Abstract

Background

Acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD) carry significant morbidity and mortality. AECOPD treatment remains limited. High molecular weight hyaluronan (HMW-HA) is a glycosaminoglycan sugar, which is a physiological constituent of the lung extracellular matrix and has notable anti-inflammatory and hydrating properties.

Research question

We hypothesized that inhaled HMW-HA will improve outcomes in AECOPD.

Methods

We conducted a single center, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study to investigate the effect of inhaled HMW-HA in patients with severe AECOPD necessitating non-invasive positive-pressure ventilation (NIPPV). Primary endpoint was time until liberation from NIPPV.

Results

Out of 44 screened patients, 41 were included in the study (21 for placebo and 20 for HMW-HA). Patients treated with HMW-HA had significantly shorter duration of NIPPV. HMW-HA treated patients also had lower measured peak airway pressures on the ventilator and lower systemic inflammation markers after liberation from NIPPV. In vitro testing showed that HMW-HA significantly improved mucociliary transport in air–liquid interface cultures of primary bronchial cells from COPD patients and healthy primary cells exposed to cigarette smoke extract.

Interpretation

Inhaled HMW-HA shortens the duration of respiratory failure and need for non-invasive ventilation in patients with AECOPD. Beneficial effects of HMW-HA on mucociliary clearance and inflammation may account for some of the effects (NCT02674880, www.clinicaltrials.gov).

Background

The morbidity and mortality associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is increasing worldwide. The World Health Organization predicts that COPD will become the third leading cause of death worldwide by 2030 [1]. COPD remains the third leading cause of death in the United States [2] and by 2020 it was projected to lead to a staggering $49 billion cost [3]. Acute exacerbations of COPD (AECOPD) may occur in > 90% of COPD patients [4] and often necessitate hospitalization [5], which is the most important cost driver in COPD [6–8]. Among hospitalized patients, morbidity and health care costs are associated with severe AECOPD, which leads to need for high-level and prolonged care [9]. Treatment for AECOPD remains limited, including bronchodilators, non-specific anti-inflammatory corticosteroids, and antibiotics, and novel, effective anti-inflammatory agents are needed.

High molecular weight hyaluronan (HMW-HA) is a naturally occurring sugar, that is abundant in the extracellular matrix, including in the lung. HMW-HA has several properties that make it an attractive candidate as a therapeutic in AECOPD: HMW-HA is a very hydrophilic molecule [10], and has been used as an airway hydrating agent for several years [11], which may improve mucociliary transport in COPD. HMW-HA ameliorates airway hyperresponsiveness in murine models [12–14] and humans [15], has potent anti-inflammatory properties and ameliorates lung epithelial injury [16–18]. We therefore hypothesized that inhaled HMW-HA may be beneficial in AECOPD, especially in patients with impeding respiratory failure. This randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study included patients with severe AECOPD, necessitating bi-level non-invasive positive pressure ventilation (NIPPV). We reasoned that inhaled HMWHA may assist in improving lung function and therefore shorten the need for NIPPV in these patients.

Methods

Study design

This was a parallel-arm, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blinded, single-center pilot study of patients admitted to the Intermediate Care Section, Geriatric Unit, Campus Bio-Medico, University of Rome, between March 2016 and July 2019. Included were adult patients with known history of physician-diagnosed COPD and acute exacerbation requiring NIPPV, as evidenced by respiratory distress (new-onset moderate to severe dyspnea and use of accessory breathing muscles) and hypercapnic respiratory failure (partial pressure of CO2 > 45 mm Hg in arterial blood gas analysis, new or increased compared to baseline, when a baseline value was available). Exclusion criteria were respiratory arrest or need for immediate intubation, overt pneumonia on chest X-ray, significant non-COPD contributing factors to respiratory failure (e.g. congestive heart failure), contraindications to NIPPV (upper airway obstruction, facial trauma) or inability to consent or cooperate with NIPPV. After informed consent, patients were randomized 1:1 to receive study treatment, either HMW-HA or identical-looking placebo. The HMW-HA preparation was Yabro® (5 ml of saline containing 0.3% hyaluronic acid sodium salt, Institute Biochimique SA, Lugano, Switzerland). Yabro® and placebo were generous donations of the manufacturer, who had the key to the randomization schema. Patients were treated with NIPPV using a Hamilton C1 ventilator and medical therapy according to current guidelines (inhaled β2 agonists, inhaled anticholinergic agents, inhaled and systemic corticosteroids, antibiotics) [19]. NIPPV was temporarily interrupted for the duration of nebulization. Patients received Yabro® or placebo via a non-ultrasonic jet nebulizer (Vincal®, which guarantees appropriate nebulizer output as instructed in the Yabro® package leaflet) twice daily, until they were liberated from NIPPV or until NIPPV failure, defined as need for orotracheal intubation due to difficulty in managing airway secretions, worsening arterial blood gas parameters, or cardiorespiratory arrest. The decision to liberate from NIPPV was reached as follows: for patients not on home/chronic NIPPV, NIPPV was discontinued when an improvement of pH and/or a pCO2 < 55 was reached. For patients using home/chronic NIPPV (4/21 in the placebo group and 3/20 in the Yabro® group), NIPPV was reset to home settings when an improvement of pH and/or pCO2 was reached, and this was considered to be equivalent to “liberation from NIPPV” status. The study was co-sponsored by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institutes of Health, USA, and the Campus Bio-Medico, University of Rome, Italy. The manufacturer had no role in the conduct or analysis of this study. Serum was collected on admission and after liberation from NIPPV and stored at − 80 °C until analyzed.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was duration until liberation from NIPPV or NIPPV failure. Secondary outcomes were: (a) respiratory physiology parameters (ventilator-recorded peak pressures as an indicator of airway resistance; partial arterial O2 and pCO2 pressures on arterial blood gas analysis); and (b) markers of systemic inflammation associated with AECOPD (C-reactive protein; Interleukin 6 [IL-6]; Interleukin 8 [IL-8]; C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 10 [CXCL10]) [20–24]. Adverse events were recorded regardless of whether they were deemed to be related to treatments.

Analysis

Cumulative hours on NIPPV were plotted on GraphPad Prism, version 8, and analyzed using the log-rank Mantel-Cox test. NIPPV days and hospital length-of-stay values were analyzed for normality using GraphPad Prism software and comparisons were performed either using the Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney test according to normality. Categorical variables were analyzed using Fisher’s exact test. For inflammation markers, values for the 4 analytes (CRP, CXCL10, IL-6, and IL-8) were ln-transformed to more closely approximate normality. Data were cast in “long” format with 8 records per subject: 4 reactants × 2 times (pre- and post-treatment) and analyzed using SAS 9.4 Proc Mixed, regressing the ln(reactant values) on treatment group (HMW-HA vs. placebo), timing (pre vs. post), and reactant type, with timing and reactant type as repeated measures, and subject ID entered to capture the subject effect. In initial models we included the 3-way interaction of group × timing × reactant, plus all possible 2-way interactions and main effects. We tested this 3-way model with three different Kronecker product covariance structures [25], which allow for the modeling of two repeated measures by combining two covariance matrices. We chose a combination of two unstructured covariance matrices as providing the best fit, based on the Akaike Information Criterion. We ran additional models, removing the 3-way and non-significant 2-way interactions and ran separate mixed models for the 2 groups, to obtain least-square means for pre- and post- times, to assess significant change for any inflammation markers.

Air–liquid interface culture

To gain novel mechanistic insights into the effect of HMW-HA effects in COPD, we analyzed its effect on mucociliary clearance, since airway clearance is important for both chronic and acute COPD management [26]. Primary human bronchial epithelial (HBE) cells were isolated from lung explants from COPD patients and no lung disease control donors, expanded in submerged culture for one or two passages in Bronchial epithelial growth medium (BEGM, Lonza, Walksville, MD), and then seeded on Transwell membranes (Corning, New York, NY) as described previously [27, 28]. Cells were grown at air liquid interface until terminally differentiated for 4–5 weeks using PneumaCult ALI media (StemCell technology). The UAB Institutional Review Board approved use of primary human cells.

Cigarette smoke extract preparation and exposure to cells with treatments

Cigarette smoke extract were generated using filtered cigarettes (3R4F: University of Kentucky, USA) and absorbed on Dimethyl Sulphoxide (DMSO), then sterile filtered before using in cell culture and stored at − 80 °C for further use [29, 30]. Differentiated epithelial cells were treated with 1% CSE or vehicle control apically and/or apical treatment by HA (0.3%) or vehicle control (1 µL) for 24 h.

µOCT imaging and analysis

To assess the functional microanatomy in cell culture, µOCT imaging was performed before and 24 h after treatment conditions, as described [31–33]. Airway surface liquid (ASL), periciliary layer (PCL) depth, ciliary beat frequency (CBF), and mucociliary transport rates (MCT) were measured using Image J (NIH) and customized MatLab scripts available from UAB or MGH. MCT was determined tracking native mucus particles over time. For each measure, at least 5 random locations (or trackable particles) per region of interest (ROI) were obtained and averaged, and for each monolayer, 4 systematically obtained ROIs were averaged to obtain a single value per monolayer. Data were analyzed by two or three operators blinded to treatment assignment and presented as single average per monolayer for which quantitative statistics were performed. Statistical analysis used repeated measure ANOVA with Sidak’s post hoc testing.

Results

Patient population

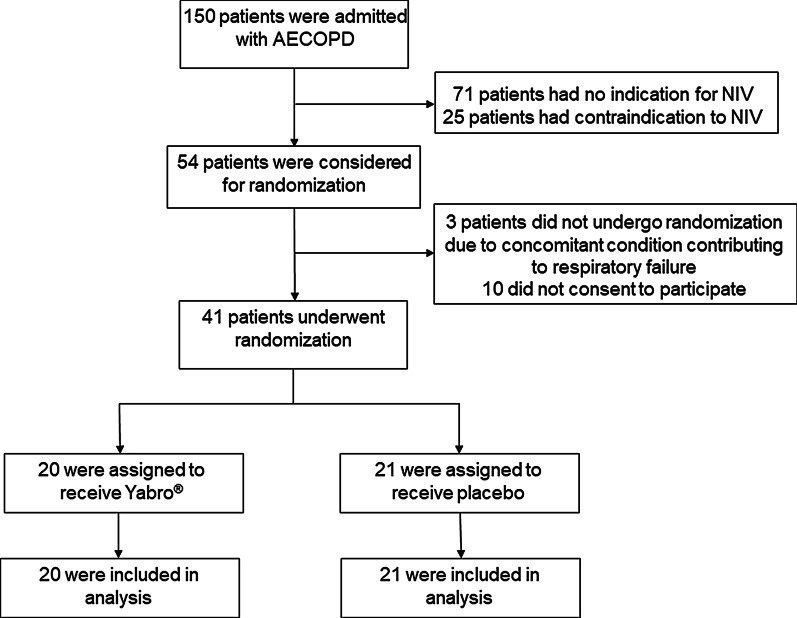

The physicians at Campus Biomedico have developed a home care monitoring system based on wearable sensors which allows detection of AECOPD in early stages [34]. Accordingly, most patients with AECOPD are treated at home. Selected patients are admitted to a day hospital for lab analyses and imaging, as needed, to optimize their home care. Thus, only patients who failed to improve after these interventions were hospitalized. In the period from March 2016 to July 2019, 150 patients were admitted with AECOPD. Of these, 71 had no indication for NIPPV, 25 had contraindications to NIPPV, and 10 refused to consent to the study. Of the remaining 44 who were screened for eligibility to the study, 41 were included, while 3 were excluded because they were deemed to have a concomitant condition (congestive heart failure) that contributed significantly to their presentation (Fig. 1). Twenty patients received HMW-HA and 21 received placebo. Baseline characteristics of the two groups were similar for demographics, medical history, admission lung physiology and laboratory parameters (Table 1). There was no difference in the rate of adverse events in the two treatment groups: One patient in the HMW-HA group suffered a fatal upper gastrointestinal tract hemorrhage (from pre-existing peptic ulcer disease), one patient in the placebo group suffered a hydropneumothorax, and were thus withdrawn for further study. Three more patients withdrew consent (N = 2 for placebo, N = 1 for HMW-HA), and were censored as “not liberated from NIPPV” for intention-to-treat analyses. Another patient in the placebo group progressed to respiratory failure necessitating mechanical ventilation and ultimately died. Complications after HMW-HA or placebo inhalation were specifically tracked, and none were reported.

Fig. 1.

Study schema. Of 150 patients admitted with AECOPD during the study period, 51 were eligible to participate and 41 consented to be included in the study

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients included in this study

| Placebo | HMW-HA (Yabro®) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| N | 21 | 20 | |

| Age | 74.2 ± 10 | 77.4 ± 8.5 | 0.85 |

| Male (%) | 35 | 35 | 1.00 |

| Medical History (% of patients with history) | |||

| Home O2 therapy | 57 | 55 | 1.00 |

| COPD exacerbation requiring hospitalization in past year | 43 | 30 | 0.52 |

| Home NIV use | 19 | 15 | 1.00 |

| Coronary Artery Disease | 57 | 60 | 0.85 |

| Neurovascular Disease | 9.5 | 25 | 0.19 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 19 | 25 | 0.64 |

| Diabetes | 29 | 40 | 0.44 |

| Hypertension | 62 | 85 | 0.09 |

| Past Pneumonia | 38 | 25 | 0.37 |

| Peptic Ulcer Disease | 0 | 15 | 0.06 |

| IADL Score | 4.9 ± 2.6 | 4.7 ± 2.0 | 0.83 |

| Admission Vital Signs | |||

| Mean arterial pressure (mmHg) | 89 ± 9 | 87 ± 12 | 0.70 |

| Heart Rate (per minute) | 75 ± 10 | 81 ± 11 | 0.10 |

| Respiratory Rate (per minute) | 27 ± 5 | 27 ± 4 | 0.73 |

| Temperature (°C) | 36.0 ± 0.4 | 35.9 ± 0.5 | 0.47 |

| Body Mass Index | 26.9 ± 8.6 | 24.7 ± 5.7 | 0.50 |

| Admission Respiratory Parameters | |||

| FiO2 (%) | 27 ± 8 | 29 ± 7 | 0.38 |

| PaO2 (mmHg) | 62 ± 12 | 60 ± 15 | 0.59 |

| PaCO2 (mmHg) | 66 ± 13 | 63 ± 9 | 0.40 |

| pH | 7.34 ± 0.04 | 7.34 ± 0.04 | 0.95 |

| IPAP | 16.1 ± 3.4 | 16.3 ± 3.8 | 0.70 |

| PEEP | 6.1 ± 1.1 | 5.5 ± 0.7 | 0.10 |

| Admission Laboratory Values | |||

| Na (mEq/L) | 138 ± 3 | 139 ± 3 | 0.96 |

| K (mEq/L) | 4.1 ± 0.4 | 4.0 ± 0.5 | 0.21 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.0 ± 0.5 | 1.0 ± 0.6 | 0.96 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 40.2 ± 6.4 | 39.8 ± 12.1 | 0.90 |

| WBC (× 1,000 cells/µL) | 10.2 ± 4.2 | 9.8 ± 3.9 | 0.74 |

| APACHE II score | 14.9 ± 2.7 | 14.7 ± 3.7 | 0.85 |

| Positive sputum culture | 4/21# | 3/20* | 1.00 |

Groups do not differ with regards to demographics, medical history, or admission vital signs, respiratory parameters or laboratory values (entered as average ± SD). p-values calculated by Student’s t-test or Wilcoxon (depending on normality of the data), or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. IADL = Score for Instrumental Activities of Daily Living [58]. FiO2 = fraction of inhaled oxygen. PaO2 = Partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood. PaCO2 = Partial pressure of carbon dioxide in arterial blood. IPAP = inspiratory positive airway pressure. PEEP = positive end-expiratory pressure. WBC = white blood cell count. APACHE = Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation [59]

# One patient each with methicillin-resistant S. aureus, K. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa, and E. coli + P. aeruginosa

* One patient each with methicillin-resistant S. aureus, H. influenzae, and E. coli + H. influenzae + P. aeruginosa

Duration of non-invasive ventilation

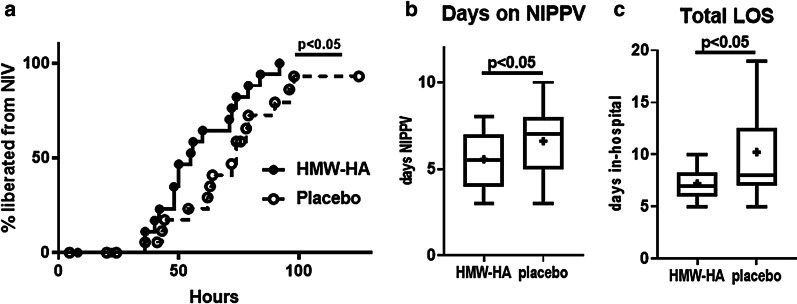

The primary outcome for this study was cumulative duration on NIPPV. We found that patients treated with HMW-HA were liberated from NIPPV significantly faster than placebo-treated patients (Fig. 2a). The effect was clinically significant: on average, patients treated with HMW-HA were liberated from NIPPV more than a day earlier than placebo-treated patients: average days on NIPPV: 5.2 ± 0.4 for HMW-HA vs. 6.4 ± 0.5 days for placebo, (average ± SEM), 5 ± 3 vs. 7 ± 3 (median ± IQR), p = 0.037, t-test) (Fig. 2b). This was associated with overall shortened total length of stay (LOS) in the hospital: average ± SEM 7.2 ± 0.3 for HMW-HA vs. 10.2 ± 1.3 days for placebo, median ± IQR 7 ± 2.25 vs. 8 ± 5.5, p = 0.039 by Mann–Whitney (Fig. 2c). These data suggest that HMW-HA shortened the duration of acute respiratory failure, need for NIPPV and consequently hospital LOS in these patients.

Fig. 2.

HMW-HA treatment reduces duration of NIPPV in AECOPD. a Kaplan–Meier curve of cumulative hours on NIPPV in intention-to-treat analysis. HMW-HA treated patients have significantly shorter time to liberation from NIPPV N = 20 for HMW-HA patients, N = 21 for placebo patients, intention-to-treat analysis. Patients who suffered an adverse event and were withdrawn from the study (N = 1 from each group), or withdrew consent (N = 2 for placebo, N = 1 for HMW-HA), were censored as “not liberated from NIPPV” for this analysis. One patient in the placebo group failed NIPPV, was orotracheally intubated and was censored as “not liberated from NIPPV” at 125 h (point of intubation). b Duration of NIPPV measured in hospital days. HMW-HA treated patients were liberated from NIPPV on average 1 day earlier compared to placebo-treated patients. N = 18 for both groups (2 patients in placebo group and one in HMW-HA group withdrew consent, and one patient each suffered an adverse event and was withdrawn from the study by the study physician). c Total length of stay. HMW-HA treated patients were discharged from the hospital on average 2 days earlier. N = 18 for both groups (explanation as in b)

Respiratory function effects

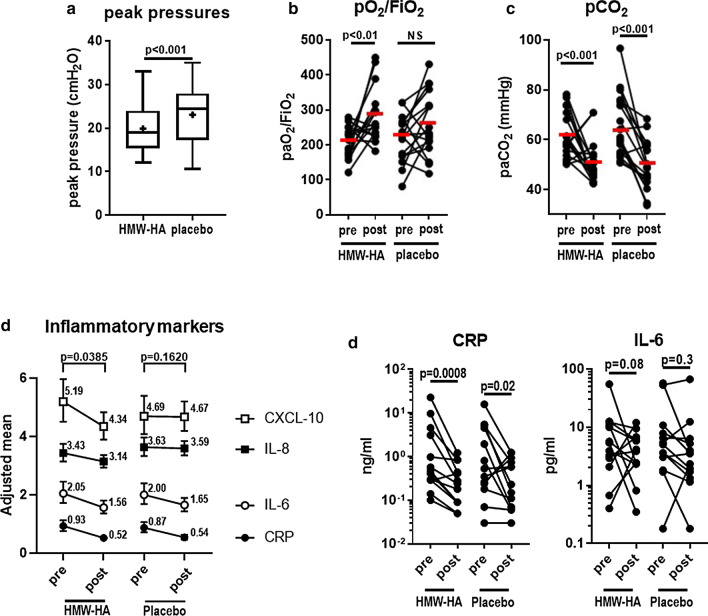

Patients treated with HMW-HA had significantly lower peak pressures reported by the ventilator software (Fig. 3a). Arterial blood gas values improved, as expected, with treatment. Interestingly, the pO2/FiO2 ratio improved significantly only in the HMW-HA treated group, comparing admission and day of liberation from NIPPV (from 210 ± 46 to 284 ± 78, p = 0.011) and not in the placebo group (from 218 ± 66 to 261 ± 91, p = 0.085) (Fig. 3b). Notably, because samples were obtained at the day of liberation from NIPPV and not on a fixed day after initiation of NIPPV, these samples were obtained on average a day earlier in the HMW-HA group. pCO2 values improved significantly in both groups (Fig. 3c), possibly reflecting the fact that pCO2 values were part of the clinical decision-making process for liberation from NIPPV. In aggregate, these results suggest improved lung function in association with HMW-HA treatment.

Fig. 3.

Improved lung function and serum markers of inflammation in HMW-HA treated patients. a HMW-HA-treated patients have lower peak pressures, as recorded by the NIV apparatus, throughout NIVVP. b paO2/FiO2 ratio improves significantly in HMW-HA patients. c paCO2 improves significantly in both groups. N = 17 per group. d Joint analysis of 4 serum inflammatory markers shows a significant improvement in HMW-HA treated patients, but not in placebo patients. e Among the 2 inflammatory markers (CRP and IL-6) that decreased with treatment in both groups in a, more robust improvement can be seen in HMW-HA patients compared to placebo-treated patients. N = 13 per group

Systemic markers of inflammation

For logistical reasons, we only evaluated serum markers of inflammation on admission and on the day of liberation from NIPPV. Unfortunately, some samples were destroyed inadvertently while in transit from Italy to the US lab for analysis, therefore only 13 samples per group could be analyzed. When we tested 3-way interaction of treatment effect with timing (pre-post) and inflammation marker, we did not observe a significant difference between HMW-HA and placebo. In both groups, acute phase inflammation marker values generally decreased over time, reflecting the general health improvement for patients. Interestingly however, HMW-HA-treated patients had a more pronounced response in inflammation markers than placebo-treated patients. When we ran separate models for each group, in placebo patients the timing-effect interaction lost significance (p = 0.162), while in HMW-HA-treated patients the timing-effect interaction remained significant (p = 0.039) (Fig. 3d). When we analyzed acute phase inflammation markers separately, there was a general trend for HMW-HA-treated patients to have more robust effects (e.g. CRP in placebo patients decreased from a natural logarithm-transformed value of -0.142 to -0.615 (p = 0.02) while the HMWHA-treated group decreased from -0.072 to -0.651 (p = 0.0008). Similar effects could be observed in the other 3 cytokines and chemokines measured (Fig. 3d, e). Together, these results suggest that HMW-HA may have beneficial effects in systemic inflammation associated with AECOPD.

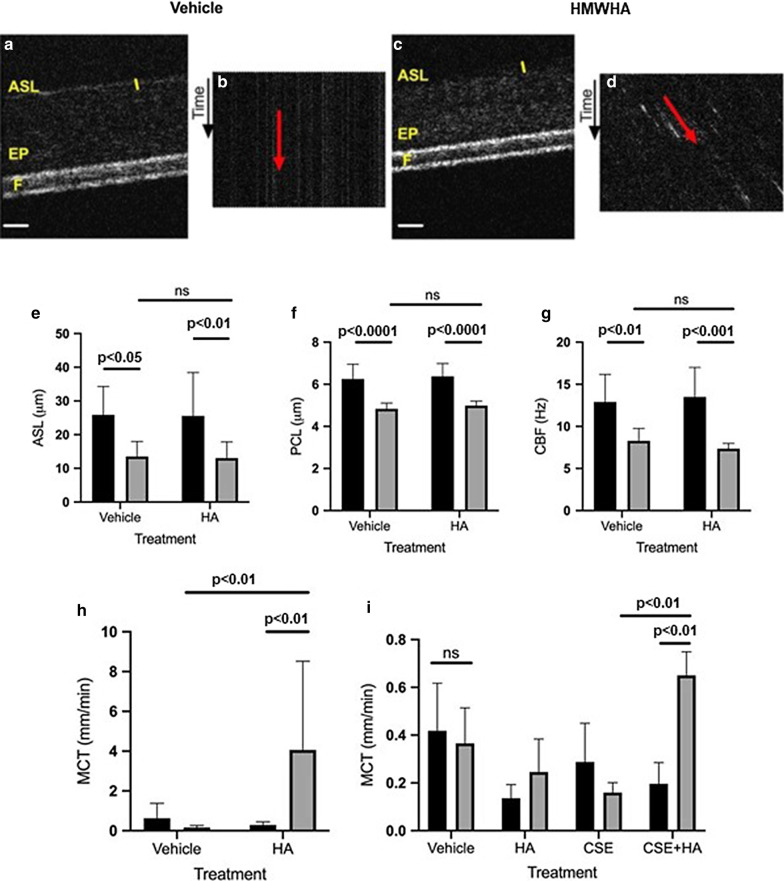

Air–liquid interface cultures

To investigate the mechanism of HMW-HA-induced improvement in lung function and liberation from NIPPV, we conducted an in vitro study using primary human bronchial epithelial (HBE) cells derived from patients with COPD. In other experiments we studied HBE cells from healthy non-smokers exposed to cigarette smoke extract (CSE). We evaluated functional microanatomy using µOCT before and after addition of HMW-HA in comparison to vehicle control (Fig. 4). Representative cross-sectional images (Fig. 4a, c) and quantitative data (Fig. 4e-g) showed no meaningful treatment-related differences on ASL or PCL depth or CBF; however, a prominent effect on mucociliary transport (MCT) with HA treatment was observed on cells from COPD patients (Fig. 4b, d, h). Similarly, cells from healthy non-smokers exposed to CSE exhibited improved MCT with HMW-HA treatment (Fig. 4i). These results suggest that patients with COPD or active smokers may derive a beneficial effect from HMW-HA through improved mucociliary transport function.

Fig. 4.

Mucociliary transport is augmented by HMW-HA. a–h Terminally-differentiated primary HBE monolayers derived from patients with COPD were treated with HMW-HA (0.3%) or an equal volume of vehicle control, then assessed at baseline and after 24 h by µOCT. Representative cross-sectional µOCT images at 24 h after vehicle (a) or HA (c) treatment. EP = epithelial monolayer; ASL depth denoted with yellow bar; F = transwell filter; white scale bar = 20 µm. Streak diagram showing time-dependent reprocessing for vehicle (b) or HA (d) are also shown. The angle of the streaks, as denoted by the red arrow, correspond to MCT rates. Quantitation of airway surface liquid (ASL) depth (e), periciliary layer (PCL) depth (f), ciliary beat frequency (CBF, g), and mucociliary transport (MCT) rate (h). N = 8 monolayers/condition derived from 2 different donors. i MCT from similar study conducted from HBE cells derived from a lung-healthy donor treated with CSE (1%, apically) and vehicle control or HMW-HA (0.3% apically) for 24 h. N = 12 monolayers/condition derived from 3 different donors. ns not significant

Discussion

In this work we demonstrate that treatment with inhaled HMW-HA shortens the duration of acute respiratory failure and is associated with improved lung function and systemic inflammation in patients with AECOPD. Mechanistically, we show that HMW-HA improves mucociliary transport in airway epithelia that exhibit COPD-like manifestations. Our study shows for the first time the therapeutic potential of an extracellular matrix molecule in acute exacerbation of human lung disease.

HMW-HA had a clinically meaningful salutary effect in the primary outcome, duration of NIPPV. These results will need to be confirmed in larger studies but would suggest an important role of HMW-HA in the treatment of AECOPD, since they demonstrate added benefit in patients who were already receiving state-of-the-art AECOPD therapy. Duration of intensive care is independently associated with in-hospital mortality in AECOPD [35] and is also a strong driver of inpatient costs [36]. HMW-HA-treated patients also had a significantly shortened overall inpatient LOS. Thus, HMW-HA is of potential benefit to patients and health systems.

HMW-HA is found in high concentrations in the lung matrix under physiological conditions [37] and is detectable on the luminal surface of airway epithelia [38]. However, during acute inflammation HMW-HA is degraded to smaller fragments [12, 39, 40], which have strong pro-infammatory properties [41]. Accumulation of HA fragments appears to be a common thread in many chronic lung diseases [42], including COPD [43, 44]. This process appears to be proportional to disease activity; HA levels in sputum and blood have been associated with COPD severity, degree of inflammation and patient survival [45, 46]. Emerging evidence suggests that imbalance between declining HMW-HA levels, and increasing smaller fragments of HA may contribute to chronic airway disease pathogenesis [47]. This has led to the hypothesis, that exogenous supplementation of HMW-HA may restore HA homeostasis in favor of undegraded molecules, inhibit inflammation and loss of lung function and ameliorate COPD progression [48]. Aerosolized HA was found to reverse emphysema induced by neutrophil elastase [49] and cigarette smoke [50] in animal models, although the precise mechanism remains unclear. Our work adds to the existing evidence for therapeutic utility of HA in COPD, by demonstrating beneficial effects in AECOPD, and a connection to improved mucus clearance.

HMW-HA possesses several beneficial properties which make it an attractive candidate as an exogenously administered treatment option in inflammatory lung disease. HMW-HA is a naturally occurring sugar [37], and therefore is expected to be well tolerated. Indeed, our study did not demonstrate any apparent adverse effects with Yabro® inhalation. This is not unexpected; inhaled HMW-HA has been used routinely, together with hypertonic saline, in cystic fibrosis patients with no reported side effects; rather it improves tolerability and decrease the need for bronchodilators in these patients [51, 52]. In addition, HMW-HA is very hydrophilic [10]. This property may contribute to the improvement in airway pressures observed in HMW-HA-treated patients. Interestingly, the hydrating effect did not seem to contribute significantly in the improvement in MCT seen in our in vitro study. MCT is dictated primarily by ciliary function and mucus rheology. While short fragments of HA have been shown to increase CBF [38], HMW-HA does not have such an effect, as we showed in this study as well. Furthermore, the ASL and PCL dimensions did not change with HMW-HA, arguing against a significant effect on the hydration status of the mucus layer. However, HMW-HA (but interestingly, not low-MW HA) changes the nanostructure of mucin, possibly through entanglement with mucin proteins [53] and could thus improve the functional rheology of the mucociliary layer [47] and promote MCT through this mechanism. In support of this interpretation, recent studies have shown that normalizing mucin structure can improve MCT in cystic fibrosis airways [54].

HMW-HA also has potent anti-inflammatory and pro-homeostatic properties. In murine models, HMW-HA ameliorates acute allergic and non-allergic inflammation [14, 55, 56] and lung epithelial injury [16, 18]. Ex vivo, HMW-HA inhibited LPS-induced TNFα release by whole blood from COPD patients [57]. Thus, HMW-HA may ameliorate airway inflammation in AECOPD as well. We were not able to collect sputum in order to quantify lung inflammation markers. However, serum inflammatory markers seemed to respond favorably to inhaled HMW-HA. While no single biomarker has yet been shown to be highly predictive of outcomes in AECOPD, we analyzed markers that have been associated with AECOPD [20–24]. In aggregate, our analysis suggested that HMW-HA treatment resulted in greater improvement in serum inflammatory markers over time, compared to placebo (Fig. 3). In addition, it should be noted that, since the serum samples were collected at the end of NIPPV, HMW-HA-treated patients were on average sampled a day earlier than placebo-treated patients (because they were liberated from NIPPV a day earlier on average, Fig. 2). Thus, HMW-HA treatment effects may have been underestimated in our study. Studies with a higher number of patients and more frequent sampling strategies will help confirm this observed trend.

Another mechanism of improved lung function by HMW-HA administration may be reduction of bronchial constriction. Several studies have shown that HMW-HA ameliorates inflammation-associated airway hyperresponsiveness in murine models [12–14] and in humans [15]. The observed lower peak airway pressures in HMW-HA patients, observed in our study, would suggest that airway resistance was reduced in these patients. We did not observe any difference in documented tidal volumes throughout the study duration (not shown), but this could be due to changes in ventilatory support dictated by the patients’ clinical status.

There are several limitations to this pilot study. Due to the small number of patients and the single-center nature of the study, its results would certainly need to be validated and replicated in larger studies. This study stretched over 2–3 years, thus introducing a potential variability in treatment approaches. However, this was at least partially counteracted by the fact that only 2 dedicated physicians led the treatment of recruited patients throughout the study duration. We unfortunately did not have background information regarding lung function or baseline blood gas values in these patients, and therefore we cannot fully comment on the severity of pre-existing COPD. However, the two groups were well-matched with regard to clinical parameters, i.e. home O2 and NIPPV use, thus we would expect that there were no significant differences in lung function either. Also, as described in “Methods” section, our COPD patients were managed with a telemedicine approach which significantly reduces the need for hospitalization [34]. Thus, only relatively treatment-resistant cases were admitted and shuttled into the randomization schema. This may also explain why our documented pH values at admission were only borderline acidemic, despite significant elevation of pCO2: these were not patients with hyperacute exacerbation, but rather progressively declining patients who failed to respond to outpatient management, and therefore had time to at least partially compensate their acid–base status. Finally, these patients represent cases of community- “acquired” COPD exacerbation, and therefore it is not clear if HMWHA benefits also apply to cases of deterioration in the inpatient setting, or in the case of patients that need invasive ventilation.

Conclusion

Inhaled HMWHA may be beneficial in severe AECOPD, by improving inflammation and lung function, and reducing the need for ventilatory support. Our study supports the use of a novel class of treatment, i.e. matrix biologics, in acute and chronic lung disease. Additional studies should confirm our findings with higher number of patients in additional clinical sites and explore the use of HMWHA in chronic COPD, both to reduce COPD progression and to decrease exacerbations which are the major driver of morbidity, mortality and cost in this devastating disease.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the patients who consented to participate in this study, and the staff who cared for them.

Abbreviations

- AECOPD

Acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- APACHE

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation

- ASL

Airway surface liquid

- CBF

Ciliary beat frequency

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- CXCL10

C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 10

- FiO2

Fraction of inhaled oxygen

- HMW-HA

High molecular weight hyaluronic acid (hyaluronan)

- IADL

Score for Instrumental Activities of Daily Living

- IL-6

Interleukin 6

- IL-8

Interleukin 8

- IPAP

Inspiratory positive airway pressure

- MCT

Mucociliary transport rate

- μOCT

One-micron optical coherence tomography

- NIPPV

Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation

- PaCO2

Partial pressure of carbon dioxide in arterial blood

- PaO2

Partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood

- PCL

Periciliary layer depth

- PEEP

Positive end-expiratory pressure

- WBC

White blood cell count

Authors’ contributions

RAI and SG designed and supervised the study. FG and CP recruited and treated patients in this protocol. CAM, MG, ABR performed laboratory analyses. JAM and ARB contributed to data management and statistical analyses. SSH, KV, ERB, KJT, and SMR performed and analyzed the optical coherence tomography data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported in part by funds from the Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, ES102605 and ES102465 (SG), and extramural grants from the NIH (R35 HL135816 and P30DK072482 (SMR)).

Availability of data

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was carried out in accordance with the principles of the declaration of Helsinki and approved by the local Ethics Committee at the University of Rome (NCT02674880, Local IRB Protocol Number: 15.15PT ComEt-CBM).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest for this article.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Raffaele A. Incalzi and Stavros Garantziotis are equal contribution as senior authors

References

- 1.World Health Organization Website. Chronic Respiratory Diseases: Burden of COPD. Accessed 15 May 2020.

- 2.. Health, United States, 2016: With Chartbook on Long-term Trends in Health. Hyattsville (MD); 2017. [PubMed]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COPD Costs. https://www.cdc.gov/copd/infographics/copd-costs.html. Accessed 15 May 2020.

- 4.Seemungal TA, Donaldson GC, Bhowmik A, Jeffries DJ, Wedzicha JA. Time course and recovery of exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(5):1608–1613. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.5.9908022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lim S, Lam DC, Muttalif AR, et al. Impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in the Asia-Pacific region: the EPIC Asia population-based survey. Asia Pac Fam Med. 2015;14(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s12930-015-0020-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andersson F, Borg S, Jansson SA, et al. The costs of exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) Respir Med. 2002;96(9):700–708. doi: 10.1053/rmed.2002.1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hutchinson A, Brand C, Irving L, Roberts C, Thompson P, Campbell D. Acute care costs of patients admitted for management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations: contribution of disease severity, infection and chronic heart failure. Intern Med J. 2010;40(5):364–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2010.02195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khakban A, Sin DD, FitzGerald JM, et al. Ten-Year Trends in Direct Costs of COPD: A Population-Based Study. Chest. 2015;148(3):640–646. doi: 10.1378/chest.15-0721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mulpuru S, McKay J, Ronksley PE, Thavorn K, Kobewka DM, Forster AJ. Factors contributing to high-cost hospital care for patients with COPD. Int J Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Dis. 2017;12:989–995. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S126607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ogston AG, Stanier JE. The dimensions of the particle of hyaluronic acid complex in synovial fluid. Biochem J. 1951;49(5):585–590. doi: 10.1042/bj0490585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pignataro L, Marchisio P, Ibba T, Torretta S. Topically administered hyaluronic acid in the upper airway: a narrative review. Int J ImmunopatholPharmacol. 2018;32:2058738418766739. doi: 10.1177/2058738418766739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garantziotis S, Li Z, Potts EN, et al. Hyaluronan mediates ozone-induced airway hyperresponsiveness in mice. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(17):11309–11317. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802400200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- 13.Lazrak A, Creighton J, Yu Z, et al. Hyaluronan mediates airway hyperresponsiveness in oxidative lung injury. Am J Physiol. 2015;308(9):L891–903. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00377.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson CG, Stober VP, Cyphert-Daly JM, et al. High molecular weight hyaluronan ameliorates allergic inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness in the mouse. Am J Physiol. 2018;315(5):L787–L798. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00009.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petrigni G, Allegra L. Aerosolised hyaluronic acid prevents exercise-induced bronchoconstriction, suggesting novel hypotheses on the correction of matrix defects in asthma. PulmPharmacolTher. 2006;19(3):166–171. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou T, Yu Z, Jian MY, et al. Instillation of hyaluronan reverses acid instillation injury to the mammalian blood gas barrier. Am J Physiol. 2018;314(5):L808–L821. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00510.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang D, Liang J, Fan J, et al. Regulation of lung injury and repair by Toll-like receptors and hyaluronan. Nat Med. 2005;11(11):1173–1179. doi: 10.1038/nm1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liang J, Zhang Y, Xie T, et al. Hyaluronan and TLR4 promote surfactant-protein-C-positive alveolar progenitor cell renewal and prevent severe pulmonary fibrosis in mice. Nat Med. 2016;22(11):1285–1293. doi: 10.1038/nm.4192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wedzicha JAC, Miravitlles M, Hurst JR, et al. Management of COPD exacerbations: a European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society guideline. EurRespir J. 2017;49:3. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00791-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bafadhel M, McKenna S, Terry S, et al. Acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: identification of biologic clusters and their biomarkers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184(6):662–671. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201104-0597OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wedzicha JA, Seemungal TA, MacCallum PK, et al. Acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are accompanied by elevations of plasma fibrinogen and serum IL-6 levels. ThrombHaemost. 2000;84(2):210–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sneh A, Pawan T, Randeep G, et al. Acute phase proteins as predictors of survival in patients with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease requiring mechanical ventilation. Copd. 2020;17(1):22–28. doi: 10.1080/15412555.2019.1698019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gallego M, Pomares X, Capilla S, et al. C-reactive protein in outpatients with acute exacerbation of COPD: its relationship with microbial etiology and severity. Int J Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Dis. 2016;11:2633–2640. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S117129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jonsdottir B, Jaworowski A, San Miguel C, Melander O. IL-8 predicts early mortality in patients with acute hypercapnic respiratory failure treated with noninvasive positive pressure ventilation. BMC Pulmonary Med. 2017;17(1):35. doi: 10.1186/s12890-017-0377-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tao J KK, Gibbs P, SAS Institute Inc. SAS Paper 1919–2015. Advanced Techniques for Fitting Mixed Models Using SAS/STAT Software. 2020; https://support.sas.com/resources/papers/proceedings15/SAS1919-2015.pdf. Accessed 11 April 2020.

- 26.Osadnik CR, McDonald CF, Jones AP, Holland AE. Airway clearance techniques for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;3:CD008328. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008328.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karmouty-Quintana H, Weng T, Garcia-Morales LJ, et al. Adenosine A2B receptor and hyaluronan modulate pulmonary hypertension associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2013;49(6):1038–1047. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0089OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.You Y, Richer EJ, Huang T, Brody SL. Growth and differentiation of mouse tracheal epithelial cells: selection of a proliferative population. Am J Physiol. 2002;283(6):L1315–1321. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00169.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin VY, Kaza N, Birket SE, et al. Excess mucus viscosity and airway dehydration impact COPD airway clearance. EurRespir J. 2020;55:1. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00419-2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raju SV, Lin VY, Liu L, et al. The cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator potentiator ivacaftor augments mucociliary clearance abrogating cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator inhibition by cigarette smoke. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2017;56(1):99–108. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2016-0226OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Birket SE, Chu KK, Liu L, et al. A functional anatomic defect of the cystic fibrosis airway. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190(4):421–432. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201404-0670OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Birket SE, Chu KK, Houser GH, et al. Combination therapy with cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator modulators augment the airway functional microanatomy. Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2016;310(10):L928–L939. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00395.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu L, Chu KK, Houser GH, et al. Method for quantitative study of airway functional microanatomy using micro-optical coherence tomography. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(1):e54473. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pedone C, Chiurco D, Scarlata S, Incalzi RA. Efficacy of multiparametrictelemonitoring on respiratory outcomes in elderly people with COPD: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:82. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brown H, Dodic S, Goh SS, et al. Factors associated with hospital mortality in critically ill patients with exacerbation of COPD. Int J Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Dis. 2018;13:2361–2366. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S168983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dalal AA, Christensen L, Liu F, Riedel AA. Direct costs of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among managed care patients. Int J Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Dis. 2010;5:341–349. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S13771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jiang D, Liang J, Noble PW. Hyaluronan in tissue injury and repair. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2007;23:435–461. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Forteza R, Lieb T, Aoki T, Savani RC, Conner GE, Salathe M. Hyaluronan serves a novel role in airway mucosal host defense. FASEB J. 2001;15(12):2179–2186. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0036com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garantziotis S, Li Z, Potts EN, et al. TLR4 is necessary for hyaluronan-mediated airway hyperresponsiveness after ozone inhalation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181(7):666–675. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200903-0381OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- 40.Liang J, Jiang D, Jung Y, et al. Role of hyaluronan and hyaluronan-binding proteins in human asthma. J Allergy ClinImmunol. 2011;128(2):403–411. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garantziotis S, Brezina M, Castelnuovo P, Drago L. The role of hyaluronan in the pathobiology and treatment of respiratory disease. Am J Physiol. 2016;310(9):L785–L795. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00168.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lauer ME, Dweik RA, Garantziotis S, Aronica MA. The Rise and Fall of Hyaluronan in Respiratory Diseases. Int J Cell Biol. 2015;2015:712507. doi: 10.1155/2015/712507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Papakonstantinou E, Roth M, Klagas I, Karakiulakis G, Tamm M, Stolz D. COPD exacerbations are associated with pro-inflammatory degradation of hyaluronic acid. Chest. 2015;8:9. doi: 10.1378/chest.15-0153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cantor J, Armand G, Turino G. Lung hyaluronan levels are decreased in alpha-1 antiprotease deficiency COPD. Respir Med. 2015;109(5):656–659. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2015.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dentener MA, Vernooy JH, Hendriks S, Wouters EF. Enhanced levels of hyaluronan in lungs of patients with COPD: relationship with lung function and local inflammation. Thorax. 2005;60(2):114–119. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.020842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Papakonstantinou E, Bonovolias I, Roth M, et al. Serum levels of hyaluronic acid are associated with COPD severity and predict survival. EurRespir J. 2019;53:3. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01183-2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Matuska B, Comhair S, Farver C, et al. Pathological Hyaluronan Matrices in Cystic Fibrosis Airways and Secretions. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2016;55(4):576–585. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2015-0358OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Turino GM, Ma S, Lin YY, Cantor JO. The Therapeutic Potential of Hyaluronan in COPD. Chest. 2018;153(4):792–798. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cantor JO, Cerreta JM, Armand G, Turino GM. Aerosolized hyaluronic acid decreases alveolar injury induced by human neutrophil elastase. ProcSocExp Biol Med. 1998;217(4):471–475. doi: 10.3181/00379727-217-44260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cantor JO, Cerreta JM, Ochoa M, Ma S, Liu M, Turino GM. Therapeutic effects of hyaluronan on smoke-induced elastic fiber injury: does delayed treatment affect efficacy? Lung. 2011;189(1):51–56. doi: 10.1007/s00408-010-9271-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Furnari ML, Termini L, Traverso G, et al. Nebulized hypertonic saline containing hyaluronic acid improves tolerability in patients with cystic fibrosis and lung disease compared with nebulized hypertonic saline alone: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, controlled study. TherAdvRespir Dis. 2012;8:987. doi: 10.1177/1753465812458984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ros M, Casciaro R, Lucca F, et al. Hyaluronic acid improves the tolerability of hypertonic saline in the chronic treatment of cystic fibrosis patients: a multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial. J Aerosol Med Pulmonary Drug Delivery. 2014;27(2):133–137. doi: 10.1089/jamp.2012.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hansen IM, Ebbesen MF, Kaspersen L, et al. Hyaluronic acid molecular weight-dependent modulation of mucin nanostructure for potential mucosal therapeutic applications. Mol Pharm. 2017;14(7):2359–2367. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.7b00236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fernandez-Petty CM, Hughes GW, Bowers HL, et al. A glycopolymer improves vascoelasticity and mucociliary transport of abnormal cystic fibrosis mucus. JCI Insight. 2019;4:8. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.125954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Muto J, Yamasaki K, Taylor KR, Gallo RL. Engagement of CD44 by hyaluronan suppresses TLR4signaling and the septic response to LPS. MolImmunol. 2009;47(2–3):449–456. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gebe JA, Yadava K, Ruppert SM, et al. Modified High Molecular Weight Hyaluronan Promotes Allergen-Specific Immune Tolerance. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2016;23:78. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2016-0111OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dentener MA, Louis R, Cloots RH, Henket M, Wouters EF. Differences in local versus systemic TNFalpha production in COPD: inhibitory effect of hyaluronan on LPS induced blood cell TNFalpha release. Thorax. 2006;61(6):478–484. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.053330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9(3):179–186. doi: 10.1093/geront/9.3_Part_1.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13(10):818–829. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198510000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.