Abstract

Electron-based fragmentation methods have revolutionized biomolecular mass spectrometry, in particular native and top-down protein analysis. Here, we report the use of a new electromagnetostatic cell to perform electron capture dissociation (ECD) within a quadrupole/ion mobility/time-of-flight mass spectrometer. This cell was installed between the ion mobility and time-of-flight regions of the instrument, and fragmentation was fast enough to be compatible with mobility separation. The instrument was already fitted with electron transfer dissociation (ETD) between the quadrupole and mobility regions prior to modification. We show excellent fragmentation efficiency for denatured peptides and proteins without the need to trap ions in the gas phase. Additionally, we demonstrate native top-down backbone fragmentation of noncovalent protein complexes, leading to comparable sequence coverage to what was achieved using the instrument’s existing ETD capabilities. Limited collisional ion activation of the hemoglobin tetramer before ECD was reflected in the observed fragmentation pattern, and complementary ion mobility measurements prior to ECD provided orthogonal evidence of monomer unfolding within this complex. The approach demonstrated here provides a powerful platform for both top-down proteomics and mass spectrometry-based structural biology studies.

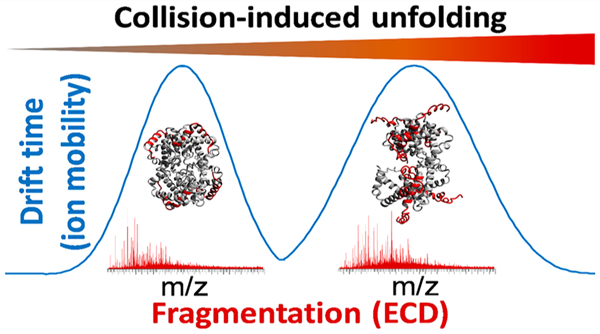

Graphical Abstract

Proteins are often considered the “work horses” of cells, and they perform many diverse roles, including signaling, transporting, catalyzing, providing structural stability, etc. Many proteins exist and operate within the cell as protein–protein complexes, held together by noncovalent interactions. Mass spectrometry (MS)-based techniques offer significant information for structural biology and biophysical/-therapeutic characterization and can rapidly identify point mutations that are known to affect the structure and function of certain proteins. Two paradigm-changing evolutions have appeared in recent years, i.e., top-down MS and native MS. In top-down approaches, no chemical or enzymatic digestion of proteins is performed prior to analysis via MS.1–3 This approach provides knowledge of the intact protein mass, allowing rapid identification of co-occurring proteoforms, improved de novo sequencing, and correlation of modifications, somewhat similar to long-read DNA sequencing.4,5 As MS technology has largely caught up with the requirements of top-down MS, this technology has matured immensely in the past decade.6–9 In a similar vein, native MS aims to preserve labile interactions in the gas phase, allowing direct mass measurement of noncovalent complexes. The main benefit in this case is the determination of complex stoichiometry, although these methods can also provide information on shape and stability.10–12 The combination of native MS with advanced fragmentation techniques used in top-down MS has been shown to result in a fragmentation pattern that can be related to the native protein structure, e.g., secondary structure, crystallographic B factor, or solvent accessibility.13–22

One important class of methods for protein ion activation in MS is based on the interaction of a multiply charged precursor cation with low-energy electrons, either emitted by a cathode or donated by a gas-phase radical anion. This is known as electron capture or electron transfer dissociation (ECD or ETD), respectively. Both of these methods have proven invaluable in the “native top-down” studies discussed above.16,23 While analytically powerful compared to the collision-induced dissociation (CID) of proteins, the low efficiency of fragmentation often necessitates lengthy accumulation of data to observe a sufficiently intense fragment ion signal. For ETD, additional experimental complications arise such as the optimal balancing of the protein/reagent ratio and reaction time24 as well as the need for polarity switching in parts of the instrument in order to mix reagent anions and protein cations in the reaction cell. In certain instruments, precursor cations need to be trapped for several (up to tens of) milliseconds to allow a sufficient interaction with reagent anions or an electron beam.

Recently, an electromagnetostatic (EMS) cell was developed and successfully mounted within several mass spectrometers, effectively acting as an ECD module.25–31 Here, we report research results of the implementation of the EMS cell into a Synapt G2-Si instrument for its effective use as a fragmentation tool for intact proteins and complexes. The modification was performed within the Triwave section of the instrument between the ion mobility (IM) and transfer cell. While ETD capabilities are already implemented in the G2-Si instrument, this is done in the trap cell before the IM cell (post-IM ETD would require an additional ion source and quadrupole as well as complex ion optics for mixing cations and anions in the transfer cell). As ECD occurs after IM separation, we were able to assess the use of the EMS cell for both efficient sequencing of denatured proteins and peptides as well as probing changes in the higher-order structure of noncovalent complexes. Using the EMS cell mitigated several of the challenges described in the previous paragraph; specifically, ECD fragmentation takes place fast enough that no trapping of the ions is needed, no polarity switching is required to induce fragmentation, and precursor ion intensity had little effect on fragmentation efficiency. Because ECD efficiency was independent of precursor intensity, we were able to couple online size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) with electrospray ionization (ESI), yielding impressive results in seconds. In contrast, manual protein desalting procedures often take minutes or hours depending on the approach used. We believe that the incorporation of this workflow would be particularly attractive for current users of native MS workflows for deeper structural characterization at analytical LC flow rates, particularly when sample amounts are not limited.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Materials and Sample Preparation.

Denatured MS analysis made use of Substance P (Sigma S6883), mellitin (Sigma M2272), and bovine ubiquitin (Sigma U6253), which were all analyzed at a concentration of 0.5 μM in 50% aqueous acetonitrile containing 0.2% formic acid. Native MS analysis made use of (i) yeast alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH, Sigma A7011) that was dissolved to a concentration of 1 mg/mL in H2O and (ii) 10 μL of whole blood that was diluted into 1 mL of H2O for the analysis of human hemoglobin (Hb). Subsequently, 5–10 μL of this solution was injected onto the analytical column.

Liquid Chromatography (LC).

An ACQUITY UPLC H-Class system (Waters, Milford, MA, USA) was directly coupled to the standard ESI interface of a Synapt G2-Si HDMS mass spectrometer (Waters, Wilmslow, UK). SEC was performed using a Protein BEH SEC column (200 Å, 1.7 μM, 2.1 mm × 150 mm). For native MS, the ADH and human Hb were eluted off the column using isocratic 100 mM aqueous ammonium acetate as the mobile phase flowing into the source region of the mass spectrometer at a flow rate of 100 μL/min.

Mass Spectrometry.

Mass spectrometry was performed using a modified Synapt G2-Si instrument with an electromagnetostatic ECD cell mounted between the exit of the ion mobility cell and the entrance of the transfer cell (see Figure 1). The instrument was operated in positive ion mode, and the capillary voltage was optimized between 1.75 and 2.50 kV. The cone voltage was optimized between 25 and 100 V for collision-induced unfolding experiments prior to ion mobility-ECD. The helium cell and ion mobility cell gas flows were optimized at 120 and 60 mL/min, respectively. The IM cell contained nitrogen pressurized to ∼2 mbar. The source temperature and desolvation temperature were set to 110 and 350 °C, respectively.

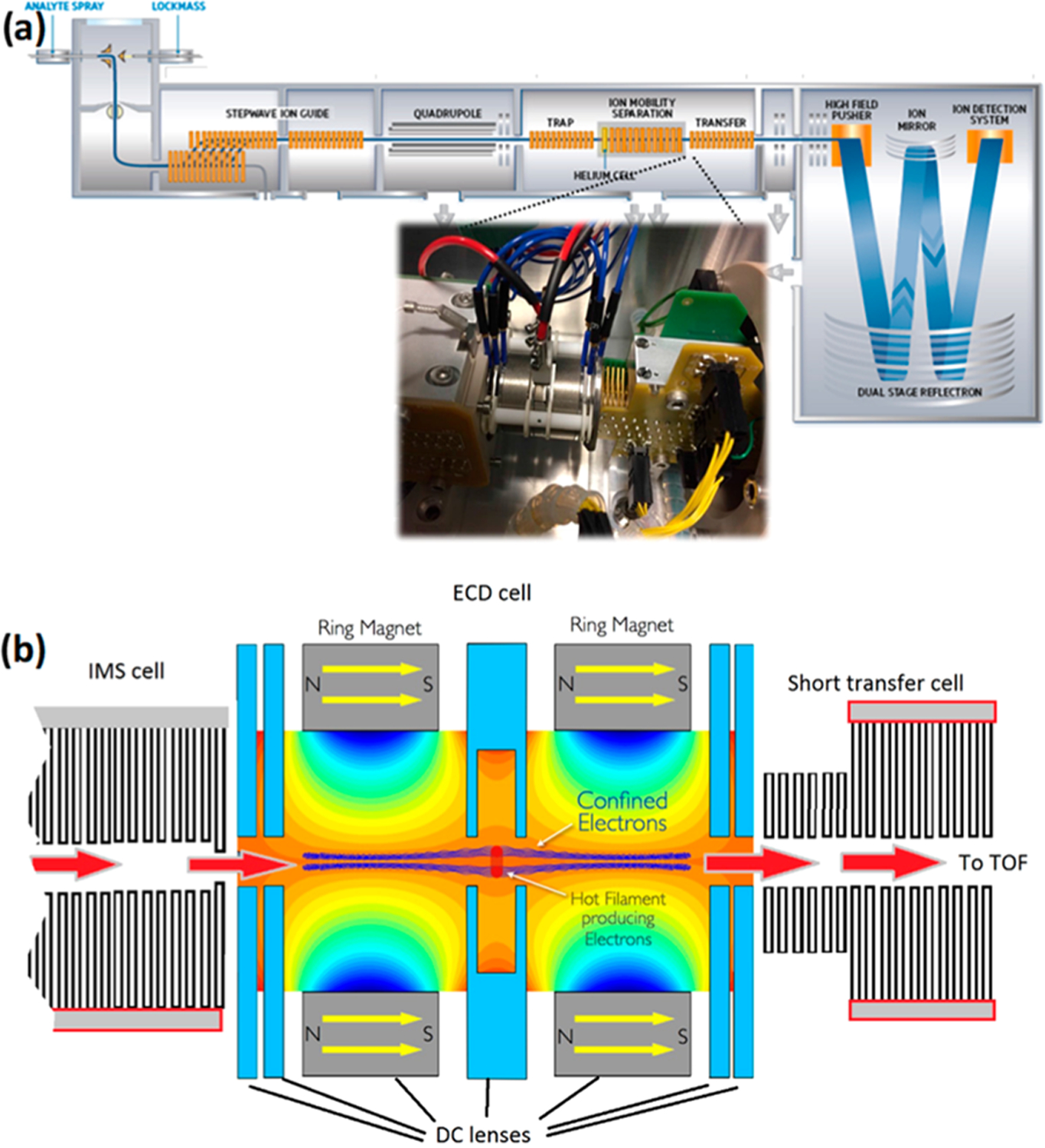

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic representation of the Synapt G2-Si instrument used in this study. The inset shows a photo of the EMS cell mounted between the IM and transfer cell. (b) Schematic of the EMS cell, highlighting the path of the protein ions (red arrows) and confined electrons (in blue).

The ECD cell comprises seven cylindrical electrostatic lenses tuned to transmit cations and their fragments as they are generated through the interaction with a low-energy (1 eV) electron cloud. The electrons are generated from a hot rhenium loop filament coated with ytrrium oxide that the precursor ions pass through. Two of the electrostatic lens elements are samarium–cobalt alloy ring magnets and are designed to entrain the electrons to the central axis, thus enabling much greater overlap between the ions and electrons. The electrostatic voltages applied to the cell and filament current were optimized to obtain maximum transmission in non-ECD mode (normal operation) and maximum ECD fragment ion intensity in ECD mode. Different settings were required for ion mobility mode where the gas flow of N2 from the IMS cell affected the optimum settings. The details of electrostatic potentials and filament current settings, both for ECD and the transmission of intact ions, are provided in Supporting Information S-1.

In order to physically fit the ECD cell, we replaced the standard transfer cell with a modified shorter version that was previously used to accommodate a surface-induced dissociation (SID) cell involved in a prior research project.32 The ECD cell was then secured onto the exit of the IMS cell. The higher-pressure region of the transfer cell was unaffected by the modification and could be used for additional collision induced dissociation if required, for example, to provide supplemental activation. Furthermore, this cell was still utilized to provide optimum collisional cooling and coupling to the orthogonal acceleration time-of-flight (TOF), thus maintaining transmission and TOF resolution.

Data analysis was performed using the recently published Masstodon software, which requires that multiple isotope peaks are observed with good mass accuracy for fragment identification.33 Peak assignments were then manually verified using MassLynx 4.1. Images showing the crystal structures were generated using YASARA View.34 Coordinate files were taken from the Protein Data Bank with accession codes 2DN2 (hemoglobin) and 4W6Z (ADH).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Complete Removal of Nonvolatile Salts in Native Electrospray-MS Using Online SEC.

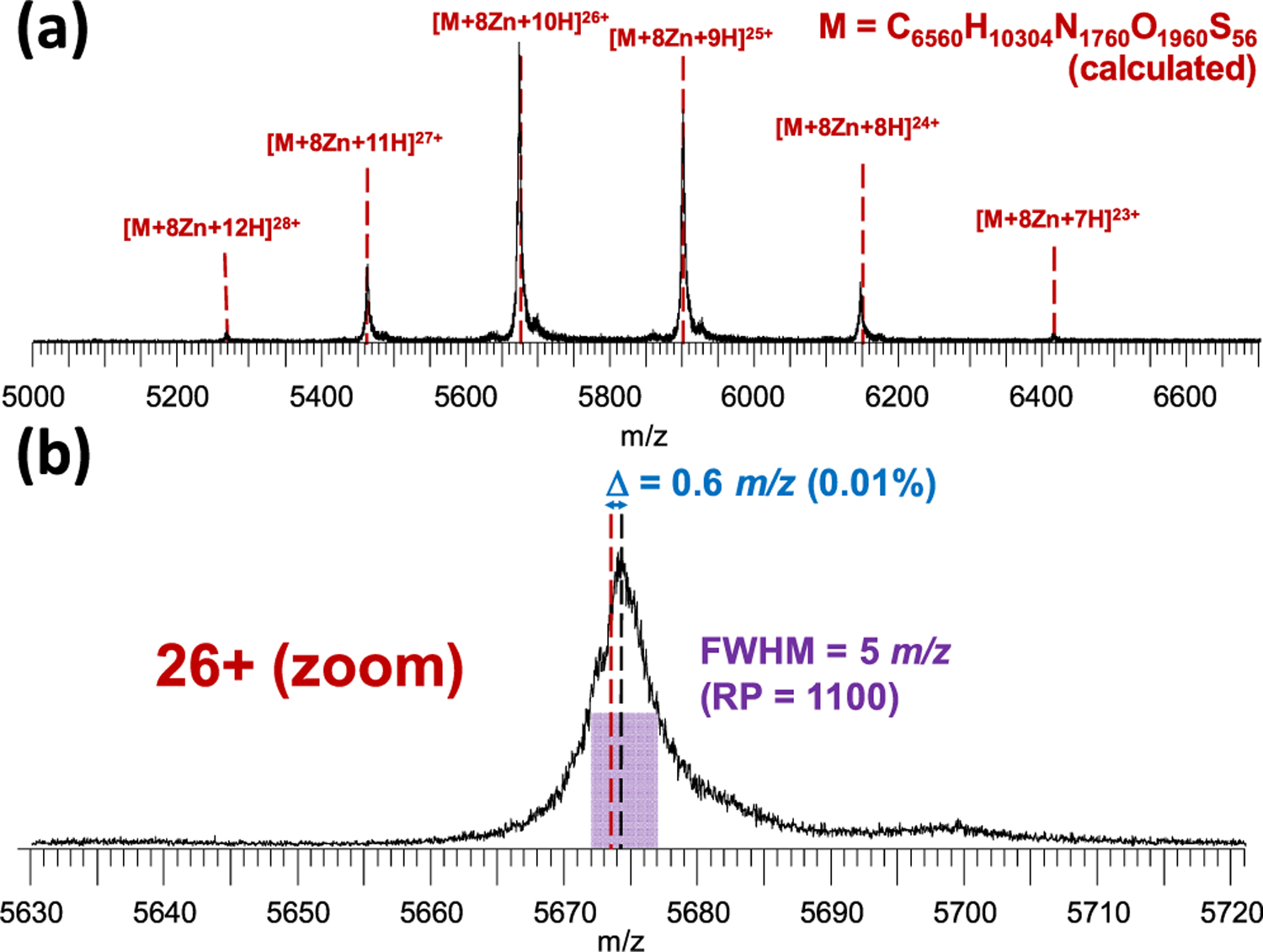

It is well-known to practitioners of native MS that peak broadening occurs due to adduct formation with residual solvent and buffer molecules but especially nonvolatile ions such as Na+. This significantly reduces the effective resolving power of the instrument, complicating the determination of sequence and stoichiometry. Usually, this issue is addressed by, often multiple rounds of, offline desalting. Here, we used online SEC as an alternative desalting method for native protein complexes. Figure 2 shows the native mass spectrum of ADH following online SEC, without isolation or fragmentation. This spectrum shows the average of 15 (1 spectrum/s) scans with no smoothing applied to the spectrum. A narrow distribution of multiply charged ions from 23+ to 28+ was observed, as is normal in native ESI of this tetrameric complex.19,35 Remarkably for native MS, the observed peak width (fwhm) for the 26+ charge state of the tetramer was only 5 m/z (Figure 2b). Previously, using size-exclusion spin columns for offline desalting of the same protein, we have observed peak widths of 20–30 m/z on Synapt G2 and G2-S instruments,18,19,36 and a spectrum using offline desalting on the current G2-Si instrument can be found in Supporting Information S-2. In a recent report,35 Kelleher and colleagues observed similarly narrow peaks to what is reported here for native ADH on an Orbitrap mass spectrometer after offline desalting with centrifugal filters; however, this required 10 to 15 consecutive desalting steps, representing a significant investment of time and labor and increasing the risk of sample contamination or loss during handling. In agreement with this recent report, we found that the mass of ADH purchased from this supplier, after taking into account the removal of initiator methionine, N-terminal acetylation, and the binding of two Zn2+ ions per subunit, did not match that of the canonical sequence found in UniProt (accession number P00330) but instead was more consistent with an isoleucine-to-valine point mutation, most likely in position 151 or 337.37 When this substitution was taken into account, the measured average mass of the complex (deconvoluted using the MaxEnt 1 algorithm in the MassLynx software) provided an accuracy of 0.01%. The fact that the observation of this variant is rarely reported in one of the most often used standard proteins in native and top-down MS highlights the importance of thorough desalting in this context, as sequence variants and PTMs can otherwise easily be obscured by excessively broad peaks. As demonstrated here, and in earlier work by Heck and colleagues,38 online SEC provided a fast, high-throughput solution for this issue and is likely to play an important role as native top-down proteomics approaches become more mainstream.

Figure 2.

(a) Charge state series for the native ADH tetramer after online SEC. Dashed lines indicate the calculated maxima (i.e., most abundant isotope peaks) for charge states from 23+ to 28+. (b) Zoom on the 26+ charge state, showing the extreme (for native MS) resolving power and mass accuracy achieved with this method. “Δ” denotes the difference between the observed (blue) and calculated (red) maximum. Note that the Zn2+ binding adds 61.91 Da per metal cation (495.32 Da for all eight or approximately 0.34% of the mass of the complex), corresponding to 2.38 m/z at this charge state (19.05 m/z in total), and is thus easily observable with this method. No smoothing of the spectrum was performed.

ECD Fragmentation of Denatured Peptides and Proteins without Reductions in Duty Cycle.

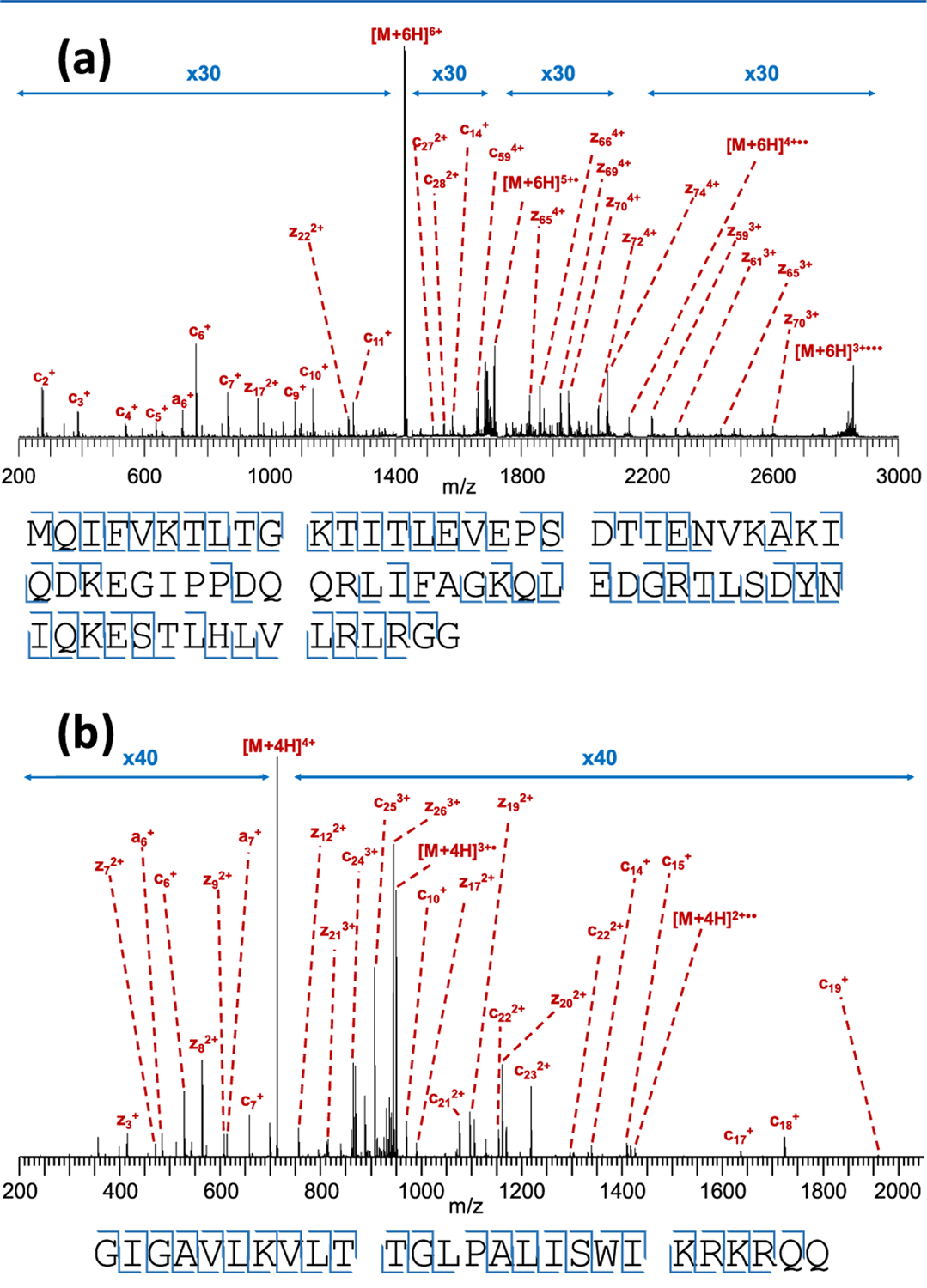

Native top-down ECD of protein complexes is still a challenging experiment, even with well-characterized instruments. It is therefore good practice, before attempting this type of experiment using a new instrument, to test its performance with well-known standards. In this case, we tuned and benchmarked the modified Synapt G2-Si platform using denatured substance P, mellitin, and ubiquitin. The 2+ charge state of the 11-residue peptide substance P (with amidated C-terminus) was used for the initial tuning of the instrument following implementation of the EMS cell (Supporting Information S-3). This led to the observation of eight N-terminal c-type fragments (c2+, c4+, c5+, c6+, c7+, c8+, c9+, and c10+) and one z-type fragment (z9+), in agreement with previous reports.39 Fragments resulting from the cleavage of all inter-residue bonds were observed, except the two bonds located N-terminal to the proline residues, where dissociation after cleavage of the N–Cα bond is prevented by the “fragments” remaining bound via the pyrrolidine side chain. Smaller z-type fragments were not observed as the two positive charges in 2+ substance P are located near the N-terminus.39 Once satisfactory signal-to-noise ratios were achieved for fragment ions, we moved on to larger peptides and intact proteins. The 26-residue peptide mellitin and the 76-residue small protein ubiquitin were analyzed independently using direct infusion ESI under denaturing conditions (50% acetonitrile; 0.2% formic acid). Results for these experiments are shown in Figure 3. For ubiquitin, the 6+ charge state was isolated in the quadrupole mass filter of the instrument and subjected to ECD, resulting in the cleavage of 62 out of 75 inter-residue bonds (83%), with three of the remaining 13 being N-terminal to proline residues. For mellitin, all 24 bonds not N-terminal to proline were cleaved; i.e., the maximum cleavage coverage theoretically possible with ECD was attained in this experiment. Importantly, this fragmentation occurred in a “fly through” mode, meaning there was no reduction in duty cycle. As ECD does not rely on the interaction of the precursor cation with a reagent anion, no polarity switching of the source or optimization of the analyte/reagent ratio was required. This is important, as the user expertise required to tune this ratio has been considered a major factor preventing the more widespread adoption of electron-based fragmentation methods.24

Figure 3.

(a) Top-down ECD spectrum of 6+ ubiquitin using the electromagnetostatic cell on the Synapt G2-Si, resulting in the cleavage of 62 out of 75 inter-residue bonds (83% cleavage coverage). (b) ECD of 4+ mellitin, resulting in the cleavage of 24 out of 25 bonds (96%). Cleavage diagrams are displayed below the spectra. Note the 30- and 40-fold magnification used; while fragments are very low in intensity compared to the (charge-reduced) precursor, signal-to-noise for these ions is excellent. Charge-reduced species in both panels are annotated as n-radicals for simplicity, although they are actually a complex mixture of ions produced by nondissociative electron capture with and without subsequent loss of H•, as explored in-depth in previous work.17,40

Comparison of ECD and ETD of Native Tetrameric Alcohol Dehydrogenase under Otherwise Identical Instrument Conditions.

As the Synapt G2-Si has built-in ETD capabilities, we wished to perform a side-by-side comparison of both methods. An alternative implementation of ECD has been developed for Synapt instruments before; however, this only allowed ECD to occur in the source region of the instrument, complicating the comparison with ETD, which is implemented in the trap region.41 As the electromagnetostatic cell in the current work was mounted within the Triwave region of the instrument, the comparison of both fragmentation methods was more straightforward.

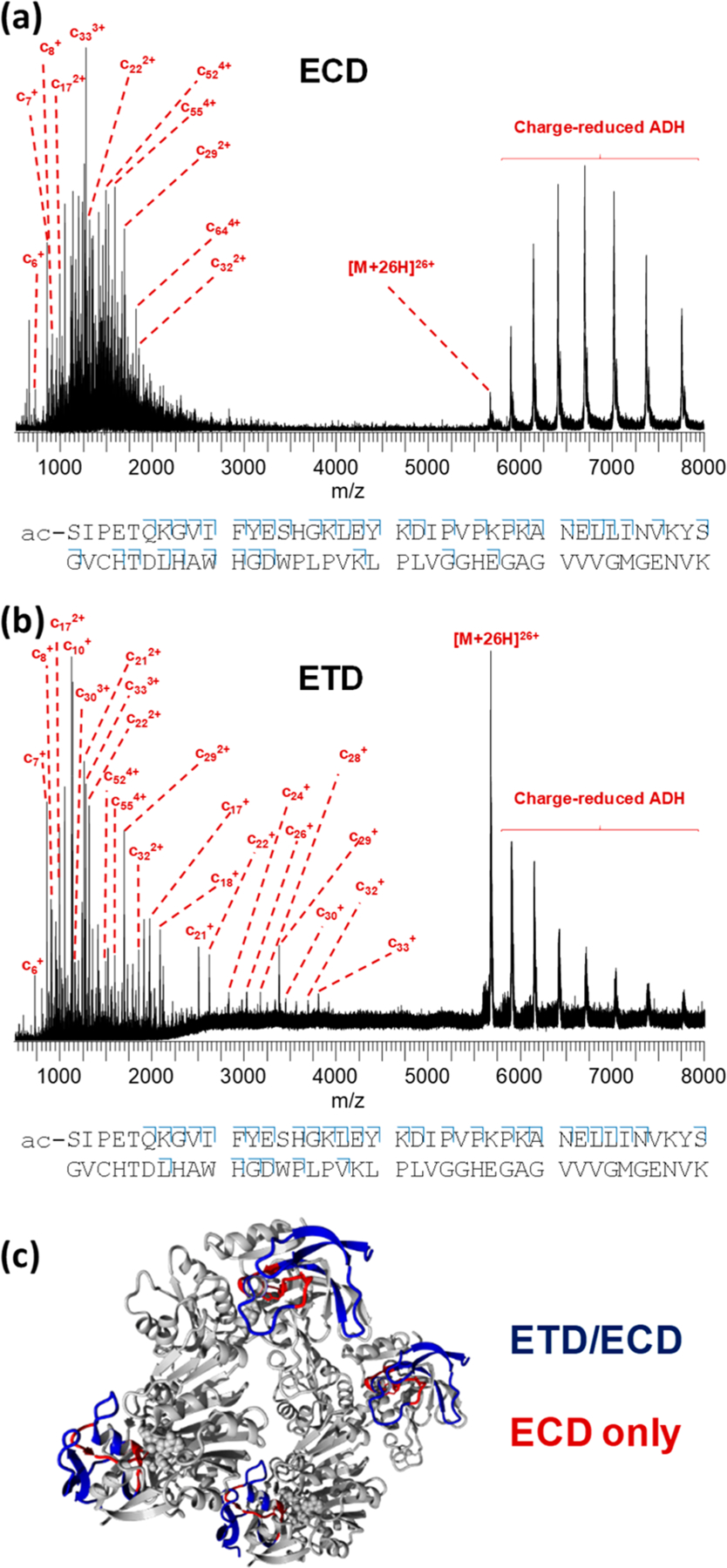

In Figure 4, native top-down ECD (a) and ETD (b) of the 26+ ADH tetramer are shown. The observed fragmentation pattern in both cases was rather similar to what we previously observed using ETD on this instrument18,19,36 and also to the results reported by Gross and colleagues20,21 who used ECD on an FTICR instrument. As in these previous studies, only (N-terminal) c-type ions were observed, presumably as the N-terminus of the monomers in this complex is more exposed and therefore better able to release fragments. In both ECD and ETD of 26+ ADH, fragments were observed coming from the first 60–70 residues of the protein, also matching the earlier work. Cleavage coverage for both fragmentation methods was very good in the first 40 residues and then more sparse up to V(58), and three additional fragments (c59, c64, and c67) from further along the sequence were observed exclusively in ECD. The main difference between both techniques was observed in the sequence region [S(40)–H(51)], for which ECD generated more fragments than ETD. We have previously reported that this region has relatively low solvent accessibility, calculated on the basis of the crystal structure.19 We have previously raised the possibility that low-energy electrons transferred from a reagent anion might be less able to penetrate into the buried “core” of a folded protein than electrons coming from a cathode and that the ETD fragmentation pattern might therefore better reflect the exposed protein surface than ECD.16 This speculation was based on mechanistic differences between the two methods. More experiments are, however, required before making a definitive statement would be possible. Sequence regions from which ETD and ECD fragments originate are shown on the tetramer crystal structure in Figure 4c.

Figure 4.

(a) Native top-down ECD spectrum of 26+ ADH tetramer using the electromagnetostatic cell on the Synapt G2-Si, resulting in the cleavage of 40 out of 346 inter-residue bonds (11.6% cleavage coverage). (b) Native top-down ETD of the same precursor on the same instrument, resulting in the cleavage of 34 bonds (9.8%). Cleavage diagrams are displayed below the spectra (only the first 80 N-terminal residues are shown for clarity). Results from both ETD and ECD are highlighted on the ADH crystal structure in (c) with sequence regions probed by both methods shown in blue and regions probed only with ECD, in red.

The ETD spectrum in Figure 4 shows a series of singly charged fragment ions between 2000–4000 m/z, in contrast to ECD, where fragments occurred at higher charge states. This could be an indication that ETD under standard G2-Si conditions led to more (nondissociative) reaction steps. This is seemingly contradicted by the presence of a more pronounced series of charge-reduced tetramer peaks in the ECD spectrum; however, we have previously noted that efficient transmission of extensively charge-reduced intact protein complex ions generated in the trap cell requires increased trap DC bias and/or transfer collision energy voltages. In both spectra shown in Figure 4, these voltages were held at 2 and 0 V, respectively, possibly explaining why the signal intensity for charge-reduced tetramer ions in the ETD spectrum was rather low. Presumably, transmission of charge-reduced tetramer generated immediately before entry into the transfer cell (i.e., under ECD conditions) with standard tuning parameters was more efficient than in spectra where the charge-reduced ion also had to traverse the helium and ion mobility cells of the instrument (i.e., ETD conditions).

Probing Initial Monomer Unfolding in Tetrameric Human Hemoglobin with Activated-Ion Mobility-ECD.

Since shortly after the invention of ECD, it has been known that the fragmentation pattern observed using this dissociation method is dependent on the higher-order structure of peptides and proteins. Pioneering work was performed with ECD-capable FTICR instruments in the first decade of the 21st century, allowing the gas-phase structure of some peptides and small proteins to be investigated.13,14,42–44 In particular, gas-phase unfolding and refolding were studied in some of these early reports, and this was later extended to monitoring initial monomer unfolding events in native top-down ECD of protein complexes.20,45 In a particularly important study, Gross and colleagues subjected tetrameric human hemoglobin to ECD on an FTICR instrument with different degrees of in-source (nozzle-skimmer) ion activation (10–125 V potential offset) prior to ECD.46 In parallel, ion mobility measurements of the same sample were performed using a Synapt G2 Q-IM-TOF platform and applying a similar level (18–88 V) of ion activation at the sampling cone. Under the assumption that the complex adopted similar conformations in the mobility cell of the Synapt instrument and in the ICR cell, this experiment allowed correlation of a low-resolution parameter that reflects the whole protein assembly (i.e., collision cross-section) with residue-specific ECD data from the N-terminal region. Possible differences in ion structure between both instruments due to different pressure regimes, source designs, temperatures, and residence time, however, were not explicitly accounted for in this report.

Around the same time as the study by Gross and colleagues, a report was published in which ETD and IM of the hemoglobin tetramer were both performed using a Synapt G2 instrument, allowing for a more direct comparison between both types of data.18 Stepwise ion activation was also performed by varying the sampling cone voltage in this case. Performing ETD in ion mobility mode, however, resulted in a significant reduction in signal intensity for ETD fragments as well as fragment release prior to mobility separation, whereas it would be more useful for structural biology to perform electron-based fragmentation only after IM separation of different protein conformations. Nondissociative electron transfer of ubiquitin followed by mobility separation and post-IM fragment release via supplemental collisional activation has been reported; however, this requires extremely careful instrument tuning and is very challenging for larger or more conformationally heterogeneous proteins or complexes.47 In 2016, Costello and colleagues reported electronic excitation dissociation of glycans separated by trapped ion mobility on a TIMS-Q-FTICR platform.48 While this is a powerful approach, it should be noted that ions are usually accumulated for a significant amount of time (up to seconds) in the collision cell of the FTICR instrument in this type of study, potentially allowing a degree of ion cooling and/or refolding when attempting to probe protein higher-order structure with ECD.

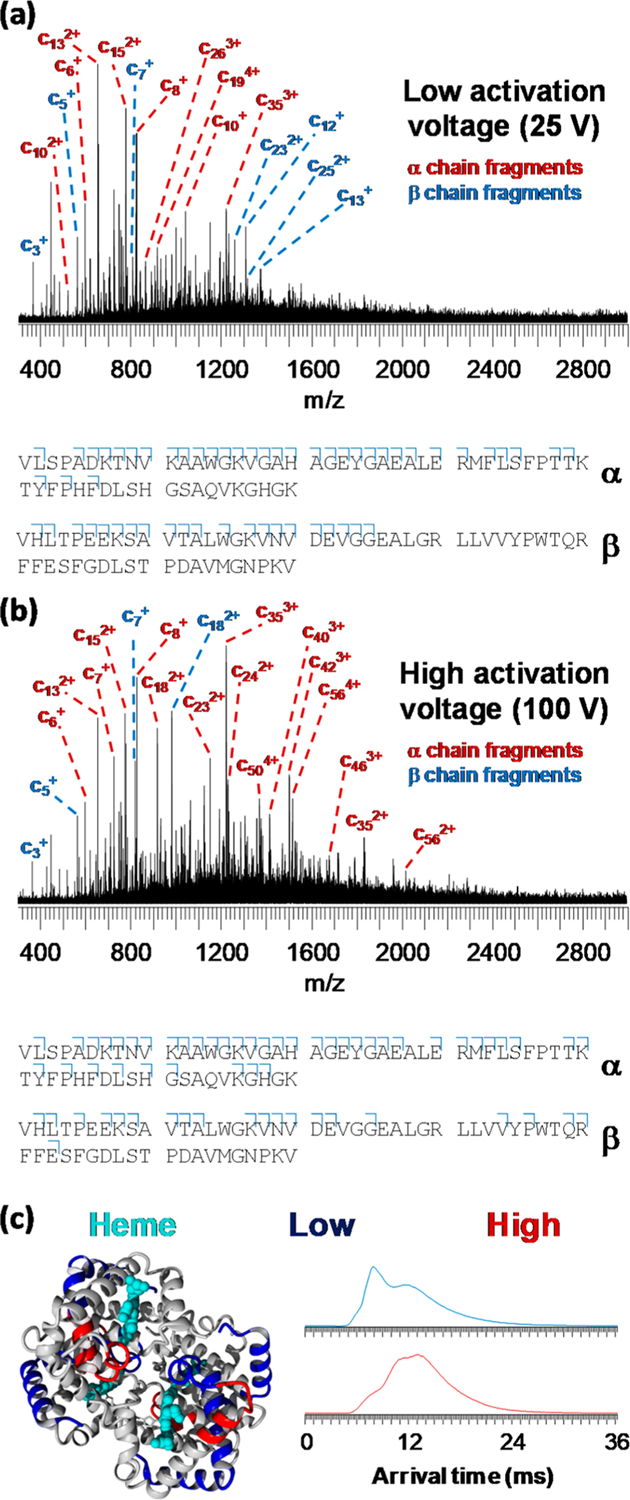

In contrast to these previous studies, the modified Synapt instrument used in the current work allows ECD fragmentation to occur immediately after ion mobility separation with no increase in residence time (“fly through” mode). While conceptually similar experiments have been performed using ultraviolet photodissociation,49–53 the workflow presented here allows the most direct correlation between ion mobility and the electron-based fragmentation pattern to date. As multiple literature reports exist describing ETD or ECD of the partially unfolded hemoglobin tetramer,18,45,46 we decided to use this protein complex as our model system. Following the methodology used in these previous reports, we performed IM-ECD by applying a low (25 V) and high (100 V) potential at the sampling cone of the instrument. Using SEC, charge states 16+ (4029 m/z), 17+ (3792 m/z), and 18+ (3581 m/z) were observed at a high signal intensity with a peak width (fwhm) of around 1.2 m/z (resolving power ca. 3000) and matching the theoretical average mass of 64 453.01 Da for holo-hemoglobin to within 0.0015% (Supporting Information S-4). We note that, while the effective resolving power was approximately an order of magnitude below the instrument specifications, this was predominantly due to the inherent width of the isotope distribution (theoretically ca. 1.0 m/z fwhm at this charge state) as separating individual isotope peaks of a 64 kDa complex is beyond the capabilities of this instrument operating in this acquisition mode. To improve the signal intensity for fragments, the entire native charge state distribution was subjected to ECD, similar to the approach used previously by Gross and colleagues.20,21 Results for this experiment are summarized in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Native top-down IM-ECD spectra of human hemoglobin applying a pre-IM activation voltage at the sampling cone of (a) 25 V and (b) 100 V. Cleavage diagrams are displayed below the spectra with only the first 60 N-terminal residues shown for clarity. Cleavage coverage was 25.0% (α-subunit, 25 V cone), 14.5% (β, 25 V), 29.3% (α, 100 V), and 14.5% (β, 100 V). In (c), results are shown on the hemoglobin tetramer crystal structure (left-hand side) with sequence regions probed with low activation energy in blue and additional regions probed using high energy in red. On the right-hand side of (c), arrival time distributions for the tetramer (mobility measurement immediately prior to ECD) are shown with a low (blue) and high (red) cone voltage.

Using either a low (Figure 5a) or high (Figure 5b) cone voltage, fragmentation was more extensive in the α- than in the β-subunit of hemoglobin, in agreement with previous reports.18,36,45,46 With a low cone voltage, cleavage coverage in the first 30 residues of the α-subunit was near-complete, with additional fragments observed up to c46. For the β-subunit, excellent coverage was observed for the first 25 residues, with no fragments larger than c25 being observed. At a high sampling cone voltage, additional fragments were observed up to c58 for the α-subunit and up to c43 for the β-subunit, demonstrating as expected that the pre-ECD collisional activation allows fragmentation from further along the protein sequence. In Figure 5c, these results are shown with a color code on the crystal structure of the tetramer. This reveals that, for the α-subunit, the additional fragmentation (shown in red) was caused by the unfolding and becoming available for fragmentation of the sequence region between the [P(37) – Y(42)] and [A(53) – A(71)] α-helices, the latter of which remained largely intact and “protected” from ECD under these conditions. This is consistent with our hypothesis, stated in the discussion of the ADH results, that electrons in ECD are better able to penetrate into the core of a folded protein than those in ETD, as the protection observed for helix [A(53) – A(71)] is likely due to fragments remaining bound by noncovalent hydrogen bonds rather than being related to surface accessibility. Meanwhile, for the β-subunit, the additional fragments originated from the [V(20) – V(34)] and [P(36) – F(45)] α-helices, the first of which was already partially probed at a low cone voltage, possibly representing limited unfolding during transfer of the complex into the gas phase. Simultaneously acquired IM results using a low and high sampling cone are shown on the right of Figure 5c, confirming that a shift to higher arrival times (i.e., more extended structures) occurred under more activating conditions.

CONCLUSIONS

In the past decade, mass spectrometry has provided immense benefits for protein analysis. Native ionization coupled with advanced dissociation allows the correlation of the fragmentation pattern to higher-order protein structure. Meanwhile, ion mobility is becoming more mainstream, allowing the probing of structural unfolding or global conformational changes but not the identification of the exact region of unfolding. Here, collision-induced unfolding was followed by ion mobility separation and subsequent electron capture dissociation on a quadrupole/ion mobility/time-of-flight platform, allowing the precise location of unfolding to be inferred from the observed fragmentation patterns. This method has thus allowed protein–protein complexes to be interrogated for both higher-order structure and sequence-specific fragmentation information within the same experimental analysis. The use of online desalting with size-exclusion chromatography and native electrospray ionization allowed highly accurate determination of the precursor mass, which is the principal benefit of top-down mass spectrometry. We expect that the approach presented in this work will open up new vistas for (native) top-down MS and integrated structural proteomics.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by EPSRC grant EP/N033191/1 and by SBIR awards from the US National Institutes of Health to V.G.V. (R43GM122131–01 and R44GM122131–02). We are grateful to the reviewers for their insightful comments.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.analchem.9b04763.

Optimized potentials for the EMS cell; comparison of online SEC and offline desalting of the ADH tetramer; ECD of 2+ substance P; native SEC-ESI-MS of human hemoglobin tetramer without fragmentation (PDF)

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.9b04763

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Jonathan P. Williams, Waters Corporation, Wilmslow SK9 4AX, United Kingdom.

Lindsay J. Morrison, Waters Corporation, Wilmslow SK9 4AX, United Kingdom

Jeffery M. Brown, Waters Corporation, Wilmslow SK9 4AX, United Kingdom.

Joseph S. Beckman, e-MSion Inc., Corvallis, Oregon 97330, United States; Linus Pauling Institute and the Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon 97331, United States

Valery G. Voinov, e-MSion Inc., Corvallis, Oregon 97330, United States; Linus Pauling Institute and the Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon 97331, United States

Frederik Lermyte, School of Engineering and Department of Chemistry, University of Warwick, Coventry CV4 7AL, United Kingdom.

REFERENCES

- (1).Kelleher NL; Taylor SV; Grannis D; Kinsland C; Chiu HJ; Begley TP; McLafferty FW Protein Sci 1998, 7, 1796–1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Smith LM; Thomas PM; Shortreed MR; Schaffer LV; Fellers RT; LeDuc RD; Tucholski T; Ge Y; Agar JN; Anderson LC; Chamot-Rooke J; Gault J; Loo JA; Pasa-Tolic L; Robinson CV; Schluter H; Tsybin YO; Vilaseca M; Vizcaino JA; Danis PO Nat. Methods 2019, 16, 939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Donnelly DP; Rawlins CM; DeHart CJ; Fornelli L; Schachner LF; Lin Z; Lippens JL; Aluri KC; Sarin R; Chen B; Lantz C; Jung W; Johnson KR; Koller A; Wolff JJ; Campuzano IDG; Auclair JR; Ivanov AR; Whitelegge JP; Pasa-Tolic L; et al. Nat. Methods 2019, 16, 587–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Schadt EE; Turner S; Kasarskis A Hum. Mol. Genet 2010, 19, R227–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Sheynkman GM; Shortreed MR; Cesnik AJ; Smith LM Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem 2016, 9, 521–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).LeDuc RD; Schwammle V; Shortreed MR; Cesnik AJ; Solntsev SK; Shaw JB; Martin MJ; Vizcaino JA; Alpi E; Danis P; Kelleher NL; Smith LM; Ge Y; Agar JN; Chamot-Rooke J; Loo JA; Pasa-Tolic L; Tsybin YO J. Proteome Res 2018, 17, 1321–1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Dang X; Scotcher J; Wu S; Chu RK; Tolic N; Ntai I; Thomas PM; Fellers RT; Early BP; Zheng Y; Durbin KR; Leduc RD; Wolff JJ; Thompson CJ; Pan J; Han J; Shaw JB; Salisbury JP; Easterling M; Borchers CH; et al. Proteomics 2014, 14, 1130–1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Smith LM; Kelleher NL Nat. Methods 2013, 10, 186–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Smith LM; Kelleher NL Science 2018, 359, 1106–1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Konijnenberg A; Butterer A; Sobott F Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Proteins Proteomics 2013, 1834, 1239–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Dixit SM; Polasky DA; Ruotolo BT Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2018, 42, 93–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Gabelica V; Shvartsburg AA; Afonso C; Barran P; Benesch JLP; Bleiholder C; Bowers MT; Bilbao A; Bush MF; Campbell JL; Campuzano IDG; Causon T; Clowers BH; Creaser CS; De Pauw E; Far J; Fernandez-Lima F; Fjeldsted JC; Giles K; Groessl M; et al. Mass Spectrom. Rev 2019, 38, 291–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Breuker K; Oh H; Horn DM; Cerda BA; McLafferty FW J. Am. Chem. Soc 2002, 124, 6407–6420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Oh H; Breuker K; Sze SK; Ge Y; Carpenter BK; McLafferty FW Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2002, 99, 15863–15868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Zhang Y; Cui W; Wecksler AT; Zhang H; Molina P; Deperalta G; Gross ML J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2016, 27, 1139–1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Lermyte F; Valkenborg D; Loo JA; Sobott F Mass Spectrom. Rev 2018, 37, 750–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Lermyte F; Lacki MK; Valkenborg D; Gambin A; Sobott F J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2017, 28, 69–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Lermyte F; Sobott F Proteomics 2015, 15, 2813–2822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Lermyte F; Konijnenberg A; Williams JP; Brown JM; Valkenborg D; Sobott F J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2014, 25, 343–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Zhang H; Cui W; Wen J; Blankenship RE; Gross ML Anal. Chem 2011, 83, 5598–5606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Zhang H; Cui W; Wen J; Blankenship RE; Gross ML J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2010, 21, 1966–1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Brodbelt JS Anal. Chem 2016, 88, 30–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Lermyte F; Tsybin YO; O’Connor PB; Loo JA J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2019, 30, 1149–1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Rose CM; Rush MJ; Riley NM; Merrill AE; Kwiecien NW; Holden DD; Mullen C; Westphall MS; Coon JJ J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2015, 26, 1848–1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Voinov VG; Hoffman PD; Bennett SE; Beckman JS; Barofsky DF J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2015, 26, 2096–2104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Voinov VG; Bennett SE; Barofsky DF J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2015, 26, 752–761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Voinov VG; Deinzer ML; Beckman JS; Barofsky DF J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2011, 22, 607–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Voinov VG; Beckman JS; Deinzer ML; Barofsky DF Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom 2009, 23, 3028–3030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Voinov VG; Deinzer ML; Barofsky DF Anal. Chem 2009, 81, 1238–1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Voinov VG; Deinzer ML; Barofsky DF Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom 2008, 22, 3087–3088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Shaw JB; Malhan N; Vasil’ev YV; Lopez NI; Makarov A; Beckman JS; Voinov VG Anal. Chem 2018, 90, 10819–10827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Harvey SR; Yan J; Brown JM; Hoyes E; Wysocki VH Anal. Chem 2016, 88, 1218–1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Lacki MK; Lermyte F; Miasojedow B; Startek MP; Sobott F; Valkenborg D; Gambin A Anal. Chem 2019, 91, 1801–1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Krieger E; Vriend G Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2981–2982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Schachner LF; Ives AN; McGee JP; Melani RD; Kafader JO; Compton PD; Patrie SM; Kelleher NL J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2019, 30, 1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Lermyte F; Williams JP; Brown JM; Martin EM; Sobott F J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2015, 26, 1068–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Jornvall H Eur. J. Biochem 1977, 72, 425–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Kukrer B; Filipe V; van Duijn E; Kasper PT; Vreeken RJ; Heck AJ; Jiskoot W Pharm. Res 2010, 27, 2197–2204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Mihalca R; Kleinnijenhuis AJ; McDonnell LA; Heck AJ; Heeren RM J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2004, 15, 1869–1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Lermyte F; Lacki MK; Valkenborg D; Baggerman G; Gambin A; Sobott F Int. J. Mass Spectrom 2015, 390, 146–154. [Google Scholar]

- (41).Robb DB; Brown JM; Morris M; Blades MW Anal. Chem 2014, 86, 4439–4446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Breuker K; Oh H; Lin C; Carpenter BK; McLafferty FW Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2004, 101, 14011–14016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Horn DM; Breuker K; Frank AJ; McLafferty FW J. Am. Chem. Soc 2001, 123, 9792–9799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Hamidane HB; He H; Tsybin OY; Emmett MR; Hendrickson CL; Marshall AG; Tsybin YO J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2009, 20, 1182–1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Zhang J; Reza Malmirchegini G; Clubb RT; Loo JA Eur. J. Mass Spectrom 2015, 21, 221–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Cui W; Zhang H; Blankenship RE; Gross ML Protein Sci 2015, 24, 1325–1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Lermyte F; Verschueren T; Brown JM; Williams JP; Valkenborg D; Sobott F Methods 2015, 89, 22–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Pu Y; Ridgeway ME; Glaskin RS; Park MA; Costello CE; Lin C Anal. Chem 2016, 88, 3440–3443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Warnke S; von Helden G; Pagel K Proteomics 2015, 15, 2804–2812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Warnke S; Baldauf C; Bowers MT; Pagel K; von Helden G J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 10308–10314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Theisen A; Black R; Corinti D; Brown JM; Bellina B; Barran PE J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2019, 30, 24–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Theisen A; Yan B; Brown JM; Morris M; Bellina B; Barran PE Anal. Chem 2016, 88, 9964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Riggs DL; Hofmann J; Hahm HS; Seeberger PH; Pagel K; Julian RR Anal. Chem 2018, 90, 11581–11588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.