Abstract

Tissue-resident memory T cells (TRM cells) have crucial functions in host defense in mucosal tissues. They provide local adaptive immune surveillance and allow the fast initiation of targeted adaptive immune responses in case of antigen re-exposure. Recently, an aberrant activation in the case of immunologically mediated diseases has been increasingly acknowledged. As the organ with the largest interface to the environment, the gastrointestinal tract faces billions of antigens every day. Tightly balanced processes are necessary to ensure tolerance towards non-hazardous antigens, but to set up a powerful immune response against potentially dangerous ones. In this complex nexus of immune cells and their mediators, TRM cells play a central role and have been shown to promote both physiological and pathological events. In this review, we will summarize the current knowledge on the homeostatic functions of TRM cells and delineate their implication in infection control in the gut. Moreover, we will outline their commitment in immune dysregulation in gastrointestinal chronic inflammatory conditions and shed light on TRM cells as current and potential future therapeutic targets.

Keywords: tissue-resident memory T cells, intestine, inflammatory bowel diseases, infection control, therapeutic targets

Introduction

Coordinated processes of the immune system require a tightly regulated interplay of various immune cell types and mediators. A particular feature of the adaptive immune system is the generation of immunological memory following antigen exposure leading to preparedness for the initiation of targeted immune responses in case of re-exposure. To this end, memory T cells are generated during a primary confrontation with an antigen. After its clearing, they survive as long-lived patrolling guards in particular compartments of the body.

Memory T cells are grouped into three main populations: central memory T cells (TCM), effector memory T cells (TEM), and tissue-resident memory T cells (TRM) (1–4). TRM cells persist at epithelial surfaces including the gastrointestinal tract (GIT), skin, and lung as well as in non-barrier tissues such as the brain and the joints (3, 5–9). They are transcriptionally, phenotypically, and functionally distinct from recirculating central and effector memory T cells (10). Due to their localization at the interface between the host and the environment, they provide local adaptive immune surveillance for intruding cognate antigens, positioning them in the driver’s seat for the re-initiation of immune responses to known antigens in mucosal tissues (11). The GIT disposes over the largest surface of the body exposed to the external environment. This environment has a challenging composition including commensal, pathobiontic and sometimes pathogenic bacteria, viruses and, parasites as well as nutritional and potentially toxic antigens. Therefore, a closely regulated local immune system balancing tolerance and protection is essential and, as the first line of adaptive defence, TRM cells play a key role in this context. This said, it is obvious that in addition to crucial functions in infection control, dysregulation of TRM networks may also contribute to the development of diseases such as chronic inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD).

However, the role of TRM cells in the intestine is not completely understood. In the following paragraphs, we will review the current knowledge on their implication in intestinal immune processes and also outline the putative contribution to pathological conditions as well as translational approaches to target TRM cells.

Phenotype of Intestinal TRM Cells

TRM cells have first been described in 2009 (4) and, early on, a specific profile of molecules associated with a TRM phenotype was evident. More recently, Kumar and colleagues described a transcriptional and phenotypic signature that defines both CD8+ and CD4+ TRM cells in humans and that is conserved across individuals and in mucosal and lymphoid tissues (12).

In general, the membrane protein CD69 is used to define both CD8+ and CD4+ TRM cells. CD69 is a type II C-lectin receptor, which regulates, on the one hand, the differentiation of regulatory T cells and the secretion of cytokines like IL-17, IL-22, and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and suppresses, on the other hand, the sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 (S1PR1) [(13, 14), reviewed in (15)]. Mechanistically, CD69 interferes with the cell surface expression and function of S1PR1, which is essential for T and B cell egress from peripheral tissues, secondary lymphoid organs and thymus via chemotaxis towards S1P, which is present in high concentrations in the bloodstream (13, 16, 17). Moreover, a decreased expression of the transcription factor KLF2 in TRM cells leads to the downregulation of S1PR1 (18). Together, the upregulation of CD69 and the downregulation of KLF2 and S1PR1 promote tissue retention of TRM cells.

However, there is also evidence that CD69 is not expressed on all TRM cells and—depending on the tissue—is not necessary for their generation. According to these studies, CD69 plays no discernible role for TRM cell formation in the small intestine, while it is essential for TRM cell development in the kidney in mice (19, 20).

Another important marker of TRM cells is CD103, also called αE integrin. CD103 pairs with the β7 integrin chain and the heterodimer binds to E-cadherin, which is expressed on epithelial cells (21). Thus, this interaction constitutes an independent mechanism promoting mucosal retention. It was already shown in humans and in mice that the expression of CD103 is more predominant in CD8+ TRM cells than in CD4+ TRM cells (22–24). Moreover, in the human intestine, CD103 is not necessary for the persistence of CD4+ and CD8+ TRM cells (6, 7, 22). Bergsbaken and colleagues even identified a preferential development of CD103- TRM cells in inflammatory microenvironments within the mouse lamina propria upon infection with Yersinia pseudotuberculosis (Yptb) (22).

Further core phenotypic markers for human CD8+ TRM cells in multiple mucosal and lymphoid tissues include CD49a, CD101, and PD-1 (12), whereas CD161, a C-type lectin-like receptor seems to be specific for CD8+ TRM cells in the human gut (25, 26). Furthermore, the TRM-specific gene signature includes the downregulation of lymph node homing molecules such as CD62L and CCR7, the upregulation of specific adhesion molecules like CRTAM, as well as the modulation of specific chemokine receptors including an increased CXCR6 and decreased CX3CR1 expression (12).

Several transcription factors have been implicated in the transcriptional control of TRM cells leading to the expression of the above-mentioned molecules. In particular, Hobit together with Blimp-1 (PRDM1), Runx3, and Notch regulate the differentiation and maintenance of TRM cells. Importantly, Hobit and Blimp-1 are known to synergistically control the expression of TRM cell-regulated genes like CD69, KLF2, and S1PR1 (27–29). In this context, it is important to mention that Hobit expression is restricted to tissue-resident T cells [including TRM cells, NKT cells, and some MAIT cells] in mice (27, 30), but not in humans. There, Hobit expression is also found in other T cell subsets with cytotoxic phenotype (31, 32).

Importantly, several cytokines like IL-15, IL-33, transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) were identified to play a role in the maintenance of TRM cells (18, 33).

TRM Cells in Intestinal Infection Control

Especially in the GIT, TRM cells are important in mediating fast and effective immune responses, when necessary. Thus, they crucially contribute to the maintenance of the local tissue homeostasis.

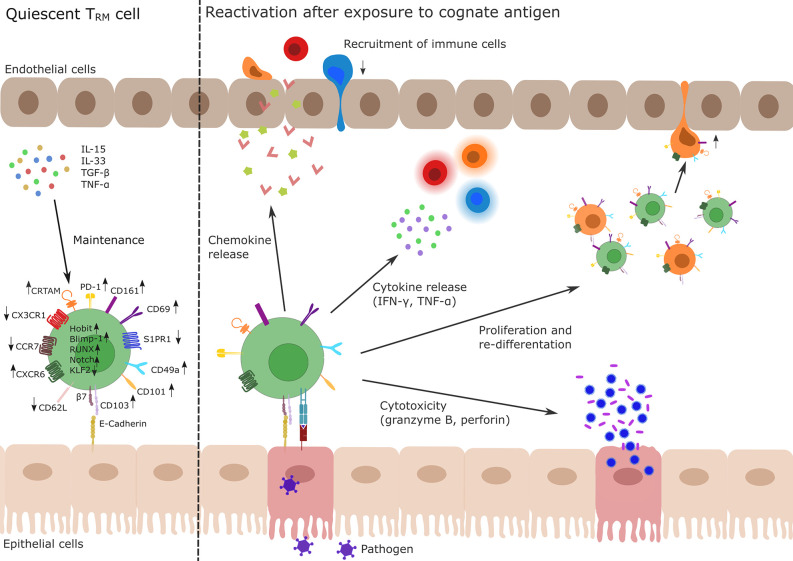

During primary infection, whether viral, bacterial or parasitic, some memory T cells acquire a TRM phenotype including differential protein expression as described above and are retained in the tissue, where they are able to survive long-term (4, 34, 35). There seems to be considerable heterogeneity in intestinal TRM populations as recently suggested by two studies building on single-cell transcriptomics in mice (36, 37). After re-infection with a previously encountered pathogen, the presence of TRM cells provides a short-cut with regard to the time-consuming processes involved in de-novo adaptive immune responses, i.e. antigen processing by antigen-presenting cells (APCs), APC migration to secondary lymphoid tissues, T cell recognition, co-stimulation with subsequent activation, and proliferation as well as recirculation and migration of effector T cells to the infected tissue [reviewed in (38–41)]. Instead, upon antigen binding, TRM cells are directly able to proliferate, to secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IFN-γ or TNF-α and chemokines and to mediate cytotoxicity by secreting granzyme B and perforin to directly eliminate infected cells ( Figure 1 ) [(5–7, 42), reviewed in (43)].

Figure 1.

Profile and function of TRM cells. Left side: TRM cells develop during primary infection. The differentiation and maintenance of TRM cells is controlled by tissue-derived signals, e.g., TNF-α, TGF-β or IL-15 and IL-33 resulting in the up- and down-regulation of different genes via activity of the transcription factors Hobit, Blimp-1, Runx3, and Notch and the silencing of Klf2. In particular, upregulation of CD69 and CD103 and simultaneous downregulation of S1PR1 are key drivers of TRM cell tissue retention. Other membrane molecules highly expressed in TRM cells are CD49a, CD101, PD-1, CRTAM, and CXCR6 while CD62L, CCR7, and CX3CR1 show a decreased expression pattern in TRM cells. Right side: After re-exposure to a cognate antigen (e.g., from a pathogen, shown in purple), TRM cells are able to initiate a fast immune response. This includes chemokine release to recruit lymphocytes (indicated as red, orange, and blue immune cells) to the site of infection, release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IFN-γ, TNF-α) to activate other cells as well as the production of the cytotoxic effectors perforin or granzyme B. There is also evidence for the ability of TRM cells to proliferate or to re-differentiate (indicated as green and orange cells) and to leave the tissue (orange ex-TRM cells; for details cf. main text). TRM, tissue-resident memory T cell; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; TGF, transforming growth factor; IL, Interleukin; KLF, Krüppel-like factor; CD, cluster of differentiation; S1PR1, sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1; PD-1, programmed cell death protein 1; CRTAM, cytotoxic and regulatory T-cell molecule; CXCR, CXC-motif chemokine receptor; CCR, Chemokine receptor.

Interestingly, TRM cells are not only generated at the site of primary infection but also seed distant locations. However, as shown by Sheridan and colleagues in mice, intestinal CD8+ TRM cells developing upon oral infection with Listeria monocytogenes are more robust and have another phenotype than intestinal TRM cells developing upon intranasal or intravenous infection (44).

Due to the increased abundance of CD8+ TRM cells compared with CD4+ TRM cells, the former have been examined in much more detail in the context of intestinal infections. Yet, CD4+ and CD8+ TRM cells share several similarities and CD4+ TRM cells crucially contribute to recall immunity by chemokine secretion and immune cell activation (45).

In summary, these observations suggest that TRM cells might be important effectors of vaccination strategies in the gut. Consistently, a recent study showed that an oral typhoid vaccine was able to induce antigen-specific CD4+ TRM cells in the human small intestine (46). Additionally, transient microbiota depletion-boosted immunization in mice has been proposed as a strategy to optimize TRM cell generation upon exposure with vaccine antigens (47).

Studies by Bartolomé-Casado et al. revealed that both CD4+ and CD8+ TRM cells persist for years in the human small intestine. Both undergo tissue-specific changes, which make them polyfunctional TH1 and TC1 cells (6, 7). How this longevity of TRM cells is ensured is not completely elucidated so far and the question arises whether the size of the TRM population in a homeostatic state is regulated by a continuous supply of recirculating memory T cells or whether a well-balanced TRM cell proliferation is sufficient for the maintenance of the TRM cell population [reviewed in (43)]. However, low-level homeostatic cell proliferation has been described for TRM cells, e.g. in the skin and female reproductive tract, but not for the GIT so far (5, 48).

In contrast to the view that TRM cells are confined within “their” tissue, Fonseca and colleagues showed that there is also evidence for fully differentiated TRM cells in mice, which re-differentiate and recirculate into lymphoid tissues (49). Moreover, it was shown that CD4+ TRM cells in the skin may have the ability to downregulate CD69 and subsequently exit the tissue (50). Very recently, this has been demonstrated for intestinal CD8+ TRM cells following oral Listeria monocytogenes re-infection. Using a Hobit reporter mouse strain, Behr and co-workers could elegantly show that ex-TRM cells appeared in the circulation and were able to mount systemic and local immune responses (51).

Taken together, these data show that TRM cells represent an important switch point in recall immunity. However, the presence of this cell type, which is able to mediate powerful immune responses also entails the risk that dysregulation and imbalance can lead to immune dysfunctions like allergic disorders or chronic inflammation.

TRM Cells in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases

In recent years, the implication of TRM cells in pathological conditions has been increasingly acknowledged. In particular, they seem to play an important role in various cancer entities and several immune-mediated inflammatory disorders like psoriasis, vitiligo, psoriatic arthritis, and IBD (52–58). Whereas TRM cells as tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) are associated with a better prognosis in most cancer types (e.g. ovarian cancer, breast cancer, and gastric adenocarcinoma), CD103+ TIL in colorectal cancer are associated with poor prognosis (56–59), suggesting that their impact is tissue-specific.

In the context of IBDs, an important role of TRM cells has only recently emerged. Several studies indicate that the presence and generation of TRM cells are involved in the pathogenesis of IBDs ( Table 1 ). We were able to show that CD69+CD103+ cells with a TRM phenotype are increased in the lamina propria of patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD) and that high levels of CD4+ TRM cells in IBD patients are associated with early relapse. In mice, we observed that the key TRM transcription factors Hobit and Blimp-1 are essential for experimental colitis since their absence protected from T cell transfer colitis, dextran sodium sulphate-induced colitis and trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid-induced colitis. Mechanistically, we could attribute this to an adaptive-innate crosstalk mechanism including chemokine release by TRM cells and subsequent recruitment and differentiation of pro-inflammatory immune cells (55). Consistent with these results Bishu and colleagues reported, that CD4+ TRM cells are increased in CD compared with control patients and identified these CD4+ TRM cells as the major T cell source of TNF-α in the mucosa of CD patients. Furthermore, these cells produced more IL-17A and TNF-α in inflamed compared to healthy tissue (60). Bottois and colleagues profiled two distinct CD8+ TRM cell subsets in CD, defined by KLRG1 and CD103, which are both receptors of E-Cadherin. CD103+CD8+ TRM cells in CD patients expressed TH17-related genes such as CCL20, IL-22 and, IL-26 suggesting that they may trigger innate immune responses as well as the recruitment of effector cells. KLRG1+CD8+ TRM cells were specifically elevated under inflammatory conditions and showed increased proliferative and cytotoxic potential (61). Furthermore, a recent study employing single-cell RNA-sequencing identified changes in the transcriptional profile of CD8+ TRM cell subsets in UC including a pro-inflammatory phenotype and increased expression of Eomesodermin (62). Similarly, Corridoni and colleagues reported that CD8+ TRM cells in UC express more GZMK and IL26, suggesting that altered CD8+ TRM cells are implicated in UC pathogenesis (63).

Table 1.

Overview of studies on the role of TRM cells in IBD.

| Organsim | Key conclusions on TRM cells | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Human and Mouse | Human: → CD69+CD103+ cells with a TRM phenotype are increased in the lamina propria of patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD) → High levels of CD4+ TRM cells in IBD patients are associated with early relapse. Mouse: → TRM cells expressing Hobit and Blimp-1 are key drivers of experimental colitis due to an adaptive-innate crosstalk mechanism |

(55) |

| Human | → Increased CD4+ TRM cell population in CD compared with control patients → Increased production of IL-17A and TNF-α by TRM cells in inflamed compared to healthy tissue → Major T cell source of TNF-α in the mucosa of CD patients. |

(60) |

| Human | → Two distinct CD8+ TRM cell subsets in CD, defined by KLRG1 and CD103 → CD103+CD8+ TRM cells: express TH17-related genes such as CCL20, IL-22, and IL-26 → KLRG1+CD8+ TRM cells: specifically elevated under inflammatory conditions, show increased proliferative and cytotoxic potential |

(61) |

| Human | → Changes in the transcriptional profile of CD8+ TRM cell subsets in UC: pro-inflammatory phenotype and increased expression of Eomesodermin | (62) |

| Human | → CD8+ TRM cells in UC express more GZMK and IL26 → Altered CD8+ TRM cells may be implicated in UC pathogenesis |

(63) |

| Human | → Reduced numbers of CD103+Runx3+ TRM cells with a probably regulatory phenotype in CD and UC: expression of CD39 and CD73, release of IL-10 | (64) |

| Human | → Decreased numbers of CD103+CD4+ and CD103+CD8+ T cells in active IBD → Rise of the numbers of these cells in the remission phase up to levels comparable with healthy controls. |

(65) |

Yet, observations made by other groups support the notion that the picture is more complex. E.g., Noble et al. described reduced numbers of CD103+Runx3+ TRM cells in CD and UC. They observed the expression of CD39 and CD73 on these cells as well as the release of IL-10 suggesting that these cells have a regulatory phenotype. They hypothesized that TRM cells probably serve as gatekeepers by controlling the access of mucosal antigens to germinal centers in lymphoid tissue (64). Roosenboom and colleagues reported decreased numbers of CD103+CD4+ and CD103+CD8+ T cells in active IBD and found a rise of these numbers in the remission phase up to levels comparable with healthy controls. In addition, they observed a lower number of CD103- T cells in healthy controls and IBD patients in remission in comparison with active CD and UC patients (65). Importantly, this study was not specifically designed to assess TRM cells. Thus, it seems possible that these data are actually indicative of a change in TRM cell phenotype similar to some of the studies mentioned above.

Taken together, TRM cells are undoubtedly involved in the pathogenesis of IBDs. However, different observations have been made with regard to their function and mechanisms. While these seem to be conflicting on first view, it is likely that they rather derive from different approaches to a complex issue. For example, considering that TRM cell generation may occur following any recognition of a cognate antigen by a naïve T cell, it is also clear that—depending on co-stimulatory signals and the nature of the surrounding environment—different forms of T cell memory may be imprinted. Thus, it is not surprising that regulatory as well as pro-inflammatory TRM phenotypes have been described depending on the markers chosen to identify the cells. In consequence, the reduction of regulatory-type TRM cells is actually not at all contradicting other observations, such as perturbed TRM cell phenotypes in IBD or increased pro-inflammatory TRM cell populations. Yet, further investigations are necessary to answer the remaining open questions.

TRM Cells as Potential Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases

Based on the above-mentioned reports TRM cells seem to be a promising therapeutic target to treat UC and CD.

Specific approaches in that regard are still lacking and would require the identification of unique targets on or in TRM cells as well as the selection of appropriate targeting strategies. However, the mechanism of the monoclonal anti-β7 integrin antibody etrolizumab, which blocks the αEβ7 and α4β7 integrin heterodimers might in part be explained by effects on TRM cells. For example, this antibody has been shown to block the retention of CD8+ T cells from patients with UC in a humanized in vivo cell trafficking model suggesting that it might also reduce the retention of TRM cells in the gut (66). Moreover, post-hoc analyses of the successful phase II trial in UC showed that patients with high expression of CD103 were more likely to respond to etrolizumab therapy (67, 68). Etrolizumab recently completed an ambitious phase III trial program in UC, in which only two out of three induction trials and no maintenance trial reached the primary endpoint. However, the drug was efficient in several important secondary endpoints and was similarly effective as infliximab and adalimumab, underscoring its biological activity and warranting further research (69–72). Phase III trials in CD are still ongoing with promising results in an exploratory cohort (73, 74).

As mentioned above, the downregulation of S1PR1 is a hallmark of TRM cells. In this context, it is tempting to speculate, which effect the class of S1PR modulators including ozanimod, etrasimod, and amiselimod, which are currently also investigated for application in IBDs might have on intestinal T cells (75, 76). While it is evident that they lead to sequestration of naïve T cells and TCM cells in secondary lymphoid organs (77), one could also assume that they reduce recirculation of T cells from the tissue driving the retention of local non-TRM T cells.

Some of the drugs already in use in IBD might also partly affect TRM cells in the gut. For instance, the anti-α4β7 integrin antibody vedolizumab that blocks T cell homing to the gut via MAdCAM-1 might reduce the recruitment of pre-TRM cells and, thus, prevent the seeding of new TRM cells [reviewed in (78)]. The anti-IL-12/23 antibody ustekinumab is thought to block the generation and differentiation of TH1 and TH17 cells [reviewed in (79)]. This will certainly also affect TRM cells with a TH1 or TH17 phenotype, e.g. the de-novo generation of such cells might be reduced or established TRM cells might be subjected to plasticity due to an altered cytokine balance (80, 81). Another drug routinely used in UC is tofacitinib, which inhibits the Janus kinase (JAK) pathway (mainly JAK1 and JAK3) and, thus, abrogates signaling of numerous cytokines (82, 83). This also affects IL-15, which is known to participate in the maintenance of TRM cells (18, 33, 84). In the skin, it has already been shown that targeting CD122, a subunit of the IL-15 receptor, is a potential treatment strategy for tissue-specific autoimmune diseases involving TRM cell such as vitiligo (85).

Collectively, research on TRM cells as a therapeutic target is still in its infancy. However, several currently used and developed drugs, particularly etrolizumab and S1PR1 modulators, might interfere with TRM cells and it is likely that the coming years will reveal further details on their suitability for treating IBD.

Concluding Remarks

Over the last decade, TRM cells have emerged as an important cell population in mucosal tissues controlling the initiation of secondary immune responses. Multiple efforts have led to a precise characterization of their phenotype and implication in infection control. Moreover, they have been increasingly associated with pathological conditions, in the case of the GIT, particularly with IBD. Although not all questions are already resolved, TRM cells seem to control important steps in the pathogenesis of chronic intestinal inflammation and, thus, represent a potential target for future IBD therapy. Further research is necessary to better define their pathogenetic contributions and to develop targeted therapeutic approaches.

Author Contributions

E-MP, TM, KS, MN, and SZ wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

German Research Foundation (DFG, ZU 377/4-1), Interdisciplinary Center for Clinical Research, University Hospital Erlangen (A84). We acknowledge support by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg (FAU) within the funding program Open Access Publishing.

Conflict of Interest

SZ and MN received research support from Takeda, Roche, and Shire. MN has served as an advisor for Pentax, Giuliani, MSD, Abbvie, Janssen, Takeda, and Boehringer.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The research of MN and SZ was supported by the Interdisciplinary Center for Clinical Research (IZKF) and the ELAN program of the University Erlangen-Nuremberg, the Else Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung, the Fritz Bender-Stiftung, the Dr. Robert Pfleger Stiftung, the Litwin IBD Pioneers Initiative of the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America (CCFA), the Kenneth Rainin Foundation, the Ernst Jung-Stiftung for Science and Research, the German Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation (DCCV) and the German Research Foundation (DFG) through individual grants and the Collaborative Research Centers TRR241, 643, 796, and 1181.

References

- 1. Sallusto F, Lenig D, Förster R, Lipp M, Lanzavecchia A. Two subsets of memory T lymphocytes with distinct homing potentials and effector functions. Nature (1999) 402(6763):34–8. 10.1038/35005534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Masopust D, Choo D, Vezys V, Wherry EJ, Duraiswamy J, Akondy R, et al. Dynamic T cell migration program provides resident memory within intestinal epithelium. J Exp Med (2010) 207(3):553–64. 10.1084/jem.20090858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hogan RJ, Usherwood EJ, Zhong W, Roberts AA, Dutton RW, Harmsen AG, et al. Activated antigen-specific CD8+ T cells persist in the lungs following recovery from respiratory virus infections. J Immunol (2001) 166(3):1813–22. 10.4049/jimmunol.166.3.1813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gebhardt T, Wakim LM, Eidsmo L, Reading PC, Heath WR, Carbone FR. Memory T cells in nonlymphoid tissue that provide enhanced local immunity during infection with herpes simplex virus. Nat Immunol (2009) 10(5):524–30. 10.1038/ni.1718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Park SL, Zaid A, Hor JL, Christo SN, Prier JE, Davies B, et al. Local proliferation maintains a stable pool of tissue-resident memory T cells after antiviral recall responses. Nat Immunol (2018) 19(2):183–91. 10.1038/s41590-017-0027-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bartolomé-Casado R, Landsverk OJB, Chauhan SK, Richter L, Phung D, Greiff V, et al. Resident memory CD8 T cells persist for years in human small intestine. J Exp Med (2019) 216(10):2412–26. 10.1084/jem.20190414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bartolomé-Casado R, Landsverk OJB, Chauhan SK, Sætre F, Hagen KT, Yaqub S, et al. CD4(+) T cells persist for years in the human small intestine and display a T(H)1 cytokine profile. Mucosal Immunol (2020). 10.1038/s41385-020-0315-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wakim LM, Woodward-Davis A, Liu R, Hu Y, Villadangos J, Smyth G, et al. The molecular signature of tissue resident memory CD8 T cells isolated from the brain. J Immunol (2012) 189(7):3462–71. 10.4049/jimmunol.1201305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chang MH LA, Morris A, Nelson-Maney N, Fuhlbrigge R, Nigrovic PA. Murine Model of Arthritis Flare Identifies CD8+ Tissue Resident Memory T Cells in Recurrent Synovitis. Arthritis Rheumatol (2017) 69(suppl 4). Accessed October 6, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Watanabe R, Gehad A, Yang C, Scott LL, Teague JE, Schlapbach C, et al. Human skin is protected by four functionally and phenotypically discrete populations of resident and recirculating memory T cells. Sci Trans Med (2015) 7(279):279ra39–279ra39. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3010302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Raphael I, Joern RR, Forsthuber TG. Memory CD4+ T Cells in Immunity and Autoimmune Diseases. Cells (2020) 9(3):531. 10.3390/cells9030531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kumar BV, Ma W, Miron M, Granot T, Guyer RS, Carpenter DJ, et al. Human Tissue-Resident Memory T Cells Are Defined by Core Transcriptional and Functional Signatures in Lymphoid and Mucosal Sites. Cell Rep (2017) 20(12):2921–34. 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.08.078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mackay LK, Braun A, Macleod BL, Collins N, Tebartz C, Bedoui S, et al. Cutting Edge: CD69 Interference with Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Receptor Function Regulates Peripheral T Cell Retention. J Immunol (2015) 194: (5):2059–63. 10.4049/jimmunol.1402256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bankovich AJ, Shiow LR, Cyster JG. CD69 suppresses sphingosine 1-phosophate receptor-1 (S1P1) function through interaction with membrane helix 4. J Biol Chem (2010) 285(29):22328–37. 10.1074/jbc.M110.123299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cibrián D, Sánchez-Madrid F. CD69: from activation marker to metabolic gatekeeper. Eur J Immunol (2017) 47(6):946–53. 10.1002/eji.201646837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Matloubian M, Lo CG, Cinamon G, Lesneski MJ, Xu Y, Brinkmann V, et al. Lymphocyte egress from thymus and peripheral lymphoid organs is dependent on S1P receptor 1. Nature (2004) 427(6972):355–60. 10.1038/nature02284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mandala S, Hajdu R, Bergstrom J, Quackenbush E, Xie J, Milligan J, et al. Alteration of lymphocyte trafficking by sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor agonists. Science (2002) 296(5566):346–9. 10.1126/science.1070238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Skon CN, Lee JY, Anderson KG, Masopust D, Hogquist KA, Jameson SC. Transcriptional downregulation of S1pr1 is required for the establishment of resident memory CD8+ T cells. Nat Immunol (2013) 14(12):1285–93. 10.1038/ni.2745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Steinert EM, Schenkel JM, Fraser KA, Beura LK, Manlove LS, Igyártó BZ, et al. Quantifying Memory CD8 T Cells Reveals Regionalization of Immunosurveillance. Cell (2015) 161(4):737–49. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Walsh DA, Borges da Silva H, Beura LK, Peng C, Hamilton SE, Masopust D, et al. The Functional Requirement for CD69 in Establishment of Resident Memory CD8(+) T Cells Varies with Tissue Location. J Immunol (2019) 203(4):946–55. 10.4049/jimmunol.1900052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cepek KL, Shaw SK, Parker CM, Russell GJ, Morrow JS, Rimm DL, et al. Adhesion between epithelial cells and T lymphocytes mediated by E-cadherin and the αEβ7 integrin. Nature (1994) 372(6502):190–3. 10.1038/372190a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bergsbaken T, Bevan MJ. Proinflammatory microenvironments within the intestine regulate the differentiation of tissue-resident CD8⁺ T cells responding to infection. Nat Immunol (2015) 16(4):406–14. 10.1038/ni.3108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Thom JT, Weber TC, Walton SM, Torti N, Oxenius A. The Salivary Gland Acts as a Sink for Tissue-Resident Memory CD8+ T Cells, Facilitating Protection from Local Cytomegalovirus Infection. Cell Rep (2015) 13(6):1125–36. 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.09.082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Turner DL, Bickham KL, Thome JJ, Kim CY, D'Ovidio F, Wherry EJ, et al. Lung niches for the generation and maintenance of tissue-resident memory T cells. Mucosal Immunol (2014) 7(3):501–10. 10.1038/mi.2013.67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kurioka A, Cosgrove C, Simoni Y, van Wilgenburg B, Geremia A, Björkander S, et al. CD161 Defines a Functionally Distinct Subset of Pro-Inflammatory Natural Killer Cells. Front Immunol (2018) 9:486–6. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fergusson JR, Hühn MH, Swadling L, Walker LJ, Kurioka A, Llibre A, et al. CD161(int)CD8+ T cells: a novel population of highly functional, memory CD8+ T cells enriched within the gut. Mucosal Immunol (2016) 9(2):401–13. 10.1038/mi.2015.69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mackay LK, Minnich M, Kragten NA, Liao Y, Nota B, Seillet C, et al. Hobit and Blimp1 instruct a universal transcriptional program of tissue residency in lymphocytes. Science (2016) 352(6284):459–63. 10.1126/science.aad2035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Milner JJ, Toma C, Yu B, Zhang K, Omilusik K, Phan AT, et al. Runx3 programs CD8(+) T cell residency in non-lymphoid tissues and tumours. Nature (2017) 552(7684):253–7. 10.1038/nature24993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hombrink P, Helbig C, Backer RA, Piet B, Oja AE, Stark R, et al. Programs for the persistence, vigilance and control of human CD8+ lung-resident memory T cells. Nat Immunol (2016) 17(12):1467–78. 10.1038/ni.3589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Salou M, Legoux F, Gilet J, Darbois A, du Halgouet A, Alonso R, et al. A common transcriptomic program acquired in the thymus defines tissue residency of MAIT and NKT subsets. J Exp Med (2018) 216(1):133–51. 10.1084/jem.20181483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Oja AE, Vieira Braga FA, Remmerswaal EB, Kragten NA, Hertoghs KM, Zuo J, et al. The Transcription Factor Hobit Identifies Human Cytotoxic CD4+ T Cells. Front Immunol (2017) 8:325. 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Vieira Braga FA, Hertoghs KM, Kragten NA, Doody GM, Barnes NA, Remmerswaal EB, et al. Blimp-1 homolog Hobit identifies effector-type lymphocytes in humans. Eur J Immunol (2015) 45(10):2945–58. 10.1002/eji.201545650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mackay LK, Rahimpour A, Ma JZ, Collins N, Stock AT, Hafon ML, et al. The developmental pathway for CD103+CD8+ tissue-resident memory T cells of skin. Nat Immunol (2013) 14(12):1294–301. 10.1038/ni.2744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Romagnoli PA, Sheridan BS, Pham QM, Lefrançois L, Khanna KM. IL-17A–producing resident memory γδ T cells orchestrate the innate immune response to secondary oral Listeria monocytogenes infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci (2016) 113(30):8502–7. 10.1073/pnas.1600713113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Steinfelder S, Rausch S, Michael D, Kühl AA, Hartmann S. Intestinal helminth infection induces highly functional resident memory CD4(+) T cells in mice. Eur J Immunol (2017) 47(2):353–63. 10.1002/eji.201646575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Milner JJ, Toma C, He Z, Kurd NS, Nguyen QP, McDonald B, et al. Heterogenous Populations of Tissue-Resident CD8+ T Cells Are Generated in Response to Infection and Malignancy. Immunity (2020) 52(5):808–824.e7. 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kurd NS, He Z, Louis TL, Milner JJ, Omilusik KD, Jin W, et al. Early precursors and molecular determinants of tissue-resident memory CD8+ T lymphocytes revealed by single-cell RNA sequencing. Sci Immunol (2020) 5(47):eaaz6894. 10.1126/sciimmunol.aaz6894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Masopust D, Picker LJ. Hidden Memories: Frontline Memory T Cells and Early Pathogen Interception. J Immunol (2012) 188(12):5811–7. 10.4049/jimmunol.1102695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gebhardt T, Mackay L. Local immunity by tissue-resident CD8+ memory T cells. Front Immunol (2012) 3:340. 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Park CO, Kupper TS. The emerging role of resident memory T cells in protective immunity and inflammatory disease. Nat Med (2015) 21(7):688–97. 10.1038/nm.3883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zundler S, Neurath MF. Pathogenic T cell subsets in allergic and chronic inflammatory bowel disorders. Immunol Rev (2017) 278(1):263–76. 10.1111/imr.12544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Schenkel JM, Fraser KA, Vezys V, Masopust D. Sensing and alarm function of resident memory CD8⁺ T cells. Nat Immunol (2013) 14(5):509–13. 10.1038/ni.2568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mueller SN, Mackay LK. Tissue-resident memory T cells: local specialists in immune defence. Nat Rev Immunol (2016) 16(2):79–89. 10.1038/nri.2015.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sheridan BS, Pham QM, Lee YT, Cauley LS, Puddington L, Lefrançois L, et al. Oral infection drives a distinct population of intestinal resident memory CD8(+) T cells with enhanced protective function. Immunity (2014) 40(5):747–57. 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Beura LK, Fares-Frederickson NJ, Steinert EM, Scott MC, Thompson EA, Fraser KA, et al. CD4+ resident memory T cells dominate immunosurveillance and orchestrate local recall responses. J Exp Med (2019) 216(5):1214–29. 10.1084/jem.20181365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Booth JS, Goldberg E, Barnes RS, Greenwald BD, Sztein MB, et al. Oral typhoid vaccine Ty21a elicits antigen-specific resident memory CD4+ T cells in the human terminal ileum lamina propria and epithelial compartments. J Transl Med (2020) 18(1):102. 10.1186/s12967-020-02263-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Becattini S, Littmann ER, Seok R, Amoretti L, Fontana E, Wright R, et al. Enhancing mucosal immunity by transient microbiota depletion. Nat Commun (2020) 11(1):4475. 10.1038/s41467-020-18248-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Beura LK, Mitchell JS, Thompson EA, Schenkel JM, Mohammed J, Wijeyesinghe S, et al. Intravital mucosal imaging of CD8+ resident memory T cells shows tissue-autonomous recall responses that amplify secondary memory. Nat Immunol (2018) 19(2):173–82. 10.1038/s41590-017-0029-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Fonseca R, Beura LK, Quarnstrom CF, Ghoneim HE, Fan Y, Zebley CC, et al. Developmental plasticity allows outside-in immune responses by resident memory T cells. Nat Immunol (2020) 21(4):412–21. 10.1038/s41590-020-0607-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Klicznik MM, Morawski PA, Höllbacher B, Varkhande SR, Motley SJ, Kuri-Cervantes L, et al. Human CD4+CD103+ cutaneous resident memory T cells are found in the circulation of healthy individuals. Sci Immunol (2019) 4(37):eaav8995. 10.1126/sciimmunol.aav8995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Behr FM, Parga-Vidal L, Kragten NAM, van Dam TJP, Wesselink TH, Sheridan BS, et al. Tissue-resident memory CD8+ T cells shape local and systemic secondary T cell responses. Nat Immunol (2020) 21(9):1070–81. 10.1038/s41590-020-0723-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Boyman O, Hefti HP, Conrad C, Nickoloff BJ, Suter M, Nestle FO, et al. Spontaneous development of psoriasis in a new animal model shows an essential role for resident T cells and tumor necrosis factor-alpha. J Exp Med (2004) 199(5):731–6. 10.1084/jem.20031482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Cheuk S, Schlums H, Gallais Sérézal I, Martini E, Chiang SC, Marquardt N, et al. CD49a Expression Defines Tissue-Resident CD8+ T Cells Poised for Cytotoxic Function in Human Skin. Immunity (2017) 46(2):287–300. 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.01.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Boniface K, Jacquemin C, Darrigade AS, Dessarthe B, Martins C, Boukhedouni N, et al. Vitiligo Skin Is Imprinted with Resident Memory CD8 T Cells Expressing CXCR3. J Invest Dermatol (2018) 138(2):355–64. 10.1016/j.jid.2017.08.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zundler S, Becker E, Spocinska M, Slawik M, Parga-Vidal L, Stark R, et al. Hobit- and Blimp-1-driven CD4+ tissue-resident memory T cells control chronic intestinal inflammation. Nat Immunol (2019) 20(3):288–300. 10.1038/s41590-018-0298-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lin R, Zhang H, Yuan Y, He Q, Zhou J, Li S, et al. Fatty Acid Oxidation Controls CD8+ Tissue-Resident Memory T-cell Survival in Gastric Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Immunol Res (2020) 8: (4):479–92. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-19-0702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Webb JR, Milne K, Watson P, Deleeuw RJ, Nelson BH, et al. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes expressing the tissue resident memory marker CD103 are associated with increased survival in high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res (2014) 20(2):434–44. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wang ZQ, Milne K, Derocher H, Webb JR, Nelson BH, Watson PH. CD103 and Intratumoral Immune Response in Breast Cancer. Clin Cancer Res (2016) 22(24):6290–7. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Huang A, Huang P, Luo Y, Wang B, Luo X, Zheng Z, et al. CD 103 expression in normal epithelium is associated with poor prognosis of colorectal cancer patients within defined subgroups. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Pathology (2017) 10(6):6624–6634. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Bishu S, El Zaatari M, Hayashi A, Hou G, Bowers N, Kinnucan J, et al. CD4+ Tissue-resident Memory T Cells Expand and Are a Major Source of Mucosal Tumour Necrosis Factor α in Active Crohn’s Disease. J Crohn’s Colitis (2019) 13(7):905–15. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Bottois H, Ngollo M, Hammoudi N, Courau T, Bonnereau J, Chardiny V, et al. KLRG1 and CD103 Expressions Define Distinct Intestinal Tissue-Resident Memory CD8 T Cell Subsets Modulated in Crohn’s Disease. Front Immunol (2020) 11:896–6. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Boland BS, He Z, Tsai MS, Olvera JG, Omilusik KD, Duong HG, et al. Heterogeneity and clonal relationships of adaptive immune cells in ulcerative colitis revealed by single-cell analyses. Sci Immunol (2020) 5(50):eabb4432. 10.1126/sciimmunol.abb4432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Corridoni D, Antanaviciute A, Gupta T, Fawkner-Corbett D, Aulicino A, Jagielowicz M, et al. Single-cell atlas of colonic CD8+ T cells in ulcerative colitis. Nat Med (2020) 26(9):1480–90. 10.1038/s41591-020-1003-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Noble A, Durant L, Hoyles L, Mccartney AL, Man R, Segal J, et al. Deficient Resident Memory T Cell and CD8 T Cell Response to Commensals in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Crohn’s Colitis (2020) 14(4):525–37. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Roosenboom B, Wahab PJ, Smids C, Groenen MJM, van Koolwijk E, van Lochem EG, et al. Intestinal CD103+CD4+ and CD103+CD8+ T-Cell Subsets in the Gut of Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients at Diagnosis and During Follow-up. Inflamm bowel Dis (2019) 25(9):1497–509. 10.1093/ibd/izz049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Zundler S, Schillinger D, Fischer A, Atreya R, López-Posadas R, Watson A, et al. Blockade of αEβ7 integrin suppresses accumulation of CD8+ and Th9 lymphocytes from patients with IBD in the inflamed gut in vivo. Gut (2017) 66(11):1936–48. 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Vermeire S, O'Byrne S, Keir M, Williams M, Lu TT, Mansfield JC, et al. Etrolizumab as induction therapy for ulcerative colitis: a randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet (2014) 384(9940):309–18. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60661-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Tew GW, Hackney JA, Gibbons D, Lamb CA, Luca D, Egen JG, et al. Association Between Response to Etrolizumab and Expression of Integrin αE and Granzyme A in Colon Biopsies of Patients With Ulcerative Colitis. Gastroenterology (2016) 150(2):477–87.e9. 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.10.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Sandborn WJ, Vermeire S, Tyrrell H, Hassanali A, Lacey S, Tole S, et al. Etrolizumab versus placebo in tumor necrosis factor antagonist naive patients with ulcerative colitis: results from the randomized phase 3 laurel trial. (2020). Abstract, ueg week, virtual. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Dotan I, Panés J, Duvall A, Bouhnik Y, Radford-Smith G, Higgins PDR, et al. Etrolizumab compared with adalimumab or placebo as induction therapy for ulcerative colitis: results from the randomized, phase 3 hibiscus I & II trials. (2020). Abstract, ueg week, virtual. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Peyrin-Biroulet L, Hart AL, Bossuyt P, Long M, Allez M, Juillerat P, et al. Etrolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy in patients with ulcerative colitis previously exposed to anti-tumor necrosis factor agent: the randomized, phase 3 hickory trial. (2020). Abstract, ueg week, virtual. [Google Scholar]

- 72. Danese S, Colombel JF, Lukas M, Gisbert JP, D'Haens G, Hayee B, et al. Etrolizumab versus infliximab for treating patients with moderately to severly active ulcerative colitis: results from the phase 3 gardenia study. (2020). Abstract, ueg week, virtual. [Google Scholar]

- 73. Sandborn WJ, Vermeire S, Tyrrell H, Hassanali A, Lacey S, Tole S, et al. Etrolizumab for the Treatment of Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn’s Disease: An Overview of the Phase 3 Clinical Program. Adv Ther (2020) 37(7):3417–31. 10.1007/s12325-020-01366-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Sandborn WJ, Panés J, Jones J, Hassanali A, Jacob R, Sharafali Z, et al. Etrolizumab as induction therapy in moderate to serve crohn’s disease: results from bergamot cohort 1. United European Gastroenterol J (2017) 5:Supplement 10. [Google Scholar]

- 75. Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Wolf DC, D'Haens G, Vermeire S, Hanauer SB, et al. Ozanimod Induction and Maintenance Treatment for Ulcerative Colitis. N Engl J Med (2016) 374(18):1754–62. 10.1056/NEJMoa1513248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Sugahara K, Maeda Y, Shimano K, Mogami A, Kataoka H, Ogawa K, et al. Amiselimod, a novel sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor-1 modulator, has potent therapeutic efficacy for autoimmune diseases, with low bradycardia risk. Br J Pharmacol (2017) 174(1):15–27. 10.1111/bph.13641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Mehling M, Brinkmann V, Antel J, Bar-Or A, Goebels N, Vedrine C, et al. FTY720 therapy exerts differential effects on T cell subsets in multiple sclerosis. Neurology (2008) 71(16):1261–7. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000327609.57688.ea [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Zundler S, Becker E, Schulze LL, Neurath MF. Immune cell trafficking and retention in inflammatory bowel disease: mechanistic insights and therapeutic advances. Gut (2019) 68(9):1688–700. 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-317977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Benson JM, Sachs CW, Treacy G, Zhou H, Pendley CE, Brodmerkel CM, et al. Therapeutic targeting of the IL-12/23 pathways: generation and characterization of ustekinumab. Nat Biotechnol (2011) 29(7):615–24. 10.1038/nbt.1903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Lee YK, Turner H, Maynard CL, Oliver JR, Chen D, Elson CO, et al. Late developmental plasticity in the T helper 17 lineage. Immunity (2009) 30(1):92–107. 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Liu H-P, Cao AT, Feng T, Li Q, Zhang W, Yao S, et al. TGF-β converts Th1 cells into Th17 cells through stimulation of Runx1 expression. Eur J Immunol (2015) 45(4):1010–8. 10.1002/eji.201444726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Sandborn WJ, Su C, Sands BE, D'Haens GR, Vermeire S, Schreiber S, et al. Tofacitinib as Induction and Maintenance Therapy for Ulcerative Colitis. New Engl J Med (2017) 376(18):1723–36. 10.1056/NEJMoa1606910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Panés J, Sandborn WJ, Schreiber S, Sands BE, Vermeire S, D'Haens G. Tofacitinib for induction and maintenance therapy of Crohn’s disease: results of two phase IIb randomised placebo-controlled trials. Gut (2017) 66(6):1049–59. 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Krolopp JE, Thornton SM, Abbott MJ. IL-15 Activates the Jak3/STAT3 Signaling Pathway to Mediate Glucose Uptake in Skeletal Muscle Cells. Front Physiol (2016) 7:626–6. 10.3389/fphys.2016.00626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Richmond JM, Strassner JP, Zapata L, Jr, Garg M, Riding RL, Refat MA, et al. Antibody blockade of IL-15 signaling has the potential to durably reverse vitiligo. Sci Trans Med (2018) 10(450):eaam7710. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aam7710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]