Abstract

As one of the most vulnerable sectors exposed to the COVID-19 pandemic, transport sectors have been severely affected. However, the shocks and impact mechanisms of infectious diseases on transport sectors are not fully understood. This paper employs a multi-sectoral computable general equilibrium model of China, CHINAGEM, with highly disaggregated transport sectors to examine the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on China's transport sectors and reveal the impact mechanisms of the pandemic shocks with the decomposition analysis approach. This study suggests that, first, multiple shocks of the COVID-19 pandemic to transport sectors are specified, including the supply-side shocks that raised the protective cost and reduced the production efficiency of transport sectors, and the demand-side shocks that reduced the demand of households and production sectors for transportation. Second, the outputs of all transport sectors in China have been severely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, and passenger transport sectors have larger output decreases than freight transport sectors. While the outputs of freight transport sectors are expected to decline by 1.03–2.85%, the outputs of passenger transport sectors would decline by 3.08–11.44%. Third, with the decomposition analysis, the impacts of various exogenous shocks are quite different, while the changes in the output of different transport sectors are dominated by different exogenous shocks. Lastly, while the supply-side shocks of the pandemic would drive output decline in railway, waterway, and aviation transport sectors, the demand-side shocks would drive so in the road, pipeline, and other transport sectors. Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic has negative impacts on the output of most non-transport sectors and the macro-economy in China. Three policy implications are recommended to mitigate the damages caused by the COVID-19 pandemic to the transport sectors.

Keywords: COVID-19 pandemic, Transport sectors, CGE model, Decomposition analysis, China

1. Introduction

Since the first novel coronavirus infection was found in Wuhan in mid-December 2019, the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has been rapidly spreading across China and worldwide. By end June 2020, more than 80,000 cases were confirmed with over 3000 fatalities (NHC, 2020). Chinese government recognized the COVID-19 pandemic as the most serious public health emergency with the fastest transmission speed, the most extensive infection area, and the most difficult control and prevention since the founding of P.R. China. In the same period, the confirmed cases exceeded 10.0 million worldwide, causing around 500,000 deaths (Johns Hopkins University, 2020). COVID-19's infectivity and transmission speed surpass those of the previous infectious diseases, such as SARS, H1N1, and MERS, causing unprecedented economic damages to the economies of China and the rest of the world (Liu et al., 2020; Petrosillo et al., 2020). As a result, China's GDP fell sharply by 6.8% in the first quarter (Q1) of 2020, compared to the positive GDP growth rate of 6.4% in Q1 2019. The IMF also has lowered China's GDP growth projection from 6% to 1.0% for the whole of 2020 (IMF, 2020).

Numerous studies have assessed the economic impacts of infectious diseases (Blake et al., 2003; Chou et al., 2004; Jonung and Roeger, 2006; Smith et al., 2011; Evans et al., 2014; Kumar et al., 2015). Several studies have suggested that the COVID-19 pandemic would cause great damages to China's macro economy and sectoral output in the short run. While the shutdown of economic activities would significantly cut down the enterprises' production, strict distancing would cause consumers to spend less (Duan et al., 2020; Guan et al., 2020; Guerrieri et al., 2020; McKibbin and Fernando, 2020; Zhang et al., 2020). McKibbin and Fernando (2020) employed a dynamic computable general equilibrium (CGE) model and found that China's GDP in 2020 would decline by 0.4–6.2% depending on the population mortality and duration of the pandemic. Duan et al. (2020) used the input-output model and indicated that China's GDP would fall by 0.40–0.72%. Moreover, the pandemic would severely impact the output of production sectors, especially for the sectors directly exposed to it, such as tourism, hotel, restaurant, and retail (Beck and Hensher, 2020; Guan et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2020; Yetkiner and Beyzatlar, 2020).

The transport sectors are also directly exposed to the pandemic. According to the statistics by the Ministry of Transport of P.R. China (2020), the total passenger volume of railway, road, waterway, and aviation transportations dropped by 50.9% in January and February of 2020, while the total freight volume fell by 19.7%. An increasing number of studies evaluated the relationship between the pandemic and transport sector, and regarded it as the major transmission route of infectious diseases (Regondi et al., 2013; Cai et al., 2019; Gaskin et al., 2020; Jiao et al., 2020; Lau et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020; Przemysław et al., 2020). Zhang et al. (2020) found that frequencies of flights and high-speed train services out of Wuhan had been significantly associated with the number of COVID-19 cases in the destination cities. The farther the distance from Wuhan, the lower number of cases in a city and the slower the dissemination of the pandemic. Lau et al. (2020) also indicated a strong linear correlation between domestic COVID-19 cases and passenger volume for regions within China and a significant correlation between international COVID-19 cases and passenger volume.

Although several studies have examined the impacts of the pandemic on transport sectors, they greatly differ in projecting the decreases in passenger and freight traffic volume from the COVID-19 pandemic. By establishing pandemic scenarios, several studies projected that China's transport passenger revenues and volumes will significantly decline (IATA, 2020; Peng, 2020; Qi et al., 2020; Shi et al., 2020). IATA (2020) projected that China's aviation passenger revenue will decrease by USD 22.2 billion and passenger volumes will fall by 23% in 2020 under a limited spread scenario, and the revenue loss will reach USD 49.7 billion under the extensive spread scenario. In contrast, several studies argue that the transport sector, as a whole, would be not severely affected by this pandemic (Bombelli, 2020; CCXI, 2020; Dong et al., 2020; Teng et al., 2020). Furthermore, most previous studies focused on transport as a single sector or considered transportation as an aggregated sector (Hensher et al., 2020; Hu and Chen, 2020; Zhang, 2020). They seldom analyzed the heterogeneity of the impacts of the pandemic on different transport sectors. However, compared with the railway and road transportation, aviation transportation is more vulnerable to the pandemic (Nakamura and Managi, 2020; Suau-Sanchez et al., 2020). To fully understand the impact of this pandemic, the performances of different sectors ought to be examined and compared.

Furthermore, the shocks and impact mechanisms of the pandemic on transport sectors are inadequately understood. Most studies simply examined the changes in passenger and freight volume of transport sectors affected by the pandemic (Loske, 2020; Qi et al., 2020; Shi et al., 2020; Wen et al., 2020), but they failed to capture the impact mechanisms of the pandemic on transport sectors. Several studies that analyzed the impacts on the macro economy have specified the shocks of infectious diseases from the supply and demand sides (Dixon et al., 2010; Lee and McKibbin, 2004; McKibbin and Fernando, 2020; Oum and Wang, 2020). Lee and McKibbin (2004) specified three broad shocks of SARS to China's economy: an increase in the country risk premium, demand shock to the retail sector, and an increase in the cost of exposed service sectors. Their simulation results suggested that economic damages caused by SARS are mainly from the demand-side shocks. Dixon et al. (2010) analyzed the economic damages caused by H1N1, and found that the macroeconomic consequences of an epidemic are more sensitive to demand-side shocks such as reductions in international tourism and leisure activities than to supply-side shocks such as reductions in productivity. McKibbin and Fernando (2020) specified the shocks of COVID-19 pandemic, including reduction of labor supply, the rising cost of each sector, consumption reduction, rise in equity risk premium of companies, and increases in country risk premium. However, to our knowledge, the existing literature seldom specified the shocks of infectious diseases to the transport sectors and revealed the different roles of these factors in the outputs of transport sectors. To better understand the impact of the pandemic on different transport sectors, we should also quantitatively assess the shocks and impact mechanisms of the pandemic.

This paper contributes to the existing literature from three perspectives. First, we specify the different shocks of the COVID-19 pandemic on the performance of transport sectors, from both demand and supply sides. Second, the heterogeneity of the impacts of the pandemic on the transport sectors is revealed, highlighting the vulnerable sectors. Third, the impact mechanisms of the pandemic on the output of transport sectors are quantitatively examined. To achieve these goals, we specify six shocks of the pandemic from the supply and demand sides of the transport sectors. A multi-sectoral CGE model of China, CHINAGEM, with highly disaggregated transport sectors, is employed to assess the impacts of the pandemic on different transport sectors in China. The impact mechanisms of the pandemic on the output of transport sectors are evaluated with a decomposition analysis approach. This study is vital to accurately assess the impact of infectious diseases on transport sectors and inform supporting policies for transport sectors to mitigate the damages.

The remainder of this study is organized as follows. Section 2 specifies different shocks of the COVID-19 pandemic on transport sectors. Section 3 introduces the simulation model and the decomposition analysis approach. Section 4 discusses the simulation results for the impacts of the pandemic on outputs of transport sectors and non-transport sectors as well as macro-economy. The last section concludes the study with policy implications.

2. Specifying the shocks of the COVID-19 pandemic to transport sectors

Following the previous studies (Dixon et al., 2010; Lee and McKibbin, 2004; McKibbin and Fernando, 2020), different shocks of the COVID-19 pandemic to transport sectors are specified and categorized into two groups: the demand-side and supply-side shocks. The demand-side shocks include the production shutdown of manufactures and services (PSP) and the decline in total investment (DTI), household consumption (DHC), and household demand for transportation (DHT). The supply-side shocks comprise the lockdown of transport facilities (LDT) and the increase in the protective cost of transport sectors (PCT). The shocks of the pandemic are quantified based on the statistical data in China, available by end of October 2020. Assuming that the economy would return to the normal growth rate in November and December 2020, we transform the shocks of the pandemic occurred from January to October 2020 to those in the full year of 2020. The detailed calculations are as follows.

-

(1)

PSP: the production shutdown of manufactures and services would reduce their total factor productivity by 2.31% and 1.16%, respectively. The nationwide extension of spring festival vacation would cause the shutdown of the enterprises' production in manufacture and service sectors, indicating the reduction in total factor productivity (TFP). Following Dixon et al. (2010) and Verikos et al. (2011), the loss of workdays is calculated as the negative shock to TFP. According to the schedule of resuming work, this loss in different provinces reached 3–16 days. Weighed by the proportion of provincial GDP to national GDP in 2019, this loss is averaged to be 6.9 days for China as a whole, accounting for 2.75% of the yearly workdays (2.75% = 6.9/251). The time-uneven pattern of economic activity considers that the Q1 2019 accounted for 21%, rather than 25%, of the GDP in 2019. The proportion of yearly workday loss is adjusted to be 2.31% (=2.75%*21%/25%), which is used as the decrease in the TFP of manufacturing sectors. Moreover, as the production of service sectors might rebound in the next few months of this year, driven by the rebounding of household demand, the TFP loss of service sectors is assumed to be a half of that of manufacturing sectors (1.16% = 2.31*50%). Finally, we assume that sectors related to people's livelihoods (e.g., agriculture, mining, electricity supply, water supply, gas supply, health care, and social welfare) are immune from PSP.

-

(2)

DTI: the total investment would decline due to the 1.97% increase in the risk premium of investment. The pandemic causes great risk to investment, which would significantly raise the costs of investment. As a higher risk premium of investment is required, following McKibbin and Fernando (2020), we assume that the pandemic will raise the risk premium of investment in China by 1.97%.

-

(3)

DHC: households' total consumption expenditure would decline by 5.56%. During the pandemic quarter, households would significantly cut down their consumption expenditure, especially on accommodation and food services, textiles, clothes, and transport equipment. Assuming that households' total consumption expenditure would return to normal in November and December, the households' total consumption expenditure from January to the end of October 2020 would fall by 6.83% (National Bureau of Statistics, 2020), which is annualized to be the percentage decrease of the yearly consumption expenditure using the proportion of total consumption from January to October 2019 to the whole year (81.33%). The yearly total consumption expenditure would decrease by 5.56% (=6.83%*81.33%). Similarly, we obtain the shocks to the consumption of accommodation and food services (−15.70%), food, tobaccos, and drinks (2.83%), textiles and clothes (−9.49%), chemical product (6.22%), metal products (5.29%), electrical machinery and apparatus (−7.43%), papermaking, printing, and culture product (3.14%), timbers and furniture (−16.46%), communication and electronic equipment (7.33%), refined petroleum (−12.73%), transport equipment (−3.03%), and construction (−14.60%) in 2020.

-

(4)

DHT: households' demand for passenger transportation would fall with an average of 38.18%. To avoid the infection, people would stay at home instead of traveling, visiting family, or migrate, which would largely reduce the households' demand for passenger transportation. From January to the end of October 2020, the railway, road, waterway, and aviation passenger transportation declined by 43.03%, 48.59%, 47.61%, and 40.28%, respectively (Ministry of Transport of P.R. China, 2020). By the annualizing transformation with the proportion of passenger volume from January to October 2019, households' demand for railway, road, waterway, and aviation passenger transportation would fall by 36.75%, 41.01%, 41.15%, and 33.82%, respectively, in 2020 with an average of 38.18%.

-

(5)

LDT: the production efficiency of transport sectors would be eroded by the nationwide lockdown of transport facilities. The lockdown of transportation facilities, including the railway stations, inter-provincial highway, waterway ports, and airline terminals, damages the production efficiency of transport sectors. Considering the time-uneven pattern of transportation activities and lockdown time, the production efficiency of railway passenger transportation and road passenger transportation would decrease by 4.73% and 2.78%, respectively. Due to the unknown lockdown time of waterway ports, we assume that the shock to waterway passenger transportation is the same as to road passenger transportation (−2.78%). Meanwhile, the production efficiency of aviation passenger transportation would decline by 32.20%, calculated with the changes in annually executed flights of China. The production efficiency of aviation freight transportation would fall by 22.54%, which is calculated by multiplying the efficiency loss of aviation passenger transportation with the proportion of cargo volumes by combination aircrafts in 2019. The detailed calculation method is described in Appendix B.1.

-

(6)

PCT: the rising protective cost would lower the production efficiency of passenger transport sectors and freight transport sectors by 3.00% and 1.50%, respectively. The pandemic would raise the protective cost in the transport sectors, indicating a reduction in the production efficiency of transport sectors. Lee and McKibbin (2004) assumed that protective measures (e.g., disinfection, quarantine, and parking inspection) would lower the production efficiency of passenger transport sectors by 1.50% during the SARS pandemic in 2003. Considering that the duration of COVID-19 pandemic is much longer than the SARS, we assume that the protective measures caused by the former would lower the production efficiency of passenger transport sectors by 3.00%. Moreover, as the protective measures in the passenger transport sectors are more stringent than those in the freight transport sectors, the changes in the production efficiency of freight transport sectors are assumed to be a half of that of passenger transport sectors.

3. Methodology and decomposition analysis approach

3.1. CHINAGEM model

The CGE model has been extensively applied in analyzing economic impacts of infectious diseases (Dixon et al., 2010; McKibbin and Fernando, 2020; Verikios et al., 2011) and the issues about transport sectors (Chen et al., 2016, 2017, 2017b; Betarelli et al., 2020). To assess the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on China's transport sectors, we employ a multi-sectoral CGE model, CHINAGEM, developed by the Institute of Science and Development, Chinese Academy of Sciences, and Centre of Policy Studies, Victoria University of Australia (Horridge, 2003). The CHINAGEM model has been widely used in previous studies (Feng et al., 2018; Peng et al., 2018). The model is solved with the GEMPACK software and contains six economic agents (production, investment, consumption, government, foreign, and inventory) and three primary factors (labor, capital, and land). The modules of production, investment, consumption, exports, and equilibrium are briefly introduced in Appendix A1.

To construct a database for the CHINAGEM model, we make use of China's recently published input-output table of the year 2017 with 149 original production sectors, which includes 10 separate transport sectors. They are railway passenger transportation, railway freight transportation, road passenger transportation, road freight transportation, waterway passenger transportation, waterway freight transportation, aviation passenger transportation, aviation freight transportation, pipeline transportation, and other transportation. The 139 non-transport sectors are aggregated to 42 sectors to simplify the analysis and 52 production sectors are finally obtained (Table A.1).

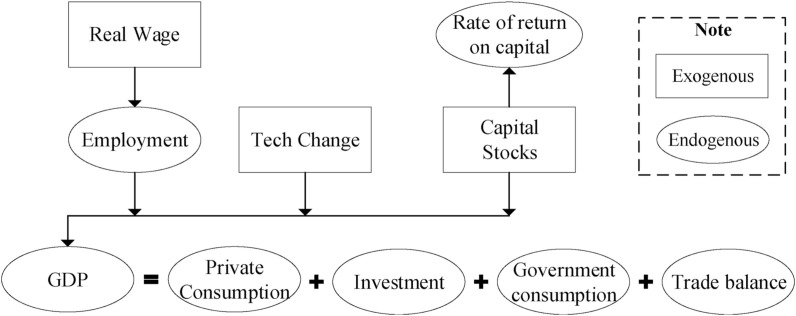

Since the COVID-19 pandemic is expected to persist for several months, we employ a short-run closure for the macro-economic variables. As shown in Fig. 1 , unemployment is allowed with sticky labor wages. The capital is fixed in producing sectors, allowing the return of investment to vary among sectors. The trade balance is endogenized to fill the gap between investment and saving. The shocks specified and calculated in Section 2 are introduced into the CHINAGEM model.

Fig. 1.

The theoretical framework of CHINAGEM model.

3.2. The decomposition method

The decomposition analysis approach, developed by Harrison et al. (2000), can be used to decompose the simulated results for the endogenous variable, such as GDP, employment, and sectoral output, to the contributions of exogenous shocks. The impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on China's transport sectors can be attributed to the six exogenous shocks discussed in Section 2. We employ the decomposition analysis approach in assessing the contribution of each exogenous shock to the aggregated impact of the pandemic.

Supposing that we have just one endogenous variable Z, the relationship between Z and n exogenous variables is represented by Eq. (1).

| (1) |

The vector of exogenous variables, , moves from the pre-simulation value to post-simulation value . Assuming that F is a differentiable function, the contribution of the change in i-th exogenous variable to the change in Z, , is obtained by the line integral (Eq. (2)).

| (2) |

It supposes that the exogenous variables move to their final values along a straight line between the and , which is obtained by changing the elements of as a differentiable function parameterized by t, where , holding the changing rate of the exogenous variables constant along the path.

Then, we re-define the contribution to the change in Z along the path H due to the change in (Eq. (3)).

| (3) |

The total change in Z is computed by summing over all the (Eq. (4)). This implies that the total percentage change in the endogenous variable is equal to the sum of contributions to the percentage change due to different exogenous variables.

| (4) |

From Eqs. (3), (4), the contribution to the percentage change in Z due to different along the path H is estimated by Eq. (5), which could be calculated by the GEMPACK software.

| (5) |

In Section 4, we display the results for the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on transport sectors in China, and decomposing the pandemic impacts to different exogenous shocks from the demand and supply side of transport sectors.

4. Simulation results

4.1. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the outputs of transport sectors

The simulation results suggest that the outputs of all transport sectors are negatively affected by the pandemic. However, the passenger transport sectors would have larger decreases in output than the freight transport sectors (Column 1, Table 1 ), as these sectors are directly exposed to the pandemic, raising their protective cost and reducing the production efficiency, as well as indirectly damaged by the economic recession caused by the shutdown of economic activities and strict social distancing. The output of waterway passenger transportation declines the most, by 11.44% in 2020, followed by road passenger transportation (8.96%) and aviation passenger transportation (5.26%). Compared with these passenger transportations, the decrease in railway passenger transportation is relatively smaller (3.08%), but it is still higher than that of all freight transportation sectors. Compared with passenger transport sectors, the freight transport sectors have much smaller output decreases, as they are mainly indirectly affected by the pandemic, which cuts down the demand of households and production sectors for transportation. Among them, pipeline transportation has the largest output decrease (2.85%). Aviation freight transportation sees a large output reduction by 2.81%, but significantly lower than that of aviation passenger transportation (5.26%). The output of road freight transportation is projected to decline by 2.20%, followed by other transportation (1.84%) and railway freight transportation (1.39%). Although the output of waterway passenger transportation is severely damaged, waterway freight transportation sees a small decrease in output (1.04%).

Table 1.

The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the output of transport sectors (%).

| Transport sectors | Total | Shocks of the pandemic |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSP | DTI | DHC | DHT | LDT | PCT | ||

| Railway passenger | −3.08 | −1.19 | −0.08 | 0.59 | −0.26 | −1.35 | −0.79 |

| Railway freight | −1.39 | −1.68 | −0.01 | 1.31 | −0.07 | −0.93 | −0.01 |

| Road passenger | −8.96 | −0.95 | 0.02 | 0.26 | −5.99 | −1.20 | −1.11 |

| Road freight | −2.20 | −1.24 | −0.21 | −0.09 | −0.13 | −0.12 | −0.42 |

| Waterway passenger | −11.44 | −0.50 | 0.25 | 1.39 | −7.36 | −2.20 | −3.03 |

| Waterway freight | −1.04 | −1.02 | 0.14 | 1.61 | −0.06 | −0.82 | −0.88 |

| Aviation passenger | −5.26 | −1.02 | 0.05 | 0.79 | −0.08 | −4.30 | −0.70 |

| Aviation freight | −2.81 | −1.29 | 0.13 | 1.53 | −0.00 | −3.27 | 0.08 |

| Pipeline | −2.85 | −1.59 | −0.11 | −0.29 | −0.19 | −0.69 | 0.01 |

| Other transportation | −1.84 | −1.43 | −0.13 | 0.56 | −0.08 | −0.53 | −0.24 |

Source: CHINAGEM model.

The various exogenous shocks have different impact mechanisms for the output of transport sectors, which could be categorized into three groups (Column 2–7, Table 1). (1) PSP and DHT lower the demand for transportation of production sectors and households, which causes output declines for all the types of transportation. PSP significantly reduces the production sectors’ demand for transportation, resulting in large output decreases by 0.50%–1.68%. Moreover, PSP has a larger impact on freight transport sectors than on passenger transport sectors, for the shares of freight transportation used by production sectors are much larger than those of passenger transportation. Similarly, DHT also leads to decreases in the outputs of all transport sectors (0.002%–7.36%), but it has larger impacts on passenger transport sectors. (2) DTI and DHC have complicated impact mechanisms as they indirectly influence transport sector output by lowering investment and household consumption. DTI would reduce national investment and sectoral demand for investment commodities, which causes negative impacts on freight transport sectors as the upstream sectors of investment commodities. Meantime, DTI would also reduce the prices of primary factors and enhance the exports, which expands the demand for transportation. Similarly, while DHC damages the output of transport sectors by hindering national consumption, it also benefits the output of several transport sectors for improving exports. (3) LDT and PCT, as supply-side shocks, directly deteriorate the efficiency of the most of the transport sectors. Meanwhile, the PCT also benefits the output of some transport sectors by reducing the prices of primary factors and increasing employment. LDT and PCT have much larger negative impacts on passenger transport sectors than on freight transport sectors.

Also, with the decomposition analysis, the changes in the output of various transport sectors are determined by different exogenous shocks. The decreases in the output of freight transport sectors are highly determined by PSP, DHC, and LDT (Table 1). PSP could explain over 50% of the output damages of freight transport sectors, because freight transportation is mainly utilized by the production sectors. The output of freight transport sectors declines by 1.02–1.68% affected by PSP. Besides PSP, LDT also largely reduces the output of aviation freight transport sectors by significantly reducing their TFP, which explains around 60% of their output damages. For example, LDT reduces the output of aviation freight transportation by 3.27%. Contrarily, DHC significantly raises the output of most freight transport sectors, partly offsetting the damages caused by PSP and LDT. Although DHC lowers household consumption, it also stimulates investment and export, which will raise the demand of production sectors for freight transportations.

Compared with freight transport sectors, the passenger transport sectors are highly determined by PSP, DHT, and LDT. PSP could only largely explain the output damages of the railway and aviation passenger transportation. The output of passenger transport sectors declines by 0.50%–1.19% affected by PSP. Besides PSP, the changes in the outputs of road and waterway passenger transport sectors are highly determined by DHT, which reduces the output of road and waterway passenger transport sectors by 5.99% and 7.36%, respectively. Moreover, LDT is the other important driving factor that reduces the output of the aviation passenger transport sector by 4.30%.

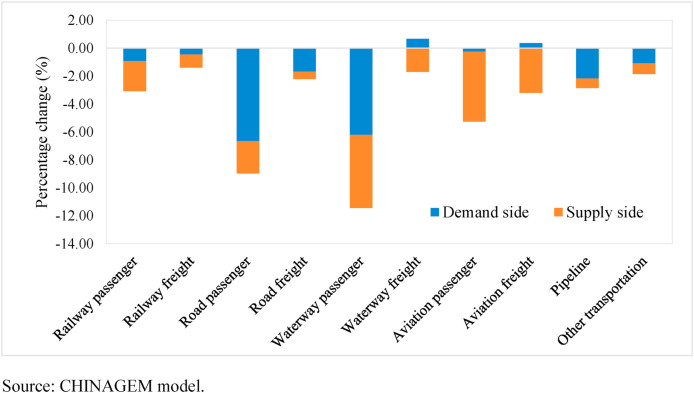

While the decreases in output of railway, waterway, and aviation transport sectors are mainly driven by the supply-side shocks of the COVID-19 pandemic, the output damages of other transport sectors are largely determined by demand-side shocks (Fig. 2 ). The demand-side shocks reduce the demand of production sectors and households for transportation, which adversely affects all transport sectors. Meantime, the supply-side shocks decrease the production of transport sectors by increasing prevention cost and decreasing efficiency. Although both demand- and supply-side shocks negatively affect the output of transport sectors, the impacts of supply-side shocks on the output of railway, waterway, and aviation transport sectors are much larger than those of demand-side shocks. DTI and DHC have moderately positive impacts on the output of railway, waterway, and aviation transport sectors, significantly offsetting the negative impacts caused by other demand-side shocks (PSP and DHT). DTI and DHC lower the prices of primary factors and stimulate exports, consequently raising the export-oriented sectors’ demand for upstream inputs, including the railway, waterway, and aviation transport sectors. Meantime, LDT, as a supply-side shock, would severely negatively affect the output of railway, waterway, and aviation transport sectors. As the negative impacts of supply-side shocks exceed those of demand-side shocks, the outputs of railway, waterway, and aviation transport sectors are mainly driven by the supply-side shocks of the pandemic. In contrast, for the road, pipeline, and other transport sectors, the impacts of demand-side shocks would exceed those of supply-side shocks, which are largely determined by the negative impacts of PSP and DHT.

Fig. 2.

The decomposition impact on the activity level of transport sectors from the demand-side and supply-side shocks (%).

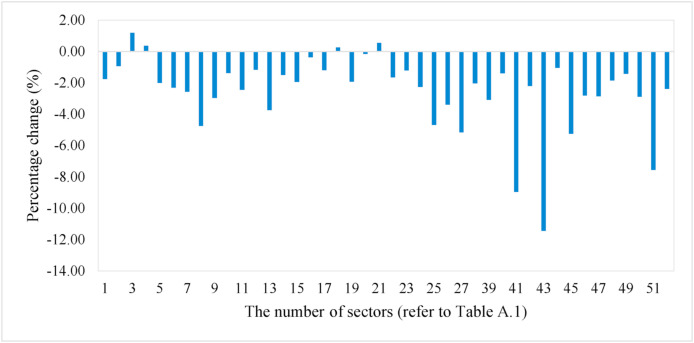

4.2. The impacts on the outputs of non-transport sectors

The simulation results indicate that the COVID-19 pandemic has negative impacts on the output of most non-transport sectors (Fig. 3 ). Of the 42 non-transport sectors, only 4 experience output expansion with an average increase of 0.59%, while the rest experience output reduction with an average decrease of 2.47%. To save space, we only discuss the output changes in the most negatively affected sectors (Table 2 ) as well as the benefited and least negatively affected sectors (Table 3 ) affected by the pandemic.

Fig. 3.

The impacts of the pandemic on the outputs of non-transport sectors (%).

Table 2.

Changes in outputs of the most negatively affected sectors by the pandemic (%).

| Sectors | Total | Shocks of the pandemic |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSP | DTI | DHC | DHT | LDT | PCT | ||

| Accommodation and food services | −7.55 | −1.52 | −0.12 | −5.33 | −0.05 | −0.35 | −0.19 |

| Residential services | −5.20 | −1.48 | −0.41 | −3.07 | −0.16 | −0.04 | −0.04 |

| Construction | −5.15 | −1.69 | −1.31 | −2.80 | −0.62 | 0.94 | 0.33 |

| Clothes, leather and feather | −4.74 | −1.55 | 0.13 | −2.00 | 0.07 | −1.02 | −0.39 |

| Gas supply | −4.68 | −0.79 | −0.31 | −2.56 | −1.38 | −0.06 | 0.41 |

| Nonmetallic mineral products | −3.74 | −1.83 | −0.80 | −1.14 | −0.41 | 0.34 | 0.10 |

| Education | −3.54 | −0.90 | −0.24 | −2.09 | −0.04 | −0.19 | −0.08 |

| Water supply | −3.39 | −0.95 | −0.31 | −2.04 | −0.07 | 0.03 | −0.05 |

| Health care and social welfare | −2.96 | −0.40 | −0.26 | −2.42 | −0.03 | 0.17 | −0.01 |

| Timbers and furniture | −2.95 | −1.72 | −0.17 | −0.04 | −0.07 | −0.65 | −0.30 |

Source: CHINAGEM model.

Table 3.

Changes in outputs of the benefited and least negatively affected sectors affected by the pandemic (%).

| Sectors | Total | Shocks of the pandemic |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSP | DTI | DHC | DHT | LDT | PCT | ||

| Crude petroleum and natural gas | 1.19 | −0.35 | 0.31 | 2.10 | 0.08 | −0.68 | −0.27 |

| Measuring instruments | 0.54 | −2.98 | 0.59 | 4.36 | 0.13 | −0.96 | −0.60 |

| Metal mining | 0.37 | −1.68 | 0.31 | 3.10 | 0.04 | −0.96 | −0.44 |

| Transport equipment | 0.26 | −2.69 | −0.09 | 1.38 | −0.81 | 1.84 | 0.62 |

| Public Administration | −0.12 | −0.05 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 | −0.07 | −0.02 |

| Communication and electronic equipment | −0.15 | −2.54 | 0.53 | 4.12 | 0.18 | −1.81 | −0.63 |

| General-utilized machinery | −0.37 | −2.30 | 0.19 | 3.52 | 0.01 | −1.25 | −0.54 |

| Coal mining | −0.93 | −1.55 | 0.06 | 1.66 | −0.06 | −0.74 | −0.30 |

| Chemicals and chemical products | −1.16 | −2.13 | 0.21 | 2.06 | 0.04 | −0.93 | −0.40 |

| Special-utilized machinery | −1.19 | −2.25 | 0.06 | 3.54 | 0.10 | −1.88 | −0.76 |

Source: CHINAGEM model.

The downstream and upstream sectors along the production chain of transport sectors are among the most severely affected by the pandemic (Table 2). On the one hand, as the major downstream sectors, the output of residential services fall by 5.20%, following construction (5.15%), clothes, leather and feather (4.74%), and nonmetallic mineral products (3.74%). The output damages in transport sectors would largely raise the production costs of these downstream sectors, decreasing their output. Similarly, as the downstream sectors of the construction, the output of water supply decreases by 3.39%, respectively. On the other hand, as the major upstream sectors, accommodation, food services (7.55%) and gas supply (4.68%) suffer from the pandemic, which reduces the demand for these commodities of transport sectors.

Additionally, the reduction of total investment seriously affects construction (5.15%), and timbers and furniture (2.95%), which are mainly used as investment inputs. The decreases in household consumption also reduces the output of residential services (5.20%), education (3.54%), and health care and social welfare (2.96%). The decomposition analysis of exogenous variables shows that the output decreases of the most damaged sectors are more largely driven by the demand-side shocks, compared with the supply-side shocks.

The benefited and the least negatively affected sectors are mainly export-oriented and capital-intensive manufacturing sectors as well as the sectors related to people's livelihoods (Table 3). The benefited sectors include crude petroleum and natural gas (1.19%), followed by the measuring instruments (0.54%), metal mining (0.37%), and transport equipment (0.26%). Their production benefits from DHC, which reduces the production cost of these sectors and raises their competitiveness against the imported commodities. Furthermore, their outputs are significantly stimulated by DTI, except for transport equipment, and the shock would lower the prices of capital and benefit these capital-intensive sectors. The positive effects of the pandemic for these sectors exceed the negative impacts, resulting in output expansion. Crude petroleum and natural gas are closely related to people's livelihoods, so it is relatively less affected by PSP. For similar reasons, several sectors would have relatively small decreases in output. The output of public administration would fall by 0.12%, followed by communication and electronic equipment (0.15%), general-utilized machinery (0.37%), coal mining (0.93%), chemicals and chemical products (1.16%), and special-utilized machinery (1.19%).

4.3. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the macro economy

The COVID-19 pandemic is expected to severely hurt China's macro economy. The real GDP would decrease by 2.71%, accompanied by a decline in employment of 2.72% or the loss of 21.07 million jobs2 (Table 4 ). The economic recession would bring down total investment and household consumption. Moreover, the pandemic significantly reduces the prices of primary factors, which would expand exports by 1.41%, without considering the decreases in the external demand for China's commodities. Our simulated GDP decrease is consistent with previous studies (McKibbin and Fernando, 2020; Wen et al., 2020), but much higher than those that considered countermeasure policies (Chen et al., 2020; Duan et al., 2020; Fernandes, 2020). With the decomposition analysis of exogenous shocks, the demand-side shock, PSP, has the largest impact on real GDP, which accounts for over 50% of the decrease in real GDP (1.42/2.71 = 52.4%). Following the PSP, the DHC, DTI, LDT, and PCT reduce real GDP by 0.36%, 0.24%, 0.29%, and 0.23%, respectively. Compared with the above factors, DHT has many small impacts on real GDP, as it only changes the production efficiency of transport sectors.

Table 4.

The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on China's macro economy (%).

| Economic indicators | Total | Shocks of the pandemic |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSP | DTI | DHC | DHT | LDT | PCT | ||

| GDP | −2.71 | −1.42 | −0.24 | −0.36 | −0.17 | −0.29 | −0.23 |

| Investment | −3.70 | −1.70 | −1.36 | −1.95 | −0.70 | 1.62 | 0.39 |

| Consumption | −6.96 | −0.94 | −0.47 | −5.47 | −0.33 | 0.30 | −0.05 |

| Exports | 1.41 | −0.86 | 0.84 | 4.61 | 0.31 | −2.67 | −0.82 |

| Imports | −7.98 | 1.17 | −2.32 | −10.63 | −1.30 | 3.68 | 1.42 |

| CPI | −7.17 | 1.36 | −1.59 | −10.67 | −0.46 | 3.00 | 1.19 |

| Employment | −2.72 | −1.59 | −0.30 | −0.04 | −0.21 | −0.43 | −0.15 |

Source: CHINAGEM model.

With the expenditure decomposition of real GDP, the exogenous shocks have different impact mechanisms on the macro economy (Table 5 ). PSP directly reduces the sectoral production and total supply, consequently reducing investment, consumption, and exports, in turn adversely affecting GDP (Column 2, Table 5). Unlike PSP, DHT reduces the household demand for transportation, consequently reducing investment and consumption, but lowers the prices of primary factors, which slightly increase total exports. While DTI and DHC reduce total investment and consumption, they also stimulate exports by decreasing the prices of primary factors. The GDP reduction caused by the decrease in investment and consumption exceeds the benefit of the export expansion, which results in moderate GDP loss. The decrease in GDP caused by LDT is mainly driven by the reduction of exports, resulting from the efficiency loss of transport sectors, which offsets the positive impacts of consumption and investment expansion. Additionally, the reduction of GDP caused by PCT is largely derived from the decline in consumption and exports but the investment expansion would slightly offset the GDP damage.

Table 5.

The expenditure decomposition of the changes in real GDP (%).

| Expenditure components | Total | Shocks of the pandemic |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSP | DTI | DHC | DHT | LDT | PCT | ||

| Consumption | −2.61 | −0.36 | −0.18 | −2.05 | −0.12 | 0.11 | −0.02 |

| Investment | −1.57 | −0.72 | −0.58 | −0.83 | −0.30 | 0.69 | 0.17 |

| Export | 0.28 | −0.17 | 0.17 | 0.91 | 0.06 | −0.53 | −0.16 |

| Import | 1.20 | −0.18 | 0.35 | 1.61 | 0.20 | −0.56 | −0.22 |

Source: CHINAGEM model.

5. Conclusions and policy implications

5.1. Conclusions

As one of the most vulnerable to the spread of infectious diseases, all transportation sectors have been severely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic that has had unprecedented effects on economies and people worldwide, including China. However, the shocks and impact mechanisms of infectious diseases on the transport sectors are inadequately understood. This paper employs a multi-sectoral CGE model of China, CHINAGEM, with highly disaggregated transport sectors, to examine the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on China's transport sectors and reveal the impact mechanisms across the economy with the decomposition analysis approach. We contribute to the literature in the following ways: (1) we specify the different shocks of the COVID-19 pandemic on the performance of transport sectors, both from the demand and the supply side; (2) the heterogeneity on the impacts of the pandemic on transport sectors is revealed, highlighting the sectors most vulnerable; (3) the impact mechanisms of the pandemic on the output of transport sectors are quantitatively examined.

The major findings of this paper are as follows. (1) The COVID-19 pandemic has caused multiple shocks to the transport sectors, from the supply side, raising their protective cost and reducing the production efficiency, and from the demand side, reducing the demand of households and production sectors for transportation. We specify six shocks of the COVID-19 pandemic to transport sectors: production shutdown of manufactures and services (PSP), decline in total investment (DTI), decline in household consumption (DHC), decline in household demand for transportation (DHT), the lockdown of transport facilities (LDT) and increase in the protective cost of transport sectors (PCT). (2) The outputs of all transport sectors are severely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic in our study, with passenger transport sectors showing larger output decreases than freight transport sectors. The outputs of freight transport sectors and passenger transport sectors would decline by 1.03–2.85% and 3.08–11.44%, respectively. (3) The decomposition analysis shows that the impacts of various exogenous shocks are different, and the changes in the output of different transport sectors are influenced by different exogenous shocks. The decreases in the output of freight transport sectors are highly determined by PSP, DHC, and LDT. Compared with freight transport sectors, the outputs of passenger transport sectors are highly determined by PSP, DHT, and LDT. (4) While the decreases in the outputs of railway, waterway, and aviation transport sectors are mainly driven by the supply-side shocks of the pandemic, the damages to the outputs of road, pipeline, and other transport sectors are determined by demand-side shocks. Although both demand-side and supply-side shocks hurt the outputs of transport sectors, the impacts of supply-side shocks on outputs of railway, waterway, and aviation transport sectors are much larger than those of demand-side shocks.

Our study also shows that the COVID-19 pandemic negatively impacts the output of most non-transport sectors. Of the 42 non-transport sectors, only four experience output expansion with an average increase of 0.59%, while the rest experience output reduction with an average decrease of 2.47%. The downstream and upstream sectors along the production chain of the transport sectors are most severely damaged by the pandemic. The sectors that are benefited or the least negatively affected are mainly export-oriented and capital-intensive manufacturing sectors and those sectors related to people's livelihoods. In terms of the macro economy, the real GDP would decrease by 2.71%, along with an employment decline of 2.72%. With the decomposition analysis of exogenous shocks, the demand-side shock, PSP, has the largest impact on real GDP, which accounts for over 50% of the decrease in real GDP, and various exogenous shocks have different impact mechanisms on the macro economy.

This paper aims to assess the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on different transport sectors and reveal the major impact mechanisms. Three major limitations exit. First, we use the data available at the end of October 2020, and the unclear future trend of the pandemic generates great uncertainty in accurately assessing the impacts on transport sectors. Second, the reduced external demand for China's commodities and the impact of restriction measures (e.g., import restriction and immigration control) are not considered. Third, the countermeasures adopted by China's government are not considered, which could buffer the impacts of the pandemic on transport sectors. The above factors should be given special attention in future studies.

It is important to ascertain the impact mechanism of public health emergencies to accurately assess the impacts on transport sectors. This study combines the CGE model with a decomposition analysis approach and evaluates the demand-side and supply-side shocks of the COVID-19 pandemic, revealing the contribution of different exogenous shocks to the output changes of various transport sectors. Specifying the source of the damages to output of transport sectors is important to formulate mitigation policies. For example, if the output decreases of transport sectors are dominantly derived from the supply-side shocks (e.g., railway, waterway, and aviation transport sectors), the damages could be effectively buffered by government policies to support the transport sectors. In contrast, for the sectors that are largely affected by the demand-side shocks (e.g., road, pipeline, and other transportation), such policies may be ineffective, and policies stimulating production in other sectors, investment, and household consumption are necessary.

5.2. Policy implications

Based on the findings of this study, three policy implications are recommended to mitigate the damages caused by the COVID-19 pandemic on China's transport sectors, which are also valuable for other countries similarly affected. First, more generous supporting policies should be formulated for passenger transport sectors, as they show much larger negative impacts than any other sector. Since the outbreak of the pandemic, China's governments have enforced a series of policies to support passenger transport sectors, including relaxing taxi franchise fees, exempting passenger vehicles from road tolls, reducing parking charges, and releasing restrictions on vehicles purchase in cities. For example, road tolls in China were exempted from February 17 to May 16 in 2020, exempting road toll revenues of 1.5 billion RMB yuan per day, which significantly reduced road transportation costs. Considering the uncertainty of the duration of the pandemic, the government should extend the period of these supporting policies and enlarge coverage to include more passenger transportation enterprises. More targeted beneficial policies should be made to the most significantly damaged sectors, i.e., waterway and aviation passenger transport sectors. Insurance agencies should appropriately alleviate the insurance fees for ships and planes during the suspense period, and the government should reduce or withdraw value-added tax and provide subsidies for the enterprises that are severely affected. Meanwhile, the resumption of passenger transportation should prohibit the spread of the pandemic across the regions through implementing a strict scrutiny and record system.

Second, the supporting policies for freight transport sectors should focus on alleviating enterprises' production costs and ease their shortage of funds, encouraging them to resume and maintain the production. For example, China's government has exempted the value-added tax for the transportation of epidemic prevention materials and residential materials from January 1 to June 30, 2020. However, the policy coverage of tax rebates and exemption should be further expanded to all transport enterprises, and perhaps the entire year, considering the persistence of the pandemic. Simultaneously, to further lower the transportation cost, the government should optimize the freight transportation structure, by utilizing the advantages of low cost and low energy consumption of railway and waterway transportation, and transforming road transportation to handle the last-mile dilemma. The smart transport system is another important way ahead for freight transport sectors, as the equipment of modernized facilities, such as unmanned aerial vehicles, distribution robots, intelligent warehouses, and unmanned driving, could largely raise efficiencies of transport sectors, while reducing the infection risks.

Third, to stimulate the demand for transportation, the government should accelerate the resumption of industrial production and encourage investment and consumption through fiscal and monetary policy interventions. The policies in force include reducing and exempting enterprises' social insurance expenditure, allowing small and micro enterprises to defer paying the capital and interest, cutting down loan rates, and increasing targeted refinance. For example, China's government has issued new bonds of 1.08 trillion RMB in Q1 2020 to stimulate investment and production and somewhat restore the economic volatility caused by the pandemic. Simultaneously, measures have been implemented to encourage investment by the new infrastructure construction and encourage household consumption via residential consumption vouchers. However, stronger policies are needed to stimulate internal demand.

Authors’ CRediT roles

Qi Cui: Conceptualization, methodology, and writing; Ling He: Data calculation, and writing; Yu Liu: Methodology and software; Yanting Zheng: Writing and revising; Bo Yang: Conceptualization; Wei Wei and Meifang Zhou: Reviewing and Editing.

Declaration of competing interest

Declarations of interest: none.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge funding from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFA0602503), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (71903014, 41001094), and Beijing Municipal Education Commission Research Program (SM202110011012). They also appreciate for the constructive suggestions of the anonymous reviewers.

Glossary

- PSP

the production shutdown of manufactures and services

- DTI

the decline in total investment

- DHC

the decline in household consumption

- DHT

the decline in household demand for transportation

- LDT

the lockdown of transport facilities

- PCT

the increase in the protective cost of transport sectors

- CGE

computable general equilibrium model

Footnotes

The total employment in China was 774.71 million by end of 2019.

Appendix A.

A.1. The modules of the CHINAGEM model

The modules of production, investment, consumption, exports, and equilibrium in the CHINAGEM model are briefly introduced below.

-

(a)

Production

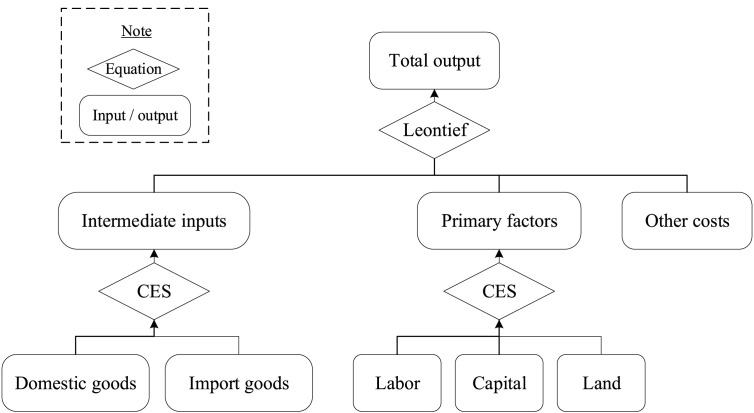

Fig. A.1.

The input structure of production sectors

The producing sectors determine their utilization of intermediate inputs and primary factors according to the cost minimization, and the allocation of outputs in the domestic and international market according to the profit maximization. The nesting production functions are used to describe the input structure used by each producing sector (Fig. A1). On top of the input structure, the intermediate inputs (including transportations), primary factors, and other inputs are composited with Leontief function as shown in Eq. (A.1).

| (A.1) |

The i, c, and s are index industry, commodity, and source, respectively. represents the i-th sector's output. is the intermediate input c used by sector i, which comprises the domestic and import sources with constant elasticity of substitution (CES) function, as shown in Eq. (A.2). represents the primary factor used by the sector c, which comprises labor, capital, and land with CES function, as shown in Eq. (A.3). represents other costs. is the parameter for neutral technological progress. is the technology parameter augmented to intermediate inputs and primary factors.

| (A.2) |

| (A.3) |

-

(b)

Investment

Similar to the intermediate inputs, the sectors determine the purchases of investment commodities according to the cost minimization. On top of the nested structure, the investment of sector i is composited by different investment commodities with a Leontief function (Eq. A.4).

| (A.4) |

where, is the total investment of sector i. is the purchase of investment commodity c by sector i. Similarly, is the parameter for neutral technological progress. is the technology parameter augmented to investment commodities. is the composite of domestic and import sources with CES function as shown in Eq. (A.5).

| (A.5) |

-

(c)

Consumption

The household consumption is determined by the utility maximization subjected to residential income. We employ the Klein-Rubin function to describe the household consumption of different commodities (Eq. A.6).

| (A.6) |

where, U represents the household utility, and Y is the disposal income of a representative household. Q represents the population. is the consumption of commodity c by the household. is the subsistence consumption of commodity c, and is the parameter on the subsistence consumption. is the price of commodity c. represents the marginal consumption propensity of commodity c. With Lagrange optimization, the linear expenditure system is obtained in Eq. (A.7). The consumption of is the composite of domestic and import sources with CES function.

| (A.7) |

-

(d)

Export

| (A.8) |

As shown in Eq. (A.8), the export demand for tradable commodities is negatively correlated with the export price. is the export of commodity c. is the export price in foreign currency, and represents the exchange rate. and are the shift variables to the export curve. The price elasticity of commodity c's export, , is negative.

-

(e)

Equilibrium

Following most CGE models, the general equilibrium of CHINAGEM requires the clearance of all the commodity and factor markets, zero profit of producing sectors, and the balance between saving and investment.

A.2. The aggregated sectors of CHINAGEM model

The aggregated sectors of CHINAGEM model are shown in Table A.1.

Table A.1.

The aggregated sectors of CHINAGEM model.

| No. | Description | No. | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Agriculture | 27 | Construction |

| 2 | Coal mining | 28 | Wholesale and retail trade |

| 3 | Crude petroleum and natural gas | 29 | Rail passenger transportation |

| 4 | Metal mining | 30 | Rail freight transportation |

| 5 | Nonmetallic mining | 31 | City passenger transportation |

| 6 | Food and tobacco | 32 | Road freight transportation |

| 7 | Textiles | 33 | Water passenger transportation |

| 8 | Clothes, leather, and feather | 34 | Water freight transportation |

| 9 | Timbers and furniture | 35 | Aviation passenger transportation |

| 10 | Papermaking, printing, and culture product | 36 | Aviation freight transportation |

| 11 | Refined petroleum, coke, nuclear fuel | 37 | Pipeline transportation |

| 12 | Chemicals and chemical products | 38 | Other transportation |

| 13 | Nonmetallic mineral products | 39 | Cargo handling and storage |

| 14 | Metals processing | 40 | Post |

| 15 | Metal products | 41 | Accommodation and food services |

| 16 | General-utilized machinery | 42 | Information and technology services |

| 17 | Special-utilized machinery | 43 | Finance |

| 18 | Transport equipment | 44 | Real estate |

| 19 | Electrical machinery and apparatus | 45 | Leasing and business services |

| 20 | Communication and electronic equipment | 46 | Scientific research and development |

| 21 | Measuring instruments | 47 | Water and environment administration |

| 22 | Other manufacture | 48 | Residential services |

| 23 | Scrap, waste, and machine repair | 49 | Education |

| 24 | Electricity supply | 50 | Health care and social welfare |

| 25 | Gas supply | 51 | Culture, sports, and entertainment |

| 26 | Water supply | 52 | Public administration |

Appendix B.

B.1. The calculations on the shocks to the efficiencies of different transport sectors

The detailed calculations on different shocks of the COVID-19 pandemic to the efficiency of various transport sectors are as follows.

-

(1)

The shock to the efficiency of railway passenger transportation. According to the National Railway Administration, P.R. China, 80 railway stations except for Wuhan in Hubei Province, 17 railway stations in Wuhan, and 13 railway stations in Henan Province have suspended passenger operations for 66, 76, and 65 days, respectively, during the pandemic period, while the remaining 2337 stations are open. Taking the share of each region's railway passenger volume in national railway passenger volume in 2019 as the weight, the average shutdown time of national railway stations is 16.91 days. Given that the operation time of all the stations is 366 days in 2020, the efficiency of the railway passenger transportation will decrease by 4.62% (=16.91/366). Considering the assumption of non-uniformity, we scale the shock using the adjustment coefficient of 1.02, which is equal to the proportion of railway passengers from January to October 2019 (85.41%) divided by 83.33% (=10/12). Thus, the efficiency loss of the railway passenger transport sector is 4.73% (=4.62% * 1.02).

-

(2)

The shock to the efficiency of road passenger transport. According to the suspension time of inter-provincial-highway passenger stations in 31 provinces in China, the suspension time varies from 16 to 182 days (Table B.1). Taking the share of provincial highway passenger flow in the national highway passenger flow as the weight, the average shutdown time of inter-provincial-highway passenger stations in the whole country is 39.5 days. Compared with 366-day operation time, the productivity of inter-provincial-highway passenger transportation decreases by 10.79% (=39.5/366). Considering the non-uniformity, we calculate the adjustment coefficient of 1.08 using the proportion of highway passenger flow from January to October 2019 (90.33%) divided by 83.33% (10/12). We find that the efficiency of the inter-provincial-highway passenger transportation falls by 11.69% (=10.79%*1.08). Assuming that the urban public transportation will also be affected where the inter-provincial-highway passenger transportation suspended operation, we obtain that the loss of the efficiency of the urban public transportation is 11.69%. Due to the lack of data on private cars, we assume that the shock on the efficiency of private cars is only −2% affected by the lockdown of cities in Hubei, Henan, and Anhui. The private cars account for 92% of the total passenger vehicles in 2019, while other vehicles (urban public and inter-provincial-highway passenger transport vehicles) accounted for 8%. Taking this proportion as the weight, we can calculate that the efficiency of road passenger transport sector decreases by 2.78% (=92% * 2.00% + 8% * 11.69%).

Table B.1.

The suspension period of cross-provincial public road passenger transportation in China

| Regions | Suspension period | Suspension days | Regions | Suspension period | Suspension days | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Beijing | 1/26–7/26 | 182 | 17 | Hubei | 1/26–4/30 | 95 |

| 2 | Tianjin | 1/26–3/15 | 49 | 18 | Hunan | 1/26–3/5 | 39 |

| 3 | Hebei | 1/26–3/5 | 39 | 19 | Guangdong | 1/26–3/2 | 36 |

| 4 | Shanxi | 1/26–3/7 | 41 | 20 | Guangxi | 1/27–2/22 | 26 |

| 5 | Inner Mongolia | 1/26–2/21 | 26 | 21 | Hainan | 1/26–2/23 | 28 |

| 6 | Liaoning | 1/25–2/29 | 35 | 22 | Chongqing | 1/26–3/3 | 37 |

| 7 | Jilin | 1/26–2/28 | 33 | 23 | Sichuan | 1/25–3/5 | 40 |

| 8 | Heilongjiang | 1/25–3/4 | 39 | 24 | Guizhou | 1/25–2/21 | 27 |

| 9 | Shanghai | 1/26–3/15 | 49 | 25 | Yunnan | 1/26–3/2 | 36 |

| 10 | Jiangsu | 1/25–3/12 | 47 | 26 | Tibet | – | 0 |

| 11 | Zhejiang | 1/27–2/18 | 22 | 27 | Shaanxi | 1/26–2/26 | 31 |

| 12 | Anhui | 1/26–3/6 | 40 | 28 | Gansu | 1/30–2/16 | 17 |

| 13 | Fujian | 1/26–2/26 | 31 | 29 | Qinghai | 1/27–2/25 | 29 |

| 14 | Jiangxi | 1/27–3/3 | 36 | 30 | Ningxia | 1/27–2/29 | 33 |

| 15 | Shandong | 1/25–3/12 | 47 | 31 | Xinjiang | 1/27–2/12 | 16 |

| 16 | Henan | 1/26–3/10 | 44 |

Source: The Transportation Administration of each province and public information.

-

(3)

The shock to the efficiency of waterway passenger transportation. Due to the lack of data on the suspension time of each waterway port, we assume that the shock of the waterway passenger transportation is the same as that of road passenger transportation, that is, the efficiency of the waterway passenger transport sector decreases by 2.78%.

-

(4)

The shock to the efficiency of aviation passenger transportation. Since Wuhan was sealed off from all outside contact on January 23, executed-flights of domestic airlines have declined precipitously from January 29. Assuming that executed-flights can return to normal by the end of October, the number of daily-executed flights during the non-pandemic period in 2020 will remain the same as that in 2019, with an average of 13,203 daily-executed flights. The average daily-executed flights are 8902 during the pandemic period. As a result, the annual-executed flights in 2020 are 3.6453 million (13,203*90 + 8902*276), while that in 2019 are 4.8192 million. Finally, the growth rate of annual-executed flights in 2020 is −32.20%, which represents the shock on the efficiency of aviation passenger transportation.

-

(5)

The shock to the efficiency of aviation freight transportation. Affected by the pandemic, a large number of passenger routes in China have been suspended, and the cargo-carrying capacity of domestic and international flights has been greatly weakened. Assuming that the cargo aircraft is not affected much by the pandemic, the efficiency change of domestic and international aviation freight transportation could be scaled using the proportion of combination aircraft's aviation freight volumes to total aviation freight volumes in 2019. Because the proportions of freight volumes of combination aircraft are 70.0%, the efficiency of aviation freight transportation drops by 22.54% (=32.20% * 70.0%).

References

- Beck M.J., Hensher D.A. Insights into the impact of COVID-19 on household travel and activities in Australia–The early days of easing restrictions. Transport Pol. 2020;99:95–119. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2020.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betarelli A.A., Jr., Domingues E.P., Hewings G.J.D. Transport policy, rail freight sector and market structure: the economic effects in Brazil. Transport. Res. Pol. Pract. 2020;135:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Blake A., Sinclair M.T., Sugiyarto G. Quantifying the impact of foot and mouth disease on tourism and the UK economy. Tourism Econ. 2003;9(4):449–465. [Google Scholar]

- Bombelli A. Integrators' global networks: a topology analysis with insights into the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Transport Geogr. 2020;87:102815. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2020.102815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai J., Xu B., Chan K.K.Y., Zhang X., Zhang B., Chen Z., Xu B. Roles of different transport modes in the spatial spread of the 2009 influenza A (H1N1) pandemic in mainland China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2019;16(2):222. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16020222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Yang C., Bao Q., Zhu K., Wang H., Jiang Q., Wang S. Bulletin of Chinese Academy of Sciences; 2020. Impacts of COVID-19 Outbreak on China's Economy and Policy Suggestions. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z., Daito N., Gifford J.L. Socioeconomic impacts of transportation public-private partnerships: a dynamic CGE assessment. Transport Pol. 2017;58:80–87. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z., Rose A.Z., Prager F., Chatterjee S. Economic consequences of aviation system disruptions: a reduced-form computable general equilibrium analysis. Transport. Res. Pol. Pract. 2017;95:207–226. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z., Xue J., Rose A.Z., Haynes K.E. The impact of high-speed rail investment on economic and environmental change in China: a dynamic CGE analysis. Transport. Res. Pol. Pract. 2016;92:232–245. [Google Scholar]

- China ChengXin International Credit Rating Co, Ltd Ccxi Special review on China's transportation industry. 2020. http://www.ccxi.com.cn/cn/Research/info/19055 February 2020. Available at:

- Chou J., Kuo N.F., Peng S.L. Potential impacts of the SARS outbreak on Taiwan's economy. Asian Econ. Pap. 2004;3(1):84–99. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon P.B., Lee B., Muehlenbeck T., Rimmer M.T., Rose A., Verikios G. Effects on the US of an H1N1 epidemic: analysis with a quarterly CGE model. J. Homel. Secur. Emerg. Manag. 2010;7(1) [Google Scholar]

- Dong H., Ma S., Jia N., Tian J. Understanding public transport satisfaction in post COVID-19 pandemic. Transport Pol. 2020;101:81–88. [Google Scholar]

- Duan H., Wang S., Yang C. Coronavirus: limit short-term economic damage. Nature. 2020;578(7796):515. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-00522-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans D.K., Ferreira F., Lofgren H., Maliszewska M., Over M., Cruz M. 2014. Estimating the economic impact of the ebola epidemic: evidence from computable general equilibrium models. [Google Scholar]

- Feng S., Howes S., Liu Y., Zhang K., Yang J. Towards a national ETS in China: cap-setting and model mechanisms. Energy Econ. 2018;73:43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes N. 2020. Economic Effects of Coronavirus Outbreak (COVID-19) on the World Economy. Available at SSRN 3557504. [Google Scholar]

- Gaskin D.J., Zare H., Delarmente B. Geographic disparities in COVID-19 infections and deaths: the role of transportation. Transport Pol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2020.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan D., Wang D., Hallegatte S., Davis S., et al. Global supply-chain effects of COVID-19 control measures. Nat. Human Behav. 2020;4:577–587. doi: 10.1038/s41562-020-0896-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrieri V., Lorenzoni G., Straub L., Werning I. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2020. Macroeconomic Implications of COVID-19: Can Negative Supply Shocks Cause Demand Shortages? (No. W26918) [Google Scholar]

- Harrison J., Horridge M., Pearson K.R. Decomposing simulation results with respect to exogenous shocks. Comput. Econ. 2000;15(3):227–249. [Google Scholar]

- Hensher D.A., Wei E., Beck M.J., Balbontin C. The impact of COVID-19 on cost outlays for car and public transport commuting-the case of the Greater Sydney Metropolitan Area after three months of restrictions. Transport Pol. 2020;101:71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Horridge M. Monash University; Australia: 2003. ORANI-G: A Generic Single-Country Computable General Equilibrium Model. Centre of Policy Studies and Impact Project. [Google Scholar]

- Hu S., Chen P. Who left riding transit? Examining socioeconomic disparities in the impact of COVID-19 on ridership. Transport. Res. Transport Environ. 2020;90:102654. [Google Scholar]

- International Air Transport Association IATA Updated impact assessment of the novel Coronavirus. 2020. http://www.iata.org/economics Available at:

- International Monetary Fund IMF . IMF; Washington, DC: 2020. World Economic Outlook Database April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao J., Zhang F., Liu J. A spatiotemporal analysis of the robustness of high-speed rail network in China. Transport. Res. Transport Environ. 2020;89:102584. [Google Scholar]

- Johns Hopkins University COVID-19 dashboard by the center for systems science and engineering (CSSE) at johns Hopkins university (JHU) 2020. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html

- Jonung L., Roeger W. 2006. The Macroeconomic Effects of a Pandemic in Europe-A Model-Based Assessment. Available at SSRN 920851. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P., Sachan A., Kakar A., Gogia A. Socioeconomic impact of the recent outbreak of H1N1. Curr. Med. Res. Pract. 2015;5(4):163–167. [Google Scholar]

- Lau H., Khosrawipour V., Kocbach P., Mikolajczyk A., Ichii H., Zacharksi M., Khosrawipour T. The association between international and domestic air traffic and the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.W., McKibbin W.J. Globalization and disease: the case of SARS. Asian Econ. Pap. 2004;3(1):113–131. [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Gayle A.A., Wilder-Smith A., Rocklöv J. The reproductive number of COVID-19 is higher compared to SARS coronavirus'. J. Trav. Med. 2020;27(2) doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa021. PMID: 32052846; PMCID: PMC7074654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loske D. The impact of COVID-19 on transport volume and freight capacity dynamics: an empirical analysis in German food retail logistics. Transport. Res. Interdiscipl. Perspect. 2020;6:100165. doi: 10.1016/j.trip.2020.100165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKibbin W.J., Fernando R. 2020. The Global Macroeconomic Impacts of COVID-19: Seven Scenarios. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Transport of P.R. China Statistical data. 2020. http://www.mot.gov.cn/tongjishuju/

- Nakamura H., Managi S. Airport risk of importation and exportation of the COVID-19 pandemic. Transport Pol. 2020;96:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2020.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Bureau of Statistics The monthly statistical data of China. 2020. https://data.stats.gov.cn/easyquery.htm?cn=A01 Access at:

- National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China (NHC) The latest statistic of the COVID-19 pandemic. 2020. http://www.nhc.gov.cn Access at: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Oum T.H., Wang K. Socially optimal lockdown and travel restrictions for fighting communicable virus including COVID-19. Transport Pol. 2020;96:94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2020.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng X., Adams P.D., Liu J. China's new growth pattern and its effect on energy demand and greenhouse gas emissions. Glob. Energy Interconnect. 2018;1(4):428–442. [Google Scholar]

- Peng Z. Influence of COVID-19 on civil aviation and policy recommendations. Transport. Res. 2020;6(1):33–44. [Google Scholar]

- Petrosillo N., Viceconte G., Ergonul O., Ippolito G., Petersen E. COVID-19, SARS and MERS: are they closely related? Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020;26(6):729–734. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Przemysław Borkowski, Jażdżewska-Gutta Magdalena, Szmelter-Jarosz Agnieszka. Lockdowned: everyday mobility changes in response to COVID-19. J. Transport Geogr. 2020;90:102906. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2020.102906. ISSN 0966–6923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi X., Ge J., Chen X., Tian F., Gao T. The short-term impact of new crown pneumonia on civil aviation and the countermeasures. 2020. http://att.caacnews.com.cn/zsfw/202002/t20200214_28164.html Available at:

- Regondi I., George G., Pillay N. HIV/AIDS in the transport sector of southern Africa: operational challenges, research gaps and policy recommendations. Dev. South Afr. 2013;30(4–5):616–628. [Google Scholar]

- Shi X., Luo Y., Zhou L. China Aviation News; 2020. China's Aviation Freight Situation and Countermeasures under the Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia. 3551 issue. [Google Scholar]

- Smith R.D., Keogh-Brown M.R., Barnett T. Estimating the economic impact of pandemic influenza: an application of the computable general equilibrium model to the UK. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011;73(2):235–244. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suau-Sanchez P., Voltes-Dorta A., Cugueró-Escofet N. An early assessment of the impact of COVID-19 on air transport: just another crisis or the end of aviation as we know it? J. Transport Geogr. 2020;86:102749. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2020.102749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng T., Liu Z., Zhang H. WANB Institute; 2020. Panoramic Perspective of the Impact of the Epidemic on China's Economy.http://www.wanb.org.cn/yjcg/gkfb/2020/0225/540.html Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Verikios G., Sullivan M., Stojanovski P., Giesecke J.A., Woo G. Centre of Policy Studies (CoPS); 2011. The Global Economic Effects of Pandemic Influenza. [Google Scholar]

- Wen Y., Zhang T., Du Q. Quantifying the COVID-19 economic impact. 2020. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3546308 Available at SSRN: [DOI]

- Yang Y., Zhang H., Chen X. Coronavirus pandemic and tourism: dynamic stochastic general equilibrium modeling of the infectious disease outbreak. Ann. Tourism Res. 2020:102913. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2020.102913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yetkiner H., Beyzatlar M.A. The Granger-causality between wealth and transportation: a panel data approach. Transport Pol. 2020;97:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2020.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. Transport policymaking that accounts for COVID-19 and future public health threats: a PASS approach. Transport Pol. 2020;99:405–418. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2020.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S., Moeckel R., Moreno A.T., Shuai B., Gao J. A work-life conflict perspective on telework. Transport. Res. Pol. Pract. 2020;141:51–68. doi: 10.1016/j.tra.2020.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Yahua, Zhang A., Wang J. Exploring the roles of high-speed train, air and coach services in the spread of COVID-19 in China. SSRN Electr. J. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2020.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]