Abstract

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) are pathologically activated neutrophils and monocytes with potent immunosuppressive activity. They are implicated in the regulation of immune responses in many pathological conditions and are closely associated with poor clinical outcomes in cancer. Recent studies have indicated key distinctions between MDSCs and classical neutrophils and monocytes, and, in this Review, we discuss new data on the major genomic and metabolic characteristics of MDSCs. We explain how these characteristics shape MDSC function and could facilitate therapeutic targeting of these cells, particularly in cancer and in autoimmune diseases. Additionally, we briefly discuss emerging data on MDSC involvement in pregnancy, neonatal biology and COVID-19.

Subject terms: Tumour immunology, Innate immune cells

This Review from Gabrilovich and colleagues discusses our current understanding of the development and functions of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs). Recent work has identified unique metabolic properties and gene expression patterns in MDSCs that could help in the development of new therapies for cancer and autoimmunity.

Introduction

Neutrophils and monocytes with potent immunosuppressive activity were first reported around 30 years ago and later named myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs)1 to underscore their unique place among myeloid cells. Many studies (more than 5,000 listed in PubMed to date) have implicated these cells in regulating immune responses in pathological conditions, including cancer, chronic infection, sepsis and autoimmunity. Physiological roles for MDSCs have also been described in pregnancy and neonates2,3. It is now evident that MDSCs contribute to the myeloid cell diversity observed in pathological conditions. However, the nature of this diversity and the characteristics that allow for the distinction of MDSCs from neutrophils and monocytes have been poorly understood. Emerging studies have characterized the specific genomic, proteomic and metabolic features of MDSCs that define these cells as pathologically activated neutrophils and monocytes. The specific pathways involved in the acquisition of MDSC characteristics by neutrophils and monocytes have also been described4–6.

In this Review, we discuss new data on the genomic and metabolic characteristics of MDSCs. We describe how these characteristics are linked with MDSC function and how they can be used in therapeutic targeting. We focus on two main disease areas: cancer, where MDSC function exacerbates the disease, and autoimmune and chronic inflammatory diseases, where MDSCs can limit the severity of disease. Finally, we briefly discuss emerging studies that suggest roles for MDSCs in pregnancy, neonatal biology and in COVID-19.

Main characteristics of MDSCs

Definition and basic features of MDSCs

There are two major groups of MDSCs in humans and mice, namely granulocytic/polymorphonuclear MDSCs (PMN-MDSCs) and monocytic MDSCs (M-MDSCs), classified according to their origin from the granulocytic or monocytic myeloid cell lineages, respectively. A small group of myeloid precursor cells with MDSC features has also been identified in humans (but not in mice) and named ‘early MDSCs’. This group of cells with potent immunosuppressive features is mostly comprised of myeloid progenitors and precursors and represents less than 5% of the total population of MDSCs7. A recent report suggested that a substantial proportion of PMN-MDSCs might also differentiate from distinct monocytic precursors named monocyte-like precursor of granulocytes8. However, the intriguing possibility that some PMN-MDSCs may differentiate from precursors other than granulocytic precursors requires further validation.

Several years ago, we proposed the concept that a pathological state of immune activation is a common feature associated with the emergence of MDSCs3. Classical myeloid cell activation takes place in response to pathogens and tissue damage and is mainly driven via danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and Toll-like receptor (TLR) activation. This leads to the rapid mobilization of neutrophils and monocytes from the bone marrow and manifests in the activation of phagocytosis, respiratory burst, degranulation and neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation. By contrast, pathological activation arises from persistent stimulation of the myeloid cell compartment owing to the prolonged presence of myeloid growth factors and inflammatory signals in the settings of cancer, chronic infections or inflammation, and autoimmune diseases. Examples of such activating signals include cytokines and various growth factors like granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF; also known as CSF1), IL-6, IL-1β, adenosine signalling or endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress signalling (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of basic characteristics of MDSCs and classical neutrophils and monocytes

| Characteristic | Myeloid cell population | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neutrophils | Monocytes | PMN-MDSCs | M-MDSCs | |

| Origin | CMP and granulocytic precursors | CMP and monocytic precursors | CMP, granulocytic precursors, monocytic-like precursors | CMP and monocytic precursors |

| Activation stimuli | Primarily bacterial and viral pathogens; TLR ligands, PAMPs and DAMPs; relatively short duration of activation | Prolonged exposure to cytokines released during chronic infection, inflammation, autoimmune diseases and cancer | ||

| Activation process | Classical one-phase activation: rapid mobilization to tissues associated with compensatory myelopoiesis; fast degranulation, cytokine release, activation of phagocytosis and respiratory burst | Pathological two-phased activation: myelopoiesis and conditioning in the bone marrow, conversion to pathologically activated cells in tissues; modest myelopoiesis, altered cell metabolism | ||

| Standard phenotypical markers in mice | CD11b+LY6G+Ly6Clo | CD11b+Ly6G−Ly6Chi | CD11b+Ly6G+Ly6Clo | CD11b+Ly6G–Ly6Chi |

| Standard phenotypical markers in humans | CD11b+CD14−CD15+/CD66b+; high-density cells | CD14+CD15−HLA-DRhi | CD11b+CD14−CD15+/CD66b+; low-density cells | CD14+CD15−HLA-DRlo/– |

| Novel markers in mice | NA | NA | CD11b+Ly6G+CD84+ | CD11b+Ly6G-Ly6ChiCD84+ |

| Novel markers in humans | NA | NA | CD15+/CD66b+CD14−LOX1+; CD15+/CD66b+CD14−CD84+ | CD14+/CD66b−CXCR1+; CD14+/CD66b−CD84+ |

| Maturity and fate | Mostly mature cells; lifespan in steady-state conditions ~ 2–3 days | Differentiation to macrophages in tissues | Mostly immature cells, with variable presence of mature cells depending on type of disease; very short lifespan | Differentiation to macrophages in tissues; in cancer, differentiation to tumour-associated macrophages |

| Major developmental factors | GM-CSF, G-CSF, SCF | GM-CSF, M-CSF, FLT3L, SCF | High levels of GM-CSF, VEGF, IL-6, IL-1β, adenosine, HIF1α | High levels of M-CSF, VEGF, adenosine, HIF1α |

| Main regulators of suppressive functions | NA | NA | STAT3, STAT1, STAT6, NF-κB, ER stress pathways, cAMP, COX2, PTGES, CEBPβ, IRF8, RB1 downregulation, oxidized lipids | |

CMP, common myeloid progenitor; DAMP, damage-associated molecular pattern; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; G-CSF, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; GM-CSF, granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor; HIF1α, hypoxia inducible factor 1α; M-CSF, macrophage colony-stimulating factor; MDSC, myeloid-derived suppressor cell; M-MDSC, monocytic MDSC; NA, not applicable; PAMP, pathogen-associated molecular pattern; PMN, polymorphonuclear; PTGES, prostaglandin E synthase; SCF, stem cell factor; TLR, Toll-like receptor; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

The signals driving MDSC development occur in two partially overlapping phases4. In phase 1, myeloid cell expansion and conditioning takes place in the bone marrow and spleen. Phase 2 is characterized by the conversion of neutrophils and monocytes into pathologically activated MDSCs, which takes place primarily in peripheral tissues. Many molecular pathways that regulate the development of MDSCs have been identified (Table 1) and are described in detail in several previously published reviews4–6.

Currently, in mice, there are no phenotypic cell surface markers that allow for the separation of classical neutrophils from PMN-MDSCs or classical monocytes from M-MDSCs. Therefore, the same phenotypical characteristics that are used to identify granulocytes and monocytes in tissues are also used for the identification of PMN-MDSCs and M-MDSCs, respectively, and MDSCs in mice are distinguished functionally based on their ability to suppress other immune cells (Table 1). In humans, although PMN-MDSCs and neutrophils share the same cell surface phenotypes, PMN-MDSCs are purified on a lower density gradient (1.077 g/ml), whereas neutrophils are purified on a higher density gradient (1.1–1.2 g/ml)7. In recent years, lectin-type oxidized LDL receptor 1 (LOX1; encoded by ORL1 gene) has emerged as a specific marker of human PMN-MDSCs that can be used to identify these cells in the blood and tumours of patients with cancer9–14. Furthermore, M-MDSCs can be distinguished from monocytes in peripheral blood by the detection of MHC class II expression. Although MHC class II is widely used for the identification of M-MDSCs, it is probably not sufficient to fully discriminate between monocytes and M-MDSCs. New molecules recently described may help to further delineate these groups of cells7 (Table 1).

The main characteristic that defines MDSCs is their ability to inhibit immune responses, including those mediated by T cells, B cells and natural killer (NK) cells. M-MDSCs and PMN-MDSCs share key biochemical features that enable their suppression of immune responses, including the upregulation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) expression, induction of ER stress, expression of arginase 1 and expression of S100A8/A9. They also have unique features that may affect their ability to regulate different aspects of immune responses. For example, PMN-MDSCs preferentially use reactive oxygen species (ROS), peroxynitrite, arginase 1 and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) to mediate immune suppression, whereas M-MDSCs use nitric oxide (NO), immunosuppressive cytokines such as IL-10 and TGFβ, and the expression of immune regulatory molecules like PDL1 (ref.15) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Distinguishing MDSCs from classical neutrophils and monocytes.

The figure depicts the genes (depicted inside the cell) and surface molecules that can be used to distinguish polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells (PMN-MDSCs) and monocytic MDSCs (M-MDSCs) from classical neutrophils and monocytes. Factors are depicted in yellow, green and red based on whether they are useful markers in mice only, humans only, or both mice and humans, respectively. The figure also illustrates the main immunosuppressive mechanism used by MDSCs. Please note that this information was obtained from studies of MDSCs in cancer. CXCR1, CXC-chemokine receptor 1; FATP2, fatty acid transport protein 2; LOX1, lectin-type oxidized LDL receptor 1; NO, nitric oxide; PGE2, prostaglandin E2.

The need for uniform nomenclature of immunosuppressive neutrophils

In recent years, many research groups have studied myeloid cells to identify new targets with the goal to improve current immunotherapeutic regimens or to overcome resistance to immunotherapy. Although the term PMN-MDSC is most widely used in the literature to define immunosuppressive neutrophils, several other names are also used in some reports. The term granulocytic MDSC is mentioned frequently. This term was used during the early days of MDSC research. It is probably as good a term as PMN-MDSC; however, it does not bear any different functional meaning than PMN-MDSC. In some studies in cancer, ‘N1’ and ‘N2’ polarized neutrophil nomenclature is used to mimic the nomenclature of M1/M2 polarized macrophages. ‘N1 neutrophils’ have features of classical neutrophils, whereas ‘N2 neutrophils’ have typical features of PMN-MDSCs16,17. In contrast to macrophages, neutrophils in tumour tissues have a very short lifespan and are constantly recruited to tumour sites and their polarization in situ is very problematic. Another example of confusing terminology is the use of the term ‘low-density neutrophils’. These cells have typical features of PMN-MDSCs18. A low density is one of the defining characteristics of PMN-MDSCs as described in numerous studies. The introduction of all those terms leads to further confusion for investigators and creates an impression of the existence of multiple populations of neutrophils with immunosuppressive features when, in fact, they all describe the same cells — PMN-MDSCs.

Lessons from gene expression profiles of MDSCs in cancer

Due to the absence of suitable phenotypical markers, it has not been possible to distinguish PMN-MDSCs from neutrophils in the same mouse. Therefore, investigators have compared cells expressing PMN-MDSC/neutrophil-associated markers from tumour-bearing or tumour-free mice. In earlier studies using microarray analysis, PMN-MDSCs were found to have distinct transcriptomic programmes compared to neutrophils. Specifically, PMN-MDSCs showed a higher expression of genes associated with the cell cycle, autophagy, G protein signalling and the CREB pathway. Neutrophils showed a higher expression of genes associated with NF-κB signalling via the CD40, IL-1, IL-6, TLR and tumour necrosis factor (TNF) pathways as well as via lymphotoxin-β receptor signalling19. The mRNA profile of tumour-associated neutrophils significantly differed from the profile of splenic neutrophils and PMN-MDSCs. Neutrophils showed high levels of granule protein production and activation of the respiratory burst, which are critically important for their antibacterial functions. These pathways were progressively lost in splenic PMN-MDSCs and even more dramatically lost in tumour-associated neutrophils. By contrast, many immune-related genes and pathways, including genes related to the antigen-presenting complex and cytokines (for example, TNF, IL-1α, IL-1β), were upregulated in PMN-MDSCs and further upregulated in tumour-associated neutrophils17. The differences between these reports probably reflect the source of neutrophils/PMN-MDSCs and their activation status. In studies where authors compared naive neutrophils from bone marrow with PMN-MDSCs from spleen or tumours17, PMN-MDSCs showed higher inflammatory cytokine production and activation of some downstream targets of NF-κB signalling. This may be the difference between activated PMN-MDSCs and non-activated bone marrow neutrophils. In another study19 where classically activated neutrophils (with casein) were compared to PMN-MDSCs, classically activated neutrophils showed higher levels of IL-6, TNF and NF-κB signalling compared to PMN-MDSCs. These observations are consistent with the concept that different stimuli drive the generation of classically activated neutrophils and PMN-MDSCs.

More precise analysis has been possible in humans when PMN-MDSCs and neutrophils were obtained from the same patient. Using density gradient separation and microarray analysis, we found that gene profiles seen in neutrophils isolated from healthy donors or from patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and head and neck cancer were very similar. By contrast, gene-expression profiles of PMN-MDSCs and neutrophils from the same patient were vastly different9. Genes enriched in PMN-MDSCs included regulators of the ER stress response, the MAPK pathway, M-CSF, IL-6, IFNγ and NF-κB; these molecules were previously implicated in MDSC development20. This study also identified LOX1 as a specific marker that can be used for the identification and characterization of PMN-MDSCs in patients with cancer9.

A comparative RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis of M-MDSCs and monocytes sorted from the same patients with advanced NSCLC revealed a distinct transcriptional profile. M-MDSCs showed upregulation of several genes associated with neutrophil functions, including CXC-chemokine receptor 1 (CXCR1)8. In a study in pancreatic ductal carcinoma, transcriptomic analysis of M-MDSCs revealed that M-MDSCs show a distinct gene signature compared to monocytes. STAT3 was identified as a crucial regulator for monocyte re-programming into M-MDSCs21. In a more recent study, single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) confirmed that PMN-MDSCs and M-MDSCs isolated from spleens and tumours of a model of breast cancer have a gene signature that strongly differs from that of neutrophils and monocytes, respectively22. However, there was a substantial overlap between the gene signatures of PMN-MDSCs and M-MDSCs (namely, expression of IL1B, ARG2, CD84 and WFDC17), indicating that similar immunosuppressive features can be acquired by both neutrophils and monocytes. CD84 was identified as a marker defining MDSCs in cancer. In mice, M-MDSCs from primary tumours showed an increase in CD84 expression compared with monocytes from control tissue, but the expression of CD84 was barely detectable in M-MDSCs from spleen. High levels of CD84 expression were seen in PMN-MDSCs isolated from both primary tumours and spleens. CD84high MDSCs exhibit a T cell-suppressive capacity and increased ROS production22. In humans, CD84 was expressed by M-MDSCs and PMN-MDSCs and CD84 was co-expressed with LOX1 in PMN-MDSCs. PMN-MDSCs emerged from neutrophil progenitors via an alternative maturation process. Consistent with another recent report8, these results suggest that PMN-MDSCs may use a separate differentiation pathway from that used by neutrophils. M-MDSCs had a similar alternative maturation process occurring during their differentiation but, in contrast to PMN-MDSCs, no transitional states were described22. It will be important to test whether CD84 is restricted to MDSCs in breast cancer or is a common feature of M-MDSCs in cancer.

Song et al. used scRNA-seq to compare transcriptional profiles of tumour and normal tissues from four patients with early-stage NSCLC and confirmed the presence of cells with transcriptional features of MDSCs23. According to a trajectory analysis, Song et al. showed that cells expressing M-MDSC-associated markers (namely IL-10, CD14 and VEGFA) and PMN-MDSC-associated markers (namely IL-6, OLR1 and TGFβ1) were observed along the monocyte-to-M2 macrophage transition but MDSC subsets did not show root or branch-level enrichment. These finding pointed out that MDSCs are molecularly distinct from M1-like and M2-like macrophages. In a recent study, subsets of immature (CD11b−CD13–/loCD16−), intermediate (CD11b+CD13–/loCD16−) and mature (CD11b+CD13+CD16+) neutrophils were identified in the tumour microenvironment of patients with multiple myeloma24. The frequency of mature neutrophils at diagnosis was significantly associated with a negative clinical outcome and a high ratio of mature neutrophils to T cells was associated with a poorer progression-free survival. Mature neutrophils (CD11b+CD13+CD16+) from patients with multiple myeloma were shown to exert the strongest level of T cell immunosuppression. These cells expressed higher levels of genes encoding inflammatory cytokines (namely TGFB1, TNF and VEGFA) and higher levels of genes associated with a PMN-MDSC phenotype (namely NF-κB genes, PTGS2, CSF1, IL-8, IRF1, IL4R, STAT1, STAT3 and STAT6) when compared to intermediate and immature neutrophils24.

Various experimental approaches have been used to identify CD71 as a marker of early neutrophil progenitors in humans25. CD71 was also shown to be expressed by a population of proliferating neutrophils in the blood of patients with melanoma and in the blood and tumours of patients with lung cancer25. These CD71+ neutrophils expressed high levels of markers associated with an immature phenotype (CD38, CD49d and CD48) and had higher expression of CD304, a VEGFR2 co-receptor associated with the pro-tumour functions of macrophages. However, since these cells also expressed antigen-presenting proteins (HLA-DR) and costimulatory molecules (CD86), it is unclear whether they have pro-tumour or antitumour functions and whether they may have any relationship with PMN-MDSCs25. In a recent study in patients with colon cancer, PMN-MDSCs showed upregulation of several pathways associated with DNA damage responses, chemotaxis, apoptosis, MAPK signalling, TGFβ signalling and various myeloid differentiation-related transcripts compared with monocytic antigen-presenting cells (APCs) or early MDSCs26. Furthermore, PMN-MDSCs had an elevated expression of genes related to Janus kinase (JAK) and STAT signalling. Additionally, the authors found that pathways involving phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), IL-6 and TGFβ were upregulated in M-MDSCs and cell cycle-related pathways were upregulated in early MDSCs compared with in monocytic APCs. Importantly, acetylation-related genes were upregulated in both PMN-MDSCs and M-MDSCs, indicating that epigenetic modifications may also play a role in the regulation of multiple tumour-promoting genes in PMN-MDSCs and M-MDSCs26.

Thus, MDSCs have a distinct transcriptional profile characterized by the expression of pro-inflammatory and immunosuppressive pathways (Fig. 1). Although specific genomic signatures and specific markers of MDSCs are now starting to emerge, their clinical utility needs to be formally established. The need to distinguish MDSCs from classical monocytes and neutrophils will be critical for the design of effective therapies targeting MDSC populations.

Metabolic characteristics of MDSCs

Metabolic reprogramming is one of the hallmarks of cancer. Tumour cells reprogramme their metabolism to sustain a high energy demand, thereby supporting rapid proliferation, survival and differentiation. The competition for nutrients and oxygen in the tumour microenvironment forces immune cells to adapt their metabolism. MDSCs sense the environment and respond by selecting the most efficient metabolic pathways to sustain their suppressive and pro-tumorigenic functions27 (Fig. 2). Below, we highlight recent studies that have provided insight into various aspects of MDSC metabolism.

Fig. 2. Metabolic characteristics of MDSCs.

a | Changes in lipid and glucose metabolism that occur in myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and in tumour cells in the tumour environment are shown. MDSCs in the tumour microenvironment show an upregulation of fatty acid oxidation (FAO) and glycolysis and a decrease in oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS). They also show increased lipid accumulation and increased production of the metabolites methylglyoxal, arginine, tryptophan and cysteine. Key changes in the tumour microenvironment are depicted in the yellow boxes. b | Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and the unfolded protein response (UPR) in MDSCs. The UPR is characterized by an orchestrated upregulation of activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), inositol requiring enzyme 1 (IRE1α) and PKR-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK). The transcription factor C/EBP-homologous protein (CHOP) is a critical mediator of the PERK pathway, whereas spliced X-box binding protein 1 (sXBP1) is a mediator of the IRE1α pathway. ER stress induced the expression of TNF-related apoptosis-induced ligand receptors (DR5) and lectin-type oxidized LDL receptor 1 (LOX1) and the conversion of neutrophils to polymorphonuclear MDSCs. The reduced NRF2 signalling favoured the accumulation of cytosolic mitochondrial DNA and consequent expression of antitumour type I interferon, in a STING-dependent manner97.

Lipid metabolism in MDSCs

There is now ample evidence that lipid metabolism is altered in MDSCs and that this plays a critical role in their differentiation and functions. Diets enriched in polyunsaturated fatty acids or high-fat diets were shown to favour the differentiation of MDSCs from bone marrow precursors and to potentiate the suppressive activity of these cells in mice28. A recent report demonstrated an association between increased adiposity and increased tumour growth and mortality. In tumour-bearing mice, obesity was associated with an increased accumulation of MDSCs and a reduced CD8+ T cell to MDSC ratio in various tissues. Increased adiposity was also associated with the accumulation of MDSCs in the spleens and lymph nodes of tumour-free mice29.

The uptake of lipids, mediated by the upregulation of the scavenger receptor CD36, favoured the switch from glycolysis to fatty acid oxidation (FAO) as a primary source of energy in tumour-associated MDSCs30,31. MDSCs underwent metabolic reprogramming that upregulated the mitochondrial electron transfer complex and the tricarboxylic acid cycle. The deletion of CD36 or FAO inhibition affected the suppressive functions of MDSCs, delayed tumour growth, and enhanced the efficacy of chemotherapy and immunotherapy30,31. Recently, the fatty acid transport protein 2 (FATP2) was identified as a regulator of the suppressive functions of PMN-MDSCs. FATP2 was responsible for the uptake of arachidonic acid and for the subsequent synthesis of PGE2. The inhibition of FATP2 abrogated the suppressive functions of PMN-MDSCs and enhanced the efficacy of cancer immunotherapy32. PMN-MDSCs were implicated in the negative regulation of antigen cross-presentation by dendritic cells (DCs) and this mechanism was mediated by the transfer of oxidized lipids from PMN-MDSCs to DCs33. The cross-presentation of tumour-associated antigens in vivo by DCs was substantially improved in MDSC-depleted or myeloperoxidase (MPO)-deficient tumour-bearing mice. PMN-MDSCs express higher levels of MPO when compared to neutrophils34 and MPO deficiency also affects the suppressive activity of PMN-MDSCs, indicating the critical role of MPO in the biology of these cells in cancer33. The pharmacological inhibition of MPO in combination with checkpoint blockade also reduced tumour growth in tumour mouse models33. Since PMN-MDSCs but not neutrophils have immunosuppressive activity, it is likely that the antitumour effect of MPO inhibition was mediated via PMN-MDSCs.

Glucose metabolism

MDSCs exhibit an increase in glycolysis, the pentose phosphate pathway and tricarboxylic acid cycle during their differentiation and activation3,27. PMN-MDSCs were shown to use both glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) in a preclinical model of nasopharyngeal carcinoma35. MDSCs had high glucose and glutamine uptake rates, a reduced oxygen consumption rate and most of the ATP generated was obtained through a glycolysis-dependent mechanism36. This study revealed that a high glycolytic flux is needed for the maturation of MDSCs from bone marrow precursors and suggested an indirect mechanism by which the consumption of carbon sources by MDSCs results in the suppression of effector T cells. Patel et al.37 showed that bone marrow neutrophils from mice with early stages of tumour progression had some transcriptional characteristics of PMN-MDSCs but lacked suppressive activity. These cells upregulated OXPHOS and glycolysis and produced more ATP than neutrophils from control mice. This facilitated the migration of these cells to tissues and could represent the first step of pathological activation of neutrophils in cancer37.

The upregulation of glycolytic pathways protected MDSCs from apoptosis and contributed to their survival by preventing ROS-mediated apoptosis via the antioxidant activity of the glycolytic intermediate phosphoenolpyruvate38. Glycolysis increased in parallel with increased arginase I activity in MDSCs. Under hypoxic conditions, the activation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF1α) induced the switch from OXPHOS to glycolysis in MDSCs39,40. HIF1α is a critical regulator of the differentiation and function of MDSCs in the tumour microenvironment41,42. HIF1α facilitated the differentiation of M-MDSCs into tumour-associated macrophages through a mechanism involving CD45 tyrosine phosphatase activity and the downregulation of STAT3 activity42,43.

In contrast to monocytes, M-MDSCs isolated from tumour tissue of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma had a dormant metabolic phenotype. These cells failed to utilize glucose, had a reduced cellular ATP content, and showed reduced cellular bioenergetics and lowered baseline mitochondrial respiration44. This peculiar metabolic phenotype was mediated by the accumulation of methylglyoxal in MDSCs. In turn, MDSCs suppressed T cell activation and proliferation by transferring methylglyoxal to T cells. Methylglyoxal suppressed T cell function by the chemical depletion of cytosolic amino acids, such as L-arginine, as well as by rendering L-arginine-containing proteins non-functional through their glycation44. Whether these findings can be recapitulated in other conditions remains to be determined.

In summary, in contrast to classically activated neutrophils and monocytes, the metabolic functions of MDSCs are characterized by the increased accumulation of lipids and FAO, which promotes their suppressive activity, and a switch to glycolysis (Fig. 2). Data on the contribution of glycolysis to the suppressive capacity of MDSCs are few and contradictory. Glycolysis might be important during the differentiation and migration of MDSCs rather than in the regulation of suppressive functions. However, more in-depth studies are needed to decipher the relative contribution of these different metabolic pathways to the differentiation and functions of MDSCs.

Amino acid metabolism

The deprivation of essential metabolites, including arginine, tryptophan and cysteine, from the microenvironment has been used by MDSCs to regulate T cell functions. The depletion of arginine through the upregulation of arginase 1 was one of the first T cell-suppressive mechanisms described in MDSCs45. Arginine catabolism through NOS2 is another key suppressive mechanism of MDSCs46 and their release of peroxynitrite can induce apoptosis in T cells as well as inhibiting T cell function and migration47–49. IDO-dependent tryptophan metabolism is another pathway used by MDSCs to inhibit immune responses. MDSCs decrease the levels of tryptophan in the external environment by inducing IDO, which catabolizes this essential amino acid to N-formylkynurenine50–52.

However, such metabolic profiles in myeloid cells do not necessarily define them as MDSCs. Besides metabolic changes, cells have to acquire suppressive functions. In the context of MDSCs, it is clear that these cells show a different metabolic profile when compared to normal neutrophils and monocytes and this metabolic switch is directly associated with the acquisition of suppressive functions. These studies were performed in the setting of cancer. Whether similar features are associated with MDSCs in other pathological conditions needs to be determined in further research.

Roles of MDSCs in cancer

The role of MDSCs in the formation of the premetastatic niche

Metastatic disease represents the main cause of death in patients with cancer. Metastasis requires the circulation of tumour cells from the primary tumour site to distant organs, which have been ‘primed’ for the engraftment of disseminating tumour cells in a process known as the formation of the premetastatic niche (Fig. 3). Neutrophils or PMN-MDSCs are recruited to the premetastatic niches mostly through the chemokine receptors CXCR2 and CXCR4 (refs53,54). It was recently shown that bone marrow-derived neutrophils in early stages of cancer lack the immunosuppressive ability that characterizes MDSCs but exhibit higher spontaneous migration, higher OXPHOS and glycolysis, and increased production of ATP compared to naive neutrophils. The transcriptomic profiles of these cells demonstrated enrichment of ER stress-associated pathways (Box 1). Bone marrow PMN-MDSCs isolated from patients with late-stage cancer were immunosuppressive but their migratory capacity and metabolism were indistinguishable from control neutrophils37. Importantly, these cells had potent spontaneous migratory activity, suggesting that they may migrate better to non-inflamed tissues than control neutrophils or PMN-MDSCs. While it is plausible that these cells may be converted to PMN-MDSCs once they reach their destination, this has not yet been formally tested. PMN-MDSCs in the premetastatic niches may facilitate the escape of tumour cells by suppressing immune cells, inducing matrix remodelling and promoting angiogenesis55, which in turn facilitate the engraftment of tumour cells. Another mechanism of regulation of tumour metastasis was described in a recent study by Li et al.56, who demonstrated, in a breast cancer model, that neutrophils accumulated neutral lipids via the repression of adipose triglyceride lipase activity. Neutrophil-specific deletion of adipose triglyceride lipase decreased metastasis in mice and lipid transfer from neutrophils to tumour cells was shown to facilitate metastasis56. The authors reported that these cells suppressed NK cells, suggesting that they may be PMN-MDSCs.

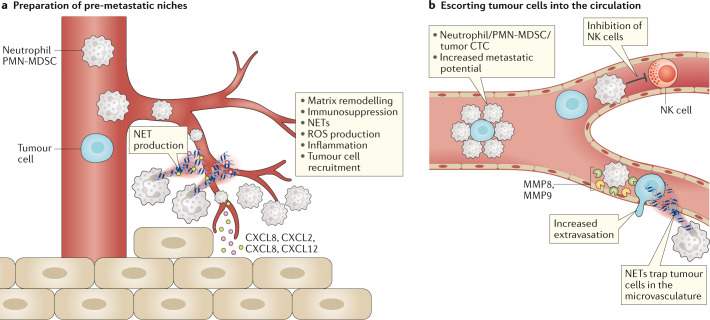

Fig. 3. Contribution of MDSCs to the formation of the premetastatic niche.

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) promote metastasis by ‘priming’ the premetastatic niche to enhance the engraftment by circulating tumour cells (CTCs) (panel a) and by escorting tumour cells into the circulation (panel b), promoting their metastatic potential, inhibiting their killing by immune cells and by promoting their extravasation into the tissues. NET, neutrophil extracellular trap; NK cell, natural killer cell; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; PMN, polymorphonuclear; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

NETs are extracellular structures released by neutrophils in response to stimuli and composed of cytosolic and granule proteins as well as DNA. NETs were shown to promote metastasis, facilitate ovarian cancer colonization to the omentum and promote extravasation of circulating colorectal cancer to the liver and lung in preclinical colorectal cancer models57–61. Moreover, NETs can recruit tumour cells to the premetastatic niche via CDC25 (ref.62). Although it is not yet known whether NETs are produced more frequently by PMN-MDSCs than by neutrophils, it was recently reported that granulocytic cells from tumour-bearing mice are more prone to producing NETs than neutrophils from tumour-free mice57. The pharmacological targeting of NETs may be a promising way to reduce metastatic colonization of the tumour.

Circulating tumour cells (CTCs) are precursors of metastasis and are often found in the circulation of cancer patients. CTCs are associated with white blood cells63, including neutrophils. The clusters formed by CTCs and white blood cells are rare in the peripheral circulation but increase exponentially and can be trapped in the capillaries before reaching the periphery64. Furthermore, CTCs cluster with neutrophils more frequently than with any other immune cells. Cancer patients with high percentages of neutrophil–CTC clusters in the blood had worse clinical outcomes64. The neutrophils contained in the clusters showed a gene expression profile similar to that of PMN-MDSCs. Additionally, neutrophil-containing CTC clusters were able to form metastasis much faster that CTC alone64. These findings suggest that, at the very early stage of cancer dissemination, neutrophils can promote the formation of metastasis by enhancing the proliferative abilities of CTCs; these results are consistent with mouse data describing the pro-metastatic potential of neutrophils in early-stage cancer37.

CTCs can also be targeted by immune cells with antitumour activity, including NK cells and CD8+ T cells65. In mouse models of metastasis, the depletion of NK cells prior to the injection of tumour cells increased metastasis to the lung. PMN-MDSCs inhibited NK cell-mediated killing of CTCs and promoted metastasis formation into the lungs56,66. MDSCs express high levels of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and PMN-MDSCs were shown to promote both the extravasation and engraftment of CTCs by producing high levels of MMP8 and MMP9 (ref.66) (Fig. 3).

Box 1 ER stress in regulation of MDSCs.

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) are characterized by the accumulation of misfolded proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), which induces the unfolded protein response (UPR)140,141. The UPR features an orchestrated upregulation of activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), inositol requiring enzyme 1 (IRE1α) and PKR-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK). The transcription factor C/EBP-homologous protein (CHOP) is a mediator of the PERK pathway, whereas spliced X-box binding protein 1 (sXBP1) is a mediator of the IRE1α pathway142. CHOP positively regulates the accumulation and suppressive functions of tumour-infiltrating MDSCs. CHOP expression in MDSCs was induced by reactive oxygen and nitrogen species and regulated by ATF4 (ref.143). ER stress induced the expression of TNF-related apoptosis-induced ligand receptors (TRAIL-Rs)84,85. The activation of IRE1α/XBP1-dependent pathways was shown to be involved in the upregulation of LOX1 and in the conversion of normal neutrophils to PMN-MDSCs9. PERK signalling was increased in tumour MDSCs and regulated their suppressive functions through the inhibition of STING signalling97. The deletion of PERK reprogrammed MDSCs towards myeloid cells with the ability to activate CD8+ T cell-mediated immunity against cancer. In the absence of PERK, tumour MDSCs showed a reduced NRF2-driven antioxidant capacity and impaired mitochondrial respiratory homeostasis. The reduced NRF2 signalling favoured the accumulation of cytosolic mitochondrial DNA and the consequent expression of antitumour type I interferon in a STING-dependent manner (Fig. 2).

Therapeutic targeting of MDSCs in cancer

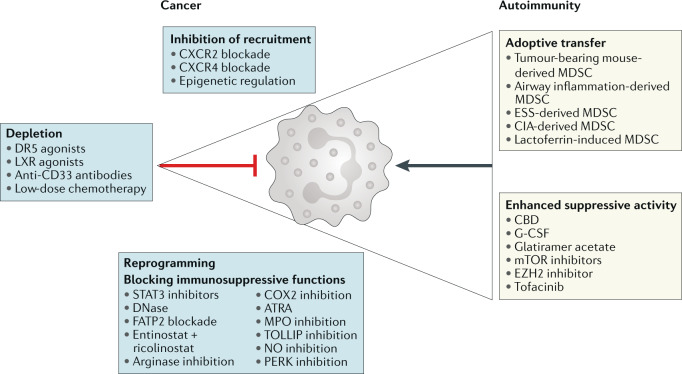

Although MDSCs have a short-lifespan in tissues, their continuous recruitment to sites of chronic inflammation enables them to have long-lasting effects at these sites. However, because their lifespan in tissues is short, the state of pathological activation of these cells in tissues is difficult to reverse. Therefore, effective therapies could aim to target MDSCs by blocking their differentiation in the bone marrow, inhibiting their migration to the affected tissues, or by manipulating the tissue microenvironment (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Targeting MDSCs in cancer and autoimmune diseases.

Opposite strategies are used to regulate myeloid-derived suppressor cell (MDSC) function in cancer, where therapies are aimed at reducing MDSC recruitment, accumulation and suppressive functions, or in autoimmune disease, where increased MDSC accumulation or function may be used to restrain disease severity. ATRA, all-trans retinoic acid; CBD, cannabidiol; CIA, collagen-induced arthritis; CXCR, CXC-chemokine receptor; ESS, experimental Sjögren syndrome; EZH2, enhancer of zeste homologue 2; FATP2, fatty acid transporter protein 2; G-CSF, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; LXR, liver X receptor; MPO, myeloperoxidase; NO, nitric oxide; PERK, PKR-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase; STAT3, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3.

Targeting MDSC recruitment

MDSCs are more immunosuppressive in the tumour site than in lymphoid organs67. The migration of neutrophils and PMN-MDSCs to tumours is mainly driven by the chemokine receptor CXCR2 in response to CXCL1 and CXCL2 in mice and humans as well as in response to IL-8 (also known as CXCL8) in humans68. High IL-8 levels have been associated with increased neutrophil infiltration into tumours and poorer responses to immune-checkpoint blockade69,70. Earlier studies showed that blocking PMN-MDSC recruitment to tumours by genetic ablation of CXCR2 or with small-molecule CXCR2 inhibitors improved the outcome of metastatic sarcoma and enhanced the efficacy of anti-PD1 treatment in established tumours71. These findings were recently confirmed and expanded in mouse models of head and neck cancer, pancreatic cancer, and metastatic liver cancer53,72,73. A recent study showed how epigenetic therapy can influence MDSC accumulation and promote macrophage differentiation at premetastatic niches. By using low doses of methyltransferase and histone deacetylase inhibitors, Lu et al. demonstrated reduced CCR2-mediated and CXCR2-mediated MDSC accumulation in premetastatic niches in the lung and increased overall survival in mice after surgical resection of the primary tumours74.

MDSC depletion

MDSCs are short-lived cells that are constantly replaced and released into the circulation. The depletion of cells with high rates of renewal can be challenging but several approaches have provided encouraging results. Chemotherapeutic drugs, such as 5-fluorouracil, carboplatin, paclitaxel or gemcitabine, can reduce MDSC numbers in the circulation and promote a more robust antitumour immune response75–77, but these agents are not specific for MDSCs and affect all rapidly proliferating cells, including antitumour T cells.

A more refined approach uses antibodies recognizing CD33, a marker expressed on the surface of human myeloid cells. A monoclonal anti-CD33 antibody (gemtuzumab) conjugated with a toxin (ozogamicin) was shown to deplete CD33-expressing MDSCs with good results in a phase II clinical trial78–81. The recognition of CD33 has been exploited for CD16 and IL-15 tri-specific killer engager (TriKE) in haematological malignancies82. This molecule (GTB-3550) crosslinks CD33 and CD16 expressed by NK cells, inducing ADCC and NK cell cytotoxicity and proliferation. Although GTB-3550 has been shown to reduce TIGIT-mediated NK cell inhibition by MDSCs83, ADCC-dependent depletion of MDSCs could be another possible mechanism of action. GTB-3550 is currently in a phase II clinical trial (NCT03214666) and an evaluation of MDSCs in treated patients could answer this question.

The activation of ER stress is a common characteristic of MDSCs in both mice and humans that distinguish them from monocytes and neutrophils (Box 1). Activation of the ER stress pathway induced the upregulation of DR5, a TRAIL receptor, on MDSCs and targeting of this molecule rapidly induced MDSC apoptosis84. An agonistic DR5 antibody, DS-8273a, has also been tested in a phase I clinical trial. The treatment was well tolerated and induced a selective reduction of MDSCs in a subset of patients with various types of advanced cancers, which was associated with increased progression-free survival85.

Liver X receptor (LXR) has a potent effect on MDSC survival. LXR activation was able to strongly reduce MDSC numbers in tumour-bearing mice by inducing apoptosis in these cells through apolipoprotein E (APOE) signalling. MDSC apoptosis was associated with a reduction of immunosuppression and activation of antitumour T cell responses. Preclinical tumour models responded well to two LXR agonists: GW3956 and RGX-104 (ref.86). RGX-104 is currently in a phase I clinical trial, with initial results showing that the drug promotes T cell activation and is effective in reducing both PMN-MDSC and M-MDSC counts in the circulation86.

Reprograming MDSCs to enhance antitumour immunity

The blockade of MDSC immunosuppressive functions can improve antitumour immune responses. Early studies showed that all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) promoted the differentiation of M-MDSCs into macrophages and DCs and killed PMN-MDSCs in both mice and humans87–89. More recently, in preclinical models of breast cancer, the depletion of MDSCs via ATRA treatment has been shown to improve the efficacy of VEGFR2 inhibitors as anti-angiogenic therapy. In those models, the triple combination of ATRA with a VEGFR2 inhibitor and conventional chemotherapy significantly delayed tumour growth90. ATRA therapy in combination with anti-CTLA4 immune-checkpoint blockade was tested in patients with melanoma, showing a reduction in the number of circulating MDSCs and in MDSC expression of immunosuppressive genes91.

The treatment of mice with the FATP2 inhibitor lipofermata markedly reduced tumour growth. Moreover, it synergized with anti-CTLA4 antibody treatment32. Since PGE2 biosynthesis is considered a downstream target of FATP2, these results were consistent with the role of PGE2 as a potent inhibitor of T cell function in cancer92. The targeting of systemic PGE2 with cyclooxygenase 2 (COX2) inhibitors has also been shown to block MDSC expansion in mouse tumour models93–96. However, the prolonged systemic use of COX2 inhibitors is associated with substantial haematologic, cardiovascular and gastrointestinal toxicities. The selective targeting of FATP2 (which is necessary for downstream PGE2 synthesis) in PMN-MDSCs may instead offer the opportunity to inhibit PGE2 only in pathologically activated PMN-MDSCs and mostly within the tumour site, where expression of FATP2 is the highest32.

It was recently shown that targeting the PERK pathway of ER stress response reprogrammed tumour-associated M-MDSCs towards cells with antitumour functions. The inhibition of PERK augmented the efficacy of checkpoint inhibitors in preclinical models97. Another approach involves the targeting of TOLLIP, which is a signalling adaptor molecule expressed in myeloid cells and recently implicated in the acquisition of immunosuppressive function by PMN-MDSCs. The genetic ablation of TOLLIP reduced tumour formation in a model of carcinogen-induced colon cancer and adoptive transfer of TOLLIP-deficient neutrophils in tumour-bearing mice reduced tumour growth and increased T cell responses98. Although TOLLIP blockade has not been tested in the study, those findings make TOLLIP an interesting target for cancer immunotherapy. Thus, multiple approaches to targeting MDSCs in cancer have been proposed (Fig. 4). Ongoing clinical trials will soon identify which one is most promising.

Roles of MDSCs in autoimmune disease

MDSC accumulation has been described in patients with various autoimmune disorders, including type 1 diabetes, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), inflammatory bowel disease and autoimmune hepatitis. It is expected that, in autoimmune diseases, the increased presence of MDSCs might correlate with positive clinical outcomes and decreased disease severity. However, as discussed below, this is not always the case.

Association of MDSCs with more severe autoimmune disease

Increased frequencies of M-MDSCs and PMN-MDSCs were observed in patients with relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis during relapse compared to those with stable disease. However, patients with secondary progressive multiple sclerosis displayed decreased frequencies of M-MDSCs and PMN-MDSCs99. Discordant results regarding the effect of MDSCs in rheumatoid arthritis have been reported in both preclinical mouse models and in patients. The prevalence of circulating MDSCs and plasma arginase 1 increased significantly in patients with rheumatoid arthritis compared to healthy controls and were negatively correlated with peripheral T helper 17 (TH17) cells100. However, a different study showed that MDSCs might promote arthritis onset in mice by sustaining TH17 cell differentiation. MDSC infiltration in arthritic joints positively correlates with high disease activity but MDSC frequency in peripheral blood negatively correlates with TH17 cell numbers101. Both M-MDSC and PMN-MDSC frequency and number were elevated in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and SLE, which correlated with disease severity102–104. Moreover, MDSCs have been found to accumulate in murine models of asthma, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), SLE and collagen-induced arthritis, where the presence of MDSCs correlates with TH17 cell accumulation and increased disease severity105–108. Interestingly, patients with SLE showed the accumulation of low-density granulocytes with a high expression of LOX1, a marker of PMN-MDSCs. From that study, however, it was unclear if these cells could directly supress T cell function102.

Apparently, during pathological autoimmune reactions associated with inflammation there is an expansion of MDSCs, which may be a protective mechanism that inhibits the autoimmune reaction to a certain extent. However, the control of pathological processes is not in itself sufficient. Therefore, the prediction is that the more severe the disease, the higher the production of MDSCs will be. This hypothesis was tested in number of studies as described below.

Therapeutic applications of MDSCs in autoimmunity and allergy

LOX1+ PMN-MDSCs accumulated in the blood of patients with established multiple sclerosis as well as in patients with clinically isolated syndromes (that is, the first neurologic episode of multiple sclerosis) compared to in healthy donors109. Notably, the frequency of MDSCs was lower in patients who experienced a relapse than in patients with stable disease109. Moreover, PMN-MDSCs were found to accumulate in the central nervous system of mice with EAE at the onset of disease and their frequency was decreased following recovery from EAE. The acquisition of an MDSC phenotype was restricted to the central nervous system, where PMN-MDSCs reduced pathogenic B cell accumulation109. Cannabidiol and IFNβ have been shown to attenuate EAE severity by promoting MDSC accumulation and/or suppressive activity110,111.

In early studies, MDSCs showed a protective effect on asthma and airway inflammation by suppressing TH2-type immune responses, one of the main contributors to airway inflammation. Recently, group 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s) have emerged as major contributors in asthma induction. PMN-MDSCs were shown to inhibit the production of inflammatory cytokines by ILC2s in a mouse model of allergic airway inflammation through a COX1-dependent pathway, which reduced the severity of disease. In this model, antibody-mediated depletion of PMN-MDSCs exacerbated the disease and promoted ILC2-driven inflammation112. Moreover, the adoptive transfer of MDSCs to mice with allergic airway inflammation reduced the severity of disease113. MDSCs have also been shown to have a protective effect in murine models of Sjogren syndrome and arthritis, where the activation of the suppressive functions of MDSCs ameliorated the severity of the diseases114–116.

MDSCs have also been implicated in the onset or progression of inflammatory bowel disease. In murine models of colonic inflammation, the use of a histone-methyl transferase inhibitor reduces the severity of the disease by inducing the accumulation of immunosuppressive MDSCs in the colon117. Moreover, mTOR inhibitors and glatiramer acetate (a compound approved for the treatment of multiple sclerosis) have shown efficacy in treating mouse models of colitis by enhancing the suppressive functions of MDSCs118,119.

The adoptive transfer using three types of splenic MDSCs (total MDSCs, M-MDSCs and PMN-MDSCs) obtained from mice with collagen-induced arthritis demonstrated that all these MDSCs markedly ameliorated inflammatory arthritis and profoundly inhibited T cell proliferation120. Consistent with these observations, the adoptive transfer of MDSCs generated in vitro following treatment with lactoferrin markedly reduced autoimmune inflammation in lung and liver121 (Fig. 4). These findings demonstrate that, although naturally occurring MDSCs may not be sufficient to control autoimmune diseases, their therapeutic expansion, activation or adoptive transfer can clearly have beneficial effects in limiting autoimmune pathology.

Other emerging roles for MDSCs

For many years, the biological roles of MDSCs were thought to be restricted to cancer, autoimmune diseases, chronic inflammation and infectious diseases. In recent years, a broader role of MDSCs in biology has emerged that challenges a prevailing view on the mechanisms of the development of these cells. The accumulation of MDSCs during pregnancy was described in a number of studies and these cells were directly implicated in maternal–fetal tolerance by suppressing T cell responses122–126. The percentage of MDSCs was shown to be decreased in spontaneously aborting mice compared with in control mice and the depletion of MDSCs was associated with increased cytotoxicity of decidual NK cells127. MDSCs are now emerging as part of the complex system protecting the fetus during gestation.

The accumulation of MDSCs in neonates was more surprising since the suppression of the immune system is not considered as favourable for newborns. However, several studies described the accumulation of MDSCs during first weeks of life in newborn humans and mice96,121,128–130. Mechanistically, MDSCs played an important role in the protection of newborns from inflammation associated with seeding of the gut with microbiota. MDSC deficiency in very-low weight prematurely born infants was associated with necrotizing enterocolitis96,121. The mechanism of transitory MDSC accumulation in newborns was different from that described in cancer and was dependent on lactoferrin96,121. MDSCs may be an attractive option in the treatment of pathological inflammatory conditions associated with low birthweight in infants.

Very recently, cells with MDSC features were implicated in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by SARS-CoV-2. Several reports described the accumulation of potently immunosuppressive M-MDSCs and PMN-MDSCs in patients with severe COVID-19 (refs131–133). A study in high-dimensional flow cytometry and scRNA-seq of peripheral blood cells from patients with COVID-19 revealed an accumulation of HLA-DRlow monocytes with characteristics of M-MDSCs. Immature neutrophils with an immunosuppressive profile (PMN-MDSCs) accumulated in the blood and lungs. These myeloid cells release large amounts of S100A8/A9 proteins. The higher plasma levels of these proteins correlated with patients who developed a severe form of COVID-19 (ref.134). These findings were corroborated in a large study where scRNA-seq and single-cell proteomics of whole-blood and peripheral blood mononuclear cells demonstrated elevation of HLA-DRhiCD11chi inflammatory monocytes with an interferon-stimulated gene signature in mild cases of COVID-19. By contrast, severe COVID-19 was associated with the accumulation of neutrophil precursors, dysfunctional mature neutrophils and HLA-DRlo monocytes with apparent features of MDSCs135. These results are similar to the previous reports describing the accumulation of MDSCs in patients with sepsis and septic shock136–138. In a recent preprint study, scRNA-seq was used to profile immune cells isolated from matched blood samples and broncho-alveolar lavage fluids of patients with COVID-19 and healthy controls139. This analysis revealed an immune signature of the disease severity that correlated with the accumulation of naive lymphoid cells in the lung and the expansion and activation of myeloid cells in peripheral blood. Myeloid-driven immunosuppression was a hallmark of COVID-19 evolution and arginase 1 expression was associated with monocyte immune regulatory features. Importantly, the loss of immunosuppression in monocytes and neutrophils was associated with fatal clinical outcomes in patients with severe COVID-19. It is important to point out that the results of scRNA-seq of myeloid cells are protocol and time dependent, which will require careful assessment in future studies. It appears that massive exposure of myeloid progenitors to bacterial or viral products triggers the activation of immunosuppressive programming in myeloid cells, leading to the rapid development of MDSCs. The mechanisms of this phenomenon need to be determined.

Perspective

Emerging evidence suggests that MDSCs play crucial roles in shaping the immune response in many pathological settings as well as in some physiological settings such as pregnancy and in the first weeks of life. We now have a better understanding of the origins of these cells and of how they mediate immunosuppression. However, the precise mechanisms that drive neutrophils and monocytes to differentiate into MDSCs remain unclear. Although the key genomic and metabolic characteristics of these cells are now described, the precise genomic signatures that allow for the identification and analysis of MDSCs in clinical settings remain to be established. A major challenge will be to determine if PMN-MDSCs could be subdivided into smaller populations with specific functional characteristics or if they represent a discrete single population distinct from classical neutrophils; the same is true for M-MDSCs. This goal can be accomplished by the analysis of scRNA-seq. This is not an easy task, especially with respect to neutrophils and PMN-MDSCs due to their low transcriptional activity and difficulty in isolating them without inducing cell activation. Recent data on the identification of specific precursors of these cells is intriguing but requires strong experimental validation. Finally, but probably most importantly, the challenge remains on how best to selectively target MDSCs. In the coming years, we may witness a strong effort to determine whether targeting these cells improves clinical outcomes in different disease settings.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank S. Gabrilovich, Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, for help with editing the manuscript.

Glossary

- Monocyte-like precursor of granulocytes

Recently identified population of monocytic precursors of granulocytes (primarily polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs)) accumulated in tumour-bearing hosts.

- S100A8/A9

Heterodimer, calcium binding pro-inflammatory protein that presents in neutrophils and monocytes and greatly accumulates in MDSCs; it is considered as one of the hallmarks of these cells.

- M1/M2 polarized macrophages

‘M1’ and ‘M2’ are classifications historically used to define macrophages activated in vitro as pro-inflammatory (when ‘classically’ activated with IFNγ and lipopolysaccharides) or anti-inflammatory (when ‘alternatively’ activated with IL-4 or IL-10), respectively. However, in vivo macrophages are highly specialized, transcriptomically dynamic and extremely heterogeneous with regards to their phenotypes and functions, which are continuously shaped by their tissue microenvironment. Therefore, the M1 or M2 classification is too simplistic to explain the true nature of in vivo macrophages, although these terms are still often used to indicate whether the macrophages in question are more pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory.

- Methylglyoxal

CH3C(O)CHO is a reduced derivative of pyruvic acid involved in the formation of advanced glycation end products.

- STING

Stimulator of interferon genes (STING) induces type I interferon production.

- Lactoferrin

A globular glycoprotein from the transferrin family widely expressed in various secretory fluids such as milk, saliva, tears and nasal secretions.

Author contributions

The authors contributed equally to all aspects of the article.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information

Nature Reviews Immunology thanks the anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Filippo Veglia, Emilio Sanseviero.

References

- 1.Gabrilovich DI, et al. The terminology issue for myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:425. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dorhoi A, et al. Therapies for tuberculosis and AIDS: myeloid-derived suppressor cells in focus. J. Clin. Invest. 2020;130:2789–2799. doi: 10.1172/JCI136288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Veglia F, Perego M, Gabrilovich D. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells coming of age. Nat. Immunol. 2018;19:108–119. doi: 10.1038/s41590-017-0022-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Condamine T, Mastio J, Gabrilovich DI. Transcriptional regulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2015;98:913–922. doi: 10.1189/jlb.4RI0515-204R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang W, Xia X, Mao L, Wang S. The CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein family: its roles in MDSC expansion and function. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:1804. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Beury DW, Parker KH, Horn LA. Survival of the fittest: how myeloid-derived suppressor cells survive in the inhospitable tumor microenvironment. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2020;69:215–221. doi: 10.1007/s00262-019-02388-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bronte V, et al. Recommendations for myeloid-derived suppressor cell nomenclature and characterization standards. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:12150. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mastio J, et al. Identification of monocyte-like precursors of granulocytes in cancer as a mechanism for accumulation of PMN-MDSCs. J. Exp. Med. 2019;216:2150–2169. doi: 10.1084/jem.20181952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Condamine T, et al. Lectin-type oxidized LDL receptor-1 distinguishes population of human polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer patients. Sci. Immunol. 2016;1:aaf8943. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aaf8943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nan J, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress induced LOX-1+ CD15+ polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells in hepatocellular carcinoma. Immunology. 2018;154:144–155. doi: 10.1111/imm.12876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim HR, et al. The ratio of peripheral regulatory T cells to Lox-1+ polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells predicts the early response to anti-PD-1 therapy in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019;199:243–246. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201808-1502LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chai E, Zhang L, Li C. LOX-1+ PMN-MDSC enhances immune suppression which promotes glioblastoma multiforme progression. Cancer Manag. Res. 2019;11:7307–7315. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S210545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Si Y, et al. Multidimensional imaging provides evidence for down-regulation of T cell effector function by MDSC in human cancer tissue. Sci. Immunol. 2019;4:eaaw9159. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aaw9159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tavukcuoglu E, et al. Human splenic polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells (PMN-MDSC) are strategically-located immune regulatory cells in cancer. Eur. J. Immunol. 2020;50:2067–2074. doi: 10.1002/eji.202048666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gabrilovich DI. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2017;5:3–8. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-16-0297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fridlender ZG, et al. Polarization of tumor-associated neutrophil phenotype by TGF-beta: “N1” versus “N2” TAN. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:183–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fridlender ZG, et al. Transcriptomic analysis comparing tumor-associated neutrophils with granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells and normal neutrophils. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e31524. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mishalian I, Granot Z, Fridlender ZG. The diversity of circulating neutrophils in cancer. Immunobiology. 2016;222:82–88. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Youn JI, Collazo M, Shalova IN, Biswas SK, Gabrilovich DI. Characterization of the nature of granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells in tumor-bearing mice. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2012;91:167–181. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0311177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Condamine T, Gabrilovich DI. Molecular mechanisms regulating myeloid-derived suppressor cell differentiation and function. Trends Immunol. 2011;32:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trovato R, et al. Immunosuppression by monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells in patients with pancreatic ductal carcinoma is orchestrated by STAT3. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2019;7:255. doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0734-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alshetaiwi H, et al. Defining the emergence of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in breast cancer using single-cell transcriptomics. Sci. Immunol. 2020;5:eaay6017. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aay6017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Song Q, et al. Dissecting intratumoral myeloid cell plasticity by single cell RNA-seq. Cancer Med. 2019;8:3072–3085. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perez C, et al. Immunogenomic identification and characterization of granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2020;136:199–209. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019004537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dinh HQ, et al. Coexpression of CD71 and CD117 identifies an early unipotent neutrophil progenitor population in human bone marrow. Immunity. 2020;53:319–334.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sasidharan Nair V, Saleh R, Toor SM, Alajez NM, Elkord E. Transcriptomic analyses of myeloid-derived suppressor cell subsets in the circulation of colorectal cancer patients. Front. Oncol. 2020;10:1530. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.01530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bader JE, Voss K, Rathmell JC. Targeting metabolism to improve the tumor microenvironment for cancer immunotherapy. Mol. Cell. 2020;78:1019–1033. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.05.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yan D, et al. Polyunsaturated fatty acids promote the expansion of myeloid-derived suppressor cells by activating the JAK/STAT3 pathway. Eur. J. Immunol. 2013;43:2943–2955. doi: 10.1002/eji.201343472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Turbitt WJ, Collins SD, Meng H, Rogers CJ. Increased adiposity enhances the accumulation of MDSCs in the tumor microenvironment and adipose tissue of pancreatic tumor-bearing mice and in immune organs of tumor-free hosts. Nutrients. 2019;11:3012. doi: 10.3390/nu11123012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Al-Khami AA, et al. Exogenous lipid uptake induces metabolic and functional reprogramming of tumor-associated myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6:e1344804. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1344804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hossain F, et al. Inhibition of fatty acid oxidation modulates immunosuppressive functions of myeloid-derived suppressor cells and enhances cancer therapies. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2015;3:1236–1247. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Veglia F, et al. Fatty acid transport protein 2 reprograms neutrophils in cancer. Nature. 2019;569:73–78. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1118-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ugolini A, et al. Polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells limit antigen cross-presentation by dendritic cells in cancer. JCI Insight. 2020;5:e138581. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.138581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou J, Nefedova Y, Lei A, Gabrilovich D. Neutrophils and PMN-MDSC: their biological role and interaction with stromal cells. Semin. Immunol. 2018;35:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2017.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cai TT, et al. LMP1-mediated glycolysis induces myeloid-derived suppressor cell expansion in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13:e1006503. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goffaux G, Hammami I, Jolicoeur M. A dynamic metabolic flux analysis of myeloid-derived suppressor cells confirms immunosuppression-related metabolic plasticity. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:9850. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10464-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patel S, et al. Unique pattern of neutrophil migration and function during tumor progression. Nat. Immunol. 2018;19:1236–1247. doi: 10.1038/s41590-018-0229-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jian SL, et al. Glycolysis regulates the expansion of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in tumor-bearing hosts through prevention of ROS-mediated apoptosis. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8:e2779. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2017.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tannahill GM, et al. Succinate is an inflammatory signal that induces IL-1β through HIF-1α. Nature. 2013;496:238–242. doi: 10.1038/nature11986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.LaGory EL, Giaccia AJ. The ever-expanding role of HIF in tumour and stromal biology. Nat. Cell Biol. 2016;18:356–365. doi: 10.1038/ncb3330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu G, et al. SIRT1 limits the function and fate of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in tumors by orchestrating HIF-1α-dependent glycolysis. Cancer Res. 2014;74:727–737. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Corzo CA, et al. HIF-1α regulates function and differentiation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the tumor microenvironment. J. Exp. Med. 2010;207:2439–2453. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kumar V, et al. CD45 phosphatase inhibits STAT3 transcription factor activity in myeloid cells and promotes tumor-associated macrophage differentiation. Immunity. 2016;44:303–315. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baumann T, et al. Regulatory myeloid cells paralyze T cells through cell-cell transfer of the metabolite methylglyoxal. Nat. Immunol. 2020;21:555–566. doi: 10.1038/s41590-020-0666-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rodriguez PC, et al. Arginase I production in the tumor microenvironment by mature myeloid cells inhibits T-cell receptor expression and antigen-specific T-cell responses. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5839–5849. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Raber PL, et al. Subpopulations of myeloid-derived suppressor cells impair T cell responses through independent nitric oxide-related pathways. Int. J. Cancer. 2014;134:2853–2864. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lu T, et al. Tumor-infiltrating myeloid cells induce tumor cell resistance to cytotoxic T cells in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2011;121:4015–4029. doi: 10.1172/JCI45862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nagaraj S, et al. Altered recognition of antigen is a mechanism of CD8+ T cell tolerance in cancer. Nat. Med. 2007;13:828–835. doi: 10.1038/nm1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.De Sanctis F, et al. The emerging immunological role of post-translational modifications by reactive nitrogen species in cancer microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 2014;5:69. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith C, et al. IDO is a nodal pathogenic driver of lung cancer and metastasis development. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:722–735. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yu J, et al. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells suppress antitumor immune responses through IDO expression and correlate with lymph node metastasis in patients with breast cancer. J. Immunol. 2013;190:3783–3797. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Platten M, Nollen EAA, Rohrig UF, Fallarino F, Opitz CA. Tryptophan metabolism as a common therapeutic target in cancer, neurodegeneration and beyond. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019;18:379–401. doi: 10.1038/s41573-019-0016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang D, Sun H, Wei J, Cen B, DuBois RN. CXCL1 is critical for premetastatic niche formation and metastasis in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2017;77:3655–3665. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-3199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Seubert B, et al. Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMP)-1 creates a premetastatic niche in the liver through SDF-1/CXCR4-dependent neutrophil recruitment in mice. Hepatology. 2015;61:238–248. doi: 10.1002/hep.27378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang Y, Ding Y, Guo N, Wang S. MDSCs: key criminals of tumor pre-metastatic niche formation. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:172. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li P, et al. Lung mesenchymal cells elicit lipid storage in neutrophils that fuel breast cancer lung metastasis. Nat. Immunol. 2020;21:1444–1455. doi: 10.1038/s41590-020-0783-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rayes RF, et al. Primary tumors induce neutrophil extracellular traps with targetable metastasis promoting effects. JCI Insight. 2019;5:e128008. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.128008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Park J, et al. Cancer cells induce metastasis-supporting neutrophil extracellular DNA traps. Sci. Transl Med. 2016;8:361ra138. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aag1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee W, et al. Neutrophils facilitate ovarian cancer premetastatic niche formation in the omentum. J. Exp. Med. 2019;216:176–194. doi: 10.1084/jem.20181170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Najmeh S, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps sequester circulating tumor cells via beta1-integrin mediated interactions. Int. J. Cancer. 2017;140:2321–2330. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cools-Lartigue J, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps sequester circulating tumor cells and promote metastasis. J. Clin. Invest. 2013;123:3446–3458. doi: 10.1172/JCI67484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yang L, et al. DNA of neutrophil extracellular traps promotes cancer metastasis via CCDC25. Nature. 2020;583:133–138. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2394-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Keller L, Pantel K. Unravelling tumour heterogeneity by single-cell profiling of circulating tumour cells. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2019;19:553–567. doi: 10.1038/s41568-019-0180-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Szczerba BM, et al. Neutrophils escort circulating tumour cells to enable cell cycle progression. Nature. 2019;566:553–557. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-0915-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lopez-Soto A, Gonzalez S, Smyth MJ, Galluzzi L. Control of metastasis by NK cells. Cancer Cell. 2017;32:135–154. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Spiegel A, et al. Neutrophils suppress intraluminal NK cell-mediated tumor cell clearance and enhance extravasation of disseminated carcinoma cells. Cancer Discov. 2016;6:630–649. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kumar V, Patel S, Tcyganov E, Gabrilovich DI. The nature of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the tumor microenvironment. Trends Immunol. 2016;37:208–220. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stadtmann A, Zarbock A. CXCR2: from bench to bedside. Front. Immunol. 2012;3:263. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schalper KA, et al. Elevated serum interleukin-8 is associated with enhanced intratumor neutrophils and reduced clinical benefit of immune-checkpoint inhibitors. Nat. Med. 2020;26:688–692. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0856-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yuen KC, et al. High systemic and tumor-associated IL-8 correlates with reduced clinical benefit of PD-L1 blockade. Nat. Med. 2020;26:693–698. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0860-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Highfill SL, et al. Disruption of CXCR2-mediated MDSC tumor trafficking enhances anti-PD1 efficacy. Sci. Transl Med. 2014;6:237ra67. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Greene S, et al. Inhibition of MDSC trafficking with SX-682, a CXCR1/2 inhibitor, enhances NK-cell immunotherapy in head and neck cancer models. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020;26:1420–1431. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-2625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Steele CW, et al. CXCR2 inhibition profoundly suppresses metastases and augments immunotherapy in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2016;29:832–845. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lu Z, et al. Epigenetic therapy inhibits metastases by disrupting premetastatic niches. Nature. 2020;579:284–290. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2054-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vincent J, et al. 5-Fluorouracil selectively kills tumor-associated myeloid-derived suppressor cells resulting in enhanced T cell-dependent antitumor immunity. Cancer Res. 2010;70:3052–3061. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Welters MJ, et al. Vaccination during myeloid cell depletion by cancer chemotherapy fosters robust T cell responses. Sci. Transl Med. 2016;8:334ra52. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad8307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dijkgraaf EM, et al. A phase 1/2 study combining gemcitabine, pegintron and p53 SLP vaccine in patients with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6:32228–32243. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fultang L, et al. MDSC targeting with gemtuzumab ozogamicin restores T cell immunity and immunotherapy against cancers. EBioMedicine. 2019;47:235–246. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lancet JE, et al. A phase 2 study of ATRA, arsenic trioxide, and gemtuzumab ozogamicin in patients with high-risk APL (SWOG 0535) Blood Adv. 2020;4:1683–1689. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019001278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Appelbaum FR, Bernstein ID. Gemtuzumab ozogamicin for acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2017;130:2373–2376. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-09-797712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]