Abstract

Trazodone (TRZ) is a commonly prescribed antidepressant with significant off-label use for insomnia. A recent drug screening revealed that TRZ interferes with sterol biosynthesis, causing elevated levels of sterol precursor 7-dehydrocholesterol (7-DHC). Recognizing the well-documented, disruptive effect of 7-DHC on brain development, we designed a study to analyze TRZ effects during pregnancy. Utilizing an in vivo model and human biomaterial, our studies were designed to also account for drug interactions with maternal or offspring Dhcr7 genotype. In a maternal exposure model, we found that TRZ treatment increased 7-DHC and decreased desmosterol levels in brain tissue in newborn pups. We also observed interactions between Dhcr7 mutations and maternal TRZ exposure, giving rise to the most elevated toxic oxysterols in brains of Dhcr7+/− pups with maternal TRZ exposure, independently of the maternal Dhcr7 genotype. Therefore, TRZ use during pregnancy might be a risk factor for in utero development of a neurodevelopmental disorder, especially when the unborn child is of DHCR7+/− genotype. The effects of TRZ on 7-DHC was corroborated in human serum samples. We analyzed sterols and TRZ levels in individuals with TRZ prescriptions and found that circulating TRZ levels correlated highly with 7-DHC. The abundance of off-label use and high prescription rates of TRZ might represent a risk for the development of DHCR7 heterozygous fetuses. Thus, TRZ use during pregnancy is potentially a serious public health concern.

Subject terms: Molecular neuroscience, Neuroscience

Introduction

The inhibition of 7-dehydrocholesterol reductase (DHCR7) enzyme, a key enzyme in the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway, leads to elevated levels of 7-dehydrocholesterol (7-DHC) and decreased levels of desmosterol and cholesterol1. Inhibition of DHCR7 is a side effect of multiple widely-used pharmaceuticals2–4. These compounds produce changes in sterol profiles that mimic biochemical changes arising from genetic mutations in humans (Supplemental Fig. 1)5,6. One of these compounds is trazodone (TRZ) hydrochloride (marketed under brand names Trazodone, Desyrel, Donaren, Molipaxin, Oleptro, Trazorel, and Trittico).

Approved by the FDA in 1981, TRZ is a potent 5-HT2A and α1-adrenergic receptor antagonist and weak serotonin reuptake inhibitor7. TRZ and its major active metabolite meta-chlorophenylpiperazine (m-CPP) also bind to a variety of other receptors. The primary use of TRZ is the treatment of depression. However, TRZ has been extensively prescribed for off-label use as a treatment for insomnia8,9. In fact, the off-label use of TRZ for insomnia has surpassed its usage as an antidepressant8. Non-approved uses include treatment and/or self-treatment of opioid withdrawal symptom10, complex regional pain syndrome11, obsessive–compulsive disorder12, alcohol withdrawal13–15, schizophrenia16, dementia in Alzheimer’s disease, eating disorders, fibromyalgia, and erectile dysfunction17. Considering this extensive off-label use, it is not surprising that for the period from 2007 to 2017 there were a total of 226,057,791 TRZ prescriptions (Supplemental Fig. 2)18. The total number of TRZ prescriptions is almost twice as high as the number of oxycodone prescriptions.

Normal cholesterol homeostasis is essential for brain development, health, and life19. Genetic disruptions of the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway lead to various syndromes, including Smith–Lemli–Opitz syndrome, desmosterolosis, and chondrodysplasia punctata X-linked 2 (CDPX2)5. Our recent study examined levels of cholesterol and cholesterol precursors, desmosterol, and 7-DHC in blood samples of 123 psychiatric patients treated with various antipsychotic and antidepressant drugs and 85 healthy controls20. We found markedly increased circulating 7-DHC levels in patients treated with TRZ, suggesting that TRZ is a strong inhibitor of DHCR721.

Knowing the well-documented, disruptive effect of 7-DHC on brain development22–24, and the widespread off-label use of TRZ in the human population, we designed a study to analyze TRZ effects during pregnancy using an in vivo model as well as a human biomaterial. Our studies were also designed to account for drug-genotype interactions, as we examined if the effects of TRZ were dependent on maternal or offspring Dhcr7 genotype25. The study design is presented in Supplemental Fig. 3.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

Unless otherwise noted, all chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co (St. Louis, MO). High-performance liquid chromatography grade solvents were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. (Waltham, MA). TRZ was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich and dissolved in sterile DMSO solution for the experiments. All sterol standards, natural and isotopically labeled, used in this study are available from Kerafast, Inc. (Boston, MA).

Trazodone injections in mice

Adult male and female B6.129P2(Cg)-Dhcr7tm1Gst/J stock # 007453 mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories. Mice homozygous for the Dhcr7Ex8 allele lack the exon 8 coding sequence and flanking splice acceptor site of the targeted gene, resulting in the truncated DHCR7 mutation most frequently observed in SLOS patients (IVS8-1G > C). Homozygous mice die shortly after birth. Heterozygous Dhcr7+/− mice are well, fertile, and indistinguishable from control, wild-type mice. Mice were maintained by breeding within the colony and refreshing twice a year with stock 000664 mice from Jackson Laboratories. Mice were housed under a 12 h light–dark cycle at constant temperature (25 °C) and humidity with ad libitum access to food (Teklad LM-485 Mouse/Rat Irradiated Diet 7912) and water in Comparative Medicine at the University of Nebraska Medical Center (UNMC), Omaha, NE. The time-pregnant female mice received i/p injections of vehicle (5% DMSO in saline) (VEH) or TRZ (20 mg/kg dissolved in VEH) from E12 to E19. In humans, TRZ (Desyrel) is given at a starting dose of 150 mg/day; and may be increased by 50 mg per day every 3–4 days to a maximum dose of 400 mg per day for outpatient use. If we take a typical dose of 150 mg/70 kg human body weight, this translates to 2.1 mg/kg/day. Animal Equivalent dose (AED in mg/kg) is calculated as AED (mg/kg) = human dose (mg/kg) (150 mg per day) × Km ratio (12.3) = 26.4 mg/kg26. As a result, we chose to use a low dose of 20 mg/kg in our mouse experiments, which translates back to 100–150 mg/day in humans, depending on the weight of the patient. Twelve WT and 12 Dhcr7+/− female mice were used in our study. Five WT and seven HET mice were injected with VEH and four WT and eight HET mice were injected with TRZ. The mouse colony was monitored three times a day and all newborn pups (P0) were collected for dissection shortly after birth. The total number of pups analyzed for this study was 160 (see Table 1 for detailed description). Frozen brain tissue samples were sonicated in ice-cold PBS containing butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) and triphenylphosphine (PPh3). The aliquots of homogenized tissue were used for sterol and oxysterol extractions and protein measurements. The protein was measured using a BCA assay (Pierce). Sterol levels were normalized to protein measurements and expressed as nmol/mg protein. All procedures were performed in accordance with the Guide for the Humane Use and Care of Laboratory Animals. The use of mice in this study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of UNMC.

Table 1.

Experimental groups.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ||||||||

| WT pup | HET pup | WT pup | HET pup | WT pup | HET pup | WT pup | HET pup | ||||||||

| 14 | 23 | 15 | 14 | 25 | 18 | 27 | 24 | ||||||||

| M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F |

| 6 | 8 | 15 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 6 | 15 | 10 | 8 | 10 | 16 | 11 | 11 | 13 |

| WT Mother | Dhcr7-HET Mother | ||||||||||||||

| Vehicle | Trazodone | Vehicle | Trazodone | ||||||||||||

| n = 5 | n = 4 | n = 7 | n = 8 | ||||||||||||

Groups 1–8 correspond to pups genotype. The numbers below WT and HET pups show how many pups were born and the next two rows show the distribution of male (M) and female (F) pups as determined by PCR. The pregnant mice were either WT or Dhcr7-HET. The numbers in the row below vehicle and TRZ show how many pregnant mice were used in the study. The total number of mice analyzed in this study were 160 pups from 12 vehicle-treated pregnant mice and 12 TRZ treated pregnant mice.

Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS)/MS (SRM) analyses

Sterols were extracted and derivatized with PTAD as described previously27 and placed in an Acquity UPLC system equipped with ANSI-compliant well plate holder coupled to a Thermo Scientific TSQ Quantis mass spectrometer equipped with an APCI source. Then 5 μL was injected onto the column (Phenomenex Luna Omega C18, 1.6 μm, 100 Å, 2.1 mm × 50 mm) with 100% MeOH (0.1% v/v acetic acid) mobile phase for 1.0 min runtime at a flow rate of 500 μL/min. Natural sterols were analyzed by selective reaction monitoring (SRM) using the following transitions: Chol 369 → 369, 7-DHC 560 → 365, desmosterol 592 → 560, lanosterol 634 → 602, with retention times of 0.7, 0.4, 0.3, and 0.3 min, respectively. SRMs for the internal standards were set to d7-Chol 376 → 376, d7-7-DHC 567 → 372, 13C3-desmosterol 595 → 563, 13C3-lanosterol 637 → 605. Final sterol numbers are reported as nmol/mg of protein.

7-DHC- and cholesterol-derived oxysterol analysis

7-DHC-derived oxysterols (DHCEO and 4α-OH-7-DHC) and cholesterol derived oxysterol 24-OH cholesterol were quantitated by LC-MS/MS using an APCI source in the positive ion mode. Lipid content from 200 μL of brain lysate was extracted and the neutral lipids fraction was purified by SPE chromatography as described previously24. Purified content was resuspended in methanol and 5 μL was injected onto the column (Phenomenex Luna Omega C18, 1.6 μm, 100 Å, 2.1 mm × 100 mm) using ACN (0.1% v/v acetic acid) (solvent A) and methanol (0.1% v/v acetic acid) (solvent B) as mobile phase. The gradient was: 5% B for 2 min; 5 to 95% B for 0.1 min; 95% B for 1.5 min; 95 to 5% B for 0.1 min; 5% B for 0.5 min. The oxysterols were analyzed by SRM using the following transitions: DHCEO 399 → 381, 4α-OH-7-DHC 383 → 365, and 24-OH cholesterol 367 → 367. The SRM for the internal standard (d7-chol) was set to 376 → 376 and response factors were calculated to accurately determine the oxysterol levels. Final oxysterol levels are reported as nmol/mg of protein.

Human serum analysis

The office of Regulatory Affairs has determined that this study does not constitute human subject research as defined at 45CFR46.102(f). Serum samples were obtained from the Nebraska Biobank that is part of the Center for Clinical and Translational Research. The biobank contains de-identified residual serum samples from patients who consent to donate any left-over after the laboratory testing. Electronic Health Record personnel identified a group of de-identified 59 samples: from users of TRZ (25 samples) and age, sex, and race matched control (34 samples) group. LC–MS/MS analyses were performed to detect and quantify TRZ and its active metabolite m-CPP in samples with TRZ listed in the medical records. Serum TRZ and m-CPP extraction and serum drug measurements were performed as previously described28. Serum sterol measurements by LC–MS/MS was done as previously described28.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using Graphpad Prism 8 for Windows. Data showed normal distribution, and the variance was comparable between the experimental and control groups. Unpaired two-tailed t tests were performed for individual comparisons between the two groups. Welch’s correction was employed when the variance between the two groups was significantly different. One-way ANOVA analyses were performed for comparisons among three or more groups. Two-way and three-way ANOVA analyses were performed to assess the interaction between maternal genotype, embryonic genotype, and drug treatment. The p values for statistically significant differences are highlighted in the figure legends.

Results

Maternal TRZ exposure alters cholesterol biosynthesis in the brain of offspring

WT and Dhcr7-HET pregnant mice received daily TRZ (20 mg/kg) or vehicle i/p injections from E12 to E19. This resulted in eight groups of newborn mice: (1) WT pup-WT mother + vehicle; (2) WT pup-WT mother + TRZ; (3) HET pup-WT mother + vehicle; (4) HET pup -WT mother + TRZ; (5) WT pup-HET mother + vehicle; (6) WT pup-HET mother + TRZ; (7) HET pup-HET mother + vehicle; and (8) HET pup-HET mother + TRZ (Table 1). We hypothesized that the most pronounced effect would be observed in the HET pups from HET mothers treated with TRZ (group 8).

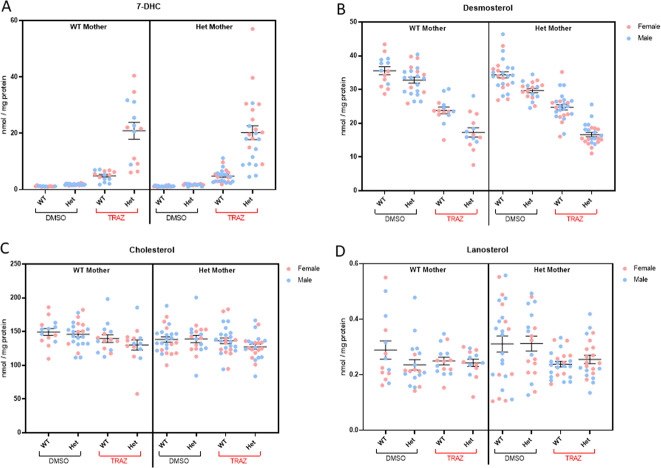

Brains were dissected from newborn pups and sterols were analyzed by LC–MS/MS. We report concentrations of cholesterol, desmosterol, 7-DHC, and lanosterol (Fig. 1) in WT and Dhcr7+/− pups born to either WT or Dhcr7+/− mothers. Maternal TRZ treatment, regardless of maternal or offspring Dhcr7 genotype, led to significantly elevated 7-DHC in all groups (p < 0.001). In contrast, desmosterol was significantly decreased by TRZ treatment. The effects of TRZ on cholesterol levels were much less pronounced, though Dhcr7+/− pups were more affected by TRZ than their WT littermates. Maternal genotype by itself did not have an effect on the TRZ-induced sterol changes. For most conditions, there was no statistically significant difference between females and males. The exception was 7-DHC where Dhcr7+/− male pups from Dhcr7+/− mothers were less affected than their female counterparts. Note that the greatest effects (and greatest variability) of TRZ on the sterol precursors were observed in the HET pups regardless of maternal genotype, suggesting a strong gene-treatment interaction in the newborn brain. This variability could not be explained by pup sex, or mouse genetic background. However, 7-DHC levels were significantly correlated with TRZ levels. Thus, we believe that the source of this variability is related to maternal TRZ metabolism, which might depend on food intake, activity, or other factors. Three-way ANOVA results examining the variables of treatment, maternal genotype, and pup genotype are presented in Table 2 corresponding to the data in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Maternal exposure to TRZ during pregnancy alters sterol profile in the brains of newborn pups.

Pregnant WT and Dhcr7+/− females were exposed to TRZ from E12 to E19 and pups’ brains were analyzed for sterols at P0. Each symbol corresponds to an individual pup brain; pink and blue symbols denote females and males, respectively. Bars correspond to the mean ± SEM. A 7-DHC; B Desmosterol; C Cholesterol; D Lanosterol. Statistical analysis: Table 2.

Table 2.

Three-way ANOVA of factors influencing brain sterol levels in newborn pups.

| ANOVA table | 7-DHC | Desmosterol | Cholesterol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trazodone treatmenta | P < 0.0001 | P < 0.0001 | P = 0.005 |

| Maternal Dhcr7 genotypeb | P = 0.8237 | P = 0.132 | P = 0.0822 |

| Pup Dhcr7 genotypeb | P < 0.0001 | P < 0.0001 | P = 0.1316 |

| Trazodone * Maternal Dhcr7 genotype | P = 0.8676 | P = 0.09 | P = 0.3774 |

| Trazodone * Pup Dhcr7 genotype | P < 0.0001 | P = 0.0093 | P = 0.2518 |

| Maternal Dhcr7 genotype * Pup Dhcr7 genotype | P = 0.8658 | P = 0.1991 | P = 0.7382 |

| Trazodone * Maternal Dhcr7 genotype * Pup Dhcr7 genotype | P = 0.8966 | P = 0.9108 | P = 0.7932 |

aTRZ versus DMSO alone.

bWT versus heterozygous for DHCR7.

Bold values indicates statistically significant.

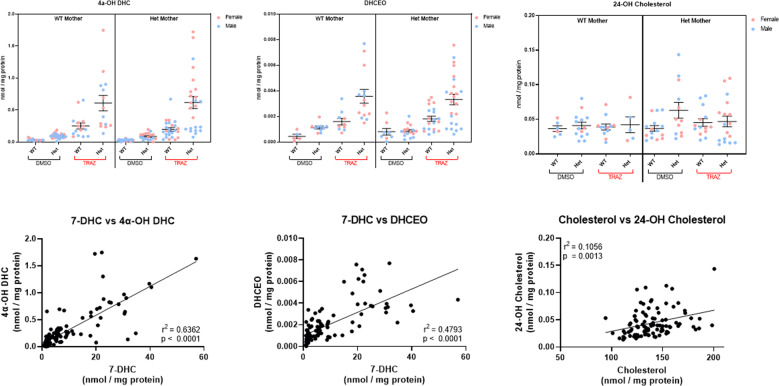

Maternal TRZ exposure greatly elevates 7-DHC derived oxysterols in the brain of offspring

The experiment above revealed that Dhcr7+/− pups from Dhcr7+/− mothers have about 12 times more 7-DHC in the brain tissue than non-treated Dhcr7+/− pups. 7-DHC is a highly unstable molecule, and spontaneously generates toxic oxysterols22–24,29–31. To determine if this pronounced elevation of highly oxidizable 7-DHC leads to the formation of 7-DHC derived oxysterols, we measured 4α-OH-DHC and DHCEO in brain tissue (Fig. 2). Maternal TRZ treatment, regardless of maternal or offspring Dhcr7 genotype, led to significantly elevated 7-DHC-derived oxysterols in all groups receiving treatment. The largest increase in the level of oxysterols was observed in the brains of Dhcr7+/− pups. Of the two oxysterols, 4α-OH-DHC was present at the highest levels. In addition, we found a strong correlation between the levels of 7-DHC and two 7-DHC-derived oxysterols (4α-OH-DHC: r2 = 0.6362; P < 0.0001; DHCEO: r2 = 0.4783; P < 0.0001). Three-way-ANOVA results examining the variables of treatment, maternal genotype, and pup genotype are presented in Table 3. In addition to 7-DHC-derived oxysterols, we assessed 24-OH-cholesterol levels derived from cholesterol. This oxysterol was not changed by TRZ treatment. The combined result show that the oxidative changes are primarily driven by 7-DHC levels (as opposed to cholesterol levels) and are most pronounced in the brains of maternally TRZ-treated HET pups regardless of maternal genotype.

Fig. 2. Maternal TRZ exposure greatly elevates 7-DHC derived oxysterols in the brains of offspring.

P0 brain tissue of newborn pups was analyzed by LC–MS/MS to measure 7-DHC-derived oxysterols: A 4α-OH-DHC, B DHCEO, and cholesterol-derived oxysterol C 24-OH cholesterol. D, E Correlation of 7-DHC and 7-DHC derived oxysterols. F Correlation of cholesterol and cholesterol derived oxysterol. Each symbol corresponds to an individual pup brain; pink and blue symbols denote females and males, respectively. Statistical analysis: Table 3.

Table 3.

Three-way ANOVA of factors influencing brain oxysterol levels in newborn pups.

| ANOVA table | 4α-OH-DHC | DHCEO |

|---|---|---|

| Trazodone treatmenta | P < 0.0001 | P < 0.0001 |

| Maternal Dhcr7 genotypeb | P = 0.7238 | P = 0.9649 |

| Pup Dhcr7 genotypeb | P < 0.0001 | P = 0.0004 |

| Trazodone * Maternal Dhcr7 genotype | P = 0.8467 | P = 0.9237 |

| Trazodone * Pup Dhcr7 genotype | P < 0.0001 | P = 0.019 |

| Maternal Dhcr7 genotype * Pup Dhcr7 genotype | P = 0.7059 | P = 0.3433 |

| Trazodone * Maternal Dhcr7 genotype * Pup Dhcr7 genotype | P = 0.7020 | P = 0.8889 |

aTRZ versus DMSO alone.

bWT versus heterozygous for DHCR7.

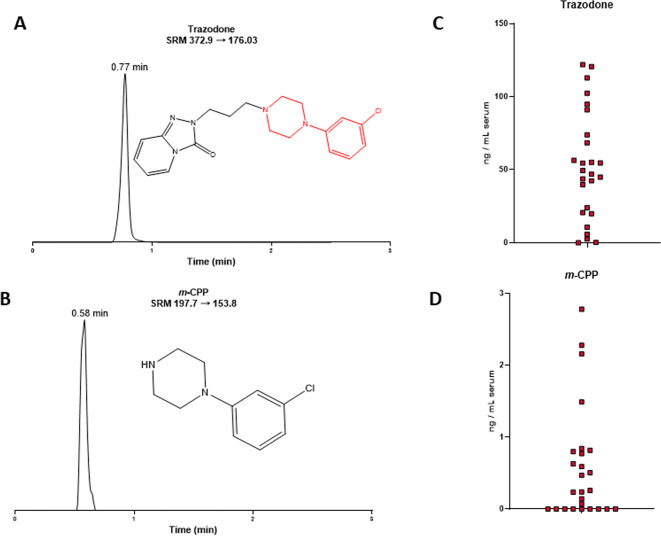

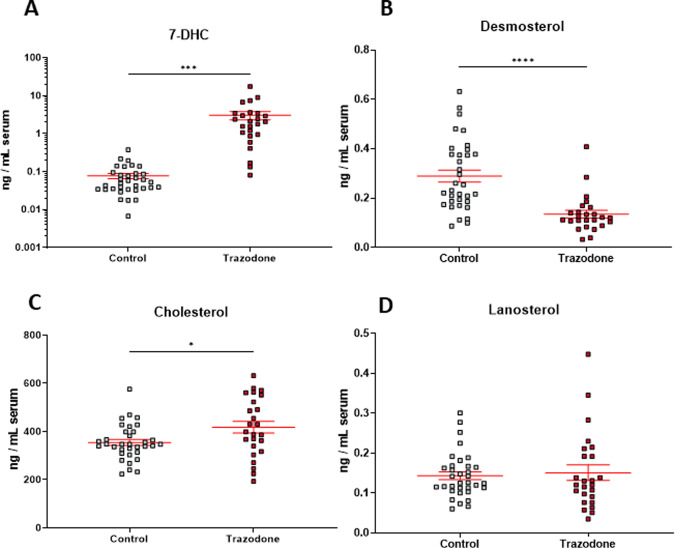

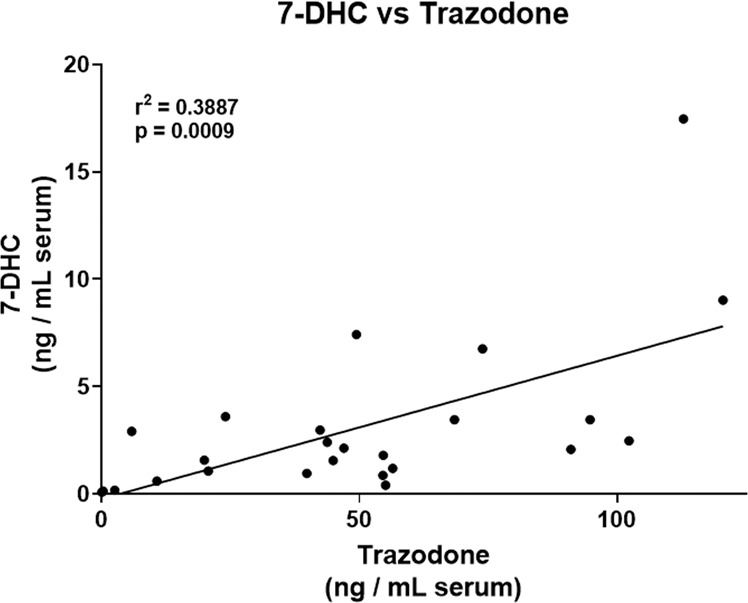

Circulating TRZ levels in human serum samples correlate with 7-DHC levels

In our previous study, we showed that three drugs, aripiprazole, haloperidol, and TRZ, each increased circulating 7-DHC levels in blood samples of psychiatric patients20. To corroborate and expand on our previous observations related to TRZ, we analyzed sterols and TRZ levels in serum samples from individuals with TRZ prescriptions. TRZ and its active metabolite m-CPP were analyzed in 25 new serum samples (Fig. 3A–D) and compared to sterol levels in 34 age- and sex-matched control samples. Sterol measurements revealed that TRZ greatly elevated circulating levels of 7-DHC (P < 0.001) and decreased desmosterol (P < 0.001), with a small effect on cholesterol and no effect on lanosterol (Fig. 4A–D; Supplemental Fig. 4A–D male vs. females). The circulating TRZ levels correlated highly with 7-DHC (r2 = 0.3887; P = 0.0009) (Fig. 5). The outcome in this serum assessment suggests that TRZ-driven cholesterol biosynthesis changes in humans likely occur on a similar scale and by the same mechanisms as in our in vivo model and that it is likely occurring in multiple tissues outside the brain.

Fig. 3. Analysis of human serum.

A typical chromatogram and structure of A trazodone and B mCPP. C TRZ and D mCPP were present in measurable quantities in 25 samples that had TRZ listed in their medical records.

Fig. 4. Sterol content in human serum.

A 7-DHC, B desmosterol, C cholesterol, and D lanosterol were measured in serum samples from TRZ-treated individuals or controls. Note logarithmic y-axis to allow that all samples are visible as individual dots.

Fig. 5. Correlation of sterol 7-DHC and TRZ in human serum.

7-DHC correlates with TRZ (r2 = 0.3887, p = 0.0009).

Discussion

The key outcomes of our studies can be summarized as follows: (1) TRZ exposure increases 7-DHC, and decreases desmosterol levels in an in vivo rodent model. (2) Dhcr7 mutations and maternal TRZ exposure interact, giving rise to toxic oxysterols that are disruptive to brain development. (3) The brains of Dhcr7+/− pups show the greatest disruptions of sterol profile in response to maternal TRZ exposure, and this does not depend on maternal Dhcr7 genotype. (4) TRZ exposure has a strong effect on circulating sterol levels in individuals taking TRZ. On a population scale, our findings point to a potentially serious public health impact of a medication as common as TRZ.

Elevation of 7-DHC concomitant with a decrease in desmosterol is characteristic for the inhibition of the DHCR7 enzyme (Supplemental Fig. 1). DHCR7 converts 7-DHC to cholesterol, and 7-dehydrodesmosterol into desmosterol. This accumulation of precursors has biological consequences, even when the difference is only a single double bond between the molecular structures32. 7-DHC is the most oxidizable (and unstable) sterol with a peroxidation rate constant of 2160, about 200-fold more than cholesterol and 10 times more than arachidonic acid, which is generally considered to be highly oxidizable33. As a result, 7-DHC readily gives rise to 7-DHC derived oxysterols30 that are well-described and their biological function has been extensively studied22–24,30,31,34. We have shown that 7-DHC derived oxysterols have potent and detrimental biological effects on cell proliferation, gene expression, and neuronal arborization22–24,30,31,34.

Over the last decade, many psychotropic drugs have been shown to interfere with sterol biosynthesis, increasing 7-DHC and resulting in oxysterol levels2–4. These properties were described initially in experiments with cell lines, followed by validation in animal models and human blood samples. Cariprazine27,35, haloperidol20, aripiprazole36, and TRZ are only a few examples of these DHCR7 inhibiting compounds. However, it should be noted that many other approved, non-CNS medications also show similar sterol-interfering effects, including amiodarone28. This raises an important question: which patient populations are most sensitive to the side effects of sterol-interfering drugs? Multiple animal studies to date suggest that two populations might be of risk—a developing embryo, and individuals with a single allele mutation in the DCHR7 gene. In addition, it appears that the risk is cumulative. In embryonic development, drug exposure and DHCR7 genotype interact, elevating 7-DHC to levels seen in genetic mouse models of SLOS. This brings us to the next question: the human relevance of our and others’ findings.

There is a legitimate concern that the inhibition of DHCR7 by TRZ in the developing human brain could have severe adverse effects. We base this view on the data from human genetic syndrome SLOS where mutations in DHCR7 affect CNS structure and function leading to developmental disabilities and autism37,38. Biochemical data from SLOS patient biomaterials suggests that TRZ could have teratogenic effects and should be avoided during pregnancy, especially if the fetus is heterozygous for DCHR7. Finally, a comprehensive literature review has identified that exposure to DHCR7 inhibitors during pregnancy leads to fetal loss in humans39, similar to those of known teratogens.

The public health relevance of our findings is also important to consider. Heterozygosity in DHCR7 is quite common in the human population, with estimates ranging from 1 to 1.5%40, and it is not routinely tested for. Combined with the abundance of off-label use and high prescription rates, maternal TRZ exposure in DHCR7 heterozygous fetuses might result in altered development, leading to developmental disability or other long-term consequences. It should be also considered that TRZ tends to be used in combination with other antipsychotics and pharmaceuticals that by themselves also inhibit sterol synthesis. The summative effect of this polypharmacy is unknown, but could be a significant concern: sterol homeostasis is undoubtedly essential for brain development and function, and interference with this finely tuned, intrinsically regulated system should be studied more extensively. Similarly, sterol biosynthesis disruption could have detrimental effects on other body systems, as sterols are essential precursors of many critical molecules—from steroid hormones to vitamins1,5.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health NIMH R01 MH110636 (K.M. and N.A.P.), R01 MH067234 (K.M.), and NICHD HD064727 (N.A.P.). The query of the Nebraska Biobank of de-identified electronic health records has been subsidized by the Great Plains IDeA-CTR grant NIH U54GM115458/NIGMS NIH. Special thanks to the participants who opt to donate their left-over serum samples to Nebraska Biobank and to Dr. Guda Purnima and Neeharica Kodali for the search of Electronic Health Records. The authors would like to thank Dr. Matthew R. Sandbulte for editing the text.

Author contributions

K.M. and N.A.P. conceived the study, obtained the funding, and designed the experiments; Z.K., L.A., A.A., and T.M. performed the animal experiments, laboratory, and statistical analysis; K.T. synthesized all sterol and oxysterol standards; all authors edited and approved the final version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41398-021-01217-w.

References

- 1.Porter FD. RSH/Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome: a multiple congenital anomaly/mental retardation syndrome due to an inborn error of cholesterol biosynthesis. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2000;71:163–174. doi: 10.1006/mgme.2000.3069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim HY, et al. Inhibitors of 7-dehydrocholesterol reductase: screening of a collection of pharmacologically active compounds in neuro2a cells. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2016;29:892–900. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.6b00054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Korade Z, et al. The effect of small molecules on sterol homeostasis: measuring 7-dehydrocholesterol in Dhcr7-deficient neuro2a cells and human fibroblasts. J. Med. Chem. 2016;59:1102–1115. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wages PA, Kim HH, Korade Z, Porter NA. Identification and characterization of prescription drugs that change levels of 7-dehydrocholesterol and desmosterol. J. Lipid Res. 2018;59:1916–1926. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M086991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Porter FD, Herman GE. Malformation syndromes caused by disorders of cholesterol synthesis. J. Lipid Res. 2011;52:6–34. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R009548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Honda A, et al. Highly sensitive analysis of sterol profiles in human serum by LC-ESI-MS/MS. J. Lipid Res. 2008;49:2063–2073. doi: 10.1194/jlr.D800017-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fagiolini A, Comandini A, Catena Dell’Osso M, Kasper S. Rediscovering trazodone for the treatment of major depressive disorder. CNS Drugs. 2012;26:1033–1049. doi: 10.1007/s40263-012-0010-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jaffer KY, et al. Trazodone for insomnia: a systematic review. Innov. Clin. Neurosci. 2017;14:24–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.La AL, et al. Long-term trazodone use and cognition: a potential therapeutic role for slow-wave sleep enhancers. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2019;67:911–921. doi: 10.3233/JAD-181145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kurtz SP, Buttram ME, Margolin ZR, Wogenstahl K. The diversion of nonscheduled psychoactive prescription medications in the United States, 2002 to 2017. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2019;28:700–706. doi: 10.1002/pds.4771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Belinskaia DA, Belinskaia MA, Barygin OI, Vanchakova NP, Shestakova NN. Psychotropic drugs for the management of chronic pain and itch. Pharmaceuticals. 2019;12:99. doi: 10.3390/ph12020099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prasad A. Efficacy of trazodone as an anti obsessional agent. Pharm. Biochem. Behav. 1985;22:347–348. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(85)90403-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borras L, de Timary P, Constant EL, Huguelet P, Eytan A. Successful treatment of alcohol withdrawal with trazodone. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2006;39:232. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-951385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Le Bon O, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy of trazodone in alcohol post-withdrawal syndrome: polysomnographic and clinical evaluations. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2003;23:377–383. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000085411.08426.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roccatagliata G, Albano C, Maffini M, Farelli S. Alcohol withdrawal syndrome: treatment with trazodone. Int. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1980;15:105–110. doi: 10.1159/000468420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh SP, Singh V, Kar N, Chan K. Efficacy of antidepressants in treating the negative symptoms of chronic schizophrenia: meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2010;197:174–179. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.067710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fink HA, MacDonald R, Rutks IR, Wilt TJ. Trazodone for erectile dysfunction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJU Int. 2003;92:441–446. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410X.2003.04358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drug Stat. Trazodone Hydrochloride Yearly Prescription. https://clincalc.com/DrugStats/Drugs/TrazodoneHydrochloride (2021).

- 19.Korade Z, Kenworthy AK. Lipid rafts, cholesterol, and the brain. Neuropharmacology. 2008;55:1265–1273. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Korade Z, et al. Effect of psychotropic drug treatment on sterol metabolism. Schizophr. Res. 2017;187:74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hall P, et al. Aripiprazole and trazodone cause elevations of 7-dehydrocholesterol in the absence of Smith-Lemli-Opitz Syndrome. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2013;110:176–178. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Korade Z, Xu L, Mirnics K, Porter NA. Lipid biomarkers of oxidative stress in a genetic mouse model of Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2013;36:113–122. doi: 10.1007/s10545-012-9504-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Korade Z, Xu L, Shelton R, Porter NA. Biological activities of 7-dehydrocholesterol-derived oxysterols: implications for Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome. J. Lipid Res. 2010;51:3259–3269. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M009365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu L, et al. DHCEO accumulation is a critical mediator of pathophysiology in a Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome model. Neurobiol. Dis. 2012;45:923–929. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Korade Z, et al. Vulnerability of DHCR7(+/-) mutation carriers to aripiprazole and trazodone exposure. J. Lipid Res. 2017;58:2139–2146. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M079475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nair AB, Jacob S. A simple practice guide for dose conversion between animals and human. J. Basic Clin. Pharm. 2016;7:27–31. doi: 10.4103/0976-0105.177703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Genaro-Mattos TC, et al. Dichlorophenyl piperazines, including a recently-approved atypical antipsychotic, are potent inhibitors of DHCR7, the last enzyme in cholesterol biosynthesis. Toxicol. Appl. Pharm. 2018;349:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2018.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Allen LB, et al. Amiodarone alters cholesterol biosynthesis through tissue-dependent inhibition of emopamil binding protein and dehydrocholesterol reductase 24. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2020;11:1413–1423. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.0c00042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Korade Z, et al. Antioxidant supplementation ameliorates molecular deficits in Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome. Biol. Psychiatry. 2014;75:215–222. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu L, Korade Z, Porter NA. Oxysterols from free radical chain oxidation of 7-dehydrocholesterol: product and mechanistic studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:2222–2232. doi: 10.1021/ja9080265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu L, et al. An oxysterol biomarker for 7-dehydrocholesterol oxidation in cell/mouse models for Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome. J. Lipid Res. 2011;52:1222–1233. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M014498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu L, Porter NA. Free radical oxidation of cholesterol and its precursors: Implications in cholesterol biosynthesis disorders. Free Radic. Res. 2015;49:835–849. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2014.985219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lamberson CR, et al. Propagation rate constants for the peroxidation of sterols on the biosynthetic pathway to cholesterol. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 2017;207:51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2017.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu L, Korade Z, Rosado DA, Jr., Mirnics K, Porter NA. Metabolism of oxysterols derived from nonenzymatic oxidation of 7-dehydrocholesterol in cells. J. Lipid Res. 2013;54:1135–1143. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M035733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Genaro-Mattos TC, et al. Maternal cariprazine exposure inhibits embryonic and postnatal brain cholesterol biosynthesis. Mol. Psychiatry. 2020;25:2685–2694. doi: 10.1038/s41380-020-0801-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Genaro-Mattos TC, et al. Maternal aripiprazole exposure interacts with 7-dehydrocholesterol reductase mutations and alters embryonic neurodevelopment. Mol. Psychiatry. 2019;24:491–500. doi: 10.1038/s41380-019-0368-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bukelis I, Porter FD, Zimmerman AW, Tierney E. Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome and autism spectrum disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2007;164:1655–1661. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07020315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nowaczyk MJ, Irons MB. Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome: phenotype, natural history, and epidemiology. Am. J. Med Genet. C Semin. Med. Genet. 2012;160C:250–262. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boland MR, Tatonetti NP. Investigation of 7-dehydrocholesterol reductase pathway to elucidate off-target prenatal effects of pharmaceuticals: a systematic review. Pharmacogenomics J. 2016;16:411–429. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2016.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cross JL, et al. Determination of the allelic frequency in Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome by analysis of massively parallel sequencing data sets. Clin. Genet. 2015;87:570–575. doi: 10.1111/cge.12425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.