Abstract

Background & Aims

Alcohol-associated liver disease (ALD) is a significant cause of liver-related morbidity and mortality worldwide and with limited therapies. Soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH; Ephx2) is a largely cytosolic enzyme that is highly expressed in the liver and is implicated in hepatic function, but its role in ALD is mostly unexplored.

Methods

To decipher the role of hepatic sEH in ALD, we generated mice with liver-specific sEH disruption (Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl). Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl and control (Ephx2fl/fl) mice were subjected to an ethanol challenge using the chronic plus binge model of ALD and hepatic injury, inflammation, and steatosis were evaluated under pair-fed and ethanol-fed states. In addition, we investigated the capacity of pharmacologic inhibition of sEH in the chronic plus binge mouse model.

Results

We observed an increase of hepatic sEH in mice upon ethanol consumption, suggesting that dysregulated hepatic sEH expression might be involved in ALD. Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl mice presented efficient deletion of hepatic sEH with corresponding attenuation in sEH activity and alteration in the lipid epoxide/diol ratio. Consistently, hepatic sEH deficiency ameliorated ethanol-induced hepatic injury, inflammation, and steatosis. In addition, targeted metabolomics identified lipid mediators that were impacted significantly by hepatic sEH deficiency. Moreover, hepatic sEH deficiency was associated with a significant attenuation of ethanol-induced hepatic endoplasmic reticulum and oxidative stress. Notably, pharmacologic inhibition of sEH recapitulated the effects of hepatic sEH deficiency and abrogated injury, inflammation, and steatosis caused by ethanol feeding.

Conclusions

These findings elucidated a role for sEH in ALD and validated a pharmacologic inhibitor of this enzyme in a preclinical mouse model as a potential therapeutic approach.

Keywords: Soluble Epoxide Hydrolase, Alcohol-Associated Liver Disease, Hepatocyte, Injury, Steatosis, Inflammation, Stress, Pharmacologic Inhibition

Abbreviations used in this paper: ADH, alcohol dehydrogenase; ALD, alcohol-associated liver disease; ALDH, aldehyde dehydrogenase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; CYP, cytochrome P450; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; DiHDPE, dihydroxydocosapentaenoic acid; EETs, epoxyeicosatrienoic acids; EpETE, epoxyeicosatetraenoic acid; EpETrE, epoxyeicosatrienoic acid; EpDPE, epoxydocosapentaenoic acid; EpODE, epoxyoctadecadienoic acid; eIF2α, eukaryotic initiation factor 2α; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; EpFA, epoxy fatty acid; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; 4-HNE, 4-hydroxynonenal; HETE, hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid; IL1β, interleukin 1β; IRE1α, inositol-requiring enzyme-1α; LC, liquid chromatography; mRNA, messenger RNA; MS, mass spectroscopy; NF-κB, nuclear factor-κB; NOX, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase; PERK, protein kinase R-like ER kinase; PPARγ, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ; ROS, reactive oxygen species; sEH, soluble epoxide hydrolase; SOD-1, superoxide dismutase-1; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor-α; TPPU, 1-trifluoromethoxyphenyl-3-(1-propionylpiperidin-4-yl)urea

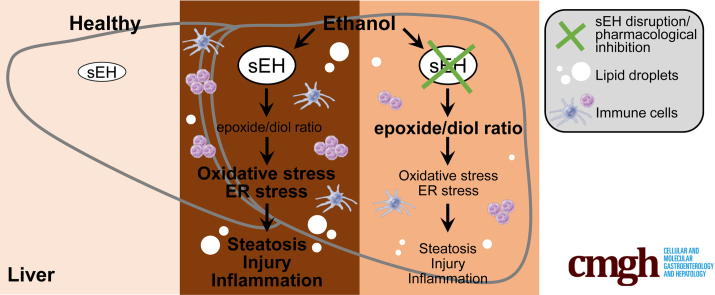

Graphical abstract

Summary

We show that hepatic soluble epoxide hydrolase disruption and pharmacologic inhibition ameliorate injury, inflammation, and steatosis caused by ethanol feeding in a mouse model of alcohol-associated liver disease. In addition, soluble epoxide hydrolase genetic and pharmacologic inactivation is associated with an altered lipid epoxide/diol ratio and attenuation of ethanol-induced oxidative and endoplasmic reticulum stress.

Chronic excessive alcohol intake is a social, economic, and clinical burden,1,2 and a significant contributor to alcohol-associated liver disease (ALD).3 ALD is a major cause of liver-related morbidity and mortality worldwide and has a broad manifestation of hepatic pathologies that include steatosis, hepatocellular injury, inflammation, and progressive fibrosis.4,5 The majority of heavy drinkers develop fatty liver, often being asymptomatic at the early stages, while 30% of these develop more severe forms of ALD.6 The pathogenesis of ALD remains incompletely understood, and effective treatments currently are lacking.6,7 Identifying novel targets is critically needed for the development of mechanism-based pharmacotherapies to advance the management of this disease.

Soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH) is a largely cytosolic enzyme that is highly expressed in the liver, acting mostly in the arachidonic acid cascade. sEH hydrolyzes the anti-inflammatory epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) and other epoxy fatty acids (EpFAs) into the less biologically active or even proinflammatory dihydroxyeicosatrienoic acids and corresponding fatty acid diols.8, 9, 10 Genetic disruption and pharmacologic inhibition of sEH stabilizes EETs and other EpFAs.11 Notably, sEH deficiency in vivo yields beneficial outcomes in rodent disease models, rendering it an attractive therapeutic target,12,13 and pharmacologic inhibitors of sEH are undergoing clinical trials in human beings for different diseases.14 Compelling genetic and pharmacologic evidence implicates sEH in hepatic function. In particular, sEH inactivation ameliorates diet-induced hepatic steatosis,15, 16, 17, 18 mitigates hepatic fibrosis caused by carbon tetrachloride (CCl4),19,20 and attenuates diet-induced endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress.21,22 However, the role of sEH in ALD is largely unexplored.

In the present study, we deployed tissue-specific genetic disruption, pharmacologic inhibition, and targeted metabolomics to decipher the role of sEH in ALD. We provide evidence that hepatic sEH disruption consistently mitigated injury, inflammation, and steatosis caused by ethanol feeding in a mouse model of ALD. Notably, pharmacologic inhibition of sEH ameliorated ethanol-induced injury, inflammation, and steatosis. Furthermore, sEH genetic and pharmacologic inactivation attenuated ethanol-induced hepatic ER and oxidative stress. The current findings implicated hepatic sEH in ALD and identified this enzyme as a potential therapeutic target.

Results

Hepatic sEH-Deficient Mice

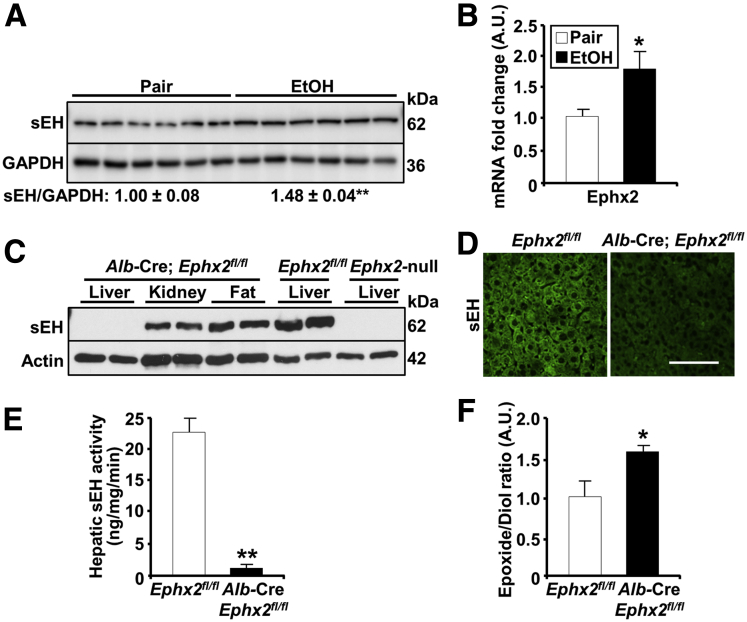

We determined the expression of hepatic sEH in the chronic plus binge mouse model of ALD, which simulates several features of human alcoholic hepatitis.23 Briefly, female mice were acclimated to a liquid diet for 5 days, then fed an ethanol diet or pair-fed for 10 days, followed by a single gavage and euthanized after 9 hours. We observed a modest but significant increase in hepatic sEH protein and Ephx2 messenger RNA (mRNA) in mice fed an ethanol diet compared with pair-fed animals (Figure 1A and B). These observations suggested that dysregulated hepatic sEH expression might be implicated in ALD. To investigate the role of sEH in ALD, we generated mice with liver-specific disruption by breeding Ephx2fl/fl mice with those expressing the Alb-Cre transgene.24 The sEH protein expression was ablated specifically in the livers of the Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl mice, but not in other tissues, including the kidney and adipose tissue (Figure 1C). Liver lysates from Ephx2fl/fl and Ephx2-null mice served as positive and negative controls, respectively (Figure 1C). Similarly, immunostaining of liver sections for sEH presented a reduction in staining in Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl compared with Ephx2fl/fl mice (Figure 1D). In keeping with these findings, Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl mice showed a significant reduction in hepatic sEH activity and corresponding alterations in the lipid epoxide/diol ratio (Figure 1E and F). These findings showed an efficient and selective deletion of hepatic sEH in Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl mice with concomitant changes in enzyme activity and substrate/product ratio.

Figure 1.

Increased hepatic sEH in a mouse model of ALD and generation of mice with hepatic sEH disruption. (A) Immunoblots of sEH and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (n = 6/group) in liver lysates from pair-fed and EtOH-fed Ephx2fl/fl mice. Each lane represents a tissue from a different animal, and sEH expression was normalized with GAPDH. ∗∗P < .01 pair vs EtOH. (B) Ephx2 mRNA in liver samples from pair-fed and EtOH-fed Ephx2fl/fl mice. ∗P < .05 pair vs EtOH. (C) Immunoblots of sEH and actin in lysates of the liver, kidney, and adipose tissue from Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl, and the liver lysates from Ephx2fl/fl and Ephx2-null mice. Each lane represents a tissue from a different animal. (D) Confocal images of liver sections from Ephx2fl/fl and Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl mice immunostained for murine sEH. (E) sEH activity (n = 5–6/group), and (F) epoxide/diol ratio (n = 8/group) in liver samples from pair-fed Ephx2fl/fl and Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl mice. ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01 Ephx2fl/fl vs Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl. AU, arbitrary unit. Scale bar: 50 μm.

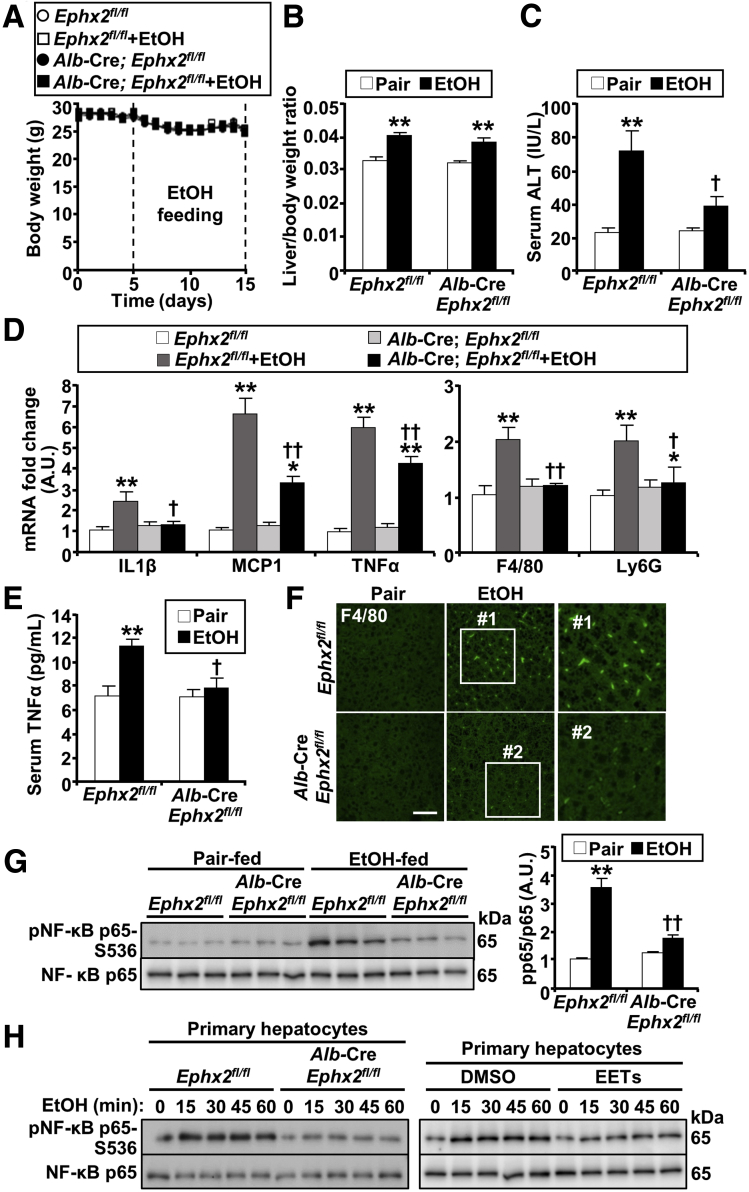

Hepatic sEH Disruption Mitigates Ethanol-Induced Injury, Inflammation, and Steatosis

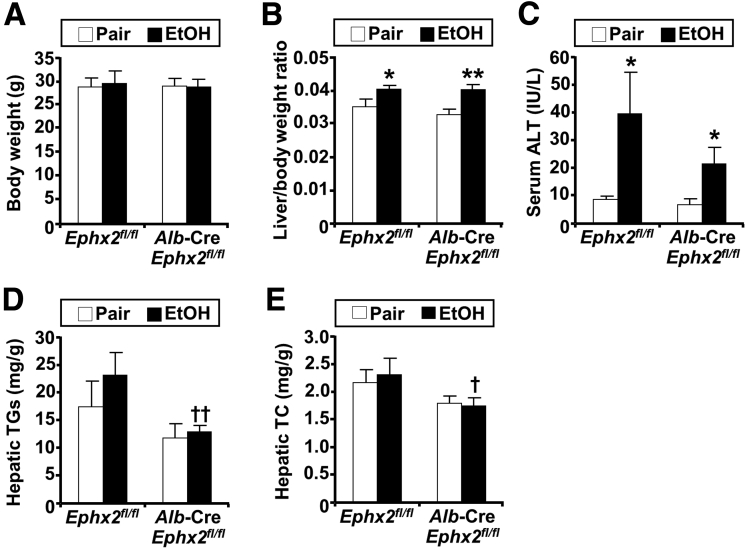

To investigate the effects of hepatic sEH deficiency in ALD, Ephx2fl/fl and Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl female mice were fed an ethanol diet using the chronic plus binge model. Then, hepatic injury, inflammation, and steatosis were evaluated under pair-fed and ethanol-fed states. In these studies, there were no differences in the body weight observed among groups (Figure 2A). In addition, ethanol feeding significantly and comparably increased liver/body weight of Ephx2fl/fl and Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl mice (Figure 2B). Hepatic injury was assessed by serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT), which was increased upon ethanol feeding, but to a significantly lower level in Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl compared with Ephx2fl/fl mice (Figure 2C). Inflammation was evaluated by determining the hepatic mRNA of interleukin 1β (IL1β), monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP1), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα), adhesion G-protein–coupled–receptor E1 (F4/80), and lymphocyte antigen 6 complex, locus G (Ly6G), which showed a significantly lower ethanol-induced increase in Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl compared with Ephx2fl/fl mice (Figure 2D). In addition, circulating TNFα concentration was increased substantially by ethanol feeding in Ephx2fl/fl mice, but with minimal increase in Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl animals (Figure 2E). Immunostaining of liver sections for F4/80 showed an increase in Kupffer cells upon ethanol feeding, and that was more in Ephx2fl/fl than Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl mice (Figure 2F). Moreover, the ethanol-induced increase in hepatic nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) phosphorylation was significantly lower in Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl compared with Ephx2fl/fl mice (Figure 2G). Next, we determined if sEH deficiency ex vivo mimics sEH disruption in vivo and attenuates ethanol-induced inflammation. To this end, we isolated primary hepatocytes from Ephx2fl/fl and Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl mice, and then monitored the effects of ethanol treatment on NF-κB activation. Indeed, the ethanol-evoked increase in NF-κB phosphorylation was mitigated in sEH-deficient hepatocytes compared with those isolated from Ephx2fl/fl mice (Figure 2H). Notably, treatment of primary hepatocytes isolated from wild-type mice with the sEH substrate, EETs, attenuated ethanol-induced NF-κB phosphorylation (Figure 2H).

Figure 2.

Decreased ethanol-induced injury and inflammation in mice with hepatic sEH deficiency. (A) Mouse body weight (n = 8/group) during the course of ethanol feeding. (B) Liver/body weight ratio of pair-fed or EtOH-fed Ephx2fl/fl and Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl mice (n = 8/group). (C) Serum ALT concentration (n = 5–8/group) in pair-fed or EtOH-fed Ephx2fl/fl and Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl mice. (D) mRNA expression of interleukin 1β (IL1β), monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP1), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα), adhesion G-protein–coupled–receptor E1 (F4/80), and lymphocyte antigen 6 complex, locus G (Ly6G) (n = 6/group) in liver samples from pair-fed or EtOH-fed Ephx2fl/fl and Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl mice. (E) Serum TNFα concentration (n = 5–6/group) in pair-fed or EtOH-fed Ephx2fl/fl and Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl mice. (F) Confocal images of liver sections from Ephx2fl/fl and Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl mice immunostained for F4/80. Boxed areas (#1 and #2) are enlarged, as shown in the right panels. Scale bar: 50 μm. (G) Representative immunoblots of phospho-NF-κB (pNF-κB) p65-S536 and NF-κB p65 (n = 6/group) in livers from pair-fed or EtOH-fed Ephx2fl/fl and Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl mice. Each lane represents lysate from a different animal, and the pNF-κB p65-S536 level was normalized with NF-κB p65. (H) Immunoblots of pNF-κB p65-S536 and NF-κB p65 in primary hepatocytes isolated from Ephx2fl/fl and Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl mice (left panel) and wild-type mice (right panel). Cells were treated with EtOH (100 mmol/L) alone (left panel) and co-cultured without (DMSO) and with EETs mixture (2 μmol/L) (right panel) for various time points as indicated. ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01 pair vs EtOH. †P < .05, ††P < .01 Ephx2fl/fl vs Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl. AU, arbitrary unit.

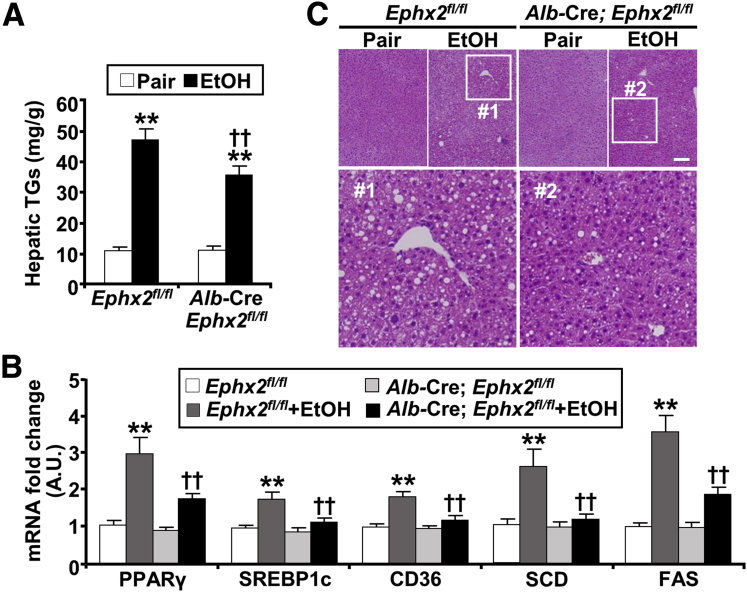

A central and early aspect of ALD is the dysregulation of lipid metabolism and excessive hepatic fat accumulation.25, 26, 27 Ethanol feeding increased hepatic triglycerides as expected, but to a significantly lower extent in Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl compared with Ephx2fl/fl mice (Figure 3A). Consistent with this finding, we observed corresponding alterations in the expression of lipogenesis and fatty acid uptake genes. The ethanol-induced up-regulation of hepatic mRNA of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ), sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c (SREBP1c), cluster of differentiation 36 (CD36), stearoyl-CoA desaturase (SCD), and fatty acid synthase (FAS) was significantly lower in Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl compared with Ephx2fl/fl mice (Figure 3B). In addition, histologic evaluation established accentuated hepatic steatosis in mice fed an ethanol diet, with lipid vacuoles and hepatocyte ballooning, that was smaller in Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl compared with Ephx2fl/fl mice (Figure 3C). Comparable findings were observed in another cohort of older (11 months) Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl female mice (Figure 4). Collectively, these findings showed that hepatic sEH deficiency conferred a significant, albeit partial, protection from injury, inflammation, and steatosis caused by ethanol intake.

Figure 3.

Hepatic sEH deficiency attenuates ethanol-induced steatosis. (A) Hepatic triglycerides (TGs) concentration (n = 7/group), (B) mRNA expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ), sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c (SREBP1c), cluster of differentiation 36 (CD36), stearoyl-CoA desaturase (SCD), and fatty acid synthase (FAS) (n = 6/group), and (C) H&E staining of liver samples from pair-fed or EtOH-fed Ephx2fl/fl and Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl mice. Boxed areas (#1 and #2) are enlarged, as shown under the original images. ∗∗P < .01 pair vs EtOH; ††P < .01 Ephx2fl/fl vs Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl. AU, arbitrary unit. Scale bar: 50 μm.

Figure 4.

Hepatic sEH disruption attenuates hepatic injury and steatosis in a second cohort of mice. (A) Body weight, (B) liver/body weight ratio, (C) serum ALT, (D) hepatic triglycerides (TGs), and (E) hepatic total cholesterol (TC) in 11-month-old pair-fed or EtOH-fed Ephx2fl/fl and Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl mice (n = 6/group). ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01 pair vs EtOH; and †P < .05, ††P < .01 Ephx2fl/fl vs Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl.

sEH Deficiency Altered the Oxylipin Profile and Increased Epoxides in the Liver

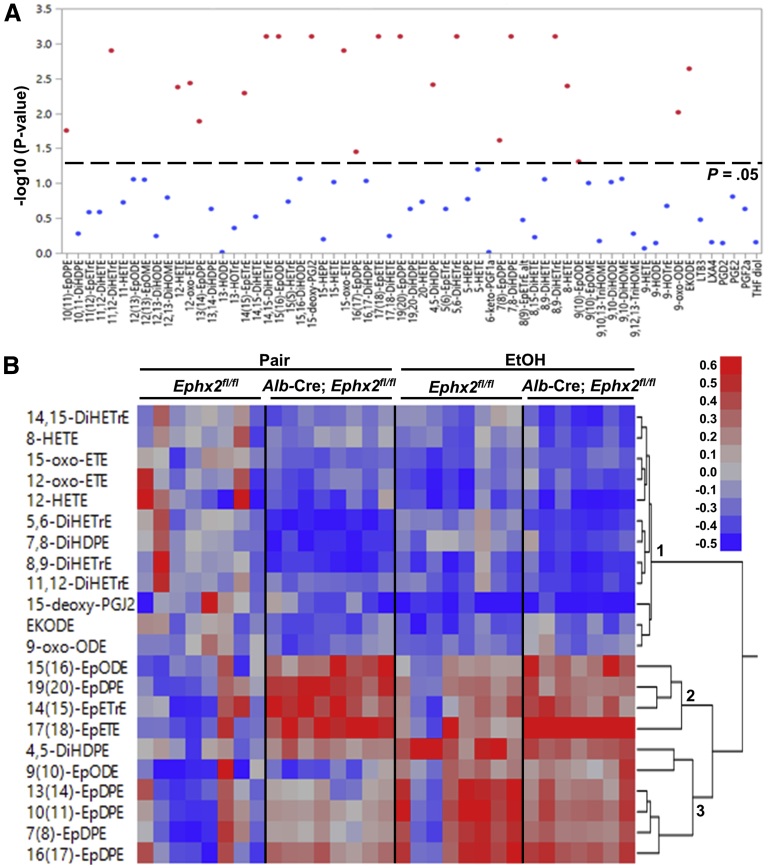

sEH is an established modulator of natural epoxides derived from cytochrome P450 (CYP) activity.28,29 We used liquid chromatography–mass spectroscopy (LC/MS-MS)–based metabolomics to quantitate hepatic oxylipins of Ephx2fl/fl and Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl mice under pair-fed and ethanol-fed states. In total, we detected 63 oxylipins, of which 22 showed significant differences (Figure 5A and Supplementary Table 1). We performed further analysis using hierarchical clustering (Ward’s minimum variance method) and heatmap visualization. Data were expressed as log2 fold change to the control group (pair-fed, Ephx2fl/fl), and the statistically significant oxylipins were divided into 3 clusters (Figure 5B). The first cluster included diols from the CYP pathway and metabolites derived from the cyclooxygenase and lipoxygenase pathways that were decreased by ethanol feeding of Ephx2fl/fl mice and pair-fed and ethanol-fed Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl mice compared with the control group. On the other hand, epoxides in the second cluster (15,16-epoxyoctadecadienoic acid [EpODE], 19,20-epoxydocosapentaenoic acid [EpDPE], 14,15-epoxyeicosatrienoic acid [EpETrE], and 17,18-epoxyeicosatetraenoic acid [EpETE]) were increased significantly in pair-fed and ethanol-fed Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl and, to a lower extent, in ethanol-fed Ephx2fl/fl mice compared with the control group. The third cluster, including 4,5-dihydroxydocosapentaenoic acid (DiHDPE), 9,10-EpODE, and EpDPEs (7,8-, 10,11-, 13,14-, and 16,17-) were increased by ethanol feeding in both genotypes. This approach identified lipid mediators impacted significantly by hepatic sEH deficiency under pair-fed and ethanol-fed conditions.

Figure 5.

Targeted metabolomic profiling of hepatic oxylipins in Ephx2fl/fland Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/flmice. (A) Sixty-three oxylipins were detected in liver samples from pair-fed and EtOH-fed Ephx2fl/fl and Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl mice, 22 were statistically significant (reddots, analysis of variance test with an adjusted false discovery rate cut-off, P = .05). Oxylipins without statistical significance were presented as blue dots. The raw data are listed in Supplementary Table 1. (B) Heat map showing the statistically significant oxylipins in liver samples from pair-fed and EtOH-fed Ephx2fl/fl and Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl mice (n = 7–8/group).

Decreased Ethanol-Induced Hepatic ER and Oxidative Stress in Mice With sEH Deficiency

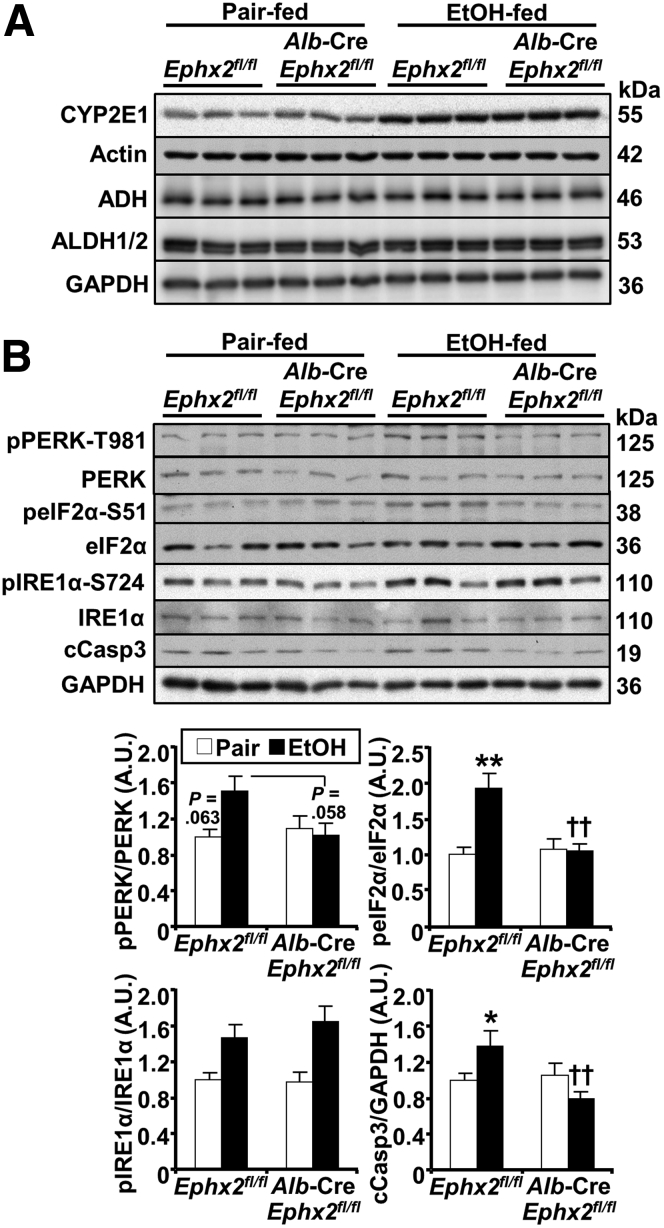

We assayed key signaling pathways that might contribute to sEH action in hepatocytes under ethanol feeding. We discerned whether hepatic sEH deficiency affected ethanol metabolism by measuring the expression of the alcohol-metabolizing enzymes cytochrome P450 2E1 (CYP2E1), alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH), and aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH).30, 31, 32 Ethanol feeding caused a comparable induction in CYP2E1 protein expression in Ephx2fl/fl and Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl mice, whereas ADH and ALDH protein expression was not altered between groups under pair-fed and ethanol-fed conditions (Figure 6A). These observations suggested that ethanol metabolism likely was comparable between the 2 genotypes.

Figure 6.

Decreased ethanol-induced ER stress in mice with hepatic sEH disruption. Immunoblots of (A) CYP2E1, actin, ADH, ALDH1/2, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (n = 3/group), and (B) representative immunoblots of phospho-PERK-T981, PERK, phospho-eIF2α-S51, eIF2α, phospho-IRE1α, IRE1α, cleaved Caspase 3 (cCasp3), and GAPDH (n = 6/group) in liver samples from pair-fed or EtOH-fed Ephx2fl/fl and Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl mice. Each lane represents a tissue from a different animal. cCasp3 expression was normalized with GAPDH, and phosphorylation of PERK, eIF2α, and IRE1α were normalized with their respective protein. ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01 pair vs EtOH. ††P < .01 Ephx2fl/fl vs Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl. AU, arbitrary unit.

In hepatocytes, ethanol and its metabolites impair proper protein folding within the ER lumen and disturb its redox status, leading to ER stress.33,34 This is countered by the unfolded protein response, which includes 3 branches controlled by the ER transmembrane proteins protein kinase R-like ER kinase (PERK), inositol-requiring enzyme-1α (IRE1α), and activating transcription factor 6.35,36 Immunoblots of hepatic lysates showed a trend for increased PERK phosphorylation in Ephx2fl/fl mice upon ethanol feeding and attenuation in Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl mice (Figure 6B). In addition, phosphorylation of PERK’s downstream target eukaryotic initiation factor 2α (eIF2α) was increased upon ethanol feeding in Ephx2fl/fl and attenuated significantly in Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl mice. On the other hand, comparable phosphorylation of hepatic IRE1α was observed in Ephx2fl/fl and Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl mice upon ethanol feeding. Nevertheless, Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl showed a significantly lower ethanol-induced cleaved Caspase 3 protein expression compared with Ephx2fl/fl mice (Figure 6B).

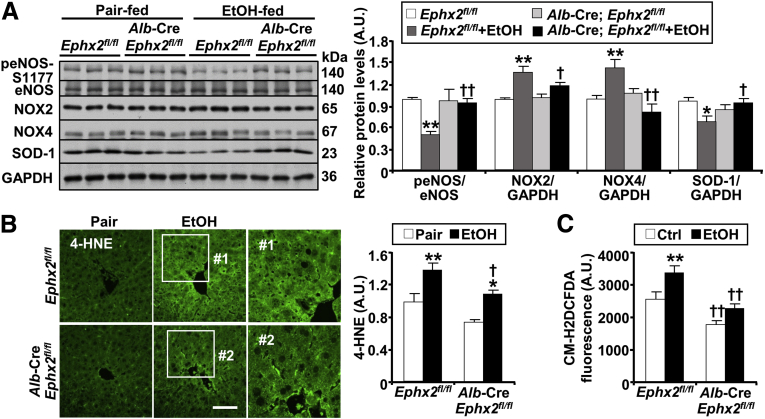

Ethanol metabolism increases oxidative stress and the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), contributing to hepatocyte injury.37,38 We monitored the effects of sEH deficiency on hepatic oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation. Ethanol feeding attenuated endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) phosphorylation and up-regulated nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase 2 (NOX2) and NOX4 protein expression, which were mitigated in Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl mice (Figure 7A). In line with these findings, an ethanol-induced decrease of superoxide dismutase-1 (SOD-1) protein expression was mitigated by hepatic sEH deficiency (Figure 7A). A marker of oxidative stress is the formation of protein adducts with 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE).39 Consistent with the diminished oxidative stress in Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl mice, lipid peroxidation, assessed by 4-HNE immunostaining, was significantly lower in these mice compared with Ephx2fl/fl mice (Figure 7B). Moreover, the basal and ethanol-induced ROS concentrations, assessed by chloromethyl dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate, were significantly lower in primary hepatocytes isolated from Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl than those from Ephx2fl/fl mice (Figure 7C). Thus, hepatic sEH deficiency was associated with a significant attenuation of ethanol-induced ER and oxidative stress.

Figure 7.

sEH deficiency attenuates ethanol-induced oxidative stress. (A) Representative immunoblots of phospho-eNOS-S1177, eNOS, NOX2, NOX4, SOD-1, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (n = 6/group), and (B) immunostaining of 4-HNE in liver samples from pair-fed or EtOH-fed Ephx2fl/fl and Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl mice. Each lane represents a tissue from a different animal. Protein expression of NOX2, NOX4, and SOD-1 was normalized with GAPDH, and peNOS-S1177 was normalized with eNOS expression. Boxed areas (#1 and #2) were enlarged, and the intensity of 4-HNE staining was quantified using ImageJ and presented in the bar chart. Statistical significance in (A) and (B) was considered as ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01 pair vs EtOH. †P < .05, ††P < .01 Ephx2fl/fl vs Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl. Scale bar: 25 μm. (C) Intracellular ROS levels as measured by chloromethyl dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (CM-H2DCFDA) in primary hepatocytes isolated from Ephx2fl/fl and Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl mice. Hepatocytes were treated without (Ctrl) and with ethanol (100 mmol/L) for 60 minutes. The CM-H2DCFDA fluorescence was plotted in the bar chart. Statistical significance in (C) was considered as ∗∗P < .01 Ctrl vs EtOH. ††P < .01 Ephx2fl/fl vs Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl. AU, arbitrary unit.

Targeting sEH Ameliorated Hepatic Injury, Inflammation, and Steatosis Caused by Ethanol Feeding

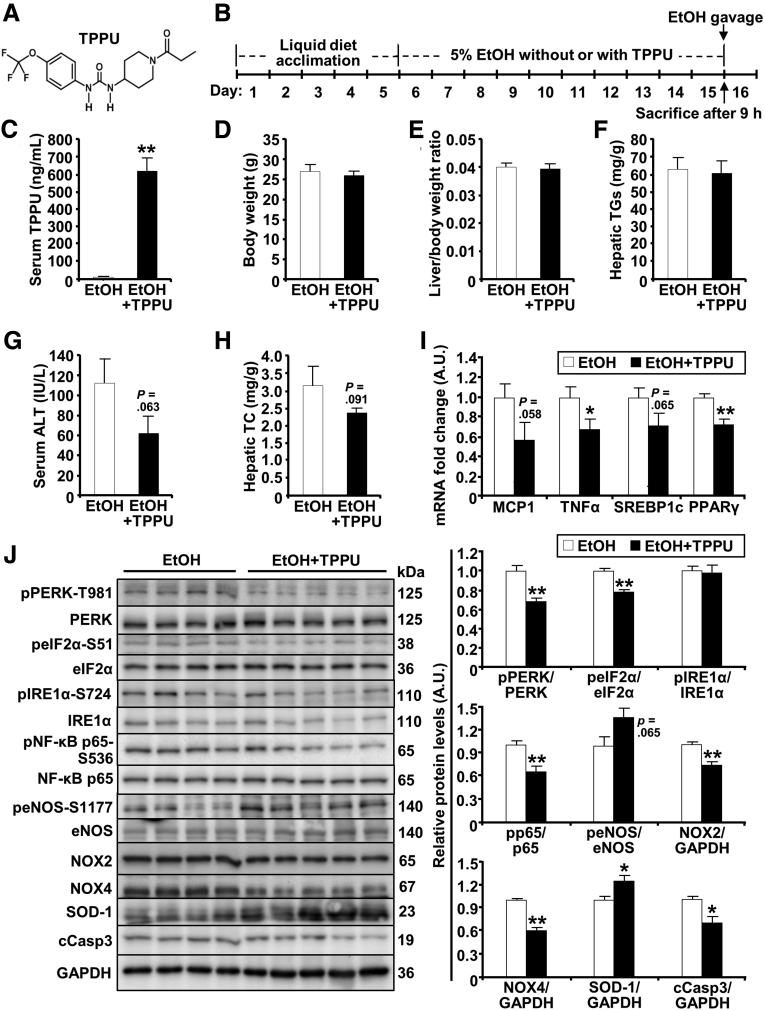

Given the beneficial effects of genetic deficiency of hepatic sEH, we evaluated the impact of pharmacologic inhibition of this enzyme in the chronic plus binge model. To this end, mice were treated with the selective sEH pharmacologic inhibitor 1-trifluoromethoxyphenyl-3-(1-propionylpiperidin-4-yl)urea (TPPU)40 (Figure 8A). Briefly, female mice were fed a 5% (v/v) ethanol diet with or without TPPU as outlined (Figure 8B). We detected significantly increased concentrations of TPPU in the treated mice compared with nontreated controls (Figure 8C). TPPU-treated mice did not show differences in body weight, liver/body weight ratio, and hepatic triglycerides levels compared with nontreated animals (Figure 8D–F). In addition, TPPU-treated mice showed a trend for decreased ALT and hepatic total cholesterol compared with nontreated animals (Figure 8G and H). Furthermore, pharmacologic inhibition of sEH significantly decreased hepatic mRNA expression of inflammatory (TNFα) and lipogenic (PPARγ) genes compared with nontreated animals (Figure 8I). Notably, pharmacologic inhibition of sEH, comparable with hepatic sEH deficiency, attenuated ethanol-induced inflammation and stress as evidenced by alterations in the phosphorylation of PERK, eIF2α, NF-κB, and eNOS, as well as the protein expression of NOX2/4, SOD-1, and cleaved Caspase 3 in TPPU-treated vs nontreated mice (Figure 8J). These findings established the protective effects of pharmacologic inhibition of sEH in a preclinical mouse model of ALD and suggested a potential benefit in targeting sEH.

Figure 8.

Pharmacologic inhibition of sEH attenuates hepatic ethanol-induced injury, inflammation, steatosis, and stress signaling. (A) Structure of the sEH pharmacologic inhibitor TPPU. (B) Timeline of pharmacologic inhibition of sEH in the chronic plus binge model of ALD. (C) Serum TPPU (n = 4–5/group), (D) body weight (n = 5–6/group), (E) liver/body weight ratio (n = 5–6/group), (F) hepatic triglycerides (TGs, n = 5–6/group), (G) serum ALT (n = 4–5/group), (H) hepatic total cholesterol (TC, n = 4–5/group), (I) hepatic mRNA expression of monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP1), TNFα, sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c (SREBP1c), and PPARγ (n = 4/group), and (J) hepatic immunoblots of phospho-PERK-T981, PERK, phospho-eIF2α-S51, eIF2α, phospho-IRE1α, IRE1α, phospho-NF-κB p65-S536, NF-κB p65, phospho-eNOS-S1177, eNOS, NOX2, NOX4, SOD-1, cleaved Caspase 3 (cCasp3), and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (n = 4–5/group) in Ephx2fl/fl mice without (EtOH) and with sEH inhibitor (EtOH + TPPU). Phosphorylation of PERK, eIF2α, IRE1α, NF-κB p65, and eNOS were normalized with their respective protein, and protein expression of NOX2, NOX4, SOD-1, and cCasp3 were normalized with GAPDH. ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01 EtOH vs EtOH + TPPU. AU, arbitrary unit.

Discussion

Advancing therapies for ALD has been limited by an incomplete understanding of the underlying mechanisms, identification of novel targets for intervention, and the development of effective pharmacotherapies. Herein, we report that ethanol feeding up-regulated hepatic sEH in the chronic plus binge model of ALD, whereas hepatic sEH deficiency ameliorated ethanol-induced liver injury, inflammation, and steatosis. In addition, sEH deficiency attenuated hepatic ER and oxidative stress under the ethanol challenge. Furthermore, pharmacologic inhibition of sEH recapitulated the effects of hepatic sEH disruption. Altogether, these findings elucidated a role for sEH in ALD and validated a pharmacologic inhibitor of sEH in a preclinical mouse model as a potential therapeutic approach.

The ethanol-induced increase of hepatic sEH in a mouse model of ALD is in keeping with the enhanced expression of this enzyme in murine models of liver injury.15,21,41 We postulate that the up-regulation of sEH upon ethanol feeding decreases epoxides and increases diols, and may contribute to disease. Of note, alterations in the epoxide/diol ratios have been linked qualitatively to the pathogenesis of several diseases.9,41 Indeed, the epoxide/diol ratio was increased in the Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl mice that ameliorated the adverse effects of ethanol feeding. A limitation is that the modulation of sEH expression in a mouse model may not simulate the human alcoholic hepatitis, and comprehensive studies are warranted to evaluate sEH expression during disease progression in humans. In addition, the present study did not address the factors influencing sEH up-regulation. To wit, angiotensin II induces ER stress in coronary artery endothelial cells and enhances sEH expression, whereas mitigation of stress decreases sEH.42 Given that ethanol metabolites lead to ER stress,33,43 it is reasonable to speculate that ethanol-induced ER stress may contribute to sEH up-regulation. At any rate, the findings herein suggested that the dysregulation of hepatic sEH and the subsequent alteration in the lipid epoxide/diol ratio might contribute to the pathogenesis of ALD.

Hepatic sEH disruption ameliorated ALD in independent cohorts of female mice. Using a genetic loss-of-function approach, we generated mice with efficient and liver-specific sEH deficiency. Importantly, the ablation of hepatic sEH correlated with attenuation of enzyme activity and alteration in the lipid epoxide/diol ratio. The choice of mice with the Alb-Cre transgene was prompted by its efficiency, although deletion in nonparenchymal hepatic cells is unlikely.24 The mitigation of ethanol-induced hepatic injury in Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl mice is consistent with the hepatoprotective effects of genetic and pharmacologic inactivation of sEH.15,19, 20, 21,41 Similarly, the attenuation of ethanol-induced inflammation in Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl mice is in line with the compelling body of evidence showing that sEH deficiency mitigates challenge-induced inflammation.22,44 In addition, the amelioration of inflammation by sEH deficiency was cell-autonomous because it was reproduced in sEH-deficient primary hepatocytes, but the potential contribution of other hepatic cells and tissues in vivo cannot be excluded. Importantly, treatment of hepatocytes with the sEH substrate, EETs, diminished ethanol-induced NF-κB activation in keeping with the anti-inflammatory properties of these lipid mediators.45,46 Furthermore, sEH deficiency ameliorated the effects of ethanol that promote hepatic fatty acid uptake and de novo lipid synthesis, dysregulates fatty acid oxidation, and impairs lipid export, which culminate in hepatic steatosis.25, 26, 27,47 This observation is in accordance with diminished diet-induced hepatic steatosis upon pharmacologic inhibition of sEH.17,18 It is noteworthy that hepatic sEH deficiency may affect other tissues. Indeed, modulation of hepatic sEH alters the 14,15-epoxyeicosatrienoic acid (14,15-EpETrE) plasma level that, in turn, targets astrocytes to impact depression.48 Herein, targeted metabolomics identified lipid metabolites that were altered upon sEH deficiency and provided a potential link between the metabolites and the evaluated parameters. sEH activity correlated positively with FA diols dihydroxyicosatrienoic acid (5,6-, 8,9-, 11,12-, and 14,15-) and dihydroxydocosapentaenoic acid (7,8-, 13,14-), and negatively with EpFA (19,20-epoxydocosapentaenoic acid, 17,18- epoxyeicosatetraenoic acid, 15,16-epoxyoctadecadienoic acid, and 14,15-EpETrE). The EpFA correlated negatively with hepatic IL1β and TNFα, suggesting that the increase in these epoxides may mediate some of the effects of sEH deficiency. Moreover, a negative correlation between hepatic triglycerides and cholesterol with hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids (HETEs) was noted. This finding is in keeping with alterations in 5-, 8-, and 11-HETEs in lean mice upon ethanol consumption.49 Therefore, hepatic sEH deficiency confers limited protection against ethanol intake that may be mediated, at least in part, by an increase in sEH substrates.

The molecular mechanisms underlying ALD pathogenesis are complex and multifactorial. Herein, we showed that hepatic sEH deficiency likely did not affect ethanol metabolism given the comparable expression of the inducible and noninducible alcohol-metabolizing enzymes in Ephx2fl/fl and Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl mice. Significantly, sEH deficiency and pharmacologic inhibition modulated signaling pathways that are implicated in ALD, namely ER and oxidative stress. Consistent with the reported effects of sEH deficiency in mitigating metabolically-induced ER stress,21,29 sEH inactivation ameliorated xenobiotic-induced ER stress. Attenuation of the PERK-eIF2α but not the IRE1α branch of the unfolded protein response upon sEH inactivation suggested potential selective modulation that warrants additional investigation. Moreover, the ethanol-induced oxidative stress, a significant contributor to hepatocyte injury, was abrogated upon sEH inactivation, as evidenced by eNOS phosphorylation, NOX2/4, and SOD-1 expression, ROS levels, and the consequential reduction of lipid peroxidation. These observations are in line with the effects of sEH deficiency in mitigating oxidative stress in multiple tissues.20,50,51 The intricate mechanisms governing the modulation of ethanol-induced ER and oxidative stress require additional investigation, but these pathways emerged herein as contributors to the salutary effects of sEH inactivation. Nonetheless, the role of other pathways cannot be excluded with the inhibition of sEH attenuating ethanol-induced cardiac fibrosis by affecting autophagy flux.52

Pharmacologic inhibition of sEH using TPPU recapitulated the effects of genetic disruption of sEH, ameliorating ethanol-induced injury, inflammation, steatosis, and attenuating oxidative and ER stress. TPPU likely engaged hepatic as well as nonhepatic sEH given the systemic delivery, and presumably conferred protection against ethanol consumption in multiple tissues. Nevertheless, the outcome of pharmacologic inhibition of sEH did not appear more robust than hepatic sEH deficiency. The underlying reason(s) remains to be determined, and a possibility includes a thorough ablation of sEH in the liver using the genetic approach. In addition, off/other target effects of TPPU cannot be excluded, although unlikely given the validation of this inhibitor.40 Moreover, the present study solely evaluated the preventative capacity of targeting sEH in a preclinical ALD model. However, the assessment of the treatment capability of sEH inhibition was precluded by the rapid recovery in the mouse model used herein. Given the seemingly overwhelming challenges of sustaining lifestyle changes and chronic excessive alcohol intake, an intervention that encompasses pharmacologic inhibition of sEH may help address an unmet need for ALD.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

Antibodies for β-actin (sc-47778), eIF2α (sc-133132), phospho-PERK-T981 (sc-32577), phospho-eNOS-S1177 (sc-21871-R), eNOS (sc-376751), SOD-1 (sc-271014), ADH (sc-133207), and ALDH1/2 (sc-166362) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX); NOX2 (ab129068), NOX4 (ab216654), 4-HNE (ab46545), and CYP2E1 (ab28146) were from Abcam (Cambridge, MA); phospho-eIF2α-S51 (9721), PERK (3192), IRE1α (3294), phospho-NF-κB p65-Ser536 (3033), NF-κB p65 (8242), cleaved Caspase 3 (9664), F4/80 (70076), and glyceride-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH, 3683) were from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA); and phospho-IRE1α-S724 (NB100-2323) was from Novus Biologicals (Littleton, CO). Dr Hammock’s laboratory provided antibodies for mouse sEH,53 EETs mixture (8,9-EpETrE [16.9%], 11,12-EpETrE [52.9%], 14,15-EpETrE [30.2%]), and the sEH pharmacologic inhibitor TPPU.54 All other chemicals, unless indicated, were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

Mouse Studies

Mice with hepatic sEH disruption were generated by breeding Ephx2fl/fl mice (kindly provided by Dr Darryl Zeldin, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences) with mice expressing the Alb-Cre transgene (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME). Both strains were on a C57BL/6J background. Genotyping for the Ephx2 floxed allele and Cre gene was performed by polymerase chain reaction using DNA extracted from tails. Mice were maintained under standard conditions with access to water and food (Purina lab chow, #5001; St. Louis, MO). For the ethanol challenge, Ephx2fl/fl and Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl female mice (6 and 11 months of age) were fed ethanol following the chronic plus single binge model.23 Mice were fed a control liquid diet (F1259SP; Bio-Serv, Flemington, NJ) ad libitum for 5 days for acclimation. During the next 10 days, mice were fed either an ethanol liquid diet (F1258SP; Bio-Serv) containing 5% (v/v) ethanol ad libitum or pair-fed with the isocaloric control liquid diet. On the morning of day 16, ethanol-fed and pair-fed mice were gavaged orally with ethanol (5 g/kg body weight) or isocaloric maltose-dextrin solution, respectively, then euthanized after 9 hours. For studies with the pharmacologic inhibitor of sEH, Ephx2fl/fl female mice (8 months old) were treated daily with TPPU (1.5 mg/kg).40,55 TPPU was dissolved in polyethylene glycol 400, then diluted in Lieber–DeCarli ethanol liquid diet (1:100), and administered concomitantly with ethanol until the mice were sacrificed and then tissues were collected and stored at −80°C. In addition, liver tissue was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for histologic analysis.

Biochemical Analyses

ALT was determined using the ALT/serum glutamate pyruvate transaminase enzymatic colorimetric kit (Teco Diagnostics, Anaheim, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cytokines were determined by the V-PLEX Mouse Cytokine kit (K152A0H-1; Meso Scale Discovery, Rockville, MD) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For hepatic triglyceride measurement, approximately 25 mg of liver homogenate was mixed with chloroform/methanol solution (2:1 v/v), followed by vigorous shaking for 3 minutes. The mixture was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 minutes at room temperature, and the bottom chloroform layer was collected and dried overnight. The resulting pellet was resuspended in isopropanol, and the triglyceride concentration was measured with the Infinity Triglycerides Reagent enzymatic colorimetric kit (TR22421; Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) according to the manufacturer’s instruction.

Immunoblot Analysis

Frozen tissues were ground in liquid nitrogen and proteins were extracted by radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer containing 10 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mmol/L NaCl, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 1% Triton X-100, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 5 mmol/L EDTA, 20 mmol/L sodium fluoride, 2 mmol/L sodium orthovanadate, and protease inhibitors. Lysates were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 minutes, and protein concentrations were determined using the bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Proteins were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and then transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Immunoblotting was performed with the indicated antibodies, then visualized using the HyGLO Chemiluminescent horseradish-peroxidase detection reagent (Denville Scientific, Metuchen, NJ).

Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

Total RNA was extracted from the liver using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Complementary DNA was generated using a high-capacity complementary DNA reverse-transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction was performed by mixing samples and SsoAdvanced Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) to each primer pair and using the CFX96 Touch Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction Detection System (Bio-Rad). mRNAs of Ephx2, interleukin 1β, monocyte chemotactic protein 1, tumor necrosis factor-α, adhesion G-protein–coupled–receptor E1, lymphocyte antigen 6 complex, locus G, PPARγ, sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c, cluster of differentiation 36, stearoyl-CoA desaturase, and fatty acid synthase were normalized to TATA-box binding protein. The primers sequences are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of Primer Sequences Used for Polymerase Chain Reaction Studies

| Targets | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| mouse-Ephx2 flox | TGCCACCAGATCCTGAT | GGCAACTTTGTGATGTTC |

| general Cre recombinase | ATGTCCAATTTACTGACCG | CGCCGCATAACCAGTGAAAC |

| mouse-Ephx2 | GGACGACGGAGACAAGAGAG | CTGTGTTGTGGACCAGGATG |

| mouse-interleukin 1β | TAGCTTCAGGCAGGCAGTATC | TAAGGTCCACGGGAAAGACAC |

| mouse-tumor necrosis factor-α | TGACGTGGAACTGGCAGAAGAG | TTGCCACAAGCAGGAATGAGA |

| mouse-monocyte chemotactic protein 1 | CCCAATGAGTAGGCTGGAGA | TCTGGACCCATTCCTTCTTG |

| mouse-adhesion G-protein–coupled–receptor E1 | CTTTGGCTATGGGCTTCCAGTCC | GCAAGGAGGACAGAGTTTATCGTG |

| mouse-lymphocyte antigen 6 complex, locus G | TGCGTTGCTCTGGAGATAGA | CAGAGTAGTGGGGCAGATGG |

| mouse-sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c | GAGCCATGGATTGCACATTT | CTCAGGAGAGTTGGCACCTG |

| mouse-peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ | TCTTAACTGCCGGATCCACAA | GCCCAAACCTGATGGCATT |

| mouse-cluster of differentiation 36 | GATGACGTGGCAAAGAACAG | TCCTCGGGGTCCTGAGTTAT |

| mouse-stearoyl-CoA desaturase | TTCTTGCGATACACTCTGGTGC | CGGGATTGAATGTTCTTGTCGT |

| mouse-fatty acid synthase | GGAGGTGGTGATAGCCGGTAT | TGGGTAATCCATAGAGCCCAG |

| mouse-TATA-box binding protein | TGAGAGCTCTGGAATTGTAC | CTTATTCTCATGATGACTGCAG |

Histology

Liver samples were embedded, sectioned, and H&E-stained by the UC Davis Anatomic Pathology Service. The slides were imaged using an Olympus (Center Valley, PA) BX51 microscope. For immunofluorescence, liver sections from Ephx2fl/fl and Alb-Cre; Ephx2fl/fl mice were fixed (4% paraformaldehyde), embedded in paraffin, and deparaffinized in xylene. Sections were stained with antibodies for sEH and F4/80 overnight at 4°C. Detection was performed with appropriate Alexa Fluor secondary antibodies (Thermo Scientific), and visualized using Olympus FV1000 laser scanning confocal microscopy.

sEH Activity

Hepatic sEH activity was measured using [3H]-labeled trans-diphenyl propene oxide as a substrate as described54 with minor modifications. Briefly, the liver extract was obtained by homogenizing tissue samples in 250 μL of RPMI medium (1 mmol/L dithiothreitol and 500 μmol/L phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) and centrifuging at 10,000 × g for 20 minutes at 4°C. Two sets of 100-μL liver extracts were prepared from each sample for further isooctane and hexanol extractions. The liver extract was incubated with [3H]-labeled trans-diphenyl propene oxide for 20 minutes at 37ºC, and the reactions stopped by adding 60 μL methanol. Then, 200 μL isooctane (reflects sEH activity + glutathione transferase activity) or hexanol (reflects glutathione transferase activity only) was added to the tube and thoroughly mixed until an emulsion formed. Phases were separated by centrifugation at 1,500 × g for 5 minutes at room temperature. A 40-μL sample of the bottom aqueous phase was collected and radioactivity was measured with a liquid scintillation counter (Tri-Carb 2810TR; Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA). The sEH activity was determined by subtracting the amount of radiation from the hexanol extraction from the value resulting from the isooctane extraction, which then was corrected for incubation time and normalized for protein amount.

Measurement of sEH Inhibitor

The concentration of TPPU in blood was determined as described.56 In short, 10 μL blood was collected and added into 50 μL 0.1% EDTA water solution. Samples were analyzed by multiple reaction-monitoring modes on the 4000 QTRAP mass spectrometer (Sciex, Framingham, MA) and referenced to an internal standard. The optimized parameters of mass spectrometers for monitoring this sEH inhibitor are described as follows: transition from first quadrupole to third quadrupole was 358.2 to 175.9 mass-to-charge ratio, declustering potential was -125 V, entrance potential was -10 V, collision energy was -22 eV, collision cell exit potential was -11 V, and LOD was ≤0.49 nmol/L.

Oxylipins Extraction

Oxylipins were analyzed as described previously.57 In brief, liver samples (∼50 mg) were treated with 200 μL cold methanol extraction solution (0.1% acetic acid and 0.1% butylated hydroxytoluene), added to 10 μL of deuterated (d) internal standard solution (500 nmol/L mixture of d11 11,12-EpETrE, d11 14,15-DiHETrE, d8 9-hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid, d4 leukotriene B4, d4 prostaglandin E2, d4 thromboxane B2, d6 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid, d4 6-keto prostaglandin F1α, and d8 5-HETE; Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI). Samples were stored at -80°C for 30 minutes. Then, the samples were homogenized using Retsch MM301 ball mills (Retsch GmbH, Newtown, PA) at 30 Hz for 10 minutes and stored at -80°C overnight. On the next day, homogenates were centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 10 minutes, the supernatant was collected, and the remaining pellets were washed with 100 μL ice-cold methanol extraction solution and centrifuged for 10 minutes. Supernatants acquired in the previous steps were combined and diluted with 1 mL H2O and loaded onto Waters Oasis HLB 3cc solid-phase extraction cartridges. The LC/MS-MS analysis was performed with an Agilent (Santa Clara, CA) 1200SL Ultra High Performance Liquid Chromatography system interfaced with a 4000 QTRAP mass spectrometer (Sciex). Separation of oxylipins was performed with the Agilent Eclipse Plus C18 150 × 2.1 mm 1.8-μm column with mobile phases of water with 0.1% acetic acid as mobile phase A, and acetonitrile/methanol (84/16) with 0.1% acetic acid as mobile phase B. Therefore, LC separation conditions and all parameters on the MS were optimized with pure standards (Cayman Chemical) under negative mode.57

Primary Hepatocyte Isolation and Culture

Mouse hepatocyte isolation and culture were performed as reported58 with few modifications, as we described.59 For the measurement of ROS, the primary hepatocytes were incubated with 6-chloromethyl-2',7'-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate, acetyl ester (50 μg/24-well plates; Thermo Scientific) for 30 minutes at 37ºC. Then, the cells were treated with ethanol (100 mmol/L) for an additional 60 minutes at 37ºC. The ROS level was measured by excitation at 492-nm and emission at 522-nm wavelengths using BioTek’s Synergy H1 (Winooski, VT). For EETs treatment, primary hepatocytes were pre-incubated without (dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO]) and with 2 μmol/L EETs mixture for 30 minutes at 37ºC. The cells then were co-cultured with 100 mmol/L ethanol and 2 μmol/L EETs mixture or DMSO for an additional 60 minutes at 37ºC. DMSO was used as a vehicle control with the same volume of the EETs mixture.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as means ± SEM. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Comparison among multiple groups was made using a 1-way analysis of variance with the post hoc Tukey test and a 2-tailed t test for comparing 2 groups. Differences were considered significant at P < .05, and highly significant at P < .01.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Darryl Zeldin (National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences) for providing the Ephx2fl/fl mice.

Current address of A.M.: University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

CRediT Authorship Contributions

Aline Mello (Data curation: Equal; Formal analysis: Equal; Writing – original draft: Lead; Writing – review & editing: Supporting);

Ming-Fo Hsu (Data curation: Equal; Formal analysis: Equal; Writing – review & editing: Equal);

Shinichiro Koike (Data curation: Supporting; Formal analysis: Supporting; Writing – review & editing: Supporting);

Bryan Chu (Data curation: Supporting);

Jeff Cheng (Data curation: Supporting; Formal analysis: Supporting; Methodology: Supporting);

Jun Yang (Data curation: Supporting; Formal analysis: Supporting; Methodology: Supporting; Writing – review & editing: Supporting);

Christophe Morisseau (Data curation: Supporting; Methodology: Supporting; Writing – review & editing: Supporting);

Natalie J. Torok (Conceptualization: Supporting; Investigation: Supporting; Methodology: Supporting; Writing – review & editing: Supporting);

Bruce D. Hammock (Investigation: Supporting; Methodology: Supporting; Writing – review & editing: Supporting);

Fawaz G. Haj (Conceptualization: Lead; Funding acquisition: Lead; Investigation: Equal; Project administration: Lead; Resources: Lead; Supervision: Lead; Writing – review & editing: Lead).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest FGH and BDH are co-inventors on patents related to soluble epoxide hydrolase by the University of California. BDH is a co-founder of EicOsis LLC that aims to use sEH inhibitors for the treatment of neuropathic and inflammatory pain.

Funding Research in the Torok laboratory is funded by grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (United States) 2R01DK083283 and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (United States) Merit Award 2I01BX002418; research in the Hammock laboratory is funded by Revolutionizing Innovative, Visionary Environmental Health Research Award R35ES030443, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (United States) grant P42ES04699, and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (United States) grant U24DK097154; and research in the Haj laboratory is funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (United States) grant RO1DK095359 and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (United States) grant P42ES04699. Also, A.M. was supported, in part, by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES, Brazil) and National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (United States) P42ES04699, and M.-F.H. was supported, in part, by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (United States) grant R21AA027633. Fawaz G. Haj is a Co-Leader of the Endocrinology and Metabolism Core at the UC Davis Mouse Metabolic Phenotyping Center, which is funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (United States) grant U24DK092993. The Light Microscopy Imaging Facility (Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology, UC Davis) is supported by National Institutes of Health (United States) grant 1S10RR019266.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Global status report on alcohol and health 2018. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rehm J., Shield K.D. Global alcohol-attributable deaths from cancer, liver cirrhosis, and injury in 2010. Alcohol Res. 2013;35:174–183. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Osna N.A., Donohue T.M., Jr., Kharbanda K.K. Alcoholic liver disease: pathogenesis and current management. Alcohol Res. 2017;38:147–161. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gao B., Bataller R. Alcoholic liver disease: pathogenesis and new therapeutic targets. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1572–1585. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crabb D.W., Im G.Y., Szabo G., Mellinger J.L., Lucey M.R. Diagnosis and treatment of alcohol-associated liver diseases: 2019 practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2020;71:306–333. doi: 10.1002/hep.30866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seitz H.K., Bataller R., Cortez-Pinto H., Gao B., Gual A., Lackner C., Mathurin P., Mueller S., Szabo G., Tsukamoto H. Alcoholic liver disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:16. doi: 10.1038/s41572-018-0014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh S., Osna N.A., Kharbanda K.K. Treatment options for alcoholic and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a review. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:6549–6570. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i36.6549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Enayetallah A.E., French R.A., Thibodeau M.S., Grant D.F. Distribution of soluble epoxide hydrolase and of cytochrome P450 2C8, 2C9, and 2J2 in human tissues. J Histochem Cytochem. 2004;52:447–454. doi: 10.1177/002215540405200403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spector A.A., Norris A.W. Action of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids on cellular function. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C996–C1012. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00402.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Node K., Huo Y., Ruan X., Yang B., Spiecker M., Ley K., Zeldin D.C., Liao J.K. Anti-inflammatory properties of cytochrome P450 epoxygenase-derived eicosanoids. Science. 1999;285:1276–1279. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5431.1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shen H.C., Hammock B.D. Discovery of inhibitors of soluble epoxide hydrolase: a target with multiple potential therapeutic indications. J Med Chem. 2012;55:1789–1808. doi: 10.1021/jm201468j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inceoglu B., Schmelzer K.R., Morisseau C., Jinks S.L., Hammock B.D. Soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibition reveals novel biological functions of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2007;82:42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Imig J.D., Hammock B.D. Soluble epoxide hydrolase as a therapeutic target for cardiovascular diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:794–805. doi: 10.1038/nrd2875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Imig J.D. Prospective for cytochrome P450 epoxygenase cardiovascular and renal therapeutics. Pharmacol Ther. 2018;192:1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2018.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu Y., Dang H., Li D., Pang W., Hammock B.D., Zhu Y. Inhibition of soluble epoxide hydrolase attenuates high-fat-diet-induced hepatic steatosis by reduced systemic inflammatory status in mice. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schuck R.N., Zha W., Edin M.L., Gruzdev A., Vendrov K.C., Miller T.M., Xu Z., Lih F.B., DeGraff L.M., Tomer K.B., Jones H.M., Makowski L., Huang L., Poloyac S.M., Zeldin D.C., Lee C.R. The cytochrome P450 epoxygenase pathway regulates the hepatic inflammatory response in fatty liver disease. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hye Khan M.A., Schmidt J., Stavniichuk A., Imig J.D., Merk D. A dual farnesoid X receptor/soluble epoxide hydrolase modulator treats non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in mice. Biochem Pharmacol. 2019;166:212–221. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2019.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun C.C., Zhang C.Y., Duan J.X., Guan X.X., Yang H.H., Jiang H.L., Hammock B.D., Hwang S.H., Zhou Y., Guan C.X., Liu S.K., Zhang J. PTUPB ameliorates high-fat diet-induced non-alcoholic fatty liver disease via inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation in mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2020;523:1020–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.12.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris T.R., Bettaieb A., Kodani S., Dong H., Myers R., Chiamvimonvat N., Haj F.G., Hammock B.D. Inhibition of soluble epoxide hydrolase attenuates hepatic fibrosis and endoplasmic reticulum stress induced by carbon tetrachloride in mice. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2015;286:102–111. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2015.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang C.H., Zheng L., Gui L., Lin J.Y., Zhu Y.M., Deng W.S., Luo M. Soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibition with t-TUCB alleviates liver fibrosis and portal pressure in carbon tetrachloride-induced cirrhosis in rats. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2018;42:118–125. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2017.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bettaieb A., Nagata N., AbouBechara D., Chahed S., Morisseau C., Hammock B.D., Haj F.G. Soluble epoxide hydrolase deficiency or inhibition attenuates diet-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress in liver and adipose tissue. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:14189–14199. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.458414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lopez-Vicario C., Alcaraz-Quiles J., Garcia-Alonso V., Rius B., Hwang S.H., Titos E., Lopategi A., Hammock B.D., Arroyo V., Claria J. Inhibition of soluble epoxide hydrolase modulates inflammation and autophagy in obese adipose tissue and liver: role for omega-3 epoxides. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:536–541. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1422590112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bertola A., Mathews S., Ki S.H., Wang H., Gao B. Mouse model of chronic and binge ethanol feeding (the NIAAA model) Nat Protoc. 2013;8:627–637. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Postic C., Magnuson M.A. DNA excision in liver by an albumin-Cre transgene occurs progressively with age. Genesis. 2000;26:149–150. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1526-968x(200002)26:2<149::aid-gene16>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baraona E., Lieber C.S. Effects of ethanol on lipid metabolism. J Lipid Res. 1979;20:289–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.You M., Fischer M., Deeg M.A., Crabb D.W. Ethanol induces fatty acid synthesis pathways by activation of sterol regulatory element-binding protein (SREBP) J Biol Chem. 2002;277:29342–29347. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202411200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhong W., Zhao Y., Tang Y., Wei X., Shi X., Sun W., Sun X., Yin X., Sun X., Kim S., McClain C.J., Zhang X., Zhou Z. Chronic alcohol exposure stimulates adipose tissue lipolysis in mice: role of reverse triglyceride transport in the pathogenesis of alcoholic steatosis. Am J Pathol. 2012;180:998–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harris T.R., Hammock B.D. Soluble epoxide hydrolase: gene structure, expression and deletion. Gene. 2013;526:61–74. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Inceoglu B., Bettaieb A., Haj F.G., Gomes A.V., Hammock B.D. Modulation of mitochondrial dysfunction and endoplasmic reticulum stress are key mechanisms for the wide-ranging actions of epoxy fatty acids and soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibitors. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2017;133:68–78. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2017.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Quertemont E. Genetic polymorphism in ethanol metabolism: acetaldehyde contribution to alcohol abuse and alcoholism. Mol Psychiatry. 2004;9:570–581. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cederbaum A.I. Alcohol metabolism. Clin Liver Dis. 2012;16:667–685. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jiang Y., Zhang T., Kusumanchi P., Han S., Yang Z., Liangpunsakul S. Alcohol metabolizing enzymes, microsomal ethanol oxidizing system, cytochrome P450 2E1, catalase, and aldehyde dehydrogenase in alcohol-associated liver disease. Biomedicines. 2020;8:50. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines8030050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ji C., Kaplowitz N. Betaine decreases hyperhomocysteinemia, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and liver injury in alcohol-fed mice. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1488–1499. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00276-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ji C., Mehrian-Shai R., Chan C., Hsu Y.H., Kaplowitz N. Role of CHOP in hepatic apoptosis in the murine model of intragastric ethanol feeding. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:1496–1503. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000174691.03751.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ji C. New insights into the pathogenesis of alcohol-induced ER stress and liver diseases. Int J Hepatol. 2014;2014:513787. doi: 10.1155/2014/513787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu X., Green R.M. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and liver diseases. Liver Res. 2019;3:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.livres.2019.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wilfred de Alwis N.M., Day C.P. Genetics of alcoholic liver disease and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Semin Liver Dis. 2007;27:44–54. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-960170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li S., Tan H.Y., Wang N., Zhang Z.J., Lao L., Wong C.W., Feng Y. The role of oxidative stress and antioxidants in liver diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16:26087–26124. doi: 10.3390/ijms161125942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ayala A., Munoz M.F., Arguelles S. Lipid peroxidation: production, metabolism, and signaling mechanisms of malondialdehyde and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2014;2014:360438. doi: 10.1155/2014/360438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee K.S., Liu J.Y., Wagner K.M., Pakhomova S., Dong H., Morisseau C., Fu S.H., Yang J., Wang P., Ulu A., Mate C.A., Nguyen L.V., Hwang S.H., Edin M.L., Mara A.A., Wulff H., Newcomer M.E., Zeldin D.C., Hammock B.D. Optimized inhibitors of soluble epoxide hydrolase improve in vitro target residence time and in vivo efficacy. J Med Chem. 2014;57:7016–7030. doi: 10.1021/jm500694p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Deng W., Zhu Y., Lin J., Zheng L., Zhang C., Luo M. Inhibition of soluble epoxide hydrolase lowers portal hypertension in cirrhotic rats by ameliorating endothelial dysfunction and liver fibrosis. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2017;131:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2017.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mak S.K., Yu C.M., Sun W.T., He G.W., Liu X.C., Yang Q. Tetramethylpyrazine suppresses angiotensin II-induced soluble epoxide hydrolase expression in coronary endothelium via anti-ER stress mechanism. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2017;336:84–93. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2017.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Donohue T.M., Jr., Zetterman R.K., Zhang-Gouillon Z.Q., French S.W. Peptidase activities of the multicatalytic protease in rat liver after voluntary and intragastric ethanol administration. Hepatology. 1998;28:486–491. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schmelzer K.R., Kubala L., Newman J.W., Kim I.H., Eiserich J.P., Hammock B.D. Soluble epoxide hydrolase is a therapeutic target for acute inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:9772–9777. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503279102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thomson S.J., Askari A., Bishop-Bailey D. Anti-inflammatory effects of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids. Int J Vasc Med. 2012;2012:605101. doi: 10.1155/2012/605101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gao Y., Feng J., Ma K., Zhou Z., Zhu Y., Xu Q., Wang X. 8,9-Epoxyeicosatrienoic acid inhibits antibody production of B lymphocytes in mice. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Parker R., Kim S.J., Gao B. Alcohol, adipose tissue and liver disease: mechanistic links and clinical considerations. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15:50–59. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Qin X.H., Wu Z., Dong J.H., Zeng Y.N., Xiong W.C., Liu C., Wang M.Y., Zhu M.Z., Chen W.J., Zhang Y., Huang Q.Y., Zhu X.H. Liver soluble epoxide hydrolase regulates behavioral and cellular effects of chronic stress. Cell Rep. 2019;29:3223–3234 e6. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Puri P., Xu J., Vihervaara T., Katainen R., Ekroos K., Daita K., Min H.K., Joyce A., Mirshahi F., Tsukamoto H., Sanyal A.J. Alcohol produces distinct hepatic lipidome and eicosanoid signature in lean and obese. J Lipid Res. 2016;57:1017–1028. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M066175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu X., Qin Z., Liu C., Song M., Luo X., Zhao H., Qian D., Chen J., Huang L. Nox4 and soluble epoxide hydrolase synergistically mediate homocysteine-induced inflammation in vascular smooth muscle cells. Vasc Pharmacol. 2019;120:106544. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2019.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ren Q., Ma M., Yang J., Nonaka R., Yamaguchi A., Ishikawa K.I., Kobayashi K., Murayama S., Hwang S.H., Saiki S., Akamatsu W., Hattori N., Hammock B.D., Hashimoto K. Soluble epoxide hydrolase plays a key role in the pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:E5815–E5823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1802179115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhou C., Huang J., Li Q., Zhan C., He Y., Liu J., Wen Z., Wang D.W. Pharmacological inhibition of soluble epoxide hydrolase ameliorates chronic ethanol-induced cardiac fibrosis by restoring autophagic flux. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2018;42:1970–1978. doi: 10.1111/acer.13847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yamada T., Morisseau C., Maxwell J.E., Argiriadi M.A., Christianson D.W., Hammock B.D. Biochemical evidence for the involvement of tyrosine in epoxide activation during the catalytic cycle of epoxide hydrolase. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:23082–23088. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001464200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Morisseau C., Hammock B.D. Measurement of soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH) activity. Curr Protoc Toxicol. 2007 doi: 10.1002/0471140856.tx0423s33. Chapter 4:Unit 4.23, 1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ostermann A.I., Herbers J., Willenberg I., Chen R., Hwang S.H., Greite R., Morisseau C., Gueler F., Hammock B.D., Schebb N.H. Oral treatment of rodents with soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibitor 1-(1-propanoylpiperidin-4-yl)-3-[4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenyl]urea (TPPU): Resulting drug levels and modulation of oxylipin pattern. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2015;121:131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2015.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu J.Y., Lin Y.P., Qiu H., Morisseau C., Rose T.E., Hwang S.H., Chiamvimonvat N., Hammock B.D. Substituted phenyl groups improve the pharmacokinetic profile and anti-inflammatory effect of urea-based soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibitors in murine models. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2013;48:619–627. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2012.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yang J., Schmelzer K., Georgi K., Hammock B.D. Quantitative profiling method for oxylipin metabolome by liquid chromatography electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2009;81:8085–8093. doi: 10.1021/ac901282n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li W.C., Ralphs K.L., Tosh D. Isolation and culture of adult mouse hepatocytes. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;633:185–196. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-019-5_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hsu M.F., Koike S., Mello A., Nagy L.E., Haj F.G. Hepatic protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B disruption and pharmacological inhibition attenuate ethanol-induced oxidative stress and ameliorate alcoholic liver disease in mice. Redox Biol. 2020;36:101658. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2020.101658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.