ABSTRACT

Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy is a debilitating toxicity that adversely affects patient quality and course of treatment. Recent findings have demonstrated that the etiology of peripheral neuropathy is dependent on transporter-mediated accumulation in dorsal root ganglia, and targeting this mechanism can afford neurological protection without compromising therapeutic efficacy.

KEYWORDS: Chemotherapy, paclitaxel, oxaliplatin, peripheral neuropathy, solute carriers

Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) is a debilitating and dose-limiting toxicity that occurs in up to 80% of patients receiving the tubulin poison paclitaxel or platinum-based agent oxaliplatin. Clinical manifestations of this adverse effect include paresthesia, allodynia and sensory ataxia that occurs during the course of treatment; however, patients can continue to experience symptoms of CIPN years after the cessation of therapy. To date, the therapeutic management of CIPN is predominantly focused on two principal strategies: 1) a prophylactic approach targeting an intracellular mechanism contributing to the pathophysiology of CIPN, or 2) the treatment of CIPN symptoms themselves. These strategies have yielded an extensive number of clinical trials aimed to prevent and manage CIPN, though none of these trials have provided conclusive evidence for a clinically beneficially agent. Moreover, the successful identification of a clinically beneficial agent is hampered due to the recognition that targeting one of the many pleiotropic signaling pathways that lead to CIPN is insufficient and only provides partial neuroprotection, and/or the potential liability of the investigating agent in targeting an overlapping cell death signaling pathway between normal and cancer cells that negatively affects cancer treatment.1 Thus, the identification of novel preventative strategies to mitigate this debilitating side effect is urgently needed.

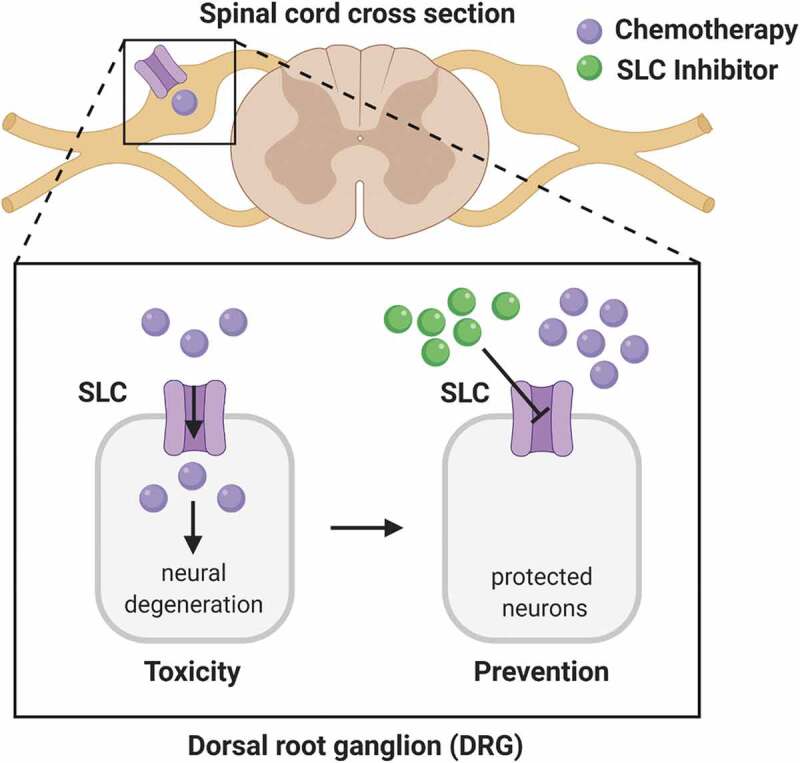

CIPN is hypothesized to originate from extensive exposure of sensory neurons found within the spinal cord and sciatic nerves to the chemotherapeutic insult, a dissemination and distribution pattern that is dependent on the transport of these agents from systemic circulation into neuronal cells. Its tissue-specific distribution pattern is also highlighted by high levels of paclitaxel and oxaliplatin observed in dorsal root ganglia (DRGs). Recent preclinical studies have identified that the solute carrier (SLC) family of organic anion transporting polypeptides (OATPs) and organic cation transporters (OCTs) are responsible for the accumulation of these agents into DRGs, preceding the downstream pathophysiological damage to sensory neurons2,3 More specifically, these studies demonstrated that the genetic deletion of organic anion transporting polypeptide 1B2 (Oatp1b2) (organic anion transporting polypeptide 1B1 [OATP1B1] in humans) and organic cation transporter 2 (Oct2) afforded neuroprotection against both acute and chronic forms of paclitaxel and oxaliplatin-induced neurological injury, respectively (Figure 1). Moreover, this protective phenotype could be recapitulated using pharmacological inhibitors that target the function of Oatp1b2 and Oct2 without concurrent alterations in target expression or pharmacokinetics that would otherwise influence susceptibility to injury. The use of heterologous overexpression models also reveals that the plasma levels of these transport inhibitors required to diminish the function of murine and human homologs can be clinically achieved in cancer patients. Additionally, neither paclitaxel nor oxaliplatin antitumor properties are sensitive to OATP and OCT-mediated inhibition in preclinical models of breast and colorectal cancers, while simultaneously affording neuronal protection.

Figure 1.

Chemotherapy-induced injury to the peripheral nervous system. Solute carriers (SLC) mediate the intracellular accumulation of chemotherapeutic agents, leading to peripheral neuropathy and neural degeneration (toxicity). These effects can be blocked by the SLC inhibitor (prevention)

Presently, duloxetine, a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, is a promising candidate in Phase III trials that is shown to be efficacious for the treatment of various neuropathic pain, including chemotherapy-induced neuropathies. Recent interest has revolved around investigating duloxetine’s as a preventative strategy. Although the mechanistic basis of its preventative properties remains unclear, several reports have highlighted its inhibitory properties against organic cation transport systems.3,4 These hypothetical observations are in alignment with the notion of duloxetine’s unintentional targeting of a transporter-dependent neuronal uptake mechanism.

The translational approach of targeting the transmembrane transport mechanisms responsible for the initiation of CIPN is currently being explored as clinical intervention strategies in breast and colorectal cancer patients receiving paclitaxel or oxaliplatin, respectively (NCT04205903 and NCT04164069). Current ongoing Phase 1B dose-escalation studies are designed to utilize systemic biomarkers as an endogenous pharmacodynamic marker of transport function. While this targeted approach has been investigated for cisplatin-related toxicities,5 the success of such an intervention strategy is dependent on the identification of endogenous substrates in systemic circulation and DRG tissues that are altered to reflect the function of OATP1B1 and OCT2. Secondly, the design also focuses on identifying an optimal dose and scheduling interval of the transport inhibitor to achieve temporary inhibition without simultaneously influencing the plasma levels of the chemotherapeutic drug in order to retain safety and efficacy. Coproporphyrins and bile acids, and creatinine and n-methylnicotinamide have recently been recognized as endogenous systemic biomarkers to predict the predilection for hepatic- or renal-mediated drug–drug interactions.6 However, it is unknown whether the changes in these biomarkers will also reflect the diminished function of these transporters in organs outside of excretory pathways, such as the DRGs. Due to the prospective overlap in inhibitory properties, it is also uncertain whether these changes are a concurrent measure of unintended inhibition of vectorial-related efflux transporters, such as the ATP-binding cassette or multidrug and toxin extrusion proteins. In order to delineate the contribution of these mechanisms, current efforts are focused on using the advent of metabolomics approaches in transporter-deficient mouse models to identify changes at both plasma level and DRG tissue. For example, since OATPs and OCTs are basolateral uptake transporters, plasma levels of endogenous substrates would be elevated while its intracellular concentration would be decreased. Follow-up studies would be conducted to recapitulate the findings observed in transporter-deficient mice in the presence or absence of a pre-treatment with a specific transport inhibitor. The identified marker would also be validated using low throughput targeted transport kinetic studies to establish translational potential in humans. These studies will also provide additional insights into these markers as regulators essential for neuronal development and homeostasis.

Taken together, recent advancement from preclinical studies had shed important light on targeting drug transporters as a novel neuroprotection strategy against both acute and chronic forms of paclitaxel and oxaliplatin-induced neurological injury. Further mechanistic studies using transcriptomic and metabolomics approaches would help guide the further clinical development of these novel treatment strategies to prevent chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy.

Funding Statement

This review is supported in part by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health [R01CA238946]; The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center using Pelotonia funds.

References

- 1.Hu S, Huang KM, Adams EJ, Loprinzi CL, Lustberg MB.. Recent developments of novel pharmacologic therapeutics for prevention of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(21):1–2. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leblanc AF, Sprowl JA, Alberti P, Chiorazzi A, Arnold WD, Gibson AA, Hong KW, Pioso MS, Chen M, Huang KM, et al. Oatp1b2 deficiency protects against paclitaxel-induced neurotoxicity. J Clin Invest. 2018;128(2):816–825. doi: 10.1172/JCI96160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang KM, Leblanc AF, Uddin ME, Kim JY, Chen M, Eisenmann ED, Gibson AA, Li Y, Hong KW, DiGiacomo D, et al. Neuronal uptake transporters contribute to oxaliplatin neurotoxicity in mice. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(9):4601–4606. doi: 10.1172/JCI136796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hacker K, Maas R, Kornhuber J, Fromm MF, Zolk O.. Substrate-dependent inhibition of the human organic cation transporter oct2: A comparison of metformin with experimental substrates. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0136451. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fox E, Levin K, Zhu Y, Segers B, Balamuth N, Womer R, Bagatell R, Balis F. Pantoprazole, an inhibitor of the organic cation transporter 2, does not ameliorate cisplatin-related ototoxicity or nephrotoxicity in children and adolescents with newly diagnosed osteosarcoma treated with methotrexate, doxorubicin, and cisplatin. Oncologist. 2018;23(7):762–e779. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chu X, Chan GH, Evers R. Identification of endogenous biomarkers to predict the propensity of drug candidates to cause hepatic or renal transporter-mediated drug-drug interactions. J Pharm Sci. 2017;106(9):2357–2367. doi: 10.1016/j.xphs.2017.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]