Phase change materials help realize voltage tunable spin dynamics.

Abstract

Controlling magnetization dynamics is imperative for developing ultrafast spintronics and tunable microwave devices. However, the previous research has demonstrated limited electric-field modulation of the effective magnetic damping, a parameter that governs the magnetization dynamics. Here, we propose an approach to manipulate the damping by using the large damping enhancement induced by the two-magnon scattering and a nonlocal spin relaxation process in which spin currents are resonantly transported from antiferromagnetic domains to ferromagnetic matrix in a mixed-phased metallic alloy FeRh. This damping enhancement in FeRh is sensitive to its fraction of antiferromagnetic and ferromagnetic phases, which can be dynamically tuned by electric fields through a strain-mediated magnetoelectric coupling. In a heterostructure of FeRh and piezoelectric PMN-PT, we demonstrated a more than 120% modulation of the effective damping by electric fields during the antiferromagnetic-to-ferromagnetic phase transition. Our results demonstrate an efficient approach to controlling the magnetization dynamics, thus enabling low-power tunable electronics.

INTRODUCTION

Damping, which is a fundamental parameter that defines the magnetization relaxation process, plays a crucial role in the performances of spintronics, magnetic sensors, and magnon devices (1–6). For example, the spin transfer torque magnetic random access memory (STT-MRAM) devices favor a low damping parameter for a small critical switching current, while a high damping parameter is also desired for reaching an ultrafast switching speed (3). To meet both criteria in STT-MRAM and to achieve tunable microwave and magnon devices, dynamic manipulation of magnetic damping is critical.

The current-induced spin-orbit torque generated by spin-Hall source materials can be used to modulate the effective magnetic damping parameter in ferromagnets (4, 7, 8). The more energy-efficient approach, namely, voltage control of magnetic damping, has been demonstrated with electric field effects (9, 10) and piezo strain effects (11–14) by modulating the intrinsic part of the damping (Gilbert damping) in various material systems; however, their tunability has been limited. The extrinsic part of the damping can be contributed from the spin pumping in ferromagnets/spin sink bilayer structures. In such damping process, the angular momentum is transferred from the ferromagnet into the spin sink at ferromagnetic resonance (FMR) (2, 15). It has been shown recently that spin pumping can occur laterally in FeRh (16), a metallic alloy that has ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic phases coexisting during the metamagnetic phase transition, where the spin current is transported from its ferromagnetic domain into the surrounding antiferromagnetic spin sink (as shown schematically in Fig. 1A). During the antiferromagnetic-to-ferromagnetic phase transition of FeRh, the damping would change drastically because the lateral spin pumping is sensitive to the fraction of the ferromagnetic phases. This suggests an approach to modulate the damping dynamically by small external perturbations. Here, we demonstrate the modulation of the lateral spin pumping in epitaxial thin films of FeRh on piezoelectric substrates by controlling the ferromagnetic phase fraction using the electric field–induced strain, which results in a reversible modulation of the effective magnetic damping of more than 120% during the phase transition. This is evidenced by the strong correlation between the electric-field–induced magnetic damping and the change of ferromagnetic domain fraction, both probed by the FMR. Our analytical model suggests that the spin pumping is the dominant contribution to the damping enhancement, demonstrating the role of mixed-phase coexistence, more importantly the coupling between the two phases, in achieving high tunability of damping. This study not only provides an efficient approach to control the magnetic damping that is useful for tunable magnetic devices but also demonstrates the FeRh/piezoelectric heterostructure to be a good platform to explore the spin dynamics and the interfacial spin transport.

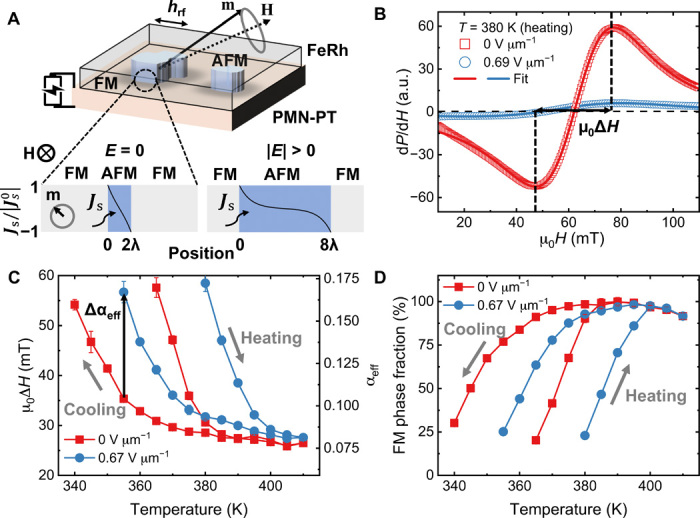

Fig. 1. Tuning mechanism of the magnetic damping in FeRh/PMN-PT.

(A) Schematic illustration of the FeRh/PMN-PT heterostructure where the antiferromagnetic (AFM) domains embedded in the ferromagnetic (FM) matrix of FeRh were driven into FMR by microwave magnetic fields hrf. The electric field (E) was applied across the thickness direction of the PMN-PT substrate to induce piezo strains. Bottom schematics show the isothermal growth of antiferromagnetic domains in the FeRh under relatively large electric fields. The curves in the blue region represents the profile of spin current density across the lateral direction of the antiferromagnetic domain, where || is the magnitude of spin current density at the ferromagnetic/antiferromagnetic interface; λ is the spin diffusion length in the antiferromagnetic domain. a.u., arbitrary units. (B) FMR spectra and the fittings of the FeRh/PMN-PT at 380 K during heating with applied electric fields of 0 (red) and 0.67 V μm−1 (blue), respectively. (C) Temperature dependence of the resonance linewidth μ0ΔH and the corresponding effective magnetic damping αeff with applied electric fields of 0 (red) and 0.67 V μm−1 (blue), respectively. (D) Temperature dependence of the ferromagnetic phase fraction with applied electric fields of 0 (red) and 0.67 V μm−1 (blue), respectively.

FeRh with the ordered CsCl-type structure exhibits a first-order metamagnetic phase transition from an antiferromagnetic order with a G-type spin structure to a ferromagnetic order above the room temperature (17). The transport (18, 19), spin and orbital moment (20–22), FMR (16, 23, 24), and the ultrafast dynamics (25, 26) have been investigated in FeRh thin films across the phase transition, in which the unique magnetic phase transition and the coexisting phases trigger tremendous interest in heat-assisted magnetic recording (27–29), voltage-controlled magnetism (30), and antiferromagnetic spintronics (31–36). The magnetic phase transition is accompanied by a volume expansion of 1%, suggesting strong coupling between the magnetic ordering and the unit cell structure (37–41). By using piezoelectric substrates, electric-field control of the magnetic phase transition in FeRh has been realized (42), probed by the electric field dependence of magnetization (43–47) and resistivity measurements (48, 49).

RESULTS

In this study, highly [001]-oriented FeRh thin films were grown on (001)-oriented PMN-PT (0.72PbMg1/3Nb2/3O3-0.28PbTiO3) substrates by DC magnetron sputtering (Materials and Methods), which is confirmed by the out-of-plane x-ray diffraction with the observation of only (001) and (002) reflections from the FeRh thin film (see the Supplementary Materials).The details of the film growth and structural characterizations can be found in Materials and Methods and the Supplementary Materials (48). The phase transition temperature of the FeRh on PMN-PT substrates was ~380 K upon heating (from antiferromagnetic to ferromagnetic) and ~360 K upon cooling (from ferromagnetic to antiferromagnetic), confirmed by both resistivity and magnetization measurements (see the Supplementary Materials). We performed the FMR measurements on the FeRh/PMN-PT bilayers at various temperatures across the phase transition and under different applied electric fields. The FMR spectrum was acquired by measuring the field derivative of the power absorption intensity at a fixed frequency of 9.5 GHz while sweeping the external magnetic field along the film in-plane [100] direction. The PMN-PT substrates were poled before the FMR measurements.

Figure 1B (red curve) shows a typical FMR spectrum of the 50-nm FeRh thin film on PMN-PT at 380 K with 0 V μm−1 applied electric field, which was fitted with the derivative of the Lorentzian function. From the fitting, we determined the resonance peak-to-peak linewidth μ0ΔH, which is related to the effective magnetic damping parameter αeff through , where f is the frequency and γ is the gyromagnetic ratio (γ/2π = 28 GHz/T). Figure 1C summarizes αeff (and μ0ΔH at 9.5 GHz) of the FeRh as a function of temperature across its phase transition, showing a hysteretic behavior (with the heating and cooling branches guided by the gray arrows), which confirms the first-order nature of the phase transition in FeRh. At both the heating and cooling branches, αeff increases drastically with decreasing temperature. This can be understood as a change of the extrinsic damping part, due to the formation and growth of ferromagnetic (antiferromagnetic) domains upon heating (cooling) during the phase transition, as verified by x-ray magnetic circular dichroism (XMCD) (20, 22), magnetic force microscopy (48, 49), and electron holography (50) measurements. Specifically, upon cooling, the nucleation and growth of antiferromagnetic domains take place in a fully ferromagnetic state. The resulting coexistence of the ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic domains enhances two-magnon scattering due to the enhanced magnetic inhomogeneity (51) and enables the lateral spin pumping into the antiferromagnetic domains (16). Upon heating, the transition happens in a reversed manner. Besides the contribution from the extrinsic damping mechanisms, the intrinsic Gilbert damping also decreases slightly with the temperature as a result of the decreasing saturation magnetization. The overall change in the effective damping parameter comprises all three contributions, i.e., ∆αeff = ∆αint + ∆αlsp + ∆αtms, and the lateral spin pumping was found to be the dominant mechanism for damping modulation during the phase transition in FeRh (16).

The link between the αeff and the antiferromagnetic/ferromagnetic domain formation was further confirmed by estimating the ferromagnetic phase fraction from the FMR absorption curve obtained by integrating the FMR spectrum over the field (see the Supplementary Materials). The area under the FMR absorption curve represents the total magnetic moment in the sample and, therefore, the fraction of ferromagnetic domains, given that the saturation magnetization of each domain only decreases slightly with increasing temperature. Figure 1D shows the estimated ferromagnetic phase fraction as a function of the temperature, where the drastic increase of the ferromagnetic phase fraction is coincident with the decrease of the αeff. Below 340 K upon cooling (365 K upon heating), although the ferromagnetic phase still exists, the weak FMR amplitude and the wide linewidth make the fitting of the FMR spectrum unreliable.

Having established the FeRh magnetization dynamics across the magnetic phase transition at zero electric field, we then investigate their dependence on electric fields. The blue curve in Fig. 1B shows the FMR spectrum at 380 K upon heating with an applied electric field of 0.67 V μm−1 on the PMN-PT substrate. Noticeably, the broadening of the FMR linewidth and the decrease of the FMR amplitude are prominent. This is attributed to the electric-field–induced in-plane biaxial compressive strain that is expected to promote the formation of the antiferromagnetic phase (48, 49) and shift the magnetic phase transition to higher temperatures given the fact that the phase transition is extremely sensitive to the strain. Figure 1 (C and D) summarizes the temperature dependence of αeff (Fig. 1C) and the ferromagnetic phase fraction (Fig. 1D) with an applied electric field of 0.67 V μm−1, both showing the electric-field–induced shift of the magnetic phase transition temperature of ~15 K, which is consistent with our resistivity measurements (see the Supplementary Materials). Through this tuning mechanism, the modulation of effective damping (∆αeff) and the ferromagnetic phase fraction becomes more prominent around the phase transition temperatures.

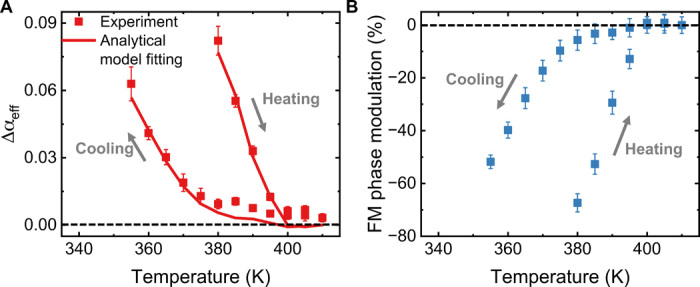

For better visualization, we extracted the modulation of αeff (Fig. 2A) and the ferromagnetic phase fraction (Fig. 2B) by the electric field as a function of temperature. Both ∆αeff and the ferromagnetic phase modulation peak at the magnetic phase transition temperatures, demonstrating again the correlation between the magnetic damping enhancement and the mixture of ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic phases, which causes the lateral spin pumping and the two-magnon scattering. It should also be noted that the ∆αeff is nonzero (Fig. 2A) even further above the phase transition temperature (>400 K) when the FeRh ferromagnetic phase modulation by electric field is essentially negligible (Fig. 2B). This small change in ∆αeff at a full ferromagnetic phase in FeRh could be attributed to the strain modulation of the Gilbert damping parameter or the piezoelectric surface morphology–induced inhomogeneous linewidth broadening, which has been reported in various magnetoelectric heterostructures (11, 13).

Fig. 2. Modulation of the damping during the magnetic phase transition.

(A and B) Change of the effective magnetic damping (A) and the ferromagnetic phase fraction induced by the applied electric field of 0.67 V μm−1 as a function of the temperature. The solid curve in (A) represents the analytical model fitting.

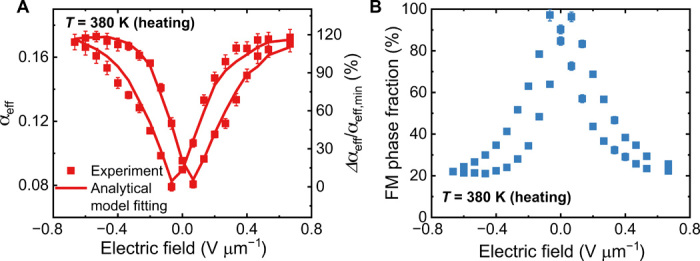

We further studied the isothermal electric-field modulation of αeff and the ferromagnetic phase fraction at 380 K during heating (where ∆αeff peaks), shown in Fig. 3 (A and B). The strain-mediated ferromagnetic phase fraction in FeRh gives rise to a record high isothermal electric-field control of a relative change in damping (∆αeff/αeff,min) of ~120%. This tunability is higher than that reported in magnetic semiconductors (10% tunability) (10) or in ferromagnetic metals (50% tunability) (11). The butterfly-like feature shown in both curves mimics the behavior of the electric field–induced strain in piezoelectric substrates, evidencing a strain-mediated effect. At large applied electric fields (±0.67 V μm−1), the compressive piezo strain favors the antiferromagnetic phase (Fig. 3B), enhancing αeff in FeRh. While at the coercive fields (0.1 V μm−1) of the PMN-PT substrate, its polarization and induced strain are both zero, which promotes more uniform ferromagnetic domains (Fig. 3B) and therefore leads to a decrease in αeff.

Fig. 3. Reversible modulation of the damping.

Effective magnetic damping (A) and the ferromagnetic phase fraction (B) as a function of applied electric fields at 380 K during heating. The solid curve in (A) represents the analytical model fitting.

DISCUSSION

As the ferromagnetic phase fraction decreases, the feature size of ferromagnetic domains δ shrinks (bottom schematic of Fig. 1A). We assume the change of intrinsic Gilbert damping to be independent of δ, as the Gilbert damping is shown to be proportional to the resistivity in FeRh (16), and the change of the resistivity (see the Supplementary Materials) is much smaller than that of the damping. Then, the enhancement of αeff, which is mainly contributed from the spin pumping and the two-magnon scattering, can be expressed as

| (1) |

in analogy with ferromagnetic/heavy metal bilayers (52), where Ms is the saturation magnetization of the ferromagnetic phase, is the interfacial spin-mixing conductance, the bulk spin conductance of the antiferromagnetic phase , and ρ, δAFM, and λ are the resistivity, antiferromagnetic domain size, and spin diffusion length of antiferromagnetic FeRh, respectively; β is the two-magnon scattering coefficient. By assuming that 𝛿 is inversely proportional to the ferromagnetic phase modulation, the experimentally measured ∆αeff can be well fitted on the basis of Eq. 1 as shown in the fitted curves in Figs. 2A and 3A. Two conclusions can be drawn through such analytical model fitting. First, the fitting suggests that the lateral spin pumping ∆αlsp contributes at least 81.6% of the total increase for αeff, which is consistent with a recent report (16). Second, the fitting gives an estimated lower limit for the interfacial spin-mixing conductance, , and an upper limit for the spin diffusion length of antiferromagnetic FeRh, λ < 1.2 nm (see the Supplementary Materials). Both parameters fall within the typical ranges of these two parameters in ferromagnet/heavy metal bilayers (53). Further work of frequency and magnetic field angle dependence of FMR will be necessary to precisely quantify the contribution to ∆αeff from different scattering mechanisms.

The present results demonstrate an effective approach to dynamically and reversibly modulate the effective magnetic damping up to 120% via the electric field–driven magnetic phase transition in FeRh/PMN-PT heterostructures. This large electric field control of spin dynamics is desirable for low-power spintronics, magnonics, and magnetic microwave devices, which may open opportunities, i.e., in STT-MRAM with tunable switching speed and critical current and in voltage-tunable spin waves for logic applications (5). Furthermore, we anticipate that the FeRh/piezoelectric hybrid structures to be a versatile platform for the fundamental understanding of damping mechanism in ferromagnets.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Film growth and structural characterization

FeRh thin films were grown on the (001)-oriented PMN-PT (0.72PbMg1/3Nb2/3O3-0.28PbTiO3) substrates by DC magnetron sputtering using a stoichiometric Fe0.5Rh0.5 target in a vacuum chamber with a base pressure of ~10−8 torr. The film deposition was performed at an Ar gas pressure of 3 mtorr and at a substrate temperature of 375°C, followed with an in situ annealing at 500°C for 1 hour. The epitaxial arrangement and crystalline orientation of the thin films were confirmed by x-ray diffraction (see fig. S1). The thickness of the film was determined by x-ray reflectivity. Rutherford backscattering spectrometry indicates that the chemical composition of FeRh is Fe0.51Rh0.49. Further details of FeRh thin film deposition and structural characterization can be found in our previous report (48).

Electrical transport measurements

Electrical resistivity measurements were carried out on as-grown full films in a van der Pauw geometry. DC electric fields of up to ±0.67 V μm−1 were applied between the top FeRh film and the bottom Au electrode on the underside of the PMN-PT substrate with the bottom electrode grounded.

Magnetic property measurements

FMR measurements were performed using a Bruker EMX electron spin resonance spectrometer with a TE102 cavity and a field sweeping mode at a fixed frequency of 9.5 GHz. Static magnetization measurements were carried out in a superconducting quantum interference device magnetometer.

Analytical model fitting and interpretation

Equation 1 depicts how the modulation of effective damping parameter ∆αeff varies with the feature size of ferromagnetic domain δ. However, Figs. 2 and 3 only provide data of ∆αeff versus the ferromagnetic phase modulation (denoted as x ∈ [0, −100%]). Therefore, to fit these data using Eq. 1, a knowledge of the relationship between δ and x is necessary. Although quantitative determination of such relationship may require detailed magnetic imaging studies [e.g., (20) and (22)] as a function of both temperature and electric field, qualitatively, it is clear that δ should decrease when the magnitude of x increases. Guided by this principle, we tested different types of mathematical functions including exponential, logarithmic, and asymptotic functions. It is found that the simple asymptotic function δ = − L/x yields the most accurate fit (with coefficient of determination R2 = 0.98). By further considering that antiferromagnetic domain size [denoted as δAFM, from tens of nanonmeters to hundreds of nanometers; (20) and (22)] is substantially larger than the spin diffusion length in antiferromagnetic FeRh [λ is typically small in heavy metals because of the strong spin-orbit coupling, normally below 10 nm (53)], the bulk spin conductance of the antiferromagnetic phase. We note that approches 1 when δAFM≥ 2λ.

On the basis of the arguments above, Eq. 1 can now be rewritten as

| (2) |

Equation 2 can be directly used to fit the experimental data of ∆αeff versus x in Figs. 2 and 3. The fitting yields ∆αeff = Ax + Bx2 (A = −9.489 × 10−2; B = 2.861 × 10−2), which allows us to evaluate the individual contributions of two-magnon scattering and lateral spin pumping as a function of x. Specifically, the contribution of lateral spin pumping is Ax/(Ax + Bx2), which remains above 81% even when x reduces to −77% (the largest modulation among our data). Moreover, A = −9.489 × 10−2 means that

| (3) |

For pure antiferromagnetic phase of FeRh, resistivity ρ = 150 × 10−8 ohms·m is extracted from fig. S2; saturation magnetization Ms increases moderately from 1.252 to 1.303 MA/m when temperature cools from 385 to 345 K (16). For simplicity, Ms is fixed at 1.25 MA/m, which is the value at 380 K under which we performed the isothermal electric field tuning of effective damping experiment. Rearranging Eq. 3 gives rise to the relation among , λ, and L

| (4) |

Equation 4 indicates that has a lower bound of 2.8717 × 1024 (ohms−1 m−3)L when λ → 0, because L > 0 and because the denominator also needs to be positive to ensure a positive . Thus, to estimate the lower bound of , the lower bound of L (=−δx) needs to be estimated. Let us do a most conservative estimation by assuming that the feature size of ferromagnetic domain δ takes an impractically small value of 0.126 nm (i.e., the radius of one single Fe atom) when x = −80%. In this case, the lower bound of is 2.9×1014 ohms−1 m−2. In practice, the feature size of ferromagnetic domain δ should be larger than 0.126 nm. For example, if assuming the ferromagnetic domain can be imaged by XMCD-photoemission electron microscopy (PEEM) at x = −80% (the ferromagnetic phase fraction is 20%), then its feature size should at least be larger than the spatial resolution of XMCD-PEEM [~30 nm in (20)]. In this case, the lower bound would increase to ~1015 ohms−1 m−2.

Equation 4 also indicates that 8.6151 × 1018(m−2)Lλ < 1 to ensure , because the numerator is always positive. Therefore, one has

| (5) |

Following the abovementioned analysis of estimating the lower bound of L, one can meanwhile estimate the upper bound of the spin diffusion length λ via Eq. 5, λ < 1.15 nm. Overall, the analyses above reasonably arrive at two conclusions. First, the real component of the spin-mixing conductance at the ferromagnetic/antiferromagnetic interface in FeRh has a lower bound of . Second, the spin diffusion length of antiferromagnetic FeRh has an upper bound of λ < 1.2 nm.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: T.N. acknowledges the support from the Beijing Advanced Innovation Center for Future Chip (ICFC). The work at UC Berkeley acknowledges the support from an ARO MURI and the SRC-ASCENT program. The work at Northeastern University is supported by the AFRL through contract FA8650-14-C-5706, the W.M. Keck Foundation, and the NSF TANMS ERC Award 1160504. J.H. acknowledges support from the NSF award CBET-2006028. Author contributions: T.N., Y.L., N.S., and R.R. conceived the research. J.W., S.S., J.H., N.S., and R.R. supervised the experiments. Y.L. and T.N. prepared the samples. Y.L., J.D.C., C.K., H.C., and Z.C. performed the electrical measurements. T.N., Z.H., X.W., and D.B. performed the FMR measurements. S.Z. and J.H. performed the analytical model fitting. T.N., Y.L., and J.H. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/40/eabd2613/DC1

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Gilbert T. L., A phenomenological theory of damping in ferromagnetic materials. IEEE Trans. Magn. 40, 3443–3449 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tserkovnyak Y., Brataas A., Bauer G. E. W., Halperin B. I., Nonlocal magnetization dynamics in ferromagnetic heterostructures. Rev. Mod. Phys. 77, 1375–1421 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ralph D. C., Stiles M. D., Spin transfer torques. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 320, 1190–1216 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brataas A., Kent A. D., Ohno H., Current-induced torques in magnetic materials. Nat. Mater. 11, 372–381 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chumak A. V., Vasyuchka V. I., Serga A. A., Hillebrands B., Magnon spintronics. Nat. Phys. 11, 453–461 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hellman F., Hoffmann A., Tserkovnyak Y., Beach G. S. D., Fullerton E. E., Leighton C., MacDonald A. H., Ralph D. C., Arena D. A., Dürr H. A., Fischer P., Grollier J., Heremans J. P., Jungwirth T., Kimel A. V., Koopmans B., Krivorotov I. N., May S. J., Petford-Long A. K., Rondinelli J. M., Samarth N., Schuller I. K., Slavin A. N., Stiles M. D., Tchernyshyov O., Thiaville A., Zink B. L., Interface-induced phenomena in magnetism. Rev. Mod. Phys. 89, 025006 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu L., Moriyama T., Ralph D. C., Buhrman R. A., Spin-torque ferromagnetic resonance induced by the spin Hall effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 036601 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nan T., Emori S., Boone C. T., Wang X., Oxholm T. M., Jones J. G., Howe B. M., Brown G. J., Sun N. X., Comparison of spin-orbit torques and spin pumping across NiFe/Pt and NiFe/Cu/Pt interfaces. Phys. Rev. B 91, 214416 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okada A., Kanai S., Yamanouchi M., Ikeda S., Matsukura F., Ohno H., Electric-field effects on magnetic anisotropy and damping constant in Ta/CoFeB/MgO investigated by ferromagnetic resonance. Appl. Phys. Lett. 105, 052415 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen L., Matsukura F., Ohno H., Electric-field modulation of damping constant in a ferromagnetic semiconductor (Ga,Mn)As. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 057204 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou H., Fan X., Wang F., Jiang C., Rao J., Zhao X., Gui Y. S., Hu C.-M., Xue D., Electric field controlled reversible magnetic anisotropy switching studied by spin rectification. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 102401 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zighem F., Belmeguenai M., Faurie D., Haddadi H., Moulin J., Combining ferromagnetic resonator and digital image correlation to study the strain induced resonance tunability in magnetoelectric heterostructures. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 85, 103905 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nan T., Emori S., Peng B., Wang X., Hu Z., Xie L., Gao Y., Lin H., Jiao J., Luo H., Budil D., Jones J. G., Howe B. M., Brown G. J., Liu M., Sun N., Control of magnetic relaxation by electric-field-induced ferroelectric phase transition and inhomogeneous domain switching. Appl. Phys. Lett. 108, 012406 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nan T., Hu J.-M., Dai M., Emori S., Wang X., Hu Z., Matyushov A., Chen L. Q., Sun N., A strain-mediated magnetoelectric-spin-torque hybrid structure. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1806371 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tserkovnyak Y., Brataas A., Bauer G. E. W., Spin pumping and magnetization dynamics in metallic multilayers. Phys. Rev. B 66, 224403 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Y., Decker M. M., Meier T. N. G., Chen X., Song C., Grünbaum T., Zhao W., Zhang J., Chen L., Back C. H., Spin pumping during the antiferromagnetic–ferromagnetic phase transition of iron–rhodium. Nat. Commun. 11, 275 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kouvel J. S., Hartelius C. C., Anomalous magnetic moments and transformations in the ordered alloy FeRh. J. Appl. Phys. 33, 1343–1344 (1962). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mankovsky S., Polesya S., Chadova K., Ebert H., Staunton J. B., Gruenbaum T., Schoen M. A. W., Back C. H., Chen X. Z., Song C., Temperature-dependent transport properties of FeRh. Phys. Rev. B 95, 155139 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uhlíř V., Arregi J. A., Fullerton E. E., Colossal magnetic phase transition asymmetry in mesoscale FeRh stripes. Nat. Commun. 7, 13113 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baldasseroni C., Bordel C., Gray A. X., Kaiser A. M., Kronast F., Herrero-Albillos J., Schneider C. M., Fadley C. S., Hellman F., Temperature-driven nucleation of ferromagnetic domains in FeRh thin films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 100, 262401 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stamm C., Thiele J.-U., Kachel T., Radu I., Ramm P., Kosuth M., Minár J., Ebert H., Dürr H. A., Eberhardt W., Back C. H., Antiferromagnetic-ferromagnetic phase transition in FeRh probed by x-ray magnetic circular dichroism. Phys. Rev. B 77, 184401 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baldasseroni C., Bordel C., Antonakos C., Scholl A., Stone K. H., Kortright J. B., Hellman F., Temperature-driven growth of antiferromagnetic domains in thin-film FeRh. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 27, 256001 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mancini E., Pressacco F., Haertinger M., Fullerton E. E., Suzuki T., Woltersdorf G., Back C. H., Magnetic phase transition in iron–rhodium thin films probed by ferromagnetic resonance. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 46, 245302 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tanaka K., Moriyama T., Usami T., Taniyama T., Ono T., Spin torque in FeRh alloy measured by spin-torque ferromagnetic resonance. Appl. Phys. Express 11, 22–25 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ju G., Hohlfeld J., Bergman B., van Deveerdonk R. J. M., Mryasov O. N., Kim J.-Y., Wu X., Weller D., Koopmans B., Ultrafast generation of ferromagnetic order via a laser-induced phase transformation in FeRh thin films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 197403 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thiele J.-U., Buess M., Back C. H., Spin dynamics of the antiferromagnetic-to-ferromagnetic phase transition in FeRh on a sub-picosecond time scale. Appl. Phys. Lett. 85, 2857–2859 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thiele J.-U., Maat S., Fullerton E. E., FeRH/FePt exchange spring films for thermally assisted magnetic recording media. Appl. Phys. Lett. 82, 2859–2861 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kryder M. H., Gage E. C., McDaniel T. W., Challener W. A., Rottmayer R. E., Ju G., Hsia Y.-T., Erden M. F., Heat assisted magnetic recording. Proc. IEEE 96, 1810–1835 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maat S., Thiele J.-U., Fullerton E. E., Temperature and field hysteresis of the antiferromagnetic-to-ferromagnetic phase transition in epitaxial FeRh films. Phys. Rev. B 72, 214432 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clarkson J. D., Fina I., Liu Z. Q., Lee Y., Kim J., Frontera C., Cordero K., Wisotzki S., Sanchez F., Sort J., Hsu S. L., Ko C., Aballe L., Foerster M., Wu J., Christen H. M., Heron J. T., Schlom D. G., Salahuddin S., Kioussis N., Fontcuberta J., Marti X., Ramesh R., Hidden magnetic states emergent under electric field, in a room temperature composite magnetoelectric multiferroic. Sci. Rep. 7, 15460 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen X. Z., Feng J. F., Wang Z. C., Zhang J., Zhong X. Y., Song C., Jin L., Zhang B., Li F., Jiang M., Tan Y. Z., Zhou X. J., Shi G. Y., Zhou X. F., Han X. D., Mao S. C., Chen Y. H., Han X. F., Pan F., Tunneling anisotropic magnetoresistance driven by magnetic phase transition. Nat. Commun. 8, 449 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marti X., Fina I., Frontera C., Liu J., Wadley P., He Q., Paull R. J., Clarkson J. D., Kudrnovský J., Turek I., Kuneš J., Yi D., Chu J.-H., Nelson C. T., You L., Arenholz E., Salahuddin S., Fontcuberta J., Jungwirth T., Ramesh R., Room-temperature antiferromagnetic memory resistor. Nat. Mater. 13, 367–374 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jungwirth T., Marti X., Wadley P., Wunderlich J., Antiferromagnetic spintronics. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 231–241 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baltz V., Manchon A., Tsoi M., Moriyama T., Ono T., Tserkovnyak Y., Antiferromagnetic spintronics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 90, 015005 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moriyama T., Matsuzaki N., Kim K.-J., Suzuki I., Taniyama T., Ono T., Sequential write-read operations in FeRh antiferromagnetic memory. Appl. Phys. Lett. 107, 122403 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seifert T., Martens U., Günther S., Schoen M. A. W., Radu F., Chen X. Z., Lucas I., Ramos R., Aguirre M. H., Algarabel P. A., Anadón A., Körner H. S., Walowski J., Back C., Ibarra M. R., Morellón L., Saitoh E., Wolf M., Song C., Uchida K., Münzenberg M., Radu I., Kampfrath T., Terahertz spin currents and inverse spin Hall effect in thin-film heterostructures containing complex magnetic compounds. Spine 07, 1740010 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zsoldos L., Lattice parameter change of FeRh alloys due to antiferromagnetic-ferromagnetic transformation. Phys. Status Solidi 20, K25–K28 (1967). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Suzuki I., Naito T., Itoh M., Sato T., Taniyama T., Clear correspondence between magnetoresistance and magnetization of epitaxially grown ordered FeRh thin films. J. Appl. Phys. 109, 07C717 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Loving M. G., Barua R., Le Graët C., Kinane C. J., Heiman D., Langridge S., Marrows C. H., Lewis L. H., Strain-tuning of the magnetocaloric transition temperature in model FeRh films. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 51, 024003 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lewis L. H., Marrows C. H., Langridge S., Coupled magnetic, structural, and electronic phase transitions in FeRh. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 49, 323002 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Foerster M., Menéndez E., Coy E., Quintana A., Gómez-Olivella C., Esqué de los Ojos D., Vallcorba O., Frontera C., Aballe L., Nogués J., Sort J., Fina I., Local manipulation of metamagnetism by strain nanopatterning. Mater. Horiz. 7, 2059–2062 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fina I., Fontcuberta J., Strain and voltage control of magnetic and electric properties of FeRh films. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 53, 023002 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cherifi R. O., Ivanovskaya V., Phillips L. C., Zobelli A., Infante I. C., Jacquet E., Garcia V., Fusil S., Briddon P. R., Guiblin N., Mougin A., Ünal A. A., Kronast F., Valencia S., Dkhil B., Barthélémy A., Bibes M., Electric-field control of magnetic order above room temperature. Nat. Mater. 13, 345–351 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fina I., Quintana A., Martí X., Sánchez F., Foerster M., Aballe L., Sort J., Fontcuberta J., Reversible and magnetically unassisted voltage-driven switching of magnetization in FeRh/PMN-PT. Appl. Phys. Lett. 113, 152901 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xie Y., Zhan Q., Shang T., Yang H., Liu Y., Wang B., Li R.-W., Electric field control of magnetic properties in FeRh/PMN-PT heterostructures. AIP Adv. 8, 055816 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bennett S. P., Wong A. T., Glavic A., Herklotz A., Urban C., Valmianski I., Biegalski M. D., Christen H. M., Ward T. Z., Lauter V., Giant controllable magnetization changes induced by structural phase transitions in a metamagnetic artificial multiferroic. Sci. Rep. 6, 22708 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Amirov A. A., Rodionov V. V., Komanicky V., Latyshev V., Kaniukov E. Y., Rodionova V. V., Magnetic phase transition and magnetoelectric coupling in FeRh/PZT film composite. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 479, 287–290 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee Y., Liu Z. Q., Heron J. T., Clarkson J. D., Hong J., Ko C., Biegalski M. D., Aschauer U., Hsu S. L., Nowakowski M. E., Wu J., Christen H. M., Salahuddin S., Bokor J. B., Spaldin N. A., Schlom D. G., Ramesh R., Large resistivity modulation in mixed-phase metallic systems. Nat. Commun. 6, 5959 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu Z. Q., Li L., Gai Z., Clarkson J. D., Hsu S. L., Wong A. T., Fan L. S., Lin M.-W., Rouleau C. M., Ward T. Z., Lee H. N., Sefat A. S., Christen H. M., Ramesh R., Full electroresistance modulation in a mixed-phase metallic alloy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 097203 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gatel C., Warot-Fonrose B., Biziere N., Rodríguez L. A., Reyes D., Cours R., Castiella M., Casanove M. J., Inhomogeneous spatial distribution of the magnetic transition in an iron-rhodium thin film. Nat. Commun. 8, 15703 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zakeri K., Lindner J., Barsukov I., Meckenstock R., Farle M., von Hörsten U., Wende H., Keune W., Rocker J., Kalarickal S. S., Lenz K., Kuch W., Baberschke K., Frait Z., Spin dynamics in ferromagnets: Gilbert damping and two-magnon scattering. Phys. Rev. B 76, 104416 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhu L., Ralph D. C., Buhrman R. A., Effective spin-mixing conductance of heavy-metal–ferromagnet interfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 057203 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sinova J., Valenzuela S. O., Wunderlich J., Back C. H., Jungwirth T., Spin Hall effects. Rev. Mod. Phys. 87, 1213–1260 (2015). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/40/eabd2613/DC1