress in the diagnosis and treatment of the disease. In the present study, S. epidermidis (16.5%) was the leading causative pathogen, followed by E. coli (12.4%) and S. pneumoniae (10.6%). Our findings differed from various reports worldwide, including reports from Britain [8], Africa [9, 10] and the USA [18], which showed that N. meningitidis, S. pneumoniae and H. influenzae were the predominant causative agents of PBM. However, the results were similar to those of a report from Southwest China [11]. The reasons for the discrepancies between studies are most likely differences in socioeconomic status and environmental factors among these regions. Therefore, timely summary and reporting of the features of the etiological agents of local PBM are urgently needed.

The distribution of PBM pathogens is highly variable in children of different ages [11–13]. We noticed that in infants aged under 3 months, the top 3 pathogens were E. coli (22.2%), E. faecium (14.3%), and S. epidermidis (10.9%). This result was similar to previous Chinese reports from Yunnan [11] and Shanghai [19]. However, it was not in accordance with several studies from the USA [20] and the UK and Ireland [21], which showed that GBS, E. coli and S. aureus were the predominant pathogens causing PBM in infants younger than 3 months. We also observed that in children older than 3 months of age, the predominant organisms causing PBM were S. epidermidis (20.9%), S. pneumoniae (17.5%) and S. hominis (8.5%). This finding was consistent with a previous study conducted in mainland China [11] but differed from data from England and Wales [8]. In addition, we also found that children younger than 1 year old had the highest abundance of pathogenic species, the leading pathogen among which was E. coli, followed by S. epidermidis and E. faecium. Therefore, the options of empiric antimicrobial agents for patients with PBM should be stratified by age to cover the most likely organisms.

The resistance rates of CoNS isolates to PEN and ERY were greater than 71.0% in the present study, which was similar to previous studies conducted in Brazil (100% and 86.2%, respectively) [22] and Beijing, China (94.9% and 92.4%, respectively) [23]. The overall resistance of the CoNS species to methicillin was nearly 80.0%, and the proportion of MRCoNS isolates declined slightly over the 3 years but remained very high (Fig. 3). These surveillance data were in line with a report from Beijing, China (93.6%) [23] but higher than the values reported in eastern Nepal (57.7%) [24] and Ethiopia (37.0%) [25]. Consistent with most previous studies [22, 24, 25], there were no LNZ- or VAN-resistant isolates found in our study. VAN remained the best option for the treatment of MRCoNS infections in patients with PBM. However, data from the UK and Ireland during 2013–2015 demonstrated that 0.2% of CoNS isolates were resistant to methicillin [26]. VAN-resistant CoNS exists in the clinic. Although no VAN-resistant CoNS isolates were found in these surveillance data, the emerging resistance of CoNS isolates to VAN may be a serious concern in PBM.

The high resistance of E. coli and K. pneumoniae to antibiotics is of critical concern [27–31]. The resistance rates of E. coli to CRO (49.4%) and CTX (49.2%) in the present study were quite close to those in previous Chinese studies [11, 13]. Our research also found that the proportion of ESBL-producing E. coli fluctuated between 44.4 and 49.2% in 2016–2018, which was in line with the proportions reported in Pakistan (40.0%) [27] and East Africa (42.0%) [28] but higher than the proportion in the USA (ranging from 10.0 to 15.0%) [29]. Notably, the proportion of CRECO was 5.0%, and this increased from 2.2% in 2016 to 9.1% in 2018. Data from the CHINET surveillance in 2005–2014 reported that IMP and MEM resistance rates of E. coli were approximately 1.0% and 2.2%, respectively [30]. A survey in the USA showed that the detected rates of CRECO increased from 2001 to 2010 [31]. However, the incidence of ESBL production in K. pneumoniae isolates and the resistance rates of K. pneumoniae to cephalosporins, aminoglycosides and carbapenems were higher than those of the E. coli isolates in our research. The prevalence of CRKP was 54.5% during the 3 years of this study. Consistent with this result, there were distinct upward trends of CRKP rates in 5 of the 24 participating countries in Europe from 2009 to 2012. Approximately 60.0% of K. pneumoniae isolates were resistant to carbapenems in Greece in 2012 [32]. Previous studies showed that carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae strains caused a mortality rate of approximately 26.0–44.0% [33], prolonged hospitalization time and increased economic burdens on patients [34]. Carbapenems were proposed as the optimal treatment for carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections. However, resistance to carbapenems has become an extreme challenge in the treatment of CRKP. Additional studies should focus on the mechanism of CRKP production in the future.

We also observed that the resistance rate of S. pneumoniae isolates to PEN was 82.8%, and the ratio increased from 75.0% in 2016 to 87.5% in 2018, which was lower than the values reported in Beijing (95.7%) [35] and Ethiopia (100%) [36] but was higher than the values from other studies, including those in Yunnan (31.2%) [11] and Iran (21.0%) [37]. S. pneumoniae had resistance rates of 41.0% to CTX and 50.0% to CRO in the present study. A finding from Beijing showed that nearly 14.0% and 11.3% of S. pneumoniae isolates were resistant to CTX and CRO, respectively, from 2014 to 2016 [13]. Jiang et al. [11] found that 16.7% of S. pneumoniae isolates were resistant to CRO in Yunnan during 2012–2015. The Ethiopian study indicated that the CTX and CRO resistance rates of S. pneumoniae isolates were 60.0% and 60.0%, respectively [36]. Various resistance levels were observed in different reports, and the high incidence of resistance in our study may be ascribed to the greater exposure to antibiotics in the clinic. Therefore, the use of antibiotics deserves serious consideration for the reduction in antibiotic resistance in China. Not surprisingly, there were no LNZ- or VAN-resistant S. pneumoniae isolates found in our study, which coincided with previous studies [11–13, 36, 37].

The present study was the first large-scale study to summarize the features of the etiological agents and AMR profiles of PBM in China. However, several limitations exist. First, due to the lack of patients’ detailed clinical data, we were unable to distinguish community- and hospital-acquired PBM or assess the epidemiological differences between them. We were also unable to identify a relationship between hospital-acquired PBM and pathogen distribution by clinical wards. Second, although all of the antimicrobial resistance results were interpreted based on the CLSI guideline, variations were inevitably found in the detection platforms, automated systems and technical skills of the participating hospitals, and these variations may have affected the results of the antimicrobial sensitivity tests to some degree.

Conclusions

The present study identified that S. epidermidis, E. coli and S. pneumoniae were the three leading bacterial pathogens associated with PBM in China from 2016 to 2018. It also revealed that the distribution of common PBM causative organisms varied by age. The resistance of CoNS to methicillin and the high incidence of ESBL production in E. coli and K. pneumoniae were concerning. CRKP poses a critical challenge for PBM treatment. Therefore, enhancing the surveillance and timely reporting of antibiotic resistance is urgently needed in China.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Distribution of major PBM pathogens according to clinical wards in China, 2016–2018. PBM: pediatric bacterial meningitis; Sep, Staphylococcus epidermidis; Eco, Escherichia coli; Spn, Streptococcus pneumoniae; Efa, Enterococcus faecium; Sho, Staphylococcus hominis; GBS, group B Streptococcus; Sha, Staphylococcus haemolyticus; Kpn, Klebsiella pneumoniae; SA, Staphylococcus aureus.

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Hong Zhao, the secretary of China Society of Infectious Diseases, for her help with the program initiation. We thank the members of the collaborative working group of pediatric subgroups of China Society of Infectious Diseases for their collecting the data for this study.

Abbreviations

- AMR

Antimicrobial resistance

- AMP

Ampicillin

- AMC

Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid

- ATM

Aztreonam

- AMK

Amikacin

- CZO

Cefazolin

- CXM

Cefuroxime

- CLSI

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute

- CAZ

Ceftazidime

- CTX

Cefotaxime

- CLI

Clindamycin

- CHL

Chloramphenicol

- CIP

Ciprofloxacin

- CoNS

Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus

- CRO

Ceftriaxone

- CSL

Cefoperazone/sulbactam

- CRE

Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae

- CRECO

Carbapenem-resistant Escherichia coli

- CRKP

Carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumonia

- ETP

Ertapenem

- ERY

Erythromycin

- ESBL

Extended-spectrum β-lactamase

- Efa

Enterococcus faecium

- Eco

Escherichia coli

- FEP

Cefepime

- GBS

Group B Streptococcus

- GEN

Gentamicin

- IMP

Imipenem

- Kpn

Klebsiella pneumonia

- LNZ

Linezolid

- LVX

Levofloxacin

- MRCoNS

Methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative Staphylococcus

- MXF

Moxifloxacin

- MEM

Meropenem

- MRSA

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

- OXA

Oxacillin

- RIF

Rifampin

- PEN

Penicillin G

- PIP

Piperacillin

- PBM

Pediatric bacterial meningitis

- PRSP

Penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumonia

- Sep

Staphylococcus epidermidis

- Spn

Streptococcus pneumonia

- Sho

Staphylococcus hominis

- Sha

Staphylococcus haemolyticus

- SA

Staphylococcus aureus

- TZP

Piperacillin/tazobactam

- TET

Tetracycline

- VAN

Vancomycin

- VREFM

Vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium

Authors’ contributions

MZ, YZ and CW conceived and designed the study. JL, QZ, YQ, CZ, YC, YZ, YX, MC, ZW, YC, RL, JT, QS, DL, SW, ZZ, CW, SZ, ZQ, XS, BM, CJ, HG and SL collected the raw data. XP performed the statistical calculations, interpreted the data, and drafted the initial manuscript. SL, YZ and CW modified the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from the Pediatric Clinical Research Center Foundation of Sichuan Province, China (No. 2017-46-4).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets in the present study are accessible from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of West China Second University Hospital and the Medical Ethical Committees of the participating hospitals. Because of the retrospective design of this research, informed consent was waived.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Xiaoshan Peng, Qingxiong Zhu and Jing Liu have contributed equally to this manuscript

Contributor Information

Shuangjie Li, Email: 2273858951@qq.com.

Yu Zhu, Email: zhuyu_wj@163.com.

Chaomin Wan, Email: wcm0220@126.com.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13756-021-00895-x.

References

- 1.Liu L, Oza S, Hogan D, Chu Y, Perin J, Zhu J, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of under-5 mortality in 2000–15: an updated systematic analysis with implications for the sustainable development goals. The Lancet. 2016;388(10063):3027–3035. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31593-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li Y, Yin Z, Shao Z, Li M, Liang X, Sandhu HS, et al. Population-based surveillance for bacterial meningitis in China, September 2006–December 2009. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20(1):61–69. doi: 10.3201/eid2001.120375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Svendsen MB, Ring Kofoed I, Nielsen H, Schonheyder HC, Bodilsen J. Neurological sequelae remain frequent after bacterial meningitis in children. Acta Paediatr. 2020;109(2):361–367. doi: 10.1111/apa.14942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thigpen MC, Whitney CG, Messonnier NE, Zell ER, Lynfield R, Hadler JL, et al. Bacterial meningitis in the United States, 1998–2007. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(21):2016–2025. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1005384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hsu MH, Hsu JF, Kuo HC, Lai MY, Chiang MC, Lin YJ, et al. Neurological complications in young infants with acute bacterial meningitis. Front Neurol. 2018;9:903. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lucas MJ, Brouwer MC, van de Beek D. Neurological sequelae of bacterial meningitis. J Infect. 2016;73(1):18–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2016.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khan FY, Abu-Khattab M, Almaslamani EA, Hassan AA, Mohamed SF, Elbuzdi AA, et al. Acute bacterial meningitis in Qatar: a hospital-based study from 2009 to 2013. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:2975610. doi: 10.1155/2017/2975610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okike IO, Ribeiro S, Ramsay ME, Heath PT, Sharland M, Ladhani SN. Trends in bacterial, mycobacterial, and fungal meningitis in England and Wales 2004–11: an observational study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(4):301–307. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70332-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsolenyanu E, Bancroft RE, Sesay AK, Senghore M, Fiawoo M, Akolly D, et al. Etiology of pediatric bacterial meningitis pre- and post-PCV13 introduction among children under 5 years old in Lomé, Togo. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;69(Suppl 2):S97–104. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agossou J, Ebruke C, Noudamadjo A, Adedemy JD, Denon EY, Bankole HS, et al. Declines in pediatric bacterial meningitis in the Republic of Benin following introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine: epidemiological and etiological findings, 2011–2016. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;69(Suppl 2):S140–S147. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang H, Su M, Kui L, Huang H, Qiu L, Li L, et al. Prevalence and antibiotic resistance profiles of cerebrospinal fluid pathogens in children with acute bacterial meningitis in Yunnan province, China, 2012–2015. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(6):e0180161. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0180161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo LY, Zhang ZX, Wang X, Zhang PP, Shi W, Yao KH, et al. Clinical and pathogenic analysis of 507 children with bacterial meningitis in Beijing, 2010–2014. Int J Infect Dis. 2016;50:38–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2016.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li C, Feng WY, Lin AW, Zheng G, Wang YC, Han YJ, et al. Clinical characteristics and etiology of bacterial meningitis in Chinese children >28 days of age, January 2014-December 2016: a multicenter retrospective study. Int J Infect Dis. 2018;74:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2018.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tamma PD, Robinson GL, Gerber JS, Newland JG, DeLisle CM, Zaoutis TE, Milstone AM. Pediatric antimicrobial susceptibility trends across the United States. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34(12):1244–1251. doi: 10.1086/673974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. Standard operating procedures for enhanced meningitis surveillance in Africa. 2009. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/1906/SOP_2009.pdf?. Accessed 13 March 2020.

- 16.Hossain B, Islam MS, Rahman A, Marzan M, Rafiqullah I, Connor NE, et al. Understanding bacterial isolates in blood culture and approaches used to define bacteria as contaminants: a literature review. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016;35(5 Suppl 1):S45–51. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute . Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, twenty-sixth informational supplement, M100–S26. Wayne, PA: Clin Lab Stand Institute; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castelblanco RL, Lee M, Hasbun R. Epidemiology of bacterial meningitis in the USA from 1997 to 2010: a population-based observational study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(9):813–819. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70805-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu M, Hu L, Huang H, Wang L, Tan J, Zhang Y, et al. Etiology and clinical features of full-term neonatal bacterial meningitis: a multicenter retrospective cohort study. Front Pediatr. 2019;7:31. doi: 10.3389/fped.2019.00031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woll C, Neuman MI, Pruitt CM, Wang ME, Shapiro ED, Shah SS, et al. Epidemiology and etiology of invasive bacterial infection in infants ≤60 days old treated in emergency departments. J Pediatr. 2018;200(210–217):e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.04.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Okike IO, Johnson AP, Henderson KL, Blackburn RM, Muller-Pebody B, Ladhani SN, et al. Incidence, etiology, and outcome of bacterial meningitis in infants aged <90 days in the United Kingdom and Republic of Ireland: prospective, enhanced, national population-based surveillance. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(10):e150–e157. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pedroso SHSP, Sandes SHC, Filho RAT, Nunes AC, Serufo JC, Farias LM, et al. Coagulase-negative staphylococci isolated from human bloodstream infections showed multidrug resistance profile. Microb Drug Resist. 2018;24(5):635–647. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2017.0309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cui J, Liang Z, Mo Z, Zhang J. The species distribution, antimicrobial resistance and risk factors for poor outcome of coagulase-negative staphylococci bacteraemia in China. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2019;8:65. doi: 10.1186/s13756-019-0523-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shrestha LB, Bhattarai NR, Khanal B. Antibiotic resistance and biofilm formation among coagulase-negative staphylococci isolated from clinical samples at a tertiary care hospital of eastern Nepal. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2017;6:89. doi: 10.1186/s13756-017-0251-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deyno S, Fekadu S, Seyfe S. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of coagulase negative staphylococci clinical isolates from Ethiopia: a meta-analysis. BMC Microbiol. 2018;18(1):43. doi: 10.1186/s12866-018-1188-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Henriksen AS, Smart J, Hamed K. Comparative activity of ceftobiprole against coagulase-negative staphylococci from the BSAC Bacteraemia Surveillance Programme, 2013–2015. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2018;37(9):1653–1659. doi: 10.1007/s10096-018-3295-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abrar S, Hussain S, Khan RA, Ul Ain N, Haider H, Riaz S. Prevalence of extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae: first systematic meta-analysis report from Pakistan. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2018;7:26. doi: 10.1186/s13756-018-0309-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sonda T, Kumburu H, van Zwetselaar M, Alifrangis M, Lund O, Kibiki G, et al. Meta-analysis of proportion estimates of Extended-Spectrum-Beta-Lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in East Africa hospitals. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2016;5:18. doi: 10.1186/s13756-016-0117-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leistner R, Schroder C, Geffers C, Breier AC, Gastmeier P, Behnke M. Regional distribution of nosocomial infections due to ESBL-positive Enterobacteriaceae in Germany: data from the German National Reference Center for the Surveillance of Nosocomial Infections (KISS) Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21(3):255.e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2014.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu FP, Guo Y, Zhu DM, Wang F, Jiang XF, Xu YC, et al. Resistance trends among clinical isolates in China reported from CHINET surveillance of bacterial resistance, 2005–2014. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;22(Suppl 1):S9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.CDC Vital signs: carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. MMWR. 2013;62(9):165–170. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Canton R, Akova M, Carmeli Y, Giske CG, Glupczynski Y, Gniadkowski M, et al. Rapid evolution and spread of carbapenemases among Enterobacteriaceae in Europe. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(5):413–431. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Falagas ME, Tansarli GS, Karageorgopoulos DE, Vardakas KZ. Deaths attributable to carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20(7):1170–1175. doi: 10.3201/eid2007.121004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bartsch SM, McKinnell JA, Mueller LE, Miller LG, Gohil SK, Huang SS, et al. Potential economic burden of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) in the United States. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2017;23(1):48.e9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2016.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shi W, Li J, Dong F, Qian S, Liu G, Xu B, et al. Serotype distribution, antibiotic resistance pattern, and multilocus sequence types of invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates in two tertiary pediatric hospitals in Beijing prior to PCV13 availability. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2019;18(1):89–94. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2019.1557523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Assegu Fenta D, Lemma K, Tadele H, Tadesse BT, Derese B. Antimicrobial sensitivity profile and bacterial isolates among suspected pyogenic meningitis patients attending at Hawassa University Hospital: cross-sectional study. BMC Microbiol. 2020;20(1):125. doi: 10.1186/s12866-020-01808-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Houri H, Tabatabaei SR, Saee Y, Fallah F, Rahbar M, Karimi A. Distribution of capsular types and drug resistance patterns of invasive pediatric Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates in Teheran, Iran. Int J Infect Dis. 2017;57:21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2017.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Distribution of major PBM pathogens according to clinical wards in China, 2016–2018. PBM: pediatric bacterial meningitis; Sep, Staphylococcus epidermidis; Eco, Escherichia coli; Spn, Streptococcus pneumoniae; Efa, Enterococcus faecium; Sho, Staphylococcus hominis; GBS, group B Streptococcus; Sha, Staphylococcus haemolyticus; Kpn, Klebsiella pneumoniae; SA, Staphylococcus aureus.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets in the present study are accessible from the corresponding author on reasonable request.