Abstract

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a hematopoietic malignancy characterized by the clonal proliferation of antibody-secreting plasma cells. Bortezomib (BZM), the first FDA-approved proteasome inhibitor, has significant antimyeloma activity and prolongs the median survival of MM patients. However, MM remains incurable predominantly due to acquired drug resistance and disease relapse. β-Catenin, a key effector protein in the canonical Wnt signaling pathway, has been implicated in regulating myeloma cell sensitivity to BZM. Decitabine (DAC) is an epigenetic modulating agent that induces tumor suppressor gene reexpression based on its gene-specific DNA hypomethylation. DAC has been implicated in modulating Wnt/β-catenin signaling by promoting the demethylation of the Wnt/β-catenin antagonists sFRP and DKK. In this study, we report the effects of single reagent DAC therapy and DAC combined with BZM on β-catenin accumulation, myeloma cell survival, apoptosis, and treatment sensitivity. Our study proved that DAC demethylated and induced the reexpression of the Wnt antagonists sFRP3 and DKK1. DAC also reduced GSK3β (Ser9) phosphorylation and decreased β-catenin accumulation in the nucleus, which were induced by BZM. Thus, the transcription of cyclin D1, c-Myc, and LEF/TCF was reduced, which synergistically inhibited cell proliferation, enhanced BZM-induced apoptosis, and promoted BZM-induced cell cycle arrest in myeloma cells. In summary, these results indicated that DAC could synergistically enhance myeloma cell sensitivity to BZM at least partly by regulating Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Our results can be used to optimize therapeutic regimens for MM.

Key words: Multiple myeloma (MM), Bortezomib, Decitabine, Wnt/β-catenin pathway, Demethylation

INTRODUCTION

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a neoplastic disorder characterized by the clonal proliferation of antibody-secreting plasma cells in the bone marrow; these factors cause pathological bone fracture, anemia, renal dysfunction, and hypercalcemia1. With the significant advances in understanding the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway, through which intracellular proteins are degraded, the treatment paradigm for myeloma has recently changed. Bortezomib (BZM), the first FDA-approved proteasome inhibitor, has significantly improved the response rates and prolonged the median survival of MM patients from 2 years to more than 5 years2–4. However, MM remains incurable predominantly due to drug insensitivity and resistance. The mechanism of BZM resistance has been explored, including inherent and acquired mutations and inducible prosurvival signaling5. Therefore, there is an urgent need for developing new medications and treatment regimens for MM. The combination of BZM with other novel therapeutic agents may enhance its therapeutic effect and may even overcome resistance.

The Wnt signaling pathway plays a key role in regulating the cellular processes of proliferation, differentiation, and migration and is associated with multiple aspects of diseases. β-Catenin, a messenger molecule relevant to growth and survival, is degraded through the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway. Recently, evidence has also indicated that the dysregulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling has been implicated in hematological malignancies, including MM6. The related factors include increased expression of Wnt transcriptional cofactors and associated microRNAs and disturbed epigenetics and posttranslational modification processes7. β-Catenin inhibitors have been tested and proven efficacious as a monotherapy or in combination with BZM for treating myeloma8. Interestingly, Wnt/β-catenin signaling has also been linked to the molecular basis of BZM drug resistance9, and BZM treatment causes nuclear β-catenin accumulation, presumably due to reduced β-catenin degradation10. Thus, strategies that target Wnt/β-catenin may improve the efficacy of BZM in MM treatment.

Epigenetic agents have now shown considerable efficacy against hematological malignances11,12. Decitabine (5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine; DAC) is an adeoxynucleoside analog of cytidine that selectively inhibits DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs); DAC is used for treating myelodysplastic syndrome and elder acute myeloid leukemia13. DAC binds DNMTs and decreases the levels of enzyme expression, leading to the consecutive reactivation of epigenetically silenced tumor suppressor genes in vitro and in vivo14. Increasing evidence has shown that DNA methylation is an epigenetic event related to gene expression, which is also important for the occurrence and development of MM15. Considering the existence of non-CpG island hypermethylation in MM16, DNA methylation is regarded as a prognostic marker for patients with MM17,18, and DNA methyltransferase inhibitors are regarded as promising agents for treating MM.

In this study, we investigated the effect of DAC combined with BZM on MM cells. We also evaluated their synergistic efficacy for treating MM and further explored the potential mechanism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture

Human MM cell lines NCI-H929 and RPMI 8226 were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATTC; Manassas, VA, USA). Cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco) in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at 37°C.

MTT Assays

Cell proliferation was analyzed by MTT assay (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Briefly, cells were seeded in 96-well plates and incubated in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 at 37°C. The cells were treated with DAC alone at different concentrations, and a second dosage was added at 24 h. The cells were then cultured for another 48 h. For the combination group, the second dosage of DAC and BZM was sequentially added 24 h later. After 48 h of combination treatment, the samples were analyzed by a microplate reader at 490 nm.

Apoptosis and TUNEL Assays

Cells were treated with DAC alone, BZM alone, and DAC combined with BZM for 72 h. The cells were washed with PBS and then resuspended in 100 μl of binding buffer. Annexin-V/propidium iodide (PI; BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA) staining assays were conducted and analyzed by flow cytometry (FC500; Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). TUNEL staining was performed using an In Situ Cell Death Detection kit (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The percentages of TUNEL+ cells from images of 10 randomly selected fields for each group were identified at a magnification of 200× (ECLIPSE80I; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Cell Cycle Analysis

Cells were seeded in 12-well plates (2 × 105/well). After treatment with DAC alone, BZM alone, or combination treatment for 72 h, the cells were collected separately and fixed in ice-cold 70% ethanol for 24 h. The cell cycle profiles were determined using PI staining and flow cytometry (FC500; Beckman Coulter).

Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol (Takara, Tokyo, Japan) and eluted with RNase-free water. cDNA was generated from the total RNA using a reverse transcription kit (Takara) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A SYBR-Green master mix kit (Takara) and Bio-Rad iQ5 system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) were used according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The specific primer sequences are shown in Table 1. The following cycling conditions were applied: 95°C for 10 min, 49 cycles at 95°C for 15 s, 61°C for 1 min, and 65°C for 15 s.

Table 1.

Sequences of Primers Used for qRT-PCR

| Forward | Reverse | |

|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | 5′-AAGGTCGGAGTCAACGGATT-3′ | 5′-CCATGGGTGGAATCATATTGG-3′ |

| DKK-1 | 5′-ATTCCAGCGCTGTTACTGTG-3′ | 5′-GAATTGCTGGTTTGATGGTG-3′ |

| sFRP-3 | 5′-ACATGACTAAGATGCCCAACCAC-3′ | 5′- GAGTGCATCCCTCACACTTCTCAG-3′ |

| DNMT3a | 5′- AGGAGCACAAACAGGAAGAGAAT-3′ | 5′- GGGTTCTGTTTTGCATGACCA-3′ |

| β-Catenin | 5′-GAGTGCTGAAGGTGCTATCTGTCTG-3′ | 5′-AGGTTCAGTTGCAGAACAAGGTCTT-3′ |

| Cyclin D1 | 5′-ATGTTCGTGGCCTCTAAGATGA-3′ | 5′-CTTGTTCGAGTTCACCTTGGAC-3′ |

| LEF-1 | 5′-GACGAGATGATCCCCTTCAA-3′ | 5′-GGACATGCCTTGTTTGGAGT-3′ |

| TCF-1 | 5′-GAGTCCAAGGCAGAGAAGGA-3′ | 5′-GTGGTGGATTCTTGGTGCTT-3′ |

Methylation-Specific Polymerase Chain Reaction (MSP)

Genomic DNA was extracted from cells, and subsequent bisulfite conversion of the genomic DNA was performed. The sequences of the methylation-specific primers for DNMT3a, DKK-1, and sFRP-3 are listed in Table 2. The methylation status of the CpG islands in the DNMT3a, DKK-1, and sFRP-3 gene promoters was determined by genomic DNA bisulfite treatment, followed by methylation-specific PCR (MSP). MSP was performed according to the following cycling conditions: 95°C for 10 min, 30 cycles of 95°C for 1 min, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s, and a final extension for 10 min at 72°C.

Table 2.

Primer Sequences for Methylation-Specific PCR (MSP)

| Primer for MSP | Forward Primer (5′→3′) | Reverse Primer (5′→3′) |

|---|---|---|

| DKK-1 | ||

| Methylated | GTTTATTATTGAGAAGGGAGAATCG | ATAAACTTAATTAAACAAACGCGTA |

| Unmethylated | TTATTATTGAGAAGGGAGAATTGG | AATAAACTTAATTAAACAAACACATA |

| sFRP-3 | ||

| Methylated | AAATATTTTTAGGAAGGAGGGTTTC | AAAATCGCAAACGATAAAATACG |

| Unmethylated | AAATATTTTTAGGAAGGAGGGTTTT | AAAATCACAAACAATAAAATACAAA |

| DNMT3a | ||

| Methylated | GAATTTTTCGAAGGAAAATTTTTTC | CTCCCTAACTAACACAAAACATAACG |

| Unmethylated | ATTTTTTGAAGGAAAATTTTTTTGT | CCCTAACTAACACAAAACATAACATA |

Luciferase Assay

Cells were seeded into 24-well plates and transfected with the TOPFlash/FOPFlash reporter plasmids (Millipore, Temecula, CA, USA), as well as pRL-SV40 (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) to normalize for transfection efficiency, with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA USA). After a 24-h incubation, the cells were treated with the drugs and then analyzed with a Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega).

Detections of p-GSK3β (Ser9) Expression by Flow Cytometry (FCM)

The PE-conjugated monoclonal fluorescent antibody p-GSK3β (Ser9; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA) was used to identify p-GSK3β (Ser9) expression. Cells were plated in six-well plates, incubated, and harvested after treatment. The cells were then fixed with fixation agent for 15 min at room temperature and washed with PBS. Next, they were permeabilized with permeability agent for 5 min and incubated with an antibody against p-GSK3β (Ser9) at 4°C for 30 min. The samples were then analyzed by flow cytometry.

Western Blot Analysis

Nuclear proteins were extracted with Beyotime Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagents (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Haimen, P.R. China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The proteins were electrophoretically transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA, USA). After blocking with 5% nonfat milk for 3 h, the membranes were incubated with the respective primary antibodies, including anti-GAPDH, anti-lamin B1, anti-β-catenin, anti-GSK3β, anti-cyclin D1, anti-caspase 3, and anti-c-Myc (all from Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), at 4°C overnight. The membranes were then incubated with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. Finally, the membranes were exposed with enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL; Millipore Corporation).

Immunofluorescence Assay

Cells were plated on polylysine-coated slides, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min at room temperature, and washed with PBS. The cells were permeabilized with 1% Triton X-100 for 15 min and incubated with 1% BSA for 1 h at room temperature. After washing with PBS, the cells were incubated with a specific primary anti-β-catenin antibody (1:250; Abcam) at 4°C overnight, followed by incubation with the secondary antibody rhodamine (TRITC)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG for 1 h. The stained slides were viewed under a fluorescence microscope at a magnification of 400× (ECLIPSE80I; Nikon).

Xenograft Transplantation and Immunohistochemistry

Nude mice were provided by the Fourth Military Medical University. All animals were housed in an environment with a temperature of 22 ± 1°C, a relative humidity of 50 ± 1%, and a light/dark cycle of 12:12 h. In addition, all animal studies (including the mouse euthanasia procedure) were performed in compliance with the regulations and guidelines of the Fourth Military Medical University Institutional Animal Care Committee and conducted according to the AAALAC and the IACUC guidelines.

NCI-H929 cells (1 × 107 cells per mouse) in 100 μl of serum-free RPMI-1640 medium were injected subcutaneously into the flanks of the mice. When the tumors reached approximately 50 mm3, the mice were divided randomly into four groups: a control (PBS) group, a BZM group, a DAC group, and a BZM plus DAC group. BZM (0.5 mg/kg) was injected IV twice a week, and 0.5 mg/kg DAC was given IP for 5 consecutive days. Tumor volumes were calculated using the following formula: length × width2/2. All animals were euthanized, and tumor tissues were analyzed by TUNEL assays.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were carried out using the SPSS 17.0 statistical software. Statistical analysis was conducted using standard one-way analysis of variance. Data are shown as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Combining BZM With DAC Enhances the Inhibition of MM Cells

MTT assays were used to evaluate the effects of DAC alone, BZM alone, and DAC combined with BZM on MM cell viability. RPMI-8226 cells and NCI-H929 cells were treated with different drug concentrations. As shown in Figure 1A and B, cell proliferation was inhibited in a dose-dependent manner upon treatment with increasing concentrations of DAC (0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 5.0, 10.0, and 20.0 μM) for 72 h. For RPMI-8226 cells, the inhibition of DAC was significantly increased to 10.0 ± 0.21%, 30.0 ± 1.65%, and 50.0 ± 1.92% with doses of 1.0, 5.0, and 10.0 μM. DAC inhibited cell growth approximately onefold more in NCI-H929 cells than in RPMI-8226 cells. These results showed that the proliferation of MM cells was inhibited by adding DAC alone. The concentration of DAC we chose for both RPMI-8226 and NCI-H929 cells was 1.0 μM for the combination group, and the combined doses of BZM were 10.0, 15.0, and 20.0 nM. As shown in Figure 1C and D, the sequential combination of DAC and BZM showed a synergistic effect, and the inhibition rate was significantly increased, as estimated by combination index (CI) values of <1.0. The Chou–Talalay method was applied to calculate the CI, which quantitatively established additivity (CI = 1), synergy (CI < 1), and antagonism (CI > 1).

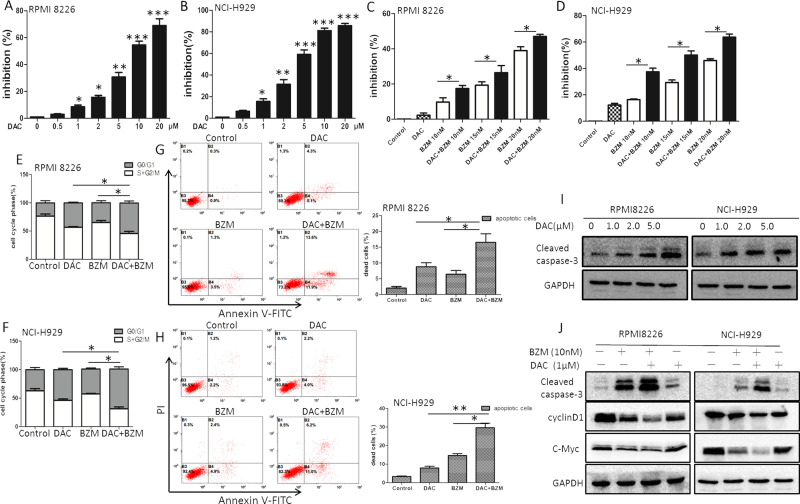

Figure 1.

Effects of decitabine (DAC) in combination with bortezomib (BZM) on the proliferation and apoptosis of myeloma cells. (A, B) Dose-dependent growth inhibition was observed after single doses of DAC. (C, D) Multiple myeloma (MM) cells were pretreated with DAC (1.0 μM) for 24 h and in combination with BZM for 48 h. Inhibition rates were determined by MTT assay. (E, F) The cell cycle was measured by flow cytometric analyses. (G, H) Apoptosis rates were determined by flow cytometric analyses. (I, J) Protein expression levels of caspase 3, cyclin D1, and c-Myc were examined by Western blotting. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 versus the single treatment group.

DAC and BZM Induce Cell Cycle Arrest in MM Cells

The effect of DAC and BZM on cell cycle progression was analyzed by flow cytometry. As shown in Figure 1E, approximately 25%–30% of RPMI-8226 cells remained in the G0/G1 phase. DAC (1.0 μM) alone induced approximately 45% cell arrest at the G0/G1 phase of the cell cycle, while BZM (10 nM) alone induced approximately 35% cell arrest at the G0/G1 phase. Interestingly, the combination of DAC (1.0 μM) with BZM (10 nM) induced approximately 60%–70% cell arrest at the G0/G1 phase, and approximately 30% more cells were arrested than in the nontreatment group. A similar result was observed for the NCI-H929 cell line (Fig. 1F). These data indicated that DAC and BZM treatment led to a higher rate of G1 arrest.

Combination With DAC Enhances BZM-Induced Apoptosis in MM Cells

To analyze cell apoptosis rates, we conducted flow cytometry. These data are shown in Figure 1G and H. In RPMI-8226 cells, DAC (1.0 μM) alone yielded approximately 9.6 ± 1.78% apoptotic cells, BZM alone yielded 4.8 ± 0.50% apoptotic cells, and combination treatment yielded approximately 25.5 ± 2.93% apoptotic cells. The apoptosis rates in the combination groups were significantly higher in both RPMI-8226 and NCI-H929 cells than those in the single reagent treatment groups.

Related Downstream Effector Molecules in MM Cells After DAC Treatment and DAC Combined With BZM Treatment

We examined cell proliferation- and apoptotic-related molecules after treatment with DAC alone, BZM alone, and DAC/BZM in combination. These data are shown in Figure 1I. In RPMI-8226 cells, DAC (1.0 μM) alone induced the expression of activated cleaved caspase 3 compared to control treatment, and this induction was dose dependent. Additionally, BZM alone induced cleaved caspase 3, while combination treatment induced the highest level of cleaved caspase 3 expression (Fig. 1J). Additionally, the gene expression of c-Myc and cyclin D1 in MM cells was significantly lower in the combination group than in the single drug treatment (Fig. 1J). c-Myc and cyclin D1 are downstream effector molecules involved in Wnt/β-catenin signaling. In our study, we found that these related genes were decreased in MM cells after DAC and BZM treatment and significantly decreased upon combination treatment, suggesting that DAC might synergistically affect the cell proliferation and apoptosis induced by BZM through Wnt/β-catenin-related effectors.

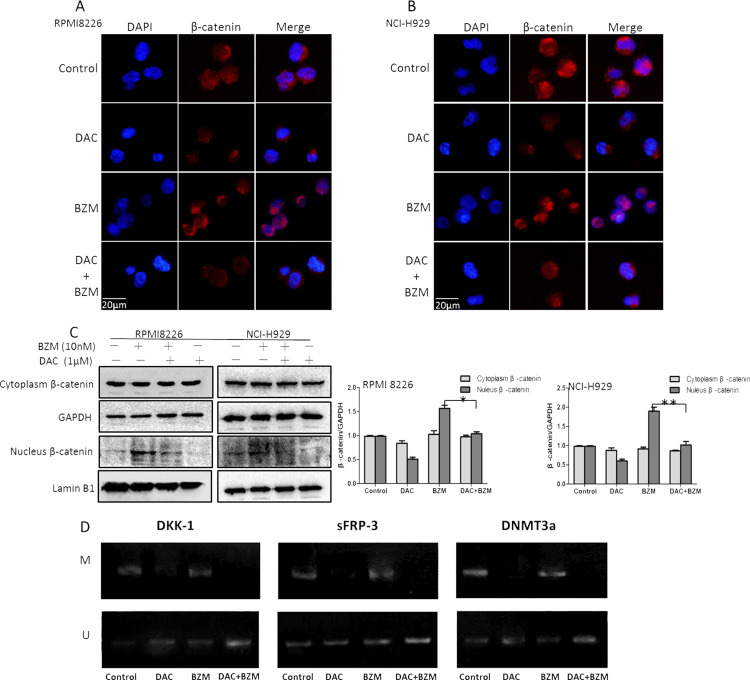

DAC Reduced the BZM-Induced β-Catenin Accumulation in the Nucleus and Demethylated Wnt Antagonists

We examined the expression and cellular location of β-catenin by Western blotting and immunofluorescent staining in the single drug treatment and combination treatment groups. As shown in Figure 2A–C, we found that nucleic β-catenin was obviously increased upon BZM treatment alone. This finding is consistent with those of previous reports, but the underlying mechanism is unknown; presumably, this phenomenon occurs because of the decreased protein degradation caused by protease inhibitors. We found that DAC alone decreased nucleic β-catenin accumulation, and nucleic β-catenin was obviously decreased in the combination group compared to that in the BZM group. Nucleic β-catenin accumulation was also confirmed by fluorescence microscopy analyses of immunofluorescent staining of PE-conjugated β-catenin and DAPI staining of the nuclei.

Figure 2.

Effects of DAC in combination with BZM on β-catenin and Wnt antagonists in myeloma cells. (A, B) Immunofluorescence images of β-catenin. Original magnification: 400×. (C) Protein lysates were subjected to immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. GAPDH and lamin B1 were analyzed as controls. (D) Methylation-specific PCR (MSP) analysis of Wnt antagonists and DNMT3a in NCI-H929 cells. U indicates the presence of unmethylated genes, and M indicates the presence of methylated genes. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 versus the single treatment group.

Methylation-specific PCR (MSP) was used to examine the CpG methylation status of Wnt antagonists (DKK-1 and sFRP-3) and DNMT3a in MM cell lines. Decreased methylation of the promoters for the DKK-1, sFRP-3, and DNMT3a genes was observed in the NCI-H929 cell line treated with DAC and the drug combination, but this demethylation was not observed for BZM treatment alone (Fig. 2D).

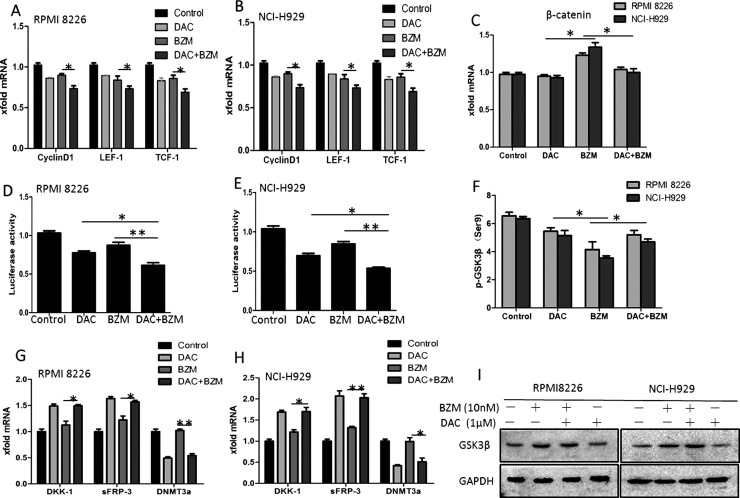

DAC With BZM Repressed β-Catenin-Related Transcription and Synergistically Inhibited Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling

We examined and compared the mRNA levels of downstream effectors of β-catenin, such as cyclin D1, LEF-1, and TCF-1, by qRT-PCR in the DAC alone and BZM alone treatment groups and in the drug combination group. In our study, compared to BZM alone, the combination of DAC and BZM obviously downregulated the transcriptomes of these genes (Fig. 3A and B). Interestingly, as shown in Figure 3C, we found that although BZM alone increased the mRNA levels of β-catenin, neither DAC alone nor combination treatment changed the mRNA levels of β-catenin (p < 0.05). We also examined the transcript activity of LEF-1/TCF-1 by luciferase assay, and the results showed that LEF-1/TCF-1 activity was obviously lower in the combination treatment group than in the DAC alone treatment group and even more so than in the BZM alone treatment group (Fig. 3D and E). Using RT-PCR, we found that DKK-1 and sFRP-3 mRNA was increased after DAC treatment, while DNMT3a was decreased; these results indicate that DAC may demethylate Wnt antagonists to induce their reexpression. This effect was also observed in the combination treatment group (Fig. 3G and H). GSK-3β is a serine–threonine kinase that controls insulin, NF-κB signaling, and especially Wnt/β-catenin in cells. Recent evidence suggests that GSK-3β could function as a growth-promoting kinase, especially in malignant cells. In this study, we investigated GSK-3β phosphorylation in MM after DAC, BZM, or combination treatment. Consistent with the β-catenin nuclear translocation, DAC decreased GSK-3β (Ser9) phosphorylation, while BZM increased GSK-3β (Ser9) phosphorylation. In addition, compared with BZM alone, the combination treatment decreased GSK-3β (Ser9) phosphorylation (Fig. 3F).

Figure 3.

Effects of DAC in combination with BZM on cell cycle and expression levels of cyclin D1, LEF-1, TCF-1, and p-GSK-3β. (A, B) The mRNA expression of downstream genes of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway was measured by quantitative real-time (qRT)-PCR. (C) The mRNA expression of β-catenin was measured by qRT-PCR. (D, E) The activity of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway was detected by TOP/FOP flash experiments. (F) FCM analysis of p-GSK3β (Ser9) in the cytoplasm of MM cells. (G, H) The mRNA expression of Wnt antagonists of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and DNMT3a was measured by qRT-PCR. (I) Protein lysates were subjected to immunoblotting with total GSK3β antibodies. GAPDH was analyzed as a control. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 versus the single treatment group.

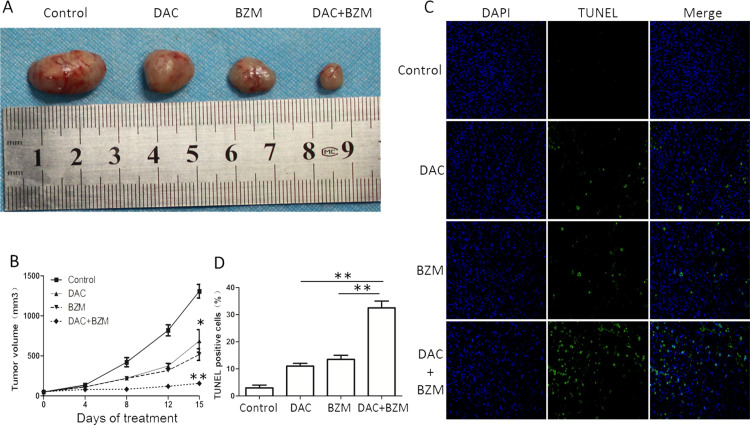

The Combination of DAC and BZM Efficiently Inhibits Tumor Growth in a MM Mouse Model

Xenograft mouse models were treated with DAC (0.5 mg/kg/day) for 5 consecutive days, followed by BZM (0.5 mg/kg) twice a week, while the control groups were treated with a single agent and PBS. The tumors in the combination group were dramatically lower than those in the control and single treatment groups (Fig. 4A and B).

Figure 4.

Effects of DAC in combination with BZM in a MM mouse model. (A) MM mice transplanted with H929 cells were treated with PBS, DAC (0.5 mg/kg; IP; 5 consecutive days), BZM (0.5 mg/kg; IV; twice a week), and DAC in combination with BZM. The drugs were given for 15 days. Tumor volumes were expressed as the mean ± SD (n ≥ 3). (B) Time curve of the tumor volumes. (C, D) TUNEL assays in tumor tissues. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 versus the single treatment group.

Furthermore, we performed TUNEL assays to confirm the apoptotic effects of DAC and BZM. The staining results showed that the number of TUNEL+ cells in the tumor tissues were remarkably higher in the combination group than in the other groups (Fig. 4C and D). These results demonstrated that the combination of the two drugs significantly inhibited tumor growth.

DISCUSSION

The highly conserved Wnt signaling pathway plays a central role in regulating cell proliferation, apoptosis, and differentiation and is related to multiple aspects of tumors, including MM7. It has been shown that Wnt/β-catenin signaling through β-catenin/TCF-regulated transcription is active in MM. When MM cell lines were treated with an active mutant form of β-catenin, they showed higher levels of nonphosphorylated nuclear β-catenin and significantly increased cellular proliferation19. A previous study has also shown that β-catenin siRNA targets inhibit the proliferation of myeloma cells in vivo and in vitro20. Furthermore, the small molecule β-catenin inhibitor BC2059 that blocks the canonical Wnt signaling pathway was efficacious in MM as a monotherapy or in combination with BZM8. As β-catenin is essential for regulating the sensitivity of myeloma cells to BZM21, we investigated the expression level of β-catenin in the myeloma cell lines NCI-H929 and RPMI-8226 in our study. The results showed that upon BZM treatment, β-catenin was upregulated in both cell types, indicating that BZM might induce more active β-cat-regulated transcription (CRT).

In this study, we observed that DAC and BZM had a synergistic antiproliferative effect in myeloma cells. We also revealed that DAC synergistically induced apoptosis by activating cleaved caspase 3 and arresting the cell cycle. Cyclin D1, a β-catenin downstream target gene that is necessary for the progression of cells from G1 phase to S phase (DNA synthesis)22, was obviously decreased in MM cells treated with DAC (Fig. 1J). A rapid decrease in cyclin D1 in MM cells pretreated with DAC and then treated with BZM caused greater G1/S phase arrest, thus leading to more obvious suppression of cell proliferation. G1/S arrest in MM cells was induced through the downregulation of the downstream targets of β-catenin, including cyclin D1, c-Myc, and LEF/TCF. These data suggested a specific biological mechanism resulting in a concerted effect.

Additionally, we demonstrated that the levels of cytoplasmic and nuclear β-catenin proteins were significantly downregulated following DAC treatment (Fig. 2A–C). The Wnt/β-catenin pathway could also be enhanced due to the loss of its antagonists, which are associated with gene-promoter hypermethylation. Because DAC induces tumor suppressor gene reexpression based on its gene-specific DNA hypomethylation, we determined the methylation status of the Wnt antagonists DKK-1 and sFRP-3. The results revealed that DKK-1 and sFRP-3 were demethylated and reexpressed after DAC treatment, while the same demethylation effect induced by DAC was observed for DNMT3a (Fig. 2D). Accordingly, myeloma cell lines treated with DAC presented with Wnt antagonist demethylation, transcript reexpression, and Wnt signaling downregulation.

By examining β-catenin mRNA, we found that DAC did not interrupt β-catenin transcriptome levels directly. However, DAC could interrupt β-catenin’s nuclear accumulation, which may be caused by Wnt receptor antagonist demethylation. p-GSK3β was decreased after DAC treatment, which also indicated that Wnt signaling was suppressed by DAC; total GSK3β levels in the DAC group were the same as those in the control group, while BZM alone also decreased p-GSK3 (Ser9) (Fig. 3F and I). A previous study also showed that BZM treatment could decrease p-GSK3α/β in the MM cell line U26610. This finding indicated that DAC and BZM might both play roles in the Wnt/GSK3 axis and synergistically affect MM cell proliferation and apoptosis.

Because the regulation of β-catenin accumulation is highly related to the sensitivity of myeloma cells to BZM, we investigated whether DAC plays a role in β-catenin accumulation and regulates the sensitivity of myeloma cells to BZM. We found that the sequential combination treatment of DAC and BZM efficiently inhibited the formation of MM cell clones and growth in a subcutaneous MM mouse model (Fig. 4A). Immunochemistry staining of the myeloma tissue showed that TUNEL staining intensity was obviously higher in the combination group than that in the single DAC or BZM treatment groups (Fig. 4C and D).

In this study, we found that pretreatment of MM cells with DAC followed by BZM led to a synergistic effect. A previous study demonstrated that β-catenin protein levels are negatively associated with the sensitivity of myeloma cells to BZM21. In the present study, however, DAC reduced the accumulation of β-catenin after proteasome inhibition and enhanced the sensitivity of myeloma cells to BZM.

In summary, our study found that the demethylation agent DAC combined with BZM had synergistic antitumor efficacy in the treatment of MM through the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. The identification of the synergistic effect of DAC and BZM might lead to a better therapeutic approach for MM.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded by the National Nature Science Foundation of China (No: 81172247 and 31270930).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. Anderson KC, Alsina M, Bensinger W, Biermann JS, Chanan-Khan A, Cohen AD, Devine S, Djulbegovic B, Faber EA Jr, Gasparetto C, Huff CA, Kassim A, Medeiros BC, Meredith R, Raje N, Schriber J, Singhal S, Somlo G, Stockerl-Goldstein K, Treon SP, Tricot G, Weber DM, Yahalom J, Yunus F. Multiple myeloma. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2011;9(10):1146–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Reeder CB, Reece DE, Kukreti V, Mikhael JR, Chen C, Trudel S, Laumann K, Vohra H, Fonseca R, Bergsagel PL, Leis JF, Tiedemann R, Stewart AK. Long-term survival with cyclophosphamide, bortezomib and dexamethasone induction therapy in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 2014;167(4):563–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Moreau P, Attal M, Facon T. Frontline therapy of multiple myeloma. Blood 2015;125(20):3076–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Uematsu A, Kido K, Manabe E, Takeda H, Takahashi H, Hayashi M, Imai Y, Sawasaki T. DANFIN functions as an inhibitor of transcription factor NF-kappaB and potentiates the antitumor effect of bortezomib in multiple myeloma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;495(3):2289–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Murray MY, Auger MJ, Bowles KM. Overcoming bortezomib resistance in multiple myeloma. Biochem Soc Trans. 2014;42(4):804–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Valencia A, Roman-Gomez J, Cervera J, Such E, Barragan E, Bolufer P, Moscardo F, Sanz GF, Sanz MA. Wnt signaling pathway is epigenetically regulated by methylation of Wnt antagonists in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 2009;23(9):1658–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Spaan I, Raymakers RA, van de Stolpe A, Peperzak V. Wnt signaling in multiple myeloma: A central player in disease with therapeutic potential. J Hematol Oncol. 2018;11(1):67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Savvidou I, Khong T, Cuddihy A, McLean C, Horrigan S, Spencer A. Beta-Catenin inhibitor BC2059 is efficacious as monotherapy or in combination with proteasome inhibitor bortezomib in multiple myeloma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2017;16(9):1765–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chong KY, Hsu CJ, Hung TH, Hu HS, Huang TT, Wang TH, Wang C, Chen CM, Choo KB, Tseng CP. Wnt pathway activation and ABCB1 expression account for attenuation of proteasome inhibitor-mediated apoptosis in multidrug-resistant cancer cells. Cancer Biol Ther. 2015;16(1):149–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Piazza F, Manni S, Tubi LQ, Montini B, Pavan L, Colpo A, Gnoato M, Cabrelle A, Adami F, Zambello R, et al. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 regulates multiple myeloma cell growth and bortezomib-induced cell death. BMC Cancer 2010;10:526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Maes K, Menu E, Van Valckenborgh E, Van Riet I, Vanderkerken K, De Bruyne E. Epigenetic modulating agents as a new therapeutic approach in multiple myeloma. Cancers (Basel) 2013;5(2):430–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dimopoulos K, Gimsing P, Gronbaek K. The role of epigenetics in the biology of multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer J. 2014;4:e207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Curran MP. Decitabine: A review of its use in older patients with acute myeloid leukaemia. Drugs Aging 2013;30(6):447–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Toyota M, Kopecky KJ, Toyota MO, Jair KW, Willman CL, Issa JP. Methylation profiling in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 2001;97(9):2823–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. San-Miguel J, Garcia-Sanz R, Lopez-Perez R. Analysis of methylation pattern in multiple myeloma. Acta Haematol. 2005;114(Suppl 1):23–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Heuck CJ, Mehta J, Bhagat T, Gundabolu K, Yu Y, Khan S, Chrysofakis G, Schinke C, Tariman J, Vickrey E, et al. Myeloma is characterized by stage-specific alterations in DNA methylation that occur early during myelomagenesis. J Immunol. 2013;190(6):2966–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Walker BA, Wardell CP, Chiecchio L, Smith EM, Boyd KD, Neri A, Davies FE, Ross FM, Morgan GJ. Aberrant global methylation patterns affect the molecular pathogenesis and prognosis of multiple myeloma. Blood 2011;117(2):553–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kaiser MF, Johnson DC, Wu P, Walker BA, Brioli A, Mirabella F, Wardell CP, Melchor L, Davies FE, Morgan GJ. Global methylation analysis identifies prognostically important epigenetically inactivated tumor suppressor genes in multiple myeloma. Blood 2013;122(2):219–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Derksen PW, Tjin E, Meijer HP, Klok MD, MacGillavry HD, van Oers MH, Lokhorst HM, Bloem AC, Clevers H, Nusse R and others. Illegitimate WNT signaling promotes proliferation of multiple myeloma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004;101(16):6122–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ashihara E, Kawata E, Nakagawa Y, Shimazaski C, Kuroda J, Taniguchi K, Uchiyama H, Tanaka R, Yokota A, Takeuchi M and others. Beta-catenin small interfering RNA successfully suppressed progression of multiple myeloma in a mouse model. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(8):2731–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhou LL, Fu WJ, Yuan ZG, Wang DX, Hou J. [Study on the relationship of beta-catenin level and sensitivity to bortezomib of myeloma cell lines]. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi 2008;29(4):234–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Matsushime H, Quelle DE, Shurtleff SA, Shibuya M, Sherr CJ, Kato JY. D-type cyclin-dependent kinase activity in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14(3):2066–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]