Short abstract

Watch a video presentation of this article

Answer questions and earn CME

Abbreviations

- ACA

American College of Cardiology

- AHA

American Heart Association

- ASCVD

atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease

- CHD

coronary heart disease

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- FGF‐21

fibroblast growth factor 21

- FRS

Framingham Risk Score

- GLP1

glucagon‐like peptide 1

- HDL‐C

high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol

- IL‐6

interleukin‐6

- JNK

c‐Jun N‐terminal kinase

- LDL‐C

low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol

- NAFLD

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- NASH

nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

- NF‐κB

nuclear factor kappa B

- PAI‐1

plasminogen activator inhibitor 1

- SGLT2

sodium glucose co‐transporter 2

- TGF‐β

transforming growth factor‐β

- TNF‐α

tumor necrosis factor‐α

- USPSTF

US Preventive Services Task Force

- VLDL

very low‐density lipoprotein

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is associated with an increased risk for future cardiovascular disease (CVD), including coronary heart disease (CHD), heart failure, stroke, and arrhythmia. 1 CVD is one of the most common causes of death in patients with NAFLD; therefore, it is essential that hepatologists are aware of CVD risk factors and perform CVD risk stratification in this population. This brief review provides a pragmatic guide of CVD in NAFLD with a focus on CHD.

Epidemiology of NAFLD and CVD

NAFLD is the most common cause of liver disease worldwide, with an estimated prevalence rate of 25%. 2 Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) impacts between 2% and 7% of adults and can progress to cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma and require liver transplantation. Although liver‐related complications are a significant cause of mortality in NAFLD, CVD accounts for at least 40% of total deaths in NAFLD and thus is a predominant cause of death.

A number of studies have shown that NAFLD is a risk factor for CVD and in particular CHD, independent of traditional risk factors, such as age, sex, family history of CVD, obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and tobacco use. 3 , 4 Among adults with diabetes, radiographically diagnosed NAFLD is associated with an increased risk for fatal and nonfatal CVD events, defined as CHD events and cerebrovascular accident, independent of multiple CHD risk factors. In a cohort of Japanese patients, Hamaguchi et al. 4 showed that radiographically diagnosed NAFLD at baseline predicted future nonfatal CVD events defined as CHD, ischemia, and hemorrhagic stroke, independent of traditional risk factors. Further, a meta‐analysis of 16 observational studies demonstrated that compared with patients without NAFLD, patients with either imaging‐defined or biopsy‐proved NAFLD had a higher risk for fatal and/or nonfatal CVD events, and patients with advanced liver disease were more likely to have CVD events. 3 It is important to note that although it is likely that all subtypes of NAFLD are associated with increased CVD risk, data most strongly support an increased CVD risk in those with NASH and fibrosis. 3

Pathogenesis of NAFLD and CVD

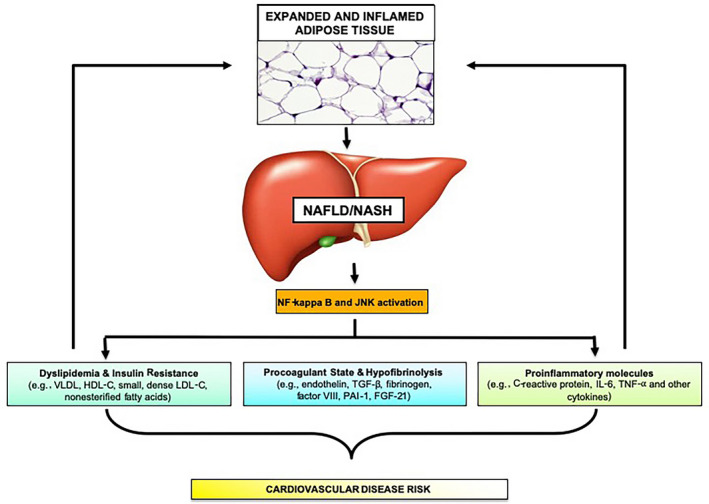

The precise causal mechanisms underlying the association between NAFLD and CVD are incompletely understood, although it is posited that the “drivers” of NAFLD progression, including systemic inflammation, dyslipidemia, and endothelial dysfunction, may also underlie accelerated atherogenesis. As NAFLD progresses, expansion and inflammation of intra‐abdominal visceral adipose tissue precipitate a proinflammatory cascade through the nuclear factor kappa B (NF‐κB) and c‐Jun N‐terminal kinase (JNK) pathways. The downstream sequelae are multiple and include systemic/hepatic insulin resistance caused by adipose tissue inflammation with accelerated hepatic steatosis; increased production of inflammatory cytokines by hepatocytes, Kupffer cells, and hepatic stellate cells; synthesis of procoagulant factors with hypofibrinolysis; and disordered lipid metabolism (Fig. 1).

FIG 1.

Pathogenesis of Cardiovascular Disease in NAFLD. NAFLD contributes to cardiovascular disease risk through dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, altered coagulation states and increased inflammation.

Several studies have suggested that severe hepatic necroinflammation and NAFLD progression are associated with CVD risk. A large prospective cohort study by DeFilippis et al. 5 demonstrated that imaging‐defined NAFLD was independently associated with atherogenic dyslipidemia in a dose‐dependent fashion, suggesting a close connection between NAFLD and dyslipidemia. In a cohort study by Ekstedt et al., 6 patients with biopsy‐proved NAFLD had an increased long‐term risk for death, with a high risk for death from CVD, compared with the reference population. In this study, advanced fibrosis was the strongest predictor for CVD mortality. In a prospective study, Henson et al. 7 showed that advanced fibrosis on biopsy and higher noninvasive fibrosis scores at baseline independently predicted incident CVD in patients with biopsy‐confirmed NAFLD, suggesting that progression of NAFLD begets increased CVD risk.

Recommendations For CVD Risk Management and Stratification in NAFLD

Risk Scores

Several CVD risk scores have been validated for the general population. The Framingham Risk Score (FRS) estimates 10‐year rates of CVD events, including CHD, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease, and congestive heart failure, to quantify risk in patients free of CVD. The atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk score estimates 10‐year primary risk for nonfatal myocardial infarction, CHD death, and stroke. The former has been validated in NAFLD and may be helpful to risk‐stratify individuals and guide treatment of CVD risk factors. 8 More robust validation of CVD risk scores is needed in the NAFLD population, with particular attention to advanced fibrosis.

Risk Stratification

CVD in NAFLD is associated with traditional and nontraditional CVD risk factors. Corey et al. 8 demonstrated that, in addition to traditional risk factors, CVD in NAFLD is independently associated with higher Model for End‐Stage Liver Disease scores, lower albumin, and lower sodium levels. A subsequent prospective study in patients with biopsy‐proved NAFLD showed that advanced fibrosis on biopsy and higher fibrosis scores were independent predictors of incident CVD. 7 Of the traditional risk factors, plasma low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL‐C) level has shown inconsistent association with CVD in the NAFLD population. Lower LDL‐C should not necessarily be taken as an indicator of low CVD risk because it may reflect lipid‐lowering therapy or advanced liver disease. NAFLD‐specific CVD risk scores, considering traditional and nontraditional CVD risk factors, are needed in this at‐risk population. In addition, the effect of NAFLD regression on CVD risk has not been well studied and requires future prospective evaluation.

Management

Management of NAFLD must extend beyond liver disease to include CVD risk modification to decrease CVD mortality. Clinicians should have heightened suspicion for CVD in patients with NAFLD, particularly in advanced liver fibrosis, and should routinely screen for tobacco use, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome. At present, management of patients with NAFLD is similar to the general population and includes CVD risk estimation, a healthy active lifestyle, smoking cessation, blood pressure management, diabetes optimization, and lipid lowering with statin therapy as first‐line treatment for CVD primary prevention 9 (Table 1). Importantly, statins are safe to use in NAFLD but are widely underutilized. 10 Sodium glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors and glucagon‐like peptide 1 (GLP1) receptor agonists are approved for patients with diabetes, reduce the risk for CVD, and should be considered in patients with both NAFLD and diabetes. Further evaluation should be considered in patients with NAFLD identified as high risk for CVD, including electrocardiogram, echocardiogram, coronary computed tomography angiography, and/or cardiac stress testing. Symptomatic patients and those with prior CVD events should be referred to a cardiologist. Collaboration with primary care physician and preventive cardiology may be helpful for CVD risk factor management. Thorough evaluation and thoughtful management of CVD risk among patients with NAFLD has the potential to significantly decrease morbidity and mortality in this population.

TABLE 1.

Recommendations for Risk Factor Management in NAFLD

| CVD Risk Factor | Source | Recommendation(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Diet | 2019 ACC/AHA Guidelines | Healthy diet |

|

||

| Exercise | 2019 ACC/AHA Guidelines | ≥150 min/week moderate‐intensity or ≥75 min/week vigorous‐intensity physical activity |

| Tobacco use | 2019 ACC/AHA Guidelines | Screen for tobacco use at every visit, and those who use tobacco should be assisted and strongly advised to quit |

| Blood pressure | 2019 ACC/AHA Guidelines | Nonpharmacological and/or pharmacological therapy with target blood pressure <130/80 mm Hg |

| Dyslipidemia | 2019 ACC/AHA Guidelines | Statin therapy as the first‐line treatment for CVD primary prevention in patients with elevated LDL‐C levels ≥190 mg/dL, established diabetes, age 40‐75 years, and/or elevated ASCVD score |

| Diabetes | USPSTF | Screen adults 40‐70 years old every 3 years for abnormal blood glucose and diabetes |

| 2019 ACC/AHA Guidelines | Metformin is the first‐line therapy, followed by consideration of a SGLT2 inhibitor or a GLP1 receptor agonist |

CVD, driven largely by CHD, is one of the most common causes of death among patients with NAFLD. The inflammatory cascade driving NAFLD progression simultaneously accelerates atherogenesis through cytokine production, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, and procoagulant imbalance. NAFLD‐specific CVD risk scores and consideration of traditional and nontraditional CVD risk factors should be used to risk‐stratify those with NAFLD. FRS can be used in lieu of NAFLD‐specific scores. CVD risk factor management includes promotion of a healthy active lifestyle, smoking cessation, blood pressure management, diabetes optimization, and lipid‐lowering therapy with statins as a safe and first‐line treatment for primary prevention of CVD in NAFLD.

Financial support: This study was supported in part by internal grants from the University School of Medicine of Verona, Verona, Italy (to G.T.).

Potential conflict of interest: M.R. is on the speakers’ bureau for and received grants from Boehringer‐Ingelheim; is on the speakers’ bureau for, consults for, and received grants from Sanofi US; consults for Eli Lilly, Terra Firma, Fishawach Group, Target Pharmasolutions, Gilead, Kenes Group, BMS, Intercept, Inventiva, and Astra Zeneca; advises Poxel S.A. and Servier Labatories; is on the speakers’ bureau for Novo Nordisk and Allergan; and received grants from Novartis and Nutriticia/Danone. K.E.C. consults for, advises, and received grants from BMS; consults for and advises Novo Nordisk; and has received grants from Boehringer‐Ingelheim.

References

- 1. Eslam M, Newsome PN, Sarin SK, et al. A new definition for metabolic dysfunction–associated fatty liver disease: an international expert consensus statement. J Hepatol 2020;73:202‐209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, et al. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: meta‐analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology 2016;64:73‐84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Targher G, Byrne CD, Lonardo A, et al. Non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease and risk of incident cardiovascular disease: a meta‐analysis. J Hepatol 2016;65:589‐600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hamaguchi M, Kojima T, Takeda N, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is a novel predictor of cardiovascular disease. World J Gastroenterol 2007;13:1579‐1584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. DeFilippis AP, Blaha MJ, Martin SS, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and serum lipoproteins: the Multi‐Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 2013;227:429‐436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ekstedt M, Hagstrom H, Nasr P, et al. Fibrosis stage is the strongest predictor for disease‐specific mortality in NAFLD after up to 33 years of follow‐up. Hepatology 2015;61:1547‐1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Henson JB, Simon TG, Kaplan A, et al. Advanced fibrosis is associated with incident cardiovascular disease in patients with non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2020;51:728‐736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Corey KE, Kartoun U, Zheng H, et al. Using an electronic medical records database to identify non‐traditional cardiovascular risk factors in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2016;111:671‐676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2019;140:e563‐e595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Blais P, Lin M, Kramer JR, et al. Statins are underutilized in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and dyslipidemia. Dig Dis Sci 2016;61:1714‐1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]