Short abstract

Watch a video presentation of this article

Watch an interview with the author

Answer questions and earn CME

Abbreviations

- CCA

cholangiocarcinoma

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- Hh

Hedgehog

- IGF

insulin‐like growth factor

- IL‐6

interleukin‐6

- JCAD

junctional protein associated with coronary artery disease

- JNK

c‐Jun N‐terminal kinase

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- NAFLD

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- NASH

nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

- NF‐κB

nuclear factor‐κB

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- TREM1

triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 1

The Epidemic of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis and Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the only cancers with increasing incidence and mortality. 1 Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is rapidly becoming the most common cause of HCC in the United States because the prevalence of NASH is increasing. An estimated 21% of the US adult population is currently afflicted with NASH, and the prevalence rate is projected to increase to 33.5% by 2030, a staggering figure. 2 This is worrisome because HCC can be diagnosed in patients with NASH without cirrhosis. For example, in two large studies in the Veterans Health Administration, 20% to 36% of patients with NASH diagnosed with HCC did not have evidence of cirrhosis. 3 , 4 Also, mortality from NASH‐HCC appears to be higher than HCC caused by other chronic liver diseases. 5 , 6 The unique pathogenesis and natural history of NASH‐HCC make it more challenging to identify individuals who warrant intensified HCC surveillance.

The metabolic syndrome is key to the link between NASH and HCC. It has been known for some time that diabetes and obesity are risk factors for NASH‐HCC. 7 , 8 , 9 A recent analysis of patients from the Veterans Healthcare Administration found that other metabolic syndrome traits (i.e., hypertension and dyslipidemia) also confer HCC risk. Further, individual trait‐attributable HCC risks appeared to be additive because HCC prevalence increases in parallel with the number of metabolic syndrome traits. 10 This suggests that the pathogenesis of NASH‐HCC may be uniquely influenced by metabolic syndrome–induced derangements, including abnormal lipid metabolism, which causes oxidative stress. Treatments that address metabolic syndrome have been studied as HCC chemoprevention. Metformin (in patients with diabetes) and statins both have been associated with a reduction in HCC risk in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). 11

In this review, we describe currently understood mechanisms of carcinogenesis in NAFLD with emphasis on HCC, and mention emerging biomarkers and therapies. Although this review does not address cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) because of space limitations, a recent systematic review and meta‐analysis linked NAFLD to increased risk for CCA. This association was stronger for intrahepatic than extrahepatic CCA, suggesting common mechanisms with HCC. 12 We also briefly discuss extrahepatic malignancy.

Mechanisms of NASH‐HCC

Abnormal Lipid Accumulation: The Beginning of the Cascade

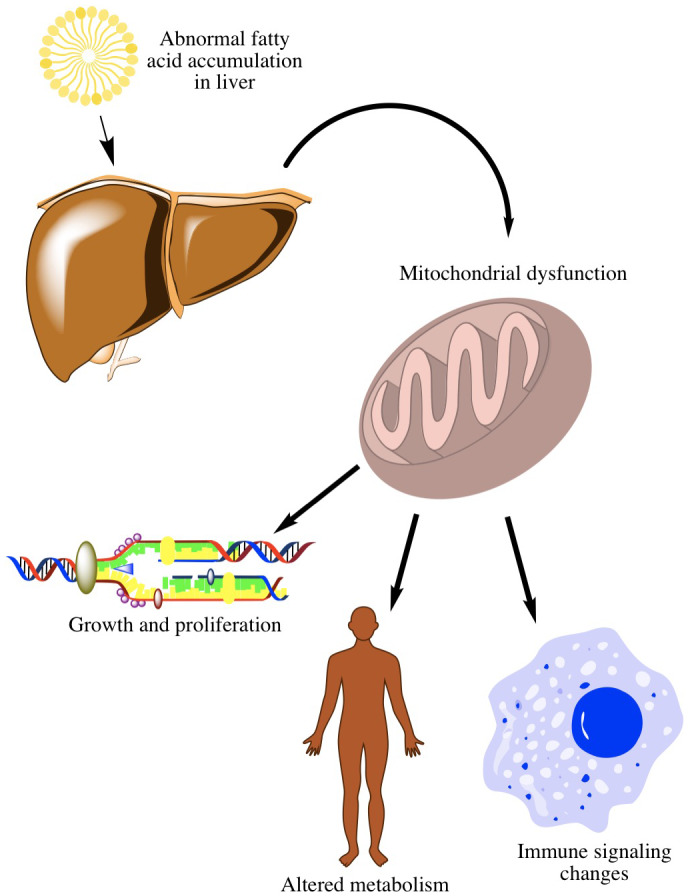

Metabolic syndrome is associated with accumulation of lipids in the liver, a key inciting event. Excessive lipid accumulation causes oxidative stress, resulting in mitochondrial dysfunction. This, in turn, sets off several procarcinogenic processes: (1) changes in lipid metabolism, (2) changes in growth and development pathways, and (3) changes in the immune system (Fig. 1).

FIG 1.

Metabolic syndrome–initiated mechanisms key to NASH‐HCC. Excessive lipid accumulation (a key inciting event) causes oxidative stress, resulting in mitochondrial dysfunction. This leads to changes in lipid metabolism, changes in growth and development pathways, and changes in the immune system that promote HCC.

Changes in Lipid Metabolism

In response to oxidative stress, hepatocytes make changes to fatty acid oxidation. For example, carnitine palmitoyltransferase 2 (CPT2) is downregulated, which helps hepatocytes escape from lipotoxicity but promotes malignant transformation, possibly through the accumulation of acylcarnitine. 13 Oxidative stress also leads to changes in sterol regulatory element‐binding proteins transcription factors, which regulate sterol and fatty acid biosynthesis and also interact with p53, a key tumor suppressor. 14 In fact, serum fatty acid profiles can be used as a signature for NASH‐HCC. 15

Changes in Growth and Proliferation Pathways

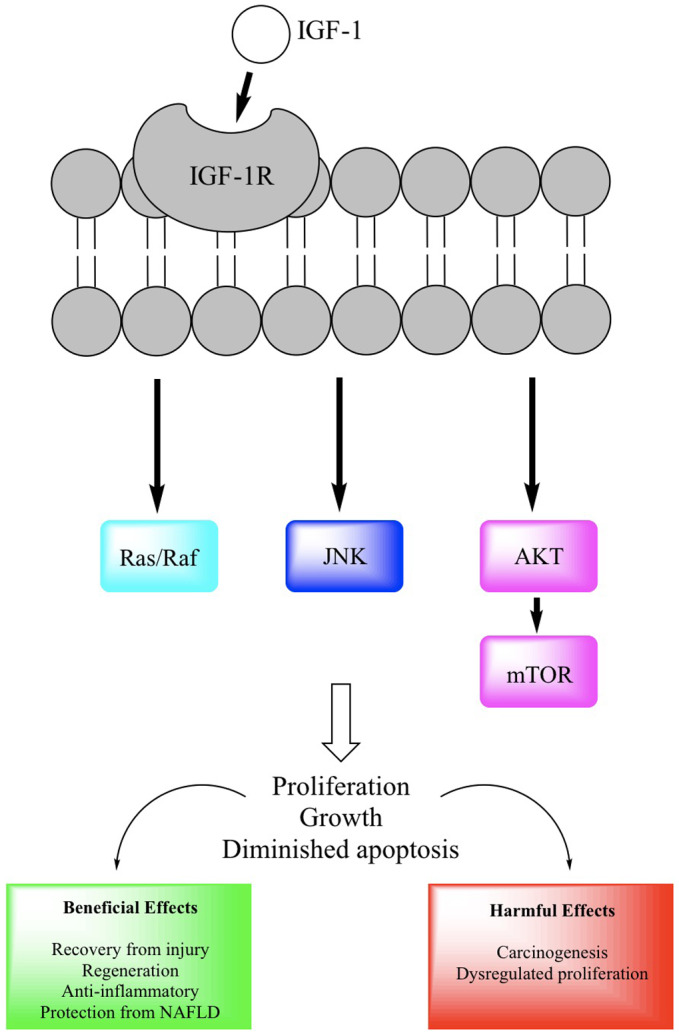

Metabolic syndrome has direct effects on growth and proliferation pathways that promote carcinogenesis. Fatty acid accumulation induces obesity‐associated proteins, such as junctional protein associated with coronary artery disease (JCAD), which is highly expressed in NASH‐HCC. 16 JCAD promotes activation of Yes‐associated protein 1 (YAP1), which is essential for tumor growth. The Hedgehog (Hh) signaling pathway is also consistently activated in animal models and patients with NASH. 17 Several pharmacological inhibitors of the Hh pathway, such as Vismodegib and Sonidegib, are potential therapeutics for NASH‐HCC, but it is important to balance the benefits and the risks because Hh signaling is necessary for liver regeneration. 18 Alterations in insulin‐like growth factor (IGF) signaling are frequently observed in HCC, with direct links to metabolic syndrome 19 , 20 (Fig. 2). Oxidative stress from excess lipids also induces caspase‐2, leading to hepatocyte apoptosis and likely resulting in compensatory hepatocyte proliferation. 21 , 22 Inhibitors of apoptosis, including branched chain amino acids, have been suggested as chemoprevention for NASH‐HCC. 22 , 23

FIG 2.

The importance of IGF signaling in NASH‐HCC. Insulin resistance and resultant hyperinsulinemia drive activation of growth pathways, including IGF‐1/AKT and mTOR. 41 IGF‐1 exerts anti‐inflammatory, antilipogenic, and antiapoptotic effects in animal models of NASH, but, paradoxically, IGF‐1R is often upregulated in HCC tissue, suggesting that the antiapoptotic effect may be driving carcinogenesis and promoting dysregulated growth. 20

Changes in the Immune System

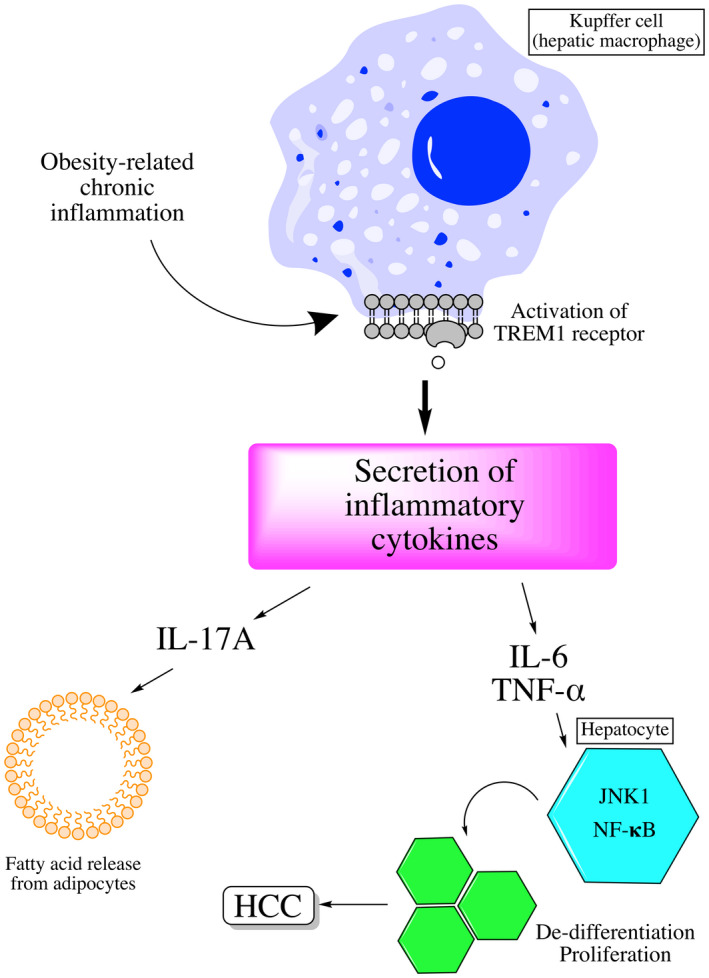

Oxidative stress also results in changes in immune signaling that can promote carcinogenesis. There is a selective loss of CD4+ T cells, which are important for antitumor surveillance and are uniquely susceptible to oxidative stress due to increased mitochondrial mass. 24 Kupffer cells, the resident hepatic macrophages, are activated by obesity‐related chronic inflammation and play an important role in HCC development through secretion of inflammatory cytokines (Fig. 3). 25 , 26 Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors, such as infliximab, have been considered for chemoprevention of HCC, but their pleiotropic effects complicate these efforts.

FIG 3.

Kupffer cells are activated via TREM‐1, whose activation leads to secretion of inflammatory cytokines, including TNF‐α and IL‐6. These induce alterations in NF‐κB signaling, thereby promoting dedifferentiation and proliferation of hepatocytes.

Other Mechanisms

Several genetic variants have been implicated in the development of NASH‐HCC. Polymorphisms in patatin‐like phospholipase domain‐containing protein 3 (PNPLA3) appear to increase the risk for HCC. 27 Telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) promoter mutations may also promote malignant transformation on a background of NASH. 28 Apolipoprotein B, previously associated with steatosis and HCC in familial hypobetalipoproteinemia, was found to be frequently mutated in HCC. 29 Dysbiosis has also been linked to NASH‐HCC via bile acid signaling to hepatocytes, leading to upregulation of growth pathways, including mammalian target of rapamycin (MTOR). 30 , 31 At least one randomized trial has studied probiotics given their beneficial effect on NAFLD histology in animal models. 32

Association and Mechanisms Linking NASH and Extrahepatic Cancer

NAFLD has also been linked to extrahepatic malignancies, most notably in the gastrointestinal tract, through metabolic syndrome–related mechanisms. 33 Obesity‐related chronic inflammation, alterations in adiponectin and leptin levels, and dysbiosis are all thought to link NAFLD to extrahepatic malignancy. 34 Notably, NAFLD was associated with increased all‐cause and cancer‐specific mortality in cancer survivors in one single‐center study. 35 The strongest link between NAFLD and extrahepatic malignancy is with colorectal adenomas and cancer. NAFLD has been independently associated with risk for colorectal neoplasia, and NASH appears to confer greater risk compared with simple steatosis. 36 , 37 , 38 Obesity and insulin resistance are thought to be key mechanisms. NAFLD is also associated with risk for breast cancer. Although obesity is thought to be the common risk factor, this association was present in nonobese women in only one study. The authors posited that in obese women, the presence of NAFLD modified risk minimally given the strong link between obesity and breast cancer. 39 A large study has also linked NAFLD to prostate cancer risk. 40

Conclusions

NAFLD is associated with the development of HCC through oxidative stress, which influences several key pathways in hepatocytes. Derangements, including insulin resistance and chronic inflammation, associated with metabolic syndrome have implications for the development and natural history of extrahepatic malignancy and warrant future study.

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

References

- 1. Beste LA, Leipertz SL, Green PK, et al. Trends in burden of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma by underlying liver disease in US veterans, 2001‐2013. Gastroenterology 2015;149:1471‐1482.e5; quiz e17‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Estes C, Razavi H, Loomba R, et al. Modeling the epidemic of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease demonstrates an exponential increase in burden of disease. Hepatology 2018;67:123‐133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kanwal F, Kramer JR, Mapakshi S, et al. Risk of hepatocellular cancer in patients with non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology 2018;155:1828‐1837.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mittal S, El‐Serag HB, Sada YH, al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in the absence of cirrhosis in United States veterans is associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;14:124‐131.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Piscaglia F, Svegliati‐Baroni G, Barchetti A, et al. Clinical patterns of hepatocellular carcinoma in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a multicenter prospective study. Hepatology 2016;63:827‐838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Younossi ZM, Otgonsuren M, Henry L, et al. Association of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in the United States from 2004 to 2009. Hepatology 2015;62:1723‐1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Degasperi E, Colombo M. Distinctive features of hepatocellular carcinoma in non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;1:156‐164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker‐Thurmond K, et al. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults. N Engl J Med 2003;348:1625‐1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yang JD, Ahmed F, Mara KC, et al. Diabetes is associated with increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis from nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2020;71:907‐916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kanwal F, Kramer JR, Li L, et al. Effect of metabolic traits on the risk of cirrhosis and hepatocellular cancer in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2020;71:808‐819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Singal AG, El‐Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma from epidemiology to prevention: translating knowledge into practice. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:2140‐2151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wongjarupong N, Assavapongpaiboon B, Susantitaphong P, et al. Non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease as a risk factor for cholangiocarcinoma: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. BMC Gastroenterol 2017;17:149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fujiwara N, Nakagawa H, Enooku K, et al. CPT2 downregulation adapts HCC to lipid‐rich environment and promotes carcinogenesis via acylcarnitine accumulation in obesity. Gut 2018;67:1493‐1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wu H, Ng R, Chen X, et al. MicroRNA‐21 is a potential link between non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma via modulation of the HBP1‐p53‐Srebp1c pathway. Gut 2016;65:1850‐1860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Muir K, Hazim A, He Y, et al. Proteomic and lipidomic signatures of lipid metabolism in NASH‐associated hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res 2013;73:4722‐4731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ye J, Li TS, Xu G, et al. JCAD promotes progression of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis to liver cancer by inhibiting LATS2 kinase activity. Cancer Res 2017;77:5287‐5300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Verdelho Machado M, Diehl AM. The hedgehog pathway in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 2018;53:264‐278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ochoa B, Syn WK, Delgado I, et al. Hedgehog signaling is critical for normal liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy in mice. Hepatology 2010;51:1712‐1723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tovar V, Alsinet C, Villanueva A, et al. IGF activation in a molecular subclass of hepatocellular carcinoma and pre‐clinical efficacy of IGF‐1R blockage. J Hepatol 2010;52:550‐559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Adamek A, Kasprzak A. Insulin‐like growth factor (IGF) system in liver diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2018;19:1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hirsova P, Bohm F, Dohnalkova E, et al. Hepatocyte apoptosis is tumor promoting in murine nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Cell Death Dis 2020;11:80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kanda T, Matsuoka S, Yamazaki M, et al. Apoptosis and non‐alcoholic fatty liver diseases. World J Gastroenterol 2018;24:2661‐2672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fujiwara N, Friedman SL, Goossens N, et al. Risk factors and prevention of hepatocellular carcinoma in the era of precision medicine. J Hepatol 2018;68:526‐549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ma C, Kesarwala AH, Eggert T, et al. NAFLD causes selective CD4(+) T lymphocyte loss and promotes hepatocarcinogenesis. Nature 2016;531:253‐257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ritz T, Krenkel O, Tacke F. Dynamic plasticity of macrophage functions in diseased liver. Cell Immunol 2018;330:175‐182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ma C, Zhang Q, Greten TF. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease promotes hepatocellular carcinoma through direct and indirect effects on hepatocytes. FEBS J 2018;285:752‐762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Liu YL, Patman GL, Leathart JB, et al. Carriage of the PNPLA3 rs738409 C >G polymorphism confers an increased risk of non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease associated hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2014;61:75‐81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Llovet JM, Chen Y, Wurmbach E, et al. A molecular signature to discriminate dysplastic nodules from early hepatocellular carcinoma in HCV cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2006;131:1758‐1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Electronic address: wheeler@bcm.edu; Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network . Comprehensive and integrative genomic characterization of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell 2017;169:1327‐1341.e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Boursier J, Diehl AM. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and the gut microbiome. Clin Liver Dis 2016;20:263‐275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schwabe RF, Greten TF. Gut microbiome in HCC ‐ mechanisms, diagnosis and therapy. J Hepatol 2020;72:230‐238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Eslamparast T, Poustchi H, Zamani F, et al. Synbiotic supplementation in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled pilot study. Am J Clin Nutr 2014;99:535‐542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hamaguchi M, Hashimoto Y, Obora A, et al. Non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease with obesity as an independent predictor for incident gastric and colorectal cancer: a population‐based longitudinal study. BMJ Open Gastroenterol 2019;6:e000295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tilg H, Diehl AM. NAFLD and extrahepatic cancers: have a look at the colon. Gut 2011;60:745‐746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Brown JC, Harhay MO, Harhay MN. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and mortality among cancer survivors. Cancer Epidemiol 2017;48:104‐109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ahn JS, Sinn DH, Min YW, et al. Non‐alcoholic fatty liver diseases and risk of colorectal neoplasia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017;45:345‐353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sanna C, Rosso C, Marietti M, et al. Non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease and extra‐hepatic cancers. Int J Mol Sci 2016;17:717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wong VW, Wong GL, Tsang SW, et al. High prevalence of colorectal neoplasm in patients with non‐alcoholic steatohepatitis. Gut 2011;60:829‐836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kwak MS, Yim JY, Yi A, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with breast cancer in nonobese women. Dig Liver Dis 2019;51:1030‐1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Choi YJ, Lee DH, Han KD, et al. Is nonalcoholic fatty liver disease associated with the development of prostate cancer? A nationwide study with 10,516,985 Korean men. PLoS One 2018;13:e0201308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Farrell G. Insulin resistance, obesity, and liver cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;12:117‐119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]