Abstract

Unpleasant dreamlike mentation can occur during non-rapid eye movement parasomnias, leading to associated panic attacks. The mentations are rarely remembered and are likely underreported. However, they may lead to significant personal distress and, if not addressed, may contribute to poorer clinical outcomes. Cotard le délire de negation are very rare nihilistic delusions, historically described with psychotic disorders. Their association with a variety of neurologic disorders, including migraine and cluster-headache, has also been reported. Here we present three cases of Cotard parasomnia during which distinct states of consciousness defined by nihilistic ideation occurred. Patients described believing they are dead or dying, while unable to perceive or experience their bodies in whole, or in part, as their own. A source analysis of the electroencephalographic fingerprint of these mentations suggests right-hemispheric hypoactivity subsequent to confusional arousals. Mechanistically, an aberrant activation of two major intrinsic brain networks of wakefulness, the salience network and the default mode network, is argued.

Citation:

Gnoni V, Higgins S, Nesbitt AD, et al. Cotard parasomnia: le délire de negation that occur during the sleep-wake dissociation? J Clin Sleep Med. 2020;16(6):971–976.

Keywords: Cotard delusion, non-REM parasomnia, sleep-wake transition, sleep, major intrinsic networks, salience network, default mode network, EEG

INTRODUCTION

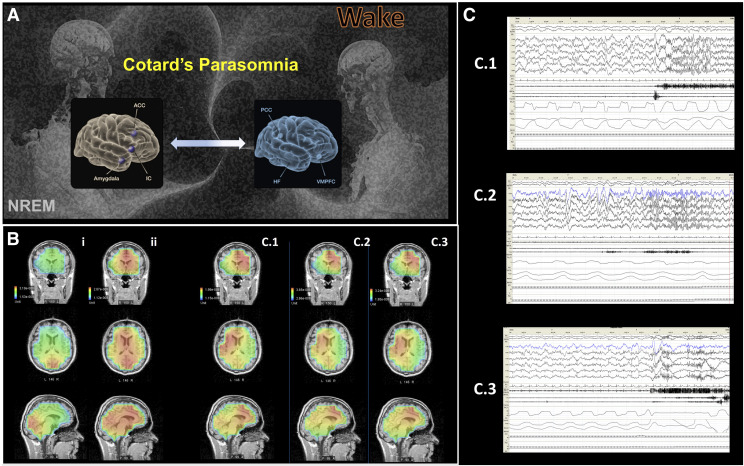

Arousal parasomnias are traditionally viewed as mosaic states during which there is a breakdown of boundaries between wakefulness and non–rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep, resulting in their coexistence.1 Dreamlike mentation can occur during NREM parasomnias2,3 and here we present three cases of Cotard parasomnia in which patients described distinct, short-lived states of consciousness defined by a complete (acenesthopathy4) or a partial (hypocenesthopathy4) loss of perception of their own body and existence, or an aberrant (paracenesthopathy4) perception. Jules Cotard’s (published in 1880) eponymous syndrome remains poorly understood and shrouded in mystery; its unique phenomenology is, however, rich and, at its very elemental, involves delusional belief that one is dead, dying, or nonexistent accompanied by nihilistic thoughts regarding specific body parts or the whole self (see Table 1).5,6 It has been traditionally described in the context of major depression with psychotic symptoms, paranoid schizophrenia, and bipolar affective disorder.5 However, Cotard syndrome has also been associated with a variety of other psychiatric and neurological disorders, and a diathesis for pathological functioning of the right (nondominant) fronto-insular cortex and nodes of the default mode network (DMN) has been put forward to explain its origin (Figure 1A; for a recent review of functional and neuroimaging studies see Restrepo-Martínez et al6).

Table 1.

Cotard phenomenology of parasomnic events.

| Patient | Age/Sex | ICSD-3 Diagnoses | Comorbidities | Cotard Phenomenology of the Event with Associated EEG Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 59 y/F | NREM-related parasomnia (confusional arousals) | Bipolar affective disorder, unspecified | Representative description: “My body is drained of blood and I know I am dying or dead” (sic) |

| Obstructive sleep apnea | Mild cognitive impairment, unspecified | Predominant phenomenology: hypocenesthopathy (eg, a hypotrophic alteration in the sense of bodily being caused by abnormal, bizarre sensations in the body), acenesthopathy (eg, a total absence of the sense of physical existence), alexisomia (eg, difficulty in experiencing and expressing bodily feelings), nihilistic delusion, ideas of damnation and rejection, anxiety. | ||

| PSG report: An EEG arousal is seen arising from SWS (shift from delta to alpha waves), and then 4 seconds after this arousal, the patient very suddenly lifts her head off the pillow and starts frantically kicking her legs and moving her arms in a panicked manner. Her pulse rate increases from approximately 68 bpm to 134 bpm. This appeared to be preceded by a hypopnea, but it is unclear whether this caused the panicked response. A large amount of movement artifact was observed, but the patient appeared to be awake throughout. | ||||

| 2 | 33 y/M | NREM-related parasomnia (confusional arousals) | Representative description: “I am dead, I do not exist, I worry if I will be able to return into my body, and I have to pinch myself to check if my body is alive” (sic) | |

| Periodic limb movement disorder | Predominant phenomenology: acenesthopathy, alexisomia, nihilistic delusion, ideas of damnation, anxiety. | |||

| PSG report: The study confirmed the presence of a NREM parasomnia with three episodes seen. These all involved the patient suddenly sitting up in bed from N3 sleep with eyes open and looking around as if confused. There was alpha seen on the EEG during the arousal and the patient returned to sleep quickly after each arousal. | ||||

| 3 | 35 y/M | NREM-related parasomnia (confusional arousals) | Chronic migraine | Representative descriptions: “I am rising above my body, my body feels empty, and my soul has left my body as a large lump of sugar” (sic) |

| Periodic limb movement disorder | Ankylosing spondylitis | “I have only my head and my hands. The rest of me is not there. It is just not there.” (sic) | ||

| Obstructive sleep apnea | Gout | “My body feels heavy and huge. It is something different, I cannot describe it, it is not me.” (sic) | ||

| Mild learning disability | Predominant phenomenology: hypocenesthopathy, paracenesthopathy (eg, a qualitative alteration in the sense of bodily being, caused by abnormal, bizarre sensations in the body), alexisomia, nihilistic delusion, anxiety, somatic and visual hallucinations. | |||

| PSG report: The EEG showed a normal reactive background rhythm with all the expected features of wake and sleep seen. Two isolated bi-occipital discharges (sharp waves) were noted during NREM sleep of uncertain clinical significance. In the first cycle of SWS, a period limb movement is seen causing arousal in which he lifts his head from the pillow and looks around before returning to sleep. |

bpm = beats per minute; EEG = electroencephalograms; F = female; ICSD-3 = International Classification of Sleep Disorders, third edition; M = male; N3 = NREM stage three; PSG = polysomnography; sic = sic erat scriptum (Latin); SWS = slow-wave sleep.

Figure 1. Mechanistic model of Cotard parasomnia, its EEG topography, and representative EEG tracings from three cases.

(A) We argue that Cotard parasomnia and its associated phenomenology may be a product of an incomplete, and likely fluctuating, activation and switching between the two major intrinsic networks of wakefulness, the salience network (SN, gray brain model) and the default mode network12 (DMN, blue brain model) during the period of sleep-wake transition (A, adapted from G. Altmann, Pixabay). (B) In support of this hypothesis, representative source localization of electroencephalograms (EEG) are shown that correlate to the Cotard experiential events from the three cases (B, columns C.1, C.2, C.3). Initially (>10 seconds post-arousal), a significantly lateralized, dominant (L, left) oscillatory activity in the insular cortices (IC) and anterior cingulate cortical nodes (ACC) (SN; C.1–3) is demonstrated. Subsequently (>30 seconds post-arousal, B, ii), a more uniform activation of bilateral mesial structures of DMN occurs. Of note is a remarkably uniform oscillatory topography of Cotard parasomnic events across the investigated events; as demonstrated by the representative events from the three cases (B, C.1–3). By comparison, in the case of a nonconfusional arousal, a divergent topography with oscillatory activity predominantly localized to occipital cortices is seen (also see a representative nonconfusional arousal, B, i). (C) Representative EEG tracing descriptions from cases 1–3 (C, C.1–3). In C.1 a standard PSG shows N3 sleep characterized by delta waves and a sudden arousal with EEG change to alpha activity, followed by muscle artifact. Similarly, C.2 depicts arousal from SWS and shows N3 sleep characterized by delta waves with a sudden arousal and EEG change to alpha activity, followed by muscle artifact. Finally, in C.3 the N3 is shown, characterized with high delta waves with the patient’s baseline overriding alpha. A sudden arousal is shown into wake with fast alpha, significant muscle activity, and artifacts. Brief arrest in nasal airflow is also evident. ACC = anterior cingulate cortex; DMN = default mode network; EEG = electroencephalogram; HF = hippocampal formation; IC = insular cortex; L = left; R = right; PCC = posterior cingulate cortex; PSG = polysomnography; SN = salience network; VPMC = ventromedial prefrontal cortex.

REPORT OF CASE

A retrospective analysis7 of clinical and polysomnographic findings of patients diagnosed with NREM parasomnia at a large tertiary sleep center incidentally revealed three distinct cases of Cotard delusions (Table 1) occurring paroxysmally, subsequent to confusional slow-wave arousal. Further comprehensive review of these cases was undertaken following appropriate approval from the institutional review board on human research (Project No. 10155, Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, National Health Service, UK).

Manual sleep staging and confusional slow-wave–arousals marking was performed by two independent sleep experts according to criteria by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) Visual Scoring Task Force.8 The latency to NREM sleep stage N1 was measured until the occurrence of 30.0 seconds of consecutive N1 sleep. A rapid eye movement period was defined as lasting a minimum of 240.0 seconds, with a minimum duration of 60.0 seconds between REM periods. A slow-wave–sleep (SWS, or N3) period was also defined as lasting a minimum of 240.0 seconds, with a minimum duration of 60.0 seconds between SWS periods.

The event-related Advanced Source Analysis (ASA) program (ANT Software, Enschede, The Netherlands) and a standard realistic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) head model9 were used, as previously described by Pascual-Marqui10 and Dale and colleagues (2000),11 for selection and exploratory analysis of post-arousals–electroencephalogram (EEG) patterns9 (Figure 1B). A fiducial marker system was used for localization of EEG electrodes, which were defined by marker points and registered by automatic localization and labeling of EEG sensors in the MRI volume, as previously described.10 For electrical source analysis and the current density estimation with standardized low resolution electromagnetic tomography (sLORETA),10,11 time windows analysis ran for 10 seconds starting from the end of a cortical arousal, with no filtering.

Case 1

A 59-year-old right-handed woman was seen in the sleep clinic with the main complaint of nocturnal paroxysmal episodes of nihilistic delusions that started several years ago, and that, with time, significantly impacted her self-perception and mood. She described waking up during the night with profound hypocenesthopathy,4 manifesting as a distinct feeling that “everything has drained” from her body, along with a nihilistic delusion that she was dead, or with profound ideas of damnation and dying. The event could last for up to a minute, and, at times, it led to a subsequent elaborate panic attack, during which she required prolonged reassurance that she was still alive. Parasomnic episodes occurred on average once or twice per month, sometimes in clusters over several nights in a row. Her husband noted that they commonly occurred within the first 2 hours of falling asleep. The patient was able to recall her thoughts and perceptions during the events but reported feeling uncomfortable and embarrassed relating them (see Table 1). No other sleep pathology was reported or elicited. Her Epworth Sleepiness Scale score (ESS = 5) and laboratory examinations were unremarkable. There was no relevant neurodevelopmental or neurologic history of note. However, the patient did have a psychiatric history of a comorbid bipolar affective disorder with mild cognitive deficits, which was in prolonged remission under the treatment regimen of olanzapine 2.5 mg and lithium 1 g daily. An overnight polysomnography demonstrated confusional arousals. In addition, a moderate degree of supine obstructive sleep apnea with 24.9 events/h was recorded, with the most significant desaturations seen within supine REM. The overall arousal index was reported as slightly elevated at 21.8 events/h secondary to respiratory events (10.3 events/h) and spontaneous arousals (Figure 1B and 1C: see C.1; 9.6 events/h). The frequency of experienced nihilistic delusions significantly decreased following initiation of concomitant treatment with melatonin and PAP therapy for her sleep-disordered breathing.

Case 2

A 33-year-old right-handed man was initially referred by his general practitioner due to a 2-year history of nocturnal paroxysmal awakenings with gasping for air, infrequently followed by panic attacks and associated sleep disruption. The patient’s daily functioning and quality of life significantly suffered from increasing fatigue (ESS score = 9) compounded by his inability to identify, and hence avoid, any specific triggers. The typical paroxysmal event, consisting of profound alexisomia (eg, difficulty in experiencing and expressing bodily feelings) and acenesthopathy,4 was reported to last several tens of seconds, during which the patient experienced an overpowering nihilistic belief that he was dead. The notion that his existence was no more was accompanied with an intense compulsion “to reoccupy his body,” leading him to use painful tactile stimuli, such as pinching, to check if his body was still there. No other sleep pathology or relevant medical or family history was reported or elicited; his laboratory examinations were normal and he was otherwise euthymic and physically well. The patient’s confusional arousals were caught (Figure 1B and 1C: see C.2) during overnight video polysomnography (Table 1), which demonstrated a normal sleep architecture and sleep efficiency of 93.2%. N3 sleep stage was reported as moderately elevated at 32.8% of total sleep time. Additionally, elevated periodic limb movements (PLMs) were recorded (29 times per hour), which did not appear to contribute to sleep fragmentation. A partial improvement was achieved on therapy with melatonin and further referral for an in-house cognitive behavioral therapy for parasomnia was arranged.

Case 3

A 35-year-old right-handed man with a mild learning disability was referred due to nocturnal awakenings with rather unusual sequelae of hypocenesthopathy, paracenesthopathy4, and alexisomia in the background of sensory parasomnia with depersonalization and derealization. These parasomnic events occurred every other month following a complicated episode of unconfirmed swine flu. They could last up to several minutes, following which he would suddenly regain awareness, sit up, and ask what had happened. No specific triggers were identified, and his family described witnessing him during these events as lying in bed with a pale, ashen complexion, without diaphoresis, feeling cold to the touch, not speaking, unresponsive but with eyes open. The patient himself described how, upon awakening, he would suddenly feel as if he was levitating above his body, which he then visualized from above looking inorganic and “empty,” as if about to “turn into a large lump of sugar.” At other times, he would awake to an existence reduced to a “pair of hands and my head,” the rest of his body conspicuous only by its absence. There was no attached concomitant emotional processing to this, only a pure perception of aberration, and a panic would ensue in a minute or so when the realization would sink in. A strong sense of suffocation sometimes accompanied this. Relating his intensive experiences caused anxiety, and, along with significant associated daytime somnolence (ESS score = 16), contributed to his overwhelming sense of social isolation. No other prior sleep pathology was reported, and in his neurodevelopmental history only a minor delay in reading and writing was reported. His comorbidities included a chronic migraine, ankylosing spondylitis, and gout that were all reasonably controlled on respective polytherapy of topiramate, sumatriptan, allopurinol, lisinopril, mometasone, and venlafaxine. His laboratory examinations and previous neuroimaging were unremarkable, and overnight polysomnography demonstrated confusional arousals (Table 1; Figure 1B and 1C: see C.3) in the background of a normal sleep architecture with mild REM-associated obstructive sleep apnea and raised PLM index of 27.8 events/h. PLMs were noted as significantly contributing to his arousals, and for that reason a gradual tapering of venlafaxine was proposed, and a treatment with a low dose of pregabalin and melatonin was initiated.

DISCUSSION

It is suggested that Cotard mentation at the parasomnic borderland of sleep-wake transitions is analogous to an aberrant state of consciousness in which attention is profoundly altered.3 Indeed, le délire des negations5 reported by our patients signal an intriguing possibility that at the sleep-wake dissociation an unstable antagonism between externally oriented cortical networks and internally oriented DMNs ensues3 (Figure 1A). The temporal evolution of the whole-brain–network states during sleep is far from understood, and while it has been suggested that the key transition from wake to sleep occurs via DMN, DMN’s role in REM sleep, or indeed in any other microstate of sleep, is even less clear. The source analysis of electroencephalographic fingerprint of confusional arousals in the three cases of Cotard parasomnia presented here demonstrated distinct spatiotemporal state transition (Figure 1B, Table 1) from arousal to an incomplete, predominantly unilateral (dominant) activation of the salience intrinsic network (SN) and its nodes, including the anterior insular and dorsal anterior cingulate cortices,3 to subsequent bilateral activation of fronto-parietal and other regions of DMN. Arguably, an abrupt and violent disruption (eg, apneic/hypopneic event or PLM) of the inherent brain bistability during NREM, when the brain’s capacity for information integration is further reduced, requires activation of self-monitoring networks (eg, SN) to assess the status operandi and to account for any immediate danger, before transition to DMN and, presumably, the possibility of further sleep (Figure 1A). The SN, with key nodes in the insular cortices, has a central role in the integration of visceral and autonomic stimuli, and in monitoring of the homeostatic functions of the brain and subsequent coordination of neural resources.12 The atypical engagement of specific subdivisions of the insula within the salience network is a feature of many neuropsychiatric and sleep disorders,12 and the asymmetrical right hypoactivation in our patients (Figure 1B: C.1–3) by and large mimics previous reports of right hemispheric damage or right insular hypometabolism in cases of Cotard syndrome.6 For example, the course of migraine, cluster headache, subarachnoid hemorrhage, post-ictal states, Parkinson disorder, dementias, and right hemispheric lesions caused by cerebral infarction, brain tumor, arteriovenous malformations, or intracranial hemorrhage have all been reported previously in association with Cotard delusion.5,6 Similarly, it has also been suggested that the right, rather than left, medial fronto-insular cortex acts as a main switch between major intrinsic networks by engaging the brain’s attentional, working memory and higher-order control processes while disengaging irrelevant systems.6

Our patients experienced distinct disturbing hallucinations of acenesthopathy, hypocenesthopathy, and paracenesthopathy4 with a profound effect on the individual experience of the body and selfhood. Given the central roles of cingulate and insular cortices and the SN in experience of self-related signals and their association to the experience of body ownership, it is postulated that an aberrant activation of the SN (Figure 1B: see C.1–3) and subsequent erroneous processing from internal autonomic neural substrates lead to their nihilistic mismatched interoception that begets anxiety and leads to further pavor nocturnus and panic attacks.1–3,6 The historical two-factor theory of delusions posits that delusional formation requires rationalizations of (1) anomalous experiences via (2) abnormal reasoning strategies.6 In keeping with this theory, in two of our cases mild cognitive deficits had been recorded (Table 1). However, we suggest that the specific neurochemical and neuroanatomical milieu of sleep-wake dissociation in which Cotard parasomnia occurs provides a sufficiently disconnected fronto-temporo-parietal platform on which such profoundly anomalous experiences may be aberrantly linked to a loss of self. Hence, we suggest that such anomalous processing of interoceptive stimulus during a parasomnic event, along with abnormal handling of emotions at the level of limbic cortex, and disruptions in belief evaluation and error correction, underlies the rich tapestry of reported mentations and phenomenologies (for example see Table 1). Finally, while our retrospective analysis revealed only three cases of Cotard parasomnia, we believe such cases to be more frequent, and their pathology is likely central to many complex confusional arousals. Alexithymia, dysmorphophobia, and abnormal pain processing have been linked with Cotard syndrome, along with problems identifying and describing one’s own emotions, something which has been noted in our patients, and which likely contributes significantly to the underreporting of this parasomnic mentation.5

In conclusion, there are many limitations to the case series presented, notwithstanding its retrospective nature, lack of controls, and significant technical limitations of performing the source analyses on the limited EEG data collected during standard clinical polysomnographic recordings. Nonetheless, our findings suggest a novel, system-wide hypothesis for the patterns of brain activity that are associated with confusional arousals and Cotard parasomnia, which should inform future more sophisticated magnetoencephalography or functional neuroimaging and high density EEG investigations of parasomnias and their mentation. Given the striking nature of Cotard phenomenology and the inherent increasing risks that might be associated with experiencing and rationalizing profound existential aberrations, we recommend that sleep clinicians consider this syndrome in complex cases of refractory NREM parasomnia.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

All authors approved the last draft of this manuscript. All authors were involved in reviewing and drafting of the manuscript. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Author contributions: VG, SH, AN, DW, and IR designed and conducted the study. VG, SH, and IR analyzed the data.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AASM

American Academy of Sleep Medicine

- ACC

anterior cingulate cortex

- DMN

default mode network

- EEG

electroencephalogram

- ESS

Epworth Sleepiness Scale

- HF

hippocampal formation

- IC

insular cortex

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- NREM

non–rapid eye movement sleep stage

- OSA

obstructive sleep apnea

- PCC

posterior cingulate cortex

- PLM

periodic limb movement

- PSG

polysomnography

- sLORETA

standardized low-resolution electromagnetic tomography

- SN

salience network

- SWS

slow-wave sleep

- VPMC

ventromedial prefrontal cortex.

REFERENCES

- 1.Terzaghi M, Sartori I, Tassi L, et al. Evidence of dissociated arousal states during NREM parasomnia from an intracerebral neurophysiological study. Sleep. 2009;32(3):409–412. 10.1093/sleep/32.3.409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oudiette D, Leu S, Pottier M, Buzare MA, Brion A, Arnulf I. Dreamlike mentations during sleepwalking and sleep terrors in adults. Sleep. 2009;32(12):1621–1627. 10.1093/sleep/32.12.1621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nir Y, Tononi G. Dreaming and the brain: from phenomenology to neurophysiology. Trends Cog Sci. 2010;14(2):88–100. 10.1016/j.tics.2009.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jardri R, Cachia A, Thomas P, Pins D, eds. The neuroscience of hallucinations. New York: Springer; 2013. 10.1007/978-1-4614-4121-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chatterjee SS, Mitra S. “I do not exist”-Cotard syndrome in insular cortex atrophy. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;77(11):e52–e53. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Restrepo-Martínez M, Espinola-Nadurille M, Bayliss L, et al. FDG-PET in Cotard syndrome before and after treatment: can functional brain imaging support a two-factor hypothesis of nihilistic delusions? Cogn Neuropsychiatry. 2019;24(6):470–480. 10.1080/13546805.2019.1676710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drakatos P, Marples L, Muza R, et al. NREM parasomnias: a treatment approach based upon a retrospective case series of 512 patients. Sleep Med. 2019;53:181–188. 10.1016/j.sleep.2018.03.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berry RB, Budhiraja R, Gottlieb DJ, et al. Rules for scoring respiratory events in sleep: update of the 2007 AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events. Deliberations of the Sleep Apnea Definitions Task Force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J Clin Sleep Med. 2012;8(5):597–619. 10.5664/jcsm.2172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zanow F, Knosche TR. ASA–Advanced source analysis of continuous and event-related EEG/MEG signals. Brain Topogr. 2004;16(4):287–290. 10.1023/B:BRAT.0000032867.41555.d0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pascual-Marqui RD. Standardized low-resolution brain electromagnetic tomography (sLORETA): technical details. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol. 2002;24 (Suppl D):5–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dale AM, Liu AK, Fischl BR, et al. Dynamic statistical parametric mapping: combining fMRI and MEG for high-resolution imaging of cortical activity. Neuron. 2000;26(1):55–67. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)81138-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khazaie H, Veronese M, Noori K, et al. Functional reorganization in obstructive sleep apnoea and insomnia: A systematic review of the resting-state fMRI. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017;77:219–231. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.03.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]