The longitudinal examination of Campylobacter jejuni subtypes throughout the broiler production continuum is required to determine transmission mechanisms and to identify potential reservoirs and the foodborne risk posed. We showed that a limited number of C. jejuni subtypes are responsible for infrequent outbreaks in broilers within production barns and that colonized birds from a small number of farms are introduced into the abattoir where a high prevalence of carcasses are subsequently contaminated with a diversity of subtypes, which are transferred onto poultry in retail settings.

KEYWORDS: Campylobacter jejuni, broiler chickens, cattle, longitudinal transmission, molecular epidemiology, molecular subtypes, public health

ABSTRACT

Significant knowledge gaps exist in our understanding of Campylobacter jejuni contamination of the poultry production continuum. Microbiological surveillance and genotypic characterization were undertaken on C. jejuni isolates longitudinally recovered from three poultry farms (weekly samples), the abattoir at which birds were processed, and at retail over a 542-day period in southwestern Alberta, Canada, as a model location. Subtypes were compared to concurrent isolates from diarrheic humans living in the study region. Barn outbreaks in broiler chickens occurred infrequently. Subtypes from colonized birds, including clinically relevant subtypes of C. jejuni, were recovered within barns and from subsequent production stages. When C. jejuni was detected in barns, most birds rapidly became colonized by a limited number of subtypes late in the cycle. However, the diversity of subtypes recovered from birds in the abattoir increased substantially. Moreover, birds deemed free of C. jejuni upon exit from the barn became contaminated within the abattoir environment, and a high prevalence of meat at retail was contaminated with C. jejuni, including subtypes that had not been previously observed in the barns. The observed increase in prevalence of contamination and diversity of C. jejuni subtypes along the chicken production continuum indicates that birds from a relatively small number of barns contaminate transport trucks and the abattoir with C. jejuni strains, which are collectively transferred to poultry within the abattoir and conveyed to and persist on retail products. We conclude that the abattoir was the primary contamination point of poultry by C. jejuni but only a subset of subtypes were a high risk to human beings.

IMPORTANCE The longitudinal examination of Campylobacter jejuni subtypes throughout the broiler production continuum is required to determine transmission mechanisms and to identify potential reservoirs and the foodborne risk posed. We showed that a limited number of C. jejuni subtypes are responsible for infrequent outbreaks in broilers within production barns and that colonized birds from a small number of farms are introduced into the abattoir where a high prevalence of carcasses are subsequently contaminated with a diversity of subtypes, which are transferred onto poultry in retail settings. However, only a subset of strains on poultry was determined to be clinically relevant. The study findings showed that resolving C. jejuni at the subtype level is important to ascertain health risks, and the knowledge obtained in the study provides information to mitigate clinically relevant subtypes to reduce the burden of campylobacteriosis.

INTRODUCTION

Campylobacteriosis incited by Campylobacter jejuni is a prevalent bacterial foodborne disease in Canada (1), in particular in Alberta (2). In contrast with other leading foodborne diseases, the incidence of campylobacteriosis is increasing globally (3). When adjusted for underreporting, the yearly per capita rate of campylobacteriosis cases in Canada was recently estimated to be 447 cases per 100,000 (4). Moreover, there is emerging evidence that many C. jejuni infections are not detected using conventional methods. In this regard, we recently reported that specialized isolation methods resulted in a greater than 2-fold increase in culture-positive diarrheic stools in samples submitted to the Chinook Regional Hospital (CRH) in southwestern Alberta (SWA) compared to results of conventional methods used in diagnostic facilities throughout Canada (≈10% versus 4.5%) (5). Thus, C. jejuni infections are common and vastly underestimated in SWA and elsewhere in Canada.

Although most cases are self-limiting, severe complications can arise, and medical intervention is required for individuals with bloody stools, high fevers, symptoms lasting >1 week, and worsening symptoms, along with neonates, pregnant women, and immunocompromised individuals (6). Moreover, postinfection sequelae, including reactive arthritis, irritable bowel syndrome, and Guillain-Barré syndrome, can also occur (7, 8). The epidemiology of campylobacteriosis is complex, with a large proportion of cases that appear to be sporadic (9). Data on outbreak-related cases show that they differ from sporadic cases in terms of seasonality and source, being more frequently associated with unpasteurized dairy (10) and contaminated water (11). Nonetheless, multiple lines of evidence suggest that the most important source of exposure leading to C. jejuni infections is handling and/or consumption of chicken meat contaminated with the bacterium (12). In Canada, source attribution analyses suggest that ≈65% to 70% of cases are attributable to the chicken reservoir (13). The primary role played by chicken is further supported by data obtained from a recent Canadian baseline study, which indicated that ≈40% of retail chicken samples are contaminated with C. jejuni (14).

As chickens represent a primary reservoir in which C. jejuni is amplified and a major vehicle for human transmission, the prevention and control of campylobacteriosis requires the development of mitigation strategies aimed at reducing the prevalence/levels of C. jejuni in chicken. Despite significant progress made in the last several decades, key knowledge gaps continue to hamper the development of practical mitigation strategies for the prevention and control of campylobacteriosis in the Canadian context. Critically, interventions proposed to date consider C. jejuni bacteria as a uniform population and fail to take into consideration genetic diversity and its impact on factors likely to impact outcomes of interest (i.e., chicken contamination rates and human infections). Critical knowledge gaps regarding C. jejuni in the chicken supply chain include the source of C. jejuni entering production systems, factors that promote its amplification and dissemination, and key points that lead to the contamination of flocks that had remained C. jejuni-free at the farm level.

Characteristics of SWA make it a potentially good location to study C. jejuni in livestock and transmission to human beings. These include high rates of enteritis, high densities of livestock, a single and public diagnostic facility, an approximate 40:60 rural/urban distribution of people, a single prominent watershed, and a spatial gradation of human activity from west to east. We employed a model agroecosystem approach and molecular microbiological surveillance to address current knowledge gaps including the following: determining potential sources of C. jejuni contamination in chicken barns; assessing the prevalence and levels of barn contamination with C. jejuni; analyzing the temporal dynamics of barn contamination with C. jejuni; assessing C. jejuni contamination at points in the chicken supply chain downstream of the farm, including abattoir and retail; and determining C. jejuni subtypes that predominate along various points in the poultry supply chain. To address these knowledge gaps, the following study objectives were created: (i) longitudinally sample broilers and the barn environment on a weekly basis in SWA for a 1-year period (three broiler barns on three separate farms); (ii) sample poultry meat from the birds in the abattoir at which they were processed; (iii) temporally sample poultry meat from the abattoir in a retail setting; and (iv) comprehensively isolate and identify C. jejuni obtained from poultry and diarrheic people living in the study region and subtype a large number of representative isolates using comparative genomic fingerprinting, a high-throughput and high-resolution method of C. jejuni subtyping, to identify transmission mechanisms of C. jejuni.

RESULTS

Campylobacter jejuni was infrequently recovered from broiler barn samples despite intensive sampling.

Three broiler farms in SWA were sampled over the 542-day sampling period. At each farm, a single barn was sampled (all production cycles). Samples were obtained from eight, seven, and seven cycles from barn A, B, and C, respectively (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). A total of 15,188 samples were longitudinally collected and processed (see Tables S1 and S2 in the supplemental material). This included 896 samples collected preproduction (i.e., barn samples prior to the arrival of new flocks—floors, walls, clean litter, beetle adults/larvae, indoor/outdoor air; samples collected during transport from hatchery to barn), 11,467 samples associated with production in the three broiler barns (i.e., samples from birds, used litter, and barn environment), 675 samples from broilers after transport from the farms to the abattoir, 1,710 samples from the abattoir at which the birds were processed, and 440 retail samples from the abattoir.

Overall, a low proportion (6.6%) of the total samples analyzed were positive for C. jejuni. This included 2.7% (212 positive samples) of the 7,739 cloacal swabs obtained from birds, 1.8% (15 positive samples) of the 848 cecal samples examined, and 1.4% (n = 3 positive samples) of 221 composite feather samples processed from cull broilers within barns. None of the 429 soiled paper liners from transportation of chicks to the broiler barns were positive for C. jejuni, and in only two instances was C. jejuni detected in barns before placement of chicks. Within-barn environmental samples also showed a low prevalence of C. jejuni during production cycles. All three barns provided chlorinated drinking water for birds, and none of the 98 water samples examined throughout the 22 broiler cycles were positive. Only one of the 382 (0.3%) feed samples examined within the barn (i.e., within a feeding hopper) tested positive. Of the 701 total barn wall samples processed, the bacterium was isolated only in three instances (0.4%) but not from barn floors. Only 1 of 319 air samples recovered within poultry barns (0.3%) tested positive, and 0 of 154 air samples collected outside and adjacent to barns tested positive. Of the 627 samples processed from barn litter, C. jejuni was recovered on eight occasions (1.3%) from all three barns. From 118 composite samples of darkling beetle larvae and adults examined, C. jejuni was recovered on two occasions (1.7%). Fly adults were infrequently observed in the barns, and none of the 28 composite fly samples examined during the summer and fall were positive for C. jejuni. Furthermore, none of the mice examined were positive for the bacterium.

Campylobacter jejuni was periodically isolated from chickens during and after transport to the abattoir.

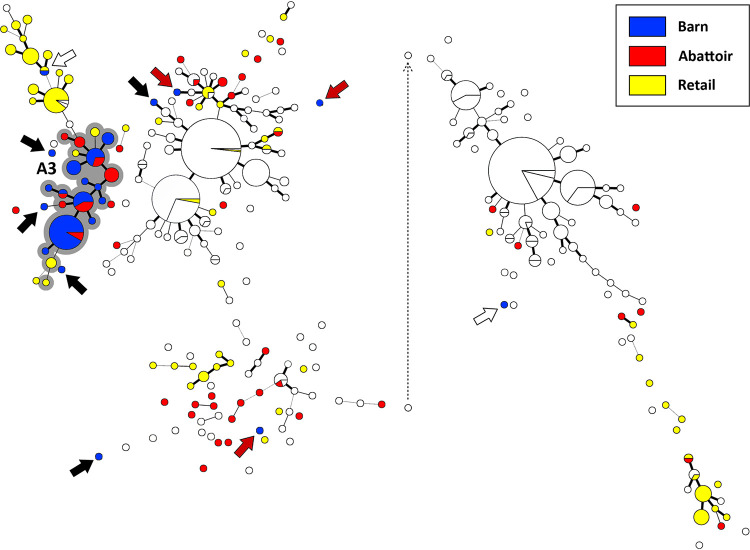

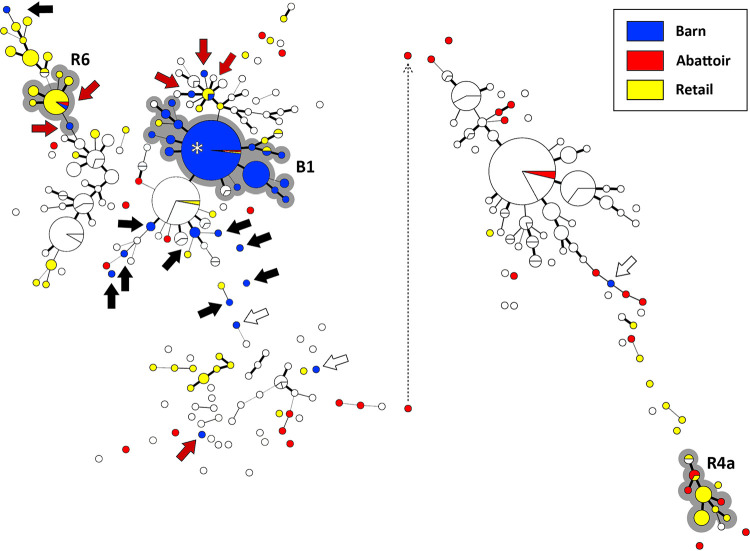

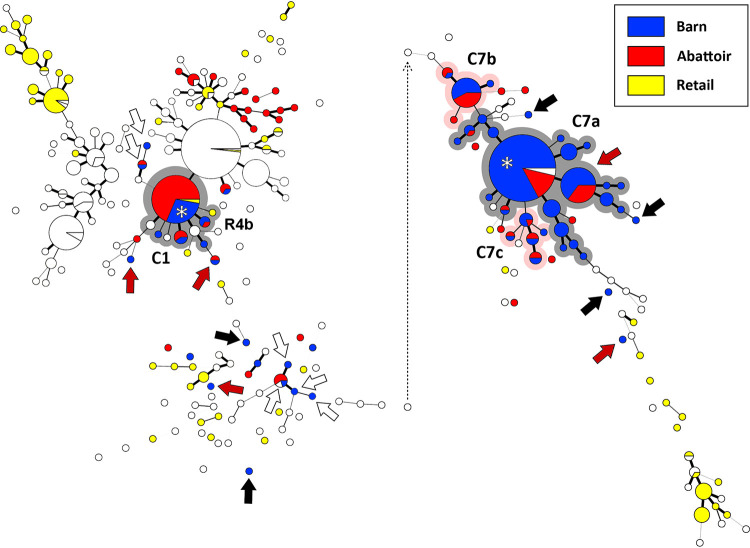

Additionally, the bacterium was isolated from 14.6% (53 positive samples) of 364 cecal samples processed and from 11.6% (36 positive samples) of 311 feather samples processed from birds after transport to the abattoir. Occurrence of C. jejuni recovered from cecal samples after euthanization of the birds at the abattoir was considered to be representative of colonization that occurred in the barn before transport, whereas C. jejuni recovered from feathers may have represented occurrences of the bacterium within the barns and/or contamination of birds during transport to the abattoir (e.g., passive contamination from transport trucks). In some instances, C. jejuni subtypes that were not previously observed within the barns were recovered from feathers of birds when sampled at the abattoir (Fig. 1 to 3, red arrows), suggesting that these birds were contaminated during transport from the barn to the abattoir.

FIG 1.

Campylobacter jejuni comparative genomic fingerprint (CGF) subtypes recovered from poultry samples from barn A (blue circles), the abattoir at which the birds were processed (red circles), and retail poultry during the sample period (yellow circles). White circles represent subtypes from other barns and abattoir/retail sample times. The minimum spanning tree was generated in Bionumerics (version 6.6; Applied Maths). The size of the circles is proportional to the number of C. jejuni isolates within the subtype. The thickness of lines connecting subtypes represents mismatched loci (i.e., one to three loci), and subtypes with no line represent ≥ four mismatched loci between respective subtypes. The grey highlighted CGF cluster marked A3 shows an outbreak within the barn during cycle 3. Black arrows show isolates from the outbreaks in the barn that differed from outbreak subtypes, red arrows show isolates that were likely obtained during transport of the birds to the abattoir, and the white arrow shows isolates that were detected in the barn for which an outbreak did not occur. The dotted line depicts repositioning of the right portion of the minimum spanning tree for presentation purposes. The CGF subtype clusters correspond to those denoted in Table 1.

FIG 2.

Campylobacter jejuni comparative genomic fingerprint (CGF) subtypes recovered from poultry samples from barn B (blue circles), the abattoir at which the birds were processed (red circles), and retail poultry during the sample period (yellow circles). White circles represent subtypes from other barns and abattoir/retail sample times. The minimum spanning tree was generated in Bionumerics (version 6.6; Applied Maths). The size of the circles is proportional to the number of C. jejuni isolates within the subtype. The thickness of lines connecting subtypes represents mismatched loci (i.e., one to three loci), and subtypes with no line represent ≥ four mismatched loci between respective subtypes. The grey highlighted CGF cluster marked B1 shows an outbreak within the barn during cycle 1. The grey highlighted CGF clusters marked R4 and R6 show instances where the same subtype was obtained from abattoir and corresponding retail samples. Black arrows show isolates from the outbreak in the barn that differed from outbreak subtypes, red arrows show isolates that were likely obtained during transport of the birds to the abattoir, white arrows show isolates that were detected in the barn for which an outbreak did not occur, and the asterisk shows that the same subtype responsible for the outbreak was recovered from skin samples from the birds within the abattoir. The dotted line depicts repositioning of the right portion of the minimum spanning tree for presentation purposes. The CGF subtype clusters correspond to those denoted in Table 1.

FIG 3.

Campylobacter jejuni comparative genomic fingerprint (CGF) subtypes recovered from poultry samples from barn C (blue circles), the abattoir at which the birds were processed (red circles), and retail poultry during the sample period (yellow circles). White circles represent subtypes from other barns and abattoir/retail sample times. The minimum spanning tree was generated in Bionumerics (version 6.6; Applied Maths). The size of the circles is proportional to the number of C. jejuni isolates within the subtype. The thickness of lines connecting subtypes represents mismatched loci (i.e., one to three loci), and subtypes with no line represent ≥ four mismatched loci between respective subtypes. The grey and pink highlighted subtype clusters marked C1 and C7 (C7a, C7b, and C7c) show outbreaks within the barn during cycles 1 and 7, respectively. The grey highlighted isolate cluster marked R4 shows an instance where the same subtype cluster was obtained from abattoir and corresponding retail samples. Black arrows show isolates from the outbreaks in the barn that differed from outbreak subtypes, red arrows show isolates that were likely obtained during transport of the birds to the abattoir, white arrows show isolates that were detected in the barn for which an outbreak did not occur, and the asterisks show that the same subtype responsible for the outbreak was recovered from skin samples from the birds within the abattoir. The dotted line depicts repositioning of the right portion of the minimum spanning tree for presentation purposes. The CGF subtype clusters correspond to those denoted in Table 1.

Although a high proportion of positive samples were associated with “barn outbreaks,” these occurred infrequently.

The bacterium was isolated from birds in one of eight cycles in barn A, one of seven cycles in barn B, and five of seven cycles in barn C (see Fig. S2 to S4 in the supplemental material). Barn outbreaks, in which >10% of samples from birds tested positive for C. jejuni and where we observed a large increase in the number of positive samples within a 1-week sampling frame, occurred in four cycles across all three barns (barn A, cycle A3; barn B, cycle B1; barn C, cycles C1 and C7). Notably, 2,378 of 2,407 (98.8%) C. jejuni isolates from barn samples were obtained in the cycles in which a barn outbreak occurred.

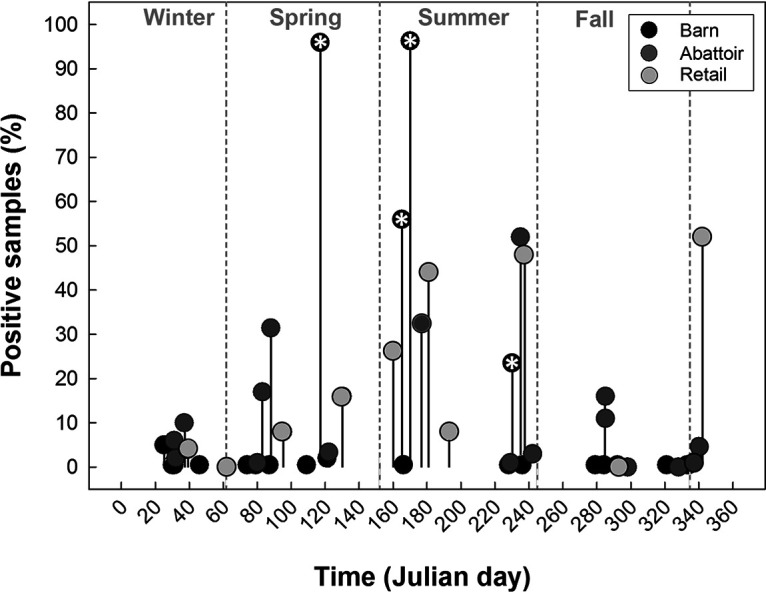

During cycles in which barn outbreaks occurred, rapid flock colonization was observed, with positive birds first detected in week 1 and most of the birds sampled at the subsequent week (≥95.9%) testing positive (e.g. cycles B1 and C7). Notably, all outbreaks occurred late in the production cycle, with some becoming evident only subsequently. For instance, the outbreak in cycle C1 was not detected in birds within the barn, but 23.6% of birds tested positive after transport to the abattoir (see Fig. S4). In two instances in barn C (i.e., cycles C1 and C6), C. jejuni was detected in a small number of birds early in the production, but an outbreak of C. jejuni did not occur within the flock on these occasions. Although most excreted fecal samples tested negative for C. jejuni, the exception was among samples from barn B during an outbreak (i.e., cycle B1, week 7) (see Fig. S3). Although abattoir and retail samples tested positive for C. jejuni throughout the year, all four outbreaks observed in the current study occurred in the spring and summer; a trend for higher rates of contamination of abattoir and retail samples was similarly observed during this period (Fig. 4).

FIG 4.

Seasonal prevalence of samples positive for Campylobacter jejuni (%) in broiler barns, the abattoir at which the birds were processed, and at retail. Markers with asterisks indicate outbreaks of C. jejuni within broiler barns (i.e., >20% of birds infected with the bacterium). Outbreaks were detected in 4 of the 22 cycles examined (18.2%). Julian day 1 is 1 January.

Outbreaks within broilers were incited by a prominent subtype.

The outbreaks that occurred (i.e., cycles A3, B1, C1, and C7) were incited by a single prominent subtype of C. jejuni (Fig. 1 to 3, grey shading). The subtypes responsible for the outbreak in barn A primarily belonged to comparative genomic fingerprinting (CGF) subtype 0957.001.001 and subtypes within the 0957.004 cluster (e.g., 0957.004.001, 0957.004.002, 0957.004.007, 0957.004.011) (Table 1). Examination of metadata within the Canadian Campylobacter Comparative Genomic Fingerprinting Database (C3GFdb) indicated that these subtypes in cluster 0957.004 are primarily associated with cattle, but they also infect people and colonize chickens; CGF subtype 0957.001.001 is particularly prevalent within the C3GFdb. Although this subtype has been previously observed in Alberta, it has been primarily observed in Ontario. For the outbreak in barn B, the CGF subtypes responsible included 4 subtypes within the 0817.001 cluster and subtype 0817.006.002. These subtypes, which are common in Alberta and associated with people, chickens, and cattle, were also responsible for the first outbreak in barn C (i.e., C1). For the second outbreak observed in barn C (i.e., C7), there was a much more heterogeneous mixture of CGF subtypes observed, although 0735.001.002 and 0735.003.004 were predominant. These clusters are most commonly associated with chickens in Alberta and are also found in people and cattle. Novel subtypes associated with this outbreak were observed (Fig. 3, C7b and C7c), and these were most closely related to subtypes 0901.001.002 as well as 0731.006.002 and 0.735.003.004, respectively.

TABLE 1.

CGF subtypes of Campylobacter jejuni linked to barn outbreaks and longitudinally associated with broilers and meat with the corresponding subtype data within the C3GFdba

| Cluster identifierb | No. of isolatesc | CGF subtype | Rank | % Isolates of the same CGF subtype by subcategory |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source |

Province |

||||||||||||

| Hu | Ch | Ca | BC | AB | SK | MB | ON | QC | AP | ||||

| A3 | 4 | 0957.004.001 | 70 | 3.8 | 0.0 | *66.0 | 5.7 | 5.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 45.3 | 18.9 | 7.5 |

| A3 | 36 | 0957.004.002 | 173 | 0.0 | 0.0 | *82.4 | 17.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 35.3 | 0.0 | 35.3 |

| A3 | 12 | 0957.004.007 | 453 | 0.0 | 0.0 | *100.0 | 0.0 | 20.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 60.0 | 0.0 |

| A3 | 1 | 0957.004.011 | 3,121 | 0.0 | 0.0 | *100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| A3 | 10 | 0957.001.001 | 7 | 6.3 | 7.2 | *41.9 | 12.5 | 14.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 59.7 | 4.1 | 1.6 |

| A3 | 1 | 0631.002.005 | 1,160 | 0.0 | 0.0 | *50.0 | 50.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 50.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| A3 | 28 | Novel (n = 15) | |||||||||||

| Subtotal | 92 | Combined | 5.5 | 5.8 | *47.7 | 11.8 | 12.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 55.8 | 6.5 | 0.0 | |

| B1/C1/R4b | 1 | 0817.001.002 | 3,121 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| B1/C1/R4b | 2 | 0817.001.003 | 1,160 | 50.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| B1/C1/R4b | 109 | 0817.001.004 | 87 | 0.0 | 4.9 | 9.8 | 4.9 | 43.9 | 0.0 | 2.4 | 36.6 | 4.9 | 0.0 |

| B1/C1/R4b | 70 | 0817.001.008 | 1,160 | 0.0 | 0.0 | *50.0 | 0.0 | 50.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 50.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| B1/C1/R4b | 22 | 0817.006.002 | 3,121 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| B1/C1/R4b | 33 | Novel (n = 18) | |||||||||||

| Subtotal | 237 | Combined | 2.1 | 4.3 | 10.6 | 4.3 | 46.8 | 0.0 | 2.1 | 36.2 | 4.3 | 0.0 | |

| R4a | 1 | 0609.003.002 | 229 | 16.7 | *33.3 | 50.0 | 0.0 | 58.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| R4a | 2 | 0609.004.002 | 118 | 6.7 | *90.0 | 3.3 | 0.0 | 96.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| R4a | 8 | 0609.006.004 | 21 | 10.8 | *75.2 | 6.4 | 1.3 | 46.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 48.4 | 0.6 | 0.0 |

| R4a | 1 | 0609.008.001 | 751 | 66.7 | *33.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| R4a | 3 | 0609.013.002 | 54 | 5.6 | *85.9 | 7.0 | 0.0 | 87.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 9.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| R4a | 7 | 0611.001.002 | 159 | 5.3 | *52.6 | 31.6 | 0.0 | 5.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 94.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| R4a | 2 | Novel (n = 2) | |||||||||||

| Subtotal | 24 | Combined | 9.6 | *75.7 | 9.6 | 0.7 | 59.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 34.9 | 0.3 | 0.0 | |

| R6 | 19 | 0960.007.001 | 14 | 16.2 | 8.6 | *55.7 | 7.1 | 19.0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 48.1 | 11.4 | 0.5 |

| R6 | 1 | 0960.008.001 | 3,121 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| R6 | 2 | 0960.009.001 | 554 | 0.0 | 0.0 | *100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| R6 | 5 | Novel (n = 3) | |||||||||||

| Subtotal | 27 | Combined | 15.8 | 8.4 | *56.3 | 7.0 | 19.1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 48.8 | 11.2 | 0.5 | |

| C7a | 1 | 0731.001.005 | 13 | 14.2 | *62.7 | 17.5 | 0.0 | 50.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 47.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| C7a | 9 | 0731.004.004 | 179 | 6.3 | *50.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| C7a | 8 | 0735.001.001 | 3,121 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| C7a | 135 | 0735.001.002 | 48 | 5.3 | *85.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 93.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| C7a | 37 | 0735.003.004 | 453 | 0.0 | *100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| C7a | 1 | 0735.009.002 | 3,121 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| C7a | 26 | Novel (n = 12) | |||||||||||

| Subtotal | 217 | Combined | 11.6 | *67.8 | 11.9 | 0.0 | 65.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 33.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| C7b | 0 | 0901.001.002c | 3,121 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| C7b | 36 | Novel (n = 7) | |||||||||||

| Subtotal | 36 | Combined | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| C7c | 0 | 0731.006.002c | 751 | 66.7 | *33.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 66.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 33.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| C7c | 0 | 0735.003.004c | 453 | 0.0 | *100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| C7c | 16 | Novel (n = 5) | |||||||||||

| Subtotal | 16 | Combined | 25.0 | *75.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 87.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 12.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

Hu, human beings; Ch, chickens; Ca, cattle; BC, British Columbia; AB, Alberta; SK, Saskatchewan; MB, Manitoba; ON, Ontario; QC, Quebec; AP, Atlantic Provinces (i.e., New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland and Labrador); *, primary nonhuman host.

Total number of outbreak isolates examined were 649 (representing 88 CGF subtypes).

In barns in which an outbreak occurred, other C. jejuni subtypes were present at low frequencies (Fig. 1 to 3, black arrows). In barn A, nonoutbreak strains were isolated from cloacal, cecal, and darkling beetle samples. In both barn B and C, nonoutbreak strains were recovered from cloacal, cecal, and fecal samples. Albeit relatively rare, in some instances C. jejuni subtypes, including ones found early in the cycle period, were observed in barns for which an outbreak did not occur (Fig. 1 to 3, white arrows). With a few exceptions (0044.005.002, 0082.001.001, 0253.004.001, 0811.008.001, 0811.009.002, 891.001.001, and 0960.007.001), the subtypes observed in barns that were not associated with outbreaks were novel or with a low prevalence within the C3GFdb; only three of these subtypes (0082.001.004, 0253.004.001, and 0960.007.001) were commonly associated with chickens (see Tables S3 to S5 in the supplemental material).

Strains inciting outbreaks subsequently contaminated birds within the abattoir and were subsequently observed on retail meat.

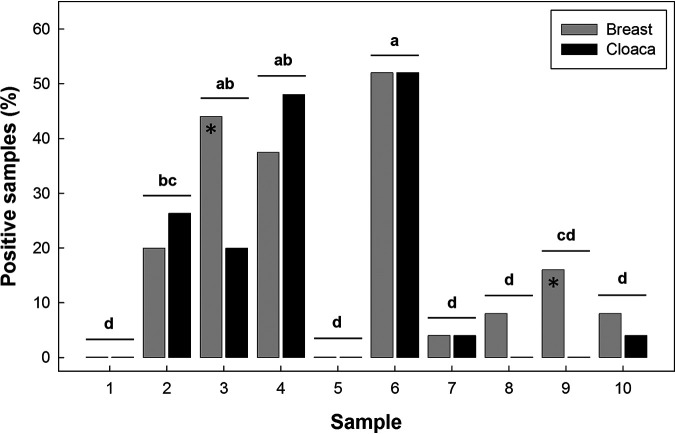

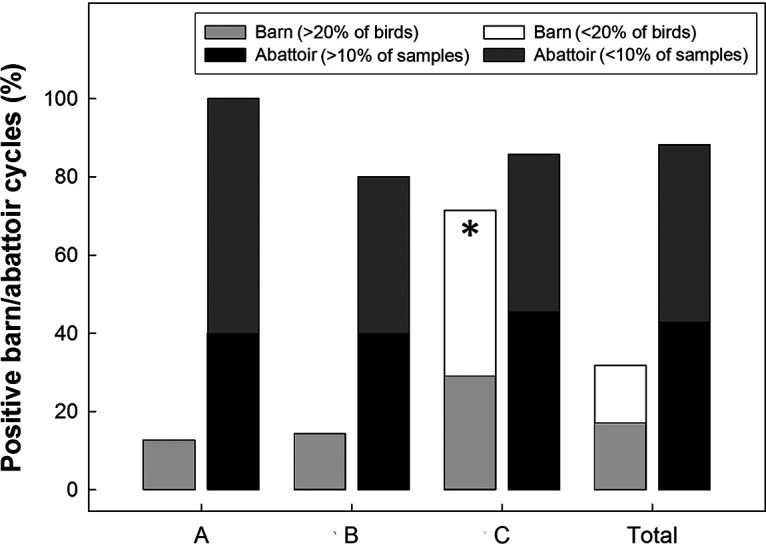

Overall, C. jejuni was recovered from 11.6% (n = 198) of 1,710 skin samples obtained from birds at the abattoir at which they were processed; at least one sample at the abattoir was positive for 85.7% to 100% of the cycles examined (Fig. 5). The bacterium was readily isolated from skin samples in the abattoir from birds originating from a barn in which a C. jejuni outbreak was detected (see Fig. S2 to S4). However, the bacterium was also recovered from birds originating from barns that were deemed free of C. jejuni (i.e., cycles A4, A5, A6, A7, A8, B3, B5, B6, B7, C1, C2, C4, C5, C6, and C7), including from birds that were deemed negative after transport (i.e., cycles A5, A7, B3, B6, B7, C2, and C5). On retail meat, C. jejuni was isolated from 21.0% (n = 46) and 16.7% (n = 37) of 219 skin samples from the breast and 221 skin samples from the cloacal region, respectively. The prevalence of contamination of retail poultry ranged from 0% to 52.0% (Fig. 6).

FIG 5.

Overall prevalence of barn/abattoir cycles that were positive for one or more isolates of Campylobacter jejuni (%) in/from farm A, B, and C. Instances where greater than 20% of birds in barns and greater than 10 of the samples in abattoirs are indicated within the graph. The histogram bar indicated with the asterisk indicates that the prevalence of samples positive for C. jejuni at Farm C was higher than for farms A and B (P = 0.051).

FIG 6.

Prevalence of retail samples positive for Campylobacter jejuni (%) at 10 sample times over the 542-day duration of the study. Asterisks indicate instances where the prevalence of samples positive for C. jejuni differed (P < 0.050) between skin samples from breasts versus the cloacal region at individual sample times. Histograms at individual sample times not followed by the same letter differ (P ≤ 0.050). See Fig. S1 in the supplemental material for retail relative to broiler sampling times.

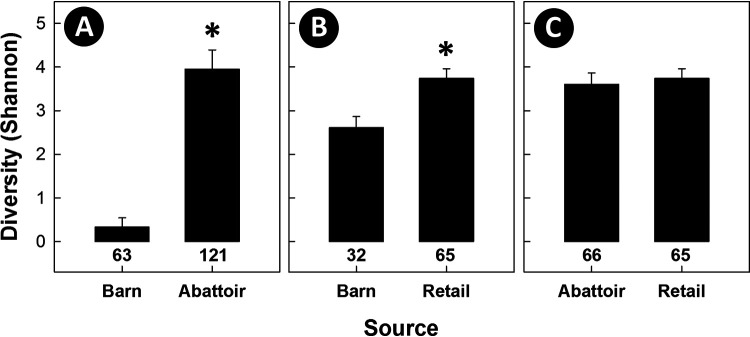

Subtypes of C. jejuni that incited outbreaks in all three barns were subsequently isolated from birds within the abattoir, providing evidence that C. jejuni from colonized chickens entering the abattoir was transferred to meat during processing within the plant (Fig. 1 to 3). A total of 64, 92, and 47 subtypes were recovered from birds in barns, from meat in the abattoir, and from meat at retail, respectively (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). Adjusted to equivalent numbers of isolates by random subsampling, the diversity of C. jejuni subtypes associated with birds in the abattoir was substantially higher (P < 0.001) than what was observed in barns (Fig. 7). Consistent with this observation, meat from birds that entered the abattoir from barn cycles that were deemed free of C. jejuni prior to transport to the plant subsequently became contaminated with a diversity of subtypes of the bacterium (Fig. 1 to 3; see also Fig. S5). It is also noteworthy that strains not associated with barn outbreaks were also observed on birds from barns under surveillance, indicating that there is ongoing contamination within the abattoir environment during processing. Subtype diversity remained higher (P < 0.001) on retail meat relative to that in barns; there was no difference (P = 0.432) in subtype diversity of C. jejuni isolated from birds in the abattoir and from retail meat.

FIG 7.

Subtype richness (numbers at base of histogram bars) and diversity (Shannon H) of Campylobacter jejuni subtypes longitudinally recovered from barns, the abattoir at which the birds were processed, and retail poultry. (A) Isolates from barns and the abattoir. (B) Isolates from barns and retail poultry. (C) Isolates from the abattoir and retail poultry. Histogram bars for Shannon H diversity within individual graphs indicated with an asterisk differ (P < 0.001) from the barn source. There was no difference (P = 0.432) in diversity of isolates recovered from the abattoir and retail poultry. In all instances, random subsampling was applied to ensure that the number of isolates examined per source were equal; subtype diversity for 482, 234, and 234 total isolates were included for A, B, and C, respectively (950 total genotyped C. jejuni isolates).

Some strains recovered from chickens were associated with infections of people during the study period.

A number of C. jejuni subtypes associated with chickens were also recovered from diarrheic people in SWA during the study period. Of the 176 subtypes of C. jejuni recovered from chickens, 29 (14.0%) were recovered from human beings during the study period (see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material), and a number of prominent C. jejuni subtypes associated with chickens and diarrheic humans in SWA during the study period are prevalent within the C3GFdb (Table 2). Notably, some of the C. jejuni subtypes isolated from diarrheic people in the current study were commonly associated with chickens throughout Canada (i.e., 0933.004.002, 0957.001.001, and 0960.007.001), others were primarily associated with cattle (0609.006.004, 0609.013.002, 0695.006.001, and 0735.001.002), and others had not previously been detected in chickens (i.e., 0092.001.004, 0735.001.002, 0811.012.002, and 0853.008.001).

TABLE 2.

CGF subtypes of Campylobacter jejuni associated with chickens and diarrheic humans in southwestern Alberta during the study period with the corresponding subtype data within the C3GFdba

| CGF Identifier | No. of isolatesb | CGF subtype | Rank | % Isolates of the same CGF subtype by subcategory |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source |

Province |

||||||||||||

| Hu | Ch | Ca | BC | AB | SK | MB | ON | QC | AP | ||||

| 683 | 9 | 0061.001.002 | 78 | 14.9 | 31.9 | 48.9 | 4.3 | 48.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 36.2 | 6.4 | 0.0 |

| 605 | 15 | 0092.001.004 | 173 | 35.3 | 0.0 | 23.5 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 804 | 52 | 0238.007.002 | 55 | 20.0 | 8.6 | *65.7 | 1.4 | 67.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 22.9 | 4.3 | 0.0 |

| 849 | 18 | 0269.004.001 | 23 | 36.8 | 17.4 | *45.8 | 1.4 | 58.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 36.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 523 | 10 | 0609.006.004 | 21 | 10.8 | 6.4 | *75.2 | 1.3 | 46.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 48.4 | 0.6 | 0.0 |

| 526 | 4 | 0609.013.002 | 54 | 5.6 | 7.0 | *85.9 | 0.0 | 87.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 9.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 405 | 14 | 0695.006.001 | 2 | 14.1 | 3.6 | *74.2 | 0.3 | 80.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 16.8 | 1.5 | 0.0 |

| 321 | 136 | 0735.001.002 | 48 | 5.3 | 0.0 | *85.5 | 0.0 | 93.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 216 | 5 | 0811.012.002 | 554 | 25.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 25.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 75.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 241 | 12 | 0853.008.001 | 216 | 30.8 | 0.0 | *46.2 | 7.7 | 53.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 49 | 3 | 0933.004.002 | 35 | 25.5 | *47.9 | 11.7 | 16.0 | 26.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 48.9 | 0.0 | 3.2 |

| 55 | 4 | 0933.007.005 | 245 | 9.1 | *90.9 | 0.0 | 27.3 | 18.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 18.2 | 18.2 | 9.1 |

| 26 | 11 | 0957.001.001 | 7 | 6.3 | *41.9 | 7.2 | 12.5 | 14.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 59.7 | 4.1 | 1.6 |

| 83 | 20 | 0960.007.001 | 14 | 16.2 | *55.7 | 8.6 | 7.1 | 19.0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 48.1 | 11.4 | 0.5 |

| 432 | 3 | 0982.007.003 | 1,160 | 0.0 | 50.0 | 50.0 | 0.0 | 50.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 441 | 2 | 0982.007.002 | 129 | 11.1 | 7.4 | *81.5 | 7.4 | 92.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 533 | 2 | Novel | |||||||||||

| 534 | 2 | Novel | |||||||||||

Hu, human beings; Ch, chickens; Ca, cattle; BC, British Columbia; AB, Alberta; SK, Saskatchewan; MB, Manitoba; ON, Ontario; QC, Quebec; AP, Atlantic Provinces (i.e., New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland and Labrador); *, primary nonhuman host.

Total number of isolates examined was 322.

DISCUSSION

We used SWA as a model location to address important knowledge gaps regarding the prevalence and distribution of C. jejuni throughout the broiler chicken continuum. To more fully elucidate the establishment and transmission of C. jejuni in the poultry supply chain, we performed comprehensive longitudinal sampling throughout the course of all production cycles taking place on three broiler barns across three separate farms over a 1.5-year period. Comprehensive on-barn sampling was performed weekly throughout the study period and included sampling of birds during and after transfer to the abattoir at which they were processed and sampling of meat from the birds destined for retail. To allow tracking of C. jejuni strains contaminating the production continuum, the resulting isolates were characterized using CGF, a high-resolution method of C. jejuni subtyping with greater discriminatory power than multilocus sequence typing (MLST), the leading method for C. jejuni subtyping.

A major aim of this project was to comprehensively examine the chicken production continuum in order to better understand C. jejuni contamination events. Our results highlight findings that could have significant implications for the development of efficacious mitigation strategies to reduce the prevalence of C. jejuni in the poultry continuum. Vertical transmission has been purported to be responsible for C. jejuni introduction into broiler barns (15), but our analysis showed that chicks obtained from the hatchery were free of C. jejuni, which is consistent with evidence that vertical transmission of culturable C. jejuni is not a significant mode of transmission in many broiler operations (16). All of the broiler barns examined in the current study were subject to industry standard sanitation before the addition of chicks to the barns (i.e., between cycles) (https://www.chickenfarmers.ca), and only in rare instances was C. jejuni recovered before placement of chicks in the barn, demonstrating the general effectiveness of the sanitation protocols applied. This contrasts with other studies that showed that C. jejuni was ubiquitous in the barn environment (external and internal) (17), especially during/after outbreaks (18). Moreover, the results of a previous systematic review indicated that insufficient sanitation of broiler barns was a primary risk for the introduction of C. jejuni into a broiler flock (19).

Extensive sampling of the barn environment, including feed, drinking water, insects, pests, air, floor, and wall samples, revealed infrequent C. jejuni-positive samples, indicating that the bacterium likely entered the farm via an exogenous source(s) by an unknown mechanism and/or that the source of contamination could be sporadically found in the barn environment. Notably, when colonization of broilers by C. jejuni occurred, it happened late in the production cycle, with the majority of the flock becoming rapidly colonized (i.e., within 1 week) following initial detection of positive samples. Although chicken, abattoir, and retail samples were positive for the bacterium throughout the year, when contamination of broilers occurred, it was typically in the spring and summer. Despite the high prevalence of C. jejuni that we observed on poultry meat destined for retail, colonization of chickens by C. jejuni in Alberta broiler farms was a rare event, with two-thirds of production cycles failing to register positive samples, despite intensive on-farm sampling and enhanced microbiological methods of C. jejuni culturing that we have previously used to highlight the potential for substantial underestimation of culture-positive diarrheic stools in Canada (5).

A fundamental issue faced by researchers studying the molecular epidemiology of C. jejuni is the effect of different isolation protocols and culture media on the frequency of detection and the diversity of C. jejuni subtypes recovered from strains in a sample (20–22). Enrichment isolation followed by subsequent culturing using antimicrobial supplements is a common strategy used to recover C. jejuni (23, 24), and it is the standard method for isolating C. jejuni from poultry (25). However, we have recently shown that enrichment methods are particularly prone to subtype bias from mixed cultures compared to direct plating methods (22), presumably due to differential sensitivity of strains to selective agents and/or adaptation to growth in liquid medium. In an attempt to reduce enrichment bias, we used a broth that contained no selective supplements (Bolton broth with laked horse blood), and we isolated C. jejuni from the broth using membrane filtration on a medium containing no selective agents (KA). As has been observed by others, enrichment isolation was superior to direct plating for isolating C. jejuni (see Fig. S7 in the supplemental material for additional detail). Although we expected to encounter reduced diversity of subtypes recovered by enrichment, a comparative examination of subtypes recovered using the two methods showed that the diversity of C. jejuni isolates recovered by enrichment was not reduced and was actually substantially higher relative to direct plating (see Fig. S8 in the supplemental material for additional detail). The use of membrane filtration in combination with enrichment has been reported previously (25, 26), but the impact of this method on subtype bias has not been extensively examined and warrants further investigation. Another challenge that we faced was whether to process more samples or to expend resources on the recovery and characterization of multiple isolates from each positive sample, a logistical dilemma confronted by all researchers studying the molecular epidemiology of C. jejuni. Given the scale of sampling in the current study, we limited our selection to five arbitrarily selected isolates per positive sample; we did not detect intrasample diversity in the positive samples that were examined.

A relatively large number of studies have examined C. jejuni at various places along the poultry production continuum (19), but comparatively few have examined the bacterium longitudinally from “farm to fork” (27–40). Although snapshot and longitudinal studies conducted to date have shown that C. jejuni is ubiquitous within the continuum, few studies have examined the distribution and prevalence of the bacterium at a subtype level of resolution, which is essential for tracking contamination and spread within the production chain. Moreover, a majority of longitudinal studies with genotyping data have characterized a relatively small subset of recovered C. jejuni isolates (29–33, 37–39). In addition, studies have also relied on subtyping methods such as Penner serotyping, flagellin gene typing, ribotyping, random amplified polymorphic DNA-PCR (RAPD), or pulsed field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), which are labor intensive, have low resolution, and possess poor reproducibility (19, 41). The large collection of C. jejuni isolates recovered in the current study was analyzed by high-resolution subtyping using CGF, a low-cost and high-throughput method for subtyping of C. jejuni isolates that was developed by our team (41, 42) and which has been used to elucidate various aspects of the molecular epidemiology of the bacterium in Canada (43–46). Importantly, CGF data along with metadata on >30,000 C. jejuni isolates recovered from human, livestock, wildlife, and environmental samples collected from across Canada are housed within the Canadian Campylobacter Comparative Genomic Fingerprinting Database (C3GFdb), which can help provide an important epidemiological context to study findings based on Canadian surveillance data. These data highlight extensive genetic diversity within the C. jejuni population circulating in Canada, with nearly 5,000 distinct subtypes observed to date.

Although a rapid progression of colonization by C. jejuni in broiler chickens is well documented, the molecular epidemiology of the bacterium in outbreaks in broiler barns is not well understood at present (19). In the current study, when outbreaks occurred in broiler barns, we observed that a single C. jejuni CGF subtype cluster, and likely a single CGF subtype, was responsible for the outbreak. Consistent with our observation, Bull et al. (18) and Ridley et al. (31) observed limited diversity of C. jejuni bacteria colonizing broilers in the United Kingdom. However, in contrast to our study, they observed instances where a dominant subtype was supplanted as the outbreak developed. Host specificity exists for “specialist,” and to a lesser extent for “generalist,” subtypes of C. jejuni (47–50), thereby permitting researchers to predict likely reservoirs from which the bacterium originated. To ascertain trends in host associations and geographical occurrence, we examined data on subtypes against information within the C3GFdb. The C. jejuni strains responsible for outbreaks in broiler barns in the current study contained subtypes that were associated with multiple hosts, including chickens, beef cattle, and human beings. However, subtypes responsible for the outbreak in barn A (cycle A3) and barn B (cycle B1) were historically associated primarily with cattle and were pan-Canadian. In contrast, the C. jejuni subtype responsible for the second outbreak detected in barn C (cycle C7) was primarily associated with chickens in both Alberta and Ontario.

An important insight from an examination of data within the C3GFdb is that a large proportion of subtypes in circulation have rarely, if ever, been associated with human infections. Conversely, a small number of subtypes, which we consider clinically relevant subtypes (CRS) of C. jejuni, are disproportionally implicated in human clinical cases. Thus, epidemiological evidence suggests that not all C. jejuni subtypes pose an equal risk to human health. Although the mechanisms responsible are unknown at present, it is possible that CRS possess an increased ability to either enter and/or survive throughout the chicken supply chain or to cause infection. Importantly, interventions proposed to date consider C. jejuni bacteria as a uniform population and fail to take into consideration genetic diversity and its impact on factors likely to impact outcomes of interest (i.e., chicken contamination rates and human infections). Critical knowledge gaps regarding C. jejuni in the chicken supply chain include the source of CRS entering production systems, factors that promote the amplification and dissemination of CRS, and key points that lead to the contamination of flocks that had remained C. jejuni-free at the farm level.

Despite the evidence indicating that a single subtype was responsible for outbreaks in the current study, other C. jejuni subtypes not involved in outbreaks were recovered from the barn environment and from individual chickens during the outbreak but at low frequencies. A limited number of studies have demonstrated the occurrence of C. jejuni in barns before placement of chicks and the role that strains play in outbreaks. Our results contrast with Bull et al. (18) who obtained evidence that the strains present in the broiler barn before the outbreak were indistinguishable from the strains that were subsequently isolated from broilers. Importantly, however, the findings of Bull et al. (18) were based on MLST, which has limited discriminatory power compared to that of CGF. For example, based on in silico prediction of CGF subtype and MLST on whole-genome sequence data available in public repositories, CGF can discriminate multiple subtypes (n = 59 and 56, respectively) among sequence type 21 (ST-21) (n = 879) and ST-45 (n = 1,207) genomes in these prevalent sequence types (data not shown). We observed that in some instances C. jejuni strains detected in the barn environment did not contribute to outbreaks even though they were present before the outbreak was initiated, a finding that differs from previous conclusions (19). It is uncertain why some C. jejuni subtypes initiated outbreaks while others present within the barns did not. It is noteworthy that the nonoutbreak subtypes were primarily assigned to subtypes that were novel or rarely occurring in the C3GFdb. Regardless, the majority of these subtypes have previously been observed in chickens, suggesting that they are capable of chicken colonization. Another possibility is that nonoutbreak strains were not able to persist well in the environment, they were present in insufficient densities, they were inaccessible to chickens, or they were not readily transmitted among animals. A threshold of inoculum is required to successfully colonize birds (51), and emerging evidence indicates that C. jejuni subtypes possess differential ability to survive extraintestinally (52). Thus, relevant knowledge gaps include whether outbreak strains are better able to persist in the barn environment or possess characteristics that favor longitudinal transmission. The subtypes recovered in the current study (e.g., outbreak versus nonoutbreak subtypes) could be used to empirically address these questions.

A detailed longitudinal examination of C. jejuni within barns also allowed us to identify, with a high degree of certainty, flocks that were free of C. jejuni. This information allowed us to examine the degree to which C. jejuni transmission occurred downstream of the farm environment, during transport and within the abattoir environment. In a number of instances, C. jejuni was isolated from feather samples after transport from birds that were deemed free of the bacterium upon exit from the barn, and this included subtypes that were not observed in barns in which C. jejuni outbreaks occurred. This suggests that contamination of the birds with C. jejuni occurred during transport. It is noteworthy that the large number of broilers (>10,000 birds) within the barns that we monitored necessitated that a subset of arbitrarily selected birds was examined for C. jejuni at individual sample times during their tenure within the barns. Thus, it is possible that birds within barns may have been colonized by C. jejuni at low frequencies, and this was not detected. Nevertheless, birds were also subsampled after transport, and coupled with evidence from others concluding that transport to the abattoir represents an important source of contamination (53–55), our findings support that transport to the abattoir represents an important source of contamination.

In the current study, subtyping data could be used to assess the degree to which C. jejuni emanating from birds entering the abattoir contributes to the subsequent contamination of meat within the processing environment by contrasting the subtypes observed on birds prior to entering the abattoir to subtypes observed on meat destined for retail. Within the abattoir, we observed many instances where the same subtype responsible for a barn outbreak was subsequently found on meat from birds originating from the barn. However, we also observed a conspicuous increase in the diversity of C. jejuni subtypes associated with meat and the contamination of meat with subtypes that were never observed in the barns. Moreover, contamination was observed on meat from birds that were deemed free of C. jejuni after transport to the abattoir. Transfer of Campylobacter from a positive flock to broiler carcasses of a subsequently slaughtered negative flock has been observed previously (56). In the current study, barn outbreaks were rare and incited by a limited number of C. jejuni subtypes, suggesting that much of the subtype diversity observed on birds and on meat postprocessing may be due to significant contamination occurring at the abattoir. Although we observed a low prevalence of positive flocks, a large number of flocks are processed at the abattoir sampled in the current study; on average, ≈2.2 million birds are processed per month, with broilers from 2 to 5 separate barns processed per day.

In many instances, birds that we longitudinally examined represented the first flock to be possessed at the abattoir (i.e., after implementation of industry standard sanitization), and thus our findings suggest the possibility for contamination via a “resident” population of C. jejuni subtypes within the abattoir. Whether these C. jejuni subtypes are ephemerally present (e.g., escaping sanitation but not persisting for prolonged periods) or long-term residents (e.g., existing in biofilms within the abattoir environment) is not known at present. A variety of studies have shown that C. jejuni isolates are common within the abattoir environment (57). However, this issue has not been examined through a comprehensive assessment of isolates within abattoirs at a subtype level of resolution. Thus, it is unknown whether previous observations of C. jejuni present at the abattoir level potentially represent resident subtypes. Some C. jejuni subtypes have demonstrated a capacity to persist extraintestinally (52), and whether certain subtypes are able to persist within abattoirs as a result of enhanced ability to survive warrants examination.

We observed that the diversity of C. jejuni subtypes on meat at retail was similar relative to that observed on meat in the abattoir, and we observed that only a subset of subtypes recovered from meat in both the abattoir and at retail were also detected in human infections during the study period. Many studies have linked C. jejuni from poultry to human infections (58), but this has not previously been done in a model location with intensive longitudinal sampling comprising the multiple stages of the chicken production continuum concurrently performed with human clinical surveillance. The subtyping data on the large collection of C. jejuni isolates obtained during the course of the current study indicate that the abattoir is the primary point at which chickens destined for retail become contaminated by diverse C. jejuni subtypes, which are then transferred to people living in SWA through handling of raw poultry meat or via consumption of undercooked poultry contaminated with the bacterium. It is noteworthy that in the current study, whole birds were transferred from the abattoir to a major local retailer who provided us with samples during the processing of individual birds (i.e., at entry into retail processing). Thus, our study did not examine transfer and/or persistence of C. jejuni strains during the retail process (e.g., from handling, placement in packaging, and during storage), which could represent an additional transfer point (57).

In several instances, we observed C. jejuni subtypes that were observed in barn outbreaks and contaminating poultry meat in the abattoir that are strongly associated with beef cattle based on epidemiological evidence in the C3GFdb. Rates of campylobacteriosis in SWA (44) are consistently higher than the provincial and national rates (59), although the reasons are not established. Poultry consumption habits are similar across the province of Alberta, suggesting that poultry contamination is unlikely to be the primary driver for the elevated rates of campylobacteriosis observed in the region. Southwestern Alberta is a region with diverse and intensive livestock agriculture; during any given period, there are 2.7 million chickens and 1.2 million beef cattle in SWA, with 51% of the cattle in confined feeding operations (60). Occupational contact with cattle has been identified as a risk factor for infection by C. jejuni in the region (61). In addition, we have recently shown that cattle are frequently colonized by diverse C. jejuni subtypes, with many of the subtypes infecting people in SWA primarily associated with beef cattle (44), which are continuously released in large numbers into the environment in cattle feces (62, 63). However, our work has also indicated that consumption of beef does not present a significant risk of campylobacteriosis (62, 64), suggesting limited direct transmission from cattle to people in SWA. Similarly, although infections resulting from the consumption of inadequately treated surface water contaminated with C. jejuni originating from beef cattle have been reported elsewhere in Canada (65), this is not considered to be an important direct transmission route in SWA. The fact that many of the C. jejuni strains recovered from poultry in the current study were associated with beef cattle in SWA may indicate that cattle serve as an important reservoir of subtypes transmitted to broilers and which subsequently infect people via consumption of contaminated poultry.

In summary, we longitudinally examined the transmission of C. jejuni at a subtype level of resolution in the broiler production continuum using a model agroecosystem located in SWA. In broiler barns, the occurrence of C. jejuni was a rare event but could rapidly escalate to contamination of the entire flock late during the production cycle once the bacterium gained access to a barn. Even when more than one C. jejuni subtype was present in a barn, a single subtype was responsible for outbreaks. The prevalence of contamination and diversity of C. jejuni subtypes increased along the chicken production continuum, with some birds only exposed to the bacterium during transport to the abattoir. Evidence indicated that birds from a relatively small number of barns contaminate transport trucks and the abattoir with C. jejuni strains, which are then collectively transferred to a majority of the birds within the abattoir and end up on poultry products destined for retail. Moreover, C. jejuni subtypes responsible for outbreaks and contaminating meat within the abattoir were predominantly associated with cattle. Thus, beef cattle appear to be an important reservoir of strains contaminating broiler chickens in SWA, which are subsequently transmitted throughout the poultry production continuum. Thus, our data suggest that an important transmission pathway that must be considered in the development of mitigation strategies is from beef cattle to chickens in broiler barns, to abattoirs, to meat, and to human beings via consumption of poultry meat.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics approvals.

Approval to obtain cloacal samples from birds and mice was obtained from the Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) Lethbridge Research and Development Centre (LeRDC) Animal Care Committee (ACC) before commencement of sample collection (LeRDC ACC Animal Use Protocol number 1615). Approval to transfer Campylobacter isolates from the CRH to AAFC LeRDC was obtained from the University of Lethbridge Office of Research Ethics (Certificate of Human Subject Research number 715) and the University of Alberta Research Ethics Office (Health Research Ethics Board number Pro00094238). Information that was transferred with the isolates was restricted to the isolate identifier and the year of isolation. No information that could reveal the identity of the individual originally submitting the stool sample for diagnosis was disclosed to research personnel. The AAFC LeRDC is licensed by the Public Health Agency of Canada to conduct research with risk group 2 pathogens, for which Campylobacter spp. are designated. Approval to transfer the isolates from the CRH to LeRDC was obtained from the AAFC and Alberta Health Services biological safety officers.

Sample collection.

All cycles (chick placement to slaughter) were sampled at three commercial broiler farms in SWA over a 1.5-year period (i.e., farm A, B, and C) (see Fig. S9 in the supplemental material); the same barn was sampled at each farm. The three barns selected were representative of broiler production barns in SWA. Samples were collected from (i) the barn environment before placement of the chicks, (ii) transport papers after the release of the chicks into barns, (iii) the barn environment and birds each week after placement of the chicks within the barns, (iv) birds after transport to the abattoir at which they were processed, (v) poultry within the abattoir, and (vi) poultry at retail (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). To collect the environmental samples (i.e., air, floors, walls, feed, water, litter, insects, and mice), the interior of each chicken barn was divided into six sections. Campylobacter jejuni on the surfaces of floors and walls was determined weekly. Sterile sponges within the Whirl-Pak Speci-Sponge bags (Whirl-Pak, Madison, WI) moistened with Columbia broth (Oxoid Canada, Nepean, ON) were used to swab arbitrarily selected 100-cm2 areas of the wall and floor (litter removed) in each of the six sampling sections. Sponges were replaced into Whirl-Pak Speci-Sponge bags (Whirl-Pak) and sealed for transport to the laboratory. Litter (≈5 g) was collected weekly from the six sampling sections and placed in sterile tubes for transport. Additional environmental samples (e.g., feed, beetle larvae and adults, flies, and air) were obtained from each of three sections weekly (far left, center, and far right). Feed (≈5 g) was obtained from arbitrarily selected feeding trays. Beetle larvae and adults were exposed by manually removing litter, collecting larvae and adults with sterile forceps, and placing them collectively in separate tubes by location for transport; a maximum of 10 individuals were obtained per subsample. Adult flies were collected in six containers (250 ml) filled with ham, tomato juice, and water. Flies were individually removed with forceps and placed in sterile tubes for transport; a maximum of 10 individual flies were obtained per subsample. Campylobacter jejuni in air was determined using an inertia-type microbial air sampler (MAS-100; Millipore Canada Ltd, Etobicoke, ON) operated at 100 liters of air per min for a 10-min test period. Particles in air were deposited directly onto KA (Oxoid Canada) with selective supplement SR0167 (KSA; Oxoid Canada) in a Petri dish placed in the sampler. A single feed sample (≈5 g) was also obtained before distribution to birds, and an individual water sample (2 liters) was collected from the end of one pipeline weekly. Air and fly samples were also obtained from three designated locations outside and adjacent to each barn. Mice in the barn and adjacent feed room were trapped using live traps (Victor model number M333; Amazon) baited with peanut butter. Samples from floors, walls, litter, air, and beetles were obtained from barns after they were sanitized and before they were populated with birds. The total number of environmental samples collected per barn per week was ≥38 (see Table S2).

At the time of population of the barns with 1-day-old chicks, 20 arbitrarily selected and soiled chick transport papers were obtained. Samples were also obtained each week from 75 arbitrarily selected live birds via cloacal miniswabs (catalog number 22029571; Fisher Scientific Company, Ottawa, ON). To obtain cloacal swabs, birds were humanely immobilized by one worker, while another worker gently inserted the miniswab moistened with sterile Columbia broth into the vent and rotated it until it was covered with feces. The miniswab was then placed in an individual tube containing 3 ml of Columbia broth for transport. For some of the cycles in barn A and barn B, a subsample of excreted feces was collected from the surface of litter with a sterile spatula and placed in tubes for transport. Digesta from ceca was obtained from a minimum of 15 cull birds each week. Cull birds were placed in bags, transported to the necropsy facility at AAFC LeRDC where the abdominal cavity was opened with sterile instruments to expose the cecum, individual ceca were aseptically removed and incised, and a subsample of digesta was removed, placed in a sterile tube, and maintained on ice for transport to the laboratory. During the last 2 weeks of each production cycle, feather samples were collected from a maximum of 15 cull birds.

At the end of each production cycle, birds from the barns sampled in the current study were followed to the abattoir at which they were processed (see Fig. S9), and subsamples of feathers and skin were obtained. For transport, birds were humanely captured by trained personnel, placed in communal crates, and transported to the abattoir (<20 km) according to industry standards (e.g., humane transport of birds and sanitation of crates and trucks). Feathers and cecal digesta samples were obtained from birds that died during transport from the barns to the abattoir and processed; cecal digesta was obtained following the same procedure as described above for cull birds. The total number of samples obtained from the abattoir per barn per week was ≥180. At 10 sample times throughout the study period (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), skin samples from the cloacal region (n = 25) and breast (n = 25) of carcasses were provided by a retailer who obtains chicken from the abattoir at which the birds in the current study were processed.

Sample processing.

Samples were processed the same day as collection (i.e., typically within 4 h of collection). For floor and wall samples, sponges within the Whirl-Pak Speci-Sponge bags (Whirl-Pak) were filled with 50 ml of sterile Columbia broth, homogenized using a Smasher (bioMérieux Canada, Inc., Saint-Laurent, QC) for 1 min (normal speed), and the homogenate was centrifuged for 10 min at 14,900 × g. Immediately after centrifugation, the supernatant was removed to a final volume of 3 ml, and the remaining liquid was vortexed to resuspend bacterial cells within the pellet. Feed samples and litter samples (5 g) were individually placed into a BagPage bag containing a microperforated filter (Interscience, Woburn, MA), and sterile Columbia broth (25 ml) was added to the sample (i.e., 1:5 dilution). The sample was then homogenized using the Smasher (bioMérieux Canada) for 1 min (normal speed), and broth on the nonfeed/nonlitter side of the microperforated filter was collected. Drinking water samples (2 liters) were individually filtered through a Whatman glass microfiber filter (55-mm diameter; Whatman Inc., NJ) under vacuum to remove large particulate matter, and then through a Supor 200 PES membrane disc filter (47-mm diameter, 0.2-µm pore size; Pall Corporation, Port Washington, NY). The Supor filters were vigorously vortexed (high setting for 3 min) in 15 ml Columbia broth to release any bacterial cells on the filter surface. The Columbia broth was centrifuged at 14,900 × g for 10 min to sediment any bacterial cells, and immediately after centrifugation, the supernatant was removed to a final volume of 3 ml. The remaining liquid was vortexed to resuspend bacterial cells within the pellet. Beetle larvae and adults and flies were each placed into a 2-ml tube, homogenized with a polypropylene minimortar and pestle (Fisher Scientific Company) in 1.5 ml of Columbia broth. Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (isoflurane USP; Fresenius Kabi, Toronto, ON) and humanely euthanized under anesthesia by cervical dislocation. The cecum was exposed by laparotomy, removed, and incised, and cecal contents were collected and weighed. Columbia broth was added to the sample at a 1:10 dilution, and samples were vortexed for 1 min (high setting).

Individual soiled chick transport papers (42.5 cm by 59.5 cm) were folded and placed into the BagPage filter bag (Interscience). For every 16-cm2 surface area of the transport papers, 100 ml of Columbia broth was added, the paper was homogenized using the Smasher (bioMérieux Canada) for 2 min (high speed), and a subsample of the liquid on the nonpaper side of the microperforated filter was collected. Cloacal miniswabs in Columbia broth were vortexed for 1 min (high setting). Cecal digesta and feces were weighed, Columbia broth was added at a 1:10 dilution, and samples were vortexed for 1 min (high setting). Feathers were weighed, placed in a BagPage filter bag (Interscience), and Columbia broth added at a 1:6 dilution. The samples were then homogenized with the Smasher (bioMérieux Canada) for 1 min (normal speed), and liquid on the nonfeather side of the microperforated filter was collected. For skin samples, 25 g of each sample was placed into the BagPage filter bag (Interscience), Columbia broth added at a 1:4 dilution, samples homogenized with the Smasher (bioMérieux Canada) for 1 min (normal speed), and liquid on the nonskin side of the microperforated filter collected.

Isolation of Campylobacter jejuni.

Two isolation methods were applied for most samples, which included nonselective enrichment followed by membrane filtration and direct plating onto KSA. For enrichment, 500 µl of each sample was added to 4.5 ml of an enrichment broth containing Bolton broth (Oxoid Canada) with 5% laked horse blood and 10 mg liter−1 amphotericin (10 mg liter−1) and trimethoprim (5 mg liter−1) (BAT) in 100- by 16-mm culture tubes. Tubes were incubated for 48 h at 37°C in a microaerobic atmosphere, and 200 µl of each enrichment broth was spread centrally onto a sterile 47-mm-diameter filter with 0.45-µm pores positioned on the surface of KA. After 15 min, the filter was aseptically removed taking care to ensure that enrichment broth remained on the filter, and KA cultures were incubated at 37°C in a microaerobic atmosphere for 48 h. For direct plating (all samples with the exception of air samples, for which air was impacted directly onto KSA), 25 µl of each sample was spread onto KSA in duplicate, and cultures were maintained in the microaerobic atmosphere at 42°C for 48 h. For air samples, KSA in Petri dishes from the MAS-100 air sampler were placed directly in the microaerobic atmosphere at 42°C for 48 h. Presumptive Campylobacter colonies (maximum of five colonies per culture) were streaked for purity on KA, and cell size, morphology, and motility characteristics of Campylobacter were used to select isolates for further characterization. Isolates were stored in Columbia broth containing 40% glycerol at −80°C.

Campylobacter jejuni isolates from diarrheic humans.

All isolates of C. jejuni isolated from diarrheic humans in SWA by CRH staff during the study period (n = 164) were transferred to AAFC LeRDC under an existing transfer agreement. Information provided with the isolates was limited to the date of collection. In addition, C. jejuni isolates infecting people in SWA provided by the CRH outside of the study period from 2004 to 2017 were included as reference strains (e.g., to identify CRS associated with poultry).

Identification of Campylobacter jejuni.

Genomic DNA from presumptive Campylobacter isolates was extracted using an Autogen 740 robot (Holliston, MA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Extracted DNA was subjected to diagnostic PCR for Campylobacter genus targeting the 16S rRNA gene using the primers (C412F, 5′-GGATGACACTTTTCGGAGC-3′ and C1228R, 5′-ATAAAAGACTATCGTCGCGTG-3′) (66). DNA was also subjected to species-specific PCR using two primer sets targeting the lpxA gene (lpxACjejuniF, 5′-ACAACTTGGTGACGATGTTGTA-3′ and lpxARKK2m, 5′-CAATCATGDGCDATATGASAATAHGCCAT-3′) (67) and the hipO gene (CjHipOF, 5′-AAATAGGAAAAACAGGCGTTGT-3′ and CjHipOR, 5′-TATCATTAGCCTGTGCAAGACC-3′). Amplification reactions consisted of 2.0 µl of 10× PCR buffer, 0.4 µl of 25 mM MgCl2 (Qiagen Inc., Montreal, QC), 2.0 µl of bovine serum albumin (BSA) (1.0 mg ml−1; Life Technologies Inc., Burlington, ON), 0.4 µl of 10 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP) (Bio Basic Canada Inc., Markham, ON), 0.1 µl of HotStar Taq DNA polymerase (5.0 U µl−1; Qiagen Inc.), 1.0 µl each of forward and reverse primer (10 µM) (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA), 2.0 µl DNA template, and 11.1 µl nuclease free water (Qiagen Inc.). The PCR conditions were as follows: one initial denaturation cycle at 95°C for 5 min, 35 cycles of 30 s at 94°C for denaturation, 1 min 30 s at the appropriate annealing temperature (Ta), 1 min at 72°C for annealing, and a final 10-min extension cycle at 72°C for extension. The Ta for the Ipx primers was 50°C, and Ta for the HipO primers was 60°C. Amplicons were run on a 1% Tris-acetate-EDTA (TAE) agarose gel to detect positive samples relative to negative and positive controls. For confirmed Campylobacter isolates in which taxon-specific PCR was indefinite, the near complete 16S rRNA gene of these isolates was sequenced, and sequence data was compared to reference sequences within GenBank (National Center for Biotechnology Information, Bethesda MD) using blastn.

Genotyping.

Representative isolates of C. jejuni were genotyped using high-throughput comparative genomic fingerprinting (CGF) (42); this method targets 40 accessory genes that are distributed throughout the C. jejuni chromosome to generate a high-resolution binary fingerprint. In CGF, every unique fingerprint is given a 10-digit designation (e.g., aaaa.bbb.ccc) with three hierarchical levels: the first set of digits (i.e., aaaa) represents the 90% similarity level, the second set of digits (i.e., bbb) represents the 95% similarity level, and the third set (i.e., ccc) represents the 100% similarity level. We used the “0957.001 cluster” designation to define the family of 0957.001.xxx fingerprints (e.g., 0957.001.001, 0957.001.002, 0957.001.003, etc.), which would be expected to be >95% and <100% similar. A single isolate per sample positive for C. jejuni was genotyped. The total number of isolates genotyped was 1,018, including 496 from broiler barns, 240 from the abattoir, 117 from retail meat, and 164 from diarrheic humans. To facilitate epidemiological contextualization of the subtyping data, we obtained trends on the historical, geographical, and source distribution of each fingerprint from the Canadian Campylobacter Comparative Genomic Fingerprinting Database (C3GFdb).

Analyses.

Most analyses were conducted using Statistical Analyses Software (SAS; Cary, NC). In order to determine if significant count shifts occurred among the two sample times, the Genmod nonparametric procedure from SAS was used. When a significant treatment effect was observed, the least-squares mean was used to evaluate differences among means of interest. To analyze subtype diversity of C. jejuni, isolates were assigned to CGF subtype clusters using the simple matching analysis coefficient with unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA) clustering in Bionumerics (version 6.6; Applied Maths, Austin, TX). Randomized resampling was performed to normalize sample size, and cluster richness and abundance were used to calculate the Shannon diversity index. Hutcheson’s t test was used to test the significance of differences in subtype diversity (68). Population structures were visualized as minimum spanning trees (MSTs) using Bionumerics (version 6.6; Applied Maths). Venn diagrams of subtypes between sample types were generated using pivot tables at a 95% level of resolution, including subtypes recovered from diarrheic humans and chickens isolated in SWA outside of the study period and accessioned within the C3GFdb. For comparisons with all isolates within the C3GFdb, CGF profiles were queried against those in the C3GFdb (i.e., C. jejuni isolates recovered nationally).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the dedicated assistance provided by the following individuals at AAFC LeRDC: Tara Shelton, Kathaleen House, Hannah Scott, Kaylie Graham, Quinn Matthews, and Shaylene Montgomery-Vanchuck for weekly collection of samples; Kathaleen House, Tara Shelton, Jenny Gusse, Quinn Matthews, Hannah Scott, Kaylie Graham, Shaylene Montgomery-Vanchuck, Andrew Webb, Maximo Lange, Danisa Bescucci, Andrew Webb, and Kirsty Brown for processing samples; Kathaleen House, Tara Shelton, Jenny Gusse, Quinn Matthews, and Hannah Scott for isolation and identification of C. jejuni isolates; Andrew Webb and Jenny Gusse for fingerprinting isolates by CGF; Andrew Webb for developing custom molecular epidemiological analysis tools; and Jenny Gusse for conducting epidemiological analyses. We are grateful to staff at the CRH (Department of Laboratory Medicine) who provided clinical strains of C. jejuni, and to Robert Renema (Alberta Chicken Producers) who facilitated access to broiler barns and to the abattoir at which the birds were processed. Special thanks are extended to the three broiler producers, the abattoir management and operators, and the poultry retailer who facilitated access to samples. We would also like to acknowledge the many contributors to the C3GFdb and the constructive comments from the anonymous reviewers of the manuscript.

Financial support was provided by grants from the Canadian Poultry Research Council—Poultry Science Cluster (project 1374; Activity 11), the Alberta Livestock and Meat Agency (project 2015E002R), AAFC (project 1679), and Genome Alberta (A3GP60).

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Public Health Agency of Canada. 2018. Notifiable diseases online, Government of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. https://diseases.canada.ca/notifiable/. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alberta Government. 2011. Campylobacteriosis - public health notifiable disease management guidelines - 2011. Alberta Health and Wellness, Edmonton, AB, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaakoush NO, Castano-Rodriguez N, Mitchell HM, Man SM. 2015. Global epidemiology of Campylobacter infection. Clin Microbiol Rev 28:687–720. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00006-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas MK, Murray R, Flockhart L, Pintar K, Pollari F, Fazil A, Nesbitt A, Marshall B. 2013. Estimates of the burden of foodborne illness in Canada for 30 specified pathogens and unspecified agents, circa 2006. Foodborne Pathog Dis 10:639–648. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2012.1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Inglis GD, Boras VF, Houde A. 2011. Enteric campylobacteria and RNA viruses associated with healthy and diarrheic humans in the Chinook Health Region of southwestern Alberta, Canada. J Clin Microbiol 49:209–219. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01220-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Platts-Mills JA, Kosek MN, Allos BM, Blaser MJ. 2020. Campylobacter species. Antimicrobe, Pittsburgh, PA: http://www.antimicrobe.org/b91.asp. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keithlin J, Sargeant J, Thomas MK, Fazil A. 2014. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the proportion of Campylobacter cases that develop chronic sequelae. BMC Public Health 14:1203. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engberg J, Aarestrup FM, Taylor DE, Gerner-Smidt P, Nachamkin I. 2001. Quinolone and macrolide resistance in Campylobacter jejuni and C. coli: resistance mechanisms and trends in human isolates. Emerg Infect Dis 7:24–34. doi: 10.3201/eid0701.010104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silva J, Leite D, Fernandes M, Mena C, Gibbs PA, Teixeira P. 2011. Campylobacter spp. as a foodborne pathogen: a review. Front Microbiol 2:200. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taylor EV, Herman KM, Ailes EC, Fitzgerald C, Yoder JS, Mahon BE, Tauxe RV. 2013. Common source outbreaks of Campylobacter infection in the USA, 1997–2008. Epidemiol Infect 141:987–996. doi: 10.1017/S0950268812001744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Revez J, Llarena AK, Schott T, Kuusi M, Hakkinen M, Kivisto R, Hanninen ML, Rossi M. 2014. Genome analysis of Campylobacter jejuni strains isolated from a waterborne outbreak. BMC Genomics 15:768. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wagenaar JA, French NP, Havelaar AH. 2013. Preventing Campylobacter at the source: why is it so difficult? Clin Infect Dis 57:1600–1606. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ravel A, Hurst M, Petrica N, David J, Mutschall SK, Pintar K, Taboada EN, Pollari F. 2017. Source attribution of human campylobacteriosis at the point of exposure by combining comparative exposure assessment and subtype comparison based on comparative genomic fingerprinting. PLoS One 12:e0183790. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Canadian Food Inspection Agency. 2016. National microbiological baseline study in broiler chicken (December 2012–December 2013). Canadian Food Inspection Agency, Ottawa, ON, Canada: https://www.inspection.gc.ca/food-safety-for-industry/chemical-residues-microbiology/food-safety-testing-bulletins/2016-08-17/december-2012-december-2013/eng/1471358115567/1471358175297. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cox NA, Richardson LJ, Maurer JJ, Berrang ME, Fedorka-Cray PJ, Buhr RJ, Byrd JA, Lee MD, Hofacre CL, O'Kane PM, Lammerding AM, Clark AG, Thayer SG, Doyle MP. 2012. Evidence for horizontal and vertical transmission in Campylobacter passage from hen to her progeny. J Food Prot 75:1896–1902. doi: 10.4315/0362-028.JFP-11-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]