Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate the independent association between symptom burden and physical function impairment in older adults with cancer.

Design:

Cross-sectional.

Setting:

Two university-based geriatric oncology clinics.

Participants:

Patients with cancer aged ≥65 years who underwent evaluation with geriatric assessment (GA).

Methods:

Symptom burden was measured as summary score of severity ratings (range 0-10) of ten commonly reported symptoms using a Clinical Symptom Inventory (CSI). Functional impairment was defined as presence of ≥1 Instrumental Activity of Daily Living (IADL) impairment, any significant physical activity limitation on Medical Outcomes Survey (MOS), ≥1 any fall in the previous six months, or a Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) score ≤ 9. Multivariate analysis evaluated the association between symptom burden and physical function impairment, adjusting for other clinical and sociodemographic variables.

Results:

From 2011-2015, 359 patients with cancer with median age of 81 years (range 65-95) consented. The mean CSI score was 23.2±20.5 with an observed range of 0-90. Patients in the highest quartile of symptom burden (N=91; CSI score: 52±13) had a higher prevalence of IADL impairment (91% vs. 51%), physical activity limitation (93% vs. 65%), falls (55% vs. 21%), and SPPB score ≤ 9 (92% vs. 69%) (all p-values <0.01) when compared to those in the bottom quartile (N=81; CSI score: 2±2). With each unit increase in CSI score, the odds of having IADL impairment, physical activity limitations, falls, and SPPB scores ≤ 9 increased by 4.8%, 4.4%, 2.9% and 2.5% respectively (p<0.05 for all results).

Conclusions:

In older patients with cancer, higher symptom burden is associated with functional impairment. Future studies are warranted to evaluate if improved symptom management can improve function in older cancer patients.

Keywords: physical function, symptoms, geriatric assessment, cancer, older patients

INTRODUCTION:

Most older patients with cancer experience a large number of physical and psychological symptoms as a result of the disease and its treatments.1 Commonly reported symptoms include fatigue, pain, drowsiness, insomnia, dyspnea, and anorexia.2,3 Compared to individuals without cancer, patients with cancer have a high prevalence of symptoms such as loss of sensation abnormality, pain, and fatigue which are significantly associated with worse physical function.4 Prior work has shown that in younger patients with cancer, high symptom burden can negatively affect physical function, quality of life, and survival.5,6 Impaired physical function has been shown to predict worse outcomes such as higher mortality and lower quality of life in community-dwelling older adults7 as well as in individuals with cancer.8,9

In oncology clinical trials the most frequently used outcome variables are progression-free and overall survival. However, older patients with cancer often prioritize preservation of physical function over survival,10 limiting the applicability of clinical trial data for use in treatment decision-making.11 Additionally, oncology clinical trials tend to include a “fitter” population of patients and may not be generalizable to more frail older patients with cancer. Thus, physical function limitation should be evaluated as one of the outcomes in older patients with cancer while choosing appropriate treatment options.11

Older patients constitute a significant group of patient population in oncology practices, and require special consideration for symptom assessment and management.12 Despite this, the majority of studies on symptom burden focus on younger adults with cancer or enroll a more general group of older patients with cancer rather than those referred to a geriatric oncology clinics who may be frailer.13–15 A better understanding of relationship between symptom burden and physical function may allow identifying older patients who may benefit from symptom management and interventions to prevent/postpone decline in physical function. Moreover, there is heterogeneity in the methods used to evaluate physical function impairment in patients with cancer, with most studies using patient-reported measures of physical function,15,16 which may underestimate physical function limitations.17 Validated objective measures of physical function such as the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) may further clarify the relationship between symptom burden and physical function in older adults with cancer. The purpose of this study is to examine the relationship between symptom burden and physical function in older adults with cancer seen in geriatric oncology clinics, evaluated through a variety of validated patient-reported and objective measures of physical function. We hypothesized that higher symptom burden is independently associated with loss of physical function. Establishing this relationship would inform multi-component clinical pathways and interventions for physical function in older patients with cancer who have burdensome symptoms.18

METHODS:

Setting and sample:

Our sample included patients aged 65 and over referred to the Specialized Oncology Care and Research in the Elderly (SOCARE) geriatric oncology clinics at two sites (University of Rochester and University of Chicago) between May 2011 and October 2015. The SOCARE clinics are multidisciplinary geriatric oncology consultative clinics where older patients with cancer are referred for GA, consultation, and care management. Medical oncologists referred patients to the geriatric oncology clinics who needed evaluation for starting new treatment or had age-related concern during on-going treatment. Further details on the clinic structure, care processes, services provided, and patient consent are available elsewhere.19 Human subject approval was obtained from the institutional review boards of both institutions.

Measures:

Independent Variable:

Symptom burden was measured using the Clinical Symptom Inventory (CSI).12 The CSI assesses ten symptoms (pain at its worst, other pain, distress, memory problem, feeling drowsy, dyspnea, sleep problem, anorexia, dry mouth, feeling sad) rated on a 0-10 scale, with 0 indicating that the symptom is not present and 10 indicating the symptom is “as bad as can be imagined”.3 Total CSI score range is 0-100.

Outcome Variables:

The outcomes of interest were physical function measures captured in the GA including: Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) status measured by difficulty using a telephone, managing money, managing medications, grocery shopping, preparing meals, doing housework, and using transportation; 20 Medical Outcomes Survey (MOS) physical activity (PA) survey eliciting significant limitations in performing ten activities such as lifting or carrying groceries, climbing several flights of stairs, and walking more than one mile;21 Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) as an objective measure of physical performance including lower-extremity physical function by performing 4-meter walk, repeated chair stands and a balance test; 9 and falls in the previous six months. Four separate measures of functional impairment were created based on the above instruments: 1 -any assistance required for IADL task, 2- any significant limitation on MOS PA survey, 3- a history of at least 1 fall in the previous 6 months, and 4 - SPPB score ≤9.22

Demographic and clinical variables:

We collected data on age, race (white, non-white), education (<high school, high school, >high school), and marital status (married, widowed, single/separated/divorced). The clinical characteristics included depression (scores ≥5 on 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale)23, non-cancer comorbidities (presence of at least one illness that affected respondents a “great deal”, or at least three illnesses that affected them “somewhat” on the modified Older Americans Resources and Services Questionnaire Physical Health subscale), cancer type (gastrointestinal, genitourinary, lung, and others) and cancer stage (limited, advanced, and unknown).

Statistical analysis:

Patient demographics, clinical characteristics, and functional measures were summarized using descriptive statistics as means (± standard deviation) or frequencies (%), as appropriate. Missing values of the study variables were tested using Little’s missing-at-random test.24 Imputation was not undertaken for data missing-at-random (available case analysis). Bivariate analyses using t-test for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables were performed to test the associations between the predictors and covariates with each of the functional outcomes (i.e., IADL, MOS physical activity, falls and SPPB). Separate multivariate logistic regression models were used to assess the independent association between symptom burden score and each functional outcomes, after adjusting for covariates based on clinical relevance in literature review and significant (p <0.05) association in bivariate analyses. Model fit was evaluated using the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit test.25 To determine whether greater symptom burden was associated with functional impairment, we also compared the presence of each functional impairment measure by top versus bottom quartile of the total CSI score. All statistical tests were two-tailed with p-values of <0.05 considered statistically significant and were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS:

Characteristics of the study sample (Table 1):

Table 1:

Patient characteristics (N=359)

| Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 163 | 45.40 |

| Male | 196 | 54.60 |

| Race | ||

| White | 265 | 74.44 |

| Black/African American | 77 | 21.94 |

| Others | 9 | 3.62 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 181 | 51.42 |

| Widowed | 107 | 30.40 |

| Divorced/separated/single | 64 | 18.18 |

| Education | ||

| <High School | 168 | 48 |

| =High School | 105 | 30 |

| >High School | 77 | 22 |

| Depressiona | ||

| No | 244 | 69.12 |

| Yes | 109 | 30.88 |

| Comorbidityb | ||

| Absent | 108 | 30.51 |

| Present | 246 | 69.49 |

| Total number of comorbidities | ||

| 0 | 30 | 8.48 |

| 1 | 41 | 11.55 |

| 2 | 54 | 15.18 |

| 3 | 57 | 15.92 |

| 4 | 55 | 15.46 |

| 5 | 43 | 12.11 |

| 6 | 39 | 10.99 |

| 7 | 20 | 5.69 |

| 8 | 11 | 3.17 |

| 9 | 2 | 0.66 |

| 10 | 2 | 0.66 |

| Symptomsc | ||

| Feeling drowsy | 220 | 63.77 |

| Memory problem | 215 | 62.14 |

| Pain at its worst | 191 | 55.52 |

| Dry mouth | 187 | 54.36 |

| Disturbed Sleep | 179 | 53.12 |

| Distress | 179 | 52.65 |

| Dyspnea | 177 | 52.06 |

| Other pain | 162 | 51.27 |

| Feeling sad | 175 | 50.87 |

| Lack of Appetite | 172 | 49.86 |

| Cancer type | ||

| Lung | 66 | 18.38 |

| GI | 92 | 25.63 |

| GU | 106 | 29.53 |

| Others | 95 | 26.46 |

| Cancer stage | ||

| Limited | 133 | 37.05 |

| Advanced | 171 | 47.63 |

| Unknown | 55 | 15.32 |

| IADL limitationsd | ||

| No | 112 | 31.55 |

| Yes | 243 | 68.45 |

| Short Physical Performance Batterye | ||

| SPPB>9 | 72 | 21.62 |

| SPPB≤9 | 261 | 78.38 |

| Physical Activity limitationsf | ||

| No | 77 | 22.19 |

| Yes | 270 | 77.81 |

| Fallsg | ||

| No | 218 | 62.11 |

| Yes | 133 | 37.89 |

SD - Standard Deviation, GI - Gastrointestinal, GU - Genitourinary

Depression was defined as present if patients scored ≥ 5 on the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale.

Comorbidity was defined as present if patients reported at least one illness that affected them by a “great deal”, or at least three illnesses that affected them by “somewhat” on the modified Older Americans Resources and Services Questionnaire Physical Health subscale.

Symptom frequency is the number of patients who reported the symptoms and percentage is calculated based on the number of patients who responded to the corresponding symptom items.

Instrumental Activities of Daily living (IADL) limitations was defined as patients reporting needing assistance with at least one of the IADLs (use of telephone, managing money, preparing meals, shopping for groceries, doing housework, and transportation)

Short Physical Performance battery based physical function limitation was defined as a score of 9 or less out of a total score of 12 on SPPB.

Physical activity limitations was present if patients self-report of at least one activity that was “limited a lot” on the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form Questionnaire.

Falls in the preceding 6 months

Of the patients referred to the two SOCARE clinics during the study period, 359 patients had values for the pre-determined study variables. The average age was 81 years (range 65-95); 55% were male, 74% were white, 51% were married, and 22% had at least a high school education. Most had genitourinary (30%), gastrointestinal (26%) or lung (18%) cancers. Nearly half the study population had an advanced cancer stage. At the time of GA, 69% (215/310) had received prior surgery, 41% (130/320) received radiation, and 32% (99/312) had received chemotherapy. Approximately 70% had non-cancer comorbidities with most prevalent being high blood pressure (59%), arthritis (58%), and heart disease (28.5%). Feeling drowsy (64%), memory problem (62%), and pain (56%) were the most commonly reported symptoms; the mean (±SD) CSI score was 23.2±20.6 (range: 0-90)

Association between symptom burden and physical function

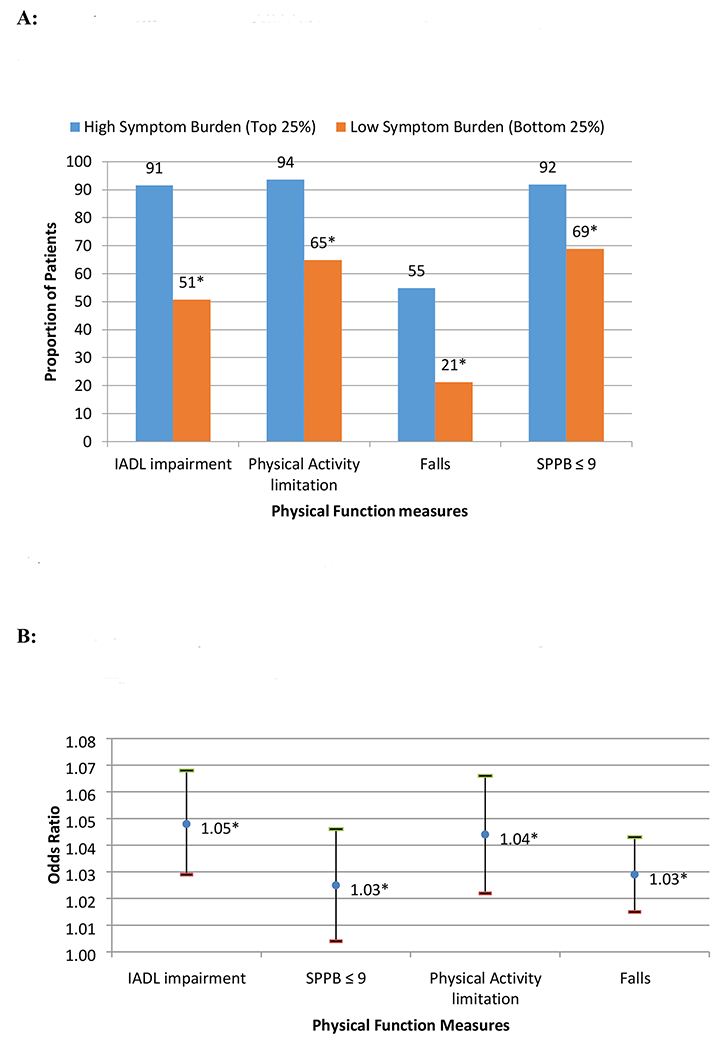

The study sample had significant physical impairment (Table 1). For clinical relevance, patients in the highest quartile of symptom burden (N=91; CSI score: 52±13) were compared to those in the bottom quartile (N=81; CSI score: 2±2). Figure 1A shows that those in the top quartile had a higher prevalence of IADL impairment (91% vs. 51%), physical activity limitation (93% vs. 65%), and falls (55% vs. 21%); and SPPB scores ≤ 9 (92% vs. 69%) (all p-values <0.01).

Figure 1 –

A. Physical function impairments by highest versus lowest quartile of symptom burden scores. *All test of proportions p-values <0.05. B. Multivariate analyses showing associations between symptom burden and physical function impairment measures. Covariates in each regression models: Age, Gender, Race, Marital Status, Education, Depression, Comorbidity, Cancer types, and Cancer Stage. *p-value < 0.05

In bivariate analyses, patients who reported higher symptom burden scores had a higher prevalence of impaired physical function. For example, patients who required assistance with IADLs reported higher symptom burden scores than those who were independent in IADLs (27.97 ± 21.47 vs. 12.89 ± 13.41, p<0.01) (Table 2). In multivariate analyses, after adjusting for age, gender, race, education, marital status, depressive symptoms (GDS score), non-cancer comorbidities, cancer type and stage, the associations between symptom burden and functional limitations persisted (Supplemental Table). As shown in Figure 1B, each unit increase in symptom burden score is associated with greater odds of IADL impairment (4.8%), physical activity limitations (4.4%), falls (2.9%), and SPPB scores ≤ 9 (2.5%) (p<0.05 for all results). Little’s missing-at-random test on the variables included in the multivariate analysis showed p-values >0.05, suggesting no statistically significant patterns in the missing data (Results not shown).

Table 2:

Symptom burden score for patients with and without physical function impairment

| Functional Measures | Impaired | Not Impaired | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSI Mean | CSI SD | CSI Mean | CSI SD | p-value | |

| IADL | 27.97 | 21.47 | 12.89 | 13.41 | <0.001 |

| SPPB≤9 | 25.28 | 21.29 | 14.37 | 15.01 | <0.001 |

| Physical Activity | 26.36 | 20.98 | 12.58 | 13.11 | <0.001 |

| Falls | 29.89 | 20.95 | 19.01 | 19.03 | <0.001 |

IADL - Instrumental Activities of Daily Living, PA - Physical Activity, SPPB - Short Physical Performance Battery, CSI – Clinical Symptom Inventory

DISCUSSION:

In this sample of older adults with cancer, rates of physical function impairment ranged from 39% to 78%, depending on the physical function measure. Functional impairment was more prevalent when patients reported greater symptom burdens (top quartile) compared to those with less symptom burden (bottom quartile). After adjusting for covariates, a higher symptom burden was found to be associated with impairments in all four measures of physical function.

Physical functioning is critical for older adults with cancer to optimize independence.26 Furthermore, functional impairment has been shown to predict worse outcomes such as lower survival and poor quality of life in older patients with cancer who are undergoing cancer treatment.9 Compared to older patients without cancer, those with cancer are at high risk of decline in functional status due to intensive treatments and comorbidities.27 More recently, a geriatric oncology guideline from the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) recommends IADL evaluation and a question about falls for all older adults considering or receiving chemotherapy.28 Our study findings of high prevalence of functional impairment, across both objective and subjective physical function measures, in a large sample of older patients with cancer referred for geriatric oncology consultation highlight the need to incorporate physical function assessment in routine care to help guide cancer treatment recommendations in this patient population.29 Our findings further indicate that cancer type was not associated with physical function outcomes after controlling for covariates. While previous cross-sectional studies have shown higher physical function impairment in lung cancer patients versus other cancers30, recent prospective studies have also suggested findings similar to our study such that function decline or trajectory are not associated with the type of cancer diagnosis, but may be associated with type of cancer treatments and new cancer diagnosis.31,32 Future studies should investigate whether the association between symptoms burden and physical function is moderated by cancer type.

This study expands upon prior literature which has demonstrated an association between symptom burden and physical function in younger patients with cancer.15 In a longitudinal study of 93 patients (average age 55.4 years), Dodd et al. found that between two consecutive time periods in the study, cancer-related symptoms of pain and fatigue contributed to 10.7% and 7.3% respectively decline in Karnofsky scores.14 We also found an independent association of symptom burden with physical impairment after adjusting for covariates. Specific symptoms such as depressive symptoms have been shown to be associated with lower physical function in older patients with non-cancer chronic conditions such as osteoarthritis, heart failure and diabetes.33–35 While we did not conduct a symptom cluster analysis, a higher prevalence of feeling drowsy, memory problems, and pain symptoms out of total 10 symptoms in the study sample may reflect priority cancer-related symptoms clusters associated with physical function that could be investigated as potential target for interventions in older patients with cancer. Although we cannot infer causation in our cross-sectional study, prior work using longitudinal study design in younger cancer population has established a strong basis for symptoms as causal factors in physical function impairment.14–16 Moreover, older adults often have other comorbidities that may cause pre-existing impairments in strength and balance, rendering them vulnerable to further decline with cancer- and cancer treatment-related symptom burden.36 Kurtz and colleagues evaluated 420 patients age 65-98 years with cancer and found that pre-diagnosis physical functioning, symptom severity, and days since surgery were significant predictors of subsequent deficit in physical function, measured by MOS SF-36 survey.37 The majority of these studies used self-reported general measures of physical function assessment38, our study adds to the literature by showing association between symptom burden and lower physical function measured using multiple methods, including an objective measure of physical performance, the SPPB.

Our study finding of association of symptom burden with physical function could help health care providers target efforts to monitor patients with higher symptom burden and consider physical function as effectiveness indicator of interventions targeting symptom burden. Kroenke et al. evaluated the impact of longitudinal symptom burden trajectories on patient-reported physical function outcomes in relatively young patients with cancer (age: 58.8 years, range- 23-96) enrolled in a clinical trial.16 They reported that reduction in symptom burden predicted improvement in functional status and decline in disability. This suggests that it may be possible to modify the impact of symptom burden on physical function outcomes with improvements in symptom control. Early supportive care focusing on comprehensive symptom control through lifestyle management may maximize physical function and improve quality of life of older patients with cancer.39 Symptoms have also been shown to moderate the effect of cognitive behavioral theory guided self-efficacy enhancing intervention to improve the physical function of cancer patients.40,41 Based on the study findings of association between higher symptom burden and greater functional limitation, oncologists caring for older cancer patients could target such interventions towards patients with different levels of symptom burden and increase the effectiveness of intervention on physical functioning. The study results have the potential to guide clinical care at the intersection between oncology, palliative care, and geriatrics. For example, geriatricians who best recognize functional impairment should also attend to symptoms that are burdensome since symptoms and functional impairment are associated with one another, in addition to the oncologists and palliative care physicians who have more limited training in evaluating and intervening on age-related conditions in older patients with cancer.18

This study has several strengths, including a large sample of older adults with cancer who underwent GA using standardized tools including subjective and objective measures of physical function at two different geriatric oncology clinics. The study also has limitations. The cross-sectional design precludes causal inference. Since the patients included in the study consists of those referred to the geriatric oncology clinics at the two sites, there is a potential of selection and referral bias arising from physician-, patient-, disease- and other related factors. It included patients at any time point of their cancer treatment, some of whom had cancer surgery, radiation, hormonal therapy or chemotherapy which can affect their symptom burden and functional status.10 A symptom inventory more specific to patients on cancer therapy may clarify which symptoms are associated with the most impairment and are highest priorities for intervention. Due to limited availability of cancer treatment information in our study population, the effect of treatment on outcome was not evaluated in multivariate models which may bias the estimates. Future studies could evaluate a larger cohort of older patients with cancer in different health care settings and include a longitudinal design with a broad array of risk factors for symptom burden and functional limitations.

In conclusion, in real-world sample of older patients with cancer referred for geriatric oncology evaluation, we observe a significant association of higher symptom burden with physical functional impairment. While caring for older patients with cancer, it is important for oncologists, geriatricians, and palliative care providers to consider targeting specific interventions towards patients with different levels of symptom burden to improve physical function. Our findings could inform the priorities for future research to identify causal mechanisms between symptom burden and physical function and evaluate if optimal symptom management can improve physical function in older patients with cancer.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Table -

Multivariable regression models showing association between symptoms score and physical function measures

Impact Statement:

We certify that this work is novel clinical research. The potential impact of this research on clinical care includes the following: our study findings of high prevalence of functional impairment, in a relatively large sample of older patients with cancer highlight the need to incorporate physical function assessment in routine care to help guide treatment recommendations in this patient population. Moreover, the association of symptom burden with physical function could help health care providers target efforts to monitor patients with higher symptom burden and consider physical function as an outcome for interventions targeting symptom burden.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

Financial Disclosure: The work was funded through UG1 CA189961, K24 AG056589 (Mohile), through the Wehrheim endowment (Mohile), and through generous donors to the Wilmot Cancer Institute geriatric oncology philanthropy fund. All statements in this report, including its findings and conclusions, are solely those of the authors, do not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Sponsor’s role: None

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts.

REFERENCES:

- 1.Rao A, Cohen HJ. Symptom management in the elderly cancer patient: fatigue, pain, and depression. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2004(32):150–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yates P, Miaskowski C, Cataldo JK, et al. Differences in Composition of Symptom Clusters Between Older and Younger Oncology Patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;49(6):1025–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reilly CM, Bruner DW, Mitchell SA, et al. A literature synthesis of symptom prevalence and severity in persons receiving active cancer treatment. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(6):1525–1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang IC, Hudson MM, Robison LL, Krull KR. Differential Impact of Symptom Prevalence and Chronic Conditions on Quality of Life in Cancer Survivors and Non-Cancer Individuals: A Population Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26(7):1124–1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cleeland CS. Symptom burden: multiple symptoms and their impact as patient-reported outcomes. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2007(37):16–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang XS, Shi Q, Lu C, et al. Prognostic value of symptom burden for overall survival in patients receiving chemotherapy for advanced nonsmall cell lung cancer. Cancer. 2010;116(1):137–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen C, Sia I, Ma HM, et al. The synergistic effect of functional status and comorbidity burden on mortality: a 16-year survival analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e106248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown JC, Harhay MO, Harhay MN. Patient-reported versus objectively-measured physical function and mortality risk among cancer survivors. J Geriatr Oncol. 2016;7(2):108–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verweij NM, Schiphorst AH, Pronk A, van den Bos F, Hamaker ME. Physical performance measures for predicting outcome in cancer patients: a systematic review. Acta Oncol. 2016;55(12):1386–1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Derks MG, de Glas NA, Bastiaannet E, et al. Physical Functioning in Older Patients With Breast Cancer: A Prospective Cohort Study in the TEAM Trial. Oncologist. 2016;21(8):946–953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wedding U, Pientka L, Hoffken K. Quality-of-life in elderly patients with cancer: a short review. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43(15):2203–2210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mohile SG, Heckler C, Fan L, et al. Age-related Differences in Symptoms and Their Interference with Quality of Life in 903 Cancer Patients Undergoing Radiation Therapy. J Geriatr Oncol. 2011;2(4):225–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Magnuson A, Allore H, Cohen HJ, et al. Geriatric assessment with management in cancer care: Current evidence and potential mechanisms for future research. J Geriatr Oncol. 2016;7(4):242–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dodd MJ, Miaskowski C, Paul SM. Symptom clusters and their effect on the functional status of patients with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2001;28(3):465–470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Given BA, Given CW, Sikorskii A, Hadar N. Symptom clusters and physical function for patients receiving chemotherapy. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2007;23(2):121–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kroenke K, Johns SA, Theobald D, Wu J, Tu W. Somatic symptoms in cancer patients trajectory over 12 months and impact on functional status and disability. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(3):765–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reuben DB, Seeman TE, Keeler E, et al. Refining the categorization of physical functional status: the added value of combining self-reported and performance-based measures. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59(10):1056–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Magnuson A, Canin B, van Londen GJ, Edwards B, Bakalarski P, Parker I. Incorporating Geriatric Medicine Providers into the Care of the Older Adult with Cancer. Current oncology reports. 2016;18(11):65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gewandter JS, Dale W, Magnuson A, et al. Associations between a patient-reported outcome (PRO) measure of sarcopenia and falls, functional status, and physical performance in older patients with cancer. J Geriatr Oncol. 2015;6(6):433–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9(3):179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stewart AL, Hays RD, Ware JE Jr. The MOS short-form general health survey. Reliability and validity in a patient population. Med Care. 1988;26(7):724–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loh KP, Pandya C, Zittel J, et al. Associations of sleep disturbance with physical function and cognition in older adults with cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(10):3161–3169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lyness JM, Noel TK, Cox C, King DA, Conwell Y, Caine ED. Screening for depression in elderly primary care patients. A comparison of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale and the Geriatric Depression Scale. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(4):449–454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Little RJA. A Test of Missing Completely at Random for Multivariate Data with Missing Values. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1988;83(404):1198–1202. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lemeshow S, Hosmer DW Jr. A review of goodness of fit statistics for use in the development of logistic regression models. Am J Epidemiol. 1982;115(1):92–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tarasenko Y, Chen C, Schoenberg N. Self-Reported Physical Activity Levels of Older Cancer Survivors: Results from the 2014 National Health Interview Survey. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(2):e39–e44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petrick JL, Reeve BB, Kucharska-Newton AM, et al. Functional status declines among cancer survivors: trajectory and contributing factors. J Geriatr Oncol. 2014;5(4):359–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mohile SG, Dale W, Somerfield MR, et al. Practical Assessment and Management of Vulnerabilities in Older Patients Receiving Chemotherapy: ASCO Guideline for Geriatric Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2018:JCO2018788687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohile SG, Velarde C, Hurria A, et al. Geriatric Assessment-Guided Care Processes for Older Adults: A Delphi Consensus of Geriatric Oncology Experts. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2015;13(9):1120–1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kurtz ME, Kurtz JC, Stommel M, Given CW, Given B. Loss of physical functioning among geriatric cancer patients: relationships to cancer site, treatment, comorbidity and age. Eur J Cancer. 1997;33(14):2352–2358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kenis C, Decoster L, Bastin J, et al. Functional decline in older patients with cancer receiving chemotherapy: A multicenter prospective study. J Geriatr Oncol. 2017;8(3):196–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wong ML, Paul SM, Mastick J, et al. Characteristics Associated With Physical Function Trajectories in Older Adults With Cancer During Chemotherapy. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;56(5):678–688 e671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Caruso LB, Silliman RA, Demissie S, Greenfield S, Wagner EH. What can we do to improve physical function in older persons with type 2 diabetes? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55(7):M372–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vaccarino V, Kasl SV, Abramson J, Krumholz HM. Depressive symptoms and risk of functional decline and death in patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38(1):199–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McDonough CM, Jette AM. The contribution of osteoarthritis to functional limitations and disability. Clin Geriatr Med. 2010;26(3):387–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garman KS, Pieper CF, Seo P, Cohen HJ. Function in elderly cancer survivors depends on comorbidities. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58(12):M1119–1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kurtz ME, Kurtz JC, Stommel M, Given CW, Given B. Physical functioning and depression among older persons with cancer. Cancer Pract. 2001;9(1):11–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bellury L, Pett MA, Ellington L, Beck SL, Clark JC, Stein KD. The effect of aging and cancer on the symptom experience and physical function of elderly breast cancer survivors. Cancer. 2012;118(24):6171–6178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pergolotti M, Lyons KD, Williams GR. Moving beyond symptom management towards cancer rehabilitation for older adults: Answering the 5W’s. J Geriatr Oncol. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Doorenbos A, Given B, Given C, Verbitsky N. Physical functioning: effect of behavioral intervention for symptoms among individuals with cancer. Nurs Res. 2006;55(3):161–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kenzik KM, Morey MC, Cohen HJ, Sloane R, Demark-Wahnefried W. Symptoms, weight loss, and physical function in a lifestyle intervention study of older cancer survivors. J Geriatr Oncol. 2015;6(6):424–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Table -

Multivariable regression models showing association between symptoms score and physical function measures