Abstract

In this present study, solid desiccant-based pressure-swing adsorption (PSA) dehumidifier was developed and the process parameters were optimized to deliver the air continuously at 0.1% relative humidity. Mint (Mentha arvensis) leaves are tested to study the drying characteristics at varied flow rates of dehumidified air in the drying chamber. The initial moisture content of 5.059 g water/g dry matter have been reduced to a safe storage level in 360 min at 0.160 m3/min volume low rate. The effective moisture diffusivity of the mint leaves was found in the range of 2.07534 × 10−11m2/s to 3.45817 × 10−11m2/s. The percentage of retention of ascorbic acid in dried mint leaves is increased by an increase in the volume flow rate of dry air and a maximum of 70.11% is achieved by 0.160 m3/min. The colour measurement and chlorophyll content of the dried samples indicated that the desiccant dehumidified air dryers are suitable for heat sensitive green leafy vegetables.

Keywords: Mint leaves, Drying, Ascorbic acid retention, Solid desiccants

Introduction

Mints (Mentha species) belong to the family of Labiate (Lamiaceae) and are widely cultivated in several countries like India, China, Brazil, Japan, France, USA and Thailand (Muthukumar and Venkatesh 2014). Mint leaves are one among the major aromatic, gastronomical, nutritional and medicinal plants cultivated in large quantities. Worldwide, several varieties of mint are grown such as water mint (M. aquatica), peppermint (M. piperita), spearmint (Mentha spicata), ginger mint (M. gracilis), garden mint (M. arvensis), horsemint (M. longifolia), pennyroyal (M. pulegium),and pine apple mint (M. suaveolens). Mint leaves are used to treat many diseases like poor digestion, rheumatism, hiccups, flatulence and for sinus ailments etc., (Akpinar 2010). Apart from the medicinal purpose, mint leaves are major source of mint flavour for culinary uses and they are used as fresh or dried leaves. Mint leaves are rich sources of vitamin A, vitamin C, calcium, potassium, iron and phosphorous etc., but it contains more amount water content (75 to 95%). Due to high moisture content, mint leaves are mostly used as fresh or dried to prevent the growth of microorganisms and to reduce some undesirable biochemical reactions. Since ancient times, drying is the commonly used process for extracting water content from agricultural produce. Drying enables us to store the products for longer duration, in addition the weight and volume of the products are also reduced (Vijayan et al. 2017b).

Drying kinetics of the mint leaves have been investigated through different methods of drying like open sun drying, cabinet drying, heat pump drying, solar drying (Sallam et al. 2015; El-Sebaii and Shalaby 2013) etc. The drying process impacts the consistency of the dried goods in terms of quality. Most processes used for drying are of thermal dryers, which is not suitable for heat sensitive green leafy vegetables. Freeze dryers and vacuum dryers are used for drying the heat sensitive products, but they are highly expensive. As an alternative to these methods, desiccant based dehumidified air-drying systems are also used. Owing to the difference in partial pressure of water vapour between the feed air and surface of product, the relative humidity of the air is decreased and the moisture of the product is removed. The use of desiccant-based dehumidifiers has emerged over the last two decades as most suitable method for drying at low temperatures, particularly for heat-sensitive green leafy vegetables or medicinal herbs. There is a wide range of materials, including solid and liquid desiccant, which are designed to reduce feed air humidity in a variety of ways, such as drying, cooling and air conditioning. Among these materials solid desiccant materials are mostly used for drying applications due to their ability to produce dehumidified air with lesser moisture to a very low level (< 0.1% rh). There are numerous solid desiccant materials are used to dehumidify the ambient air like activated alumina, silica gel and molecular sieve etc. The advantageous features like higher affinity to moisture and wide operating temperature of air (up to 55 °C) are made molecular sieve 13× desiccant as one of the most promising materials for dehumidification of air (Kannan and Arjunan 2019; Kannan et al. 2020).

The applications of desiccant based dehumidifier system for low temperature drying of agricultural produce are investigated only by few researchers. Sugar and Suresh (2010) reviewed advanced processes used for drying and dehydration of agricultural products. The study concluded that quality and energy requirement are the key parameters in selecting the drying processes. The review also concluded that low temperature based drying processes have great scope in producing quality dried products. Gurtas Seyhan and Evranuz (2000) developed desiccant based dehumidifier to dry cultivated mushrooms at temperature ranging from 20 to 40 °C. The results revealed that the process air with low temperature and low humidity was effective in decreasing mailard browning reactions in mushrooms. Gichau et al. (2020) predicted the shelf life of amaranth-sorghum grains using sorption-based isotherm models. The investigation revealed that the shelf life is shortened by three-fold at higher temperature than at 25 °C storage temperature air. Hanif et al. (2019) investigated the suitability of solid desiccant dehumidifier to dry harvested wheat grains. The results showed that specific energy consumption to dry the wheat grains was less compared to conventional drying methods for the same quantity. Ramachandra and Rao (2013) studied the free flowness of Aloe vera gel powder produced using desiccant based dry air. The study revealed that dehumidified air yields less colour change and good flowness of powder. The molecular sieve and alumina pillared clay-based adsorption dryer was developed by Djaeni and Boxtel (2009) to study the energy efficiency in multi-stage drying. Results showed that molecular sieve favours more in the temperature range between 10 and 50 °C.

A few researchers integrated desiccant based dehumidifier unit with solar dryers to dehydrate the agricultural products. A silica gel-based adsorption dryer was integrated with flat plate solar collector by Hodali and Bougard (2001) to dry apricots in local climatic conditions of Morocco. The integration yielded improvement in terms of reduction of drying time with good drying quality. Misha et al. (2016) conducted performance study in solid desiccant solar assisted dryer for oil palm drying. The results reveled that drying time is reduced considerably with increase in drying rate with 74% sensible effectiveness and 67% latent effectiveness. Abasi et al. (2017) studied the effect of integration of desiccant unit with convective dryer to dry corn kernels. Results showed that the integration of desiccant unit decreased drying time by 9.75% and increase in drying rate by 7.85% with acceleration in moisture extraction from corn samples.

Previous studies mentioned in the above literature review revealed that solid desiccant-based dryers are highly suitable for dehydrating the heat sensitive agricultural products and only few researchers have investigated the applicability of the dryers. Mint leaves have been dried using different drying methods, however no literature is found with use of desiccant based dryers. Therefore, in this present study a solid desiccant dehumidifier system was developed and the operating conditions were optimized to achieve very low moisture content in the air. Further, the effect of low temperature and low humidity process air on the drying characteristics of mint leaves was also investigated.

Material and methods

Material

Fresh garden mint leaves (Mentha arvensis) from the local farmers of Coimbatore (India) were purchased for each experimental test. Only good quality green leaves selected by removing the damaged and discoloured leaves and they were further cleaned at room temperature with tap water. The excessive moisture on the leaves were removed with the blotting paper.

Estimation of moisture content

The dry mass of the mint leaves was measured by keeping 20 g sample in a convective oven at temperature of 105 °C ± 1 °C temperature for 4 h at atmospheric pressure. The test is repeated for three times and the average initial moisture content in dry basis was estimated as 5.059 ± 0.5889 g water/g dry matter (83.45% wet basis).

Experimental setup

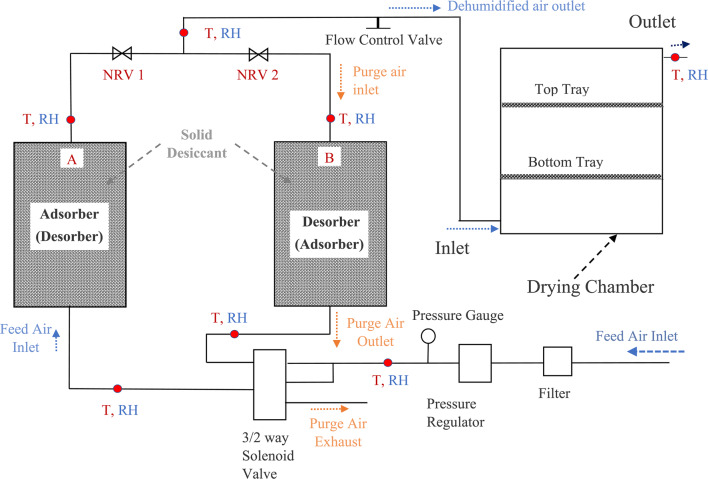

Figure 1 represents the schematic diagram of developed setup. Air compressor, two adsorption columns namely Column A and Column B respectively and a drying chamber are the main elements of the developed setup.

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of the experimental setup

A 5hp and 500 lpm reciprocating air compressor with aftercooler is used to produce feed air at rated pressure. The excess moisture due to compression of air is condensed and drained in the after cooler. Two adsorption columns namely A and B with 76.2 mm diameter and 1400 mm height are alternatively used as adsorber or desorber to ensure continuous dehumidified air output. Both columns have the unsaturated Molecular Sieve 13X desiccant filled in.

The feed air at rated pressure is directed to column A and dehumidification of water vapour is taking place. During this time, column B is in offline mode. The dry air from column A is supplied to drying chamber. Column A is in active mode till the saturation of the desiccant. Upon desiccant saturation, the feed air is redirected to column B, which has unsaturated desiccant to ensure a continuously dehumidified supply of air for drying. Now that column B is in dehumidification mode (online), column A (offline) is being desorbed. The column desorbing air is exhausted into atmosphere through the exit valve.

The drying chamber is the final essential component of the drying system. It was fabricated to the dimensions of 420 mm × 420 mm × 600 mm with GI sheets to dry the products. Two trays of 400 mm × 400 mm dimensions, separated by a 200 mm apart is used to place mint leaves for drying. The drying chamber was insulated with glass wool of 50 mm thickness to reduce the convective heat loss to the surrounding atmosphere.

Instrumentation

The experimental observations were made using the precalibrated instruments. The pressure of the flowing inlet air was measured by means of a pressure gauge mounted after the pressure regulator with the measuring range of 0–20 bar and resolution of 0.01 bar. A thermo-hygrometer (METRAVI-HT3006) was used to measure the relative humidity, dry bulb and dew point temperature of the air at the inlet and outlet of adsorber, desorber and drying chamber (Fig. 1). Vane type anemometer with the measuring range of 0–30 m/s and having accuracy of ± 3% was used to measure the air velocity. A digital electronic weighing machine (Accurate-ATC-10 W) with the measuring range of 0 to 10 kg and having resolution of 1 g was used for the periodic measurement of sample weight.

Experimental procedure

The investigations are carried out in two phases. In the first phase, the optimal parametric condition for the dehumidification process was arrived using Taguchi’s design of experiment in Minitab software. The drying characteristics of leaves were studied in the second phase for varying dry air flow rates from the dehumidifier.

The drying system is supplied with dry air continuously from the desiccant system with 35 °C to 37 °C DBT and 0.1 per cent rh. Mint leaves are dried at different volume flow rates of 0.032 m3/min, 0.064 m3/min, 0.096 m3/min, 0.128 m3/min and 0.160 m3/min and 0.48 m/s to 2.41 m/s. All the experimental runs are carried out from 10.00am until the drying process equilibrium condition is achieved. A sample of 200 g of mint leaves is placed in both drying unit trays during the studies. Drying experiments for each volume flow rate was conducted twice to ensure the consistent performance of the desiccant dryer.

Experimental design for dehumidifier system

The aim of the experimental design is to establish a correlation between the dry air moisture content and the optimum parametric conditions. Optimal parametric conditions are arrived in three steps. In the first step, the influencing parameters are selected and significant parameters are identified using screening experiments. The second step focuses in identifying the optimal conditions of significant parameters. The response of optimal conditions is verified by conducting confirmation experiments.

Based on literature (Venkatachalam et al. 2020), the influencing process parameters are identified and screening experiments were conducted for the minimum and maximum levels of the corresponding parameters. From the results it is concluded that volumetric purge flow to feed flow ratio dominates the most with a contribution of 71.35% in the PSA system response, and with a contribution of 19.83 percent, space velocity comes in second place.

From screening experiments, the significant parameters are identified from the number of influencing parameters in the process. The optimal values of the significant parameters are required to minimize the steady state moisture content in the product air. The optimization experiments are carried out based Taguchi’s design of experiment. It uses orthogonal arrays for experimental runs defining and analysis of variance. The response of the experimental observations is converted into signal to noise ratio to know the deviation from the desired response (Sowrirajan et al. 2017, 2018; Arulraj and Palani 2018; Arulraj et al. 2017).

The significant parameters are identified from screening experiments and are shown in Table 1. Based on the two significant parameters (with levels) namely Volumetric purge to feed ratio (Parameter A:1.1 and 1.2) and Space velocity (Parameter B: 17,26,34 m3/h/kgdes) are optimized based on L18 (6^1 3^1) array design.

Table 1.

Summary of optimization phase experiments

| Run No | Parameters | Response | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | Steady state ppmv H2O | Steady state log (ppmv H2O) | |

| 1 | 1.1 | 17 | 127 | 2.1038 |

| 2 | 1.1 | 17 | 143 | 2.1553 |

| 3 | 1.1 | 17 | 114 | 2.0569 |

| 4 | 1.1 | 26 | 198 | 2.2966 |

| 5 | 1.1 | 26 | 178.5 | 2.2516 |

| 6 | 1.1 | 26 | 198 | 2.2966 |

| 7 | 1.1 | 34 | 509 | 2.7067 |

| 8 | 1.1 | 34 | 452 | 2.6551 |

| 9 | 1.1 | 34 | 509 | 2.7067 |

| 10 | 1.2 | 17 | 2.29 | 0.4756 |

| 11 | 1.2 | 17 | 3.43 | 0.5352 |

| 12 | 1.2 | 17 | 2.29 | 0.4756 |

| 13 | 1.2 | 26 | 49.7 | 1.6963 |

| 14 | 1.2 | 26 | 49.7 | 1.6963 |

| 15 | 1.2 | 26 | 56.5 | 1.752 |

| 16 | 1.2 | 34 | 101 | 2.0043 |

| 17 | 1.2 | 34 | 114 | 2.0569 |

| 18 | 1.2 | 34 | 114 | 2.0569 |

Statistical design of experiments

The experimental results for optimization phase are shown in Table 1. The response data is processed using Minitab 17 statistical software.

Drying

The drying characteristics of the mint leaves was evaluated through the key parameters of drying process such as moisture content, moisture ratio (MR), drying rate (DR) and effective moisture diffusivity .

Determination of moisture content

The initial moisture content on dry basis of mint leaves in mass of moisture per unit mass of dry matter can be expressed as given in Eq. (1) (Kesavan et al. 2019)

| 1 |

where, is the initial weight of the product and is the weight of the dry matter in the product. The instantaneous moisture content on dry basis () during at any time of time (t) can be estimated using the Eq. (2) (Vijayan et al. 2016)

| 2 |

is the weight of product at time t

Moisture ratio (MR)

The moisture ratio (MR) of the drying process was determined (Eq. 3) by neglecting the equilibrium moisture content as it is very small when compared with the initial moisture content of the product (Seshachalam et al. 2017; Vijayan et al. 2017a)

| 3 |

Drying rate (DR)

The drying rate in a drying process determines the rate at which the moisture content is removed from the product and this parameter expresses the effectiveness of the drying system. The drying rate is the variation of moisture content with time and it can be calculated using the Eq. (4),

| 4 |

where, is the moisture content at time

Estimation of effective moisture diffusivity

Effective moisture diffusivity of mint leaves drying process using dehumidified air system can be estimated from Eq. (5)

| 5 |

where, t is the drying time (s), r is the thickness of the slab (m), and Deff is the effective diffusivity coefficient (m2/s). Equation (5) can be converted into straight-line equation as given in Eq. (6) (Vijayan et al. 2020)

| 6 |

The slope of the equation can be determined to estimate the effective moisture diffusivity value of the mint leaves.

Dried samples quality analysis

The method of drying and the operating parameters of the drying process influence the quality of the dried samples. Generally, the drying of agricultural products results in reduction of moisture content along with few undesirable losses like colour, nutritional values, etc. Therefore, the suitability of a particular drying method to a product is analyzed through quality of analysis of the dried samples.

Colour measurement

The colour measurement of the fresh and dried samples were tested using Tintometer RT 200 (Food Quality Testing Laboratory, Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, Coimbatore). CIE L*a*b* (CIELAB) colour space coordinates were adopted for the measurement. In this measurement, ‘L*’ represents lightness index, ‘a*’ represents red–green colour (+ a* indicates redness & −a* greenness), ‘b*’ indicates yellow-blue colour (+ b*-yellowness & −b* blueness). Three measurements were done for each sample and the average value was considered. After every measurement the device was calibrated against a standard colour value. The total colour change for the dried samples (d) were estimated by taking the fresh samples (f) as reference using Eq. (7) (Alwazeer and Örs 2019).

| 7 |

Statistical analysis

The data sets were analysed by means of one-way ANOVA and all pairwise multiple comparison (Holm-Sidak method) test was adopted in Sigmaplot 14.0. Statistical analysis was performed with overall significance level as p < 0.05.

Estimation of chlorophyll content and ascorbic acid

Chlorophyll content and the ascorbic acid (vitamin C) of the fresh and dried mint leaves samples were estimated through the biochemical methods suggested by Ranganna (1986). These quality tests were also conducted at Food Quality Testing Laboratory, Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, Coimbatore (India).

Results and discussion

Data analysis for the desiccant system experimentation

Main effects plot for S/N ratio for optimization phase indicated that volumetric purge to feed ratio parameter at second level (1.2) along with space velocity at first level (17 m3/h/kgdes) performs better in achieving lowest moisture content product air by the developed PSA system.

ANOVA for steady state moisture content for optimization phase is shown in Table 2. The results concluded that the parameter volumetric purge flow to feed flow ratio dominates the system response the most and with 60.28% contribution and the parameter space velocity dominates the system response with 27.37% contribution. The value of regression coefficient for optimization phase is R2 = 93.48% which shows a high significance of the model since most of the total variations are explained by the model.

Table 2.

ANOVA for steady state moisture content for optimization phase

| Source | DF | Seq SS | Contribution | Adj SS | Adj MS | F-Value | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 4 | 7.98399 | 93.48% | 7.98399 | 1.99600 | 46.60 | 0.000 |

| Linear | 2 | 7.48584 | 87.65% | 7.48896 | 3.74448 | 87.42 | 0.000 |

| A | 1 | 5.14798 | 60.28% | 5.20240 | 5.20240 | 121.46 | 0.000 |

| B | 1 | 2.33786 | 27.37% | 2.28656 | 2.28656 | 53.38 | 0.000 |

| Square | 1 | 0.22185 | 2.60% | 0.22185 | 0.22185 | 5.18 | 0.040 |

| B*B | 1 | 0.22185 | 2.60% | 0.22185 | 0.22185 | 5.18 | 0.040 |

| 2 way interaction | 1 | 0.27630 | 3.24% | 0.27630 | 0.27630 | 6.45 | 0.025 |

| A*B | 1 | 0.27630 | 3.24% | 0.27630 | 0.27630 | 6.45 | 0.025 |

| Error | 13 | 0.55681 | 6.52% | 0.55681 | 0.04283 | ||

| Lack-of-fit | 1 | 0.54295 | 6.36% | 0.54295 | 0.54295 | 469.87 | 0.000 |

| Pure Error | 12 | 0.01387 | 0.16% | 0.01387 | 0.00116 | ||

| Total | 17 | 8.54081 | 100.00% | ||||

| Model summary: S = 0.206959, R2 = 93.48%, R2 (adj) = 91.47% | |||||||

The correlation between the dehumidified air moisture content and operating parameters of the system is given by the developed uncoded units’ regression Eq. (8).

| 8 |

Verification phase

The improvement in quality characteristics of the PSA system at optimum levels of parameters has been predicted by conducting confirmation experiment. It is concluded that the logarithmic value of predicted and confirmation experimental steady state moisture content value (in log(ppmv)) of product air produced by the PSA system is 0.6237 and 0.6024 respectively. The result shows that percentage of error between the predicted values with the experimental one is 3.42%. It confirms the closeness of the developed model.

For optimal conditions, the solid desiccant-based dehumidifier is able to deliver 0.2m3/min dry air at 37 °C DBT and 0.1% rh to the drying chamber. Therefore, it can be used for applications that require ultra-low dew point dry air. The developed regression equation forms the basis for the design of dehumidifier for variety of parametric conditions.

Dehumidifier operation

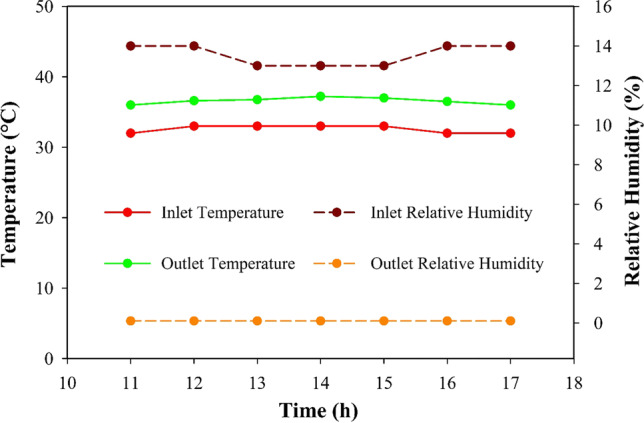

The temperature and relative humidity of the dehumidifier outlet air is the important parameters influencing the drying operation as well as the quality of the dried products. Figure 2 shows the temperature and relative humidity of dehumidifier inlet and outlet during the period of operation. After cooler of a compressor unit always supplies the compressed air at approximately equal to ambient temperature and low relative humidity. The outlet of after cooler is supplied to dehumidifier for the removal of moisture from the air. The dehumidifier inlet temperature of air was approximately 33 °C and the outlet air temperature was around 36 °C to 37 °C. There is a slight increase in temperature (3 to 4 °C) was observed due to exothermic reaction of the adsorber during adsorption. The relative humidity of the dehumidifier inlet was observed as 14% and the outlet air relative humidity was 0.1%. This very low relative humidity was achieved due to the reason that the molecular sieve 13X desiccant material filled in the adsorber has more affinity to the moisture content, therefore almost the entire moisture content has been adsorbed till it gets saturated. Results indicated that the dehumidifier unit always delivers air at ultralow relative humidity.

Fig. 2.

Temperature and relative humidity of dehumidifier inlet and outlet air

Drying characteristics of mint leaves

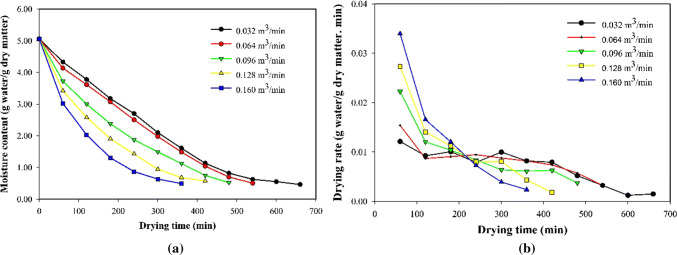

The solid desiccant-based air dehumidifier system operating parameters were optimized to produce continuous dehumidified air having pressure dew point temperature of −40 °C, which is the most suitable for the drying of agricultural products (ISO 8573-1 Purity class (1.2.1 and 2.2.2)). The dry bulb temperature of the outlet air from the solid desiccant-based dehumidifier was found in the range 35 °C to 37 °C having relative humidity of 0.1%. The effect of volume flow rate of the dehumidified air on the mint leaves drying was studied for the flow rates 0.032 m3/min, 0.064 m3/min, 0.096 m3/min, 0.128 m3/min and 0.160 m3/min. Variations of moisture content of the mint leaves in dry basis are shown in Fig. 3a. for the different flow rates of dehumidified air. The initial moisture content (dry basis) 5.059 g water/g dry matter was reduced to less than 0.5 g water/g dry matter in 660, 540, 450, 390 and 360 min respectively for 0.032, 0.064, 0.096, 0.128 and 0.160 m3/min. Further, increment in the volume flow rate of the dehumidified air did not show any appreciable reduction in drying time. Drying curves of mint leaves depicted that the drying process has only falling rate period, it means the constant drying period is absent. Similar kind of results were also reported for most of the agricultural products including mint leaves. The drying time of mint leaves in solid desiccant-based drying is compared with the other type of dryers that is having approximately equal temperature range of 30 °C to 40 °C: Open sun drying – 360 min. (Akpinar 2006) and heat pump drying – 270 to 360 min. (Aktas et al. 2017). In the present study the drying time was observed as 360 min. at the volume flow rate of 0.160 m3/min.

Fig. 3.

Effect of volume flow rate on misture content and drying rate

The effect of volume flow rate on the drying rate of the mint leaves is shown in Fig. 3b. Variations of drying rate with the drying time indicates that the drying rate is maximum at the initial period of drying due to the evaporation of free surface moisture on the leaves. Moreover, the area of mint leaves exposed to the dehumidified air is more due to their favorable flat shape, which plays a vital role in moisture transport to the surrounding air. The drying rate is maximum at the beginning due to the high moisture content on the leaves, clearly seen on Fig. 3b. The drying rate decreases with increase in drying time due to reduction in the available free moisture at the surface.

The effect of volume flow rate on the effective moisture diffusivity values of mint leaves drying was analyzed. Usually, the effective moisture diffusivity value increases with increase in drying air temperature but in this present study the air temperature was maintained approximately constant and only the volume flow rate was varied. The effective moisture diffusivity values for mint leaves drying found in the literature are 3.982 × 10–11 to 2.073 × 10–10 m2/s for microwave drying process (Özbek and Dadali 2007), 7.04 × 10–12 m2/s for open sun drying (Akpinar 2006), 6.935 × 10–11 for solar drying and 3.5 × 10–11 to 4.79 × 10–11 m2/s for heat pump drying (Aktas et al. 2017). In the present study, the effective moisture diffusivity of mint leaves was increased with increase in volume flow rate of air because the increase in volume flow rate decreases the drying time. The minimum and maximum effective moisture diffusivity values are observed as 2.07534 × 10−11 m2/s to 3.45817 × 10−11 m2/s at 0.160 m3/min and 0.032 m3/min volume flow rates respectively.

Quality of dried mint leaves

In order to ensure the quality of the samples, colour measurements and chlorophyll estimation were done on the fresh and dried samples. The average colour measurements and ascorbic acid of the fresh and dried mint leaves are listed in Table 3 for various volume flow rates of air. The colour coordinates selected for the present analysis was CIE L*a*b* because this is the most commonly recommended colour measurements for the fruits and vegetables (Alwazeer and Ors 2019). Normally, the change in colour is observed in agricultural products due to enzymatic/non-enzymatic reactions. There is a significant reduction in the colour values (L*, a*, b*) of the dried mint leaves while comparing with the fresh sample. The total colour change (∆E) was estimated using Eq. (7) for all the dried samples with reference to the fresh sample are indicated in Table 3. Decrease in L* was observed for all the dried samples, it indicates the darkening of the mint leaves during the drying process. Negative values of a* indicate the dried samples have retained their green colour. It is evident from the table, the mint samples dried at 0.128 m3/min and 0.160 m3/min volume flow rates exhibit the lower colour change. The colour measurements of sun dried (20.62, −2.13, 4.68) and cabinet dried (18.41, −3.02, 5.21) mint leaves reported by Kaur et al. (2008) was much lower than the present study results. It is concluded that, the desiccant based dehumidification drying system comparatively produced good quality dried samples.

Table 3.

Quality analysis of the mint samples

| Type of sample | Colour Measurement | Ascorbic acid | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L* | a* | b* | ∆E | mg/100 g | Retention % | ||

| Fresh | 33.08 ± 0.885 | −7.02 ± 0.851 | 17.78 ± 1.216 | – | 17.4 | – | |

| Dried samples | 0.032 m3/min | 22.24 ± 0.740 | −2.98 ± 0.946 | 12.34 ± 1.185 | 12.78 | 10.5 | 60.34 |

| 0.064 m3/min | 23.02 ± 0.933 | −3.04 ± 0.843 | 13.35 ± 0.923 | 11.69 | 11.1 | 63.79 | |

| 0.096 m3/min | 22.36 ± 0.999 | −3.49 ± 0.630 | 14.01 ± 1.487 | 11.89 | 11.6 | 66.67 | |

| 0.128 m3/min | 24.97 ± 1.577 | −3.12 ± 0.681 | 13.76 ± 0.950 | 9.86 | 12.1 | 69.54 | |

| 0.160 m3/min | 24.13 ± 0.965 | −3.47 ± 0.926 | 14.18 ± 1.311 | 10.28 | 12.2 | 70.11 | |

|

Fresh sample |

Dried sample |

||||||

mean ± SD (Standard Deviation)

Chlorophyll content

Chlorophyll content present in the fresh and dried mint leaves was estimated using the biochemical method. When the leaves dried a higher drying air temperature lead to degradation of chlorophyll, whereas in the present study the maximum temperature of the air was around 37 °C. The dried samples have sufficiently retained their chlorophyll content, the same has been confirmed with the color measurements listed in Table 3. The green colour in the mint leaves is caused by the chlorophyll content and magnesium. Some literatures have reported that the enzymatic reactions during the drying influence the color of the products. The chlorophyll content in the fresh mint sample was estimated as 112.45 mg/g. The dried samples chlorophyll content was observed as 88.73 mg/g, 92.41 mg/g, 96.8 mg/g, 95.86 mg/g and 96.72 mg/g for different volume flow rates 0.032 m3/min, 0.064 m3/min, 0.096 m3/min, 0.128 m3/min and 0.160 m3/min respectively. The maximum retention of the chlorophyll content was observed at 0.160 m3/min, due to the lower drying time, whereas for the least volume low rate of air the chlorophyll content was also low because the mint leaves were exposed to the dehumidified air for more than 600 min..

Ascorbic acid (Vitamin C) content

Ascorbic acid (vitamin C) is one of the important nutritional content, which helps to regulate the blood pressure and reducing the cholesterol content. The antioxidant property of vitamin C plays a significant role in improving the immune system. The main function of ascorbic acid is in collagen synthesis and consequently in the formation and maintenance of cartilage, bones, gums, skin, teeth, etc. (Kumar et al. 2015). Generally, the retention of ascorbic acid and chlorophyll content is more in low temperature drying of green leafy vegetables. From the previous literature, it is found that 15% to 31% and 37% to 49% of ascorbic acid retained in open sun-dried and cabinet dried mint samples respectively (Lakshmi and Vimala, 2000). Ascorbic acid retention is also affected by the pretreatment methods, for the blanched mint sample has retained about 34.89%, on the other hand 46.82% retained in untreated samples dried in cabinet dryer. In this present study, any pretreatment methods were adopted and also the drying air temperature was maintained less than 40 °C. The ascorbic acid content in fresh mint samples was observed as 17.4 mg/100 g and in dried samples varied from 10.5 to 12.2 mg/100 g. the maximum amount of ascorbic acid 12.2 mg/100 g (70.11%) was retained in the sample dried at 0.160 m3/min, whereas 60.34% only retained in the sample dried at 0.032 m3/min. The percentage retention of ascorbic acid was reduced due to the variation in the proportions of moisture content and the dry matter of samples. Comparison with the previous studies reported with drying methods like open sun drying, solar cabinet drying and hot air drying indicates that the solid desiccant-based drying has retained more amount of ascorbic acid (Table 3). The main reason is that the drying takes place at relatively lower temperature of air. Therefore, the solid desiccant-based dryers can be preferred to heat sensitive green leafy vegetables and herbal drying purposes.

Conclusion

A solid desiccant pressure swing adsorption dehumidification system was designed to deliver the air at approximately equal to the atmospheric air temperature with very low relative humidity. The significant operating parameters (volumetric purge to feed ratio and space velocity) were optimized through Taguchi method, to deliver the dehumidified air continuously at 0.2 m3/min with 0.1% relative humidity. The dehumidifier system was coupled with a drying chamber to investigate the drying kinetics of the mint leaves at different volume flow rates of air. The initial moisture content of 5.059 g water/g dry matter was reduced to safe storage level in 360 min. at 0.160 m3/min. The effective moisture diffusivity of the mint leaves (Mentha arvensis) was found to be varying between 2.07534 × 10−11 and 3.45817 × 10−11 m2/s. The quality analysis of the dried samples: change of colour, retention of chlorophyll content and ascorbic acid indicated that the solid desiccant-based dryers are the most suitable method for drying leafy vegetables and medicinal herbs.

List of symbols

- Adj SS

Adjusted sum of squares

- m3/min

Cubic metre per minute

- °C

Degree celsius

- Deff

Effective moisture diffusivity (m2/s)

- DBT

Dry bulb temperature

- DR

Drying rate (g water/g dry matter.min)

- g

Gram

- hp

Horse power

- kg

Kilogram

- lpm

Litre per minute

- m/s

Meter per second

- m

Metre

- md

Moisture content on dry basis (g water/g dry matter)

- mt

Moisture content at any time ‘t’

- MR

Moisture ratio

- ppmv

Parts per million volume basis

- %

Percent

- R1

Replication 1

- R2

Replication 2

- R3

Replication 3

- R2

Regression

- rh

Relative humidity

- s

Second

- t

Drying time (sec)

- wo

Initial weight of the product (g)

- wd

Weight of the dry matter (g)

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abasi S, Minaei S, Khoshtaghaza MH. Effect of desiccant system on thin layer drying kinetics of corn. J Food Sci Technol. 2017;54(13):4397–4404. doi: 10.1007/s13197-017-2914-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akpinar EK. Drying of mint leaves in a solar dryer and under open sun: modelling, performance analyses. Energy Convers Manage. 2010;51(12):2407–2418. doi: 10.1016/j.enconman.2010.05.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alwazeer D, Örs B. Reducing atmosphere drying as a novel drying technique for preserving the sensorial and nutritional notes of foods. J Food Sci Technol. 2019;56(8):3790–3800. doi: 10.1007/s13197-019-03850-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arulraj M, Palani PK, Venkatesh L. Optimization of process parameters in stir casting of hybrid metal matrix (LM25/SiC/B4C) composite using taguchi method. J Adv Chem. 2017;13(9):6475–6479. doi: 10.24297/jac.v13i9.5777. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arulraj M, Palani PK. Parametric optimization for improving impact strength of squeeze cast of hybrid metal matrix (LM24–SiC p–coconut shell ash) composite. J Braz Soc Mech Sci Eng. 2018;40(1):2. doi: 10.1007/s40430-017-0925-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Djaeni M, van Boxtel AJB. PhD Thesis summary: energy efficient multistage zeolite drying for heat-sensitive products. Dry Technol. 2009;27(5):721–722. doi: 10.1080/07373930902828203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sebaii AA, Shalaby SM. Experimental investigation of an indirect-mode forced convection solar dryer for drying thymus and mint. Energy Convers Manag. 2013;74:109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.enconman.2013.05.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gurtas Seyhan F, Evranuz Ö. Low temperature mushroom (A. bisporus) drying with desiccant dehumidifiers. Drying Technol. 2000;18(1–2):433–445. doi: 10.1080/07373930008917714. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gichau AW, Okoth JK, Makokha A. Moisture sorption isotherm and shelf life prediction of complementary food based on amaranth–sorghum grains. J Food Sci Technol. 2020;57(3):962–970. doi: 10.1007/s13197-019-04129-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanif S, Sultan M, Miyazaki T, Koyama S. Investigation of energy-efficient solid desiccant system for wheat drying. Int J Agric Biol Eng. 2019;12(1):221–228. [Google Scholar]

- Hodali R, Bougard J. Integration of a desiccant unit in crops solar drying installation: optimization by numerical simulation. Energy Convers Manag. 2001;42(13):1543–1558. doi: 10.1016/S0196-8904(00)00159-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kannan S, Arjunan T. Optimization of process parameters of adsorption process in solid desiccant dehumidification system using genetic algorithm. J Chin Soc Mech Eng. 2019;40(4):437–443. [Google Scholar]

- Kannan VS, Arjunan TV, Vijayan S (2020) Experimental investigation of temperature swing adsorption system for air dehumidification. Heat Mass Transf: 1–13

- Kaur A, Kaur D, Oberoi DPS, Gill BS, Sogi DS. Effect of dehydration on physicochemical properties of mustard, mint and spinach. J Food Process Preserv. 2008;32(1):103–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4549.2007.00168.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kesavan S, Arjunan TV, Vijayan S. Thermodynamic analysis of a triple-pass solar dryer for drying potato slices. J Thermal Anal Calorim. 2019;136(1):159–171. doi: 10.1007/s10973-018-7747-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar SS, Manoj P, Shetty NP, Giridhar P. Effect of different drying methods on chlorophyll, ascorbic acid and antioxidant compounds retention of leaves of Hibiscus sabdariffa L. J Sci Food Agric. 2015;95(9):1812–1820. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.6879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakshmi B, Vimala V. Nutritive value of dehydrated green leafy vegetable powders. J Food Sci Technol. 2000;37(5):465–471. [Google Scholar]

- Misha S, Mat S, Ruslan MH, Salleh E, Sopian K. Performance of a solar-assisted solid desiccant dryer for oil palm fronds drying. Sol Energy. 2016;132:415–429. doi: 10.1016/j.solener.2016.03.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthukumar A, Venkatesh A. Biological inductions of systemic resistance to collar rot of peppermint caused by Sclerotium rolfsii. Acta Physiol Plant. 2014;36(6):1421–1431. doi: 10.1007/s11738-014-1520-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Özbek B, Dadali G. Thin-layer drying characteristics and modelling of mint leaves undergoing microwave treatment. J Food Eng. 2007;83(4):541–549. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2007.04.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandra CT, Rao PS. Shelf-life and colour change kinetics of Aloe vera gel powder under accelerated storage in three different packaging materials. J Food Sci Technol. 2013;50(4):747–754. doi: 10.1007/s13197-011-0398-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganna S. Handbook of analysis and quality control for fruit and vegetable products. New York: Tata McGraw-Hill Education; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Sallam YI, Aly MH, Nassar AF, Mohamed EA. Solar drying of whole mint plant under natural and forced convection. J Adv Res. 2015;6(2):171–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seshachalam K, Thottipalayam VA, Selvaraj V. Drying of carrot slices in a triple pass solar dryer. Thermal Sci. 2017;21(suppl. 2):389–398. doi: 10.2298/TSCI17S2389S. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sowrirajan M, Mathews PK, Vijayan S (2017) Investigation and optimization of process variables on clad angle in 316L stainless steel cladding using genetic algorithm. In: High temperature material processes: an international quarterly of high-technology plasma processes, vol 21, no. 2. ASTFE, pp 109–125. 10.1615/HighTempMatProc.2017021841

- Sugar VR, Suresh KP. Recent advances in drying and dehydration of fruits and vegetables: a review. J Food Sci Technol. 2010;47(1):15–20. doi: 10.1007/s13197-010-0010-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowrirajan M, Mathews PK, Vijayan S. Simultaneous multi-objective optimization of stainless-steel clad layer on pressure vessels using genetic algorithm. J Mech Sci Technol. 2018;32(6):2559–2568. doi: 10.1007/s12206-018-0513-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatachalam SK, Thottipalayam Vellingri A, Selvaraj V. Low-temperature drying characteristics of mint leaves in a continuous-dehumidified air drying system. J Food Process Eng. 2020;43(4):e13384. doi: 10.1111/jfpe.13384. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayan S, Arjunan TV, Kumar A. Mathematical modeling and performance analysis of thin layer drying of bitter gourd in sensible storage based indirect solar dryer. Innov Food Sci Emerg Technol. 2016;36:59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ifset.2016.05.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayan S, Thottipalayam VA, Kumar A. Thin layer drying characteristics of curry leaves (Murraya koenigii) in an indirect solar dryer. Therm Sci. 2017;21(suppl. 2):359–367.h. doi: 10.2298/TSCI17S2359V. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayan S, Arjunan TV, Kumar A. Solar drying technology. Singapore: Springer; 2017. Fundamental concepts of drying; pp. 3–38. [Google Scholar]

- Vijayan S, Arjunan TV, Kumar A. Exergo-environmental analysis of an indirect forced convection solar dryer for drying bitter gourd slices. Renew Energy. 2020;146:2210–2223. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2019.08.066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]