Abstract

Study Objectives:

The purpose of this study is to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating the effects of respiratory muscle therapy (ie, oropharyngeal exercises, speech therapy, breathing exercises, wind musical instruments) compared with control therapy or no treatment in improving apnea-hypopnea index ([AHI] primary outcome), sleepiness, and other polysomnographic outcomes for patients diagnosed with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).

Methods:

Only randomized controlled trials with a placebo therapy or no treatment searched using PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane, and Web of Science up to November 2018 were included, and assessment of risk of bias was completed using the Cochrane Handbook.

Results:

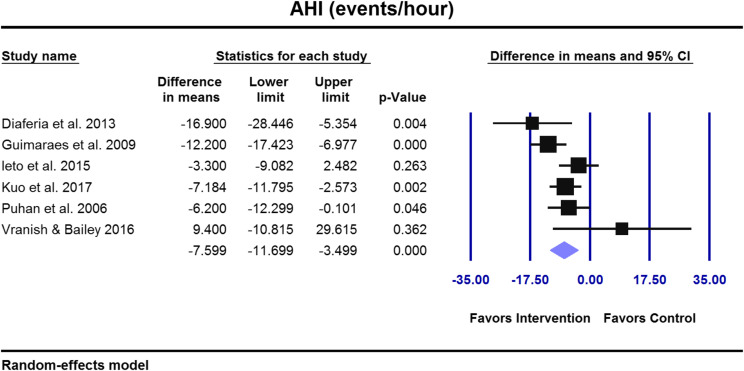

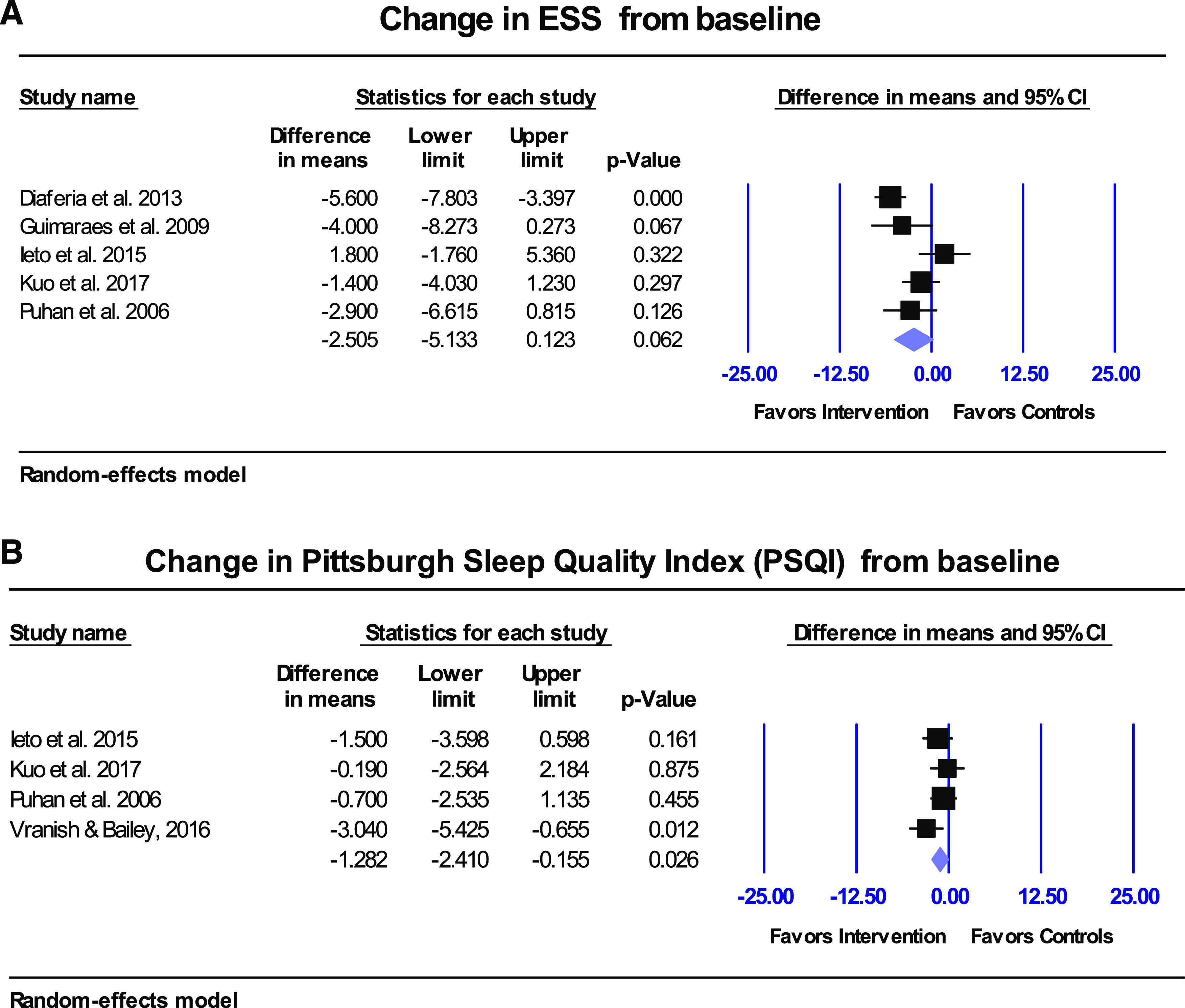

Nine studies with 394 adults and children diagnosed with mild to severe OSA were included, all assessed at high risk of bias. Eight of the 9 studies measured AHI and showed a weighted average overall AHI improvement of 39.5% versus baselines after respiratory muscle therapy. Based on our meta-analyses in adult studies, respiratory muscle therapy yielded an improvement in AHI of −7.6 events/h (95% confidence interval [CI] = −11.7 to −3.5; P ≤ .001), apnea index of −4.2 events/h (95% CI = −7.7 to −0.8; P ≤ .016), Epworth Sleepiness Scale of −2.5 of 24 (95% CI= −5.1 to −0.1; P ≤ .066), Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index of −1.3 of 21 (95% CI= −2.4 to −0.2; P ≤ .026), snoring frequency (P = .044) in intervention groups compared with controls.

Conclusions:

This systematic review highlights respiratory muscle therapy as an adjunct management for OSA but further studies are needed due to limitations including the nature and small number of studies, heterogeneity of the interventions, and high risk of bias with low quality of evidence.

Citation:

Hsu B, Emperumal CP, Grbach VX, Padilla M, Enciso R. Effects of respiratory muscle therapy on obstructive sleep apnea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Sleep Med. 2020;16(5):785–801.

Keywords: apnea-hypopnea index, breathing exercises, myofunctional therapy, obstructive sleep apnea, oropharyngeal exercises, respiratory muscle therapy, speech therapy

BRIEF SUMMARY

Current Knowledge/Study Rationale: Alternative methods of management for obstructive sleep apnea have long been sought by clinicians and researchers beyond the continuous positive airway pressure device, surgical interventions and/or mandibular advancement appliances. To this date, a systematic review has not been published summarizing the efficacy and effects of respiratory muscle therapy for obstructive sleep apnea based on only randomized controlled trials and encompassing both upper and lower airway muscles.

Study Impact: This review will help clinicians and researchers determine if such therapy can be included in a comprehensive program that can be implemented into routine clinical care to improve or manage obstructive sleep apnea.

INTRODUCTION

Although the sleep disorders field encompasses a multitude of various conditions, this review will focus on obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and the effects of respiratory muscle therapy. According to the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, third edition, “OSA is characterized by repetitive episodes of complete (apnea) or partial (hypopnea) upper airway obstruction occurring during sleep.” Apneic and hypopneic events can lead to a decrease in blood oxygen saturation and usually ends by short arousals from sleep.1 During sleep, reduced muscle tone, especially in the upper airways, influences breathing.2 The upper airway is a complex structure, involving the oropharyngeal muscles, dilator muscles, and tongue muscles, which can counteract any collapse in the airways caused by negative pressure during sleep.3 In fact one of the main mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of OSA is a decreased ability of the upper airway dilator muscles to maintain airway patency during sleep.4 In particular, the genioglossus muscle, one of the most important pharyngeal dilator muscles, protrudes the tongue, dilates the oropharynx, and prevents airway obstruction during sleep.5,6 It has been shown that patients without OSA have homogeneous anterior movement of the entire posterior tongue.7 Meanwhile patients with OSA have a more heterogeneous anterior movement of the tongue, resulting in part of the tongue moving posteriorly into the upper airway, which then effects other dilator muscles and lung volume.7

During normal respiration, caudal movement of the diaphragm produces increased lung volume and creates traction on the mediastinal structures. These lower airway muscle movements result in stiffening of the pharyngeal walls and stabilizes the patency of the upper airway. Meanwhile, during sleep there is a reduction in lung volume and decrease in upper airway dilator muscle tone. Thus upper and lower airway muscle function is relatively diminished during sleep and may potentiate airway obstruction.8 There are also circadian changes that increase the resistance in the lower airway, prompting the upper airway into obstructive apnea episodes.2 Therefore, although OSA is defined as an upper airway obstruction, it also involves the primary muscles of respiration (lower airway muscles) during inspiration, including the diaphragm, the external intercostals, and the expiration muscles such as abdominal muscles and internal intercostals.9

Management options of OSA include both conservative (continuous positive airway pressure [CPAP] device and/or mandibular advancement devices) and surgical intervention such as maxillomandibular advancement surgery.10 The gold standard for OSA in the United States remains the use of a CPAP machine. However, it has been reported that 59.2% of the patients discontinue use of this device either due to finances, not fitting the patient’s face, not believing in its efficacy, or eventually pursuing some sort of alternative treatment.11 In a prospective cohort study, authors reported that after 4 years about two-thirds of the patients did not use their device.12 There is increasing evidence that the pathogenesis of OSA involves more than just the anatomical factors of the airway.13 These include a neurochemical ventilatory control, imbalanced central respiratory motor output leading to an elevated loop gain, and the response of the chemoreceptor control system to a collapsible airway,13 which may explain some of the incomplete management of OSA treatment by conventional CPAP, mandibular advancement devices, or surgical modalities. The aim of respiratory muscle therapy includes improvement in the coordination of upper and lower airway muscles and increase airway patency during sleep. In addition, respiratory muscle therapy, if successful, would give patients a noninvasive option for management or improvement of their OSA. In this systematic review, the term respiratory muscle therapy will be used to incorporate both upper and lower airway muscle therapy, ranging from myofunctional/oropharyngeal exercises encompassing speech therapy and tongue exercises (upper airway muscles)14 to breathing exercises and wind musical instrument playing,15 which seems to have some efficacy on expiratory muscle training (lower airway muscles).16 One limitation of this systematic review is the fact that respiratory muscle therapy encompasses a variety of interventions. Although all these therapies exercise the airway muscles, it is unclear at this point how each of these therapies works or which one is the best option to treat OSA.

The objective of the current systematic review is to summarize the current relevant published randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on respiratory muscle therapy for the treatment of OSA. This review could be useful for the clinicians in their patient care and for the researchers to view the information at once and to identify areas that still need to be addressed in the respiratory muscle exercise regimen of OSA management.

METHODS

Study design

This systematic review adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement.17 The PICO (Patient, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome) question was, “In patients with OSA, is respiratory muscle therapy effective in improving OSA compared to controls or no treatment?”

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies in any age group were limited to randomized controlled clinical trials on the efficacy of respiratory muscle therapy compared with control therapy or no treatment. Respiratory muscle therapy is a technique of training respiratory muscles (inspiratory and/or expiratory, lower or upper airway) to improve respiratory function. Abstracts, pilot studies, letters to the editor, commentaries, literature reviews, systematic reviews, case reports, case series, nonrandomized clinical trials, animal studies, and clinical guidelines were excluded. Literature reviews, systematic reviews, and clinical guidelines were scanned for relevant RCTs. Articles not available in English were omitted.

Primary and secondary outcomes under study

Polysomnographic outcomes

The primary outcome was apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) measured during a sleep study in events per hour.18 Secondary polysomnographic outcomes included minimum and average oxygen saturation (SaO2 percent).

Sleepiness outcomes

Sleep efficiency is measured as the summation of sleep stage N1, stage N2, and stage N3 and rapid eye movement sleep divided by total bed time and is denoted in percentage.18 Epworth sleepiness scale (ESS) measures daytime sleepiness and has a total of 24 points. Any measurement above 10 is considered as above normal and may warrant treatment.19 The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) measures sleep quality on a scale of 0–21. The lower the number, the better the quality of sleep.20

Secondary outcomes

Snoring mostly occurs during inhalation, and, sometimes, exhalation. Primary snoring occurs in absence of OSA or associated symptoms.18 Snoring parameters, intensity, and frequency are measured on various scales of 0–3, 0–4, and 0–10.14,21,22 Included studies also reported body mass index (BMI), a measure of the body fat, expressed in kilograms per square meter, neck circumference (expressed in inches), and abdominal circumference, also expressed in inches.

Search methods for identification of studies

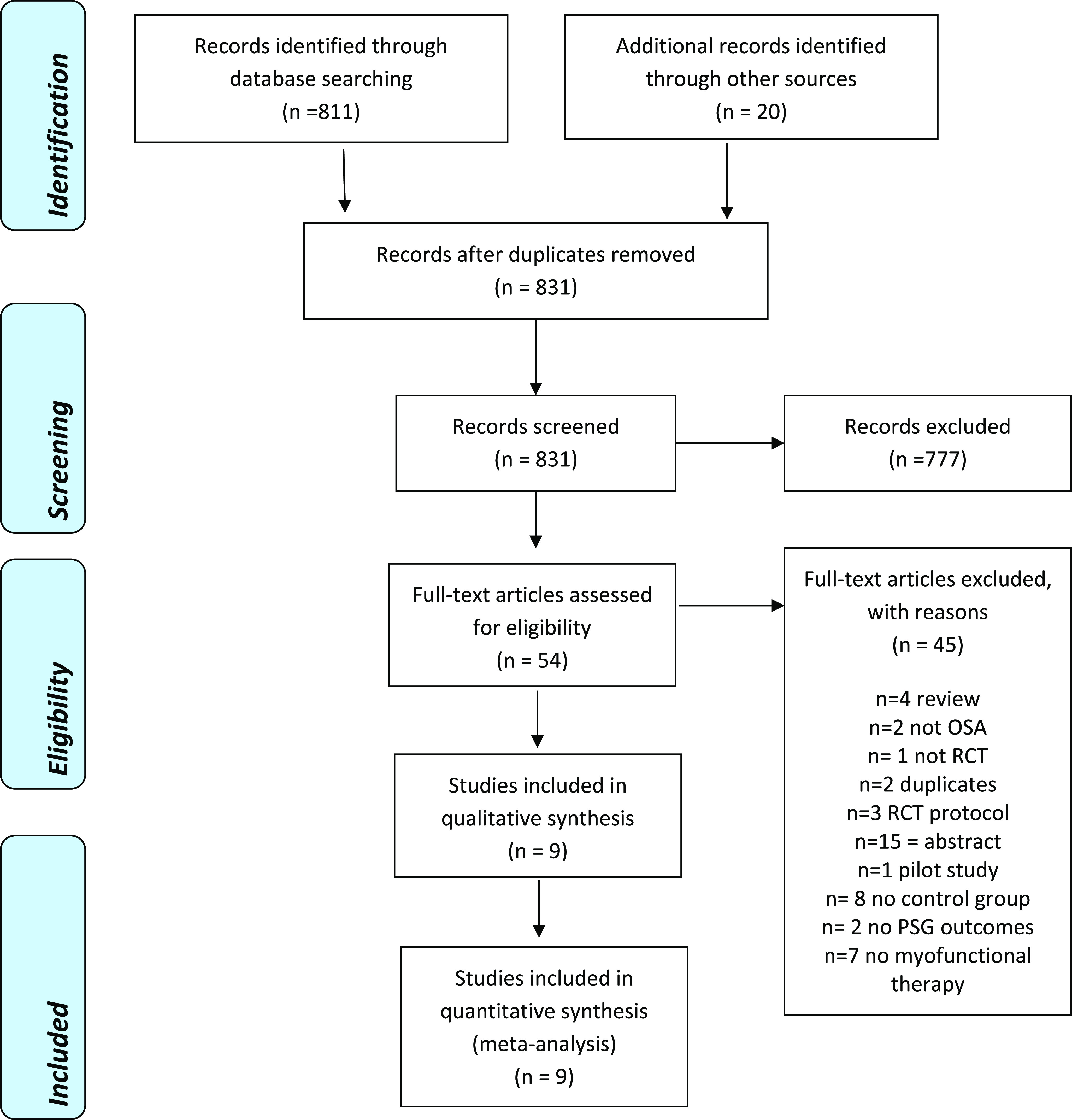

Four electronic databases (Medline via PubMed, Web of Science, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library) were searched up to November 21, 2018 (Table 1). A summary of our search results is shown in Figure 1 with the final list of included studies shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Electronic database search strategies.

| Electronic Database | Search Strategy |

|---|---|

| MEDLINE via PubMed (searched up to 11/15/2018) search strategy: | (orofacial myotherapy OR oral myotherapy OR tongue-muscle training OR oropharyngeal exercise* OR swallow* exercise* OR myofascial exercise* OR myofunctional therapy OR tongue exercise* OR tongue training OR genioglossus exercise* OR pharyngeal exercise* OR breathing exercise* OR inspiratory muscle OR expiratory muscle OR respiratory exercise OR speech therapy OR musical OR didgeridoo) AND (apnea OR apnea OR OSA OR snoring OR sleep-disordered breathing) |

| Language: limit to English | |

| Species: limit to Humans | |

| Article types: limit to Clinical trial, meta-analysis, Randomized controlled trial, Review, Systematic reviews | |

| The Web of Science (searched up to 11/20/2018) | TOPIC: (tongue-muscle training OR oropharyngeal exercise* OR swallow* exercise* OR myofascial exercise* OR myofunctional therapy OR tongue exercise* OR tongue training OR genioglossus exercise* OR pharyngeal exercise* OR speech therapy OR respiratory muscle training OR inspiratory muscle training OR expiratory muscle training OR musical OR didgeridoo) AND TOPIC: (apnea OR apnea OR snoring OR sleep-disordered breathing) |

| Filter: Language = English | |

| Filter: Article (166), review (22), proceedings paper (10), Book chapter (1) | |

| The Cochrane Library (searched up to 11/21/2018) | #1. (tongue-muscle training OR oropharyngeal exercise* OR swallow* exercise* OR myofascial exercise* OR myofunctional therapy OR tongue exercise* OR tongue training OR genioglossus exercise* OR pharyngeal exercise* OR speech therapy OR respiratory muscle training OR inspiratory muscle training OR expiratory muscle training OR musical OR didgeridoo) |

| #2. (apnea OR apnea OR snoring OR sleep-disordered breathing) | |

| #3. #1 and #2 | |

| EMBASE (searched on up to 11/20/2018) | 1. 'tongue muscle' AND training OR (oropharyngeal AND exercise*) OR (swallow* AND exercise*) OR (myofascial AND exercise*) OR (myofunctional AND therapy) OR (genioglossus AND exercise*) OR (pharyngeal AND exercise*) OR (speech AND therapy) OR (respiratory AND muscle AND training) OR (inspiratory AND muscle AND training) OR (expiratory AND muscle AND training) OR didgeridoo |

| 2. apnea OR apnea | |

| 3. #1 and #2 combine | |

| 4. #3 AND ('article'/it OR 'article in press'/it OR 'conference paper'/it OR 'conference review'/it OR 'review'/it) AND [english]/lim | |

| Filters: English | |

| Publication types= 'article'/it OR 'article in press'/it OR 'conference paper'/it OR 'conference review'/it OR 'review'/it |

OSA = obstructive sleep apnea

Figure 1. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram.17.

Table 2.

Summary of eligible RCT studies.

| Study | Country, Study Type, Sample Size | Interventions and Sample Size per Group | Inclusion Criteria | Sex and Age | Number of Visits | Trained/Supervised By |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diaferia et al, 201325 | Brazil, Non blinded RCT n = 140 | 1. Myofunctional therapy (MT; speech therapy) n = 27 | 1. Patients diagnosed with OSA based on clinical and polysomnographic criteria independently of severity 2. All men between the ages of 25 to 65 years 3. Body mass index (BMI) < 35 kg/m2 |

140M/0F 48.1 ± 11.2 years |

3 (first week, first month, third month) | Supervised by trained staff of CPAP service |

| 2. CPAP group n = 27 | ||||||

| 3. Speech therapy + CPAP n = 22 | ||||||

| 4. Controls (sham speech therapy) n = 24 | ||||||

| Diaferia et al, 201722 | Brazil, Non blinded RCT n = 140 | 1. MT (speech therapy) n = 27 | 1. Consecutive men age 25 to 65 years 2. BMI < 35 kg/ m2 3. OSA diagnosis confirmed by clinical and polysomnographic criteria |

140M/0F 48.1 ± 11.2 years |

3 (first week, first month, third month) | Trained by speech pathologist and supervised by trained staff of CPAP service |

| 2. CPAP n = 27 | ||||||

| 3. CPAP + MT n = 22 | ||||||

| 4. Controls (Sham MT: exercises without therapeutic function, relaxation and stretching of the neck muscles), n = 24 | ||||||

| Guimaraes et al, 200914 | Brazil, Single blinded RCT n = 31 | 1. Oropharyngeal exercises n = 16 2. Controls (deep breathing) n = 15 |

1. Eligible patients between 25 and 65 years of age with a recent diagnosis of moderate OSAS evaluated in the sleep laboratory | 21M/10F Intervention group: 51.5 ± 6.8 years Controls: 47.7 ± 9.8 years |

Weekly visits for 3 months | Trained by speech pathologist |

| Ieto et al, 201521 | Brazil, Single blinded RCT n = 39 | 1. Oropharyngeal exercise Group n = 19 2. Controls (nasal dilator strips plus nasal lavage with deep breathing) n =20 |

1. Between 20 and 65 years of age 2. Primary complaint of snoring 3. Recent diagnosis of primary snoring or mild to moderate OSA. |

22M/17F 6.0 ± 13.0 years |

Weekly visits for 3 months | Supervised by the investigator who performed the sleep study |

| Kuo et al, 201716 | Taiwan, Non blinded RCT n = 25 | 1. Expiratory muscle strength training (EMST): Resistance pressure at 75% of each participant’s PE max n = 13. Controls 2. (Resistance pressure at 0% of each participant’s PE max) n = 12 | 1. Age 20–60 years 2. Current OSA (AHI > 5 events/h) |

21M/4F Intervention group: 44.3 ± 2.9 Controls: 48.0 ± 3.1 |

Not mentioned | EMST trainer |

| Puhan et al, 200627 | Switzerland, Single Blinded RCT n = 25 | 1. Didgeridoo n = 14 2. Controls (Waiting list – no treatment) n = 11 |

1. German speaking participants aged > 18 years 2. Self-reported snoring 3. AHI of 15–30 events/h. |

21M/4F Intervention group: 49.9 ± 6.7 Controls: 47 ± 8.9 |

3 visits | Didgeridoo instructor |

| Villa et al, 201526 | Italy, Single Blinded RCT n = 27 | 1. Oropharyngeal exercises plus nasal washing n = 14 2. Controls (nasal washing) n = 13 |

1. Children with clinical cutoff value of AHI > 5 events/h for moderate-severe OSA while residual OSA was defined as an AHI index > 1 events/h after AT 2. Persistence of respiratory symptoms (snoring, oral breathing, and sleep apnea). | 24M/3F 4.82 ± 1.36 years |

3 monthly meetings for 2 months | Myofunctional Therapist |

| Villa et al, 201724 | Italy, Non Blinded RCT n = 54 | 1. MT + nasal washing n = 36 2. Controls (nasal washing group) n = 18 |

1. Children referred to a pediatric sleep center for SDB 2. Diagnosis of OSA confirmed by the presence of SDB symptoms 3. PSG yielding an obstructive AHI > 1 event/h. |

22M/32F7 1 ± 2.5 years |

2 monthly meetings for 2 months | Myofunctional Therapist |

| Vranish & Bailey et al, 201628 | US, Single Blinded RCT n = 24 | 1. Inspiratory muscle strength training (75% of PI max) n = 12 2. Controls (15% of PI max) n = 12 |

1. Adults with mild, moderate, and severe OSA, who did not use or had discontinued using CPAP, dental devices, or other OSA-related therapies for at least 6 months prior to the study intake | 16M/8F Intervention group: 61.5 ± 3.9 years Controls:69.1 ± 3.4 years |

Not mentioned | Trained using inspiratory threshold training device |

AHI = apnea-hypopnea index, AT = adeno tonsillectomy, CPAP = continuous positive airway pressure, EMST = expiratory muscle strength training, F = female, M = male, OSA = obstructive sleep apnea, PE max = expiratory pressure, PI max = inspiratory pressure, RCT = randomized controlled trials, SDB = sleep-disordered breathing.

Selection of studies, data extraction, and management

Using the above mentioned search strategies, one author downloaded the titles and abstracts onto Mendeley Reference Manager software (R.E.) and 2 review authors (B.H. and C.E.) assessed the resultant records for inclusion/exclusion criteria. The references, which are based on title and abstract and met the inclusion criteria, were searched again and full articles were downloaded. Two review authors (B.H. and C.E.) assessed the references full-text for inclusion/exclusion independently, and the senior author (R.E.) reviewed the disagreements. Reasons for exclusion were recorded. A form was used to collect the characteristics of the participants, both treatment and control groups, and treatment provided with the outcomes reported. All literature reviews, systematic reviews, and included studies were cross-referenced in search of additional references.

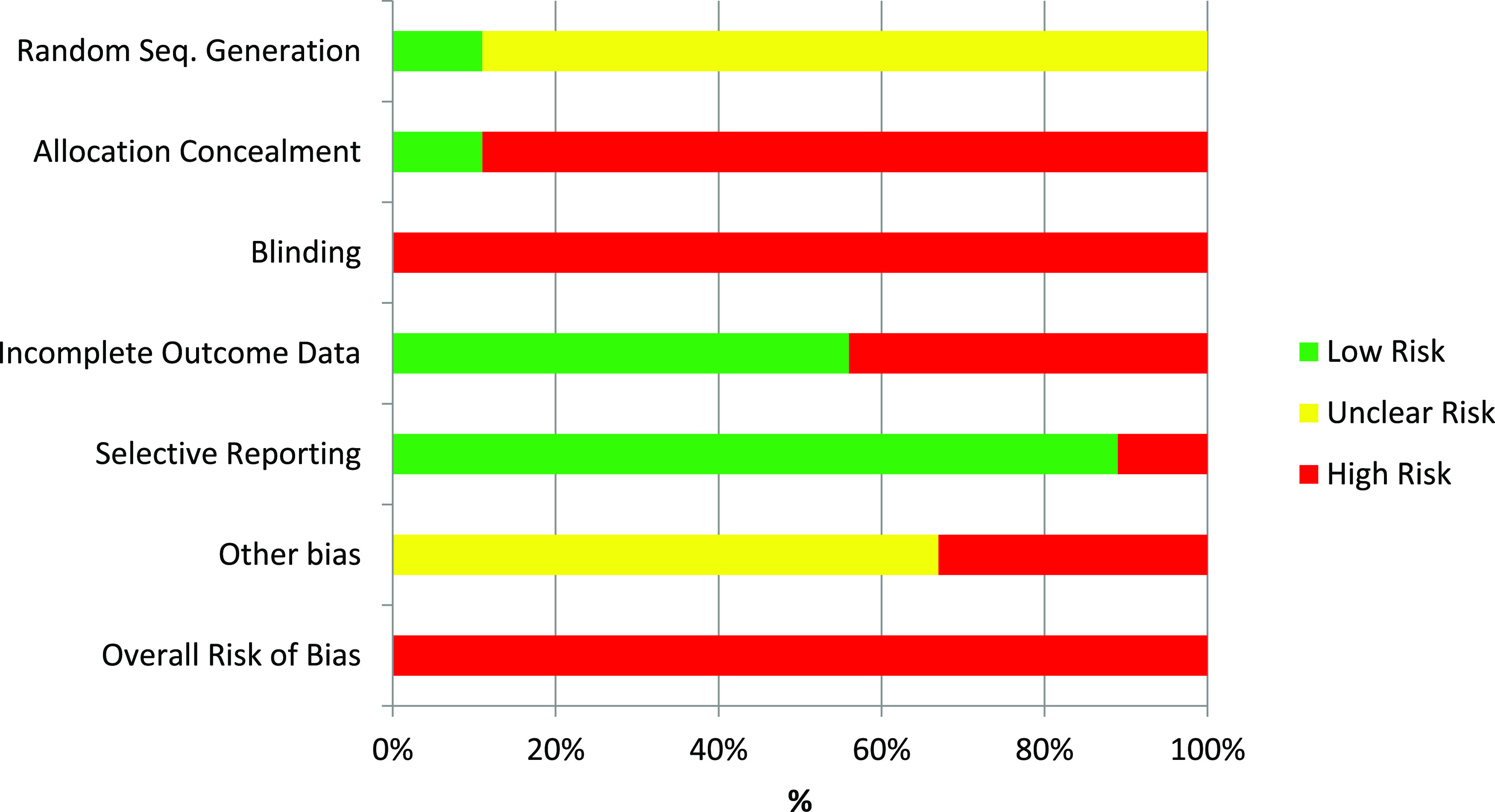

Assessment of risk of bias

The assessment of risk of bias in the included RCTs was undertaken independently by 2 authors (B.H. and C.E.) and reviewed by a third author (R.E.) in accordance with the approach described in Cochrane Handbook.23 A risk of bias graph was completed for this systematic review (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Summary of risk of bias of eligible randomized controlled trials.

Statistical analyses

Only RCT studies on patients with OSA comparing similar outcomes with similar interventions (respiratory exercises versus controls/no treatment) were included in the meta-analyses. Paired meta-analyses were conducted for continuous outcomes. Trial authors were contacted to retrieve missing data on AHI,14,16 and standard error of the mean percentage clarification.24 Mean and standard deviation (SD) were calculated from median and 25% quartile (q1) and 75% quartile (q3) as follows: mean = (q1 + median + q3) / 3; SD = (q3 − q1) / 1.35. Estimates of effect were combined using a random-effects model due to the heterogeneity of the interventions. Review authors calculated “estimates of effect” as mean differences of change in outcome from baseline for all outcomes with 95% CIs except snoring intensity and frequency. Authors of individual studies reported snoring frequency and snoring intensity with 3 different scales.14,21,22 Therefore, the standardized difference in means for snoring intensity and frequency was reported. Whenever possible, subgroup analyses were conducted for upper airway exercises,14,21,22,24–26 expiratory lower airway exercises,16,27 and inspiratory lower airway exercises.28

For outcomes such as AHI, where a favorable outcome is associated with a decrease in that variable, a favorable “estimate of effect” for the intervention will be negative, because a negative difference in mean change of AHI from baseline indicates a larger improvement in AHI in the intervention group than the control group. For outcomes where an improvement is associated with an increase, such as sleep efficiency, a favorable “estimate of effect” for the intervention will be positive. Statistical analyses were conducted with the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software version 2 (Biostat, Englewood, NJ).

Review authors also calculated the average percent change from baseline in AHI as (post – pre)/post, presented in Table 3. Authors also calculated with Excel software a weighted average and SD of the percent change in AHI with the weight of each study being the sample size.29

Table 3.

Baseline and posttreatment AHI.

| Study | OSA at Baseline |

Intervention Groups | Control Groups | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild OSA (AHI, 5–15 events/h); moderate OSA (AHI, 15–30 events/h); severe OSA (AHI > 30 events/h) | Baseline AHI, events/h | After TX, events/h | % Change in AHI | Baseline AHI, events/h | After TX, events/h | % Change in AHI | |

| Diaferia et al, 201325 and 201722 | 26% mild | 28.0 ± 22.7 | 13.9 ± 18.5 | −50.4 | 27.8 ± 20.3 | 30.6 ± 21.8 | 10.1 |

| 32% moderate | |||||||

| 42% severe | |||||||

| Guimaraes et al, 200914 | Moderate OSA | 22.4 ± 4.8 | 13.7 ± 8.5 | −38.8 | 22.4 ± 5.4 | 25.9 ± 8.5 | 15.6 |

| Ieto et al, 201521 | Mild to moderate OSA | 22.4 ± 4.89 | 19.2 ± 6.44 | −24.4% | 25.7 ± 5.7 | 22.8 ± 7.33 | −11.3 |

| Kuo et al, 201716 | Mild to moderate OSA | 16.5 ± 7.93 | 9.9 ± 3.56 | −50.0 | 14.6 ± 5.2 | 15.18 ± 3.15 | 4.0 |

| n = 14 mild | |||||||

| n = 11 moderate | |||||||

| Puhan et al, 200627 | Moderate OSA | 22.3 ± 5.0 | 11.6 ± 8.1 | −48.0 | 19.9 ± 4.7 | 15.4 ± 9.8 | −22.6 |

| Villa et al, 201526 | Pediatric participants: AHI > 5 events/h for moderate-severe OSA | 4.87 ± 2.96 | 1.84 ± 1.36 | −62.2 | 4.56 ± 3.22 | 4.11 ± 2.73 | −9.9 |

| Vranish & Bailey et al, 201628 | Mild to severe | 21.9 ± 4.4 | 26.4 ± 6.4 | 20.5 | 29.9 ± 8.9 | 25.0 ± 8.3 | −16.4 |

AHI at baseline and posttreatment reported by the included studies plus percent change in AHI (calculated by the authors). Data are shown as means ± standard deviation. AHI = apnea-hypopnea index, OSA = obstructive sleep apnea, TX = treatment.

Levels of evidence and summary of the review findings

The quality of evidence assessment and summary of the review findings were conducted with the software GRADE profiler (GRADEpro software [Evidence Prime Inc., Ontario, Canada]), following the Cochrane Collaboration and GRADE Working Group recommendations.23 In this systematic review, the sample size of the meta-analysis was deemed as insufficient (small sample size) if fewer than 400 participants were included in the meta-analysis,30 downgrading the quality of the evidence.

RESULTS

Results of the search

The electronic search strategy yielded 811 references plus 20 records found by cross-referencing the bibliography sections. Those 831 references were assessed independently by 2 review authors (B.H. and C.E.) and, based on the abstracts and titles, these were reduced to 54 records in need of full-text review and 777 records were excluded. All the 54 manuscripts identified were searched for full-text and analyzed for inclusion independently by the same 2 review authors. Nine manuscripts were relevant for inclusion.14,16,21,22,24–28 Main reasons for exclusion are described in PRISMA flowchart, which shows a summary of our results (Figure 1).

Included Studies

Five single blinded RCTs14,16,26–28 and 4 nonblinded RCTs21,22,24,25 were included in this systematic review (Table 2).

Population

A total of 394 patients was included in this review (Table 2). Patients had OSA diagnosed by clinical examination and confirmed by polysomnography (PSG), which included mild, moderate, and severe OSA. In the adult studies, the average AHI before intervention ranged from mild OSA (14.6 events/h)16 to severe OSA (30.9 events/h),22,25 whereas in the pediatric studies, the average AHI ranged from 2.2 ± 2.0 events/h24 to 4.7 ± 3.0 events/h26 (Table 3). Some of the patients included also had snoring as 1 of their chief complaints.21,24 All studies enrolled patients at only one center, both men and women, but there were more men than women in all studies. The number of participants in each study ranged from 2527 to 140 participants.22,25 All the studies had dropouts, except 1.27 The average (± SD) age of the patients varied from middle-aged (44.3 ± 2.9 years)16 to older adults (69.1 ± 3.4 years)28 in the adult studies and 4.82 ± 1.3626 to 7.1 ± 2.5 years24 in the pediatric studies. The inclusion criteria among the studies as well as the average age and sex distribution are presented in Table 2.

Intervention

In 6 studies, patients in the intervention group received oropharyngeal exercises (Table 4).14,21,22,24–26 Oropharyngeal exercises were performed to improve the muscle position, tension, and functions of the muscles of the oropharynx and the soft tissues surrounding it. In 2 of the studies, patients were randomized into groups of speech/myofunctional therapy, CPAP therapy, combination therapy, and sham speech therapy.22,25 Speech pathologists, myofunctional therapists, and didgeridoo instructors trained the participants in the therapy group and the number of visits varied in the 9 studies (Table 2). Respiratory muscle strength training was prescribed in 2 studies.16,28 Respiratory pressure was set at 75% of the participants’ maximal inspiratory pressure28 and 75% of the expiratory pressure.16 Playing didgeridoo to improve the oropharyngeal muscles was prescribed in one of the studies.27 These different modalities of respiratory muscle therapy are listed in Table 4 and were classified into upper airway exercises,14,21,22,24–26 expiratory lower airway exercises,16,27 and inspiratory lower airway exercises.28

Table 4.

Interventions in treatment and control groups.

| Study | Intervention Therapy | Details | Duration | Frequency | Control Therapy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diaferia et al, 201325 | Myofunctional therapy | Exercises of localized muscle resistance in the oropharyngeal area (soft palate, pharyngeal constrictor muscles, suprahyoid muscles, tip and root of the tongue, cheeks, and lips) | 3 mo | 20 minutes, 3 times per day. Exercise daily diary (new exercises every week) | Sham speech/myofunctional therapy (head movements without any therapeutic function) |

| Diaferia et al, 201722 | Myofunctional therapy | a. Soft palate exercises | 3 mo | a. 3 minutes, 3 times per day | Sham speech/myofunctional therapy (head movements without any therapeutic function) |

| b. Tongue brushing | b. 5 times, 3 times per day | ||||

| c. Tongue pushing and sucking | c. 20 times, 3 times per day | ||||

| d. Tongue rotation | d. 10 times on each side, 3 times per day | ||||

| e. Facial exercises | |||||

| e1. Pressing the buccinators muscle outward | e1. 10 times on each side, 3 times per day | ||||

| e2. Sucking air from a syringe | e2. 5 times, 3 times per day | ||||

| f. Stomatognathic functions | |||||

| f1. Breathing and speech including forced nasal inspiration and oral expiration in conjunction with phonation of open vowels | f1. During sitting | ||||

| f2. Balloon inflation with prolonged nasal inspiration and then forced blowing | f2. 5 times per day | ||||

| f3. Swallowing and chewing | f3. During eating | ||||

| Guimaraes et al, 200914 | Oropharyngeal exercises | a. Soft palate and tongue exercises | 3 mo | a. 3 minutes per day | Supervised session (30 min per week of deep breathing + nasal lavage with 10 ml of saline in each nostril 3 times per day. |

| b. Tongue brushing (superior and lateral surface) | b. Each movement 5 times, 3 times per day | ||||

| c. Closing the orbicularis oris | c. 30 seconds | ||||

| d. Mouth angle elevation | d. 10 intermittent elevations, 3 times per day | ||||

| e. Stomatognathic functions | e. Similar to Diaferia et al22 | ||||

| Ieto et al, 201521 | Nasal lavage three times a day followed by oropharyngeal exercises. | Oropharyngeal exercises: | 3 mo | 8-min set of exercises (20 times), 3 times a day for therapy and control | Nasal washing/lavage 3 × day + deep breathing exercises while sitting) |

| a. Pushing the tip of the tongue against the hard palate and slide the tongue backward | |||||

| b. Sucking the tongue upward against the palate, pressing the entire tongue against the palate | |||||

| c. Forcing the back of the tongue against the floor of the mouth | |||||

| d. Elevation of the soft palate and uvula | |||||

| e. Pressing the buccinators outward | |||||

| f. Alternate bilateral chewing and deglutition during eating | |||||

| Kuo et al, 201716 | Expiratory muscle training Resistance pressure at 75% of each participant’s PE max | Inhalation and exhalation with an interval of 30–60 s with 2-min break after each breathing cycle | 5 weeks | 5 days per week, 25 breaths per day, 5 breaths per cycle, 5 cycles per day | Expiratory muscle training (resistance pressure at 0% of each participant’s PE max) |

| Puhan et al, 200627 | Playing Didgeridoo and daily practice at home with standardized instruments | a. Week 1: Lip technique to produce and hold the keynote for 20–30 seconds. | 4 mo. | At least 20 minutes and at least 5 days per week | Waiting list (no treatment) |

| b. Week 2 and 3: Circular breathing technique | |||||

| c. Week 4: Optimization of the complex interaction between the lips, the vocal tract, and circular breathing | |||||

| d. 8 weeks later: Repetition of techniques and corrections | |||||

| Villa et al, 201526 and Villa et al, 201724 | Oropharyngeal exercises | a. Nasal breathing rehabilitation | 2 mo. | 10–20 repetitions, 3 times per day | Nasal washing/lavage 2 times per day |

| b. Labial seal and lip tone exercises | |||||

| c. Tongue posture exercises | |||||

| Vranish & Bailey, 201628 | Inspiratory muscle strength training (75% of PI max) | Inspiratory muscle strength training | 6 weeks | 30 breaths per day | Inspiratory muscle strength training (15% of PI max) |

PE max = expiratory pressure, PI max = inspiratory pressure.

Comparison group

Patients in the comparison groups were labeled as controls and received sham exercises, such as deep breathing with nasal lavages or dilator strips,21,24,26 or respiratory muscle training at 0% of the maximal expiratory pressure16 or 15% of the participant’s maximal inspiratory pressure.28 The controls in one of the studies did not have any treatment, but they were placed in the waiting list to receive training for playing the musical instrument.27 Deep breathing was prescribed to the controls in one of the studies.14 Sham speech therapy, just relaxing the cervical muscles without any therapeutic function, were prescribed to the controls in 2 studies.22,25

Outcomes

Primary outcomes measurements reported were AHI,14,16,21,22,25–28 apnea index (AI),14,22,25 minimum SaO2 percent,21,22,24,25,28 average SaO2 percent,22,24 ESS,14,16,21,22,25,27 sleep efficiency,14,21,22,28 PSQI,16,21,27,28 snoring frequency,14,21,22 snoring intensity,14,21,22 BMI,14,16,21,22,25–28 neck circumference,14,21,22,25,28 and abdominal circumference.14,21

Risk of bias in included studies

A summary of risk of bias graph (Figure 2) is presented in this review.

Random sequence generation

Random sequence generation bias was identified as low risk in one study27 because authors used a statistical software to generate the randomization list. The remaining 8 included studies14,16,21,22,24–26,28 identified as having unclear risk of bias because the authors reported the patients were randomized but did not provide any details on the method of randomization.

Allocation concealment

Allocation concealment was reported by one study27 and was at low risk of bias because they used a central telephone service for concealment. The allocation concealment strategy was not stated in 8 studies14,16,21,22,24–26,28 and they were scored as high risk.

Blinding

Risk of bias assessment for blinding was high in all the studies because they were not double blinded.14,16,21,22,24–28

Incomplete outcome data

Five trials included had no missing outcome data and were assessed as being at low risk of bias for this domain.14,16,21,27,28 Four studies were considered at high risk of bias due to large number of drop-outs or imbalanced reasons due to drop out related to the interventions or lack of intent-to-treat analysis.22,24–26

Selective reporting

All of the prespecified outcomes were reported in 8 studies.14,16,21,22,25–28 Only one study had high risk of bias in selective reporting due to reporting data on 18 of 36 of the patients in the therapy group.24

Other potential sources of bias

Six studies14,16,21,22,25,27 were considered at unclear risk of bias because cointerventions, such as exercise and supplements, were not mentioned and would be difficult to track. It would be possible for some of the placebo interventions for breathing to have a similar effect as some of the oropharyngeal exercises. In 3 studies there was high risk because groups at baseline were imbalanced24,26 or the placebo was a cointervention that actually produced a better AHI than the treatment group.28

Changes in AHI reported by the included studies

Average AHI (± SD) before and after treatment reported by the included studies is presented in Table 3 for intervention and control groups. Based on this data, review authors calculated the weighted average and SD of AHI percent improvement. The weighted average percent improvement on all 7 studies reporting AHI14,16,21,25–28 was −39.5% ± (SD) 25.4% in the intervention groups compared with −1.6% ± 13.9% in the control groups; for the adults, the average improvement in AHI in the intervention groups was −36.0% ± 25.6% compared with a −0.3% ± 15.3% in the control groups.14,16,21,25,27,28 Only 1 study28 showed a worsening of AHI. The weighted average percent improvement in 6 studies14,16,21,25,27 without that study28 was −44.6% ± 9.4% in the intervention groups compared with a 2.4% ± 14.9% in the control groups.

Results of the meta-analyses in pediatric population

Although 2 studies were included in this systematic review with pediatric populations, one study did not report AHI nor AI after the intervention.24 In the study where AHI was measured both before and after, there was a significant decrease in AHI from baseline in the intervention group by −2.6 events/h (95% CI −4.7 to −0.5; P = .016) compared with controls in one study in children.26 In a different study by the same author, it was found that there was a significant difference in the change in minimum SaO2% from baseline favorable to control group of −2.4% (95 CI = −4.6 to −0.2; P = .032) and no significant difference in the change in average SaO2% (P = .063).24 These results should be taken with caution as only one study reported AHI or minimum/average SaO2%. However, these studies could serve as motivation to conduct further research in the management of OSA in the pediatric population.

Results of the meta-analyses in adults

Forest plots for primary and secondary outcomes are presented in Figure 3, Figure 4, and Figure 5.

Figure 3. Overall AHI improved significantly in OSA adults receiving respiratory muscle therapy compared with controls (P < .001).

AHI = apnea-hypopnea index, CI = confidence interval, OSA = obstructive sleep apnea.

Figure 4. Sleepiness outcomes in adult studies.

(A) Overall ESS index improved but not statistically significantly (P = .062) in OSA adults receiving respiratory muscle therapy (improvement in sleepiness is demonstrated by a lower ESS). (B) Overall PSQI index improved significantly in OSA adults receiving respiratory muscle therapy (P = .026). Improvement in sleep quality was demonstrated by lower PSQI scores. CI = confidence interval, ESS = Epworth Sleepiness Scale, OSA = obstructive sleep apnea, PSQI = Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index.

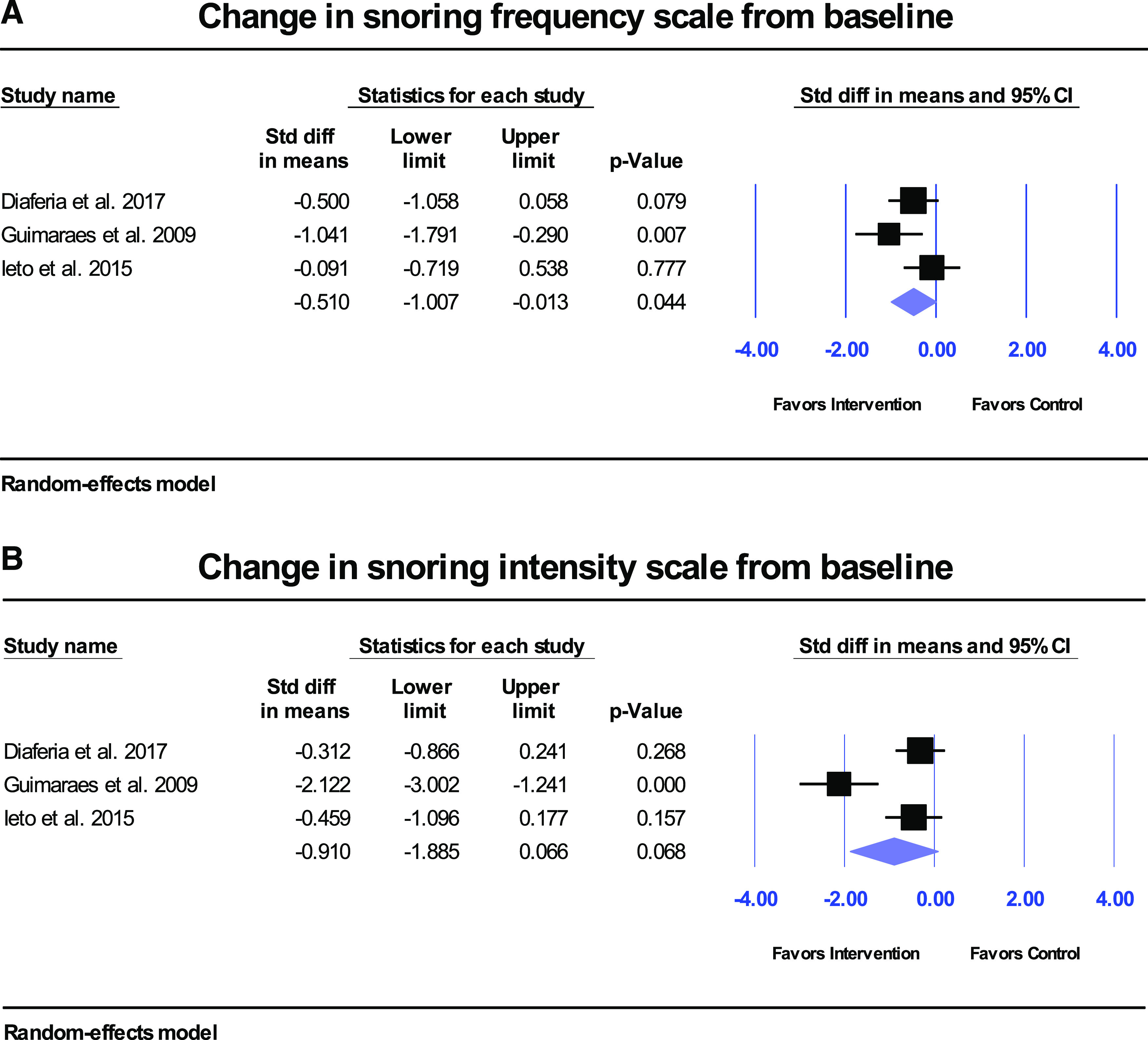

Figure 5. Snoring frequency and intensity outcomes in adult studies.

Overall snoring frequency (A) improved significantly compared with controls (P = .044), but not snoring intensity (B) (P = .068).

Adverse effects

To our knowledge, there are no known adverse complications of respiratory exercises in the management of OSA and they seem to be safe.27 One study mentioned that there were very few side effects; however, the authors did not provide any details on these “side effects”.26 Eight of the 9 RCTs in our systematic review had not mentioned any adverse side effects.

Summary of the evidence and quality of the findings (GRADE)

According to the GRADE table, the quality of the evidence was low for all outcomes due to high risk of bias of the included studies and small total sample size less than 400 participants with small number of studies (Table 5); low evidence grading indicates that further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and it is likely to change the estimate.

Table 5.

Summary of the evidence and quality of the findings (GRADE).

| Respiratory Muscle Therapy Compared with Control Therapy for OSA | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | No of Participants (studies) Follow up | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Anticipated absolute effects |

| Risk difference with Respiratory Muscle Therapy (95% CI) | |||

| Change in AHI from baseline events/h | 201 (6 studies) 2–3 months | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b due to risk of bias, imprecision | The mean change in AHI from baseline in the intervention groups was 7.6 events/h lower (11.7 to 3.5 lower) |

| Change in ESS from baseline | 171 (5 studies) 2–3 months | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b due to risk of bias, imprecision | The mean change in ESS from baseline in the intervention groups was 2.5 lower (5.1 lower to 0.1 higher) |

| Change in PSQI from baseline Scale from: 0 to 5. | 113 (4 studies) 2–3 months | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b due to risk of bias, imprecision | The mean change in PSQI from baseline in the intervention groups was 1.282 lower (2.4 lower to 0.2 higher) |

| Change in apnea index from baseline events/h | 82 (2 studies) 2-3 months | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b due to risk of bias, imprecision | The mean change in apnea index from baseline in the intervention groups was 4.2 events/h lower (7.7 lower to 0.8 higher) |

| Change in minimum SaO2% from baseline | 82 (3 studies) 2–3 months | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b due to risk of bias, imprecision | The mean change in minimum SaO2% from baseline in the intervention groups was 0.02 lower (3.1 lower to 3.0 higher) |

| Change in sleep efficiency (%) from baseline | 145 (4 studies) 2–3 months | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b due to risk of bias, imprecision | The mean change in sleep efficiency (%) from baseline in the intervention groups was 1.8 lower (5.2 lower to 1.7 higher) |

| Change in snoring frequency | 121 (3 studies) 2–3 months | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b due to risk of bias, imprecision | The mean change in snoring frequency in the intervention groups was 0.5 standard deviations lower than in the control group (1.0 to 0.0 lower) |

| Change in snoring intensity | 121 (3 studies) 2–3 months | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b due to risk of bias, imprecision | The mean change in snoring intensity in the intervention groups was 0.9 standard deviations lower than in the control group (1.9 to 0.1 lower) |

| Change in BMI (kg/m2) | 145 (4 studies) 2–3 months | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b due to risk of bias, imprecision | The mean change in BMI in the intervention groups was 0.5 higher (0.8 lower to 1.7 higher) |

| Change in neck circumference (in) | 145 (4 studies) 2–3 months | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b due to risk of bias, imprecision | The mean change in neck circumference in the intervention groups was 0.2 lower (1.2 lower to 0.8 higher) |

| Change in abdominal circumference (in) | 70 (2 studies) 2–3 months | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b due to risk of bias, imprecision | The mean change in abdominal circumference in the intervention groups was 0.5 inches lower (4.6 lower to 3.6 higher) |

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence: High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. aAll included studies assessed at high risk of bias. bSmall sample size (< 400 total participants), small number of studies. AHI = apnea-hypopnea index, BMI = body mass index, CI = confidence interval, ESS = Epworth Sleepiness Scale, OSA = obstructive sleep apnea, PSQI = Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, SaO2 = oxygen saturation.

DISCUSSION

Pediatric studies

Since just one pediatric study was available for each outcome, no meta-analysis could be conducted for the 2 studies on pediatric patients.24,26 One study recorded PSGs for both the pretreatment and posttreatment groups,26 and the other study used a PSG for only the pretreatment and pulse oximetry for the posttreatment groups.24 In the pediatric study measuring AHI,26 there was an improvement in the average AHI in the intervention group from 4.9 events/h to 1.4 events/h. Whereas the other study24 showed an improvement in average oxygen desaturation index (ODI) from 5.9 events/h to 3.6 events/h after respiratory muscle therapy. Although ODI is not the same as AHI, due to ODI not measuring respiratory efforts and apnea events, research has shown that there is direct correlation between the 2 readings.31 Based on a clinical study done on 475 surgical adult patients, the sensitivity of ODI to detect AHI was between 96.3% and 100.0%, with the percentage increasing as the ODI and AHI increased into the criteria of severe OSA (> 30 events/h).31 Meanwhile, the specificity of ODI as a surrogate for AHI was 81.6–98%, with the percentage decreasing as the ODI and AHI increased toward > 30 events/h.31 Therefore, although a meta-analysis could not be performed, the decrease in ODI in the intervention group may correlate to a proportional decrease in AHI, which agrees with the other pediatric study26 measuring AHI and seems to be promising for respiratory muscle therapy to be a viable treatment for pediatric OSA.

Adult studies

For the adult RCTs (6 reported AHI outcomes at baseline and posttreatment14,16,21,25,27,28), there was a significant improvement in the average overall AHI of −7.6 events/h (95% CI = −11.7 to −3.5; P ≤ .001; Figure 3) for patients with mild to severe OSA (the lowest pretreatment average AHI ± SD was 14.6 ± 1.5 events/h, with the highest average pretreatment AHI being 30.9 ± 20.6 events/h). Overall, the weighted average AHI for adults improved by 36% compared with baseline after respiratory muscle therapy. Duration of the treatment was 5 weeks to 4 months of respiratory muscle therapy. Our meta-analyses showed that the patients receiving upper airway muscle therapy14,21,25 had the largest improvement in AHI, with an average of −9.6 events/h (95% CI −2.4 to −17.4; P = .010) versus controls, followed by the 2 studies that used expiratory lower airway16,27,28 muscle exercises with -6.74 events/h (95% CI −1.7 to −10.4; P = .006). In contrast, inspiratory lower airway muscle therapy31 showed an average increase in AHI compared with controls of +9.4 events/h in 1 study.28

Closer examination of the inspiratory lower airway muscle therapy study28 showed that the controls used 15% of the maximal inspiratory pressure (MIP), whereas the intervention groups used 75% of MIP. Results in this study28 showed an improvement in the control group of overall AHI of approximately −4.9 events/h (after 15% MIP), whereas the intervention group showed a worsening of the overall AHI of approximately +4.3 events/h from baseline (after 75% MIP). There was not a lot of information as to why the authors had chosen a 15% MIP as the control therapy—other than this was the pressure set to mimic slow breathing.28 Clearly more research is warranted to determine the optimal inspiratory pressure needed to improve OSA based on overall AHI. In fact, in 1 of the studies16 it was mentioned that where patients underwent both inspiratory and expiratory respiratory muscle training, many of the patients complained about difficulty and discomfort associated with the inspiratory portion.16 A sensitivity analysis on adult patients excluding the inspiratory lower airway muscle therapy study28 demonstrated an overall improvement in weighted average AHI of 44.6% versus 36.0%, including the inspiratory lower airway study with a pressure of 75% MIP.

On the basis of the Bernoulli principle, a mathematical approach may explain why increasing inspiratory drive could result in an airway obstruction. The pharyngeal region is a collapsible soft-walled tube that is bordered by 2 rigid segments (Starling resistor theory).32 In this segment of the upper airway, the elasticity of a small area compresses with increased air flow velocity, where collapsing of this elastic segment results in an apneic event.9,33–35 Increasing a patient’s inspiratory drive through the diaphragm expands the lungs and causes this increase in airflow9,33–35; therefore, in accordance with the Bernoulli effect, the harder the patient inspires, the greater the velocity of airflow in the elastic compressible airway segment and the greater the decrease in the static pressure in the smallest segment of the airway, causing a reduction of cross-sectional area and hence the more severe the obstruction.

It is truly not understood as to whether the inspiratory or expiratory phase of the lower airway muscles plays a greater role in OSA. Lower respiratory muscles such as the diaphragm, intercoastal, and accessory muscles allow for increased ventilatory effort.36 In addition, lower airway muscles or lung function play a key role in the abnormal partial pressure of oxygen related to OSA.37 On the basis of a study to determine respiratory muscle function in patients with OSA, in 4 of 6 apneic patients, the diaphragm seemed to be the principal inspiratory muscle during apnea and, in 2 of 6, it appeared that the expiratory muscles such as intercostal/accessory muscles played a large role.36 In the same study, during the expiratory phases of OSA, 4 of 6 patients showed an increase in stomach pressure and inward abdominal drive during the expiratory stages of an apnea, consistent with abdominal muscle utilization triggered by an augmented ventilatory effort.36

Two studies recorded AI at baseline and posttreatment.14,25 Significant improvement in AI from baseline of −4.2 events/h was found in intervention group compared with controls (95% CI −7.7 to −0.8; P = .016). In addition, 3 studies21,25,28 recorded minimum saturation at baseline and posttreatment in their outcomes. However, there was no significant change in minimum SaO2% in intervention groups compared with controls (results not shown). The changes in minimum SaO2% were not statistically significant. In addition, because there was a significant decrease in the AI and snoring frequency (P = .044; Figure 5A), there may have been a decrease in the duration of minimum SaO2 in the intervention groups.14,21,22,25 Although there were no overall significant changes in sleep efficiency, 3 of 4 studies showed improvement.14,21,25,28 BMI, neck, and abdominal circumference resulted in no significant changes; however, again, longer follow-up would be necessary to confirm such changes (all interventions were evaluated for 5 weeks to 4 months).

A total of 5 studies documented ESS at baseline and posttreatment.14,16,21,25,27 There was no statistically significant improvement in ESS from baseline (P = .062); however, an average improvement of −2.5 was observed in the intervention groups compared with the controls (95% CI −5.1 to 0.1; P = .062; Figure 4). The minimal clinically important improvement in ESS lies between −2 and −3,38 therefore the average change observed in this systematic review might be clinically significant. Subgroup analyses of upper/lower airway showed that both upper and lower subgroups showed no statistically significant improvements in ESS (results not shown). Although the average improvement of −2.5 in ESS was not statistically significant, one must remember that at least one study (lower inspiratory muscle therapy28) compared the intervention (75% MIP) to a control group (15% MIP) that was not truly a placebo but could have been a cointervention. In addition, an improvement of −2.5 on ESS could be clinically significant, although not statistically significant, especially for those people with an ESS score of 10–12. Because an ESS score of 9 or lower is considered normal, a score of 10 or higher would indicate a possible need for medical attention. Analysis of all 5 studies that documented ESS at baseline and posttreatment14,16,21,25,27 showed that all groups resulted in a posttreatment ESS score below 9. Only 1 group21 did not show any improvement. In that study, those patients started with a mean ESS score of 7 at baseline (normal) and resulted with a mean score of 7 after intervention (normal).

PSQI was documented in 4 studies at baseline and posttreatment.16,21,27,28 Overall there was a statistically significant improvement in PSQI of −1.3 units in intervention group compared with controls (95% CI −2.4 to −0.2; P = .026; Figure 4B). The minimal clinically important improvement in PSQI is −3,39 therefore this difference might not be clinically significant. Posttreatment PSQI improved the most for the lower airway inspiratory muscle therapy intervention group compared with the 2 expiratory lower airway studies and one of the upper airway studies.16,21,27

Overall, when looking at the individual study results in the intervention groups, all the studies that documented ESS and PSQI in this systematic review reported an improved sleepiness measurements for all methods of respiratory muscle therapy (except the previously mentioned study,21 which showed improvement in PSQI but no change from a normal baseline ESS).

There were 4 studies that recorded sleep efficiency (in percentage) at baseline and posttreatment.14,21,25,28 No significant change in sleep efficiency from baseline was found (results not shown). Meanwhile 3 studies recorded snoring frequency and snoring intensity with 3 different scales.14,21,22 There were significant changes in snoring frequency (standardized difference in means = −0.5; 95% CI −1.0 to −0.01; P = .044; Figure 5A) but not snoring intensity (standardized difference in means = −0.9; 95% CI −1.9 to 0.1; P = .068; Figure 5B) in the intervention groups compared with controls.

Four studies recorded BMI and neck circumference and 2 studies recorded abdominal circumference in their outcomes.14,21 There were no significant changes in BMI, neck circumference, or abdominal circumference in intervention group compared with controls (results not shown).

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The systematic review completed by Camacho et al4 showed an average 50% improvement in AHI (24.5 ± 14.3 to 12.3 ± 11.8 events/h), nonsubstantial improvements in the average lowest SaO2 (83.9 ± 6.0 to 86.6 ± 7.3%), significant improvements in reported snoring and significant improvement in ESS (average improvement from 14.8 ± 3.5 to 8.2 ± 4.1). However, they based their systematic review on 3 RCTs14,25,26 with upper airway muscle therapy (all of which were included in our review) and they also included 6 nonrandomized trials.

The oldest review published in 20103 included 3 RCTs14,27,40 and concluded without a meta-analysis, based on the original 3 RCTs, that respiratory muscle therapy could be used as an alternative supporting or complementary treatment of OSA based on improvement in AHI, ESS, and PQSI scores. Two of the RCTs were included in our systematic review, one on upper airway,14 one on lower airway,27 and the third RCT40 was omitted because the intervention was based on using electrical neurostimulation that did not fit our inclusion criteria for respiratory muscle therapy. In 2013, a review15 that investigated multiple different alternatives to OSA treatment and listed 2 RCTs for respiratory muscle therapy, one for upper and one for lower airway,14,27 concluded that these options are viable alternatives to CPAP.

The most recent systematic review41 included a variety of minimally invasive alternative therapies for OSA and included upper airway respiratory therapy RCTs, however, it did not perform a meta-analysis of the findings. The authors generalized that myofunctional and speech therapy are more effective for reducing ESS versus AHI. Some of the strengths of this systematic review are that we were able to include a large number of RCTs in our meta-analyses and compare various outcomes.

Quality of the evidence

The overall quality of evidence in this systematic review was low (Table 5) due to the high risk of bias, with all the RCTs not double blinded and a majority lacking allocation concealment.

Heterogeneity of the review

Some degree of clinical heterogeneity was found in the studies. In terms of study design, the studies were all RCTs; however, some were single blinded and some not blinded (Table 2). The studies varied in treatment duration, which ranged from 5 weeks16 to 4 months27 for each intervention. Different types of myofunctional/oropharyngeal exercises were used in the included studies with varied characteristics and procedures (Table 4). Subgroup analyses were conducted for lower (inspiratory versus expiratory) and upper airway exercises. There were also differences among the interventions in each of these subcategories which at this point could not be analyzed due to the small sample size. The controls did not have any treatment in one of the studies.27 Two of the studies recruited only children.24,26 The small number of included studies precluded subgroup analyses by intervention and control therapy, number of participants, treatment duration, and severity of OSA, to name a few. Patients with major systemic disorders were not included in any of the studies.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Four databases were searched: PubMed, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, and EMBASE up to November 2018. We hand searched the included studies and literature reviews to find any additional eligible studies. Meta-analyses could not be conducted on the 2 pediatric studies with average ages of 4.826 and 7.1 years.24 The results of this systematic review are applicable to adult patients of both sexes with mild to severe OSA. The reported average age of the participants ranged from 44.3 years16 to 69.1 years28 in the adult studies. Since the reported treatment duration ranged from 5 weeks16 to 4 months,27 this review cannot comment on the long-term efficacy of respiratory exercises. The 9 included studies were conducted in 5 countries, including 4 in Brazil; one in the United States, Switzerland, and Taiwan; and 2 in Italy (Table 2).

Implications for research and clinical practice

Since no published RCTs describing a combination of both upper and lower airway muscles could be found, it would be difficult to assess if exercising both muscles, cumulatively, would result in a more substantial improvement. However, in a nonrandomized controlled study, where the controls were patients who refused to follow the treatment, both upper and lower airway muscle therapy were used for the intervention, resulting in a significant reduction; after 6 months of therapy the baseline average AHI ± SD of 22.8 events/h improved to 15.4 ± 16.8 events/h after 1 year to 13.8 ± 17.5 events/h.42

When respiratory muscle therapy is combined with CPAP, it appears patients become more tolerable to CPAP, resulting in longer duration of CPAP use.25 Because all the RCTs reported outcomes after 5 weeks to 4 months, longer follow-up after initiation of respiratory muscle therapy is needed to establish the lasting effects of such therapy. It has been shown that after 1 year of management of OSA, there was a significant decrease in inflammation markers such as CD4+ T-cells, IL-6 and IL-8 in the upper airway, which resulted in a reduction in the collapsibility of the airway43; hence advocating for longer follow-up times in future studies to assess the true benefits of respiratory muscle therapy in patients with OSA. In addition one nonrandomized controlled study demonstrated that improvements in overall AHI were sustained for a 1-year period.42

This systematic review with meta-analyses reveals that a statistically significant reduction in overall AHI can be achieved with upper airway respiratory muscle therapy and expiratory lower airway therapy; however, the clinical significance of this result is unclear. The reduction in overall AHI was not sufficient to decrease AHI to the desired adult therapeutic overall average AHI level of 5 events/h or below (Table 3), which agrees with previous review articles.3,4,15,41 At this point, the potential mechanism behind the OSA improvement with respiratory airway exercises is not clear. There are no published studies that investigate the additive effects of respiratory muscle therapy with mandibular advancement devices. However, it has been well documented that oral appliances are very effective in treating mild OSA.44 Further studies are necessary, establishing a reduced risk of bias by blinding all parties, longer duration, or follow-up by exceeding 5 months and possibly merging exercises of the lower and upper airway and demonstrating the value of respiratory exercises combined with CPAP or mandibular advancement devices. In addition, although we labeled all these exercises under one category as respiratory muscle therapy, there are some dissimilarities among studies. One limitation of this systematic review is the fact that due to the small number of studies, one can only conclude that further research is needed to determine which specific exercises have the greatest individual effect on the management of OSA.

CONCLUSIONS

Overall, based on the results, this systematic review with meta-analyses demonstrates that lower and upper respiratory muscle therapy improve AHI significantly in mild to severe patients with OSA. As no adverse effects were reported in the included studies, respiratory muscle therapy may be considered for treatment in mild cases of OSA or as additional therapy in more moderate to severe cases and may help avoid other more invasive procedures. However, the included studies were heterogeneous, few in number with low quality of evidence, high risk of bias, and small sample size and not long term follow up. Hence, further research is needed in terms of which respiratory muscle therapies provide the best outcomes, ideal duration, and the benefit as a complimentary treatment to CPAP or oral appliances.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

All authors have reviewed and approved this manuscript. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AHI

apnea hypopnea index

- BMI

body mass index

- CI

confidence interval

- CPAP

continuous positive airway pressure

- ESS

Epworth Sleepiness Scale

- MIP

maximal inspiratory pressure

- ODI

oxygen desaturation index

- OSA

obstructive sleep apnea

- PSG

polysomnography

- PSQI

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

- q1

25% quartile

- q3

75% quartile

- RCT

randomized controlled trials

- SaO2

oxygen saturation

- SD

Standard Deviation

REFERENCES

- 1.Berry RB, Brooks R, Gamaldo CE, et al. for the American Academy of Sleep Medicine . The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications. Version 2.4. Darien, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee-Chiong TL. Sleep Medicine Essentials. New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valbuza JS, De Oliveira MM, Conti CF, Prado LBF, De Carvalho LBC, Do Prado GF. Methods for increasing upper airway muscle tonus in treating obstructive sleep apnea: Systematic review. Sleep Breath. 2010;14(4):299–305. 10.1007/s11325-010-0377-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Camacho M, Certal V, Abdullatif J, et al. Myofunctional therapy to treat obstructive sleep apnea: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep. 2015;38(5):669–675. 10.5665/sleep.4652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Remmers JE, DeGroot WJ, Sauerland EK, Anch AM. Pathogenesis of upper airway occlusion during sleep. J Appl Physiol. 1978;44(6):931–938. 10.1152/jappl.1978.44.6.931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coceani L. Oral structures and sleep disorders: a literature review. Int J Orofacial Myology. 2003;2915–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cori JM, O’donoghue FJ, Jordan AS. Sleeping tongue: Current perspectives of genioglossus control in healthy individuals and patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Nat Sci Sleep. 2018;10169–179. 10.2147/NSS.S143296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jordan AS, White DP, Owens RL, et al. The effect of increased genioglossus activity and end-expiratory lung volume on pharyngeal collapse. J Appl Physiol. 2010;109(2):469–475. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00373.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Attanasio R, Bailey D. Dental Management of Sleep Disorders. 1st ed.;. Ames, IA: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mohamed AS, Sharshar RS, Elkolaly RM, Serageldin SM. Upper airway muscle exercises outcome in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Egypt J Chest Dis Tuberc. 2017;66(1):121–125. 10.1016/j.ejcdt.2016.08.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Afsharpaiman S, Shahverdi E, Vahedi E, Aqaee H. Continuous positive airway pressure compliance in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Tanaffos. 2016;15(1):25–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sarrell EM, Chomsky O, Shechter D. Treatment compliance with continuous positive airway pressure device among adults with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA): how many adhere to treatment?. Harefuah. 2013;152(3):140–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dempsey JA, Xie A, Patz DS, Wang D. Physiology in medicine: Obstructive sleep apnea pathogenesis and treatment-considerations beyond airway anatomy. J Appl Physiol. 2014;116(1):3–12. 10.1152/japplphysiol.01054.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guimarães KC, Drager LF, Genta PR, et al. Effects of oropharyngeal exercises on patients with moderate obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179(10):962–966. 10.1164/rccm.200806-981OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tfaili A, Barker JA, Chebbo A. Alternative therapies for obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Med Clin. 2013;8(4):543–556. 10.1016/j.jsmc.2013.07.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuo Y-C, Song T-T, Bernard JR, Liao Y-H. Short-term expiratory muscle strength training attenuates sleep apnea and improves sleep quality in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2017;24386–91. 10.1016/j.resp.2017.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iber C, Ancoli-Israel S, Chesson ALJr, Quan SFfor the American Academy of Sleep Medicine . The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications. 1st ed. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: The Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep. 1991;14(6):540–545. 10.1093/sleep/14.6.540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buysse D, Reynolds CIII, Monk TH, Berman S, Kupfer D. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index : A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28(2):193–213. 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ieto V, Kayamori F, Montes MI, et al. Effects of oropharyngeal exercises on snoring: A randomized trial. Chest. 2015;148(3):683–691. 10.1378/chest.14-2953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diaféria G, Santos-Silva R, Truksinas E, et al. Myofunctional therapy improves adherence to continuous positive airway pressure treatment. Sleep Breath. 2017;21(2):387–395. 10.1007/s11325-016-1429-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higgins J, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. https://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org/; 2011; Accessed on May 29, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Villa MP, Evangelisti M, Martella S, Barreto M, Del Pozzo M. Can myofunctional therapy increase tongue tone and reduce symptoms in children with sleep-disordered breathing?. Sleep Breath. 2017;21(4):1025–1032. 10.1007/s11325-017-1489-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Diaferia G, Badke L, Santos-Silva R, et al. Effect of speech therapy as adjunct treatment to continuous positive airway pressure on the quality of life of patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Med. 2013;14(7):628–635. 10.1016/j.sleep.2013.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Villa MP, Brasili L, Ferretti A, et al. Oropharyngeal exercises to reduce symptoms of OSA after AT. Sleep Breath. 2015;19(1):281–289. 10.1007/s11325-014-1011-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Puhan MA, Suarez A, Lo Cascio C, Zahn A, Heitz M, Braendli O. Didgeridoo playing as alternative treatment for obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2006;332(7536):266–270. 10.1136/bmj.38705.470590.55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vranish JR, Bailey EF. Inspiratory muscle training improves sleep and mitigates cardiovascular dysfunction in obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 2016;39(6):1179–1185. 10.5665/sleep.5826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weighted Standard Deviation . DATAPLOT Reference Manual. https://www.itl.nist.gov/div898/software/dataplot/refman2/ch2/weightsd.pdf.

- 30.Schwingshackl L, Knüppel S, Schwedhelm C, et al. Perspective: NutriGrade: A scoring system to assess and judge the meta-evidence of randomized controlled trials and cohort studies in nutrition research. Adv Nutr An Int Rev J. 2016 Nov;7(6):994–1004. 10.3945/an.117.016188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chung F, Liao P, Elsaid H, Islam S, Shapiro CM, Sun Y. Oxygen desaturation index from nocturnal oximetry: A sensitive and specific tool to detect sleep-disordered breathing in surgical patients. Anesth Analg. 2012;114(5):993–1000. 10.1213/ANE.0b013e318248f4f5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gold AR, Schwartz AR. The pharyngeal critical pressure: The whys and hows of using nasal continuous positive airway pressure diagnostically. Chest. 1996;110(4):1077–1088. 10.1378/chest.110.4.1077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Longobardo GS, Evangelisti CJ, Cherniack NS. Analysis of the interplay between neurochemical control of respiration and upper airway mechanics producing upper airway obstruction during sleep in humans. Exp Physiol. 2008;93(2):271–287. 10.1113/expphysiol.2007.039917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hori Y, Shizuku H, Kondo A, Nakagawa H, Kalubi B, Takeda N. Endoscopic evaluation of dynamic narrowing of the pharynx by the Bernouilli effect producing maneuver in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2006;33(4):429–432. 10.1016/j.anl.2006.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fajdiga I. Snoring imaging. Chest. 2005;128(2):896–901. 10.1378/chest.128.2.896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilcox PG, Pare PD, Road JDFJ. Respiratory muscle function during obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Dis. 1990;142(3):533–539. 10.1164/ajrccm/142.3.533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carvalho TM da CS, Soares AF, Climaco DCS, Secundo IV, Lima AMJe. Correlation of lung function and respiratory muscle strength with functional exercise capacity in obese individuals with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. J Bras Pneumol. 2018;44(4):279–284. 10.1590/s1806-37562017000000031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patel S, Kon SSC, Nolan CM, et al. The Epworth Sleepiness Scale: Minimum clinically important difference in obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197(7):961–963. 10.1164/rccm.201704-0672LE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hughes CM, McCullough CA, Bradbury I, et al. Acupuncture and reflexology for insomnia: A feasibility study. Acupunct Med. 2009;27(4):163–168. 10.1136/aim.2009.000760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Randerath WJ, Galetke W, Domanski U, et al. Tongue-muscle training by intraoral electrical neurostimulation in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 2004;27(2):254–259. 10.1093/sleep/27.2.254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gao YN, Wu YC, Lin SY, Chang JZC, Tu YK. Short-term efficacy of minimally invasive treatments for adult obstructive sleep apnea: A systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Formos Med Assoc. 2019;118(4):750–765. 10.1016/j.jfma.2018.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tang S, Qing J, Wang Y, et al. Clinical analysis of pharyngeal musculature and genioglossus exercising to treat obstructive sleep apnea and hypopnea syndrome. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2015;16(11):931–939. 10.1631/jzus.B1500100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vicente E, Marin JM, Carrizo SJ, et al. Upper airway and systemic inflammation in obstructive sleep apnoea. Eur Respir J. 2016;48(4):1108–1117. 10.1183/13993003.00234-2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marklund M, Stenlund H, Franklin KA. Mandibular advancement devices in 630 men and women with obstructive sleep apnea and snoring: Tolerability and predictors of treatment success. Chest. 2004;125(4):1270–1278. 10.1378/chest.125.4.1270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]