Abstract

Macrophages, which are key cellular components of the liver, have emerged as essential players in the maintenance of hepatic homeostasis and in injury and repair processes in acute and chronic liver diseases. Upon liver injury, resident Kupffer cells (KCs) sense disturbances in homeostasis, interact with hepatic cell populations and release chemokines to recruit circulating leukocytes, including monocytes, which subsequently differentiate into monocyte-derived macrophages (MoMϕs) in the liver. Both KCs and MoMϕs contribute to both the progression and resolution of tissue inflammation and injury in various liver diseases. The diversity of hepatic macrophage subsets and their plasticity explain their different functional responses in distinct liver diseases. In this review, we highlight novel findings regarding the origins and functions of hepatic macrophages and discuss the potential of targeting macrophages as a therapeutic strategy for liver disease.

Keywords: Kupffer cells, monocyte-derived macrophages, liver inflammation, liver fibrosis, liver cancer

Subject terms: Inflammation, Cell death and immune response

Introduction

Macrophages, the most abundant liver immune cells, play a critical role in maintaining hepatic homeostasis and the underlying mechanisms of liver diseases.1 Hepatic macrophages consist of resident macrophages, Kupffer cells (KCs), and monocyte-derived macrophages (MoMϕs). Our previous review article published in 2016 highlighted research elucidating the heterogeneity of hepatic macrophages and the involvement of different subsets of macrophages in pathophysiological conditions of the liver. We also discussed potential strategies for targeting hepatic macrophages as a therapy for liver diseases.2 In subsequent years, numerous studies have provided new insights into the development, phenotypes, and functional roles of hepatic macrophages. This current review provides an update on the knowledge gained in recent years regarding the functions of hepatic macrophages in maintaining liver homeostasis, as well as the involvement of these cells in a multitude of processes associated with liver diseases, including exacerbation of injury, resolution of inflammation, tissue repair, pro- and antifibrogenesis, and pro- and antitumorigenesis. We also highlight novel perspectives on therapeutic strategies targeting hepatic macrophages to treat liver diseases.

Hepatic macrophages in liver homeostasis

Subsets, origins and replenishment of hepatic macrophages in the steady state

KCs and MoMϕs are distinct subsets of macrophages in the liver that can be distinguished from each other based on their differential expression of cell surface markers. In mice, MoMϕs are CD11b+, F4/80intermediate (int), Ly6C+ and CSF1R+, where KCs are CD11blow, F4/80high and Clec4F+.1,3–6 MoMϕs are differentiated from circulating monocytes, which are derived from bone marrow (BM) CX3CR1+CD117+Lin− progenitor cells.7 In mouse models of liver diseases, hepatic MoMϕs are divided into two main subpopulations according to Ly6C expression levels: Ly6Chigh and Ly6Clow MoMϕs.

Resident KCs are the predominant hepatic macrophages in the healthy naïve liver. It is widely accepted that KCs originate from yolk sac-derived CSF1R+ erythromyeloid progenitors (EMPs), which reside in the fetal liver during embryogenesis.8 In mice, on embryonic days 10.5–12.5, yolk sac-derived EMPs develop into fetal liver monocytes, which give rise to KCs.9,10 However, there is experimental evidence to support another scenario. On embryonic day 8.5, yolk sac EMPs develop into circulating macrophage precursors (pre-macrophages), which migrate to the nascent fetal liver in a CX3CR1-dependent manner before day 10.5 and subsequently give rise to KCs through regulation by an essential transcription factor, inhibitor of differentiation 3 (ID3).8,11 KCs have a half-life of 12.4 days in mice and require replenishment for maintaining homeostasis.12 KC replenishment in the steady state is independent of BM-derived progenitors but predominantly relies on self-renewal, which is tightly controlled by repressive transcription factors (MafB and cMaf).8,13–15

Recently, single-cell RNA-sequencing shed new light on the understanding of the heterogeneity of human hepatic macrophages. In the human liver, hepatic macrophages consist of CD68+MARCO+ KCs, CD68+MARCO− macrophages, and CD14+ monocytes.16,17 CD68+MARCO+ KCs are characterized by enriched expression of genes involved in maintaining immune tolerance (e.g., VSIG4) and suppressing inflammation (e.g., CD163 and HMOX1). CD68+MARCO− macrophages have a similar transcriptional profile (e.g., C1QC, IL-18, S100A8/9) as recruited proinflammatory macrophages.16 However, both CD68+MARCO− macrophages and hepatic CD14+ monocytes show significantly weaker proinflammatory responses than circulating CD14+ monocytes.17

Functionality of hepatic macrophages during homeostasis

KCs play a critical role in maintaining homeostasis of the liver and the whole body through five major functions. These include (i) clearance of cellular debris and metabolic waste,18–20 (ii) maintenance of iron homeostasis via phagocytosis of red blood cells (RBCs) and the subsequent recycling of iron,21–24 (iii) regulation of cholesterol homeostasis through the production of cholesteryl ester transfer protein, which is important for decreasing circulating high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol levels and increasing very low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol levels,25 (iv) mediation of antimicrobial defense,26,27 and (v) promotion of immunological tolerance.28,29

Clearance of damaged or aged RBCs is crucial for systemic homeostasis. Studies in which Na251CrO4-labeled oxidized RBCs and Na251CrO4-labeled RBC-derived hemoglobin-containing vesicles were injected into mice have demonstrated that KCs are responsible for the rapid uptake of nearly half of the injected RBCs and RBC-derived vesicles. These phagocytic processes rely on the presence of polyinosinic acid- and phosphatidylserine-sensitive scavenger receptors on KCs.20,21 An important outcome of the clearance of RBCs and their vesicles by KCs is the recycling of iron, which maintains iron homeostasis and prevents iron deficiency or iron toxicity. Moreover, KCs can directly take up iron and export it to hepatocytes for long-term storage through transferrin receptor and ferroportin, respectively.24,30,31 In addition to RBC clearance, KCs also contribute to the clearance of aged platelets. Indeed, KC depletion by liposome-entrapped clodronate (CLDN) causes the accumulation of aged platelets in the blood, leading to impaired coagulation.18 The expression of macrophage galactose lectin is important for KC-mediated platelet clearance.18

KCs reside along sinusoids and serve as the first-line defense against pathogens by efficiently recognizing and removing blood-borne Gram-positive bacteria. Complement receptor of immunoglobulin superfamily (CRIg), which is uniquely expressed on KCs in the liver, rapidly recognizes and binds to lipoteichoic acid (LTA), particularly on Gram-positive bacteria.27

KCs represent a major population of antigen presenting cells (APCs) in the liver. They are important for maintaining immunological tolerance of the liver through activating regulatory T cells (Tregs)29 and suppressing effector T cell activation induced by other APCs.28 In mice subjected to systemic delivery of low-dose particle-bound antigens, KC-associated antigen presentation induces CD4+ T cell arrest and expansion of IL-10-expressing Tregs, leading to tolerogenic immunity and suppression of inflammation in the liver.29 An in vitro coculture study demonstrated that KCs isolated from the livers of naïve mice can suppress dendritic cell (DC)-induced T cell activation by releasing prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and 15d-PGJ2.28 Moreover, KCs pretreated with interferon gamma (IFNγ) acquire the ability to suppress T cell responses by expressing indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and Fas ligand in vitro.32

An interesting population of MoMϕs residing in the hepatic capsule at steady state has been described.33 These liver capsular macrophages (LCMs) are CD11b+F4/80+CD11c+MHC-II+CSF1R+ but negative for Ly6C, Clec4F and TIM4, suggesting that they are distinct from Ly6C+ MoMϕs and KCs.33,34 LCMs are replenished by circulating monocytes.33 They recognize peritoneal bacteria accessing the liver capsule and promote the recruitment of neutrophils, thereby reducing hepatic pathogen loads. Depletion of LCMs by an anti-CSF1R antibody results in defective recruitment of neutrophils and increases hepatic dissemination of peritoneal pathogens,33 suggesting that this specific population of capsular phagocytes protects pathogens from spreading across compartments.

Hepatic macrophages in liver diseases

Dynamic changes in macrophage subsets and their replenishment during liver diseases

A rapid loss of KCs occurs during liver injury upon infection with the DNA-encoding viruses vaccinia virus, murine cytomegalovirus35 or the bacterium Listeria monocytogenes.36 A reduction in the number of KCs is also observed in models of methionine/choline-deficient (MCD) diet-induced nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)37 and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).38 With regard to KC replenishment, it is believed that KCs may have the capacity to self-renew through proliferation,39 probably due to colony stimulating factors.5 This hypothesis, however, requires further investigation. MoMϕs are believed to be the major contributors to replenishment of the macrophage pool. Indeed, after selective depletion of Clec4F-expressing KCs, recruited MoMϕs differentiate into fully functional KCs, restoring the population of hepatic macrophages within 1 month.6,40 As demonstrated by a novel mouse model of conditional KC depletion, monocytes can even acquire a “KC phenotype” within days. This process depends on the concerted actions of hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) and liver sinusoid endothelial cells (LSECs), which orchestrate monocyte engraftment and imprinting of the KC phenotype, including the transcription factors ID3 and liver X receptor-alpha (LXR-α).41,42

Depending on the signals expressed by the liver microenvironment, recruited MoMϕs can differentiate into cells of various phenotypes. For example, the recruitment of inflammatory Ly6Chigh MoMϕs specifically relies on the CCL2/CCR2, CCL1/CCR8, and CCL25/CCR9 signaling pathways, with the chemoattractants being secreted by activated KCs, HSCs, and LSECs.43–47 Inhibition or elimination of these signaling pathways in mice leads to reduced MoMϕ recruitment, hepatic inflammation, and overall fibrosis.43,48 However, it should be noted that MoMϕs are highly plastic, as highlighted by the potential of Ly6Chigh MoMϕs to switch toward a restorative Ly6Clow phenotype.49 Such a restorative phenotype can be induced by phagocytosis (e.g., of empty liposomes49) but also by exposure of MoMϕs to IL-4 and IL-33 derived from necrotic KCs.36

Aside from the proliferation of KCs and the recruitment and differentiation of MoMϕs, other cellular sources for hepatic macrophage replenishment have been suggested. Peritoneal macrophages, which are prenatally established and present in the peritoneal cavity, may be recruited through the visceral endothelium into liver tissue. In a model of sterile liver injury, mature peritoneal macrophages expressing CD102 and GATA6 have been found to migrate toward subcapsular liver tissue within 1 hour after injury. Furthermore, GATA6-deficient mice exhibit impaired macrophage recruitment and tissue regeneration.50,51 Splenic macrophages have also been suggested to contribute to the hepatic macrophage pool upon liver injury. The spleen serves as a reservoir of monocytes that are capable of regulating immune responses during liver damage.52 Indeed, the production and release of lipocalin-2 (LCN2)53 and CCL254 by the spleen regulates monocyte infiltration into the liver, KC activation, and overall hepatic inflammation. Due to the limited knowledge concerning splenic macrophages, their involvement in liver diseases remains to be elucidated.

Last, due to the complex nature of liver diseases and the contribution of other organs to disease initiation and progression, extrahepatic macrophages may also play an important role. For example, lipid-associated macrophages (LAMs), which are TREM2+CD9+CD68+ cells found around enlarged adipocytes during obesity, are important for preventing adipocyte hypertrophy and the loss of systemic lipid homeostasis in obesity.55 Interestingly, single-cell RNA-sequencing of liver tissues obtained from mice fed a high-fat diet (HFD) have revealed that TREM2+CD9+CD68+ LAMs express gene signatures associated with lipid metabolism. These results suggest that macrophages in different tissues could respond similarly to a microenvironmental cue and thus may serve as therapeutic targets for metabolic disease.55

Of particular interest, in mice fed a NASH diet, embryonic KCs undergo cell death, allowing repopulation by monocyte-derived KCs.56 The NASH diet induces significant changes in gene expression in KCs through LXR-mediated reprogramming, resulting in a partial loss of KC identity but increased expression of TREM2 and CD9.56 Increased TREM2 expression is strongly associated with higher nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) activity scores, which reflect the severity of steatosis, inflammation, hepatocyte ballooning, and fibrosis.57 Future studies are warranted to elucidate the underlying mechanisms by which TREM2 and TREM2+CD9+ KCs are involved in NASH development.

As almost all of the above studies relied on the use of mouse models, the relevance of these findings to humans requires further investigation. One of the debated topics concerning species differences is cell-type specific macrophage markers. Indeed, while murine KCs are mainly identified as F4/80+CD11bintClec4F+ cells,58,59 single-cell RNA-sequencing data has defined the human KC population as CD163+MARCO+CD5L+TIMD4+.60 Interestingly, a subpopulation of TREM2+ macrophages was found in the fibrotic scars of human cirrhotic livers by single-cell RNA-sequencing and immunohistochemical studies.61 A comprehensive analysis of early macrophage development during human embryogenesis suggested that yolk sac-derived primitive macrophages or embryonic liver monocytes as the major sources of tissue-resident macrophages in humans.62

The involvement of hepatic macrophages in the pathogenesis of liver diseases

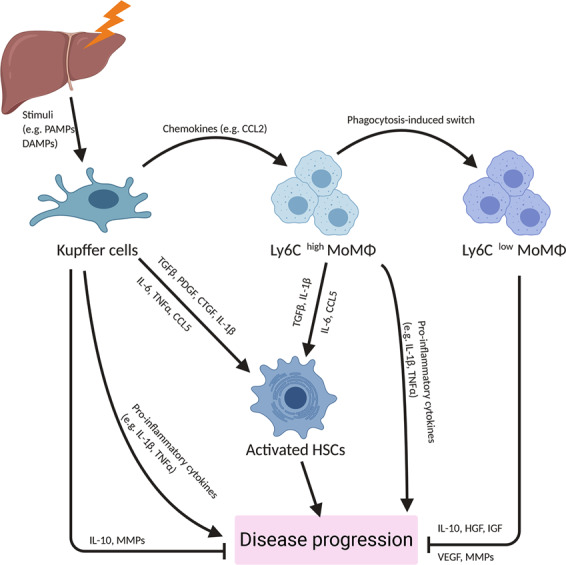

Due to their central position in the hepatic microenvironment, their long cytoplasmic protrusions, and the high density of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) on their surface, including Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and nucleotide binding oligomerization domain-like receptors (NLRs), KCs act as first-line responders upon liver injury (Fig. 1).59 Indeed, a plethora of signals associated with the initiation and progression of liver disease may lead to the activation of KCs, such as the following: (i) The release of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), e.g., high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), and ATP, by damaged hepatocytes undergoing apoptosis or necrosis. (ii) Pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), which are the result of increased intestinal permeability as well as changes in the gut microbiome and reach KCs in the liver sinusoids via the portal vein. Examples of relevant PAMPs include lipopolysaccharide (LPS), LTA, and β-glucan.63 (iii) Enhanced expression of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α (or similar transcription factors related to environmental stress) caused by a hypoxic liver environment, which is associated with progressive liver diseases.64 (iv) Metabolic changes in hepatocytes, caused by excessive uptake of dietary fats and carbohydrates, which are associated with high hepatic levels of triglycerides, cholesterol65 and various metabolites such as succinate,66 which is known to promote TLR signaling and inflammasome activation. (v) Extracellular vesicles, which are derived from various cells of the liver environment and contain proinflammatory stimuli such as mitochondrial double-stranded RNA,67 microRNA (miRNA)-27,68 and heat shock protein 90 (HSP90).69

Fig. 1.

The role of hepatic macrophages in liver diseases. Schematic overview of the roles of Kupffer cells and monocyte-derived macrophages in liver disease. CCL C-C chemokine ligand, CTGF connective tissue growth factor, DAMP damage-associated molecular pattern, HGF hepatocyte growth factor, HSC hepatic stellate cell, IGF insulin-like growth factor, IL interleukin, MMP matrix metallopeptidase, MoMϕ monocyte-derived macrophages, PAMP pathogen-associated molecular pattern, PDGF platelet-derived growth factor, TGF transforming growth factor, TNF tumor necrosis factor, VEGF vascular endothelial growth factor

Release of cytokines and chemokines

As the initial sensors of liver injury, KCs secrete a variety of chemokines to recruit monocytes and other leukocytes.70 KCs are a major source of CCL2,71,72 which recruits CCR2+ monocytes into the diseased liver (Fig. 1). KCs also secrete CXCL1, CXCL2, and CXCL8 to attract neutrophils,71 which contribute to hepatic ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury and heat-induced liver injury.70,73,74 Similarly, infiltrated Ly6Chigh MoMϕs also release chemokines and contribute to leukocyte recruitment during liver diseases. For example, in mouse models of liver fibrosis induced by carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) and an MCD diet, Ly6Chigh MoMϕs express CXCL16 and promote the recruitment of CXCR6+ natural killer T (NKT) cells, which exacerbate inflammation and fibrogenesis.75 In mice fed a HFD, Ly6Chigh MoMϕs produce CCL5 and CXCL9 in a S100 calcium-binding protein A9 (S100A9)-dependent manner. These chemokines lead to the hepatic recruitment of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, which contribute to insulin resistance.76,77 Studies of the chronically inflamed livers of patients with alcoholic liver disease (ALD), NASH, primary biliary cholangitis or primary sclerosing cholangitis have also shown that intermediate CD14highCD16+ monocytes (close to Ly6Chigh MoMϕs in the murine liver), which are derived from infiltrated classic CD14highCD16− monocytes, secrete proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, such as TNFα, IL-1β, CCL1 and CCL2.78

The contribution of KCs and Ly6Chigh MoMϕs to liver inflammation and injury observed in a study often depends on the disease and model used. For example, in a mouse model of steatohepatitis induced by a combination of a HFD and alcohol, inflammatory MoMϕs, but not KCs, are activated to produce proinflammatory TNFα and IL-1β in a Notch1-dependent manner.79 In a mouse model of acetaminophen (APAP)-induced liver injury (AILI), it appears that Ly6Chigh MoMϕs exhibit a stronger proinflammatory phenotype than KCs. Compared with KCs, Ly6Chigh MoMϕs express higher levels of complement factors (C3), proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-18 and MIF) and markers of a proinflammatory phenotype (CYBB, TREM1/2 and S100A8/A9).76

The TLR4 and TLR9 signaling pathways are important for mediation of the production of proinflammatory cytokines by hepatic macrophages.80–83 TLR4/MyD88 signaling is responsible for sensing DAMPs (e.g., HMGB1 and mtDNA from damaged cells), saturated fatty acids (e.g., palmitate) and gut-derived endotoxin. TLR4 deficiency reduces proinflammatory cytokines and liver injury in mouse models of AILI and ALD.81,84 Another study demonstrated that hepatic inflammation and injury are attenuated in endotoxin-resistant TLR4 mutant mice with diet-induced NASH.80 Similarly, as a pattern recognition receptor, TLR9 recognizes PAMPs and DAMPs (e.g., mtDNA). It has been demonstrated that TLR9 and stimulator of interferon genes (STING) synergistically trigger a proinflammatory response to mtDNA in macrophages during NASH development.85 In contrast, TLR9 deletion or pharmacological antagonism results in an attenuated response to bacterial DNA and mtDNA, leading to reduced IL-1β production, steatosis and liver injury in models of diet-induced NASH.82,83

Inflammasome activation

The inflammasome is a multiprotein complex that can sense danger signals from pathogens and damaged cells via TLRs and NLRs. Inflammasome activation triggers caspase-1-mediated cleavage and maturation of the cytokines IL-1β and IL-18.86 In the liver, gut-derived PAMPs, cell damage-induced DAMPs (e.g., ATP), crystals (e.g., cholesterol), palmitic acid, and ROS are well-characterized signals that trigger inflammasome activation in macrophages.87–90

Activation of inflammasomes, including the NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLPR3) inflammasome and absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2) inflammasome, in macrophages amplifies tissue inflammation and hepatocyte damage, thereby contributing to various liver diseases.91 In mouse models of hepatic I/R injury, inflammasomes are activated by ROS, HMGB1 (via TLR4) and histones (via TLR9) in KCs and promote liver injury.92–94 In other models of acute liver injury induced by D-galactosamine (GalN)/LPS, CCl4 or LPS, inflammasomes are activated in macrophages through an increase in mitochondrial ROS levels resulting from autophagy deficiency.95–97 However, studies on the role of inflammasome activation in AILI have yielded controversial results. It has been reported that extracellular ATP activates (via P2X7) NLRP3 in KCs and triggers IL-1β release, exacerbating liver injury.98,99 In support of this finding, P2X7-deficient mice exhibit decreased liver necrosis after APAP challenge.98 However, another study demonstrated that genetic deletion of NLPR3 or caspase-1 or antibody-mediated neutralization of IL-1β does not affect APAP-induced inflammation and injury in the liver.84

The role of macrophage inflammasome activation in chronic liver diseases, such as ALD and NASH, has also been reported.100 IL-1β, which is released as a result of inflammasome activation in KCs, plays a critical role in mediating alcohol-induced steatosis, inflammation, and liver injury.101 Deletion of caspase-1 or caspase-1 adaptor (ASC) in mice leads to impaired IL-1β production, thereby ameliorating ALD.101 With regard to NASH, in vitro studies have shown that the NLRP3 inflammasome can sense lipotoxicity-associated increases in intracellular ceramide levels, cholesterol crystals, saturated fatty acid content, mtDNA levels and ROS content, causing the induction of caspase-1 in macrophages and subsequently contributing to IL-1β production.90,102–105 In mouse models of NASH induced by a variety of diets, including an atherogenic diet, MCD, HFD and Western diet, NLRP3 inflammasome activation and subsequent IL-1β production exacerbate inflammatory responses while increasing the levels of IL-6 and CCL2 and enhance the numbers of infiltrated MoMϕs and neutrophils.90,105 Furthermore, genetic deletion or pharmacological inhibition of NLRP3 in mice significantly suppresses tissue inflammation and attenuates the pathological features of NASH, such as fibrosis and insulin resistance.90,102

The role of inflammasome activation in KCs during pathogen infection depends on the specific bacterial or viral stimulus. Pathogens such as Francisella tularensis and Salmonella typhimurium cause inflammasome activation in KCs and exacerbate liver injury.106–108 However, inflammasome activation by Listeria monocytogenes seems to promote the killing of bacteria. P2X5 deficiency attenuates Listeria-induced inflammasome activation and the bacterial-killing capacity of hepatic macrophages, which can be restored by IL-1β or IL-18.109 Different types of viruses also have varying effects on inflammasome activation in macrophages. The HBeAg protein of hepatitis B virus (HBV) represses NLRP3 and pro-IL-1β expression in macrophages via inhibition of NF-κB activation.89,108 Moreover, through attenuating ROS production, HBeAg suppresses caspase-1 activation and IL-1β maturation, resulting in suppression of the antiviral immune response.89,108 In contrast, the core protein of hepatitis C virus (HCV) triggers inflammasome activation and IL-1β production by macrophages through the induction of potassium and calcium mobilization, driving proinflammatory responses to HCV.110,111 In a model of murine hepatitis virus strain-3 (MHV-3)-induced fulminant hepatitis, macrophage NLRP3 inflammasome activation by ROS released from MHV-3-infected macrophages aggravates hepatitis.112

Inflammasome activation is observed in cholestatic liver diseases.113 Animal studies have demonstrated that macrophage inflammasome activation exacerbates bile duct ligation (BDL)-induced cholestatic liver injury.113,114 KC depletion by CLDN or treatment with an NLRP3 inhibitor significantly attenuates α-naphtylisocyanate (ANIT)-induced cholestatic liver injury, further supporting a role for macrophage inflammasome activation in the pathogenesis of the disease.115 Studies investigating whether bile acids play an important role in triggering macrophage inflammasome activation have yielded controversial findings. The hydrophobic bile acids chenodeoxycholic acid and deoxycholic acid have been found to induce macrophage NLRP3 inflammasome activation.114,116 In contrast, major endogenous bile acids, such as taurocholic acid, do not directly activate inflammasomes in macrophages or hepatocytes.113 Moreover, bile acid-induced macrophage inflammasome activation appears to be independent of the bile acid receptor TGR5, as TGR5 actually causes NLRP3 ubiquitination and inhibits inflammasomes.117

Crosstalk with other cells

The contribution of hepatic macrophages to the pathogenesis of various liver diseases is manifested by their interaction with other cell types in the liver, including HSCs, LSECs, neutrophils, and platelets. For example, HSCs are the main effector cells that cause hepatic fibrosis; nonetheless, hepatic macrophages modulate HSC viability and activation through releasing cytokines and other soluble factors, thereby playing an important role in both fibrogenesis and the resolution of fibrosis.118,119 Macrophage-HSC crosstalk will be discussed in more detail later in the “Fibrosis” section.

Macrophage-LSEC interactions play an important role in angiogenesis. In mice with chronic liver injury induced by BDL or CCl4, inflammatory MoMϕs accumulate in the injured liver, colocalizing with newly formed blood vessels in portal vein tracts and promoting vessel sprouting through the release of vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A) and matrix metallopeptidase 9 (MMP9).120 In partial hepatectomy (PHx)-induced liver regeneration, KCs release TNFα, which activates LSECs to express intracellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1). ICAM-1-expressing LSECs facilitate the adhesion and transmigration of monocytes, which promote vascular growth and support liver regeneration. Recruited monocytes serve as chaperones for endothelial sprouting by locally secreting proliferative factors (Wnt5a and Ang-1) and activating Notch1 to stabilize stalk cells.121

The macrophage-neutrophil interaction contributes to neutrophil recruitment and switching of the macrophage phenotype. Upon liver injury, neutrophils are recruited by CXCL1, CXCL2, and CXCL8 derived from KCs.71,122 During acute liver injury, infiltrated neutrophils can contribute to hepatic inflammation and aggravate liver diseases by producing ROS, secreting proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and TNFα and recruiting inflammatory monocytes.70,123 More recently, the importance of neutrophils in supporting macrophage-dependent repair mechanisms was reported.124 In infectious diseases, infiltrated neutrophils play a crucial role in bacterial killing through the release of antimicrobial granule proteins and/or the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs).70,125 A recent study also revealed a function for neutrophils in facilitating the differentiation of Ly6Chigh MoMϕs to Ly6Clow MoMϕs.126 Details are discussed in the “Phenotype switching” section.

Platelets contribute to inflammation and injury during acute liver injury and are also involved in hepatoprotective and hepatotoxic processes during chronic liver diseases.127 Studies of macrophage-platelet interactions have begun to emerge. In NASH, the interaction of platelets with KCs through platelet glycoprotein Ib alpha chain (GPIbα), rather than platelet aggregation, contributes to tissue inflammation and disease progression.128 Blocking this interaction with an anti-GPIbα antibody alleviates tissue inflammation, injury, steatosis, and fibrosis during NASH development.128 In hepatic I/R injury, the KC-platelet interaction contributes to exacerbation of liver injury, especially in steatotic livers.129,130 Moreover, the KC-platelet interaction is critical for first-line defense against bacterial infection. In mice infected by bacteria, such as Bacillus cereus and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), it has been observed that platelets switch from a transient “touch-and-go” interaction with KCs to sustained GPIIb/IIIa-mediated adhesion to KCs via von Willebrand factor (VWF). The two cell types collaborate to eradicate infectious bacteria.131 Although platelet recruitment is important for limiting bacterial infection, prolonged accumulation of platelets increases the risk of aberrant and damaging thrombosis throughout the liver.132 During Salmonella Typhimurium infection, inflammation in the liver triggers thrombosis within blood vessels via ligation of C-type lectin domain family 1 member B (CLEC-2) on platelets by podoplanin expressed by hepatic macrophages, including MoMϕs and KCs.133 Thus, when targeting macrophage-platelet interactions, both the immunological consequences of these cellular interactions and their related effects on blood flow and thrombogenesis need to be considered.

Roles of macrophages in resolving inflammation during liver injury

Macrophage death

Hepatic macrophages undergoing cell death, such as pyroptosis and necroptosis, are often observed during pathogen infection and sterile liver injury, and death of hepatic macrophages represents an important mechanism of bacterial clearance and inflammation resolution.134 During infection by flagellin-expressing Salmonella typhimurium, Legionella pneumophila or Bukholderia thailandensis, caspase-1-induced pyroptosis of macrophages causes the release of ROS, which subsequently promotes the bacteria-killing activity of neutrophils.135 Both Listeria monocytogenes and Salmonella enterica induce early rapid necroptosis of KCs in vivo. Necroptotic KCs release IL-1β,, which induces IL-33 production by hepatocytes. IL-33, together with basophil-derived IL-4, promotes alternative activation of anti-inflammatory MoMϕs, which replenish KCs and restore liver homeostasis.36 These findings indicate the crucial role of macrophage death in orchestrating the inflammatory responses and tissue repair processes during bacterial infection of the liver.

The role of macrophage death in resolving inflammation in sterile liver diseases remains controversial. In mice with alcoholic liver injury, after 3 days of feeding with an ethanol-containing liquid diet, KCs undergo forkhead box O3 (FOXO3)-dependent apoptosis, which promotes Ly6Chigh MoMϕs to differentiate into restorative Ly6Clow MoMϕs. Failure of KCs to undergo apoptosis in the absence of FOXO3 leads to hyperinflammation and increased sensitivity to liver injury induced by ethanol feeding plus LPS treatment.136 In contrast, two independent studies demonstrated the deleterious impact of macrophage death on hepatic I/R injury. One study reported a rapid loss of KCs through receptor-interacting protein kinase 1 (RIP1)-dependent necroptosis. RIP1 inhibition by necrostatin-1s protects KCs from I/R-induced depletion, resulting in suppression of inflammation and protection of the liver from I/R injury.137 Another study observed gasdermin D (GSDMD)-dependent pyroptosis of KCs after I/R injury. Similarly, mice with GSDMD deletion in myeloid cells exhibit attenuation of inflammation and alleviation of I/R injury.138

Phenotype switching

Infiltrated proinflammatory CCR2+Ly6Chigh MoMϕs usually represent the predominate population of macrophages in the early phases of liver injury.45 Differentiation of these Ly6Chigh MoMΦs into restorative Ly6Clow MoMϕs indicates the transition of an inflammation/injury phase to a resolution/repair phase.49,126,139,140 Ly6Clow MoMϕs show an anti-inflammatory and restorative phenotype by expressing MMPs (MMP9, MMP12, and MMP13), growth factors (HGF and IGF), and phagocytosis-related genes (MARCO) (Fig. 1).49,76,141 Expression of these genes enables wound healing, clearance of dead cells, and promotion of hepatocyte proliferation, thereby allowing the liver to return to homeostasis after injury and fibrosis.49,139,142,143 In mice challenged by APAP overdose, preventing monocyte infiltration by neutralization of CCR2 results in the absence of Ly6Clow MoMϕs and thus a lack of tissue inflammation resolution and the accumulation of late apoptotic neutrophils.143 Conversely, injection of BM-derived alternative activated macrophages, which are primarily Ly6Clow MoMϕs, stimulates hepatocyte proliferation and accelerates recovery of the liver from APAP-induced necrosis.142

Phagocytosis of dead cells (efferocytosis) is a major mechanism that promotes the switch of Ly6Chigh MoMϕs to Ly6Clow MoMϕs (Fig. 1). In vitro coculture experiments have demonstrated that phagocytosis of apoptotic hepatocytes by Ly6Chigh MoMϕs induces their switch to Ly6Clow MoMϕs.141 The efferocytosis-driven phenotype switch of Ly6Chigh MoMϕs is mediated by the STAT3/IL-10/IL-6 signaling pathway.144 A recent study demonstrated that IL-4 and/or IL-13 in conjunction with c-met proto-oncogene tyrosine kinase (MerTK)- and/or AXL receptor tyrosine kinase (AXL)-dependent efferocytosis are necessary to drive the differentiation of MoMϕs into an anti-inflammatory and tissue reparative phenotype.145 This finding is further supported by two studies of liver injury. One study demonstrated that during bacterial infection, basophil-derived IL-4 promotes the switch of Ly6Chigh MoMϕs to anti-inflammatory MoMϕs, thereby resolving inflammation and restoring tissue homeostasis.36 Another study demonstrated that mice deficient in MerTK exhibit a reduced number of Ly6Clow MoMϕs, correlating with increased accumulation of late neutrophils and impaired inflammation resolution upon APAP challenge.146

There is experimental evidence that aside from efferocytosis, interactions with other cell types underlie macrophage phenotype switching. For example, upon inflammatory stimulation by LPS, Ly6Chigh MoMϕs activate neutrophils to produce ROS,143 which in turn mediates the switch of Ly6Chigh MoMϕs to Ly6Clow MoMϕs via Ca2+-CaMKKβ-dependent AMPK activation.126 This switch is prevented by the depletion of neutrophils with an anti-Ly6G antibody or by genetic deletion of NADPH oxidase 2 (Nox2), which is required for the production of ROS by neutrophils.126,140

In mice infected with Schistosoma mansoni, the switch of Ly6Chigh MoMϕs to Ly6Clow MoMϕs appears to be facilitated by CD4+ T cells, as depletion of CD4+ T cells blocks this phenotypic switch.147 T cell-derived IL-4 may be an important mediator of macrophage differentiation. It has been shown that in the presence of IL-4, Ly6ClowF4/80int MoMϕs further differentiate into F4/80high macrophages. Failure of the conversion of Ly6ClowF4/80int MoMϕs to F4/80high macrophages leads to dysregulation of inflammation, disruption of liver granuloma architecture and increased mortality.148

Release of proresolving mediators

During the resolution phase, anti-inflammatory and prosurvival cytokines are released from macrophages. IL-10 produced by macrophages has been reported to protect against liver inflammation and injury in both acute and chronic liver diseases. KC depletion by CLDN exacerbates liver injury after APAP challenge and I/R treatment through a reduction in IL-10 expression.149,150 Liver injury is exacerbated in IL-10-deficient mice after APAP challenge, as in KC-depleted mice.149 In contrast, exogenous IL-10 can alleviate KC depletion-induced exacerbation of liver inflammation and damage caused by I/R.150 In liver fibrosis, activated HSCs induce MoMϕs to produce IL-10, which in turn suppresses HSC activation and the expression of αSMA and Col1a1.151

IL-6, which signals through STAT3, is an important hepatoprotective cytokine that can promote hepatocyte survival and proliferation, inhibit steatosis, and prevent insulin resistance.152 Hepatic macrophages are major sources of IL-6. In AILI, depletion of KCs abrogates IL-6 production, thereby exacerbating liver injury.149 A recent study demonstrated that HIF-2α in hepatic macrophages induces IL-6 production and promotes hepatocyte survival through STAT3 activation during AILI.153 In ALD, IL-6 produced by KCs triggers hepatocyte senescence, rendering hepatocytes resistant to alcohol-induced apoptosis as a protective mechanism.154

To promote tissue repair, macrophages secrete mediators involved in tissue growth (e.g., IGF) and remodeling (e.g., MMPs) in liver diseases, including AILI, ALD, and fibrosis.49,141,155 For example, in a mouse model of fibrosis induced by thioacetamide (TAA) or CCl4, macrophages are the major sources of MMP9 and MMP13, which promote the resolution of fibrosis. Studies of CLDN treatment in wild-type mice or diphtheria toxin (DT)-induced macrophage depletion in CD11b-DT receptor transgenic mice during fibrosis resolution demonstrate that a loss of macrophages results in delayed resolution of fibrosis and reduced hepatic expression of MMP9 and MMP13.156,157 Moreover, adoptive transfer of wild-type KCs relieves fibrolysis in MMP9-deficient mice.156

Role of macrophages in physiological and pathological repair

Liver repair and regeneration

Macrophages are the most extensively studied immune cells in the context of liver regeneration. Both KCs and MoMϕs play important roles in promoting hepatocyte proliferation. KC depletion by CLDN impairs DNA synthesis in the proliferating hepatocytes of mice during liver repair after BDL- or alcohol-induced injury.158,159 The beneficial role of KCs in liver regeneration was further confirmed in a mouse model of noninjury-induced PHx. KC depletion by CLDN attenuates hepatocyte proliferation and delays liver regeneration after PHx.160–164 KC-depleted mice exhibit reduced production of TNFα and IL-6 after PHx,161–163 and both cytokines are important for the initiation of hepatocyte proliferation.165–167 Moreover, TNFα enhances KC production of IL-6,166,168 which directly induces hepatocyte entry into the cell cycle via STAT3 activation.165,167

During severe liver injury involving significant loss of hepatocytes, hepatic progenitor cells (HPCs, also termed oval cells) play an important role in hepatocellular regeneration.169 KC depletion by CLDN impairs HPC-mediated differentiation into hepatocytes in two rodent models of liver regeneration: one triggered by 2-acetylaminofluorene (2-AAF) treatment plus PHx and the other caused by a choline-deficient, ethionine-supplemented (CDE) diet. The underlying mechanism involves reduced expression of TNFα, IL-6 and TNF superfamily member 12 (TWEAK) due to KC depletion.170–172 In mice treated with a CDE diet, macrophages produce Wnt3a as a result of the clearance of hepatocyte debris, and Wnt3a is an important driving force of HPC differentiation toward hepatocytes.173

Aside from KCs, CCR2+ MoMϕs have also been reported to promote liver regeneration. In mice, inhibition of MoMϕs recruitment resulting from impairment of myeloid CCR2 signaling results in attenuation of hepatocyte proliferation in CCl4-induced hepatotoxicity.174 Conditioned medium from Ly6Clow MoMϕs, but not Ly6Chigh MoMϕs, can induce hepatocyte proliferation in vitro.126 Furthermore, after PHx, the number of MoMϕs is increased in the liver, while the number of KCs remains unchanged.175,176 When hepatic infiltration of MoMϕs is impaired by BM irradiation, a CCR2 antagonist or CCR2 deletion, hepatocyte proliferation is attenuated after PHx.175,177 The underlying mechanism of MoMϕ-induced hepatocyte proliferation involves IL-6, as transferring wild-type BM to IL-6-deficient mice restores normal hepatocyte proliferation after PHx.178

The role of MoMϕs in HPC-induced liver regeneration has been reported as well. Adoptive transfer of BM-derived monocytes restores HPC differentiation into hepatocytes in KC-depleted mice fed a CDE diet.171 Even in the healthy liver, adoptive transfer of BM-derived monocytes causes the expansion and differentiation of HPCs into functional parenchyma by activating TWEAK.179

Fibrosis

Liver fibrosis is a common pathological feature of most chronic liver diseases. Persistent or repetitive liver injury is often accompanied by dysregulated wound healing and tissue repair, resulting in excessive deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM) or failure of inflammatory resolution in the ECM. Hepatic macrophage depletion alleviates fibrogenesis in mice,44,180–183 indicating a profibrogenic role of KCs (Fig. 1). First, in the early stage of liver injury, KCs secrete CCL2 to recruit proinflammatory and profibrogenic MoMϕs.44,45,184,185 Second, KCs can directly activate HSCs via growth factors (TGFβ, PDGF and CTGF).186–188 Third, KCs release proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines (TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6 and CCL5) to interact with HSCs to establish a profibrogenic niche.185 HCV-exposed KCs secrete TNFα, inducing NLRP3 inflammasome activation in HSCs and subsequent production of IL-1β by these cells,189 which drives the progression of NASH and alcoholic steatohepatitis (ASH).90,101 An in vitro study of cocultured BDL-treated HSCs and hepatic macrophages isolated from mice revealed that macrophage-derived IL-1β and TNFα directly promote NK-κB activation in HSCs and support their survival. In mice with BDL-induced liver fibrosis, KC depletion decreases IL-1β and TNFα production and increases HSC death, thereby attenuating fibrogenesis.190 In addition, an in vitro study demonstrated that HCV-exposed KCs produce CCL5, which induces fibrogenic activation of CCR5+ HSCs through ERK phosphorylation.189 KCs are also able to produce IL-6, which stimulates HSC proliferation, as well as the profibrotic tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases 1 (TIMP1) through a p-38 phosphorylation-dependent mechanism.191,192

The pro- and antifibrogenic functions of MoMϕs reflect their differentiation stages (Fig. 1). Using CD11b-DTR transgenic mice, studies have shown that deletion of infiltrating MoMϕs during fibrogenesis results in reduced HSC activation and ECM deposition, whereas deletion of MoMϕs during regression of fibrosis impairs ECM degradation, thereby exacerbating fibrosis.49,193 At early time points after their recruitment into the injured liver, Ly6Chigh MoMϕs exhibit a proinflammatory (TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6, CCL2 and CCL5) and profibrogenic (IL-13) phenotype and may directly activate HSCs in a TGFβ-dependent manner.45,49,78,190 Unlike Ly6Chigh MoMϕs, Ly6Clow MoMϕs appear to play an antifibrotic role. In experimental models of liver fibrosis induced by repetitive CCl4 treatment or an MCD diet, administration of a CCL2 inhibitor prevents the influx of Ly6Chigh MoMϕs and causes an increase in the proportion of Ly6Clow MoMϕs. As a result, fibrogenesis is attenuated, leading to increased resolution of fibrosis.194 In another study of CCl4-induced reversible fibrosis, activation of macrophage phagocytosis by the injection of liposomes was shown to induce the switch of Ly6Chigh MoMϕs to Ly6Clow MoMϕs, resulting in accelerated regression of liver fibrosis.49 Together, these studies unveil a critical role for Ly6Clow MoMϕs in promoting the resolution of fibrosis during chronic liver injury.

Recently, LC3-associated phagocytosis (LAP), a noncanonical form of autophagy that triggers the switch of MoMϕs to an anti-inflammatory phenotype, was reported in patients with cirrhosis.195 Studies involving pharmacological inhibition of LAP in monocytes isolated from patients with cirrhosis or genetic disruption of LAP in mice treated with CCl4 have demonstrated that LAP attenuates inflammation through FcγRIIA-mediated activation of the anti-inflammatory Src homology region 2 domain-containing phosphatase-1 (SHP1)/inhibitory immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAMi) pathway.195 In contrast, mice overexpressing human FcγRIIA in myeloid cells show increased LAP activation, resulting in resistance to inflammation and CCl4-induced liver fibrosis. Moreover, activation of LAP is abolished in monocytes from patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure and can be restored by specifically targeting ITAMi signaling with anti-FcγRIIA F(ab’)2 fragments or by intravenous injection of immunoglobulin (IVIg).195 Together, these studies suggest a possible approach for targeting macrophages to induce anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic effects.

Cancer

Approximately 75–85% of all cases of primary liver cancer are HCC, which is the fourth leading cause of global cancer-related death.196 The accumulation of hepatic macrophages in HCC-affected liver tissue of mouse and human origin and its correlation with HCC progression and poor prognosis197,198 suggest the importance of macrophages in this pathology. Indeed, tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) seem to have an inherent dominant protumorigenic character.199 Moreover, through secretion of a plethora of proangiogenic factors (VEGF, PDGF, and TGFβ) and cell proliferation stimuli (IL-1β, IL-6, CCL2, TNF, and VEGF), TAMs strongly favor tumor growth and development.2 In addition, acceleration of the migratory potential of HCC cells is induced by TAM-derived αMβ2 (CD11/18)-containing exosomes, which have been reported to activate the MMP9 signaling pathway.200 Through the production of various cytokines, including CCL17, CCL18, and CCL22, TAMs attract Tregs to the tumor environment, thereby hampering cytotoxic T cell activation and thus promoting tumor development.201

Mouse models of hepatocarcinogenesis and observations of human tissues have indicated that macrophage subsets in the liver have stage-dependent effects. While KCs are the major phagocyte population in the (noncirrhotic) tumor environment during early HCC, a shift is observed toward liver infiltrating macrophages once the primary tumor is established. KCs can promote early tumor activity through different mechanisms: First, enhanced expression of PD-L1202 and galectin-9203 allows interactions with PD-1 and TIM3, respectively, resulting in repression of immunogenic T cell activation. Second, HCC signaling causes the upregulation of TREM1 on KCs, leading to the recruitment of CCR6+Foxp3+ Tregs204 and thus suppressing the cytotoxic T cell response. Finally, KCs recruit platelets through hyaluron-CD44 binding, an essential step in hepatocarcinogenesis. Inhibition of the cargo-carrying ability, adhesion, and activation of platelets results in reduced KC activation and carcinogenesis in mouse models of HCC.128 The later stages of HCC development are primarily promoted by MoMϕ-mediated suppression of NK cell function.205

Although liver macrophages are mainly believed to stimulate HCC development, some studies suggest they also have the potential to inhibit tumor growth. Indeed, hepatic macrophages have been reported to stimulate CD4+ T cells to destroy precancerous senescent hepatocytes, thereby preventing tumor development.206 The importance of CD4+ T lymphocytes was further shown in NAFLD models, in which dysregulated lipid metabolism causes the selective loss of CD4+ but not CD8+ T lymphocytes, eventually leading to acceleration of hepatocarcinogenesis.207 However, due to contradictory results between distinct studies, these antitumorigenic effects demand further elucidation, especially considering the heterogeneity of the TAM population.

Therapeutic approaches for targeting macrophages in liver diseases

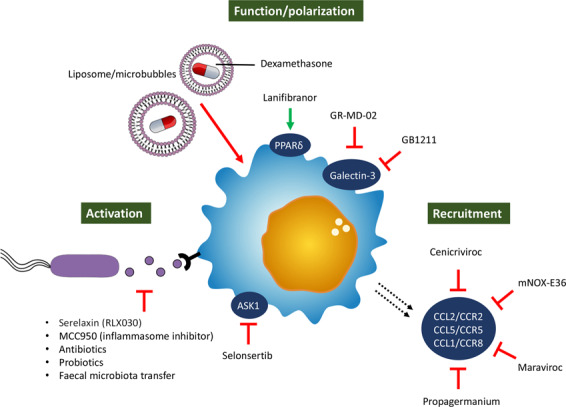

In the search for novel therapies for liver disease, multiple approaches that target distinct key pathways involved in disease initiation and progression are being explored.208 Due to the major implication of liver macrophages in normal tissue homeostasis, their role as first-line responders upon liver damage, and their dual promoting and inhibitory functions in liver disease, hepatic macrophages are intriguing therapeutic targets. While most macrophage-based therapies have only been tested in experimental animal models, some have already been evaluated in clinical trials. Approaches with targeting the inflammatory system can often be categorized as into those that (i) hamper inflammatory cell (monocyte and macrophage) recruitment, (ii) inhibit macrophage activation, and (iii) shape macrophage function and polarization2,209 (Fig. 2). More recently, cell-based therapies involving autologous macrophage infusions have been tested in patients with compensated liver cirrhosis.210 The prospect of utilizing macrophages as agents for cell-based therapies has been reviewed elsewhere.211

Fig. 2.

Macrophage-based therapeutic approaches for liver disease. Schematic overview of the different therapeutic approaches that focus on the inflammatory system divided into those that hamper inflammatory cell recruitment, those that inhibit macrophage action, and those that shape macrophage function and polarization. ASK-1 apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1, PPAR peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor, CCL C-C chemokine ligand, CCR C-C chemokine receptor

Inhibition of inflammatory cell recruitment

As previously mentioned, the recruitment of proinflammatory MoMϕs to the injured liver relies on the chemoattractant properties of several chemokines secreted by activated liver cells; CCL2/CCR2,44 CCL5/CCR5212, and CCL1/CCR843 are examples of several important chemoattractive axes. Interference with chemokine signaling could thus represent an interesting therapeutic approach that has proven efficacious in various experimental rodent models48,185,213 and can be achieved through different means, including monoclonal antibodies, receptor antagonists, aptamer molecules, and small-molecule inhibitors.209 This latter approach, especially intervention with chemokine signaling pathways by inhibitory drugs, has been extensively studied. In particular, cenicriviroc (CVC), a dual CCR2/CCR5 inhibitor, has been shown to efficiently block CCL2-mediated monocyte recruitment and to exert anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic effects in various mouse models.185,213,214 These results encouraged its advancement to clinical trials evaluating the efficacy in NASH patients with liver fibrosis. After 1 year of CVC treatment, a significant number of NASH patients responded well to the treatment, showing a statistically significant improvement in the histological stage of fibrosis,215 and these positive effects were maintained in responders in the 2nd year of treatment.216 Currently, a phase 3 trial of CVC including ~2000 patients is ongoing (NCT03028740). Other inhibitors of chemoattractant axes include propagermanium, a CCR2 inhibitor,217 mNOX-E36, an RNA-aptamer molecule that inhibits CCL2,194 and maraviroc, a CCL5/RANTES inhibitor,218 which all provoke disease amelioration in murine NAFLD/NASH models.

Recently, G protein-coupled receptor 84 (GPR84), a receptor for medium-chain fatty acids, was found to be upregulated on myeloid immune cells under inflammatory conditions. Enhanced GPR84 expression has been suggested to promote the inflammatory activation and phagocytic capacity of both human and murine macrophages.219 Inhibition of GPR84 by small-molecule antagonists in mouse models of acute and chronic liver injury hampers the recruitment of inflammatory cells to the site of injury and an overall reduction in hepatic inflammation and fibrosis.220

Inhibition of macrophage activation

Significant changes in the microbial gut composition and increased intestinal permeability, both of which are characteristics of progressive liver disease, cause increases in the levels of endotoxins (e.g., LPS) that reach the liver via portal blood flow. These PAMPs, together with DAMPs derived from damaged liver cells, activate liver-resident macrophages through PRRs, among which the importance of TLR4 is well documented. Indeed, genetic depletion of TLR4 has a preventive effect in murine models of liver disease,183 and the TLR4 inhibitor serelaxin (RLX030), when combined with the PPARγ agonist rosiglitazone, amplifies the beneficial effects of the latter compound.221 In line with these findings, inhibition of the PAMP-responsive NLRP3 inflammasome with MCC950 also alleviates fibrosis in murine NASH models.90 In addition, PAMP-dependent macrophage activation can be inhibited by elimination of the invasive microbiota; thus, the normal gut microbiome can be restored by broad-spectrum antibiotics, probiotics, and fecal microbiota transfer.222,223

Due to the overlap in inflammatory signal pathways (e.g., NF-κB, ASK1, JNK, and p38) between hepatic macrophages and hepatocytes, therapies targeting such pathways may affect both hepatocyte metabolism and macrophage activation.224 One example includes the apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK-1) inhibitor selonsertib (GS-4997), which, in an early phase 2 trial, was shown to decrease the disease severity of NASH patients.225 However, follow-up phase 3 trials including NASH patients with bridging fibrosis (NCT03053050) and cirrhosis (NCT03053063) failed to replicate these promising results.226

Shaping of macrophage function and polarization

Due to the duality of macrophage phenotype and thus function, therapies that induce a switch from the proinflammatory to regenerative phenotype would be beneficial for the treatment of liver disease. Such macrophage reprogramming can be principally achieved through different anti-inflammatory mediators, such as steroids (e.g., dexamethasone, a derivative of corticosterone), IL-4, IL-10, and PGE2.227

Due to the high scavenging activity of KCs, the systemic administration of various drug delivery systems, such as liposomes and microbubbles, causes their accumulation in the liver,228 highlighting their potential as macrophage-specific therapeutic approaches. For example, administration of dexamethasone-loaded liposomes ameliorates inflammation and fibrosis in murine models of inflammatory liver disease. Moreover, administration of dexamethasone-loaded vehicles results in significant inhibition of T-cell accumulation in the liver and a dominantly restorative (anti-inflammatory) macrophage phenotype.229 It is speculated that through modification of drug carriers, such as through implementation of arginine-like ligands and the addition of mannose to the surface, distinct macrophage subsets could be targeted. However, such tailored drug-delivery systems have not yet advanced to clinical studies.230,231

Galectin-3, a β-galactoside-binding lectin predominantly expressed in macrophages, mediates important inflammatory functions and is known to exert profibrogenic effects in HSCs.232 Although promising results have been achieved with the galectin-3 inhibitor GR-MD-02 in preclinical murine models,233 it did not alleviate fibrosis in a phase 2 clinical trial in NASH patients.234 The efficacy and safety of GB1211, another galectin-3 inhibitor, is currently under investigation (NCT03809052).

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors are nuclear transcription factors with distinct and multiple functions in NAFLD pathology, including effects on inflammation and lipid and glucose metabolism.235 Moreover, in vitro administration of lanifibranor, a pan-PPAR agonist, significantly reduces inflammatory gene expression induced by stimulation of murine macrophages and patient-derived circulating monocytes with palmitic acid and even leads to enhanced expression of genes involved in lipid metabolism. The anti-inflammatory action of lanifibranor can be induced through agonism of PPARδ, as evidenced by the effects of individual PPAR agonists.236 Moreover, lanifibranor treatment causes inhibition of MoMϕ accumulation, one of the key events preceding liver fibrosis, further highlighting its anti-inflammatory effects.185 The beneficial effects of lanifibranor were shown in preclinical choline-deficient, amino acid-defined high-fat diet (CDAA-HFD)-fed mice and are thought to be the result of a combination of different modes of action that inhibit liver damage, inflammation, and HSC activation.236 Lanifibranor is currently being investigated in a phase 2 clinical trial in NASH patients (NCT03008070).

In summary, intensive research in recent years has certainly improved our understanding of hepatic macrophages in the context of homeostasis and diseases. This rapid increase in knowledge related to the mechanisms of hepatic macrophages and the development of technical advances in targeted drug delivery have facilitated the translation of findings from rodent studies into novel therapies that can be used in the clinic.

Acknowledgements

J.L. is supported by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF, ImmuneAvatar). C.J. is supported by NIH grants DK109574, DK121330, DK122708, and DK122796. F.T. is supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG SFB/TRR296, CRC1382, Ta434/3–1, and Ta434/5–1).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

These authors contributed equally: Yankai Wen, Joeri Lambrecht

Contributor Information

Cynthia Ju, Email: changqing.ju@uth.tmc.edu.

Frank Tacke, Email: frank.tacke@charite.de.

References

- 1.Krenkel O, Tacke F. Liver macrophages in tissue homeostasis and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2017;17:306–321. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ju C, Tacke F. Hepatic macrophages in homeostasis and liver diseases: from pathogenesis to novel therapeutic strategies. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2016;13:316–327. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2015.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stutchfield BM, et al. CSF1 Restores Innate Immunity After Liver Injury in Mice and Serum Levels Indicate Outcomes of Patients With Acute Liver Failure. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:1896–1909 e14. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.08.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nascimento M, et al. Ly6Chi monocyte recruitment is responsible for Th2 associated host-protective macrophage accumulation in liver inflammation due to schistosomiasis. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004282. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zigmond E, et al. Infiltrating monocyte-derived macrophages and resident kupffer cells display different ontogeny and functions in acute liver injury. J. Immunol. 2014;193:344–353. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scott CL, et al. Bone marrow-derived monocytes give rise to self-renewing and fully differentiated Kupffer cells. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:10321. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fogg DK, et al. A clonogenic bone marrow progenitor specific for macrophages and dendritic cells. Science. 2006;311:83–87. doi: 10.1126/science.1117729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gomez Perdiguero E, et al. Tissue-resident macrophages originate from yolk-sac-derived erythro-myeloid progenitors. Nature. 2015;518:547–551. doi: 10.1038/nature13989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim KW, Zhang N, Choi K, Randolph GJ. Homegrown Macrophages. Immunity. 2016;45:468–470. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoeffel G, et al. C-Myb(+) erythro-myeloid progenitor-derived fetal monocytes give rise to adult tissue-resident macrophages. Immunity. 2015;42:665–678. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mass E, et al. Specification of tissue-resident macrophages during organogenesis. Science. 2016;353:aaf4238. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf4238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wacker HH, Radzun HJ, Parwaresch MR. Kinetics of Kupffer cells as shown by parabiosis and combined autoradiographic/immunohistochemical analysis. Virchows Archiv B Cell Pathol. Incl. Mol. Pathol. 1986;51:71–78. doi: 10.1007/BF02899017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soucie EL, et al. Lineage-specific enhancers activate self-renewal genes in macrophages and embryonic stem cells. Science. 2016;351:aad5510. doi: 10.1126/science.aad5510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hagemeyer N, et al. Transcriptome-based profiling of yolk sac-derived macrophages reveals a role for Irf8 in macrophage maturation. EMBO J. 2016;35:1730–1744. doi: 10.15252/embj.201693801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yona S, et al. Fate mapping reveals origins and dynamics of monocytes and tissue macrophages under homeostasis. Immunity. 2013;38:79–91. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.MacParland SA, et al. Single cell RNA sequencing of human liver reveals distinct intrahepatic macrophage populations. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:4383. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06318-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao J, et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals the heterogeneity of liver-resident immune cells in human. Cell Discov. 2020;6:22. doi: 10.1038/s41421-020-0157-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deppermann C, et al. Macrophage galactose lectin is critical for Kupffer cells to clear aged platelets. J. Exp. Med. 2020;217:e20190723. doi: 10.1084/jem.20190723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brubaker WD, et al. Peripheral complement interactions with amyloid beta peptide: erythrocyte clearance mechanisms. Alzheimer’s Dement.: J. Alzheimer’s Assoc. 2017;13:1397–1409. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Willekens FL, et al. Liver Kupffer cells rapidly remove red blood cell-derived vesicles from the circulation by scavenger receptors. Blood. 2005;105:2141–2145. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Terpstra V, van Berkel TJ. Scavenger receptors on liver Kupffer cells mediate the in vivo uptake of oxidatively damaged red blood cells in mice. Blood. 2000;95:2157–2163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kristiansen M, et al. Identification of the haemoglobin scavenger receptor. Nature. 2001;409:198–201. doi: 10.1038/35051594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Theurl I, et al. On-demand erythrocyte disposal and iron recycling requires transient macrophages in the liver. Nat. Med. 2016;22:945–951. doi: 10.1038/nm.4146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scott CL, Guilliams M. The role of Kupffer cells in hepatic iron and lipid metabolism. J. Hepatol. 2018;69:1197–1199. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Y, et al. Plasma cholesteryl ester transfer protein is predominantly derived from Kupffer cells. Hepatology. 2015;62:1710–1722. doi: 10.1002/hep.27985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Helmy KY, et al. CRIg: a macrophage complement receptor required for phagocytosis of circulating pathogens. Cell. 2006;124:915–927. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zeng Z, et al. CRIg Functions as a Macrophage Pattern Recognition Receptor to Directly Bind and Capture Blood-Borne Gram-Positive Bacteria. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;20:99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.You Q, Cheng L, Kedl RM, Ju C. Mechanism of T cell tolerance induction by murine hepatic Kupffer cells. Hepatology. 2008;48:978–990. doi: 10.1002/hep.22395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heymann F, et al. Liver inflammation abrogates immunological tolerance induced by Kupffer cells. Hepatology. 2015;62:279–291. doi: 10.1002/hep.27793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sukhbaatar N, Weichhart T. Iron Regulation: macrophages in Control. Pharmaceuticals. 2018;11:137. doi: 10.3390/ph11040137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sciot R, Verhoeven G, Van Eyken P, Cailleau J, Desmet VJ. Transferrin receptor expression in rat liver: immunohistochemical and biochemical analysis of the effect of age and iron storage. Hepatology. 1990;11:416–427. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840110313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yan ML, Wang YD, Tian YF, Lai ZD, Yan LN. Inhibition of allogeneic T-cell response by Kupffer cells expressing indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. World J. Gastroenterol. 2010;16:636–640. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i5.636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sierro F, et al. A Liver Capsular Network of Monocyte-Derived Macrophages Restricts Hepatic Dissemination of Intraperitoneal Bacteria by Neutrophil Recruitment. Immunity. 2017;47:374–388 e6. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.David BA, et al. Combination of Mass Cytometry and Imaging Analysis Reveals Origin, Location, and Functional Repopulation of Liver Myeloid Cells in Mice. Gastroenterology. 2016;151:1176–1191. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Borst K, et al. Type I interferon receptor signaling delays Kupffer cell replenishment during acute fulminant viral hepatitis. J. Hepatol. 2018;68:682–690. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bleriot C, et al. Liver-resident macrophage necroptosis orchestrates type 1 microbicidal inflammation and type-2-mediated tissue repair during bacterial infection. Immunity. 2015;42:145–158. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Devisscher L, et al. Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis induces transient changes within the liver macrophage pool. Cell. Immunol. 2017;322:74–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2017.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lefere S, Degroote H, Van Vlierberghe H, Devisscher L. Unveiling the depletion of Kupffer cells in experimental hepatocarcinogenesis through liver macrophage subtype-specific markers. J. Hepatol. 2019;71:631–633. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sieweke MH, Allen JE. Beyond stem cells: self-renewal of differentiated macrophages. Science. 2013;342:1242974. doi: 10.1126/science.1242974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beattie L, et al. Bone marrow-derived and resident liver macrophages display unique transcriptomic signatures but similar biological functions. J. Hepatol. 2016;65:758–768. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bonnardel J, et al. Stellate Cells, Hepatocytes, and Endothelial Cells Imprint the Kupffer Cell Identity on Monocytes Colonizing the Liver Macrophage Niche. Immunity. 2019;51:638–654 e9. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sakai M, et al. Liver-Derived Signals Sequentially Reprogram Myeloid Enhancers to Initiate and Maintain Kupffer Cell Identity. Immunity. 2019;51:655–670 e8. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heymann F, et al. Hepatic macrophage migration and differentiation critical for liver fibrosis is mediated by the chemokine receptor C-C motif chemokine receptor 8 in mice. Hepatology. 2012;55:898–909. doi: 10.1002/hep.24764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miura K, Yang L, van Rooijen N, Ohnishi H, Seki E. Hepatic recruitment of macrophages promotes nonalcoholic steatohepatitis through CCR2. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2012;302:G1310–G1321. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00365.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Karlmark KR, et al. Hepatic recruitment of the inflammatory Gr1+ monocyte subset upon liver injury promotes hepatic fibrosis. Hepatology. 2009;50:261–274. doi: 10.1002/hep.22950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nakamoto N, et al. CCR9+ macrophages are required for acute liver inflammation in mouse models of hepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:366–376. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chu PS, et al. C-C motif chemokine receptor 9 positive macrophages activate hepatic stellate cells and promote liver fibrosis in mice. Hepatology. 2013;58:337–350. doi: 10.1002/hep.26351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baeck C, et al. Pharmacological inhibition of the chemokine CCL2 (MCP-1) diminishes liver macrophage infiltration and steatohepatitis in chronic hepatic injury. Gut. 2012;61:416–426. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ramachandran P, et al. Differential Ly-6C expression identifies the recruited macrophage phenotype, which orchestrates the regression of murine liver fibrosis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:E3186–E3195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119964109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang J, Kubes P. A Reservoir of Mature Cavity Macrophages that Can Rapidly Invade Visceral Organs to Affect Tissue Repair. Cell. 2016;165:668–678. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gautier EL, et al. Gata6 regulates aspartoacylase expression in resident peritoneal macrophages and controls their survival. J. Exp. Med. 2014;211:1525–1531. doi: 10.1084/jem.20140570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Swirski FK, et al. Identification of splenic reservoir monocytes and their deployment to inflammatory sites. Science. 2009;325:612–616. doi: 10.1126/science.1175202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Aoyama T, et al. Spleen-derived lipocalin-2 in the portal vein regulates Kupffer cells activation and attenuates the development of liver fibrosis in mice. Lab. Investig. 2017;97:890–902. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2017.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li L, et al. The Spleen Promotes the Secretion of CCL2 and Supports an M1 Dominant Phenotype in Hepatic Macrophages During Liver Fibrosis. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2018;51:557–574. doi: 10.1159/000495276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jaitin DA, et al. Lipid-Associated Macrophages Control Metabolic Homeostasis in a Trem2-Dependent Manner. Cell. 2019;178:686–698 e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.05.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Seidman JS, et al. Niche-Specific Reprogramming of Epigenetic Landscapes Drives Myeloid Cell Diversity in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Immunity. 2020;52:1057–1074 e7. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xiong X, et al. Landscape of Intercellular Crosstalk in Healthy and NASH Liver Revealed by Single-Cell Secretome Gene Analysis. Mol. Cell. 2019;75:644–660 e5. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yang CY, et al. CLEC4F is an inducible C-type lectin in F4/80-positive cells and is involved in alpha-galactosylceramide presentation in liver. PloS ONE. 2013;8:e65070. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Guillot A, Tacke F. Liver macrophages: old dogmas and new insights. Hepatol. Commun. 2019;3:730–743. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ramachandran P, Matchett KP, Dobie R, Wilson-Kanamori JR, Henderson NC. Single-cell technologies in hepatology: new insights into liver biology and disease pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Gartroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17:457–472. doi: 10.1038/s41575-020-0304-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ramachandran P, et al. Resolving the fibrotic niche of human liver cirrhosis at single-cell level. Nature. 2019;575:512–518. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1631-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bian Z, et al. Deciphering human macrophage development at single-cell resolution. Nature. 2020;582:571–576. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2316-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shim YR, Jeong WI. Recent advances of sterile inflammation and inter-organ cross-talk in alcoholic liver disease. Exp. Mol. Med. 2020;52:772–780. doi: 10.1038/s12276-020-0438-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Koh MY, et al. A new HIF-1alpha/RANTES-driven pathway to hepatocellular carcinoma mediated by germline haploinsufficiency of SART1/HAF in mice. Hepatology. 2016;63:1576–1591. doi: 10.1002/hep.28468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tall AR, Yvan-Charvet L. Cholesterol, inflammation and innate immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015;15:104–116. doi: 10.1038/nri3793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tannahill GM, et al. Succinate is an inflammatory signal that induces IL-1beta through HIF-1alpha. Nature. 2013;496:238–242. doi: 10.1038/nature11986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lee, J. H. et al. Mitochondrial double-stranded RNA in exosome promotes interleukin-17 production through toll-like receptor 3 in alcoholic liver injury. Hepatology. 72, 609–625 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 68.Saha B, Momen-Heravi F, Kodys K, Szabo G. MicroRNA Cargo of Extracellular Vesicles from Alcohol-exposed Monocytes Signals Naive Monocytes to Differentiate into M2 Macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 2016;291:149–159. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.694133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Saha B, et al. Extracellular vesicles from mice with alcoholic liver disease carry a distinct protein cargo and induce macrophage activation through heat shock protein 90. Hepatology. 2018;67:1986–2000. doi: 10.1002/hep.29732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Heymann F, Tacke F. Immunology in the liver-from homeostasis to disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016;13:88–110. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Marra F, Tacke F. Roles for chemokines in liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:577–594 e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dambach DM, Watson LM, Gray KR, Durham SK, Laskin DL. Role of CCR2 in macrophage migration into the liver during acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in the mouse. Hepatology. 2002;35:1093–1103. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.33162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Huang H, et al. Damage-associated molecular pattern-activated neutrophil extracellular trap exacerbates sterile inflammatory liver injury. Hepatology. 2015;62:600–614. doi: 10.1002/hep.27841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.McDonald B, et al. Intravascular danger signals guide neutrophils to sites of sterile inflammation. Science. 2010;330:362–366. doi: 10.1126/science.1195491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wehr A, et al. Chemokine receptor CXCR6-dependent hepatic NK T Cell accumulation promotes inflammation and liver fibrosis. J. Immunol. 2013;190:5226–5236. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mossanen JC, et al. Chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 2-positive monocytes aggravate the early phase of acetaminophen-induced acute liver injury. Hepatology. 2016;64:1667–1682. doi: 10.1002/hep.28682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Xia C, et al. MRP14 enhances the ability of macrophage to recruit T cells and promotes obesity-induced insulin resistance. Int. J. Obes. 2019;43:2434–2447. doi: 10.1038/s41366-019-0366-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Liaskou E, et al. Monocyte subsets in human liver disease show distinct phenotypic and functional characteristics. Hepatology. 2013;57:385–398. doi: 10.1002/hep.26016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Xu J, et al. NOTCH reprograms mitochondrial metabolism for proinflammatory macrophage activation. J. Clin. Investig. 2015;125:1579–1590. doi: 10.1172/JCI76468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rivera CA, et al. Toll-like receptor-4 signaling and Kupffer cells play pivotal roles in the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J. Hepatol. 2007;47:571–579. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Inokuchi S, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 mediates alcohol-induced steatohepatitis through bone marrow-derived and endogenous liver cells in mice. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2011;35:1509–1518. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01487.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Miura K, et al. Toll-like receptor 9 promotes steatohepatitis by induction of interleukin-1beta in mice. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:323–334 e7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.03.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Garcia-Martinez I, et al. Hepatocyte mitochondrial DNA drives nonalcoholic steatohepatitis by activation of TLR9. The. J. Clin. Investig. 2016;126:859–64. doi: 10.1172/JCI83885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhang C, et al. Macrophage-derived IL-1alpha promotes sterile inflammation in a mouse model of acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2018;15:973–982. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2017.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yu Y, et al. STING-mediated inflammation in Kupffer cells contributes to progression of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. J. Clin. Investig. 2019;129:546–555. doi: 10.1172/JCI121842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ogura Y, Sutterwala FS, Flavell RA. The inflammasome: first line of the immune response to cell stress. Cell. 2006;126:659–662. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Szabo G, Petrasek J. Inflammasome activation and function in liver disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015;12:387–400. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wen H, et al. Fatty acid-induced NLRP3-ASC inflammasome activation interferes with insulin signaling. Nat. Immunol. 2011;12:408–415. doi: 10.1038/ni.2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yu X, et al. HBV inhibits LPS-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation and IL-1beta production via suppressing the NF-kappaB pathway and ROS production. J. Hepatol. 2017;66:693–702. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mridha AR, et al. NLRP3 inflammasome blockade reduces liver inflammation and fibrosis in experimental NASH in mice. J. Hepatol. 2017;66:1037–1046. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Szabo G, Csak T. Inflammasomes in liver diseases. J. Hepatol. 2012;57:642–654. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]