Abstract

Background

Point‐of‐care lung ultrasound (LUS) is an effective tool to diagnose left‐sided congestive heart failure (L‐CHF) in dogs via detection of ultrasound artifacts (B‐lines) caused by increased lung water.

Hypothesis/Objectives

To determine whether LUS can be used to monitor resolution of cardiogenic pulmonary edema in dogs, and to compare LUS to other indicators of L‐CHF control.

Animals

Twenty‐five client‐owned dogs hospitalized for treatment of first‐onset L‐CHF.

Methods

Protocolized LUS, thoracic radiographs (TXR), and plasma N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide were performed at hospital admission, hospital discharge, and recheck examinations. Lung ultrasound findings were compared between timepoints and to other clinical measures of L‐CHF.

Results

From time of hospital admission to discharge (mean 19.6 hours), median number of LUS sites strongly positive for B‐lines (>3 B‐lines per site) decreased from 5 (range, 1‐8) to 1 (range, 0‐5; P < .001), and median total B‐line score decreased from 37 (range, 6‐74) to 5 (range, 0‐32; P = .002). Lung ultrasound indices remained improved at first recheck (P < .001). Number of strong positive sites correlated positively with respiratory rate (r = 0.52, P = .008) and TXR edema score (r = 0.51, P = .009) at hospital admission. Patterns of edema resolution differed between LUS and TXR, with cranial quadrants showing more significant reduction in B‐lines compared to TXR edema score (80% vs 29% reduction, respectively; P = .003).

Conclusions and Clinical Importance

Lung ultrasound could be a useful tool for monitoring resolution of pulmonary edema in dogs with L‐CHF.

Keywords: B‐lines, canine, lung rockets, point‐of‐care, pulmonary edema

Abbreviations

- DCM

dilated cardiomyopathy

- HR

hazard ratio

- L‐CHF

left‐sided congestive heart failure

- LA

left atrium

- LA : Ao

ratio of left atrial to aortic diameter

- LUS

lung ultrasound

- MMVD

myxomatous mitral valve disease

- NT‐proBNP

N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide

- OR

odds ratio

- TP

timepoints

- TXR

thoracic radiographs

1. INTRODUCTION

Left‐sided congestive heart failure (L‐CHF) in dogs typically manifests as pulmonary edema from increased hydrostatic pressure within the left atrium (LA) and pulmonary vasculature. Traditionally, assessment of L‐CHF in dogs relies on thoracic radiographs (TXR) to identify pulmonary edema in dogs with compatible clinical signs and physical examination findings. 1 Although commonly utilized, TXR have disadvantages for detecting and monitoring L‐CHF. First, TXR necessitate recumbent positioning and removal from an oxygen chamber, which can exacerbate hypoxemia and respiratory distress. Second, TXR can be associated with relatively frequent misinterpretation (18% rate of false positive L‐CHF diagnosis in 1 study), 2 particularly if radiographic technique is suboptimal. Furthermore, repeated TXR can lead to increased radiation exposure for animals and staff.

Point‐of‐care lung ultrasound (LUS) is an effective tool for the diagnosis of L‐CHF in humans, dogs, and cats and can differentiate between cardiogenic pulmonary edema and noncardiac causes of dyspnea or cough with high sensitivity and specificity. 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 In this setting, LUS has demonstrated a similar or greater positive predictive value than N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide (NT‐proBNP) or TXR. 4 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 Use of LUS to detect L‐CHF involves identification of ultrasound artifacts termed B‐lines. 7 B‐lines are discrete narrow‐based vertical hyperechoic artifacts extending from the lung surface to the far field without fading, and moving synchronously with respiration. 7 , 10 , 13 B‐lines are caused by the high impendence gradient of a fluid‐air interface that occurs when edema in the pulmonary interstitium and alveoli is adjacent to pulmonary air. Isolated B‐lines can occur in up to 31% of dogs with radiographically normal lungs, 14 while numerous multifocal B‐lines are reported in cardiogenic pulmonary edema, 2 , 3 , 4 , 15 pneumonia, 2 and pulmonary contusions 16 in dogs and cats.

Lung ultrasound has utility in serial monitoring of pulmonary edema in humans with L‐CHF, with B‐lines decreasing over a number of hours and resolving within days of diuretic treatment. 17 , 18 Improvement in B‐lines also correlates well with other markers of L‐CHF resolution, including TXR and NT‐proBNP. 18 Although LUS shows promise as a monitoring tool for pulmonary edema in humans, this has yet to be investigated in dogs. The primary objective of our study was to investigate the utility of LUS to monitor resolution of pulmonary edema in dogs following a diagnosis of L‐CHF. Secondary goals included: (a) to compare LUS findings to other indicators of L‐CHF resolution, including TXR, respiratory rate, and NT‐proBNP; (b) to assess patterns of edema resolution on LUS vs TXR; and (c) to evaluate the ability of LUS or other indices to predict clinical outcome, including early L‐CHF recurrence and cardiac death. We hypothesized that LUS would be diagnostically useful in monitoring clinical and radiographic resolution of L‐CHF in dogs.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at the participating institutions. Informed owner consent was obtained for each study dog.

Client‐owned dogs presented to the Small Animal Emergency and Critical Care Service or the Cardiology Service at the Iowa State University Lloyd Veterinary Medical Center and the North Carolina State Veterinary Hospital were prospectively enrolled after diagnosis of first‐onset L‐CHF. Diagnosis of L‐CHF (initial episode and subsequent recurrence, if applicable) was based on a combination of: (a) clinical signs and physical examination findings consistent with L‐CHF (increased respiratory rate or effort, with or without cough or exercise intolerance); (b) echocardiogram performed by a board‐certified cardiologist or cardiology resident confirming presence of severe myxomatous mitral valve disease (MMVD) or dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM); (c) TXR demonstrating the presence of an interstitial or alveolar pulmonary pattern consistent with cardiogenic pulmonary edema; and (d) a positive clinical response (decreased respiratory rate) with furosemide diuresis. Additional inclusion criteria included completion of the following diagnostic tests within 6 hours of hospital admission: LUS performed by a trained investigator; 3‐view TXR; and venous blood sampling for plasma NT‐proBNP. Dogs with moderate‐to‐severe pleural effusion were excluded, as pressure atelectasis could create B‐lines independent of pulmonary pathology. Dogs that had evidence of previous L‐CHF or that were receiving furosemide at time of initial presentation were excluded, as were dogs that were hospitalized for less than 6 hours.

Dogs received emergent and outpatient treatment for L‐CHF according to standard medical practices. Emergency treatments included supplemental oxygen, sedatives, furosemide IV, and pimobendan PO. Occasionally dobutamine, vasodilators (hydralazine or nitroprusside), or antiarrhythmics (digoxin, diltiazem, lidocaine, sotalol, or mexiletine) were provided. Outpatient medical treatment usually included furosemide, pimobendan, an angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor, and spironolactone PO, and occasionally included adjunctive vasodilators (amlodipine) or antiarrhythmic medications at the discretion of the attending clinician.

Clinically important timepoints (TP) were defined as initial presentation for diagnosis of L‐CHF (testing completed within 6 hours of hospital presentation; TP1); hospital discharge (testing completed within 2 hours of hospital discharge; TP2); first outpatient recheck examination after hospital discharge (TP3); and subsequent recheck examinations (TP4+). Dogs were deemed stable for hospital discharge (TP2) when they were eupneic with respiratory rate <40 breaths per minute when breathing room air. The period between recheck examinations was determined by generalized recommendations of the cardiology services of each institution and the clinical progression of the individual dog. Physical examination, ECG, LUS, TXR, NT‐proBNP, and caregiver‐completed cardiac quality‐of‐life 19 were performed at each TP. Respiratory rate was measured at the time of LUS, while other physical examination findings were documented at the time of presentation. To prioritize dog stability at TP1, pharmacologic treatment for L‐CHF was permitted before imaging or between TXR and LUS at the discretion of the clinician. Body temperature, heart rate, and the quality‐of‐life questionnaire were not recorded at TP2.

All LUS examinations were performed by cardiologists or cardiology residents trained in lung ultrasonography using compact portable ultrasound machines equipped with curvilinear probes (Iowa State University: CX50 CompactXtreme Ultrasound [model 101855], Philips Healthcare, Andover, Massachusetts; C8‐5 Transducer [part # FUS5124], Philips Healthcare, Andover, Massachusetts; North Carolina State University: Fukuda Denshi Ultrasound [model UF‐760AG, Version 02], Tokyo, Japan; Fukuda Denshi Transducer [model FUT‐CA144‐9P], Tokyo, Japan) utilizing standard settings (ultrasound frequency 5‐8 MHz; depth 4‐6 cm). 3 The same machine and settings were used for serial examinations of the same dog. The technique for small animal LUS (Vet BLUE) has been previously described. 3 , 4 , 14 , 20 Briefly, images were obtained from four standardized acoustic windows over each hemithorax with dogs standing or in sternal recumbency for a total of 8 LUS sites (right [R] vs left [L]; caudal [Cd], perihilar [Ph], middle [Md], and cranial [Cr]). Three‐second cine loops were captured and archived from each site. Each site was evaluated for the presence of B‐lines in real time by the operator. If present, the maximum number of B‐lines within an intercostal space was recorded as 0, 1, 2, 3, >3, or infinite. Infinite B‐lines were recorded if numerous coalescing B‐lines could not be individually discerned. Sites with >3 or infinite B‐lines were scored as strong positive sites based on a consensus panel for LUS in people. 3 , 4 , 7 , 15 The total B‐line score and the total number of strong positive sites were summed and recorded for each LUS examination, with >3 and infinite B‐lines per intercostal space recorded as 4 and 10 B‐lines, respectively, for the purposes of total B‐line scoring. This scoring system was adopted from previous studies in human and veterinary patients with a maximum potential total B‐line score of 80. 4 , 6 At the time of LUS, a single right parasternal 2‐dimensional short‐axis image of the heart base was obtained to assess left atrial size from the same point‐of‐care ultrasound unit, transducer, and body position (sternal or standing). A still image optimizing the LA in diastole was used to measure the ratio of the internal diameter of the left atrium to the diameter of the aorta (LA : Ao), as has been previously described. 21

Three‐view TXR were performed by the diagnostic imaging service at each institution. Post hoc analysis was performed by a single board‐certified radiologist (J. L. F.) blinded to the LUS results. A modified Murray Lung Injury Score was used to evaluate the distribution and severity of interstitial or alveolar infiltrates as previously described in dogs. 15 , 22 Briefly, the thorax from a dorsoventral view was divided via a vertical line along the spine made from the thoracic inlet through the middle of the thorax and a perpendicular line through the carina, creating 4 quadrants (left cranial [Q1], left caudal [Q2], right cranial [Q3], and right caudal [Q4]). Each quadrant was scored 0 (no infiltrates), 1 (infiltrates affecting <25% of the quadrant), 2 (25%‐50% of the quadrant affected), 3 (50%‐75% of the quadrant affected), or 4 (75%‐100% of the quadrant affected). The sum of the quadrants was recorded with a maximum potential TXR edema score of 16. For direct comparison with LUS, Q1 included LCr + LMd, Q2 included LPh + LCd, Q3 included RCr + RMd, and Q4 included RPh + RCd LUS sites.

Venous blood samples were collected at each TP and plasma was transported the same day to a reference laboratory for quantitative NT‐proBNP measurement (Cardiopet Canine proBNP test, IDEXX Laboratories, Inc, Westbrook, Maine). Lead II ECGs were performed and interpreted by cardiologists or cardiology residents; any rhythm other than sinus rhythm or sinus tachycardia was defined as an arrhythmia, including atrial fibrillation and ventricular or supraventricular ectopy.

Final outcome (date and cause of death, or date of last follow‐up if alive) was recorded for all dogs at the end of the study period. Cardiac death was defined as death or euthanasia secondary to clinical signs suggestive of L‐CHF or sudden death at home with no known alternative noncardiac cause. Early recurrence of L‐CHF was defined as relapse of L‐CHF within 90 days of TP1.

Statistical analyses were performed using 2 commercially available software packages (GraphPad Prism 8, Graphpad Software, La Jolla, California; MedCalc Version 17.6, MedCalc Software Ltd, Seoul, South Korea). Normality of data was assessed using a combination of visual inspection of histograms and D'Agostino Pearson testing. Categorical data are reported as frequencies and proportions. Quantitative data are reported as mean ± SD (normally distributed data) or median and range (non‐normally distributed data). For normally distributed continuous data, paired t test or 1‐way repeated measures analysis of variance with Tukey's correction for multiple comparisons was used to compare data between TPs or between dogs with or without early recurrence of L‐CHF. For non‐normally distributed continuous data, Wilcoxon matched‐pairs signed rank test or Friedman test with Dunn's correction for multiple comparison was used to assess differences between these groups. Chi‐square analysis was used to evaluate differences in categorical data. Correlations between variables at different TPs were performed using Spearman analysis. Patterns of resolution of pulmonary edema between lung regions were compared within and between LUS and TXR using a combination of Student's t tests, Mann‐Whitney log‐rank tests, and Chi‐square analyses. For dogs experiencing relapse of L‐CHF at TP4+ visits, variables at TP4+ were compared to TP1 variables for the same dog using parametric and nonparametric paired‐rank analyses, with each recheck visit at TP4+ being considered as a separate event. Univariate and multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed to assess continuous and categorical variables for their utility in predicting early recurrence of L‐CHF; TP1, TP2, and TP3 variables were assessed in independent models. Univariate and multivariable Cox regression analysis was performed to evaluate TP3 variables predictive for cardiac death. Variables significant in univariate regression analyses subsequently were entered into a multivariable stepwise regression analysis. Survival time between dogs that died as a result of cardiac disease versus dogs that died from other causes was compared with a log‐rank test. For all statistical tests, a value of P < .05 was considered significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Study sample

Twenty‐five client‐owned dogs met inclusion criteria, with 20 dogs enrolled at Iowa State University and 5 dogs from North Carolina State University. Sixteen dogs were males and 9 were females; 4 dogs were sexually intact (3 males and 1 female). Sixteen breeds were represented, with Doberman Pinschers (n = 4) and Maltese (n = 3) being most common. Causes of L‐CHF included MMVD in 15/25 dogs (60%) and DCM in 10 dogs. Clinical and physical examination data for the study sample at TP1 to TP3 are shown in Table 1. One dog was euthanized between TP2 and TP3 due to acute kidney injury.

TABLE 1.

Clinical data and diagnostic results at hospital presentation (TP1), hospital discharge (TP2), and first recheck examination (TP3) for dogs diagnosed with left‐sided congestive heart failure secondary to myxomatous mitral valve disease or dilated cardiomyopathy

| Results | P values | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TP1 | TP2 | TP3 | TP1 vs TP2 | TP2 vs TP3 | TP1 vs TP3 | |

| Number of dogs | 25 | 25 | 24 a | — | — | — |

| Body temperature (°F) | 101.0 ± 1.2 | — | 102.1 (99.3‐102.7) | — | — | .035* |

| Respiratory rate (breaths/min) | 69 ± 27 | 36 ± 11 | 36 ± 11 | <.001* | .73 | <.001* |

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 164 ± 27 | — | 137 ± 27 | — | — | <.001* |

| LUS total B‐line score | 39.9 ± 20.3 | 4 (0‐32) | 0 (0‐2) | .002* | .015* | <.001* |

| LUS total strong positive sites | 5.1 ± 2.04 | 1 (0‐5) | 0 (0‐1) | <.001* | .23 | <.001* |

| TXR edema score | 8.4 ± 4.25 | 3.5 ± 3 | 0 (0‐8) | .008* | .27 | <.001* |

| NT‐proBNP (pmol/mL) | 2943 (1107 to >10 000) | 1545 (397 to >10 000) | 2553 (329 to >10 000) | <.001* | .09 | .27 |

| Quality‐of‐life score | 38 ± 18 | — | 15 ± 9 | — | — | <.001* |

Note: Data are expressed as mean ± SD for normally distributed data and as median (range) for non‐normally distributed data. Significant differences (P < .05) between timepoints are denoted with an asterisk (*).

Abbreviations: LUS, lung ultrasound; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal B‐type natriuretic peptide; TXR, thoracic radiographs.

One dog was euthanized between hospital discharge and first recheck due to complications of acute kidney injury.

3.2. Lung ultrasound, TXR, and clinical variables at TP1‐3

Lung ultrasound was feasible in all dogs. Results for total B‐line score and number of strong positive sites for TP1‐3 are shown in Table 1. Median time between hospital presentation and TP1 LUS was 2.47 (range, 0.75‐5.97) hours. Median time between TP1 LUS and TP2 LUS was 19.6 (range, 6‐116) hours, approximating the duration of hospitalization for initial diagnosis and treatment of L‐CHF in this sample of dogs. At least 1 strong positive LUS site (>3 B‐lines per site) was present in all dogs at TP1. Both total B‐line score and the number of strong positive sites were decreased at TP2 compared to TP1; median percent reduction in total B‐lines between TP1 and TP2 was 87% (range, −25% to 100%), and median percent reduction in strong positive sites was 86% (range, 0%‐100%). Figure 1 demonstrates improvement in a single LUS site between TP1 and TP2 for a representative dog. The first recheck examination (TP3) occurred a median of 12 days (range, 8‐156) after hospital discharge. Lung ultrasound variables (total B‐line score and number of strong positive sites) remained lower at TP3 compared to TP1.

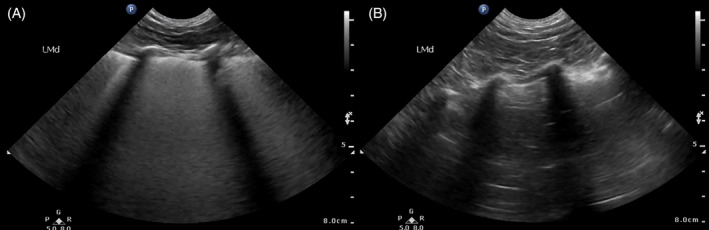

FIGURE 1.

Still B‐mode lung ultrasound (LUS) images from the left middle site of a single study dog at the time of initial diagnosis of left‐sided congestive heart failure (A) compared to hospital discharge after aggressive treatment of congestive heart failure (B). In figure (A), infinite coalescing B‐lines are seen between rib shadows within each intercostal space, while (B) demonstrates resolution of B‐lines and return of normal LUS A‐line artifacts

Thoracic radiograph results at TP1‐3 are summarized in Table 1. The median time from hospital admission to TP1 TXR was 2.23 (range, 0.5‐6) hours. Fourteen (56%) dogs had TXR completed before LUS at TP1, while the remaining 11 (44%) had LUS performed first; the median absolute time between imaging modalities at TP1 was 1.3 (range, 0.12‐3.97) hours. Nineteen (76%) dogs received at least 1 dose of parenteral furosemide prior to any imaging studies, while 6 (24%) dogs received an additional dose between imaging studies (3 of which had LUS performed first and 3 of which had TXR performed first). Compared to TP1, TXR edema score decreased at TP2 and TP3, with median reductions of 60% (range, −100% to 100%) and 100% (range, −100% to 100%), respectively. There was no difference between TXR edema scores at TP2 and TP3.

Timepoint 1‐3 comparisons for physical examination findings, plasma NT‐proBNP, and quality‐of‐life scores are included in Table 1. Significant changes in respiratory rate, body temperature, and heart rate were appreciated between TP1 and TP3. Plasma NT‐proBNP concentration was higher at TP1 compared to TP2, but did not differ between either TP2 and TP3 or TP1 and TP3. Except for 1 dog at TP3, quality‐of‐life questionnaires were completed for all dogs at TP1 and TP3. Average scores were lower for TP3 than for TP1, corresponding with improved perceived quality‐of‐life from prior to hospitalization to first recheck examination postdischarge.

3.3. Distribution and patterns of resolution of pulmonary edema between TP1‐2

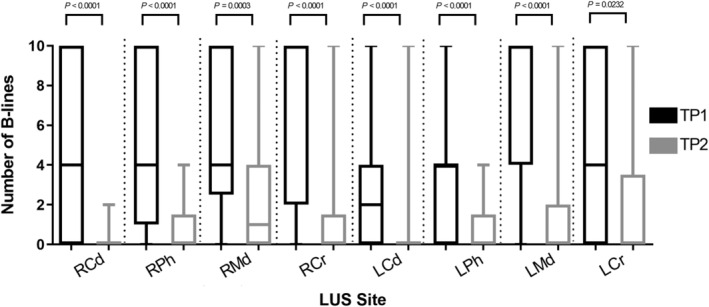

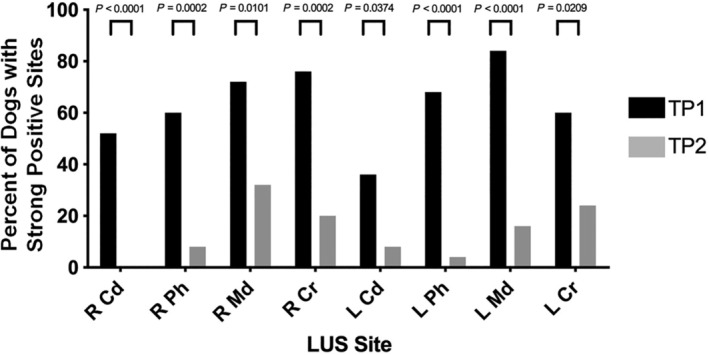

Regional distribution of edema at TP1 differed between LUS and TXR, as did the pattern of edema resolution between TP1‐2. B‐line distribution was relatively uniform across all LUS sites at both TP1 and TP2; neither the distribution of B‐lines nor the distribution of strong positive sites varied between the left and right hemithoraces at TP1 (P = .27 and P = .77, respectively) or TP2 (P = .76 and P = .84, respectively). On LUS, a reduction in number of B‐lines and strong positive sites was observed for all 8 individual LUS sites between TP1 and TP2 (see Figures 2 and 3). In contrast, at TP1, TXR results suggested more severe edema within the right lungs, with higher median pulmonary edema scores in the right quadrants (Q3 + Q4; 2.5, range 0‐4) compared to left (Q1 + Q2; 1.5, range 0‐4) (P = .02). This TXR discrepancy did not persist at TP2, with no difference in pulmonary edema distribution between right and left hemithoraces (P = .05), though a reduction in edema scores at TP2 was observed for both right (P < .001) and left (P < .001) hemithoraces compared to TP1.

FIGURE 2.

Number of B‐lines at each of 8 individual lung ultrasound (LUS) sites, compared between hospital presentation (TP1) and hospital discharge (TP2), in 25 dogs with left‐sided congestive heart failure. Median and interquartile range presented in boxplots, with whiskers indicating range. Cd, caudal; Cr, cranial; L, left; Md, middle; Ph, perihilar; R, right

FIGURE 3.

Percent of dogs with strong positive lung ultrasound (LUS) findings (>3 B‐lines) at each of 8 individual LUS sites, compared between hospital presentation (TP1) and hospital discharge (TP2), in 25 dogs with left‐sided congestive heart failure. Cd, caudal; Cr, cranial; L, left; Md, middle; Ph, perihilar; R, right

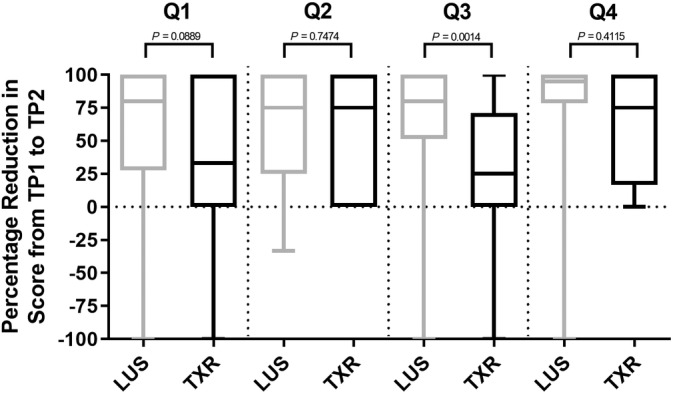

The percent change between TP1 and TP2 in total LUS B‐lines and TXR edema scores were compared between modalities for each quadrant (see Figure 4). The right cranial quadrant (Q3) differed between modalities in percent change between TPs, demonstrating an 80% reduction in B‐lines and only a 25% reduction in TXR edema score (P = .01). The left cranial quadrant (Q1) showed an 80% reduction in B‐lines and 33% TXR reduction in edema score, which was not statistically significant (P = .09). Caudal quadrants (Q2 and Q4) did not differ between LUS and TXR in terms of percent change between TP1 and TP2 (P = .75 and .41, respectively). Cranial and caudal quadrants were then grouped and analyzed together. In cranial quadrants (Q1 + Q3), B‐line score reduced more than TXR edema score (80% vs 29% reduction, respectively; P = .003), while the degree of resolution of the caudal quadrants (Q2 + Q4) was similar between LUS and TXR (93% vs 75% reduction, P = .46).

FIGURE 4.

Percent reduction in B‐lines on lung ultrasound (LUS) and edema score on thoracic radiographs (TXR) between hospital presentation (TP1) and hospital discharge (TP2) in 25 dogs with left‐sided congestive heart failure. Results are separated by anatomic quadrant. Median and interquartile range presented in boxplots, with whiskers indicating range.Note: 1 measurement each for LUS Q1, LUS Q3, and LUS Q4 are below the depicted −100% y‐axis limit. Q1, cranial quadrant; Q2, left caudal quadrant; Q3, right cranial quadrant; Q4, right caudal quadrant

3.4. Correlations between markers of L‐CHF control at TP1‐3

Both LUS indices (total B‐line score and number of strong positive sites) correlated with other markers of L‐CHF at time of initial diagnosis. Total B‐lines and strong positive sites correlated positively with respiratory rate (r = 0.54, P = .006; r = 0.52, P = .008) and TXR edema score (r = 0.46, P = .02; r = 0.51, P = .009) at TP1. Percent reduction in total B‐lines or strong positive sites from TP1‐2 or TP1‐3 did not correlate with percent reduction of any other measured clinical indices of L‐CHF control during those same periods. In contrast, percent reduction in TXR edema score from TP1‐2 correlated positively with percent reduction in respiratory rate over the same time frame (r = 0.57; P = .004), but was not correlated with percent reduction in other clinical indices of L‐CHF control. Neither plasma NT‐proBNP nor percent change in NTproBNP correlated with other L‐CHF markers at any TP.

3.5. Control vs recurrence of L‐CHF at TP4+

Recurrence of L‐CHF was diagnosed in 7 dogs at 8 of 31 total hospital visits for the entire study sample at TP4 and beyond (TP4+). Clinical variables at TP4+ were compared between visits when recurrent L‐CHF was diagnosed vs visits when L‐CHF was considered controlled. At‐home median respiratory rates measured before the visit were significantly higher for dogs found to have uncontrolled L‐CHF (36 breaths/min; range, 28‐52) compared to those with controlled L‐CHF (26 breaths/min; range, 16‐32; P = .02); although in‐hospital respiratory rates were not different between groups (P = .42). Both LUS indices detected higher measures of pulmonary edema in recurrent vs controlled L‐CHF (P < .001 for both total B‐line score and number of strong positive sites). Plasma NT‐proBNP was not different between instances of recurrent L‐CHF and controlled L‐CHF at TP4+ (P = .24).

For dogs that experienced recurrence of L‐CHF at TP4+, certain clinical variables at these TP4+ relapses differed compared to the same dog's characteristics at original TP1 presentation for L‐CHF. Compared to TP1, recurrent episodes of L‐CHF had lower total B‐line scores and number of strong positive LUS sites (P < .001 for both), lower TXR edema scores (P = .003), and lower respiratory rates (P = .03), but higher LA : Ao values (P = .034). Heart rate (P = .22), plasma NT‐proBNP (P = .22), and quality‐of‐life score (P = .19) did not differ between first‐time L‐CHF (TP1) and recurrent L‐CHF (TP4+).

3.6. Predictors of early recurrence and cardiac death

Dogs were divided into 2 groups to assess for clinical variables that could predict outcome. Group 1 consisted of dogs that had a documented recurrence of L‐CHF or cardiac death within 90 days of L‐CHF diagnosis, while group 2 consisted of dogs that survived to 90 days without experiencing L‐CHF relapse. Twenty‐three dogs were included in this analysis, excluding the dog euthanized for noncardiac disease between TP2‐3 and a dog lost to follow‐up before 90 days postdiagnosis. Group 1 consisted of 6 dogs while group 2 was comprised of the remaining 17 dogs. Clinical and imaging variables from TP1‐3 were tested for differences between groups; individual variables (with associated TP) that differed significantly between group 1 and group 2 are shown in Table 2. The only significant predictors of negative outcome at 90 days in regression analysis among TP1 variables was higher TXR edema score at TP1 (odds ratio [OR] = 1.39, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.003‐1.92; P = .05) and among TP3 variables was presence of arrhythmia (OR = 15, 95% CI = 1.14‐198, P = .04).

TABLE 2.

Clinical findings, imaging results, and other diagnostic findings that differed significantly between dogs that experienced recurrence of left‐sided congestive heart failure or cardiac death within 90 days of diagnosis (group 1) compared to those that survived to 90 days without experiencing a relapse of L‐CHF (group 2)

| Variable | Group 1 | Group 2 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of dogs | 6 | 17 | — |

| TXR edema score at TP1 | 11 (8‐16) | 7 (0‐16) | .02 |

| Arrhythmia at TP1 (n, %) | 5/6 (83%) | 4/17 (24%) | .02 |

| NT‐proBNP at TP2 (pmol/L) | 3100 (1472‐10 000) | 1441 (397‐10 000) | .034 |

| Reduction in NT‐proBNP from TP1 to TP2 (%) | 3.3% (−4.3% to 50.4%) | 59.9% (−89.1% to 87.3%) | .049 |

| Arrhythmia at TP3 (n, %) | 3/5 (60%) | 3/17 (17.6%) | .046 |

| Reduction in strong positive LUS sites from TP1 to TP3 (%) | 93.8% (57.1%‐100%) | 100% (80%‐100%) | .031 |

Note: All clinical and imaging variables at TP1‐3 were evaluated for between‐group differences; only those variables at specific TP listed in the table were significantly different between group 1 and group 2. Data are expressed as mean ± SD for normally distributed data, median (range) for non‐normally distributed data, and number (percent) for categorical data.

Abbreviations: L‐CHF, left‐sided congestive heart failure; LUS, lung ultrasound; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide; TP, timepoints; TXR, thoracic radiographs.

At time of manuscript writing, 14 of 25 dogs had died, including 10 by cardiac death and 4 by noncardiac death. Median survival time for these deceased dogs was 165 (range, 3‐759) days, and did not differ between cardiac (159 days [range, 11‐759 days]) vs noncardiac (168 days [range, 3‐210 days]) causes of death (P = .64). Median follow‐up time for dogs still alive at the end of the study was 353 (range, 12‐571) days. The only study variables that differed between dogs that experienced cardiac death (n = 10) and those that died of noncardiac causes or were alive at the end of the study (n = 15) were respiratory rate at TP1 (P = .02), TXR edema score at TP1 (P = .006), and percent reduction in respiratory rate from TP1 to TP2 (P = .03). Univariate Cox regression analysis of TP3 parameters found that the percentage reduction of strong positive sites between TP1 and TP3 (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.907, 95% CI = 0.847‐0.972, P = .006) and higher TXR edema score at TP3 (HR = 1.365, 95% CI = 1.061‐1.756, P = .02) were significant predictors of cardiac death. Only TXR edema score at TP3 remained a predictor of cardiac death on multivariable analysis (HR = 1.365, 95% CI = 1.061‐1.756, P = .02).

4. DISCUSSION

Lung ultrasound indices in dogs, including total B‐lines and the number of strong positive sites, improved from initial diagnosis of L‐CHF to hospital discharge with continued improvement at first recheck. The most significant reduction in B‐lines occurred between the first 2 TP (median 20 hours apart), when aggressive medical treatment for L‐CHF control with injectable furosemide was utilized. This LUS improvement was similar to that seen in a study of acute decompensated heart failure in 70 people, which demonstrated resolution of B‐lines after 4.2 days of medical treatment for L‐CHF. 18 Both LUS indices (total B‐line score and total number of strong positive LUS sites) performed well for the purpose of monitoring edema resolution in our study (87% and 86% reduction between TP1 and TP2, respectively), with no clear clinical advantage of tracking 1 over the other.

Median number of B‐lines (5) and strong positive sites (1) per dog at hospital discharge, though significantly improved compared to diagnosis, remained higher than reported for dogs with radiographically normal lungs. 14 In a study of 98 normal dogs, 11% of dogs were found to have B‐lines on LUS, with the vast majority having only 1 B‐line detected at a single LUS site. This difference suggests that despite being eupneic, dogs in our study likely maintained some degree of residual pulmonary edema at time of hospital discharge. By the time of first recheck examination (median 12 days later), LUS results were indistinguishable from normal dogs (median 0 B‐lines). Lung ultrasound indices then increased during relapses of L‐CHF at subsequent recheck examinations (TP4+). Overall, the results of our study suggest that B‐line artifacts improve quickly and track with TXR and clinician‐assessed clinical improvement (or relapse) of pulmonary edema in dogs with L‐CHF. In addition to being an accurate method of monitoring L‐CHF, LUS was also technically feasible at all TP and could be performed with dogs in their preferred body position through a small portal in a supplemental oxygen chamber, if needed. These results suggest that LUS could be an effective and practical tool for monitoring L‐CHF, associated with decreased radiation exposure and potentially lower cost compared to repeated TXR.

Our study also provides information about the distribution and patterns of resolution of pulmonary edema in dogs assessed by LUS compared to TXR. Spatial distribution of pulmonary edema at diagnosis (TP1) differed between LUS and TXR; LUS typically detected diffuse and symmetric edema with B‐lines in all sites, while TXR edema was more severe within the right lungs. These results are consistent with previous reports 3 , 15 suggesting that in dogs with L‐CHF, LUS typically detects B‐lines diffusely (all quadrants within each hemithorax) and is more likely to detect edema in the cranial lung regions compared to TXR. As with LUS, TXR edema scores improved from initial L‐CHF diagnosis to hospital discharge in our study, with a median 60% reduction between TP1 and TP2. The discrepancy between 60% reduction in TXR‐detected edema and 86% reduction in LUS‐detected edema might reflect mathematical differences in the scoring systems utilized for each imaging modality, or could be due to differences in the ability of LUS vs TXR to detect edema located peripherally vs centrally within a lung lobe. It is impossible to assess relative accuracy of these imaging modalities without more invasive tests (such as extravascular lung water) for comparison. 23 , 24 Patterns of edema resolution between diagnosis and hospital discharge for dogs with L‐CHF have not been previously published, and also differed between imaging modalities in our study. Results showed uniform resolution of edema from TP1 to TP2 detected by LUS for each quadrant (between 75% and 95% reduction) and for cranial (80%) vs caudal (93%) quadrants when grouped. In comparison, the cranial edema detected by TXR reduced from TP1 to TP2 by only 29%, while edema in caudal quadrants reduced to a similar degree as LUS‐detected edema (75%). This discrepancy might suggest that LUS is superior to TXR at detecting presence or absence of edema within the cranial and middle lung quadrants, compared to perihilar and caudal quadrants where both modalities identified edema similarly with similar resolution patterns.

Improvement in LUS indices and TXR‐assessed edema tracked with improvement of in‐hospital respiratory rates between hospital presentation and discharge in our study. The correlation between respiratory rate and LUS indices was not statistically significant, likely because number of B‐lines and strong positive sites decreased in a nearly “all‐or‐none” categorical fashion compared to a more measured decrease in respiratory rate. Owner‐monitored respiratory rate at home was higher for recheck examinations when dogs were experiencing a relapse of L‐CHF compared to visits when L‐CHF was controlled. These results are consistent with a previous canine study that found decreases in respiratory rate between time of L‐CHF diagnosis and recheck examination 5 to 14 days later 25 and suggested that owner‐assessed at‐home respiratory rates were the best indicator of L‐CHF control. Interestingly, in our study, in‐hospital respiratory rate at recheck examinations (TP4+) did not differ based on whether L‐CHF was controlled. These data suggest that respiratory rates measured at home are more accurate indicators of recurrent cardiogenic pulmonary edema compared to respiratory rates measured in hospital. Similar findings have been reported in previous studies, 25 , 26 , 27 likely due to clinic‐associated anxiety causing mild elevation in respiratory rates in dogs without active L‐CHF. In‐hospital respiratory rates (along with LUS and TXR imaging markers of L‐CHF) were significantly lower during recurrence of pulmonary edema at TP4+ compared to initial diagnosis of L‐CHF, likely as a result of either ongoing outpatient medical treatment buffering the severity of recurrent pulmonary edema, or improved owner education allowing identification of more subtle changes in respiratory pattern.

Plasma NT‐proBNP concentrations decreased between presentation and discharge from the hospital (median 19.6 hours); however, NT‐proBNP concentrations at the first recheck examination (median 12 days) had increased to levels similar to initial diagnosis. This finding differed from a previous study of canine L‐CHF that found decreases in NT‐proBNP between time of L‐CHF diagnosis and recheck examination 5 to 14 days later. 25 This might reflect progressive cardiac wall stress between hospital discharge and first recheck associated with diuretic de‐escalation from inpatient parenteral dosing to outpatient oral furosemide. Furthermore, NT‐proBNP at subsequent rechecks (TP4+) did not differ based on presence or absence of recurrent pulmonary edema. Potential explanations include wide intraindividual variability and breed differences in circulating NT‐proBNP concentrations, or progressive reduction in glomerular filtration rate over time leading to reduced NTproBNP clearance. 28 , 29 , 30 Overall, these findings suggest that NT‐proBNP might not be an as effective for assessment of clinical L‐CHF control (absence of pulmonary edema) compared to TXR or LUS.

Lung ultrasound indices, along with other clinical and diagnostic markers of L‐CHF at TP1‐3, were evaluated as potential predictors of early recurrence of pulmonary edema. A semi‐arbitrary cutoff of 90 days was established to define early recurrence of L‐CHF for this purpose based on the typically recommended recheck schedule for dogs diagnosed with L‐CHF at the study institutions (every 90‐120 days). Among LUS variables analyzed, only the percent reduction in strong positive sites between L‐CHF diagnosis (TP1) and first recheck (TP3) differed between dogs with or without early L‐CHF recurrence, and this variable did not remain predictive of L‐CHF relapse in regression analysis. Plasma NT‐proBNP at hospital discharge was also higher in dogs who experienced early cardiac death or recurrence of heart failure, though similarly was not significant in univariate regression. Only TXR edema scores at TP1 and arrhythmia presence at TP3 were significant predictors of early L‐CHF relapse in univariate analysis. The association between negative outcome and arrhythmias at TP3 is unsurprising, since arrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation 31 , 32 and ventricular ectopy 33 are known negative prognostic indicators in canine heart disease. The association between TXR edema score, but not LUS variables, at initial presentation with subsequent L‐CHF relapse was interesting. This disparity might have occurred because dogs with only mild to moderate pulmonary edema on TXR usually had infinite B‐lines on LUS; therefore, dogs were more likely to achieve the maximum possible quantitative scores on LUS compared to TXR. Assuming that severity of an initial L‐CHF episode is indeed predictive of recurrence of L‐CHF, these findings could suggest that compared to TXR, LUS might be more sensitive for detection of pulmonary edema but less able to discriminate severity of L‐CHF. The small number of dogs that developed early recurrence of L‐CHF in our study, and the dichotomy of selecting a single timeframe after diagnosis to define early L‐CHF recurrence, might have limited our ability to recognize trends in this sample of dogs.

There are several limitations of our study, including the small number of dogs experiencing relapse of L‐CHF or cardiac death during the study period. Lung ultrasound was performed and interpreted in real time by multiple different cardiologists and cardiology residents with previous training in LUS. Results might have been different with inexperienced operators or if images were interpreted offline by a single observer, although previous studies have demonstrated excellent interobserver agreement for detection of B‐lines between trained novice and expert individuals. 3 Operators were not systematically blinded to TXR findings, which could have introduced bias in B‐line scores. The study sample included dogs with 2 acquired cardiac diseases with different anticipated prognoses, 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 which might limit the importance of the results of our survival analyses. Despite setting time constraints in our inclusion criteria, there remained variation in timing between imaging studies at TP1 (6‐hour window) and TP2 (2‐hour window), along with differences in the amount and timing of diuretic treatment in proximity to these studies. This variability could feasibly have affected our results; in particular, diuretic treatment administered between TXR and LUS at TP1 could affect correlation between modalities. Additionally, certain TP were clinician‐dependent and somewhat owner‐ and schedule‐dependent. For example, the time of hospital discharge (TP2) was sometimes later than medically necessary due to the client's or cardiology service's schedule, and increased time for diuresis could affect imaging results at that TP. Finally, while concurrent LUS and TXR performed similarly in monitoring resolution and recurrence of L‐CHF in this sample of dogs, further study is required to determine if the clinical utility of LUS would persist in the absence of TXR.

In our study, LUS showed potential utility for monitoring resolution and recurrence of L‐CHF in dogs, tracking well with respiratory rate and radiographic edema scores and outperforming NT‐proBNP. Lung ultrasound could be considered as a practical alternative to repeated TXR for monitoring of L‐CHF in dogs.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DECLARATION

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

OFF‐LABEL ANTIMICROBIAL DECLARATION

Authors declare no off‐label use of antimicrobials.

INSTITUTIONAL ANIMAL CARE AND USE COMMITTEE (IACUC) APPROVAL DECLARATION

All procedures were approved by the IACUC of both Iowa State University and North Carolina State University. Informed owner consent was obtained for each patient enrolled.

HUMAN ETHICS APPROVAL DECLARATION

Authors declare human ethics approval was not needed for this study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Funding for this study was provided by the Iowa State University College of Veterinary Medicine Seed Grant. The authors thank Lori Moran and Allison Klein for assistance with data collection.

Murphy SD, Ward JL, Viall AK, et al. Utility of point‐of‐care lung ultrasound for monitoring cardiogenic pulmonary edema in dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2021;35:68–77. 10.1111/jvim.15990

Funding information Iowa State University College of Veterinary Medicine Seed Grant, Grant/Award Number: n/a

REFERENCES

- 1. Keene BW, Atkins CE, Bonagura JD, et al. ACVIM consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of myxomatous mitral valve disease in dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2019;33:1127‐1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ward JL, Lisciandro GR, Ware WA, et al. Lung ultrasonography findings in dogs with various underlying causes of cough. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2019;255:574‐583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ward JL, Lisciandro GR, Keene BW, et al. Accuracy of point‐of‐care lung ultrasonography for the diagnosis of cardiogenic pulmonary edema in dogs and cats with acute dyspnea. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2017;250:666‐675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ward JL, Lisciandro GR, Ware WA, et al. Evaluation of point‐of‐care thoracic ultrasound and NT‐proBNP for the diagnosis of congestive heart failure in cats with respiratory distress. J Vet Intern Med. 2019;32:1530‐1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vitturi N, Soattin M, Allemand E, et al. Thoracic ultrasonography: a new method for the work‐up of patients with dyspnea. J Ultrasound. 2011;14:147‐151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gargani L. Lung ultrasound: a new tool for the cardiologist. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2011;9:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Volpicelli G, Elbarbary M, Blaivas M, et al. International evidence‐based recommendations for point‐of‐care lung ultrasound. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38:577‐591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gargani L, Frassi F, Soldati G, et al. Ultrasound lung comets for the differential diagnosis of acute cardiogenic dyspnoea: a comparison with natriuretic peptides. Eur J Heart Fail. 2008;10:70‐77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Manson WC, Bonz JW, Carmody K, et al. Identification of sonographic B‐lines with linear transducer predicts elevated B‐type natriuretic peptide level. West J Emerg Med. 2011;12:102‐106. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Prosen G, Klemen P, Strnad M, Grmec Š. Combination of lung ultrasound (a comet‐tail sign) and N‐terminal pro‐brain natriuretic peptide in differentiating acute heart failure from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma as cause of acute dyspnea in prehospital emergency setting. Crit Care. 2011;15:R114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Liteplo AS, Marill KA, Villen T, et al. Emergency thoracic ultrasound in the differentiation of the etiology of shortness of breath (ETUDES): sonographic B‐lines and N‐terminal Pro‐brain‐type natriuretic peptide in diagnosing congestive heart failure. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:201‐210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Peris A, Tutino L, Zagli G, et al. The use of point‐of‐care bedside lung ultrasound significantly reduces the number of radiographs and computed tomography scans in critically ill patients. Anesth Analg. 2010;111:687‐692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lichtenstein D, Meziere G, Biderman P, et al. The comet‐tail artifact: an ultrasound sign of alveolar‐interstitial syndrome. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 1997;156:1640‐1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lisciandro GR, Fosgate GT, Fulton RM. Frequency and number of ultrasound lung rockets (B‐lines) using a regionally based lung ultrasound examination named Vet BLUE (Veterinary Bedside Lung Ultrasound Exam) in dogs with radiographically normal lung findings. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2014;55:315‐322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ward JL, Lisciandro GR, DeFrancesco TC. Distribution of alveolar‐interstitial syndrome in dogs and cats with respiratory distress as assessed by lung ultrasound versus thoracic radiographs. J Vet Emerg Crit Care. 2018;28:415‐428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Armenise A, Boysen RS, Rudloff E, et al. Veterinary focused assessment with sonography for trauma ‐ airway, breathing, circulation, disability and exposure: a prospective observational study in 64 canine trauma patients. J Small Anim Pract. 2018;60:173‐182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liteplo AS, Murray AF, Kimberly HH, Noble VE. Real‐time resolution of sonographic B‐lines in a patient with pulmonary edema on continuous positive airway pressure. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28:5‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Volpicelli G, Caramello V, Cardinale L, et al. Bedside ultrasound of the lung for the monitoring of acute decompensated heart failure. Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26:585‐591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Freeman LM, Rush JE, Farabaugh AE, Must A. Development and evaluation of a questionnaire for assessing health‐related quality of life in dogs with cardiac disease. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2005;226:1864‐1868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lichtenstein DA, Mezière GA. Relevance of lung ultrasound in the diagnosis of acute respiratory failure ‐ the BLUE protocol. Chest. 2008;134:117‐125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rishniw M, Erb HN. Evaluation of four 2‐dimensional echocardiographic methods of assessing left atrial size in dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2000;14:429‐435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kellihan HB, Waller KR, Pinkos A, et al. Acute resolution of pulmonary alveolar infiltrates in 10 dogs with pulmonary hypertension treated with sildenafil citrate: 2005–2014. J Vet Cardiol. 2015;17:182‐191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Agricola E, Bove T, Oppizzi M, et al. Ultrasound comet‐tail images: a marker of pulmonary edema ‐ a comparative study with wedge pressure and extravascular lung water. Chest. 2005;127:1690‐1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Enghard P, Rademacher S, Nee J, et al. Simplified lung ultrasound protocol shows excellent prediction of extravascular lung water in ventilated intensive care patients. Crit Care. 2015;19:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schober KE, Hart TM, Stern JA, et al. Effects of treatment on respiratory rate, serum natriuretic peptide concentration, and Doppler echocardiographic indices of left ventricular filling pressure in dogs with congestive heart failure secondary to degenerative mitral valve disease and dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2011;239:468‐479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Schober KE, Hart TM, Stern JA, et al. Detection of congestive heart failure in dogs by Doppler echocardiography. J Vet Intern Med. 2010;24:1358‐1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Boswood A, Gordon SG, Häggström J, et al. Temporal changes in clinical and radiographic variables in dogs with preclinical myxomatous mitral valve disease: the EPIC study. J Vet Intern Med. 2020;34:1108‐1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Merveille A, Wiberg M, Gouni V, et al. Breed differences in natriuretic peptides in healthy dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2014;28:451‐457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kellihan HB, Oyama MA, Reynolds CA, Stepien RL. Weekly variability of plasma and serum NT‐proBNP measurements in normal dogs. J Vet Cardiol. 2009;11:S93‐S97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bruins S, Fokkema MR, Römer JWP, et al. High intraindividual variation of B‐type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and amino‐terminal proBNP in patients with stable chronic heart failure. Clin Chem. 2004;50:2052‐2058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jung SW, Sun W, Griffiths LG, Kittleson MD. Atrial fibrillation as a prognostic indicator in medium to large‐sized dogs with myxomatous mitral valvular degeneration and congestive heart failure. J Vet Intern Med. 2016;30:51‐57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Calvert CA, Pickus CW, Jacobs GJ, Brown J. Signalment, survival, and prognostic factors in Doberman pinschers with end‐stage cardiomyopathy. J Vet Intern Med. 1997;11:323‐326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Martin MWS, Stafford Johnson MJ, Strehlau G, King JN. Canine dilated cardiomyopathy: a retrospective study of prognostic findings in 367 clinical cases. J Small Anim Pract. 2010;51:428‐436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Borgarelli M, Crosara S, Lamb K, et al. Survival characteristics and prognostic variables of dogs with preclinical chronic degenerative mitral valve disease attributable to myxomatous degeneration. J Vet Intern Med. 2012;26:69‐75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Borgarelli M, Savarino P, Crosara S, et al. Survival characteristics and prognostic variables of dogs with mitral regurgitation attributable to myxomatous valve disease. J Vet Intern Med. 2008;22:120‐128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Borgarelli M, Santilli RA, Chiavegato D, et al. Prognostic indicators for dogs with dilated cardiomyopathy. J Vet Intern Med. 2006;20:104‐110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Baron Toaldo M, Romito G, Guglielmini C, et al. Prognostic value of echocardiographic indices of left atrial morphology and function in dogs with myxomatous mitral valve disease. J Vet Intern Med. 2018;32:914‐921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. López‐Alvarez J, Elliott J, Pfeiffer D, et al. Clinical severity score system in dogs with degenerative mitral valve disease. J Vet Intern Med. 2015;29:575‐581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]