Significance

Our minds rarely stay still when left alone. Such trains of thought, however, may unfold in vastly different ways. Here, we combined electrophysiological recording with thought sampling to assess four types of thoughts: task-unrelated, freely moving, deliberately constrained, and automatically constrained. Parietal P3 was larger for task-related relative to task-unrelated thoughts, whereas frontal P3 was increased for deliberately constrained compared with unconstrained thoughts. Enhanced frontal alpha power was observed during freely moving thoughts compared with non-freely moving thoughts. Alpha-power variability was increased for task-unrelated, freely moving, and unconstrained thoughts. Our findings indicate these thought types have distinct electrophysiological signatures, suggesting that they capture the heterogeneity of our ongoing thoughts.

Keywords: task-unrelated thoughts, freely moving thoughts, constrained thoughts, mind wandering, EEG

Abstract

Humans spend much of their lives engaging with their internal train of thoughts. Traditionally, research focused on whether or not these thoughts are related to ongoing tasks, and has identified reliable and distinct behavioral and neural correlates of task-unrelated and task-related thought. A recent theoretical framework highlighted a different aspect of thinking—how it dynamically moves between topics. However, the neural correlates of such thought dynamics are unknown. The current study aimed to determine the electrophysiological signatures of these dynamics by recording electroencephalogram (EEG) while participants performed an attention task and periodically answered thought-sampling questions about whether their thoughts were 1) task-unrelated, 2) freely moving, 3) deliberately constrained, and 4) automatically constrained. We examined three EEG measures across different time windows as a function of each thought type: stimulus-evoked P3 event-related potentials and non–stimulus-evoked alpha power and variability. Parietal P3 was larger for task-related relative to task-unrelated thoughts, whereas frontal P3 was increased for deliberately constrained compared with unconstrained thoughts. Frontal electrodes showed enhanced alpha power for freely moving thoughts relative to non-freely moving thoughts. Alpha-power variability was increased for task-unrelated, freely moving, and unconstrained thoughts. Our findings indicate distinct electrophysiological patterns associated with task-unrelated and dynamic thoughts, suggesting these neural measures capture the heterogeneity of our ongoing thoughts.

Cognitive neuroscience has reached a consensus that the brain is not idle at rest (1). This rings intuitively true: When left alone, our minds rarely stay still. Moreover, recent evidence suggests that rest is not a homogeneous state (2), nor is the brain truly “at rest” as it fluctuates across time and contexts (3–6). This too is intuitive: What is striking is not just that we move from thought to thought unprompted but also the diverse ways that trains of thought unfold over time. Sometimes, our thoughts freely wander between topics. You might remember this morning’s run, then imagine gardening, then think about the dinner you’ll cook tonight. Other times, we deliberately constrain our thoughts and work diligently toward a goal. In a quiet moment, you might methodically contemplate the results of your latest experiment. Still other times, our thoughts get stuck on an affectively salient topic, from which it is difficult to break free. You might worry, over and over, about your niece who is going through major surgery next week.

Research has traditionally examined the internal train of thought in the context of mind wandering. This field has expanded at such a rapid pace that some have dubbed this the “era of the wandering mind” (7). To date, the vast majority of mind-wandering research has focused on the static content of individual thoughts. In particular, mind-wandering studies have primarily focused on task-unrelated thought (8)—that is, thoughts that are unrelated to an ongoing, typically externally oriented, task (8–10). In the laboratory, subjects’ thoughts are often unrelated to the experimental task (9). Task-unrelated thought is also frequent in everyday life (11), as when a student becomes distracted during a lecture or while driving.

Recent theories are less task-centric and instead focus on the dynamics of mind wandering—that is, how internal trains of thoughts unfold over time (12–17). In particular, the “dynamic framework” of spontaneous thought distinguishes three subtypes within the train of thoughts: 1) deliberately constrained, 2) automatically constrained, and 3) freely moving thoughts (12, 14). Constraints on the train of thoughts serve to focus internal attention on a topic for extended periods of time. For example, deliberately constrained thoughts occur when a person actively directs her thoughts to goal-relevant information (e.g., when you contemplate your latest experiment). This type of constraint is implemented through cognitive control. Automatically constrained thoughts focus on affectively or personally salient information that is difficult to disengage from (e.g., when you worry about your niece who will have surgery). This type of constraint is automatic in nature and thought to operate largely outside of cognitive control. In contrast, freely moving thoughts occur when both of these constraints are weak, allowing the mind to wander with no overarching purpose and direction (e.g., when your thoughts drift from a movie, to gardening, to dinner). Notably, the dynamic framework purports that these three subtypes of thoughts are independent of task relatedness. In other words, task-related and task-unrelated thoughts can both be deliberately constrained, automatically constrained, or freely moving. See SI Appendix for further details about the relationship between dynamic categories.

Empirical research on the dynamics of thought is in its infancy. Behavioral research has focused on contrasting task-unrelated thoughts with the other three subtypes of thoughts, with a particular emphasis on freely moving thoughts. These findings suggest that self-reported freely moving and task-unrelated thoughts have distinct behavioral markers. For example, studies of mind wandering in everyday life found that self-reports of freely moving and task-unrelated thought fluctuate at different rates throughout the day (11). Consistent with predictions of the dynamic framework, these studies reported that task-unrelated and freely moving thoughts are only modestly correlated (r < 0.3) and they occurred independent of each other (8, 11). Specifically, although task-related thoughts are often deliberately constrained and task-unrelated thoughts sometimes move freely, the dynamic framework predicts that this is not always the case. In fact, task-related thoughts can move freely (e.g., when a graphic designer freely associate ideas for her new website design) or be automatically constrained (e.g., when someone obsesses over a problem at work). Task-unrelated thoughts can be deliberately or automatically constrained (e.g., when you construct a grocery list or worry about your niece’s surgery during a lecture). The only two empirical studies to date have focused explicitly on freely moving thought (8, 11). Although this provides some initial evidence that task-unrelated thought is different from dynamic thoughts, no studies have assessed the neural correlates of dynamic thought types. The identification of different electrophysiological signatures of these thought types would thus provide important validation that these categories reflect distinct entities.

In the current study, we examined the electrophysiological signatures of the four types of thought by recording an electroencephalogram (EEG) while participants performed an attention task. Participants occasionally answered thought-sampling questions about the nature of their thoughts throughout the task. Thought sampling is the standard method in mind-wandering research: Participants are randomly interrupted as they perform a laboratory task and answer questions about their immediately preceding thoughts (9, 10). In line with previous studies, we ask the standard question about whether participants’ thoughts were task-unrelated (see ref. 8 for a review). In addition, we asked whether subjects’ trains of thought were freely moving, deliberately constrained, and automatically constrained.

We used electroencephalography because this method has the temporal resolution necessary to capture the transient changes in neural activity corresponding to our trains of thoughts, including stimulus-evoked, task-dependent activity and stimulus-independent, intrinsic activity. We first examined event-related potentials (ERPs), which index the electrophysiological response evoked by task-relevant stimuli. Previous research suggests that task-unrelated thought attenuates the magnitude of ERP components associated with sensory (18–20) and cognitive (21–24) processing of task-relevant stimuli. ERPs therefore provide an electrophysiological signature of when a participant has disengaged from task-relevant stimuli. We predicted that task-unrelated thoughts would be associated with a reduced P3 ERP component.

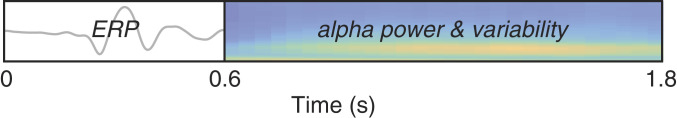

To index stimulus-independent, intrinsic neural activity, we examined spectral power in the alpha band (8 to 14 Hz) during a time window after the offset of ERPs, which is unlikely to be impacted by stimulus-evoked responses. This segregation of the poststimulus time window allowed us to disentangle stimulus-evoked, task-dependent responses captured by ERP components in the earlier window and stimulus-independent activity likely associated with the subject’s ongoing thoughts as captured by alpha power in the later time window (as illustrated in Fig. 1). Alpha-power increases recorded over posterior sites have been associated with internal attention (23, 25) as well as spontaneous brain activity recorded at rest that is not elicited by external stimuli (26, 27). In contrast, frontal alpha has been linked to creative, divergent thinking (28, 29). Accordingly, we hypothesized that task-unrelated thoughts would be associated with enhanced posterior alpha power, whereas freely moving thoughts would be associated with increased frontal alpha power. Given that our dynamic thought-sampling questions address variability within the train of thought over time, we examined the neural correlates of these thought dynamics by capturing momentary changes in alpha power (i.e., alpha-power variability) over the same ERP-free time window. We predicted that freely moving thought would be associated with increased alpha-power variability, whereas constrained thought would show reduced alpha-power variability.

Fig. 1.

EEG measures across the poststimulus time window. We examined three EEG measures. Stimulus-evoked activity as captured by P3 ERP components was examined during the 0- to 0.6-s poststimulus time window. Alpha power and variability index intrinsic neural activity not impacted by an external stimulus examined after the offset of P3s during the 0.6- to 1.8-s poststimulus time window.

Results

In a simple attention task, participants were presented with left and right arrows and asked to respond by pressing the left and right arrow keys on the keyboard, respectively. Throughout the task, thought probes were presented at the end of each block, in which participants answered several questions about their thoughts occurring within the last 10 to 15 s preceding the probe. Participants were asked to categorize their thoughts by answering the following questions: 1) Were your thoughts related to the task?; 2) were your thoughts freely moving?; 3) were your thoughts deliberately constrained?; and 4) were your thoughts automatically constrained? Participants were provided with detailed descriptions and examples of each type of thought and a training session, as described in Materials and Methods. Based on their responses, we examined how frequently each thought type occurred. We also used their responses to each thought probe to categorize the six arrow trials preceding the probe into one of the four thought types. Some trials occurred during a block characterized by task-related thoughts, for example, whereas other trials occurred during a freely moving period. All behavioral (i.e., mean accuracy, reaction time, and reaction-time variability) and ERP measures (i.e., frontal and parietal P3) were time-locked to the onset of the arrows. Alpha power and alpha-power variability were also time-locked to the same stimulus onset but examined in a later time window after the offset of the ERP response. To identify the behavioral and electrophysiological signatures of each thought type, all measures were then compared within each of the four thought types.

Attentional Results.

First, we examined the percentage of attention reports by thought types, as reported in Table 1. Subjects reported having task-unrelated thoughts more often than task-related thoughts; however, they reported freely moving thoughts about as often as thoughts that did not move freely. Further, subjects also reported more thoughts that were not deliberately or automatically constrained than constrained thoughts.

Table 1.

Percentage of attention reports by thought types

| Thought types | ||

| Task relatedness, % | Task-related: 24.5 (3.8) | Task-unrelated: 66.4 (4.2)* |

| Freely moving, % | Not free: 41.9 (3.4) | Free: 46.5 (4.1) |

| Deliberate constraints, % | Deliberate: 34.4 (3.5) | Not deliberate: 57.5 (3.9)* |

| Automatic constraints, % | Automatic: 17.0 (2.4) | Not automatic: 76.1 (2.8)* |

Mean (and SE) percentages of each condition are shown.

Indicates significant difference between thought types at P ≤ 0.001.

Second, in addition to reporting the occurrence of each thought type, we also implemented post hoc analyses to examine the extent to which they co-occur. In accordance with the dynamic model which specifically contrasts task-unrelated thoughts with the other three dynamic thought types, we correlated the occurrence of task-unrelated thoughts with freely moving thoughts and deliberately and automatically constrained thoughts within individuals. These intraindividual correlations were then tested at the group level against 0 using the sign test, a nonparametric version of the single-sample t test. Task-unrelated thoughts correlated positively with freely moving thoughts (mean ± SE = 0.51 ± 0.05; Z = 4.29, P < 0.001) and automatically constrained thoughts (mean ± SE = 0.27 ± 0.04; Z = 4.03, P < 0.001), and negatively with deliberately constrained thoughts (mean ± SE = −0.26 ± 0.07; Z = −2.91, P = 0.004).

Behavioral Results.

In order to identify the behavioral correlates of each thought type, we examined mean accuracy, reaction time, and reaction-time variability as a function of thought types. The reaction time measures are shown in Fig. 2. Mean accuracy was high across all conditions (M = 0.95, SE = 0.012). There were no significant differences in accuracy that survived the Bonferroni correction between any of the thought types, likely due to the ceiling effect in accuracy.

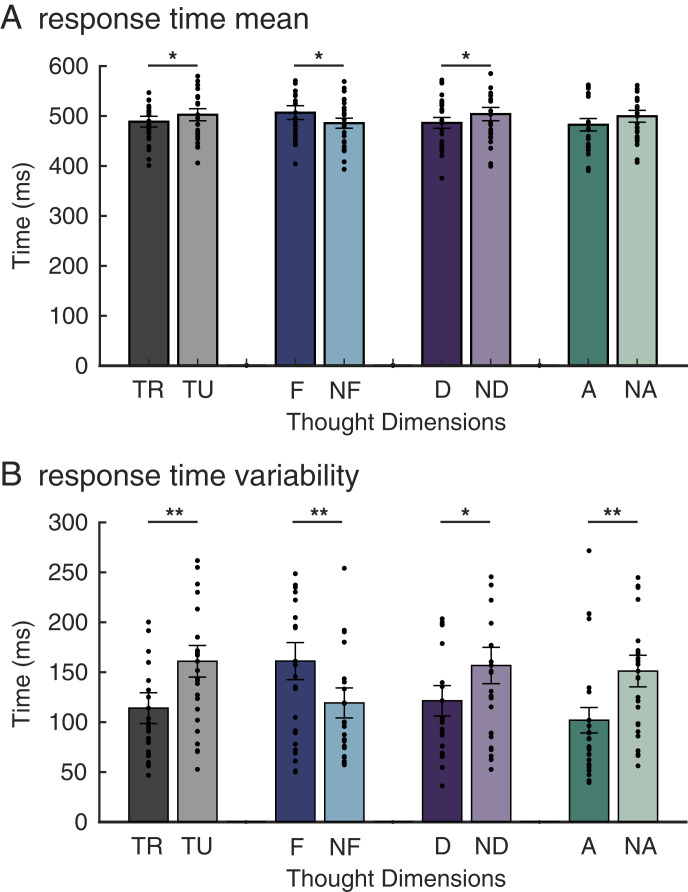

Fig. 2.

Reaction time. Mean reaction time (A) and reaction-time variability (B) are shown separately for each thought type: A, automatically constrained; D, deliberately constrained; F, freely moving; NA, not automatically constrained; ND, not deliberately constrained; NF, not freely moving; TR, task-related thought; TU, task-unrelated thought. Reaction-time variability was higher during task-unrelated thoughts, freely moving thoughts, and thoughts not automatically constrained. Error bars indicate SEM. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.0125.

Mean reaction time across conditions was 500 ms (SE = 12 ms). Reaction time was slower during task-unrelated periods than during task-related periods (P = 0.018). Freely moving periods were associated with slower reaction time than periods that were not freely moving (P = 0.013). Reaction time was faster during deliberately constrained periods relative to periods not deliberately constrained (P = 0.021). However, none of these effects survived when a Bonferroni correction was applied. No significant difference in reaction time was observed for automatically constrained thought (P = 0.069).

Reaction-time variability across conditions was 156 ms (SE = 14 ms). Increased reaction-time variability was observed during task-unrelated periods (M = 161 ms, SE = 16 ms) relative to task-related periods (M = 114 ms, SE = 16 ms; P < 0.001; Fig. 2B). There was more reaction-time variability during freely moving periods (M = 162 ms, SE = 19 ms) than during periods that were not freely moving (M = 119 ms, SE = 15 ms; P = 0.006). Decreased reaction time variability was observed during deliberately constrained periods relative to periods not deliberately constrained (P = 0.017), but the effect did not survive the Bonferroni correction. There was less reaction-time variability during automatically constrained periods (M = 102 ms, SE = 13 ms) than during periods that were not automatically constrained (M = 152 ms, SE = 16 ms; P = 0.003).

ERP Results.

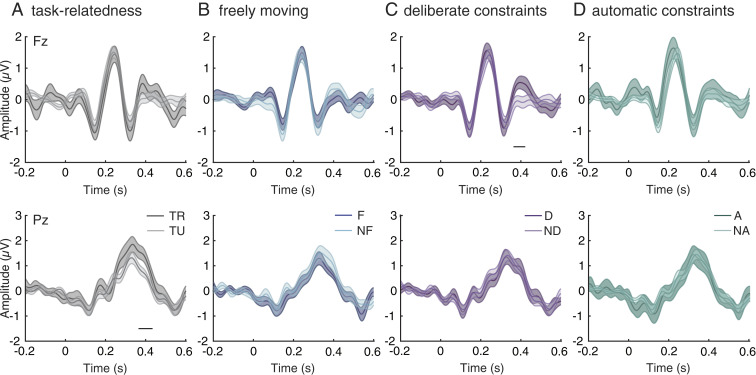

To ascertain the impact of thought types on the processing of external stimuli, we examined stimulus-evoked activity as captured by ERPs using time point-by-time point permutation tests. Fig. 3 presents the ERP waveforms at the predetermined channels relevant for the corresponding ERPs. ERP data analyses focused on the frontal P3 and parietal P3 mean amplitude measures. We statistically compared the mean amplitude for each ERP component separately for each thought type. Parietal P3 amplitudes were larger for task-related thoughts compared with task-unrelated thoughts (in the poststimulus time window of 367 to 432 ms). Frontal P3 amplitudes were larger for deliberately constrained thoughts relative to thoughts that were not deliberately constrained (in the poststimulus window of 369 to 424 ms). Both of these results remained significant after statistically controlling for other thought types, suggesting the observed patterns cannot be attributed to other thought types. Details of these post hoc control analyses are reported in SI Appendix. The remaining two thought types did not reveal significant conditional differences for either ERP component. In addition to comparisons within each thought type, we implemented post hoc analyses to compare the ERP components between task-unrelated thought and the other three thought types. Details of these analyses are also reported in SI Appendix.

Fig. 3.

Stimulus-evoked P3 event-related potentials. The ERP waveforms at frontal site Fz (Top) and parietal site Pz (Bottom) are shown separately for the following thought types: (A) task-related thoughts, (B) freely moving thoughts, (C) deliberately constrained thoughts, and (D) automatically constrained thoughts. Parietal P3 was reduced during task-unrelated thoughts, whereas frontal P3 was enhanced during deliberately constrained thoughts. Solid black lines indicate the time points of significant conditional differences. Topographic map insets are shown for the P3 during these significant time windows. TR, task-related; TU, task-unrelated; F, freely moving; NF, not freely moving; D, deliberately constrained; ND, not deliberately constrained; A, automatically constrained; NA, not automatically constrained.

Time-Frequency Power and Variability Results.

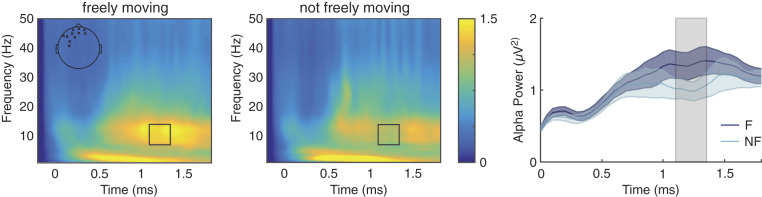

In order to determine the neural correlates of thought types independent of stimulus-evoked activity, we statistically examined spectral power in the alpha band between 600 and 1,800 ms poststimulus using cluster-based permutation tests. Fig. 4 shows the time-frequency plots for the significant thought types, along with the alpha-power time series extracted from the cluster of significant electrodes. Our analyses focused on alpha power given its role in internal attention and divergent thinking. There was a significant cluster around 1,100 to 1,350 ms over the frontal sites that showed greater alpha power during freely moving thoughts than during thoughts that were not freely moving (P = 0.023). This effect did not survive the conservative Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons, but remained significant after statistically controlling for other thought types.

Fig. 4.

Stimulus-independent alpha power. Alpha power averaged across significant electrodes emerging from a cluster-based permutation test for freely moving thought. Time-frequency representations of low-frequency power are shown (Left and Middle), with the location of the significant cluster of electrodes and black box outlining time windows of significance. Mean alpha power (shading indicates SEM) for each condition (freely moving and not freely moving) is displayed (Right), with the gray box highlighting the time window of significance. No significant clusters emerged for other thought types.

There were no significant clusters over posterior sites that differentiated alpha power between task-related and task-unrelated thoughts. Given that enhanced posterior alpha power has been consistently reported during internal attention (23, 25) and spontaneous brain activity at rest (26, 27), we implemented post hoc analysis to directly test our a priori hypothesis of increased posterior alpha during task-unrelated thought using a traditional approach with a priori electrode selection, instead of the data-driven approach of cluster-based permutation tests implemented on all electrodes. Specifically, we conducted permutation tests at the single-electrode level to examine conditional differences in posterior alpha power. The aforementioned studies converged on maximal alpha power at midline posterior site Oz for task-unrelated thought relative to task-related thought (23, 25), where alpha power is also maximal in our data (as shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S1). Accordingly, we conducted a permutation test to compare the alpha power at Oz in two time windows (600 to 1,200 and 1,200 to 1,800 ms). Posterior alpha power was increased during task-unrelated thought relative to task-related thought during the 1,200- to 1,800-ms time window (P = 0.037). There were no differences in posterior alpha during the 600- to 1,200-ms time window (P = 0.255).

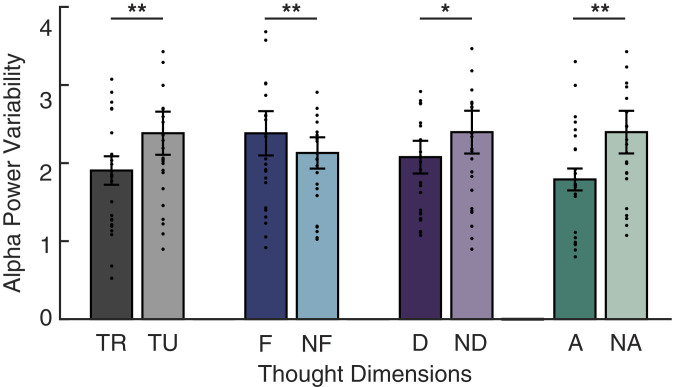

Next, we statistically examined variability in whole-brain alpha activity across time and trials between 600 and 1,800 ms using permutation tests. Fig. 5 illustrates alpha variability as a function of thought types. All four thought types showed significant differences. In particular, task-unrelated thought (P = 0.001), freely moving thought (P = 0.006), thought that was not deliberately constrained (P = 0.003), and thought that was not automatically constrained (P = 0.009) showed greater alpha variability than task-related thought, thought that was not freely moving, deliberately constrained thought, and automatically constrained thought, respectively. All these conditional differences remained significant after statistically controlling for other thought types.

Fig. 5.

Stimulus-independent alpha-power variability. Alpha-power variability across the 600- to 1,800-ms time window is shown separately for each thought type. Alpha-power variability was higher during task-unrelated thoughts, freely moving thoughts, and unconstrained thoughts. TR, task-related; TU, task-unrelated; F, freely moving; NF, not freely moving; D, deliberately constrained; ND, not deliberately constrained; A, automatically constrained; NA, not automatically constrained. Error bars indicate SEM. *P < 0.05, and **P < 0.0125.

Discussion

One of the most notable discoveries in human neuroscience in the past few decades is that the brain is active during rest (1). Early studies primarily associated this resting state with the brain’s “default network.” Yet it has become clear the brain’s intrinsic activity and connectivity are heterogeneous: They dynamically fluctuate over time (3, 4) and across contexts (5). We developed self-report questions to study the heterogeneity of our trains of thought, and established the electrophysiological signatures for four types of thought–task-unrelatedness, free movement, deliberate constraints, and automatic constraints. Our first set of results concerns stimulus-evoked activity. During task-unrelated thought, stimulus-evoked parietal P3 was attenuated relative to task-related thought. Deliberately constrained thought led to an increased stimulus-evoked frontal P3, relative to thought that lacked deliberate constraints. Our second set of results concerns stimulus-independent activity that was measured during a time window that is unlikely to be impacted by stimulus-evoked responses. This allowed us to plausibly isolate electrophysiological activity associated with a subject’s ongoing thoughts from task-relevant response. We observed that freely moving thought was linked to greater intrinsic frontal alpha power than thoughts that are not freely moving. We also observed increased variability in intrinsic alpha power during task-unrelated thought, freely moving thought, and unconstrained thoughts. Taken together, our results suggest that there are distinct neural signatures of task-unrelated and dynamic thoughts.

Freely moving thought was associated with increased frontal alpha power and alpha-power variability. Both measures were obtained during a time window unlikely to be impacted by external stimuli, which suggests that these measures reflect intrinsic activity associated with freely moving thoughts. Freely moving thought showed increased variability in alpha power. This suggests that the cognitive variability of freely moving thought parallels neural variability, particularly in the form of alpha-power fluctuations. Our results are also consistent with recent resting-state functional MRI (fMRI) findings suggesting that functional connectivity between resting-state networks fluctuates over time (4). Given that freely moving thought is conceptually independent from task-relatedness, it is unsurprising that the former did not predict differences in the magnitude of task-evoked parietal P3. Our finding that freely moving thought is associated with increased frontal alpha power should be interpreted with caution; although this was a planned comparison that remained significant after controlling for other thought types, this effect did not survive our conservative method of correction for multiple comparisons. This pattern is consistent with previous studies that have implicated frontal alpha activity in creativity (28). For example, increased frontal alpha was observed during creative idea generation (30) and in highly creative individuals relative to less creative individuals (31). Furthermore, noninvasive stimulation of frontal alpha enhanced performance on a creativity task (29). Creativity involves the generation of novel ideas and associations (28) through a divergent thought process that is theoretically similar to the free movement of thoughts going from topic to topic (12, 32). Increased frontal alpha during freely moving thought and during creativity may therefore provide a signature of relatively unconstrained thinking. Taken together, these findings suggest that the dynamic characteristics of our thoughts may be directly reflected in our electrophysiological measures.

In our study, task-unrelated thoughts reduced stimulus-evoked parietal P3. This is consistent with our prediction that task-unrelated thoughts would uniquely disrupt stimulus-evoked activity associated with task performance. This prediction flows from the decoupling model, which proposes the attenuation of external processing is necessary for supporting task-unrelated thoughts (33). In particular, task-unrelated thought recruits executive resources, which enables our disengagement from an external task via top–down control, resulting in the disruption of responses to external stimuli. Accordingly, our finding of a decreased parietal P3 evoked by visual stimuli thus validates our self-reported measure of task-unrelated thought, and is consistent with previous reports of a reduction in parietal P3 amplitude during task-unrelated thoughts (21, 22, 34).

Given that posterior alpha power has been shown to increase during cognitive states similar to task-unrelated thoughts, such as attentional lapses (23), internally oriented attention (25), or rest (26), we predicted an increase in posterior alpha power during task-unrelated thoughts. These past findings suggest that posterior alpha not only reflects top–down inhibitory control of external inputs (35) as shown in traditional studies of selective attention but also serves as an electrophysiological signature of internally oriented task-unrelated thoughts. In our study, the cluster-based permutation tests did not yield significant clusters; however, our planned post hoc analysis focusing on the posterior midline site in which alpha power is typically maximal (23) revealed increased alpha power during task-unrelated thought relative to task-related thought. Notably, task-unrelated thoughts also led to an increase in alpha-power variability. This is likely because task-related thought in the current study is highly constrained by the restrictive nature of our experimental task (i.e., the left arrow versus the right arrow), whereas thoughts unrelated to the ongoing task are not. Due to this lack of experimental constraints, task-unrelated thoughts can move to different topics and contents, which may have contributed to increased alpha-power variability.

Although there was a positive correlation between occurrence of task-unrelated thoughts and freely moving thoughts, we observed a number of differences between these two thought types. For example, task-unrelated and freely moving thoughts occurred at different rates (66 vs. 47%). Furthermore, our results revealed different electrophysiological patterns between these two thought types. Whereas task-unrelated thinking was primarily associated with changes in stimulus-evoked ERPs, freely moving thought was primarily associated with changes in intrinsic alpha power. These measures also remained significant after controlling for other thought types. Therefore, our findings indicate that task-unrelated thought and freely moving thought are uniquely characterized by a different set of electrophysiological features. These results provide support for the dynamic model, which proposed that task-unrelated and freely moving thoughts are distinct (12).

Deliberately and automatically constrained thoughts were accompanied by some overlapping patterns of electrophysiological activity and some patterns that differed. Later frontal P3 was enhanced during deliberately constrained thoughts compared with thoughts that were not deliberately constrained. Previous studies have found that cognitive control engages midline frontocentral regions (36), suggesting this enhanced frontal P3 during deliberately constrained thoughts may subserve cognitive control. This interpretation is consistent with the dynamic model’s conceptualization of deliberately constrained thoughts as goal-oriented and implemented through top–down control (12). We did not observe any differences in stimulus-evoked P3 amplitudes as a function of automatically constrained thoughts.

In terms of stimulus-independent activity, both deliberately and automatically constrained thoughts were accompanied by reduced alpha-power variability. In other words, alpha-power variability decreased for both types of constrained thought and increased for freely moving thoughts. Similarly, reaction-time variability decreased for both types of constrained thought and increased for freely moving thought. Both results support the dynamic model’s prediction that constrained thought is the opposite of freely moving thought (12). These findings suggest that variability in our cognitive states manifests in the variability of both behavioral and electrophysiological measures. Future work may explore whether other measures of neural dynamics differentiate between deliberate and automatic constraints.

The primary contribution of our paper is the identification of electrophysiological signatures of four thought types: task-unrelated, freely moving, deliberately constrained, and automatically constrained. An important question for future research is how these dynamic categories relate to task-unrelated thought. Our behavioral results provide initial evidence about the relationship between task-unrelated thought and dynamic categories. We found that occurrence of task-unrelated thought positively correlated with freely moving and automatically constrained thoughts, whereas deliberately constrained thought showed the opposite pattern. Notably, task unrelatedness did not show a one-to-one mapping with any of the dynamic categories, explaining less than 26% variance in any of these categories. These observed patterns are consistent with predictions of the dynamic framework (12) for two reasons. First, task-unrelated thoughts can be freely moving, deliberately constrained, or automatically constrained. Second, although task-related thoughts are often deliberately constrained, they can also be automatically constrained (e.g., when you obsess over a problem at work) or even freely moving (e.g., when you freely associate ideas for a new research project). Interestingly, we found that the correlation between task-unrelated and freely moving thought is stronger than in previous studies conducted in everyday life (8, 11). This may be because experimental tasks are more structured and therefore more likely to constrain free movement (37). For instance, thoughts about the arrow task in our study are less conducive to free movement; in contrast, everyday tasks are more likely to require creative idea generation, allowing for our thoughts to move freely between disparate ideas (12, 32). Future work could overcome limitations of the current study by building a larger dataset with sufficient data points per thought type, which enables examining the interactions between task-unrelated thoughts and the three subtypes of dynamic thoughts, including more fine-grained analyses such as contrasting task-unrelated thoughts that are freely moving and not freely moving.

Our methods for measuring the dynamics of thought are potentially applicable to many fields of psychology. The dynamic thought-sampling methods could be used to test theoretical links between various psychological phenomena and dynamic thought types. Clinical conditions have been hypothesized to involve high rates of freely moving (e.g., attention deficit hyperactivity disorder) or automatically constrained thought (e.g., depression and obsessive compulsive disorder) (12). Developmental psychologists have argued that children may learn better than adults in certain contexts, due to their free and associative style of thinking (38, 39). All these fields may benefit from a better understanding of, and a better ability to measure, the dynamics of thinking.

William James said that “the natural tendency of attention when left to itself is to wander to ever new things” (40). We prefer to think that attention has multiple “natural tendencies”: Sometimes it moves freely, sometimes we direct it, and sometimes it gets “stuck.” Our study shows that those thought types have distinct behavioral and electrophysiological signatures. These findings suggest that the heterogeneity of thought is reflected in the brain.

Materials and Methods

Participants.

Forty-five individuals (13 females and 32 males; M = 20.1 y, SD = 1.83) participated in the study. Three participants had missing data due to technical difficulties (with two subjects missing EEG data and one missing behavioral data). Another three participants’ EEG data files were corrupted. These six individuals were excluded from analysis, resulting in a sample of 39. All participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision and did not have neurological disorders. They provided written informed consent, and were paid for their participation. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of California, Berkeley.

Task Paradigm and Experimental Procedure.

Participants performed a simple attention task, in which they were required to press the left and right arrow keys on the keyboard when they saw left and right arrows, respectively. Both arrows were made of black solid lines and presented in a randomized order with equal probability. Each stimulus was presented for 2,000 ms, with a randomly jittered interstimulus interval between 200 and 800 ms during which a fixation cross was presented. All stimuli (i.e., arrows and fixation cross) were displayed at the center of a cathode-ray tube monitor, where participants were asked to keep their eyes fixated at all times. Stimulus presentation was controlled by E-Prime 2.0 (Psychology Software Tools). The task consisted of 840 trials, and lasted ∼40 min.

Throughout the task, thought probes were presented at the end of each block, in which participants answered several questions about their thoughts occurring within the last 10 to 15 s preceding the probe. As mentioned, some of these questions were designed to capture subtypes of thoughts proposed in the dynamic framework of spontaneous thought (12, 14). Participants were asked to categorize their thoughts by responding on a 7-point Likert scale for the following questions: 1) Were your thoughts related to the task?; 2) were your thoughts freely moving?; 3) were your thoughts deliberately constrained?; and 4) were your thoughts automatically constrained? Only the first two questions have been asked in previous studies (8, 19).

To ensure that participants understood the meaning of these questions, they completed a training session at the beginning of the experiment. We provided definitions and example scenarios of each thought type, as shown in Table 2. Following this, participants were given new example scenarios that they were likely to encounter during the experiment and asked to answer the thought probe questions based on the scenario. If they answered any questions incorrectly, experimenters would provide the correct answer and explain the reason. Experimenters proceeded to the next question only after the subjects showed full understanding of the question and correct response. One example scenario is as follows:

Table 2.

Definitions and examples of each thought type

| Thought types | Definitions and examples |

| Task unrelatedness | Definition: Thoughts unrelated to an ongoing task. |

| Example: You might think about plans for the weekend as you are completing an assignment. | |

| Freely moving | Definition: Thoughts that drift from one thing to another without focusing on anything for an extended period of time. |

| Example: You imagine yourself having dinner this evening, then wonder if you’ve been eating too much fast food recently, then notice a smudge on the computer screen, then remember that you have to do laundry tonight. | |

| Deliberately constrained | Definition: Thoughts that are focused on an overarching goal; when distracted from that goal, you bring your thoughts back on track. |

| Example: You might be actively focusing on the experimental task and ensuring that nothing else is going through your mind. | |

| Automatically constrained | Definition: Thoughts that are drawn to something and difficult to disengage from, whether or not you’re actively thinking about them. |

| Example: You might be thinking over and over again about a fight you just had with your housemate. |

While performing the attention task, a student can’t stop thinking about whether they got a good grade on their test yesterday. “Did I get question 3 wrong?” they think, picturing their answer. “What if I didn’t pass? I knew I should have studied more!!”

In this example, the student would categorize their experience as task-unrelated and automatically constrained because they cannot stop thinking about the test but neither freely moving nor deliberately constrained.

At the end of each block, participants provided a response to each of these four questions characterizing the type of thoughts they experienced in the prior 10 to 15 s. Their responses were dichotomized into two groups, separating responses on the lower end (1 to 3) and upper end (5 to 7) of the Likert scale and discarding the middle response (4). For instance, their response to the first question would be categorized as task-related (responses 1 to 3), task-unrelated (responses 5 to 7), or discarded if they responded 4 on the Likert scale. This is consistent with previous studies that also used a 7-point Likert scale for thought-sampling questions (41, 42). We used their responses to each thought probe to label the six trials (∼15 s) preceding the probe. This 15-s window was chosen for several reasons. First, this time window has been consistently used in neuroimaging studies involving experience sampling (20, 41, 43, 44). Second, theoretical frameworks have purported that attention can fluctuate at a slow timescale on the order of tens of seconds (45). This is supported by fMRI and intracranial EEG studies reporting slow fluctuations in spontaneous rest activity [<0.1 Hz (46, 47)] as well as EEG studies reporting signatures of task-unrelated thoughts are observed for up to 20 s (23). Finally, this time window allowed us to maximize the number of trials included to create a reliable average while maintaining a reasonable validity of the participants’ report. There was a total of 35 blocks, and each block consisted of 18 to 30 trials (mean = 24, equivalent to ∼1 min per block).

EEG Data Acquisition and Preprocessing.

EEG was recorded continuously from 64 active, preamplified Ag/AgCl electrodes mounted on a cap according to the extended 10-20 layout using the BioSemi ActiveTwo System. Vertical and horizontal eye movements were recorded from electrodes above and below the right eye and two electrodes placed at the right and left outer canthi. Data were amplified and digitized at 512 Hz.

EEG data were bandpass-filtered between 1 and 50 Hz, and referenced offline to the average of the two mastoid electrodes. Independent component analysis was used to correct for ocular and muscle artifacts. Data decomposition was performed using the fastICA toolbox in EEGLAB, and artifactual components were manually detected based on component time course, topography, and power spectral density. Electrodes with excessively noisy signals were interpolated from neighboring electrodes using spherical spline interpolation (48). Continuous EEG data were segmented into 4,000-ms epochs, beginning at 1,000 ms prior to stimulus onset. Each trial was visually inspected for remaining artifacts, which were removed from subsequent analyses. Common average reference was then applied to the data prior to analysis. EEG data preprocessing and analysis were performed using EEGLAB (49) and FieldTrip (50) within Matlab (MathWorks).

EEG Data Quantification.

ERP: Stimulus-evoked activity.

For stimulus-evoked activity, we examined the P3 event-related potentials in a time window immediately following stimulus onset (as shown in Fig. 1). EEG signals were bandpass-filtered at 1 to 20 Hz. Only artifact-free and correct trials were included in the analysis. These trials were averaged separately within participants as a function of their thought types: task-related versus task-unrelated, freely moving versus not freely moving, deliberately constrained versus not deliberately constrained, and automatically constrained versus not automatically constrained. All ERPs were quantified by the mean amplitude measure relative to a 200- to 0-ms prestimulus baseline. The frontal P3 mean amplitude was measured over midline frontal sites (Fz, F1, F2), whereas the parietal P3b mean amplitude was measured over midline parietal sites (Pz, P1, P2). The time window of analysis spanned from 0 to 600 ms poststimulus, which marks the offset of the stimulus-evoked response.

Alpha power: Non–stimulus-evoked activity.

To assess neural activity not influenced by stimulus-evoked responses, we examined mean spectral power as well as variability in spectral power as a function of thought types in a later time window after the offset of the stimulus-evoked response (as shown in Fig. 1). Spectral decomposition was conducted across a −1-s prestimulus to 3-s poststimulus time window for each trial, using fast Fourier transforms using a Hanning window for frequencies between 2 and 30 Hz at 1-Hz steps. Each trial was then baseline-corrected by subtracting and dividing by the average power in the prestimulus interval from −300 to −100 ms. As stimulus-evoked activity subsided ∼600 ms after stimulus presentation and the shortest trial duration is 1,800 ms, our analysis focused on 600 to 1,800 ms following stimulus presentation. Conditional differences observed in this poststimulus-evoked time window measure spontaneous activity associated with thought types that are not impacted by stimulus-evoked responses. Given the role of the alpha band in internal attention and creative thinking as previously mentioned, our analysis focused on the alpha band (8 to 14 Hz).

To examine mean spectral power, we extracted alpha power across the poststimulus-evoked activity window (600 to 1,800 ms) for all artifact-free and correct trials for each thought type. We used the cluster-based permutation test to determine whether alpha power differed within thought types and, if so, to depict the time course of these differences. This data-driven approach has the advantage of not having to presume the region or time window in which conditional differences may emerge. For each electrode, we averaged alpha power across trials yielding one time series per thought type. Each subject’s alpha-power time series for all electrodes were then submitted to a cluster-based permutation test to determine differences between thought types.

To examine variability within participants, we focused on change over time and across trials. We extracted the relative change in alpha power across the poststimulus-evoked activity window (600 to 1,800 ms) for all electrodes for each participant. In keeping with the cluster-based permutation tests that considered all electrodes, we did not restrict our analyses to focal regions and instead considered all electrodes. For each electrode, we assessed fluctuations in spectral power over the designated time window by computing the SD in alpha power across the time window for that electrode, yielding one variability value per trial. We then computed the SD of these values across trials. This variability across time and trial, averaged across electrodes, was compared between thought types.

Statistical Analyses.

Given that no experimental manipulations were placed on the subjects to facilitate specific thought types, there is a wide range of responses across individuals on each thought type. In order to implement the repeated-measures design of the experiment, all statistical analyses included only subjects who reported experiencing all four thought types, and specifically both ends of the spectrum of each thought type (i.e., task-related or task-unrelated; freely moving or not; deliberately constrained or not; automatically constrained or not). This yielded a final sample of 24 participants. This approach allowed us to examine differences across these thought types within an individual.

For attentional measures, we first conducted nonparametric pairwise comparisons to determine if occurrence rates differed within each thought type. In accordance with the dynamic model which specifically contrasts task-unrelated thoughts with the other three dynamic thought types, we also implemented post hoc analyses to examine the extent to which task-unrelated thoughts and the three subtypes of dynamic thought types co-occurred. To do so, we implemented Pearson correlations to assess the co-occurrence of task-unrelated thoughts with freely moving thoughts and deliberately and automatically constrained thoughts within individuals. These intraindividual correlations were converted to the standardized rho values and tested at the group level. To determine whether they were significantly different from 0, we used the sign test, a nonparametric version of the single-sample t test.

For behavioral measures, we focused on accuracy as well as reaction time mean and variability for accurate trials only. Each measure was compared between each of the four thought types using separate Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, the nonparametric version of the paired-samples t test. Although these are all planned comparisons, we implemented the conservative approach of Bonferroni correction on the resulting P values of these analyses to correct for multiple comparisons. Given the comparisons of four thought types in our study, the critical alpha was set to 0.05/4 = 0.0125. These analyses reflect differences in behavioral markers of different thought types.

For ERP measures, we examined differences between each of the four thought types in the amplitude of the frontal P3 and parietal P3 ERP components using the time point-by-time point permutation test. In particular, for each time point in the 0- to 600-ms poststimulus time window, trials containing the ERP waveform time series were shuffled between two conditions reflecting opposite ends of the same thought type (e.g., task-related and task-unrelated), and tested using a dependent-samples t test. Based on 1,000 random permutations, P values of the observed difference were calculated as the proportion of random permutations that yielded a larger effect than the observed experimental effect. Conditional differences were considered as significant if the P values that were below 0.05 lasted for a minimum of 50 consecutive milliseconds. This duration threshold far exceeds the minimum number of consecutive time points necessary for a time series to be considered as significantly different from 0 (51). This permutation test was performed separately for the frontal and parietal P3 ERP components. Similar to the behavioral measures, we applied the same Bonferroni-corrected critical alpha on the P3 ERP analyses. These analyses reflect the impact of engaging in certain thought types on the cognitive processing of external visual stimuli.

For mean spectral power, we submitted each subject’s alpha-power time series for all electrodes to a cluster-based permutation test to determine differences between thought types. This was identified by means of dependent-samples t tests thresholded at an alpha of 0.05. A null distribution was estimated by randomly shuffling trials 1,000 times between conditions before averaging, followed by the same clustering procedure. Using the Monte Carlo method with 1,000 random permutations, P values of the observed clusters were calculated as the proportion of random partitions that yielded a larger effect than the observed experimental effect (52). We adopted a two-tailed test, which sets critical alpha at 0.025. The cluster-based test approach corrects for the multiple comparisons of time points and electrodes. Similar to the above analyses, we applied the same Bonferroni-corrected critical alpha on the alpha-power analyses. These analyses reveal the non–stimulus-evoked spectral correlates of each thought type.

We also assessed the within-subject variability of alpha power across time and trials. In particular, we implemented permutation tests to statistically compare variability between thought types. Similar to the above analyses, variability values for artifact-free and correct trials were shuffled between two conditions (e.g., task-related and task-unrelated), and tested using a dependent-samples t test. Based on 1,000 random permutations, P values of the observed difference were calculated as the proportion of random permutations that yielded a larger effect than the observed experimental effect. We applied the same Bonferroni-corrected critical alpha above on these variability analyses. This variability measure reveals neural activity unfolding across time and trials outside of the stimulus-evoked time window. All statistical analyses were performed using Matlab.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to our participants for their time and effort in our study. We also appreciate useful feedback from Kalina Christoff, Alan Shen, and Chandra Sripada during study conceptualization. Z.C.I., C.M., and J.W.Y.K. were supported by the Templeton Foundation. J.W.Y.K. was also supported by the James McDonnell Foundation and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada. A.G. was supported by DARPA Machine Common Sense, the John Templeton Foundation, and the Bezos Foundation. R.T.K. was supported by National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grant NS21135.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2011796118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability.

Data and code reported in this article have been deposited in the Collaborative Research in Computational Neuroscience database (https://crcns.org; accession no. K0N8780K) (53).

References

- 1.Raichle M. E., et al. , A default mode of brain function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 676–682 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang H. T., et al. , Dimensions of experience: Exploring the heterogeneity of the wandering mind. Psychol. Sci. 29, 56–71 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Preti M. G., Bolton T. A., Van De Ville D., The dynamic functional connectome: State-of-the-art and perspectives. Neuroimage 160, 41–54 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gonzalez-Castillo J., et al. , The spatial structure of resting state connectivity stability on the scale of minutes. Front. Neurosci. 8, 138 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dixon M. L., et al. , Interactions between the default network and dorsal attention network vary across default subsystems, time, and cognitive states. Neuroimage 147, 632–649 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turnbull A., et al. , The ebb and flow of attention: Between-subject variation in intrinsic connectivity and cognition associated with the dynamics of ongoing experience. Neuroimage 185, 286–299 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Callard F., Smallwood J., Golchert J., Margulies D. S., The era of the wandering mind? Twenty-first century research on self-generated mental activity. Front. Psychol. 4, 891 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mills C., Raffaelli Q., Irving Z. C., Stan D., Christoff K., Is an off-task mind a freely-moving mind? Examining the relationship between different dimensions of thought. Conscious. Cogn. 58, 20–33 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smallwood J., Schooler J. W., The restless mind. Psychol. Bull. 132, 946–958 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smallwood J., Schooler J. W., The science of mind wandering: Empirically navigating the stream of consciousness. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 66, 487–518 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith G. K., Mills C., Paxton A., Christoff K., Mind-wandering rates fluctuate across the day: Evidence from an experience-sampling study. Cogn. Res. Princ. Implic. 3, 54 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christoff K., Irving Z. C., Fox K. C. R., Spreng R. N., Andrews-Hanna J. R., Mind-wandering as spontaneous thought: A dynamic framework. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 17, 718–731 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seli P., et al. , Mind-wandering as a natural kind: A family-resemblances view. Trends Cogn. Sci. 22, 479–490 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Irving Z. C., Mind-wandering is unguided attention: Accounting for the “purposeful” wanderer. Philos. Stud. 173, 547–571 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sripada C., “An exploration/exploitation tradeoff between mind wandering and task-directed thinking” in Oxford Handbook of Spontaneous Thought and Creativity, Fox K. C. R., Christoff K., Eds. (Oxford University Press, 2018), pp. 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Christoff K., Undirected thought: Neural determinants and correlates. Brain Res. 1428, 51–59 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Christoff K., et al. , The ethics of belief. Psychol. Bull. 4, 29–52 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kam J. W. Y., et al. , Slow fluctuations in attentional control of sensory cortex. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 23, 460–470 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Braboszcz C., Delorme A., Lost in thoughts: Neural markers of low alertness during mind wandering. Neuroimage 54, 3040–3047 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baird B., Smallwood J., Lutz A., Schooler J. W., The decoupled mind: Mind-wandering disrupts cortical phase-locking to perceptual events. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 26, 2596–2607 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kam J. W. Y., et al. , Mind wandering and motor control: Off-task thinking disrupts the online adjustment of behavior. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 6, 329 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smallwood J., Beach E., Schooler J. W., Handy T. C., Going AWOL in the brain: Mind wandering reduces cortical analysis of external events. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 20, 458–469 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Connell R. G., et al. , Uncovering the neural signature of lapsing attention: Electrophysiological signals predict errors up to 20 s before they occur. J. Neurosci. 29, 8604–8611 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu J., Friedman D., Metcalfe J., Attenuation of deep semantic processing during mind wandering: An event-related potential study. Neuroreport 29, 380–384 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kam J. W. Y., Solbakk A. K., Endestad T., Meling T. R., Knight R. T., Lateral prefrontal cortex lesion impairs regulation of internally and externally directed attention. Neuroimage 175, 91–99 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laufs H., et al. , EEG-correlated fMRI of human alpha activity. Neuroimage 19, 1463–1476 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laufs H., et al. , Where the BOLD signal goes when alpha EEG leaves. Neuroimage 31, 1408–1418 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fink A., Benedek M., EEG alpha power and creative ideation. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 44, 111–123 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lustenberger C., Boyle M. R., Foulser A. A., Mellin J. M., Fröhlich F., Functional role of frontal alpha oscillations in creativity. Cortex 67, 74–82 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fink A., Grabner R. H., Benedek M., Neubauer A. C., Divergent thinking training is related to frontal electroencephalogram alpha synchronization. Eur. J. Neurosci. 23, 2241–2246 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Razumnikova O. M., Creativity related cortex activity in the remote associates task. Brain Res. Bull. 73, 96–102 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manesh G., Mills C., Roseman L., Carhart-Harris R., Christoff K., Updating the dynamic framework of thought: Creativity and psychadelics. Neuroimage 213, 116726 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smallwood J., Distinguishing how from why the mind wanders: A process-occurrence framework for self-generated mental activity. Psychol. Bull. 139, 519–535 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barron E., Riby L. M., Greer J., Smallwood J., Absorbed in thought: The effect of mind wandering on the processing of relevant and irrelevant events. Psychol. Sci. 22, 596–601 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jensen O., Mazaheri A., Shaping functional architecture by oscillatory alpha activity: Gating by inhibition. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 4, 186 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cavanagh J. F., Frank M. J., Frontal theta as a mechanism for cognitive control. Trends Cogn. Sci. 18, 414–421 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Irving Z. C., Drifting and directed minds: The significance of mind-wandering for mental agency. PsyArXiv:10.31234/osf.io/3spnd (20 November 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gopnik A., et al. , Changes in cognitive flexibility and hypothesis search across human life history from childhood to adolescence to adulthood. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 7892–7899 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lucas C. G., Bridgers S., Griffiths T. L., Gopnik A., When children are better (or at least more open-minded) learners than adults: Developmental differences in learning the forms of causal relationships. Cognition 131, 284–299 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.James W., Burkhardt F., Bowers F., Skrupskelis I. K., The Principles of Psychology (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 1981). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Christoff K., Gordon A. M., Smallwood J., Smith R., Schooler J. W., Experience sampling during fMRI reveals default network and executive system contributions to mind wandering. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 8719–8724 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kirschner A., Kam J. W. Y., Handy T. C., Ward L. M., Differential synchronization in default and task-specific networks of the human brain. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 6, 139 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kam J. W. Y., Dao E., Stanciulescu M., Tildesley H., Handy T. C., Mind wandering and the adaptive control of attentional resources. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 25, 952–960 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stawarczyk D., Majerus S., Maj M., Van der Linden M., D’Argembeau A., Mind-wandering: Phenomenology and function as assessed with a novel experience sampling method. Acta Psychol. (Amst.) 136, 370–381 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sonuga-Barke E. J. S., Castellanos F. X., Spontaneous attentional fluctuations in impaired states and pathological conditions: A neurobiological hypothesis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 31, 977–986 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fransson P., Spontaneous low-frequency BOLD signal fluctuations: An fMRI investigation of the resting-state default mode of brain function hypothesis. Hum. Brain Mapp. 26, 15–29 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Foster B. L., Rangarajan V., Shirer W. R., Parvizi J., Intrinsic and task-dependent coupling of neuronal population activity in human parietal cortex. Neuron 86, 578–590 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Perrin F., Pernier J., Bertrand O., Echallier J. F., Spherical splines for scalp potential and current density mapping. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 72, 184–187 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Delorme A., Makeig S., EEGLAB: An open source toolbox for analysis of single-trial EEG dynamics including independent component analysis. J. Neurosci. Methods 134, 9–21 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oostenveld R., Fries P., Maris E., Schoffelen J. M., FieldTrip: Open source software for advanced analysis of MEG, EEG, and invasive electrophysiological data. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2011, 156869 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guthrie D., Buchwald J. S., Significance testing of difference potentials. Psychophysiology 28, 240–244 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maris E., Oostenveld R., Nonparametric statistical testing of EEG- and MEG-data. J. Neurosci. Methods 164, 177–190 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kam J., 64-channel human scalp EEG from 24 subjects examining spontaneous thought using experience sampling. Collaborative Research in Computational Neuroscience. https://crcns.org/data-sets/methods/eeg-1. Deposited 31 December, 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data and code reported in this article have been deposited in the Collaborative Research in Computational Neuroscience database (https://crcns.org; accession no. K0N8780K) (53).