Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most common cancers worldwide and represents a classic paradigm of inflammation-related cancer. Various inflammation-related risk factors jointly contribute to the development of chronic inflammation in the liver. Chronic inflammation, in turn, leads to continuous cycles of destruction-regeneration in the liver, contributing to HCC development and progression. Tumor associated macrophages are abundant in the tumor microenvironment of HCC, promoting chronic inflammation and HCC progression. Hence, better understanding of the mechanism by which tumor associated macrophages contribute to the pathogenesis of HCC would allow for the development of novel macrophage-targeting immunotherapies. This review summarizes the current knowledge regarding the mechanisms by which macrophages promote HCC development and progression, as well as information from ongoing therapies and clinical trials assessing the efficacy of macrophage-modulating therapies in HCC patients.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma, Tumor associated macrophage, Tumor microenvironment, Immunotherapy

1. Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most common cancers worldwide 1. Despite advances in surgical resection, adjuvant therapy, and liver transplantation during the past decades, the survival rate of HCC patients remains unsatisfactory, with a 5-year survival rate of approximately 20%. The poor prognosis of HCC is primarily due to its late diagnosis, as well as its high risk of potential recurrence and metastasis 2,3. Other non-surgical interventions, including transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) and radiofrequency ablation (RFA), can provide disease control only for advanced-stage patients 4. Systemic administration of sorafenib exerts a weak therapeutic effect in patients with metastatic HCC 5. Therefore, the development of novel therapeutics with mechanisms different from those of the currently available treatments is crucial to improve the prognosis of HCC patients.

Emerging immunotherapies, including immune checkpoint inhibitors targeting programmed death-1 (PD-1) and cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA4), have revolutionized the therapeutic landscape for various solid tumors 6-9. HCC is a typical example of inflammation-related cancer. Primary risk factors for HCC include exposure to aflatoxins, alcohol intoxication, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease caused by obesity and metabolic syndrome, as well as viral infections such as hepatitis B and C viruses. These factors jointly contribute to hepatic inflammation, fibrosis, and cirrhosis, which are observed in 80% of HCC patients 10-12. In the inflammatory tumor microenvironment (TME) of HCC, various non-malignant cells and extracellular matrix components play pivotal roles in cancer development and progression, as well as in resistance to traditional antitumor therapies 13,14.

TME is characterized by infiltration of various non-malignant cells, including stromal cells, fibroblasts, macrophages, endothelial cells, immune cells, and circulating platelets. Cytokines secreted by these cells and the extracellular matrix are also important components of the TME 15-17. Within the TME, non-malignant cells play crucial roles in promoting cancer cell proliferation, invasion, and metastasis. Among them, immune cells coexist and interact with each other initiating complex pathways and ultimately resulting in tumor progression and drug resistance. Thus, the combination of immunological interventions with conventional therapies might be more effective than monotherapies 18,19. Macrophages are major components of the TME; several tumor-promoting roles have been attributed to these tumor associated macrophages (TAMs) 20-23. TAMs have been implicated in immune suppression, cancer invasion and metastasis, angiogenesis, maintenance of cancer cell stemness, and drug resistance. Furthermore, high levels of TAMs have been associated with poor prognosis in patients with HCC 24-26. Therefore, a better understanding of the mechanisms underlying the function of TAMs is necessary for the development of novel TAM-targeting immunological interventions, which may provide promising therapeutic approaches for HCC patients 27-29.

This review summarizes the current knowledge regarding the role of macrophages in the pathogenesis of HCC and provides information regarding the currently available immunotherapies as well as ongoing clinical trials assessing the efficacy of macrophage-modulating therapies in HCC patients.

1.1. Liver macrophages in homostasis

As one of the main types of innate immune cells, macrophages serve as the first line of defense against pathogenic insults to the body. Macrophages can be found in all tissues and exhibit exceptionally high plasticity and functional diversity 30-32. Macrophages are involved in phagocytosis, antigen processing and presentation, and orchestration of the immune system by the release of multiple cytokines, regulating inflammation initiation, progression, and resolution 33,34.

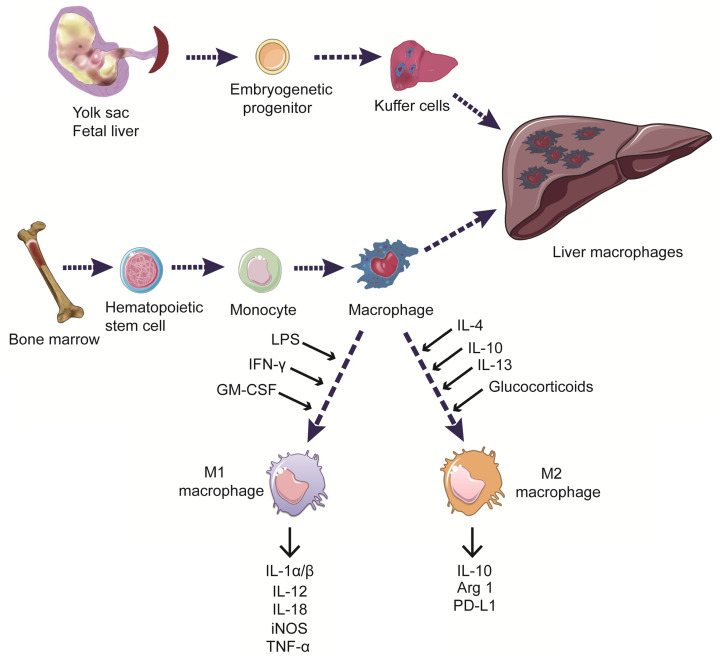

The liver harbours the main part body macrophages and is supervised by myeloid cells including blood monocytes, which scan the liver vasculature and eventually infiltrate into the liver. Under homeostasis conditions, monocyte-derived cells can develop into liver dendritic cells (DCs) or monocyte-derived macrophages (MoMFs), the latter do not contribute to the pool of resident macrophages, termed Kuffer cells. Kuffer cells originate from yolk sac-derived precursors during embryogenesis, forming a self-renewing pool of resident macrophages in the liver and playing essential roles in sustaining hepatic and systematic homeostasis 35. When activated by danger signals, Kuffer cells can promote chronic liver inflammation by inducing the recruitment of immune cells to the liver, including monocytes, which subsequently derived DCs and MoMFs 36. To date, no specific markers were proved to distinguish human Kuffer cells from monocyte-derived cells (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Origin and classification of liver macrophages. Liver macrophages, consisting of Kuffer cells and monocyte-derived macrophages, play essential roles in sustaining hepatic and systematic homeostasis. Myeloid cells including blood monocytes, scan the liver vasculature and eventually derive macrophages infiltrating into the liver. Kuffer cells are resident phagocytes originating from yolk sac-derived precursors during embryogenesis. Macrophages can be classified into two distinct functional phenotypes according to their responses to different environmental stimuli in vitro. M1 macrophages are induced by LPS, IFN-γ, and GM-CSF. They secrete the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1α/β, IL-12, IL-18, iNOS, and TNF-α, as well as promoting the function of effector T cells. M2 macrophages are induced by IL-4, IL-10, IL-13, and glucocorticoids, and exert anti-inflammatory and immune-regulatory effects by expressing IL-10, Arg1, and PD-L1.

Additionally, according to their inflammatory states in response to different environmental stimuli, macrophages can be classified into two main subtypes: the classically activated macrophages (M1 macrophages) and alternatively activated macrophages (M2 macrophages). These two distinct functional phenotypes have contradicting roles in regulating inflammation progression in vitro 37,38. M1 macrophages are primarily induced by microbial components, such as lipopolysaccharides (LPS), or by pro-inflammatory cytokines, including interferon-γ (IFN-γ), tumor necrosis factor (TNF), and toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands. M1 macrophages exert pro-inflammatory functions by releasing nitric oxide (NO), reactive oxygen species (ROS), and the pro-inflammatory cytokines interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, IL-12, TNF-α, CXCL5, and CXCL8-10, involving in antigen processing and presentation, promoting the function of effector T cells 39,40. Polarization to the M2 phenotype is induced by IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13, as well as by glucocorticoids. M2 macrophages exert immunosuppressive functions and promote tissue repair by secreting IL-10 and other immunosuppressive cytokines 41,42 (Figure 1). However, there are almost none of the purely M1 or M2 macrophages in scenarios like tumor models or autoimmune disease in vivo. Thus, more research for a better understanding of the relationship between mechanisms and the subphenotypes of macrophages is urgently needed in developing novel therapies.

2. Liver macrophages in pathogenesis of HCC

Increased infiltration of macrophages is a common characteristic of various solid tumors. Concurrently, HCC represents a classic paradigm of inflammation-related cancer. Various inflammation-related risk factors jointly contribute to the development of chronic inflammation in the liver. Chronic inflammation, in turn, leads to continuous cycles of destruction-regeneration in the liver, contributing to fibrosis and cirrhosis, and eventually development and progression of HCC. Liver macrophages are regulators of this process 43,44. An immunogenic analysis using patient data from The Cancer Genome Atlas indicated that TAMs are abundant in HCC, which are mostly polarized towards the M2 phenotype. CD68 is commonly used as an indicator of liver TAMs, and the expression levels of CD86 (M1), CD163 (M2), and CD206 (M2) are widely accepted to differentiate between M1 and M2 macrophages in vitro 45. Low levels of CD86+ M1 macrophages and high levels of CD206+ M2 macrophages have been associated with an aggressive phenotype in HCC, suggesting that conjoint analysis of CD86 and CD206 expression may provide a prognostic tool for HCC 46. Numerous chemokines (CCL2, CCL5, CCL15, CCL20), cytokines (such as CSF-1) and other products of the complement cascade were demonstrated to participate in the mechanism of monocyte-derived macrophages recruitment and migration 23,47-49. Additionally, several researches recently provide evidence in the transition from Kuffer cells to TAM pool by triggering Her2/Neu pathway 50,51. Other factors, including mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), osteopontin (OPN), micro RNAs (miRNAs), circular RNAs (circRNAs) and HCC cell-derived exosomes were also reported to play important roles in TAM recruitment 52-55. TAMs induce the expression of ST18 in epithelial cells, promoting mutual epithelial cell-macrophage dependency in HCC 56. TAMs also release various immunosuppressive chemokines and cytokines, including IL-10, transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), which exert immunoregulatory roles. Furthermore, TAMs have been shown to recruit regulatory T cells (Tregs) to the tumor; the recruitment of Tregs impairs the activation and function of effector T cells 57.

Recent studies have indicated that insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-1 and IGF-2 remodel macrophages during their maturation 58. Tricarboxylic acid cycle metabolism plays a key role in the epigenetic remodeling of macrophages 59. In mouse models of glioblastoma, IGF-1 enhanced PI3K-mediated tumor cell proliferation in a macrophage-dependent manner 60. Nevertheless, the molecular mechanisms underlying the IGF-mediated reprogramming of macrophages in human HCC require further investigation.

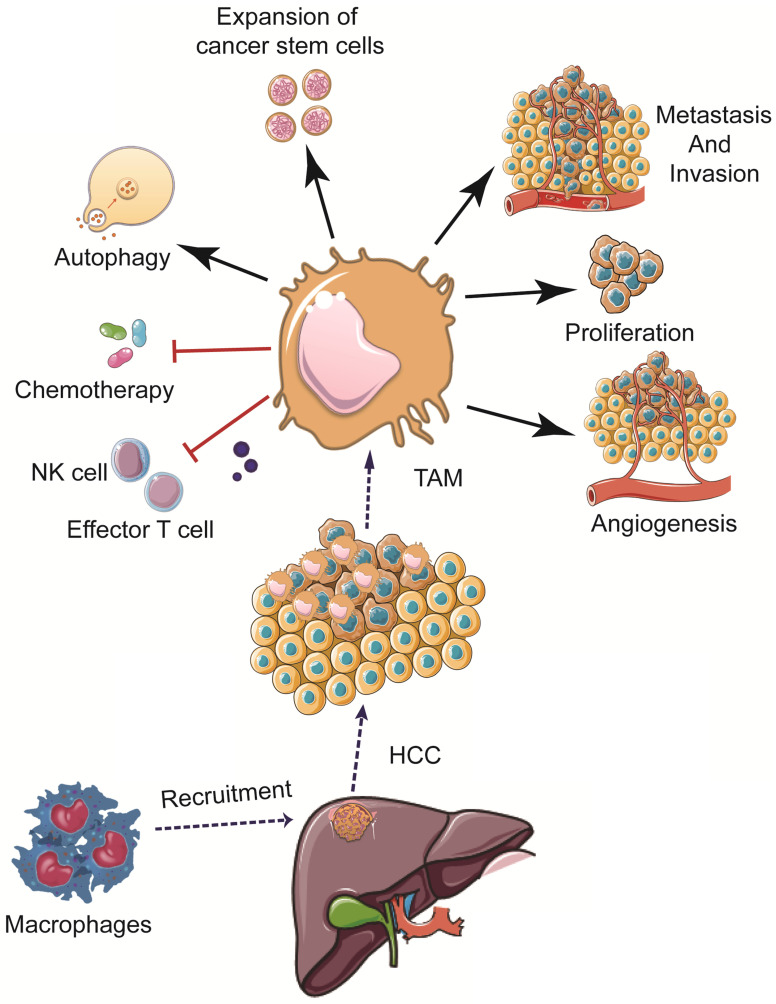

Increased levels of TAMs have been shown to promote angiogenesis, cancer cell proliferation, invasion, and metastasis; high levels of TAMs have also been associated with a poor prognosis in HCC patients 61,62. The mechanisms of TAMs in the pathogenesis of HCC are summarized hereinbelow (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Effects of TAMs in the pathogenesis of HCC. TAM can promote HCC development and progression via multiple mechanisms, including promoting cancer cell proliferation, stemness, invasion, and metastasis, modulating angiogenesis, autophagy, drug resistance, as well as weakening the functions of NK cells and effector T cells, etc.

2.1. TAMs promote cancer cell proliferation, invasion, and metastasis in HCC

M2 macrophages have been shown to play an essential role in promoting cancer cell migration in HCC via the TLR4/STAT3 signaling pathway 63. Aberrant activation of the NTS/IL-8 pathway was reported to play a pro-tumorigenic role in the inflammatory microenvironment of HCC, by augmenting M2 macrophage-mediated EMT of cancer cells 64. CXCL8 produced by activated macrophages promotes HCC progression and metastasis 65. TIM-3 augments the TGF-β mediated polarization of macrophages toward an M2 phenotype, contributing to the poor prognosis of HCC 66. IL-6 derived by TAMs has been suggested to promote cancer cell invasion, and metastasis in HCC 67. SPON2 has been reported to promote the infiltration of M1 macrophages in HCC and suppress metastasis via the integrin/RhoGTPase/Hippo pathway 68. MicroRNAs, as a class of small non-coding RNAs, regulating gene expression at the post-transcriptional level, were reported to mediate tumor-promoting effects of TAMs recently. Downregulation of miR-28-5p expression in HCC samples has been inversely associated with the levels of TAM infiltration and IL-34 expression; IL-34 further promotes TAM infiltration, resulting in a miR-28-5p-IL-34 feedback loop, which plays an important role in HCC metastasis 69. MiR-98 has been shown to suppress cancer cell invasion in HCC by promoting macrophage polarization from the M2 to M1 phenotype 70. MiR-146a-5p, enriched in HCC cell-derived exosomes, was demonstrated to promote infiltration of M2 TAMs, which results in T cell exhaustion and HCC progression 54. Coincidentally, long non-coding RNAs also play an important role in the tumor-promoting effects of macrophages in HCC. Long non-coding RNA COX-2 suppresses immune evasion and metastasis in HCC by inhibiting macrophage polarization into an M2 phenotype 71. Recently, using single-cell RNA sequencing, RIPK1 was demonstrated to induce CCR2+ macrophages infiltration, as well as promoting liver fibrosis and hepatocarcinogenesis 72. Wu et al. recently manifested that CD11b/CD18, as well as integrin, which derived from M2 macrophage exosomes, had the potency to boost the migratory potential of HCC cells 73. Additionally, HCC cell-derived Wnt ligands stimulate M2 polarization of TAMs, which reversely result in tumor growth, metastasis and immunosuppression in HCC 74. Heat shock transcription factor 1 (HSF1) was demonstrated as a vital mediator in metabolic alteration of HCC cells in cross-talking with TAMs 75.

Hypoxia has been demonstrated to mediate the effects of macrophages, playing an important role in HCC, among other solid tumors. Hypoxia-induced EMT increased the expression of CCL20 in hepatoma cells, leading to indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) upregulation in monocytes-derived macrophages. Macrophages that are derived from IDO+ monocytes counteract effector T cells and promote tolerance to tumor antigens 76. Zhang et al. found that the necrotic debris from cancer cells in the hypoxic and inflammatory HCC microenvironment enhanced the release of IL-1β by M2 macrophages. IL-1β, in turn, unregulated the expression of HIF-1α in HCC cells in a cyclooxygenase-2-dependent manner, constituting a positive feedback loop promoting EMT in HCC cells 77. Wu et al. confirmed that TREM-1+ TAMs promote the recruitment of CCR6+Foxp3+ Tregs via the ERK/NF-κB pathway, conferring resistance to programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) treatment in HCC 78.

2.2. TAMs promote angiogenesis in HCC

TAMs have been demonstrated to produce numerous angiogenic factors, including vascular endothelial growth factor, platelet-derived growth factor, and several matrix metalloproteinases 79. The CCR2+ TAM subset was reported to be highly enriched in highly vascularized HCC tumors and was suggested to drive angiogenesis and tumor vascularization in fibrotic livers 80. A recent study showed that HCC patients with high serum levels of IL-23 derived from macrophages had tumors with enhanced vascularization 81. CXCR4, expressing on endothelial cells, which is upregulated by inflammatory cytokines derived from TAMs via ERK pathway activation, was identified as a novel vascular marker in HCC tissues 82. The combination of sorafenib and zoledronic acid (ZA) has been shown to exert synergistic antitumor effects mediated by downregulation of CXCR4 expression 83.

2.3. TAMs promote cancer cell stemness in HCC

Previous studies have suggested that the high heterogeneity and malignancy of HCC are partly attributed to cancer stem cells (CSCs), which promote tumor recurrence, metastasis, and development of resistance to therapies 84. Numerous cell surface proteins, including EPCAM, CD133, CD124, CD44, and CD90, have been identified as CSC markers 85,86. TAMs have been suggested to promote CSC-like properties via various signaling pathways. Importantly, TAMs facilitated the expansion of stem cells via the IL-6/STAT3 pathway in HCC patients 87. Fan et al. confirmed that TAMs promote CSC properties via TGF-β signaling pathway 88. TNF-α promotes EMT and cell stemness in HCC by activating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, which can be partially reversed by the Wnt/β-catenin inhibitor ICG-001 89. In addition, exosomes from TAMs promote cancer cell proliferation and stem cell properties in HCC. For instance, a low level of miR-125a/b in exosomes from TAMs was shown to inhibit CSCs by targeting CD90 in HCC 90.

2.4. TAMs promote autophagy in HCC

Mounting evidence suggests the importance of autophagy in the regulation of the function of TAMs and antitumor immunity 91. A recent study showed that autophagy-deficient Kupffer cells promoted liver fibrosis, inflammation, and hepatocarcinogenesis via the mitochondrial reactive oxygen species/NF-κB/IL-1α/β signaling axis 92. Chang et al. demonstrated that TLR2 related ligands triggered NFKB RELA cytoplasmic ubiquitination and led to its degradation by SQSTM1/p62-mediated autophagy, promoting M2 polarization in macrophages and immunosuppression in HCC 93. TLR2 deficiency also resulted in a decrease in macrophage infiltration and inhibition of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase/NF-κB signaling. Subsequently, TLR2 deficiency led to decreased expression levels of IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-1α/β, as well as increased cell proliferation and suppressed autophagy and apoptosis in mouse liver cells 94. Tan et al. revealed that the natural compound baicalin inhibited HCC development and progression by TAM repolarization towards the M1 phenotype via autophagy-associated activation of RelB/p52 95. Fu et al. suggested that TAMs induce autophagy in HCC cells, which might contribute to oxaliplatin resistance 24. These findings reveal new roles of TAMs and autophagy in HCC, which could provide new opportunities for the development of more efficient therapies.

2.5. TAMs modulate therapeutic resistance in HCC

The orally administrated multikinase inhibitor sorafenib shows limited efficacy in HCC patients due to the development of intolerance and resistance 96. TAM has been demonstrated to induce immunosuppression and weaken the efficacy of sorafenib in HCC 97. Zhou et al. demonstrated that tumor-associated neutrophils enhance the recruitment of Tregs and macrophages to the TME in HCC patients, promoting tumor progression and resistance to sorafenib 98. Oxaliplatin-based chemotherapies are widely used in patients with advanced HCC. It has been reported that TAMs are important drivers of resistance to oxaliplatin by trigging autophagy and apoptosis evasion in HCC cells 24. The density of TAMs in HCC samples has been associated with the efficiency of transarterial chemoembolization in HCC 24. Moreover, M2 macrophages have been reported to promote the development of resistance to sorafenib in HCC by secreting hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) 25. A recent study showed that sorafenib induces pyroptosis in macrophages and facilitates NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity in HCC, highlighting the importance of TAMs as a therapeutic target in HCC 99.

3. Macrophage-targeting therapies in HCC

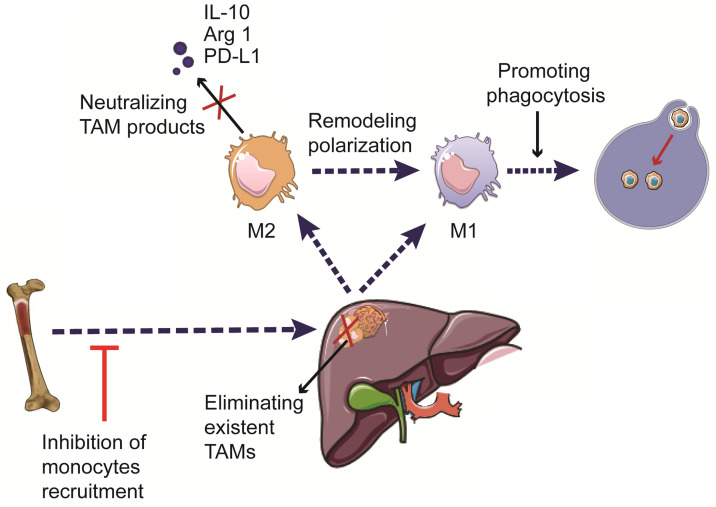

Increasing evidence suggests the critical roles of TAMs in HCC development and progression. Hence, immunotherapies targeting TAMs have emerged as a promising approach to treat patients with HCC. The current therapeutic strategies targeting TAMs include phagocytosis-promoting therapies, inhibition of monocyte recruitment, elimination of pre-existing TAMs in the tumor tissue, remodeling TAM polarization, and neutralizing pro-tumorigenic factors secreted by TAMs 100,101 (Figure 3). The currently available immunotherapies, as well as ongoing clinical trials involving the use of TAM-targeting immunotherapies in HCC, are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Figure 3.

Therapeutic strategies targeting TAMs in HCC. The development of TAM-targeting immunotherapeutic strategies includes induction of phagocytosis, inhibition of monocyte recruitment, elimination of pre-existing TAMs, reprogramming of macrophage polarization, and neutralization of the pro-tumorigenic factors secreted by TAMs.

Table 1.

Preclinical agents targeting TAMs for HCC treatment

| Author | Agent | Target | Mechanism of action | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lu et al.107 | Anti-CD47mAbs | CD47 | Promote phagocytosis of macrophages | Suppress tumor growth and enhance the effect of chemotherapy treatment |

| Xiao et al.108 | B6H12 | CD47 | Promote phagocytosis of macrophages | Suppress tumor growth and enhance the effect of chemotherapy treatment |

| Li et al.110 | RDC018 | CCR2 | Inhibiting monocytes recruitment | Inhibit HCC growth and metastasis, reduce recurrence |

| Yao et al.97 | 747 | CCR2 | Inhibiting monocytes recruitment | Anti-cancer properties and enhance the efficacy of sorafenib |

| Zhu et al.113 | GC33 | Glypican-3 | Eliminating existent TAMs | Japanese Phase II study for advanced HCC |

| Ikeda et al.114 | GC33 | Glypican-3 | Eliminating existent TAMs | Clinical trail for advanced HCC patients |

| Zhang et al.83 | Clodrolip or Zoledronic acid | - | Eliminating existent TAMs | Enhance the efficacy of sorafenib in mouse models |

| Zhou et al.117 | Zoledronic acid | - | Eliminating existent TAMs | Enhance the efficacy of TACE in HCC mouse models |

| Tan et al.95 | Baicalin | - | Re-educating TAMs | Suppress tumor growth |

| Sun et al.119 | 8-Bromo-7-methoxychrysin | CD163 | Re-educating TAMs | Impede interaction between HCC stem cells and TAMs |

| Ao et al.120 | PLX3397 | CSF1R | Re-educating TAMs | Suppress tumor growth |

| Wan et al.87 | Tocilizumab | IL-6 receptor | Neutralizing productsof TAMs | Inhibit TAMs mediated stimulation of HCC stem cells |

Table 2.

Clinical trials targeting TAMs for HCC treatment

| Target | Agent | Mechanism | Phase | Clinical trial number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glypican-3 | GC33 | Glypican-3 antagonist (eliminating existent macrophages) | Phase 2 | NCT01507168 |

| CCR2/5 | Nivolumab +BMS-813160 /+BMS-986253 |

CCR2/5 antagonist (inhibits monocyte/macrophage infiltration) | Phase 2 | NCT04123379 |

| CSF1R | Chiauranib | Multi-target inhibitor that suppresses angiogenesis-related kinases and CSF1R; decreases the macrophage differentiation. | Phase 1 | NCT03245190 |

3.1. Phagocytosis-promoting therapies

CD47, mostly known as a receptor for thrombospondin in human myeloid and endothelial cells, has recently been demonstrated to protect host cells from macrophage-mediated destruction by binding to SIRP1α (SHPS-1) expressed on the surface of macrophages 102. Neutralizing antibodies against CD47 can enhance macrophage-mediated phagocytosis and activate effector T cells 103,104. IL-6 secretion by TAMs has been reported to upregulate CD47 expression in HCC cells via the STAT3 signaling pathway. CD47 upregulation has been associated with poor overall survival and recurrence-free survival in HCC patients. Blockage of CD47 enhanced TAM-mediated phagocytosis in the presence of chemotherapeutic agents 105. Yang et al. demonstrated that the HDAC6/let-7i-5p/TSP1 axis reduced the neoplastic and antiphagocytic properties of HCC cells by targeting CD47, providing a promising therapeutic target for the treatment of HCC 106. Additionally, the anti-CD47 monoclonal antibody (B6H12) suppressed tumor growth and augmented the efficacy of chemotherapy in HCC 107,108.

3.2. Therapies inhibiting the recruitment of macrophages

The inhibition of monocyte recruitment in HCC tissues has recently emerged as a promising approach to decrease the levels of TAMs. Aberrant expression of miR-26a has been shown to suppress HCC growth and macrophage infiltration by targeting macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) in a PI3K/AKT pathway-dependent mechanism 109. CCL2 expression has been reported to be elevated in HCC tissues and has been suggested as a novel prognostic factor for HCC. Kuffer cells, as the primary source of CCL2, are essential for the recruitment and education of monocyte-derived macrophages 36. The CCL2/CCR2 signaling has recently emerged as a target to suppress the recruitment of monocytes in tumors. Blockade of CCL2/CCR2 signaling pathway suppressed monocyte recruitment and the polarization of infiltrated macrophages towards the M2 phenotype, suppressing tumor growth in a T cell-dependent manner, in a mouse liver cancer model 110. The CCR2 antagonist 747 has been shown to exert potent antitumor effects and enhance the efficacy of sorafenib by combating TAM-mediated immunosuppression and increasing the number of CD8+ T cells in an HCC mouse model 97. Glypican-3 has been reported to be overexpressed in HCC and has been implicated in the recruitment of macrophages by binding to CCL3 and CCL5 111,112. Antibodies targeting glypican-3 have demonstrated promising efficacy in several clinical trials by inhibiting the recruitment of M2 macrophages in the TME 113. For example, the humanized antibody GC33 was well tolerated in advanced HCC patients in a clinical trial conducted in Japan 114.

3.3. Therapies eliminating pre-existing TAMs

The combination of TAM-targeting therapies with traditional therapies in HCC has been investigated 21. For instance, clodrolip or ZA treatment augmented the antitumor effects of sorafenib, by suppressing tumor growth, angiogenesis, and lung metastasis in HCC xenograft models 83. The use of ZA may remodel the intratumoral pool of macrophages by trigging apoptosis in specific TAM populations 115,116. In addition, ZA treatment has been shown to enhance the effects of transarterial chemoembolization by suppressing the infiltration of TAMs in HCC 117.

3.4. Reprogramming TAM polarization

Numerous tumor-derived factors are involved in TAM phenotype shift, including the aforementioned TGF-β, miR-98, and long non-coding RNA COX-2 66,70,71. Recently, it is reported that HCC-derived exosomes could remodel macrophages by activating NF-κB signaling and result in M2 polarized TAMs 54. Receptor-interacting protein kinase 3 (RIPK3) is downregulated in HCC-associated macrophages, and RIPK3 deficiency induced fatty acid oxidation (FAO), which induced M2 polarized TAMs. Hence, RIPK3 upregulation or FAO blockade reversed the immunosuppressive activity of TAMs and dampened HCC tumorigenesis 118. As mentioned previously, TAMs with the M1 phenotype promote tumor cell elimination and degradation. Hence, re-educating TAMs to switch from the M2 to M1 phenotype has been suggested as a therapeutic approach for HCC. Baicalin administration suppressed tumor growth in an orthotopic HCC mouse model by inducing TAM reprogramming towards the M1 phenotype and subsequent secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines 95. Furthermore, 8-bromo-7-methoxychrysin (BrMC) was shown to attenuate the effects of M2 macrophages by influencing the profile of secreted cytokines and reversing M2 polarization of TAMs 119. The use of the competitive CSF-1R inhibitor PLX3397 suppressed tumor growth in an HCC mouse model by shifting the polarization of TAMs towards the M1 phenotype 120.

Conclusions

Macrophages play essential roles in orchestrating immune responses; nevertheless, dysregulation of their function has been implicated in HCC, among other solid malignancies. Macrophages are abundant in the TME in HCC, exhibiting double-edged roles in controlling tumorigenesis by modulating immune responses. Importantly, TAMs have been shown to enhance HCC development and progression by promoting immune suppression, cancer cell proliferation, invasion, metastasis, and maintenance of cancer cell stemness. Consequently, a better understanding of the mechanisms by which TAMs regulate HCC malignancy would allow for the development of novel and more effective TAM-targeting HCC therapies. Adjuvant treatment with agents targeting TAMs following conventional hepatectomy or liver transplantation may improve the clinical benefit of the therapies currently used for HCC patients.

Acknowledgments

The English in this document has been checked by at least two professional editors, both native speakers of English. For a certificate, please see: http://www.textcheck.com/certificate/C3nkIQ.

Funding

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.81572307 and 81773096).

Authors' Contributions

Yu Huang and Wenhao Ge contributed eqaully to this work. Yu Huang and Wenhao Ge concepted and wrote the manuscript; Jiarong Zhou, Bingqiang Gao and Xiaohui Qian collected and assemblied the information; Weilin Wang proofread and revised the manuscript; all of the authors approved the final version to be published.

Abbreviations

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- TACE

transarterial chemoembolization

- RFA

radiofrequency ablation

- PD-1

programmed cell death protein 1

- CTLA-4

cytotoxic T lymphocyte associated antigen 4

- TME

tumor microenvironment

- TAM

tumor associated macrophage

- DC

dendritic cell

- MoMFs

monocyte-derived macrophages

- LPS

lipopolysaccharides

- IFN-γ

interferon-γ

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- TLR

toll like receptor

- NO

nitric oxide

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- IL-1

interleukin 1

- CXCL5

C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 5

- CCL5

C-C motif chemokine ligand 5

- CSF

colony stimulating factor

- mtDNA

mitochondrial DNA

- miRNAs

micro RNAs

- circRNAs

cicular RNAs

- TGF-β

transforming growth factor beta

- Tregs

regulatory T cells

- IGF1

insuline-like growth factor

- EMT

epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- IDO

indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase

- HIF-1α

hypoxia inducible factor 1α

- PD-L1

programmed cell death ligand 1

- CXCR4

C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 4

- ZA

zoledronic acid

- CSC

cancer stem cell

- HGF

hepatocyte growth factor

- BrMC

8-bromo-7-methoxychrysin

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- Arg 1

arginine 1

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD. Cancer statistics, 2019. 2019; 69: 7-34. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Sun JY, Yin T, Zhang XY. Therapeutic advances for patients with intermediate hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:12116–21. doi: 10.1002/jcp.28019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines. management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of hepatology. 2012;56:908–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumar A, Acharya SK, Singh SP, Arora A, Dhiman RK, Aggarwal R. et al. 2019 Update of Indian National Association for Study of the Liver Consensus on Prevention, Diagnosis, and Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in India: The Puri II Recommendations. Journal of clinical and experimental hepatology. 2020;10:43–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2019.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Méndez-Blanco C, Fondevila F. Sorafenib resistance in hepatocarcinoma: role of hypoxia-inducible factors. Experimental & Molecular Medicine. 2018;50:1–9. doi: 10.1038/s12276-018-0159-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hargadon KM, Johnson CE, Williams CJ. Immune checkpoint blockade therapy for cancer: An overview of FDA-approved immune checkpoint inhibitors. International immunopharmacology. 2018;62:29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2018.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Newick K, O'Brien S, Moon E, Albelda SM. CAR T Cell Therapy for Solid Tumors. Annual review of medicine. 2017;68:139–52. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-062315-120245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wei SC, Duffy CR. Fundamental Mechanisms of Immune Checkpoint Blockade Therapy. Cancer Discovery. 2018;8:1069–86. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-0367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El-Khoueiry AB, Sangro B, Yau T, Crocenzi TS, Kudo M, Hsu C. et al. Nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (CheckMate 040): an open-label, non-comparative, phase 1/2 dose escalation and expansion trial. Lancet (London, England) 2017;389:2492–502. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31046-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang JD, Hainaut P, Gores GJ. A global view of hepatocellular carcinoma: trends, risk, prevention and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16:589–604. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0186-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forner A, Llovet JM, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet (London, England) 2012;379:1245–55. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61347-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu C, Rong D, Zhang B, Zheng W, Wang X, Chen Z. et al. Current perspectives on the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment in hepatocellular carcinoma: challenges and opportunities. Molecular cancer. 2019;18:130. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-1047-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fu Y, Liu S, Zeng S, Shen H. From bench to bed: the tumor immune microenvironment and current immunotherapeutic strategies for hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of experimental & clinical cancer research: CR. 2019;38:396. doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1396-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Capece D, Fischietti M, Verzella D, Gaggiano A, Cicciarelli G, Tessitore A. et al. The inflammatory microenvironment in hepatocellular carcinoma: a pivotal role for tumor-associated macrophages. BioMed research international. 2013;2013:187204. doi: 10.1155/2013/187204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanahan D, Coussens LM. Accessories to the crime: functions of cells recruited to the tumor microenvironment. Cancer cell. 2012;21:309–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tian Z, Hou X, Liu W, Han Z, Wei L. Macrophages and hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell & Bioscience. 2019;9:79. doi: 10.1186/s13578-019-0342-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu W, Liu K, Chen M, Sun JY, McCaughan GW, Lu XJ. et al. Immunotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: recent advances and future perspectives. Ther Adv Med. Oncol. 2019;11:1758835919862692. doi: 10.1177/1758835919862692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gun SY, Lee SWL, Sieow JL, Wong SC. Targeting immune cells for cancer therapy. Redox biology. 2019;25:101174. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2019.101174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Okusaka T, Ikeda M. Immunotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: current status and future perspectives. ESMO open. 2018;3:e000455. doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2018-000455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cassetta L, Pollard JW. Targeting macrophages: therapeutic approaches in cancer. Nature reviews Drug discovery. 2018;17:887–904. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2018.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruffell B, Coussens LM. Macrophages and therapeutic resistance in cancer. Cancer cell. 2015;27:462–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Galdiero MR, Bonavita E, Barajon I, Garlanda C, Mantovani A, Jaillon S. Tumor associated macrophages and neutrophils in cancer. Immunobiology. 2013;218:1402–10. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Noy R, Pollard JW. Tumor-associated macrophages: from mechanisms to therapy. Immunity. 2014;41:49–61. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fu XT, Song K, Zhou J, Shi YH, Liu WR, Shi GM. et al. Tumor-associated macrophages modulate resistance to oxaliplatin via inducing autophagy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer cell international. 2019;19:71. doi: 10.1186/s12935-019-0771-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dong N, Shi X, Wang S, Gao Y, Kuang Z, Xie Q. et al. M2 macrophages mediate sorafenib resistance by secreting HGF in a feed-forward manner in hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2019;121:22–33. doi: 10.1038/s41416-019-0482-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim J, Bae JS. Tumor-Associated Macrophages and Neutrophils in Tumor Microenvironment. Mediators of inflammation. 2016;2016:6058147. doi: 10.1155/2016/6058147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clappaert EJ, Murgaski A, Van Damme H, Kiss M, Laoui D. Diamonds in the Rough: Harnessing Tumor-Associated Myeloid Cells for Cancer Therapy. Frontiers in immunology. 2018;9:2250. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petty AJ, Yang Y. Tumor-associated macrophages: implications in cancer immunotherapy. Immunotherapy. 2017;9:289–302. doi: 10.2217/imt-2016-0135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tacke F. Targeting hepatic macrophages to treat liver diseases. Journal of hepatology. 2017;66:1300–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wynn TA, Chawla A, Pollard JW. Macrophage biology in development, homeostasis and disease. Nature. 2013;496:445–55. doi: 10.1038/nature12034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gordon S, Plüddemann A, Martinez Estrada F. Macrophage heterogeneity in tissues: phenotypic diversity and functions. Immunological reviews. 2014;262:36–55. doi: 10.1111/imr.12223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heymann F, Tacke F. Immunology in the liver-from homeostasis to disease. Nature reviews Gastroenterology & hepatology. 2016;13:88–110. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vannella KM, Wynn TA. Mechanisms of Organ Injury and Repair by Macrophages. Annual review of physiology. 2017;79:593–617. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-022516-034356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Degroote H, Van Dierendonck A, Geerts A, Van Vlierberghe H, Devisscher L. Preclinical and Clinical Therapeutic Strategies Affecting Tumor-Associated Macrophages in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J of Immunology Research. 2018;2018:7819520. doi: 10.1155/2018/7819520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krenkel O, Tacke F. Liver macrophages in tissue homeostasis and disease. Nature reviews Immunology. 2017;17:306–21. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Okabe Y, Medzhitov R. Tissue biology perspective on macrophages. Nature immunology. 2016;17:9–17. doi: 10.1038/ni.3320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gordon S, Taylor PR. Monocyte and macrophage heterogeneity. Nature reviews Immunology. 2005;5:953–64. doi: 10.1038/nri1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sica A, Erreni M, Allavena P, Porta C. Macrophage polarization in pathology. Cellular and molecular life sciences: CMLS. 2015;72:4111–26. doi: 10.1007/s00018-015-1995-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Galli SJ, Borregaard N, Wynn TA. Phenotypic and functional plasticity of cells of innate immunity: macrophages, mast cells and neutrophils. Nature immunology. 2011;12:1035–44. doi: 10.1038/ni.2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chawla A, Nguyen KD, Goh YP. Macrophage-mediated inflammation in metabolic disease. Nature reviews Immunology. 2011;11:738–49. doi: 10.1038/nri3071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sica A, Invernizzi P, Mantovani A. Macrophage plasticity and polarization in liver homeostasis and pathology. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md) 2014;59:2034–42. doi: 10.1002/hep.26754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dou L, Shi X, He X, Gao Y. Macrophage Phenotype and Function in Liver Disorder. Frontiers in immunology. 2019;10:3112. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.03112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li XY, Yang X, Zhao QD, Han ZP, Liang L, Pan XR. et al. Lipopolysaccharide promotes tumorigenicity of hepatic progenitor cells by promoting proliferation and blocking normal differentiation. Cancer letters. 2017;386:35–46. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yu LX, Ling Y, Wang HY. Role of nonresolving inflammation in hepatocellular carcinoma development and progression. NPJ precision oncology. 2018;2:6. doi: 10.1038/s41698-018-0048-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Elliott LA, Doherty GA, Sheahan K, Ryan EJ. Human Tumor-Infiltrating Myeloid Cells: Phenotypic and Functional Diversity. Frontiers in immunology. 2017;8:86. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dong P, Ma L, Liu L, Zhao G, Zhang S, Dong L. et al. CD86⁺/CD206⁺, Diametrically Polarized Tumor-Associated Macrophages, Predict Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patient Prognosis. International journal of molecular sciences. 2016;17:320. doi: 10.3390/ijms17030320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bonavita E, Gentile S, Rubino M, Maina V, Papait R, Kunderfranco P. et al. PTX3 is an extrinsic oncosuppressor regulating complement-dependent inflammation in cancer. Cell. 2015;160:700–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weitzenfeld P, Ben-Baruch A. The chemokine system, and its CCR5 and CXCR4 receptors, as potential targets for personalized therapy in cancer. Cancer letters. 2014;352:36–53. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pollard JW. Tumour-educated macrophages promote tumour progression and metastasis. Nature reviews Cancer. 2004;4:71–8. doi: 10.1038/nrc1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kong L, Zhou Y, Bu H, Lv T, Shi Y, Yang J. Deletion of interleukin-6 in monocytes/macrophages suppresses the initiation of hepatocellular carcinoma in mice. Journal of experimental & clinical cancer research: CR. 2016;35:131. doi: 10.1186/s13046-016-0412-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tymoszuk P, Evens H, Marzola V, Wachowicz K, Wasmer MH, Datta S. et al. In situ proliferation contributes to accumulation of tumor-associated macrophages in spontaneous mammary tumors. European journal of immunology. 2014;44:2247–62. doi: 10.1002/eji.201344304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bao D, Zhao J, Zhou X, Yang Q, Chen Y, Zhu J. et al. Mitochondrial fission-induced mtDNA stress promotes tumor-associated macrophage infiltration and HCC progression. Oncogene. 2019;38:5007–20. doi: 10.1038/s41388-019-0772-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhu Y, Yang J, Xu D, Gao XM, Zhang Z, Hsu JL. et al. Disruption of tumour-associated macrophage trafficking by the osteopontin-induced colony-stimulating factor-1 signalling sensitises hepatocellular carcinoma to anti-PD-L1 blockade. Gut. 2019;68:1653–66. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yin C, Han Q, Xu D, Zheng B, Zhao X, Zhang J. SALL4-mediated upregulation of exosomal miR-146a-5p drives T-cell exhaustion by M2 tumor-associated macrophages in HCC. Oncoimmunology. 2019;8:1601479. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2019.1601479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hu ZQ, Zhou SL. Circular RNA Sequencing Identifies CircASAP1 as a Key Regulator in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Metastasis. Hepatology. 2020;72(3):906–922. doi: 10.1002/hep.31068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ravà M, D'Andrea A, Doni M, Kress TR, Ostuni R, Bianchi V. et al. Mutual epithelium-macrophage dependency in liver carcinogenesis mediated by ST18. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md) 2017;65:1708–19. doi: 10.1002/hep.28942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang D, Yang L, Yue D, Cao L, Li L, Wang D. et al. Macrophage-derived CCL22 promotes an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment via IL-8 in malignant pleural effusion. Cancer letters. 2019;452:244–53. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bekkering S, Arts RJW, Novakovic B, Kourtzelis I, van der Heijden C, Li Y. et al. Metabolic Induction of Trained Immunity through the Mevalonate Pathway. Cell. 2018;172:135–46.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Saeed S, Quintin J, Kerstens HH, Rao NA, Aghajanirefah A, Matarese F. et al. Epigenetic programming of monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation and trained innate immunity. Science (New York, NY) 2014;345:1251086. doi: 10.1126/science.1251086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Quail DF, Bowman RL, Akkari L, Quick ML, Schuhmacher AJ, Huse JT. et al. The tumor microenvironment underlies acquired resistance to CSF-1R inhibition in gliomas. Science (New York, NY) 2016;352:aad3018. doi: 10.1126/science.aad3018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thorsson V, Gibbs DL, Brown SD, Wolf D, Bortone DS, Ou Yang TH. et al. The Immune Landscape of Cancer. Immunity. 2019;51:411–2. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chew V, Lai L, Pan L, Lim CJ, Li J, Ong R. et al. Delineation of an immunosuppressive gradient in hepatocellular carcinoma using high-dimensional proteomic and transcriptomic analyses. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2017;114:E5900–e9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1706559114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yao RR, Li JH, Zhang R, Chen RX, Wang YH. M2-polarized tumor-associated macrophages facilitated migration and epithelial-mesenchymal transition of HCC cells via the TLR4/STAT3 signaling pathway. World journal of surgical oncology. 2018;16:9. doi: 10.1186/s12957-018-1312-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xiao P, Long X, Zhang L, Ye Y, Guo J. Neurotensin/IL-8 pathway orchestrates local inflammatory response and tumor invasion by inducing M2 polarization of Tumor-Associated macrophages and epithelial-mesenchymal transition of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Oncoimmunology. 2018;7(7):e1440166. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2018.1440166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yin Z, Huang J, Ma T, Li D, Wu Z, Hou B. et al. Macrophages activating chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 8/miR-17 cluster modulate hepatocellular carcinoma cell growth and metastasis. American journal of translational research. 2017;9:2403–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yan W, Liu X, Ma H. Tim-3 fosters HCC development by enhancing TGF-β-mediated alternative activation of macrophages. Gut. 2015;64(10):1593–604. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jiang J, Wang GZ, Wang Y, Huang HZ, Li WT, Qu XD. Hypoxia-induced HMGB1 expression of HCC promotes tumor invasiveness and metastasis via regulating macrophage-derived IL-6. Experimental cell research. 2018;367:81–8. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2018.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang YL, Li Q, Yang XM, Fang F, Li J, Wang YH. et al. SPON2 Promotes M1-like Macrophage Recruitment and Inhibits Hepatocellular Carcinoma Metastasis by Distinct Integrin-Rho GTPase-Hippo Pathways. Cancer research. 2018;78:2305–17. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-2867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhou SL, Hu ZQ, Zhou ZJ, Dai Z, Wang Z, Cao Y. et al. miR-28-5p-IL-34-macrophage feedback loop modulates hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md) 2016;63:1560–75. doi: 10.1002/hep.28445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Li L, Sun P, Zhang C, Li Z, Cui K, Zhou W. MiR-98 modulates macrophage polarization and suppresses the effects of tumor-associated macrophages on promoting invasion and epithelial-mesenchymal transition of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer cell international. 2018;18:95. doi: 10.1186/s12935-018-0590-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ye Y, Xu Y, Lai Y, He W, Li Y, Wang R. et al. Long non-coding RNA cox-2 prevents immune evasion and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma by altering M1/M2 macrophage polarization. J Cell Biochem. 2018;119:2951–63. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tan S, Zhao J, Sun Z, Cao S, Niu K, Zhong Y. et al. Hepatocyte-specific TAK1 deficiency drives RIPK1 kinase-dependent inflammation to promote liver fibrosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. PNAS. 2020;117:14231–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2005353117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wu J, Gao W, Tang Q, Yu Y, You W, Wu Z, M2 macrophage-derived exosomes facilitate hepatocarcinoma metastasis by transferring α(M) β(2) integrin to tumor cells. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md) 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Retracted]

- 74.Yang Y, Ye YC. Crosstalk between hepatic tumor cells and macrophages via Wnt/β-catenin signaling promotes M2-like macrophage polarization and reinforces tumor malignant behaviors. Cell Death & Disease. 2018;9:793. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0818-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Liu HT, Huang DA, Li MM, Liu HD, Guo K. HSF1: a mediator in metabolic alteration of hepatocellular carcinoma cells in cross-talking with tumor-associated macrophages. American journal of translational research. 2019;11:5054–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ye LY, Chen W, Bai XL, Xu XY, Zhang Q, Xia XF. et al. Hypoxia-Induced Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Induces an Immunosuppressive Tumor Microenvironment to Promote Metastasis. Cancer research. 2016;76:818–30. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhang J, Zhang Q, Lou Y, Fu Q, Chen Q, Wei T. et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α/interleukin-1β signaling enhances hepatoma epithelial-mesenchymal transition through macrophages in a hypoxic-inflammatory microenvironment. Hepatology. 2018;67:1872–89. doi: 10.1002/hep.29681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wu Q, Zhou W, Yin S, Zhou Y, Chen T, Qian J. et al. Blocking Triggering Receptor Expressed on Myeloid Cells-1-Positive Tumor-Associated Macrophages Induced by Hypoxia Reverses Immunosuppression and Anti-Programmed Cell Death Ligand 1 Resistance in Liver Cancer. Hepatology. 2019;70:198–214. doi: 10.1002/hep.30593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Deryugina EI, Quigley JP. Tumor angiogenesis: MMP-mediated induction of intravasation- and metastasis-sustaining neovasculature. Matrix biology: journal of the International Society for Matrix Biology. 2015;44-46:94–112. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bartneck M, Schrammen PL, Möckel D, Govaere O, Liepelt A, Krenkel O. et al. The CCR2(+) Macrophage Subset Promotes Pathogenic Angiogenesis for Tumor Vascularization in Fibrotic Livers. Cellular and molecular gastroenterology and hepatology. 2019;7:371–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2018.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zang M, Li Y, He H, Ding H, Chen K, Du J. et al. IL-23 production of liver inflammatory macrophages to damaged hepatocytes promotes hepatocellular carcinoma development after chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Biochimica et biophysica acta Molecular basis of disease. 2018;1864:3759–70. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2018.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Meng YM, Liang J, Wu C, Xu J, Zeng DN, Yu XJ. et al. Monocytes/Macrophages promote vascular CXCR4 expression via the ERK pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncoimmunology. 2018;7:e1408745. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1408745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhang W, Zhu XD, Sun HC, Xiong YQ, Zhuang PY, Xu HX. et al. Depletion of tumor-associated macrophages enhances the effect of sorafenib in metastatic liver cancer models by antimetastatic and antiangiogenic effects. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2010;16:3420–30. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ma S, Chan KW, Hu L, Lee TK, Wo JY, Ng IO. et al. Identification and characterization of tumorigenic liver cancer stem/progenitor cells. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2542–56. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nio K, Yamashita T, Okada H, Kondo M, Hayashi T, Hara Y. et al. Defeating EpCAM(+) liver cancer stem cells by targeting chromatin remodeling enzyme CHD4 in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of hepatology. 2015;63:1164–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kopanja D, Pandey A, Kiefer M, Wang Z, Chandan N, Carr JR. et al. Essential roles of FoxM1 in Ras-induced liver cancer progression and in cancer cells with stem cell features. Journal of hepatology. 2015;63:429–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wan S, Zhao E, Kryczek I, Vatan L, Sadovskaya A, Ludema G. et al. Tumor-associated macrophages produce interleukin 6 and signal via STAT3 to promote expansion of human hepatocellular carcinoma stem cells. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:1393–404. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.08.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fan QM, Jing YY, Yu GF, Kou XR, Ye F, Gao L. et al. Tumor-associated macrophages promote cancer stem cell-like properties via transforming growth factor-beta1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer letters. 2014;352:160–8. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chen Y, Wen H, Zhou C, Su Q, Lin Y, Xie Y. et al. TNF-α derived from M2 tumor-associated macrophages promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer stemness through the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in SMMC-7721 hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Experimental cell research. 2019;378:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2019.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wang Y, Wang B, Xiao S, Li Y, Chen Q. miR-125a/b inhibits tumor-associated macrophages mediated in cancer stem cells of hepatocellular carcinoma by targeting CD90. J Cell Biochem. 2019;120:3046–55. doi: 10.1002/jcb.27436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ngabire D, Kim GD. Autophagy and Inflammatory Response in the Tumor Microenvironment. International journal of molecular sciences. Int J Mol Sci. 2017. 18(9) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 92.Sun K, Xu L, Jing Y, Han Z, Chen X, Cai C. et al. Autophagy-deficient Kupffer cells promote tumorigenesis by enhancing mtROS-NF-κB-IL1α/β-dependent inflammation and fibrosis during the preneoplastic stage of hepatocarcinogenesis. Cancer letters. 2017;388:198–207. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chang CP, Su YC, Lee PH, Lei HY. Targeting NFKB by autophagy to polarize hepatoma-associated macrophage differentiation. Autophagy. 2013;9:619–21. doi: 10.4161/auto.23546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lin H, Yan J, Wang Z, Hua F, Yu J, Sun W. et al. Loss of immunity-supported senescence enhances susceptibility to hepatocellular carcinogenesis and progression in Toll-like receptor 2-deficient mice. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md) 2013;57:171–82. doi: 10.1002/hep.25991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tan HY, Wang N, Man K, Tsao SW, Che CM, Feng Y. Autophagy-induced RelB/p52 activation mediates tumour-associated macrophage repolarisation and suppression of hepatocellular carcinoma by natural compound baicalin. Cell death & disease. 2015;6:e1942. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Xia S, Pan Y, Liang Y, Xu J, Cai X. The microenvironmental and metabolic aspects of sorafenib resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma. EBioMedicine. 2020;51:102610. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.102610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yao W, Ba Q, Li X, Li H, Zhang S, Yuan Y. et al. A Natural CCR2 Antagonist Relieves Tumor-associated Macrophage-mediated Immunosuppression to Produce a Therapeutic Effect for Liver Cancer. EBioMedicine. 2017;22:58–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Zhou SL, Zhou ZJ, Hu ZQ, Huang XW, Wang Z, Chen EB. et al. Tumor-Associated Neutrophils Recruit Macrophages and T-Regulatory Cells to Promote Progression of Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Resistance to Sorafenib. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1646–58.e17. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hage C, Hoves S, Strauss L, Bissinger S, Prinz Y, Pöschinger T. et al. Sorafenib Induces Pyroptosis in Macrophages and Triggers Natural Killer Cell-Mediated Cytotoxicity Against Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md) 2019;70:1280–97. doi: 10.1002/hep.30666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mantovani A, Marchesi F, Malesci A, Laghi L, Allavena P. Tumour-associated macrophages as treatment targets in oncology. Nature reviews Clinical oncology. 2017;14:399–416. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Tang X, Mo C, Wang Y, Wei D, Xiao H. Anti-tumour strategies aiming to target tumour-associated macrophages. Immunology. 2013;138:93–104. doi: 10.1111/imm.12023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Jaiswal S, Jamieson CH, Pang WW, Park CY, Chao MP, Majeti R. et al. CD47 is upregulated on circulating hematopoietic stem cells and leukemia cells to avoid phagocytosis. Cell. 2009;138:271–85. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Tseng D, Volkmer JP, Willingham SB, Contreras-Trujillo H, Fathman JW, Fernhoff NB. et al. Anti-CD47 antibody-mediated phagocytosis of cancer by macrophages primes an effective antitumor T-cell response. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:11103–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305569110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Okazawa H, Motegi S, Ohyama N, Ohnishi H, Tomizawa T, Kaneko Y. et al. Negative regulation of phagocytosis in macrophages by the CD47-SHPS-1 system. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md: 1950) 2005;174:2004–11. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.4.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Chen J, Zheng DX, Yu XJ, Sun HW, Xu YT, Zhang YJ. et al. Macrophages induce CD47 upregulation via IL-6 and correlate with poor survival in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Oncoimmunology. 2019;8:e1652540. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2019.1652540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Yang HD, Kim HS, Kim SY, Na MJ, Yang G, Eun JW. et al. HDAC6 Suppresses Let-7i-5p to Elicit TSP1/CD47-Mediated Anti-Tumorigenesis and Phagocytosis of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md) 2019;70:1262–79. doi: 10.1002/hep.30657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lo J, Lau EY, So FT, Lu P, Chan VS, Cheung VC. et al. Anti-CD47 antibody suppresses tumour growth and augments the effect of chemotherapy treatment in hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver international. 2016;36:737–45. doi: 10.1111/liv.12963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Xiao Z, Chung H, Banan B, Manning PT, Ott KC, Lin S. et al. Antibody mediated therapy targeting CD47 inhibits tumor progression of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer letters. 2015;360:302–9. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.02.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Chai ZT, Zhu XD, Ao JY, Wang WQ, Gao DM, Kong J. et al. microRNA-26a suppresses recruitment of macrophages by down-regulating macrophage colony-stimulating factor expression through the PI3K/Akt pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of hematology & oncology. 2015;8:56. doi: 10.1186/s13045-015-0150-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Li X, Yao W, Yuan Y, Chen P, Li B, Li J. et al. Targeting of tumour-infiltrating macrophages via CCL2/CCR2 signalling as a therapeutic strategy against hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut. 2017;66:157–67. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Yao M, Wang L, Dong Z, Qian Q, Shi Y, Yu D. et al. Glypican-3 as an emerging molecular target for hepatocellular carcinoma gene therapy. Tumour biology. 2014;35:5857–68. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-1776-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Takai H, Ashihara M, Ishiguro T, Terashima H, Watanabe T, Kato A. et al. Involvement of glypican-3 in the recruitment of M2-polarized tumor-associated macrophages in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer biology & therapy. 2009;8:2329–38. doi: 10.4161/cbt.8.24.9985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Zhu AX, Gold PJ, El-Khoueiry AB, Abrams TA, Morikawa H, Ohishi N. et al. First-in-man phase I study of GC33, a novel recombinant humanized antibody against glypican-3, in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Clinical cancer research. 2013;19:920–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Ikeda M, Ohkawa S, Okusaka T, Mitsunaga S, Kobayashi S, Morizane C. et al. Japanese phase I study of GC33, a humanized antibody against glypican-3 for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer science. 2014;105:455–62. doi: 10.1111/cas.12368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Rogers TL, Wind N, Hughes R, Nutter F, Brown HK, Vasiliadou I. et al. Macrophages as potential targets for zoledronic acid outside the skeleton-evidence from in vitro and in vivo models. Cellular oncology (Dordrecht) 2013;36:505–14. doi: 10.1007/s13402-013-0156-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Coscia M, Quaglino E, Iezzi M, Curcio C, Pantaleoni F, Riganti C. et al. Zoledronic acid repolarizes tumour-associated macrophages and inhibits mammary carcinogenesis by targeting the mevalonate pathway. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine. 2010;14:2803–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00926.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Zhou DY, Qin J, Huang J, Wang F, Xu GP, Lv YT. et al. Zoledronic acid inhibits infiltration of tumor-associated macrophages and angiogenesis following transcatheter arterial chemoembolization in rat hepatocellular carcinoma models. Oncology letters. 2017;14:4078–84. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.6717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Wu L, Zhang X, Zheng L, Zhao H, Yan G, Zhang Q. et al. RIPK3 Orchestrates Fatty Acid Metabolism in Tumor-Associated Macrophages and Hepatocarcinogenesis. Cancer Immunology Research. 2020;8:710–21. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-19-0261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Sun S, Cui Y, Ren K, Quan M, Song Z, Zou H. et al. 8-bromo-7-methoxychrysin Reversed M2 Polarization of Tumor-associated Macrophages Induced by Liver Cancer Stem-like Cells. Anti-cancer agents in medicinal chemistry. 2017;17:286–93. doi: 10.2174/1871520616666160204112556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Ao JY, Zhu XD, Chai ZT, Cai H, Zhang YY, Zhang KZ. et al. Colony-Stimulating Factor 1 Receptor Blockade Inhibits Tumor Growth by Altering the Polarization of Tumor-Associated Macrophages in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Molecular cancer therapeutics. 2017;16:1544–54. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-16-0866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]