Abstract

Background and Objective:

Direct rigid laryngoscopy and general anaesthesia (GA) are associated with many problems. Regional anaesthesia/airway blocks can be considered as safer and easier alternative techniques especially among old and comorbid patients and conditions with difficult airways as well. The present study was conducted to compare efficacy of regional anaesthesia/airway blocks versus general anaesthesia for diagnostic direct (rigid) laryngoscopy.

Methods:

A randomised comparative trial was conducted among patients undergoing diagnostic direct laryngoscopy (DLS) for perilaryngeal lesions. Eighty patients of either sex aged between 20and 80 years and categorised as American Society of Anesthesiologists(ASA) grade I, II, III or IV were divided under two groups of 40 patients each. Group-A underwent DLS with airway blocks and group-B underwent DLS under GA. Haemodynamic parameters and analgesia were interpreted statistically.

Results:

Difference in haemodynamic stability and quality of post- operative analgesia were primary outcomes. Patients in group-A were observed to be haemodynamically more stable as compared to group-B patients with statistically significant P value (0.003 and 0.016 for pulse rate at 6 min and mean arterial pressure at 4 min, respectively). In postoperative period, group-A patients were found to be more comfortable (lower VAS scores) than group-B patients with P value (0.040, 0.043, 0.044 at 0, 5, 15 min, respectively).

Conclusion:

Regional airway blocks provide better haemodynamic stability and postoperative analgesia than general anaesthesia.

Key words: General anaesthesia, laryngoscopy, regional airway block

INTRODUCTION

Direct rigid laryngoscopy per se and general anaesthesia for this procedure, both are associated with challenges and complications like difficult airway, hypoxia, hypercarbia, arrhythmia, hypertension and tachycardia.[1] Postoperative complications like oedema, laryngospasm, sore throat and cough are also important concerns.[2] Also, these patients are very old, frail and have comorbidities like COPD, uncontrolled hypertension and diabetes, so are at very high risk for general anaesthesia. These can be avoided if the procedure is conducted in a sedated but arousable patient with intact airway reflexes under regional anaesthesia.[3,4]

Recently many innovative regional techniques have been in practice by anaesthesiologist but blocks are also subjected to certain rate of complications or failure.[5,6]

We used landmark method for airway blocks as ultrasound was not available in our set up. Use of ultrasound improves precision of blocks. Even though general anaesthesia is a standard technique used for diagnostic direct laryngoscopy, use of airway blocks for the same can be a boon, especially for above mentioned conditions.

Thus, we designed this study to compare efficacy of regional anaesthesia/airway blocks versus general anaesthesia for diagnostic direct laryngoscopy (DLS) with objectives to study the haemodynamic changes during DLS and requirement of analgesia.

METHOD

This randomised (consecutive sampling with every alternate patient taken in either group), single blinded, comparative trial was conducted; after taking the approval from Institutional Ethical and Research Board (Acad/SPMC/2019/1554; Dated: 19/03/2019) at our institute during the period from September 2018 to August 2019 among patients undergoing DLS. All patients of either sex aged between 20 and 80 years and categorised as American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade I, II, III or IV who reported within study duration were included in the study after obtaining valid written informed consent through consecutive sampling. The subjects were divided into two groups in proportion of 1:1. Patients with history of epilepsy/convulsions, presence of coagulopathies, hypersensitivity to any drug used in this study, pregnancy and lactation were excluded from the study.

Sample size of 32 patients per group was calculated for two independent study groups and continuous primary end points (means) with alpha error 5%, beta error of 20% and power of study 80% for moderate effect size. Mean VAS score at baseline (0 min) and standard deviation (0 and 6.3 +/−0.16) was taken from a previous study.8 The number was increased to 80 (40 patients per group) for possible dropouts.

Total 80 patients were enroled in the study as per inclusion and exclusion criteria after taking approval from Institutional Ethics and Research Board (Ref no. 2019/1554/19-03-2019/06). Every alternate patient undergoing DLS was selected for airway block or general anaesthesia, respectively. In this way, out of the total 80 patients, 40 were included under Group A (undergoing DLS with airway block) and the remaining 40 were included under Group B (undergoing DLS with GA).

Pre-anaesthetic checkup was done a day before surgery which included a detailed history, general physical and systemic examination. Basic investigations, complete blood count, bleeding time, clotting time, fasting blood sugar, blood urea, serum creatinine, chest radiograph, electrocardiogram, viral markers (HIV, HbsAg, HCV) were done. Patients were kept nil per oral overnight. They were explained about airway blocks technique and general anaesthesia and written informed consent was taken from them and their close relatives.

Subjects in group-A (n = 40) were given gargles with 2% viscous lignocaine up to10 mL (200mg) followed by three puffs of 10% lignocaine (30 mg) 10 min later followed by superior laryngeal nerve block with 1% lignocaine (4mL/40 mg) followed by recurrent laryngeal nerve block with 4% lignocaine (2 mL/80 mg). Subjects in group-B (n = 40) were administered inj. propofol 2 mg/kg and inj. succinylcholine 2 mg/kg.

For delivering airway blocks, first, for glossopharyngeal nerve block, 2% viscous up to 10 mL (200 mg) of lignocaine was given for gargling for 2 min and then the subject was told to expectorate. Gargling provided anaesthesia to the oral and pharyngeal mucosa but it did not cover the larynx and trachea adequately. After 10 min of gargling, 3 puffs of 10% lignocaine (30 mg) were sprayed on the mucosa of oropharynx, soft palate, posterior portion of the tongue and the pharyngeal surface of the epiglottis.[7]

Second, for superior laryngeal nerve block, under sterile aseptic precautions, subject was placed supine with head extended. The cornu of the hyoid bone was easily identified by palpating outwards from the thyroid notch along the upper border of the thyroid cartilage until the greater cornu was encountered just superior to its posterolateral margin. The non-dominant hand was used to displace the hyoid bone with contralateral pressure, bringing the ipsilateral cornu and the internal branch of the superior laryngeal nerve towards the anaesthesiologist. A 1.5 inch, 23-gauge needle was inserted in an anteroinferomedial direction until the lateral aspect of the greater cornu was contacted. The needle was retracted slightly after contacting the hyoid. After confirming negative aspiration for air and blood, 2 mL of local anaesthetic (1% lignocaine) without epinephrine was injected. The same procedure was repeated on the opposite side (total dose 40 mg).[8]

Finally, for recurrent laryngeal nerve block, the cricothyroid membrane was located by palpating the thyroid prominence and proceeding in a caudal direction. Under sterile aseptic precautions after administration of local anaesthetic, a 22 gauge needle with syringe containing 2mL of 4% lignocaine (80 mg) was passed perpendicular to the axis of the trachea and membrane was pierced. Needle was advanced till free air could be aspirated signifying that the needle was in the larynx. Instillation of local anaesthetic at this point resulted in coughing, thus, confirming the block.[8]

In postoperative period, all the patients were followed up for analgesia and sedation at 0, 15, 30 min and then at 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 12 h. Analgesia was judged via Visual analogue scale (VAS) score and sedation score was used for comparing sedation in A and B group. Rescue analgesia was given when VAS score was >3 by inj. aqueous diclofenac sodium 1 mg/kg.

Results were interpreted in terms of “mean ± standard deviation” and compared with previous studies. Entire data was tabulated and analysed statistically using Microsoft Office Excel 2007 and Primer of Biostatistics version 6.0. Patients” characteristics (non-parametric data) were analysed using the descriptive analysis. The inter-group comparison of the parametric/quantitative data was done using the Student's t-test. Qualitative data was analysed by applying Chi-square test. P value <0.05 was taken as significant.

RESULT

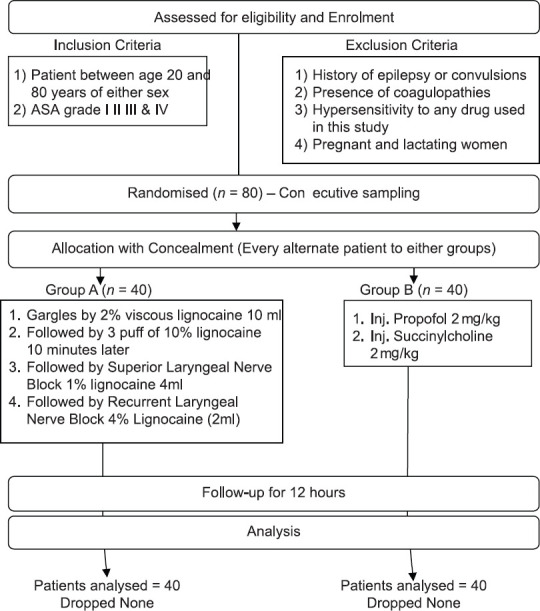

Eighty patients were enroled in our study from September, 2018 to August, 2019 [Figure 1]. Demographic data was comparable in both groups. Laryngoscopy was most commonly done in age group 51–60 and 61–70 years. Procedure was common in males as compared to females in both groups. Majority of patients were of ASA grade-1 (47.5%) followed by grade-2 (35%); grade-3 had 12.5% and 5% patients had grade-4 in group-A. Similarly, in group-B,67.5% patients had grade-1 followed by 27.5% in grade-2, 5% in grade 3 and 0% in grade 4 patients [Table 1]. This distribution of patients was according to randomisation of eligible patients coming in study duration.

Figure 1.

Consort flow diagram

Table 1.

Patients’ distribution according to ASA grade

| ASA grade | Group-A |

Group-B |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | |

| Grade-1 | 19 | 47.5 | 27 | 67.5 |

| Grade-2 | 14 | 35 | 11 | 27.5 |

| Grade-3 | 5 | 12.5 | 2 | 5 |

| Grade-4 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

Chi-square=5.037 with 3 degrees of freedom; P=0.225 (NS). P<0.5=Significant; NS=Not Significant, ASA=American Society of Anesthesiologists

Although in both groups, rise in mean blood pressures and pulse rate was not more than 20%–30% of baseline, still patients in group A were statistically more stable compared to group B with significant P value (<0.05) [Tables 2 and 3]. In group A, five patients while in group B, twelve patients required rescue analgesia. But statistically there was no difference in VAS score postoperatively in both the groups [Table 4].

Table 2.

Mean Arterial Blood Pressure (MAP)

| MAP | Group-A (n=40) | Group-B (n=40) | 95% C.I. | P * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 99.7±7.5 | 99.3±10.0 | −3.535-4.335 | 0.840 (NS) |

| P0 | 102.8±12.8 | 102.3±9.9 | −4.594-5.594 | 0.846 (NS) |

| P2 | 116.7±14.0 | 124.1±16.6 | −14.24-−0.5644 | 0.034 (S) |

| P4 | 119.2±13.3 | 127.5±16.7 | −15.02-−1.58 | 0.016 (S) |

| P6 | 103.3±12.7 | 109±9.1 | −10.62-−0.782 | 0.024 (S) |

*Student’s t-test; C.I. = Confidence interval for difference; P<0.05=Significant; NS=Not Significant; S=Significant

Table 3.

Statistical analysis of pulse rate

| PR | Group-A (n=40) | Group-B (n=40) | 95% C.I. | P * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 82.6±10.3 | 83.7±10.1 | −5.641-3.441 | 0.631 (NS) |

| P0 | 84.1±13.4 | 85.9±10.8 | −7.218-3.618 | 0.510 (NS) |

| P2 | 94.2±15 | 100.3±10.7 | −11.9-−0.3001 | 0.040 (S) |

| P4 | 100.3±14.1 | 104.3±14.6 | −10.39-2.389 | 0.032 (S) |

| P6 | 87.4±11.5 | 94.8±9.6 | −12.12-−2.684 | 0.003 (HS) |

*Student’s t-test; C.I. = Confidence interval for difference; NS=Not Significant; S=Significant; HS=Highly Significant

Table 4.

VAS score of Group-A versus Group-B at different time intervals

| Time | Group-A (n=40) | Group-B (n=40) | Value of U | Z-score | P* | Level of significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 min | 0.15±0.53 | 0.47±0.81 | 663 | 1.31347 | 0.1902 | NS |

| 5 min | 0.28±0.7 | 0.65±0.9 | 666 | 1.2846 | 0.20054 | NS |

| 15 min | 0.45±0.8 | 0.89±1.1 | 629 | 1.64064 | 0.101 | NS |

| 30 min | 0.85±1.5 | 0.9±1.2 | 741 | 0.56292 | 0.57548 | NS |

| 1 h | 0.5±0.98 | 0.67±1.1 | 741 | 0.56292 | 0.57548 | NS |

| 2 h | 0.45±0.95 | 0.4±0.8 | 796 | −0.03368 | 0.97606 | NS |

| 3 h | 0.25±0.66 | 0.2±0.5 | 795 | −0.0433 | 0.9681 | NS |

| 5 h | 0.15±0.5 | 0.1±0.4 | 780 | −0.18764 | 0.8493 | NS |

| 7 h | 0.1±0.4 | 0.1±0.4 | 800 | 0.00481 | 1 | NS |

| 9 h | 0.1±0.4 | 0.1±0.4 | 800 | 0.00481 | 1 | NS |

| 12 h | 0.1±0.4 | 0.1±0.4 | 800 | 0.00481 | 1 | NS |

*Mann-Whitney Test; P<0.05=Significant; NS=Not Significant; S=Significant

All the patients tolerated the blocks well and none were excluded from the study.

DISCUSSION

In our institute, diagnostic DLS for peri-laryngeal lesions is a very common procedure and is conventionally performed under GA. While GA has its own set of advantages, it can become risky, especially in dealing with difficult airway, fragile growths, bleeding polyps and patients with multiple comorbidities. In such a scenario, airway blocks can not only be life saving for patients but also a boon for anaesthesiologists. However, airway blocks although technically simple, require a considerable amount of practice and skill. Therefore, we did a study to compare general anaesthesia with airway blocks for diagnostic DLS.

In a study done by Trivedi and Patil in 2009, they compared airway blocks versus general anaesthesia to evaluate haemodynamic changes and concluded that there was a statistically significant increase in mean arterial pressure and heart rate in general anaesthesia group patients.[8] Gupta et al.in 2014 also compared two methods of airway anaesthesia, namely, ultrasonic nebulisation of local anaesthetics and airway blocks.[9] They found that there was no statistically significant difference in blood pressure between both groups at any time interval. Similarly, Kundra et al. also compared two methods of anaesthetising the airway for awake fiberoptic nasotracheal intubation and found that the mean HR and BP in the nebulisation group were significantly higher during endotracheal tube insertion.[10] In a study, Chatrath et al. in 2016 evaluated haemodynamic changes under combined regional nerve blocks during awake orotracheal fiberoptic intubation and concluded that there was statistically significant increase in heart rate, systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure at each minute during fiber optic bronchoscopy.[4] Maximum changes were seen at the time of intubation from the basal value, which was significant and gradually normalised towards the basal levels after 3rd–4th min of intubation and even lesser after 10 min of monitoring.

In our study, Group-A was more haemodynamically stable as compared to Group-B as we gave all three nerve blocks (glossopharyngeal nerve, superior laryngeal nerve, recurrent laryngeal nerve) and did not intubate the patients as in our institute DLS is traditionally done under general anaesthesia without intubation.

In our study, more number of patients required rescue analgesia in general anaesthesia group (12) as compared to block group (5). In the study done by Trivedi and Patil, there was a significant difference in VAS score which was significantly high till 12 h.[8]

Our study had a few limitations. We used landmark method for airway blocks as ultrasound was not available in our set up. Use of ultrasound improves precision of blocks. Also, the sample size of our study is still small. A larger sample size would have produced more precise results.

CONCLUSION

Regional airway blocks provide better haemodynamic stability and postoperative analgesia than general anaesthesia with lesser number of complications. Therefore, even though general anaesthesia is a definitive technique for managing diagnostic DLS, we recommend the use of airway blocks, especially for patients who fall into higher ASA grades (grade 3 and grade 4), have impaired haemodynamic stability and have anticipated difficult airway. However, more number of randomised controlled trials with a larger sample size should still be done to establish nerve blocks as a routine technique for diagnostic DLS.

Declaration of patients'consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patients have given their consent for their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients have understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

Authors wish to thank Dr. Shailendra Vashistha, MD (Assistant Professor, Department of Immuno-Haematology & Transfusion Medicine, Government Medical College, Kota) and VAssist Research (www.thevassist.com) for their valuable contribution in statistical analysis and manuscript writing.

REFERENCES

- 1.English J, Norris A, Bedforth N. Anaesthesia for airway surgery. Contin Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain. 2006;6:28–31. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stout DM. Correlation of endotracheal tube size with sore throat and hoarseness following general anesthesia. Anesthesiol. 1987;67:419–21. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198709000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmed A, Saad D, Youness AR. Superior laryngeal nerve block as an adjuvant to general anesthesia during endoscopic laryngeal surgeries. Egyptian J Anaesth. 2015;31:167–74. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chatrath V, Sharan R, Jain P, Bala A. The efficacy of combined regional nerve blocks in awake orotrachealfiberoptic intubation. Anesth, Essays Res. 2016;10:255–61. doi: 10.4103/0259-1162.171443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faccenda KA, Finucane B. Complications of regional anaesthesia. Drug safety. 2001;24:413–42. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200124060-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Furlan JC. Anatomical study applied to anesthetic block technique of the superior laryngeal nerve. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2002;46:199–202. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2002.460214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pani N, Rath SK. Regional & topical anaesthesia of upper airways. Indian J Anaesth. 2009;53:641–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trivedi V, Patil B. Evaluation of airway blocks versus general anesthesia for diagnostic direct laryngoscopy and biopsy for carcinoma of the larynx: A study of 100 patients. Int J Anesthesiol. 2009;26:1. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gupta B, Kohli S, Farooque K, Jalwal G, Gupta D, Sinha S. Topical airway anesthesia for awake fiberoptic intubation: Comparison between airway nerve blocks and nebulized lignocaine by ultrasonic nebulizer. Saudi J Anaesth. 2014;8(Suppl 1):15. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.144056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kundra P, Kutralam S, Ravishankar M. Local anaesthesia for awake fibreopticnasotracheal intubation. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2000;44:511–6. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2000.00503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]