Abstract

The rapid development and remarkable success of checkpoint inhibitors have provided significant breakthroughs in cancer treatment, including hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). However, only 15-20% of HCC patients can benefit from checkpoint inhibitors. Cancer stem cells (CSCs) are responsible for recurrence, metastasis, and local and systemic therapy resistance in HCC. Accumulating evidence has suggested that HCC CSCs can create an immunosuppressive microenvironment through certain intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms, resulting in immune evasion. Intrinsic evasion mechanisms mainly include activation of immune-related CSC signaling pathways, low-level expression of antigen presenting molecules, and high-level expression of immunosuppressive molecules. External evasion mechanisms are mainly related to HBV/HCV infection, alcoholic/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, hypoxia stimulation, abnormal angiogenesis, and crosstalk between CSCs and immune cells. A better understanding of the complex mechanisms of CSCs involved in immune evasion will contribute to therapies for HCC. Here we will outline the detailed mechanisms of immune evasion for CSCs, and provide an overview of the current immunotherapies targeting CSCs in HCC.

Keywords: hepatocellular carcinoma, cancer stem cells, immune evasion, targeting, immunotherapy

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the leading causes of cancer-associated deaths worldwide, accounting for approximately 75-85% of primary liver cancers 1, 2. Hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), alcoholic, and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) are major risk factors in the development of HCC 3. The tumor burden is highest in East Asia (more than 50% in China) and Africa because of HBV infection, while HCC incidence and mortality are increasing rapidly in the United States and Europe due to alcohol consumption and NASH 4. Most patients with HCC are diagnosed at advanced stages with liver disease and cirrhosis, missing the opportunity for surgery. Despite several advances in the treatment of HCC, particularly in targeted therapy and immunotherapy, the 5-year survival rate remains poor 5. Drug resistance, tumor metastasis and recurrence are the major causes of poor prognosis in HCC patients.

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) have been shown to be responsible for recurrence, metastasis, and local and systemic therapy resistance in HCC 6. Moreover, an overwhelming number of studies have suggested that CSCs can form an immunosuppressive microenvironment through both intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms to induce ineffective antitumor immune responses 7. Application of immunotherapy, especially programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) and programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) monoclonal antibodies, to a variety of solid tumors (including HCC) represents a major breakthrough in cancer treatment 8, 9. However, most patients who have received immunotherapy still experience progression and metastasis 10. Considering that CSCs are a reservoir for the progression and metastasis of HCC, immunotherapy that targets CSCs may be an exciting research field.

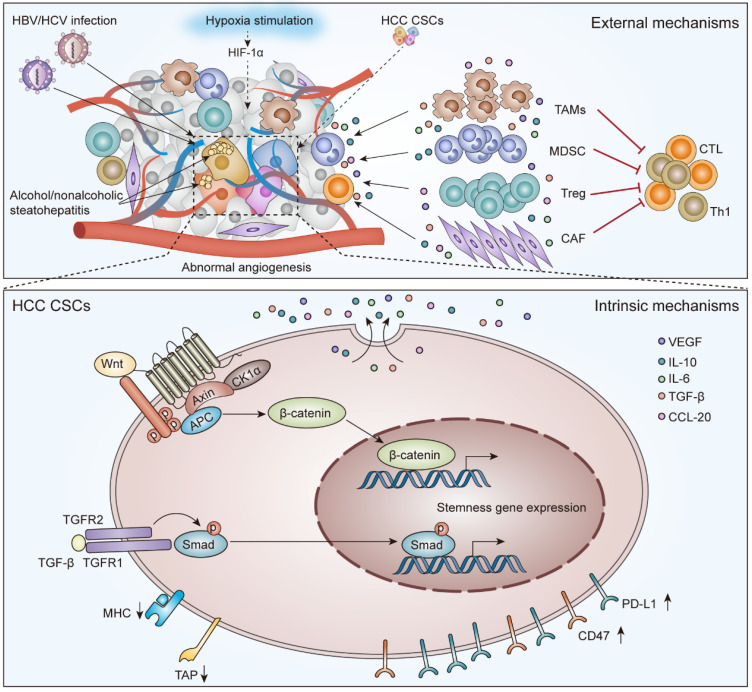

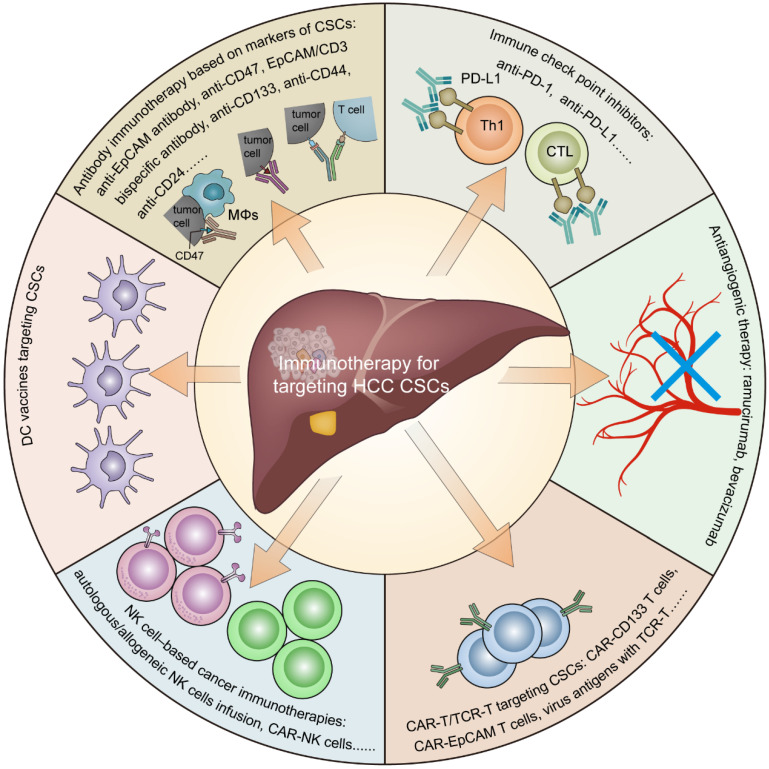

In this review, we summarize the role of CSCs in the tumor immunosuppressive environment (Figure 1) and provide an overview of the current immunotherapies targeting CSCs in HCC (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

The external and intrinsic mechanisms to mediate immunotherapy resistance for CSCs in HCC. External evasion mechanisms are mainly related to HBV/HCV infection, alcohol/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, hypoxia stimulation, abnormal angiogenesis, and crosstalk between CSCs and immune cells. Intrinsic evasion mechanisms mainly include activation of the Wnt/β-Catenin signaling pathway and TGF-β signaling pathway, low-level expression of TAP and/or MHC molecules, and high-level expression of CD47 and PD-L1.

Figure 2.

Immunotherapy for targeting cancer stem cells in hepatocellular carcinoma. Including antibody immunotherapy based on CSC markers, immune checkpoint inhibitors, antiangiogenic therapy, CAR-T/TCR-T cell therapy, NK cell-based cancer immunotherapies, and DC vaccines.

CSCs and immune evasion in HCC

CSCs are a small population of cells that can self-renew and differentiate to initiate and maintain tumor growth 11. T Lapidot and colleagues first observed the existence of CSCs by demonstrating that CD34+/CD38- myeloid leukemia (AML) cells have the ability to initiate tumors in NOD/SCID mice 12. HCC stem cells were first identified as side population (SP) cells by Haraguchi and colleagues in 2006 13, 14. They found that SP cells in HCC were more resistant to chemotherapy drugs (including 5-fluorouracil, doxorubicin and gemcitabine) than non-SP cells. Chiba et al. confirmed that as few as 1000 HCC SP cells have tumorigenic ability in NOD/SCID mice, whereas up to 1×106 non-SP cells were unable to initiate tumors 15. Since then, according to xenotransplantation experiments, several cellular biomarkers of CSCs in HCC have been identified, including epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM), CD133, CD44, CD90, CD13, CD24, OV6, CD47, calcium channel α2δ1 isoform5, and intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) 6, 16. Moreover, related studies showed that high expression of these CSC markers was associated with poor prognosis in HCC patients 17-22.

The existence of HCC CSCs indicates tumor heterogeneity and hierarchy, which is a hallmark feature of resistance to immunotherapy 23, 24. Zheng and colleagues observed that CSCs are also heterogeneous, as determined by single-cell transcriptome and functional analysis of HCC cells. They found that different CSC subpopulations have distinct molecular signatures that were independently correlated with poor prognosis in HCC patients 25. After decades of research, CSCs were found to mediate immunotherapy resistance through various intrinsic and external mechanisms 26. Intrinsic mechanisms of immune evasion include related stem cell pathway activation, the low-level expression of cellular antigen processing and presentation molecules, and the high-level expression of CD47 and PD-L1. External mechanisms of immune evasion include HBV/HCV infection, alcoholic/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, hypoxia stimulation, abnormal angiogenesis, and infiltration of suppressive immune cells (Figure 1) 27-29.

Intrinsic factors of immune evasion

CSC signaling pathways and immune evasion

In HCC CSCs, signaling pathways involved in self-renewal and differentiation characteristics mainly include the Wnt/β-Catenin signaling pathway, Notch signaling pathway, Hedgehog signaling pathway, TGF-β signaling pathway, and AKT signaling pathway 26, 30, 31. The Wnt/β-Catenin signaling pathway and TGF-β signaling pathway are closely related to immune evasion in HCC 32. Intriguing studies have demonstrated that the aberrant activation of the tumor-intrinsic Wnt/β-Catenin signaling pathway correlates with a low proportion of T cell infiltration in the tumor microenvironment (TME) of HCC and melanoma tumor samples 33, 34. Tang and colleagues suggested that there was a functional link between the TGF-β signaling pathway and IL-6 in HCC 35. Moreover, IL-6 (Th2 cytokine) and TGF-β play an important role in the generation of an inhibitory immune microenvironment, antagonizing cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) and inducing antitumor immunity 36, 37. Other studies have found that Notch pathway activation was associated with low CTL activity by recruiting tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) or myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) in other tumors (including pancreatic cancer, ovarian cancer, prostate cancer) 38-41.

Immunological properties of CSCs in HCC

A major mechanism by which CSCs avoid being attacked by the immune system involves minimization of antigenicity by downregulating key components of the cellular antigen processing and presentation machinery, mainly including transporters associated with antigen processing (TAP) and/or major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules 7, 32. CSCs or other tumor cells of HCC lack targetability due to rare presentation by human leukocyte antigen (HLA) complexes 42. In addition, Di Tomaso et al. found that glioblastoma CSCs were weakly positive and negative for MHC-I and MHC-II, leading to a lack of a T cell-mediated immune response 43. Interestingly, downregulation or loss of HLA-I/II expression in spheres was also observed in tumor spheres (including colon, pancreas, and breast carcinoma), which were composed of CSCs 44. Thus, downregulation or defects in antigen processing and presentation molecules provide a means for CSCs to evade CTL-mediated immune responses.

Additionally, CSCs have been found to express high levels of CD47 (the “don't eat me” signal), which inhibits macrophage phagocytosis by binding to its cognate ligand, signal-regulatory-protein-α (SIRPα) 45, 46. Lee and colleagues suggested that CD47 is preferentially expressed in liver CSCs, contributing to tumor initiation, self-renewal, and metastasis, and is significantly associated with poor clinical outcome 47. Therefore, CD47 has been identified as a marker of CSCs in HCC 16. Moreover, the high expression of CD47 in sorafenib-resistant HCC cells and samples is dependent on NF-κB expression 48. TAM-derived IL-6 induced CD47 upregulation in HCC through activation of the STAT3 pathway and correlated with poor survival in HCC patients 49. In summary, CSCs with high expression of CD47 in HCC can effectively avoid phagocytosis by macrophages and thus provide CSCs with a means of immune evasion.

Moreover, accumulating evidence has indicated that CSCs express high levels of PD-L1, which induce T cell apoptosis by binding to its cognate receptor PD-1. Hsu et al. demonstrated that epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) enriched more PD-L1 in CSCs of breast and colon cancer cells by the EMT/β-catenin/STT3/PD-L1 signaling axis than non-CSCs 50. In the case of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SCCHN), PD-L1 was also highly expressed on CD44+ cells (CSCs) compared to CD44- cells (non-CSCs), which was found to be dependent on the constitutive phosphorylation of STAT3 in CSCs 51. Although CSCs have been found to overexpress PD-L1 in a variety of tumors 52, no relevant studies have focused on PD-L1 and CSCs in HCC. Recently, two types of anti‐PD‐1 monoclonal antibodies, nivolumab and pembrolizumab, have been FDA-approved as second‐line therapies for advanced HCC, and a small percentage of patients have achieved complete remission (CR), resulting in long-term survival 53, 54. Therefore, we speculate that anti-PD-1 therapy may be effective in clearing PD-L1-overexpressing CSCs in CR patients with HCC, which needs to be validated in future studies.

External mechanisms of immune evasion

HBV/HCV infection

HBV and HCV infections are major risk factors for HCC development and are also associated with the acquisition of a stem-like phenotype in HCC 55-58. Hepatitis B virus X protein (HBx) is a 16.5 KDa protein, which has been shown to promote the expression of hepatoma stem cell markers (including EpCAM, CD133, CD90, etc.), contributing to tumor initiation and migration 59, 60. In addition, chronic HCV infection can potentiate CSC generation by inducing CaM kinase-like-1 (DCAMKL-1), EMT, and hepatic stem cell-related factors 55, 56. Moreover, chronic HBV/HCV infection promoted a viral-related inflammatory environment, which increased the expression of stemness-related properties (OCT4/Nanog, IGF-IR) by inflammatory cytokines in HCC 61. Chang and colleagues also demonstrated that the activation of IL6/IGFIR through induction of OCT4/NANOG expression was related to poor prognosis in HBV-related HCC 62. Furthermore, a virus-associated inflammatory microenvironment can antagonize the antiviral immune response, as well as the antitumor response through recruitment of macrophages and the secretion of IL-6 61, 62.

Alcoholic and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

As we known, alcoholic, and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) have emerged as an important risk factor in the development of HCC 63. Chronic alcohol intake favors the formation of chronic inflammation, which induces reactive oxygen species (ROS) and DNA damage, thereby facilitating the activation of mutations in tumor stem cell-associated genes. Several studies have demonstrated that alcohol can induce the emergence of CSCs in HCC 64. Machida and colleagues suggested that Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) plays an important role in the induction of synergistic liver oncogenesis by alcohol and HCV, depending on an obligatory function for Nanog, a stem cell marker of TLR4 downstream gene 65. In addition, CD133+/CD49f+ tumor stem cells isolated from alcohol-fed HCV Ns5a or core transgenic mice, are tumorigenic based on the roles of TLR4 and Nanog, which is correlated with TGF-β signaling pathway due to Nanog-mediated expression of IGF2BP3 and YAP1 66. Ambade et al. found that alcoholic steatohepatitis accelerates early HCC by increasing the stemness and miR-122-mediated hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) activation 67. Related studies also have verified that there is a close link between NASH and CSCs in HCC. Qin and colleagues demonstrated that neuroblastoma derived homolog (MYCN) high expression (MYCNhigh) CSC-like HCC cells have more unsaturated fatty acids, and lipid desaturation-mediated endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress signaling regulates the expression of MYCN gene in HCC CSCs 68. Chong et al. showed that saturated fatty acid can induce the properties of CSC in HCC through NF-κB activation 69. Moreover, NASH can lead to the reshaping of local TME, which weakens the antitumor functions of CD4+ T cells, cytotoxic CD8+ T cells, natural killer (NK) cells and Th17 cells 70-74. Additionally, alcohol or NASH-related HCC usually develops with advanced liver fibrosis and cirrhosis, which can induce the formation of hypoxia, contributing to CSC-mediated immune escape in HCC.

Hypoxia and Angiogenesis

Hypoxia is common in HCC, especially in patients with liver cirrhosis 75. Hypoxia can induce EMT and increase the expression of stemness-related genes, which further increases the proportion of CSCs in HCC 76-79. HIF-1a is a major transcription factor involved in the hypoxic response of hepatoma cells. Ye et al. demonstrated that HIF-1a-induced EMT led to the creation of an immunosuppressive TME to promote the metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. They found that hypoxia-induced EMT of hepatoma cells recruited and educated suppressive indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO)-overexpressing TAMs to inhibit T-cell responses and promote immune tolerance in a CCL20-dependent manner 76. Zhang and colleagues found that under a hypoxic microenvironment, the HIF-1a/IL-1b signaling loop between hepatoma cells and TAMs can promote EMT of cancer cells and metastasis 80. Therefore, hypoxia can induce the phenotype of CSCs and further promote a suppressive TME, allowing tumor cells to escape antitumor immunity 81, 82.

An overwhelming number of studies have described the close crosstalk between CSCs and angiogenesis in the TME of various tumors, including HCC 29, 83, 84. VEGF is an important pro-angiogenic factor that has been shown to play a key role in the generation of a pro-angiogenic TME. Tang and colleagues documented that CD133+ CSCs of HCC can promote tumor angiogenesis through neurotensin/interleukin-8/CXCL1 signaling. Moreover, HCC CSCs preferentially secrete exosomes to promote VEGF secretion from endothelial cells, which in turn promotes tumor angiogenesis 85. Liu et al. found that VEGF increases the proportion of CD133+ CSCs by activating VEGFR2 and enhances their self-renewal capacity by inducing Nanog expression in HCC 86. Meanwhile, VEGF plays an important role in attenuating antitumor effects by negatively affecting antigen-presenting cells (APCs, such as DCs) and effector T cells while positively affecting suppressor immune cells (e.g., TAMs, Tregs, and MDSCs) 87, 88. In sum, the crosstalk between CSCs and angiogenesis may contribute to the suppressive immune microenvironment and immune evasion observed in HCC.

Intratumoral hypoxia is a key driver of tumor angiogenesis 89. Related studies have suggested that HIF-1α can bind to the promoter region of the VEGF gene and promote VEGF expression 90. In summary, the close link between hypoxia, CSCs, and angiogenesis may play an important role in antitumor immunity evasion for HCC patients.

CSC-suppressive immune cell interactions

Over the decades, a large number of studies have been accumulated that extensively describe the interaction of CSCs with the immune system 91, 92. TAMs, as one of the most infiltrating inflammatory cells in the TME, are classified as M1 (tumor-suppressing phenotype) and M2 (tumor-promoting phenotype) macrophages (MΦs). In the TME, TAMs are mostly M2 MΦs that play an important role in attenuating the antitumor immune response 93, 94. Several studies have revealed that CSCs and TAMs can interact closely with each other to suppress antitumor immune effects in various tumors 95, 96. Prostate CSCs can secrete some immunosuppressive molecules, such as TGF-β and IL-4, to promote M2 MΦ polarization 97. CSCs in glioblastoma multiforme can secrete periostin to recruit TAMs 98. Emerging evidence has also revealed that TAMs play a predominant role in the induction and maintenance of CSCs in various tumors by some secretory proteins 96. In HCC, TAM-derived IL-6 can promote the expansion of CD44+ CSCs via the STAT3 signaling pathway 99. At the same time, TAMs can also secrete TGF-β to promote CSC-like properties by inducing EMT in HCC 100. As previously described, CD47 has been identified as a marker of CSCs in HCC, which can escape phagocytosis by M1 MΦs in the TME 16, and hypoxia-induced CSCs can secrete CCL20 to recruit IDO+ TAMs to inhibit T-cell responses and promote immune tolerance 76. Altogether, these findings indicate a predominant role of TAMs in driving the immune evasion of CSCs in HCC. Moreover, NK cells, as key components of the innate immune system, are anti-tumor effector cells, which also can be impaired by soluble cytokines present in the TME (including CSC-derived cytokines), such as PGE2, IL-10, TGF-β1, granulin-epithelin precursor (GEP), and IDO 101, 102. In HCC, GEP is overexpressed in tumor tissue but not in the adjacent normal tissue, which regulated the expression of CSC-related signaling molecules β-catenin, Nanog, Oct4, and Sox2 103. And, GEP renders hepatocellular carcinoma cells resistant to NK cytotoxicity by down-regulating surface expression of MHC class I chain-related molecule A (MICA), ligand for NK activated receptor NK group 2 member D (NKG2D), and up-regulating human leukocyte antigen-E (HLA-E), ligand for NK inhibitory receptor CD94/NKG2A 102.

MDSCs are another type of suppressive immune cell that seems to enable CSCs to escape antitumor immunity 104. Increasing evidence suggests that MDSCs can secrete inflammatory molecules such as prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), IL-6, and nitric oxide (NO) to foster stemness of tumor cells in cervical cancer or breast cancer 105-107. Conversely, glioblastoma CSCs also promote the survival and immunosuppressive activities of MDSCs by secreting macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) 108. In HCC, MDSCs can inhibit NK cells in patients via the NKp30 receptor 109; hypoxia can induce the recruitment of MDSCs in the TME through chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 26 110. Moreover, Xu et al. found that drug-resistant HCC cell-derived IL-6 can enhance the expansion and immunosuppressive function of MDSCs 111. Additionally, HCC CSCs can enhance the production of VEGF, thereby promoting MDSC recruitment in the TME 87. Therefore, the interaction between CSCs and MDSCs can further contribute to immune evasion in HCC. Furthermore, HCC CSCs can attenuate antitumor effects by interacting with Treg cells and cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) 112.

Immunotherapeutic approaches targeting CSCs

Antibody immunotherapy based on markers of CSCs

During the decades, several monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) have been successfully used in clinical patients for the treatment of human cancer, such as antagonists of VEGF, bevacizumab for colorectal cancer, ramucirumab for HCC and so on 113, 114. The mechanisms of antibody-based approaches for targeting CSCs are mainly divided into two parts: the direct inhibitory effect of mAbs and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) 115. Additionally, several bispecific mAbs (BiTE antibodies) consisting of CSC and T cell targets displayed good antitumor effects in some preclinical studies and clinical trials 116.

EpCAM is a common marker of CSCs in HCC. Sun et al. indicated that EpCAM+ circulating tumor cells were associated with poor prognosis in HCC patients after curative resection 117. In HCC cells, EpCAM expression was found to be dependent the activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, and EpCAM could directly bind to the downstream transcription factor Tcf4, which contributed to the formation of the Tcf4/β-catenin complex 118. In an HCC preclinical study, an EpCAM/CD3 bispecific antibody (anti-EpCAM bispecific T cell engager (BiTE) 1H8/CD3) induced strong peripheral blood mononuclear cell-dependent cellular cytotoxicity, inducing strong elimination of HCC cells in vitro and vivo 119. Currently, several II/III stage clinical trials (NCT01320020, NCT00822809, NCT00836654, etc.) have shown that BiTE catumaxomab (Anti-EpCAM x Anti-CD3) can effectively improve the quality of life and survival time of malignant ascites (MA) from ovarian and nonovarian (including gastric, pancreatic, and breast, etc.) cancer patients 120-122. Moreover, according to the analysis of peritoneal fluid samples from 258 MA patients in a phase II/III study (NCT00836654), catumaxomab therapy can significantly promote the activation of peritoneal T cells and eliminate EpCAM+ tumor cells in a manner associated with the release of proinflammatory Th1 cytokines 123. However, in a randomized phase II trial (NCT01504256), compared with chemotherapy alone, catumaxomab followed by chemotherapy did not decrease peritoneal metastasis in gastric cancer patients 124. Therefore, although catumaxomab has achieved promising effects in MA, clinical trials need further exploration in solid tumors, including HCC.

Given that CD47 acts as a marker for HCC CSCs and is crucial for evading phagocytosis by macrophages; thus, targeting CD47 is a promising approach to affect CSCs 125. Preclinical studies demonstrated that anti-CD47 antibody effectively inhibited the growth of HCC, while combination chemotherapy had a synergistic antitumor effect 126, 127. Currently, several anti-CD47 antibodies are currently being studied in clinical trials for a variety of human cancers 128. Related phase I trials suggest that CD47 blockade is well tolerated in patients with hematological malignancies and solid tumors 129, 130. A phase 1b study (NCT02953509) involving patients with relapsed or refractory non-Hodgkin's lymphoma revealed that a total of 50% of the patients had an objective response, with 36% having a complete response, after receiving combination therapy of the Hu5F9-G4 antibody (CD47 blockade) and rituximab 130. However, the effects of antibody-based therapies targeting CD47 need to be further explored in the future in large phase II/III randomized controlled clinical trials.

Based on other HCC CSC markers, such as CD133, CD44, and CD24, related mAbs have demonstrated their effectiveness in eliminating HCC CSCs in preclinical models. Jianhua Huang and colleagues demonstrated that cytokine-induced killer (CIK) cells bound with anti-CD3/anti-CD133 bispecific antibodies can effectively target and kill CD133+ HCC CSCs in vitro and in vivo 131. Wang et al. showed that CD44 antibody-targeted liposomal nanoparticles can target and eliminate HCC CSCs in preclinical models 132. In addition, a phase I trial (NCT01358903) involving patients with advanced, CD44-expressing solid tumors revealed that RG7356, an anti-CD44 humanized antibody, is well tolerated but has limited clinical efficacy (21% patients, stable disease) 133. Ma et al. suggested that anti-CD24 antibody conjugating doxorubicin can improve antitumor efficacy and has less systemic toxicity in an HCC preclinical model 134. At the same time, a high-affinity humanized anti-CD24 antibody (hG7-BM3-VcMMAE conjugate) was designed to target hepatocellular carcinoma in vivo 135. However, these HCC CSC marker-specific, antibody-based therapies require further clinical trials for validation.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors and antiangiogenic therapy

The rapid development and remarkable success of checkpoint inhibitors in the activation of CTLs led to cancer immunotherapy being named the “Breakthrough of the Year” by Science in 2013 136. Considering that CSCs can induce T-cell apoptosis by high expression of PD-L1, which binds to PD-1, immune checkpoint inhibitors may play an important role in CSC targeted therapy. Two PD-1 inhibitors, nivolumab and pembrolizumab, have been approved by the FDA for HCC after treatment failure on sorafenib based on two phase II trials, the Checkmate-040 study and the Keynote‐224 trial, respectively 137, 138. Reportedly, these two trials demonstrated RECIST1.1 objective response in 15-20% of HCC patients, including a small number of these patients with durable responses.

As one of the most vascular solid tumors, the role of angiogenesis has been extensively studied in HCC, and CSCs play an important role in promoting angiogenesis in HCC. Multiple kinase inhibitors with anti‐angiogenic activity, such as sorafenib and lenvatinib, have been approved by the FDA for the treatment of advanced HCC 139, 140. Additional anti‐angiogenic multi‐kinase inhibitors, such as regorafenib and cabozantinib, have been approved for the treatment of advanced HCC after treatment failure with sorafenib 141, 142. Moreover, according to the results of the phase III trials REACH and REACH‐II, ramucirumab (an anti‐VEGF antibody) has been approved for patients with unresectable HCC with AFP ≥ 400 ng/dL who experience sorafenib failure 143, 144. In sum, these effective antiangiogenic therapies in HCC may exert antitumor effects by indirectly targeting CSCs. In addition, the close crosstalk between CSCs and angiogenesis in the TME of HCC supports an inhibitory immune microenvironment, leading to antitumor immune evasion. Therefore, the combination of immunotherapy with VEGF antagonists in HCC is another new promising direction 145. Recently, a global, open-label, phase III trial (IMbrave150) showed that combining atezolizumab (PD-L1 inhibitor) with bevacizumab resulted in better overall and progression-free survival than sorafenib in patients with unresectable HCC (NCT03434379) 146. Based on these exciting results, the FDA approved bevacizumab in combination with atezolizumab as an updated first-line systemic therapy for patients with unresectable HCC 147. Additionally, the REGONIVO trial (phase Ib trial, NCT03406871) demonstrated that the combination of regorafenib plus nivolumab led to an objective response in 20 patients (40%) with gastric and colorectal cancer 148. Taken together, these findings indicated that checkpoint inhibitors in combination with anti‐angiogenic inhibitors may lead to the depletion of CSCs, which contributed to the success of these trials.

CAR-T/TCR-T targeting CSCs

The advent of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell immunotherapy opens a new avenue in adoptive cell therapy, indicating the next breakthrough in immunotherapy 149. According to these unprecedented clinical outcomes of CD19-directed CAR T-cells in patients with certain refractory B cell malignancies, the FDA approved two anti-CD19 CAR-T cell therapies (tisagenlecleucel and axicabtagene ciloleucel) for the treatment of certain hematological malignancies in 2017. Then, the American Society of Clinical Oncology named CAR-T cell therapy “advance of the year” in 2018 150. Indeed, using CAR-T cells to target CSCs is an interesting and promising immunological approach for treating HCC 151. According to the web of clinical trials (https://clinicaltrials.gov/), the most registered type of HCC-related CAR-T clinical trial is GPC-3-targeted CAR-T, mainly because GPC-3 is the specific cell surface marker of HCC 152. In a phase I study (NCT02395250), the results showed that CAR-GPC3 T-cell therapy is well tolerated in GPC3-positive patients with refractory or relapsed HCC, in which two patients had partial responses 153. Moreover, based on the CSC-associated surface markers of HCC, several CAR-T-related clinical trials are ongoing. Wang et al. conducted a phase I clinical study (NCT02541370) using autologous CAR-CD133 T-cells to treat 23 patients with advanced and CD133-positive tumors, including 14 advanced HCC patients. The results showed that CAR-CD133 T-cell therapy was feasible and had controllable toxicities; 3 patients achieved partial remission (including 1 HCC patient), and 14 patients (including 9 HCC patients) acquired stable disease; the 3-month disease control rate was 65.2%, and the median progression-free survival was 5 months 154. Additionally, the efficacy of EpCAM-targeted CAR-T cells has been demonstrated preclinically for several solid tumors, such as colon, prostate, and peritoneal cancers 155-158. Currently, one CAR-EpCAM T-cell clinical trial (NCT03013712) has been registered and is recruiting EpCAM-positive cancer (including HCC).

Another promising adoptive cell therapy, T-cell receptor (TCR)-engineered T-cell immunotherapy, has attracted widespread attention and been extensively studied. Compared with CAR-T cells, TCR-T cells can recognize intracellular tumor-associated antigens depending on the MHC complex. In HCC, targeting alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) or HBV/HCV-associated antigens with TCR-T therapies has shown powerful antitumor effects in preclinical models 159-162. Moreover, a series of clinical trials targeting AFP (NCT03971747, NCT04368182) or virus-associated antigens (NCT02686372, NCT03899415) with TCR-T therapies for HCC are currently underway. Considering that HBV and HCV infections contribute to the acquisition of a stem-like phenotype in HCC, TCR-T cells targeting special viral antigens may effectively clear CSCs. In any case, viral antigen-specific TCR-T cell injection may be a promising strategy for HCC.

NK cell-based cancer immunotherapies

As mentioned previously, CSCs of HCC have low expression of MHC molecules, which contribute to immune escape. Interestingly, the inhibitory receptors of NK cells can recognize MHC-I molecules, hence, NK cells do not usually attack normal cells 163. Therefore, the low-expression of MHC-I on CSCs will make them to be susceptible to be killed by NK cells 164, indicating that NK cell-based cancer immunotherapies may be a promising treatment strategy to target CSCs 32. NK cell-based immunotherapies have achieved encouraging results in hematologic cancers, including IL2-activated haploidentical NK cells infusions 165, and anti-CD19 CAR-NK cell therapy 166, 167. Although some progress is also being made to apply NK cell-based therapies against solid tumors, response rates in patients remain to be unsatisfied 163. In HCC, several NK-cell based I/II phase clinical trials are in progress, such as, autologous/allogeneic NK cells infusion or in combination with other therapies (NCT03319459, NCT04162158, NCT03592706), anti-MUC1 CAR-NK cells (NCT02839954), and so on 168. Moreover, related studies have showed that chemotherapy or radiation therapy can increase the amounts of CSCs in various tumor and induce up-regulating NKG2D ligands MICA and MICB on CSCs, indicating that NK cell-based immunotherapies in combination with radiation therapy or chemotherapy could better eradicate CSCs in HCC 169.

Vaccines targeting CSCs

CSC-directed immunotherapies to promote tumor cell recognition and elimination by the immune system are mainly focused on the use of DC vaccines 170. Related studies have suggested that DC vaccination using CSC-associated antigens can elicit antigen-specific T-cell responses against CSCs in vitro and in vivo 171-173. In HCC, Choi and colleagues suggested that DCs stimulated by EpCAM peptides enhance T cell activation and generate CTLs, thus effectively killing HCC CSCs 174. In addition, SP cell lysate-pulsed DCs have been demonstrated to induce a special T cell response against HCC CSCs and suppress tumor growth in vivo 172. To date, more than 200 completed clinical trials have involved the use of DC vaccines for cancer treatment. Sipuleucel-T (Provenge) is the only FDA-approved DC vaccine loaded with a fusion antigen protein composed of GM-CSF and prostatic acid phosphatase; it has been used to treat prostate cancer patients and has extended the median overall survival by approximately 4 months 175. Based on the remarkable success of checkpoint inhibitors in the treatment of various tumors in the clinic, DC vaccination in combination with checkpoint inhibitors may be an ideal immunotherapy to foster powerful initial specific effector T cell activation 176. Moreover, as shown in the web of clinical trials (https://clinicaltrials.gov/), a series of clinical trials are ongoing based on DC vaccines (loaded with HCC neoantigens or virus-associated antigens) or combined PD-1 monoclonal antibodies. However, DC vaccination using CSC-associated antigens against HCC needs to be further investigated in future preclinical and clinical trials.

Conclusions

In summary, accumulating evidence has suggested that CSCs can create an immunosuppressive microenvironment through certain intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms, resulting in immune evasion in HCC. The intrinsic mechanisms mainly include the following: 1. the activation of immune-related CSC pathways; 2. low-level expression of TAP and/or MHC molecules; and 3. high-level expression of CD47 and PD-L1. The external mechanisms mainly include the following: 1. HBV/HCV infection; 2. alcoholic/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; 3. hypoxia stimulation; 4. abnormal angiogenesis; and 5. infiltration of suppressive immune cells (Figure 1). Currently, immunotherapeutic approaches targeting HCC CSCs mainly include antibody immunotherapy based on CSC markers, immune checkpoint inhibitors, antiangiogenic therapy, CAR-T/TCR-T cell therapy, NK cell-based cancer immunotherapies, and DC vaccines (Figure 2).

However, there are still some hindrances to achieving efficacious immunotherapy targeting CSCs in HCC 11, 177. First, the abovementioned immunotherapies targeting CSCs in HCC are based on CSC-specific molecular markers. However, almost all identified stem cell markers are not unequivocally exclusive CSC markers for HCC; in other words, they are also shared with normal stem cells. Second, the existence of intertumor, intratumor, and CSC heterogeneity is a daunting challenge in the development of immunotherapy targeting HCC CSCs 23, 178. Additionally, several studies have demonstrated that the HCC CSCs are plastic and can be converted from tumor cells without a stem phenotype, which can be induced by virus infection, crosstalk between CSCs and tumor cells, hypoxia stimulation, and conventional therapies 76, 77, 106, 179, 180. This plasticity and instability of the CSC phenotype in HCC is a major obstacle for effective immunotherapy targeting CSCs. Considering that CSCs are a rare subpopulation in tumor tissue, targeted CSC therapy alone is presumed to be inadequate for the effective elimination of tumors. Thus, the combination of CSC-targeted immunotherapy with currently used cancer therapies, such as chemotherapy, radiation therapy, antiangiogenic therapy, and checkpoint inhibitors, may effectively eradicate HCC tumors. Moreover, the success of the IMbrave150 trial in advanced HCC patients has illustrated the importance and necessity of combined therapy.

Finally, we think that the most attractive research prospects focused on CSC-targeted immunotherapy in HCC mainly include the following: a) the identification of unequivocal CSC-specific molecular markers through multiomics analyses, such as the combination of proteomics and single-cell analysis; b) dissection of the complex mechanisms of the crosstalk between CSCs and immune cells; and c) validation of the effects of combinatorial treatments in future preclinical and clinical trials, such as DC vaccination (loaded with a mixed CSC and non-CSC special antigens) in combination with checkpoint inhibitors, CAR-T/TCR-T therapy in combination with antiangiogenic therapy, anti-CD47 antibody combined with CAR-T, CAR-T combined NK cell-based cancer immunotherapies, and so on. In conclusion, based on the heterogeneity, plasticity and scarcity of HCC CSCs, it is suggested that combinatorial treatments will be more efficacious than anti-CSC treatment alone. Overall, future immunotherapy should serve as a model for combined therapy.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82074208, 81472346 and 81802355), and Zhejiang Natural Science Foundation (LY20H160033).

Consent for publication

All authors agreed to submit for consideration for publication in this journal.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singal AG, Lampertico P, Nahon P. Epidemiology and surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma: New trends. J Hepatol. 2020;72:250–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith RA, Andrews KS, Brooks D, Fedewa SA, Manassaram-Baptiste D, Saslow D. et al. Cancer screening in the United States, 2019: A review of current American Cancer Society guidelines and current issues in cancer screening. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:184–210. doi: 10.3322/caac.21557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forner A, Reig M, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2018;391:1301–14. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schulte LA, López-Gil JC, Sainz B Jr, Hermann PC. The Cancer Stem Cell in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers. 2020;12:684. doi: 10.3390/cancers12030684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruiu R, Tarone L, Rolih V, Barutello G, Bolli E, Riccardo F. et al. Cancer stem cell immunology and immunotherapy: Harnessing the immune system against cancer's source. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2019;164:119–88. doi: 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2019.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greten TF, Lai CW, Li G, Staveley-O'Carroll KF. Targeted and Immune-Based Therapies for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:510–24. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.09.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ribas A, Wolchok JD. Cancer immunotherapy using checkpoint blockade. Science. 2018;359:1350–5. doi: 10.1126/science.aar4060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Z, Wu X. Study and analysis of antitumor resistance mechanism of PD1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint blocker. Cancer Med. 2020;9:8086–8121. doi: 10.1002/cam4.3410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Craig AJ, von Felden J, Garcia-Lezana T, Sarcognato S, Villanueva A. Tumour evolution in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17:139–52. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0229-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lapidot T, Sirard C, Vormoor J, Murdoch B, Hoang T, Caceres-Cortes J. et al. A cell initiating human acute myeloid leukaemia after transplantation into SCID mice. Nature. 1994;367:645–8. doi: 10.1038/367645a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haraguchi N, Inoue H, Tanaka F, Mimori K, Utsunomiya T, Sasaki A. et al. Cancer stem cells in human gastrointestinal cancers. Human cell. 2006;19:24–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-0774.2005.00004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haraguchi N, Utsunomiya T, Inoue H, Tanaka F, Mimori K, Barnard GF. et al. Characterization of a side population of cancer cells from human gastrointestinal system. Stem cells. 2006;24:506–13. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chiba T, Kita K, Zheng YW, Yokosuka O, Saisho H, Iwama A. et al. Side population purified from hepatocellular carcinoma cells harbors cancer stem cell-like properties. Hepatology. 2006;44:240–51. doi: 10.1002/hep.21227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu YC, Yeh CT, Lin KH. Cancer Stem Cell Functions in Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Comprehensive Therapeutic Strategies. Cells. 2020;9:1331. doi: 10.3390/cells9061331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou G, Wilson G, George J, Qiao L. Targeting cancer stem cells as a therapeutic approach in liver cancer. Curr Gene Ther. 2015;15:161–70. doi: 10.2174/1566523214666141224095938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fan ST, Yang ZF, Ho DW, Ng MN, Yu WC, Wong J. Prediction of posthepatectomy recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma by circulating cancer stem cells: a prospective study. Ann Surg. 2011;254:569–76. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182300a1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang XR, Xu Y, Yu B, Zhou J, Li JC, Qiu SJ. et al. CD24 is a novel predictor for poor prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma after surgery. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5518–27. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ji J, Wang XW. Clinical implications of cancer stem cell biology in hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Oncol. 2012;39:461–72. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2012.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dai XM, Yang SL, Zheng XM, Chen GG, Chen J, Zhang T. CD133 expression and α-fetoprotein levels define novel prognostic subtypes of HBV-associated hepatocellular carcinoma: A long-term follow-up analysis. Oncol Lett. 2018;15:2985–91. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.7704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dai XM, Huang T, Yang SL, Zheng XM, Chen GG, Zhang T. Peritumoral EpCAM Is an Independent Prognostic Marker after Curative Resection of HBV-Related Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Dis Markers. 2017;2017:8495326. doi: 10.1155/2017/8495326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ho DW, Tsui YM, Sze KM, Chan LK, Cheung TT, Lee E. et al. Single-cell transcriptomics reveals the landscape of intra-tumoral heterogeneity and stemness-related subpopulations in liver cancer. Cancer Lett. 2019;459:176–85. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clarke MF. Clinical and Therapeutic Implications of Cancer Stem Cells. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:2237–45. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1804280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zheng H, Pomyen Y, Hernandez MO, Li C, Livak F, Tang W. et al. Single-cell analysis reveals cancer stem cell heterogeneity in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2018;68:127–40. doi: 10.1002/hep.29778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chan LH, Luk ST, Ma S. Turning hepatic cancer stem cells inside out-a deeper understanding through multiple perspectives. Mol Cells. 2015;38:202–9. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2015.2356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mohme M, Riethdorf S, Pantel K. Circulating and disseminated tumour cells - mechanisms of immune surveillance and escape. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017;14:155–67. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malanchi I, Santamaria-Martínez A, Susanto E, Peng H, Lehr HA, Delaloye JF. et al. Interactions between cancer stem cells and their niche govern metastatic colonization. Nature. 2011;481:85–9. doi: 10.1038/nature10694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yao H, Liu N, Lin MC, Zheng J. Positive feedback loop between cancer stem cells and angiogenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2016;379:213–9. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oishi N, Yamashita T, Kaneko S. Molecular biology of liver cancer stem cells. Liver cancer. 2014;3:71–84. doi: 10.1159/000343863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pez F, Lopez A, Kim M, Wands JR, Caron de Fromentel C, Merle P. Wnt signaling and hepatocarcinogenesis: molecular targets for the development of innovative anticancer drugs. J Hepatol. 2013;59:1107–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clara JA, Monge C, Yang Y, Takebe N. Targeting signalling pathways and the immune microenvironment of cancer stem cells - a clinical update. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2020;17:204–32. doi: 10.1038/s41571-019-0293-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sia D, Jiao Y, Martinez-Quetglas I, Kuchuk O, Villacorta-Martin C, Castro de Moura M. et al. Identification of an Immune-specific Class of Hepatocellular Carcinoma, Based on Molecular Features. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:812–26. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spranger S, Bao R, Gajewski TF. Melanoma-intrinsic β-catenin signalling prevents anti-tumour immunity. Nature. 2015;523:231–5. doi: 10.1038/nature14404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang Y, Kitisin K, Jogunoori W, Li C, Deng CX, Mueller SC. et al. Progenitor/stem cells give rise to liver cancer due to aberrant TGF-beta and IL-6 signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2445–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705395105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dituri F, Mancarella S, Cigliano A, Chieti A, Giannelli G. TGF-beta as Multifaceted Orchestrator in HCC Progression: Signaling, EMT, Immune Microenvironment, and Novel Therapeutic Perspectives. Semin Liver Dis. 2019;39:53–69. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1676121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jones SA, Jenkins BJ. Recent insights into targeting the IL-6 cytokine family in inflammatory diseases and cancer. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018;18:773–89. doi: 10.1038/s41577-018-0066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Radtke F, Fasnacht N, Macdonald HR. Notch signaling in the immune system. Immunity. 2010;32:14–27. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Balli D, Rech AJ, Stanger BZ, Vonderheide RH. Immune Cytolytic Activity Stratifies Molecular Subsets of Human Pancreatic Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:3129–38. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shen Q, Cohen B, Zheng W, Rahbar R, Martin B, Murakami K. et al. Notch Shapes the Innate Immunophenotype in Breast Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2017;7:1320–35. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang G, Lu X, Dey P, Deng P, Wu CC, Jiang S. et al. Targeting YAP-Dependent MDSC Infiltration Impairs Tumor Progression. Cancer Discov. 2016;6:80–95. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lu L, Jiang J, Zhan M, Zhang H, Wang QT, Sun SN, Targeting Neoantigens in Hepatocellular Carcinoma for Immunotherapy: A Futile Strategy? Hepatology. 2020. DOI: 10.1002/hep.31279. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Di Tomaso T, Mazzoleni S, Wang E, Sovena G, Clavenna D, Franzin A. et al. Immunobiological characterization of cancer stem cells isolated from glioblastoma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:800–13. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Busse A, Letsch A, Fusi A, Nonnenmacher A, Stather D, Ochsenreither S. et al. Characterization of small spheres derived from various solid tumor cell lines: are they suitable targets for T cells? Clin Exp Metastasis. 2013;30:781–91. doi: 10.1007/s10585-013-9578-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bao B, Ahmad A, Azmi AS, Ali S, Sarkar FH. Overview of cancer stem cells (CSCs) and mechanisms of their regulation: implications for cancer therapy. Curr Protoc Pharmacol. 2013. Chapter 14: Unit 14.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Cioffi M, Trabulo S, Hidalgo M, Costello E, Greenhalf W, Erkan M. et al. Inhibition of CD47 Effectively Targets Pancreatic Cancer Stem Cells via Dual Mechanisms. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:2325–37. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee TK, Cheung VC, Lu P, Lau EY, Ma S, Tang KH. et al. Blockade of CD47-mediated cathepsin S/protease-activated receptor 2 signaling provides a therapeutic target for hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2014;60:179–91. doi: 10.1002/hep.27070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lo J, Lau EY, Ching RH, Cheng BY, Ma MK, Ng IO. et al. Nuclear factor kappa B-mediated CD47 up-regulation promotes sorafenib resistance and its blockade synergizes the effect of sorafenib in hepatocellular carcinoma in mice. Hepatology. 2015;62:534–45. doi: 10.1002/hep.27859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen J, Zheng DX, Yu XJ, Sun HW, Xu YT, Zhang YJ. et al. Macrophages induce CD47 upregulation via IL-6 and correlate with poor survival in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Oncoimmunology. 2019;8:e1652540. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2019.1652540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hsu JM, Xia W, Hsu YH, Chan LC, Yu WH, Cha JH. et al. STT3-dependent PD-L1 accumulation on cancer stem cells promotes immune evasion. Nat Commun. 2018;9:1908. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04313-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee Y, Shin JH, Longmire M, Wang H, Kohrt HE, Chang HY. et al. CD44+ Cells in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma Suppress T-Cell-Mediated Immunity by Selective Constitutive and Inducible Expression of PD-L1. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:3571–81. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dong P, Xiong Y, Yue J, Hanley SJB, Watari H. Tumor-Intrinsic PD-L1 Signaling in Cancer Initiation, Development and Treatment: Beyond Immune Evasion. Frontiers in oncology. 2018;8:386. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bangaru S, Marrero JA, Singal AG. Review article: new therapeutic interventions for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;51:78–89. doi: 10.1111/apt.15573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Finn RS, Zhu AX. Evolution of Systemic Therapy for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Hepatology. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 55.Ali N, Allam H, May R, Sureban SM, Bronze MS, Bader T. et al. Hepatitis C virus-induced cancer stem cell-like signatures in cell culture and murine tumor xenografts. J Virol. 2011;85:12292–303. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05920-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kwon YC, Bose SK, Steele R, Meyer K, Di Bisceglie AM, Ray RB. et al. Promotion of Cancer Stem-Like Cell Properties in Hepatitis C Virus-Infected Hepatocytes. J Virol. 2015;89:11549–56. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01946-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mani SKK, Andrisani O. Hepatitis B Virus-Associated Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Hepatic Cancer Stem Cells. Genes. 2018;9:137. doi: 10.3390/genes9030137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lin X, Zuo S, Luo R, Li Y, Yu G, Zou Y. et al. HBX-induced miR-5188 impairs FOXO1 to stimulate β-catenin nuclear translocation and promotes tumor stemness in hepatocellular carcinoma. Theranostics. 2019;9:7583–98. doi: 10.7150/thno.37717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ng KY, Chai S, Tong M, Guan XY, Lin CH, Ching YP. et al. C-terminal truncated hepatitis B virus X protein promotes hepatocellular carcinogenesis through induction of cancer and stem cell-like properties. Oncotarget. 2016;7:24005–17. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang C, Yang W, Yan HX, Luo T, Zhang J, Tang L. et al. Hepatitis B virus X (HBx) induces tumorigenicity of hepatic progenitor cells in 3,5-diethoxycarbonyl-1,4-dihydrocollidine-treated HBx transgenic mice. Hepatology. 2012;55:108–20. doi: 10.1002/hep.24675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chang TS, Chen CL, Wu YC, Liu JJ, Kuo YC, Lee KF. et al. Inflammation Promotes Expression of Stemness-Related Properties in HBV-Related Hepatocellular Carcinoma. PloS One. 2016;11:e0149897. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chang TS, Wu YC, Chi CC, Su WC, Chang PJ, Lee KF. et al. Activation of IL6/IGFIR confers poor prognosis of HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma through induction of OCT4/NANOG expression. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:201–10. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yang JD, Hainaut P, Gores GJ, Amadou A, Plymoth A, Roberts LR. A global view of hepatocellular carcinoma: trends, risk, prevention and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16:589–604. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0186-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xu M, Luo J. Alcohol and Cancer Stem Cells. Cancers. 2017. 9 9: 158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 65.Machida K, Tsukamoto H, Mkrtchyan H, Duan L, Dynnyk A, Liu HM. et al. Toll-like receptor 4 mediates synergism between alcohol and HCV in hepatic oncogenesis involving stem cell marker Nanog. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:1548–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807390106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Machida K, Feldman DE, Tsukamoto H. TLR4-dependent tumor-initiating stem cell-like cells (TICs) in alcohol-associated hepatocellular carcinogenesis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2015;815:131–44. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-09614-8_8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ambade A, Satishchandran A, Szabo G. Alcoholic hepatitis accelerates early hepatobiliary cancer by increasing stemness and miR-122-mediated HIF-1α activation. Sci Rep. 2016;6:21340. doi: 10.1038/srep21340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Qin XY, Su T, Yu W, Kojima S. Lipid desaturation-associated endoplasmic reticulum stress regulates MYCN gene expression in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11:66. doi: 10.1038/s41419-020-2257-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chong LW, Chou RH, Liao CC, Lee TF, Lin Y, Yang KC. et al. Saturated fatty acid induces cancer stem cell-like properties in human hepatoma cells. Cell Mol Biol. 2015;61:85–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ma C, Kesarwala AH, Eggert T, Medina-Echeverz J, Kleiner DE, Jin P. et al. NAFLD causes selective CD4(+) T lymphocyte loss and promotes hepatocarcinogenesis. Nature. 2016;531:253–7. doi: 10.1038/nature16969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Anstee QM, Reeves HL, Kotsiliti E, Govaere O, Heikenwalder M. From NASH to HCC: current concepts and future challenges. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16:411–28. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0145-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shalapour S, Lin XJ, Bastian IN, Brain J, Burt AD, Aksenov AA. et al. Inflammation-induced IgA+ cells dismantle anti-liver cancer immunity. Nature. 2017;551:340–5. doi: 10.1038/nature24302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bhattacharjee J, Kirby M, Softic S, Miles L, Salazar-Gonzalez RM, Shivakumar P. et al. Hepatic Natural Killer T-cell and CD8+ T-cell Signatures in Mice with Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Hepatol Commun. 2017;1:299–310. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sutti S, Albano E. Adaptive immunity: an emerging player in the progression of NAFLD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17:81–92. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0210-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lin D, Wu J. Hypoxia inducible factor in hepatocellular carcinoma: A therapeutic target. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:12171–8. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i42.12171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ye LY, Chen W, Bai XL, Xu XY, Zhang Q, Xia XF. et al. Hypoxia-Induced Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Induces an Immunosuppressive Tumor Microenvironment to Promote Metastasis. Cancer Res. 2016;76:818–30. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yang SL, Ren QG, Zhang T, Pan X, Wen L, Hu JL. et al. Hepatitis B virus X protein and hypoxia-inducible factor-1α stimulate Notch gene expression in liver cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2017;37:348–56. doi: 10.3892/or.2016.5211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Peng JM, Bera R, Chiou CY, Yu MC, Chen TC, Chen CW. et al. Actin cytoskeleton remodeling drives epithelial-mesenchymal transition for hepatoma invasion and metastasis in mice. Hepatology. 2018;67:2226–43. doi: 10.1002/hep.29678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Huang D, Cao L, Xiao L, Song JX, Zhang YJ, Zheng P. et al. Hypoxia induces actin cytoskeleton remodeling by regulating the binding of CAPZA1 to F-actin via PIP2 to drive EMT in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2019;448:117–27. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhang J, Zhang Q, Lou Y, Fu Q, Chen Q, Wei T. et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α/interleukin-1β signaling enhances hepatoma epithelial-mesenchymal transition through macrophages in a hypoxic-inflammatory microenvironment. Hepatology. 2018;67:1872–89. doi: 10.1002/hep.29681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nishida N, Kudo M. Immunological Microenvironment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Its Clinical Implication. Oncology. 2017;92(Suppl 1):40–9. doi: 10.1159/000451015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Xiong XX, Qiu XY, Hu DX, Chen XQ. Advances in Hypoxia-Mediated Mechanisms in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Mol Pharmacol. 2017;92:246–55. doi: 10.1124/mol.116.107706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Elaimy AL, Mercurio AM. Convergence of VEGF and YAP/TAZ signaling: Implications for angiogenesis and cancer biology. Sci Signal. 2018;11:eaau1165. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aau1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Beck B, Driessens G, Goossens S, Youssef KK, Kuchnio A, Caauwe A. et al. A vascular niche and a VEGF-Nrp1 loop regulate the initiation and stemness of skin tumours. Nature. 2011;478:399–403. doi: 10.1038/nature10525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tang KH, Ma S, Lee TK, Chan YP, Kwan PS, Tong CM. et al. CD133(+) liver tumor-initiating cells promote tumor angiogenesis, growth, and self-renewal through neurotensin/interleukin-8/CXCL1 signaling. Hepatology. 2012;55:807–20. doi: 10.1002/hep.24739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Liu K, Hao M, Ouyang Y, Zheng J, Chen D. CD133(+) cancer stem cells promoted by VEGF accelerate the recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma. Scie Rep. 2017;7:41499. doi: 10.1038/srep41499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rahma OE, Hodi FS. The Intersection between Tumor Angiogenesis and Immune Suppression. Cli Cancer Res. 2019;25:5449–57. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Voron T, Colussi O, Marcheteau E, Pernot S, Nizard M, Pointet AL. et al. VEGF-A modulates expression of inhibitory checkpoints on CD8+ T cells in tumors. J Exp Med. 2015;212:139–48. doi: 10.1084/jem.20140559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Petrillo M, Patella F, Pesapane F, Suter MB, Ierardi AM, Angileri SA. et al. Hypoxia and tumor angiogenesis in the era of hepatocellular carcinoma transarterial loco-regional treatments. Future Oncol. 2018;14:2957–67. doi: 10.2217/fon-2017-0739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ping YF, Bian XW. Consice review: Contribution of cancer stem cells to neovascularization. Stem cells. 2011;29:888–94. doi: 10.1002/stem.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kise K, Kinugasa-Katayama Y, Takakura N. Tumor microenvironment for cancer stem cells. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2016;99:197–205. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2015.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Plaks V, Kong N, Werb Z. The cancer stem cell niche: how essential is the niche in regulating stemness of tumor cells? Cell stem cell. 2015;16:225–38. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.DeNardo DG, Ruffell B. Macrophages as regulators of tumour immunity and immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2019;19:369–82. doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0127-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Pathria P, Louis TL, Varner JA. Targeting Tumor-Associated Macrophages in Cancer. Trends Immunol. 2019;40:310–27. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2019.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Muppala S. Significance of the Tumor Microenvironment in Liver Cancer Progression. Crit Rev Oncog. 2020;25:1–9. doi: 10.1615/CritRevOncog.2020034987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Müller L, Tunger A, Plesca I, Wehner R, Temme A, Westphal D. et al. Bidirectional Crosstalk Between Cancer Stem Cells and Immune Cell Subsets. Front Immunol. 2020;11:140. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Nappo G, Handle F, Santer FR, McNeill RV, Seed RI, Collins AT. et al. The immunosuppressive cytokine interleukin-4 increases the clonogenic potential of prostate stem-like cells by activation of STAT6 signalling. Oncogenesis. 2017;6:e342. doi: 10.1038/oncsis.2017.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Zhou W, Ke SQ, Huang Z, Flavahan W, Fang X, Paul J. et al. Periostin secreted by glioblastoma stem cells recruits M2 tumour-associated macrophages and promotes malignant growth. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17:170–82. doi: 10.1038/ncb3090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wan S, Zhao E, Kryczek I, Vatan L, Sadovskaya A, Ludema G. et al. Tumor-associated macrophages produce interleukin 6 and signal via STAT3 to promote expansion of human hepatocellular carcinoma stem cells. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:1393–404. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.08.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Fan QM, Jing YY, Yu GF, Kou XR, Ye F, Gao L. et al. Tumor-associated macrophages promote cancer stem cell-like properties via transforming growth factor-beta1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2014;352:160–8. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Dianat-Moghadam H, Rokni M, Marofi F, Panahi Y, Yousefi M. Natural killer cell-based immunotherapy: From transplantation toward targeting cancer stem cells. J Cell Physiol. 2018;234:259–73. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Cheung PF, Yip CW, Wong NC, Fong DY, Ng LW, Wan AM. et al. Granulin-epithelin precursor renders hepatocellular carcinoma cells resistant to natural killer cytotoxicity. Cancer immunol Res. 2014;2:1209–19. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Cheung PF, Cheng CK, Wong NC, Ho JC, Yip CW, Lui VC. et al. Granulin-epithelin precursor is an oncofetal protein defining hepatic cancer stem cells. PloS One. 2011;6:e28246. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Tanriover G, Aytac G. Mutualistic Effects of the Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells and Cancer Stem Cells in the Tumor Microenvironment. Crit Rev Oncog. 2019;24:61–7. doi: 10.1615/CritRevOncog.2018029436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kuroda H, Mabuchi S, Yokoi E, Komura N, Kozasa K, Matsumoto Y. et al. Prostaglandin E2 produced by myeloid-derived suppressive cells induces cancer stem cells in uterine cervical cancer. Oncotarget. 2018;9:36317–30. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.26347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Peng D, Tanikawa T, Li W, Zhao L, Vatan L, Szeliga W. et al. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells Endow Stem-like Qualities to Breast Cancer Cells through IL6/STAT3 and NO/NOTCH Cross-talk Signaling. Cancer Res. 2016;76:3156–65. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-2528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Sica A, Porta C, Amadori A, Pastò A. Tumor-associated myeloid cells as guiding forces of cancer cell stemness. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2017;66:1025–36. doi: 10.1007/s00262-017-1997-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Otvos B, Silver DJ, Mulkearns-Hubert EE, Alvarado AG, Turaga SM, Sorensen MD. et al. Cancer Stem Cell-Secreted Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor Stimulates Myeloid Derived Suppressor Cell Function and Facilitates Glioblastoma Immune Evasion. Stem Cells. 2016;34:2026–39. doi: 10.1002/stem.2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Hoechst B, Voigtlaender T, Ormandy L, Gamrekelashvili J, Zhao F, Wedemeyer H. et al. Myeloid derived suppressor cells inhibit natural killer cells in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma via the NKp30 receptor. Hepatology. 2009;50:799–807. doi: 10.1002/hep.23054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Chiu DK, Xu IM, Lai RK, Tse AP, Wei LL, Koh HY. et al. Hypoxia induces myeloid-derived suppressor cell recruitment to hepatocellular carcinoma through chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 26. Hepatology. 2016;64:797–813. doi: 10.1002/hep.28655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Xu M, Zhao Z, Song J, Lan X, Lu S, Chen M. et al. Interactions between interleukin-6 and myeloid-derived suppressor cells drive the chemoresistant phenotype of hepatocellular cancer. Exp Cell Res. 2017;351:142–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2017.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Lu C, Rong D, Zhang B, Zheng W, Wang X, Chen Z. et al. Current perspectives on the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment in hepatocellular carcinoma: challenges and opportunities. Mol Cancer. 2019;18:130. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-1047-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Chia WK, Ali R, Toh HC. Aspirin as adjuvant therapy for colorectal cancer-reinterpreting paradigms. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2012;9:561–70. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Llovet JM, Montal R, Sia D, Finn RS. Molecular therapies and precision medicine for hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15:599–616. doi: 10.1038/s41571-018-0073-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Weiner GJ. Building better monoclonal antibody-based therapeutics. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15:361–70. doi: 10.1038/nrc3930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Labrijn AF, Janmaat ML, Reichert JM, Parren P. Bispecific antibodies: a mechanistic review of the pipeline. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2019;18:585–608. doi: 10.1038/s41573-019-0028-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Sun YF, Xu Y, Yang XR, Guo W, Zhang X, Qiu SJ. et al. Circulating stem cell-like epithelial cell adhesion molecule-positive tumor cells indicate poor prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma after curative resection. Hepatology. 2013;57:1458–68. doi: 10.1002/hep.26151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Yamashita T, Budhu A, Forgues M, Wang XW. Activation of hepatic stem cell marker EpCAM by Wnt-beta-catenin signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2007;67:10831–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Zhang P, Shi B, Gao H, Jiang H, Kong J, Yan J. et al. An EpCAM/CD3 bispecific antibody efficiently eliminates hepatocellular carcinoma cells with limited galectin-1 expression. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2014;63:121–32. doi: 10.1007/s00262-013-1497-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Frampton JE. Catumaxomab: in malignant ascites. Drugs. 2012;72:1399–410. doi: 10.2165/11209040-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Wimberger P, Gilet H, Gonschior AK, Heiss MM, Moehler M, Oskay-Oezcelik G. et al. Deterioration in quality of life (QoL) in patients with malignant ascites: results from a phase II/III study comparing paracentesis plus catumaxomab with paracentesis alone. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:1979–85. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Baumann K, Pfisterer J, Wimberger P, Burchardi N, Kurzeder C, du Bois A. et al. Intraperitoneal treatment with the trifunctional bispecific antibody Catumaxomab in patients with platinum-resistant epithelial ovarian cancer: a phase IIa study of the AGO Study Group. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;123:27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Jäger M, Schoberth A, Ruf P, Hess J, Hennig M, Schmalfeldt B. et al. Immunomonitoring results of a phase II/III study of malignant ascites patients treated with the trifunctional antibody catumaxomab (anti-EpCAM x anti-CD3) Cancer Res. 2012;72:24–32. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Knödler M, Körfer J, Kunzmann V, Trojan J, Daum S, Schenk M. et al. Randomised phase II trial to investigate catumaxomab (anti-EpCAM × anti-CD3) for treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis in patients with gastric cancer. Br J Cancer. 2018;119:296–302. doi: 10.1038/s41416-018-0150-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Feng M, Jiang W, Kim BYS, Zhang CC, Fu YX, Weissman IL. Phagocytosis checkpoints as new targets for cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2019;19:568–86. doi: 10.1038/s41568-019-0183-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Xiao Z, Chung H, Banan B, Manning PT, Ott KC, Lin S. et al. Antibody mediated therapy targeting CD47 inhibits tumor progression of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2015;360:302–9. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.02.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Lo J, Lau EY, So FT, Lu P, Chan VS, Cheung VC. et al. Anti-CD47 antibody suppresses tumour growth and augments the effect of chemotherapy treatment in hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int. 2016;36:737–45. doi: 10.1111/liv.12963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Logtenberg MEW, Scheeren FA, Schumacher TN. The CD47-SIRPα Immune Checkpoint. Immunity. 2020;52:742–52. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Sikic BI, Lakhani N, Patnaik A, Shah SA, Chandana SR, Rasco D. et al. First-in-Human, First-in-Class Phase I Trial of the Anti-CD47 Antibody Hu5F9-G4 in Patients With Advanced Cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:946–53. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.02018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Advani R, Flinn I, Popplewell L, Forero A, Bartlett NL, Ghosh N. et al. CD47 Blockade by Hu5F9-G4 and Rituximab in Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1711–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1807315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Huang J, Li C, Wang Y, Lv H, Guo Y, Dai H. et al. Cytokine-induced killer (CIK) cells bound with anti-CD3/anti-CD133 bispecific antibodies target CD133(high) cancer stem cells in vitro and in vivo. Clin Immunol. 2013;149:156–68. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Wang L, Su W, Liu Z, Zhou M, Chen S, Chen Y. et al. CD44 antibody-targeted liposomal nanoparticles for molecular imaging and therapy of hepatocellular carcinoma. Biomaterials. 2012;33:5107–14. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.03.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Menke-van der Houven van Oordt CW, Gomez-Roca C, van Herpen C, Coveler AL, Mahalingam D, Verheul HM. et al. First-in-human phase I clinical trial of RG7356, an anti-CD44 humanized antibody, in patients with advanced, CD44-expressing solid tumors. Oncotarget. 2016;7:80046–58. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Ma Z, He H, Sun F, Xu Y, Huang X, Ma Y. et al. Selective targeted delivery of doxorubicin via conjugating to anti-CD24 antibody results in enhanced antitumor potency for hepatocellular carcinoma both in vitro and in vivo. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2017;143:1929–40. doi: 10.1007/s00432-017-2436-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Sun F, Wang T, Jiang J, Wang Y, Ma Z, Li Z. et al. Engineering a high-affinity humanized anti-CD24 antibody to target hepatocellular carcinoma by a novel CDR grafting design. Oncotarget. 2017;8:51238–52. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.PD-1 inhibitor becomes "breakthrough therapy". Cancer Discov. 2013; 3: Of14. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 137.El-Khoueiry AB, Sangro B, Yau T, Crocenzi TS, Kudo M, Hsu C. et al. Nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (CheckMate 040): an open-label, non-comparative, phase 1/2 dose escalation and expansion trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2492–502. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31046-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Zhu AX, Finn RS, Edeline J, Cattan S, Ogasawara S, Palmer D. et al. Pembrolizumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma previously treated with sorafenib (KEYNOTE-224): a non-randomised, open-label phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:940–52. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30351-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Palmer DH. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2498. author reply -9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Kudo M, Finn RS, Qin S, Han KH, Ikeda K, Piscaglia F. et al. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018;391:1163–73. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30207-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Bruix J, Qin S, Merle P, Granito A, Huang YH, Bodoky G. et al. Regorafenib for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who progressed on sorafenib treatment (RESORCE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389:56–66. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32453-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Abou-Alfa GK, Meyer T, Cheng AL, El-Khoueiry AB, Rimassa L, Ryoo BY. et al. Cabozantinib in Patients with Advanced and Progressing Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:54–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1717002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Zhu AX, Park JO, Ryoo BY, Yen CJ, Poon R, Pastorelli D. et al. Ramucirumab versus placebo as second-line treatment in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma following first-line therapy with sorafenib (REACH): a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:859–70. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Zhu AX, Kang YK, Yen CJ, Finn RS, Galle PR, Llovet JM. et al. Ramucirumab after sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma and increased α-fetoprotein concentrations (REACH-2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:282–96. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30937-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Bhoori S, Mazzaferro V. Combined immunotherapy and VEGF-antagonist in hepatocellular carcinoma: a step forward. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:740–1. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30211-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, Galle PR, Ducreux M, Kim TY. et al. Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab in Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1894–905. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1915745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Yang X, Wang D, Lin J, Yang X, Zhao H. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:e412. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30430-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Fukuoka S, Hara H, Takahashi N, Kojima T, Kawazoe A, Asayama M. et al. Regorafenib Plus Nivolumab in Patients With Advanced Gastric or Colorectal Cancer: An Open-Label, Dose-Escalation, and Dose-Expansion Phase Ib Trial (REGONIVO, EPOC1603) J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:2053–61. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.03296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Singh AK, McGuirk JP. CAR T cells: continuation in a revolution of immunotherapy. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:e168–e78. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30823-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Sadelain M. CD19 CAR T Cells. Cell. 2017;171:1471. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Dal Bo M, De Mattia E, Baboci L, Mezzalira S, Cecchin E, Assaraf YG. et al. New insights into the pharmacological, immunological, and CAR-T-cell approaches in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Drug Resist Updat. 2020;51:100702. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2020.100702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Hendrickson PG, Olson M, Luetkens T, Weston S, Han T, Atanackovic D. et al. The promise of adoptive cellular immunotherapies in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncoimmunology. 2020;9:1673129. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2019.1673129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Shi D, Shi Y, Kaseb AO, Qi X, Zhang Y, Chi J. et al. Chimeric Antigen Receptor-Glypican-3 T-Cell Therapy for Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Results of Phase I Trials. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:3979–3989. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-3259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Wang Y, Chen M, Wu Z, Tong C, Dai H, Guo Y. et al. CD133-directed CAR T cells for advanced metastasis malignancies: A phase I trial. Oncoimmunology. 2018;7:e1440169. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2018.1440169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Zhou Y, Wen P, Li M, Li Y, Li XA. Construction of chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells targeting EpCAM and assessment of their anti-tumor effect on cancer cells. Mol Med Rep. 2019;20:2355–64. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2019.10460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Deng Z, Wu Y, Ma W, Zhang S, Zhang YQ. Adoptive T-cell therapy of prostate cancer targeting the cancer stem cell antigen EpCAM. BMC Immunol. 2015;16:1. doi: 10.1186/s12865-014-0064-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Ang WX, Li Z, Chi Z, Du SH, Chen C, Tay JC. et al. Intraperitoneal immunotherapy with T cells stably and transiently expressing anti-EpCAM CAR in xenograft models of peritoneal carcinomatosis. Oncotarget. 2017;8:13545–59. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Zhang BL, Li D, Gong YL, Huang Y, Qin DY, Jiang L. et al. Preclinical Evaluation of Chimeric Antigen Receptor-Modified T Cells Specific to Epithelial Cell Adhesion Molecule for Treating Colorectal Cancer. Hum Gene Ther. 2019;30:402–12. doi: 10.1089/hum.2018.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Bertoletti A, Brunetto M, Maini MK, Bonino F, Qasim W, Stauss H. T cell receptor-therapy in HBV-related hepatocellularcarcinoma. Oncoimmunology. 2015;4:e1008354. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1008354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Zhu W, Peng Y, Wang L, Hong Y, Jiang X, Li Q. et al. Identification of α-fetoprotein-specific T-cell receptors for hepatocellular carcinoma immunotherapy. Hepatology. 2018;68:574–89. doi: 10.1002/hep.29844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]