In this study, we assess the prevalence and onset timing of co-occurring chronic conditions in a cohort of children with NI enrolled in Medicaid.

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Children with neurologic impairment (NI) are at risk for developing co-occurring chronic conditions, increasing their medical complexity and morbidity. We assessed the prevalence and timing of onset for those conditions in children with NI.

METHODS:

This longitudinal analysis included 6229 children born in 2009 and continuously enrolled in Medicaid through 2015 with a diagnosis of NI by age 3 in the IBM Watson Medicaid MarketScan Database. NI was defined with an existing diagnostic code set encompassing neurologic, genetic, and metabolic conditions that result in substantial functional impairments requiring subspecialty medical care. The prevalence and timing of co-occurring chronic conditions was assessed with the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Chronic Condition Indicator system. Mean cumulative function was used to measure age trends in multimorbidity.

RESULTS:

The most common type of NI was static (56.3%), with cerebral palsy (10.0%) being the most common NI diagnosis. Respiratory (86.5%) and digestive (49.4%) organ systems were most frequently affected by co-occurring chronic conditions. By ages 2, 4, and 6 years, the mean (95% confidence interval [CI]) numbers of co-occurring chronic conditions were 3.7 (95% CI 3.7–3.8), 4.6 (95% CI 4.5–4.7), and 5.1 (95% CI 5.1–5.2). An increasing percentage of children had ≥9 co-occurring chronic conditions as they aged: 5.3% by 2 years, 10.0% by 4 years, and 12.8% by 6 years.

CONCLUSIONS:

Children with NI enrolled in Medicaid have substantial multimorbidity that develops early in life. Increased attention to the timing and types of multimorbidity in children with NI may help optimize their preventive care and case management health services.

What’s Known on This Subject:

The consequences of neurologic impairment (NI) extend beyond the nervous system. Much of the morbidity and mortality of children with NI arises from co-occurring chronic conditions.

What This Study Adds:

In children with NI, multiple co-occurring chronic conditions were prevalent by age 6 years. Digestive, respiratory, and mental health problems were common. One in 8 children experienced the highest degree of multimorbidity measured with 9 or more chronic conditions.

Neurologic impairment (NI) arises from a heterogeneous group of static and progressive diseases that affect the central and peripheral nervous systems. Example NI diagnoses include cerebral palsy, spina bifida, and trisomy 18. As the nervous system regulates end-organ and physiologic systems, manifestations of these diseases often extend beyond neurologic dysfunction. Resultant dysfunction of other organ systems may result in co-occurring chronic conditions, including digestive, respiratory, and musculoskeletal problems.1–6 Much of the morbidity and mortality of children with NI arises from these co-occurring chronic conditions.6–8

To optimize the health and well-being of children with NI, screening and proactive management is important to detect, monitor, and treat these co-occurring chronic conditions.9–11 Moreover, it is paramount to counsel the families of children with NI on the likelihood of experiencing co-occurring chronic conditions, including when they are most likely to arise in their children’s lives. Knowledge on the timing and trajectory of these co-occurring chronic conditions is lacking and may help improve upstream care planning and care coordination to help maximize the healthy growth, development, and lives of children with NI.12–20

We conducted the current study to advance knowledge about the development of co-occurring chronic conditions in children with NI early in life. Our first study aim was to assess the prevalence and timing onset of co-occurring chronic conditions, including how they increase in number with age. Our second study aim was to assess variation in the total number of co-occurring chronic conditions with increasing age across NI subtypes.

Methods

Study Design, Population, and Setting

This is a retrospective longitudinal analysis of the IBM Watson Medicaid MarketScan Database, 2009–2015, which contains Medicaid health care claims across the care continuum for Medicaid enrollees from 12 US states. Children born in 2009 with an NI diagnosis in the first 3 years of life were included if they were continuously enrolled in Medicaid through the study period (ie, 11 of 12 months yearly through age 6).

NI was defined as “a neurological diagnosis reasonably expected to last longer than 12 months and result in substantial functional impairments that require subspecialty medical care.”7 The diagnosis of NI was identified with an established set of International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) diagnosis codes used in previous studies.7,21,22 NI subtypes included genetic and/or metabolic (eg, trisomy 21), progressive (eg, metachromatic leukodystrophy), peripheral (eg, muscular dystrophy), anatomic (eg, myelodysplasia), stroke and/or hemorrhage, and static (eg, cerebral palsy). Because children may have multiple NI diagnoses, a hierarchy was established by the study team through group consensus to assign each child to 1 primary NI subtype to allow for us to examine differences across subtypes. The hierarchy prioritized categorization of children to specific NI diagnoses on the basis of the likelihood of primary etiology (eg, a child with cerebral palsy due to an intracranial hemorrhage was categorized in the stroke and/or hemorrhage subtype). The final hierarchy used in this study was genetic and/or metabolic, progressive, peripheral, anatomic, stroke and/or hemorrhage, and static.

Main Outcome Measures

The main outcome measures of interest were the prevalence and onset timing of co-occurring chronic conditions. Those conditions were assessed with the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality open-source, publicly available diagnosis classification schemes, the Chronic Condition Indicator and the Clinical Classification System (CCS),23 adapted for use in pediatric patients.24 The Chronic Condition Indicator classifies ∼14 000 ICD-9 codes as chronic or not chronic. The CCS is a clinically comprehensive map that assigns every ICD-9 code to exactly 1 common chronic condition category.23,25 The CCS also assigns each chronic condition code to 1 of 25 mutually exclusive categories organized by organ system.23,25 For example, constipation, dysphagia, and gastroesophageal reflux disease were grouped as digestive system conditions. NI diagnoses used to define the study cohort were not included in the neurologic system condition category. Diagnostic codes from all encounters were examined.

The onset timing of co-occurring chronic conditions was assessed by age in months. Onset was defined for each Medicaid enrollee as the first occurrence of the diagnostic code listed within any health care claim across the continuum (eg, outpatient primary or specialty care visit, hospitalization, emergency department visit, etc), including the birth hospitalization.

Additional Patient Characteristics

Patient demographic characteristics assessed included age, sex, race and/or ethnicity, Medicaid enrollment criteria (disability versus other), and Medicaid plan type (fee for service versus managed care).

Statistical Analysis

The total number of co-occurring chronic conditions accumulated by age 6 years and the onset timing of individual co-occurring chronic conditions were compared across NI subtypes by using Wilcoxon rank tests. The mean cumulative function (MCF) was used to assess trends in the total number of co-occurring chronic conditions with increasing age (through age 6 years). The MCF is a nonparametric staircase analysis used to estimate (with 95% confidence bounds) the accrued number of occurrences of a recurrent event, such as the accumulation of the number of co-occurring chronic conditions over time. The MCF of the total number of co-occurring chronic conditions was estimated for the study population overall as well as for each NI subtype. SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC) was used, and the statistical significance threshold was P < .05 for all analyses.

Results

Characteristics of the Study Population

Of the 6229 children with NI included for analysis, 54.3% were male and 45.6% were non-Hispanic white (Table 1). Most children were enrolled in Medicaid through the disability pathway (83.4%) and were in Medicaid managed care (67.0%). The median age at the first NI diagnosis was 4.1 months (interquartile range [IQR] 0.2–11.1 months).

TABLE 1.

Demographic Characteristics of the Study Population

| Characteristic | Overall | Subtype of NI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic and/or Metabolic | Progressive | Peripheral | Anatomic | Static | Stroke and/or Hemorrhage | ||

| N (%) | 6229 | 1423 (22.8) | 25 (0.4) | 147 (2.4) | 1355 (21.7) | 2579 (41.4) | 700 (11.2) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 3380 (54.3) | 749 (52.6) | 13 (52.0) | 68 (46.3) | 725 (53.5) | 1441 (55.9) | 384 (54.9) |

| Race and/or ethnicity, n (%) | |||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 2842 (45.6) | 680 (47.8) | 11 (44.0) | 70 (47.6) | 597 (44.0) | 1241 (48.1) | 243 (34.7) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1713 (27.5) | 325 (22.8) | 6 (24.0) | 38 (25.9) | 431 (31.8) | 670 (2.6) | 243 (34.7) |

| Hispanic | 669 (10.7) | 144 (10.1) | 3 (12.0) | 13 (8.8) | 94 (6.9) | 366 (14.2) | 49 (0.07) |

| Other | 1005 (16.1) | 274 (19.3) | 5 (20.0) | 26 (17.7) | 233 (17.1) | 302 (11.7) | 165 (23.5) |

| Medicaid plan | |||||||

| FFS | 2055 (33) | 579 (40.6) | 8 (32.0) | 61 (41.4) | 433 (31.9) | 708 (27.4) | 266 (38.0) |

| MMC | 4174 (67) | 844 (59.3) | 17 (68.0) | 86 (58.5) | 922 (68.0) | 1871 (72.5) | 434 (62.0) |

| Enrollment | |||||||

| Disability | 5193 (83.4) | 1173 (82.4) | 17 (68.0) | 128 (87.1) | 1147 (84.6) | 2134 (82.7) | 594 (84.8) |

| Other | 502 (8.1) | 138 (9.7) | 4 (16.0) | 13 (8.8) | 131 (9.7) | 143 (5.5) | 73 (10.4) |

| Missing | 534 (8.6) | 112 (7.9) | 4 (16.0) | 6 (4.1) | 77 (5.7) | 302 (11.7) | 33 (4.7) |

| Age at first NI diagnosis, mo, median, (IQR) | 4.1 (0.2–11.1) | 1.1 (0–5.9) | 6.8 (3.3–21.2) | 5.9 (0–15.3) | 4.8 (0–11.9) | 7.3 (2.5–14.9) | 0 (0–2.5) |

| No. co-occurring chronic conditions by age 6 y, median, (IQR) | 5 (3–7) | 6 (4–9) | 7 (5–9) | 6 (5–8) | 6 (4–8) | 3 (2–5) | 5 (3–6) |

FFS, fee for service; MMC, Medicaid managed care.

The most common NI subtypes were static (41.4%), anatomic (21.7%), genetic and/or metabolic (22.8%), and stroke and/or hemorrhage (11.2%). Across all NI subtypes, cerebral palsy (10.0%), microcephaly (8.0%), and hydrocephalus (6.0%) were the most common diagnoses. The median age at first NI diagnosis varied significantly by NI subtype (P < .001). The stroke and/or hemorrhage NI subtype had the earliest age at first diagnosis (median 0 months [IQR 0–2.5 months]). The static NI subtype had the latest age at first diagnosis (median 7.3 months [IQR 2.5–14.9 months]). All NI subtypes had a median age at onset of ≤12 months.

Prevalence of Co-occurring Chronic Conditions

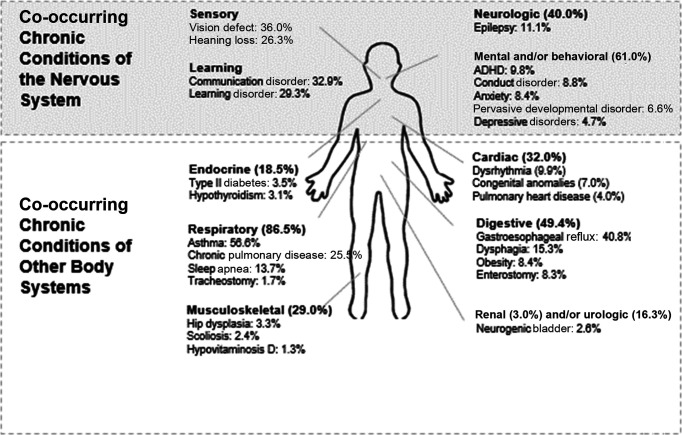

Neurologic co-occurring conditions (ie, neurologic diagnoses other than those used to define the study cohort) were commonly diagnosed by age 6 (39.8%) (Fig 1). More than 1 in 10 children (11.1%) had epilepsy. By age 6 years, 36.0% had received a diagnosis of vision defects and 26.3% had hearing loss identified. A communication disorder was diagnosed in 32.9%, and a learning disorder was diagnosed in 29.3%. The majority (61.0%) of children with NI also had a mental and/or behavioral health diagnosis, with the most common being attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (9.8%), conduct disorder (8.8%), and anxiety (8.4%). The prevalence of other notable mental health problems was 6.6% for pervasive developmental disorder and 4.7% for depression.

FIGURE 1.

Prevalence of co-occurring chronic conditions in children with NI by age 6 years. The percentages shown are of the total cohort of children with NI (n = 6229).

By age 6, co-occurring chronic conditions affecting nonneurologic organ systems were also commonly identified. Respiratory (86.5%) and digestive (49.4%) co-occurring chronic conditions had the highest prevalence. Across all organ systems, the most common co-occurring chronic conditions diagnosed were asthma (56.5%), gastroesophageal reflux (40.8%), and chronic respiratory insufficiency (25.5%). Enterostomy (ie, enteral feeding tubes) and tracheostomy were present in 8.3% and 1.7% of children, respectively, by age 6 years.

The prevalence of common co-occurring chronic conditions varied by NI subtype, as illustrated in Supplemental Fig 5.

Timing of Co-occurring Chronic Conditions

The co-occurring chronic conditions began accruing early in life (Fig 2). For example, the percentages of children with NI who had at least 1 co-occurring chronic condition identified at age 0 months, 1 year, and 6 years were 50.7%, 90.1%, and 99.0%, respectively.

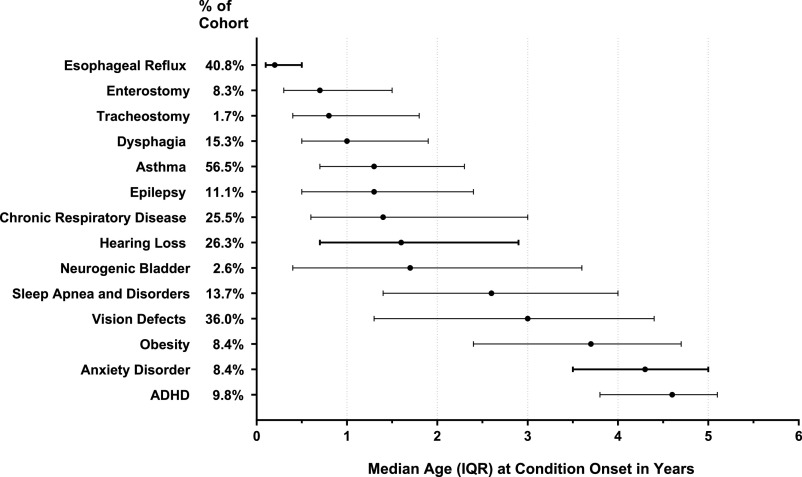

FIGURE 2.

Timing of first diagnosis of medical co-occurring chronic conditions present by age 6 years in children with NI. The percentages shown for “% of cohort” are of the total cohort of children with NI (n = 6229). Condition onset marks the first age when the diagnosis was made in a health care claim.

The timing of diagnosis of co-occurring chronic conditions varied across the conditions. For example, the timing was earlier for digestive co-occurring chronic conditions than for mental and/or behavioral health problems. The median ages at first diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease, enterostomy, and dysphagia in children with NI were 0.2 years (IQR 0.1–0.5 years), 0.7 years (IQR 0.3–1.5 years), and 1.0 years (IQR 0.5–1.9 years), respectively. In contrast, the median ages at first diagnosis of conduct disorder, anxiety, and ADHD were 3.9 years (IQR 2.9–4.7 years), 4.0 years (IQR 3.1–4.8 years), and 4.6 years (IQR 3.8–5.1 years), respectively.

The timing of common co-occurring chronic conditions varied by NI subtype, as illustrated in Supplemental Fig 5.

Multimorbidity

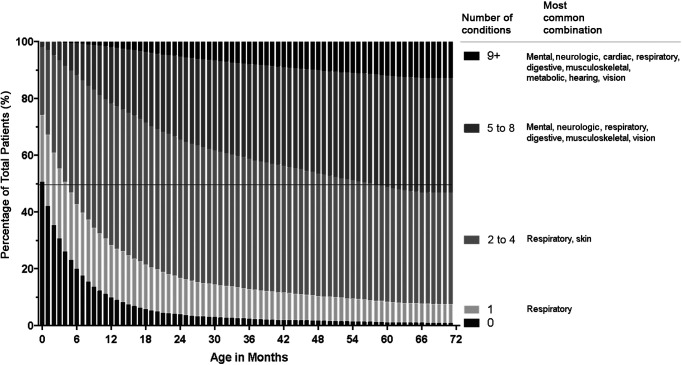

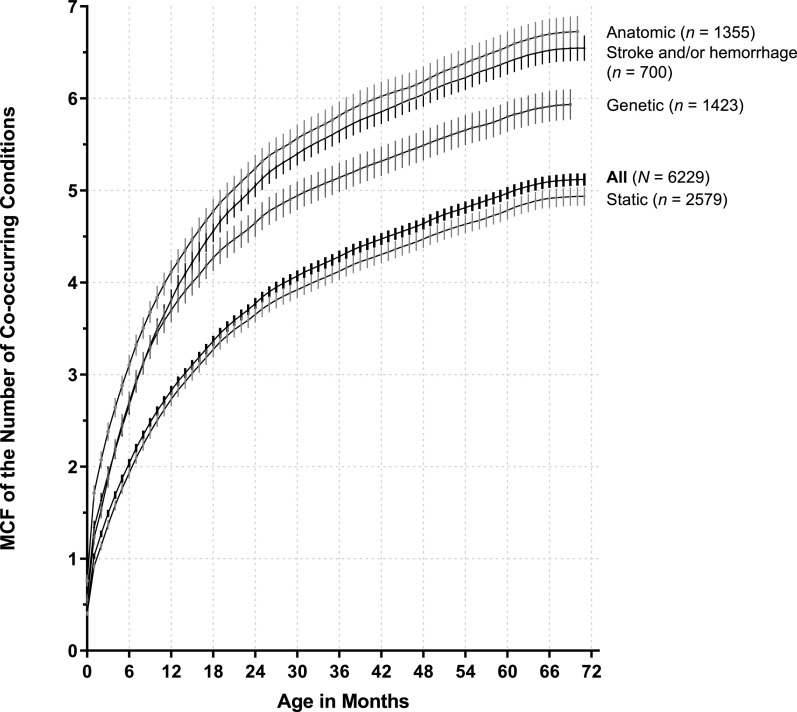

There was early development of multiple co-occurring chronic conditions among children with NI (Fig 3). By ages 2, 4, and 6 years, the mean numbers of co-occurring chronic conditions of children with NI were 3.7 (95% confidence interval [CI] 3.7–3.8), 4.6 (95% CI 4.5–4.7), and 5.1 (95% CI 5.1–5.2), respectively (Fig 4, Supplemental Fig 6). Among all children with NI, the most common multimorbidity combination at age 6 was respiratory, mental health, digestive, and vision problems, affecting 17.8% of all children in the cohort. Among children with NI with 2 to 4 co-occurring chronic conditions, respiratory and skin problems was the most common combination. Among children with NI with 5 to 8 co-occurring chronic conditions, digestive, mental health, musculoskeletal, respiratory, and vision problems was the most common combination.

FIGURE 3.

Trends in the number of co-occurring chronic conditions through age 6 years for children with NI. Presented on each stacked bar are the percentages of children with NI who, at the particular age in months, had 0, 1, 2 to 4, 5 to 8, and 9+ organ systems affected by their co-occurring chronic conditions. The number of such organ systems increases from bottom (ie, 0 systems) to top (9+ systems) on each bar. An example of findings is that the percentage of children with NI with 0 co-occurring conditions decreased from 50% at age 0 months to 4% at age 24 months and then to <1% by 72 months.

FIGURE 4.

Trends in the number of co-occurring chronic conditions through age 6 years for children with NI. The figure is a depiction of the MCF of the number of co-occurring conditions for the entire study population and NI subtypes by age in months. Peripheral and progressive subtypes are not included given the small sample sizes.

A small percentage of children with NI had ≥9 co-occurring chronic conditions, with an increasing prevalence as they aged: 5.3% by 2 years, 10.0% by 4 years, and 12.8% by 6 years (Fig 3, Supplemental Fig 6). Cardiac (78.0%), endocrine (45.8%), and skin (41.9%) problems emerged as prevalent in those children compared with children who had fewer co-occurring chronic conditions earlier in their lives (Fig 3). Children with anatomic and stroke and/or hemorrhage NI diagnoses accumulated co-occurring chronic conditions faster and in greater number overall than children with genetic and static NI diagnoses (Fig 4).

Discussion

In this cohort of children with NI enrolled in Medicaid, co-occurring chronic conditions were prevalent by age 6 years, with the extent of multimorbidity increasing through early childhood years. Digestive, respiratory, and mental health problems were particularly paramount. These chronic problems layered with time; digestive problems presented early in infancy, whereas respiratory and mental health problems were diagnosed in early toddler and school-aged years, respectively. One of every 8 children with NI experienced ≥9 chronic conditions co-occurring by age 6 years, with cardiac, endocrine, and skin problems most prevalent in those children. There was variability in both the extent and timing of multimorbidity across NI subtypes.

Multimorbidity has been recognized as “rather the rule than the exception”26 for aging adults, affecting 3 in 4 individuals aged 65 years and older.27 Although multimorbidity is much lower in the population-level studies of children,28,29 there has been growing focus on multimorbidity experienced by children with medical complexity.24,30,31 The extensive multimorbidity of young children with NI in the current study complements previous literature. For example, authors of cross-sectional studies in children of all ages with cerebral palsy enrolled in Medicaid report a high rate of multimorbidity (eg, median of 6 co-occurring chronic conditions).6 The current study revealed that multimorbidity emerges quickly in the early childhood years across a broad array of NI subtypes.

Clinical practice guidelines for care maintenance in children with specific NI diagnoses (eg, cerebral palsy, trisomy 21) prompt clinicians to recognize co-occurring chronic conditions.32–34 However, children with NI are most often purposefully excluded from research studies and the development of evidence-based and consensus-driven recommendations to guide care.35–37 Furthermore, such recommendations and guidelines do not offer direction on how to manage and treat multiple co-occurring chronic conditions that affect different organ systems.38,39

More attention to the diagnosis and management of specific coexisting conditions in children with NI is warranted. For example, our data reveal a high prevalence of respiratory co-occurring chronic conditions in children with NI; nearly 9 of 10 children with NI had a co-occurring respiratory chronic condition by age 6 years. The children’s prevalence of asthma, in particular, was nearly 7 times higher than the 8.3% that has been reported in the general pediatric population.40 Although the commonality of chronic respiratory problems in children with NI is well known, authors of previous studies of children with cerebral palsy and other NI diagnoses have not reported a high prevalence of asthma.41 Etiologies of bronchospasm in children with NI include aspiration of oropharyngeal sections, gastroesophageal reflux, and impaired clearance and/or bronchial plugging of respiratory mucous.42 Children with NI are not known to have a higher risk of bronchospasm from atopy or environmental exposures. Characteristic reactive airway disease in children with NI may be particularly challenging to accurately diagnose, especially because of the children’s limitations in performance with pulmonary function testing.43 It is possible that the diagnosis of asthma may have been applied liberally to some children with NI in the current study. Nonetheless, further investigation is needed on the diagnosis and treatment of chronic respiratory comorbidities in children with NI, including the effectiveness of inhaled corticosteroids and β-agonists in the setting of NI-related bronchospasm etiologies.

Additionally, the high prevalence of mental and behavioral health problems in children with NI is important to highlight. Authors of previous studies in children with cerebral palsy also report a higher prevalence of these problems, especially ADHD and anxiety44,45; although, the early emergence of these diagnoses in this study raises questions as to the possibility of misclassification or bias in diagnosis. Existing mental and behavioral health screening tools and methods have been largely validated in otherwise healthy children.46 Little is known about how those tools and methods perform in children with NI.47 Moreover, the efficacy of pharmacologic and behavioral interventions for mental and behavioral problems in children with NI has been understudied.48,49 In general, better integration of mental and physical health care for all patients has been a long-standing goal of the US pediatric health system.50 Young children with NI who have mental and behavioral health problems, in particular, deserve that care integration, with sufficient attention to opportunities for positive parenting and resiliency as well as for improvements in quality of care with mental health screening, specialty comanagement, and treatment.47

Emerging literature highlights care concerns for individuals with multimorbidity, including care that is disease centered rather than patient centered.26,27,51,52 Disease-centered care lacks sufficient attention to the interactions between co-occurring conditions and is often fragmented across numerous health care providers, resulting in limited care coordination and planning.53 Additionally, disease-centered care has been associated with higher, yet often ineffective, use of health care services and increased health care costs as well as suboptimal treatment of chronic disease, increased risk of adverse events, and decreased health-related quality of life in adults with multimorbidity.26,52,54,55 Although not measured in the current study, there is a critical need to assess whether these experiences and outcomes relate to infants and toddlers with NI as they rapidly acquire multiple co-occurring chronic conditions.

The current study has several limitations. Co-occurring chronic conditions were distinguished with diagnosis codes from administrative claims of health care encounters. It is likely that the conditions had an earlier onset, with symptoms emerging before the encounters, and thus we likely underestimate the true degree of multimorbidity experienced by these children at any given time. Given the limited number of diagnosis codes available to submit with a health care claim (eg, in some cases, 2 codes), undercoding, and therefore underdiagnosis, for some of the conditions may have occurred. Alternatively, there may have been misclassification for some co-occurring chronic conditions, especially those that are difficult to diagnose in children with NI (eg, asthma). Furthermore, our count variable of multimorbidity misses nuances of severity and longevity of the co-occurring chronic conditions. Some comorbid chronic conditions may be mild in symptomatology or improve over time, whereas others may greatly impact overall lifelong health and function for the child. Finally, the findings from this study may generalize best to children with NI continuously enrolled in Medicaid. Further investigation is needed to assess whether the attributes and severity of NI are similar for children who are not continuously enrolled in Medicaid and for those using private insurance. In future studies, researchers should also assess the evolvement of multimorbidity and the trajectories of co-occurring chronic conditions experienced by children with NI through adolescence and beyond.56

Despite these limitations, the findings describing the extent of multimorbidity and the types of co-occurring chronic conditions experienced by young children with NI in the current study may be helpful in informing approaches to care, both for individual patients and for the health care system at large. For example, findings on prevalence and timing of multimorbidity may inform approaches to anticipatory guidance for infants and toddlers with NI. Additionally, incorporating data regarding the likelihood of experiencing co-occurring chronic conditions into prognostic discussions may shape families’ awareness of and preparedness for future multimorbidity. Future work focused on identifying trajectories of chronic comorbidities would enable clinicians to anticipate the future health care problems and needs of children with NI and tailor care delivery. Existing multidisciplinary care models for children with NI could be redesigned to better encompass health care professionals, services, and therapies that match the children’s coexisting chronic condition patterns. Such efforts may better prepare the health system to anticipate and address concomitant increases in health services use (eg, emergency department visits and hospitalizations) associated with increasing multimorbidity in children.6,57–59

In addition, the prevalence and extent of disease beyond neurologic manifestations of NI highlights the importance of education on multimorbidity.60,61 Most, if not all, pediatric trainees will care for this growing pediatric population in the future, regardless of their area of practice.

Increased emphasis on the clinical and physiologic interactions of common co-occurring chronic conditions in children with NI (eg, impact of obesity on obstructive sleep apnea or impact of reflux on asthma), as well as the interprofessional skills to work across clinical disciplines and specialties to manage multimorbidity, is necessary.62

Conclusions

Diagnosis of multiple co-occurring chronic conditions was nearly universal by age 6 in this cohort of children with NI enrolled in Medicaid. Given the challenges inherent in the care of individuals with multimorbidity, this study highlights the need for research, education, and reevaluation of health infrastructure to meet the needs of this fragile population of children.

Glossary

- ADHD

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

- CCS

Clinical Classification System

- CI

confidence interval

- ICD-9

International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision

- IQR

interquartile range

- MCF

mean cumulative function

- NI

neurologic impairment

Footnotes

The funders or sponsors did not participate in the work.

Drs Thomson, Hall, and Berry conceptualized and designed the study, analyzed and interpreted the data, and drafted the initial manuscript; Drs Nelson, Flores, DeCourcey, Agrawal, Goodman, Feinstein, Coller, Cohen, Kuo, Antoon, and Houtrow and Ms Garrity and Ms Bastianelli participated in the concept and design of the study, analyzed and interpreted the data, and revised the manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (award K08HS025138; Dr Thomson), the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health (award K23HD091295; Dr Feinstein), the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (award K12HL137943; Dr Antoon), and the Health Resources and Services Administration of the US Department of Health and Human Services (UA6MC31101; Drs Berry and Hall; Children and Youth with Special Health Care Needs Research Network). This information or content and conclusions are those of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, or the Maternal and Child Health Bureau. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Venkateswaran S, Shevell MI. Comorbidities and clinical determinants of outcome in children with spastic quadriplegic cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2008;50(3):216–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berry JG, Graham RJ, Roberson DW, et al. . Patient characteristics associated with in-hospital mortality in children following tracheotomy. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95(9):703–710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Srivastava R, Berry JG, Hall M, et al. . Reflux related hospital admissions after fundoplication in children with neurological impairment: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2009;339:b4411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strauss D, Brooks J, Rosenbloom L, Shavelle R. Life expectancy in cerebral palsy: an update. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2008;50(7):487–493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strauss D, Shavelle R, Reynolds R, Rosenbloom L, Day S. Survival in cerebral palsy in the last 20 years: signs of improvement? Dev Med Child Neurol. 2007;49(2):86–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berry JG, Glader L, Stevenson RD, et al. . Associations of coexisting conditions with healthcare spending for children with cerebral palsy. J Pediatr. 2018;200:111–117.e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomson JE, Feinstein JA, Hall M, Gay JC, Butts B, Berry JG. Identification of children with high-intensity neurological impairment. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(10):989–991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berry JG, Glotzbecker M, Rodean J, Leahy I, Hall M, Ferrari L. Comorbidities and complications of spinal fusion for scoliosis. Pediatrics. 2017;139(3):e20162574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kinsman SL, Levey E, Ruffing V, Stone J, Warren L. Beyond multidisciplinary care: a new conceptual model for spina bifida services. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2000;10(suppl 1):35–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cremer N, Hurvitz EA, Peterson MD. Multimorbidity in middle-aged adults with cerebral palsy. Am J Med. 2017;130(6):744.e9-744.e15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayles E, Jones A, Harvey D, Plummer D, Ruston S. Delivering healthcare services to children with cerebral palsy and their families: a narrative review. Health Soc Care Community. 2015;23(3):242–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feudtner C, Levin JE, Srivastava R, et al. . How well can hospital readmission be predicted in a cohort of hospitalized children? A retrospective, multicenter study. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):286–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghose R. Complications of a medically complicated child. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(4):301–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pantilat SZ, Lindenauer PK, Katz PP, Wachter RM. Primary care physician attitudes regarding communication with hospitalists. Dis Mon. 2002;48(4):218–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roy CL, Poon EG, Karson AS, et al. . Patient safety concerns arising from test results that return after hospital discharge. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(2):121–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sacchetti A, Sacchetti C, Carraccio C, Gerardi M. The potential for errors in children with special health care needs. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7(11):1330–1333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berry JG, Hall DE, Kuo DZ, et al. . Hospital utilization and characteristics of patients experiencing recurrent readmissions within children’s hospitals. JAMA. 2011;305(7):682–690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Massin MM, Montesanti J, Gérard P, Lepage P. Children with chronic conditions in a paediatric emergency department. Acta Paediatr. 2006;95(2):208–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murphy NA, Hoff C, Jorgensen T, Norlin C, Young PC. Costs and complications of hospitalizations for children with cerebral palsy. Pediatr Rehabil. 2006;9(1):47–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Economic costs associated with mental retardation, cerebral palsy, hearing loss, and vision impairment–United States, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53(3):57–59 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berry JG, Poduri A, Bonkowsky JL, et al. . Trends in resource utilization by children with neurological impairment in the United States inpatient health care system: a repeat cross-sectional study. PLoS Med. 2012;9(1):e1001158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomson J, Hall M, Ambroggio L, et al. . Aspiration and non-aspiration pneumonia in hospitalized children with neurologic impairment. Pediatrics. 2016;137(2):e20151612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Chronic Condition Indicator (CCI) for ICD-9-CM. Available at: www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/chronic/chronic.jsp. Accessed September 26, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Berry JG, Ash AS, Cohen E, Hasan F, Feudtner C, Hall M. Contributions of children with multiple chronic conditions to pediatric hospitalizations in the United States: a retrospective cohort analysis. Hosp Pediatr. 2017;7(7):365–372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Friedman B, Jiang HJ, Elixhauser A, Segal A. Hospital inpatient costs for adults with multiple chronic conditions. Med Care Res Rev. 2006;63(3):327–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Oostrom SH, Picavet HSJ, van Gelder BM, et al. . Multimorbidity and comorbidity in the Dutch population - data from general practices. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tinetti ME, Fried TR, Boyd CM. Designing health care for the most common chronic condition–multimorbidity. JAMA. 2012;307(23):2493–2494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhong W, Finnie DM, Shah ND, et al. . Effect of multiple chronic diseases on health care expenditures in childhood. J Prim Care Community Health. 2015;6(1):2–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Russell J, Grant CC, Morton SMB. Multimorbidity in early childhood and socioeconomic disadvantage: findings from a large New Zealand child cohort. Acad Pediatr. 2020;20(5):619–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cohen E, Kuo DZ, Agrawal R, et al. . Children with medical complexity: an emerging population for clinical and research initiatives. Pediatrics. 2011;127(3):529–538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen E, Berry JG, Camacho X, Anderson G, Wodchis W, Guttmann A. Patterns and costs of health care use of children with medical complexity. Pediatrics. 2012;130(6). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/130/6/e1463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ivan DL, Cromwell P. Clinical practice guidelines for management of children with Down syndrome: part II. J Pediatr Health Care. 2014;28(3):280–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ivan DL, Cromwell P. Clinical practice guidelines for management of children with Down syndrome: part I. J Pediatr Health Care. 2014;28(1):105–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shaunak M, Kelly VB. Cerebral palsy in under 25 s: assessment and management (NICE guideline NG62). Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2018;103(4):189–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bradley JS, Byington CL, Shah SS, et al.; Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society; Infectious Diseases Society of America . The management of community-acquired pneumonia in infants and children older than 3 months of age: clinical practice guidelines by the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(7):e25–e76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lion KC, Wright DR, Spencer S, Zhou C, Del Beccaro M, Mangione-Smith R. Standardized clinical pathways for hospitalized children and outcomes. Pediatrics. 2016;137(4):e20151202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ralston SL, Lieberthal AS, Meissner HC, et al. ; American Academy of Pediatrics. Clinical practice guideline: the diagnosis, management, and prevention of bronchiolitis. [published correction appears in Pediatrics. 2015;136(4):782] Pediatrics. 2014;134(5). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/134/5/e1474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liptak GS, Murphy NA; Council on Children With Disabilities. Providing a primary care medical home for children and youth with cerebral palsy. Pediatrics. 2011;128(5). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/128/5/e1321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.National Guideline Alliance Cerebral Palsy in Under 25s: Assessment and Management. London, United Kingdom: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK); 2017 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Akinbami LJ, Simon AE, Rossen LM. Changing trends in asthma prevalence among children. Pediatrics. 2016;137(1):1–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boel L, Pernet K, Toussaint M, et al. . Respiratory morbidity in children with cerebral palsy: an overview. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2019;61(6):646–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barish CF, Wu WC, Castell DO. Respiratory complications of gastroesophageal reflux. Arch Intern Med. 1985;145(10):1882–1888 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kwon YH, Lee HY. Differences of respiratory function in children with spastic diplegic and hemiplegic cerebral palsy, compared with normally developed children. J Pediatr Rehabil Med. 2013;6(2):113–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Whitney DG, Peterson MD, Warschausky SA. Mental health disorders, participation, and bullying in children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2019;61(8):937–942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith KJ, Peterson MD, O’Connell NE, et al. . Risk of depression and anxiety in adults with cerebral palsy. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(3):294–300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Craig F, Savino R, Trabacca A. A systematic review of comorbidity between cerebral palsy, autism spectrum disorders and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2019;23(1):31–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mattson G, Kuo DZ; Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health; Council on Children With Disabilities . Psychosocial factors in children and youth with special health care needs and their families. Pediatrics. 2019;143(1):e20183171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Blackmer AB, Feinstein JA. Management of sleep disorders in children with neurodevelopmental disorders: a review. Pharmacotherapy. 2016;36(1):84–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sabus A, Feinstein J, Romani P, Goldson E, Blackmer A. Management of self-injurious behaviors in children with neurodevelopmental disorders: a pharmacotherapy overview. Pharmacotherapy. 2019;39(6):645–664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ader J, Stille CJ, Keller D, Miller BF, Barr MS, Perrin JM. The medical home and integrated behavioral health: advancing the policy agenda. Pediatrics. 2015;135(5):909–917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fortin M, Soubhi H, Hudon C, Bayliss EA, van den Akker M. Multimorbidity’s many challenges. BMJ. 2007;334(7602):1016–1017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pefoyo AJ, Bronskill SE, Gruneir A, et al. . The increasing burden and complexity of multimorbidity. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schiøtz ML, Høst D, Frølich A. Involving patients with multimorbidity in service planning: perspectives on continuity and care coordination. J Comorb. 2016;6(2):95–102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bodenheimer T. Disease management–promises and pitfalls. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(15):1202–1205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Prados-Torres A, Poblador-Plou B, Gimeno-Miguel A, et al. . Cohort profile: the epidemiology of chronic diseases and multimorbidity. The EpiChron cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47(2):382–384f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gross PH, Bailes AF, Horn SD, Hurvitz EA, Kean J, Shusterman M; Cerebral Palsy Research Network . Setting a patient-centered research agenda for cerebral palsy: a participatory action research initiative. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2018;60(12):1278–1284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Berry JG, Gay JC, Joynt Maddox K, et al. . Age trends in 30 day hospital readmissions: US national retrospective analysis. BMJ. 2018;360:k497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Berry JG, Toomey SL, Zaslavsky AM, et al. . Pediatric readmission prevalence and variability across hospitals. JAMA. 2013;309(4):372–380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Berry JG, Rodean J, Hall M, et al. . Impact of chronic conditions on emergency department visits of children using Medicaid. J Pediatr. 2017;182:267–274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tahir A, Al-Zubaidy M, Naqvi D, et al. . Medical school teaching on interprofessional relationships between primary and social care to enhance communication and integration of care - a pilot study. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2019;10:311–332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.The American Board of Pediatrics. Pediatrics-neurodevelopmental disabilities pathway. 2013. Available at: https://www.abp.org/content/pediatrics-neurodevelopmental-disabilities-pathway. Accessed June 29, 2019

- 62.Naccarella L, Osborne RH, Brooks PM. Training a system-literate care coordination workforce. Aust Health Rev. 2016;40(2):210–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]