Key Points

Question

Where might there be opportunities to do the greatest good toward reducing overall concussion incidence and head impact exposure (HIE) in collegiate football?

Findings

In this cohort study, concussion incidence and HIE were disproportionately higher in the preseason than the regular season, and most concussions and HIE occurred during football practices.

Meaning

These findings point to specific areas where public policy, education, and other prevention strategies could be targeted to make the greatest overall reduction in concussion incidence and HIE in college football, which has important implications for protecting the safety and health of collegiate football players.

Abstract

Importance

Concussion ranks among the most common injuries in football. Beyond the risks of concussion are growing concerns that repetitive head impact exposure (HIE) may increase risk for long-term neurologic health problems in football players.

Objective

To investigate the pattern of concussion incidence and HIE across the football season in collegiate football players.

Design, Setting, and Participants

In this observational cohort study conducted from 2015 to 2019 across 6 Division I National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) football programs participating in the Concussion Assessment, Research, and Education (CARE) Consortium, a total of 658 collegiate football players were instrumented with the Head Impact Telemetry (HIT) System (46.5% of 1416 eligible football players enrolled in the CARE Advanced Research Core). Players were prioritized for instrumentation with the HIT System based on their level of participation (ie, starters prioritized over reserves).

Exposure

Participation in collegiate football games and practices from 2015 to 2019.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Incidence of diagnosed concussion and HIE from the HIT System.

Results

Across 5 seasons, 528 684 head impacts recorded from 658 players (all male, mean age [SD], 19.02 [1.25] years) instrumented with the HIT System during football practices or games met quality standards for analysis. Players sustained a median of 415 (interquartile range [IQR], 190-727) recorded head impacts (ie, impacts) per season. Sixty-eight players sustained a diagnosed concussion. In total, 48.5% of concussions (n = 33) occurred during preseason training, despite preseason representing only 20.8% of the football season (0.059 preseason vs 0.016 regular-season concussions per team per day; mean difference, 0.042; 95% CI, 0.020-0.060; P = .001). Total HIE in the preseason occurred at twice the proportion of the regular season (324.9 vs 162.4 impacts per team per day; mean difference, 162.6; 95% CI, 110.9-214.3; P < .001). Every season, HIE per athlete was highest in August (preseason) (median, 146.0 impacts; IQR, 63.0-247.8) and lowest in November (median, 80.0 impacts; IQR, 35.0-148.0). Over 5 seasons, 72% of concussions (n = 49) (game proportion, 0.28; 95% CI, 0.18-0.40; P < .001) and 66.9% of HIE (262.4 practices vs 137.2 games impacts per player; mean difference, 125.3; 95% CI, 110.0-140.6; P < .001) occurred in practice. Even within the regular season, total HIE in practices (median, 175.0 impacts per player per season; IQR, 76.0-340.5) was 84.2% higher than in games (median, 95.0 impacts per player per season; IQR, 32.0-206.0).

Conclusions and Relevance

Concussion incidence and HIE among college football players are disproportionately higher in the preseason than regular season, and most concussions and HIE occur during football practices, not games. These data point to a powerful opportunity for policy, education, and other prevention strategies to make the greatest overall reduction in concussion incidence and HIE in college football, particularly during preseason training and football practices throughout the season, without major modification to game play. Strategies to prevent concussion and HIE have important implications to protecting the safety and health of football players at all competitive levels.

This study investigates the pattern of concussion incidence and head impact exposure across the football season in collegiate football players.

Introduction

Concussion ranks among the most common injuries in US football.1 Over the past 2 decades, large-scale studies have informed the epidemiology, acute effects, and recovery associated with concussion in collegiate football players.2,3 Research has driven a major shift in contemporary approaches to injury management and return to play after concussion, which have improved player safety.4 However, concerns remain about the short-term and long-term effects of concussion on brain structure and function, particularly in athletes who experience multiple concussions during their athletic career.

Beyond the risks associated with concussion itself are growing concerns about the effects of repetitive head impact exposure (HIE) from football. Data suggest that HIE may mediate concussion risk in football, wherein higher HIE is associated with increased concussion incidence within a football season.5,6 Repetitive HIE has also been implicated as a possible risk factor for long-range neurologic health problems, including chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) in former football players.7,8

In response to these concerns, sport governing bodies have implemented rule and policy changes to lower concussion risk and reduce HIE in football.9 The National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) and collegiate conferences have modified game aspects with the highest risk of concussion (eg, kickoff) and implemented preseason practice restrictions to reduce concussion and HIE. Prior studies indicate that policy changes have had a variable effect on reducing HIE and concussion incidence in college football.9,10,11

The Concussion Assessment, Research, and Education (CARE) Consortium is a national study of concussion in collegiate student-athletes and military cadets, including the biomechanics of concussion and HIE in football.12 In this Brief Report, we summarize key findings from a CARE Consortium study investigating the incidence of concussion and HIE over the course of the season (ie, preseason vs regular season) and by the nature of football activity (ie, practices vs games) in NCAA college football players.

Methods

The CARE Consortium methods have been detailed elsewhere.12 This study was approved by the Medical College of Wisconsin institutional review board and human research protection office. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. For this study, collegiate football players were instrumented with in-helmet sensor arrays to measure head impact frequency, location, and magnitude during practices and games (Head Impact Telemetry System; Riddell).5,6 Players were prioritized for instrumentation with HITS based on their level of participation (ie, starters prioritized over reserves). Data on HIE and concussion incidence that met the CARE operational definition12 for this report were collected during the 2015 to 2019 football seasons. For inclusion in our analysis, HIE data required confirmation that head impacts with peak linear acceleration greater than 10G were collected during contact football practices or games. The CARE Consortium does not collect epidemiologic data to allow calculation of injury rates per athlete exposures. Our analysis for this report focused primarily on comparing the concussion incidence and HIE in the college football preseason vs regular season and in football practices vs games. Numerical HIE data for all comparisons were summarized as medians and quartiles. Statistical analyses were performed using linear mixed models to take into account repeated observations on athletes within each season. We report estimated means, standard errors, and P values from the linear mixed models. The P value level of significance was .05, and all P values were 2-sided. Analysis of event proportions were adjusted for the length of the preseason and regular season.

Results

Over 5 seasons, 658 football players (all male, mean age [SD], 19.02 [1.25] years) (46.5% of 1416 eligible football players enrolled in the CARE Advanced Research Core [ARC]) at 6 CARE sites were instrumented throughout 1021 athlete-seasons. In total, 528 684 head impacts were recorded and met quality standards for inclusion in our analysis. Players sustained a median of 415 (interquartile range [IQR], 190-727) head impacts per season (preseason and regular season). There were 68 diagnosed concussions among instrumented athletes during football participation (34% of diagnosed concussions among CARE ARC participants from 2015 to 2019).

Preseason vs Regular Season

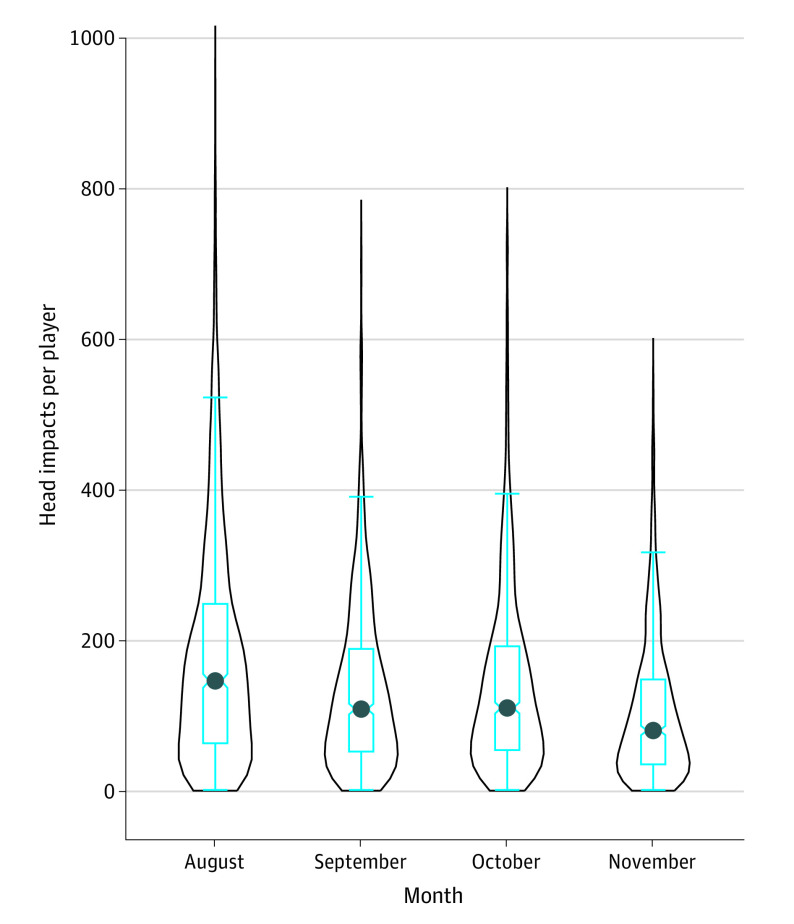

Concussion incidence and HIE were disproportionately higher in the preseason than the regular season. In total, 48.5% of concussions (n = 33) occurred during the preseason, despite preseason accounting for only 20.8% of the full football season (0.059 preseason vs 0.016 regular-season concussions per team per day; mean difference, 0.042; 95% CI, 0.020-0.060; P = .001). Adjusting for different lengths of the preseason and regular season, HIE in preseason (66.7% of all recorded head impacts) occurred at twice the proportion of the regular season (33.3%) (324.9 vs 162.4 impacts per team per day; mean difference, 162.6 impacts; 95% CI, 110.9-214.3; P < .001). Players averaged 44% more head impacts per week during preseason than in the regular season (46.9 vs 32.4 impacts; mean difference, 14.5 impacts; 95% CI, 13.5-15.5; P < .001) (Table). Across all seasons, players sustained 82.5% more head impacts in August (composed mostly of preseason activities) than in November (180.5 vs 98.4 impacts; mean difference, 82.1 impacts; 95% CI, 75.3-88.8), 34.6% more than in September (180.5 vs 127.9 impacts; mean difference, 52.6 impacts; 95% CI, 46.0-59.1) and 32.7% more than in October (180.5 vs 134.5 impacts; mean difference, 46.0 impacts; 95% CI, 39.3-52.7; P < .001) (Figure).

Table. Head Impact Exposure per Player in the Preseason vs Regular Season and in Football Practices vs Games.

| Exposure type | Median (IQR) | Estimated meana (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weekly exposures | |||

| Preseason | 36.0 (14.0-66.3) | 46.9 (45.1-48.6) | <.001 |

| Regular season | 25.0 (10.0-48.0) | 32.4 (30.7-34.0) | |

| Season-long exposures (regular season) | |||

| Practices | 175.0 (76.0-340.5) | 243.2 (230.8-255.7) | <.001 |

| Games | 95.0 (32.0-206.0) | 138.3 (125.3-151.3) |

Abbreviations: HIE, head impact exposure; IQR, interquartile range; LMM, linear mixed model.

Estimated means and 95% confidence intervals from the LMM estimation. Comparison of exposure was conducted by regressing the average daily HIE per team per season on the preseason vs season binary variable: 66.7% in preseason and 33.3% in regular season (P value for the difference between preseason and season <.001). Preseason was defined as the period from the first day of football training through the last day of the week before the week of first scheduled regular season football game; regular season was defined as the period from the first day of the week leading up to the first scheduled game throughout the last day of the regular season. Using these parameters, preseason and regular season are nonoverlapping. Preseason includes practices and intrasquad scrimmages. Regular season includes practices, intrasquad scrimmages, and games.

Figure. Head Impacts per Player per Month.

Data represent impacts per player per month: August (preseason) (mean, 181.1; median, 146.0; interquartile range [IQR], 63.0-247.8), September (mean, 134.1; median, 108.5; IQR, 52.0-188.2), October (mean, 142.2; median, 110.0; IQR, 54.0-192.0), November (mean, 107.1; median, 80.0; IQR, 35.0-148.0; P < .001); P value corresponds to an overall test for the equality across 4 months.

Practice vs Games

Across all 5 seasons, the abundance of concussions and HIE occurred in practices. Including the preseason and regular season, 72% of concussions occurred during football practice and 28% in games (game proportion, 0.28; 95% CI, 0.18-0.40; P < .001). Although head impacts per player per session were higher in games (estimated mean, 19.7 impacts; 95% CI, 18.8-20.6) than in practice (estimated mean, 9.2 impacts; 95% CI, 8.6-9.8) (mean difference, 10.5 impacts; 95% CI, 9.7-11.2; P < .001), 66.9% of all head impacts occurred in practice (262.4 impacts [practices] vs 137.2 impacts [games] per player; mean difference, 125.3 impacts; 95% CI, 110.0-140.6; P < .001). Even within the regular season, median HIE sustained by players during all practices was 84.2% higher than in all games (243.2 vs 138.3 impacts; mean difference, 104.9 impacts; 95% CI, 90.3-119.59; P < .001) (Table).

Discussion

We report analyses from the largest study to our knowledge to date on concussion and HIE in instrumented college football players. These data illustrate several important points critical to understanding the profile of concussion and HIE and to informing strategies to reduce concussion incidence and HIE among college football players. First, concussion incidence and HIE are disproportionately higher in the preseason than the regular season. Although preseason training represents only about 20% of the full football season, it accounts for roughly half of all concussions, and HIE occurs at twice the proportion of the regular season. Second, although per session HIE is higher in games than in practice, the abundance of all concussions (72%) and total HIE (67%) occurs during practices, not games.

There is growing consensus that reducing concussion incidence and HIE has important implications to improving athlete safety in football. To date, NCAA policy changes have had a limited effect in reducing preseason concussion incidence and HIE.11 The most effective prevention strategies will require a multidimensional approach that extends beyond singularly focused policy and will require buy-in from all key stakeholders, including sport governing bodies, institutional athletic administration, coaches, and athletes themselves. Football practice reform to reduce exposure and risk of concussion will undoubtedly require engagement from coaches, who ultimately design and implement drill-specific practice activities.13 Our data support the development of robust educational offerings that should be customized to specific audiences, including coaches, athletic administrators, and players.

There is often natural tension between proposed changes to improve athlete safety and fundamental interest in preserving the competitive nature of football. Achieving both may require alternative training paradigms to maximize competitive readiness of players, while minimizing exposure and risk. The current data suggest that targeted prevention strategies to yield the greatest overall effects toward reducing HIE and concussion incidence without major modification to football game play. While rule changes (eg, targeting penalties) are an important component to protecting athletes during competition, our data suggest modifying preseason training activities and football practice throughout the season could lead to a substantial reduction in overall concussion incidence and HIE. To that end, we offer the following for consideration:

Policy and governance: Sport governing bodies, including the NCAA and major collegiate athletic conferences, are encouraged to explore policy and rule changes to further reduce concussion incidence and HIE, with a particular focus on preseason and regular season football practice guidelines. Policy changes reducing contact practices at the high school level have already been shown to decrease HIE by up to 50%.14

Institutional responsiveness: Data from this study should inform strategic efforts by the NCAA to reduce HIE and concussion in college football. In turn, institutional leaders and coaches should promote educational efforts and modify local training practices to universally reduce concussion incidence and HIE.

Athlete instruction: As we reported previously,15 the largest percentage of variance in HIE during football practice resides at the level of the individual athlete,15 indicating the importance of strategies to reduce HIE in those athletes at highest risk. When available, innovative technologies may provide an effective means for individual player instruction to reduce exposure and associated injury risk.

Monitoring efficacy: Sport governing bodies should collect data to systematically evaluate the effectiveness of policy changes and other prevention strategies in reducing HIE and concussion incidence.

Limitations

In addition to the methodologic strengths of this study, certain limitations should be considered in interpretation and generalization of its findings. Although the HIT System is the most widely used and validated device for measurement of HIE in football, there is potential for some degree of measurement error and the occurrence of false-positive or false-negative recording of impacts.16 Additionally, this study did not involve live or video surveillance to independently verify recorded head impacts. The study sample of 658 players instrumented with the HIT System is, to our knowledge, the largest available, but resource limitations did not allow instrumentation of all rostered players at all ARC sites. Finally, the study included only NCAA Division 1 football players. It is possible that the profile of concussion and HIE in the preseason and in football practice may be different at other competitive levels (eg, youth, high school, and professional).

Conclusions

These findings from the CARE Consortium help inform a powerful opportunity to do the greatest good toward reducing concussion incidence and HIE in college football players through a combination of policy and education while still maintaining the competitive nature of game play. If effective, similar strategies could be implemented to prevent concussion and HIE across all levels of competitive football (youth, high school, and professional) and other sports.

References:

- 1.McCrory P, Meeuwisse WH, Aubry M, et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport: the 4th International Conference on Concussion in Sport held in Zurich, November 2012. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47(5):250-258. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCrea M, Guskiewicz KM, Marshall SW, et al. Acute effects and recovery time following concussion in collegiate football players: the NCAA Concussion Study. JAMA. 2003;290(19):2556-2563. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.19.2556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guskiewicz KM, McCrea M, Marshall SW, et al. Cumulative effects associated with recurrent concussion in collegiate football players: the NCAA Concussion Study. JAMA. 2003;290(19):2549-2555. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.19.2549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCrea M, Broglio S, McAllister T, et al. ; CARE Consortium Investigators . Return to play and risk of repeat concussion in collegiate football players: comparative analysis from the NCAA Concussion Study (1999-2001) and CARE Consortium (2014-2017). Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(2):102-109. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2019-100579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stemper BD, Shah AS, Harezlak J, et al. ; CARE Consortium Investigators . Comparison of head impact exposure between concussed football athletes and matched controls: evidence for a possible second mechanism of sport-related concussion. Ann Biomed Eng. 2019;47(10):2057-2072. doi: 10.1007/s10439-018-02136-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rowson S, Campolettano ET, Duma SM, et al. Accounting for variance in concussion tolerance between individuals: comparing head accelerations between concussed and physically matched control subjects. Ann Biomed Eng. 2019;47(10):2048-2056. doi: 10.1007/s10439-019-02329-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mez J, Daneshvar DH, Kiernan PT, et al. Clinicopathological evaluation of chronic traumatic encephalopathy in players of American football. JAMA. 2017;318(4):360-370. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.8334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stern RA, Adler CH, Chen K, et al. Tau positron-emission tomography in former National Football League players. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(18):1716-1725. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1900757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wiebe DJ, D’Alonzo BA, Harris R, Putukian M, Campbell-McGovern C. Association between the experimental kickoff rule and concussion rates in Ivy League football. JAMA. 2018;320(19):2035-2036. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.14165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stemper BD, Shah AS, Harezlak J, et al. ; And the CARE Consortium Investigators . Repetitive head impact exposure in college football following an NCAA rule change to eliminate two-a-day preseason practices: a study from the NCAA-DoD CARE Consortium. Ann Biomed Eng. 2019;47(10):2073-2085. doi: 10.1007/s10439-019-02335-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stemper BD, Shah AS, Mihalik JP, et al. . Head impact exposure in college football following a reduction in preseason practices. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2020. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000002283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Broglio SP, McCrea M, McAllister T, et al. ; CARE Consortium Investigators . A national study on the effects of concussion in collegiate athletes and US military service academy members: the NCAA-DoD Concussion Assessment, Research and Education (CARE) consortium structure and methods. Sports Med. 2017;47(7):1437-1451. doi: 10.1007/s40279-017-0707-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Asken BM, Brooke ZS, Stevens TC, et al. Drill-specific head impacts in collegiate football practice: implications for reducing “friendly fire” exposure. Ann Biomed Eng. 2019;47(10):2094-2108. doi: 10.1007/s10439-018-2088-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Broglio SP, Williams RM, O’Connor KL, Goldstick J. Football players’ head-impact exposure after limiting of full-contact practices. J Athl Train. 2016;51(7):511-518. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-51.7.04 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campolettano ET, Rowson S, Duma SM, et al. Factors affecting head impact exposure in college football practices: a multi-institutional study. Ann Biomed Eng. 2019;47(10):2086-2093. doi: 10.1007/s10439-019-02309-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Connor KL, Rowson S, Duma SM, et al. Head-impact–measurement devices: a systematic review. J Athl Train. 2017;52(3):206-227. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050.52.2.05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]