In a recent article in the Journal, Blaes and Konety emphasize the need for future studies evaluating the prognostic value of cardiovascular risk stratification among breast cancer survivors (1). In other words, we need to know who is at risk and should receive cardiovascular monitoring. The authors describe various factors that increase cardiac risk among breast cancer survivors. In addition, other factors associated with cardiovascular disease (CVD), like psychological distress, should be taken into account as well. Moreover, knowledge of underlying mechanisms—why a person is at risk—is needed to provide potential targets for intervention.

Currently, a multiple-hit hypothesis has been proposed in cardio-oncological research describing that cancer survivors are exposed to a series of sequential or concurrent events that together make them vulnerable to develop CVD (2). According to this hypothesis, CVD risk increases with cancer diagnosis and cardiotoxic cancer treatment like anthracyclines (first hits) and traditional CVD risk factors, such as diabetes and hypertension (subsequent hit) (2).

Research on risk factors for incident CVD among noncancer populations has shown that next to traditional CVD risk factors, the mere presence of psychological distress like depression or anxiety is predictive of the onset of CVD and cardiac death (3). Both behavioral and pathophysiological mechanisms have been suggested to be underlying these associations. That is, depressed and anxious persons are known to display unhealthy lifestyles like physical inactivity and smoking (4), which are known CVD risk factors. With respect to pathophysiological mechanisms, depression and anxiety have been associated with increased inflammation; higher levels of the pro- (tumor necrosis factor-alpha [TNF-alpha] and IL-6) and lower anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1 and IL-4) (5). In turn, these cytokines are involved in the pathogenesis of CVDs, such as heart failure (5).

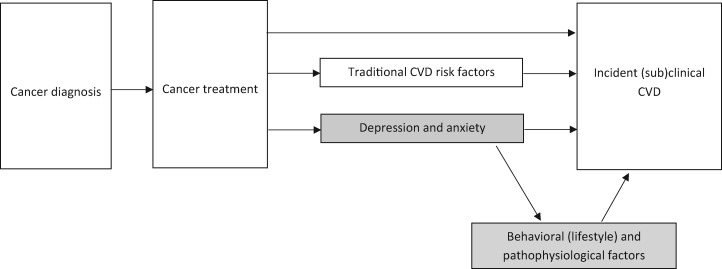

It is well known within the field of psycho-oncology that approximately 1 out of 2 breast cancer survivors experience symptoms of distress like depression and anxiety as a consequence of cancer diagnosis and treatment (6). Hence, breast cancer survivors may have an increased risk for incident CVD by these elevated levels of depression and anxiety alone. This knowledge has led to the adaption of the multiple-hit hypothesis (Figure 1) (7)—that is, incorporating an additional hit: depression and anxiety as risk factors for CVD and including potential behavioral and pathophysiological underlying mechanisms, thereby introducing the new field of psycho-cardio-oncology.

Figure 1.

The adapted multiple-hit hypothesis: the psychological factors depression and anxiety as an additional “hit” in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and underlying behavioral and pathophysiological mechanisms. The current model is adapted from our previously published (7) model applicable to cancer populations in general to fit the study population of breast cancer survivors. Our adaptations to the original model by Jones (2) are depicted in grey. Please note that the model is a necessary simplification, as various factors are associated with one another. To maintain the comprehensibility of the model, not all associations are explicitly depicted in the model.

Current clinical guidelines for cardiovascular risk assessment among noncancer populations highlight the importance of depression and anxiety as risk factors, with estimates at the same level as traditional CVD risk factors like hypertension. Nevertheless, depression and anxiety are currently not considered CVD risk factors in cardio-oncology. Testing the validity of the adapted multiple-hit hypothesis including psychological distress as an additional risk factor will help answer the question of who is at risk for CVD. Furthermore, knowledge of the underlying behavioral and pathophysiological mechanisms—why a person is at risk—provides targets for interventions that facilitate adequate follow-up care for breast cancer survivors.

Funding

This work was supported by the Dutch Cancer Society (#2013–5893).

Notes

Role of the funder: The funder had no role in the writing of this correspondence or the decision to submit it for publication.

Disclosures: The author has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Data Availability

Not applicable

References

- 1. Blaes AH, Konety SH.. Cardiovascular disease in breast cancer survivors: an important topic in breast cancer survivorship. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113(2):105–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jones LW, Haykowsky MJ, Swartz JJ, et al. Early breast cancer therapy and cardiovascular injury. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50(15):1435–1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lichtman JH, Froelicher ES, Blumenthal JA, et al. Depression as a risk factor for poor prognosis among patients with acute coronary syndrome: systematic review and recommendations: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;129(12):1350–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rebar AL, Stanton R, Geard D, et al. A meta-meta-analysis of the effect of physical activity on depression and anxiety in non-clinical adult populations. Health Psychol Rev. 2015;9(3):366–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Furman D, Campisi J, Verdin E, et al. Chronic inflammation in the etiology of disease across the life span. Nat Med. 2019;25(12):1822–1832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Linden W, Vodermaier A, Mackenzie R, et al. Anxiety and depression after cancer diagnosis: prevalence rates by cancer type, gender, and age. J Affect Disord. 2012;141(2-3):343–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schoormans D, Pedersen SS, Dalton S, et al. Cardiovascular co-morbidity in cancer patients: the role of psychological distress. Cardio-Oncology. 2016;2(1):9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable