Abstract

Study Objectives:

Idiopathic central sleep apnea (ICSA) is a rare disorder diagnosed when known causes of central sleep apnea are excluded. No established treatments exist for ICSA, and long-term studies are lacking. We assessed the long-term effectiveness and safety of transvenous phrenic nerve stimulation in patients with ICSA.

Methods:

In the remedē System Pivotal Trial, 16/151 (11%) participants with central sleep apnea were diagnosed as having ICSA. Patients were implanted and followed through 18 months of active therapy. Polysomnograms obtained at baseline and at 6, 12, and 18 months were scored by a central laboratory. Sleep metrics and patient-reported quality of life outcomes were assessed.

Results:

Patients experienced moderate-severe central sleep apnea. The baseline AHI, central apnea index, and arousal index were 40, 25, and 32 events/h of sleep, respectively. These metrics improved at 6, 12, and 18 months of therapy: the AHI decreased by 25, 25, and 23 events/h (P < .001 at each visit), the central apnea index by 22, 23, and 22 events/h (P < .001 at each visit), and the arousal index by 12 (P = .005), 11 (P = .035), and 13 events/h (P < .001). Quality of life instruments showed clinically meaningful improvements in daytime somnolence, fatigue, general and mental health, and social functioning. The only related serious adverse event was lead component failure in 1 patient.

Conclusions:

This is the longest prospective study for the treatment of ICSA. Transvenous phrenic nerve stimulation significantly decreased sleep-disordered breathing metrics with consequent improvement in quality of life at 6 months, and all benefits were sustained through 18 months.

Clinical Trial Registration:

Registry: ClinicalTrials.gov; Name: Respicardia, Inc. Pivotal Trial of the remedē System; URL: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01816776; Identifier: NCT01816776.

Citation:

Javaheri S, McKane S. Transvenous phrenic nerve stimulation to treat idiopathic central sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2020;16(12):2099–2107.

Keywords: idiopathic central sleep apnea, transvenous phrenic nerve stimulation, quality of life

BRIEF SUMMARY

Current Knowledge/Study Rationale: No established treatments exist for idiopathic central sleep apnea, and long-term studies are lacking. This study of transvenous phrenic nerve stimulation is the only long-term therapeutic study in patients diagnosed with idiopathic central sleep apnea.

Study Impact: The results suggest that over the course of 18 months, transvenous phrenic nerve stimulation improves sleep-disordered breathing metrics and quality of life of patients with idiopathic central sleep apnea. Transvenous phrenic nerve stimulation could be considered a long-term option for treatment of idiopathic central sleep apnea.

INTRODUCTION

Idiopathic central sleep apnea (ICSA) is a rare disorder that is diagnosed when all other known causes of central sleep apnea (CSA) are excluded.1,2 The mechanism underlying ICSA is increased controller gain related to increased chemosensitivity to carbon dioxide.3 Because ICSA is one small subset of the uncommon CSA disorder, large prospective randomized studies of ICSA are difficult to perform and no established long-term treatments exist. However, multiple therapeutic options including PAP devices,4–7 use of inhaled carbon dioxide,8,9 oral acetazolamide,10,11 and oral zolpidem12,13 have been tried in short-term studies. No prospective long-term study regarding the effectiveness and effects of therapy on quality of life (QoL) has been reported.

The remedē System, a fully implantable unilateral transvenous phrenic nerve stimulation (TPNS) device, is a U.S. Food & Drug Administration–approved treatment option for adults with moderate to severe CSA consisting of an implantable pulse generator, a stimulation lead, and an optional sensing lead. The stimulation lead is implanted in the left pericardiophrenic or right brachiocephalic vein and works by stimulating a single phrenic nerve to move the diaphragm, generating negative intrathoracic pressure similar to natural breathing throughout the night. The device applies TPNS therapy automatically once the time is within the preprogrammed sleeping hours and the patient is inactive and reclined past the programmed sleeping angle (recumbent), providing full adherence. The initial pivotal trial enrolled patients with any CSA etiology except opioid-induced CSA.14,15 The majority of the patients in the trial had heart failure or other cardiovascular diseases; however, a small subgroup was identified as having ICSA. In this study we report long-term therapy of ICSA with TPNS in a small number of patients.

METHODS

The remedē System Pivotal Trial enrolled adult patients with moderate to severe CSA.14,15 Briefly, the entry criteria required an AHI of at least 20 events/h sleep, the presence of at least 30 central apneas, and the central apneas accounting for ≥ 50% of all apneas. The obstructive apnea index had to be ≤ 20% of the total AHI. All polysomnograms were scored centrally.

The subset of participants with ICSA met the following additional criteria:

No known cardiovascular disease including coronary disease, heart failure, or arrhythmias (history of hypertension was not exclusionary)

Echocardiography showing normal left ventricular ejection fraction and absence of significant diastolic dysfunction (posterior wall thickness ≤ 1.2 cm, E/A ratio between > 0.8 and < 2.0)

No opioid use

Absence of Hunter-Cheyne-Stokes breathing

All patients were implanted with the TPNS device (remedē System, Respicardia, Inc., Minnetonka, MN), which was activated in patients in the treatment arm after 1 month and patients in the control arm after 6 months (the first 6 months were part of a randomized controlled trial). However, for the purpose of this analysis, the groups were pooled based on months of active therapy. In-laboratory attended polysomnography (PSG) was performed at baseline and at 6, 12, and 18 months of active therapy to assess sleep metrics. All PSGs were scored by a central core laboratory (Registered Sleepers, Leicester, NC) as previously described.14,15 QoL was assessed by the patient global assessment and Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) through 12 months of active therapy. Additional exploratory QoL instruments assessed were the Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS), the 12-item short-form quality of life survey (SF-12), and the EuroQOL EQ-5D-5L.

The investigational plan was approved by local ethics or institutional review boards, and all patients provided written informed consent. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, Good Clinical Practice, and ISO-14155:2011 and was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01816776).

Visit results and changes from baseline to 6, 12, and 18 months of active therapy were calculated for continuous endpoints, along with the nominal 2-sided P value from the Wilcoxon signed rank test for changes from baseline. In this exploratory analysis, nominal P values < .05 were considered statistically significant and no adjustments were made to control for multiple testing. Categorical variable results are presented as the percentage of patients, and continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation for baseline characteristics and median (25th percentile, 75th percentile) for endpoints. Patients with complete data were included in efficacy analyses. Safety was assessed by serious adverse events related to the implant procedure, device, or delivered therapy through 12 months. SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) was used for all analyses.

RESULTS

In the remedē System Pivotal Trial,14,15 11% of the patients (16 of 151) were identified as having ICSA and were followed through 18 months posttherapy activation; 2 of the patients had ICSA but did not reach 18 months (1 unrelated death because of myelodysplastic syndrome and 1 device explant after lead failure). Baseline characteristics for the 14 patients are reported in Table 1. The mean age was 51 ± 14 years, the mean body mass index was 31 ± 4 kg/m2, and 93% of the patients were male. Four patients were taking at least 1 medication that can affect sleep, including zolpidem, trazodone, temazepam, alprazolam, quetiapine, and hydroxyzine. Six patients were taking antidepressants, and 2 were taking modafinil. There were 3 patients with medication changes after start of therapy. Temazepam and zaleplon were prescribed for 2 patients. In the third patient, the sertraline dose was increased from 50 mg/d to 75 mg/d.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics.

| Baseline Characteristics | Percentage or Mean (n = 14) |

|---|---|

| Male | 13 (93%) |

| Age (y) | 51 ± 14 |

| Height (cm) | 179 ± 9 |

| Weight (kg) | 100 ± 16 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 31 ± 4 |

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 82 ± 21 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 129 ± 9 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 82 ± 9 |

| Hypertension | 6 (43%) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 5 (36%) |

Continuous variables reported as mean ± standard deviation and categorical display n (%).

The most common self-reported symptoms at baseline were insomnia (5/14 patients), fatigue (7/14 patients), excessive daytime sleepiness (ESS > 10; 9/14 patients), and depression (7/14 patients).

Sleep metrics

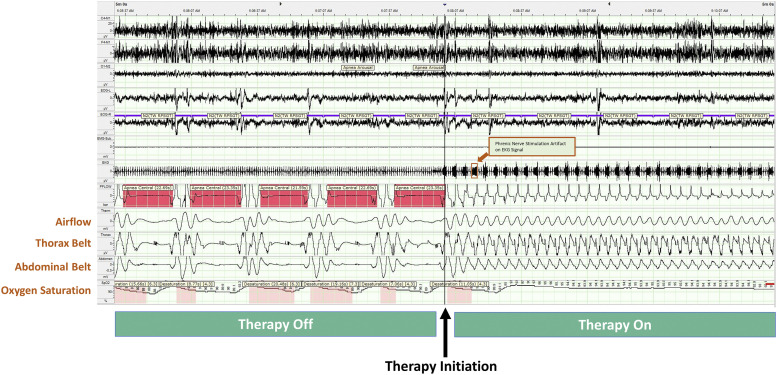

Sleep epochs for a patient with untreated ICSA (left side of Figure 1) illustrate a pattern of breathing with ICSA. This pattern is quite different from the crescendo-decrescendo breathing pattern (Hunter-Cheyne-Stokes breathing) often associated with congestive heart failure. The right side of Figure 1 shows the elimination of CSA with TPNS.

Figure 1. Phrenic nerve stimulation on/off in ICSA.

Example of a 5-minute segment of sleep from a polysomnogram showing epochs of sleep for a patient with ICSA. The left side (Therapy Off) shows the pattern of sleep with central apnea events before initiation of therapy; the pattern looks very different than the Cheyne-Stokes respiration pattern associated with CSA in patients with heart failure. The right side (Therapy On) shows the immediate cessation of central apneas and the resumption of normal sleep when TPNS therapy is turned on. CSA = central sleep apnea, ICSA = idiopathic central sleep apnea, TPNS, transvenous phrenic nerve stimulation.

Sleep metric results are displayed in Table 2. Patients had severe sleep apnea at baseline, with a median AHI of 40 (30–63) events/h of sleep. Central apneas accounted for the majority of the events, with a median of 25 (12–38) events/h. In these ICSA participants, the median obstructive apnea index was 1 (0–4) events/h, the mixed apnea index was 1 (0, 8) events/h, and the hypopnea index was 10 (3– 15) events/h. AHI improved by –25 (–46 to –18) events/h (P < .001) to 11 (6–16) events/h at 6 months, and the improvement was maintained at 12 months (12 [8–18] events/h; P < .001) and 18 months (19 [8–25] events/h; P < .001; Figure 2). The improvement in AHI was primarily from a reduction in the central apnea index, which was lowered to 3 (1–5) events/h at 6 months, 2 (1–3) events/h at 12 months and 1 (0–3) events/h at 18 months (all P < .001). The obstructive apnea index was not significantly different from baseline and remained low, with a median obstructive apnea index of 1–2 events/h at each follow-up (P > 0.3). The arousal index (ArI) decreased by a median of 11–13 events/h at 6, 12, and 18 months (P ≤ 0.035 at each visit; Figure 2).

Table 2.

Polysomnogram sleep metrics.

| Endpoint (n = 14) | Baseline | 6 Months of Therapy | 12 Months of Therapy | 18 Months of Therapy | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Result | Change From Baseline | Result | Change From Baseline | Result | Change From Baseline | ||

| AHI (events/h) | 40 (30–63) | 11 (6–16) | –25 (–46 to –18); P < .001 | 12 (8–18) | –25 (–40 to –9); P < .001 | 19 (8–25) | –23 (–40 to –9); P < .001 |

| CAI (events/h) | 25 (12–38) | 3 (1–5) | –22 (–33 to –9); P < .001 | 2 (1–3) | –23 (–38 to –10); P < .001 | 1 (0–3) | –22 (–35 to –9); P < .001 |

| OAI (events/h) | 1 (0–4) | 1 (0–2) | 0 (–2 to 1); P = .691 | 2 (0–3) | 0 (–1 to 2); P = .561 | 2 (1–5) | 1 (–1 to 3); P = .349 |

| MAI (events/h) | 1 (0–8) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (–8 to 0); P = .055 | 0 (0–0) | 0 (–8 to 0); P = .004 | 0 (0–0) | 0 (–8 to 0); P = .012 |

| HI (events/h) | 10 (3–15) | 7 (1–12) | –1 (–11 to 5); P = .288 | 7 (3–17) | –2 (–10 to 2); P = .681 | 11 (5–18) | 0 (–3 to 5); P = .703 |

| ODI4 (events/h) | 33 (22–61) | 11 (4–19) | –21 (–36 to –1); P = .001 | 11 (6–28) | –17 (–34 to –3); P = .009 | 20 (6–23) | –18 (–35 to –5); P = .002 |

| ArI (events/h) | 32 (26–48) | 16 (13–23) | –12 (–30 to –8); P = .005 | 21 (13–29) | –11 (–25 to –4); P = .035 | 16 (11–27) | –13 (–22 to –8); P < .001 |

| Min of sleep with oxygen saturation < 90% (min) | 18 (6–49) | 5 (2–40) | –4 (–25 to 2); P = .079 | 4 (1–30) | –6 (–27 to 0); P = .041 | 12 (5–42) | –9 (–32 to 7); P = .163 |

| Percentage of sleep with oxygen saturation < 90% (%) | 5 (2–12) | 2 (1–10) | 0 (–3 to 2); P = .542 | 2 (0–14) | –1 (–7 to 1); P = .303 | 4 (1–17) | –2 (–5 to 2); P = .473 |

| Percentage of sleep in N1 (% of sleep) | 29 (15–38) | 21 (12–28) | –6 (–20 to 6); P = .135 | 27 (18–36) | –3 (–7 to 5); P = .626 | 21 (12–35) | –6 (–15 to 3); P = .153 |

| Percentage of sleep in N2 (% of sleep) | 52 (47–53) | 54 (49–67) | 6 (–5 to 15); P = .241 | 49 (47–55) | 0 (–3 to 4); P > .99 | 57 (48–70) | 10 (–5 to 18); P = .058 |

| Percentage of sleep in N 33 (% of sleep) | 5 (1–9) | 9 (2–13) | 1 (–1 to 5); P = .296 | 6 (1–14) | 1 (–1 to 4); P = .274 | 1 (0–8) | 0 (–5 to 1); P = .435 |

| Percentage of sleep in REM (% of sleep) | 15 (10–19) | 16 (13–21) | 1 (–5 to 4); P = .952 | 15 (6–22) | 0 (–5 to 7); P = .808 | 18 (13–21) | –2 (–5 to 8); P = .915 |

Median (Q1–Q3). Nominal 2-sided P value from Wilcoxon signed rank test for change from baseline to visit. ArI = arousal index, CAI = central apnea index, HI = hypopnea index, MAI = mixed apnea index, OAI = obstructive apnea index, ODI4 = oxygen desaturation index (4%).

Figure 2. Polysomnogram sleep metrics by visit.

Sleep indices from overnight, attended PSG for the subgroup of patients with ICSA. Indices with Wilcoxon signed rank test nominal 2-sided P value < .05 for change from baseline at each follow-up visit are identified with *. ArI = arousal index, CAI = central apnea index, HI = hypopnea index, ICSA = idiopathic central sleep apnea, MAI = mixed apnea index, OAI = obstructive apnea index, ODI4 = oxygen desaturation index (4%), PSG = polysomnography.

QoL metrics

The ESS, a validated 24-point scale, consists of 8 items measuring daytime sleepiness; values above 10 points suggest excessive daytime sleepiness.16 The median ESS value was 14 (8–18) points at baseline and improved to a median of 7 (3–15) points at 6 months and 7 (4–11) points at 12 months (P ≤ .002 at each visit; Table 3 and Figure 3).

Table 3.

QoL metrics.

| Endpoint (n = 14) | Baseline | 6 Months | 12 Months | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Result | Change From Baseline | Result | Change From Baseline | ||

| ESS (points)a | 14 (8–18) | 7 (3–15) | –4 (–6 to –2); P = .002 | 7 (4–11) | –7 (–7 to –3); P = .001 |

| Marked or moderate improvement in PGAb | Not applicable | Not applicable | 6 (43) | Not applicable | 10 (71) |

aMedian (Q1–Q3). Nominal 2-sided P value from Wilcoxon signed rank test for change from baseline to visit. bReported as n (%). ESS = Epworth Sleepiness Scale, PGA = patient global assessment, QoL = quality of life.

Figure 3. QoL.

QoL improved with phrenic nerve stimulation. The ESS and FSS are used at the left (black) y axis; the EQ-5D is used at the right (red) y axis. The median ESS improved from > 10 points, which indicates excessive daytime sleepiness, to < 10 points at each visit with TPNS therapy. The median FSS improved from > 4 points, which indicates fatigue, to < 4 points at each visit with TPNS therapy. The median EQ-5D showed minimal change after 6 months of therapy, but a statistically significant improvement (to the best health state) was observed at 12 months. ESS = Epworth Sleepiness Scale, FSS = Fatigue Severity Scale, QoL = quality of life, TPNS = transvenous phrenic nerve stimulation.

The FSS is a validated metric consisting of 7 items encompassing a scale of 0–7, where values ≥ 4 indicate self-reported fatigue.17 The median FSS total score improved from 4.1 (3.4–4.8) at baseline to 3.0 (2.1–4.2; P = .003) at 6 months and 2.9 (2.2–3.6; P = .003) at 12 months (Table 4 and Figure 3).

Table 4.

Exploratory QoL metrics.

| Endpoint (n = 14) | Baseline | 6 Months of Therapy | 12 Months of Therapy | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Result | Change From Baseline | Result | Change From Baseline | ||

| FSS (score) | 4.1 (3.4–4.8) | 3.0 (2.1–4.2) | –0.9 (–2.0 to –0.4); P = .003 | 2.9 (2.2–3.6) | –1.1 (–1.6 to –0.2); P = .003 |

| SF-12 Mental component score (score) | 48 (41–54) | 51 (44–58) | 3 (0–6); P = .135 | 53 (48–58) | 5 (0–9); P = .127 |

| SF-12 Vitality (score) | 44 (39–49) | 49 (49–59) | 5 (0–10); P = .121 | 54 (49–59) | 10 (0–10); P = .106 |

| SF-12 Role—emotional (score) | 48 (46–56) | 46 (41–56) | 0 (–5 to 0); P = .438 | 51 (46–56) | 3 (–5 to 5); P = .377 |

| SF-12 General health (score) | 48 (34–58) | 48 (34–58) | 0 (0–10); P = .688 | 58 (48–58) | 3 (0–10); P = .016 |

| SF-12 Social functioning (score) | 57 (48–57) | 57 (48–57) | 0 (0–0); P > .99 | 57 (48–57) | 0 (0–9); P = .828 |

| SF-12 Mental health (score) | 47 (41–53) | 53 (47–58) | 6 (0–11); P = .012 | 53 (47–58) | 6 (–6 to 11); P = .164 |

| SF-12 Physical component score (score) | 53 (43–56) | 53 (50–54) | 0 (–3 to 3); P = .808 | 55 (50–56) | 2 (–1 to 2); P = .244 |

| SF-12 Physical functioning (score) | 53 (41–57) | 57 (41–57) | 0 (0–0); P = .813 | 57 (49–57) | 0 (0–8); P = .063 |

| SF-12 Role—physical (score) | 49 (41–57) | 49 (45–57) | 0 (–4 to 4); P = .447 | 53 (41–57) | 2 (0–4); P = .219 |

| SF-12 Bodily pain (score) | 58 (49–58) | 58 (49–58) | 0 (0–9); P = .375 | 58 (49–58) | 0 (–9 to 9); P = .738 |

| EQ-5D Index (index) | 0.851 (0.820–0.876) | 0.869 (0.820–1.000) | 0.056 (–0.015 to 0.139); P = .509 | 1.000 (0.820–1.000) | 0.094 (0.000–0.139); P = .006 |

| EQ-5D Visual Analog Scale (points) | 82.5 (80.0–90.0) | 80.0 (65.0–90.0) | 1.0 (–13.0 to 10.0); P = .800 | 85.0 (75.0–90.0) | 2.5 (–5.0 to 10.0); P = .668 |

Median (Q1–Q3). Nominal 2-sided P value from Wilcoxon signed rank test for change from baseline to visit. FSS = Fatigue Severity Scale, QoL = quality of life, SF-12 = 12-item short-form survey.

Comparing the ESS and FSS at baseline, approximately half of the patients scored above the abnormal threshold in 1 metric but not the other. However, the baseline FSS correlated with the baseline ESS (Pearson correlation = 0.59). Notably, nearly all patients improved on both measures; however, the correlation for change from baseline between the ESS and FSS at 6 months of therapy was poor (Pearson correlation = 0.25), suggesting a lack of relationship between the level of improvement in the ESS and FSS.

The patient global assessment,18 a patient-reported outcome questionnaire, asked “Specifically in reference to your overall health, how do you feel today as compared to how you felt before having your device implanted?” with 7 response levels: markedly improved, moderately improved, mildly improved, no change, slightly worse, moderately worse, or markedly worse. At 6 months, 43% (6/14) of patients reported a moderate or marked improvement in the patient global assessment, and the results further improved to 71% (10/14) of patients at 12 months (Table 3), similar to the 67% rate for the full population. No patients reported worsening at either visit.

The 12-item short-form survey, a validated QoL instrument that measures general health functioning, has 2 component scores (mental and physical) and 8 domain scores, where 50 is the U.S. population norm and higher scores are better.19 The mental component score showed nonstatistically significant improvements, from 48 (41–54) at baseline to 51 (44–58; P = .135) and 53 (48–58) points (P = .127) at 6 and 12 months, respectively (Table 4 and Figure 4). The domains for vitality, general health, and mental health all showed increases on therapy, some from < 50 (population norm) to > 50. The physical component score showed minimal changes (P > .063 for each endpoint at each visit).

Figure 4. SF-12 component and domain scores.

The SF-12 mental component, physical component, and 8 domain scores are displayed by visit; a score of 50 is considered the U.S. population norm. Statistically significant improvements were observed for general health at 12 months and for mental health at 6 months. None of the scores showed a significant worsening with therapy. SF-12 = 12-item short-form survey.

The EQ-5D20 provides a simple descriptive profile and a single index value for health status. The EQ-5D self-reported questionnaire includes a visual analog scale that records the respondent’s self-rated health status on a graduated (0–100) scale, with higher scores for higher health-related QoL. It also includes the EQ-5D descriptive system, which comprises 5 dimensions of health: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression. The visual analog scale provides a direct valuation of the respondent’s current state of health, whereas the descriptive system can be used as a health profile or converted into an index score representing a von Neumann-Morgenstern utility value for current health (scale –0.109 to 1, higher is better). The index score improved by a median of 0.056 (–.015 to 0.139; P = .509) and 0.094 (0.000–0.139; P = .006) over 6 and 12 months, respectively (Table 4 and Figure 3).

After 12 months of active therapy, patients were asked if they would elect to have this medical device implanted again, and all 14 patients with ICSA patients responded “yes.”

Safety

None of the 14 patients diagnosed with ICSA and completing follow-up reported a serious adverse event related to the implant procedure, device, or delivered therapy through 18 months. However, 1 control patient experienced a stimulation lead failure before therapy activation; the patient elected to have the device explanted rather than replaced and did not continue with the study.

DISCUSSION

We report the first prospective long-term therapeutic study of adult patients with ICSA. The patients experienced moderate-severe sleep apnea and were treated with unilateral TPNS for up to 18 months. Sleep metrics and patient-reported QoL improved significantly with TPNS therapy.

ICSA is a rare disease of unknown etiology. The true demographics and prevalence of ICSA in the general population are not known but within a sleep center population, the prevalence has been reported to be 4%–7% of patients with CSA.21,22 In the current study, among 151 consecutive patients with PSG findings of CSA, 16 (11%) were diagnosed with ICSA.

ICSA occurs across all ages including adults21,22 and children,23 most often in middle-aged to elderly individuals, and more commonly in men than in women. Our findings are supportive: 93% of the cohort were men with an average age of 53 years. The most common symptoms in patients with ICSA are insomnia, fatigue, excessive daytime sleepiness, and depression,22 consistent with our findings in that several patients were taking hypnotics, antidepressants, and wake-promoting medications.

ICSA is typically categorized in the group of hypocapnic CSA, with a high chemical loop gain and exaggerated hypercapnic ventilatory response.24 Consequently, during sleep, arousals are followed by augmented hyperventilation, resulting in a transient drop in the partial pressure of carbon dioxide crossing the apneic threshold and leading to CSA.2 Being quite a rare disorder, ICSA has had no prospective long-term therapeutic study reported and no uniformly accepted therapeutic option, although both pharmacological and PAP therapy have been tried.

CSA because of heart failure is also mediated by high loop gain25,26; it is well known that inhaled carbon dioxide and added dead space to increase the arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide just sufficiently to prevent the occurrence of transient hypocapnia, regardless of the magnitude of any ventilatory overshoot, effectively treats CSA associated with heart failure.27 Two small studies in ICSA have shown similar results. In 3 male patients with ICSA, Szollosi and colleagues9 showed that increasing end-tidal carbon dioxide by 2–4 mm Hg decreased AHI significantly, but unfortunately without reducing the ArI. Similarly, in an overnight PSG study in 6 male patients with ICSA, Xie, Rankin, and colleagues8 increased the transcutaneous partial pressure of carbon dioxide by 1–3 mm Hg via administration of a carbon dioxide–enriched gas mixture or addition of dead space, virtually eliminating apneas and hypopneas. The reduction in the movement ArI was not significant. In the current study with TPNS, the ArI decreased significantly in parallel to the reduction in the central apnea index (Table 2 and Figure 2).

Acetazolamide is a respiratory stimulant that acts by decreasing the plant gain, lowering the overall loop gain.2 It has been shown to improve CSA in heart failure,28 spinal cord injury,29 and ICSA. White and colleagues10 administered acetazolamide to 6 male patients with CSA. Sleep studies were carried out before and after 1 week of drug therapy, during which time the mean arterial pH decreased from 7.42 to 7.34. All 6 patients had significant improvement in sleep-disordered breathing, with a 70% reduction in total apneas. The ArI decreased significantly from 22 events/h before treatment to 8 events/h after treatment using acetazolamide. Five of the 6 patients reported better-quality sleep and decreased daytime sleepiness. Similar results were obtained by DeBacker and colleagues11 after 1 month of therapy with single-dose acetazolamide before bedtime in 14 patients with ICSA.

Based on the interaction between arousals and hyperventilation, hypnotics have been used to treat CSA.12,13 In the largest observational study so far, Quadri and colleagues12 treated 20 patients with 10 mg zolpidem before bedtime for 9 weeks. The follow-up polysomnograms showed significant reductions in AHI, central apnea index, and ArI with consequent improvement in self-reported daytime sleepiness. However, despite significant improvement in sleep-disordered breathing, arterial oxygen saturation did not improve. In addition, OSA increased on zolpidem, generally slightly, in 7 of the 20 patients.

Although PAP devices including CPAP, bilevel, and adaptive servo-ventilation are used for patients with CSA, few data exist specific to patients with ICSA, and no long-term data are available. CPAP has been shown to reduce AHI after 1 month of therapy.30 The most effective PAP therapy is thought to be adaptive servo-ventilation. Kouri and colleagues31 have used adaptive servo-ventilation with success in some patients with ICSA. However, no prospective studies have been identified in the literature. Given patients’ overall poor adherence to PAP devices, PAP therapy may not be an effective long-term choice. The current study, the longest patient follow-up known so far, used unilateral TPNS with virtually 100% adherence. In the current posthoc observational analysis, PSG metrics showed persistent improvement after 6, 12, and 18 months of TPNS therapy. In contrast to some other therapeutic options discussed above, CSA improved with a consequent reduction in arousals and desaturation across 18 months of follow-up.

We examined several health-related QoL metrics longitudinally. Patients reported improved daytime sleepiness, fatigue, mental health, and an overall global QoL.

When asked if they would undergo the procedure again to receive this therapy, all 14 patients affirmed that they would.

The natural history of ICSA and its potentially unrecognized causes remain to be fully evaluated. A few studies have suggested that the presence of CSA may result from the unrecognized presence of asymptomatic cardiocerebrovascular disorders, only to herald the future occurrence of disorders such as atrial fibrillation, heart failure, stroke, or REM sleep behavior disorder. In the Multicenter Outcomes of Sleep Disorders in Older Men Study,32 842 older (>65) men underwent PSG and were followed for an average of 6.5 years. After adjustments were made for established risk factors, those with CSA at baseline were 2.6 times more likely to develop atrial fibrillation than those without CSA. In another prospective study33 of 2,865 community-dwelling older men 65 or older who underwent baseline PSG and were followed for a mean of 7.3 years, elevated CSA was significantly associated with increased risk of development of clinical heart failure.

In a prospective population-based study34 of 394 stroke-free elderly (70 or older) patients who underwent PSG and were followed for 6 years, 20 ischemic strokes occurred. Event-free survival was shorter in the group with the highest CAI, an association independent of any other vascular risks. Another study35 suggested that the presence of CSA heralds REM sleep behavior disorder.

The aforementioned studies are consistent with those of Kouri and colleagues.31 In their observational retrospective study of 25 patients with ICSA, incident arrythmias (4 patients, 16%), heart failure (2 patients, 8%), and cognitive impairment/dementia with Lewy bodies (5 patients, 20%) were prevalent. Most unexpected was death in 6 (25%) patients (median time to death = 5 years; interquartile range = 4.8). We emphasize that the demographics of their patients were similar to those in our study. Notably, patients with heart failure and arrhythmias were excluded from the present cohort. And fortunately, none of our patients died during the trial.

Regarding limitations and strengths, this retrospective analysis from the remedē System Pivotal Trial consists of a small number of patients with ICSA; however, this disorder is rare, and to date all studies have been observational with small numbers of patients and limited follow-up. Carbon dioxide levels were not measured during the baseline study, and therefore not all patients in this analysis may have been hypocapneic. Observational studies, such as the current one, are subject to bias and must be confirmed by randomized controlled trials.

The strengths of the study include the inclusion of consecutive patients with ICSA, the central scoring of multiple PSGs, the long-term follow-up, and the collection of a variety of QoL metrics.

CONCLUSIONS

This 18-month retrospective analysis indicates that TPNS improves CSA and associated arousals and desaturation in patients with ICSA. Moreover, health-related patient-reported outcomes using validated metrics showed improved QoL including fatigue, daytime sleepiness, and mental health. As a result of the potential to improve sleep and QoL, phrenic nerve stimulation may be considered a long-term option for treatment of ICSA.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

All authors have contributed to, reviewed, and approved the manuscript. This trial was funded by Respicardia. The authors have the following conflicts of interest to declare. Javaheri: consulting fees from Respicardia. McKane: statistician as an employee of Respicardia.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AHI

apnea-hypopnea index

- ArI

arousal index

- CAI

central apnea index

- CSA

central sleep apnea

- ESS

Epworth Sleepiness Scale

- FSS

Fatigue Severity Scale

- ICSA

idiopathic central sleep apnea

- PSG

polysomnography

- QoL

quality of life

- TPNS

transvenous phrenic nerve stimulation

REFERENCES

- 1.Javaheri S. Elliott M.Central Sleep Apnoea. In: Elliott M, Nava S, Schönhofer B, eds. Non-Invasive Ventilation and Weaning: Principles and Practice. 2nd ed. Boca Raton, FL, New York, NY, London, UK: Taylor & Francis Group; 2019: 408–418. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Javaheri S, Dempsey JA. Central sleep apnea. Compr Physiol. 2013;3(1):141–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xie A, Rutherford R, Rankin F, Wong B, Bradley TD. Hypocapnia and increased ventilatory responsiveness in patients with idiopathic central sleep apnea. Am J.Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152(6 Pt 1):1950–1955. 10.1164/ajrccm.152.6.8520761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Issa FG, Sullivan CE. Reversal of central sleep apnea using nasal CPAP. Chest. 1986;90(2):165–171. 10.1378/chest.90.2.165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoffstein V, Slutsky AS. Central sleep apnea reversed by continuous positive airway pressure. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987;135(5):1210–1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hommura F, Nishimura M, Oguri M, et al. Continuous versus bilevel positive airway pressure in a patient with idiopathic central sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155(4):1482–1485. 10.1164/ajrccm.155.4.9105099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Banno K, Okamura K, Kryger MH. Adaptive servo-ventilation in patients with idiopathic Cheyne-Stokes breathing. J Clin Sleep Med. 2006;2(2):181–186. 10.5664/jcsm.26514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xie A, Rankin F, Rutherford R, Bradley TD. Effects of inhaled CO2 and added dead space on idiopathic central sleep apnea. J Appl Physiol. 1997;82(3):918–926. 10.1152/jappl.1997.82.3.918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Szollosi I, Jones M, Morrell MJ, Helfet K, Coats AJ, Simonds AK. Effect of CO2 inhalation on central sleep apnea and arousals from sleep. Respiration. 2004;71(5):493–498. 10.1159/000080634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.White DP, Zwillich CW, Pickett CK, Douglas NJ, Findley LJ, Weil JV. Central sleep apnea. Improvement with acetazolamide therapy. Arch Intern Med. 1982;142(10):1816–1819. 10.1001/archinte.1982.00340230056012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeBacker WA, Verbraecken J, Willemen M, Wittesaele W, DeCock W, Van deHeyning P. Central apnea index decreases after prolonged treatment with acetazolamide. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;151(1):87–91. 10.1164/ajrccm.151.1.7812578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quadri S, Drake C, Hudgel DW. Improvement of idiopathic central sleep apnea with zolpidem. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5(2):122–129. 10.5664/jcsm.27439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grimaldi D, Provini F, Vetrugno R, et al. Idiopathic central sleep apnoea syndrome treated with zolpidem. Neurol Sci. 2008;29(5):355–357. 10.1007/s10072-008-0995-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Costanzo MR, Augostini R, Goldberg LR, Ponikowski P, Stellbrink C, Javaheri S. Design of the remedē System Pivotal Trial: a prospective, randomized study in the use of respiratory rhythm management to treat central sleep apnea. J Card Fail. 2015;21(11):892–902. 10.1016/j.cardfail.2015.08.344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Costanzo MR, Ponikowski P, Javaheri S, et al. Transvenous neurostimulation for central sleep apnoea: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;388(10048):974–982. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30961-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep. 1991;14(6):540–545. 10.1093/sleep/14.6.540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krupp LB, LaRocca NG, Muir-Nash J, Steinberg AD. The fatigue severity scale. Application to patients with multiple sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Neurol. 1989;46(10):1121–1123. 10.1001/archneur.1989.00520460115022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guy W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Rev. ed. U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare publication. Rockville, MD:National Institute of Mental Health; 1976 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ware J, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SDA. A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220–233. 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rabin R, de Charro F. EQ-5D: a measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Ann Med. 2001;33(5):337–343. 10.3109/07853890109002087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eckert DJ, Jordan AS, Merchia P, Malhotra A. Central sleep apnea: Pathophysiology and treatment. Chest. 2007;131(2):595–607. 10.1378/chest.06.2287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Academy of Sleep Medicine . Primary Central Sleep Apnea. In: International Classification of Sleep Disorders. 3rd ed. Darien, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2014:89–93. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gurbani N, Verhulst SL, Tan C, Simakajornboon N. Sleep complaints and sleep architecture in children with idiopathic central sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13(6):777–783. 10.5664/jcsm.6614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xie A, Wong B, Phillipson EA, Slutsky AS, Bradley TD. Interaction of hyperventilation and arousal in the pathogenesis of idiopathic central sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150(2):489–495. 10.1164/ajrccm.150.2.8049835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Javaheri S. A mechanism of central sleep apnea in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(13):949–954. 10.1056/NEJM199909233411304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Solin P, Roebuck T, Johns DP, Walters EH, Naughton MT. Peripheral and central ventilatory responses in central sleep apnea with and without congestive heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162(6):2194–2200. 10.1164/ajrccm.162.6.2002024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomas RJ. Alternative approaches to treatment of central sleep apnea. Sleep Med Clin. 2014;9(1):87–104. 10.1016/j.jsmc.2013.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Javaheri S. Acetazolamide improves central sleep apnea in heart failure: a double-blind, prospective study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173(2):234–237. 10.1164/rccm.200507-1035OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sankari A, Vaughan S, Bascom A, Martin JL, Badr MS. Sleep-disordered breathing and spinal cord injury: a state-of-the-art review. Chest. 2019;155(2):438–445. 10.1016/j.chest.2018.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Verbraecken J, Willemen M, Wittesaele W, Van de Heyning P, De Backer W. Short-term CPAP does not influence the increased CO2 drive in idiopathic central sleep apnea. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2002;57(1):10–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kouri I, Kolla BP, Morgenthaler TI, Mansukhani MP. Frequency and outcomes of primary central sleep apnea in a population-based study. Sleep Med. April 2020;68:177–183. 10.1016/j.sleep.2019.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.May AM, Blackwell T, Stone PH, et al. Central sleep-disordered breathing predicts incident atrial fibrillation in older men. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(7):783–791. 10.1164/rccm.201508-1523OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Javaheri S, Blackwell T, Ancoli-Israel S, Ensrud KE, Stone KL, Redline S. Sleep-disordered breathing and incident heart failure in older men. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(5):561–568. 10.1164/rccm.201503-0536OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muñoz R, Durán-Cantolla J, Martinez-Vila E, et al. Central sleep apnea is associated with increased risk of ischemic stroke in the elderly. Acta Neurol Scand. 2012;126(3):183–188. 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2011.01625.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garcia-Sanchez A, Fernandez-Navarro I, Garcia-Rio F. Central apneas and REM sleep behavior disorder as an initial presentation of multiple system atrophy. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016;12(2):267–270. 10.5664/jcsm.5500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]