ABSTRACT

Our objective was to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis to assess the effects of total red meat (TRM) intake on glycemic control and inflammatory biomarkers using randomized controlled trials of individuals free from cardiometabolic disease. We hypothesized that higher TRM intake would negatively influence glycemic control and inflammation based on positive correlations between TRM and diabetes. We found 24 eligible articles (median duration, 8 weeks) from 1172 articles searched in PubMed, Cochrane, and CINAHL up to August 2019 that included 1) diet periods differing in TRM; 2) participants aged ≥19 years; 3) included either men or women who were not pregnant/lactating; 4) no diagnosed cardiometabolic disease; and 5) data on fasting glucose, insulin, HOMA-IR, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), C-reactive protein (CRP), or cytokines. We used 1) a repeated-measures ANOVA to assess pre to post diet period changes; 2) random-effects meta-analyses to compare pre to post changes between diet periods with ≥ vs. <0.5 servings (35g)/day of TRM; and 3) meta-regressions for dose-response relationships. We grouped diet periods to explore heterogeneity sources, including risk of bias, using the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute's Quality Assessment of Controlled Interventions Studies. Glucose, insulin, and HOMA-IR values decreased, while HbA1c and CRP values did not change during TRM or alternative diet periods. There was no difference in change values between diet periods with ≥ vs. <0.5 servings/day of TRM [weighted mean differences (95% CIs): glucose, 0.040 mmol/L (−0.049, 0.129); insulin, −0.710 pmol/L (−6.582, 5.162); HOMA-IR, 0.110 (−0.072, 0.293); CRP, 2.424 nmol/L (−1.460, 6.309)] and no dose response relationships (P > 0.2). Risk of bias (85% of studies were fair to good) did not influence results. Total red meat consumption, for up to 16 weeks, does not affect changes in biomarkers of glycemic control or inflammation for adults free of, but at risk for, cardiometabolic disease. This trial was registered at PROSPERO as 2018 CRD42018096031.

Keywords: animal-based protein sources, pork, beef, plant-based protein sources, type 2 diabetes risk factors, adults at risk for cardiometabolic disease

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes (T2DM) and non-congenital cardiovascular diseases (CVD), often collectively referred to as cardiometabolic disease, are comorbid conditions that share behavioral risk factors (1–5). A popular hypothesis is that the combined category of “red and processed meat” intake is a risk factor for cardiometabolic disease development (6, 7). When unprocessed red meat is assessed independently of processed meats in meta-analyses, unprocessed red meat neither increases risks of developing or dying from CVD (8, 9) nor negatively influences CVD risk factors (10, 11), but processed red meat may still impose risks (8, 9). However, associations between red meat types and CVD are more consistent than associations between red meat subtypes and T2DM risk (8, 12), and there is limited compilation of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) assessing effects of red meat subtypes on clinical biomarkers associated with T2DM (13). An investigation of how red meat intake influences risk factors associated with T2DM is needed to complement the aforementioned research on CVD risk factors. This will further our understanding of the influence of red meat intake on the comorbid condition of cardiometabolic disease as a whole.

There are several proposed mechanisms as to why the combined category of “red and processed meat” intake may increase cardiometabolic disease risks in longitudinal, observational studies. The high sodium and nitrate contents of processed red meats likely explain the positive association with CVD risk, and why associations between unprocessed red meat and CVD are largely null (8). Specific to T2DM, observational studies link elevated serum ferritin, advanced glycation end products, trimethylamine N-oxide (14), and red meat-derived zinc and heme-iron (15) to higher insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome in humans. Potential proinflammatory characteristics of red meat, potentially leading to chronic inflammation, may be a ubiquitous risk factor for cardiometabolic disease risk more broadly (16). However, few of these proposed mechanisms have been investigated or confirmed in RCTs.

The objectives of this meta-analysis and meta-regression were to assess the effects of consuming different amounts and types of red meat on fasting biomarkers of glycemic control (primary objective) and inflammation (secondary objective) in adults with no history of cardiometabolic disease. Based on conclusions from observational studies linking higher red meat intake to an increased risk of diabetes (8, 12), we hypothesized that higher total red meat intake would negatively impact changes in glycemic control and inflammation, which are clinical biomarkers associated with T2DM risk. This meta-analysis was designed to complement previously published meta-analyses that assessed the effects of total red meat intake on changes in blood lipids, lipoproteins, and blood pressures (10, 11), and to expand the understanding of how total red meat intake affects comorbid cardiometabolic disease risk factors.

Methods

Registration and procedures

The protocol and methods for this systematically searched meta-analysis were designed a priori and registered at the International Prospective Registrar of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) before the database search was complete (PROSPERO 2018 CRD42018096031; http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?ID=CRD42018096031). The procedures described below 1) adhere to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis guidelines (17); 2) are similar to the Nutrition Evidence Systematic Review methodology used for evidence synthesis in the 2015 Dietary Guidelines for Americans process (18); and 3) meet specifications of a high-quality systematic review according to the AMSTAR (A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews) 2 critical appraisal tool (19). The population, intervention, comparator, outcome, and study design questions are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Description of questions for a systematically searched meta-analysis and meta-regression

| Parameter | Description |

|---|---|

| Population | Men and women who were not pregnant/lactating, ≥19 years old, with no reported diabetes diagnosis or history of cardiovascular disease or events. |

| Intervention | Groups who consumed ≥0.5 servings/day (35 g or 1.25 oz.) of total red meat, referred to as red meat diet period(s). |

| Comparison control | Comparison groups who consumed <0.5 servings/day of total red meat were included in dichotomous meta-analyses and meta-regressions; comparison groups who consumed ≥0.5 servings/day of total red meat were included in meta-regressions only; referred to as alternative diet period(s). |

| Outcome | Changes in metabolic and inflammatory biomarkers associated with type 2 diabetes risk: fasting blood glucose, insulin, HOMA-IR, HbA1c, CRP, IL-6, and TNF-α. |

| Setting | Randomized controlled trials. |

| Research questions | What are effects of consuming ≥ vs. <0.5 servings/day of total red meat on biomarkers of glycemic control and inflammation in adults with no reported cardiometabolic disease? Secondly, does a dose-response relationship exist between total red meat consumption and biomarkers of glycemic control and inflammation in adults with no reported cardiometabolic disease? |

The meta-analysis and meta-regression assessed effects of total red meat consumption on biomarkers of glycemic control and inflammation for adults ≥19 years old and free of cardiometabolic disease. CRP, C-reactive protein; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; HOMA-IR, Homeostatic Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance; IL-6, Interleukin-6; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor alpha.

Search strategy

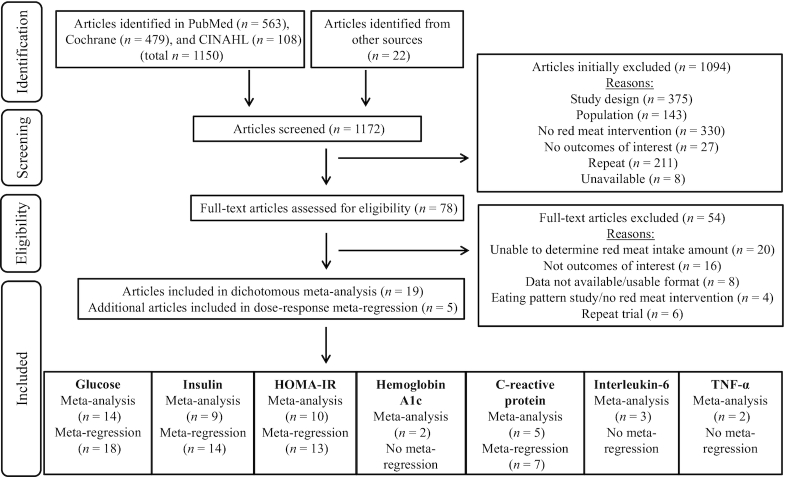

Throughout this meta-analysis, the term “article” refers to the entirety of a publication identified via the search process (Figure 1). More than 1 article can correspond to the same RCT if secondary or tertiary analyses were identified via our search, referenced in the original article, or provided by researchers. Articles were included in this systematically searched meta-analysis if they met the following criteria: 1) had a parallel or crossover RCT design; 2) recruited men and women ≥19 years; 3) excluded women who were pregnant or lactating; 4) excluded individuals with a reported diabetes diagnosis; 5) excluded individuals with a reported CVD diagnosis or previous event; 6) at least 1 diet period during which participants were instructed to consume some amount of total red meat [referred to as the red meat diet period(s)]; 7) at least 1 alternative diet period in which participants were instructed to consume less or no total red meat [referred to as the alternative diet period(s)]; and 8) reported at least 1 outcome variable of interest in a usable data format, including data on fasting glucose, insulin, Homeostatic Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR), glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), C-reactive protein (CRP), or pro-inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin-6 (IL-6) or tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α).

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA (17) diagram for a systematically searched meta-analysis and meta-regression assessing effects of total red meat consumption on biomarkers of glycemic control and inflammation for adults ≥19 years old and free of cardiometabolic disease. More than 1 article can correspond to the same RCT if secondary or tertiary analyses were identified via our search, referenced in the original article, or provided by researchers. Abbreviations: CINAHL, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; HOMA-IR, Homeostatic Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance; PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis; RCT, randomized controlled trial; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor alpha.

Study selection

A systematic review of the literature began 14 May 2018 and was completed 24 August 2018. The PubMed search was updated in August 2019, prior to publication submission, for further articles. A research librarian from Purdue University's Health and Life Sciences Library Division assisted with search term development and database selection. A preliminary database search and a pilot assessment of available data were completed before 14 May 2018, to ensure feasibility of the research question and adequacy of search criteria. Potential articles were identified via the following 3 databases: 1) PubMed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed); 2) Cochrane Library (http://www.cochranelibrary.com); and 3) CINAHL (https://www.ebscohost.com/nursing/products/cinahl-databases/cinahl-complete). Gray literature from the database search results, such as published conference abstracts, was also reviewed for eligibility. Articles included in a previous meta-analysis (10) were screened for potential inclusion as well. Search terms and database results are shown in Table 2. The primary (LEO) and secondary (JEK) authors independently reviewed articles at all stages to determine eligibility. Potentially eligible articles were first identified based on information provided in the title and abstract. Article eligibility was later confirmed by reviewing the full text. Authors were contacted for clarity as needed to determine article eligibility. The senior author (WWC) was consulted if the 2 primary reviewers did not reach a consensus on article eligibility.

TABLE 2.

Search terms and results for a systematically searched meta-analysis and meta-regression

| Source | Search Terms | Filters | Results Yielded |

|---|---|---|---|

| PubMed | "Meat"(Mesh) OR ["Meat"(Mesh) OR "Meat Products"(Mesh) OR "red meat” OR “beef” OR “pork”] AND ["Blood Glucose"(Mesh) OR “Insulin”(Mesh) OR "Insulin Resistance"(Mesh) OR "Metabolic Syndrome X"(Mesh) OR "Hemoglobin A, Glycosylated"(Mesh) OR "Cytokines"(Mesh) OR "C-reactive protein "(Mesh)] | Humans, ≥19 years, English | 563 |

| Cochrane Library | ("Red meat" OR "Meat" OR "Meat Products" OR “Pork" OR "Beef") AND ("Blood Glucose" OR "Insulin" OR "Insulin Resistance" OR "Metabolic Syndrome" OR "Glycosylated Hemoglobin A" OR "Cytokines" OR "C-reactive Protein") NOT ("Pork Insulin" OR "Beef Insulin") | Trials | 479 |

| CINAHL | ("Meat" OR "Meat Products" OR "Red Meat" OR “Pork” OR “Beef”) AND ("Blood Glucose" OR "Insulin" OR "Insulin Resistance" OR "Metabolic Syndrome" OR " Glycosylated Hemoglobin A" OR "Cytokines" OR "C-reactive Protein") NOT (Pork Insulin OR Beef Insulin) | All adult, English | 108 |

| O'Connor et al. (10) | n/a | n/a | 22 |

| TOTAL | 1172 |

The meta-analysis and meta-regression assessed effects of total red meat consumption on biomarkers of glycemic control and inflammation for adults ≥19 years old and free of cardiometabolic disease. Abbreviations: CINAHL, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; n/a, not applicable.

Data extraction

The following data were independently extracted from qualified articles and crosschecked for accuracy: 1) first author name; 2) publication date; 3) PubMed identification number; 4) sample size; 5) group-level participant characteristics; 5) experimental design; 6) diet period duration; 7) eating pattern; 8) method of eating pattern administration; 9) method of measuring eating pattern compliance; 10) amount of total red meat consumed during all diet periods; 11) alternative food source consumed during the alternative low or no red meat diet period(s); 12) species, leanness, and processing degree of red meat consumed; 13) pre, post, and change means and SDs of fasting glucose, insulin, HOMA-IR, HbA1c, CRP, IL-6, and TNF-α; and 14) funding source. Adiponectin data were reported in some articles but were not included due to discrepancies in the analytical methodologies. If not readily available in the published article, corresponding and first authors were contacted up to 3 times to obtain information about the type and amount of red meat, access to data in the most usable format (unadjusted arithmetic mean and SD; adjusted arithmetic means were used when unadjusted data were not obtainable), and other pertinent available unpublished data. The additional data received from authors are presented in Supplemental Table 1.

Definitions

“Red meat” and “processed meat” definitions used for this meta-analysis are consistent with the 2015 Dietary Guidelines for Americans: “all forms of beef, pork, lamb, veal, goat, and non-bird games (e.g., venison, bison, elk)” and “preserved by smoking, curing, salting, and/or the addition of chemical preservatives,” respectively (7). A recommended serving size of red meat is 2–3 ounces (20); therefore, 1 serving and 0.5 servings of red meat were considered to be 2.5 (70 g) and 1.25 ounces (35 g), respectively. The threshold of 0.5 servings/day of total red meat was chosen for this meta-analysis for the following reasons: 1) it is a commonly recommended serving size in heart-healthy eating patterns (21, 22); 2) observational data suggest that consumption greater than 0.5 servings/day of total red meat is associated with increased mortality (23); and 3) it was the same threshold used in a previous meta-analysis (10), which the current meta-analysis was designed to complement. Due to previous concerns of this threshold being too restrictive (24, 25), meta-regressions included articles that would have otherwise been excluded because participants were instructed to consume ≥0.5 servings/day of total red meat during the alternative diet period. Lab value concentrations were converted to SI units (International System of Units) using conversion factors presented by the American Medical Association (26).

Bias assessments

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute's Quality Assessment of Controlled Interventions Studies (NHLBI Tool) was used to evaluate the internal validity of each included article (27). Each article was independently assessed by 2 researchers (LEO and CMC), who then discussed discrepancies until consensus. The NHLBI Tool consists of 14 questions designed to help researchers recognize the limitations of articles, but does not present a quantified numeric score. Therefore, a rating of poor, fair, or good was assigned to each article based on the NHLBI Tool concepts that were most pertinent to high-quality feeding studies. Blinding of participants is not possible in a controlled feeding trial, so NHLBI Tool question 4 (“were study participants and providers blinded to treatment group assignments?”) was omitted.

Funnel plots were visually inspected for non-symmetrical distribution of standard errors around effect estimates to assess publication and small-study biases (i.e., the tendency of intervention effects in articles with a small sample size to differ from articles with a large sample size). Egger's and Begg's tests were used for statistical confirmation, with P < 0.05 implying a potential publication bias (28).

Statistical methods

When articles contained more than 1 red meat or alternative diet period, each comparison was incorporated as an independent point estimate (29). For example, in an article with 1 red meat diet period and 2 alternative diet periods, the 2 alternative diet periods would be compared to the same red meat diet period, resulting in 2 independent point estimates (30–38). Articles were then grouped according to common characteristics among alternative diet periods, to assess the potential heterogeneity induced by this methodological approach.

When raw data were obtained, potentially implausible fasting glucose and insulin values were confirmed as outliers (1.5x interquartile range) and were removed (Supplemental Table 1). Analyses were conducted with and without confirmed outliers, and the analysis without outliers is presented in the main figures and tables. Change value means and SDs were estimated if not available in the published article or provided by the authors. Mean change values were calculated by subtracting the group mean pre value from the group mean post value. Mean change value SDs were estimated as follows (39):

|

(1) |

In this equation, “r” is the correlation between available change values from included articles. Correlations were estimated independently for red meat and alternative diet periods for each outcome variable (Supplemental Table 2).

Pre to post diet period changes and random effects meta-analyses

A repeated-measures ANOVA of pre and post diet period change values (SAS Version 9.4 SAS Institute Inc.) was conducted to summarize the direction of pre to post changes for all outcome variables. Then, the metaan function in Stata SE 15 (Stata Corp) was used to compare pre to post changes of red meat diet periods and alternative diet periods (pre to post change value of red meat diet periods minus pre to post change values of alternative diet periods). The metaan function provided point estimates for each comparison, a summarized weighted mean difference using inverse-variance weighing, and corresponding 95% confidence intervals. A random-effects model was chosen a priori for all main analyses, to account for between-article differences such as geographical location, eating pattern, method of eating pattern administration, and participant characteristics (39). Results presented in figures and tables are ordered by total red meat intake amounts (lowest at the top) of the red meat diet periods. Positive point estimates indicate lesser pre to post changes during the red meat diet period, compared to the alternative diet period. Negative point estimates indicate lesser pre to post changes during the alternative diet period, compared to the red meat diet period. A 95% confidence interval that does not overlap 0 is significant.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted to account for possible underweighting of articles in random-effects models (39). Model selection is also often chosen post hoc based on a chi-square test of heterogeneity (τ2P > 0.05 indicates the use of a fixed-effect rather than random-effects model). As stated previously, random-effects models were chosen a priori and are presented in the main analyses, but secondary post hoc fixed-effect analyses (when τ2P > 0.05) were also performed.

In the case of multiple comparisons within 1 article, the main results represent analyses in which SDs are imputed with a correlation factor of 0. Sensitivity analyses were conducted, imputing SDs with a correlation factor of 0.5 to account for potential correlation between groups (39). Similarly, in the case of crossover trials, the main analyses incorporated crossovers as parallel designs (i.e., for articles that were crossover design studies, each phase of the crossover study was treated as if it was an independent arm of a parallel study) by imputing SDs with a correlation factor of 0 (29). Sensitivity analyses were conducted by imputing SDs with a correlation factor of 0.99 to approximate a paired analysis, in order to account for the individuals completing both red meat and alternative diet periods (29).

Subgroup analyses

Red meat and alternative diet period comparisons were divided into groups with similar characteristics to reduce potential heterogeneity in dichotomous analyses. Analyses were performed on groups with 1) intentional weight loss; 2) intentional weight maintenance; 3) higher protein (achieved via increased red meat) vs. higher carbohydrate eating patterns; 4) eating patterns with similar percentages of total energy from protein for both the red meat and alternative diet periods; 5) alternative diet periods using animal protein sources; 6) alternative diet periods using plant food sources; 7) basal heart-healthy eating patterns; 8) lean red meat; 9) unprocessed red meat; 10) lean and unprocessed red meat; 11) overweight or obese participants; and 12) articles with “good” and “fair” NHLBI Tool scores. Subgroup analyses were not performed on HbA1c, IL-6, or TNF-α due to small numbers of eligible articles.

Dose-response meta-regression

The metareg function in Stata SE 15 (Stata Corp) was used for random-effects meta-regressions to assess correlations between red meat intake and outcome variables for all red meat and alternative diet periods in which participants were instructed to consume any amount of red meat. The aim of these analyses was to assess effects of a wider range of red meat intake quantities on pre to post diet period changes in glucose, insulin, HOMA-IR, and CRP. Meta-regressions were not performed on HbA1c, IL-6, or TNF-α due to small numbers of eligible articles. Models were adjusted for intervention duration (in days), group-level mean baseline age, group-level mean baseline body mass index, and group-level mean baseline value of outcome variable of interest. Random intercept mixed-effects were used to account for covariance structures of point estimates from articles with multiple comparisons or crossover design (40). Hence, independence between point estimates within articles was not assumed.

Results

Search results

Of 1172 articles screened, a total of 1094 studies were initially excluded for not meeting inclusion criteria. Of those 1094 studies excluded, 211 were duplicates and 8 were unavailable. Of the 78 full-text articles assessed for eligibility (see excluded full text articles as well as reasons for exclusion in Supplemental Table 3), 19 studies were eligible to be included in the random-effects meta-analyses and an additional 5 studies (for a total of 24) were eligible to be included in the meta-regressions (Figure 1). There were 20 unique RCTs among the 24 identified articles (Supplemental Table 4), therefore some RCTs have more than 1 reference.

Article characteristics

Of the 15 RCTs included in the dichotomous ≥ vs. <0.5 servings/day of total red meat meta-analyses: 7 were parallel designs (30, 41–43, 31, 44, 45, 32); 8 were crossover designs (33, 34, 46, 47, 35, 36, 48–52); 6 included intentional weight loss diet periods (30, 41, 31, 44, 45, 32); 10 included intentional weight maintenance diet periods (42, 43, 32–34, 46, 47, 35, 36, 48–52); 5 included diet periods which compared higher vs. lower total protein intakes (41–43, 31, 32, 49); 12 included diet periods that had similar macronutrient distributions (30, 31, 44, 45, 32–34, 46, 47, 35, 36, 48, 50–52); 8 included alternative diet periods that used animal source foods, such as fish, poultry, eggs, and/or dairy, to replace red meat intake (31–34, 46–48, 50–52); 9 included alternative diet periods that used plant source foods, such as soy, legumes, or grains, to replace red meat intake (30, 41, 31, 44, 32, 35, 36, 49); 7 prescribed healthy eating patterns (45, 32, 47, 35, 36, 48, 50–52); 10 specified the use of lean red meat (30, 41–43, 31, 45, 32, 47, 48, 50–52); 10 specified the use of unprocessed red meat (42, 43, 31, 45, 32–34, 47–52); 8 specified the use of lean and unprocessed red meat (42, 43, 31, 45, 32, 47, 48, 50–52); and 13 recruited overweight or obese participants (30, 41–43, 31, 44, 45, 32–34, 47, 35, 36, 48, 50–52). Total red meat consumption ranged from 71 to 215 (median = 122) g/day during the red meat diet periods. The intervention lengths ranged from 3 to 16 (median = 8) weeks. All relevant information on each RCT, including funding sources, are described in Supplemental Table 4.

Of the additional 5 studies included in the meta-regressions, 2 were parallel designs (53, 54); 3 were crossover designs (55, 37, 38); all 5 prescribed weight maintenance; 2 included diet periods that compared higher vs. lower total protein intakes (54, 37); 3 included alternative diet periods that were similar in macronutrient distributions (55, 37, 38); 4 included alternative diet periods that used animal source foods, such as fish, poultry, eggs, and/or dairy, to replace red meat intake (37, 38); 3 included alternative diet periods that used plant source foods, such as soy or carbohydrates, to replace red meat intake (54, 55, 38); 1 used a heart-healthy eating pattern (37); 3 specified the use of lean red meat (53, 54, 37); 1 specified the use of unprocessed red meat (37); 1 specified the use of high-fat, processed red meat during the red meat diet period (38); and 4 specified recruiting overweight or obese participants (53, 54, 37, 38).

The total red meat consumption of all 20 studies ranged from 71 to 238 (median = 131) g/day during the red meat diet period. The intervention lengths of all 20 studies ranged from 2 to 24 (median = 6) weeks (Supplemental Table 4).

Bias assessment

There were 7 studies rated as “good,” 10 as “fair,” and 3 as “poor” (Supplemental Table 5). Randomization, allocation, and blinding methods were most often not reported. The “poor” studies generally did not report power analyses for their described primary outcome of interest or were not a priori registered in a clinical trial database.

There was no evidence of publication bias or small-study effects, as indicated by symmetrical funnel plots and supported by Egger's and Begg's test P values >0.05 (Supplemental Figures 1–4).

Results of meta-analyses

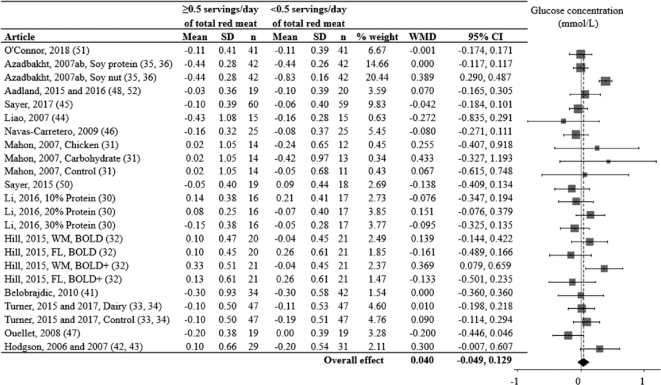

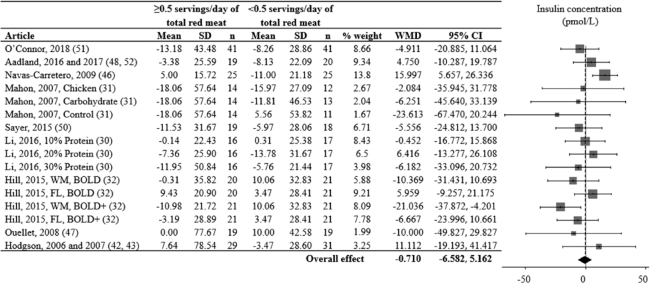

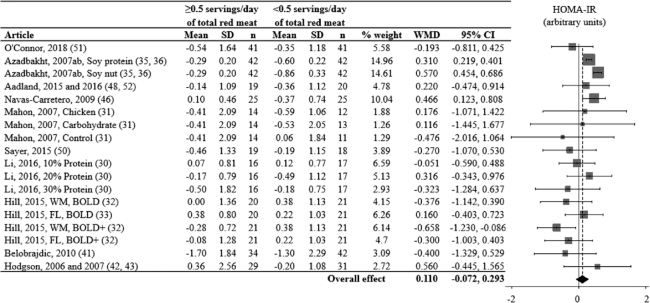

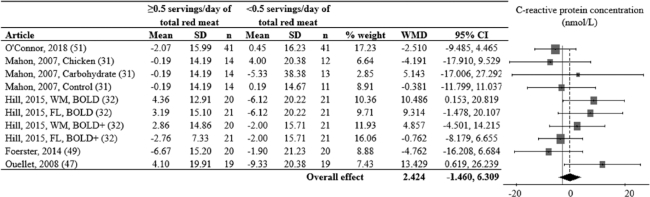

Glucose, insulin, and HOMA-IR values decreased from pre to post in both red meat and alternative diet periods, while HbA1c, CRP, IL-6, and TNF-α values did not change (Supplemental Figures 5 and 6). Random-effects models assessing relative differences of change values between red meat and alternative diet periods did not support a differential effect of consuming ≥ vs. <0.5 servings/day of total red meat on glucose (Figure 2), insulin (Figure 3), HOMA-IR (Figure 4), CRP (Figure 5), HbA1c, IL-6, or TNF-α (Table 3).

FIGURE 2.

Effects of consuming ≥ vs. <0.5 servings/day of total red meat on blood glucose concentration (mmol/L) for adults ≥19 years old and free of cardiometabolic disease. Random-effects analysis, I² = 68; I² 95% confidence interval = 51; 79%. Data are shown in descending order from the smallest to largest amount of total red meat consumed during the red meat diet period. The differences in pre to post diet period change values were calculated as pre to post change value of the red meat diet minus the pre to post change value of the alternative diet period. Positive point estimates indicate lesser pre to post changes during the red meat diet period, compared to the alternative diet period. Negative point estimates indicate lesser pre to post changes during the alternative diet period, compared to the red meat diet period. Pre to post mean change values for red meat and alternative diet periods were assessed via repeated-measures ANOVA and are presented in Supplemental Figure 1. A 95% confidence interval that does not overlap 0 is significant. Divide mmol/L by 0.0555 for mg/dL. Abbreviations: BOLD, Beef in an Optimal Lean Diet; BOLD+, Beef in an Optimal Lean Diet Plus Protein; FL, free-living weight loss phase; WM, controlled weight maintenance period; WMD, weighted mean difference.

FIGURE 3.

Effects of consuming ≥ vs. <0.5 servings/day of total red meat per day on blood insulin concentration (pmol/L) for adults ≥19 years old and free of cardiometabolic disease. Random-effects analysis, I² = 28; I² 95% confidence interval = 0; 61%. Data are shown in descending order from the smallest to largest amount of red meat consumed during the red meat diet period. The difference in pre to post diet period change values were calculated as pre to post change value of the red meat diet minus the pre to post change value of the alternative diet period. Positive point estimates indicate lesser pre to post changes during the red meat diet period, compared to the alternative diet period. Negative point estimates indicate lesser pre to post changes during the alternative diet period, compared to the red meat diet period. Pre to post mean change values for the red meat and alternative diet periods were assessed via repeated-measures ANOVA and are presented in Supplemental Figure 1. A 95% confidence interval that does not overlap 0 is significant. Divide pmol/L by 6.945 for μIU/mL. Abbreviations: BOLD, Beef in an Optimal Lean Diet; BOLD+, Beef in an Optimal Lean Diet Plus Protein; FL, free-living weight loss phase; WM, controlled weight maintenance period; WMD, weighted mean difference.

FIGURE 4.

Effects of consuming ≥ vs. <0.5 servings/day of total red meat per day on HOMA-IR (arbitrary units) for adults ≥19 years old and free of cardiometabolic disease. Random-effects analysis, I² = 64; I² 95% confidence interval = 41; 78%. Data are shown in descending order from the smallest to largest amount of red meat consumed during the red meat diet period. The difference in pre to post diet period change values were calculated as pre to post change value of the red meat diet minus the pre to post change value of the alternative diet period. Positive point estimates indicate lesser pre to post changes during the red meat diet period, compared to the alternative diet period. Negative point estimates indicate lesser pre to post changes during the alternative diet period. compared to the red meat diet period. Pre to post mean change values for red meat and alternative diet periods were assessed via repeated-measures ANOVA and are presented in Supplemental Figure 1. A 95% confidence interval that does not overlap 0 is significant. Abbreviations: BOLD, Beef in an Optimal Lean Diet; BOLD+, Beef in an Optimal Lean Diet Plus Protein; FL, free-living weight loss phase; WM, controlled weight maintenance period; WMD, weighted mean difference.

FIGURE 5.

Effects of consuming ≥ vs. <0.5 servings/day of total red meat per day on C-reactive protein (nmol/L) for adults ≥19 years old and free of cardiometabolic disease. Random-effects analysis, I² = 27; I² 95% confidence interval = 0; 64%. Data are shown in descending order from the smallest to largest amount of red meat consumed during the red meat diet period. The difference in pre to post diet period change values were calculated as pre to post change value of the red meat diet minus the pre to post change value of the alternative diet period. Positive point estimates indicate lesser pre to post changes during the red meat diet period, compared to the alternative diet period. Negative point estimates indicate lesser pre to post changes during the alternative diet period, compared to the red meat diet period. Pre to post mean change values for red meat and alternative diet periods were assessed via repeated-measures ANOVA and are presented in Supplemental Figure 2. A 95% confidence interval that does not overlap 0 is significant. Abbreviations: BOLD, Beef in an Optimal Lean Diet; BOLD+, Beef in an Optimal Lean Diet Plus Protein; FL, free-living weight loss phase; WM, controlled weight maintenance period; WMD, weighted mean difference.

TABLE 3.

Results of random-effects meta-analyses for HbA1c, IL-6, and TNF-α

| Outcome | n | Weighted mean difference (95% CI) | I2 % (95% CI) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HbA1c (%) | 2 | 0.073 (−0.154, 0.300) | 81 (18, 95) | (42, 43, 45) |

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | 3 | −0.166 (−0.715, 0.384) | 69 (0, 91) | (47, 50, 51) |

| TNF-α (μg/mL) | 2 | −0.958 (−3.127, 1.211) | 90 (64, 97) | (47, 50) |

The meta-analyses assessed effects of consuming ≥ vs. <0.5 servings/day of total red meat on biomarkers of glycemic control and inflammation for adults ≥19 years old and free of cardiometabolic disease. The n column indicates the number of point estimate comparisons for each outcome. More than 1 article can correspond to the same randomized controlled trial if secondary or tertiary analyses were identified via our search, referenced in the original article, or provided by researchers.

Abbreviations: HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; IL-6, interleukin-6; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor aplha.

Subgroup analyses did not support a differential change of consuming ≥ vs. <0.5 servings/day of total red meat on glucose, insulin, HOMA-IR, or CRP within groups of studies assessing intentional weight loss or weight maintenance; alternative diet periods which used animal source foods, such as fish, poultry, eggs, and/or dairy, to replace red meat intake; alternative diet periods which used plant source foods, such as soy or carbohydrates, to replace red meat intake; basal heart-healthy eating patterns; the consumption of lean red meat only, unprocessed red meat only, or lean unprocessed red meat only; participants that were overweight or obese; or articles graded “good” and “fair” based on the NHLBI Tool (Supplemental Table 6). Among comparisons with higher protein eating patterns achieved via replacing carbohydrates with red meat, consuming ≥0.5 servings/day of total red meat decreased insulin concentrations more than consuming <0.5 servings/day of total red meat. Among comparisons with similar macronutrient distributions, consuming ≥0.5 servings/day of total red meat resulted in lesser decreases of HOMA-IR, compared to consuming <0.5 servings/day of total red meat (Supplemental Table 6). Post hoc fixed-effect analyses (Supplemental Table 7) and sensitivity analyses accounting for multiple comparisons or crossover designs did not influence the results.

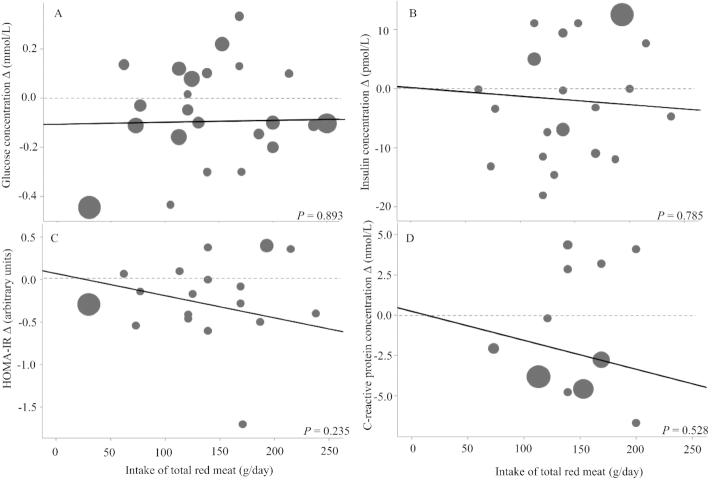

Dose-response meta-regressions

There was no evidence of a dose-response relationship between total red meat intake and pre to post changes in fasting blood glucose, insulin, HOMA-IR, or CRP values. The duration of intervention, group-level mean baseline age, group-level mean baseline body mass index, and group-level mean baseline value of outcome variable of interest were not significant covariates for any outcome variable (other than body mass index and changes in glucose; Supplemental Table 8); therefore, these variables were removed for the presented results (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

Meta-regression of total red meat intake and biomarkers of glycemic control and inflammation for adults ≥19 years old and free of cardiometabolic disease. Data points are weighted changes from pre to post for (A) glucose, (B) insulin, (C) HOMA-IR, and (D) C-reactive protein from all red meat–consuming groups or phases. P values represent red meat intake beta coefficients in a random-effects meta-regression model.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis of RCTs assessing effects of total red meat intake on glycemic control and inflammation biomarkers in adults who are disease-free but may be at risk of developing CVD or T2DM at a later life stage. We hypothesized that total red meat intake would have a negative impact on these outcomes, based on positive associations between unprocessed and processed red meat intake and diabetes incidences (8, 12). However, our results showed no effect of total red meat intake on fasting glucose, insulin, HOMA-IR, HbA1c, CRP, IL-6, or TNF-α concentrations from RCTs of up to 16 weeks in duration. It is important to note that research participants were asked to consume lean and unprocessed red meat in most of the included articles, so evidence regarding independent effects of processed or fatty red meat intake on these outcomes is lacking. The present meta-analysis aligns with our previous meta-analysis of RCTs, which showed no effect of total red meat (but mostly unprocessed beef and pork) consumption on short-term changes in blood lipid, lipoprotein, or blood pressure measurements (10, 11). Overall, red meat intake does not independently influence changes in cardiometabolic disease risk factors in the short term. For those who choose to consume red meat, red meat (as with all other protein-rich food sources) should be consumed in the context of a healthy eating pattern high in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains and within energy needs to reduce the cardiometabolic disease risk (7, 56).

There is no conclusive evidence to support a “one-size-fits-all” dietary strategy to improve glycemic control and insulin resistance. Experimental and observational data, summarized by the American Diabetes Association, show that the adoption of eating patterns with both low (such as Mediterranean-style or dietary approaches to stop hypertension–style diets) and high red meat intakes (such as low- and very low–carbohydrate eating patterns) improve HbA1c values, body weights, and diabetes risks (57). Yet, there is often much scientific debate over what protein sources should be recommended to consumers for diabetes and overall cardiometabolic disease prevention. Our subgroup analyses showed no increased benefit of replacing red meat with other animal-based (such as poultry) or plant-based (such as soy) protein sources on biomarkers of glycemic control or inflammation. Articles in which research participants were instructed to consume a healthy eating pattern showed improvements in cardiometabolic risk factor panels independent of the main protein source consumed (45, 32, 47, 35, 36, 48, 50–52, 37). This was particularly apparent for interventions that included energy-restricted eating patterns that resulted in body weight improvements (30, 41, 43, 31, 44, 45, 32). Consuming a nutrient-dense eating pattern while achieving a healthier body weight seems to improve glycemic control and cardiometabolic health, independent of the main protein source consumed.

Insulin resistance induced by chronic inflammation is a proposed mechanism to explain positive associations between red meat intake and diabetes risk (14, 16). Red meat contains bioavailable heme-iron, which has the potential to increase iron storage and advanced glycation end products, thus generating free radicals and inducing inflammation (14, 16). Results from this meta-analysis of RCTs showed no evidence of an effect of total red meat intake on short-term changes in inflammatory markers. Further, there are few human studies that suggest a positive association between habitual red meat intake and chronic inflammation. Results from the Multiethnic Cohort Study showed that excess body weight can mediate and nullify the relationship between red meat intake and chronic inflammation (58). Results from the Nurses’ Health Study showed that red and processed meat consumed in an eating pattern that is also low in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains can strengthen the relationship between red meat intake and chronic inflammation (59). Most humans have an innate biological ability to regulate circulatory iron concentrations when dietary iron fluctuates, and are thus able to minimize free radical generation and subsequent inflammation (60). Therefore, it is unlikely that chronic inflammation can solely explain positive associations between red meat intake and diabetes risk.

Our results from RCTs showed no effect of total red meat intake on risk factors associated with T2DM, while observational data suggest positive associations between red meat intake and incident diabetes (8, 12). Aside from different dependent variables, the discrepancy between these 2 types of study designs may be due to differences in the distribution of lifestyle factors that confound the relationship between red meat intake and diabetes risk. In US cohorts, those who consume high amounts of red meat are more likely to smoke; be inactive; eat fewer fruits, vegetables, and fiber; eat more saturated fat and added sugars; and have a higher body mass index, compared to those who consume little to no red meat (23, 58, 61, 62). These lifestyle choices are also strong modifiable risk factors for T2DM, as identified by the American Diabetes Association. It is difficult to assess associations between red meat intake and diabetes completely independent of these confounding behaviors in observational cohort studies due to measurement error, unmeasured confounding, and other types of uncertainty (63–65). Randomization in intervention trials, when done properly, more evenly distributes confounders and can better target direct effects of dietary manipulations, such as red meat intake amounts, on risk factors that are associated with the development of T2DM. Ideal, long-term RCTs assessing effects of red meat consumption on incident diabetes are not feasible. Therefore, it is critical to balance the strengths and limitations of long-term observational and short-term experimental studies when translating research into practical dietary guidance.

As with all meta-analyses, the strength of our conclusions is dictated by the quality of the included articles. Based on the NHLBI risk of bias assessment, 85% of the included articles were ranked fair or good, and there was no evidence of publication bias. The included empirical articles were not intended to identify those mechanisms by which red meat intake influences biomarkers of glycemic control or inflammation. Further, the included articles reported the effects of consuming mainly unprocessed beef and pork, limiting the ability to explore the metabolic effects of species subtypes, fat content, or meat processing. The main analyses assessed effects of consuming ≥ vs. <0.5 servings/day of total red meat. This is a commonly recommended threshold for red meat intake in healthy eating patterns, but is quite restrictive. Therefore, we further explored our data with statistical sensitivity analyses and relevant subgroup analyses, and we conducted meta-regressions to assess potential dose-response relationships. We did not correct for multiple comparisons due to largely null results.

The health outcomes assessed in this meta-analysis were intermediate risk factors associated with T2DM over a median of 8 weeks, rather than incident diabetes cases over the course of decades. A median of 8 weeks may not be long enough to see differential effects of red meat vs. alternative foods on these changes in these outcomes. Our results showed statistically significant changes in fasting glucose, insulin, HOMA-IR, and CRP values from pre to post diet periods; however, these changes were small in magnitude. The clinical relevance of these changes in relation to changes in diabetes risks are unknown. It's been previously noted that changes in eating patterns alone have minimal influence markers of glycemic control in the absence of weight loss or physical activity (66, 67). Longer-term RCTs are needed to see whether the observed changes in T2DM risk factors persist over a longer time duration.

Our current meta-analysis and past meta-analyses of RCTs (10, 11) show that red meat intake (mainly unprocessed beef and pork) does not affect short-term changes in cardiometabolic disease risk factors for individuals who are free of, but at risk for, CVD or T2DM. Further, sub-analyses support that consuming a nutrient-dense, healthy eating pattern and achieving a lower body weight improves cardiometabolic disease risk factors, independent of the amount of red meat consumed. This research, when considered as part of the larger array of diverse scientific evidence, provides causal insight that can be used to inform public health recommendations regarding red meat–containing eating patterns and cardiometabolic disease risks.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Bethany McGowan from Purdue University's Health and Life Sciences Library Division for support in planning the search and choosing search terms, and Dr. Bruce Craig from Purdue University's Department of Statistics for advising on the data analysis plan.

The authors' responsibilities were as follows—LEO, JEK, and WWC: designed the research; LEO and JEK: conducted the search and completed data collection; LEO, CMC, and WZ: analyzed data; LEO: wrote the manuscript with editorial assistance from all coauthors; WWC: had primary responsibility for final content; and all authors: read and approved the final manuscript.

Notes

This study was funded by The Pork Checkoff and Purdue University's Bilsland Dissertation Fellowship (LEO). The funder had no role in the design or conduct of the study or the analysis or interpretation of data.

Author disclosures: LEO received honoraria and travel to present related research as a graduate student from the National Cattlemen's Beef Association. During the time this research was conducted, WWC received funding for research grants, travel, or honoraria for scientific presentations or consulting services from the following organizations: National Cattlemen's Beef Association, National Pork Board, National Dairy Council, North Dakota Beef Commission, Foundation for Meat and Poultry Research and Education, Barilla Group, New York Beef Council, and North American Meat Institute. All the other authors report no conflicts of interest.

Supplemental Tables 1–8 and Supplemental Figures 1–6 are available from the “Supplementary data” link in the online posting of the article and from the same link in the online table of contents at https://academic.oup.com/advances.

LEO and JEK moved from Purdue's Department of Nutrition Science to the other noted institutions at different stages during the manuscript development.

Abbreviations used: CINAHL, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; CRP, C-reactive protein; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; HOMA-IR, Homeostatic Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance; IL-6, Interleukin-6; NHLBI Tool, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute's Quality Assessment of Controlled Interventions Studies; PROSPERO, International Prospective Registrar of Systematic Reviews; RCT, randomized controlled trial; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor alpha; TRM, total red meat; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Contributor Information

Lauren E O'Connor, Cancer Prevention Fellowship Program, Division of Cancer Prevention, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Rockville, MD, USA; Department of Nutrition Science, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, USA.

Jung Eun Kim, Department of Nutrition Science, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, USA; Department of Food Science and Technology, National University of Singapore, Singapore.

Caroline M Clark, Department of Nutrition Science, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, USA.

Wenbin Zhu, Department of Statistics, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, USA.

Wayne W Campbell, Department of Nutrition Science, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, USA.

References

- 1. American Heart Association . Cardiovascular disease and diabetes. [Internet]. [Accessed 2020 Aug 23]. Available from: http://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/diabetes/why-diabetes-matters/cardiovascular-disease–diabetes [Google Scholar]

- 2. American Heart Association . Understand your risk of heart attack. [Internet]. [Accessed 2020 Aug 23]. Available from: http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/Conditions/HeartAttack/UnderstandYourRiskofHeartAttack/Understand-Your-Risk-of-Heart-Attack_UCM_002040_Article.jsp#.Vs3xqH0rJpg [Google Scholar]

- 3. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases . Preventing type 2 diabetes. [Internet]. [Accessed 2020 Aug 23]. Available from: https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/diabetes/overview/preventing-type-2-diabetes [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vasudevan AR, Ballantyne CM. Cardiometabolic risk assessment: an approach to the prevention of cardiovascular disease and diabetes mellitus. Clin Cornerstone. 2005;7(2–3):7–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Castro JP, El-Atat FA, McFarlane SI, Aneja A, Sowers JR. Cardiometabolic syndrome: pathophysiology and treatment. Current Science Inc. 2003;5(5):393–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. American Diabetes Association . Prevention or delay of type 2 diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes-2018. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(Suppl 1):S51–S4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. United States Department of Agriculture and Department of Health and Human Services . 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 8th ed. Washington (DC): US Government Printing Office; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Micha R, Michas G, Mozaffarian D. Unprocessed red and processed meats and risk of coronary artery disease and type 2 diabetes–an updated review of the evidence. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2012;14(6):515–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. van den Brandt PA. Red meat, processed meat, and other dietary protein sources and risk of overall and cause-specific mortality in The Netherlands Cohort Study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2019;34(4):351–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. O'Connor LE, Kim JE, Campbell WW. Total red meat intake of ≥0.5 servings/d does not negatively influence cardiovascular disease risk factors: A systemically searched meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;105(1):57–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Guasch-Ferre M, Satija A, Blondin SA, Janiszewski M, Emlen E, O'Connor LE, Campbell WW, Hu FB, Willett WC, Stampfer MJ. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of red meat consumption in comparison with various comparison diets on cardiovascular risk factors. Circulation. 2019;139(15):1828–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Aune D, Ursin G, Veierod MB. Meat consumption and the risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Diabetologia. 2009;52(11):2277–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schwingshackl L, Schlesinger S, Devleesschauwer B, Hoffmann G, Bechthold A, Schwedhelm C, Iqbal K, Knuppel S, Boeing H. Generating the evidence for risk reduction: a contribution to the future of food-based dietary guidelines. Proc Nutr Soc. 2018;77(4):432–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kim Y, Keogh J, Clifton P. A review of potential metabolic etiologies of the observed association between red meat consumption and development of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Metabolism. 2015;64(7):768–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. de Oliveira Otto MC, Alonso A, Lee D, Delclos GL, Bertoni AG, Jiang R, Lima JA, Symanski E, Jacobs DR, Nettleton AJ. Dietary intakes of zinc and heme iron from red meat, but not from other sources, are associated with greater risk of metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease. J Nutr. 2012;142(3):526–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kuipers RS, Pruimboom L. Short comment on "A review of potential metabolic etiologies of the observed association between red meat consumption and development of type 2 diabetes mellitus," by Yoona Kim, Jennifer Keogh, Peter Clifton. Metabolism. 2016;65(1):e3–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;8(5):336–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. United States Department of Agriculture and Department of Health and Human Services . Scientific Report of the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. [Internet]. [Accessed 2020 Aug 23]. Available from: https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015-scientific-report/PDFs/Scientific-Report-of-the-2015-Dietary-Guidelines-Advisory-Committee.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, Moher D, Tugwell P, Welch V, Kristjansson Eet al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. American Heart Association . Meat, poultry, and fish. [Internet]. [Accessed 2020 Aug 23]. Available from: http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/HealthyLiving/HealthyEating/Nutrition/Meat-Poultry-and-Fish_UCM_306002_Article.jsp#.V37iHmNMLww [Google Scholar]

- 21. Karanja NM, Obarzanek E, Lin PH, McCullough ML, Phillips KM, Swain JF, Champagne CM, Hoben KP; DASH Collaborative Research Group . Descriptive characteristics of the dietary patterns used in the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension Trial. J Am Diet Assoc. 1999;99(Suppl 8):S19–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Swain JF, McCarron PB, Hamilton EF, Sacks FM, Appel LJ. Characteristics of the diet patterns tested in the optimal macronutrient intake trial to prevent heart disease (OmniHeart): options for a heart-healthy diet. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108(2):257–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pan A, Sun Q, Bernstein AM, Schulze MB, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Hu FB. Red meat consumption and mortality: results from 2 prospective cohort studies. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(7):555–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Satija A, Malik VS, Willett WC, Hu FB. Meta-analysis of red meat intake and cardiovascular risk factors: methodologic limitations. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;105(6):1567–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. O'Connor LE, Kim JE, Campbell WW. Reply to A Satija et al. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;105(6):1568–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. American Medical Association . SI conversion calculator. [Internet]. [Accessed 2020 Aug 23]. Available from: http://www.amamanualofstyle.com/page/si-conversion-calculator [Google Scholar]

- 27. National Heart Lung and Blood Institute . Study quality assessment tools. [Internet]. [Accessed 2020 Aug 23]. Available from: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools [Google Scholar]

- 28. Harbord RM, Harris RJ, Sterne JAC. Updated tests for small-study effects in meta-analyses. The Stata Journal. 2009;9(2):197–210. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions, version 5.1.0. [Internet]. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. [Accessed 2020 Aug 23]. Available from: www.handbook.cochrane.org. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Li J, Armstrong CL, Campbell WW. Effects of dietary protein source and quantity during weight loss on appetite, energy expenditure, and cardio-metabolic responses. Nutrients. 2016;8(2):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mahon AK, Flynn MG, Stewart LK, McFarlin BK, Iglay HB, Mattes RD, Lyle RM, Considine RV, Campbell WW. Protein intake during energy restriction: effects on body composition and markers of metabolic and cardiovascular health in postmenopausal women. J Am Coll Nutr. 2007;26(2):182–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hill AM, Harris Jackson KA, Roussell MA, West SG, Kris-Etherton PM. Type and amount of dietary protein in the treatment of metabolic syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;102(4):757–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Turner KM, Keogh JB, Clifton PM. Red meat, dairy, and insulin sensitivity: a randomized crossover intervention study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;101(6):1173–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Turner KM, Keogh JB, Meikle PJ, Clifton PM. Changes in lipids and inflammatory markers after consuming diets high in red meat or dairy for four weeks. Nutrients. 2017;9(8):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Azadbakht L, Kimiagar M, Mehrabi Y, Esmaillzadeh A, Hu FB, Willett WC. Soy consumption, markers of inflammation, and endothelial function: a cross-over study in postmenopausal women with the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(4):967–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Azadbakht L, Kimiagar M, Mehrabi Y, Esmaillzadeh A, Padyab M, Hu FB, Willett WC. Soy inclusion in the diet improves features of the metabolic syndrome: a randomized crossover study in postmenopausal women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85(3):735–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Roussell MA, Hill AM, Gaugler TL, West SG, Vanden Heuvel JP, Alaupovic P, Gillies PJ, Kris-Etherton PM. Beef in an optimal lean diet study: effects on lipids, lipoproteins, and apolipoproteins. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95(1):9–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Thorning TK, Raziani F, Bendsen NT, Astrup A, Tholstrup T, Raben A. Diets with high-fat cheese, high-fat meat, or carbohydrate on cardiovascular risk markers in overweight postmenopausal women: a randomized crossover trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;102(3):573–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Borenstein M, Higgins JPT, Rothenstein HR. Introduction to meta-analysis. Chichester (West Sussex, United Kingdom): John Wiley and Sons, Ltd; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Galecki A, Burzykowski T. Linear mixed-effects models using R. New York (NY): Springer; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Belobrajdic DP, Frystyk J, Jeyaratnaganthan N, Espelund U, Flyvbjerg A, Clifton PM, Noakes M. Moderate energy restriction-induced weight loss affects circulating IGF levels independent of dietary composition. Eur J Endocrinol. 2010;162(6):1075–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hodgson JM, Burke V, Beilin LJ, Puddey IB. Partial substitution of carbohydrate intake with protein intake from lean red meat lowers blood pressure in hypertensive persons. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83(4):780–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hodgson JM, Ward NC, Burke V, Beilin LJ, Puddey IB. Increased lean red meat intake does not elevate markers of oxidative stress and inflammation in humans. J Nutr. 2007;137(2):363–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Liao FH, Shieh MJ, Yang SC, Lin SH, Chien YW. Effectiveness of a soy-based compared with a traditional low-calorie diet on weight loss and lipid levels in overweight adults. Nutrition. 2007;23(7–8):551–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sayer RD, Speaker KJ, Pan Z, Peters JC, Wyatt HR, Hill JO. Equivalent reductions in body weight during the Beef WISE study: beef's role in weight improvement, satisfaction and energy. Obes Sci Pract. 2017;3(3):298–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Navas-Carretero S, Perez-Granados AM, Schoppen S, Vaquero MP. An oily fish diet increases insulin sensitivity compared to a red meat diet in young iron-deficient women. Br J Nutr. 2009;102(4):546–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ouellet V, Weisnagel SJ, Marois J, Bergeron J, Julien P, Gougeon R, Tchernof A, Holub BJ, Jacques H. Dietary cod protein reduces plasma C-reactive protein in insulin-resistant men and women. J Nutr. 2008;138(12):2386–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Aadland EK, Graff IE, Lavigne C, Eng O, Paquette M, Holthe A, Mellgren G, Madsen L, Jacques H, Liaset B. Lean seafood intake reduces postprandial C-peptide and lactate concentrations in healthy adults in a randomized controlled trial with a crossover design. J Nutr. 2016;146(5):1027–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Foerster J, Maskarinec G, Reichardt N, Tett A, Narbad A, Blaut M, Boeing H. The influence of whole grain products and red meat on intestinal microbiota composition in normal weight adults: a randomized crossover intervention trial. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e109606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sayer RD, Wright AJ, Chen N, Campbell WW. Dietary approaches to stop hypertension diet retains effectiveness to reduce blood pressure when lean pork is substituted for chicken and fish as the predominant source of protein. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;102(2):302–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. O'Connor LE, Paddon-Jones D, Wright AJ, Campbell WW. A Mediterranean-style eating pattern with lean, unprocessed red meat has cardiometabolic benefits for adults who are overweight or obese in a randomized, crossover, controlled feeding trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2018;108(1):33–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Aadland EK, Lavigne C, Graff IE, Eng O, Paquette M, Holthe A, Mellgren G, Jacques H, Liaset B. Lean-seafood intake reduces cardiovascular lipid risk factors in healthy subjects: results from a randomized controlled trial with a crossover design. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;102(3):582–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Murphy KJ, Thomson RL, Coates AM, Buckley JD, Howe PR. Effects of eating fresh lean pork on cardiometabolic health parameters. Nutrients. 2012;4(7):711–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Mamo JC, James AP, Soares MJ, Griffiths DG, Purcell K, Schwenke JL. A low-protein diet exacerbates postprandial chylomicron concentration in moderately dyslipidaemic subjects in comparison to a lean red meat protein-enriched diet. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005;59(10):1142–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. van Nielen M, Feskens EJ, Rietman A, Siebelink E, Mensink M. Partly replacing meat protein with soy protein alters insulin resistance and blood lipids in postmenopausal women with abdominal obesity. J Nutr. 2014;144(9):1423–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Food and Agriculture Organization . 2018 Global Nutrition Report. [Internet]. [Accessed 2020 Aug 23]. Available from: https://globalnutritionreport.org/reports/global-nutrition-report-2018/ [Google Scholar]

- 57. Evert AB, Dennison M, Gardner CD, Garvey WT, Lau KHK, MacLeod J, Mitri J, Pereira RF, Rawlings K, Robinson Set al. Nutrition therapy for adults with diabetes or prediabetes: a consensus report. Dia Care. 2019;42(5):731–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Chai W, Morimoto Y, Cooney RV, Franke AA, Shvetsov YB, Le Marchand L, Haiman CA, Kolonel LN, Goodman MT, Maskarinec G. Dietary red and processed meat intake and markers of adiposity and inflammation: the multiethnic cohort study. J Am Coll Nutr. 2017;36(5):378–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Schulze MB, Hoffmann K, Manson JE, Willett WC, Meigs JB, Weikert C, Heidemann C, Colditz GA, Hu FB. Dietary pattern, inflammation, and incidence of type 2 diabetes in women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82(3):675–84.; quiz 714–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Wood RJ. The iron-heart disease connection: is it dead or just hiding? Ageing Res Rev. 2004;3(3):355–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Etemadi A, Sinha R, Ward MH, Graubard BI, Inoue-Choi M, Dawsey SM, Abnet CC. Mortality from different causes associated with meat, heme iron, nitrates, and nitrites in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2017;357:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. O'Connor LE, Hu EA, Steffen LM, Selvin E, Rebholz CM. Adherence to a Mediterranean-style eating pattern and risk of diabetes in a U.S. prospective cohort study. Nutr Diabetes. 2020;10(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Klurfeld DM. Research gaps in evaluating the relationship of meat and health. Meat Sci. 2015;109:86–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Potischman N, Weed DL.. Causal criteria in nutritional epidemiology. AJCN. 1999;69(6):1309S–14S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Gibney M, Allison D, Bier D, Dwyer J. Publisher Correction: Uncertainty in human nutrition research. Nat Food. 2020;1:309. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Hinderliter AL, Babyak MA, Sherwood A, Blumenthal JA. The DASH diet and insulin sensitivity. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2011;13(1):67–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Park YM, Zhang J, Steck SE, Fung TT, Hazlett LJ, Han K, Ko SH, Merchant AT. Obesity mediates the association between Mediterranean diet consumption and insulin resistance and inflammation in US adults. J Nutr. 2017;147(4):563–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.