Abstract

Introduction:

The evidence for the incidence and severity of liver injury in Chinese patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is still controversial. The purpose of this study was to summarize the incidence of liver injury and the differences between liver injury markers among different patients with COVID-19 in China.

Methods:

Computer searches of PubMed, Embase, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) and medRxiv were used to obtain reports on the incidence and markers of liver injury in Chinese patients with COVID-19, from January 1, 2020 to April 10, 2020. (No. CRD42020181350)

Results:

A total of 57 reports from China were included, including 9889 confirmed cases of COVID-19 infection. The results of the meta-analysis showed that among the patients with early COVID-19 infection in China, the incidence of liver injury events was 24.7% (95% CI, 23.4%–26.4%). Liver injury in severe patients was more common than that in non-severe patients, with a risk ratio of 2.07 (95% CI, 1.77–2.43). Quantitative analysis showed that the severe the coronavirus infection, the higher the level of alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspertate aminotransferase (AST), total bilirubin (TB), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT), and the lower the level of albumin (ALB).

Conclusion:

There is a certain risk of liver injury in Chinese patients with COVID-19, and the risk and degree of liver injury are related to the severity of COVID-19.

Keywords: coronavirus, COVID-19, liver injury, meta-analysis

1. Introduction

In December 2019, an unexplained viral pneumonia broke out in Wuhan, China, and the World Health Organization named it COVID-19.[1] As of April 20, 2020, the cumulative incidence of global COVID-19 has exceeded 2 million, and the number of death is close to 200,000.[1–3] Studies have shown that the pathogen of COVID-19 is β-coronavirus, and its gene sequence is highly similar to that of SARS and MERS.[4] The source and specific route of transmission of the virus are still unclear. The principal target organ of COVID-19 is the human lung, and some studies have shown that the virus can damage the heart, liver, nervous system, and so on.[5–8] Liver injury was also noted in SARS and MERS. Guan et al reported that abnormal elevation of AST accounted for 22.19% of COVID-19 patients (168/757). ALT accounted for 21.32% (158/741). Among the 99 cases reported by Chen et al, there were 43 cases of abnormal liver function. These findings seemed to imply that there was a definite relationship between novel coronavirus and liver injury.[8–10] However, the effect of COVID-19 on liver injury is still unclear and requires further study.

AST, ALT, TB, and ALB are important markers for the evaluation of liver injury. There are significant differences in the proportion and degree of increase in AST and ALT in the reports of early COVID-19 patients. China, at the outbreak point of the epidemic, published a large number of research reports in the early stage of the outbreak, including information about COVID-19 liver injury.[9,10] At present, some meta-analyses have noticed the situation of liver injury in COVID-19 patients, but there is no meta-analysis study on liver injury in COVID-19 patients in China, which was the first outbreak of the epidemic. So the purpose of this study is to perform a meta-analysis to systematically review and analyze the effects of COVID-19 on liver injury in China to provide some reference for clinical practice.

2. Methods

The systematic review and meta-analysis has been registered on Prospero (Registration number CRD42020181350; https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO). We reported this systematic review and meta-analysis according to MOOSE guidelines and PRISMA.[11,12]

2.1. Search strategy

Three electronic databases, PubMed, Embase, CNKI and the medRxiv system (https://www.medrxiv.org), were searched by our team. The keywords included “coronavirus”, “nCoV”, “SARS-CoV-2”, “COVID”, “COVID-19”, “NCP” and “China”. We screened the retrieved literature, and the eligible study was to report the occurrence of liver injury or the abnormal rise or abnormal changes of biochemical markers of liver injury (AST, ALT, TB, and so on), and the original data should come from China.

2.2. Studies selection

We selected studies that met the following inclusion criteria:

-

1.

nucleic acid-confirmed and clinically confirmed COVID-19 patients;

-

2.

reported studies of liver injury events or liver injury markers;

-

3.

the language was confined to English or Chinese;

-

4.

the source of the research was limited to China;

-

5.

the retrieval time was limited from January 1, 2020 to April 10, 2020.

If the research was from multiple centers, we tried to divide it into a single center for analysis. If there were multiple studies on the same team, the latest research from the team was used for analysis.

The following studies were excluded:

-

1.

COVID-19 patients without nucleic acid diagnosis or clinical diagnosis;

-

2.

reports of special groups such as pregnant women and children;

-

3.

studies that only report deaths or critically ill patients;

-

4.

studies that do not report liver injury events or markers of liver injury;

-

5.

research reports that the participants are not from China.

2.3. Data extraction and quality assessment

Three authors (ZX, LZH, GFW) performed a preliminary screening of the search literature, and finally (ZX, LZH) 2 authors read the full text and agreed on which studies to include in the final analysis. The 4 authors (ZX, GFW, XQY, JKY) independently extracted the relevant information included in the literature, including the first author, the time of publication, the source of the literature, the time of research, the number, age, male-to-female ratio, case distribution, complications, use of therapeutic drugs, events of liver injury, changes in markers of liver injury, and differences in the process of data extraction. Disagreements were settled by discussion of all the investigators. We used the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale for retrospective studies to assess the methodological quality of included studies.

2.4. Statistical analysis

We used stata16.0 for data analysis. We define liver injury as AST or ALT or TB above the upper limit, as if there are 3 or 2 items of data in a study. The term with the highest number of events was used as the analytical data. If the P value of liver injury is .3 to .7, meta-analysis was carried out directly; on the contrary, the data were converted by Freeman-Tukey double arcsine transformation to make them in accordance with a normal distribution and then analyzed and combined.[13] The ultimate result after data conversion was restored by using the formula P = [sin (tp/2)]2. The degree of heterogeneity was evaluated by the Q2 and I2 indexes. I2 is low heterogeneity when it is 0% to 25%, moderate heterogeneity when it is 26% to 75%, and high heterogeneity when it is 76% to 100%. The fixed effect model was used when I2 < 25% P > .1; if I2 ≥ 25% or P ≤ .1, the random effect model was used. If only the median and quartile ranges (Q25 and Q75) were reported, then we assumed that the median was equivalent to the average, and the standard deviation (SD) is (Q75-Q25)/2. We also performed a subgroup analysis of the results with heterogeneity, and publication bias was evaluated by Bgger test. A bilateral P value less than or equal to .05 was regarded as statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Eligible studies and characteristics

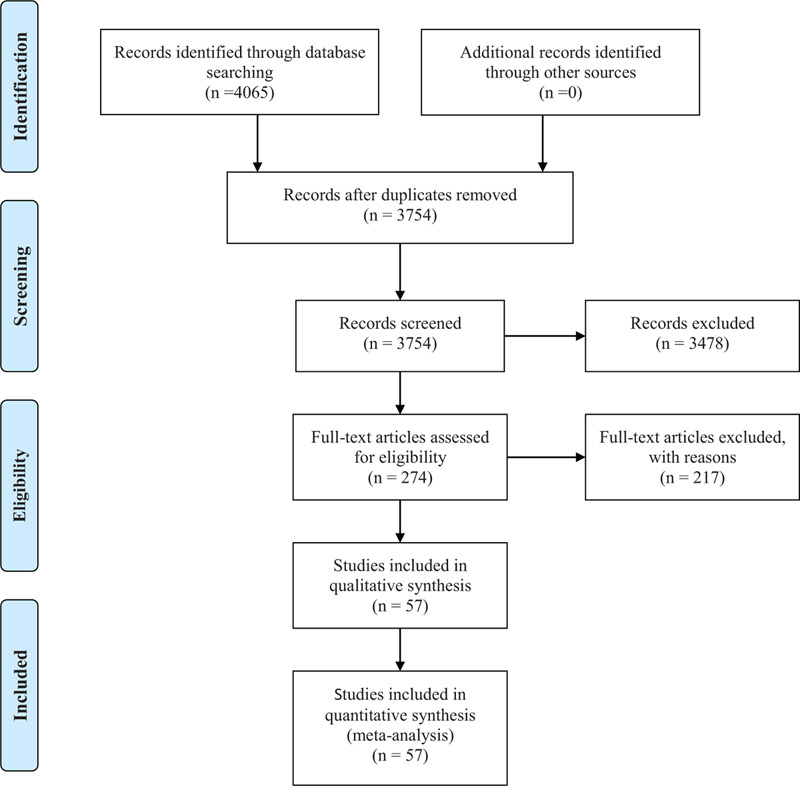

We searched for a total of 4065 potentially relevant articles. Of these, 274 trials were included based on the titles and abstracts. After careful full-text screening, 217 articles were discarded and 57 articles[2,9,10,14–67] were included, all of which were retrospective studies. The detailed search and study selection process are shown in PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1.). Thirty five articles were published in public journals, and 22 were published in preprints.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of selected articles.

3.2. Study characteristics and quality

Of the 57 studies, 23 were from Wuhan and 34 were not from Wuhan. Among them, 5 studies were compared between death and survival patients, 4 studies were compared between ICU and non-ICU patients, and 39 studies were reported between severe patients and non-severe patients, of which the diagnosis of severe and nonsevere cases was based on the diagnosis and treatment of pneumonia caused by COVID-19 in China. A total of 9889 patients diagnosed with COVID-19 were enrolled. The source of the cases was primarily from January to February 2020. The main comorbidities included hypertension, diabetes, liver disease, and so on. Drug treatment was mainly antibiotics and antivirals. Some studies reported treatment using traditional Chinese medicine, which is shown in Table 1. The Newcastle–Ottawa scale (NOS) was used to evaluate the quality of retrospective studies, the results of NOS score is also shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

General characteristics of included studies.

| Period | Sex | comorbidities | Drug treatment | |||||||||||

| Author | Year | (2019/12–2020/04) | Area | Cases | Ages | Male | Female | L | H | D | Antib | Antiv | Tcm | NOS |

| Cai QX et al. | 2020 | 01/11–03/07 | Non-Wuhan | 417 | 47 (34–60) | 198 | 219 | 21 | 58 | 23 | 47 | 288 | 272 | 6 |

| Cao JL et al. | 2020 | 01/03–02/01 | Wuhan | 102 | 54 (37–67) | 53 | 49 | 2 | 28 | 11 | 101 | 100 | 3 | 7 |

| Cao M et al. | 2020 | 01/20–02/15 | Non-Wuhan | 198 | 50.1 ± 16.3 | 101 | 97 | 6 | 42 | 15 | N | N | N | 6 |

| Cao WL et al. | 2020 | 01/01–02/16 | Non-Wuhan | 128 | N | 60 | 68 | N | N | N | N | N | N | 5 |

| Chen G et al. | 2020 | N-01/27 | Wuhan | 21 | 56 (50–65) | 17 | 4 | N | N | N | 21 | 17 | N | 5 |

| Chen L et al. | 2020 | 01/14–01/29 | Wuhan | 29 | 56 (26–79) | 21 | 8 | 2 | 8 | 5 | N | N | N | 6 |

| Chen NS et al. | 2020 | 01/01–01/20 | Wuhan | 99 | 55.5 ± 13.1 | 67 | 32 | N | N | N | 70 | 75 | N | 5 |

| Chen T et al. | 2020 | 01/13–02/12 | Wuhan | 274 | 62 (44–70) | 171 | 103 | 11 | 93 | 47 | N | N | N | 6 |

| Chen X et al. | 2020 | 01/23–02/14 | Non-Wuhan | 291 | (1–84) | 145 | 146 | 15 | 39 | 22 | N | 285 | 281 | 7 |

| Chen KB et al. | 2020 | 01/01–02/06 | Wuhan | 463 | 51 (43–60) | 244 | 219 | 22 | 107 | 40 | 406 | 220 | 63 | 7 |

| Deng Y et al. | 2020 | 01/01–02/21 | Wuhan | 225 | N | 124 | 101 | N | 58 | 26 | 185 | 191 | N | 6 |

| Fan LC et al. | 2020 | 01/20–03/15 | Non-Wuhan | 55 | 46.8 | 30 | 25 | N | 8 | 8 | 29 | 53 | N | 6 |

| Fan ZY et al. | 2020 | 01/20–01/31 | Non-Wuhan | 148 | 50 (36–64) | 73 | 75 | 9 | N | N | 50 | 39 | N | 6 |

| Fu L et al. | 2020 | N | Wuhan | 355 | N | 190 | 165 | 16 | 125 | 145 | N | N | N | 7 |

| Fang XW et al. | 2020 | 01/22–02/18 | Non-Wuhan | 79 | 45.1 ± 16.6 | 45 | 34 | 3 | 16 | 8 | 49 | 79 | 44 | 8 |

| Gao W et al. | 2020 | 01/01–02/28 | Non-Wuhan | 90 | 53 ± 16.9 | 43 | 47 | N | 21 | 9 | N | N | N | 6 |

| Gong J et al. | 2020 | 01/20–03/02 | Non-Wuhan | 189 | N | 88 | 101 | N | N | N | N | N | N | 6 |

| Guan W et al. | 2020 | 12/11–01/29 | Wuhan | 1099 | 47 (35–58) | 640 | 459 | 23 | 165 | 81 | 637 | 393 | N | 8 |

| Hu L et al. | 2020 | 01/08–02/10 | Wuhan | 323 | 61 (23–91) | 166 | 157 | 8 | 105 | 47 | 255 | 304 | N | 7 |

| Huang CL et al. | 2020 | 12/N-01/02 | Wuhan | 41 | 25-49 | 30 | 11 | 1 | 6 | 8 | 41 | 38 | N | 7 |

| Huang H et al. | 2020 | 01/20–02/29 | Non-Wuhan | 125 | 44.87 ± 18.55 | 63 | 62 | N | 20 | 8 | N | N | N | 8 |

| Jiang XF et al. | 2020 | 01/23–02/16 | Non-Wuhan | 55 | 45 (27–60) | 27 | 28 | 2 | 17 | 9 | 29 | 55 | N | 6 |

| Jin X et al. | 2020 | 01/17–02/08 | Non-Wuhan | 651 | 46.14 ± 14.19 | 74 | 577 | 25 | 100 | 48 | 277 | 546 | N | 7 |

| Li D et al. | 2020 | 01/20–02/27 | Non-Wuhan | 80 | 47.5 (3–90) | 40 | 40 | 3 | 14 | 10 | 56 | 80 | N | 7 |

| Li L et al. | 2020 | 01/21–02/29 | Non-Wuhan | 85 | 49 (36,64) | 47 | 38 | 6 | N | N | N | N | N | 6 |

| Liu C et al. | 2020 | 01/23–02/08 | Non-Wuhan | 32 | 38.5 (26.25–45.75) | 20 | 12 | 1 | 1 | N | N | N | N | 6 |

| Liu J et al. | 2020 | 01/5–01/24 | Wuhan | 40 | 48.7 ± 13.9 | 15 | 25 | N | 6 | 6 | N | N | N | 6 |

| Lu HZ et al. | 2020 | N-02/07 | Non-Wuhan | 265 | N | N | N | 1 | 52 | 21 | N | N | N | 5 |

| Luo XM et al. | 2020 | 01/30–02/25 | Wuhan | 403 | 56 (39–68) | 193 | 210 | N | 113 | 57 | 349 | 349 | N | 7 |

| Mo PZ et al. | 2020 | 01/01–01/25 | Wuhan | 155 | 54 (42–66) | 86 | 69 | 7 | 37 | 15 | N | 45 | N | 6 |

| Nie SK et al. | 2020 | 02/29–02/28 | Wuhan | 97 | 39 (30–60) | 34 | 63 | 3 | 15 | 5 | 47 | 86 | 33 | 7 |

| Qian GQ et al. | 2020 | 01/20–02/11 | Non-Wuhan | 91 | 50 (36.5–57) | 54 | 37 | N | 15 | 8 | N | N | N | 6 |

| Qian ZP et al. | 2020 | 01/20–02/24 | Non-Wuhan | 324 | 51 (31–64) | 167 | 157 | 20 | 67 | 23 | N | N | N | 7 |

| Qiu CF et al. | 2020 | 01/22–02/12 | Non-Wuhan | 104 | 43 ± 7.54 | 49 | 55 | N | 15 | 12 | 51 | 21 | 80 | 7 |

| Shi SH et al. | 2020 | 12/20–2020 | Wuhan | 81 | 49.5 ± 11.0 | 42 | 39 | 7 | 12 | 10 | N | N | N | 6 |

| Wang DW et al. | 2020 | 01/01–01/28 | Wuhan | 138 | 56 (42–68) | 75 | 63 | 4 | 43 | 14 | 89 | 124 | N | 8 |

| Wang SH et al. | 2020 | 01/10–01/14 | Wuhan | 333 | 62 (26–88) | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | 5 |

| Wen K et al. | 2020 | 01/20–02/08 | Non-Wuhan | 46 | 41.8 ± 16.3 | 27 | 19 | N | 7 | 3 | N | N | N | 6 |

| Wu J et al. | 2020 | 01/22–02/14 | Non-Wuhan | 80 | 46.1 ± 15.42 | 39 | 41 | 1 | N | N | 73 | 80 | 3 | 7 |

| Xiang TX et al. | 2020 | 01/21–01/27 | Non-Wuhan | 49 | 42.9 | 33 | 16 | 6 | 6 | 2 | N | N | N | 7 |

| Xie HS et al. | 2020 | 02/02–02/23 | Wuhan | 79 | 60.0 (48.0–66.0) | 44 | 35 | N | 14 | 8 | N | N | N | 6 |

| Xiong J et al. | 2020 | 01/17–02/20 | Wuhan | 89 | 53 ± 16.9 | 41 | 48 | N | 3 | 3 | 19 | 37 | N | 6 |

| Xu XW et al. | 2020 | 01/10–02/26 | Non-Wuhan | 62 | 41 (32–52) | 36 | 26 | 7 | 5 | 1 | 28 | 55 | N | 7 |

| Yan SJ et al. | 2020 | 01/22–03/13 | Non-Wuhan | 168 | 51 (36–62) | 81 | 87 | 6 | 24 | 12 | 119 | 155 | 30 8 | |

| Yang WJ et al. | 2020 | 01/17–02/10 | Non-Wuhan | 149 | 45.11 ± 13.35 | 81 | 68 | N | N | N | 34 | 140 | N | 6 |

| Yang XB et al. | 2020 | 12/N-01/26 | Wuhan | 52 | 59·7 (13 3) | 35 | 17 | N | N | 9 | 49 | 23 | N | 6 |

| Yao N et al. | 2020 | 01/21–02/21 | Non-Wuhan | 40 | 53.87 ± 15.84 | 25 | 15 | N | N | N | N | N | N | 5 |

| Yuan J et al. | 2020 | 01/24–02/23 | Non-Wuhan | 223 | 46.5 ± 16.1 | 106 | 117 | 8 | 25 | 18 | N | 223 | N | 7 |

| Zhang C et al. | 2020 | N | Non-Wuhan | 56 | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | 5 |

| Zhang GQ et al. | 2020 | 01/02–02/10 | Wuhan | 221 | 55 (20–96) | 108 | 113 | 7 | 54 | 22 | N | 196 | N | 7 |

| Zhang W et al. | 2020 | 01/21–02/11 | Non-Wuhan | 74 | 52.7 ± 19.1 | 35 | 39 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 14 | 21 | 72 | 8 |

| Zhang YF et al. | 2020 | 01/18–02/22 | Wuhan | 115 | 49.52 ± 17.06 | 49 | 66 | N | N | N | N | N | N | 6 |

| Zhao W et al. | 2020 | 01/21–02/8 | Non-Wuhan | 77 | 52 ± 20 | 34 | 43 | 8 | 16 | 6 | N | N | N | 7 |

| Zhao ZH et al. | 2020 | 01/21–02/16 | Non-Wuhan | 75 | 47 (34–55) | 42 | 33 | 4 | N | 6 | N | N | N | 7 |

| Zheng F et al. | 2020 | 01/17–02/07 | Non-Wuhan | 161 | 45 (33.5, 57) | 80 | 81 | 4 | 22 | 7 | N | N | N | 6 |

| Zhou F et al. | 2020 | 2019/12/29–2020/01/31 | Wuhan | 191 | 56 (46–67) | 119 | 72 | N | 58 | 36 | 181 | 41 | N | 7 |

| Zhou FT et al. | 2020 | 01/17–02/26 | Non-Wuhan | 197 | 55.94 ± 18.83 | 99 | 98 | 2 | N | 18 | 151 | 179 | 81 | 6 |

Antib = antibiotics, Antib = antivirals, D = diabetes, H = hypertension, L = liver-related diseases, N = no such data in the study, NOS = the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale, Tcm = traditional Chinese medicine.

3.3. The incidence of liver injury in patients with COVID-19

A total of 33 studies reported liver injury events, and the number of liver injury events was 1460 in 5867 COVID-19 patients, and the initial combined effect was P < .3. After converting the data by Freeman-Tukey double arcsine transformation, the meta-analysis obtained a purge of 0.247 [95%CI (0.234, 0.264), P < .01], and the incidence of liver injury in Wuhan was 24.7% [95%CI (23.4%–26.4%), P < .01] (Fig. 2). The subgroup analysis of Wuhan and non-Wuhan areas showed that the incidence of liver injury in Wuhan was 26.4% [95%CI (24.3%, 28.2%), P < .01] and that outside of Wuhan areas was 23.8% [95%CI (22.1%, 26.0%), P < .01]. The incidence of liver injury in Wuhan is slightly higher than that outside of Wuhan (Table 2).

Figure 2.

The incidence of liver injury.

Table 2.

Overall summary of results.

| Outcomes | Effect size I2P value Bgger | ||||

| Rate of LI | overall | Rate (1.04, 1.01 to 1.07) | 5.4% | <.01 | 0.227 |

| subgroup | Wuhan | Rate (1.08, 1.03 to 1.12) | 0 | <.01 | |

| Non-Wuhan | Rate (1.08, 1.01 to 1.07) | 29.9% | <.01 | ||

| LI in Severe | overall | RR (2.08, 1.77 to 2.44) | 63.2% | <.01 | 0.116 |

| subgroup | ALT | RR (1.69, 1.37 to 2.09) | 34.8% | <.01 | |

| AST | RR (2.57, 2.04 to 3.25) | 54.7% | <.01 | ||

| TB | RR (1.76, 1.17 to 2.65) | 53.2% | <.01 | ||

| ALT(U/L) | |||||

| S vs Non-S | overall | SMD (0.51, 0.31 to 0.71) | 84.8% | <.01 | 0.428 |

| Wuhan | SMD (0.35, 0.03 to 0.67) | 86.5% | <.01 | ||

| Non-Wuhan | SMD (0.60, 0.37 to 0.83) | 77.8% | <.01 | ||

| I vs Non-I | SMD (0.90, 0.62 to 1.18) | 0 | <.01 | 1.00 | |

| D vs Sur | SMD (0.73, 0.44 to 1.02) | 72.5% | <.01 | 0.734 | |

| AST(U/L) | |||||

| S vs Non-S | overall | SMD (1.05, 0.76 to 1.34) | 92.2% | <.01 | 0.209 |

| Wuhan | SMD (0.76, 0.36 to 1.15) | 90.5% | <.01 | ||

| Non-Wuhan | SMD (1.19, 0.84 to 1.55) | 90.2% | <.01 | ||

| I vs Non-I | SMD (1.30, 0.69 to 1.91) | 75.1% | <.01 | 0.296 | |

| D vs Sur | SMD (1.57, 1.35 to 1.80) | 35.2% | <.01 | 1.00 | |

| TB (umol/L) | |||||

| S vs Non-S | overall | SMD (0.52, 0.34 to 0.71) | 78.9% | <.01 | 0.259 |

| Wuhan | SMD (0.50, 0.18 to 0.82) | 86.7% | <.01 | ||

| Non-Wuhan | SMD (0.54, 0.32 to 0.77) | 71.2% | <.01 | ||

| I vs Non-I | SMD (0.62, 0.35 to 0.90) | 0 | <.01 | 1.00 | |

| D vs Sur | SMD (0.42, −1.03 to 1.87) | 98.4% | =.57 | 0.734 | |

| ALB (umol/L) | |||||

| S vs Non-S | overall | SMD (−1.2, −1.47 to −0.93) | 87.5% | <.01 | 0.127 |

| Wuhan | SMD (−1.53, −2.11 to −0.95) | 94.6% | <.01 | ||

| Non-Wuhan | SMD (−1.09, −1.38 to −0.80) | 77.2% | <.01 | ||

| I vs Non-I | SMD (−2.44, −4.30 to -0.59) | 97% | =.01 | 1.00 | |

| ALP(U/L) | SMD (0.49, 0.11–0.86) | 87.7% | =.01 | 0.764 | |

| GGT(U/L) | SMD (0.64, 0.15–1.14) | 92.9% | =.01 | 1.00 | |

D = death, I = ICU, LI = liver injury, S = severe, Sur = survival.

3.4. The relationship between the severity of COVID-19 and the incidence of liver injury

Eleven studies reported the occurrence of liver injury caused by increased ALT in severe and nonsevere patients, suggesting that the risk of liver injury in severe COVID-19 patients was 1.69 times higher than that in non-severe patients [RR 1.69, 95%CI (1.37, 2.09), P < .01]. Thirteen studies reported the occurrence of liver injury caused by elevated AST in severe and nonsevere patients, suggesting that the risk of liver injury in severe COVID-19 patients was 2.57 times higher than that in nonsevere patients [RR 2.57, 95%CI (2.04, 3.25), P < .01]. Eight studies reported the occurrence of liver injury caused by elevated TB in severe and nonsevere patients, suggesting that the risk of liver injury in severe COVID-19 patients was 1.70 times higher than that in nonsevere patients [RR 1.70, 95%CI (1.19, 2.44), P < .01]. The combined analysis showed that the risk of liver injury in severe COVID-19 patients was 2.07 times higher than that in nonsevere patients [RR 2.07, 95%CI (1.77, 2.43), P < .01] (Fig. 3, Table 2).

Figure 3.

Liver injury of severe vs nonsevere.

3.5. The relationship between COVID-19 and the degree of liver injury

In the comparative study of severe and non-severe COVID-19, 27 studies showed that the ALT(U/L) of severe patients was higher than that of nonsevere patients[SMD 0.51, 95%CI (0.31, 0.71), P < .01] (Table 2), There were 29 reports of AST(U/L) comparison. The results showed that the AST of severe patients was higher [SMD 1.05, 95%CI (0.76, 1.34), P < .01] (Table 2). TB comparison (μmol/L) was performed in 22 items, and the results showed that the TB of severe patients was higher [SMD 0.52, 95%CI (0.34, 0.71), P < .01] (Table 2). There were 7 reports of ALP (U/L) comparisons, and the results showed that the ALP of severe patients was higher [SMD 0.49, 95%CI (0.11, 0.86), P = .01] (Table 2). There were 6 reports of GGT(U/L) comparison, and the results showed that the GGT of severe patients was higher [SMD 0.64, 95%CI (0.15, 1.14), P = .01] (Table 2). The consequences of 20 reports of ALB (g/L) comparison showed that ALB was lower in severe patients[SMD -1.2, 95%CI (−1.47, −0.93), P < .01] (Table 2). The subgroup analysis of ALT, AST, TB, and ALB for severe patients in Wuhan and non-Wuhan areas showed no significant change in heterogeneity (Table 2). In 3 reports of ICU and non-ICU and 4 reports of survival and death of COVID-19 patients, the changing trend of ALT, ALT, TB, and ALB was comparable to that of severe and nonsevere patients. The above results showed that there was no publication bias in the Bgger test, suggesting that the more intense the COVID-19 infection, the more severe the liver injury (Table 2).

3.6. Publication bias and sensitivity analysis

The funnel plot and Bgger test showed no publication bias for rate of liver injury (Table 2), the relationship between the severity of COVID-19 and the incidence of liver injury (Table 2) and the relationship between COVID-19 and the degree of liver injury (Table 2). Forest plot showed little sensitivity change by systematically removing each study for rate of liver injury, the relationship between the severity of COVID-19 and the incidence of liver injury, the relationship between COVID-19 and the degree of liver injury.

4. Discussion

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we found that the incidence of liver injury in Chinese COVID-19 patients was 24.7%, and the incidence of liver injury in Wuhan was slightly higher than that in non-Wuhan patients. At present, the mechanism of liver injury in patients with COVID-19 includes SARS-CoV-2 virus directly attacking liver tissue, and the target receptor of SARS-CoV-2 is the ACE2 receptor. However, previous studies have shown that the ACE2 receptor is highly expressed in intrahepatic bile duct epithelial cells but is expressed at low levels in hepatocytes.[68,69] Therefore, it is possible for the SARS-CoV-2 virus to directly damage the intrahepatic biliary system, but it is less likely to directly damage hepatocytes. In our study, we also found that GGT is a marker of bile duct injury. ALP increased, but only 7 cases were reported. The mechanism of secondary liver injury includes the inflammatory storm effect caused by systemic inflammation, drug factors and multiple organ dysfunction caused by hypoxia. A meta-analysis by Wang concluded that there was no significant correlation between chronic liver disease patients and coronavirus severity.[70] Mantovani[71] reported that the total prevalence rate of COVID-19 in patients with chronic liver disease was only 3%. Two other studies reported that liver injury markers in mild patients were at normal levels, which seemed to suggest that COVID-19 was less likely to directly damage the liver.[2,46]

In our study, we observed that the incidence of liver injury and AST, ALT, TB, GGT, and ALP quantitative analysis of liver injury markers in severe patients were higher than those in nonsevere patients, while the quantity of ALB in severe patients was lower than that in nonsevere patients. The trend of ICU was similar to that of non-ICU patients. This conclusion is consistent with the clinical characteristics of patients with COVID liver injury analyzed by Qi.[7] All these findings suggest that the more serious the COVID infection, the higher the risk of liver injury and the more severe the injury. The more intense the infection symptoms of critically ill patients are, the greater the impact of the storm of inflammatory factors on liver function. In addition, most of patients included in the study were diagnosed between January and February 2020, who were treated promptly, when the drug treatment of critically ill patients is often uncertain, and antiviral, antibiotic, and traditional Chinese medicine treatments are often combined. It will cause some damage to liver function. Additionally, patients with severe COVID-19 often have hypoxemia, which leads to hepatocyte ischemia and hypoxia, and multiple organ failure may also be one of the causes of liver damage. Therefore, secondary liver injury is more common in critically ill patients, but the possibility of direct liver injury caused by COVID-19 cannot be ruled out. Therefore, in critically ill patients, real-time monitoring of liver function, evaluation of liver injury, and inexpensive choice of drug treatment are necessary. We also included 4 analyses of liver damage in dead and surviving COVID-19 patients. Changes in liver injury markers were similar to those of severe and nonsevere patients. Owing to data limitations, we did not further analyze whether liver injury increases the risk of death in patients with COVID-19.

Our study also has some limitations. First, although there is no obvious bias in the definition of liver injury and detection of liver injury markers, some of the results are still heterogeneous. Second, this study only analyzed the data of Chinese COVID-19 patients, not remote data analysis. Third, it is not possible to further describe the effects of other confounding factors, such as complications, age, and gender, on the results of the study; these confounding factors are also difficult to adjust. Fourth, most of the included studies are retrospective analyses, some are cross-sectional studies, 22 are manuscripts that have not been peer-reviewed, and there is a danger of bias in data collection.

5. Conclusion

There is a certain risk of liver injury in Chinese patients with COVID-19, and the risk and degree of liver injury are related to the severity of COVID-19.

Acknowledgments

Thanks for prof. Zehua Lei revising the manuscrip.

Author contributions

Xin Zhao and Zehua Lei contributed to the study concept and design. Xin Zhao, Fengwei Gao, Qingyun Xie, and Kangyi Jang acquired, analyzed, and interpreted the data. Xin Zhao and Zehua Lei drafted the manuscript. Xin Zhao, Fengwei Gao, Qingyun Xie, Jie Gong performed statistical analysis. Zehua Lei made critical revisions to the manuscript.

Conceptualization: Xin Zhao, Zehua Lei.

Data curation: Xin Zhao, Zehua Lei, Fengwei Gao, Qingyun Xie, Kangyi Jang, Jie Gong.

Formal analysis: Xin Zhao, Zehua Lei, Kangyi Jang.

Investigation: Xin Zhao.

Methodology: Xin Zhao, Fengwei Gao, Qingyun Xie.

Software: Xin Zhao, Qingyun Xie, Kangyi Jang, Jie Gong.

Writing – original draft: Xin Zhao, Fengwei Gao.

Writing – review & editing: Zehua Lei.

Glossary

Abbreviations: ALB = albumin, ALP = alkaline phosphatase, ALT = alanine aminotransferase, AST = aspertate aminotransferase, CNKI = China National Knowledge Infrastructure, COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019, GGT = γ-glutamyl transpeptidase, TB = total bilirubin.

References

- [1]. WHO main website. https://www.who.int [Accessed March 2] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Huang CL, Wang YM, Li XM, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020;395:497–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3]. China. NHCotPsRo, http://www.nhc.gov.cn [Assessed on April 22, 2020] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Lu R, Zhao X, Li J, et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet 2020;395:565–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Inciardi RM, Lupi L, Zaccone G, et al. Cardiac involvement in a patient with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol 2020;5:819–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Mao L, Wang M, Chen S, et al. Neurological manifestations of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective case series study. medRxiv 2020;2020.2002.2022.20026500. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Qi X, Liu C, Jiang Z, et al. Multicenter analysis of clinical characteristics and outcome of COVID-19 patients with liver injury. J Hepatol 2020;73:455–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Chau TN, Lee KC, Yao H, et al. SARS-associated viral hepatitis caused by a novel coronavirus: report of three cases. Hepatology 2004;39:302–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. NEJM 2020;382:1708–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Chen NS, Zhou M, Dong X, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet 2020;507–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Liberati A, AD, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009;339:b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 2000;283:2008–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Barendregt JJ, Doi SA, Lee YY, et al. Meta-analysis of prevalence. J Epidemiol Community Health 2013;67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Cai Q, HD, Yu H, et al. Characteristics of liver tests in COVID-19 patients [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 13]. J Hepatol 2020;S0168-8278(20): 30218-X. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Cao J, Tu WJ, Cheng W, et al. Clinical features and short-term outcomes of 102 patients with corona virus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. Clin Infec Dis 2020;71:748–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Cao M, Zhang D, Wang Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) in Shanghai, China. medRxiv 2020;2020.2003.2004.20030395. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Cao W. Clinical features and laboratory inspection of novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) in Xiangyang, Hubei. medRxiv 2020;2020.2002.2023.20026963. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Chen G, Wu D, Guo W, et al. Clinical and immunologic features in severe and moderate forms of coronavirus disease 2019. medRxiv 2020;2020.2002.2016.20023903. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Chen L, Liu W, Liu J, et al. Analysis of clinical features of 29 patients with 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi 2020;43:203–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Chen T, Wang D, Chen HL, et al. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: retrospective study. BMJ 2020;368:m1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Chen X, Jiang Q, Ma Z, et al. Clinical characteristics of hospitalized patients with SARS-CoV-2 and hepatitis B virus co-infection. medRxiv 2020;2020.2003.2023.20040733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Chen X, Zheng F, Qing Y, et al. Epidemiological and clinical features of 291 cases with coronavirus disease 2019 in areas adjacent to Hubei, China: a double-center observational study. medRxiv 2020;2020.2003.2003.20030353. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Cheng KB, Wei M, Shen H, et al. Clinical characteristics of 463 patients with common and severe type coronavirus disease 2019 [J/OL]. Shanghai Med J 2020;43:224–32. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Deng Y, Liu W, Liu K, et al. Clinical characteristics of fatal and recovered cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Wuhan, China: a retrospective study[Publish Ahead of Print]. Chinese Med J 2020;133:1261–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Fan L, Liu C, Li N, et al. Medical treatment of 55 patients with COVID-19 from seven cities in northeast China who fully recovered: a single-center, retrospective, observational study. medRxiv 2020;2020.2003.2028.20045955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Fan Z, Chen L, Li J, et al. Clinical Features of COVID-19-related liver damage [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 10]. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;S1542-3565: 30482-30481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Fang XW, Mei Q, Yang TJ, et al. Clinical characteristics and treatments strategeies of 79 patients with COVID-19[published online ahead of print]. Chin Pharmacol Bullt 2020;36. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Fu L, Fei J, Xu S, et al. Acute liver injury and its association with death risk of patients with COVID-19: a hospital-based prospective case-cohort study. medRxiv 2020;2020.2004.2002.20050997. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Gao W, Yang X, Zheng X, et al. Clinical characteristic of 90 patients with COVID-19 hospitalized in a Grade-A hospital in Beijing[published online ahead of print]. Acad J Chin PLA Med Sch 2020;41:208–11. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Gong J, Ou J, Qiu X, et al. A tool to early predict severe 2019-novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19): a multicenter study using the risk nomogram in Wuhan and Guangdong, China. medRxiv 2020;2020.2003.2017.20037515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Hu L, Chen S, Fu Y, et al. Risk factors associated with clinical outcomes in 323 COVID-19 patients in Wuhan, China. medRxiv 2020;2020.2003.2025.20037721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Huang H, Cai S, Li Y, et al. Prognostic factors for COVID-19 pneumonia progression to severe symptom based on the earlier clinical features: a retrospective analysis. medRxiv 2020;2020.2003.2028.20045989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Jiang X, Tao J, Wu H, et al. Clinical features and management of severe COVID-19: a retrospective study in Wuxi, Jiangsu Province, China. medRxiv 2020;2020.2004.2010.20060335. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Jin X, Lian JS, Hu JH, et al. Epidemiological, clinical and virological characteristics of 74 cases of coronavirus-infected disease 2019 (COVID-19) with gastrointestinal symptoms. Gut 2020;69:1002–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Li D, Long YT, Huang P, et al. Clinical characteristics of 80 patients with COVID-19 in Zhuzhou City. Chin J Infect Control 2020;19:227–33. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Li L, Li S, Xu M, et al. Risk factors related to hepatic injury in patients with corona virus disease 2019. medRxiv 2020;2020.2002.2028.20028514. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Liu C, Jiang ZC, Shao CX, et al. Preliminary study of the relationship between novel coronavirus pneumonia and liver function damage: a multicenter study. Chin J Hepatol 2020;28:148–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Liu J, Li S, Liu J, et al. Longitudinal characteristics of lymphocyte responses and cytokine profiles in the peripheral blood of SARS-CoV-2 infected patients. medRxiv 2020;2020.2002.2016.20023671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Lu H, Ai J, Shen Y, et al. A descriptive study of the impact of diseases control and prevention on the epidemics dynamics and clinical features of SARS-CoV-2 outbreak in Shanghai, lessons learned for metropolis epidemics prevention. medRxiv 2020;2020.2002.2019.20025031. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Luo X, Xia H, Yang W, et al. Characteristics of patients with COVID-19 during epidemic ongoing outbreak in Wuhan, China. medRxiv 2020;2020.2003.2019.20033175. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Mo PZ, Xing YY, Xiao Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of refractory COVID-19 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis 2020;ciaa270. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Nie S, Zhao X, Zhao K, et al. Metabolic disturbances and inflammatory dysfunction predict severity of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a retrospective study. medRxiv 2020;2020.2003.2024.20042283. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Qian ZP, Mei X, Zhang YY, et al. Analysis of baseline liver biochemical parameters in 324 cases with novel coronavirus pneumonia in Shanghai area. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi 2020;28: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Qiu C, Xiao Q, Liao X, et al. Transmission and clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in 104 outside-Wuhan patients, China. medRxiv 2020;2020.2003.2004.20026005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Shi HS, Han XY, Jiang NC, et al. Radiological findings from 81 patients with COVID-19 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis 2020;20:425–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Wang DW, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA 2020;323:1061–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Wang SH, Han P, Xiao F, et al. Manifestations of liver injury in 333 hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Chin J Dig 2020;40:157–61. [Google Scholar]

- [48].Wen K, Li WG, Zhang DW, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 46 newly-admitted coronavirus disease 2019 cases in Beijing [J/OL]. Chin J Infect Dis 2020;46:354–60. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Wu J, Liu J, Zhao XG, et al. Clinical characteristics of imported cases of COVID-19 in Jiangsu Province: a multicenter descriptive study. Clin Infect Dis 2020;71:706–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Xiang TX, Li J, Xu F, et al. Analysis of clinical characteristics of 49 patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Jiangxi. Chin J Respria Criti Medic 2020;19:154–60. [Google Scholar]

- [51].Xie H, Zhao J, Lian N, et al. Clinical characteristics of non-ICU hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 and liver injury: a retrospective study. Liver Inter 2020;40:1321–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Xiong J, Jiang W, Zhou Q, et al. Clinical characteristics, treatment, and prognosis in 89 cases of COVID-2019. Med J Wuhan Univ 2020;41:542–6. [Google Scholar]

- [53].Xu XW, Wu XX, Jiang XG, et al. Clinical findings in a group of patients infected with the 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-Cov-2) outside of Wuhan, China: retrospective case series. BMJ 2020;368:m606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Yan S, Song X, Lin F, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in Hainan, China. medRxiv 2020;2020.2003.2019.20038539. [Google Scholar]

- [55].Yang W, Cao Q, Qin L, et al. Clinical characteristics and imaging manifestations of the 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a multi-center study in Wenzhou city, Zhejiang, China. J Infect 2020;80:388–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Yang XB, Yu Y, Xu JQ, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med 2020;pii: S2213-2600(2220)30079-30075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Yao N, Wang SN, Lian JQ, et al. Clinical characteristics and influencing factors of patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia combined with liver injury in Shaanxi region. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi 2020;28:E003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Yuan J, Sun YY, Zuo YJ, et al. A retrospective analysis of the clinical characteristics of 223 NCP patients in Chongqing. J Southwest Univ 2020;42:17–24. [Google Scholar]

- [59].Zhang C, Shi L, Wang FS. Liver injury in COVID-19: management and challenges. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;5:428–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Zhang G, Hu C, Luo L, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of 221 patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. medRxiv 2020;2020.2003.2002.20030452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Zhang W, Hou W, Li TC, et al. Clinical characteristics of 74 hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J Capital Med Univ 2020;41. [Google Scholar]

- [62].Zhang Y, Zheng L, Liu L, et al. Liver impairment in COVID-19 patients: a retrospective analysis of 115 cases from a single center in Wuhan city, China. Liver Inter 2020;40:2095–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Zhao W, Yu S, Zha X, et al. Clinical characteristics and durations of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Beijing: a retrospective cohort study. medRxiv 2020;2020.2003.2013.20035436. [Google Scholar]

- [64].Zhao Z, Xie J, Yin M, et al. Clinical and laboratory profiles of 75 hospitalized patients with novel coronavirus disease 2019 in Hefei, China. medRxiv 2020;2020.2003.2001.20029785. [Google Scholar]

- [65].Zheng F, Tang W, Li H, et al. Clinical characteristics of 161 cases of corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Changsha. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2020;24:3404–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Zhou F, Yu X, Tong X, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of 197 adult discharged patients with COVID-19 in Yichang, Hubei. medRxiv 2020;2020.2003.2026.20041426. [Google Scholar]

- [67].Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2020;395:1054–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Chai X, Hu L, Zhang Y, et al. Specific ACE2 expression in cholangiocytes may cause liver damage after 2019-nCoV infection. BioRxiv 2020;in press. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [69].Wan S, Yi Q, Fan S, et al. Characteristics of lymphocyte subsets and cytokines in peripheral blood of 123 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia (NCP). medRxiv 2020;2020.2002.2010.20021832. [Google Scholar]

- [70].Wang XH, F. XX, Cai ZX. Comorbid chronic diseases and acute organ injuries are strongly correlated with disease severity and mortality among COVID-19 Patients: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Research 2020;2402961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Mantovani A, Beatrice G, Dalbeni A. Coronavirus disease 2019 and prevalence of chronic liver disease: a meta-analysis. Liver Int 2020;40:1316–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]