Abstract

Globalization entails several medical problems along with economic and social complications. Migrations from other continents, increasing numbers of tourists worldwide, and importation of foreign parasites (eg, Aedes albopictus) have made diseases previously unknown in Europe a reality. The rapid spread of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic throughout the world is a warning that other epidemics are still possible. Most, if not all of these diseases, transmitted by viruses or bacteria, present with cutaneous symptoms and signs that are highly important for a speedy diagnosis, a fundamental concept for arresting the diseases and saving lives. Dermatologists play a significant role in delineating cutaneous and mucosal lesions that are often lumped together as dermatitis. We provide a review of many of these cutaneous and mucosal lesions that sometimes are forgotten or even ignored.

Introduction

Enanthem is defined as any eruptive lesion on the mucous membranes. It may be associated with fever or other constitutional symptoms and can be caused by infectious diseases or adverse reactions to drugs. A mixed etiology is also possible. Enanthems may precede, occur with, or follow fever and other constitutional findings. They may precede or be associated with an exanthem, namely any eruptive skin dermatitis. The etiologic diagnosis of an exanthem, especially when atypical, is often challenging, but it is crucial for the patient and community considering issues such as time off from school, immunization, and risks for pregnant women and immunocompromised patients. Skin changes in acutely ill patients are often puzzling, but the picture becomes even more challenging, when the mucous membranes are involved. In some instances, the enanthem can provide clues to diagnosing an exanthem, such as Köplik spots for measles.

A correct diagnosis is always significant, because the prompt discontinuation of an offending drug may limit an adverse reaction and subsequent systemic toxicity. The diagnosis, however, often requires specialized, time-consuming procedures that are often prohibitive, such as serologic and/or polymerase chain reaction tests. Many times, the dermatologist may truncate the process through an accurate recognition of the mucocutaneous features, studying the patient's history of infectious diseases and drug intake, and carefully inspecting the prodromal signs/symptoms.

Enanthems associated with viral infections—human herpesviruses

There are eight species of human herpesviruses belonging to the Herpesviridae family. The most well-known, herpes simplex virus (HSV), exists in two serotypes: HSV-1 and HSV-2. The remaining species include the varicella-zoster virus (VZV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), human herpesvirus (HHV)-6, HHV-7, and HHV-8.1

HSV-1 and HSV-2

HSV are enveloped, linear, double-stranded DNA viruses that can establish a lifelong latency in the host after the primary infection, like other herpesviruses. The latent infection may remain silent, but it can reactivate periodically causing symptoms and signs. HSV-1 and HSV-2 are closely related, and more than 50% of their DNA sequences are homologous. HSV infections may affect any cutaneous or mucous site, causing an eruption of grouped, painful vesicles on an erythematous basis. HSV-1 is mostly associated with orofacial diseases, whereas HSV-2 may be found in genital or perigenital infections; the theory, however, that HSV-1 and HSV-2 cause infections “above and below the belt,” respectively, is an oversimplification. Their primary transmission occurs through infected saliva or direct contact of mucocutaneous lesions, with the majority of the infections being unapparent.

Herpetic gingivostomatitis is the most common acute clinical manifestation of primary HSV infection, usually due to HSV-1, that occurs between the ages of 6 months and 5 years. It generally presents with flu-like manifestations (fever, chills, and cervical and submandibular lymphadenopathy), intraoral mucosal vesicles (usually 2-3 mm in size), involving the gingiva, lips, hard and soft palate, tongue, buccal mucosa, and perioral areas. The vesicles may coalesce, especially on the mucosa of the cheeks and under the tongue, forming ulcers surrounded by erythema. The lips and gingiva may be swollen, and the lesions, being painful, may resemble those of aphthous stomatitis and could prevent feeding of the child. In children, the skin around the mouth is usually involved, whereas in adults the lesions are usually restricted to the lips. The fever lasts a few days, whereas oral lesions take 2 to 3 weeks to heal without scarring. Lymphadenopathy can persist for many weeks. Exudative ulcerative lesions involving the posterior part of the pharynx or tonsils can be difficult to distinguish from streptococcal pharyngitis or from coxsackievirus (CV) infection. CV infections (herpangina) cause vesicular lesions more frequently involving the soft palate than the hard one and are usually associated with vomiting and abdominal symptoms. Gingivostomatitis can be caused by other organisms (eg, Candida, Leptospira) or by other factors, including medications, Behçet's syndrome, hypovitaminosis, or hyposideremia, but the acute, febrile disease involving the gums and jaw is mostly caused by HSVs.

HSV primary infections can also affect the eye, although most eye involvement is due to viral reactivation. HSV-2 transmission may occur during the peripartum period owing to the disrupted membranes and/or with direct contact with the infected mother's vaginal secretions, causing ocular lesions in newborns. The lesions only involve the external eye, causing conjunctivitis and dendritic keratitis, but stromal keratitis and iridocyclitis can be observed. The preauricular lymph nodes enlarge. Corneal scarring may occur, if there are multiple recurrences.

Genital and perigenital HSV primary infection is transmitted mainly in a sexual mode. It is very rare in children before puberty and increases rapidly after the onset of sexual activity. In comparison with other forms of HSV infections, genital primary infection can be very concerning, especially in individuals who have not previously been exposed to HSV. The clinical course of herpes genitalis is similar with both viruses, but HSV-2 can cause more recurrences of genital sores than HSV-1. Grouped vesicular lesions, pustules, and erythematous ulcers tend to cover a larger area of the skin and mucous membranes in women than in men. In men, the ulcers are more frequent on the glans, prepuce, and penile shaft, where they may be very painful. In women, analogous lesions occur on the external genitalia and mucosae of the vulva, vagina, cervix, and perineum. The lesions may be associated with pain, dysuria, vaginal and urethral discharge, and inguinal lymphadenopathy, along with fever, myalgias, or headaches. HSV cervicitis is frequently present with extensive ulcerative lesions of the exocervix and mucopurulent vaginal discharge. Aseptic meningitis and radiculopathy may be seen in women, whereas perianal disease in homosexual men may be associated with paresthesia, urinary retention, and constipation.2, 3, 4 Fortunately, recovery may occur within a few weeks.

VZV

VZV belongs to the Herpesviridae family and has been related to chickenpox and shingles. Chickenpox is the primary infection of VZV, and it spreads between children by direct contact or airborne droplets. After a 2 3week incubation period, it begins with a prodromal period characterized by malaise, low-grade fever, headache, anorexia, and pharyngitis. An enanthem, consisting of small erythematous vesicles on the buccal mucosa that rapidly turns into shallow ulcers, may occur 1 to 3 days earlier than the exanthem, or at the same time. Mucosal lesions can also involve the nose, conjunctivae, larynx, trachea, gastrointestinal tract, urinary tract, and genitals. Oropharyngeal lesions are less numerous and confluent than in HSV primary infection, and there is no associated gingival swelling. The typical exanthem is characterized by pruritic erythematous macules and papules, beginning on the scalp and face and spreading to the trunk and extremities. Lesions rapidly evolve from maculopapular to elliptical vesicles on an erythematous base, giving them their distinctive “dewdrop on a rose petal” appearance. These lesions change to small pustules after 10 to 12 hours and finally evolve into crusts, lasting 1 to 2 weeks. Residual areas of hypopigmentation may be seen. New crops of lesions appear over 2 to 4 days, and a distinctive feature is the presence of lesions at different stages of development in each site.5, 6, 7, 8

The reactivation of VZV during adulthood is related to shingles. VZV remains latent in the neurons of the cranial nerve and dorsal root ganglia and travels to the skin. Shingles is characterized by painful and itchy erythematous grouped vesicles localized to a truncal dermatome. Although shingles do not present a typical enanthem, Ramsay Hunt syndrome may occur. This is a disease caused by VZV reactivation in the geniculate ganglion of the facial nerve, an ipsilateral vesicular stomatitis involving the anterior two-thirds of the tongue and the soft palate may occur. There may be vesicles on the external ear with ipsilateral hearing loss, ipsilateral facial palsy, and vertigo.9

CMV

CMV is a very common, usually unapparent worldwide infection that can be transmitted during close person-to-person contact and through oral/vaginal secretions, urine, semen, placenta, breast milk, blood transfusions, and organ transplantations.7 , 10 There are maculopapular, urticarial, and scarlatiniform eruptions with oral lesions being rare and more commonly associated with immunosuppression, especially in organ transplanted or patients with HIV. In such immunosuppressed patients, CMV and HSV-1 may coexist and produce painful ulcerations on the edge of the tongue, lips, and mucous membranes. CMV ulcerations are nonspecific and occur more frequently in patients with AIDS that usually present with keratotic skin lesions and mucosal/skin ulcerations. The virus may also be related to gingival overgrowth and periodontal disease.10, 11, 12 In immunosuppressed patients, oral ulcerative lesions may also be caused by simultaneous infection with CMV and other herpesviruses such as EBV, HHV-6, and HHV-8. Coinfection with EBV/CMV may cause macular and papular eruptions, along with palatal petechiae.13 , 14

EBV

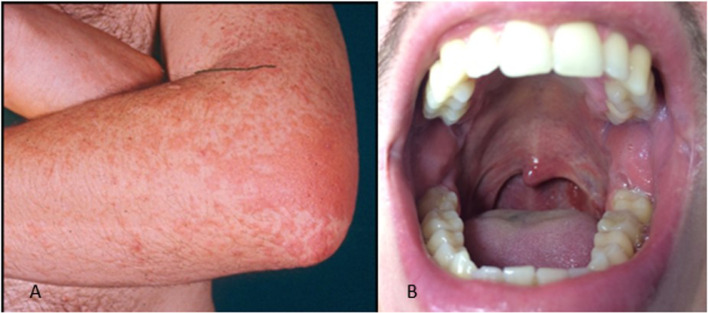

EBV is a very common ubiquitous herpesvirus which is spread by contact with saliva. EBV infection is usually asymptomatic in children, whereas in adolescents and adults, it often results in infectious mononucleosis (IM). Skin lesions occur in about 2% to 3% of patients with acute IM. The eruption is usually maculopapular (morbilliform) and lasts for a few days, but many patients may exhibit atypical forms. A maculopapular eruption, often involving the palms and soles, develops in most patients 7 to 10 days after therapy with ampicillin or with other beta-lactam antibiotics (Figure 1 A).5, 6, 7 Eyelid and widespread petechiae, periorbital edema usually not accompanied by conjunctivitis (“Hoagland Sign”),15 and urticarial lesions have been described during IM. There may be a maculopapular enanthem and petechiae, localized between the hard and soft palate, often coalescing (Figure 1B).5, 6, 7 , 16 In case of coinfection with CMV, the skin eruption may be associated with palatal petechiae.

Fig. 1.

A, Maculopapular exanthem and B, maculopapular enanthem with petechiae during infectious mononucleosis.

Recent studies have also implicated EBV in the pathogenesis of advanced types of periodontal disease.17 The presence of EBV DNA may be found in 60% to 80% of aggressive periodontitis and in 15% to 20% of gingivitis. EBV and CMV often coexist in marginal and apical periodontitis. A recent study reported that EBV could induce gingivitis and/or periodontitis in an immune permissive environment, such as in organ transplanted patients.18 Oral hairy leukoplakia (OHL) is a disease of the mucosa associated with EBV infection and developing mostly in patients infected with HIV, as well as in HIV-negative patients with organ transplants or immunocompromising diseases. Its appearance may have diagnostic and prognostic implications for the underlying condition.

OHL appears as a white patch on the lateral surfaces of the tongue, unilaterally or bilaterally, with a corrugated or hairy appearance which cannot be scraped off. The lesions may sometimes involve the buccal mucosa, palate, or pharynx. The pathogenesis of OHL is unclear; the virus, however, may be recovered from the upper layers of the epithelium. EBV active replication is indicated by the presence of antigens and linear EBV DNA in the cells of the lesion. The upregulation of cytokines and growth factors induced by EBV plays a role in the proliferative response of tongue epithelial cells.17

HHV-6 and HHV-7

Commonly spread by saliva, HHV-6 and HHV-7 usually create lifelong latency. HHV-6 and, less frequently, HHV-7 primary infection causes exanthema subitum, the most common exanthematic fever in children under the age of 3 years. In patients with exanthema subitum due to HHV-6, uvulo-palatoglossal junctional ulcers provide a useful pathognomonic clinical sign of symptomatic primary HHV-6 infection.5, 6, 7 , 19 , 20 Nagayama spots, another enanthem associated with HHV-6 primary infection, are erythematous macules and papules found on the soft palate and uvula. These can be seen in two-thirds of patients with exanthema subitum. When there is endogenous systemic reactivation, HHV-6 and HHV-7 may be involved in other diseases, especially pityriasis rosea (PR).

PR begins with a single, oval, erythematous scaly plaque (mother patch) that is followed within 14 days by a secondary eruption consisting of smaller scaly macules and papules distributed along the cleavage lines of the trunk, giving the back the configuration of a Christmas tree or a theater curtain (Figure 2 A). The eruption lasts from 2 weeks to a few months (45 days on average).5, 6, 7 , 19 Oropharyngeal lesions have been described in about 30% of patients with PR following the course of the skin eruption, disappearing with skin eruption of PR or a few days later.19 Petechial, macular, and papular are the most frequently observed enanthem patterns, with the presence of oropharyngeal lesions often associated with systemic findings (Figure 2B).5, 6, 7 , 19 , 21 , 22

Fig. 2.

Pityriasis rosea. A, Scaly erythemato-macules and papules distributed along the cleavage lines of the trunk. B, Erythemato-macules and petechie in the hard palate.

HHV-8

HHV-8 is transmitted to humans by sexual contact, salivary secretion, blood transfusions, and/or organ transplant. It is associated with vascular neoplasms, angiogenesis, inflammation, and cellular proliferation. The infection has been associated with several diseases, including Kaposi sarcoma (KS), lymphomas, and multicentric Castleman disease. KS is classified in four different types: AIDS-associated, which involves the viscera and lymph nodes; transplant or iatrogenic; classic or sporadic; and endemic.

Characteristic signs include pigmented violaceous compressible nodules in the skin with asymmetric linear distribution on the legs, soles, back, face, or genitalia. The clinical features of oral involvement are maculopapular (75%) or nodular (14%), plus proliferative lesions such as tumors (11%) primarily on the hard palate followed by involvement of the oropharynx. The tongue, gingiva, and oral mucosa are less commonly involved. All of these lesions may bleed after eating.7 , 23 The more aggressive AIDS-related and transplant/iatrogenic KS types often involve the oropharyngeal mucosa and may cause gingival hyperplasia.24

Measles virus

Measles virus is a highly contagious RNA enveloped virus and a member of the family Paramyxoviridae. It is spread via airborne droplets and respiratory secretions, entering through the nasopharyngeal respiratory epithelium or conjunctiva. It is commonly seen in unvaccinated children after an incubation period lasting from 10 to 12 days. The prodromal stage of measles is characterized by a persistent high fever, coryza, cough, photophobia, conjunctivitis, and oropharyngeal lesions, known as Köplik spots. They are pathognomonic of the disease and provide an opportunity to diagnose measles, just by clinical observation, a day or two before the onset of the dermatitis. Köplik spots, which persist for up to 40 hours after the onset of the exanthem, consist of small, red macular lesions with a bluish-white center, resembling salt grains upon an erythematous base. They are found on the buccal mucosa opposite to the premolars or molar teeth (Figure 3 ). Later, the lesions may coalesce and spread to involve the entire buccal mucosa and the palate. Köplik spots are found in at least 50% to 70% of patients with measles. Occasionally, they also occur on the conjunctiva, vagina, or the gastrointestinal mucosa. Although diagnostic of measles, similar lesions may occur during acute parvovirus B19 (PB19 V) and echovirus 9 infections.7 , 25 , 26 Although not pathognomonic, other lesions may precede Köplik spots. A series of pinpoint red elevations connected by a network of tiny vessels with scattered petechiae may be present on the soft palate. The pharynx usually shows a widespread redness and bluish-gray white patches (ie, Hermann spots), observed on the tonsils. The measles exanthem consists of erythematous macules and papules, sometimes confluent, that appear 3 to 4 days after the onset of fever, first on the face and behind the ears, and then on the trunk and extremities, coinciding with development of the adaptive immune response. The fever and catarrhal symptoms typically peak with the eruption, which persists for 3 to 4 days. Recovery occurs within 1 week of the exanthem onset in patients with uncomplicated disease.7 , 25, 26, 27

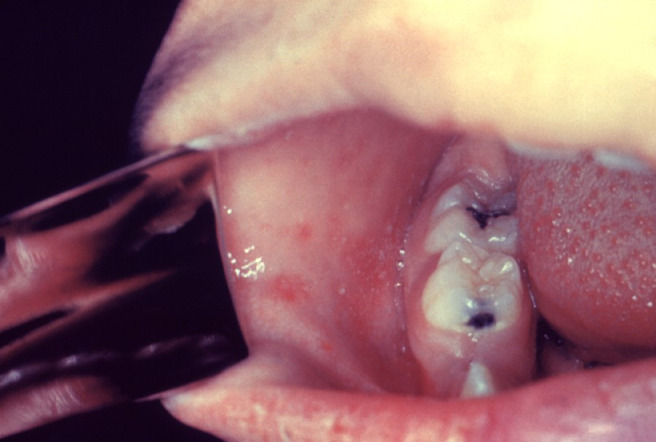

Fig. 3.

Köplik spots in measles: small, bright red spots with a white center on the buccal mucosa, opposite to the premolars or molars ; the spots are indicative of the onset of measles. Reproduced with permission from CDC Public Health Image Library.

PB19 V

PB19 V is the etiologic agent of erythema infectiosum (fifth disease) characterized by a “slapped cheek appearance” and an erythematous maculopapular exanthem involving the trunk and extremities.7 The lesions fade centrally with a typical lacy appearance. It is mainly a childhood disease, whereas arthralgias and arthritis with or without dermatitis are more common in adults.28, 29, 30 In young adults 20 to 40 years of age, a gloves-and-socks syndrome could occur during the spring and summer, regardless of sex. This syndrome is characterized by the painful pruritic edema and erythema, rapidly evolving to papular-purpuric lesions on the distal extremities in a gloves-and-socks fashion and may be accompanied by fever.7 Oral lesions include petechiae, vesico-pustules, and small erosions developing on the lips, buccal mucosa, and soft palate.31 PB19 V oral lesions may mimic Köplik spots.25

Enteroviruses

CV

CVs are the most frequent cause of herpangina and hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD). The causative agent of herpangina is most commonly CV group A and sometimes CV group B, echoviruses, adenoviruses, and parechovirus 1. The involved types change depending on the outbreak and the geographic region. Primarily, herpangina affects children younger than 10 years of age in the summer or early autumn.1 , 7 It begins with fever and malaise, followed by lymphadenopathy, sialorrhea, and a typical enanthem characterized by a few painful grayish-white papulovesicular lesions that rapidly evolve into shallow ulcerations with a red rim on the soft palate, uvula, tonsils, and pharynx.1 Skin lesions are usually absent. Oral lesions may change depending on the involved type. Typical herpangina-like lesions in the whole mouth, except for the posterior aspect of the pharynx, are detected in CV-A16 or A5 infections, whereas vesicular pharyngitis may occur in CV-B5. CV-A9 and CV-A4 are rarely associated with herpangina-like lesions in the mouth.32 , 33

Enteroviruses may also produce a maculopapular eruption or HFMD, often associated with systemic symptoms.7 , 34 , 35 CV, mainly A16, causes HFMD, a highly contagious infection that begins with an incubation period of 3 to 7 days and is characterized by nonspecific constitutional symptoms, such as malaise and low-grade fever. Shortly thereafter, the patient complains of a sore throat with papulovesicular lesions that rapidly erode, developing shallow ulcerations (Figure 4 A). Generally, the enanthem starts before the exanthem. The latter consists of painful papulovesicular lesions on the extensor surfaces and sides of the fingers, hands, toes, and feet (Figure 4B-D). Less commonly, lesions may be present on the buttocks36 and genitalia. Oral manifestations in HFMD should be differentiated from aphthous stomatitis or HSV infection. Atypical HFMD has bee has been reported worldwide, caused by CV-A6 and CV-A10.7 , 34, 35, 36 It is characterized by a relative paucity of oral lesions and vesico-bullous lesions that have a wider distribution on the extremities and trunk than typical HFMD. Perioral erythematous papules can be seen only in atypical HFMD due to CV-A6. Another oropharyngeal involvement without skin lesions may be caused by group A CV. It is an acute lymphonodular pharyngitis, consisting of raised, tiny nodules in the soft palate and tonsils that resolve without ulceration.7

Fig. 4.

Infection by Coxsackievirus A16 causing HFMD. A, Erythematous macules and vesicles plus shallow ulcerations on an erythematous base on the hard palate. Erythematoous papules and vesicles on the B, dorsum of the hands, C, palms, and D, soles. HFMD, hand-foot-and-mouth disease.

Echoviruses

Echovirus 9 infection is characterized by fever and a maculopapular/petechial eruption, beginning on the face or neck and spreading over the body. Signs of neurologic involvement can mimic meningococcal meningitis or rickettsial disease. Punched-out ulcers on the soft palate or tonsillar pillars and grayish-white dots are similar to Köplik spots and may occur as typical enanthem. Similar ulcers, accompanied by a pink maculopapular dermatitis, especially on the face and trunk, are also present in the so-called Boston exanthem. This consists of a maculopapular dermatitis that develops as fever abates, involving the face and neck first, then spreading over the body. It is caused by echoviruses35, 36, 37 which may also cause a nonspecific enanthem with macular and papular lesions.7

Adenoviruses

Human adenoviruses are responsible for 7% to 8% of all pediatric respiratory illnesses. They can cause upper respiratory symptoms with fever, myalgia, cough, otitis and pharyngitis, and exudative tonsillitis. There may be cervical adenopathy pharyngitis, reminiscent of the condition associated with group A streptococcal pharyngitis. Adenovirus serotypes 3, 4, and 7 may also cause a distinct syndrome consisting of conjunctivitis, pharyngitis, fever, preauricular lymphadenopathy (pharyngoconjunctival fever), and gastroenteritis.38 In patients coinfected with EBV/CMV or other respiratory agents, the maculopapular skin eruption may be associated with a nonspecific palatal petechiae.39

HIV

More than 90% of patients with HIV infection develop oral manifestations during the course of the disease, and in 10% of cases, oral lesions are the presenting signs of the illness.40 In the immunocompromised host, the altered oral microbiota help to facilitate the reactivation of herpesviruses and the activity of other pathogens in the oral cavity. Oral lesions caused by opportunistic organisms are remarkable indicators of the immune status. Oral infections can forecast the progression of HIV infection to AIDS, frequently signaling the morbidity and mortality of the illness.41 Six paramount lesions are frequently related to HIV infection: Oral candidosis, oral hairy leucoplakia, Kaposi sarcoma, necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis, linear gingival erythema, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.42

Sometimes patients develop recurrent painful oral/genital erosions that significantly interfere with their quality of life. These ulcerative diseases can be due to HSV-1/2 or are aphthous-like lesions due to neutropenia or unknown origin.42 The advent of highly active antiretroviral therapy has contributed to the decrease in the prevalence of oral candidosis and oral hairy leucoplakia in adults but not in children.43

Viruses transmitted by arthropods: Arboviruses

Arboviruses (arthropod-borne viruses) include several families of viruses that are spread by arthropod vectors, most commonly mosquitoes, ticks, and sand flies.44, 45, 46, 47 The families of viruses included in the arbovirus group are Flaviviridae, Togaviridae, Bunyaviridae, and Reoviridae. These large families have, in common, an RNA genome that allows such viruses to adapt rapidly to ever-changing host and environmental conditions. These virus families are largely responsible for the recent growth in the geographic range of emerging viruses, such as West Nile virus, dengue virus (DENV), and chikungunya virus (CHIKV).

Bunyaviridae

Bunyaviruses

Bunyaviruses are associated with two severe hemorrhagic fevers: Rift Valley fever (RVF) and Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (CCHF). CCHF virus is responsible for CCHF in Europe, the Middle East, Asia, and Africa with high mortality. It is transmitted to humans by ixodid ticks or by contact with tissues and fluids of infected animals or humans. The disease begins with fever, conjunctivitis, hypotension, cutaneous flushing or dermatitis and is followed by signs of progressive hemorrhagic diathesis consisting of petechiae and large ecchymosis.7 A petechial enanthem may also occur.47, 48, 49 RVF virus has been isolated in southeastern/western/northern Africa, as well as Madagascar and Yemen. It is transmitted to humans by Aedes mosquitoes. The hallmarks of RVF include myalgia, headache, dizziness, mood swings, and diarrhea. In 1% of patients, there is a petechial enanthem and ecchymoses, and additional hemorrhagic manifestations involve oral and pharyngeal mucosae.7 , 47

Hantaviruses

Hantaviruses are single-strand RNA viruses that recently have become a major concern in the United States. Hantaviruses are transmitted by aerosol, saliva, and urine of rodents. Typically, they cause fever, headache, myalgia, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain, as well as a characteristic facial flushing and a petechial dermatitis often limited to the axillae.47 A subsequent cardiopulmonary phase is characterized by tachypnea, tachycardia, and hypotension. The disease can evolve into rapid respiratory failure and lactic acidosis.48 Hantaviruses rarely may be implicated in hemorrhagic manifestations, including hematuria, nasal bleeding, gingival bleeding, and cutaneous findings that includes petechiae, purpura, and ecchymoses.47

Flaviviridae

Flaviviruses include many single-stranded RNA enveloped arboviruses that cause dengue fever, Zika fever, yellow fever, Omsk hemorrhagic fever, and Kyasanur Forest disease.

DENV

Dengue is caused by \DENV, of which four serotypes are known: DENV1, DENV2, DENV3, and DENV4. It is the most common arbovirus illness in humans. DENV is essentially a tropical infection, epidemic and endemic in tropical South America, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Southeast Asia,46 , 47 but currently it is becoming a global concern. DENV is transmitted by the Aedes mosquitos. After an incubation period of 5 to 8 days, classic dengue, also called “breakbone fever,” begins with the sudden onset of high fever lasting 2 to 5 days, accompanied by fatigue, anorexia, headache, backache, myalgias, arthralgias, and generalized lymphadenopathy. Scleral injection and retroorbital pain are common. Respiratory symptoms are rare. Macular and maculopapular exanthems are frequently present on the trunk and the inner aspect of the arms. The skin lesions may be pruritic and generally resolve with desquamation. About 50% of patients have a pinpoint-size vesicular enanthem with petechiae on the soft palate. The tongue is often coated with protruding red hypertrophied papillae, known as the strawberry tongue.

Dengue is more frequently reported in people who are infected by two specific serotypes of the virus. Its course is more severe than the classic dengue and includes vomiting, facial flushing, circumoral cyanosis, and weakness. Oral mucosal lesions, especially petechiae, purpura, and gingival bleeding, may also be present. Additional minor and major bleeding are also reported, including epistaxis, menorrhagia, and gastrointestinal hemorrhage associated with high fever, convulsions, and shock.7 , 46 , 47

Zika virus

Zika virus (ZIKV) is transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes and is spread worldwide. Spread of the virus through sexual contact and blood transfusion have been reported. The clinical presentation of Zika fever is nonspecific and can be misdiagnosed as other infectious diseases, especially dengue and chikungunya.7 The infection is usually asymptomatic (80%), but it can cause fever, headache, myalgias, arthralgias, exanthem, and conjunctivitis. Symptoms usually last 4 to 7 days. During pregnancy, ZIKV infection can cause a miscarriage and result in microcephaly and eye abnormalities.22 Infection by ZIKV is characterized by a diffuse, usually pruritic, maculopapular eruption that may be observed in up to 98% of the patients, also in association with conjunctivitis and edema of the hands and feet lasting only a few days.7 Lesions are usually generalized, following a symmetric pattern involving the face, neck, trunk, palms, and soles. Patients may also show salmon-pink papules and scaling psoriatic-like plaques, resembling those of eruptive guttate psoriasis.50 During ZIKV infection, oral lesions are mainly hemorrhagic. Petechiae and ecchymosis on the palate, gingival bleeding, and aphthous and ulcerative lesions have been described.51

Yellow fever virus

Yellow fever virus is endemic in equatorial Central and South America and Africa and is transmitted to humans by bites of mosquitos of the Aedes and Haemogogus genera which are reservoirs and vectors. Yellow fever begins with an initial acute phase similar to classic dengue, followed in 15% of the patients by a “toxic phase” that consists of severe abdominal pain, vomiting, jaundice, petechiae, and skin hemorrhages. Examination reveals a flushed face and conjunctival injection. There may be oral mucosal bleeding, as well as hematemesis and bleeding of the nose and eyes. The tongue characteristically shows bright-red margins and a white furred center.7 , 46 , 47

Omsk hemorrhagic fever and Kyasanur Forest disease viruses

These viruses are distributed in Siberia and India, respectively, and are transmitted by tick bites, contact with the blood, feces, or urine of infected hosts and through aerosol spread. Omsk hemorrhagic fever is associated with headache, fever, myalgia, loss of taste, occipital rigidity, and sometimes bruises. A petechial enanthem may also be found. Kyasanur Forest disease is very similar to Omsk disease, and it is characterized by petechial hemorrhages and bleeding of the mouth and mucous membranes.7 , 52

Togaviridae

Alphaviruses

Alphaviruses are six single-stranded RNA viruses.52 CHIKV, Ross River virus (RRV), Barmah Forest virus (BFV), O'nyong-nyong virus, Sindbis virus, and Mayaro virus are all transmitted to humans by mosquitoes.53 Regular epidemics of CHIKV occur in Sub-Saharan Africa, India, and Southeastern Asia. RRV and BFV are distributed in Australia, O'nyong-nyong in Africa, Sindbis virus in Africa, Asia, and northern Europe, and Mayaro virus in northern parts of South America.53 The incubation period lasts up to 15 days and may be followed by the triad of fever, arthralgia, and dermatitis. Typically, alphaviruses cause an early disease phase, characterized by fever, malaise, muscle pains, headache, nausea, and retro-orbital pain. Arthralgia and dermatitis may occur in varying order, depending on the type of alphavirus. RRV causes the dermatitis before, at the same time, or after the arthropathy. The dermatitis, which lasts 2 to 10 days, is usually maculopapular, begins on the cheeks and forehead, and may involve the trunk and extremities. It may be pruritic. Scattered petechiae have also been reported in RRV infection, and vesicles on the palms and soles may occur in infections due to RRV, BFV, and Sindbis virus.52, 53, 54 Very few findings have been reported on the oral mucosa or for a sore throat. O'nyong-nyong and Mayaro viruses may induce severe bleeding of the mucous membranes and skin with bleeding gums, petechiae, purpura, melena, and hematemesis.54

CHIKV is a mosquito-transmitted alphavirus that causes a febrile illness associated with severe arthralgia, myalgia, and a skin eruption. The increase in traveling and migration facilitates spread of the virus. Through a mosquito bite, the virus directly enters the subcutaneous capillaries and skin macrophages, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells. Local viral replication seems to be negligible, but the virus spreads rapidly through the blood and lymphatic vessels with subsequent development of a high-grade fever, rigors, headache, myalgias, and arthralgias primarily affecting the larger joints. In 50% to 80% of the patients, a petechial or transient maculopapular dermatitis occurs, sparing the face and involving the trunk, and occasionally, the arms and legs. In addition, other cutaneous and mucosal manifestations may be observed: Red lunula, subungual hemorrhage, localized erythema of the pinnae, swelling and eczematous changes over preexisting scars and striae (scar phenomenon), together with diffuse facial hyperpigmentation mainly involving the nose. Mucous membrane involvement is more frequent in men than in women and is characterized by aphthous-like ulcers and stomatitis. There may also be painful genital ulcers on the scrotum and vulva.

Viruses transmitted by rodents

Arenaviruses

Arenaviruses are pleomorphic enveloped RNA viruses that are responsible for severe hemorrhagic fevers. They are transmitted to humans by contact or inhalation of excreta of several rodents, including mice in the Old World (Lassa virus) and in the New World (Junín virus, Machupo virus, Guanarito virus, and Sabiá virus). The detection of cutaneous and mucosal manifestations in hemorrhagic fevers may be helpful for an early diagnosis in febrile patients returning from endemic areas, such as South America or Africa.7 , 47 , 55

Classic New World arenaviruses

Hemorrhagic fevers include Argentine hemorrhagic fever caused by the Junín virus, Bolivia hemorrhagic fever by the Machupo virus, Venezuelan hemorrhagic fever by the Guanarito virus, and Brazilian hemorrhagic fever by the Sabiá virus. These fevers have an incubation period lasting 6 to 14 days and include a prodromal phase with malaise, chills, anorexia, headache, myalgia, and hyperthermia (38°C-39°C), commonly followed in a week by erythema of the face and trunk, coupled with cutaneous petechiae in the axillary area and upper portion of the chest. There is almost always a petechial-vesicular enanthem over the soft palate.55 About 20% to 30% of these fevers are complicated by a neurologic-hemorrhagic phase with shock and bacterial complications that occur 8 to 12 days after the appearance of the incubation findings. There is generally minimal gingival bleeding and disseminated non-palpable petechiae. In the final convalescence phase, patients experience irritability, asthenia, memory changes, and hair loss.55

Old World arenaviruses

Lassa virus

Lassa virus is usually responsible for the so-called Lassa fever, especially in West Africa. Fever, headache, chills, retro-orbital pain, and myalgia develop after an incubation period of 6 to 14 days. In addition, flushing and edema of the face extending to the neck, along with a generalized petechial eruption may occur. There may be oral ulcers and pharyngitis with tonsillar spots and raised patches of whitish exudate on the palatine arches which may coalesce into pseudomembranes.47 , 55

Other zoonotic viral infections

Filoviruses

Filoviruses are single-stranded RNA genome viruses belonging to the Filoviridae family. Marburg and Ebola are the two genotypes of this family, and Ebola is divided into 3 subtypes: Zaire, Sudan, and Reston. Both genotypes are endemic in many Central African countries and cause a severe hemorrhagic fever. The natural reservoir of these infections is unknown.47 These two viruses are transmitted to humans by direct contact with body fluids and by person-to-person contact.46 Marburg and Ebola infections have a short incubation period of about 3 to 7 days followed by high fever, headache, fatigue, myalgia, and erythematous transient eruptions. Gastrointestinal symptoms, including abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea in addition to pharyngeal and conjunctival erythema, may subsequently occur along with a typical, nonpruritic, maculopapular dermatitis that evolves with scaling over a 5-day period. There may be emorrhagic manifestations of the gastrointestinal tract, oropharynx, and lung. Sometimes, these may lead to death. .46 , 47 In addition, the Marburg virus can cause skin and mucosal ecchymoses and disseminated non-palpable petechiae. The Ebola virus may be associated with massive gingival bleeding and oral-pharyngeal fissured lesions. The differential diagnosis is very difficult and includes malaria and typhoid fever, along with other viral hemorrhagic fevers that are also associated with lethargy, wasting, prostration, and diarrhea tbut are usually more severe.47

Monkeypox virus

Monkeypox virus is the cause of monkeypox disease, identified in Africa and the United States. It belongs to the same genus of variola virus and is transmitted to humans by respiratory or direct contact with infected animals. After an incubation period of 4 to 20 days, the patient develops fever, headache, and malaise, followed by a maculopapular dermatitis that arises on the trunk and spreads peripherally to the palms, soles, and mucous membranes. A synchronous evolution from vesicles to pustules, plus umbilication and crusting in 2 to 4 weeks. may develop on the oral mucosa and in the skin, as well. Hypopigmentation or hyperpigmentation may occur.8

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

Coronaviruses are enveloped RNA viruses that are broadly distributed among humans, other mammals, and birds, causing respiratory, enteric, hepatic, and neurologic diseases. Six coronavirus species are known to cause human disease: Four of them (229E, OC43, NL63, and HKU1) are prevalent and usually cause mild to moderate upper-respiratory tract illnesses like the common cold in immunocompetent individuals; the two other strains (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus [SARS-CoV] and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus) are zoonotic in origin and have been associated with fatal epidemic diseases. Due to the high prevalence and wide distribution of coronaviruses, the genetic diversity, frequent recombination of their genomes, and increasing human-animal interactions, novel coronaviruses are likely to emerge periodically in humans owing to common cross-species infections and occasional spillover occurrence.56

SARS-CoV-2 is a novel beta-coronavirus isolated in December 2019 in Wuhan, China, from samples taken from the lower respiratory tract of infected patients.56 , 57 With droplets and close contact as the main modes of transmission, SARS-CoV-2 has quickly spread worldwide, achieving the condition of a pandemic disease. Although most patients have mild symptoms and a good prognosis after infection, others develop a severe infection and die of multiple organ complications. The disease, caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection, called coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), after an incubation period of 1 to 14 days, can affect multiple organ systems, primarily the respiratory tract but also the gastrointestinal tract, the cardiovascular system, and the skin.57 The prevalence of cutaneous findings in patients who have tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 range from 0.2%58 to 20.4%.59 Several recent cohort studies reported that the cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19 are widely diversified for morphology, distribution, spreading on the body surface, and associated findings. Skin manifestations are mainly maculopapular (Figure 5 ), vesicular, and urticarial.58, 59, 60 Cases of petechial eruptions and livedo reticularis are sporadic.58 , 61 The distribution may be localized, as with the acral erythema, coupled with vesicles and pustules—pseudo-chilblain or widely diffuse.58 Vesicular exanthems tend to occur before other signs of COVID-19 appear; pseudo-chilblain lesions appear later, whereas additional cutaneous lesions often occur together with other findings.58

Fig. 5.

Erythematous maculopapular asymptomatic exanthem of the trunk associated with COVID-19 infection.

Several pityriasis rosea (PR) skin eruptions associated with COVID-19 have been described58; one group observed that the number of PR patients who applied to their dermatology outpatient clinic during the pandemic (between April 1, 2020-May 15, 2020) were significantly more numerous than the PR patients admitted in the same period of the previous year.62 We have speculated that SARS-CoV-2 might have acted as a transactivator, triggering HHV-6/7 reactivation, and thereby indirectly causing the PR clinical manifestation.63 , 64 Although the pathogenetic role of HHV-6/7 in PR is well known,5, 6, 7 , 19 , 65 , 66 the HHV-6/7 viral reactivation has been investigated in only one COVID-19 patient with typical PR and enanthem, having erythematous macules with petechiae localized on the hard and soft palate.67

Through the same pathogenetic mechanism, SARS-CoV-2 might have induced reactivation of EBV in a recently described case of diffuse papulosquamous eruption in a man with COVID-19.68 This might have triggered the reactivation from latency of VZV, explaining the higher number of cases of herpes zoster observed by Spanish dermatologists in SARS-CoV-2 patients.58

To date, lesions involving the oropharyngeal mucosa during COVID-19 have been reported only in a few patients,69, 70, 71, 72, 73 including one case described by us.73 Painful oropharyngeal lesions were reported mainly in the form of ulcers (five cases),69 , 70 , 72 blisters and gingivitis (one case),69 and palatal petechiae, erythema, and pustules (two cases).71 Histologic analysis, conducted in three of these patients, showed inflammatory infiltrates and focal necrotic hemorrhages in the lamina propria and, in one case, small vessel obliteration with thrombi. In these patients, infections with HSV-1 and HSV-2 were excluded through in situ hybridization and polymerase chain reaction on the lesion tissue.70 , 72

A more recent case series, comprised of21 Spanish patients who developed exanthem during COVID-19, found that 29% also had oral-pharyngeal lesions. In none of these cases did the authors report associated pain. Such enanthems, always located on the palate, had a maculo-petechial pattern, were usually associated with purpuric or erythema multiforme (EM)-like cutaneous lesions, and occurred on average 12 days after the onset of COVID-19 symptoms.74

Notably, the COVID-19 patient we described was younger (19 years old), and her oral lesions, including erosions and ulcerations, blood crusts on the inner lip mucosae, and palatal-gingival petechiae, were painless, heterogeneous in morphology, and associated with severe thrombocytopenia, probably decisive in determining the onset of her cutaneous and mucosal petechiae.73 Conversely, the oral erosions described during COVID-19 might have been mainly caused by a direct viral vascular and mucosal damage. SARS-CoV-2 uses the host protein angiotensin-converting enzyme-2, largely expressed in vessels and nasal and oral mucosa to gain intracellular entry.75

In conclusion, the presence of a macular/petechial enanthem during COVID-19 is consistent with a previous study of ours. In a large series of patients with atypical exanthems, an infectious etiology, most frequently viral, was found in 88% of patients with enanthems; the petechial pattern, moreover, was strongly associated with a viral infection.5

The main features of infectious enanthems with viral etiology have been summarized in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Viral enanthems: summary of their infectious causes, mode of transmission, incubation period, diseases, and associated exanthems and enanthem patterns

| Viral infectious agent | Transmission | Incubation period (d) | Disease | Exanthem morphology | Enanthem morphology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSV-1/2 | saliva, genital secretions, direct contact with muco-cutaneous lesions | 1-26 | herpes labialis/genitalis | painful grouped vesicular lesions in orolabial/genital areas evolving to erosions and crusts | |

| VZV | direct contact or airborne droplets | 10-23 | Varicella | MP, EV | EV |

| VZV | direct contact or airborne droplets | 10-23 | shingles | MP, EV with unilateral distribution | |

| CMV | oral/vaginal secretions, urine, semen, placenta, breast milk, blood transfusions, organ transplantations | 20-60 | infectious mononucleosis, atypical exanthem, GCS | MP, U in immunocompetent; P, PE, VB, PU in immunosuppressed | MPP |

| EBV | saliva | 30-60 | Mononucleosis, atypical exanthems, GCS, APEC | MP, U, PE | MP |

| HHV-6/7 | saliva | 5-15 | Pityriasis rosea, atypical exanthems, DRESS, GCS, APEC | M, MP, MPP | M, MP, MPP |

| HHV-8 | saliva | unknown | Kaposi sarcoma, atypical exanthems | MP | MP |

| measles virus | airborne droplets | 7-21 | measles | MP, sometimes MPP, U | white lesions on a red granular appearance (Köplik spots) |

| PB19 V | airborne droplets | 4-14 | Fifth disease, atypical exanthems, GCS | M, MP | M, MP |

| Coxsackieviruses | airborne droplets | 3-10 | HFMD, atypical exanthems, AGEP, GCS | EV, MP | EV, MP |

| Echoviruses | airborne droplets | 3-10 | HFMD, atypical exanthems, AGEP | M, MP, MPP, U | EV, MP |

| Enteroviruses | airborne droplets | 3-10 | HFMD, atypical exanthems, AGEP | EV, MP | EV |

| Adenoviruses | airborne droplets | 3-10 | Atypical exanthems, AGEP, GCS, APEC | MP, EV, PE | PE, MPP |

| HIV | blood, vaginal secretions, semen | 28-56 | seroconversion illness with atypical exanthem | MP | M, MP |

| Arboviruses | arthropod vectors | 1-8 | hemorrhagic fever with atypical exanthems | MP, MPP | MP, MPP |

| Arenaviruses | rodent vectors | 7-10 | hemorrhagic fevers with atypical exanthems | PE | PE |

| Filoviruses (Marburg and Ebola viruses) | direct contact with body fluids and person-person spread | 3-7 | hemorrhagic fever with atypical exanthems | MP, PE | PE |

| SARS-CoV-2 | airborne droplets | 1-14 | COVID-19 with atypical exanthems | MP, EV, U, MPP, PE | PE, PU, erosions, ulcerations, blood crusts |

AGEP, acute generalized exanthematous pustolosis; APEC, acute periflexural exanthem of childhood; CMV, cytomegalovirus; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; DRESS, drug eruption with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; EV, erythemato-vesicular; GCS, gloves and socks syndrome; HFMD, hand-foot-and-mouth disease; HHV, human herpesvirus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HSV, herpes simplex virus; M, macular; MP, maculopapular; MPP, maculopapular with petechiae; PB19 V, parvovirus B19; PE, petechial; PU, pustular; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; U, urticarial; VB, vesico-bullae; VZV, varicella-zoster virus.

Enanthems associated with bacterial infections

Chlamydia pneumoniae

C pneumoniae, an obligate intracellular gram-negative bacterium, may be one of the possible causative agents of pneumonia, bronchitis, pharyngitis, sinusitis, and endocarditis. C pneumoniae and C psittaci have been reported to cause dermatologic manifestations, such as erythema nodosum, whereas C trachomatis is a well-known etiologic agent for eye and urogenital infections76; mucositis without an eruption has been reported77 in the setting of C pneumoniae respiratory infection, although rarely. Cheilitis with erosions and hemorrhagic crusts on the upper and lower lips and vesico-bullous lesions and erosions on the oral mucosa and on the anterior part of the tongue have been described. Conjunctivitis and urogenital erosions may also be associated.77 The differential diagnosis should include a primary herpetic infection, EM, and Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS).

Mycoplasma pneumoniae

M pneumoniae infection can be associated with mucocutaneous eruptions especially involving children and young patients (2-20 years old). Cutaneous lesions are polymorphic, mostly nonpruritic maculopapular, papulo-vesico-bullous, and petechial with a targetoid pattern. The lesions are mainly located on the extremities (46%) and trunk (25%). Mucosal involvement is usually present. When the eruption is conspicuous, the term “M pneumonia–induced rash and mucositis (MIRM)” has been proposed. Ocular involvement, stomatitis, and vulvitis are described at various levels of severity.78 , 79 Oral involvement (94%) may be more or less severe and is characterized by vesicular lesions and bullae on the lips and buccal mucosa. Prominent hemorrhagic crusting on the lips, eyes, and nasal mucosa may be present, with blisters possibly being present on the hard and soft palate. The painful lesions of the oral mucosa that may extend to the esophagus make eating difficult and delay healing.80 , 81 Mild inflammation of the bilateral bulbar conjunctiva could also be seen.82 Urogenital and anal lesions are common (63%), including vesiculobullous lesions, erosions and ulcers of the glans, urethral meatus, vagina, and vulva. There may be chronic ocular sequelae with cicatrizing conjunctivitis and corneal ulcerations,83 , 84 plus oral or genital synechiae.85 The different mucocutaneous eruptions associated with M pneumonia infection should be differentiated from herpes-related EM, SJS, and toxic epidermolysis necrosis.78 These entities are often overlapping with features that distinguish MIRM from herpes-related EM or drug-induced SJS/toxic epidermolysis necrosis including the age of the patients (young in MIRM and EM), predominance of mucosal involvement (rare in EM), sparse cutaneous involvement (mainly in MIRM), a better prognosis (in MIRM), and histopathology (parakeratosis, dense dermal infiltrate, red blood cell extravasation, and eosinophils or neutrophils in SJS). In addition, SJS is usually related to drugs, whereas EM major is most commonly secondary to HSV infections and usually has less mucosal involvement. MIRM can have more severe prodromal symptoms and mucosal and internal organ complications, whereas cutaneous involvement is sparse or absent.

Francisella tularensis

After inoculation into the skin, usually after the bite or contact with feces of a tick or other arthropods, such as mosquitoes and horseflies, this gram-negative bacterium multiplies locally, and after 2 to 5 days it causes an erythematous itchy papule that rapidly enlarges, forming an ulcer with raised margins. Regional lymphadenopathy may occur, becoming fluctuant and even discharging. Systemic diffusion of F tularensis through blood (tularemia) produces in affected organs and areas of necrosis with granuloma formation. The diagnosis of tularemia is generally based on findings and patient history, imaging, and laboratory investigations. Different clinical patterns of tularemia, such as oropharyngeal ulceroglandular, which is the most common form, oculoglandular, typhoidal, and pulmonary type have been described. Skin signs may develop after the infection in all tularemia types, probably in response to the systemic bacterial spreading.86 , 87 The cutaneous findings may be divided into those of primary lesions, which are ulcerations at the portal entry, and secondary lesions.88 The latter may be faint macular lesions or more evident maculopapular, vesicular, or pustular eruptions, erythema nodosum, and vasculitic or phototoxic eruptions.89 , 90 The conjunctiva and oropharynx are the most commonly involved mucous membranes. Exudative or nonexudative pharyngitis91 and a sore throat are common findings in 25% of patients with oral tularemia. Sometimes, it might be diagnosed as tonsil-pharyngitis. The differential diagnosis is, therefore, very important in the oropharyngeal type. The conjunctivitis seen in ulceroglandular tularemia may be severe.

Salmonella typhi

Salmonella are gram-negative bacilli capable of causing a large variety of infections including typhoid fever, septicemias, and gastroenteritis of varying severity. During the first week of typhoid fever, caused by S typhi, there may be a high fever and chills, headache, and abdominal tenderness, along with small pink blanching, slightly raised macules, and the characteristic rose spots on the chest and abdomen in 63% of patients. They appear in crops and are uncommon during infection due to other types of Salmonella. Erythematous generalized exanthem or petechial and urticarial lesions may occur in early stages of typhoid fever. The “typhoid tongue” is characterized by a furry, patinated, and grayish-colored center, and by reddened, dry, and deepithelialized edges and apex. It is considered to be one of the four specific clinical markers for typhoid fever, in addition to a high fever, loose bowel movements, and bradycardia, with a reported specificity of 94%.92

Haemophilus influenzae

H influenzae is a gram-negative coccobacillus found in the upper respiratory tract. It is the most common cause of bacteremia between the ages of 2 months and 2 years, primarily causing meningitis, pneumonia, epiglottitis, and cellulitis. Purpuric lesions and petechiae resembling those of Neisseria meningitides may occur with bacteremia. Conjunctivitis may accompany the infection, along with facial cellulitis, erythematous buccal mucosal lesions, and nonexudative pharyngitis5 associated with a sore throat.6 , 7

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

P aeruginosa is a motile gram-negative bacillus associated with severe infections in immunocompromised subjects, in patients receiving prolonged antibiotic treatment, and in hospitalized patients. It may be an inhabitant of the intestine, colonize the skin of healthy subjects, particularly the axillary and anogenital regions, be present as a secondary contaminant in wounds, or occasionally infect the ear, lung, skin, or urinary tract in patients with diminished host resistance. Severe infection is usually associated with damage to the affected tissues. Usually, the infections remain localized on the skin or subcutaneous tissues. Hematogenous dissemination is characterized by necrotic hemorrhagic nodules in many organs. Pseudomonas overgrowth in heated pools, whirlpools, and hot tubs results in the so-called “hot tub folliculitis,” an eruption of disseminated erythematous, pruritic scattered, or grouped papulopustular lesions affecting the immersed skin. Lesions heal with crusting and/or desquamation.

P folliculitis may infrequently be acquired from sponges, wet suits, and epilation. These eruptions usually resolve spontaneously. In immunocompromised individuals, P folliculitis can instead evolve into bullae surrounded by erythema that become necrotic (ecthyma gangrenosum-like lesions). Pseudomonas may cause an acute enteric infection associated with fever, diarrhea, and macular lesions on the trunk, resembling the “rose spots” of typhoid fever. In P septicemia, various skin eruptions may be seen, consisting of maculopapules, pustules, vesicles, bullae, necrotic and hemorrhagic nodules, petechiae, and ecchymoses. The mucous membranes may present with erythematous maculopapular lesions and petechiae. EM-like lesions may be seen on the skin and mucous membranes.5, 6, 7

Listeria monocytogenes

L monocytogenes is a gram-positive motile bacterium that can survive intracellularly. It is acquired from contaminated food, especially unpasteurized milk and cheese, or drink; soil; or inhalation. It can be isolated from about 5% of human feces. In immunocompetent adults, Listeria infection may cause a nonspecific syndrome with fever, headache, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, but in immunocompromised patients, it may cause meningitis, endocarditis, pneumonia, and osteoarticular involvement. Pregnant woman, often asymptomatic, may infect her offspring either transplancentally or during delivery.

Neonatal listeriosis may be divided in early and late onset infection. Transplacental infection causes disseminated fetal listeriosis, resulting in stillborn or fatal listeriosis. If the disease is delayed to a few weeks postpartum, the newborn usually shows a septic clinical picture with cardiorespiratory distress and gastrointestinal or neurologic involvement; hepatosplenomegaly may also be present. Dark red papular, pustular, and petechial skin lesions, localized to the trunk and legs, or a generalized maculopapular exanthem, are indicative of disseminated neonatal infection. Erythematous macular lesions with scattered petechiae may be seen on the oral mucous membranes.93 Neonatal late-onset and adult meningitis and septicemia usually lack skin or mucous membrane involvement. Direct inoculation of Listeria in butchers or veterinarians may cause self-limited, nonpainful, nonpruritic, papulopustular or papulovesicular eruptions resolving without antibiotic treatment.5, 6, 7

Acinetobacter species

Acinetobacter organisms are ubiquitous, opportunistic, pleomorphic aerobic gram-negative bacilli commonly isolated in normal subjects and hospitalized patients. They may cause infection in immunocompromised patients. Most of infections caused by this species are due to A baumanii and may involve any organ, including skin and soft tissues; disseminated infection may result in abscesses. There may be a pink to red maculopapular eruption with petechiae involving the trunk, extremities, palms, and soles found in patients with prosthetic valve endocarditis.94 There may also be conjunctival hyperemia and petechial lesions on the buccal mucosae.

Fusobacterium necrophorum

F necrophorum is a gram-negative bacillus found in the mouth which can cause persistent or recurrent tonsillitis that may lead to septic thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein, known as Lemierre syndrome, and septic emboli in the lungs and other sites. There may be a nonpruritic painful maculopapular eruption on the extremities, including the palms and soles, which has been described during a severe septic fusobacterium infection.95

Treponema pallidum

Secondary syphilis is characterized by an evanescent macular eruption occurring within 2 to 10 weeks after the primary chancre and, usually, 3 to 4 months after inoculation of the gram-negative spirochete T pallidum. Then skin eruption develops in 80% to 95% of untreated patients. Macular (roseola syphilitica), maculopapular, papular, or annular lesions are the most common ones. These manifestations usually have a symmetric pattern and primarily involve the trunk and extremities (Figure 6 A). Palmoplantar manifestations may be macular or papular, discrete or diffuse, slightly scaling, or frankly hyperkeratotic. In addition, oral papular lesions and mucosal erosions may be present concurrently.96, 97, 98 The latter lesions are especially located on the lips, gums, hard and soft palate, uvula, tonsils, and posterior pharynx, and may occur with a linear pattern, known as the “snail track.” Initially, they appear as slightly raised, rounded areas, covered by a thin membrane of pink to grayish color. When the surface is removed, there will be an erosion similar to a diphtheroid membrane in the throat. Lesions on the ventral side of the tongue and in the mouth appear as nonerosive, painless plaques or smooth patches, which may achieve a large size and last only a few days (Figure 6B). Such lesions may be confused with lichen planus, aphthae, pemphigus, EM, herpes simplex ulcers, and tuberculous erosions. With or without therapy, all secondary syphilitic lesions resolve without scar formation within 2 to 10 weeks.96, 97, 98

Fig. 6.

Secondary syphilis. A, Roseola syphilitica: Slightly scaling rose-colored macular lesions on the trunk. B, Mucous plaques of the ventral side of the tongue, some covered by a thin membrane of grayish color.

N meningitidis

N meningitidis is a gram-negative bacterium associated with damage to the small dermal blood vessels and is responsible for several skin lesions. Typically, meningococcal septicemia begins with an acute onset of fever, chills, and generalized aches involving the back or thighs. An exanthem localized to the trunk and extremities is characterized by petechiae in the groin and axillae, flexor surfaces, trunk, and ankles, as well as the palms, soles, and face. The skin lesions may appear approximately 24 hours after the onset of the general symptoms. The petechiae are often raised with a vesicular center. This eruption becomes apparent only in 26% of patients, evolving over time. Maculopapular lesions with a petechial component are usually present on the oral mucous membranes (Figure 7 ) and conjunctiva. In patients with severe meningococcemia, complicated by disseminated intravascular coagulation, areas of cutaneous infarction can appear on the extremities. Bacterial meningitis can be diagnosed when at least two of the four following findings are present: Fever, headache, neck stiffness, and mental status changes.5, 6, 7

Fig. 7.

Enanthem during meningococcal septicemia. Erythematous macules on the hard and soft palate, papules, and petechie on the soft palate.

N gonorrhoeae

N gonorrhoeae is a gram-negative diplococcus which causes gonorrhea and may induce systemic manifestations such as arthritis, dermatitis, endocarditis, hepatitis, meningitis, and myopericarditis. Disseminated gonococcal infection usually appears with systemic involvement or purulent arthritis affecting one or more joints. The onset of gonococcemia is characterized by fever, chills, arthralgias, and papular, pustular, petechial, hemorrhagic, or necrotic slightly tender skin eruptions usually localized on the extremities. Gonococcal infection may also produce pharyngitis with exudative tonsillitis and conjunctivitis.5, 6, 7

Rickettsiae

Rickettsiae are obligate, intracellular, pleomorphic, gram-negative bacteria that cause infection through the bite or feces of the infected arthropod vectors. Scratching a flea bite may favor inoculation of Rickettsiae from the feces of the flea. Inhalation of dried infected dusts is another route of infection in Q fever and epidemic typhus. Rickettsiae have a prominent tropism for endothelial cells of small vessels and cause diseases that vary from mild to fulminating life-threatening infections. The classic triad consisting of fever, headache, and exanthem is common at presentation, and skin involvement is a crucial clue occurring in almost 100% of rickettsioses.99 A local skin lesion shows the primary site of entry of bacteria only in some diseases caused by Rickettsiae, namely scrub typhus, rickettsialpox, and Mediterranean spotted fever.

Rocky mountain spotted fever

Rocky mountain spotted fever (RMSF), widespread in North and South America, caused by R rickettsii, is transmitted to humans by tick bites. After the incubation period of 5 to 10 days, the disease has a sudden onset with severe frontal headaches and myalgia, primarily in the back and legs muscles, and high fever. The eruption is the most helpful diagnostic sign and appears a few days after the onset of illness with erythematous macular lesions starting on the wrists, ankles, palms, soles, and forearms, and then (after 12-18 hours) it spreads centripetally to the trunk, neck, and face (Figure 8 ). The high temperatures accentuate the exanthem, which after 2 to 3 days becomes maculopapular with petechiae and gives a dusky red appearance. Petechiae can appear on the extremities when using the sphygmomanometer Rumpel-Leede sign. Hemorrhagic lesions may develop especially over bony prominence forming ulcers.

Fig. 8.

Maculopapular exanthem during Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Reproduced with permission from CDC Public Health Image Library.

The eruption resolves with postinflammatory hyperpigmentation or scars over areas of focal necrosis. Up to 10% of patients have no skin eruption—Rocky mountain “spotless” fever. The eyes frequently appear injected, and petechiae may occur in the conjunctivas or in the retina. The patient recovers within 2 to 3 weeks, but in untreated cases and in the elderly, the fatality rate is high (20%-50%). Differentiation from other acute infections and their cutaneous eruptions is difficult. The history of a tick bite may be helpful.

The eruption of meningococcemia may resemble RMSF, because it is macular, papular, or petechial in the chronic form, and petechial, purpuric, or ecchymotic in the fulminant type; the meningococcal eruption, however, occurs faster in the fulminant type. The exanthem of measles breaks out first on the forehead, spreading downward over the face, neck, and trunk; it is rapidly confluent and preceded by Köplik spots. The typhus fever eruption begins in the axillary folds of the trunk and then spreads centrifugally, rarely involving the face, palms, and soles. In murine typhus, the eruption is less extensive than RMSF, non-purpuric, and non-confluent. Rickettsialpox is characterized by early vesiculation of the maculopapular eruption and by a negative Weil-Felix reaction.99

Epidemic typhus

Epidemic typhus is caused by R prowazekii and is transmitted worldwide by body lice and by the flying squirrel in the United States. Pediculus humanus corporis is the only important vector of epidemic typhus. Epidemic typhus resembles murine typhus, but it is more severe. The incubation period lasts about 7 days, and the exanthem appears 5 days after the onset of the systemic manifestations of fever, chills, myalgias, agitation, and stupor. The eruption has a centrifugal distribution, starting in the axillary folds and then involving the trunk and extremities, but sparing the face, palms, and soles. The early eruptions consist of pink, macular lesions, initially fading under pressure. Later, they become fixed and confluent maculopapular with sparse petechiae. The disease is fatal in about 30% of patients. Brill-Zinsser disease is a recrudescent form of epidemic typhus due to reactivation of R prowazekii, probably persisting in adipose tissue.99

Murine typhus

Murine typhus is caused by R typhi and R felis, transmitted to humans by fleas. It is clinically similar to epidemic typhus, causing fever, chills, headache, and myalgia. This disease is endemic in temperate climates and especially on the coastal areas of the United States, Asia, Australia, Mexico, and Spain.100 The eruption and other manifestations are similar to those of epidemic typhus, but they are much less severe. The early eruption is sparse and discrete, consisting of erythematous, asymptomatic maculopapules on the abdomen, which spreads to the trunk and extremities, but often spares the face, palms, and soles.

Scrub typhus

Scrub typhus is caused by R tsutsugamushi, after the bite of infected mites. After 10 to 15 days, the illness begins abruptly with headache, fever, chills, and lymphadenopathy, being more prominent in the nodes draining the area of the bite. The initial lesion is an erythematous papule at the onset of fever which can undergo ulceration forming an eschar. A centrifugal maculopapular eruption primarily involving the trunk and then spreading to the extremities develops but fades within a few days. Conjunctival injection is common.99

Mediterranean spotted fever

Mediterranean spotted fever, the most frequent rickettiosis in Europe, is caused by R conorii, usually transmitted by the brown dog tick. Sometimes, conjunctivitis may represent the eye inoculation site occurring after manipulation of crushed infected ticks. After an incubation period of 5 to 7 days, the onset of high fever is accompanied by headache, myalgia, and arthralgias. Conjunctival injection and photophobia are common. The classic cutaneous hallmark is the tache noire, an erythematous indurated papule with a central necrotic ulcer and eschar that represents the site of the tick bite. Regional lymph nodes become enlarged. Soon after, a purple red maculopapular exanthem with a purpuric component develops on the forearms, spreads to the trunk, and also involves the face, palms, and soles. A vesicopustular exanthem has also been described. The eruption heals slowly with brown-red hyperpigmentation.5, 6, 7 , 99

Rickettsialpox

Rickettsialpox is caused by R akari transmitted by the bite of house mouse mites. The classic triad of the disease includes fever, a papulovesicular eruption, and an inoculation eschar. The primary papulovesicular lesion at the site of inoculation occurs about 24 to 48 hours after the bite and progresses to a crusted ulcerated papule or eschar with a red halo and associated regional lymphadenopathy. Constitutional symptoms, including fever, headache, chills, and myalgia, may appear after a few days and are followed 2 to 3 days later by a papulovesicular exanthem involving the face, trunk, and extremities. A vesicular enanthem on the palate, tongue, mouth, tonsils, or pharynx lasting less than 48 hours may occur.101 The mucosal lesions are similar to the cutaneous ones but are more transient. Conjunctival injection may occur.99

Staphylococcus aureus

Staphylococci are gram-positive bacteria which are divided into two major groups: the coagulase-negative and coagulase-positive staphylococci. Among the coagulase-negative species, S epidermidis is the most common member and is part of the normal flora of the skin and mucous membranes. S epidermidis is an uncommon pathogen, but it can cause superficial and invasive infections, the latter usually hospital-acquired or in patients harboring medical devices.

S aureus is a persistent member of the microbial flora in 10% to 20% of the population. The carriage is transient or intermittent in other individuals. It transiently colonizes the anterior nares in 70% to 90% of persons and persistently in 20% to 30% of them. Perineal area colonization occurs in 5% to 20% of persons, and vaginal carriage has been established in 10% of women. S aureus is an aggressive pathogen and the most common cause of pyodermas and soft tissue infections. From the skin, it can invade the bloodstream causing bacteremia and then endocarditis, osteomyelitis, and other remote localizations. In acute S aureus endocarditis and bacteremia, skin and mucous membrane lesions occur in most of the patients and provide a clue for the diagnosis. Petechial eruptions occurring in crops involve mainly the extremities, including the palms and soles, oral mucous membranes, and conjunctivae. Splinter hemorrhages, which are subungual, linear, dark-red streaks; Osler nodes, which are erythematous, painful nodules over the arms, palms, legs, and soles and on the pad of the fingers and toes which persist for hours to days; and Janeway lesions, which are erythematous maculopapular-petechial lesions on the palms and soles, are common in endocarditis and bacteremia due to Staphylococci, Streptococci, Enterococci, and Gonococci.102 These eruptions may also be seen during disseminated intravascular coagulation. Roth spots, defined as white centered retinal hemorrhages, are common during bacterial endocarditis. In focal infections localized to the skin or during osteomyelitis, pneumonia, and urinary tract infections, macular and maculopapular eruptions may occur.5 , 6

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome

Staphylococcal scaled skin syndrome (SSSS) is a generalized exfoliative dermatitis due to infection by the toxin (exfoliatin)-producing strains of Sta aureus, usually belonging to phage group II. The disease typically affects newborns and children under the age of 5. It is rare in adults, mostly occurring in immunosuppressed subjects or with renal insufficiency. S aureus can usually be recovered from the nasopharynx and skin. The disease starts with a localized skin infection associated with modest systemic findings. Soon, a faint erythematous exanthem develops in the perioral area spreading to the trunk and extremities.103 Flexural accentuation may be seen. The disease may simply consist of a scarlatiniform exanthem sometimes progressing within 24 to 48 hours to a blistering generalized eruption, particularly localized to flexural areas. Mucous membranes are usually spared, except for conjunctival involvement. The lip may become crusted and develop fissures.104 SSSS usually resolves within 1 week, leaving generalized desquamation as large sheets.

Toxic shock syndrome

Toxic shock syndrome (TSS) is a multisystemic illness due to exotoxin-producing strains of S aureus. Originally most associated with tampon use, TSS is now recognized as occurring in menstrual and non-menstrual forms. The latter follows surgery, typically the second day after surgery, trauma, or burns. TSS has been related to toxin-producing strains of S aureus, especially TSS toxin-, but also enterotoxin B and C. Clinically, it is characterized by high fever; hypotension or shock; multiorgan involvement with gastrointestinal dysfunction, renal or hepatic insufficiency, thrombocytopenia, myalgias, and mental alterations; and a generalized “sunburn” punctate erythematous eruption that subsequently desquamates. The eruption may be indistinguishable from that of scarlet fever. Erythema and non-pitting edema of the face, arms, and legs are common. Redness may also be present on the oral mucosa, having a strawberry appearance on the tongue (Figure 9 ), vagina, and tympanic membranes, as well as the bulbar and palpebral conjunctivae.5, 6, 7 Petechiae and ulcers may be seen on the oral mucosa, vagina, esophagus, and bladder. After the onset of the illness, within 1 to 2 weeks, there may be large sheets of desquamation from the palms and soles.

Fig. 9.

Tongue with a strawberry appearance in a case of TSS caused by Staphylococcus aureus. Reproduced with permission from CDC Public Health Image Library. TSS, toxic shock syndrome.

Streptococcal TSS (STSS) presents the same cutaneous and mucous hallmarks of staphylococcal TSS, except for the prevalence of a skin gateway of entry via soft tissue infections in STSS. Bacteremia is more common and mortality is higher in STSS than in staphylococcal TSS (50% versus 10%, respectively).104

Recalcitrant, erythematous, desquamating disorder

Recalcitrant, erythematous, desquamating disorder is a toxin-mediated illness (toxin produced by S aureus) that has been reported only in patients with AIDS. Clinically, recalcitrant, erythematous, desquamating disorder is very similar to TSS and is characterized by fever, hypotension, diffuse macular erythema, ocular and oral mucosal enanthem, and a strawberry tongue.104

Staphylococcal scarlatiniform eruption

This febrile eruption resembles a generalized scarlatiniform eruption with tenderness in the initial stage of SSSS. The punctate erythema creates a sandpaper roughness, similar to that found in streptococcal scarlet fever. In the body folds, such as the ventral aspects of the elbows, the superficial capillaries break down causing red streaks; hence, Pastia lines. These may persist for 1 to 2 days after the generalized eruption has gone. Petechial enanthem on the oral mucous membranes (especially soft palate) is common. The exanthem resolves with desquamation within 10 days.104

Streptococcus pyogenes

Scarlet fever

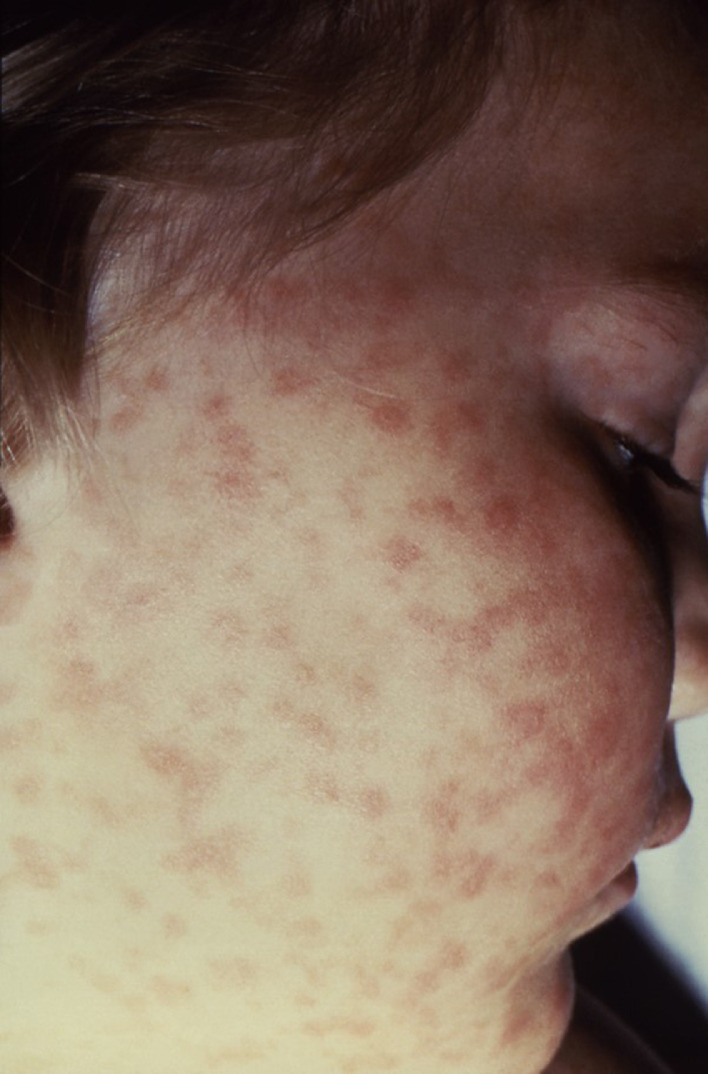

Scarlet fever primarily occurs in childhood and has been related to a delayed-type of hypersensitivity to exotoxins A, B, and C of Strs pyogenes. The disease begins with high fever, chills, sore throat, headache, nausea, vomiting, and lymphadenopathy. The exanthem appears after 24 to 48 hours and involves first the neck, face, chest, and back and later the hands and feet, but it spares the palms and soles. It is characterized by petechial streaks in flexural locations (Pastia lines) and a generalized erythema with punctate elevations that impart a “sandpaper” texture to the skin. A facial flush contrasts with a prominent circumoral pallor. In addition, an erythema with petechiae and erythematous macules may involve the palate (Figure 10 ), as well as the pharyngo-tonsillar area. The tonsils, the hard and soft palate, and the uvula are edematous and dusky red. Patches of exudate fill the tonsillar crypts. Early in the disease, the tongue is covered by a white coat through which hypertrophied papillae protrude as red islands (“white strawberry tongue”). After a few days, the scaling coating is gone, leaving the typical “red strawberry tongue.”5, 6, 7 The eruption usually lasts 4 to 5 days and is followed by prominent desquamation that is a striking feature of the convalescent phase. The skin on the hands and feet shows large sheet desquamation.

Fig. 10.

Diffuse erythema with petechiae involving the soft palate during scarlet fever.

Toxin-mediated erythema (recurrent toxin-mediated perineal erythema)

Recurrent toxin-mediated perineal erythema is mediated by toxins due to S aureus or Str pyogenes. Recurrent toxin-mediated perineal erythema typically begins with a bacterial pharyngitis followed by diffuse macular erythema involving the perineum. Oral mucosal changes include erythema, edema, and a strawberry tongue. Erythema and edema affect the extremities, and there may be desquamation of the hands and feet during resolution.104

Erythema scalariform desquamative recidivans