Abstract

Introduction:

Early childhood caries is a public health concern, and the considerable burden exhibited by Indigenous children highlights the oral health inequities across populations in Canada. Barriers include lack of access to oral health care and lack of culturally appropriate oral health promotion. The purpose of this study was to determine where and how First Nations and Métis parents, caregivers and community members learn about caring for young children’s oral health, and what ideas and suggestions they have on how to disseminate information and promote early childhood oral health (ECOH) in Indigenous communities.

Methods:

Sharing circles and focus groups engaged eight groups of purposively sampled participants (n = 59) in four communities in Manitoba. A grounded theory approach guided thematic analysis of audiorecorded and transcribed data.

Results:

Participants said that they learned about oral health from parents, caregivers and friends, primary care providers, prenatal programs, schools and online. Some used traditional medicines. Participants recommended sharing culturally appropriate information through community and prenatal programs and workshops; schools and day care centres; posters, mailed pamphlets and phone communication (calls and text messages) to parents and caregivers, and via social media. Distributing enticing and interactive oral hygiene products that appeal to children was recommended as a way to encourage good oral hygiene.

Conclusion:

Evidence-based oral health information and resources tailored to First Nations and Métis communities could, if strategically provided, reach more families and shift the current trajectory for ECOH.

Keywords: early childhood oral health, early childhood caries, First Nations, Métis, oral health promotion

Highlights

First Nations and Métis people say that improving early childhood oral health involves getting the attention of community members.

Caregivers need to be constantly reminded about the importance of young children’s oral hygiene.

Oral hygiene supplies such as toothbrushes should be provided to caregivers who cannot afford them.

Oral health providers and non-dental health providers, such as nurses, can share oral health information, including anticipatory guidance, with the entire community.

Information about dental care and good oral health behaviours can be given out at community events, through schools and health centres, and via community prenatal programs and social media.

Introduction

First Nations, Métis and Inuit in Canada, and especially children, have significant oral health disparities.1,2 Early childhood caries affects children’s health and wellbeing, including eating, speech development and self-image.3,4

Early childhood caries disproportionately affects Indigenous children.5,6 Lack of access to oral health care is a leading barrier. Other barriers are a lack of oral health awareness, social determinants of health and caregiver hygiene behaviours for children aged less than 72 months.5,7 Increasing caregivers’ awareness can help modify behaviours known to contribute to early childhood caries.8,9

The Healthy Smile Happy Child (HSHC) initiative has taken a community development approach to promoting young children’s oral health.10 Community development focusses on enabling communities to identify strategies, develop resources and determine teaching tools to prevent diseases in their particular contexts.11,12 Community participation, which includes enhancing capability of service providers and community members to mobilize vital health messages, is essential. Community members, rather than service providers, often know their community best.12 Understanding caregivers’ and health care providers’ knowledge of and attitudes towards existing oral health services is crucial in this process.13 Particularly important is the recruitment and training of Indigenous and non-Indigenous health care providers on the specific contexts and oral care needs of Indigenous communities.14

HSHC oral health promotion programs have adopted key Indigenous engagement strategies to encourage both uptake and reintegration of healthy traditional childrearing practices by caregivers.15 The overall goal of attaining early childhood oral health (ECOH) includes reducing caregiver risk behaviours and supporting health-promoting behaviours associated with early childhood caries. The continuation of these and other oral health promotion efforts will greatly benefit from a clearer understanding of the ECOH landscape in First Nations and Métis communities.

The purpose of our study was to understand:

where and how First Nations and Métis families and caregivers learn to take care of children’s teeth; and

the best ways to provide caregivers and communities with ECOH information to improve uptake and encourage the actions that reduce early childhood caries.

This article describes the suggestions of First Nations and Métis people on how to promote ECOH and prevent early childhood caries in Indigenous communities.

This baseline qualitative study was part of a larger mixed-methods ECOH intervention to prevent early childhood caries. In this study, we adopted community-based participatory research principles and Indigenous research methods to engage with four First Nations and Métis communities and residents. Community-based participatory research is often chosen as an equitable and trust-building approach in research with Indigenous peoples.16,17

The study was conducted in collaboration with the First Nations Health and Social Secretariat of Manitoba (FNHSSM) and the Manitoba Metis Federation (MMF). These Indigenous organizations represent registered First Nations and Métis peoples in Manitoba. The FNHSSM and the MMF representatives were key members of the research team from the start and assisted in every phase of the project. The representatives participated in designing the study, devising research questions, identifying and contacting communities to invite them to participate in the study, organizing meetings and data collection in the communities, and reviewing of data and manuscripts. These partners also shaped the nature and process of knowledge translation by reviewing documents and helping to organize community visits and activities to share findings and carry out ECOH promotion activities based on caregivers’ recommendations. Representatives had real-time access to data, were updated on process in monthly meetings, were part of all key decision-making, and reviewed information and relevant documents.

Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Manitoba’s Health Research Ethics Board. Approvals were also obtained from the FNHSSM and the MMF. The research process was guided by First Nations ownership, control, access and possession (OCAP) principles18 and MMF ownership, control, access and stewardship (OCAS) principles.19 Implementation of OCAP and OCAS means that, although data are analyzed at the University of Manitoba campuses, partners can access de-identified data at any time and in any format, upon request. Having decisionmaking roles on the research team means that communities have oversight in guiding how their data are used and disseminated. All information, documents and actions pertaining to the data are brought to the team for review and approval.

Participating communities gave free and informed consent prior to study commencement. 20 Written informed consent was obtained from participants prior to their taking part in the sharing circles or focus groups.

Methods

We used Indigenous research methods that foster cultural respect by mainstreaming Indigenous worldviews and perspectives.21 Sharing circles congruent with Indigenous values were used to engage participants.22 In total, 59 parents, grandparents and community members with children aged 72 months and under were purposively recruited by oral health promoters who lived and worked in the same rural communities as the study participants. Oral health promoters promote ECOH by providing oral health information and resources. Participants in urban communities were recruited by Indigenous-focus program coordinators.

Data collection

Sharing circles and focus groups were conducted at Indigenous-friendly programs in Winnipeg, Manitoba, and where community-based groups met in rural First Nations and Métis communities.20 Sessions were facilitated by an experienced qualitative researcher and supported by HSHC staff.

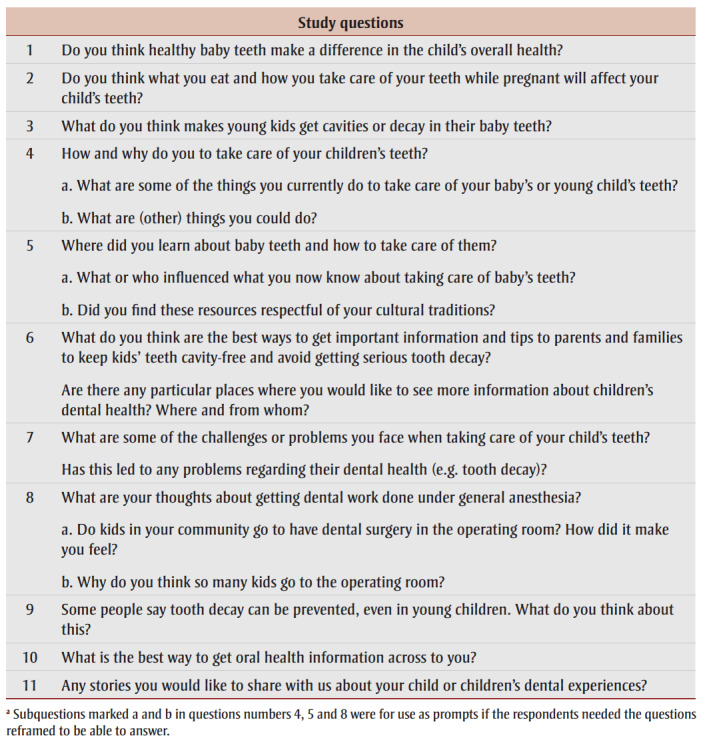

There were 11 key questions (Table 1).

Table 1. Focus group and sharing circles questions.

|

This article addresses responses to three of the questions, numbers 5, 6 and 10:

Where did you learn about baby teeth and how to take care of them?

What do you think are the best ways to get important information and tips to parents and families to keep kids’ teeth cavity-free and avoid getting serious tooth decay?

What is the best way to get oral health information across to you?

These three questions yield data and themes specific to oral health promotion relevant to Indigenous caregivers and communities.

Responses to the other questions have been addressed elsewhere.

Data analysis

We conducted a thematic analysis to generate themes in direct response to the questions asked. A grounded theory approach23 guided the study. We applied grounded theory because, although there has been some research on early childhood caries in First Nations communities, very little data exist for Métis populations. In addition, there were no published articles detailing community-driven health promotion strategies. Our aim was not to test the theory, but to understand the experiences of people living in First Nations and Métis communities.

Our process involved constant comparison of data, which is a key element in grounded theory. We conducted preliminary data analysis after each focus group and then compared the findings with those from previous groups to gauge similarities, differences and/or any outlying ideas and themes.23 The preliminary findings guided the next round of data collection. The research team’s knowledge of the literature and the qualitative researchers’ experience with Indigenous communities and Indigenous research methods influenced the theoretical approach.

In applying grounded theory, the researchers and data analysts avoided any theoretical preconceptions when designing open-ended, semistructured questions to explore the subject matter. The experienced interviewers used prompts to adjust any questions for a better understanding of participants’ perspectives.

All sharing circles and focus group sessions were audiorecorded and transcribed verbatim. Thematic data analysis was completed using NVivo 12 qualitative software (QSR International Pty Ltd. 2018). Data were coded to conceptual headings determined through open-coding in the preliminary data analysis phase.

We sorted into themes recurring terms and ideas participants used to describe conditions that shape their experiences. These themes were checked and crosschecked as more focus groups and sharing circles were conducted. We also coded for similarities and differences between groups and between First Nations and Métis groups/data. Emerging categories were compared between predominantly First Nations and Métis groups/data to determine and illustrate the majority views of all First Nations and Métis respondents. Data were cross-checked by two data analysts. Quotes are reproduced verbatim with minimal edits for clarity only.

Results

Of the 59 recruited participants (mean age 35.7 ± 11.0 years), 52 reported having at least one child or grandchild. Most identified as female (n = 46; 78%) and 13 as male (22%). Overall, 25 were single and 29 were married or living with commonlaw partners. Five participants did not indicate their marital status or educational levels. Half (n = 30) had less than a high school diploma, while 24 had a college or university education. Just over a half (n = 33; 60%) were employed full-time or part-time, and 26 (44%) were either not employed or did not indicate their employment status.

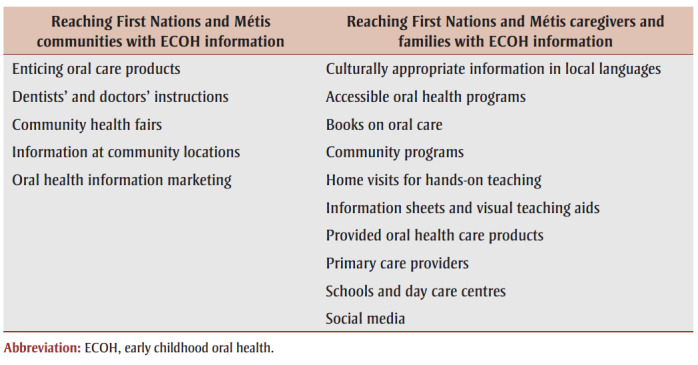

Participants suggested how best to disseminate oral health information in their communities and how best to deliver this information directly to caregivers (Table 2). Responses of female and male participants did not differ significantly. In all groups, men tended to agree with or reiterate the responses given by the women. The men seemed to implicitly defer to women regarding the oral care of young children. The women expressed the value of having men at oral health education sessions to hear about the importance of ECOH and start to take more active roles in supporting children’s oral hygiene.

Table 2. Summary of study participants’ suggestions on how best to disseminate oral health information in their communities and directly to families.

|

In this section, we present converging First Nations and Métis participants’ responses. Each participant’s statements and unique experiences are reflected in the quotes (which have been edited for clarity only).

Where did you learn about baby teeth and how to take care of them?

In learning how to care for children’s teeth, First Nations and Métis caregivers indicated six sources of oral health information: culture; caregivers and family members; dentists and primary care sources; schools and daycares; prenatal and postnatal programs; and online and print sources.

I used traditional medicine for teething and it helped sooth the gums as he was going through teething. (First Nations participant)

I learned about baby teeth and how to take care of them, I guess, just from my parents. (Métis participant)

I was in the hospital… when I was breastfeeding [I learned] from the nurse. Then I also had a public health nurse visit me at home and she also talked about [ECOH]. (Mixed group participant)

When I was going to school, they [dental hygienists] used to come in. We used to have the dental hygienist come and clean our teeth. They used to do the fluoride school. They stopped those. (Métis participant)

Just seeing these posters around like daycares and, like, the schools. (Mixed group participant)

What do you think are the best ways to get important information and tips to parents and families to keep kids’ teeth cavity-free and avoid getting serious tooth decay?

Participants’ ideas and suggestions on how best to communicate important ECOH information to Indigenous communities can be sorted into five key themes: enticing oral hygiene products, such as toothbrushes and toothpastes; seeking advice from dentists and doctors; disseminating information through community events and health fairs; providing ECOH information at specific locations in the communities; and using marketing and social media.

Enticing toothbrushes and toothpastes

Caregivers suggested that flavoured, coloured or themed oral hygiene products could help motivate children to brush their teeth and practice daily oral hygiene. This might include turning daily brushing and oral hygiene routines into a game, incentivizing brushing with rewards or providing children with toothbrushes that light up.

My daughter, she loves brushing her teeth. We have to buy her a certain kind of toothpaste with ponies on it… She is really a girlie girl so it really helped with the toothpaste. It is “My Little Pony” on her toothbrush. I think it’s what is on the toothpaste, like she’ll brush her teeth more often. And my third child, he uses [a] Ninja Turtle [toothbrush]. (Mixed group participant)

My girls also didn’t like mint—any mint, and it took me a while to be like, “Come on, girls, we’ve got to do this,” and they would be like, “I hate brushing my teeth.” But I got them the strawberry stuff that is [both] toothpaste and mouthwash … ever since then, they are like, “Oh this is pink.” (Mixed group participant)

Advice from dentists and doctors

Receiving anticipatory guidance from health professionals including dentists and medical providers was seen as integral to engaging families and encouraging them to practise good oral hygiene at home:

Go to the dentist. Yeah, because you have to, like, every 6 months. You go to the dentist for your child. (Mixed group participant)

I think the best way also is to get the doctors more informed too, because when you are pregnant, that’s when you’re trying to get all the information. [People] need all that information then. [Doctors], well make sure you’re talking about baby teeth. Bring up the dentist. (Mixed group participant)

If the dentist tells him that he’s got to do something, he’ll come home, and he’ll do it, and he’ll tell me, “This is what the [dentist] told me to do.” (Métis participant)

Community events and health fairs

Health fairs are important community events where health programs and healthrelated information can be showcased. Participants suggested that the informal atmosphere of health fairs could be conducive to engaging caregivers, families and children, delivering key oral health messages, and distributing oral hygiene supplies to families.

Health fairs to have your booths and [give out] brushes. We have a yearly health fair [where] we do that, but the whole community [does not] participate. (First Nations participant)

You could go to neighbourhood barbecues, like meet the parents and stuff, and go there and be like, “Here, this is our program. Here’s a toothbrush and toothpaste.” As a friendly thing—not be like, “Here, take it.” Just so you know, when I was a kid I loved bringing toothbrushes home. (Mixed group participant)

I think also getting kids involved, like you said you mostly reach, like, [a] parent. We go to festivals for the kids. So we have games we participate in but [we] also take part in different activities. (Mixed group participant)

Making ECOH information available in centres in the community

School gymnasiums and health centres were reported to be places families frequent and where they might easily pay attention to oral health information.

I think another way would probably be to go into the school, go into the day care[s], show the kids the pictures [of rotten teeth] because you’ll shock them when you show the teeth and I think that would probably be good. (First Nations participant)

They should put posters up everywhere, like at the day care and just wherever people will see them. (First Nations participant)

Participants also suggested being strategic in setting up booths that have oral health resources to increase community awareness at every opportunity.

I’d say that if there is something happening in the community, set up a booth. Visual is always better than paper. Having it on paper, for myself— they gave me all the information. I knew that I could read it, but I chose not to, until they came along with the baby bottle showing me how much sugar is in an apple juice, how much sugar is in a pop. Then I was like, “Holy! Now that’s not going to happen.” So visual is better than paper. (First Nations participant)

When I was in elementary [school]… the dentists would set up one of those [booths] and then parents would have that [source of information]. (Métis participant)

Information displays, including booths at community events and health fairs, encourage families and children to think about oral health, to interact with and pose questions to health promoters while develop relationships that can lead to behaviours that include seeking dental services.

Using marketing and social media to promote oral health

Participants recommended actively marketing oral health information and resources to discourage risky behaviours and to encourage healthy oral care behaviours for children.

…[T]he same scope of thinking [like] they do with cigarettes: they should put [warning labels] on the candy bars. (First Nations participant)

I … learned some lessons from the food industry, how they saturate everywhere using messages. I think the government is the one that has the money to […] focus on that. I think we need to focus on getting the [ECOH] message everywhere. Social media is better because it’s relatively cheap. Get it over and over again, like from the food industry where you are constantly exposed to foods all the time. You need to […] get the dental messages in the same kind of volume. So we have to think outside the box. (Métis participant)

Participants mentioned several ways to engage meaningfully with First Nations and Métis communities in oral health promotion. Suggestions included providing creative oral care products, meeting community members to actively discourage risk-related behaviours and promoting healthy behaviours through focused marketing.

What is the best way to get oral health information across to First Nations and Métis parents?

Ten themes emerged from among the best ways to give First Nations and Métis caregivers’ oral health information (Table 2):

Culturally appropriate information in local languages

Participants said it is important to have information and resources in the languages spoken in the communities and in ways that align with local cultural norms and expectations.

… our program provides information to young kids that is culturally appropriate. (First Nations participant)

I think you should have, like, a brochure that has certain languages [on] how to take care of a child’s teeth. Or someone who can talk to [caregivers] in person that knows about teeth and can talk to them in their language if they can’t understand English. Yeah, some people just refuse to want to take care of the child’s teeth, maybe because of religion, culture. (Mixed group participant)

Accessible oral health programs

Several participants mentioned that increased access to and availability of oral health services would also help improve ECOH.

I think that [oral health programs] should be made more open for everybody. Every child that’s 4 or 3 [years old] in the community, give them [oral hygiene products] – not just because they are in your program – and the information to go along with it. (First Nations participant)

Anything free, really, for parents, is pretty awesome … I’m a full-time stay-at-home mom with both girls. (Métis participant in a mixed group)

Books on oral care

Some caregivers suggested that books could help educate families on how to care for young children’s teeth and establish good oral health behaviours in the home.

Books that have the modules and activities on how to care for your baby’s teeth [and] when to care for them. (First Nations participant)

Yeah, books… kids’ books in the mail every month. (Mixed group participant)

Community programs

Participants recommended collaborating with existing prenatal and postnatal programs in the community. These programs already have well-established networks within communities and are a valuable resource for disseminating oral health care information in fun and engaging ways.

I think, like in the community, like [through] these little programs like Maternal Child Health. (First Nations participant)

[Prenatal programs] are a really good way to inform parents [about] what they can do in trying to help the children because that’s where it starts, right? We [moms] are the ones that are responsible for these kids. But it needs to be something that doesn’t seem like work, you know that [is] enjoyable, that gets us engaged. [Oral health promoters]… can send a couple of people once every 2 months just to come to a program like this, and we [can] play Dental Bingo or something, you know. Those are the types of things, and we learn as we’re doing it. I don’t know if that’s the only game to play but you know. (Mixed group participant)

Wiggle Giggle Munch. It’s [a program] for parents with kids about one. It’s a program where you do arts and crafts and stuff. But if you could maybe reach out to one of the people that run it and they could [help]. They give away something every day or every time we go. This week, we were given new toothbrushes, toothpastes, pamphlets, stuff like that with contact information. Maybe have more resources you can [use] about teeth, like say, [if] people can’t afford the dentist. Put a list of three or more dentists on there, because it’s so hard to research it. I’ve been trying to research, but the waiting lists are so long that by the time that’ll happen… (Mixed group participant)

Support groups or parental support groups. (Métis participant)

Baby programs—they could help reach the younger moms. (Métis participant)

Participants also said that friendly oral health promoters make programs more inviting to the people in the community.

Well, my daughter was in the [community] program, but she left the program because she didn’t like the way she was being treated. So, she never came back to anything. She felt she was being talked down to. She had a lot of issues. So she has a 5-month-old baby now, and she doesn’t want to join anything because [workers] are not supposed to talk down to community members: you are there to help them, not put them down. (First Nations participant)

I think now that myself and my coworker are in the community for an extended period of time, we are making those connections stronger [than] before for the first time. I think we now have stable staffing at our centre, and we are building those relationships. So, I think we are getting more information out there and people [are] trusting us, because we’ve been here, we’re still going to be here again for the next step. (Métis participant)

Home visits for hands-on teaching

Some participants indicated that visiting families at home may lead to adoption of healthy oral health-related behaviours among young children.

I go into the house and I teach them, show them or explain to them whatever, but I know there is that, like they brush their teeth at the day care, they brush their teeth at Head Start [program], so I think it begins, like, at home. (First Nations participant)

I’m not even sure, just talking to our parents and [a] one-on-one kind of thing. Some people would say like go online and that, but who really has time to go looking for stuff online. (First Nations participant)

I think when you want parents to start taking care of their kids, it’s better to have that one-on-one person contact, to have a direct link to that parent or just to make sure the parents are informed. (Métis participant)

Information sheets and visual teaching aids

Some participants said they do not frequent dental offices. This made it difficult for them to get information from office newsletters or dental clinic displays. Instead, they recommended mailing out newsletters. Some suggested distributing pamphlets and brochures with images of severe early childhood caries to families.

Sending home an information package to people who are expecting or have a new child and then updating that information for older kids too, because the older kids need different kinds of care. (First Nations participant)

Just mail them a newsletter about how to take care of [a] child’s teeth. Some people come to the program. We can get their names and ask if they are interested in getting a newsletter. (Mixed group participant)

Meetings like this or something like brochures, mailboxes or something. (Métis participant)

Community letters. (Métis participant)

Participants also said that they were willing to receive text messages and phone calls with key oral health messages.

My dentist texts me all the time. (Mixed group participant)

Provided oral hygiene supplies

Participants said that receiving free oral health care products (i.e. toothbrushes and toothpaste) was helpful, particularly for those who may not be able to afford those items regularly.

Also, I think giving resources to the families sometimes. Like you know, who has enough money to buy 10 kids’ toothbrushes that are $3.00 And they only get a welfare check that is $600.00, that means it has to last [for] groceries all month. So, I think, like, if they were standing in a social assistance line, social assistance says, “Oh here, look at our free toothbrush for your kids and tube of toothpaste.” Then it goes through the line. This way they have that resource. How is that kid going to learn if mom is not doing it and she can’t afford a toothbrush? (First Nations participant)

I’d say give them a toothbrush and toothpaste. Hand them out. If I knew somebody like as a friend, I would give him a toothbrush and toothpaste for their kids. Well, maybe if they come here and they want to know more about health care or more about the teeth, give them a toothbrush, toothpaste and maybe a letter saying steps on how to brush their teeth. (Métis participant in mixed group)

Primary care providers

Participants recommended that primary care providers, including public health nurses, be involved in disseminating oral health care information and resources, as they are more likely to see families early on in the process of taking care of children.

[Public health nurses] can check your baby’s teeth, stop by here real quick for a checkup and, like I said earlier, to give information packages out. So yeah, just making sure more people are getting the [oral health information] every once in a while. (First Nations participant)

When the public health nurse comes to the school, usually you get a lot of their information. They always bring toothbrushes. The girls love those. That’s the most common way—through those workshops with the public health nurses. Lots and lots of posters. I’ve read so many. (Mixed group participant)

Schools and day care centres

Participants reported learning about oral care from daycares and schools, indicating that these places are important venues for promoting oral health.

The best way, like I said, is going into the schools. I think [this] is big because you can call the teacher and parents, but for me, to go into the schools is a lot more. I don’t even know what’s happening right now with any of the schools for oral health. (First Nations participant)

The way my brain is interpreting [ECOH] is that [this] is the individual’s responsibility and [that] the best way for them would be, like in schools for younger kids, and then having charts up, something like, “Oh, did you brush your teeth today?” and like, “Put your sticker on. Here’s your prize.” You know what I mean? Having that and reminding children constantly, constantly and constantly. If the parents aren’t doing it, then the school’s doing it so it will be intact. (Mixed group participant)

Social media

Participants recommended using social media as a practical way to reach some people.

I’d say Facebook, media, like draw on their phones, make like bulletins, and send down bulletins and ... maybe more commercials for kids like on their cartoon channels or whatever if they are watching something. (Mixed group participant)

Everybody’s on social media right now. So try to find a way to implement all the information on there. Not just like a Google search, actually like media ads, Facebook or Twitter and stuff like that. (Mixed group participant)

Another suggested strategy was to have people share their personal experiences of having a child with early childhood caries.

I think more outreach. If I saw someone more like me talking, talking to me about teeth, I’d be more open to it, I guess. Because lots of people… have perfect teeth ... But if you don’t [have perfect teeth] like me, because I have a calcium deficiency so my teeth decay a lot faster than others. (Mixed group participant)

Discussion

This study engaged First Nations and Métis community members to identify approaches to promote ECOH and address the oral health disparity of early childhood caries in Indigenous populations. Several themes emerged from among the strategies for reaching and involving First Nations and Métis caregivers and families in oral health promotion. A variety of approaches were suggested on how to disseminate information to First Nations and Métis communities and caregivers specifically.

It is worth noting that a lack of access to oral health professionals may be resulting in community members seeking information from less reliable sources. Professionally driven, evidence-based oral health information and resources provided to communities could increase oral health care adherence and related behaviours of parents, grandparents and caregivers. Studies in other health care areas support this recommendation.24,25

Approaches that have been effective against early childhood caries in lowerrisk populations have not translated consistently to Indigenous communities.26,27 A recent randomized trial of oral health promotion with American Indian communities had tepid results; the study concluded that interventions may need to be personalized and shaped by cultural perspectives while also addressing the social determinants of health.27,28 Given that First Nations and Métis populations are distinct, tailored approaches to prevention are warranted.1,29 These approaches, in seeking to modify health behaviours, advocate for a holistic perspective that takes all determinants of Indigenous health into account. These determinants of health include employment and income, education, food security, health care systems awareness and resources.30

A Canadian review of dental interventions for early childhood caries among Indigenous children recommends incorporating cultural and traditional knowledge as well as integrating and aligning ECOH promotion activities into existing community services and programs.14 This is in keeping with study participants’ recommendations to use culturally appropriate oral health promotion strategies that include Indigenous worldviews.

Cultural safety and appropriateness is particularly important for First Nations and Métis peoples in light of the history of the colonial health care system in Canada.31,32 It is important to establish trusting relationships and facilitate culturally sensitive care. For example, health promotion conducted by Indigenous persons may be more effective at promoting trust among Indigenous families.33

The importance of making personal connections in order to reach families more effectively was determined in a previous study by the same research team.34 Indigenous caregivers recommended asking Elders to share traditional knowledge and also use the language of the population to communicate information.34 Educating community oral health workers and Indigenous and non-Indigenous health care professionals on culturally safe practices is a critical step in advancing oral health promotion and preventing early childhood caries.35

In calling for the sharing of information through existing community health programs, study participants highlighted the role of long-term and close relationships between those involved.36

Some participants suggested that sending ECOH key messages via text messaging to parents and caregivers with young children may have advantages of the recipients getting and responding to information easily and faster. Studies have also shown that sending key oral health messages via text can improve parental knowledge and change oral health behaviours.37-39 The challenge lies in that many rural Indigenous communities do not have basic cellular service, let alone Wi-Fi.

Participants also recommended engaging dental and primary care providers in efforts to prevent early childhood caries. There is a case for engaging non-dental primary care providers to disseminate ECOH information and possibly conduct caries risk assessments (CRAs). A recent systematic review revealed that non-dental providers can successfully perform CRA to control early childhood caries.40

Several dental and pediatric organizations have developed CRA tools, some specifically for use by non-dental providers.41 Such CRA tools can be used to screen children with limited access to dental care, determine their risk and provide prevention services, including fluoride varnish, anticipatory guidance and referral to a dental office.41

A recent Canadian study found that primary care providers in Indigenous communities are willing to incorporate preventive oral care into their clinics.42 This aligns with American Academy of Pediatrics and Canadian Paediatric Society suggestions to work interprofessionally to address early childhood caries in Indigenous communities.43,44

A Canadian CRA tool has been developed for use by non-dental primary care providers on children younger than 6 years. The Canadian Caries Risk Assessment Tool (<6 Years)45 may help improve young Indigenous children’s access to oral health assessments and referrals for dental care. It could be a sustainable option in communities where there are few or no dental professionals.

Fun oral hygiene products and books that show how to care for teeth attract children’s attention and encourage healthy oral hygiene habits of brushing, flossing and reducing intake of sweetened beverages. 46,47 While such resources may be widely available elsewhere, they are not easily accessible or affordable in rural and/or remote First Nations and Métis communities. Study participants suggested it would be useful if copies of such resources were mailed to their homes in the communities.

The Scaling Up the Healthy Smile Healthy Child team have taken these ideas and suggestions and are incorporating them in our ECOH promotion efforts with First Nations and Métis communities. The team also maintains a Facebook page (https:// www.facebook.com/HealthySmileHappy Child/), a YouTube channel (https://www .youtube.com/channel/UCd6ZyKUqiqn BEhQJoO-hrjg) and social media links (https://wrha.mb.ca/oral-health/early -childhood-tooth-decay/) to share information with communities and caregivers.

Strengths and limitations

Our Implementation Research Team includes Indigenous community members, Indigenous community leadership (including FNHSSM and MMF), health professionals, local, provincial and national decision-makers and academics. This team structure promotes the sharing of recommendations with stakeholders in real time. This study’s partnership with the First Nations and Métis organizations and communities also made it possible to communicate with participants and access communities. Having urban and rural groups provided well-rounded perspectives on families’ experiences and knowledge of available oral health services.

Our findings could inform First Nations and Métis community programs and improve uptake by community members. As rural and remote Indigenous communities often face similar health issues and health care access challenges, program coordinators and managers may find the participants’ suggestions suitable for informing change in their own contexts. However, urban and rural experiences may differ when considered on their own, which this study has not explicitly focused on analyzing. The results may also not be generalizable to every First Nations and Métis community in Canada. Robustness to the recommended strategies can be added by increasing the sample size and including the perspectives of other communities in future studies.

Conclusion

First Nations and Métis communities and caregivers’ ideas and suggestions on how to promote ECOH and reduce early childhood caries point to the importance of implementing widely available approaches and resources in ways that encourage uptake in specific contexts. Indigenous populations do not have access to services that the larger population takes for granted. Targeted and funded oral health promotion activities with Indigenous promoters at the forefront may close existing gaps. Social media may also be a way to send many people important ECOH information.

Acknowledgements

This study was made possible by an Implementation Research Team grant for the “Scaling up the Healthy Smile Happy Child initiative: tailoring and enhancing a community development approach to improve early childhood oral health for First Nations and Metis children” from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). RS holds a CIHR Embedded Clinician Researcher Salary Award in “Improving access to oral health care and oral health care delivery for at-risk young children in Manitoba.”

We also thank the First Nations and Métis communities that participated in the study and freely shared their experiences and knowledge with the research team.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Authors’ contributions and statement

GKA: Study design, data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript drafting and revision; RS: Study conceptualization and design, data interpretation and manuscript revision; JS: Data interpretation and manuscript revision; RC: Study conceptualization; DD: Study design and data acquisition; MS: Study design and data acquisition; JE: Study design and manuscript revision; MB: Study design and manuscript revision; LD: Study design and manuscript revision; KHS: Study design and manuscript revision; FC: Study design and manuscript revision; TD: Data acquisition; BP: Data acquisition; JL: Data acquisition; MM: Study design.

The content and views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.

References

- Schroth RJ, McNally M, Harrison R, et al. Pathway to oral health equity for First Nations, Mtis, and Inuit Canadians: knowledge exchange workshop. J Can Dent Assoc. 2015:f1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison PJ, Bailey T, Beattie L, et al, et al. Canadian Academy of Health Sciences. Ottawa(ON): 2014. Improving access to oral health care for vulnerable people living in Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Alazmah A, et al. Early childhood caries: a review. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2017:732–7. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10024-2116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tantawi M, Folayan MO, Mehaina M, et al, et al. Prevalence and data availability of early childhood caries in 193 United Nations countries, 2007-2017. El Tantawi M, Folayan MO, Mehaina M, et al. 2018;108((8)):1066–72. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine J, Holve S, Krol D, Schroth R, et al. Early childhood caries in Indigenous communities: a joint statement with the American Academy of Pediatrics. Paediatr Child Health. 2011;16((6)):351–64. doi: 10.1093/pch/16.6.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroth RJ, et al. The state of dental health in the north. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2006;65((2)):98–100. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v65i2.18096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelopoulou MV, Shanti SD, Gonzalez CD, Love A, Chaffin J, et al. Association of food insecurity with early childhood caries. J Public Health Dent. 2019;79((2)):102–8. doi: 10.1111/jphd.12299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macintosh AC, Schroth RJ, Edwards J, Harms L, Mellon B, Moffatt M, et al. The impact of community workshops on improving early childhood oral health knowledge. Pediatr Dent. 2010;32((2)):110–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin MS, Harrison RL, et al. Understanding parents’ oral health behaviors for their young children. Qual Health Res. 2009;19((1)):116–27. doi: 10.1177/1049732308327243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroth RJ, Edwards JM, Brothwell DJ, et al, et al. Evaluating the impact of a community developed collaborative project for the prevention of early childhood caries: the Healthy Smile Happy Child project. Rural Remote Health. 2015;15((4)):3566–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawlor ER, Cupples ME, Donnelly M, Tully MA, et al. Implementing community-based health promotion in socio-economically disadvantaged areas: a qualitative study. Implementing community-based health promotion in socio-economically disadvantaged areas: a qualitative study. J Public Health (Oxf) 2019 doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdz167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haldane V, Chuah FL, Srivastava A, et al, et al. Community participation in health services development, implementation, and evaluation: a systematic review of empowerment, health, community, and process outcomes. PLoS One. 2019;14((5)):e0216112–27. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0216112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroth RJ, Edwards JM, Moffatt ME, et al. International Association of Circumpolar Health Publishers. Oulu(SU): 2010. Healthy Smile, Happy Child: evaluation of a capacity-building early childhood oral health promotion initiative. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence HP, Dent J, et al. Oral health interventions among Indigenous populations in Canada. Int Dent J. 2010;60((3 Suppl 2)):229–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cidro J, Maar M, Peressini S, et al, et al. Strategies for meaningful engagement between community-based health researchers and First Nations Participants. Front Public Health. 2017 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coombe CM, Schulz AJ, Guluma L, et al, et al. Enhancing capacity of community-academic partnerships to achieve health equity: results from the CBPR Partnership Academy. Health Promot Pract. 2020;21((4)):552–63. doi: 10.1177/1524839918818830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyoon-Achan G, Lavoie J, Kinew K, et al, et al. Innovating for transformation in First Nations health using community-based participatory research. Qual Health Res. 2018:1036–49. doi: 10.1177/1049732318756056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- the path to First Nations information governance. Ottawa (ON): FNIGC. Ottawa(ON): 2014. Ownership, control, access and possession (OCAP™): the path to First Nations information governance. [Google Scholar]

- University of Manitoba. Winnipeg(MB): 2015. Framework for research engagement with First Nation, Metis, and Inuit peoples. [Google Scholar]

- Ermine W, Sinclair R, Jeffery B, et al. The ethics of research involving Indigenous Peoples Regina (SK): Indigenous Peoples’ Health Research Centre; 2004. Indigenous Peoples’ Health Research Centre. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- Braun KL, Browne CV, Ka’opua LS, Kim BJ, Mokuau N, et al. Research on indigenous elders: from positivistic to decolonizing methodologies. Gerontologist. 2014;54((1)):117–26. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnt067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e L, et al. Practical application of an indigenous research framework and Indigenous research methods: sharing circles and Anishnaabe symbol-based reflection. Int J Qual Methods. 2009;8((1)):21–40. [Google Scholar]

- Morse JM, Stern PN, Corbin J, Bowers B, Charmaz K, Clarke AE, et al. Developing grounded theory: the second generation. Left Coast Press, Inc. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Reading SR, Go AS, Fang MC, et al. Health Literacy and Awareness of Atrial Fibrillation. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6((4)):e005128–40. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.005128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roh YH, Koh YD, Noh JH, Gong HS, Baek GH, et al. Effect of health literacy on adherence to osteoporosis treatment among patients with distal radius fracture. Arch Osteoporos. 2017;12((1)):42–40. doi: 10.1007/s11657-017-0337-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2010 Symposium on early childhood caries in American Indian and Alaska Native children: Panel report. American Dental Association. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Braun PA, Quissell DO, Henderson WG, et al, et al. A cluster-randomized, community-based, tribally delivered oral health promotion trial in Navajo Head Start Children. J Dent Res. 2016;95((11)):1237–44. doi: 10.1177/0022034516658612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albino JE, Orlando VA, Dent J, et al. Promising directions for caries prevention with American Indian and Alaska Native children. Int Dent J. 2010;60((3 Suppl 2)):216–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroth RJ, McNally M, Harrison RL, et al. Complete proceedings: pathway to oral health equity for First Nations, Mtis, and Inuit Canadians: knowledge exchange workshop. Schroth RJ, McNally M, Harrison RL. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reading C, Wien F, et al. Health inequalities and social determinants of Aboriginal peoples’ health. National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Auger M, Crooks CV, Lapp A, et al, et al. The essential role of cultural safety in developing culturally-relevant prevention programming in First Nations communities: lessons learned from a national evaluation of Mental Health First Aid First Nations. Eval Program Plann. 2019:188–96. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2018.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne AJ, Varcoe C, Lavoie J, et al, et al. Enhancing health care equity with Indigenous populations: evidence-based strategies from an ethnographic study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16((1)):544–96. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1707-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallesi S, Wood L, Dimer L, Zada M, et al. “In Their Own Voice” – Incorporating underlying social determinants into Aboriginal health promotion programs. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15((7)):E1514–96. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15071514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prowse S, Schroth RJ, Wilson A, et al, et al. Diversity considerations for promoting early childhood oral health: a pilot study. Int J Dent. 2014:175084–96. doi: 10.1155/2014/175084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villalta J, Askaryar H, Verzemnieks I, Kinsler J, Kropenske V, Ramos-Gomez F, et al. Developing an effective community oral health workers—“Promotoras” model for Early Head Start. Front Public Health. 2019 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters KL, Johnson-Jennings M, Stroud S, et al, et al. Growing from our roots: strategies for developing culturally grounded health promotion interventions in American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian Communities. Prev Sci. 2020;21((Suppl 1)):54–64. doi: 10.1007/s11121-018-0952-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrelli B, Henshaw M, Endrighi R, et al, et al. An interactive parent-targeted text messaging intervention to improve oral health in children attending urban pediatric clinics: feasibility randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2019;7((11)):e14247–64. doi: 10.2196/14247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurling R, Claessen JP, Nicholson J, Schafer F, Tomlin CC, Lowe CF, et al. Automated coaching to help parents increase their children’s brushing frequency: an exploratory trial. Community Dent Health. 2013;30((2)):88–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashemian TS, Kritz-Silverstein D, Baker R, et al. Text2Floss: the feasibility and acceptability of a text messaging intervention to improve oral health behavior and knowledge. J Public Health Dent. 2015;75((1)):34–41. doi: 10.1111/jphd.12068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caries-risk assessment and management for infants, children, and adolescents. Pediatr Dent. 2017:197–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George A, Sousa MS, Kong AC, et al, et al. Effectiveness of preventive dental programs offered to mothers by non-dental professionals to control early childhood dental caries: a review. BMC Oral Health. 2019;19((1)):172–204. doi: 10.1186/s12903-019-0862-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ElSalhy M, Gill M, Isaac DM, Littlechild R, Baydala L, Amin M, et al. Integrating preventive dental care into general paediatric practice for Indigenous communities: paediatric residents’ perceptions. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2019;78((1)):1573162–204. doi: 10.1080/22423982.2019.1573162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine J, Holve S, Krol D, Schroth RJ, et al. Policy statement – early childhood caries in indigenous communities. Paediatr Child Health. 2011;16((6)):351–7. doi: 10.1093/pch/16.6.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Early childhood caries in Indigenous communities. Pediatrics. 2011;127((6)):1190–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroth R, et al. University of Manitoba. Winnipeg(MB): 2019. Canadian Caries Risk Assessment Tool (<6 Years) [Google Scholar]

- Avery A, Bostock L, McCullough F, et al. A systematic review investigating interventions that can help reduce consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages in children leading to changes in body fatness. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2015 doi: 10.1111/jhn.12267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ML, Lemon SC, Clausen K, Whyte J, Rosal MC, et al. Design and methods for a community-based intervention to reduce sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among youth: H2GO. BMC Public Health. 2016;16((1)):1150–8. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3803-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]