Abstract

Study Objectives:

The stress imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic and ensuing social isolation could adversely affect sleep. As sleep problems may persist and hurt health, it is important to identify which populations have experienced changes in sleeping patterns during the pandemic and their extent.

Methods:

In Study 1, 3,062 responders from 49 countries accessed the survey website voluntarily between March 26 and April 26, 2020, and 2,562 (84%; age: 45.2 ± 14.5, 68% women) completed the study. In Study 2, 1,022 adult US responders were recruited for pay through Mechanical Turk, and 971 (95%; age 40.4 ± 13.6, 52% women) completed the study. The survey tool included demographics and items adapted from validated sleep questionnaires on sleep duration, quality and timing, and sleeping pills consumption.

Results:

In Study 1, 58% of the responders were unsatisfied with their sleep. Forty percent of the responders reported a decreased sleep quality vs before COVID-19 crisis. Self-reported sleeping pill consumption increased by 20% (P < .001). Multivariable analysis indicated that female sex, being in quarantine, and 31- to 45-years age group, reduced physical activity and adverse impact on livelihood were independently associated with more severe worsening of sleep quality during the pandemic. The majority of findings were reproduced in the independent cohort of Study 2.

Conclusions:

Changes imposed due to the pandemic have led to a surge in individuals reporting sleep problems across the globe. The findings raise the need to screen for worsening sleep patterns and use of sleeping aids, especially in more susceptible populations, namely, women and people with insecure livelihoods subjected to social isolation.

Citation:

Mandelkorn U, Genzer S, Choshen-Hillel S, et al. Escalation of sleep disturbances amid the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional international study. J Clin Sleep Med. 2021;17(1):45–53.

Keywords: insomnia, sleep disturbances, COVID-19, lockdown, sleep quality

BRIEF SUMMARY

Current Knowledge/Study Rationale: Preliminary data suggest that the COVID-19 pandemic impairs sleep quality in the health care workers and possibly on a larger scale in the population. It is still unclear what is the global effect of COVID-19 on sleep patterns and what populations are most vulnerable.

Study Impact: Between March 26 and April 26, 2020, 2,562 adults from 49 countries completed an online survey. Forty percent of the responders reported reduced sleep quality. Those in quarantine, women, and workers whose livelihood was adversely impacted were most severely affected. Sleeping pills consumption increased by 20%. The findings were reproduced in an independent cohort of 971 US adults. In summary, changes imposed due to the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in a significant worsening of sleep quality across the globe.

INTRODUCTION

Sleep is vital for almost every aspect of human life. Insufficient sleep exerts an immense negative impact on health, increasing the risk of obesity, cardiovascular and metabolic disease, and mood and cognitive disorders, ultimately resulting in accelerated cellular senescence and overall aging.1,2 Sleep disturbances are so prevalent in the general population, ranging from 15-25% in the United States,3 that they have been declared a public health epidemic.4 Not only sleep quantity but also subjective sleep quality is important for wellness.5 Poor sleep quality is associated with cardiovascular and coronary heart disease,6 obesity and chronic kidney disease,7 and poor mental health,8 with various sleep disturbances linked to suicidality, independently from the underlying psychiatric morbidities.9

Stressful life events play a major role in the pathogenesis of sleep disturbances, combined with predisposing factors of personal vulnerability.10 During times of stress, existing sleep disturbances may be exacerbated and new ones may emerge.11 In December 2019, the novel severe acute respiratory distress coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2),12,13 dubbed Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), emerged as a global pandemic. Numerous countries implemented protective measures, most notably widespread lockdowns, which have markedly changed the customs and home and work practices of their entire population. The stress induced by the rapidly spreading disease, the abrupt cutoff of social interactions, and the disruption to daily routines have dramatically affected people’s sense of security and well-being.14 We hypothesized that these extreme changes related to the pandemic have altered sleep patterns. This research therefore sought to evaluate the changes in sleep patterns associated with the COVID-19 pandemic and to characterize populations whose sleep was most severely affected.

Our study focused on the most common sleep disturbances, namely, those related to the quality or timing of sleep, which can be categorized as associated with insomnia or circadian-clock rhythms, respectively.15 Insomnia is characterized by a difficulty to initiate sleep and stay asleep, and the perception of nonrestorative or poor-quality sleep that results in daytime dysfunction.16 Insomnia is highly prevalent across the globe17: Roughly a third of the population reports insomnia symptoms at some point during their lifetime and up to 10% the population has experienced chronic insomnia disorder (> 3 months duration).17,18 Insomnia is commonly encountered in primary care, and is more prevalent in women and in people with underlying medical or psychiatric conditions.19 Circadian-rhythm sleep disorders are a group of sleep-wake disturbances caused by misalignment between a person’s internal biological clock and social demands, such as a school or work schedule. Alignment of the circadian rhythm is maintained with proper sleep hygiene and circadian entrainment with light and dark cues. Loss of the regular maintenance of this system would lead to or worsen existing circadian disorders. These disorders often impair daytime function and are common among night-shift workers, adolescents, and psychiatric patients.20

We hypothesized that the COVID-19 pandemic has affected both insomnia- and circadian-rhythm–related disorders. Further, we postulated that certain sociodemographic categories, such as female sex or people with financial insecurity, would be more strongly associated with worsening sleep and with more prevalent sleep disturbances due to the crisis.

To test our hypotheses, we conducted 2 large-scale online studies. Study 1 was distributed internationally between March 26 and April 26, 2020. It was advertised as a sleep-related study and distributed through social platforms and personal communications. Participation was voluntary. Study 2 was conducted to validate the findings of Study 1. It was distributed through Mechanical Turk online platform on April 17–20, 2020. To avoid a self-selection bias of participants interested in sleep, this study advertisement did not mention sleep. Only adults from the United States were invited to participate in return for payment.

METHODS

We conducted 2 large, cross-sectional online surveys of adult responders (≥ 18 years of age). Informed consent was obtained prior to participation in the survey, which was approved by the Hebrew University of Jerusalem’s School of Business Administration Institutional Review Board. Study subjects were informed that the data collected would be kept anonymous and de-identified, and that their role in the study would be completely voluntary.

Participants

In Study 1,503 out of the 3,065 responders opened the survey but did not complete it. The final analysis included only the 2,562 responders (84%) with full responses. For Study 2, to achieve a varied sample of US age and socioeconomic groups, 1,022 responders were recruited from Amazon’s Mechanical Turk.21 Those who failed an attention check or who did not answer all questions were excluded (n = 51). The final analysis included the remaining 971 (95%) responders.

Procedure

Study 1 was distributed for 1 month, from March 26 to April 26, 2020. Responders were invited to take part in a survey on their sleep patterns during COVID-19. An electronic link to the survey was distributed worldwide by the study’s researchers via a range of methods: invitation via e-mail, Hadassah Medical Center’s website, and social media platforms, such as Facebook WhatsApp, Twitter, and LinkedIn. To avoid a bias toward recruiting responders with an interest in sleep, in Study 2 the invitation did not include any mention of this topic. This survey was distributed through the Amazon Mechanical Turk platform between April 17 and 20, 2020. Responders were paid USD $0.5 for completing the survey. Participants were required to answer all questions except for their location.

Study 1 was administered in English, Hebrew, French, Spanish, Portuguese, Russian, and Arabic, after translation and back translation by native speakers. The same distribution strategy and same survey tool were used in the different languages. Study 2 was administered in English only. It took responders 5–10 minutes to complete the survey.

Survey instrument

Study 1

The survey was distributed online using Qualtrics software (Qualtrics LLC, Provo, UT). Responders were asked to answer 26 multiple-choice items and 10 open-ended items. First, they were presented with sleep-related items selected from validated screening tools, including the Insomnia Severity Index,22 Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index,23 and the National Sleep Foundation sleep satisfaction tool.24 To keep the survey brief, we selected only the items most pertinent to sleep quality from the original forms. Participants were asked about their sleep duration, pre-existing sleeping problems, sleep satisfaction, changes in sleep quality due to the pandemic and their nature, sleeping pill consumption, and their dream patterns. Responders who indicated a change in sleep patterns, were presented with a list of 12 possible reasons and asked to select the reasons most applicable to them for this change.

Finally, responders reported their age, sex, education, occupation, parental status, physical activity, and whether the pandemic affected their physical activity levels or livelihood. The full survey can be found in the supplemental material.

Study 2

The Study 2 survey format replicated that of Study 1, with the only difference being that some new items were added to assess changes in weight and smoking and alcohol consumption habits following the crisis (supplemental material). In this study, we also explored whether disease activity correlated with the degree of new-onset sleep problems.

Analysis

The analysis was primarily descriptive using the R statistical software package. The primary analysis was to evaluate the difference between sleep complaints before and during the COVID-19 crisis. Exploratory analyses included examination of the association of sleep outcomes with variables that potentially influence sleep, such as age, sex, financial security, marital status, parental status, and physical activity. Since sleep disturbances are more prevalent in women,25 we explored sex effect on sleep separately in a univariate analysis.

To identify predictors of changes in sleep quality following COVID-19, we computed a composite sleep quality change score (SQCS). Three items were used to calculate SQCS: (1) change in sleep patterns, (2) change in continuous sleep, and (3) change in sleeping pills consumption. Each of the measures received a value of (0) no change, (1) change for the worse, and (−1) change for the better. The scores were summed for each respondent. SQCS above 0 were considered to indicate sleep worsening, SQCS below 0 were considered to indicate improved sleep. A score of 0 indicated no change in sleep (Table S2 in the supplemental material).

A multivariable logistic regression model that included variables that potentially influence sleep was constructed, in each study separately, to examine predictors of worsening SQCS following the crisis. Age was divided into 4 groups based on the distribution of Study 1 responders and entered as a grouped variable into the regression.

We tested the correlation between the SQCS and the reported cumulative death rate per million people on the date each responder completed the survey, for each state in the United States in Study 1 and for each country in Study 2 (www.ourworldindata.org; accessed September 16, 2020). Comparisons were done using standard statistical tests, with a two-tailed P-value < .05 considered significant.

RESULTS

Study 1

Characteristics of the 2,562 responders who completed the survey are presented in Table 1. Responders’ mean age was 45.18 ± 14.46 years, 1,742 (68%) were women, and 65% were married. Eighty-seven percent of the responders had an academic degree. The geographical distribution of the responders who reported their location (76%) was: Israel (29%), South America (18%), Europe (14%), North America (12%), Asia (2%), and other (1%), from 49 countries overall. A large portion of the responders (n = 1,071, 42%) reported being in quarantine, either imposed by the government or self-imposed. Women were more likely than men to report being in quarantine. Sixty-one percent reported being less physically active following the crisis. The majority of the responders did not have any underlying medical conditions (Table S3). Only 6 responders reported being sick with COVID-19 and 10 had recovered from it.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics and sleep quality.

| Study 1 (n = 2,562) | Study 2 (n = 971) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (standard deviation) | 45.18 (14.46) | 40.36 (13.61) |

| 18–30 years | 17.00% | 29.00% |

| 31–45 years | 36.40% | 39.40% |

| 46–60 years | 30.60% | 21.20% |

| > 60 years | 16.00% | 10.40% |

| Sex, female | 68.18% | 52.79% |

| Education level | ||

| College degree or higher | 87.16% | 76.52% |

| High school | 6.27% | 22.14% |

| Elementary | 0.34% | 0.41% |

| Other | 6.23% | 0.93% |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 22.83% | 42.22% |

| Married | 65.14% | 45.42% |

| Divorced | 8.86% | 8.75% |

| Other | 3.16% | 3.60% |

| Religion | ||

| Secular | 41.84% | 30.69% |

| Traditional | 26.35% | 21.11% |

| Religious | 20.42% | 35.84% |

| With children ≤ 6 years | 79.34% | 80.64% |

| Livelihood affected by COVID-19 pandemic | 69.87% | 59.84% |

| Change in physical activity level following COVID-19 | ||

| None | 20.41% | 29.76% |

| More | 17.84% | 22.55% |

| Less | 61.75% | 47.68% |

| Change in sleep patterns following COVID-19 | ||

| None | 38.80% | 40.99% |

| Better | 21.08% | 20.80% |

| Worse | 40.13% | 38.21% |

| Sleep problems before COVID-19 | 30.44% | 35.63% |

| Change in sleep problems (% of those with sleep problems) | ||

| None | 44.87% | 37.86% |

| Better | 21.53% | 19.08% |

| Worse | 33.60% | 43.06% |

| Change in dream patterns | 36.77% | 32.54% |

| Desire to change sleep patterns | 58.32% | 53.55% |

Sleep patterns—baseline before COVID-19 crisis and changes following the crisis

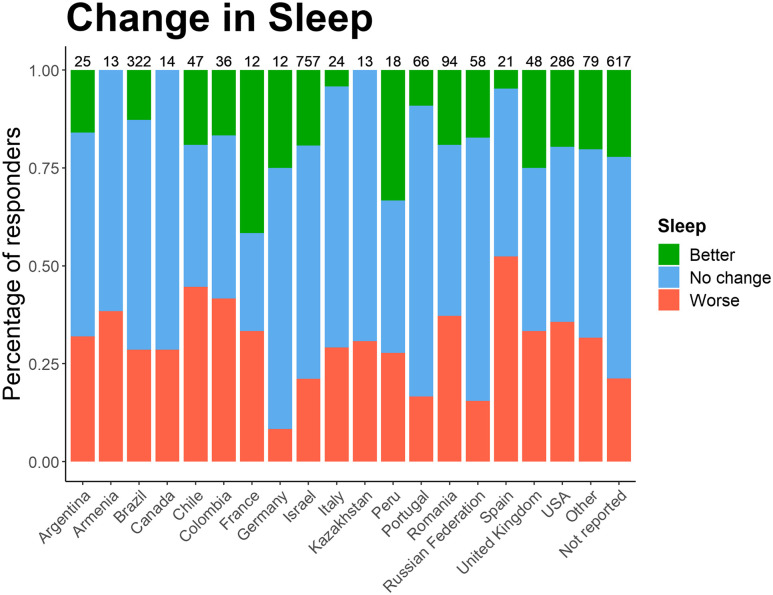

The average reported sleep duration per night before the crisis was 6.9 ± 1.1 hours, with 42% reporting sleeping less than the recommended 7 hours of sleep. Following the crisis, the average sleep duration increased to 7.2 ± 1.6 hours (P < .001), with 35% reporting less than 7 hours of sleep (Table 2). Forty percent reported a worsening of sleep, 39% no change, and 21% improved sleep. Fifty-eight percent were dissatisfied with their current sleep patterns. Geographic variation was apparent with respect to sleep change, with responders from Spain reporting the highest rates of worsening sleep, and those from Germany the lowest (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Change in sleep parameters following COVID-19.

| Study 1 | Study 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | Since | Δ (Δ%) | Before | Since | Δ (Δ%) | |

| Sleep duration, hours, mean (standard deviation) | 6.94 (1.07) | 7.2 (1.59) | 0.26 (3.75%)* | 7.36 (1.35) | 7.34 (1.68) | –0.02 (–0.27%) |

| < 7 hours per night | 41.57% | 35.87% | –5.70% (–13.71%)* | 29.25% | 35.94% | 6.69% (22.87%)* |

| Continuous sleep | 56.91% | 46.84% | –10.07% (–17.69%)* | 49.12% | 48.2% | –0.92% (–1.87%) |

| Sleeping pills | 8.27% | 9.95% | 1.68% (20.31%)* | 14.32% | 17.82% | 3.50% (24.44%)* |

Results on items reported before and since COVID-19 pandemic; within-subject comparison; *P < .001.

Figure 1. Country distribution and the rate of those reporting worsening of sleep in Study 1.

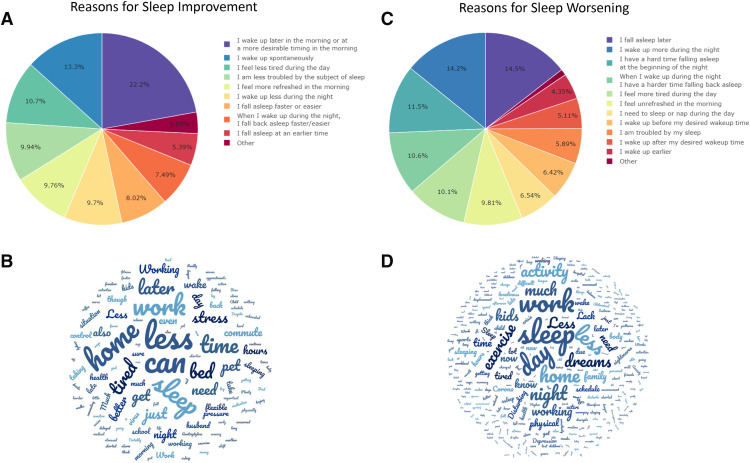

Complaints relating to a change in sleep following the crisis were divided into 3 categories. Insomnia complaints included difficulty falling asleep, waking up during the night, and difficulty falling asleep after waking up during the night. Circadian rhythm-related complaints included falling asleep at a later-than-usual time and waking up earlier or later than the desired time. Daytime dysfunction complaints included feeling unrefreshed in the morning, needing to take a nap, or feeling tired during the day. As the survey dealt with acute changes following the pandemic, the complaints did not fulfill the 3-month chronicity criterion for classification as a disorder.15 We found that in those reporting worsened sleep, 81.4% complained of insomnia and 74.6% of circadian rhythm (these 2 issues often overlapped). In addition, 62% of those whose sleep worsened also experienced daytime dysfunction, which was associated with both insomnia and circadian rhythm complaints. Figure 2 presents the frequency of reasons for altered sleep.

Figure 2. Reasons for sleep improvement or worsening.

Results from multiple-choice questions on reasons for sleep improvement (A) and worsening (C). Word clouds of free-text responses on sleep improvement (B) or worsening (D). Larger words appear more frequently; generated through Wordclouds.com.

There was an increase in sleeping pill consumption, from 8.2% of responders prior to the crisis to 10% following it (approx. 20% increase, P < .001).

More than a third of the responders reported a change in dream patterns, most commonly manifested as more vivid and memorable dreams.

Overall, women were more likely to develop sleep disturbances following COVID-19 crisis. While similar proportions of women and men reported sleeping continuously through the night before the current crisis, women were more likely to report interrupted sleep following the crisis. Women, but not men, increased their consumption of sleeping pills. Women had 30% higher odds than men of experiencing underlying sleep problems before the crisis. Following the crisis, women with underlying sleep problems had 80% higher odds than men of a worsening of those problems (Table 3).

Table 3.

Univariate analysis of the effect of female sex on baseline and new-onset sleep disturbances.

| Variable | Study 1 (n = 2,562) | Study 2 (n = 971) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratios | 95% CI | z | Odds Ratios | 95% CI | z | |

| Desire to change sleep patterns | 1.82*** | 1.54–2.15 | 6.94 | 2.17*** | 1.68–2.81 | 5.90 |

| Worsening of sleep quality since COVID-19 | 1.89*** | 1.58–2.26 | 7.03 | 1.99*** | 1.53–2.6 | 5.09 |

| Sleep problems before COVID-19 | 1.33** | 1.1–1.6 | 3.00 | 1.65*** | 1.26–2.16 | 3.67 |

| Worsening of pre-existing sleep problems | 1.82*** | 1.35–2.49 | 3.82 | 1.38 | 0.89–2.15 | 1.44 |

| Consumption of sleeping pills before COVID-19 | 1.42* | 1.04–1.98 | 2.13 | 1.82** | 1.26–2.67 | 3.13 |

| Began consuming sleeping pills since COVID-19 | 1.96* | 1.17–3.46 | 2.46 | 2.74** | 1.48–5.41 | 3.08 |

| Sleep was discontinuous before COVID-19 | 0.88 | 0.75–1.04 | –1.46 | 0.81 | 0.63–1.04 | –1.64 |

| Sleep became discontinuous since COVID-19 | 1.61** | 1.17–2.25 | 2.84 | 1.09 | 0.74–1.61 | 0.44 |

*P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; odds ratio > 1 indicate increased odds for female vs male. CI = confidence interval.

Predictors of worsening sleep following COVID-19 crisis

The SQCS was used to identify predictors of a change in sleep quality for the whole cohort. Table 4 presents the variables independently associated with worsening sleep quality: female sex (odds ratio [OR] = 1.45, 95% confidence interval [CI95%] = 1.17–1.80, P = .001), being in quarantine (OR = 1.32, CI95% = 1.08–1.61, P = .006), livelihood adversely affected by the crisis (OR = 1.38, CI95% = 1.11–1.71, P = .004), and reduction in physical activity (OR = 1.25, CI95% = 1.03–1.53, P = .027). Age also played a role, whereby people aged 60 years and above had lower odds for worsening sleep (OR = 0.73, CI95% = 0.53–0.99, P = .045) compared to the 45–60 age group. Those aged 31–45 had slightly higher odds of worsening sleep, compared to the 45–60 age groups, although this finding did not reach statistical significance.

Table 4.

Multivariable logistic regression demonstrating factors independently associated with worsening sleep quality following COVID-19.

| Variable | Study 1 (n = 1,994) | Study 2 (n = 753) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratios | 95% CI | z | Odds Ratios | 95% CI | z | |

| Age | ||||||

| 18–30 years | 1.02 | 0.75–1.37 | 0.13 | 1.48 | 0.94–2.34 | 1.67 |

| 31–45 years | 1.21 | 0.93–1.58 | 1.42 | 1.63* | 1.06–2.52 | 2.21 |

| 46–60 years | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| >60 years | 0.73* | 0.53–0.99 | –2.00 | 1.15 | 0.65–2.02 | 0.48 |

| Female sex | 1.45*** | 1.17–1.80 | 3.40 | 1.82*** | 1.33–2.50 | 3.74 |

| Being in quarantine | 1.32** | 1.08–1.61 | 2.76 | 1.31 | 0.96–1.79 | 1.73 |

| Having young children | 0.97 | 0.73–1.28 | –0.23 | 1.36 | 0.90–2.06 | 1.45 |

| Livelihood affected by COVID-19 pandemic | 1.38** | 1.11 – 1.71 | 2.90 | 1.72*** | 1.25–2.38 | 3.33 |

| Less physical activity | 1.25* | 1.03–1.53 | 2.21 | 1.84*** | 1.36–2.51 | 3.90 |

*P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; odds ratio > 1 indicated increased odds for sleep quality change score (SQCS) > 0. CI = confidence interval.

COVID-19 activity level as measured by mortality rate in each country during the time of the survey had a minimal, albeit statistically significant effect on the SQCS (R2 = .003, P < .05).

Study 2

Mean age of the 971 responders was 40.4 ± 13.6, 53% were women and 45% were married. Seventy-seven percent of the responders had an academic degree. Four-hundred eighty-two responders (n = 50%) reported being in quarantine. Twenty-seven percent of the responders reported a weight gain following the crisis, 6% began to smoke, and 16% increased their alcohol consumption. Almost half the responders were less physically active than in the period prior to the crisis. The majority of the responders did not have any underlying medical conditions (Table S3). Only 12 people reported contracting COVID-19 and an additional 11 had recovered from the disease. See Table 1 for a comparison of the responders’ characteristics of the two studies.

Sleep patterns—baseline before COVID-19 crisis and changes following the crisis

Despite apparent differences in the population surveyed in Study 2, the changes in sleep patterns of this cohort replicated those observed in Study 1. Namely, in Study 2, almost 40% reported sleep worsening, with over half being dissatisfied with their current sleep patterns. Of note, sleeping pills consumption before the crisis among Study 2 responders was almost double that of Study 1 responders (14.3% vs 8.2%; P < .001); however, the increase in consumption following the crisis was similar, approx. 20% from baseline (17.8% and 10.0%, respectively). In Study 2, no change was reported in the sleep duration or continuous sleep following the crisis.

Of those reporting that their sleep worsened, 83% complained of insomnia, and 83% complained of changes to the circadian rhythm (the 2 issues often overlapped). In addition, 60% of the responders who reported worse sleep also noted daytime dysfunction, which was associated with both insomnia and circadian rhythm complaints.

Predictors of worsening sleep following the COVID-19 crisis

We used the same predictors as those in Study 1 for worsening sleep, as determined by the SQCS. The results were remarkably similar (Table 3). Thus, female sex, adverse effect on livelihood, and reduction in physical activity were all found to be significant and independent predictors of worsening sleep. Being in quarantine also had an influence, but it did not reach statistical significance. Similar to Study 1, responders aged 31–45 years were more affected than older age groups, although those in the > 60 age group had more variable results, possibly due to their smaller number in this study.

As in Study 1, COVID-19 activity level as measured by disease-related mortality in each state during the time of the survey had a minimal effect on the SQCS (R2 = .007, P = .097).

Health care workers’ sleep following the COVID-19 crisis in Study 1 and Study 2

Four hundred seventy-eight responders in Study 1, and 54 responders in Study 2 reported they were health care professionals (eg, physicians, nurses, nurse practitioners, and laboratory technicians). Their sleep patterns and the patterns of the change following COVID-19 crisis largely reproduced those of the general cohort surveyed (Table S1 and Table S2). Sleep duration increased to a lesser degree in health care compared to non-health care responders, possibly because the crisis had less impact on their livelihood. In line with recent reports,26 health care occupation was associated with worsening sleep scores in both studies (OR = 1.25, CI95% = 0.99–1.58, P = .057 in Study 1; OR = 2.10, CI95% = 1.14–3.93, P =.018 in Study 2). However, when health care occupation was entered into a multivariable regression analysis as specified above, this association disappeared in both Study 1 and Study 2, indicating that health care occupation may not predispose directly to worsening sleep following the crisis. It should be noted that health care workers in our studies were not asked to report whether they had a direct contact with COVID-19 patients. Recent studies show that these workers are the ones who are most affected by the crisis.26

DISCUSSION

Two large-scale international surveys conducted during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic revealed that the prevalence of sleep disturbances among adults rose significantly. While sleep duration did not change markedly, new complaints of insomnia, altered circadian rhythm, and daytime dysfunction appeared in a third of the responders. A significant increase in the consumption of pharmacological sleeping aids was also documented. The populations most susceptible to new onset of sleep disturbances were women, people aged 31–45, those in quarantine, those less physically active, and those whose livelihood was adversely affected. All findings were highly consistent across the surveys, one of which included around 2,500 responders from 49 countries, and the other which recruited about 1,000 paid responders from the United States.

The changes in sleep patterns revealed herein are particularly concerning as they may persist even when the pandemic’s intensity abates and precautionary measures are dismissed. Our study raises awareness of this global problem and calls for timely interventions aimed at preventing persistent sleep problems and the associated impairments in physical and psychological wellbeing. In particular, health care providers should foster screening for worsening sleep and the use of sleeping aids, especially in the more susceptible populations as identified herein.

Sleep disturbances observed in the current study

Among responders who reported worsening in their sleep following the pandemic, new onset insomnia symptoms combined with daytime dysfunction were common. Insomnia may well be the result of stress and perceived sleep quality. Daytime dysfunction and sleepiness may be the result of disorders affecting sleep duration or continuity of sleep architecture, like mood disorders, obstructive sleep apnea, narcolepsy, or systemic inflammation.27 Isolated daytime complaints of sleepiness and fatigue were rare among our responders.

Circadian misalignment was also highly prevalent—it was reported in 75% of the responders who complained of worsening in their sleep. Circadian misalignment is a common consequence of social isolation.28 This disruptive behavior affects the maintenance of a stable internal time and frequently results in circadian sleep-wake disorders, which may overlap with insomnia.29 Interestingly, the social distancing strategy could be counterproductive in this sense, as it could involve a higher risk of immune system changes that contribute to an increased vulnerability to SARS-CoV-2 infection.30

While self-reported sleep duration increased in our sample to some extent (compared to before the crisis), the reported sleep quality worsened in a large proportion of our responders. Perceived sleep quality, which constitutes an important dimension of a healthy sleep, can be influenced by anxiety, stress, and hyperarousal,3 all of which were prevalent in the current crisis.31 Our findings underscore the fact that adequate sleep duration does not guarantee healthy sleep. We did not collect data on psychological distress and thus cannot link sleep quality to anxiety directly in our study.

Effect of sex on sleep

We found that women were more likely to experience sleep disturbances prior to the crisis. Indeed, sex is a well-established risk factor for insomnia, with an overall 40% excess risk, which increases with advancing age.32 Two surveys from China, one conducted among medical personnel treating COVID-19 patients,33 and the other in the general population during the initial time period of the crisis,34 reported that insomnia symptoms at that time were more prevalent in women. However, these studies did not explore whether women were more likely to develop new insomnia symptoms following the crisis. Importantly, our data suggests that women were also at greater risk of new-onset sleep disturbances following the crisis. This newly described vulnerability of women in our study for new-onset sleep disturbances is worrisome and deserves special attention in the design of future interventions aimed at mitigating the psychological effects of the COVID-19 crisis.

Similarly, increased consumption of sleeping pills among women (but not men) following the crisis, as reported here, is worrisome and is consistent with consumer-based reports in the media indicating such an increase.35 Such medications, including benzodiazepines, antihistamines, Z-drugs, and others, have a high rate of dependence and are fraught with potentially significant side effects.36

Effects of quarantine on sleep

We found a clear effect of quarantine on the prevalence of sleep disturbances, with a higher proportion of those quarantined reporting insomnia symptoms. Quarantine was also associated with the risk of worsening sleep quality in both cohorts. Our findings are consistent with earlier reports from China, where anxiety and depression were almost twice as likely to occur in people in quarantine.37 In China, only those with poor sleep quality and in areas highly affected by the disease reported an increase in post-traumatic stress symptoms38 and anxiety34; similar findings were obtained with respect to medical personnel treating COVID-19 patients.39 Our findings suggest that during consideration of quarantining a population for a prolonged period of time due to a pandemic, the sleep domain should be included in advice regarding general well-being measures.

Relations to current literature on COVID-19 and sleep

As of today, there are only sparse findings on the effects of the pandemic on sleep. A recent study in China documented a strong association between COVID-19 activity in different geographical areas and new-onset of insomnia.40 Another 2 studies, 1 from adult populations in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland41 and the other from university students in Colorado,42 reported improved sleep-wake timing following the crisis. Additional survey from Italy consisting primarily of women found high prevalence of reduced sleep quality.43 Our study provides a bigger picture of the current sleep situation in the world. It contributes to the understanding of the effect of the pandemic on sleep by providing a variety of sleep measures, and identifying several factors that affect vulnerability (eg, sex and age). As for the geographical factor, in line with the Chinese study, we observed more changes in sleep quality in countries that were more affected by the pandemic (eg, Spain). However, we did not find any association between COVID-19 disease activity and sleep quality in US states. This may be due to limited spatial and temporal resolution.

Sleep and the risk to be infected and develop COVID-19

Our study did not examine the effects of sleep on the risk to get infected with COVID-19. Yet the role of sleep in adaptive and innate immunity is well established. Sleep duration and quality have bidirectional associations with immune response to various pathogens,44 and sleep boosts immunological memory formation.45 Thus, we speculate that it is likely that improved sleep quality and duration in the population may mitigate the propagation and severity of disease induced by SARS-Cov-2 infection.30

Limitations and methodological considerations

We opted for an online-based study due to the ease of obtaining a large number of responders quickly and the ability to reach responders from multiple countries simultaneously (although we note that the Asia-Pacific region was under-represented), without breaching quarantine or social distancing measures. We are aware that such an approach may under-represent sectors of the population that are less likely to engage in social media activities, such as individuals of lower socioeconomic status or the elderly. To overcome this limitation, we conducted Study 2, which recruited a more representative sample of the US population. Additionally, to address a potential selection bias in Study 1, which was advertised as a sleep study, Study 2 did not mention this topic. While the cohorts of the 2 studies differed in age, sex, education, and religion characteristics, remarkably similar results in sleep patterns and predictors of sleep worsening have emerged. This effectively rules out the concern regarding participant selection bias and adds to the generalizability of our findings.

Another limitation of our study relates to the nature of the survey, which is based on self-reporting. While self-reporting may suffer from a recall bias, subjective complaints of sleep are generally correlated with various health outcomes and are therefore a valid indicator of changes in sleep patterns.

Finally, we conducted this survey during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic in most countries. As mentioned above, more often than not, acute disturbances in sleep quality tend to resolve over time. Thus, the changes in sleep reported in the survey may be temporal. Nonetheless, a significant proportion of sleep disturbances may persist,10 making the findings more worrisome.

CONCLUSIONS

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to a significant disruption in sleep patterns in the general population, likely due to the lockdown and related stress. Raising public and medical awareness to these new sleep problems is essential, due to the long-lasting deleterious effects they may have on human health and wellbeing. In particular, this research raises the need to screen for worsening sleep patterns and use of sleeping aids in the more susceptible populations identified in this study, namely, women and people with insecure livelihoods or those subjected to strict quarantine. Health care providers should pay special attention to physical and psychological problems that this surge in sleep disturbances may cause.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

All authors have seen and approved the final version of the manuscript. A. Gileles-Hillel is supported by the Israel Science Foundation (grant # 2779/19). The authors report no conflicts of interest.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the study responders who, during this stressful period, invested time and effort to advance science. Author contributions: U. Mandelkorn conceptualized the study and drafted portions of the manuscript. S. Genzer analyzed the data. S. Choshen-Hillel and D. Gozal drafted portions of the manuscript. J. Reiter, M. Meira e Cruz, H. Hochner, and L. Kheirandish-Gozal contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. A. Gileles-Hillel had full access to all the data in the study, drafted the final version of the manuscript, and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CI95%

95% confidence interval

- COVID-19

Coronavirus disease 2019

- OR

odds ratio

- SQCS

Sleep Quality Change Score

REFERENCES

- 1.Léger D, Bayon V. Societal costs of insomnia. Sleep Med Rev. 2010;14(6):379–389. 10.1016/j.smrv.2010.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cappuccio FP, D’Elia L, Strazzullo P, Miller MA. Sleep duration and all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Sleep. 2010;33(5):585–592. 10.1093/sleep/33.5.585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grandner MA. Sleep, health, and society. Sleep Med Clin. 2017;12(1):1–22. 10.1016/j.jsmc.2016.10.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.NHLBI . 2017; https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/sleep-deprivation-and-deficiency. Accessed September 15, 2020.

- 5.Buysse DJ. Sleep health: can we define it? Does it matter? Sleep. 2014;37(1):9–17. 10.5665/sleep.3298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kwok CS, Kontopantelis E, Kuligowski G, et al. Self-reported sleep duration and quality and cardiovascular disease and mortality: a dose-response meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(15):e008552. 10.1161/JAHA.118.008552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fatima Y, Doi SA, Mamun AA. Sleep quality and obesity in young subjects: a meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2016;17(11):1154–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Espie CA, Emsley R, Kyle SD, et al. Effect of digital cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia on health, psychological well-being, and sleep-related quality of life: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(1):21–30. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.2745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geoffroy PA, Oquendo MA, Courtet P, et al. Sleep complaints are associated with increased suicide risk independently of psychiatric disorders: results from a national 3-year prospective study. Mol Psychiatry. 2020. 10.1038/s41380-020-0735-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morin CM, Drake CL, Harvey AG, et al. Insomnia disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1(1):15026. 10.1038/nrdp.2015.26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miyata M, Hata T, Kato N, et al. Dynamic QT/RR relationship of cardiac conduction in premature infants treated with low-dose doxapram hydrochloride. J Perinat Med. 2007;35(4):330–333. 10.1515/JPM.2007.068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pneumonia of unknown cause—China: disease outbreak news. 2020; https://www.who.int/csr/don/05-january-2020-pneumonia-of-unkown-cause-china/en/. Accessed September 16, 2020.

- 13.Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. China medical treatment expert group for Covid-19 . Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708–1720. 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abu-Shaweesh JM, Martin RJ. Neonatal apnea: what’s new? Pediatr Pulmonol. 2008;43(10):937–944. 10.1002/ppul.20832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sateia MJ. International classification of sleep disorders-*third edition: highlights and modifications. Chest. 2014;146(5):1387–1394. 10.1378/chest.14-0970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morphy H, Dunn KM, Lewis M, Boardman HF, Croft PR. Epidemiology of insomnia: a longitudinal study in a UK population. Sleep. 2007;30(3):274–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foley DJ, Monjan AA, Izmirlian G, Hays JC, Blazer DG. Incidence and remission of insomnia among elderly adults in a biracial cohort. Sleep. 1999;22(Suppl 2):S373–S378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roth T, Jaeger S, Jin R, Kalsekar A, Stang PE, Kessler RC. Sleep problems, comorbid mental disorders, and role functioning in the national comorbidity survey replication. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60(12):1364–1371. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.05.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Culnan E, McCullough LM, Wyatt JK. Circadian rhythm sleep-wake phase disorders. Neurol Clin. 2019;37(3):527–543. 10.1016/j.ncl.2019.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paolacci G, Chandler J. Inside the Turk: understanding Mechanical Turk as a participant pool. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2014;23(3):184–188. 10.1177/0963721414531598 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morin CM, Belleville G, Bélanger L, Ivers H. The Insomnia Severity Index: psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep. 2011;34(5):601–608. 10.1093/sleep/34.5.601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28(2):193–213. 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohayon MM, Chen MC, Bixler E, et al. A provisional tool for the measurement of sleep satisfaction. Sleep Health. 2018;4(1):6–12. 10.1016/j.sleh.2017.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.2007 Sleep in America poll–2007 women and sleep. Sleep Health. 2015;1(2):e6. 10.1016/j.sleh.2015.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(3):e203976. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barateau L, Lopez R, Franchi JA, Dauvilliers Y. Hypersomnolence, hypersomnia, and mood disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017;19:13. 10.1007/s11920-017-0763-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aschoff J. [Circadian rhythm in man in isolation]. Verh Dtsch Ges Inn Med. 1967;73:941–942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee H-J. Human circadian rhythm and social distancing in the COVID-19 crisis. Chronobiol Med. 2020; 2(2). 10.33069/cim.2020.0013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meira ECM, Miyazawa M, Gozal D. Putative contributions of circadian clock and sleep in the context of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Eur Resp J. 2020;56(3) 2001023. 10.1183/13993003.01023-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xiong J, Lipsitz O, Nasri F, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:55–64. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang B, Wing YK. Sex differences in insomnia: a meta-analysis. Sleep. 2006;29(1):85–93. 10.1093/sleep/29.1.85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang C, Yang L, Liu S, et al. Survey of insomnia and related social psychological factors among medical staff involved in the 2019 novel coronavirus disease outbreak. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:306. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin LY, Wang J, Ou-Yang XY, et al. The immediate impact of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak on subjective sleep status [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 1]. Sleep Med 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.05.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beebe DW, Ris MD, Kramer ME, Long E, Amin R. The association between sleep disordered breathing, academic grades, and cognitive and behavioral functioning among overweight subjects during middle to late childhood. Sleep. 2010;33(11):1447–1456. 10.1093/sleep/33.11.1447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hampton LM, Daubresse M, Chang HY, Alexander GC, Budnitz DS. Emergency department visits by adults for psychiatric medication adverse events. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(9):1006–1014. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lei L, Huang X, Zhang S, Yang J, Yang L, Xu M. Comparison of prevalence and associated factors of anxiety and depression among people affected by vs people unaffected by quarantine during the covid-19 epidemic in southwestern China. Med Sci Monit. 2020;26:e924609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang F, Shang Z, Ma H, et al. High risk of infection caused posttraumatic stress symptoms in individuals with poor sleep quality: a study on influence of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in China. medRxiv. Preprint posted online on March 24, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xiao H, Zhang Y, Kong D, Li S, Yang N. The effects of social support on sleep quality of medical staff treating patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in January and February 2020 in China. Med Sci Monit. 2020;26:e923549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morin CM, Carrier J. The acute effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on insomnia and psychological symptoms [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 6]. Sleep Med 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blume C, Schmidt MH, Cajochen C. Effects of the COVID-19 lockdown on human sleep and rest-activity rhythms. Curr Biol. 2020;30(14):R795–R797. 10.1016/j.cub.2020.06.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wright KP Jr, Linton SK, Withrow D, et al. Sleep in university students prior to and during COVID-19 Stay-at-Home orders. Curr Biol. 2020;30(14):R797–R798. 10.1016/j.cub.2020.06.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Innocenti P, Puzella A, Mogavero MP, Bruni O, Ferri R. Letter to editor: CoVID-19 pandemic and sleep disorders-a web survey in Italy. Neurol Sci. 2020;1–2. 10.1007/s10072-020-04523-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Besedovsky L, Lange T, Haak M. Sleep-immune crosstalk in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2019;99(3):1325–1380. 10.1152/physrev.00010.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lange T, Dimitrov S, Bollinger T, Diekelmann S, Born J. Sleep after vaccination boosts immunological memory. J Immunol. 2011;187(1):283–290. 10.4049/jimmunol.1100015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.