Abstract

Background:

Oncologists often struggle with managing the unique care needs of older adults with cancer. We sought to determine the feasibility of delivering a transdisciplinary intervention targeting the geriatric-specific (physical function and comorbidity) and palliative care (symptoms and prognostic understanding) needs of older adults with advanced cancer.

Methods:

We randomly assigned patients age ≥65 years with incurable gastrointestinal or lung cancer to a transdisciplinary intervention or usual care. Intervention patients received two visits with a geriatrician who addressed patients’ palliative care needs in addition to conducting a geriatric assessment. We pre-defined the intervention as feasible if >70% of eligible patients enrolled in the study and >75% completed study visits and surveys. At baseline and week 12, we assessed patients’ quality of life (QOL, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy General), symptoms (Edmonton Symptom Assessment System), and communication confidence (Perceived Efficacy in Patient-Physician Interactions). We calculated mean change scores in outcomes and estimated intervention effect sizes (ES, Cohen’s d) for changes from baseline to week 12, where 0.2 indicates a small effect, 0.5 a medium effect, and 0.8 a large effect.

Results:

From 2/2017–6/2018, we randomized 62 patients (55.9% enrollment rate [most common reason for refusal was feeling too ill]; median age=72.3 years; cancer types: 56.5% gastrointestinal, 43.5% lung). Among intervention patients, 82.1% attended the first visit and 79.6% attended both. Overall, 89.7% completed all study surveys. Compared to usual care, intervention patients had less QOL decrement (−0.77 vs −3.84, ES=0.21), reduced number of moderate/severe symptoms (−0.69 vs +1.04, ES=0.58), and improved communication confidence (+1.06 vs −0.80, ES=0.38).

Conclusion:

In this pilot trial, enrollment exceeded 55% and >75% of enrollees completed all study visits and surveys. The transdisciplinary intervention targeting older patients’ unique care needs demonstrated encouraging effect size estimates for enhancing patients’ QOL, symptom burden, and communication confidence.

Keywords: Geriatric oncology, Randomized Controlled Trial, Cancer, Palliative Care, Quality of Life, Symptoms

Introduction

Older adults represent a growing population with complex medical problems, including cancer, which disproportionately impacts these individuals.1 Over half of newly diagnosed cancers occur in patients over age 65, and this older population accounts for nearly three-fourths of cancer deaths.1 Older adults diagnosed with cancer also experience worse survival outcomes compared with younger patients, which may be due to differential treatment of the geriatric cancer population.2 Compared with younger patients, older patients with cancer are more likely to be undertreated and experience earlier discontinuation of treatment for their stage of cancer.3, 4 Although studies suggest that poor symptom management and inadequate social support may explain this suboptimal treatment of older patients, more research is needed to address the multifaceted geriatric and palliative care needs of this population.3, 4

A challenging constellation of medical and psychosocial issues can add to the complexity of caring for older adults with cancer. Older patients experience unique concerns related to their physical function, comorbid conditions, and medication management (i.e. geriatric-specific issues) as well as their symptom burden, prognostic understanding, and coping (i.e. palliative care issues).5–9 Despite the unique health problems of older adults with cancer, interventions targeting the geriatric-specific and palliative care concerns of this population are lacking.7, 10–14 Importantly, prior work has demonstrated that palliative care interventions improve quality of life (QOL), mood, and possibly even survival for patients with advanced cancer.15–17 However, for older adults with cancer, palliative care consultation alone may not fully address all their concurrent medical and psychosocial comorbidities.18, 19 The physiologic, psychological, and social support needs of older and younger patients differ, and evidence suggests that older patients with cancer should receive palliative care interventions tailored to their unique needs.5, 7, 8, 18, 19 Additionally, geriatricians have developed tools to help assess and manage older patients’ distinct geriatric-specific concerns, but we lack data about whether these interventions effectively address patients’ palliative care needs.20 Thus, we must develop and test interventions targeting both the geriatric and palliative care issues unique to older adults with cancer.

We conducted a pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT) of a transdisciplinary intervention designed to address the geriatric-specific and palliative care needs of older adults with cancer. We developed the intervention using a transdisciplinary approach, which included integrative and collaborative training to blend the disciplines of geriatrics and palliative care. We sought to determine the feasibility and acceptability of this intervention and to estimate effect-sizes for improving patient-reported outcomes. We hypothesized that the transdisciplinary intervention would be feasible to deliver, and patients would find the intervention acceptable. Importantly, data from this study will inform future work by allowing us to estimate effect-sizes of the transdisciplinary intervention for improving patients’ QOL, symptoms, functional outcomes, communication confidence, and illness perceptions.

Methods

Study Design and Procedures

From 2/15/2017–6/28/2018, we enrolled patients at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) in an unblinded, RCT of a transdisciplinary intervention versus usual care (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02868112). Trained study staff identified and recruited patients throughout the study period by monitoring the oncology clinic schedules. Following written informed consent, patients completed baseline study measures. After patients completed baseline study measures, the Office of Data Quality randomly assigned patients 1:1 to receive the transdisciplinary intervention or usual care, stratified by cancer type (gastrointestinal or lung). The Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol.

Participants

Patients eligible for study participation included those at least 65 years old and within 8-weeks of a diagnosis of incurable gastrointestinal or lung cancer. We determined if patients had incurable disease based on chemotherapy order treatment intent designation (palliative versus curative) or documentation from oncology clinic notes in the electronic health record (EHR) if patients were not receiving chemotherapy. Study participants also had to be able to read and respond to study questionnaires in English. We excluded patients who were not planning to receive their longitudinal cancer care at MGH.

Transdisciplinary Geriatric and Palliative Care Intervention

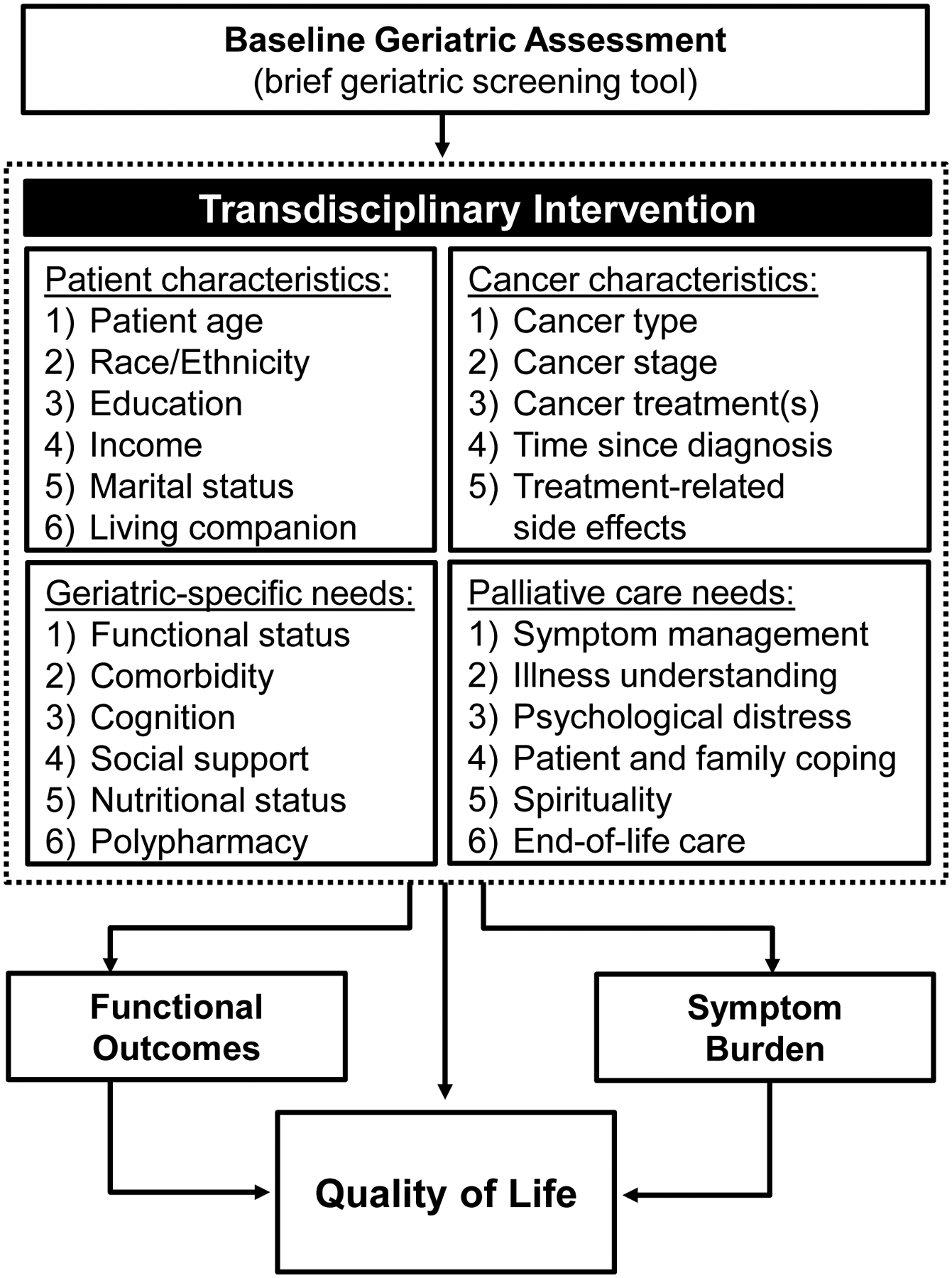

Based on a conceptual model of geriatric assessment-driven interventions in oncology and guideline-recommendations, we developed a framework for the transdisciplinary intervention(Figure-1).12–14, 21 We chose a transdisciplinary approach to intervention development, which included an integrative and collaborative training model that merged the disciplines of geriatrics and palliative care.22 Patients assigned to the transdisciplinary intervention participated in two in-person visits with a board-certified geriatrician. Visits took place in the geriatricians’ clinic, which is not co-located in the cancer center. The first visit occurred within six-weeks of enrollment and the second visit within four to six-weeks following the initial visit. Prior to study start, the geriatricians received four, one-hour in-person didactic sessions, delivered by geriatricians, palliative care clinicians, and a medical oncologist, focused on the unique geriatric-specific and palliative care issues of an older oncology population (e.g. chemotherapy logistics and side effects, cancer-specific symptoms and prognosis, collaborating with the oncology team, symptom management, and prognostic disclosure). Additionally, patients completed a brief geriatric screening tool prior to the first visit, which we provided to the geriatrician to allow them to tailor their care. The brief tool contained information about patients’ self-reported symptom burden,23, 24 nutrition status,25 and vulnerability.26 For each visit, we provided the geriatricians with templated notes that the clinicians placed in the EHR, which included topics focused on patients’ palliative care needs and issues obtained from geriatric assessment. Specifically, we instructed the geriatricians to discuss and address patients’ physical and psychological symptom concerns, comorbid conditions and polypharmacy, cognitive issues, availability of social supports, functional impairments, use of coping strategies, and illness understanding. Following each visit, the geriatrician communicated (either in-person or via phone/email) their findings with the patient’s oncology team.

Figure 1.

Intervention Framework

Usual Care

Participants receiving usual care could meet with a geriatrician upon request by the oncologist, patient, and/or family. However, no patients receiving usual care ultimately met with a geriatrician. All patients, regardless of group assignment, continued to receive routine oncology care throughout the study period.

Study Measures

Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics

Participants completed baseline study measures prior to randomization. We asked patients to self-report their sex, race, relationship status, employment, education, income, and comorbid conditions. We obtained information about participants’ age and cancer from the EHR.

Patient-Reported Outcomes

At baseline and week-12, participants self-reported their QOL, symptoms, functional outcomes, communication confidence, and illness perceptions. To assess QOL, we used the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G), a validated tool assessing QOL in older adults with cancer.27 The FACT-G consists of subscales assessing well-being across four domains (physical, functional, emotional and social) during the prior seven days. Scores range from 0–108, with higher scores indicating better QOL.

To assess symptoms, we used the self-administered Edmonton Symptom Assessment System-revised (ESAS-r), a validated tool measuring patients’ symptoms.23 Each specific symptom is scored from 0–10 (0=absence of the symptom and 10=worst possible severity). Consistent with prior research, we categorized the severity of ESAS scores as 0 (none), 1 to 3 (mild), 4 to 6 (moderate), and 7 to 10 (severe) and computed composite ESAS-physical and ESAS-total symptom scores.28, 29 To measure depression symptoms, we used the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), with higher scores reflecting worse depression symptoms (scores range from 0–15).30 Scores >4 indicating the presence of clinically significant depression symptoms.

To assess functional outcomes, we asked patients about their Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADLs). For ADLs, we used a subscale from the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) to determine the number of independent ADLs (range 0–10).31 For IADLs, we used a subscale from the Multidimensional Functional Assessment Questionnaire (MFAQ) from the Older American Resources and Services (OARS) Program to determine the number of independent IADLs (range 0–7).32

To assess communication confidence, we used the 10-item Perceived Efficacy in Patient-Physician Interactions (PEPPI), a tool validated for use in older patients, with scores ranging from 10–50 and higher scores reflecting greater confidence in the ability to communicate and seek help from providers.33

To assess illness perceptions, we used the Brief Illness Perceptions Questionnaire (BIPQ), a validated instrument, with scores ranging from 0–80 and higher scores indicating a more threatening perception of the illness.34

Acceptability of the Intervention

As part of the week-12 assessment, we asked patients assigned to the intervention to complete a written survey inquiring about the timing and utility of the intervention. Specifically, we asked patients about their perceptions of the visit number and length, and whether they perceived the visit with the geriatrician as helpful.

Statistical Analysis

The primary endpoint was feasibility. We pre-defined the intervention as feasible if at least 70% of patients enrolled in the study, and at least 75% of living patients completed study visits and surveys. To evaluate the acceptability of the intervention, we tabulated responses to the acceptability survey given to participants who received the intervention inquiring about the number of visits, timing of visits, and helpfulness of the intervention.

Secondary endpoints included an evaluation of the effect-sizes of the transdisciplinary intervention for improving QOL, symptom burden, functional outcomes, communication confidence, and illness perceptions. For each of these outcomes, we calculated effect-sizes (Cohen’s d) for changes from baseline to week-12 ([Mean change score (intervention arm)–Mean change score (usual care arm)]/SDpooled), where 0.2 indicates a small effect, 0.5 a medium effect, and 0.8 a large effect.35 Due to the pilot nature of this study, we used available case analysis.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Table-1 displays baseline characteristics for each of the study arms. Patients had a median age of 72.26 years (range: 65.22–91.84 years), and the majority were white (98.4%), male (54.8%), married (66.1%), and retired (79.0%). The most common cancer types were non-small cell lung cancer (38.7%), pancreatic (22.6%), and hepatobiliary (16.1%). Patients were an average of 4.40 weeks (standard deviation [SD]=2.06) from their diagnosis with advanced cancer, and 74.2% reported at least one comorbid condition.

Table 1.

Baseline Participant Characteristics

| Characteristic | Usual Care (N=32) | Geriatric Intervention (N=30) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |

| Age - mean (SD) | 73.68 | 6.22 | 73.94 | 6.51 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 18 | 56.2 | 16 | 53.3 |

| Female | 14 | 43.8 | 14 | 46.7 |

| Race | ||||

| White | 32 | 100.0 | 29 | 96.7 |

| African American | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 3.3 |

| Relationship status | ||||

| Married | 20 | 62.5 | 21 | 70.0 |

| Widowed | 3 | 9.4 | 6 | 20.0 |

| Divorced | 4 | 12.5 | 2 | 6.7 |

| Single | 5 | 15.6 | 1 | 3.3 |

| Employment | ||||

| Full time | 5 | 15.6 | 6 | 20.0 |

| Part time | 1 | 3.1 | 1 | 3.3 |

| Retired | 26 | 81.2 | 23 | 76.7 |

| Education | ||||

| Less than college graduate | 16 | 50.0 | 19 | 63.3 |

| College graduate and above | 15 | 46.9 | 10 | 33.3 |

| Annual Income | ||||

| Under $60,000 | 12 | 42.9 | 8 | 32.0 |

| $60,000 and above | 16 | 57.1 | 17 | 68.0 |

| Cancer Type | ||||

| NSCLC | 12 | 37.5 | 12 | 40.0 |

| Pancreatic | 4 | 12.5 | 10 | 33.3 |

| Hepatobiliary | 6 | 18.8 | 4 | 13.3 |

| Gastroesophageal | 4 | 12.5 | 2 | 6.7 |

| Colorectal | 4 | 12.5 | 1 | 3.3 |

| SCLC | 2 | 6.2 | 1 | 3.3 |

| Weeks since advanced cancer diagnosis - mean (SD) | 4.64 | 2.02 | 4.15 | 2.10 |

| Comorbid Conditions | ||||

| Chronic lung disease | 8 | 25.0 | 8 | 26.7 |

| Diabetes | 8 | 25.0 | 7 | 23.3 |

| Liver problem | 10 | 31.2 | 3 | 10.0 |

| Kidney problem | 4 | 12.5 | 6 | 20.0 |

| Stroke | 2 | 6.2 | 7 | 23.3 |

| Circulation trouble | 1 | 3.1 | 5 | 16.7 |

| Rheumatologic condition | 2 | 6.2 | 3 | 10.0 |

| Heart attack | 3 | 9.4 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Heart failure | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; NSCLC, Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer; SCLC, Small Cell Lung Cancer.

Baseline Patient-Reported Outcomes

Baseline patient-reported outcomes were balanced between randomization arms(Table-2). Patients reported an average of 3.28 (SD=3.15) moderate-severe symptoms at baseline, with 73.3% reporting at least one moderate-severe symptom, and 24.2% having clinically significant depression symptoms. At baseline, patients reported an average of 4.26 (SD=3.07) independent ADLs and 5.52 (SD=1.80) independent IADLs, with only one patient reporting independence on all ADLs/IADLs.

Table 2.

Baseline Patient-Reported Outcomes

| Patient-Reported Outcomes | Usual Care (N=32) | Intervention (N=30) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Quality of Life | ||||

| FACT-G Total | 78.94 | 12.65 | 76.50 | 16.78 |

| Symptoms | ||||

| ESAS-Physical Symptoms | 17.75 | 13.39 | 17.70 | 13.65 |

| ESAS-Total Symptoms | 24.78 | 18.23 | 27.63 | 19.88 |

| Number of Moderate-Severe ESAS Symptoms | 2.91 | 2.87 | 3.71 | 3.44 |

| GDS Depression Symptoms | 3.13 | 2.69 | 3.73 | 3.48 |

| Functional Outcomes | 17.75 | 13.39 | 17.70 | 13.65 |

| Number of Independent ADLs | 4.06 | 2.81 | 4.47 | 3.36 |

| Number of Independent IADLs | 5.75 | 1.44 | 5.27 | 2.12 |

| Communication Confidence and Illness Perceptions | ||||

| Perceived Efficacy in Patient-Physician Interactions | 47.00 | 5.81 | 45.87 | 5.17 |

| Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire | 36.44 | 11.30 | 41.97 | 12.07 |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; FACT-G, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General; ESAS, Edmonton Symptom Assessment System; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale; ADLs, Activities of Daily Living; IADLs, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living.

Feasibility and Acceptability of the Intervention

We enrolled 55.9% (62/111) of patients approached(Figure-2). The most common reasons for refusing study participation were feeling too ill (20.7%) and not interested in research (18.9%). Among patients assigned to the intervention, 82.1% (23/28) attended the first visit and 79.6% (39/49) attended both. Overall, 89.7% completed the baseline and week-12 study surveys.

Figure 2.

CONSORT diagram

Participants found the intervention acceptable, with 73.3% (11/15) reporting that the number of visits with the geriatrician was the ‘right amount,’ 68.8% (11/16) reporting that the length of the visit was the ‘right amount,’ and 62.5% (10/16) reporting that the visit was ‘helpful’ (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Intervention Acceptability Ratings

Intervention Effect-Sizes for Improving Patient-Reported Outcomes

We found that the intervention had small to medium effect-sizes for improving many patient-reported outcomes(Table-3). From baseline to week-12, intervention patients had less decrement in their QOL than usual care patients (Mean-change=−0.77 vs −3.84, effect-size=0.21). Additionally, intervention patients experienced decreased severity of their ESAS-total scores (Mean-change=−0.47 vs +5.72, effect-size=0.35), reduction in the number of moderate-severe ESAS symptoms (Mean-change=−0.69 vs +1.04, effect-size=0.58), and lower GDS depression scores (Mean-change=−0.47 vs +0.58, effect-size=0.36) compared with usual care. Intervention patients also reported improvements in their communication confidence (Mean-change=+1.06 vs −0.80, effect-size=0.38).

Table 3.

Effect Size Estimates of the Intervention for Improving Patient-Reported Outcomes

| Patient-Reported Outcomes | Usual Care | Intervention | Cohen’s d Effect Size* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Δ | SD | Mean Δ | SD | ||

| Quality of Life | |||||

| FACT-G Total | −3.84 | 15.75 | −0.77 | 14.10 | 0.21 |

| Symptoms | |||||

| ESAS-Physical Symptoms | 3.96 | 10.69 | 0.06 | 15.72 | 0.29 |

| ESAS-Total Symptoms | 5.72 | 13.94 | −0.47 | 20.61 | 0.35 |

| Number of Moderate-Severe ESAS Symptoms | 1.04 | 2.82 | −0.69 | 3.18 | 0.58 |

| GDS Depression Symptoms | 0.58 | 2.90 | −0.47 | 2.98 | 0.36 |

| Functional Outcomes | |||||

| Number of Independent ADLs | −0.68 | 1.93 | −0.88 | 3.67 | 0.07 |

| Number of Independent IADLs | −0.24 | 1.48 | −0.19 | 1.22 | 0.04 |

| Communication Confidence and Illness Perceptions | |||||

| Perceived Efficacy in Patient-Physician Interactions | −0.80 | 6.49 | 1.06 | 2.54 | 0.38 |

| Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire | 0.96 | 9.95 | 0.88 | 12.77 | 0.01 |

For each of these outcomes, we calculated effect sizes (Cohen’s d) for changes from baseline to week 12 ([Mean change score (intervention arm) – Mean change score (usual care arm)]/SDpooled), where 0.2 indicates a small effect, 0.5 a medium effect, and 0.8 a large effect.

Abbreviations: Mean Δ, mean change; SD, standard deviation; FACT-G, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General; ESAS, Edmonton Symptom Assessment System; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale; ADLs, Activities of Daily Living; IADLs, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living.

Discussion

In this pilot RCT, we investigated the feasibility and acceptability of a transdisciplinary intervention targeting patients’ geriatric and palliative care needs, and we estimated the effect-sizes of this intervention for improving patient-reported outcomes in older adults with cancer. We enrolled over half of patients approached, and over three-fourths assigned to the intervention attended the geriatrician visits. Additionally, most patients found the intervention acceptable and helpful. Importantly, the intervention demonstrated encouraging effect-size estimates for enhancing patients’ QOL, physical and psychological symptoms, and communication confidence.

Importantly, our work highlights the need for interventions to target the palliative care and geriatric-specific issues unique to older adults with cancer. Consistent with prior work, at baseline, patients in our sample averaged over three moderate-severe symptoms, with nearly three-fourths reporting at least one moderate-severe symptom, and one-fourth endorsing depression symptoms.7, 8, 10, 11, 36 In addition, three-fourths of patients had at least one comorbid condition, and only one patient in our cohort reported being independent with all their ADLs/IADLs, which is also consistent with previous research.9, 36 With such high baseline symptom burden, pervasive comorbid conditions, and impaired functional status, our findings underscore the tremendous potential for efforts such as this transdisciplinary intervention to enhance care outcomes for the geriatric oncology population.

This study represents our first attempt to integrate a transdisciplinary intervention addressing patients’ geriatric-specific and palliative care needs into the care of older adults with cancer. The current intervention ensures that older adults with cancer receive focused attention to their complex combination of medical and psychosocial issues by incorporating geriatricians into their outpatient oncologic care. Although we enrolled over half of patients approached, we did not meet our goal of 70%. This likely resulted from the profound illness severity of the study population, as nearly half who refused study participation reported feeling too ill to participate. In future iterations of this work, we will adapt our study procedures to further remove barriers and ensure patients can participate; this represents a high-risk group who may particularly benefit from interventions such as this.18, 19 Our geriatricians see patients at a clinic that is not integrated within the cancer center, and moving forward we will work to co-locate our geriatric interventions within the cancer center to minimize the burden of additional travel and extra visits. We also chose an ambitious enrollment goal, which several studies of geriatric-specific interventions have similarly not achieved.37–39 Despite not meeting our pre-specified enrollment rate, the majority of participants completed study visits and surveys, and most found the intervention acceptable. Therefore, our findings highlight the feasibility of delivering a transdisciplinary intervention focused on the geriatric-specific issues and palliative care needs of older patients with cancer, yet we also learned important lessons to inform future iterations of this work to enhance care quality and outcomes for the geriatric oncology population, a rapidly growing group of patients needing interventions tailored to their distinct needs.

We found that the transdisciplinary intervention resulted in favorable effect-size estimates for improving several important patient-reported outcomes. During the study period, QOL scores deteriorated over time in both study arms, as expected with an advanced cancer population,15–17 but we observed better preservation of QOL in the intervention arm. Notably, intervention patients had improvements in their symptom burden and communication confidence during the study period, but usual care patients experienced worsening of these outcomes. Patients’ symptoms and QOL represent direct targets of the transdisciplinary intervention, which could explain the favorable results for these outcomes. However, the findings for enhancing communication confidence are hypothesis-generating, potentially related to the additional attention patients received from geriatricians trained to comprehensively address their unique needs while empowering them to openly discuss their concerns. Importantly, patients’ QOL, symptom burden, and communication confidence represent patient-centered outcomes critical to consider when designing interventions for older adults with cancer, and our results underscore the potential for targeted supportive care interventions to address these outcomes.12, 40

Several limitations warrant discussion. First, we conducted this trial at an academic institution with limited sociodemographic diversity, limiting the generalizability of our findings. Second, we lack data regarding certain factors that could influence the impact of the intervention, including patients’ social supports, cognition, and receipt of other services, such as psychiatry or physical and occupational therapy. Future work should investigate whether these, and other important factors, such as cancer type and use of certain coping strategies, influence the effects of this intervention on patient outcomes. Notably, our study cohort included a heterogeneous group of patients with incurable gastrointestinal or lung cancer, which likely received different treatment regimens, and future research will need to investigate how the disease and treatment influence the impact of this intervention. Additionally, we did not audio-record study visits, and thus we do not have specific information regarding the factors discussed at each study visit or the amount of variation in the content of each visit. We also lack information about clinicians’ perceptions regarding the utility of the transdisciplinary intervention, and future efforts to fully integrate geriatricians into the cancer care team should consider these important perspectives.

In this study, we sought to determine the feasibility and acceptability of a transdisciplinary intervention designed to address the geriatric-specific and palliative care needs of older adults with advanced cancer. Although we did not meet our pre-determined feasibility goal of enrolling over 70% of patients approached, we found that over half of patients we asked to participate enrolled, and most completed all study visits and surveys, with the majority finding the intervention acceptable and helpful. Importantly, we found encouraging effect-size estimates for the transdisciplinary intervention to improve patients’ QOL, physical and psychological symptoms, and communication confidence. Additionally, our data highlight older patients’ substantially high symptom burden, comorbidity, and functional impairments, thus underscoring the critical importance of efforts to address the geriatric and palliative care needs of older adults with cancer. Collectively, these results support the need for a larger RCT to demonstrate the efficacy of this care model to enhance care outcomes for the geriatric oncology population.

Funding sources:

NCI K24 CA181253 (Temel), K24 AG056589 (Mohile), NIH/NIA R03AG053314 (Nipp)

Footnotes

Presented in abstract form at the 2019 ASCO Annual Meeting in Chicago, IL.

References

- 1.Yancik R Population aging and cancer: a cross-national concern. Cancer J. 2005;11: 437–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel SS, Nelson R, Sanchez J, et al. Elderly patients with colon cancer have unique tumor characteristics and poor survival. Cancer. 2013;119: 739–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neugut AI, Matasar M, Wang X, et al. Duration of adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer and survival among the elderly. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24: 2368–2375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sargent DJ, Goldberg RM, Jacobson SD, et al. A pooled analysis of adjuvant chemotherapy for resected colon cancer in elderly patients. N Engl J Med. 2001;345: 1091–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mor V, Allen S, Malin M. The psychosocial impact of cancer on older versus younger patients and their families. Cancer. 1994;74: 2118–2127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nipp RD, Greer JA, El-Jawahri A, et al. Coping and Prognostic Awareness in Patients With Advanced Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017: JCO2016713404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheung WY, Le LW, Gagliese L, Zimmermann C. Age and gender differences in symptom intensity and symptom clusters among patients with metastatic cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19: 417–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Linden W, Vodermaier A, Mackenzie R, Greig D. Anxiety and depression after cancer diagnosis: prevalence rates by cancer type, gender, and age. J Affect Disord. 2012;141: 343–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Derks MG, de Glas NA, Bastiaannet E, et al. Physical Functioning in Older Patients With Breast Cancer: A Prospective Cohort Study in the TEAM Trial. Oncologist. 2016;21: 946–953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brighi N, Balducci L, Biasco G. Cancer in the elderly: is it time for palliative care in geriatric oncology? J Geriatr Oncol. 2014;5: 197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blank TO, Bellizzi KM. A gerontologic perspective on cancer and aging. Cancer. 2008;112: 2569–2576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mohile SG, Velarde C, Hurria A, et al. Geriatric Assessment-Guided Care Processes for Older Adults: A Delphi Consensus of Geriatric Oncology Experts. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2015;13: 1120–1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dotan E, Walter LC, Baumgartner J, et al. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Older Adult Oncology. Version 1.2019. Available at: NCCN.org. Accessed August 24, 2019.

- 14.Mohile SG, Dale W, Somerfield MR, et al. Practical Assessment and Management of Vulnerabilities in Older Patients Receiving Chemotherapy: ASCO Guideline for Geriatric Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2018: JCO2018788687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363: 733–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383: 1721–1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Temel JS, Greer JA, El-Jawahri A, et al. Effects of Early Integrated Palliative Care in Patients With Lung and GI Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35: 834–841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nipp RD, El-Jawahri A, Traeger L, et al. Differential effects of early palliative care based on the age and sex of patients with advanced cancer from a randomized controlled trial. Palliat Med. 2018: 269216317751893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nipp RD, Greer JA, El-Jawahri A, et al. Age and Gender Moderate the Impact of Early Palliative Care in Metastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Oncologist. 2016;21: 119–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stuck AE, Siu AL, Wieland GD, Adams J, Rubenstein LZ. Comprehensive geriatric assessment: a meta-analysis of controlled trials. Lancet. 1993;342: 1032–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mohile S, Dale W, Magnuson A, Kamath N, Hurria A. Research priorities in geriatric oncology for 2013 and beyond. Cancer Forum. 2013;37: 216–221. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dankwa-Mullan I, Rhee KB, Stoff DM, et al. Moving toward paradigm-shifting research in health disparities through translational, transformational, and transdisciplinary approaches. Am J Public Health. 2010;100 Suppl 1: S19–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bruera E, Kuehn N, Miller MJ, Selmser P, Macmillan K. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): a simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J Palliat Care. 1991;7: 6–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Lowe B. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4. Psychosomatics. 2009;50: 613–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferguson M, Capra S, Bauer J, Banks M. Development of a valid and reliable malnutrition screening tool for adult acute hospital patients. Nutrition. 1999;15: 458–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saliba D, Elliott M, Rubenstein LZ, et al. The Vulnerable Elders Survey: a tool for identifying vulnerable older people in the community. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49: 1691–1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Overcash J, Extermann M, Parr J, Perry J, Balducci L. Validity and reliability of the FACT-G scale for use in the older person with cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 2001;24: 591–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nipp RD, El-Jawahri A, Moran SM, et al. The relationship between physical and psychological symptoms and health care utilization in hospitalized patients with advanced cancer. Cancer. 2017;123: 4720–4727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nipp RD, El-Jawahri A, D’Arpino SM, et al. Symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder among hospitalized patients with cancer. Cancer. 2018;124: 3445–3453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.D’Ath P, Katona P, Mullan E, Evans S, Katona C. Screening, detection and management of depression in elderly primary care attenders. I: The acceptability and performance of the 15 item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS15) and the development of short versions. Fam Pract. 1994;11: 260–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stewart AL, Kamberg CJ. Physical functioning measures In: Stewart AL, Ware JE Jr., editors. Measuring functioning and well-being; the Medical Outcomes Study approach. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1992:86–101. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fillenbaum GG, Smyer MA. The development, validity, and reliability of the OARS multidimensional functional assessment questionnaire. J Gerontol. 1981;36: 428–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maly RC, Frank JC, Marshall GN, DiMatteo MR, Reuben DB. Perceived efficacy in patient-physician interactions (PEPPI): validation of an instrument in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46: 889–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Broadbent E, Petrie KJ, Main J, Weinman J. The brief illness perception questionnaire. J Psychosom Res. 2006;60: 631–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cohen J A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112: 155–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pandya C, Magnuson A, Flannery M, et al. Association Between Symptom Burden and Physical Function in Older Patients with Cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67: 998–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Demark-Wahnefried W, Clipp EC, Morey MC, et al. Lifestyle intervention development study to improve physical function in older adults with cancer: outcomes from Project LEAD. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24: 3465–3473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oldervoll LM, Loge JH, Lydersen S, et al. Physical exercise for cancer patients with advanced disease: a randomized controlled trial. Oncologist. 2011;16: 1649–1657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Horgan AM, Leighl NB, Coate L, et al. Impact and feasibility of a comprehensive geriatric assessment in the oncology setting: a pilot study. Am J Clin Oncol. 2012;35: 322–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nipp RD, Yao NA, Lowenstein LM, et al. Pragmatic study designs for older adults with cancer: Report from the U13 conference. J Geriatr Oncol. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]