Summary

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) play key roles in transporting key molecular constituents as cargo for extracellular trafficking. While several approaches have been developed to extract EVs from mammalian cells, the specific method of EV isolation can have a profound effect on membrane integrity and yield. Here, we describe a step-by-step procedure to separate EVs from adherent epithelial cells using differential ultracentrifugation. Separated EVs can be further analyzed by immunoblotting, mass spectrometry, and transmission electron microscopy to derive EV yield and morphology.

For complete details on the use and execution of this protocol, please refer to Brown et al. (2019).

Subject areas: Cell biology, Cell culture, Cell membrane, Cancer

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Description of EV separation from cell culture models using ultracentrifugation

-

•

Determination of EV yield and morphology by immunoblotting and TEM

-

•

Assessment of EV-specific biomarkers to determine EV enrichment

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) play key roles in transporting key molecular constituents as cargo for extracellular trafficking. While several approaches have been developed to extract EVs from mammalian cells, the specific method of EV isolation can have a profound effect on membrane integrity and yield. Here, we describe a step-by-step procedure to separate EVs from adherent epithelial cells using differential ultracentrifugation. Separated EVs can be further analyzed by immunoblotting, mass spectrometry, and transmission electron microscopy to derive EV yield and morphology.

Before you begin

Preparation of extracellular vesicle (EV)-free serum

Timing: ~1 day

-

1.

Centrifuge serum using SW 32.1 Ti Swinging-Bucket rotor (k-factor = 204) in Optima XPN-80 Ultracentrifuge at 22,000 rpm for 140 min at 4°C.

-

2.

Sterilize the serum using a 0.22 μm syringe filter.

Note: Steps 1 and 2, serum centrifugation and filter sterilization respectively, are interchangeable.

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| ALIX, mouse monoclonal | Abcam | Cat#ab117600; RRID: AB_10899268 |

| CD9, mouse monoclonal | Novus Biologicals | Cat#NBP2-22187; RRID: AB_1853147 |

| CD63, rabbit monoclonal | Abcam | Cat#ab217345; RRID: AB_2754982 |

| GM130, rabbit monoclonal | Abcam | Cat#ab52649; RRID: AB_880266 |

| TSG-101, mouse monoclonal | Genetex | Cat#GTX70255; Clone: 4A10; Lot 43353; RRID: AB_373239 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| RSL3 | SelleckChem | Cat#S8155 |

| DMSO | Fisher Scientific | Cat#BP231 |

| Experimental models: cell lines | ||

| Human normal mammary epithelial, MCF10A | Barbara Ann Karmanos Cancer Center | N/A |

| Human triple negative breast carcinoma, Hs578T | Laboratory of Dr. Dohoon Kim, PhD (University of Massachusetts Medical School) | N/A |

| Other | ||

| Centrifuge 5810 R | Eppendorf | Cat#022625101 |

| DMEM high glucose medium | Gibco | Cat#11965118 |

| DMEM/F:12 medium | Gibco | Cat#11320082 |

| Cholera toxin | MilliporeSigma | Cat#C8052 |

| EGF | Peprotech | Cat#AF-100-15 |

| Horse serum, New Zealand origin | Gibco | Cat#16050 |

| HyClone calf serum, US origin | GE | Cat#SH30073 |

| Hydrocortisone | MilliporeSigma | Cat#H4001 |

| Insulin | MilliporeSigma | Cat#I5500 |

| Open-top Thinwall ultra-clear tubes, 25 × 89 mm | Beckman Coulter | Cat#344058 |

| Optima XPN-80 ultracentrifuge | Beckman Coulter | Cat#A99839 |

| Penicillin-streptomycin (10,000 U/mL) | Gibco | Cat#15140122 |

| PVDF syringe filter, 0.22 μm, 30 mm | CellTreat | Cat#229743 |

| Rotor A-4-62, incl. 4 × 250 mL rectangular buckets | Eppendorf | Cat#022638009 |

| SW 32.1 Ti swinging-bucket rotor and SW 32 Ti rotor bucket set (k-factor = 204) | Beckman Coulter | Cat#369651 |

| TUBE & CAP, 50 mL centrifuge tube and cap | CellTreat | Cat#229421 |

| 0.5% Trypsin-EDTA (10×) | Gibco | Cat#15400-54 |

| 500 mL filter system, 0.22 μm PES filter, 90 mm diameter, sterile | CellTreat | Cat#229707 |

Materials and equipment

Here, we describe the media components used to culture Hs578t and MCF10A cell lines.

MCF10A media

| Reagent | Stock concentration | Final concentration | Amount |

|---|---|---|---|

| DMEM/F:12 medium | N/A | N/A | 500 mL |

| Horse serum | N/A | 5% | 25 mL |

| EGF | 100 μg/mL | 20 ng/mL | 100 μL |

| Hydrocortisone | 1 mg/mL | 0.5 mg/mL | 250 μL |

| Cholera toxin | 1 mg/mL | 100 ng/mL | 50 μL |

| Insulin | 10 mg/mL | 10 μg/mL | 500 μL |

| Penicillin/streptomycin | 10,000 U/mL | 100 U/mL | 5 mL |

Note: Premix all of the appropriate MCF10A media additives listed above and sterile filter mixture through a 0.22 μm filter system (Figure 1A).

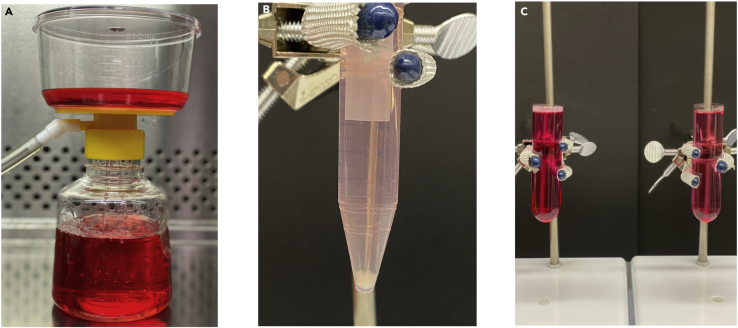

Figure 1.

Extracellular vesicle separation by ultracentrifugation step-by-step method overview

(A) Media filter sterilization (0.22 μm filter) for subculturing cells.

(B) MCF10A cell pellet after centrifugation at 3,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C.

(C) Two ultracentrifugation tubes balanced with media and using cold PBS as necessary. Ultracentrifuge tubes are filled to avoid collapse as a result of insufficient volume.

CRITICAL: Insulin should be adjusted to pH 3 when added to MCF10A media as insulin has low solubility at a neutral pH. We suggest resuspending insulin at 10 mg/mL in sterile H2O and add either dilute acetic or hydrochloric acid until pH 3.

Hs578t media

| Reagent | Stock concentration | Final concentration | Amount |

|---|---|---|---|

| DMEM high glucose medium | N/A | N/A | 500 mL |

| FBS | N/A | 5% | 25 mL |

| Insulin | 2.5 mg/mL | 1% | 2 mL |

| Penicillin/streptomycin | 10,000 U/mL | 100 U/mL | 5 mL |

CRITICAL: It is important to use EV-free serum (e.g., EV-free FBS for Hs578t cells or EV-free horse serum for MCF10A cells) when preparing media in place of serum as specified above. Serum contains EVs, which will contaminate cell-derived EVs, and may alter downstream readouts (Pavani et al., 2019; Shelke et al., 2014). Extracellular proteins and RNA present in serum may also co-separate with cell-derived EVs and have significant biological effects on the cell (Wei et al., 2016).

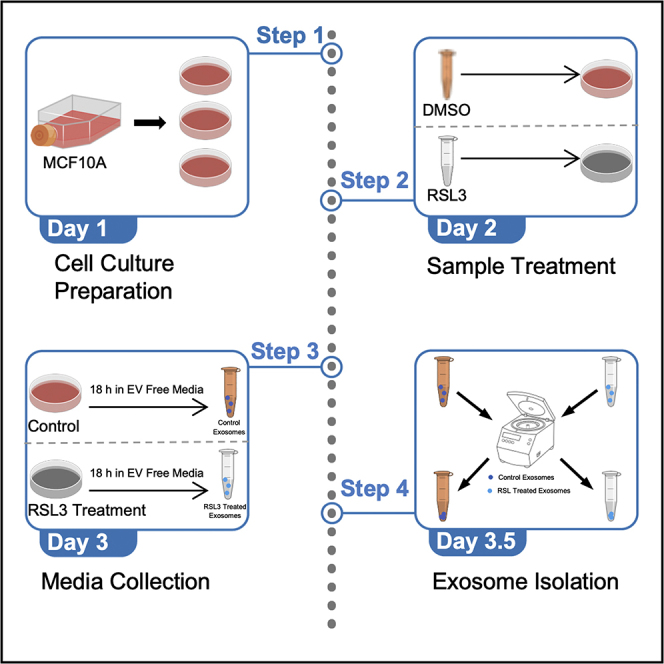

Step-by-step method details

This protocol is aimed at isolating EVs from adherent epithelial cells in cell culture models. The protocol can be adapted depending on the treatment and desire for further characterization including morphological analysis, immunoblotting, mass spectrometry, and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Cells are treated, prepared, and cell culture media is collected (1) using standard procedures. Centrifugation of the collected cell culture media (2) separates EVs from other extracellular materials (Livshits et al., 2015), while differential ultracentrifugation further enriches and concentrates the EV sample (Yu et al., 2018).

Note: The protocol shown below is described step by step, performed with MCF10A cells treated with 2.5 μM RSL3 for 18 h, though this protocol may be adapted to other treatments.

Cell culture preparation

Timing: ~1 day

Here, we will be culturing MCF10A cells. Total number of plates will depend on the downstream applications and desired yield. Given the limited concentration of EVs separated from cell culture media, we suggest starting with 6–150 × 20 mm TC-treated dishes. This procedure aims to prepare cells for collection after treatment. Cells are treated with 2.5 μM RSL3 and cell culture media is collected for EV isolation in the following section.

-

1.

Subculture MCF10A cells. Plate ~750,000 cells in 100 × 20 mm TC-treated dishes. Keep them in a DMEM/F:12 media consisting of 5% EV-free horse serum, EGF (Final Concentration: 20 ng/mL), hydrocortisone (Final Concentration: 0.5 mg/mL), Cholera Toxin (Final Concentration: 100 ng/mL), insulin (Final Concentration: 10 ug/mL), and 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin.

Note: The number of MCF10A plates is restricted only by the volume limited by the ultracentrifugation rotors and tubes. More plates may allow for a greater quantity of separated EVs. This protocol can be adapted to other cell lines such as the Hs578t cells.

Sample treatment and media collection

Timing: ~1 day

This procedure aims to prepare cells for collection after treatment. Cells are treated with RSL3. Cell culture media is collected for EV isolation in the following section.

-

2.

Remove media from cells.

Note: We suggest 80%–90% cell confluency at which point media is collected for EV isolation. Confluency can be adjusted differently depending on the purpose of the experiment; however, we do not recommend less than 50% cell confluency as this will greatly affect the overall EV yield/enrichment.

-

3.

Treat cells with 2.5 μM RSL3 for 18 h in EV-free media.

-

4.

Collect cell culture media and transfer into 50 mL conical tubes.

CRITICAL: Following cell culture media collection, it is necessary to keep samples on ice at all times to avoid EV degradation (Cheng et al., 2019).

EV isolation

Timing: 5–6 h

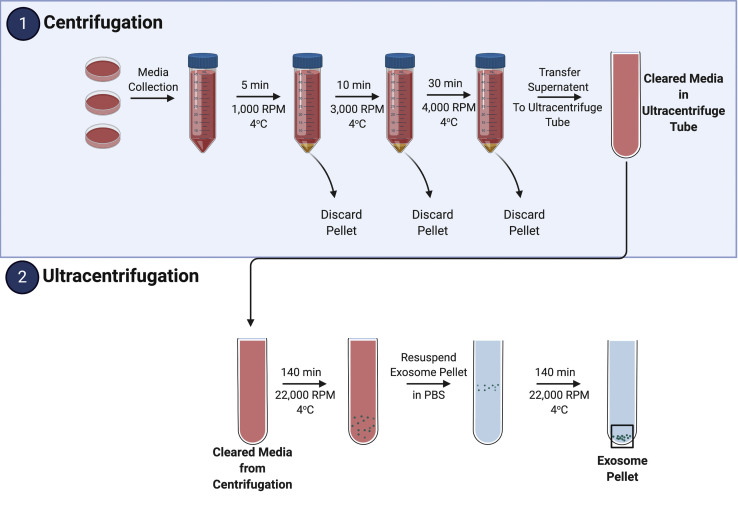

Here, differential centrifugation and ultracentrifugation are utilized to separate EVs from cell components (e.g., cells, cell debris, and cellular organelles). Figure 2 emphasizes the major centrifugation and ultracentrifugation steps of this protocol for ease of use.

-

5.

Place 50 mL conical tubes into Rotor A-4-62 and pellet down cells by centrifuging tubes in Centrifuge 5810 R at 1,000 rpm for 5 min at 4°C.

-

6.

Discard pellet and transfer supernatant into new 50 mL conical tubes.

-

7.

Centrifuge tubes in Centrifuge 5810 R at 3,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C (Figure 1B).

Note: While samples are in centrifuge, we suggest turning on/setting Optima XPN-80 to 4°C and placing SW 32.1 Ti Swinging-Bucket rotor in cold room to allow sufficient time for pre-cooling.

-

8.

Discard pellet and transfer supernatant into new 50 mL conical tubes.

-

9.

Centrifuge tubes in Centrifuge 5810 R at 4,000 rpm for 30 min at 4°C.

-

10.

Transfer supernatant into ultracentrifuge tubes.

CRITICAL: Be cautious when transferring supernatant in steps 6, 8, and 10 (centrifugation steps) because the pellets contain cells, dead cells, and cell debris, which will contaminate the EV pellet. The use of a portable pipette controller is recommended until ~5 mL media remain in centrifuge tube to minimize disturbances to cell pellet. The remaining media should be collected using P200 and P1000 pipettes.

-

11.

Place ultracentrifuge tubes into pre-cooled SW 32.1 Ti Swinging-Bucket rotor and centrifuge tubes in Optima XPN-80 Ultracentrifuge at 22,000 rpm for 140 min at 4°C.

Note: Ultracentrifuge tubes should remain balanced. Use cold PBS and add to ultracentrifuge tube with media (Figure 1C).

CRITICAL: It is necessary to fill ultracentrifuge tubes to a sufficient volume, as the tubes may collapse and limit the ability to recover EV sample.

-

12.

Remove media and resuspend pellets in 10 mL cold PBS.

CRITICAL: Do NOT use aspirator to remove media because this may inadvertently remove the EV pellet from the ultracentrifuge tube. Instead, remove media by gently pipetting using P1000 pipette. When ~1–2 mL media remain in the ultracentrifuge tube, use P200 pipette to remove residual media.

-

13.

Centrifuge samples in Optima XPN-80 Ultracentrifuge at 22,000 rpm for 140 min at 4°C

-

14.

Carefully aspirate supernatant and resuspend pellet in suitable buffer for further downstream applications and characterization/identification analyses, such as immunoblot, mass spectrometry, and TEM.

Note: Specific buffer and volume for EV resuspension is dependent on specific downstream analyses and applications. For immunoblot and TEM, we suggest resuspending in 30 μL–50 μL RIPA buffer and cold PBS, respectively, and incubating on ice for 10 min. For ICP-mass spectrometry, we resuspended EV-containing pellet in 0.5 mL PBS and centrifuged in a SpeedVac vacuum concentrator at 45°C. Samples were then digested in 100 μL HNO3, heated for 20 min at 65°C, and diluted to 2 mL with ddH2O before analysis.

Optional: EV-containing pellets can be stored at −80°C while maintaining EV membrane integrity and quality (Lee et al., 2016), though we suggest avoiding repeated freeze/thaw cycles to avert sample degradation.

Figure 2.

Illustrative extracellular vesicle isolation protocol overview

After cell culture preparation and sample treatment, the media is collected and undergoes two phases for EV isolation and enrichment: (1) centrifugation and (2) ultracentrifugation. During (1), cells (alive and dead) and debris are removed. EVs are then separated and enriched in (2). Figure partially created using BioRender.

Expected outcomes

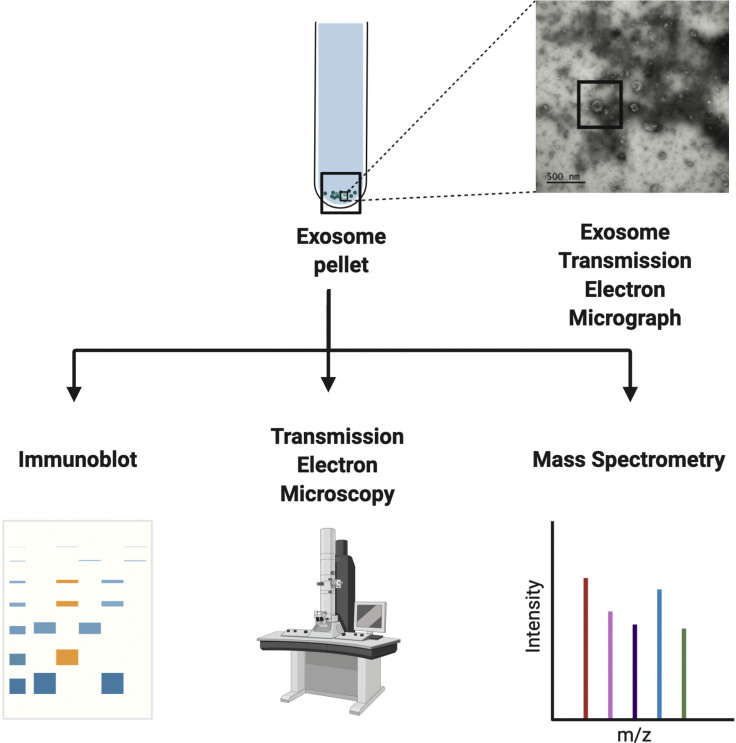

After the centrifugation and ultracentrifugation of the collected cell culture media, this protocol produced separated EVs from adherent epithelial cell lines. In order to accurately determine the effectiveness and efficacy of this protocol, we encourage the use of further characterization procedures to assess the presence and purity of the EV sample. Figure 3 highlights several methods that can be used to identify EVs from adherent epithelial cell culture samples. Of note, while we have used this protocol extensively for studies mainly in Hs578t and MCF10A cells, we anticipate other adherent epithelial cell lines to have similar results and outcomes.

Figure 3.

Methods of identification and validation of extracellular vesicles following isolation and enrichment via ultracentrifugation

Following isolation and enrichment via ultracentrifugation, EV components can be further characterized using immunoblotting, TEM, and mass spectrometry. Figure partially created using BioRender and Brown et al., 2019.

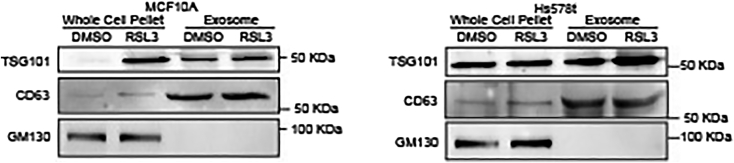

Immunoblotting verifies the presence and enrichment of EV-specific biomarkers and may reveal the existence of contaminants in the sample. Probing for protein expression of key exosomal-specific markers, such as TSG-101 that are involved in multi-vesicular body (MVB) synthesis (Raiborg and Stenmark, 2009), and CD63 that are involved in EV formation (Kowal et al., 2016), supports the enrichment of EVs in the sample. Detection of non-EV-specific membrane markers, such as GM130 (Lotvall et al., 2014), suggests potential contamination and may require further protocol optimization. An immunoblot of expected results for TSG-101, CD63, and GM130 is presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Characterization of extracellular vesicle components by immunoblot

Separated EVs from RSL3-treated MCF10A and Hs578t cells were immunoblotted for TSG101, GM130, and CD63. (Figure adapted from Brown et al., 2019).

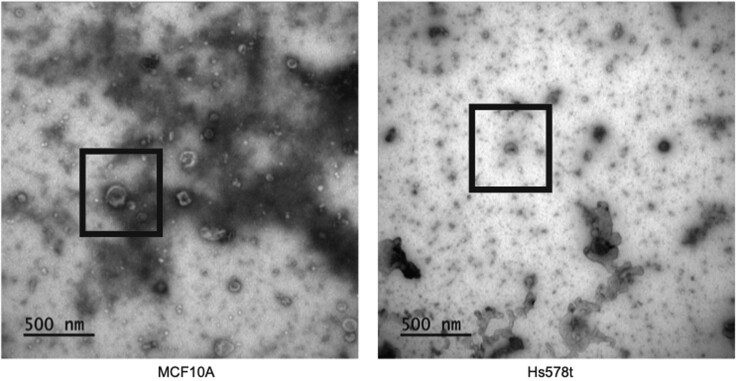

The inclusion of TEM imaging evaluates the overall EV morphology, morphological stability (e.g., membrane integrity or disruption), and size distribution profiles. Figure 5 provides an example of a TEM image, which confirmed the presence of EV within the sample and allowed for single particle measurements (e.g., diameter and particle-size distribution profiling).

Figure 5.

TEM image of separated extracellular vesicles in MCF10A and Hs578t cells

EVs separated from MCF10A and Hs578t cells were imaged by TEM. EVs are shown in black boxes. (Figure adapted from Brown et al., 2019).

Mass spectrometry (MS) based proteome profiling of EVs can further characterize EV-cargo proteins and molecules (Bandu et al., 2019), though further MS-based analyses should be assessed only after EV characterization recommendations, including immunoblotting and TEM, are met (Coumans et al., 2017 and Théry et al., 2018). Of note, while we illustrate the procedure to separate extracellular vesicles from cell culture models using ultracentrifugation, we acknowledge in our previous publication (Brown et al., 2019) that no MS-based proteomic data were produced from EV preparations. Oher published protocols can be used to achieve this objective (Bandu et al., 2019 and Patel et al., 2019).

Limitations

High volume requirement

While generally considered inexpensive and reliable in terms of reproductivity, isolation of EVs using ultracentrifugation requires a high sample volume to compensate for the relatively low yield, compared to other techniques, such as size-exclusion chromatography and ultrafiltration (Sidhom et al., 2020). The low-throughput nature of the ultracentrifugation is further restricted by the volume limitations set by the ultracentrifuge rotors and tubes.

Incomplete isolation of EVs from contaminants

Although we were able to successfully separate EVs, users may still struggle to separate EVs from other molecules of a similar size and density, such as microvesicles (Yang et al., 2020). While the absence of non-EV-specific membrane markers, such as GM130 (Lotvall et al., 2014), using immunoblotting may suggest isolated EVs, a certain amount of contamination is inherent to each EV separation method. Differential ultracentrifugation is widely recognized in co-separating non-EV-associated high-molecular weight proteins and protein complexes.

Also, the type of rotor utilized during ultracentrifugation can affect the number of lipoproteins, which can co-separate with other non-EV vesicles (Cvjetkovic et al., 2014). For EV isolation described in this protocol, we recommend using Beckman Coulter's SW 32.1 Ti Swinging-Bucket rotor (Cat#369651) and Optima XPN-80 Ultracentrifuge (Cat#A99839), though others may be sufficient.

Long turn-around time

The ultracentrifugation approach for EV isolation requires a long turn-around time to complete, as isolation and enrichment of EVs should be followed by identification and characterization of samples, given potential contamination of particles of similar density and size, such as other lipoproteins. While independently not labor intensive, obtaining separated EVs from adherent epithelial cells coupled with sample characterization via immunoblot and/or mass spectrometry is a disadvantage to the protocol, compared to commercially available EV isolation kits (Patel et al., 2019).

Troubleshooting

Problem 1

When ultracentrifuge tubes are not filled to a sufficient volume in step 11 and step 13, the tubes may collapse and limit the ability to recover the EV sample.

Potential solution

We recommend when volume is restricted by insufficient media prior to ultracentrifugation steps to gently add PBS to the ultracentrifuge tubes. Thin wall ultracentrifuge tubes must be filled to the top to prevent tube collapse, while thick wall ultracentrifuge tubes can be filled within 13 mm from the top.

Problem 2

Difficulty visualizing EV pellet at step 14 while removing supernatant, a critical component to obtaining a concentrated EV sample.

Potential solution

We have found that by gently removing supernatant in circles over a black background, such as a sheet of black construction paper. When the ultracentrifuge tube is placed over a black background, the pellet should appear opaque, compared to the clear ultracentrifuge tube. Additionally, EV pellet visualization difficulties may result from insufficient volume during media collection prior to differential centrifugation and ultracentrifugation. Potential solutions for this are identified below in Problem 3 under Potential Solution.

Problem 3

Low EV yield/insufficient EV enrichment for immunoblot following step 14.

Potential solution

Though several factors are critical for high EV yields and enrichment for this protocol, we have found that these were most sensitive to the number of plates cultured in step 1. Preparation of more additional plates for subculturing cells may increase yields to allow for sufficient protein for immunoblotting; however, this will be restricted by the volume limitations of the ultracentrifuge and rotor. We have harvested up to 12–150 × 20 mm TC-treated dishes, each with 20 mL of media, at times to get sufficient EV yield for either immunoblot, mass spectrometry, or TEM.

Cell viability may also be capable of affecting EV biogenesis and secretion. Thus, it may be necessary to assess cell viability using the Trypan Blue Exclusion test.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Arthur Mercurio (arthur.mercurio@umassmed.edu).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and code availability

This study did not generate/analyze any dataset or code.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant CA218085 (A.M.M.) and ACS grant 130451-PF-17-105-01-CSM (C.W.B.). The Electron Microscopy Core Facility is funded in part by NIH Research equipment grants and by UMMS Office of Research.

Author contributions

P.C., C.W.B., J.J.A., and A.M.M. conceived the study. P.C., C.W.B., and A.M.M. wrote the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Peter Chhoy, Email: peter.chhoy@umassmed.edu.

Arthur M. Mercurio, Email: arthur.mercurio@umassmed.edu.

References

- Bandu R., Oh J.W., Kim K.P. Mass spectrometry-based proteome profiling of extracellular vesicles and their roles in cancer biology. Exp. Mol. Med. 2019;51:1–10. doi: 10.1038/s12276-019-0218-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown C.W., Amante J.J., Chhoy P., Elaimy A.L., Liu H., Zhu L.J., Baer C.E., Dixon S.J., Mercurio A.M. Prominin2 drives ferroptosis resistance by stimulating iron export. Dev. Cell. 2019;51:575–586. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2019.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y., Zeng Q., Han Q. Effect of pH, temperature and freezing-thawing on quantity changes and cellular uptake of exosomes. Protein Cell. 2019;10:295–299. doi: 10.1007/s13238-018-0529-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coumans F.A.W., Brisson A.R., Buzas E.I., Dignat-George F., Drees E.E.E., El-Andaloussi S., Emanueli C., Gasecka A., Hendrix A., Hill A.F. Methodological guidelines to study extracellular vesicles. Circ. Res. 2017;120:1632–1648. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.309417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cvjetkovic A., Lotvall J., Lasser C. The influence of rotor type and centrifugation time on the yield and purity of extracellular vesicles. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 2014;3 doi: 10.3402/jev.v3.23111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowal J., Arras G., Colombo M., Jouve M., Morath J.P., Primdal-Bengtson B., Dingli F., Loew D., Tkach M., Théry C. Proteomic comparison defines novel markers to characterize heterogeneous populations of extracellular vesicle subtypes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2016;113:E968–E977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1521230113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M., Ban J.J., Im W., Kim M. Influence of storage condition on exosome recovery. Biotechnol. Bioprocess. Eng. 2016;21:299–304. [Google Scholar]

- Livshits M.A., Khomyakova E., Evtushenko E.G., Lazarev V.N., Kulemin N.A., Semina S.E., Generozov E.V., Govorun V.M. Isolation of exosomes by differential centrifugation: Theoretical analysis of a commonly used protocol. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:17319. doi: 10.1038/srep17319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotvall J., Hill A.F., Hochberg F., Buzas E.I., Di Vizio D., Gardiner C., Gho Y.S., Kurochkin I.V., Mathivanan S., Quesenberry P. Minimal experimental requirements for definition of extracellular vesicles and their functions: a position statement from the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 2014;3:26913. doi: 10.3402/jev.v3.26913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel G.K., Khan M.A., Zubair H., Srivastava S.K., Khushman M., Singh S., Singh A.P. Comparative analysis of exosome isolation methods using culture supernatant for optimum yield, purity and downstream applications. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:5335. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-41800-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavani K.C., Hendrix A., Van Den Broeck W., Couck L., Szymanska K., Lin X., De Koster J., Van Soom A., Leemans B. Isolation and characterization of functionally active extracellular vesicles from culture medium conditioned by bovine embryos in vitro. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:38. doi: 10.3390/ijms20010038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raiborg C., Stenmark H. The ESCRT machinery in endosomal sorting of ubiquitylated membrane proteins. Nature. 2009;458:445–452. doi: 10.1038/nature07961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelke G.V., Lasser C., Gho Y.S., Lötvall J. Importance of exosome depletion protocols to eliminate functional and RNA-containing extracellular vesicles from fetal bovine serum. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 2014;3 doi: 10.3402/jev.v3.24783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidhom K., Obi P.O., Saleem A. A review of exosomal isolation methods: Is size exclusion chromatography the best option? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;18:6466. doi: 10.3390/ijms21186466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Théry C., Witwer K.W., Aikawa E., Alcaraz M.J., Anderson J.D., Andriantsitohaina R., Antoniou A., Arab T., Archer F., Atkin-Smith G.K. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): a position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 2018;7:1535750. doi: 10.1080/20013078.2018.1535750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Z., Batagov A.O., Carter D.R., Krichevsky A.M. Fetal bovine serum RNA interferes with the cell culture derived extracellular. RNA. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:31175. doi: 10.1038/srep31175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang D., Zhang W., Zhang H., Zhang F., Chen L., Ma L., Larcher L.M., Chen S., Liu N., Zhao Q. Progress, opportunity, and perspective on exosome isolation - efforts for efficient exosome-based theranostics. Theranostics. 2020;8:3684–3707. doi: 10.7150/thno.41580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L.L., Zhu J., Liu J.X., Jiang F., Ni W.K., Qu L.S., Ni R.Z., Lu C.H., Xiao M.B. A comparison of traditional and novel methods for the separation of exosomes from human samples. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018;2018:3634563. doi: 10.1155/2018/3634563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

This study did not generate/analyze any dataset or code.