Significance

Tuberculosis is the leading cause of death worldwide from a single infectious agent, but vaccines developed to date have limited efficacy and pose safety concerns. Protein-based vaccines are a safe option but usually require powerful adjuvants. We present examples of fully synthetic, self-adjuvanted protein vaccine constructs. These vaccines comprise a low-dose immune-stimulating adjuvant, covalently fused to the ESAT6 protein from Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the causative agent of tuberculosis. When administered by inhalation, the vaccines generated powerful immune responses and significant protection from M. tuberculosis in the lungs of mice. The synthetic strategy we describe represents a method that could be used to rapidly generate vaccines for preclinical testing against many diseases, including novel pathogens such as SARS-CoV-2.

Keywords: tuberculosis, mucosal vaccination, self-adjuvanting, peptide ligation, chemical protein synthesis

Abstract

The global incidence of tuberculosis remains unacceptably high, with new preventative strategies needed to reduce the burden of disease. We describe here a method for the generation of synthetic self-adjuvanted protein vaccines and demonstrate application in vaccination against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Two vaccine constructs were designed, consisting of full-length ESAT6 protein fused to the TLR2-targeting adjuvants Pam2Cys-SK4 or Pam3Cys-SK4. These were produced by chemical synthesis using a peptide ligation strategy. The synthetic self-adjuvanting vaccines generated powerful local CD4+ T cell responses against ESAT6 and provided significant protection in the lungs from virulent M. tuberculosis aerosol challenge when administered to the pulmonary mucosa of mice. The flexible synthetic platform we describe, which allows incorporation of adjuvants to multiantigenic vaccines, represents a general approach that can be applied to rapidly assess vaccination strategies in preclinical models for a range of diseases, including against novel pandemic pathogens such as SARS-CoV-2.

Vaccination is the most effective strategy for the prevention of many infectious diseases, but so far, vaccines against the major human pathogen Mycobacterium tuberculosis—the causative agent of tuberculosis (TB)—have shown limited efficacy. TB is the leading cause of death worldwide from a single infectious agent (1), resulting in 10 million new cases and 1.5 million deaths in 2018 alone, with huge socioeconomic costs globally (2). Currently, the only vaccine available for TB is Mycobacterium bovis bacille Calmette–Guérin (BCG), an attenuated Mycobacterium that stimulates immune responses against antigens shared with M. tuberculosis (3). Although BCG prevents severe disseminated forms of TB in infants and children, it fails to provide protection against infectious pulmonary disease in adolescents and adults, and has not prevented the spread of M. tuberculosis among populations (3). In addition, as a live-attenuated vaccine, BCG poses risks to immunocompromised subjects, in particular people living with HIV/AIDS (3). There is therefore an urgent need to develop new types of vaccines that provide safe and more effective protection against TB.

Protein-based subunit vaccines are one safe option, but these require adjuvants to activate pattern recognition receptors on antigen-presenting cells (APCs) that stimulate cytokine release and up-regulate cell surface expression of costimulatory molecules essential for the activation of T cells (4, 5). Alternatively, liposomal formulations have also been used to achieve an immunostimulatory effect (6, 7). The adjuvant component of vaccines can either be added as an admixture with the protein, or bound to the antigen to generate a self-adjuvanting vaccine (8, 9). Delivery as a conjugate self-adjuvanting vaccine has the advantage of direct stimulation of the APCs, which take up and process the vaccine antigen for presentation to T cells (5, 10–13). In addition, covalently bound adjuvants enhance uptake of antigens through receptor-mediated phagocytosis (14). In general, self-adjuvanting vaccines have utilized peptide antigens, and these have induced protective immunity in murine models (5, 11, 14). For example, we demonstrated that immunization with a peptide epitope from the M. tuberculosis–derived 6-kDa early secretory antigenic target (ESAT6) protein covalently bound to the palmitoyl (Pam)-containing TLR2/6 heterodimer agonist, Pam2Cys-SerLys4 (Pam2Cys-SK4), was immunogenic and protective in mice (11). However, because of the diverse human leukocyte antigen (HLA) alleles in humans, TB subunit vaccines must include multiple epitopes in order to stimulate T cell responses in the broad population; this can be achieved through the use of full-length proteins (15).

The majority of adjuvants are hydrophobic lipopeptide or glycolipid molecules. A major difficulty in generating self-adjuvanting vaccines is the fusion of an aqueous soluble protein with the hydrophobic adjuvant molecule. To address this, we have developed a robust synthetic platform by which self-adjuvanted protein vaccines can be produced in high purity and without issues associated with solubility during adjuvant conjugation. We opted for a synthetic strategy that harnessed the automation and efficiency of solid-phase peptide and lipopeptide synthesis, combined with efficient peptide ligation technologies to assemble the self-adjuvanted protein vaccines.

The route of delivery also influences the efficacy of vaccines. There is growing evidence to support the benefit of mucosal or pulmonary immunization for protection against respiratory pathogens, including M. tuberculosis (16–20), and whole-cell, viral, and peptide conjugate vaccines have been more effective when delivered to the lung (11, 21–23). This approach has been successful with an aerosol measles vaccine (24) and has been recently extended to human clinical trials for TB using aerosolized Modified Vaccinia Ankara-85A (MVA85A) (25), and an adenoviral-vectored vaccine (Ad5Ag85A; identifier: NCT02337270). Vaccination at the pulmonary mucosa generates memory CD4+ T cells that are retained in the lungs and provide an early response to M. tuberculosis exposure (11, 26). Inhalable vaccines also provide economic and practical advantages for mass immunization programs, as they can be delivered without the need for needles and trained medical personnel (17). Protein-based subunit vaccines have particular advantages for development as pulmonary vaccines; they remove the risks associated with live vaccines, are appropriate for immunocompromised individuals, and importantly are suitable for repeated use to boost immunity. In this work, we selected ESAT6 (Rv3875) as a vaccine antigen because of its promise in preclinical and clinical studies (7, 27, 28), and fused the protein to Pam2Cys or Pam3Cys, adjuvants known to be safe and effective in the lung mucosal environment (11, 29). Mucosal delivery of these self-adjuvanting vaccines to mice led to the induction of substantial Th17-type T cell responses in the lungs and significant protection against experimental M. tuberculosis infection.

Results

Design and Retrosynthesis of Self-Adjuvanting ESAT6 Vaccines.

Self-adjuvanting TB vaccines 1 and 2 were designed with Pam2Cys-SK4 and Pam3Cys-SerLys4 (Pam3Cys-SK4) adjuvants (agonists of TLR2/6 and TLR2/1 heterodimer agonists, respectively) fused via a flexible amino-triethylene glycolate linker to the N terminus of the ESAT6(1-95) protein. Pam3Cys-SK4 and Pam2Cys-SK4 were specifically selected as the adjuvant component based on the following: 1) their ability to activate APCs to produce key cytokines that promote Th1/Th17 differentiation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, and 2) their suitability for chemical conjugation, which could be performed in a modular fashion from a common ESAT6 precursor (30–32). Retrosynthetically, the lipoprotein vaccine targets were deconstructed into four approximately equal-sized fragments, with orthogonal protection allowing for assembly in the C- to N-terminal direction via sequential chemoselective peptide ligation reactions (Fig. 1). Specifically, it was envisaged that vaccines 1 and 2 could be accessed from a final one-pot native chemical ligation (NCL)–desulfurization (33, 34) reaction between ESAT6(1-16) lipopeptide thioesters 3 (bearing an N-terminal Pam2Cys-SK4) or 4 (bearing an N-terminal Pam3Cys-SK4), and a large common ESAT6(17-95) protein fragment (5) bearing an N-terminal cysteine residue. The ESAT6(17-95) protein fragment 5 was further deconstructed into three fragments; from ESAT6(17-40) thioester 6 and ESAT6(41-67) selenoester 7, both bearing N-terminal thiazolidine (Thz) residues as masked cysteines, and ESAT6(68-95) peptide diselenide dimer 8 containing an N-terminal selenocystine residue (the oxidized form of the 21st amino acid selenocysteine/Sec). We envisaged that the three fragments could be assembled via a five-step one-pot diselenide-selenoester ligation (DSL)–deselenization–thiazolidine opening–NCL–thiazolidine opening sequence (35, 36). Each of the fragments could in turn be accessed via standard fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl (Fmoc)-strategy solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS) with late-stage derivatization to install the necessary functionality at the N and/or C termini of 6–8 (37, 38).

Fig. 1.

Proposed assembly of vaccine candidates 1 and 2 via a four-fragment peptide ligation strategy.

Synthesis of Self-Adjuvanting ESAT6 Vaccines.

Synthesis of the target self-adjuvanted vaccines 1 and 2 began with the generation of functionalized peptide fragments 6–8. Each was successfully prepared by modified Fmoc-strategy SPPS methods (see SI Appendix, Supplementary Methods, for synthetic details, and SI Appendix, Figs. S1–S3 for characterization data). With fragments 6–8 in hand, these were next subjected to the one-pot C- to N-terminal ligation-based assembly of common protein fragment ESAT6(17-95) 5. The assembly began by simply dissolving peptides 7 and 8 in 6 M guanidine hydrochloride (Gdn⋅HCl), 100 mM Na2HPO4 at pH 6.5 to initiate a DSL reaction. Within 10 min, the ligation had proceeded to completion as judged by high-performance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS) analysis (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). Without purification, the DSL products were subjected to chemoselective deselenization by treatment with tris-carboxyethylphoshine (TCEP) and dithiothreitol (DTT) to convert Sec to Ala at the ligation junction. From here, in situ treatment with methoxyamine at pH 4.0 unmasked the Thz to reveal a Cys residue at the N terminus, providing ESAT6(41-95) peptide intermediate 9. At this point, ESAT6(17-40) peptide thioester 6 was introduced to the reaction with the aryl thiol additive mercaptophenylacetic acid (MPAA) and the pH adjusted to 7.2 to initiate an NCL reaction. It should be noted that the MPAA catalyst was chosen to specifically inhibit desulfurization, which may occur when Cys-bearing peptides are incubated in TCEP-containing buffer for extended periods (39). After 24 h, the NCL reaction had reached completion (as judged by HPLC-MS analysis) and methoxyamine was once again added at pH 4.0 to unmask the Thz and afford the target ESAT6(17-95) protein fragment 5 in crude form (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). Finally, purification by reverse-phase HPLC and lyophilization provided fragment 5 in 19% yield over the five-step, one-pot diselenide-selenoester ligation (DSL)–deselenization–Thz opening–NCL–Thz opening reaction sequence (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Synthesis of key ESAT617–95 protein fragment 5 via one-pot DSL–deselenization–Thz opening–NCL–Thz opening reaction sequence. Conditions: 1. DSL: 6 M Gn⋅HCl, 0.1 M Na2HPO4, pH = 6.8; 2. Deselenization: 0.25 M TCEP, 0.025 M DTT; 3. Thz opening: 0.2 M MeONH2, pH = 4.0; 4. NCL: 6 M Gn⋅HCl, 0.1 M Na2HPO4, 0.2 M MPAA, 0.25 M TCEP, pH = 7.1; 5. Thz opening: 0.2 M MeONH2, pH = 4.0.

Having successfully prepared ESAT6(17-95) protein fragment 5, the final step of the vaccine synthesis involved ligation to lipopeptide thioesters 3 and 4 that were also prepared by modified Fmoc-SPPS methods (see SI Appendix, Supplementary Methods, for synthetic details, and SI Appendix, Figs. S5 and S6 for characterization data). These final ligation reactions were carried out by dissolving lipopeptide thioesters 3 or 4 with ESAT6(17-95) peptide 5 in aqueous ligation buffer, comprising 6 M Gdn⋅HCl, 100 mM Na2HPO4, with trifluoroethanethiol (TFET) as the thiol ligation additive (Fig. 3). TFET was specifically selected as this additive permits a one-pot desulfurization reaction to be carried out following the ligation reaction owing to its poor radical quenching ability (40); this is in contrast to the more traditionally employed aryl thiol MPAA, which inhibits the subsequent radical desulfurization step and therefore usually necessitates an additional purification step. Following 24 h, the NCL reactions of common fragment 5 with either 3 or 4 had reached completion (as judged by HPLC-MS analysis). Finally, the nonnative Cys residues (Cys-17 and Cys-41) that remained from the two NCL reactions could be desulfurized to native Ala residues by in situ treatment with the water-soluble radical initiator VA-044, TCEP, and reduced glutathione at 37 °C (see SI Appendix, Supplementary Methods, for synthetic details, and SI Appendix, Figs. S7 and S8, for characterization data). After 24 h, the desulfurization had proceeded to completion at both sites and the crude reaction mixture subjected to purification via reverse-phase HPLC to afford the two target self-adjuvanting protein vaccines 1 and 2 in 36% and 25% yield, respectively, over the ligation–desulfurization steps (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Assembly of self-adjuvanting TB vaccine candidates 1 and 2 via a one-pot NCL–desulfurization protocol. Conditions: 1. NCL: 6 M Gn⋅HCl, 0.1 M Na2HPO4, 2 vol% TFET, 0.25 M TCEP, pH = 7.1; 2. Desulfurization: 6 M Gn⋅HCl, 0.1 M Na2HPO4, 0.5 M TCEP, 0.08 M reduced GSH, 0.04 M VA-044.

Self-Adjuvanted ESAT6 Vaccines Activate TLR2.

Having successfully prepared the target synthetic vaccines, we first sought to verify the adjuvant activity of the vaccine constructs by assessing TLR2 agonism using a HEK-TLR2-reporter cell line. Encouragingly, both vaccines 1 and 2 showed strong activation of TLR2, comparable to the same molar equivalent of a Pam2Cys-SK4-triethylene glycolate (and greater than a Pam3Cys-SK4-triethylene glycolate control). Notably, synthetic ESAT6 protein alone did not activate TLR2, nor did the addition of ESAT6 protein inhibit activation of TLR2 by either agonist (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

In vitro assessment of TLR2 agonism by self-adjuvanting vaccine candidates 1 and 2, determined by IL-8 release from HEK293-TLR2 reporter cells, measured by ELISA. Cells were stimulated for 16 h with PBS, ESAT6 synthetic protein, Pam2Cys-SK4-triethylene glycolate, or Pam3Cys-SK4-triethylene glycolate, in comparison to conjugate vaccines 1 and 2, using an equivalent molar concentration (7 µM = ∼10 µg/mL TLR2 ligand). Data are the means ± SEM (n = 3 technical replicates) and are representative of two independent biological replicates.

Mucosal Vaccination Induces Circulating and Local ESAT6-Specific Th17 and Antibody Responses.

Pulmonary immunization with TB vaccines has the advantages of stimulating cellular immune responses at the primary site of M. tuberculosis infection including long-lived resident memory T cells (18, 26). Therefore, the TLR2-targeted, self-adjuvanting vaccines 1 and 2 were delivered to the pulmonary mucosa of mice by intranasal (i.n.) instillation. Mice received three vaccinations at two-weekly intervals, then leukocytes from the lungs or spleen were stimulated ex vivo to identify cytokine-producing ESAT6-specific CD4+ T cells by intracellular immunostaining (ICS) and flow cytometry. In comparison to Pam2CysSK4-triethylene glycolate or ESAT6 protein-only vaccination, groups receiving 1 and 2 generated a significant proportion of lung-localized and circulating ESAT6-specific IL-17A– and TNFα-producing cells, consistent with a Th17-type response (Fig. 5A). A substantial increase in anti-ESAT6 IgG and IgA was also identified in the sera of mice receiving 1 or 2 (Fig. 5B), as well as in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF), indicating the presence of high levels of M. tuberculosis–specific antibodies at the respiratory mucosa (Fig. 5C). Assessment of peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) responses in mice prior to progression to M. tuberculosis challenge experiments showed a significant circulating Th17-type response (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5.

Mucosal immunization with vaccine candidates 1 and 2 induces local and circulating Th17-type ESAT6-specific CD4+ T cells and antibody responses. C57BL/6 mice (n = 3–4 animals per group) were immunized i.n. with 10 μg of Pam2Cys-ESAT6 vaccine 1 or Pam3Cys-ESAT6 vaccine 2, an equivalent molar amount of Pam2Cys-SK4-triethylene glycolate, or ESAT6 protein alone, three times at two-weekly intervals. At 1 wk following final immunization, (A) the frequency of antigen-specific cytokine-producing CD4+ T cells in the lungs or spleen were detected by ICS and flow cytometry following recall with ESAT61–20 in the presence of brefeldin A. Anti-ESAT6 IgG and IgA titers were determined in (B) serum and (C) BALF. Statistical significance was determined by Welch’s t test. (D) For protection studies, C57BL/6 mice (n = 6 animals per group) were immunized as per A–C, and additional mice were immunized with 5 × 105 CFU BCG once by subcutaneous injection at the time of first immunization. At 2 wk following final immunization, the frequency of antigen-specific cytokine-producing CD4+ PBMCs were detected by ICS. Data are the means ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple-comparison test to unvaccinated or Pam2Cys controls (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001).

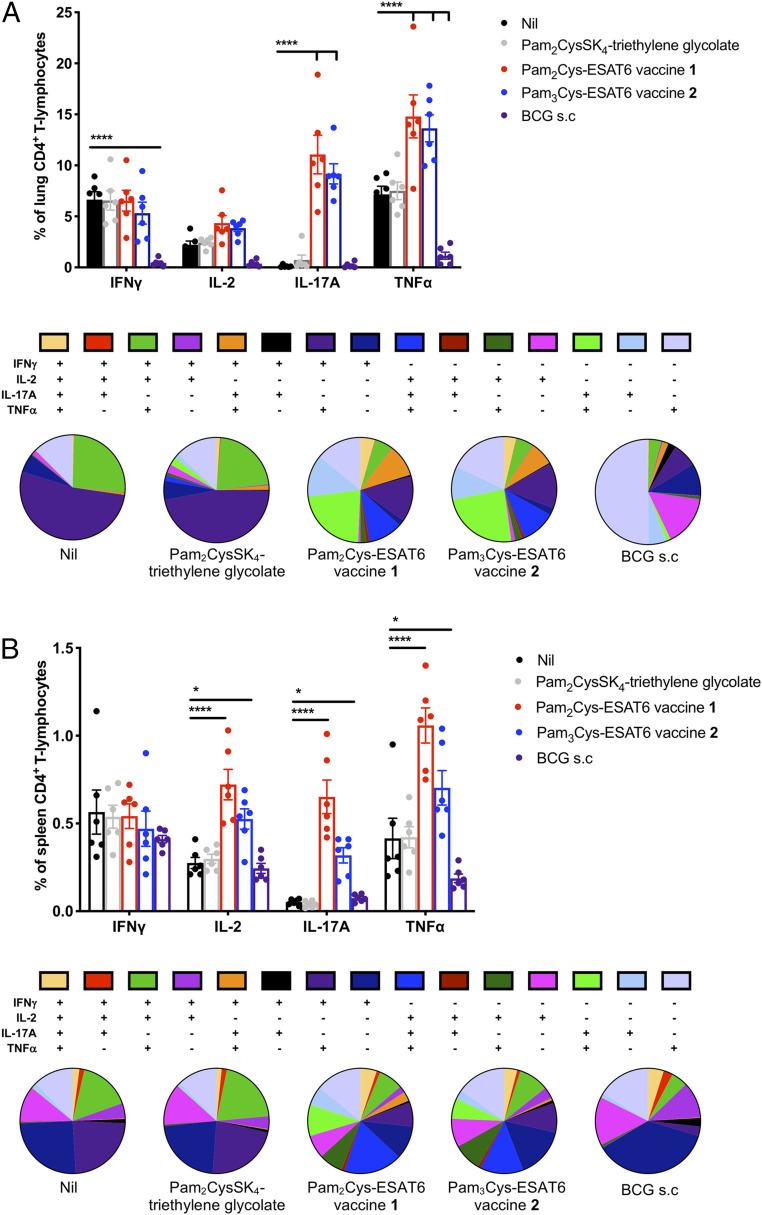

To determine whether an enhanced lung Th17 response was maintained during infection, mice received an aerosol M. tuberculosis infectious challenge 6 wk after the last vaccination. Leukocytes from the lungs and spleen were stimulated ex vivo and cytokine production assessed as before. All mice had evidence of ESAT6-specific CD4+ responses in the lungs and spleen, as is characteristic during virulent M. tuberculosis infection. Notably, 1 and 2 immunized groups had highly significant increases in populations producing IL-17A and TNFα, ∼10% and 15%, respectively, of total CD4+ T cells in the lungs (Fig. 6A), and there was also an increased proportion of polyfunctional T cells. T cells from mice in the unvaccinated and Pam2CysSK4 control groups, which showed little to no protection from M. tuberculosis, were dominated by an IFNγ response to ESAT6, including IFNγ+-, IFNγ+TNFα+-, and IFNγ+IL-2+TNFα+-producing cells. While groups vaccinated with 1 and 2 also had these populations, a greater proportion of the ESAT6-specific response was from cells that were IL-17A+, IL-17A+TNFα+, IL-2+IL-17A+TNFα+, and IFNγ+IL-17A+TNFα+, suggestive of a more varied and Th17-dominated response. In contrast, BCG-vaccinated mice had a smaller lung response that was dominated by TNFα+ and IL-2+ cells (Fig. 6A). These patterns were also seen systemically in the spleen, with mice vaccinated with 1 or 2 displaying a more varied and Th17-dominated response than control groups, although there was also a highly significant increase in IL-2–producing cells (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

Mucosal immunization with vaccine candidates 1 and 2 induces strong local and systemic Th17-type responses that are maintained postchallenge with M. tuberculosis. C57BL/6 mice (n = 6 animals per group) were immunized i.n. with 10 μg of Pam2Cys-ESAT6 vaccine 1 or Pam3Cys-ESAT6 vaccine 2, or an equivalent molar amount of Pam2Cys-SK4-triethylene glycolate, three times at two-weekly intervals. Additional mice were immunized with 5 × 105 CFU BCG once by subcutaneous injection at the time of first immunization. At 6 wk following final immunization, mice were challenged with a low-dose aerosol of M. tuberculosis H37Rv (100 CFU). Four weeks after infection, the frequency of ESAT6-specific cytokine-producing CD4+ T cells in the (A) lungs and (B) spleen were detected by ICS and flow cytometry following recall with ESAT61–20 (10 μg/mL) in the presence of brefeldin A (10 μg/mL). Data are the means ± SEM, representative of two independent experiments, shown as both the frequency of total CD4+ T lymphocytes and phenotype as a proportion of total cytokine-producing CD4+ T-cells. Statistical significance was determined by two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple-comparison test to unvaccinated control (*P < 0.05 and ****P < 0.0001).

Mucosal Vaccination with TLR2-Targeted ESAT6 Provides Protection against M. tuberculosis.

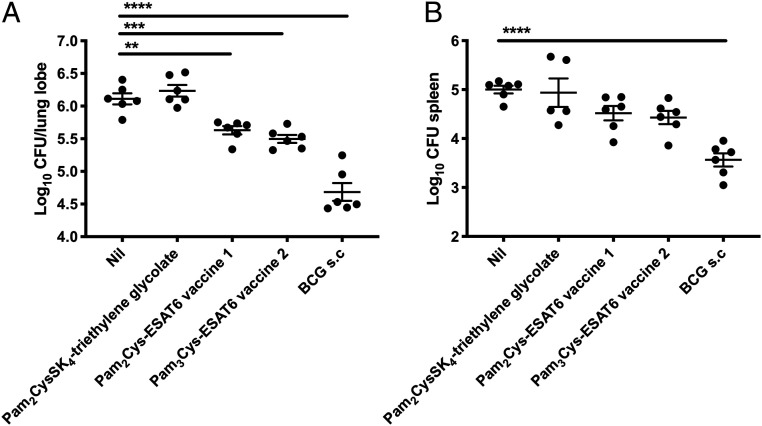

Finally, the bacterial burden was assessed in the lungs and spleen of immunized mice. Mucosal vaccination with either 1 or 2 induced a significant reduction in M. tuberculosis in the lungs in comparison to unvaccinated or adjuvant-only immunized control mice; however, this protection was not to the same extent as BCG (Fig. 7A). There was a trend toward protection in the spleen, with a Log10 0.5 reduction in both 1 and 2 vaccinated groups; however this did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 7B). BCG is used here as a reference standard for comparison in the murine M. tuberculosis challenge model and, at this time point after infection, is expected to induce significant protection (11). BCG contains multiple antigens but lacks ESAT6. However, these results confirm that ESAT6 conjugated to a TLR2-targeting adjuvant can induce protection as a single antigen.

Fig. 7.

Protective efficacy against M. tuberculosis infection was induced by mucosal immunization with vaccine candidates 1 and 2. C57BL/6 mice (n = 6 animals per group) were immunized i.n. with 10 μg of Pam2Cys-ESAT6 vaccine 1 or Pam3Cys-ESAT6 vaccine 2, or an equivalent molar amount of Pam2Cys-SK4-triethylene glycolate, three times at two-weekly intervals. Six weeks following final vaccination, mice were challenged with a low-dose aerosol of M. tuberculosis H37Rv (100 CFU). Additional mice were immunized with 5 × 105 CFU BCG once by subcutaneous injection 10 wk before challenge with M. tuberculosis H37Rv. After 28 d, mice were harvested and the bacterial loads in the lungs (A) and spleen (B) were enumerated following culture on Middlebrook 7H10 media. The data are the means ± SEM and are representative of two independent replicate experiments. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple-comparison test to unvaccinated control (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001).

Discussion

The World Health Organization END-TB strategy for TB control recognizes that a more effective vaccine approach is essential for the control of TB globally (1). This requires the development of innovative vaccines that can be safely used to boost immunity in adolescents and adults to contain the spread of M. tuberculosis. Here, we describe a synthetic method to produce highly pure, self-adjuvanted proteins suitable for pulmonary administration, and demonstrate their application in generating protective efficacy against virulent pulmonary M. tuberculosis in mice.

Fully synthetic, protein-based self-adjuvanted vaccine candidates 1 and 2 were designed in this study. Synthesis of the target vaccines was accomplished from four suitably modified peptide fragments prepared by automated Fmoc-SPPS. In order to streamline production of the two vaccines and avoid intermediary purification steps, a one-pot DSL–deselenization–Thz opening–NCL–Thz opening reaction sequence was executed to afford ESAT617–95 (5) as a common protein fragment. This fragment was then fused to lipopeptide fragments bearing either the Pam2Cys-SK4 (3) or Pam3Cys-SK4 (4) adjuvants via a one-pot NCL–desulfurization protocol. This process retained the functional activity of Pam2Cys-SK4 and Pam3Cys-SK4 ligands for the stimulation of TLR2 (Fig. 4). Moreover, when delivered as a mucosal vaccine in vivo, the constructs were capable of generating IL-17–producing CD4+ T cells specific for the ESAT6 protein, together with substantial IgG and IgA responses in the serum and lung cavity (Fig. 5). IL-17– and TNFα-producing T cells were dramatically boosted in the lungs following infection with virulent M. tuberculosis, and this response differentiated immunized from nonimmunized animals responding to M. tuberculosis (Fig. 6). Importantly, this effect was associated with protection from M. tuberculosis in the lungs (Fig. 7).

Mucosal vaccination for TB provides superior protection to peripheral immunization with virus-vectored vaccines, including Modified Vaccinia Ankara-85A (21) and Adenovirus Ad85A (23), peptide vaccines (11), and various BCG strains (41–43). This has been associated with the development and retention of lung-resident memory T cells that contribute to the early protective response (26). Although Th1-type CD4+ T cells secreting IFNγ are necessary for protection against mycobacteria, this response alone is insufficient to produce sterilizing immunity (44). Indeed, the CD4+ T cell response to ESAT6 generated by naive, unprotected mice after M. tuberculosis infection is mainly Th1, dominated by IFNγ and TNFα responses (Fig. 6). In this study, the IFNγ response appeared to reflect bacterial exposure and burden, whereas an enhanced localized Th17 lung response was strongly associated with protection against disease (Figs. 6 and 7). Although IL-17 was not essential for protection against M. tuberculosis (45, 46), pulmonary immunization with BCG and protein vaccines stimulates a strong IL-17 response (47, 48) that promotes granuloma formation and neutrophil recruitment (49), and up-regulation of CXCL10 to further recruit T cells (50). Neutralization of IL-17 abrogated the protective effect of pulmonary immunization with protein-based subunit vaccination (51) or BCG (43), indicating the importance of the Th17 response to pulmonary vaccines.

TLR2, the pattern recognition receptor activated by the lipopeptide adjuvants in our vaccines, is widely distributed in the lungs on respiratory epithelial cells, as well as on lung APCs. TLR2 stimulation of the pulmonary epithelia (52, 53) causes the release of IL-1, TNFα, and IL-6 that results in the recruitment of neutrophils and monocytes and activation of APCs. This leads to the strong Th17 response generated by mucosal delivery of the Pam2Cys-SK4 and Pam3Cys-SK4 adjuvanted vaccines (11, 54–56). Importantly, these types of vaccines would be amenable for spray drying for delivery as a dry powder, which would facilitate storage and distribution of the vaccine, as well as ease of delivery to the deep lung using dry powder inhalers (29).

Pulmonary delivery may not be necessary, or indeed the most suitable option, for all TB vaccine candidates, including live mycobacterial vaccines such as BCG (57). BCG has the advantage of inducing immune responses against multiple antigens, and despite its safety concerns in some populations, BCG will continue to be used in TB endemic areas to protect against disseminated TB in young children. Recently, BCG revaccination in adolescents showed some promise in boosting immunity against M. tuberculosis infection, rather than disease (58); however, BCG cannot be used repeatedly to boost immunity because of adverse local effects. In this context, a promising avenue for future direction would be to boost BCG with a pulmonary subunit vaccine, such as those described here, in order to enhance early and localized lung protection while maintaining the peripheral protection achieved through intradermal BCG vaccination. The inclusion of ESAT6 in these subunit vaccines, which is absent from BCG, may also provide an additive protective effect, offering a vaccination strategy that may improve protection against M. tuberculosis infection and reduce the risk of progression from latent M. tuberculosis infection to active disease.

Our approach for the development of conjugate protein vaccines has more general application outside of M. tuberculosis and could be easily adopted for the assessment of vaccines against other pathogens, or for cancer or allergy. For example, the pandemic spread of the novel SARS-CoV-2 virus has highlighted the need for new types of vaccines with characteristics that can accelerate development (59). The induction of substantial IgG and IgA responses in both the serum and at the respiratory mucosa (Fig. 5 B and C), suggests this vaccination strategy may be highly suitable for respiratory viral pathogens. While the synthetic technology described here is unlikely to be scalable to provide a practical route for mass production of vaccines, it serves as a platform to rapidly develop novel targeted vaccines for preclinical, or early-stage clinical testing. Vaccine safety is paramount for rapidly advancing vaccine candidates to human clinical trials. Importantly, the use of chemical synthesis as we have described affords high control over product purity and batch-to-batch consistency, resulting in highly pure self-adjuvanted protein vaccines that can be rapidly deployed. The synthetic assembly is suitable for rapid assessment of vaccines in multiple different animal models, with the high purity material facilitating rigorous, highly controlled assessment of vaccine-induced responses, without concerns over alteration of immune responses due to contaminating biological products such as bacterial lipopeptides (60). However, in order to then produce a similar construct for mass immunization campaigns, as would be required for TB control, a scalable route using a recombinant protein produced under good-manufacturing practices conditions would be necessary (61).

Taken together, these protein-based self-adjuvanted vaccines provide benefits for the rapid testing of vaccine candidates, including for respiratory pathogens, such as M. tuberculosis and emergent pandemic pathogens, or for noninfectious vaccine indications. The combination of TLR2-targeting and immunization by the pulmonary route shows promise as an effective vaccine strategy.

Materials and Methods

Chemical Protein Synthesis.

Automated SPPS was performed on a Biotage Initiator+ Alstra microwave peptide synthesizer. The TLR2 agonists Pam2Cys and Pam3Cys were fused to the N termini of resin-bound peptides using DIC/HOAt-mediated coupling conditions as outlined in SI Appendix, Supplementary Methods. NCL and DSL reactions were performed as outlined in SI Appendix, Supplementary Methods. In general, NCL reactions were performed in ligation buffer containing 6 M Gdn·HCl, 100 mM Na2HPO4, 50 mM TCEP, adjusted to pH 7.0 to 7.2. DSL reactions were performed in buffer containing 6 M Gdn·HCl, 100 mM Na2HPO4, adjusted to pH 6.5. After complete conversion to the desired ligated product (judged by UPLC-MS analysis) the solution(s) were diluted and purified by reversed-phase HPLC.

TLR2-Reporter Assay.

To verify TLR2 activation, a reporter cell line was utilized as previously described (11). Briefly, human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) (ATCC CRL-1573) cells transfected to express YFP-TLR2 fusion protein (62), which secrete IL-8 upon TLR activation (provided by Associate Prof. Ashley Mansell, Monash University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia), were grown at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Gibco) with d-glucose (4.5 g/L), l-glutamine (3.996 mM), geneticin (0.5 mg/mL; Gibco), and 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS) (Sigma). In total, 2 × 105 cells per well were allowed to adhere to a 96-well flat-bottom plate (Corning) and stimulated for 15 to 18 h with ∼7 µM ligand. The controls were Pam2Cys-SKKKK-triethyleneglycolate (11), Pam3Cys-SKKKK-triethyleneglycolate, and synthetic ESAT62–95 protein, used at an equivalent molar concentration. IL-8 was quantitated by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Biolegend), according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Bacterial Strains and Culture.

M. tuberculosis H37Rv (BEI Resources, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH; NR-13648) and M. bovis bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) Pasteur 1173P2 were cultured in Middlebrook 7H9 (Difco) broth supplemented with albumin-dextrose-catalase (ADC) (10% [vol/vol]), Tween 80 (0.05% [vol/vol]), and glycerol (0.2% [vol/vol]) at 37 °C. To quantitate, bacteria were grown at 37 °C on Middlebrook 7H10 or 7H11 (Difco) agar, supplemented with oleic acid–albumin–dextrose–catalase (OADC) (10% [vol/vol]) and glycerol (0.5% [vol/vol]) for up to 21 d.

Immunization of Mice.

Animal experiments were conducted in compliance with local and institutional guidelines, with approval from the Sydney Local Health District Animal Welfare Committee (protocols 2016/044 and 2020/003). Six- to eight-week-old female C57BL/6 mice were sourced from Animal BioResources and housed at the Centenary Institute under specific-pathogen–free conditions. Mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of ketamine/xylazine (50 mg/6.25 mg/kg), then vaccine in 50 µL of PBS was applied to the nares and mice were allowed to inhale the solution. Doses were as follows: 1.3 μg of Pam2Cys-SK4-triethylene glycolate for adjuvant only controls, 10 μg of synthetic ESAT62–95 for protein only controls, 12.33 μg of Pam2Cys-ESAT6 (equivalent to 10 μg of protein, 1.3 μg of Pam2Cys), 12.46 μg of Pam3Cys-ESAT6 (equivalent to 10 μg of protein, 1.5 μg of Pam3Cys). Mice were immunized three times 2 wk apart. For immunogenicity studies, bronchoalveolar lavage, lungs, spleen, and sera were collected at 1 wk after the last vaccination. For protection studies, mice were similarly vaccinated, and at 2 wk after the last immunization, peripheral blood was collected aseptically by tail vein puncture into PBS with Heparin (20 U/mL; Sigma). At 6 wk after the last vaccination, mice proceeded to M. tuberculosis aerosol challenge. Mice receiving BCG were anesthetized with gaseous isoflurane (4%) and injected at the base of tail subcutaneously once only with 5 × 105 CFU (in 200 µL of PBS), 10 wk prior to M. tuberculosis challenge.

PBMC and Organ Processing.

PBMCs were isolated by gradient density separation with Lymphoprep as per manufacturer’s instructions. For organ collection, mice were killed via CO2 asphyxiation, and tissues were removed aseptically and maintained at 4 °C. Bronchoalveolar lavage was obtained by tracheal intubation, inflation of the lung cavity with 1 mL of PBS and collection of the fluid. For lung collection, circulating blood was first removed by injection of PBS and heparin (20 U/mL; Sigma) into the right atrium of the heart. Lung tissue was diced and digested with collagenase type 4197 (50 U/mL; Sigma) and DNase I (13 µg/mL; Sigma) at 37 °C for 45 min, followed by multiple filtration steps through a 70-µm sieve. The spleens were homogenized through a 70-µm sieve and the leukocytes pelleted by centrifugation. ACK lysis buffer was used to remove erythrocytes, and leukocytes enumerated with Trypan Blue (0.04%) exclusion by hemocytometer or BD Countess. Washed cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FCS (Sigma), 2-ME (0.05 mM), and penicillin–streptomycin (100 U/mL; Gibco).

Flow Cytometry.

ESAT6-specific T cell responses were determined by antigen recall, ICS, and flow cytometry as previously described (11). Leukocytes were stimulated for 1 h (37 °C, 5% CO2) with ESAT61–20 peptide (5 to 10 µg/mL), or as controls with anti-mouse CD3 (1452C11; 5 μg/mL) and anti-mouse CD28 (37.51; 5 μg/mL; BD Pharmingen) or media alone. Brefeldin A (10 µg/mL; Sigma) was added and further incubated (4 to 16 h, 37 °C, 5% CO2) to allow cytokine accumulation. After washing in PBS, cells were incubated with live/dead fixable blue dead cell stain (Invitrogen) and Fc receptors blocked with anti-mouse CD16/CD32 (2.4G2; BD Biosciences). After washing in FACS wash (PBS with 2% FCS), surface markers were labeled with anti-mouse CD3-PECy7 (145-2C11; BD), CD4-AF700 (RM4-5; Biolegend), and CD8-APCCy7 (53-6.7; BD Pharmingen), and then cells were washed thoroughly. Cells were fixed with BD Cytofix/perm followed by thorough washing with BD Perm/Wash. Intracellular cytokines were labeled with anti-mouse IFNγ-FITC (XMG1.2; BD Pharmingen), IL-17A-PB (TC11-18H10.1; Biolegend), TNFα-PE (MP6-XT22; Biolegend), and IL-2-APC (JES6-5H4; Biolegend) prepared in BD Perm/Wash buffer and then washed. BD CompBeads were stained with the same antibody in the experimental panel, and a compensation control for the viability stain was prepared from murine leukocytes, in the same manner as experimental samples. Samples were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin prior to acquisition using an LSRFortessa or LSRII 5L flow analyzer (BD Biosciences) and analysis using FlowJo, version 10 (BD). For gating strategy, see SI Appendix, Fig. S10.

Detection of Anti-ESAT6 Antibodies.

ESAT6-specific antibody titers were determined by an indirect ELISA. Briefly, high-binding ELISA plates (Corning Falcon) were coated with synthetic ESAT62–95 protein (1 µg/mL) in carbonate/bicarbonate coating buffer (0.05 M, pH 9.6) overnight at 4 °C. After washing with PBS (POCD) plus 0.05% (vol/vol) Tween 20 (Sigma), plates were blocked with 1% (wt/vol) BSA (Bovogen) in PBS (1 h at 37 °C). A dilution series of sera (starting at 1:100) or BALF (starting at 1:20) from vaccinated mice was added (1 h at 37 °C), and then after washing, bound antibodies were detected with either goat anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen Novex) or goat anti-mouse IgA (Invitrogen), both horseradish peroxidase-conjugated. Washed ELISA plates were developed with tetramethylbenzidine substrate (Sigma), the reaction neutralized with 2 M HCl, and then absorbance read at 450 nm (570-nm reference wavelength) (Tecan Infinite M1000 PRO). The ESAT6-specific antibody titer was determined as the highest dilution above the mean absorbance (+1 SD) of 1:100 sera, or 1:20 BALF, from Pam2Cys-SK4-triethylene glycolate-immunized mice (n = 4).

M. tuberculosis Aerosol Challenge Model.

Mice were challenged with a low-dose aerosol infection (100 CFU) in an inhalation exposure system (Glas-Col). Dilutions of lung and spleen homogenates were cultured to enumerate the bacterial loads at 4 wk after exposure.

Statistics.

Statistical differences between multiple groups were determined by one or two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple-comparisons test, and were considered significant when P values were ≤0.05 (*P, 0.05; **P, 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001). Analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 8 software (GraphPad Software).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National and Medical Research Council of Australia Project Grant APP1044343 (to W.J.B. and R.J.P.), Centre for Research Excellence in Tuberculosis Control Grant APP1043225, and the New South Wales Government through its infrastructure grant to the Centenary Institute. We are grateful for the John A. Lamberton Research Scholarship (to C.C.H.) and a Research Training Scholarship (to C.C.H.). We thank Prof. J. Triccas, University of Sydney, for provision of BCG stocks; Associate Prof. B. Saunders, University of Technology Sydney, for provision of anti-mouse CD3 antibody; and Associate Prof. A. Mansell, Monash University, for provision of HEK-TLR2 reporter cell line stocks. We thank Dr. C. Counoupas, T. Wang, the Centenary Institute Animal Facility, and Sydney Cytometry for technical assistance and advice.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2013730118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability.

All study data are included in the article and SI Appendix.

References

- 1.WHO , Global Tuberculosis Report 2019 (World Health Organization, 2019). https://www.who.int/teams/global-tuberculosis-programme/tb-reports/global-report-2019. Accessed 24 December 2020.

- 2.Pai M., et al. , Tuberculosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2, 16076 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersen P., Doherty T. M., The success and failure of BCG—implications for a novel tuberculosis vaccine. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3, 656–662 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foged C., Subunit vaccines of the future: The need for safe, customized and optimized particulate delivery systems. Ther. Deliv. 2, 1057–1077 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McDonald D. M., et al. , Synthesis of a self-adjuvanting MUC1 vaccine via diselenide-selenoester ligation-deselenization. ACS Chem. Biol. 13, 3279–3285 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Dissel J. T., et al. , A novel liposomal adjuvant system, CAF01, promotes long-lived Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific T-cell responses in human. Vaccine 32, 7098–7107 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Woodworth J. S., et al. , Subunit vaccine H56/CAF01 induces a population of circulating CD4 T cells that traffic into the Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected lung. Mucosal Immunol. 10, 555–564 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bachmann M. F., Jennings G. T., Vaccine delivery: A matter of size, geometry, kinetics and molecular patterns. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 10, 787–796 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McDonald D. M., Byrne S. N., Payne R. J., Synthetic self-adjuvanting glycopeptide cancer vaccines. Front Chem. 3, 60 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson R. J., et al. , A self-adjuvanting vaccine induces cytotoxic T lymphocytes that suppress allergy. Nat. Chem. Biol. 10, 943–949 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ashhurst A. S., et al. , Mucosal vaccination with a self-adjuvanted lipopeptide is immunogenic and protective against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Med. Chem. 62, 8080–8089 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McDonald D. M., et al. , Synthesis and immunological evaluation of self-adjuvanting MUC1-macrophage activating lipopeptide 2 conjugate vaccine candidates. Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 50, 10273–10276 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeng W., Ghosh S., Lau Y. F., Brown L. E., Jackson D. C., Highly immunogenic and totally synthetic lipopeptides as self-adjuvanting immunocontraceptive vaccines. J. Immunol. 169, 4905–4912 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Azmi F., Ahmad Fuaad A. A. H., Skwarczynski M., Toth I., Recent progress in adjuvant discovery for peptide-based subunit vaccines. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 10, 778–796 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Der Meeren O., et al. , Phase 2b controlled trial of M72/AS01E vaccine to prevent tuberculosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 379, 1621–1634 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sabin A. B., Immunization against measles by aerosol. Rev. Infect. Dis. 5, 514–523 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu D., Hickey A. J., Pulmonary vaccine delivery. Exp. Rev. Vaccine 6, 213 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perdomo C., et al. , Mucosal BCG vaccination induces protective lung-resident memory T cell populations against tuberculosis. MBio 7, e01686-16 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Satti I., et al. , Safety and immunogenicity of a candidate tuberculosis vaccine MVA85A delivered by aerosol in BCG-vaccinated healthy adults: A phase 1, double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 14, 939–946 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.White A. D., et al. , Evaluation of the safety and immunogenicity of a candidate tuberculosis vaccine, MVA85A, delivered by aerosol to the lungs of macaques. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 20, 663–672 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goonetilleke N. P., et al. , Enhanced immunogenicity and protective efficacy against Mycobacterium tuberculosis of bacille Calmette-Guérin vaccine using mucosal administration and boosting with a recombinant modified vaccinia virus Ankara. J. Immunol. 171, 1602–1609 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen L., Wang J., Zganiacz A., Xing Z., Single intranasal mucosal Mycobacterium bovis BCG vaccination confers improved protection compared to subcutaneous vaccination against pulmonary tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 72, 238–246 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang J., et al. , Single mucosal, but not parenteral, immunization with recombinant adenoviral-based vaccine provides potent protection from pulmonary tuberculosis. J. Immunol. 173, 6357–6365 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.WHO , Measles Aerosol Vaccine Project: Report to SAGE (World Health Organization, 2012). https://www.who.int/immunization/sage/meetings/2012/november/3_MeaslesAerosolVaccineProject-report_SAGE.pdf. Accessed 24 December 2020.

- 25.Manjaly Thomas Z. R., et al. , Alternate aerosol and systemic immunisation with a recombinant viral vector for tuberculosis, MVA85A: A phase I randomised controlled trial. PLoS Med. 16, e1002790 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flórido M., et al. , Pulmonary immunization with a recombinant influenza A virus vaccine induces lung-resident CD4+ memory T cells that are associated with protection against tuberculosis. Mucosal Immunol. 11, 1743–1752 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Dissel J. T., et al. , Ag85B-ESAT-6 adjuvanted with IC31 promotes strong and long-lived Mycobacterium tuberculosis specific T cell responses in naïve human volunteers. Vaccine 28, 3571–3581 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aagaard C., et al. , A multistage tuberculosis vaccine that confers efficient protection before and after exposure. Nat. Med. 17, 189–194 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tyne A. S., et al. , TLR2-targeted secreted proteins from Mycobacterium tuberculosis are protective as powdered pulmonary vaccines. Vaccine 31, 4322–4329 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abdel-Aal A. B., et al. , Immune and anticancer responses elicited by fully synthetic aberrantly glycosylated MUC1 tripartite vaccines modified by a TLR2 or TLR9 agonist. ChemBioChem 15, 1508–1513 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Batzloff M. R., Hartas J., Zeng W., Jackson D. C., Good M. F., Intranasal vaccination with a lipopeptide containing a conformationally constrained conserved minimal peptide, a universal T cell epitope, and a self-adjuvanting lipid protects mice from group A streptococcus challenge and reduces throat colonization. J. Infect. Dis. 194, 325–330 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bettahi I., et al. , Antitumor activity of a self-adjuvanting glyco-lipopeptide vaccine bearing B cell, CD4+ and CD8+ T cell epitopes. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 58, 187–200 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dawson P. E., Muir T. W., Clark-Lewis I., Kent S. B., Synthesis of proteins by native chemical ligation. Science 266, 776–779 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kulkarni S. S., Sayers J., Premdjee B., Payne R. J., Rapid and efficient protein synthesis through expansion of the native chemical ligation concept. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2, 0122 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kulkarni S. S., Watson E. E., Premdjee B., Conde-Frieboes K. W., Payne R. J., Diselenide-selenoester ligation for chemical protein synthesis. Nat. Protoc. 14, 2229–2257 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mitchell N. J., et al. , Rapid additive-free selenocystine-selenoester peptide ligation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 14011–14014 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ficht S., Payne R. J., Guy R. T., Wong C.-H., Solid-phase synthesis of peptide and glycopeptide thioesters through side-chain-anchoring strategies. Chemistry 14, 3620–3629 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hanna C. C., Kulkarni S. S., Watson E. E., Premdjee B., Payne R. J., Solid-phase synthesis of peptide selenoesters via a side-chain anchoring strategy. Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 53, 5424–5427 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moyal T., Hemantha H. P., Siman P., Refua M., Brik A., Highly efficient one-pot ligation and desulfurization. Chem. Sci. (Camb.) 4, 2496–2501 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thompson R. E., et al. , Trifluoroethanethiol: An additive for efficient one-pot peptide ligation-desulfurization chemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 8161–8164 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dijkman K., et al. , Prevention of tuberculosis infection and disease by local BCG in repeatedly exposed rhesus macaques. Nat. Med. 25, 255–262 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nambiar J. K., Ryan A. A., Kong C. U., Britton W. J., Triccas J. A., Modulation of pulmonary DC function by vaccine-encoded GM-CSF enhances protective immunity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Eur. J. Immunol. 40, 153–161 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aguilo N., et al. , Pulmonary but not subcutaneous delivery of BCG vaccine confers protection to tuberculosis-susceptible mice by an interleukin 17–dependent mechanism. J. Infect. Dis. 213, 831–839 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Counoupas C., Triccas J. A., Britton W. J., Deciphering protective immunity against tuberculosis: Implications for vaccine development. Expert Rev. Vaccines 18, 353–364 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cooper A. M., Editorial: Be careful what you ask for: Is the presence of IL-17 indicative of immunity? J. Leukoc. Biol. 88, 221–223 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Uranga S., Marinova D., Martin C., Aguilo N., Protective efficacy and pulmonary immune response following subcutaneous and intranasal BCG administration in mice. J. Vis. Exp. 115, e54440 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zygmunt B. M., Rharbaoui F., Groebe L., Guzman C. A., Intranasal immunization promotes Th17 immune responses. J. Immunol. 183, 6933–6938 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Orr M. T., et al. , Mucosal delivery switches the response to an adjuvanted tuberculosis vaccine from systemic TH1 to tissue-resident TH17 responses without impacting the protective efficacy. Vaccine 33, 6570–6578 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Okamoto Yoshida Y., et al. , Essential role of IL-17A in the formation of a mycobacterial infection-induced granuloma in the lung. J. Immunol. 184, 4414–4422 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Khader S. A., et al. , IL-23 and IL-17 in the establishment of protective pulmonary CD4+ T cell responses after vaccination and during Mycobacterium tuberculosis challenge. Nat. Immunol. 8, 369–377 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Counoupas C., et al. , Mucosal delivery of a multistage subunit vaccine promotes development of lung-resident memory T cells and affords interleukin-17-dependent protection against pulmonary tuberculosis.NPJ Vaccines 5, 105 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oliveira-Nascimento L., Massari P., Wetzler L. M., The role of TLR2 in infection and immunity. Front. Immunol. 3, 79 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Andersson M., et al. , Mycobacterium bovis bacilli Calmette-Guerin regulates leukocyte recruitment by modulating alveolar inflammatory responses. Innate Immun. 18, 531–540 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ashhurst A. S., et al. , PLGA particulate subunit tuberculosis vaccines promote humoral and Th17 responses but do not enhance control of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. PLoS One 13, e0194620 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ahmed M., et al. , Rationalized design of a mucosal vaccine protects against Mycobacterium tuberculosis challenge in mice. J. Leukoc. Biol. 101, 1373–1381 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stewart E., Triccas J. A., Petrovsky N., Adjuvant strategies for more effective tuberculosis vaccine immunity. Microorganisms 7, 255 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Darrah P. A., et al. , Prevention of tuberculosis in macaques after intravenous BCG immunization. Nature 577, 95–102 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nemes E. et al.; C-040-404 Study Team , Prevention of M. tuberculosis infection with H4:IC31 vaccine or BCG revaccination. N. Engl. J. Med. 379, 138–149 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Amanat F., Krammer F., SARS-CoV-2 vaccines: Status report. Immunity 52, 583–589 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kesik-Brodacka M., Progress in biopharmaceutical development. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 65, 306–322 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Luo Y., et al. , The dual role of lipids of the lipoproteins in Trumenba, a self-adjuvanting vaccine against meningococcal meningitis B disease. AAPS J. 18, 1562–1575 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Latz E., et al. , Lipopolysaccharide rapidly traffics to and from the Golgi apparatus with the Toll-like receptor 4-MD-2-CD14 complex in a process that is distinct from the initiation of signal transduction. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 47834–47843 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and SI Appendix.