Abstract

Objective This study systematically reviews the outcomes of surgical repair of triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC) tears. Existing surgical techniques include capsular sutures, suture anchors, and transosseous sutures. However, there is still no consensus as to which is the most reliable method for ulnar-sided peripheral and foveal TFCC tears.

Methods A systematic review of MEDLINE and EMBASE was performed according to PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines. The focus was on traumatic Palmer 1B ulna-sided tears. Twenty-seven studies were included, including three comparative cohort studies.

Results There was improvement in all functional outcome measures after repair of TFCC tears. The outcomes following peripheral and foveal repairs were good overall: Mayo Modified Wrist Evaluation (MMWE) score of 80.1 and 85.1, Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH) score of 15.7 and 15.8, grip strength of 80.3 and 92.7% (of the nonoperated hand), and pain intensity score of 2.1 and 1.7, respectively. For peripheral tears, transosseous suture technique achieved better outcomes compared with capsular sutures in terms of grip strength, pain, Patient-Rated Wrist Evaluation (PRWE), and DASH scores (grip 85.8 vs. 77.7%; pain 1.5 vs. 2.2; PRWE 11.6 vs. 15.8; DASH 14.4 vs. 16.1). For foveal tears, transosseous sutures achieved overall better functional outcomes compared with suture anchors (MMWE 85.4 vs. 84.9, DASH 10.9 vs. 20.6, pain score 1.3 vs. 2.1), but did report slightly lower grip strength than the group with suture anchors (90.2 vs. 96.2%). Arthroscopic techniques achieved overall better outcomes compared with open repair technique.

Conclusion Current evidence demonstrates that TFCC repair achieves good clinical outcomes, with low complication rates.

Level of Evidence This is a Level IV, therapeutic study.

Keywords: triangular fibrocartilage, TFCC, repair, foveal, peripheral tear, systematic review

Triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC) tears are a common source of pain on the ulnar side of the wrist and is often associated with decreased grip strength and impaired function. In addition, the TFCC, especially through its foveal attachment, contributes to the stability of the distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ). 1 2 3 TFCC tears can be classified according to the location and cause. 4 The Palmer classification delineates tears into two categories—acute/traumatic (Type 1) and degenerative tears (Type 2). Type 1 tears are further divided into four subtypes (1A to 1D) depending on the location of the tear. Type 1B injuries are tears located at the ulnar side of the TFCC. These tears may be repairable due to the vascularity in the peripheral one-third of the TFCC. 4 5

The TFCC is composed of superficial and deep components. The superficial or distal component is a hammock structure attached to the ulnar collateral ligament and the deep or proximal component is a triangular ligament, or ligamentum subcruentum, attached to the ulnar fovea by palmar and dorsal limbs, forming the volar and dorsal distal radioulnar ligaments. 6 Previous anatomical and biomechanical studies have shown that the deep component plays a greater role in stability of the DRUJ compared with the superficial component of the TFCC. 7 As the Palmer classification does not divide Type 1B tears into foveal or superficial tears, there can be a lack of standardization of nomenclature between studies. Atzei et al proposed a more clinically relevant, treatment-based classification of Type 1B tears. In this classification, the distal (peripheral) and proximal (foveal) components of the TFCC are incorporated and contrasted. Class 1 tears consist of a repairable distal tear, class 2: a repairable complete tear, class 3: a repairable proximal tear, class 4: a nonrepairable tear, and class 5: an arthritic DRUJ. 8 9 10

Pain caused by TFCC tears may be treated by nonoperative means including rest, splinting, cortisone injections, and activity modification. 11 However, surgery is considered when nonoperative measures fail and this includes arthroscopic debridement, arthroscopic/arthroscopic-assisted repair (outside-in, inside-out, all-inside), or open repair. 8 Ulnar shortening osteotomy (USO) can also be performed to unload the ulnocarpal joint; in the event there is associated ulna abutment from ulna positive variance. 12

Various TFCC repair techniques have been discussed and the type of repair chosen depends on the location of the TFCC tear. 8 Peripheral tears are often repaired using traditional suture techniques to reattach the superficial portion of the TFCC to the dorsal ulnocarpal capsule and the extensor carpi ulnaris (ECU) tendon subsheath. 13 Foveal avulsions are frequently repaired by reattachment to the foveal insertion using transosseous sutures passed through drill holes or suture anchors. 8 14 15 Both repairs can be performed with either open or arthroscopic techniques. However, to date, despite the various techniques that have been described, there is still no clear consensus as to which technique provides the most optimum results. 3 16 17 Therefore, it was the aim of this study to systematically review the current literature and examine the functional and clinical outcomes as well as complications of surgical repair techniques for traumatic Palmer Type 1B TFCC tears.

Methods

Study Selection Protocol

This systematic review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Two authors (E.H.L., K.S.) systematically searched the electronic databases PubMed MEDLINE and Ovid MEDLINE (1946–2020) and Ovid EMBASE (1980–2020) using the search strategy in Table 1 . The search results were up to date as of March 2020. Two authors independently selected studies which met the inclusion criteria based on title and abstract. Both authors reviewed the full-text versions of selected studies and independently extracted the outcome data. Any discrepancies were resolved by a third author (E.T.E.).

Table 1. Search strategy.

| 1 Triangular fibrocartilage/or TFCC.mp. 2 repair.mp. 3 treatment.mp. 4 surgery.mp. 5 opera*.mp. 6 result.mp. 7 outcome.mp. 8 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 9 1 and 8 10 limit 9 to english language |

Abbreviation: TFCC, triangular fibrocartilage complex.

Eligibility Criteria

Clinical studies were considered if they included adult patients over the age of 16 years with a Palmer Type 1B TFCC tear treated by surgical repair. All clinical studies or case series which included subjective or objective outcome measures were considered. Studies were excluded if (1) clinical outcomes were not reported, (2) study patients had nonrepairable tears or (3) study patients suffered concomitant injuries such as distal radius fractures or underwent DRUJ reconstruction, (4) the article is not in the English language, and (5) the article is an editorial, conference abstract, or review article.

Data Exaction/Outcome Measures

Data were extracted using standardized forms, which included patient characteristics, intervention, comparisons, outcomes, study setting, sample size, and follow-up. Validated patient-reported outcomes and functional outcomes were collected. This included data on the patient's preoperative and postoperative pain level based on the visual analogue scale (VAS) and numerical rating scale (NRS), grip strength as measured by a dynamometer, functional outcome based on the Modified Mayo Wrist Evaluation (MMWE) score, the Patient-Rated Wrist Evaluation (PRWE) score, and Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (DASH) score. Grip strength was reported as a percentage of the contralateral side. Both preoperative and postoperative measurements were collected.

VAS and NRS are both validated patient-reported measures of pain intensity consisting of a continuous scale that ranges from 0, representing “no pain,” to 10, which represents “worst imaginable pain.” The NRS is a segmented numeric version of the VAS. 18 19 The MMWE assesses the patient's (1) pain, (2) grip strength, (3) range of motion, and (4) return to employment. The total score, based on the clinician's assessments, ranges from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating a better result. 20 PRWE is a 15-item questionnaire that allows patients to rate their wrist pain and disability. It consists of two subscales: (1) pain intensity, and (2) function in specific activity and function in usual activity. The maximum score tallied is 100 which represents the greatest disability. 21 The DASH is a validated self-administered questionnaire designed to measure pain symptoms and disability related to the upper extremity. The QuickDASH is an abbreviated version of DASH, and contains 11 questions to measure the severity of symptoms. In both DASH and QuickDASH, the total score is placed on a scale between 0 (no disability) and 100 (most severe disability). 22 23 24

Grip strength as measured by a dynamometer was reported as a percentage of the strength on the contralateral, unoperated hand. Data on postoperative complications were also extracted from the included studies. This includes reoperations, altered sensation, and recurrent DRUJ instability.

Assessment of Study Quality

The Moga tool was specifically developed to assess the methodological quality of case series using the Modified Delphi technique. Using this tool, each study was scored out of 18 points. A study with 14 or more points was of acceptable quality. 25

SPSS Statistics (IBM, New York, NY) was used for calculation of weighted averages of the continuous data we collected. Meta-analysis was not done due to heterogeneity of our sample.

Results

Study Selection

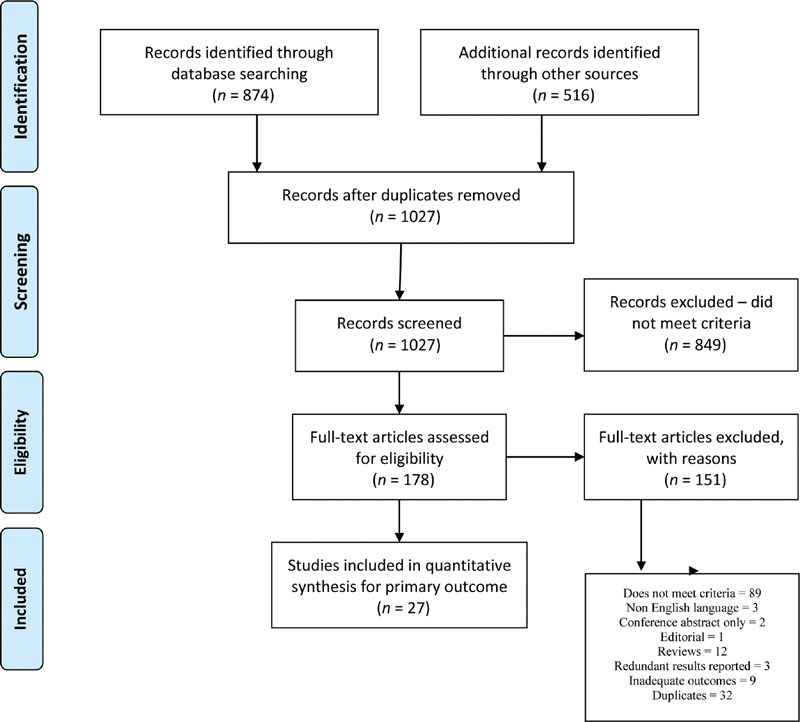

A total of 1,390 articles were found from both databases. After removing duplicates, 1,027 records were screened based on title and abstract. A total of 178 articles were selected for full-text review. One hundred and fifty articles were excluded with reasons provided. Fig. 1 demonstrates the PRISMA diagram for the systematic review.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA diagram. PRISMA, preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses. 57

Quality Assessment

A total of 27 articles met the inclusion criteria. 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 All studies were retrospective cohort or case series and achieved a Moga score of 14 or higher. There were five Level III and 22 Level IV studies. Characteristics of the included studies are shown in Tables 2 and 3 .

Table 2. Studies characteristics of peripheral TFCC repairs.

| Author/Study | Study design | Level of evidence | Sample size | Mean age (years) | Mean follow-up time (months) | Time from injury to surgery (months) | Type of TFCC injury | Type of repair | Repair technique |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anderson et al 2008 | Retrospective cohort study | III | O: 39 A: 37 |

33 | O: 53 A: 32 |

Peripheral | Open and Arthroscopic | O: Transosseous suture A: Capsular suture (outside in) |

|

| Badia and Khanchandani 2007 | Retrospective case series | IV | 23 | 35 | 17 | Peripheral | Arthroscopic | Capsular suture (outside in) | |

| Bayoumy et al 2015 | Retrospective case series | IV | 37 | 23.3 | 24 | 11.1 | Peripheral | Arthroscopic | Capsular suture (outside in) |

| Degreef et al 2005 | Retrospective case series | IV | 52 | 32 | 16 | Peripheral | Arthroscopic | Capsular suture (outside in) | |

| Haugstvedt and Husby 1999 | Retrospective case series | IV | 20 | 32 | 42 | 25 | Peripheral | Arthroscopic | Capsular suture (outside in) |

| Lee et al 2019 | Retrospective cohort study | III | 80 | 37 | 23.7 | 6.4 | Peripheral | Arthroscopic | Transosseous suture |

| McAdams et al 2009* | Retrospective case series | IV | 9 | 20.8 | 32.2 | 52.1 | Peripheral | Arthroscopic | Capsular suture (inside out) |

| Millants et al 2002 | Retrospective case series | IV | 35 | 31 | 58 | Peripheral | Arthroscopic | Capsular suture | |

| Papapetropoulos et al 2010 | Retrospective cohort study | IV | 27 | 37 | 24 | 15 | Peripheral | Arthroscopic | Capsular suture (outside in) |

| Roh et al 2018 | Retrospective case series | IV | 60 | 32 | 12 | 5 | Peripheral | Arthroscopic | Capsular suture (outside in) |

| Ruch et al 2005 | Retrospective case series | IV | 35 | 34 | 29 | Peripheral | Arthroscopic | Capsular suture (outside in) | |

| Sarkissian et al 2019 | Retrospective case series | IV | 11 | 36 | 84 | Peripheral | Arthroscopic | Capsular suture | |

| Wolf et al 2012 | Retrospective case series | IV | 40 | 38 | 58 | Peripheral | Arthroscopic | Capsular suture | |

| Yao and Lee 2011 | Retrospective case series | IV | 12 | 42 | 17.5 | Peripheral | Arthroscopic | Capsular suture |

Abbreviations: A, arthroscopic; O, open; TFCC, triangular fibrocartilage complex.

Note: In the above studies, only ulnar-sided TFCC repairs were included.

Table 3. Studies characteristics of foveal TFCC repairs.

| Author/Study | Study design | Level of evidence | Sample size | Mean age (years) | Mean follow-up time (months) | Time from injury to surgery (months) | Type of TFCC injury | Type of repair | Repair technique |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abe et al 2018 | Retrospective case series | III | O: 8 A: 21 |

O: 22 A: 34 |

34.4 | O: 11 A: 8.5 |

Foveal | Open and arthroscopic | Transosseous suture |

| Atzei et al 2015 | Retrospective case series | IV | 48 | 34 | 33 | 11 | Foveal | Arthroscopic | Suture anchor |

| Auzias et al 2020 | Retrospective case series | IV | 24 | 41 | 44 | Foveal | Arthroscopic | Suture anchor | |

| Chou et al 2003 | Retrospective case series | IV | 8 | 31 | 48 | 45.3 | Foveal | Arthroscopic | Suture anchor |

| Dunn et al 2019 | Retrospective case series | IV | 15 | 21 | 46 | 3.8 | Foveal | Arthroscopic | Transosseous suture |

| Iwasaki et al 2011 | Retrospective case series | IV | 12 | 31 | 30 | 8 | Foveal | Arthroscopic | Transosseous suture |

| Jegal et al 2016 | Retrospective case series | IV | 19 | 37 | 31 | 6 | Foveal | Arthroscopic | Transosseous suture |

| Jung et al 2019 | Retrospective cohort study | III | 42 | 35.3 | 26 | Foveal | Arthroscopic | Transosseous suture | |

| Kim et al 2013 | Retrospective case series | IV | 15 | 30 | 29 | 12.7 | Foveal | Arthroscopic | Suture anchor |

| Luchetti et al 2014 | Retrospective cohort study | III | O: 24 A: 25 |

33 | 31 | Foveal | Open and arthroscopic | Suture anchor | |

| Moritomo 2015 | Retrospective case series | IV | 21 | 31 | 26 | Foveal | Open | Suture anchor | |

| Park et al 2018 | Retrospective case series | IV | 16 | 29.8 | 31.1 | 11 | Foveal | Arthroscopic | Transosseous suture |

| Shinohara et al 2013 | Retrospective case series | IV | 10 | 27 | 31 | 10 | Foveal | Arthroscopic | Transosseous suture |

Abbreviations: A, arthroscopic; O, open; TFCC, triangular fibrocartilage complex.

Note: In the above studies, only ulnar-sided TFCC repairs were included.

Study and Patient Characteristics

There was a total of 825 patients (mean age = 32.2 years) reported from 27 articles. Three papers were comparative studies and included two study groups. 26 40 48 Fourteen studies reported peripheral TFCC repairs 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 and 13 studies reported foveal avulsions of the TFCC. 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 As the pathoanatomy of these tears and repair techniques differ, the outcomes of peripheral and foveal tears were analyzed separately.

Clinical Outcome Measures

Repair Techniques and Pooled Analysis of Outcome Measures

Peripheral Tears of the TFCC

Fourteen studies reported peripheral TFCC repairs in 517 patients ( Table 2 ). The mean age of study patients was 33.1 years; their average follow-up time is 34.8 months. The time between injury and surgical repair was reported in six papers, and the average is 19.1 months. Repair techniques include a combination of outside-in and inside-out capsular sutures, and sutures pulled through a bone tunnel in the ulna (transosseous suture). Thirteen studies reported only arthroscopic techniques and one study compared arthroscopic and open techniques. Thus, there was a sample size of 478 patients who underwent arthroscopic repair and 39 who had open repair. Thirteen studies 26 27 28 29 30 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 consisting of 398 patients reported on an outside-in or inside-out suture secured to the joint capsule. Two studies 26 31 (119 patients) described sutures secured through ulnar transosseous tunnels.

Outcomes of Peripheral Repair

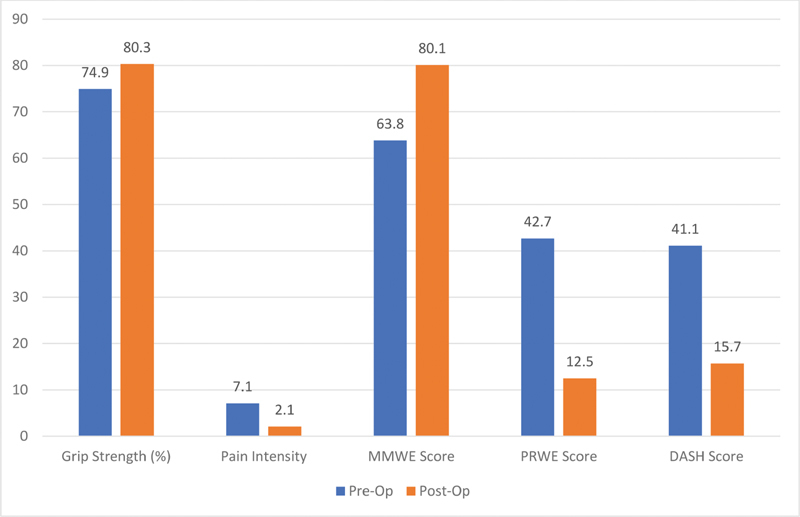

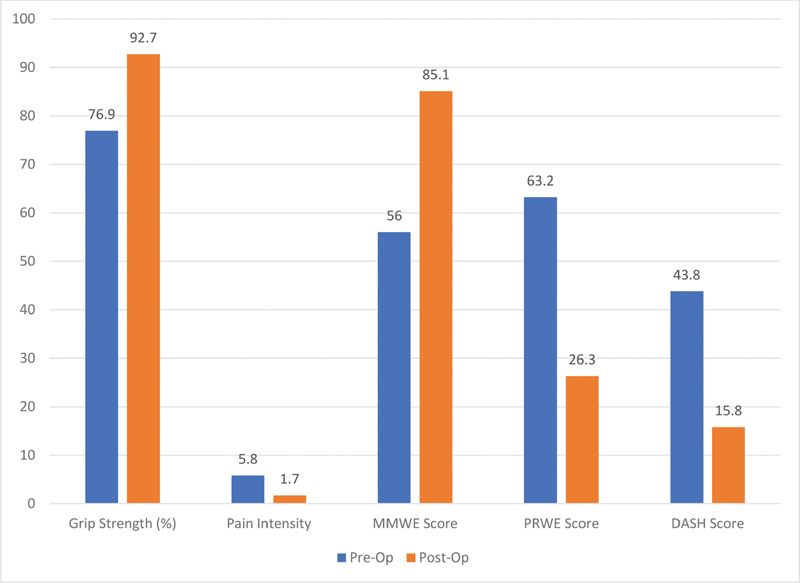

Fig. 2 demonstrates an improvement in the pooled preoperative to postoperative functional outcomes for peripheral repairs for all measures. MMWE showed an improvement from a mean of 63.8 preoperatively to 80.1 postoperatively. Furthermore, the DASH score improved from 41.1 to 15.7. There was a gain in grip strength from 74.9 to 80.3% of the contralateral side. Reported pain intensity decreased from 7.1 to 2.1 ( Table 4 ).

Fig. 2.

Peripheral tear repair outcomes—preoperative versus postoperative.

Table 4. Outcomes of peripheral TFCC repairs.

| Author/Study | Pain score (VAS/NRS) | Grip strength (% of contralateral) | MMWS | PRWE | DASH | Complications | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Reoperations | Neuropraxia | DRUJ instability | |

| Anderson et al 2008 (Open) | 1.5 | 72 | 73 | 65.6 | 71.2 | 16.7 | 11 | 14 | 8 | ||||

| Anderson et al 2008 (Arthroscopic) |

2.6 | 66 | 71 | 63.5 | 70.6 | 20.7 | 9 | 8 | 5 | ||||

| Badia and Khanchandani 2007 | 81 | 0 | 0 | Excluded | |||||||||

| Bayoumy et al 2015 | 7.6 | 2.9 | 82.5 | 89 | 62.1 | 91.2 | 29.9 | 10.2 | 0 | 1 | |||

| Degreef et al 2005 | 2.4 | 80 | 17.3 | 0 | 2 | ||||||||

| Haugstvedt and Husby 1999 | 3.1 | 83 | Excellent: 35% Good: 35% Fair: 20% Poor: 10% |

5 | |||||||||

| Lee et al 2019 | 72.5 | 92.1 | 42.7 | 11.6 | 34.4 | 13.3 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| McAdams et al 2009 a | 50.7 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||

| Millants et al 2002 | 0.6 | 15 | |||||||||||

| Papapetropoulos et al 2010 | 6.3 | 1.4 | 85.5 | 64 | 31.7 | 9.8 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||||

| Roh et al 2018 | 6.8 | 2.1 | 63.8 | 27.8 | 2 | 3 | 8 | ||||||

| Ruch et al 2005 | 73 | 12 | |||||||||||

| Sarkissian et al 2019 | 1.7 | 98 | 81 | 12.3 | 41 | 10 | 0 | 0 | Excluded | ||||

| Wolf et al 2012 | 7.5 | 2.5 | 87 | 35 | 14 | 0 | 5 | Excluded | |||||

| Yao and Lee 2011 | 64.4 | 19 | 11 | 1 | Excluded | ||||||||

Abbreviation: DASH, Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand; DRUJ, distal radioulnar joint; MMWS, modified Mayo Wrist score; NRS, numerical rating scale; PRWE, patient-rated wrist evaluation; TFCC, triangular fibrocartilage complex; VAS, visual analogue scale.

Note: In the above studies, only ulnar-sided TFCC repairs were included.

As aforementioned, 13 studies reported capsular repair techniques, which were all done arthroscopically. The only study that reported an open repair approach used a transosseous repair technique. 26 The other study that repaired the TFCC injury using a bone tunnel did so via an arthroscopic-assisted technique. 31

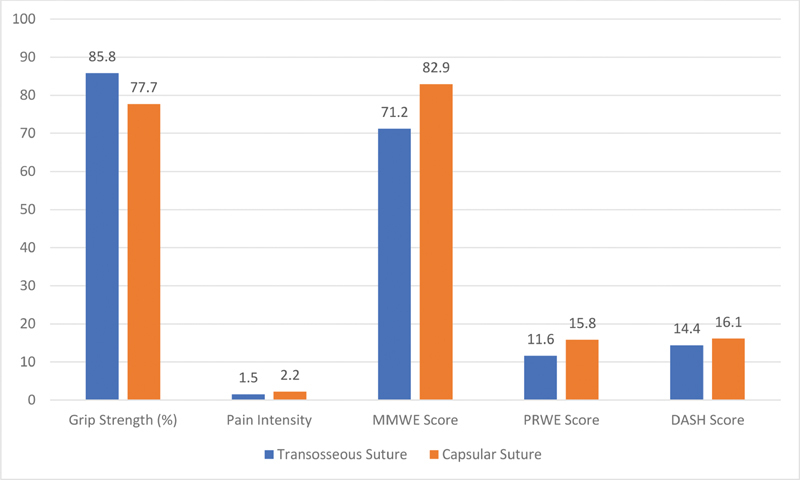

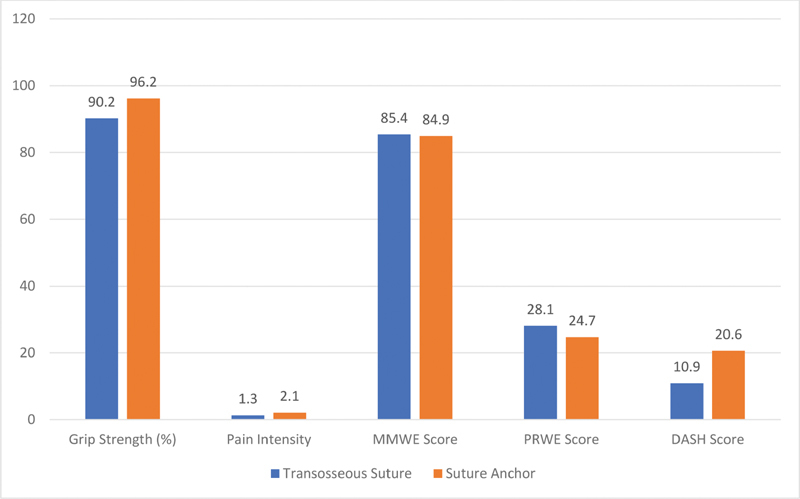

Compared with transosseous sutures ( n = 119), arthroscopic capsular suture repair ( n = 398) achieved better MMWE scores (82.9 vs. 71.2). However, transosseous technique demonstrated a slightly better DASH score (14.4 vs. 16.1), better postoperative grip strength (85.8 vs. 77.7%), and better postoperative pain (1.5 vs. 2.2). Postoperative outcomes of different techniques of peripheral TFCC repair are shown in Figs. 3 and 4 .

Fig. 3.

Peripheral tear repair outcomes—transosseous sutures versus capsular sutures.

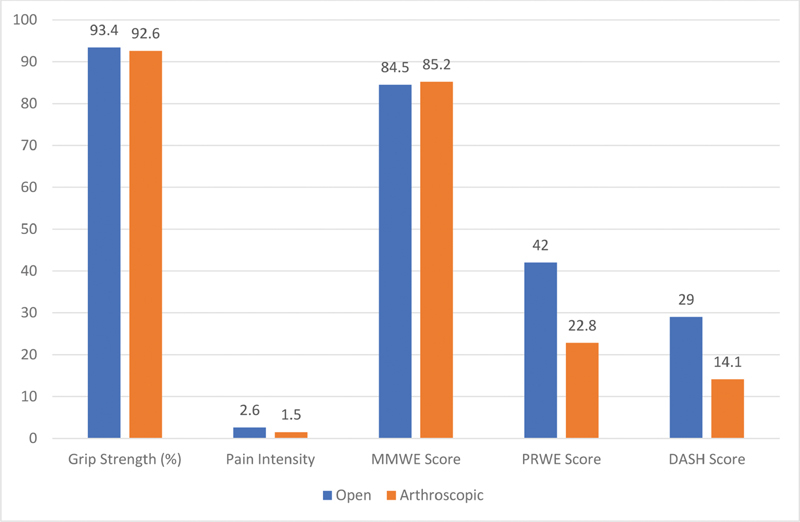

Fig. 4.

Peripheral tear repair outcomes—arthroscopic versus open.

Foveal Avulsion of the TFCC

Thirteen studies reported outcomes of foveal repairs in 308 patients ( Table 5 ). The patients' mean age was 31.3 years; they were followed up for an average period of 33.7 months. The period before surgical repair was reported in 10 studies, and the average duration was 12.7 months. Foveal avulsions were reattached using either suture anchors (six studies, n = 165) 41 42 43 47 48 49 or sutures through ulnar transosseous tunnels (seven studies, n = 143). 40 44 45 46 50 51 52 Twelve studies with 255 patients reported arthroscopic techniques, and three studies with 53 patients reported open techniques. Two of the three papers on open repair were comparative studies involving both arthroscopic and open approach groups. 40 48 One study reported only an open technique. 49

Table 5. Outcomes of foveal TFCC repairs.

| Author/Study | Pain score (VAS/NRS) | Grip strength (% of contralateral) | MMWS | PRWE | DASH | Complications | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Reoperations | Neuropraxia | DRUJ instability | |

| Abe et al 2018 (Open) | 10 | 0 | 81.6 | 96.9 | 100% Excellent | 7.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Abe et al 2018 (Arthroscopic) | 10 | 0.2 | 80.2 | 97.6 | Excellent: 85.7% Good: 14.3% |

5.7 | 0 | 0 | 3 | ||||

| Atzei et al 2015 | 3 | 1 | 92.7 | 103.6 | 48 | 87 | 42 | 15 | 0 | 5 | 4 | ||

| Auzias et al 2020 | 7.4 | 1.3 | 83.7 | 9.3 | 52.1 | 21.7 | 0 | 6 | 4 | ||||

| Chou et al 2003 | 55 | 88 | 62 | 88 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Dunn et al 2019 | 1.3 | 84.3 | 9.7 | 1 | Excluded | ||||||||

| Iwasaki et al 2011 | 7.2 | 1.0 | 92.7 | 106.3 | 92.5 | 59.5 | 7.7 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Jegal et al 2016 | 71 | 89 | Excellent: 36.8% Good: 52.6% Fair: 10.5% |

53 | 19 | 44 | 11 | 0 | |||||

| Jung et al 2019 | 4.3 | 2.4 | 69.5 | 83.4 | 72 | 82.5 | 58.2 | 32.2 | 40.3 | 15.9 | 0 | 0 | |

| Kim et al 2013 | 79.3 | 82.9 | 64 | 84 | 28.4 | 16.6 | 3 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| Luchetti et al 2014 (Open) | 7 | 4 | 48 | 78 | 69 | 42 | 58 | 36 | 3 | 0 | 4 | ||

| Luchetti et al 2014 (Arthroscopic) | 7 | 3 | 47 | 81 | 54 | 23 | 39 | 18 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Moritomo 2015 | 2 | 65 | 92 | 43 | 92 | 10 | Mild: 4 Moderate: 1 |

||||||

| Park et al 2018 | 3.7 | 0.8 | 57.3 | 79.6 | 61.8 | 83.4 | 35 | 9.9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Shinohara et al 2013 | 84 | 98 | 70 | 94 | 3 | 0 | 3 | ||||||

Abbreviation: DASH, Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand; DRUJ, distal radioulnar joint; NRS, numerical rating scale; PRWE, patient-rated wrist evaluation; TFCC, triangular fibrocartilage complex; VAS, visual analogue scale.

Suture Anchor Foveal Repair ( n = 165 Patients)

Atzei et al, Luchetti et al, and Kim et al described an arthroscopic-assisted foveal repair of the two dorsal and volar radioulnar ligament limbs via a suture anchor to the fovea. 41 47 48 This was performed via suture shuttles using an outside-in technique through a direct foveal portal. Atzei et al described the direct foveal portal to be 1 cm proximal to the 6U portal, on the volar ulnar aspect of the wrist. A 2-cm mini-open incision over the ECU tendon may be used to avoid the dorsal sensory branch of the ulnar nerve. 41

Luchetti et al compared the outcomes of open and arthroscopic foveal repair. 48 The open foveal repair was done via an open dorsal approach described by Garcia-Elias using a 4-cm central dorsal skin incision and a suture anchor into the ulnar fovea. 53 Both groups had improvement of pain scores, MMWE, DASH, and PRWE scores, and significantly better DASH scores in the arthroscopic group compared with the open group.

Transosseous Foveal Repair ( n = 143 Patients)

Seven papers reported a transosseous repair technique. 40 44 45 46 50 51 52 Iwasaki et al performed arthroscopic-assisted transosseous repair using a guiding device through the four to five portal, targeting the fovea. An outside-in technique for the suture shuttle was then utilized, with the sutures finally tied onto the ulnar periosteum over the proximal entrance of the osseous tunnel. 45 Jegal et al reported a similar technique, utilizing an Aiming Guide inserted through the four to five portal directed at the fovea to create bone tunnels from proximal ulnar cortex. The sutures entering through these transosseous tunnels would be tied down and fixed by knotting over the joint capsule. 46 Park et al and Jung et al inserted the aiming guide through 6R portal toward the fovea. Under arthroscopic control, they passed the suture which grasped the TFCC through the transosseous tunnel and secured with a suture anchor proximal to the trajectory of the bone tunnel. 50 52

Shinohara et al and Abe et al both utilized a small incision to expose the ulnar side of ulnar neck and drilled two parallel osseous bone tunnels directed at fovea. Suture fed through tunnels via the portals then tied to the entrance of the bone tunnels, thus directly attaching the TFCC to the fovea. 40 51 Dunn et al performed the reattachment in a similar technique, securing the TFCC in a horizontal mattress, tensioning through the tunnel and fixed it with a suture anchor proximal to the bone tunnel. 44

Outcomes of Foveal Repair

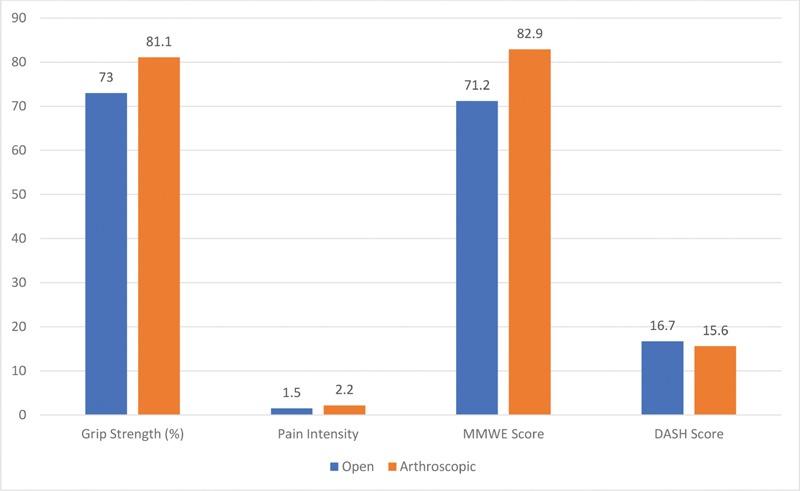

The weighted averages of preoperative to postoperative functional outcomes for foveal repairs are shown in Fig. 5 . The MMWE and PRWE scores improved from a mean of 56 to 85.1, and 63.2 to 26.3, respectively. The DASH score improved from 43.8 to 15.8. Grip strength improved from 76.9 to 92.7%. Reported pain intensity as measured by VAS or NRS scores improved from 5.8 to 1.7 ( Table 5 ).

Fig. 5.

Foveal tear repair outcomes—preoperative and postoperative.

Transosseous sutures achieved a similar outcome compared with suture anchors, with respect to MMWE (85.4 vs. 84.9), but overall had a much better DASH score (10.9 vs. 20.6) and reported pain (1.3 vs. 2.1). On the other hand, the suture anchor group reported slightly better postoperative grip strength (96.2 vs. 90.2% of the contralateral side), and PRWE score (24.7 vs. 28.1). Postoperative outcomes of different techniques of peripheral TFCC repair are shown in Figs. 6 and 7 .

Fig. 6.

Foveal tear repair outcomes—suture anchor versus transosseous suture.

Fig. 7.

Foveal tear repair outcomes—arthroscopic versus open.

Postoperative Immobilization and Rehabilitation (For Both Peripheral and Foveal Repairs)

All studies immobilized patients from a range of 3 to 8 weeks, using long arm or sugar tong splints, or cast, with some authors changing to a short arm cast or removable wrist splint after 2 to 4 weeks. 27 28 29 32 34 39 40 41 42 45 47 49 52 Four studies immobilized the DRUJ with K-wires for 3 to 6 weeks after a peripheral repair. 26 29 33 47 Return to heavy activities and sport was at 3 to 6 months after surgery. 28 32 40 41 43 46 48 50

Complications

Reoperation

Reoperation case incidence was reported in 23 papers—11 involving peripheral tears, and 12 involving foveal injuries ( Tables 4 , 5 , 6 ). While 14 studies reported no reoperations, nine studies outlined the secondary procedures that were required. Studies on peripheral injuries saw a higher incidence of reoperation than studies on foveal avulsions (28 cases, 7.9% vs. 12 cases, 5.5%).

Table 6. Complications.

| Peripheral | Reoperations | Altered sensation | Recurrent DRUJ instability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total cases in peripheral | 28 | 34 | 21 |

| No. of studies reported | 11 | 11 | 5 |

| No. of pts in studies reported | 355 | 426 | 174 |

| % Complication rate | 7.9% | 8.0% | 12.1% |

| Total no. of patients | 517 | ||

| Foveal | Reoperations | Altered sensation | Recurrent DRUJ instability |

| Total cases in foveal | 12 | 23 | 24 |

| No. of studies reported | 12 | 14 | 12 |

| No. of pts in studies reported | 220 | 289 | 232 |

| % Complication rate | 5.5% | 8.0% | 10.3% |

| Total no. of patients | 308 | ||

Abbreviation: DRUJ, distal radioulnar joint.

Five patients required subsequent USO. 30 39 47 Ten patients underwent diagnostic arthroscopy for persistent wrist symptoms. 30 39 48 During the secondary arthroscopy, it was shown that six of these patients had healing of the TFCC repair. 30 39 Four of these patients needed additional operations to correct other abnormalities—Darrach's procedure, proximal row carpectomy due to Kienbock's disease, and USO ( n = 2). In the two remaining patients, no cause for pain was identified.

In four cases (three with open approach, one arthroscopically) reported by Luchetti et al, the patient underwent diagnostic arthroscopy due to persistent DRUJ instability. 48 The arthroscopy showed suture rupture with radioulnar ligament detachment at the site of previous repair. Subsequent reconstruction of the DRUJ was needed in 13 patients as reported by Anderson et al due to persistent DRUJ instability—eight of 39 patients(2.1%) in the open repair group, five of 36 patients (1.4%) in the arthroscopic repair group. 26

Chou et al reported one patient who continued to experience persistent pain after arthroscopic reattachment of a foveal injury using a suture anchor. The patient needed multiple procedures including excision of an incisional neuroma, an eventually DRUJ arthrodesis. 43 Only one patient needed a complete re-operation of his TFCC repair due to re-injury from boxing 4 months following the initial procedure. 44 In 14 patients (10 with open approach, four arthroscopically), ECU tendonitis was noted in follow-up and required exploration and tenosynovectomy. 26 Two studies—both using the arthroscopic approach—reported suture removal in five patients due to irritation. 35 51

Altered Sensation

Neuropraxia of the dorsal cutaneous branch of ulnar nerve was a reported complication in 11 studies with peripheral repairs totalling 34 patients (8.0%), and in 14 papers with foveal repairs totalling 23 patients (8.0%), with nearly all resolved with conservative management at the final follow-up.

One of the three comparative studies noted higher incidence of postoperative hyperesthesia in the dorsal cutaneous branch of ulnar nerve in patients who had open repair compared with arthroscopic repair (35.9 vs. 22.2%). 26 The other two comparative studies did not note any nerve lesions. 40 48

Recurrent DRUJ Instability

Five studies ( n = 21) reported recurrent instability in patients with peripheral repairs, with an incidence of 12.1%. Thirteen patients had recurrent DRUJ instability after capsular repair and eight patients had recurrent DRUJ instability after transosseous suture repair. Twelve studies of foveal repairs reported recurrent DRUJ instability in 24 patients (10.3%)—21 cases with suture anchors and three cases with transosseous sutures.

In four papers, the DRUJ instability was noted to be mild in 14 of the 15 patients with this complication—being described as slightly looser than the contralateral side. 40 42 49 51 The remaining patient was reported to have moderate instability. 49

Five studies listed DRUJ instability as an exclusion criterion. 27 37 38 39 44 In Badia and Khanchandani, DRUJ instability was an indication for a different approach of repair than the one studied. 27

Soft Tissue Complications

Iwasaki et al and Kim et al reported postoperative ECU tendonitis in three patients of their cohorts (11.1%)—all resolved with conservative management or cortisone injection. 45 47 Extensor digiti minimi irritation (2.7%, n = 1) 28 and mild irritation surrounding suture knots (47.4%, n = 9,) 46 were noted, and resolved without surgical intervention. Other complications included chronic regional pain syndrome (8.3%, n = 2) 42 and hypertrophic scarring (2.5%, n = 1). 38

Discussion

This systematic review of surgical repair of peripheral and foveal TFCC tears shows that surgery can achieve good functional outcomes and a low complication rate. In peripheral tears, transosseous suture repair achieved improved outcomes compared with capsular sutures in most functional outcomes. In foveal tears, transosseous sutures achieved improved outcomes compared with suture anchors in DASH and pain scores, while patients who underwent suture anchors had slightly higher grip strength and PRWE scores. Overall, arthroscopic techniques demonstrated overall better functional outcomes compared with open techniques.

The foveal component of the TFCC contributes to the stability of the DRUJ. 3 8 Hence, evidence of DRUJ laxity is often associated with avulsion or attenuation of the foveal attachment of the TFCC. 54 Accordingly, in 11 of the 13 studies of patients with foveal avulsions, all patients had evidence of DRUJ instability. One paper on arthroscopic repair of foveal injuries excluded patients with DRUJ instability, due to their preference for open techniques in foveal reattachment surgery. 44

The distal or peripheral component contributes less to the stability of the DRUJ. In the Atzei classification, class 1 distal or peripheral tears should demonstrate no or slight DRUJ instability with the ballottement test. 9 In the studies describing peripheral tears, only six of 14 studies included patients with DRUJ instability. 26 29 30 31 32 35 In three studies, DRUJ instability was not examined or reported. 33 34 36 Recurrent instability after TFCC repair was reported in five studies as a complication, and a higher recurrence rate was found in patients managed with capsular sutures compared with transosseous sutures ( n = 13 vs. n = 8). This suggests that capsular sutures may be inadequate for management if a foveal tear was inadvertently missed.

This study is a current and comprehensive systematic review of the literature on functional and clinical outcomes of peripheral and foveal TFCC repairs. However, the current evidence is based on retrospective cohort studies and case series. Thus, our conclusions are limited by the overall low levels of evidence from the included studies. Surgical techniques vary considerably between authors. Variations exist within repair types (e.g., knotless or knotted capsular sutures and knotless or knotted suture anchors). Some authors use all-arthroscopic or arthroscopic-assisted methods, and some utilize mini-open approaches. Outcome reporting between studies was heterogenous as not all studies reported all the functional outcomes studied. The limitation of using the Palmer classification which does not include a separate class for foveal avulsions leads to a lack of standardization in the nomenclature surrounding peripheral tears. It should be noted that the included studies tried to control for confounding factors by excluding patients with concomitant injuries from the study population, and by using validated tools for measuring outcome. However, there remains a significant heterogeneity in demographics of the patients, inclusion criteria, duration of symptoms prior to surgery, and postoperative follow-up. This is a limitation that should be considered when interpreting the conclusions on outcomes and complication rates.

Recent reviews on surgical management of TFCC injuries observed that both open and arthroscopic repair techniques achieved improvement in patient-reported and functional outcomes, and there was no evidence of one technique being superior to another. 3 16 17 Nakamura et al also found that both open and arthroscopic transosseous repair techniques were reliable and successful in treating foveal detachments of the TFCC. 15 Although they reported better overall outcomes in the group that underwent arthroscopic repair compared with open repair, it should be noted that there was a significant discrepancy in their sample sizes—733 patients in arthroscopic repair group and 92 in the open repair group. As such, observations from a direct comparison between these two groups should be interpreted with caution. The relative scarcity of studies on open repair techniques and comparative studies between the two techniques is also noted in recent publications. 3 11 17

DRUJ instability, both as a preoperative finding and postoperative outcome, was assessed with only clinical maneuvers such as the ballottement test. 55 Determination of the severity of DRUJ instability or subluxation continues to be difficult to standardize, due to the lack of an objective and validated measure. Axial MRI imaging was used as a tool to measure DRUJ subluxation by measuring the displacement of the ulnar head with respect to the radius. 56 Furthermore, a Push Pull gauge (NK-100, HANDPI, China) was a tool utilized by Lee et al to apply uniform stress in anteroposterior and posteroanterior directions to the ulnar head while taking lateral stress views in both injured and uninjured wrists. Therefore, the authors were confident that their measurement of ulnar translation was more reliable and objective. 31

In summary, available evidence demonstrates that the various approaches to ulnar-sided TFCC repair achieve good functional and clinical outcomes, with low complication rates. However, prospective, comparative studies of high methodological quality are needed to allow for standardized evaluations between different repair techniques for ulnar-sided TFCC tears.

Funding Statement

Funding None.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest None declared.

References

- 1.Linscheid R L. Biomechanics of the distal radioulnar joint. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;(275):46–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haugstvedt J R, Berger R A, Nakamura T, Neale P, Berglund L, An K N. Relative contributions of the ulnar attachments of the triangular fibrocartilage complex to the dynamic stability of the distal radioulnar joint. J Hand Surg Am. 2006;31(03):445–451. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersson J K, Åhlén M, Andernord D. Open versus arthroscopic repair of the triangular fibrocartilage complex: a systematic review. J Exp Orthop. 2018;5(01):6. doi: 10.1186/s40634-018-0120-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palmer A K. Triangular fibrocartilage complex lesions: a classification. J Hand Surg Am. 1989;14(04):594–606. doi: 10.1016/0363-5023(89)90174-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bednar M S, Arnoczky S P, Weiland A J. The microvasculature of the triangular fibrocartilage complex: its clinical significance. J Hand Surg Am. 1991;16(06):1101–1105. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(10)80074-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakamura T, Yabe Y. Histological anatomy of the triangular fibrocartilage complex of the human wrist. Ann Anat. 2000;182(06):567–572. doi: 10.1016/S0940-9602(00)80106-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kleinman W B. Stability of the distal radioulna joint: biomechanics, pathophysiology, physical diagnosis, and restoration of function what we have learned in 25 years. J Hand Surg Am. 2007;32(07):1086–1106. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2007.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saito T, Sterbenz J M, Chung K C. Chronologic and geographic trends of triangular fibrocartilage complex repair. Hand Clin. 2017;33(04):593–605. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2017.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Atzei A, Luchetti R, Garagnani L. Classification of ulnar triangular fibrocartilage complex tears. A treatment algorithm for Palmer Type IB tears. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2017;42(04):405–414. doi: 10.1177/1753193416687479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Atzei A, Luchetti R. Foveal TFCC tear classification and treatment. Hand Clin. 2011;27(03):263–272. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2011.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee J K, Hwang J Y, Lee S Y, Kwon B C. What is the natural history of the triangular fibrocartilage complex tear without distal radioulnar joint instability? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2019;477(02):442–449. doi: 10.1097/CORR.0000000000000533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trumble T E, Gilbert M, Vedder N. Ulnar shortening combined with arthroscopic repairs in the delayed management of triangular fibrocartilage complex tears. J Hand Surg Am. 1997;22(05):807–813. doi: 10.1016/S0363-5023(97)80073-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corso S J, Savoie F H, Geissler W B, Whipple T L, Jiminez W, Jenkins N. Arthroscopic repair of peripheral avulsions of the triangular fibrocartilage complex of the wrist: a multicenter study. Arthroscopy. 1997;13(01):78–84. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(97)90213-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Atzei A, Rizzo A, Luchetti R, Fairplay T. Arthroscopic foveal repair of triangular fibrocartilage complex peripheral lesion with distal radioulnar joint instability. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg. 2008;12(04):226–235. doi: 10.1097/BTH.0b013e3181901b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakamura T, Sato K, Okazaki M, Toyama Y, Ikegami H. Repair of foveal detachment of the triangular fibrocartilage complex: open and arthroscopic transosseous techniques. Hand Clin. 2011;27(03):281–290. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Demino C, Morales-Restrepo A, Fowler J. Surgical management of triangular fibrocartilage complex lesions: a review of outcomes. J Hand Surg Glob Online. 2019;1(01):32–38. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robba V, Fowler A, Karantana A, Grindlay D, Lindau T. Open versus arthroscopic repair of 1B ulnar-sided triangular fibrocartilage complex tears: a systematic review. Hand (N Y) 2019;00(00):1–9. doi: 10.1177/1558944718815244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scott J, Huskisson E C. Graphic representation of pain. Pain. 1976;2(02):175–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hawker G A, Mian S, Kendzerska T, French M. Measures of adult pain: visual analog scale for pain (VAS pain), numeric rating scale for pain (NRS pain), Mcgill pain questionnaire (MPQ), short form Mcgill pain questionnaire (SF MPQ), chronic pain grade scale (CPGS), short form 36 bodily pain scale (SF 36 bps), and measure of intermittent and constant osteoarthritis pain (ICOAP) Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011;63 11:S240–S252. doi: 10.1002/acr.20543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cooney W P, Bussey R, Dobyns J H, Linscheid R L. Difficult wrist fractures. Perilunate fracture-dislocations of the wrist. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;(214):136–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacDermid J C, Turgeon T, Richards R S, Beadle M, Roth J H. Patient rating of wrist pain and disability: a reliable and valid measurement tool. J Orthop Trauma. 1998;12(08):577–586. doi: 10.1097/00005131-199811000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The Upper Extremity Collaborative Group (UECG) . Hudak P L, Amadio P C, Bombardier C. Development of an upper extremity outcome measure: the DASH (disabilities of the arm, shoulder, and hand) [corrected] Am J Ind Med. 1996;29(06):602–608. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0274(199606)29:6<602::AID-AJIM4>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gummesson C, Ward M M, Atroshi I. The shortened disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand questionnaire (QuickDASH): validity and reliability based on responses within the full-length DASH. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2006;7(01):44. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-7-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gabel C P, Yelland M, Melloh M, Burkett B. A modified QuickDASH-9 provides a valid outcome instrument for upper limb function. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009;10(01):161. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-10-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moga C, Guo B, Schopflocher D, Harstall C. Edmonton AB: Institute of Health Economics; 2012. Development of a Quality Appraisal Tool for Case Series Studies Using a Modified Delphi Technique. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anderson M L, Larson A N, Moran S L, Cooney W P, Amrami K K, Berger R A. Clinical comparison of arthroscopic versus open repair of triangular fibrocartilage complex tears. J Hand Surg Am. 2008;33(05):675–682. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Badia A, Khanchandani P. Suture welding for arthroscopic repair of peripheral triangular fibrocartilage complex tears. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg. 2007;11(01):45–50. doi: 10.1097/bth.0b013e3180336cec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bayoumy M A, Elkady H A, Said H G, El-Sayed A, Saleh W R. Short-term evaluation of arthroscopic outside-in repair of ulnar side TFCC tear with vertical mattress suture. J Orthop. 2015;13(04):455–460. doi: 10.1016/j.jor.2015.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Degreef I, Welters H, Milants P, Van Ransbeeck H, De Smet L. Disability and function after arthroscopic repair of ulnar avulsions of the triangular fibrocartilage complex of the wrist. Acta Orthop Belg. 2005;71(03):289–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haugstvedt J R, Husby T. Results of repair of peripheral tears in the triangular fibrocartilage complex using an arthroscopic suture technique. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 1999;33(04):439–447. doi: 10.1080/02844319950159172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee S K, Chun Y S, Bae J H, Yu Y T, Choy W S. Arthroscopic suture repair with additional pronator quadratus advancement for the treatment of acute triangular fibrocartilage complex tear with distal radioulnar joint instability. Ann Plast Surg. 2019;83(04):411–418. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000001982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McAdams T R, Swan J, Yao J. Arthroscopic treatment of triangular fibrocartilage wrist injuries in the athlete. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(02):291–297. doi: 10.1177/0363546508325921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Millants P, De Smet L, Van Ransbeeck H. Outcome study of arthroscopic suturing of ulnar avulsions of the triangular fibrocartilage complex of the wrist. Chir Main. 2002;21(05):298–300. doi: 10.1016/s1297-3203(02)00135-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Papapetropoulos P A, Wartinbee D A, Richard M J, Leversedge F J, Ruch D S. Management of peripheral triangular fibrocartilage complex tears in the ulnar positive patient: arthroscopic repair versus ulnar shortening osteotomy. J Hand Surg Am. 2010;35(10):1607–1613. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2010.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roh Y H, Yun Y H, Kim D J, Nam M, Gong H S, Baek G H. Prognostic factors for the outcome of arthroscopic capsular repair of peripheral triangular fibrocartilage complex tears. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2018;138(12):1741–1746. doi: 10.1007/s00402-018-2995-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ruch D S, Papadonikolakis A. Arthroscopically assisted repair of peripheral triangular fibrocartilage complex tears: factors affecting outcome. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(09):1126–1130. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2005.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sarkissian E J, Burn M B, Yao J. Long-term outcomes of all-arthroscopic pre-tied suture device triangular fibrocartilage complex repair. J Wrist Surg. 2019;8(05):403–407. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1688949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wolf M B, Haas A, Dragu A. Arthroscopic repair of ulnar-sided triangular fibrocartilage complex (Palmer Type 1B) tears: a comparison between short- and midterm results. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37(11):2325–2330. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2012.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yao J, Lee A T. All-arthroscopic repair of Palmer 1B triangular fibrocartilage complex tears using the FasT-Fix device. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36(05):836–842. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abe Y, Fujii K, Fujisawa T. Midterm results after open versus arthroscopic transosseous repair for foveal tears of the triangular fibrocartilage complex. J Wrist Surg. 2018;7(04):292–297. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1641720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Atzei A, Luchetti R, Braidotti F. Arthroscopic foveal repair of the triangular fibrocartilage complex. J Wrist Surg. 2015;4(01):22–30. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1544226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Auzias P, Camus E J, Moungondo F, Van Overstraeten L. Arthroscopic-assisted 6U approach for foveal reattachment of triangular fibrocartilage complex with an anchor: clinical and radiographic outcomes at 4 years' mean follow-up. Hand Surg Rehabil. 2020;39(03):193–200. doi: 10.1016/j.hansur.2020.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chou K H, Sarris I K, Sotereanos D G. Suture anchor repair of ulnar-sided triangular fibrocartilage complex tears. J Hand Surg [Br] 2003;28(06):546–550. doi: 10.1016/s0266-7681(03)00173-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dunn J, Polmear M, Daniels C, Shin E, Nesti L. Arthroscopically assisted transosseous triangular fibrocartilage complex foveal tear repair in the united states military. J Hand Surg Glob Online. 2019;1(02):79–84. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Iwasaki N, Nishida K, Motomiya M, Funakoshi T, Minami A. Arthroscopic-assisted repair of avulsed triangular fibrocartilage complex to the fovea of the ulnar head: a 2- to 4-year follow-up study. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(10):1371–1378. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2011.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jegal M, Heo K, Kim J P. Arthroscopic trans-osseous suture of peripheral triangular fibrocartilage complex tear. J Hand Surg Asian Pac Vol. 2016;21(03):300–306. doi: 10.1142/S2424835516400105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim B, Yoon H K, Nho J H. Arthroscopically assisted reconstruction of triangular fibrocartilage complex foveal avulsion in the ulnar variance-positive patient. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(11):1762–1768. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2013.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Luchetti R, Atzei A, Cozzolino R, Fairplay T, Badur N. Comparison between open and arthroscopic-assisted foveal triangular fibrocartilage complex repair for post-traumatic distal radio-ulnar joint instability. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2014;39(08):845–855. doi: 10.1177/1753193413501977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moritomo H. Open repair of the triangular fibrocartilage complex from palmar aspect. J Wrist Surg. 2015;4(01):2–8. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1398474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Park J H, Kim D, Park J W. Arthroscopic one-tunnel transosseous foveal repair for triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC) peripheral tear. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2018;138(01):131–138. doi: 10.1007/s00402-017-2835-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shinohara T, Tatebe M, Okui N, Yamamoto M, Kurimoto S, Hirata H. Arthroscopically assisted repair of triangular fibrocartilage complex foveal tears. J Hand Surg Am. 2013;38(02):271–277. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jung H S, Song K S, Yoon B I, Lee J S, Park M J. Clinical outcomes and factors influencing these outcome measures resulting in success after arthroscopic transosseous triangular fibrocartilage complex foveal repair. Arthroscopy. 2019;35(08):2322–2330. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2019.03.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Garcia-Elias M, Smith D E, Llusá M. Surgical approach to the triangular fibrocartilage complex. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg. 2003;7(04):134–140. doi: 10.1097/00130911-200312000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Atzei A. New trends in arthroscopic management of Type 1-B TFCC injuries with DRUJ instability. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2009;34(05):582–591. doi: 10.1177/1753193409100120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim J P, Park M J. Assessment of distal radioulnar joint instability after distal radius fracture: comparison of computed tomography and clinical examination results. J Hand Surg Am. 2008;33(09):1486–1492. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2008.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ehman E C, Hayes M L, Berger R A, Felmlee J P, Amrami K K. Subluxation of the distal radioulnar joint as a predictor of foveal triangular fibrocartilage complex tears. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36(11):1780–1784. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2011.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.The PRISMA Group . Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman D G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLOS Med. 2009 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]