Abstract

Introduction:

Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome and hereditary paraganglioma-pheochromocytoma syndrome are rare genetic cancer syndromes that predispose patients to renal neoplasia. We report a case of a 25-year-old man with both Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome and hereditary paraganglioma-pheochromocytoma syndrome who presented with painless gross hematuria and was found to have metastatic clear cell renal carcinoma.

Case Presentation:

A previously healthy, 25-year-old man presented to his outpatient primary care physician with painless gross hematuria. Urinalysis results demonstrated hemoglobinuria, and serum chemistry results demonstrated a creatinine level of 1.61 mg/dL (baseline of 0.96 mg/dL). A computed tomography scan showed that the patient had a left renal mass, renal vein thrombosis with inferior vena cava extension, and nodal and hepatic metastasis. Biopsy specimens of the left renal mass and liver demonstrated clear cell carcinoma. The patient underwent cytoreductive nephrectomy, caval thrombectomy, and partial colectomy with reanastomosis. He received palliative therapy with 1 mg/kg of ipilimumab and 3 mg/kg of nivolumab for 4 cycles.

Conclusion:

To our knowledge, this is the first known case report to date documenting a patient with concurrent Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome and hereditary paraganglioma-pheochromocytoma syndrome. This case demonstrates the exceptionally young presentation of metastatic renal cell carcinoma with this genotype.

Keywords: Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome, clear cell renal carcinoma, FLCN gene, paraganglioma-pheochromocytoma syndrome, renal cell carcinoma, SDHB gene

INTRODUCTION

Birt-Hogg-Dubé (BHD) syndrome is an autosomal dominant genetic disease caused by mutations in the folliculin (FLCN) gene located at 17p11.2, which is characterized by benign skin lesions of fibrofolliculomas, trichodiscomas, and acrochordons presenting in the third decade of life.1,2 The most common manifestation of the disease is lung cysts, followed by spontaneous pneumothorax and renal cell carcinoma (RCC).3

The most serious complication of BHD syndrome is the increased risk of RCC. One study found that patients with BHD syndrome have a 7-fold increased risk of developing RCC.4 Renal carcinomas in patients with this syndrome have a variety of different histologic findings, but the most commonly seen renal carcinomas are chromophobe and oncocytic tumors.5 In a study of histologic findings for 33 patients with RCC and BHD syndrome, 70% had oncocytoma or chromophobe-oncocytoma; 3 patients (9%) had clear cell carcinoma.6

Hereditary paraganglioma-pheochromocytoma syndrome (HPPS) is a genetic disease caused by a mutation in the succinate dehydrogenase gene and characterized by an increased risk of paragangliomas, pheochromocytomas, and clear cell renal carcinoma.7 The diagnosis of HPPS is established by a germline pathologic variant in succinate dehydrogenase gene SDHB, SDHA, SDHAF2, SDHC, or SDHD or in MYC-associated factor MAX or transmembrane protein TMEM127.7 Mutations in the succinate dehydrogenase gene halt the citric acid cycle, which triggers hypoxia pathways in cells leading to tumorigenesis.8 This is the reasoning behind the observation that HPPS genetic mutations show greater phenotypic expression and decreased mutation frequency in the population at higher altitudes.8 Another genetic feature of HPPS is that the mutation is inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion that demonstrates parent-of-origin effects, whereby inheriting the pathologic gene mutation from the father leads to a greater risk of manifesting the syndrome.9 Manifestations include pheochromocytomas, which present with symptoms of excess catecholamines (e.g., high blood pressure, diaphoresis, and headache) or with mass effects.7 Another presentation of HPPS is symptoms of paragangliomas, which arise from neuroendocrine tissues, commonly the adrenal medulla.7 Symptomatic paragangliomas also present with symptoms of excess catecholamines, although most paragangliomas are nonsecretory.7 Paragangliomas can also manifest as mass effects, which can present in patients with symptoms of nerve compression or with an enlarging mass.7

A subset of patients with HPPS, specifically those with SDHB and SDHD mutations, are at increased risk of RCC.9 Patients with pathologic mutations in SDHB have a lifetime risk of RCC of 4.7% compared with 1.7% in the general population.10

CASE PRESENTATION

Presenting Concerns

A 25-year-old man with a history of asthma presented to his primary care physician with painless gross hematuria. He denied having flank pain, fever, chills, or weight loss. He did not use anticoagulant medications or supplements and reported no history of kidney disease. Urinalysis results showed hemoglobinuria. His serum creatinine level was 1.61 mg/dL, with a baseline creatinine level of 0.96 mg/dL 6 months earlier. A computed tomography (CT) scan showed that the patient had a left renal mass, renal vein thrombosis with inferior vena cava extension, and nodal and hepatic metastasis, as shown in Figure 1. Interestingly, this patient did not have lung cysts, which are seen in approximately 85% of patients with BHD syndrome.11

Figure 1.

Computed tomography findings for a 25-year-old man. The red arrow indicates a large heterogeneous mass arising from the left kidney replacing the left renal parenchyma. The green arrow indicates an exophytic lesion arising from the lower pole of the left kidney, which measures 8 cm. The gold arrow indicates extensive thrombus within the left renal vein, which extends up to the intrahepatic inferior vena cava. The yellow arrow indicates a rounded hepatic mass compatible with metastasis measuring up to 3 cm.

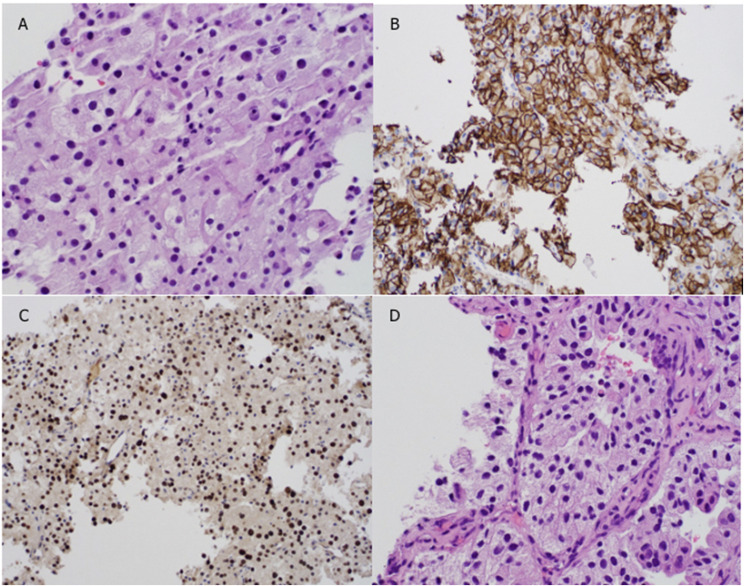

The patient was admitted to the hospital for further workup and placement of an inferior vena cava filter. Biopsy specimens of the left renal mass and liver demonstrated clear cell carcinoma, as shown in Figure 2. Transcription factor TFE3 translocation testing yielded normal results. Pathology staining of the renal biopsy specimen was positive for carbonic anhydrase 9 (CAIX), paired box gene 8 (PAX8), and cytokine. Pathology staining of the liver biopsy specimen was positive for PAX8. Further imaging consisted of CT scans of the chest, a bone scan, and brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), all of which showed no evidence of further metastatic disease.

Figure 2.

Pathology staining of biopsy specimens. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin stain, renal biopsy. (B) CAIX stain, renal biopsy. (C) KPAX8 stain, renal biopsy. (D) Hematoxylin and eosin stain, liver biopsy. Magnification = ×10 in A and D; ×4 in B and C.

Therapeutic Intervention and Treatment

The patient underwent cytoreductive nephrectomy, caval thrombectomy, and partial colectomy with reanastomosis, and he tolerated surgery without complications. He received 4 units of packed red blood cells intraoperatively. His hemoglobin level remained stable throughout his hospital course. He had episodes of hypotension in the first 2 days postoperatively, thought to be related to the epidural anesthesia.

Two days after discharge from the hospital, the patient presented to the emergency department because of nightly fevers to 40.0°C (104°F at home), a 7 of 10 rating of abdominal pain, and ongoing watery diarrhea since the surgery. A chest radiograph showed free air under the diaphragm. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated free fluid with flecks of gas and linear peritoneal enhancement, which was concerning for an infected abscess. A percutaneous Jackson-Pratt drain was placed by an interventional radiologist, and culture-driven intravenous antibiotics were administered. Cultures yielded heavy growth of Escherichia coli and moderate growth of Enterococcus faecalis. Gram staining demonstrated many gram-negative rods and gram-positive cocci. A blood culture was positive for Bacteroides fragilis with gram-negative rods.

Follow-Up and Outcomes

The patient’s postsurgical course was complicated by multiple emergency department visits because of fever, abdominal pain, and left flank pain, which were caused by recurrence of his intraabdominal abscess. He had intermittent clogging of the Jackson-Pratt drain. On imaging, the retroperitoneal abscess demonstrated fistulous connection to the large bowel. Pain management was also an issue with his postoperative course.

After the biopsy proved metastatic renal carcinoma, the patient met with a genetic counselor and underwent genetic testing for cancer syndromes. Testing was conducted with a next-generation sequencing panel that simultaneously analyzed 19 genes associated with increased risk of renal cancer (Ambry Renal-Next; Ambry Genetics, Aliso Viejo, CA). Pathogenic mutations were found in FLCN and SDHB, specifically at c.1252delC and p.L87S, respectively. No other known pathogenic mutations or variants of uncertain significance were identified in any of the other genes analyzed. This patient did not have other phenotypic characteristics of BHD syndrome (skin lesions, pneumothorax) or HPPS (paragangliomas or pheochromocytomas). His family history was notable for a maternal uncle and maternal grandmother with colon cancer at age 48 and 47 years, respectively, and for a maternal cousin with a history of recurrent pneumothorax. It is possible that the SDHB mutation is de novo or paternal in origin, because the father has a granddaughter with congenital ganglioneuroblastoma.

The patient received palliative therapy with 1 mg/kg of ipilimumab and 3 mg/kg of nivolumab for 4 cycles. This patient reported mild gastrointestinal upset after ipilimumab and nivolumab; however, he experienced no serious adverse effects from this treatment. At the end of 4 cycles, imaging showed progressive disease, so treatment was discontinued. The patient then received everolimus for 3 weeks, but everolimus treatment was held when he was admitted to the hospital for fever and ascites. He then developed multiorgan failure requiring a ventilator and blood pressure support. The patient later developed septic shock caused by ventilator-associated pneumonia. He became encephalopathic and had progressive multiorgan failure. His code status was then changed to do not resuscitate, and he was transitioned to comfort care, during which time the patient passed away with his family at the bedside. A summary of this case is shown in Table 1. The patient gave written informed consent for this case report.

Table 1.

Case timeline

| Relevant Medical History and Interventions | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| A 25-year-old man presented with a history of asthma. He had a family history of a maternal uncle and maternal grandmother with colon cancer at age 48 and 47 years, respectively, as well as a maternal cousin with a history of recurrent pneumothorax and a cousin with congenital ganglioneuroblastoma. | |||

| Date | Summaries from initial and follow-up visits | Diagnostic testing | Interventions |

| March 2019 | The patient had painless gross hematuria. Biopsy demonstrated renal clear cell carcinoma | Urinalysis; CT scan showing left renal mass, renal vein thrombosis with IVC extension, and nodal and hepatic metastases. Results of CT scans of the chest, a bone scan, and brain MRI showed no further metastatic disease | Admitted to the hospital for placement of an IVC filter and for renal biopsy; surgery consisted of cytoreductive nephrectomy, caval thrombectomy, and partial colectomy with reanastomosis |

| April 2019 | After discharge, the patient presented to the ED with nightly fevers, abdominal pain, and watery diarrhea | Chest radiograph showed free air under the diaphragm. CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated free fluid with flecks of gas and linear peritoneal enhancement, which was concerning for an infected abscess | Drain placement; administration of IV antibiotics |

| July 2019 | The patient presented to the ED for fever, abdominal pain, and left flank pain | Sinogram with fistula; germline pathogenic mutations found in FLCN and SDHB, specifically at c.1252delC and p.L87S | Drain exchange; administration of antibiotics |

| March to August 2019 | Ongoing metastatic disease | Palliative therapy with 1 mg/kg of ipilimumab and 3 mg/kg of nivolumab for 4 cycles | |

| September to October 2019 | Progressive disease on imaging | CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis showed decreasing size of left upper quadrant abscess, increasing ascites, and advanced metastatic disease to the liver | 5 mg/d of everolimus |

| October to December 2019 | The patient was admitted to the hospital for fever and ascites. He developed multiorgan failure, and then septic shock because of ventilator-acquired pneumonia | CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis showed persistent left upper quadrant abscess, advanced metastatic disease, and ascites | Antibiotic therapy with cefepime, levofloxacin, and daptomycin |

| January 2020 | The patient’s code status was changed to DNR, and he was then transitioned to comfort care, during which time the patient passed away with his family at the bedside | Fentanyl patches and morphine for pain | |

CT = computed tomography; DNR = do not resuscitate; ED = emergency department; FLCN = folliculin; IV = intravenous; IVC = inferior vena cava; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; SDHB = succinate dehydrogenase B.

DISCUSSION

This is the first case report, to our knowledge, documenting a patient presenting with concurrent BHD syndrome and HPPS. The youngest reported symptomatic presentation with renal cancer in BHD syndrome is in a 14-year-old girl who presented with a bulky abdominal mass.12 One other patient previously was documented to present with RCC at age 20 years.13 The average age at presentation of BHD syndrome with RCC is 50.4 years.14 Of note, the patient described in the current case presented with metastatic RCC at age 25 years, markedly younger than average for BHD syndrome. This case is unusual because he is the youngest patient reported with BHD syndrome presenting with metastatic RCC. Both young patients documented in the literature had no evidence of local invasion or metastases.12,13 Previous literature has shown that patients with a mutation in exon 11 in the form of a C-deletion had fewer renal tumors than those who had a C-insertion mutation.11 Interestingly, this patient had a C-deletion mutation in exon 11, specifically c.1252delC. A prior report from researchers at the National Institutes of Health stated that they had few cases that progressed to metastatic disease, and 2 of those patients had clear cell carcinoma histology, which has notoriously behaved more aggressively than other histologies in BHD syndrome such as chromophobe and oncocytic tumors.15

The differential diagnosis of this patient’s tumor histology was papillary RCC with cytoplasmic clearing, chromophobe RCC, oncocytoma, epithelioid angiomyolipoma, or clear cell carcinoma. A microphthalmia-associated transcription factor translocation RCC was also considered, because this type commonly presents in young persons.16 A microphthalmia-associated transcription factor translocation was ruled out by negative staining for transcription factor TFE16. This tumor’s positive staining for CAIX suggested that it was less likely to be chromophobe RCC, epithelioid angiomyolipoma, or papillary RCC, all of which stain negative for CAIX.16,17 This patient’s histologic diagnosis of clear cell carcinoma was evident on hematoxylin and eosin staining, as shown in Figure 2. Also, this patient’s metastatic tumors were PAX8 and CAIX positive, suggesting metastatic clear cell carcinoma. This patient’s pathologic diagnosis was confirmed by a genitourinary pathologist.

Given that this patient’s mutation traditionally is less likely to present with renal tumors, another process could have contributed to this patient’s young presentation of aggressive metastatic clear cell renal carcinoma. One possible reason for the patient’s young presentation of metastatic disease is the concurrent pathologic mutations in both FLCN and SDHB, both of which predispose to clear cell renal carcinoma. The gene responsible for BHD syndrome may be related to oncogenesis of clear cell carcinoma via loss of heterozygosity at chromosome 3p.5 Another possible mechanism is via the von Hippel-Lindau disease gene, which was found to be mutated in 33% to 57% of patients with BHD syndrome, consistent with the rate found in sporadic clear cell carcinoma.5 However, clear cell carcinoma is a rare histology in BHD syndrome, only accounting for 9% of RCCs in a prior study.6 Because of this, it is likely that this patient’s RCC is primarily caused by HPPS, with a possible contribution by the FLCN gene of BHD syndrome. Notably, RCC in a patient with BHD syndrome at this young age should prompt practitioners to consider genetic screening for other cancer syndromes.

Although there are no strict guidelines, patients with BHD syndrome are suggested to undergo renal ultrasonography and abdominal MRI at the time of diagnosis, with yearly follow-up screening with renal ultrasonography.18 A more sensitive option is a yearly MRI scan.19 Additionally, patients with HPPS should have biennial body MRI scans starting at age 6 to 8 years.7 This patient’s family members were advised to undergo genetic testing to determine whether they should be followed up with screening imaging.

CONCLUSION

This case demonstrates a rare presentation of concurrent BHD syndrome and HPPS presenting as metastatic RCC. This case report is intended to provide education to practitioners about 2 rare genetic cancer syndromes and the indications for genetic screening and imaging for these patients and their family members.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Kaiser Permanente South Sacramento Department of Pathology for sharing the pathology images.

Kathleen Louden, ELS, of Louden Health Communications performed a primary copyedit.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement: The author(s) have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Authors’ Contributions: Julia Boland participated in acquisition and analysis of the data and drafting and submission of the final manuscript. Darius Shahbazi, Ryan Stevenson, MD, and Shahin Shahbazi, MD, participated in analysis of the data and drafting of the final manuscript. All authors have given final approval to the manuscript.

References

- 1.Birt AR, Hogg GR, Dubé WJ. Hereditary multiple fibrofolliculomas with trichodiscomas and acrochordons. Arch Dermatol 1977 Dec;113(12):1674-7. DOI: 10.1001/archderm.113.12.1674, PMID:596896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khoo SK, Bradley M, Wong FK, Hedblad MA, Nordenskjöld M, Teh BT. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome: Mapping of a novel hereditary neoplasia gene to chromosome 17p12-q11.2. Oncogene 2001 Aug 23;20(37):5239-42. DOI: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204703, PMID:11526515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmidt LS, Warren MB, Nickerson ML, et al. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome, a genodermatosis associated with spontaneous pneumothorax and kidney neoplasia, maps to chromosome 17p11.2. Am J Hum Genet 2001 Oct;69(4):876-82. DOI: 10.1086/323744, PMID:11533913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zbar B, Alvord WG, Glenn G, et al. Risk of renal and colonic neoplasms and spontaneous pneumothorax in the Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2002 Apr;11(4):393-400. PMID:11927500 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pavlovich CP, Walther MM, Eyler RA, et al. Renal tumors in the Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Am J Surg Pathol 2002 Dec;26(12):1542-52. DOI: 10.1097/00000478-200212000-00002, PMID:12459621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benusiglio PR, Giraud S, Deveaux S, et al. ; French National Cancer Institute Inherited Predisposition to Kidney Cancer Network . Renal cell tumour characteristics in patients with the Birt-Hogg-Dubé cancer susceptibility syndrome: A retrospective, multicentre study. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2014 Oct 29;9:163. DOI: 10.1186/s13023-014-0163-z, PMID:25519458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Else T, Greenberg S, Fishbein L. Hereditary paraganglioma-pheochromocytoma syndromes. In: GeneReviews [Internet]. Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al., editors. Seattle, WA: University of Washington; 2008. Updated October 4, 2018. Accessed February 13, 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1548/ [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baysal BE. Clinical and molecular progress in hereditary paraganglioma. J Med Genet 2008 Nov;45(11):689-94. DOI: 10.1136/jmg.2008.058560, PMID:18978332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ricketts CJ, Forman JR, Rattenberry E, et al. Tumor risks and genotype-phenotype-proteotype analysis in 358 patients with germline mutations in SDHB and SDHD. Hum Mutat 2010 Jan;31(1):41-51. DOI: 10.1002/humu.21136, PMID:19802898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andrews KA, Ascher DB, Pires DEV, et al. Tumour risks and genotype-phenotype correlations associated with germline variants in succinate dehydrogenase subunit genes SDHB, SDHC and SDHD. J Med Genet 2018 Jun;55(6):384-94. DOI: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2017-105127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmidt LS, Nickerson ML, Warren MB, et al. Germline BHD-mutation spectrum and phenotype analysis of a large cohort of families with Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 2005 Jun;76(6):1023-33. DOI: 10.1086/430842, PMID:15852235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schneider M, Dinkelborg K, Xiao X, et al. Early onset renal cell carcinoma in an adolescent girl with germline FLCN exon 5 deletion. Fam Cancer 2018 Jan;17(1):135-9. DOI: 10.1007/s10689-017-0008-8, PMID:28623476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benusiglio PR, Gad S, Massard C, et al. Case report: Expanding the tumour spectrum associated with the Birt-Hogg-Dube cancer susceptibility syndrome. F1000Res 2014 Jul 11;3:159. DOI: 10.12688/f1000research.4205.1, PMID:25254107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pavlovich CP, Grubb RL 3rd, Hurley K, et al. Evaluation and management of renal tumors in the Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. J Urol 2005 May;173(5):1482-6. DOI: 10.1097/01.ju.0000154629.45832.30, PMID:15821464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stamatakis L, Metwalli AR, Middelton LA, Marston Linehan W. Diagnosis and management of BHD-associated kidney cancer. Fam Cancer 2013 Sep;12(3):397-402. DOI: 10.1007/s10689-013-9657-4, PMID:23703644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu L, Qian J, Singh H, Meiers I, Zhou X, Bostwick DG. Immunohistochemical analysis of chromophobe renal cell carcinoma, renal oncocytoma, and clear cell carcinoma: An optimal and practical panel for differential diagnosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2007 Aug;131(8):1290-7. DOI: 10.1043/1543-2165(2007)131[1290:IAOCRC]2.0.CO;2, PMID:17683191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reuter VE, Argani P, Zhou M, Delahunt B; Members of the ISUP Immunohistochemistry in Diagnostic Urologic Pathology Group . Best practices recommendations in the application of immunohistochemistry in the kidney tumors: Report from the International Society of Urologic Pathology consensus conference. Am J Surg Pathol 2014 Aug;38(8):e35-49. DOI: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000258, PMID:25025368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johannesma PC, van de Beek I, van der Wel TJWT, et al. Renal imaging in 199 Dutch patients with Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome: Screening compliance and outcome. PLoS One 2019;14(3):e0212952. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0212952, PMID:30845233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Menko FH, van Steensel MA, Giraud S, et al. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome: Diagnosis and management. Lancet Oncol 2009 Dec;10(12):1199-206. DOI: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70188-3, PMID:19959076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]