Abstract

Purpose

Traditional infant swaddling or binding with hips and knees extended is a known risk factor for Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip (DDH), while ‘hip-safe swaddling’ with hips and knees flexed is believed to eliminate this risk. We conducted a survey to determine the prevalent practices for infant swaddling in India; why mothers practice swaddling and who teaches them; and whether Paediatricians, nurses and caregivers are aware of hip-safe swaddling.

Methods

Anonymous one-time surveys were conducted in three groups–Paediatricians, Nurses and caregivers – at a tertiary-care, urban based, paediatric and maternity hospital.

Results

Forty-five paediatricians, 219 nurses and 100 caregivers were surveyed. Ninety percent caregivers practiced traditional swaddling, for on average 10.2 hours a day, starting soon after birth, up to 4.2 months of life. Traditional swaddling was advocated by 99% nurses and 53% Paediatricians. Reasons for swaddling included sleep, warmth and the misbelief that the child’s legs would remain bowed if not bound straight; contrarily few mothers (8%) avoided swaddling out of superstition. Mothers learnt swaddling mainly from relatives (94%) and nurses (64%). Most nurses (70%) had learnt the practice during nursing training. Only 6.6% Paediatricians, 4% caregivers and 0% nurses were aware of ‘hip-safe swaddling’.

Conclusion

Traditional swaddling of infants is a practice deeply rooted in India, born out of misbeliefs, and propagated by lack of awareness. Training in hip-safe swaddling targeted at nurses and Paediatricians would be an effective initial step in creating awareness among mothers and changing their practices.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s43465-020-00188-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Swaddling, Developmental dysplasia of the hip, Risk factors, Traditional methods, Hip-safe, Survey

Introduction

The practice of binding or wrapping an infant in a cloth, known as ‘swaddling’ has been in practice the world over for centuries [1]. Swaddling is believed to comfort an infant by mimicking the snugness of the womb [2]. The traditional technique of keeping an infant tightly restrained, sometimes using a cradleboard, largely declined in the western world in the eighteenth century [1]. In deeply traditional societies like in India, however, the practice is still common.

Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) is a common musculoskeletal congenital anomaly occurring in newborns. Multiple epidemiological studies have shown that the incidence of DDH is higher in cultures where traditional swaddling is prevalent [3–8] and the association has been proven in animal studies as well [4, 9–11]. Tight lower extremity swaddling is now recognized as an important risk factor for DDH [12, 13]. Numerous Paediatric [14] and Orthopaedic [15, 16] societies around the world promote ‘hip-safe swaddling’ in place of the traditional method, for the prevention of DDH. In Japan, a national campaign to eliminate infant swaddling with hips and knees in extension was initiated in 1975, which led to a remarkable decline in the incidence of DDH from 1.1 to 3.5% prior to the campaign, to less than 0.2% after it [17, 18].

DDH is an important cause for morbidity in childhood, and also one of the leading causes of hip osteoarthritis in adults [19]. In India, the incidence of DDH is estimated to be 1.0–9.2 per 1000 births [20]. There have not been any studies determining the prevalent attitudes and practices towards swaddling of infants among caregivers and healthcare workers, specifically in relation to DDH. However, anecdotal observations in maternity and neonatal wards suggest that traditional swaddling with the hips in adduction and extension is very common. If we assume that a proportion of the cases of DDH is related to incorrect swaddling, a change in the swaddling technique should result in a decrease in the incidence of DDH in countries such as India where traditional swaddling is so common. With this in mind, we conducted a survey to determine: (1) What are the current practices for swaddling of infants in India? (2) Why do mothers practice swaddling and who teaches them to do it? and (3) Are doctors, nurses and caregivers aware of the association between swaddling and hip dysplasia?

Materials and Methods

After obtaining approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee of our institution, we conducted a descriptive, cross-sectional survey to determine the knowledge, attitudes and practices related to swaddling, of three different groups of individuals at our institution. Our institution is a tertiary-care, urban based, paediatric hospital which, along with its sister maternity hospital, caters to a large volume of patients from the middle and lower socioeconomic classes. The survey was administered to (1) Paediatricians (including full-time faculty and residents), (2) Nursing staff of all cadres involved in the care of newborns, and (3) Caregivers of infants less than 1 year of age. A separate survey was designed for each group and questions were developed after a review of literature and consensus from a focused group of experts. In addition to demographic questions, the surveys comprised of multiple-choice questions and short answer questions related to knowledge, attitudes and practices of the respondents (Supplementary Appendix 1). For Paediatricians, the survey was administered during a monthly departmental clinical meeting. Nursing staff answered the survey questionnaire during their weekly training sessions. Caregivers were interviewed at the well-baby & vaccination out-patient clinic of our hospital.

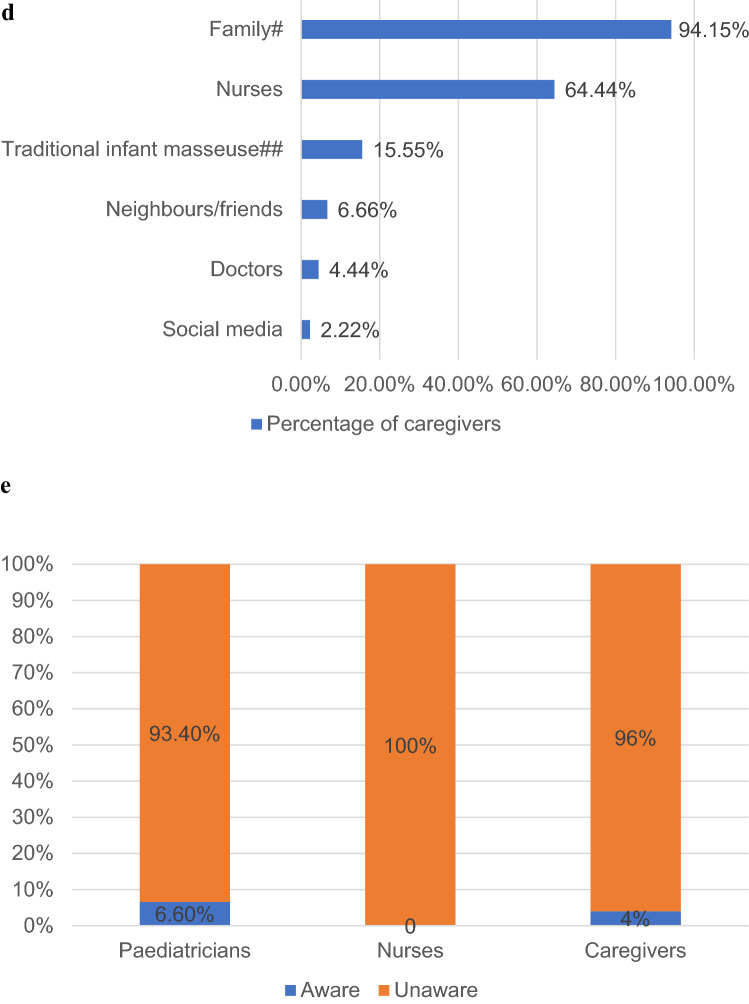

Participants were initially shown a photograph of an infant swaddled in the traditional manner (Fig. 1a) and in the ‘hip-safe’ manner (Fig. 1b), and asked what they would call the practice. Questions were asked to determine the type of swaddling taught/used, frequency of swaddling, and age up to which it was regularly done. Paediatricians were additionally questioned regarding their knowledge of the risk factors and examination findings in DDH, and about their protocols for referring infants to Orthopaedic surgeons for assessment. Nurses and caregivers were particularly questioned about where they had learnt about swaddling and their reasons for practicing it. All three groups were asked specifically about their awareness of ‘hip-safe swaddling’.

Fig. 1.

Photographs of swaddled infants a Traditional straight-leg swaddling. Note how the lower limbs are tied tightly together, allowing no room for movement. b An infant swaddled in the ‘hip-safe’ manner, demonstrating how there is sufficient room for the infant to flex and abduct the hips

All the surveys were administered by the principal investigator. Nurses and Paediatricians were given anonymized paper survey forms to fill, whereas caregivers were individually interviewed by the investigator. Data from the filled survey forms were transferred to a computer spreadsheet and analyzed using Microsoft Excel (version 16.35) software.

Results

All participants consented to complete the survey. A total of 45 Paediatricians, 219 nurses and 100 caregivers were surveyed over a period of three months from January to March 2020. For the purpose of our survey, ‘traditional swaddling’ was defined as any technique that involved binding the infants’ lower limbs with the hips extended and adducted. ‘Hip-safe swaddling’ was defined as a technique of loosely wrapping the lower limbs allowing the infants’ hips to fall into the natural position of flexion and abduction. ‘Regular swaddling’ was taken to be swaddling for at least 2 h every day. For many questions, participants were allowed to choose more than one option as their response. Hence the percentages given do not total to 100% in these questions.

Paediatricians

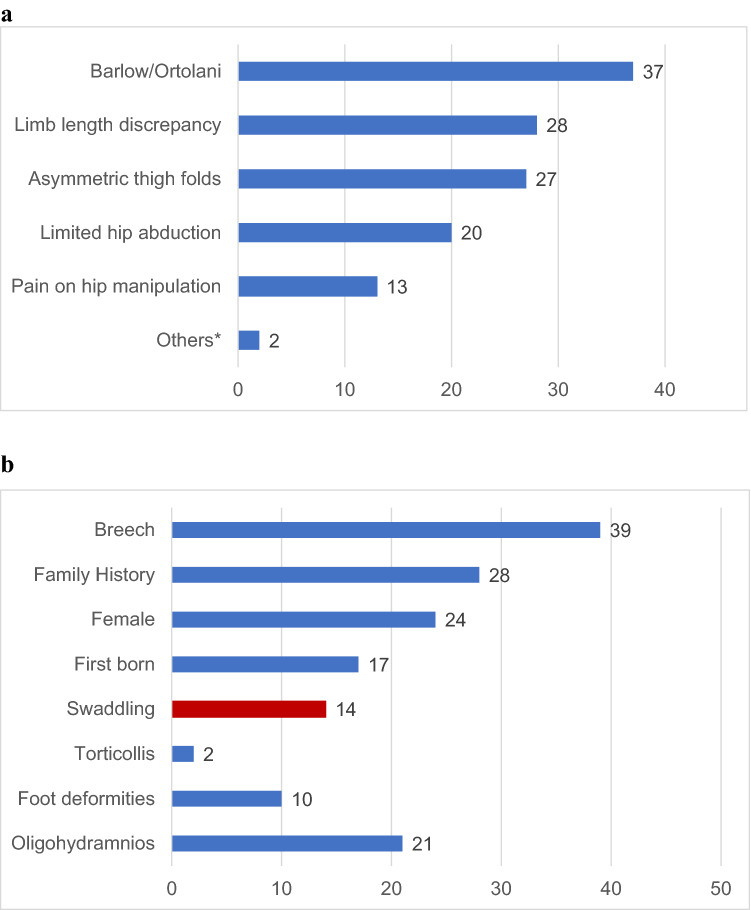

Twelve full-time faculty and 33 trainees (including junior residents and fellows) answered the survey. Ninety-three percent of paediatricians routinely examined infants for hip instability. The majority of these (86%) did so only at the child’s first visit and only six out of 45 routinely re-examined the hips at subsequent follow-ups. Paediatricians were asked to list the clinical findings that they believed to be indicative of hip instability, and to name the risk factors for DDH (Fig. 2). Of note, less than half checked for limitation of hip abduction, and 29% erroneously believed that pain on hip manipulation was a sign of DDH. Only 31% were aware that swaddling was a risk factor for DDH. Twenty-six out of 45 paediatricians (57.7%) routinely educated mothers about swaddling their babies. Among those who did, 92% taught mothers the traditional swaddling technique with the hips abducted and extended whereas two advised swaddling of upper limbs alone, with the lower limbs kept free. Only three of the 45 Paediatricians surveyed were aware of ‘hip-safe swaddling’.

Fig. 2.

Paediatricians' (n = 45) responses. a Regarding clinical features of DDH (*Others – Asymmetric femoral pulse). b Regarding risk factors for DDH

Nursing staff

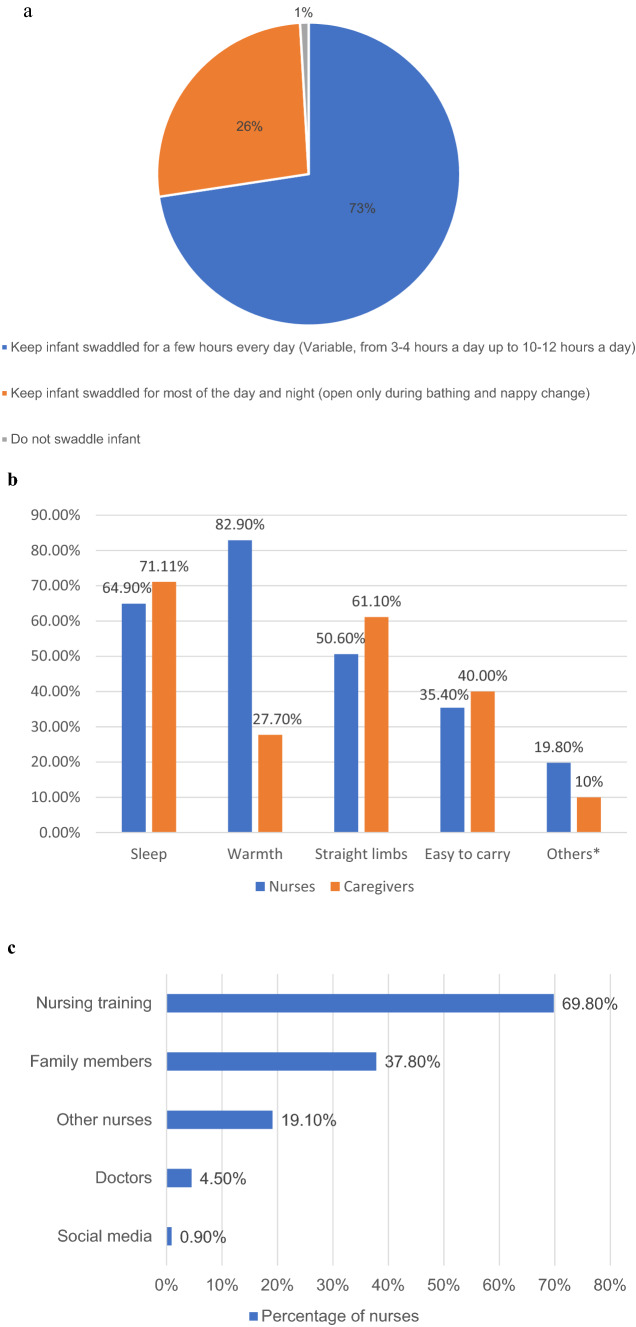

We interviewed 219 nurses, with clinical experience averaging 8.2 years (range six months – 34 years). Twenty-one of these were senior nurses, involved in administrative and teaching duties. Besides the terms ‘wrapping’ and ‘draping’, a number of nurses used the term ‘mummification’ to describe swaddling. All nurses routinely counselled mothers about the practice of swaddling, with 99% of them actively encouraging mothers to swaddle their infants. Advice given about the duration of wrapping was variable (Fig. 3a). The technique of swaddling taught to mothers, in all cases, was the traditional method, with the lower limbs bundled in extension and adduction at the hips. All nurses advised mothers to start swaddling immediately after birth. The upper age limit advised was variable, from three months up to 12 months. Figure 3b lists the reasons given by the nurses for infant swaddling. None of the nurses interviewed were aware of the risk of hip dysplasia caused by swaddling, and none had heard of the concept of ‘hip-safe swaddling’. We asked nurses where they had learnt about swaddling (Fig. 3c). It was surprising to note that most nurses (69.8%) had learnt about ‘traditional swaddling’ as a part of their nursing training.

Fig. 3.

Attitudes and practices regarding swaddling among nurses and caregivers, and knowledge of hip-safe swaddling in all groups. a Advice given by nurses regarding the duration of swaddling. b Commonly given reasons for swaddling among nurses and caregivers (*Others: Among nurses, pacifying a crying infant was given as a cause. Among caregivers, the cause cited in others was ‘tradition’). c Where nurses learnt about swaddling. d Where caregivers learnt about swaddling (# In family: older generation (mothers, mothers-in law) – 68.88%, same generation (sisters, sisters-in-law) – 25.27%. ## ‘Traditional infant masseuse’, colloquially called ‘Maalish bai’, are usually women without any medical training, who are employed by families to massage their infants. Besides massage, they often also advise mothers about traditional customs and practices in childcare.). e Awareness of 'hip-safe swaddling' among the three surveyed groups

Caregivers

The majority of caregivers interviewed were mothers; only in four cases, it was a grandparent. Demographics, attitudes and practices of caregivers towards swaddling are summarized in Table 1. Notably, 90% of caregivers swaddled their infants, and all those who practiced it did so in the traditional manner. The reasons given by the mothers for swaddling their infants are listed in Fig. 3b. More than half the mothers (and nurses) believed that swaddling was essential to correct the ‘abnormal shape’ of their infant’s legs. Nine mothers emphasized that they swaddled their infant purely because it was the tradition. Two out of the ten mothers who did not swaddle their infants did so because the child had undergone surgery. The remaining eight said that they had been advised specifically against the practice by the elders in their families. Interestingly, all those who gave this reason were from the northern states of the country, where cultural superstitions forbade mothers from swaddling their children, believing it to be a bad omen to keep the infant restrained. Furthermore, some of the mothers from cultural backgrounds that didn’t believe in swaddling actually picked up the traditional wrapping after having learnt it from nurses in the hospital and women in their locality. Thus, it seems that the practice of swaddling is deeply rooted in the culture of some regions of India, whereas in other parts of the country, families prefer to keep their infants unbound. Finally, we asked mothers who had taught them to swaddle their infants (Fig. 3d). The most common sources of information on swaddling were the women in their family and nurses.

Table 1.

Demographics of caregivers interviewed and their practices regarding swaddling

| Mothers’ age | Mean 30.7 years (range 22–48 years) | |

| Mothers’ occupation | Working women: 49 | |

| Housewives: 51 | ||

| Highest educational level of mothers | Graduate: 60 | |

| College: 14 | ||

| High school: 19 | ||

| Primary school: 5 | ||

| Illiterate: 2 | ||

| Number of children | One | 66 |

| Two | 30 | |

| Three | 4 | |

| Number of mothers regularly swaddling their youngest infant | 90/100 (90%) | |

| Number of mothers who had regularly swaddled their previous infant(s) | 27/34 (79%) | |

| Technique of swaddling practiced | Both upper and lower limbs | 76/90 (84.3%) |

| Lower limbs only | 14/90 (15.5%) | |

| Hip-safe swaddling | None | |

| Duration of swaddling (out of 24 h) | Average | 10.2 h |

| Minimum | Two to four hoursa (22%) | |

| Maximum | 18–20 h (19.6%) | |

| Full night swaddling | 32/90 (35.2%) | |

| Age at start of swaddling | Immediately after birthb (78.4%) | |

| Age at discontinuing swaddling | 4.2 months (range 1–9.5 months) | |

aSwaddling for two to four hours only – On enquiry, we found that this was done only once in the day after the child had his/her massage and had been bathed

bIn the rest (21.6%), delay in starting swaddling, usually for a few weeks after birth, was reported in cases where the infant had been unwell and admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) soon after delivery

Hip-safe Swaddling

In our study, only 6.6% of paediatricians, 4% of caregivers and 0% of nurses had ever heard of ‘hip-safe swaddling’ (Fig. 3e).

Discussion

The practice of swaddling is not without advantages. Systematic reviews of the literature on swaddling [21, 22] describe benefits including improved sleep, better thermoregulation, reduction in the incidence of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), faster recovery from painful stimuli and reduced crying in infants with cerebral insults. However, swaddling can be harmful when done incorrectly [21, 22]; the hazards include overheating, increased respiratory infections when the chest is swaddled too tightly, sub-clinical Vitamin D deficiency, and an increased incidence of SIDS when swaddled infants are laid to sleep in the prone position. From the Orthopaedic standpoint, the chief concern is the association between swaddling and DDH [3–11].

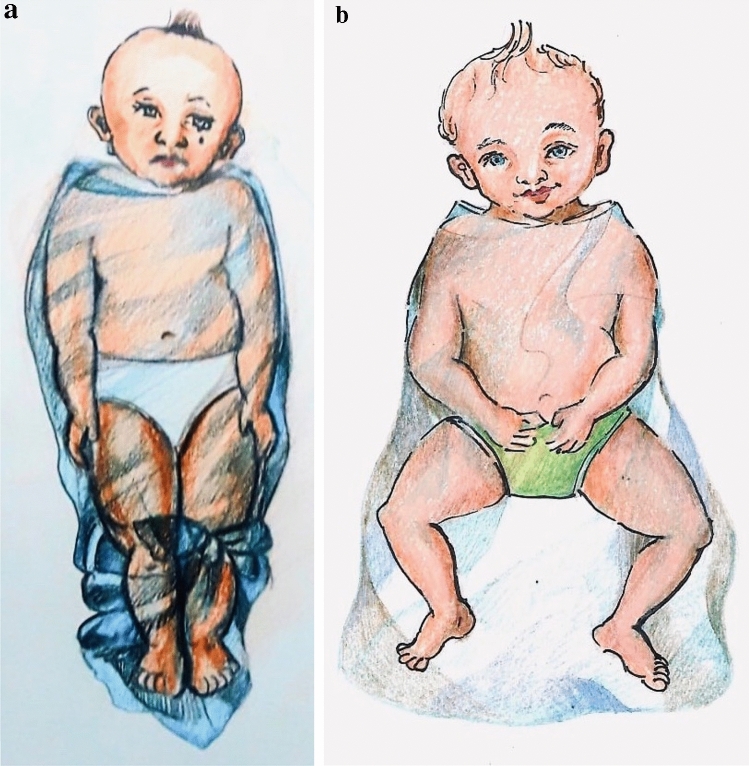

All infants normally have flexion contractures at the hips and knees for several months after birth on account of intrauterine positioning [23, 24]. Forcing their hips and knees into extension increases the tension in the hamstrings and iliopsoas muscles, causing them to pull the femur upwards [25]. This places pressure on the soft cartilage of the hip joint, particularly in infants with underlying laxity or instability. It has been established through ultrasound studies that ~ 15% of all newborns have unstable hip joints [26]. The instability usually resolves without any treatment within a few weeks [26, 27]. However, when such infants are positioned for prolonged periods with their hips fixed in extension and adduction, the instability can worsen to subluxation and frank dislocation. This hypothesis has been supported by multiple clinical studies [5, 12, 17, 28] and experimental animal research [4, 9, 11] as well. It is crucial to note that this risk occurs only with traditional swaddling techniques (straight-leg swaddling), which force the infant’s hips and knees into extension (Fig. 4a). ‘Hip-safe swaddling’, on the other hand, does not increase the risk of DDH [14, 16, 29]. For normal development of the hip joints to occur, the lower limbs should be allowed to move upwards and outwards at the hips. This is the natural posture that is assumed by infants due to flexion and external rotation contractures at the hips and flexion contractures at the knees that are present in the first few months of life [23, 24]. This so-called ‘froggy-leg position’ allows for normal hip joint development. Hence, when swaddling infants, the hips should be kept in slight flexion and abduction, the knees should be slightly flexed, and there should be ample room within the swaddle for the infants to move their legs (Fig. 4b). The International Hip Dysplasia Institute (IHDI) has described in detail the techniques for hip-safe swaddling [30].

Fig. 4.

Illustrations showing positions of the lower limbs in different types of swaddling. a Illustration of traditional swaddling: note that the hips are adducted and extended, knees are extended and both lower limbs are tied tightly together. b Illustration of hip-safe swaddling: note that the wrapping around the lower limbs is wide, allowing the hips to fall naturally into abduction and external rotation

In view of all the evidence showing the causal relation between traditional swaddling and hip dysplasia, and learning from the experience of cultures like the Navajo Indians [6, 28] and the Japanese [17, 18], it would be reasonable to assume that the incidence of DDH in Indian children could be decreased if mothers practiced ‘hip-safe swaddling’. To encourage this, we needed to determine what are the currently prevalent swaddling practices in India; why do mothers swaddle their infants and who teaches them to do it; and what is the baseline awareness about the association between swaddling and DDH among the caregivers and healthcare providers in India. Our study has answered these questions to a large extent.

‘Traditional swaddling’, with the hips adducted & extended and the knees in extension, is practiced by the majority of mothers seen at our institution. Ninety percent of the mothers interviewed swaddled their infants for 10.2 h on average every day, for the first 4.2 months of life, starting immediately after birth. While there are no clinical studies that have determined the quantitative relationship between the duration and timing of swaddling and the occurrence of DDH, experimental animal research has shown that early swaddling (started in the first few days of life) and prolonged swaddling (for a longer duration after birth) are both associated with a higher incidence of hip dysplasia [9]. Early and prolonged swaddling are also associated with more severe hip dislocations, as opposed to late swaddling (started some days after birth) which is associated with hip subluxations [9]. Hence, the swaddling practices of Indian mothers appear to be consistent with those that have been shown to produce hip dysplasia.

The most common reasons given by caregivers for swaddling their infants are, to help the infants sleep, to keep them warm, and to make them easier to carry. All this can be achieved by hip-safe swaddling too. However, mothers have traditionally learnt to keep their infants’ lower limbs bundled in tight adduction and extension. This appears to come from the misguided belief that the naturally flexed attitude of an infant’s limbs is abnormal. More than half of the mothers and nurses interviewed believed that if they did not tie an infant’s limbs straight, the baby would grow up to have bowed legs. Studies of joint motion in newborns have shown that hip flexion & external rotation contractures of up to 30° and knee flexion contractures of up to 35° are often present in otherwise healthy newborn infants [23, 24]. These improve as the child grows, with full knee extension being obtained by three months of age, but hip flexion and external rotation contractures persist through infancy and gradually disappear in the second year of life as the child begins to walk [23]. Lack of awareness of this fact in mothers and even nurses is an important reason for the widespread practice of straight-leg swaddling in our study.

The source of age-old traditional swaddling can be traced back to the teachings of the older generations. More than two-thirds of the mothers interviewed were advised about swaddling by their own mothers or mothers-in law, and even their grandmothers. It may be exceedingly difficult to change the beliefs of these matriarchs. However, an important finding from our study was that an almost equal number of mothers had learnt the traditional swaddling technique from nurses. Postpartum wards typically have rows of newborns kept tightly swaddled by nursing staff, and many new mothers first learn the practice of swaddling by observing these nurses. Most of the nurses in our survey routinely advised mothers about swaddling infants in the traditional manner, and most of them stated that they had learnt this technique during nursing training. It is not surprising then, that traditional swaddling is so commonly practiced by our survey population. A survey among child health nurses (CHN) in Australia [31] discovered a wide variation in their knowledge, attitudes and practice with respect to infant swaddling as a measure to reduce SIDS. Despite Australia having developed a position statement to promote safe infant sleeping practices at the time of the survey, the authors found that the CHNs had poor awareness of it. Subsequent to their study, evidence-based practice guidelines were developed specifically for CHNs in Australia, to promote consistency in parent education so as to reduce the risk of SIDS. In India too, nurses are the primary sources of advice and education for parents. Inclusion of guidelines on hip-safe swaddling in the training of nurses would be the most effective way of getting this knowledge to mothers, thus effecting a reduction in the incidence of DDH in our population.

Despite the abundance of literature [5–13] and position statements by various international organizations [14, 15] regarding swaddling, we found that the majority of Paediatricians and nurses from our institution were unaware of the association between swaddling and hip dysplasia. In our study, only 6.6% of Paediatricians and 0% of nurses had ever heard of ‘hip-safe swaddling’. In a survey of Paediatricians in the USA in 2018 [32], only 37% of the 49 surveyed were aware of the IHDI recommendations for hip-safe swaddling and just 24% routinely counselled parents about the risk of hip dysplasia with traditional swaddling. This was despite the fact that the American Academy of Paediatrics (AAP) had issued specific guidelines in 2016 [14] identifying traditional swaddling to be a risk factor for DDH and advocating ‘hip-safe swaddling’ as a means of minimizing the risk. In India, there is no national policy with regards to DDH or swaddling, and hip-safe swaddling is not part of the curriculum during the training of Paediatricians and nurses. It is no wonder then that we found such a lack of awareness regarding the association between swaddling and hip dysplasia among the healthcare workers at our institution. Surprisingly, 4% of caregivers in our study were aware of the concept of hip-safe swaddling, despite there being no concerted effort from the Government or private healthcare sector in creating awareness on the risks & benefits of swaddling.

The recall bias that is inherent in all surveys is an obvious limitation of our study. We surveyed Paediatricians and nurses from a single institution, hence they may not be representative of the healthcare workers as a whole. Particularly among Paediatricians, most of the participants were trainees; the knowledge levels and attitudes of practitioners with many years of experience could differ from those that we have found. However, this does highlight the fact that education about safe-swaddling practices should start early, preferably during medical school itself. Among the caregivers interviewed, the majority were from lower and middle socioeconomic classes, and almost all came from urban localities. It is very likely that the practice of tight lower extremity swaddling is even more common in smaller towns and villages, where the influence of the traditional midwives and child masseuses is probably much more. Finally, most caregivers we interviewed were from one particular state of the country. India is a heterogenous country, with varying traditions and practices across different regions & socioeconomic classes, and hence, such surveys may need to be replicated in other parts of the country. We believe that such studies would be useful in many other countries as well, where traditional swaddling practices are likely to still be followed.

The lack of awareness among the general public, coupled wih the incorrect advice given by nurses and at times even doctors, may be the reason why straight leg swaddling is so common in India. If this practice is to change, we need to raise awareness on the issue. A recent ultrasound-based study in a relatively small community in Qatar [8] found that the incidence of acetabular dysplasia among high-risk infants could be reduced from 20% to 6% within a few months of raising public awareness about swaddling. We believe that a similar campaign in India could considerably reduce the incidence of DDH in our population. There is already a programme being implemented in the country which could be used to disseminate information about swaddling and DDH. The ‘Rashtriya Bal Swasthya Karyakram’ (RBSK) scheme or ‘National Child Health Programme’ [33] was launched in February 2013 under the National Health Mission, Government of India, with the aim of early identification and early intervention for important health problems affecting children from birth to 18 years. Under this scheme, DDH is one of the birth defects to be screened for by various health workers including Auxiliary Nurse Midwives (ANM), Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHA), Anganwadi Workers (AWW) and medical officers. Besides being trained to identify the risk factors and clinical features of DDH, these health workers must also be taught the importance of hip-safe swaddling, so that this information can be passed on to the mothers with whom they interact. Just as nurses are an important source of child-care advice for mothers in urban areas, as shown by our survey, so too in rural areas, the ASHAs, ANMs and AWWs have a great rapport with mothers and can help to promote hip-safe swaddling among the masses.

We propose various measures that may be adopted at Institutional and Government levels to create awareness about hip-safe swaddling in India (Table 2).

Table 2.

Proposed strategies to create awareness about swaddling and hip dysplasia

| Institutional level | Governmental level |

|---|---|

|

Official institutional policy regarding swaddling to be communicated with all departments involved in the care of infants Regular seminars for practicing nurses and Paediatricians to reinforce the importance of hip-safe swaddling Inclusion of risk factors and clinical features of DDH as well as hip-safe swaddling in the curriculum for Paediatrics residents and fellows Training of mothers on hip-safe swaddling during well baby/vaccination clinics Informative posters about hip-safe swaddling to be displayed in all outpatient clinics and wards Liaison between medical associations such as the Indian Academy of Paediatrics (IAP) and Paediatric Orthopaedic Society of India (POSI), to develop position statements on swaddling and DDH, to be disseminated among their members through their official journals and websites |

Inclusion of hip-safe swaddling in the curriculum for medical trainees Inclusion of hip-safe swaddling in the curriculum for nursing Training of Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHA), Auxiliary Nurse Midwives (ANM) and Anganwadi Workers (AWW) about hip-safe swaddling Use of media like newspapers and television to raise awareness among the public in general |

Conclusion

Swaddling in India appears to be a practice deeply rooted in tradition, born out of certain misbeliefs, and propagated by a lack of awareness. Training in hip-safe swaddling targeted at nurses and Paediatricians would be an effective initial step in creating awareness among mothers and changing their practices.

Patient Declaration Statement

“The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.”

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Administration of ‘Wadia Hospitals’ for granting us permission to conduct this survey. We would also like to thank the doctors and nurses of ‘Bai Jerbai Wadia Hospital for Children’ and ‘Nowrosjee Wadia Maternity Hospital’, as well as the caregivers of infants treated at these hospitals for participating in the survey. We thank Mr. Darrell J. D’souza for illustrating Fig. 4 a,b.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Deepika Pinto, Rujuta Mehta and Alaric Aroojis. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Deepika Pinto and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study has no funding support.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics standard statement

Approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee—Bai Jerbai Wadia Hospital for Children.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. The authors affirm that participants provided informed consent for the publication of the images in Fig. 1a and b.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Deepika A. Pinto, Email: deepupinto@gmail.com

Alaric Aroojis, Email: aaroojis@gmail.com.

Rujuta Mehta, Email: rujutabos@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Lipton EL, Steinschneider A, Richmond JB. Swaddling, a Child Care Practice: Historical, Cultural and Experimental Observations. Pediatrics. 1965;35(3):521–567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karp H. The Happiest Baby on the Block. New York: Bantam; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Record RG, Edwards JH. Environmental Influences Related to the Aetiology of Congenital Dislocation of the Hip. Journal of Epidemiology Community Heal. 1958;12(1):8–22. doi: 10.1136/jech.12.1.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salter RB. Etiology, pathogenesis and possible prevention of congenital dislocation of the hip. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 1968;98(20):933–945. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kutlu A, Memik R, Mutlu M, Kutlu R, Arslan A. Congenital Dislocation of the Hip and Its Relation to Swaddling Used in Turkey. Journal of Pediatric Orthopedics. 1992;12(5):598–602. doi: 10.1097/01241398-199209000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rabin D, Bernett C, Arnold W, Freiberger R, Brooks G. Untreated congenital hip disease: A study of the epidemiology, natural history, and social aspects of the disease in a Navajo population. American Journal Public Health Nations Health. 1965;55(2):1–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abd el-Kader SM. Mehad the Saudi tradition of infant wrapping as a possible aetiological factor in congenital dislocation of the hip. Journal of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburg. 1989;34(2):85–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chaarani MW, Al Mahmeid MS, Salman AM. Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip before and after Increasing Community Awareness of the Harmful Effects of Swaddling. Qatar Medical Journal. 2002;11(1):40–43. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang E, Liu T, Li J, Edmonds EW, Zhao Q, Zhang L, et al. Does swaddling influence developmental dysplasia of the hip? An experimental study of the traditional straight-leg swaddling model in neonatal rats. Journal of Bone Joint Surgery. 2012;94(12):1071–1077. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.00720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asplund S, Hjelmstedt Å. Experimentally induced hip dislocation dislocation in vitro and in vivo. Acta Orthopaedica Scandinavica. 1983;54(sup199):1–57. doi: 10.3109/17453678309154168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilkinson JA. Prime factors in the etiology of Congenital Dislocation of the Hip. Journal of Bone Joint Surgery British. 1963;45(2):268–283. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.45B2.268. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mahan ST, Kasser JR. Does swaddling influence developmental dysplasia of the hip? Pediatrics. 2008;121(1):177–178. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mulpuri K, Schaeffer EK, Andrade J, Sankar WN, Williams N, Matheney TH, et al. What Risk Factors and Characteristics Are Associated With Late-presenting Dislocations of the Hip in Infants? Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2016;474(5):1131–1137. doi: 10.1007/s11999-015-4668-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shaw BA, Segal LS, Otsuka NY, Schwend RM, Ganley TJ, Herman MJ, et al. Evaluation and referral for developmental dysplasia of the hip in infants. Pediatrics. 2016;138(6):e20163107. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-3107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Position Statement: Swaddling and Developmental Hip Dysplasia. https://aaos.org/contentassets/1cd7f41417ec4dd4b5c4c48532183b96/1186-swaddling-and-developmental-hip-dysplasia1.pdf. Accessed 15th April 2020

- 16.International Hip Dysplasia Institute. Swaddling: IHDI Position Statement. https://hipdysplasia.org/swaddling-statement Accessed 15th April 2020

- 17.Yamamuro T, Ishida K. Recent advances in the prevention, early diagnosis, and treatment of congenital dislocation of the hip in Japan. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 1984;184:34–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ishida K. Prevention of the development of the typical dislocation of the hip. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 1977;126:167–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Furnes O, Lie SA, Espehaug B, Vollset SE, Engesaeter LB, Havelin LI. Hip disease and the prognosis of total hip replacements. Journal of Bone Joint Surgery. 2001;83(4):579–586. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.83B4.0830579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agarwal A, Gupta N. Risk factors and diagnosis of developmental dysplasia of hip in children. Journal of Clinical Orthopaedics and Trauma. 2012;3(1):10–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Sleuwen BE, Engelberts AC, Boere-Boonekamp MM, Kuis W, Schulpen TWJ, L’Hoir MP. Swaddling: A systematic review. Pediatrics. 2007;120(4):e1097–e1106. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nelson AM. Risks and Benefits of Swaddling Healthy Infants: An Integrative Review. MCN American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing. 2017;42(4):216–225. doi: 10.1097/NMC.0000000000000344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoffer MM, Joint motion limitation in newborns Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 1980;148:94–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coon V, Donato G, Houser C, Bleck EE. Normal ranges of hip motion in infants six weeks, three months and six months of age. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 1975;110:256–260. doi: 10.1097/00003086-197507000-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suzuki S, Yamamuro T. The mechanical cause of congenital dislocation of the hip joint: Dynamic ultrasound study of 5 cases. Acta Orthopaedica Scandinavica. 1993;64(3):303–304. doi: 10.3109/17453679308993631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosendahl K, Markestad T, Lie RT. Ultrasound screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip in the neonate: The effect on treatment rate and prevalence of late cases. Pediatrics. 1994;94(1):47–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kocher MS. Ultrasonographic screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip: an epidemiologic analysis (Part I) American Journal of Orthopedics (Belle Mead NJ) 2000;29(12):929–933. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coleman SS. Congenital dysplasia of the hip in the Navajo infant. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 1968;56:179–193. doi: 10.1097/00003086-196801000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karp HN. Safe Swaddling and Healthy Hips: Don’t Toss the Baby out With the Bathwater. Pediatrics. 2008;121(5):1075–1076. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.International Hip Dysplasia Institute. Hip-healthy swaddling. https://hipdysplasia.org/developmental-dysplasia-of-the-hip/hip-healthy-swaddling Accessed 15th April 2020

- 31.Young J, Gore R, Gorman B, Watson K. Wrapping and swaddling infants: Child health nurses’ knowledge, attitudes and practice. Neonatal, Paediatric and Child Health Nursing. 2013;16:2–11. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goldstein RY. Less Than Half of Pediatricians Educate Parents of Newborns on Risks and Benefits of Swaddling. Acad Journal of Pediatrics Neonatology. 2018;6(5):0–3. doi: 10.19080/AJPN.2018.06.555756. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ministry of Health & Family Welfare Government of India. Operational Guidelines: Rashtriya Bal Swasthya Karyakram (RBSK). https://nhm.gov.in/images/pdf/programmes/RBSK/Operational_Guidelines/Operational Guidelines_RBSK.pdf Accessed 15th April 2020

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.