Abstract

Background and Aims:

Ultrasound-guided serratus anterior plane (SAP) block is a field block with high efficacy. We studied the analgesic effect of the addition of dexamethasone to ropivacaine in SAP block for modified radical mastectomy (MRM).

Methods:

Sixty patients undergoing MRM were randomised into two groups. Patients in Group P (n = 30) received 0.375% ropivacaine (0.4 ml/kg) with normal saline (2 ml) and those in group D (n = 30) received 0.375% ropivacaine (0.4 ml/kg) with 8 mg of dexamethasone (2 ml) in ultrasound-guided SAP block. The primary objective was to compare the time to first rescue analgesia and the secondary objectives were to compare the intraoperative fentanyl requirement, total diclofenac and tramadol requirements, and occurrence of nausea and vomiting in 24 hours, postoperatively. The statistical analysis was done using Mann–Whitney U-test, Chi-square test, Fisher's exact test, and Kaplan Meier survival estimates.

Results:

More patients required rescue analgesia in 24 hours in group P (33%) than group D (10%, P = 0.04). The probability of a pain free-period was significantly higher in group D than group P (P = 0.03, log-rank test). Intra-operative fentanyl requirement and postoperative diclofenac and tramadol requirements were comparable in both the groups. The incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting was significantly more in Group P than Group D.

Conclusion:

Addition of dexamethasone to ropivacaine for SAP block increases the time to first rescue analgesic in the postoperative period.

Key words: Breast neoplasms, dexamethasone, modified radical mastectomy, ropivacaine, serratus anterior plane block

INTRODUCTION

Breast surgeries cause significant acute pain which can progress to persistent post-surgical pain in about 25–60% of cases.[1] Acute post-surgical pain can also lead to delayed discharge from the postoperative recovery room, impair pulmonary and immune functions, precipitate myocardial infarction, and may lead to increased length of hospital stay.[2] Hence, pain management in breast surgery patients in the perioperative period is important. Serratus anterior plane (SAP) block is a regional anaesthesia approach that provides analgesia of the thoracic area supplied by lateral cutaneous branches of T2-T9 spinal nerves. Ultrasound-guided SAP block has been a topic of research in the last few years mainly in breast surgery.[3] To enhance the quality and duration of regional blocks, many adjuvants have been used in addition to local anaesthetic drugs.[4] Corticosteroids combined with local anaesthetics provided analgesic effects in many human studies. Methylprednisolone increased the duration of axillary brachial plexus block when added to local anaesthetic drug.[5] Dexamethasone when combined with local anaesthetics also prolonged the duration of intercostal blockade and was shown to possess anti-inflammatory action.[6] However, the effect of dexamethasone in the SAP block has not been studied. This placebo controlled prospective randomised preliminary trial was aimed to study the effect of addition of dexamethasone to ropivacaine on the quality and duration of ultrasound-guided SAP block.

METHODS

This placebo-controlled prospective double-blind randomised preliminary trial was carried out at a tertiary care hospital from October 2018 to July 2019. Our study protocol was approved by the Institute Ethics Committee (IEC/373/6/2018) and the trial was registered in the Clinical Trial Registry, www.clinicaltrials.gov (CTRI/2018/09/015650). After obtaining written informed consent, 60 adult female patients of American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status (PS) I and II aged 18–65 years weight 30–80 kg undergoing modified radical mastectomy (MRM) under general anaesthesia with ultrasound-guided SAP block were recruited in the trial. The exclusion criteria were preexisting bleeding and coagulation disorders, morbid obesity, local inflammation, study drug allergy and patient with severe chest wall deformity. To the best of our knowledge, no data from any randomised clinical trial is available that compares the effect of adding dexamethasone to ropivacaine on ultrasound-guided deep serratus anterior plane block for MRM. So, we had decided to conduct a preliminary trial in 60 patients. They were randomised by computer generated random numbers into two groups: Group P and Group D. The randomisation was concealed by using serially numbered sealed opaque envelopes which were opened just before the procedure by the staff nurse who prepared the drug for the block and was not involved further in the study.

The patients in Group P received 0.375% Ropivacaine + 2 ml normal saline (total volume = 0.4 ml/kg) and those in Group D received 0.375% ropivacaine + 2 ml (8 mg) dexamethasone (total volume = 0.4 ml/kg). In both ropivacaine groups, the total drug volume was at least 20 ml but did not exceed 30 ml.

All patients underwent a routine preanaesthetic checkup and were explained about the study protocol. On arriving inside the operation theatre, an intravenous line was secured and standard ASA monitors (electrocardiogram {ECG}, non-invasive blood pressure {NIBP}, and saturation of peripheral oxygen {SPO2}) were attached. Baseline vital parameters including heart rate (HR), NIBP and SPO2 were noted. For postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) prophylaxis, 0.1 mg/kg of ondansetron was given intravenously just before induction of anaesthesia. Anaesthesia induction was done with 2 μg/kg of fentanyl, 1–2 mg/kg of propofol, and 0.5–0.8 mg/kg of rocuronium. This was followed by insertion of Proseal LMA (PLMA), its size depending on the weight of the patient. Anaesthesia was maintained with sevoflurane (0.8-1 MAC) in air -oxygen mixture with FiO2 of 40%. All patients were mechanically ventilated using volume-controlled ventilation to maintain end-tidal carbon dioxide (EtCO2) levels around 35–45 mmHg. Thereafter paracetamol (15 mg/kg) was given and repeated after every 8 hours for the first 24 hours. Intraoperative heart rate (HR), systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), mean arterial pressure (MAP) and ECG were monitored every 5 min. Blood glucose level was checked before the beginning of the block (baseline) and then at 1 hour intervals intra-operatively using the finger prick test.

The ultrasound-guided SAP block was administered in all patients after insertion of PLMA by the same anaesthesiologist who was not involved in further patient management and follow up. A linear high frequency (6–15 MHz) ultrasound probe (Edge II; SonoSite, Inc., Bothell, Washington) was used to guide the block. Under all aseptic precautions, the probe was placed in the sagittal plane in the mid clavicular region of the thoracic region. The ribs were counted inferiorly and laterally until the 5th rib was identified in mid-clavicular line. These muscles were recognised overlying the 5th rib: the latissimus dorsi (superficial), and serratus muscles (inferior). At more depth, intercostal muscles and pleura were seen. In an ultrasound-guided in-plane approach and in caudal to cranial direction, a 22G, blunt-tipped, 80-mm long sonoplex needle was inserted until the tip was placed between serratus anterior muscle and fifth rib. The drug was injected after aspiration to exclude intravascular needle placement.

For maintenance of general anaesthesia, intraoperative rocuronium boluses were administered as required. Fentanyl (0.5 μg/kg) was given if there was an increase in HR or MAP values by more than 20% of the baseline. Total intraoperative fentanyl doses used were noted. At the end of the procedure, sevoflurane was turned off, the fresh gas flow rate was increased and 100% O2 was given. Neostigmine (50 μg/kg) and glycopyrrolate (10 μg/kg) were used to reverse neuromuscular paralysis. After the return of adequate respiratory efforts, PLMA was removed. All patients were shifted to the post-anaesthetic care unit (PACU) for further monitoring, observation, pain assessment and rescue analgesia.

Postoperatively, pain assessment was done after shifting the patient to PACU (time zero) and thereafter at 1, 2, 6, 12 and 24 hours. The assessment was done by an independent anaesthesiologist who was not involved in the administration of block or intraoperative management of the patient using Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) (0-10). NRS was assessed at rest and on 90° arm abduction on the side of surgery. The HR and MAP were also assessed at the same time. On pain assessment, if NRS was ≥4, rescue medication, 1.5 mg/kg (adjusted to nearest 50 mg or 75 mg) of diclofenac diluted with 100ml normal saline was administered. The time to first rescue analgesia was noted. Thereafter diclofenac was given every 12 hours. Pain was again reassessed half an hour after giving diclofenac and if still NRS was ≥4, then tramadol (1 mg/kg) was administered. This second rescue analgesic was noted. After half an hour of second rescue analgesic, if the patient still had NRS ≥4 an additional tramadol was given to a maximum of 100 mg in 6 hours or a total of 400 mg in 24 hours. PONV was measured at 0, 1, 2, 6, 12, and 24 hours by the nausea vomiting score (NVS) which is as follows[7]:

0 – No nausea or vomiting, 1 – Nausea present/no vomiting, 2– Nausea present/vomiting present. 3- Vomiting >2 episodes in 30 minutes. Persistent nausea for more than 5 minutes or vomiting was treated with 0.1 mg/kg of intravenous ondansetron.

The primary objective of our study was to compare the time to first rescue analgesia. The secondary objectives were to compare (1) the intraoperative fentanyl requirement, (2) total diclofenac and tramadol consumption in the first 24 hours of the postoperative period and (3) occurrence of nausea and vomiting in postoperative period.

We used statistical software Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 23 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) for statistical analysis. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare continuous variables between groups after assessment for normality. Categorical variables were analysed using the Chi-square or Fisher's exact tests. The time to request for the first analgesia was analysed using Kaplan–Meier survival estimates and log-rank test. A P value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

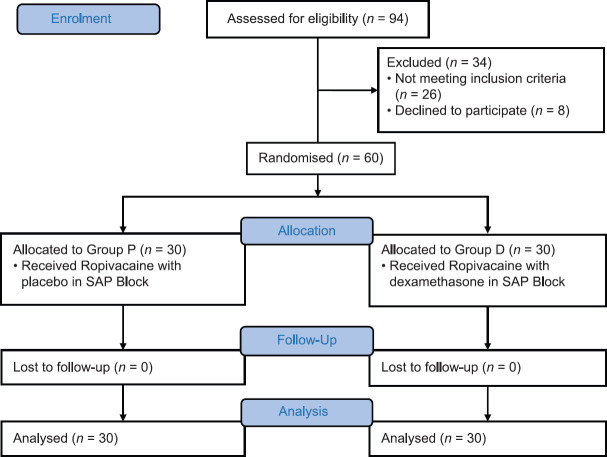

The consolidated standards of reporting trials (CONSORT) flow diagram for this study is presented in Figure 1. Ninety-four patients were examined for enrolment in the study. Of these, sixty were randomised into two groups of thirty each. The demographic data, ASA status, duration of surgery, baseline MAP and pre-operative as well as intraoperative blood glucose levels of the two groups are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram showing the flow of patients in the trial

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical data

| Parameter | Group P (n=30) | Group D (n=30) |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years | 47.5±8.6 | 48.1±9.3 |

| Weight (kg) | 55.8±6.5 | 57.0±7.5 |

| Height (cm) | 157.9±5.0 | 157.2±5.4 |

| BMI | 22.9±2.8 | 22.9±3.3 |

| Duration of Surgery (min) | 115.1±19.0 | 112.4±17.6 |

| Baseline HR | 85.9±6.8 | 87.4±7.1 |

| Baseline MAP (mmHg) | 88.2±8.2 | 87.6±7.4 |

| ASA PS I/II | ||

| Number of patients | 23/7 | 19/11 |

| Diabetes mellitus (Controlled) | 2 | 4 |

| Hypertension (Controlled) | 5 | 7 |

| Blood sugars (mg/dL) | ||

| Baseline | 89.8±8.8 | 92.1±11.9 |

| At 1 h | 100.3±9.6 | 101.8±10.3 |

| At 2 h | 103.5±7.6 | 104.3±13.6 |

The data are expressed as mean±standard deviation or numbers. BMI-Body mass index, HR-Heart rate, MAP-Mean arterial pressure, ASA PS-American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status

Intraoperative haemodynamic variables (MAP, HR) were comparable in both the groups. It was observed that 30% (9/30) patients in group P needed additional doses of fentanyl in the intraoperative period as compared to 20% (6/30) in group D (P = 0.32). Postoperative pain scores at rest were significantly less in group D at 2 hours, postoperatively. Postoperative pain scores at rest and on movement were significantly less in group D at 6, 12 and 24 hours postoperatively [Table 2]. The total volume of local anaesthetic (LA) injected in both groups was similar. In group P it was 20.4 ± 2.1 mL and in group D was 21.0 ± 2.7 mL (P = 0.37).

Table 2.

Postoperative numeric rating scores (NRS) for pain

| Time (hour) | GROUP P (n=30) |

GROUP D (n=30) |

P |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At rest | On movement | At rest | On movement | At rest | On movement | |

| 0 | 2.6±2.3 | 3.1±2.3 | 1.5±1.5 | 2.2±1.3 | 0.11 | 0.06 |

| 1 | 2.5±1.1 | 3.6±1.3 | 2.3±1.1 | 3.4±1.1 | 0.55 | 0.56 |

| 2 | 2.8±1.3 | 3.8±1.4 | 1.8±1.0 | 3.3±1.0 | 0.01 | 0.12 |

| 6 | 2.8±1.1 | 3.7±1.2 | 2.1±1.1 | 3.1±1.0 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| 12 | 2.6±1.3 | 3.7±1.3 | 1.9±0.9 | 2.9±1.0 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

| 24 | 2.5±0.6 | 3.5±0.8 | 2.1±0.6 | 2.8±0.7 | 0.02 | <0.01 |

The data are expressed as mean±standard deviation and analysed using Mann Whitney U test

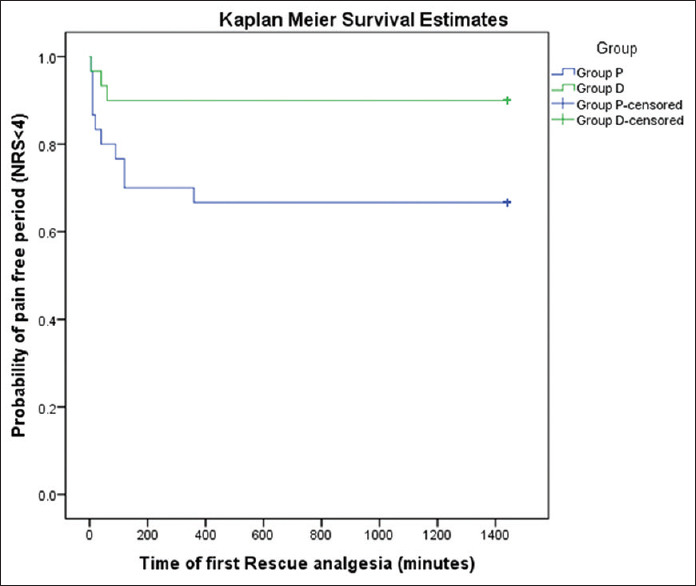

The number of patients requiring rescue analgesia was significantly more in Group P (10/30) compared to Group D (3/30, P = 0.04) in the first 24 hours of study. The median (interquartile range) time to first rescue analgesia was 30 (10–120) minutes in group P while in group D it was 40 (5–60) minutes. The Log-Rank Test showed a significant difference (P = 0.03) between the two groups for time to first rescue analgesia. The probability of a patient being pain-free (NRS <4) was significantly higher in group D as compared to group P [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Kaplan Meier survival estimates to estimate probability of pain-free period (NRS <4)

The total diclofenac requirement (9 patients in group P {17 doses} and 3 patients in group D {6 doses}, P = 0.10) and total tramadol requirement (4 patients in group P {6 doses} and no patients in group D, P = 0.11) was comparable in both groups.

The nausea and vomiting scores were significantly higher in group P at 2 and 12 hours postoperatively [Table 3]. The blood sugar levels were comparable in both groups.

Table 3.

Nausea and vomiting score (NVS) (P calculated in two groups between the number of patients having score 0 and ≥1)

| TIME (hour) | GROUP P (n=30) |

GROUP D (n=30) |

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NVS=0 | NVS ≥1 | NVS=0 | NVS ≥1 | ||

| 0 | 25 | 5 | 26 | 4 | 1.0 |

| 1 | 23 | 7 | 23 | 7 | 1.0 |

| 2 | 20 | 10 | 28 | 2 | 0.02 |

| 6 | 22 | 8 | 23 | 7 | 1.0 |

| 12 | 21 | 9 | 29 | 1 | 0.01 |

| 24 | 23 | 7 | 28 | 2 | 0.14 |

The data are presented as numbers and analysed using Fisher’s Exact test

No technique related adverse effects like pleural puncture, pneumothorax, or local anaesthetic toxicity were seen in any patient.

DISCUSSION

Dexamethasone has been tried as an adjuvant to local anaesthetic drugs in regional blocks since long, but broad research of literature revealed no study where dexamethasone has been used with ropivacaine to prolong the duration of analgesia in SAP block in patients undergoing MRM. In the previous few studies, the SAP block has been shown to cause pain relief for about 12 hours following breast surgery.[8,9,10] Hence, this study was done to evaluate the effect of dexamethasone addition to ropivacaine in SAP block on duration and quality of analgesia.

In 2013, Blanco et al. described ultrasound-guided SAP block in breast surgeries identifying two potential spaces: one is superficial and the other is deep to serratus anterior muscle at the level of 5th rib in the mid-axillary line.[3] Fajardo et al. preferred a deeper block, between the serratus anterior and external intercostal muscles in non-reconstructive breast surgeries and described adequate postoperative analgesia of 19 ± 4 hours.[11] In a study, the authors described drug deposition between latissimus dorsi and serratus anterior muscle (SA) in 11 patients undergoing breast conservation surgery with axillary dissection and reconstruction with LD myocutaneous pedicle flap. They found it easy to perform with high efficacy and no complication.[12] In a previously published study, the pain scores in the postoperative period were similar in both superficial and deep SAP block groups with minimal fentanyl consumption.[13]

The number of patients requiring rescue analgesia was 30% (9/30) in the placebo group as compared to 10% (3/30) in the dexamethasone group (p = 0.04). In our study, pain-free period in the postoperative phase was significantly higher in the dexamethasone group. In a study, it was noted that adding dexamethasone to bupivacaine prolonged the duration of the TAP block (459.8 vs. 325.4 min, P = 0.002) and decreased the occurrence of nausea and vomiting (6 vs. 14, P = 0.03).[14] Similarly, 5 mg dexamethasone added to 0.375% ropivacaine for popliteal block in hallux valgus surgery, increased the duration of both sensory and motor block by 12 hours (25 ± 7 hours, 46%) and 13 hours (36 ± 6 hours, 55%), respectively.[15] Studies have shown that, dexamethasone increases the duration of analgesia in postoperative period when added to ropivacaine in the TAP block given for abdominal hysterectomy, lower segment caesarean section, and inguinal hermia repair respectively.[16,17,18] In one study, dexamethasone prolonged the time to first analgesic request when added to bupivacaine for thoracic paravertebral block in patients undergoing modified radical mastectomy.[19]

In our study, the pain scores in the postoperative period were significantly reduced at rest, and at 2 hours in group D. Postoperative pain scores were significantly less at rest and on movement in group D at 6, 12 and 24 hours, postoperatively. No statistical difference was observed in intraoperative fentanyl boluses requirement, though a greater number of boluses were required in group P then group D. Intra-operative haemodynamic variables were comparable in both groups at all intervals. The consumption of diclofenac and tramadol in both groups were also comparable.

The study has some limitations. We observed the patients for 24 hours only. Most of the patients (80%) had adequate pain relief during the first 24 hours. Few adverse effects of dexamethasone such as impaired wound healing and adrenal suppression were not examined. However, earlier trials have shown that one dose of dexamethasone does not cause complications. Future studies should monitor patients for rescue analgesia for at least 48 hours. Our results can be used to design adequately powered and large sampled studies to know the effect of adjuvants in SAP block.

CONCLUSION

Adding dexamethasone to ropivacaine in SAP block increases the time to first rescue analgesic in the postoperative period in patients undergoing MRM.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our special thanks and gratitude to Dr. Sushma Bhatnagar, Professor and Head, Department of Onco-Anaesthesia and Palliative Medicine, Dr. B.R.A Institute Rotary Cancer Hospital, All India Institute of Medical Sciences during conduction of trial.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andersen KG, Kehlet H. Persistent pain after breast cancer treatment: A critical review of risk factors and strategies for prevention. J Pain. 2011;12:725–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joshi GP, Ogunnaike BO. Consequences of inadequate postoperative pain relief and chronic persistent postoperative pain. Anesthesiol Clin North Am. 2005;23:21–36. doi: 10.1016/j.atc.2004.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blanco R, Parras T, McDonnell JG, Prats-Galino A. Serratus plane block: A novel ultrasound-guided thoracic wall nerve block. Anaesthesia. 2013;68:1107–13. doi: 10.1111/anae.12344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pöpping DM, Elia N, Marret E, Wenk M, Tramer MR. Clonidine as an adjuvant to local anesthetics for peripheral nerve and plexus blocks: A meta-analysis of randomized trials. Anesthesiology. 2009;111:406–15. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181aae897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stan T, Goodman E, Cardida B, Curtis RH. Adding methylprednisolone to local anesthetic increases the duration of axillary block. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2004;29:380–1. doi: 10.1016/j.rapm.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kopacz DJ, Lacouture PG, Wu D, Nandy P, Swanton R, Landau C. The dose response and effects of dexamethasone on bupivacaine microcapsules for intercostals blockade (T9 to T11) in healthy volunteers. Anesth Analg. 2003;96:576–82. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200302000-00050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Safavi M, Honarmand A, Chegeni M, Hirmanpour A, Nazem M, Sarizdi S. Prophylactic antiemetic effects of Midazolam, Ondansetron, and their combination after middle ear surgery. J Res Pharm Pract. 2016;5:16–21. doi: 10.4103/2279-042X.176556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khalil AE, Abdallah NM, Bashandy GM, Kaddah TA. Ultrasound-guided serratus anterior plane block versus thoracic epidural analgesia for thoracotomy pain. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2017;31:152–8. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2016.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khemka R, Chakraborty A, Ahmed R, Datta T, Agarwal S. Ultrasound-guided serratus anterior plane block in breast reconstruction surgery. A A Case Rep. 2016;6:280–2. doi: 10.1213/XAA.0000000000000297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sites BD, Chan VW, Neal JM, Weller R, Grau T, Koscielniak-Nielsen ZJ, et al. The American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine and the European Society of Regional Anaesthesia and Pain Therapy Joint Committee recommendations for education and training in ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2009;34:40–6. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0b013e3181926779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fajardo M, López S, Diéguez P, Alfaro P, García FJ. A new ultrasound-guided cutaneous intercostal branches nerves block for analgesia after non-reconstructive breast surgery. Cir Mayor Ambulatoria. 2013;18:3–6. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khemka R, Chakraborty A. Ultrasound-guided modified serratus anterior plane block for perioperative analgesia in breast oncoplastic surgery: A case series. Indian J Anaesth. 2019;63:231–4. doi: 10.4103/ija.IJA_752_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhoi D, Selvam V, Yadav P, Talawar P. Comparison of two different techniques of serratus anterior plane block: A clinical experience. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2018;34:251–3. doi: 10.4103/joacp.JOACP_294_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ammar AS, Mahmoud KM. Effect of adding dexamethasone to bupivacaine on transversus abdominis plane block for abdominal hysterectomy: A prospective randomized controlled trial. Saudi J Anaesth. 2012;6:229–33. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.101213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vermeylen K, De Puydt J, Engelen S, Roofthooft E, Soetens F, Neyrinck A, et al. A double-blind randomized controlled trial comparing dexamethasone and clonidine as adjuvants to a ropivacaine sciatic popliteal block for foot surgery. Local Reg Anesth. 2016;9:17–24. doi: 10.2147/LRA.S96073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pehora C, Pearson AM, Kaushal A, Crawford MW, Johnston B. Dexamethasone as an adjuvant to peripheral nerve block. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;2017:CD011770. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011770.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta A, Gupta A, Yadav N. Effect of dexamethasone as an adjuvant to ropivacaine on duration and quality of analgesia in ultrasound-guided transversus abdominis plane block in patients undergoing lower segment cesarean section-A prospective, randomised, single-blinded study. Indian J Anaesth. 2019;63:469–74. doi: 10.4103/ija.IJA_773_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharma UD, Prateek, Tak H. Effect of addition of dexamethasone to ropivacaine on post-operative analgesia in ultrasonography-guided transversus abdominis plane block for inguinal hernia repair: A prospective, double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Indian J Anaesth. 2018;62:371–5. doi: 10.4103/ija.IJA_605_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.El Mourad MB, Amer AF. Effects of adding dexamethasone or ketamine to bupivacaine for ultrasound-guided thoracic paravertebral block in patients undergoing modified radical mastectomy: A prospective randomized controlled study. Indian J Anaesth. 2018;62:285–91. doi: 10.4103/ija.IJA_791_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]