Abstract

The formation of the coarse columnar crystal structure of Ti-6Al-4V alloy in the process of additive manufacturing greatly reduces the mechanical performance of the additive manufactured parts, which hinders the applications of additive manufacturing techniques in the engineering fields. In order to refine the microstructure of the materials using the high intensity ultrasonic via the acoustic cavitation and acoustic flow effect in the process of metal solidification, an ultrasonic vibration technique was developed to a synchronous couple in the process of Laser and Wire Additive Manufacturing (LWAM) in this work. It is found that the introduction of high-intensity ultrasound effectively interrupts the epitaxial growth tendency of prior-β crystal and weakens the texture strength of prior-β crystal. The microstructure of Ti-6Al-4V alloy converts to fine columnar crystals from typical coarse columnar crystals. The simulation results confirm that the acoustic cavitation effect applied to the molten pool created by the high-intensity ultrasound is the key factor that affects the crystal characteristics.

Keywords: High-intensity ultrasound, Laser and wire additive manufacturing, Ti-6Al-4V alloy, Grain refining, Acoustic cavitation

1. Introduction

Laser and Wire Additive Manufacturing (LWAM) is a novel technique with low cost and high deposition efficiency. This technique is applicable to manufacture the large and complex structural parts made up of various metals and alloys. However, due to its rapid melting and solidification process, there is a sharp temperature gradient in the molten pool, which usually causes the formation of coarse columnar crystals in the most of additive manufacturing metal components. These coarse columnar crystals will lead to the obvious property anisotropy, on the other hand, it also causes the strength, toughness, damage tolerance, and fatigue performance of the components fabricated by LWAM be lower than that of the forgings. Thus, the abovementioned defects limit the application of the LWAM technique to apply in the additive manufacture of the metal components, especially for a large structural part in the industrial fields.

Ti-6Al-4V alloy, with the advantages of low density, high strength, excellent corrosion resistance, and high-temperature mechanical properties, has been widely used in aerospace, transportation, biomedical, and other fields [1]. Recently, many researchers utilize additive manufacturing techniques to prepare lightweight and complex titanium alloy components. The microstructure and mechanical properties of Ti-6Al-4V alloy fabricated by different additive manufacturing techniques have been studied until now. The numerous results [2], [3], [4], [5], [6] show that it is easy for Ti-6Al-4V alloy to form coarse columnar crystals in the additive manufacturing process and the coarse columnar crystals can span multiple deposition layers. The maximum crystal size can reach a few millimeters along the building direction, which causes property anisotropy and poor mechanical performance. Therefore, how to improve the deposition microstructure of Ti-6Al-4V alloy and obtain small-size equiaxed grains with a simple and easy process is the bottleneck technique that needs to solve in the field of titanium alloy additive manufacturing.

Attempts to optimize the processing parameters of additive manufacturing have been performed completely on the in situ martensite decomposition of Ti-6Al-4V alloy with outstanding mechanical properties fabricated by Selective Laser Melting (SLM) [7]. However, based on the characteristic of LWAM, it is difficult to alter the conditions to promote equiaxed growth of Ti-6Al-4V alloy grains in LWAM. Some researchers found that the nucleation ability of titanium alloy can be improved by adding alloy elements [8], [9], such as the copper element. The results show that the nucleation rate of titanium alloy during solidification can be improved by the addition of copper element, and the Ti-Cu alloy prepared by additive manufacturing obtains fine equiaxed crystal without any treatment [8]. Another study demonstrates that trace boron addition to Ti-6Al-4V components produced by Wire +Arc Additive Manufacturing (WAAM) is an effective way to eliminate the deleterious anisotropic microstructures existing often in the Ti-6Al-4V alloy parts by additive manufacturing technique [9]. However, the introduction of the alloy elements into Ti-6Al-4V alloy will change the composition and other properties to some extent compared to the original materials, leading to a negative consequence through the formation of brittle second phases (e.g., TiB and Ti2Cu) that will produce a certain degree of segregation in the solidification process of the molten pool. Also, this technique to improve the microstructure and mechanical properties via the addition of alloying elements is limited in the application fields where the composition of titanium alloy is strictly required.

Besides the aforementioned method to introduce a chemical element into titanium alloy, there are two online processing methods proposed to improve the microstructure of titanium alloy components and obtain equiaxed fine grains, they are so-called mechanical rolling technique [10], [11], [12] and ultrasonic vibration technique [13]. The mechanical rolling technique was used to treat the deposited layers of large scale Ti-6Al-4V parts fabricated by WAAM [10], [11], [12]. It has been found that when the rolling applied to each deposited layers in the process of WAAM, the normally coarse centimeter-scale columnar β grain structure could be refined down to <100 μm which reduces the texture strength of β phase and α phase in the material, weakens the anisotropy of the material and improves the performance of the Ti-6Al-4V alloy. However, a greater pressure (up to 75 kN) [11] must be employed to ensure the deposition layer to create large plastic deformation for refining the grain size, which will cause severe plastic deformation, and even damage thin-walled parts when a large load is applied to the thin-walled parts or complex parts in the inner cavity, Therefore, this method is not available for controlling the grain size of titanium alloy, when used to additive manufacturing of the complex parts.

Another method to improve the microstructure and mechanical properties is the ultrasonic vibration technique, which has been widely used in the welding and casting fields. The effects of high-intensity ultrasound on the microstructure and properties of materials during solidification and crystallization have been investigated thoroughly [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20]. The results show that, in the solidification process of materials, acoustic cavitation and acoustic streaming can increase the nucleation and reduce the composition segregation, and then the fine equiaxed crystal can be obtained. Recently, such a high-strength ultrasonic technique was employed in additive manufacturing to control the solidification process of Ti-6Al-4V alloy [13]. It was concluded that the microstructure of Ti-6Al-4V alloy is converted to fine equiaxed crystal from coarse columnar crystal due to the effect of ultrasonic energy field on the molten pool of deposition layer in the process of additive manufacturing, since the formation of acoustic cavitation and streaming in the liquid metal by high-intensity ultrasound can vigorously agitate the melt during solidification, thereby promoting significant structural modification or refinement [13].

It should be recognized that owing to the attenuation of sound waves including the diffusion attenuation, scattering attenuation, and viscous attenuation during the propagation of the ultrasonic wave in the medium, the ultrasonic energy gradually weakens with increasing propagation distance. Thus, with increasing deposition layer number and component size, the effect of the ultrasonic energy field on the solidification process in the molten pool at the top of the component becomes weaker and weaker. Therefore, this technique is not available in the additive manufacturing of large-scale titanium alloy components. Also, during the implementation of this technique, the ultrasonic energy field must be applied from the bottom of the component to realize synchronously track and accurately interfere with the molten pool on the top of the deposition layer. Such that the ultrasonic device on the bottom and the high-energy beam deposition head on the upper part must synchronously coordinate the movement according to the planned path, implying that this technique is hardly employed in the additive manufacturing of large-scale and complex structural titanium alloy components. To address this challenge, a novel ultrasonic vibration device was designed for developing an ultrasonic vibration-assisted additive manufacturing technique in this work. In which the transducer, ultrasonic amplitude transformer, and tool head were connected rigidly and integrated into the LWAM device [21]. In such an online microstructure-improved LWAM, each deposition layer was treated simultaneously, the epitaxial growth of dendrites was interrupted and the coarse columnar crystal was refined due to the effect of the high intensity ultrasonic.

In the present work, we focus on investigating the influence of high-intensity ultrasound on the microstructure of Ti-6Al-4V alloy fabricated by LWAM. Firstly, in order to investigate the effect of ultrasonic vibration and ensure the credibility of the experimental results, the single pass-multilayer specimen was designed to study the effect of ultrasonic on the microstructure of the deposited layer in different states. That is to say, there are four zones in the deposition layer, which are affected by with/without ultrasonic vibration. Secondly, the acoustic cavitation induced by high-intensity ultrasound in the molten pool during the LWAM process was studied using the finite element method and the numerical calculation method. Finally, based on the experimental results and calculation results, the mechanism of microstructure change from coarse columnar crystal to fine columnar crystal was discussed.

2. Experiments

The details of the overall layout diagram of the LWAM assisted with ultrasonic vibration are shown in Fig. 1. The whole device mainly consists of two parts, including the ultrasonic vibration system composed of a pneumatic cylinder and ultrasonic vibration device, and the LWAM system composed of a laser heat source and wire feeder. Both of them are integrated into the manipulator and the ultrasonic vibration device is fixed to the pneumatic cylinder (see Fig. 1a). In the process of LWAM assisted with ultrasonic vibration, a constant pressure (~100 MPa) under the steady load of about 200 N is applied by the pneumatic cylinder to keep the contact state between the ultrasonic probe and the deposition layer without separation, among that the contact surface area between the ultrasonic probe and deposited layer is approximately 2.0 mm2. A remarkable design feature of the ultrasonic vibration devices is that the amplitude transformer and the ultrasonic probe are connected rigidly (see Fig. 1b). Additionally, it is well-known that, during the process of the LWAM, the temperature around the molten pool is very high. Based on the working condition, and in order to prolong the service life of the ultrasonic probe, the SKD-11 cold mold steel is selected to fabricate the ultrasonic probe, which has good high-temperature strength, toughness, and good wear resistance.

Fig. 1.

Set-up for LWAM assisted with ultrasonic vibration. overall arrangement diagram (a), an ultrasonic vibration device (b), and the principle schematic of the LWAM process assisted with ultrasonic vibration (c).

The principle schematic of the LWAM process assisted with ultrasonic vibration is shown in Fig. 1c. The LWAM system and ultrasonic vibration device were connected by a 6-axis ABB robot, and the offset between them was 20 mm. The commercial Ti-6Al-4V alloy wire (1.2 mm in diameter) and the Ti-6Al-4V alloy substrate plates with a thickness of ~20 mm were used in this study. In the process of LWAM, the high-intensity ultrasound was used to treat the deposition layer synchronously. To analyze the effects of ultrasonic on grain fragmentation in a molten pool of LWAM Ti-6Al-4V alloy, the following experimental scheme was designed, and the detailed deposition process described as follows: a) the LWAM system started from point A; b) the ultrasonic vibration device was applied to point B through the control systems when the LWAM system (molten pool) moved to point C; c) then the LWAM system and the ultrasonic vibration device moved synchronously under the control of the manipulator's arm; d) when the LWAM system (molten pool) moved to point E, the ultrasonic vibration device ran synchronously to point D and the two systems stopped working at the same time. In the whole deposition process, the specimens generated four regions as shown in Fig. 1c. Zone ‘R’ is the reference region and only the LMAM process is available. Zone ‘S’, is the area where the ultrasonic vibration only acts on the deposited layer (Solid). Zone ‘L + S’, includes the effect of ultrasonic vibration on the molten pool (Liquid) and deposited area (Solid). Zone ‘L’, is the effect of ultrasonic vibration only on the molten pool (Liquid). A single pass - multilayer specimen (about 12 mm in height) was built on Ti-6Al-4V alloy substrate using a laser power of 1200 W, deposition speed of 2 mm/s, the wire feed rate of 10 mm/s, and shield gas flow rate of 15 L/min; also, the frequency and input amplitude of ultrasonic apparatus generated are 20 kHz and 16 μm, respectively. Meanwhile, the angle α between the ultrasonic vibration device and the deposited layer was kept at 45°.

The macroscopic morphologies and the microstructures of a single pass-multilayer sample along the Y-Z plane and X-Z plane in four different regions were characterized using optical microscopy. The grain size and the aspect ratio of the prior-β grains were quantitatively measured using the image processing software (Image-Pro Plus). The crystallographic texture measurements were performed by an X-ray diffractometer (XRD, Philips X’pert MRD) with a Cu Kα X-ray diffraction system on the Y-Z section (acceleration voltage of 40 kV, the current of 30 mA, the scanning speed of 2°/min). Besides, the acoustic pressure and the acoustic cavitation in the molten pool were analyzed in detail using the finite element method.

3. Results and analysis

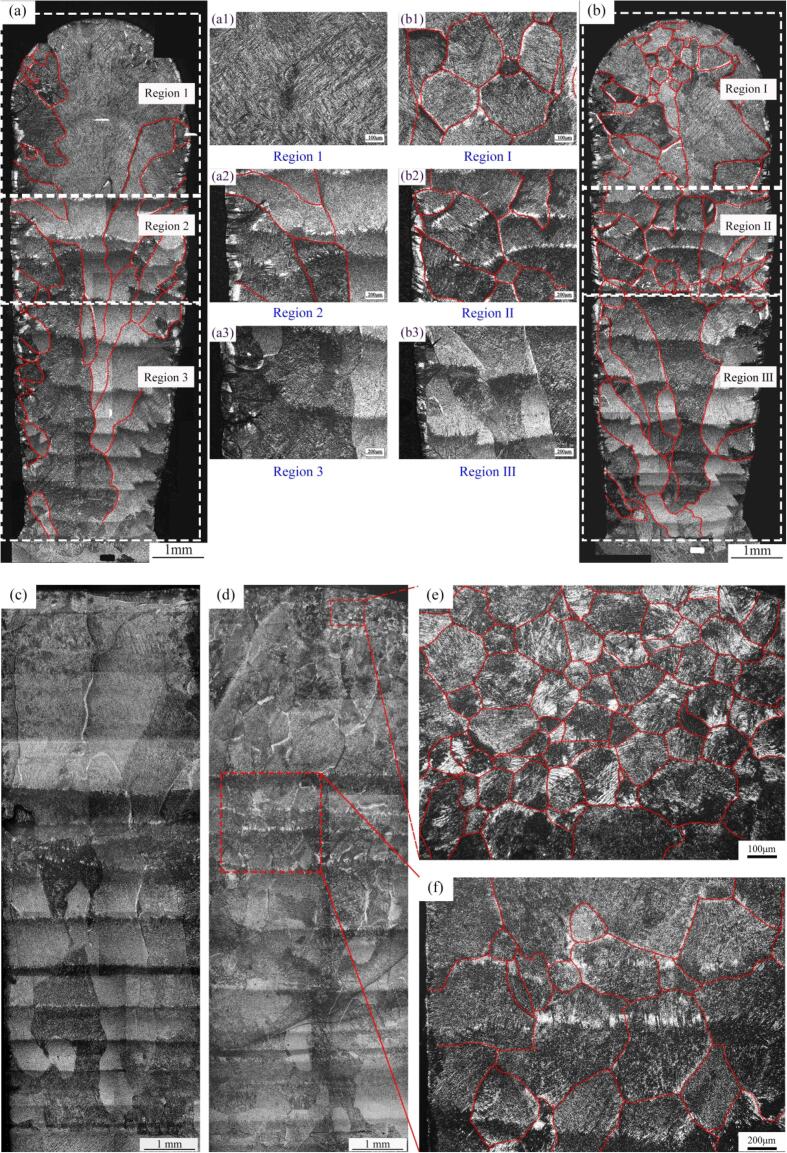

Fig. 2 shows the microstructure results. There are obvious differences between these zones when high-intensity ultrasonic acts on the deposited area (zone ‘S’) and the molten pool area (zone ‘L+S’ and zone ‘L’). Fig. 2a depicts the microstructures of the Y-Z plane in the zone ‘S’. It can be seen that typical coarse columnar prior-β grains with several millimeters of the grain size are formed, which grows along the building direction and traverses multiple deposited layers or even the entire sample. The steep temperature gradient that is the characteristic of additive manufacturing, is the main reason for the formation of coarse columnar crystals, which will lead to a strong epitaxial growth tendency of prior-β grains, especially for Ti-6Al-4V alloy with low nucleation rate [13]. The microstructure of zone ‘R’ with a typical coarse columnar prior-β grains is the same as that of zone ‘S’, which is not given here.

Fig. 2.

Micromorphology and microstructures of Ti6Al4V alloy fabricated by LWAM assisted with ultrasonic vibration: (a) and (b) are the microstructures of the Y-Z plane of zone ‘S’ and zone ‘L + S’, respectively. Corresponding, (c), and (d) are the microstructures of the X-Z plane. (e) and (f) are the microstructures of the marked area in (d). The prior-β grain boundaries are traced in red. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

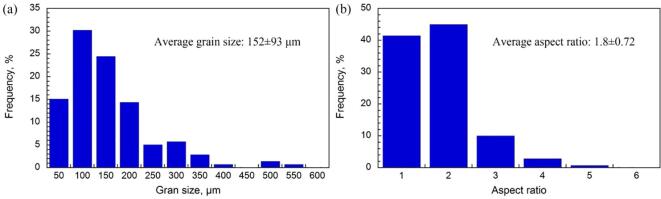

Fig. 2b shows the microstructures of the Y-Z plane in the zone ‘L+S’ (zone ‘L’ has the same microstructure). It can be seen that the microstructures of region ‘L+S’ have been changed obviously due to the introduction of high-intensity ultrasound. The sample is divided into three regions (Region I, Region II and Region III) according to the microstructures. In the first several layers of deposition, the same coarse columnar prior-β grains (Region III) are obtained (see Fig. 2b3). However, when the deposition layer reaches a certain height, a large number of fine columnar crystals appear at the interface between the Region III and Region II, which interrupts the epitaxial growth trend of the original columnar crystals (see Fig. 2b2). In addition, at the top of the last deposited layer (Region I), a large number of equiaxed prior-β grains are observed (see Fig. 2b1). For comparative observation, the microstructures of the same location of zone ‘S’ (Region 1, Region 2, and Region 3) are shown in Fig. 2a1–a3. Also, the microstructures in the same regions are observed in the X-Z plane (Fig. 2c and d). The results show that the coarse columnar crystal structure still exists in the zone ‘S’ (see Fig. 2c), but when the last layer is deposited, fine equiaxed grains (see Fig. 2e) are formed in the zone ‘L + S’. Compared with the coarse columnar prior-β grains of zone ‘S’, the statistical distributions of the grain size and grain aspect ratio of prior-β grains formed at the last deposition layer in zone ‘L + S’ are shown in Fig. 3. The results indicate that most of the prior-β grain size of the last deposition layer is less than 200 μm, and the average grain size of the prior-β grains is 152 ± 93 μm. Moreover, the average prior-β grain aspect ratio is 1.8 ± 0.72, which shows that the prior-β grains tend to be equiaxed. In other words, in the LWAM process, the synchronous introduction of high-intensity ultrasound has a great influence on the solidification behavior of the molten pool. The generation of a large number of fine dendrites also confirms that high-intensity ultrasound can improve the nucleation rate in the molten pool and promote the fragmentation of dendrites during solidification.

Fig. 3.

Statistical distributions of the grain size (a) and grain aspect ratio (b) of prior-β grains formed at the last deposition layer in zone ‘L+S’ (see Fig. 2e).

From the microstructures of zone ‘S’ and zone ‘L + S’ in different directions (Y-Z plane and X-Z plane), it can be found that the high-intensity ultrasound has a significant effect on the growth and size of grains in the molten pool. For zone ‘S’, only the deposited Ti-6Al-4V layers (Solid) were treated by high-intensity ultrasound, and no grain refinement was found. This is probably mainly related to the following two aspects. On the one hand, the pressure of the ultrasonic vibration device acts on the deposited layer is quite small (~100 MPa), and the temperature at the place of ultrasonic action is relatively low due to the existence of an offset (20 mm). On the other hand, the Ti-6Al-4V alloy has relatively higher strength at a low temperature, such that plastic deformation occurred on the surface of the deposited layer is quite small, the grain refinement and recrystallization will not occur in this zone which is inconsistent with the reported results of large deformation [10], [11], [12]. Also, although the small plastic deformation on the surface of the deposition layer is caused by the pressure of the ultrasonic probe, this deformed zone will be remelted during the deposition of the next deposited layer. Based on the above mentioned, the grain structures of the deposited layers are not affected by this small plastic deformation. In addition, for Ti-6Al-4V alloy with high strength, the current high-intensity ultrasound does not take effect on grain refinement of the deposited zone, which means the effect of the ultrasonic vibration on the solid-state transformation of Ti-6Al-4V alloy can be neglected in the current experimental conditions. It is concluded that the interference effect of high-intensity ultrasound on the molten pool is the main reason for the microstructure refinement of LWAM assisted with ultrasonic vibration.

Present researches [13], [22] shown that the Ti-6Al-4V alloy fabricated by additive manufacturing has a strong < 0 1〉 crystallographic orientation of the prior-β grains. To further verify the refinement effect of high-intensity ultrasound on the prior-β grains, the crystallographic texture of the sample on the Y-Z plane in the zone ‘L + S’ was studied in Regions I and II. The β phase texture of the sample in the zone ‘L + S’ is presented in Fig. 4 with the form of (1 0 0)β, (1 1 0)β, and (1 1 1)β pole figures. It can be seen that the maximum texture intensity for the prior-β grains is 1.5 (close to 1) in (1 0 0)β pole figure, which means the texture belonging to the random texture. It concluded that the introduction of high-intensity ultrasound substantially weakens the texture of the prior-β phase.

Fig. 4.

Pole figures of the prior-β phase of the sample on the Y-Z plane for zone ‘L+S’.

4. Discussion

Numerous studies [[18], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28]] show that ultrasonic cavitation is the main reason for the refinement of the solidification microstructure and the fragmentation of solidification dendrites, which is the result of the interaction between sound pressure and bubbles in the molten pool. The threshold value of sound pressure for cavitation in the molten pool is [[29], [30]]:

| (1) |

where (0.101 MPa) is the liquid static pressure, (0 kPa) is the saturation vapor pressure, (1.05 N/m [13]) is the surface tension coefficient of Ti-6Al-4V alloy melt, and (10 μm) is the initial radius of the bubble. The corresponding cavitation threshold in Ti-6Al-4V alloy melt is 0.167 MPa based on Eq. (1).

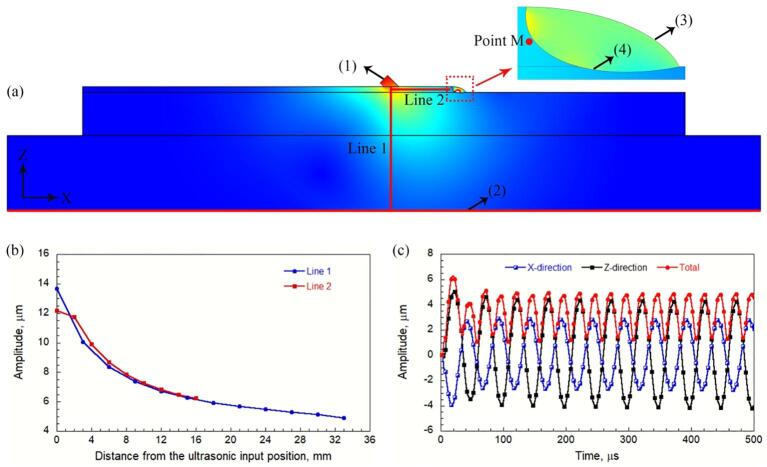

In order to investigate the effect of the ultrasonic vibration on cavitation behavior in the molten pool of Ti-6Al-4V alloy prepared by LWAM, the ultrasonic pressure distribution in the molten pool under the present experimental conditions was simulated using the COMSOL Multiphysics software with a two-dimensional (2-D) model. The offset between the ultrasonic input position and the molten pool was 20 mm, which was the same as the experimental apparatus (see Fig. 1 for details). The parts of the substrate and the deposited layers were calculated by a solid mechanics interface and the molten pool part was calculated by a pressure acoustic interface. The boundary conditions utilized in the simulation are as following (see Fig. 5):

-

(1)

Displacement load at the surface of ultrasonic input position, where is the angularfrequency, is the ultrasonic frequency of 20 kHz and is the ultrasonic input amplitude of 16 μm.

-

(2)

A Low-reflecting boundary condition was used to simulate the interface between the substrate and the experimental platform.

-

(3)

A sound soft boundary was used to simulate the interface between the molten pool and air.

-

(4)

The acoustic-structure boundary was used to couple the deposited layer and molten pool.

Fig. 5.

(a) Amplitude field distribution in the deposited layers. (b) Amplitude distribution extracted from (a) along line 1 and line 2. (c) Amplitude – Time curves at Point M.

Fig. 5a shows the amplitude field between the deposition layers and substrate and Fig. 5b shows the exponential attenuation of vibration amplitude along line 1 (vertical distance from ultrasonic input position to substrate) and line 2 (horizontal distance from ultrasonic input position to molten pool). It can be determined from line 2 that the amplitude is 12.17 μm at 1 mm below the ultrasonic input position, and rapidly decreases to 6.26 μm at 16 mm (Point M, see Fig. 5a) from the ultrasonic input position. Due to the low-reflecting boundary condition and large sample size, when the ultrasonic wave propagates to the substrate, the reflected sound wave can be neglected. Thus, the ultrasonic wave will not produce obvious interference phenomena in the deposited layers. In addition, by modifying the height of the sample in the calculation model, it was found that the amplitude of Point M does not change greatly, indicating that this synchronous loading mode can produce a stable ultrasonic effect on the molten pool. The attenuation of the ultrasonic wave is a typical diffusion attenuation, that is, the ultrasonic amplitude decreases with increasing propagation distance. Fig. 5c shows the ultrasonic amplitude near the molten pool (Point M). It can be seen that the amplitudes are 2.79 μm in the X direction and 4.35 μm in the Z direction. The ultrasonic intensity I is defined by [13]:

| (2) |

where (4208 kg/m3 [13]) is the liquid density, (4407 m/s [13]) the sound velocity in the liquid, the angular frequency, and is the amplitude. The threshold required for cavitation () in molten light metals (~100 W/cm2 [13]). Using the amplitude data (signed as Total) in Fig. 5c, the ultrasonic intensity calculated by Eq. (2) near the molten pool is plotted in Fig. 6. The ultrasonic intensity (~350 W/cm2) at the molten pool exceeds the threshold value (, the red line in Fig. 6) of acoustic cavitation, which shows the effect of grain refinement produced in the solidification process of the molten pool.

Fig. 6.

Ultrasonic intensity at Point M calculated by Eq. (2) using the amplitude data (signed as Total) in Fig. 4c.

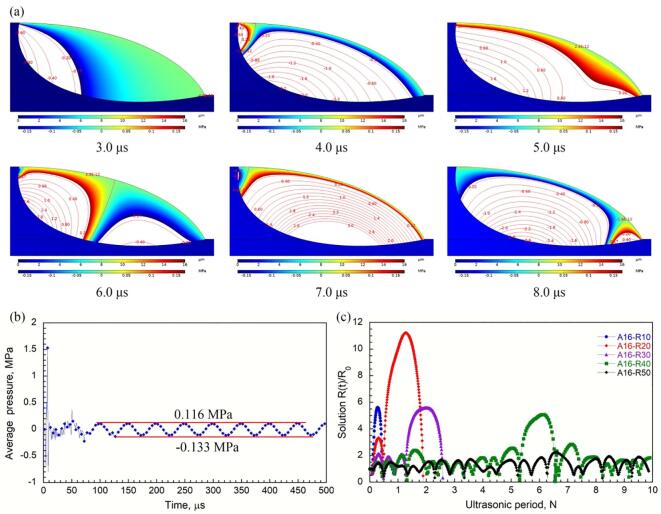

Fig. 7a shows the distribution of sound pressure in the molten pool at different times extracted from the first ultrasonic cycle . The white region with the sound pressure greater than the cavitation threshold (0.167 MPa) is the effective cavitation region in the molten pool. Fig. 7b shows the average sound pressure in ten ultrasonic periods of the whole molten pool. In the first ultrasonic period (t < T0), the sound pressure is much higher than its cavitation threshold (0.167 MPa) and the sound pressure in the molten pool is alternating between positive and negative pressure in a very short period (see Fig. 7a). To study the motion law of the microbubbles wall in the molten pool, the variations of bubble radius under the sound field calculated by the Rayleigh-Plesset equation [31], [32],:

| (3) |

where the and are the velocity and acceleration of cavitation wall, is the multilateral indices, taking 1.33, and is the viscosity of Ti-6Al-4V alloy melt, taking 0.0026 Pas. The is the sound pressure field in the molten pool, which is replaced by the data in Fig. 7b and the evolution of the bubble's wall with various initial radius R0 of 10 μm, 20 μm, 30 μm, 40 μm, and 50 μm were calculated using COMSOL Multiphysics software. Fig. 7c shows the variation of the bubble's radius within ten ultrasonic periods. Under the condition of the sound pressure field (Fig. 7b), the collapse time of bubbles with an initial bubble radius of 10 μm, 20 μm and 30 μm are 0.45 T0, 1.91 T0 and 2.57 T0, respectively. However, when the bubble radius is more than 40 μm, the variation amplitude of bubbles decreases and the bubbles did not collapse after ten ultrasonic periods. In this work, the laser beam size was 2 mm, and the melt pool size is typically about 30% larger than the laser beam size, which gives about 2.6 mm, and the laser scanning speed was 120 mm/min. Therefore, the melt pool survival time is 1.3 s in this work, which is equivalent to the time for the laser to travel across the melt pool. The survival time of the melt pool is much longer than the collapse time (about 0.00015 s, less than 3 T0) of bubbles. Hence, the melt pool survival time is sufficient for cavitation to occur in the melt pool.

Fig. 7.

(a) Sound pressure distribution in the molten pool at different times. (b) average sound pressure in the molten pool. (c) the variation of the bubble's radius at the different initial radius.

Based on the simulation results, it can be concluded that the acoustic cavitation can be produced in the molten pool under the present experimental conditions. The microbubble core will undergo the process of expansion, compression, oscillation, and finally collapse at high speed. And in the process of cavitation bubble collapse, a large temperature gradient and pressure gradient will be generated in a very small volume [23]. On the one hand, a large local temperature gradient will lead to an increase of undercooling during solidification [18]. On the other hand, the instantaneous high-intensity shock waves and strong convection will cause jet flow in the molten pool, which accelerates the flow of melt and enables the full convection of solute in the molten pool to occur [24]. The combination of the above two factors will increase the nucleation rate in the molten pool and then refine the microstructure. Also, the cavitation can induce dendrite fragmentation [23], [24], [25], [26], [27]. The influences of acoustic streaming are mainly realized through the changes of the thermal field and the solute field under melt convection [13].

The current results show that the introduction of high-intensity ultrasound can produce ultrasonic cavitation in the molten pool of the LWAM process, which can effectively prevent the epitaxial growth trend of grains and obtain refined prior-β grains. However, the effect of refinement and fragmentation of the columnar β grains is needed to improve (see Fig. 2). The exponential attenuation of ultrasound in the deposited layers is the main reason, which results in the following phenomena. Firstly, the small ultrasonic amplitude at the molten pool makes the sound intensity insufficient. The ultrasonic intensity is lower than the threshold (Ic) about one-third of the time, and it is hard to produce the so-called cavitation effect (see Fig. 6). Secondly, the sound pressure field in the molten pool tends to be stable after about two ultrasonic periods. And the average amplitude of the sound pressure is only 0.125 MPa less than 0.167 MPa (see Fig. 7b for details) which cannot produce a large range of acoustic cavitation effects in the molten pool. Thirdly, when the initial bubble radius is more than 40 μm, the variation amplitude of bubbles decreases and the bubbles do not collapse after ten ultrasonic periods (see Fig. 7c). These reasons cause the ultrasonic cavitation effect in the molten pool is not obvious. To overcome this problem, the following measures can be taken: (1) reducing the offset between the ultrasonic input point and molten pool; (2) changing its loading angle α between the ultrasonic vibration device and the deposited layer; (3) increasing the ultrasonic input amplitude A0. The finite element method was used to predict the amplitude, ultrasonic intensity, and sound pressure of the molten pool when the offset is 10 mm, the loading angle α is vertical (90°) and the ultrasonic input amplitude A0 is 30 μm. The calculated results after the molten pool are stable are listed in Table 1. It can be seen that the amplitude, sound intensity, and average sound pressure at the molten pool are greatly improved under the predicted conditions. In addition, the evolution of the bubble’s wall with different initial radius R0 in the molten pool under two different ultrasonic pressure amplitudes was calculated using Eq. (3), and the results are shown in Fig. 8. The bubbles with different initial radius are always in the state of high amplitude and nonlinear oscillation under the average sound pressure ~0.125 MPa (this work, listed in Table 1) and will not collapse in a short time (see Fig. 8a), which shows typical stable cavitation [32]. However, under the predicted condition (listed in Table 1), even if the sound pressure field of the molten pool enters the stable stage, the average amplitude of sound pressure in the molten pool is 0.39 MPa (exceeding the cavitation threshold of 0.167 MPa), which results in a large number of bubbles with an initial radius less than 100 μm collapsing in one ultrasonic period (see Fig. 8b). That is to say, the smaller the bubble, the fewer oscillations it undertakes before undergoing this violent collapse (see the illustration in Fig. 8b). Such collapses are high-energy events and can generate a wide range of potentially destructive effects, which is typical transient cavitation [32]. Thus, the results under the predicted condition indicate that a wide range of ultrasonic cavitation will occur in the molten pool as a result of improving the microstructures of alloys. The actual influence of ultrasonic cavitation on the solidification process will be further investigated in our future work.

Table 1.

Finite element simulation results under different experimental conditions.

| Experimental conditions | 20 mm-45°-16 μm (This work) | 10 mm-90°-30 μm (Predicted) |

|---|---|---|

| Amplitude, μm | 5 | 11.6 |

| Ultrasonic intensity, W/cm2 | 355 | 1987 |

| Average ultrasonic pressure amplitude, MPa | 0.125 | 0.39 |

Fig. 8.

The variation of the bubble's radius at the different initial radius under different ultrasonic pressure amplitude. (a) 0.125 MPa (this work) and (b) 0.39 MPa (predicted).

5. Conclusion

In the current work, high-intensity ultrasound was used to online treat each deposited Ti-6Al-4V alloy layer of LWAM by synchronous loading. The introduction of high-intensity ultrasound effectively interrupts the epitaxial growth trend of the dendrites, refines the microstructure of titanium alloy to a certain extent, and generates a large number of equiaxed grains in the last deposition layer. It also proves that this loading method can effectively solve the problem of coarse dendrite formation in the additive manufacturing process. Moreover, this synchronous ultrasonic energy-assisted method is unlimited by the complex shape of the components. The fine microstructure can be obtained via the optimization of processing parameters, including the offset, loading angle α, and ultrasonic input amplitude A0. This high-intensity ultrasonic online treatment for improving microstructure is also applicable for other alloy systems fabricated by additive manufacturing. In future work, the formation mechanism of equiaxed crystal, and the optimization of related parameters will be studied deeply.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Ding Yuan: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft. Shuaiqi Shao: Visualization. Chunhuan Guo: Project administration, Writing - review & editing. Fengchun Jiang: Resources, Supervision. Jiandong Wang: Visualization.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2017YFB1103701); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51671065); Equipment Development Department for Commission of Science and Technology (No. 41423030504); Applied Technology Research and Development Plan of Heilongjiang (No. GA18A403); Natural Science Fund of Heilongjiang Province (No. ZD2019E006); Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (3072020CFT1003).

Contributor Information

Chunhuan Guo, Email: guochunhuan@hrbeu.edu.cn.

Fengchun Jiang, Email: fengchunjiang@hrbeu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Wolff S.J., Lin S., Faierson E.J., Liu W.K., Wagner G.J., Cao J. A framework to link localized cooling and properties of directed energy deposition (DED)-processed Ti-6Al-4V. Acta Mater. 2017;132:106–117. doi: 10.1016/j.actamat.2017.04.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baufeld B., Van der Biest O., Gault R. Additive manufacturing of Ti-6Al-4V components by shaped metal deposition: microstructure and mechanical properties. Mater. Des. 2010;31:S106–S111. doi: 10.1016/j.matdes.2009.11.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brandl E., Palm F., Michailov V., Viehweger B., Leyens C. Mechanical properties of additive manufactured titanium (Ti-6Al-4V) blocks deposited by a solid-state laser and wire. Mater. Des. 2011;32(10):4665–4675. doi: 10.1016/j.matdes.2011.06.062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carroll B.E., Palmer T.A., Beese A.M. Anisotropic tensile behavior of Ti-6Al-4V components fabricated with directed energy deposition additive manufacturing. Acta Mater. 2015;87:309–320. doi: 10.1016/j.actamat.2014.12.054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Åkerfeldt P., Antti M.-L., Pederson R. Influence of microstructure on mechanical properties of laser metal wire-deposited Ti-6Al-4V. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 2016;674:428–437. doi: 10.1016/j.msea.2016.07.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu S.L., Qian M., Tang H.P., Yan M., Wang J., StJohn D.H. Massive transformation in Ti-6Al-4V additively manufactured by selective electron beam melting. Acta Mater. 2016;104:303–311. doi: 10.1016/j.actamat.2015.11.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu W., Brandt M., Sun S., Elambasseril J., Liu Q., Latham K., Xia K., Qian M. Additive manufacturing of strong and ductile Ti-6Al-4V by selective laser melting via in situ martensite decomposition. Acta Mater. 2015;85:74–84. doi: 10.1016/j.actamat.2014.11.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang D., Qiu D., Gibson M.A., Zheng Y., Fraser H.L., StJohn D.H., Easton M.A. Additive manufacturing of ultrafine-grained high-strength titanium alloys. Nature. 2019;576(7785):91–95. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1783-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bermingham M.J., Kent D., Zhan H., StJohn D.H., Dargusch M.S. Controlling the microstructure and properties of wire arc additive manufactured Ti-6Al-4V with trace boron additions. Acta Mater. 2015;91:289–303. doi: 10.1016/j.actamat.2015.03.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martina F., Colegrove P.A., Williams S.W., Meyer J. Microstructure of interpass rolled wire + arc additive manufacturing Ti-6Al-4V components. Metall. Mater. Trans. A. 2015;46(12):6103–6118. doi: 10.1007/s11661-015-3172-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donoghue J., Antonysamy A.A., Martina F., Colegrove P.A., Williams S.W., Prangnell P.B. The effectiveness of combining rolling deformation with Wire + arc additive manufacture on β-grain refinement and texture modification in Ti-6Al-4V. Mater. Charact. 2016;114:103–114. doi: 10.1016/j.matchar.2016.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McAndrew A.R., Alvarez Rosales M., Colegrove P.A., Hönnige J.R., Ho A., Fayolle R., Eyitayo K., Stan I., Sukrongpang P., Crochemore A., Pinter Z. Interpass rolling of Ti-6Al-4V wire + arc additively manufactured features for microstructural refinement. Addit. Manuf. 2018;21:340–349. doi: 10.1016/j.addma.2018.03.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Todaro C.J., Easton M.A., Qiu D., Zhang D., Bermingham M.J., Lui E.W., Brandt M., StJohn D.H., Qian M. Grain structure control during metal 3D printing by high-intensity ultrasound. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:142. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13874-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dai W.-L. Effects of high-intensity ultrasonic-wave emission on the weldability of aluminum alloy 7075–T6. Mater. Lett. 2003;57(16-17):2447–2454. doi: 10.1016/S0167-577X(02)01262-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang X., Kang J., Wang S., Ma J., Huang T. The effect of ultrasonic processing on solidification microstructure and heat transfer in stainless steel melt. Ultrason Sonochem. 2015;27:307–315. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2015.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yuan T., Kou S., Luo Z. Grain refining by ultrasonic stirring of the weld pool. Acta Mater. 2016;106:144–154. doi: 10.1016/j.actamat.2016.01.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen Q., Lin S., Yang C., Fan C., Ge H. Grain fragmentation in ultrasonic-assisted TIG weld of pure aluminum. Ultrason Sonochem. 2017;39:403–413. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feng X., Zhao F., Jia H., Li Y., Yang Y. Numerical simulation of non-dendritic structure formation in Mg-Al alloy solidified with ultrasonic field. Ultrason Sonochem. 2018;40:113–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tian Y., Shen J., Hu S., Wang Z., Gou J. Effects of ultrasonic vibration in the CMT process on welded joints of Al alloy. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2018;259:282–291. doi: 10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2018.05.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou S., Ma G., Dongjiang W., Chai D., Lei M. Ultrasonic vibration assisted laser welding of nickel-based alloy and Austenite stainless steel. J. Manuf. Process. 2018;31:759–767. doi: 10.1016/j.jmapro.2017.12.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fengchun Jiang, Yuanping Chen, Ding Yuan, Dacheng Hua, Chunhuan Guo, A combined ultrasonic micro-forging device for improving microstructure and mechanical properties of additive manufactured metal parts, and a related additive manufacturing method, Patent, OP2010039US.

- 22.Zhao Z., Chen J., Lu X., Tan H., Lin X., Huang W. Formation mechanism of the α variant and its influence on the tensile properties of laser solid formed Ti-6Al-4V titanium alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 2017;691:16–24. doi: 10.1016/j.msea.2017.03.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang B., Tan D., Lee T.L., Khong J.C., Wang F., Eskin D., Connolley T., Fezzaa K., Mi J. Ultrafast synchrotron X-ray imaging studies of microstructure fragmentation in solidification under ultrasound. Acta Mater. 2018;144:505–515. doi: 10.1016/j.actamat.2017.10.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang S., Guo Z.P., Zhang X.P., Zhang A., Kang J.W. On the mechanism of dendritic fragmentation by ultrasound induced cavitation. Ultrason Sonochem. 2019;51:160–165. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2018.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shu D.a., Sun B., Mi J., Grant P.S. A high-speed imaging and modeling study of dendrite fragmentation caused by ultrasonic cavitation. Metall. Mater. Trans. A. 2012;43(10):3755–3766. doi: 10.1007/s11661-012-1188-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang F., Tzanakis I., Eskin D., Mi J., Connolley T. In situ observation of ultrasonic cavitation-induced fragmentation of the primary crystals formed in Al alloys. Ultrason Sonochem. 2017;39:66–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.03.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang S., Kang J., Guo Z., Lee T.L., Zhang X., Wang Q., Deng C., Mi J. In situ high speed imaging study and modelling of the fatigue fragmentation of dendritic structures in ultrasonic fields. Acta Mater. 2019;165:388–397. doi: 10.1016/j.actamat.2018.11.053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang S., Kang J., Zhang X., Guo Z. Dendrites fragmentation induced by oscillating cavitation bubbles in ultrasound field. Ultrasonics. 2018;83:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ultras.2017.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kang J., Zhang X., Wang S., Ma J., Huang T. The comparison of ultrasonic effects in different metal melts. Ultrasonics. 2015;57:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ultras.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eskin G.I., Eskin D.G. 2nd ed. CRC Press; Boca Raton: 2014. Ultrasonic Treatment of Light Alloy Melts. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burra L., Zanolin F. Non-singular solutions of a Rayleigh-Plesset equation under a periodic pressure field. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2016;435(2):1364–1381. doi: 10.1016/j.jmaa.2015.11.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leighton T. Academic press; London: 2012. The Acoustic Bubble. [Google Scholar]