Abstract

A 10-year-old child had painful periorbital swelling in the left eye. It was diagnosed as preseptal cellulitis and treated with oral antibiotics. Three days later, the ocular condition worsened so the child was referred for further management. On examination, the child had a temperature of 102 °F. Ocular examination revealed proptosis, restricted ocular movements and a relative afferent pupillary defect in the left eye. Ocular examination of the right eye was normal. There was a history of recurrent episodes of cold in the past. CT scan orbit and sinuses revealed signs of orbital cellulitis with sinusitis on the left side. The child was treated with parenteral antibiotics and endoscopic sinus surgery. A child presenting with unilateral periorbital swelling needs to be thoroughly evaluated. It is important to differentiate orbital cellulitis from preseptal cellulitis. Orbital cellulitis is an emergency and delay in diagnosis can lead to vision and life-threatening intracranial complications.

Keywords: eye, infections, ophthalmology, pupil, otolaryngology / ENT

Background

Orbital and periorbital infections are more common in the paediatric age group.1 Children often present with unilateral periorbital swelling with pain. It could be either preseptal cellulitis or orbital cellulitis. Preseptal cellulitis is the inflammation of the orbital tissues limited anterior to the orbital septum, whereas inflammation of tissue posterior to the orbital septum is termed as orbital cellulitis.2 This classification not only is useful in the anatomical localisation of the infection but also has therapeutic and prognostic implications. It is important to differentiate between two forms of cellulitis, as the aetiology, line of management and prognosis of these two conditions are completely different. Orbital cellulitis is an emergency and delay in diagnosis can lead to blindness and life-threatening intracranial complications.1

Sinusitis is the most common predisposing factor for orbital cellulitis. In a majority of cases, there is a direct spread of infection from ethmoid sinus to orbit.1 CT imaging is required for detailed evaluation and differentiation of preseptal cellulitis from orbital cellulitis. Herein, we report a case of orbital cellulitis where treatment with parenteral antibiotics and sinus surgery prevented vision and life-threatening complications, despite late referral.

Case presentation

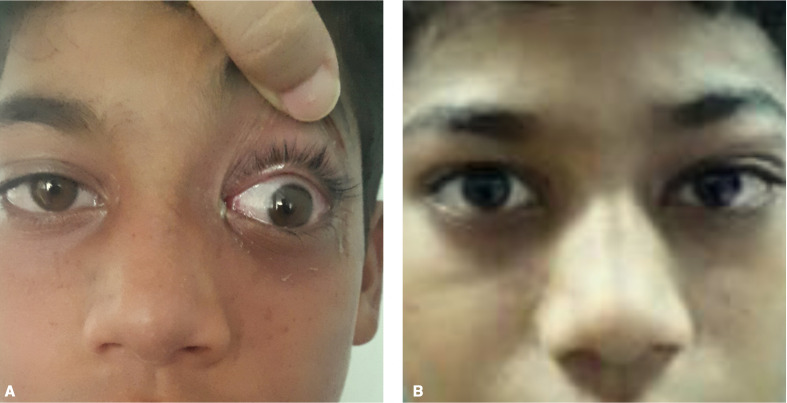

A 10-year-old Indian child had painful periorbital swelling in the left eye (LE) (figure 1A). It was diagnosed as preseptal cellulitis by a primary care physician and treatment with oral antibiotics was commenced. After 3 days of treatment, the periorbital swelling further worsened along with proptosis, therefore, the patient was referred for further management. There was a history of severe cough and cold 10 days ago for which no treatment was sought. The patient also gave a history of recurrent episodes of cold in the past. There was no history of trauma, insect bite, any surgical intervention or systemic comorbidity.

Figure 1.

(A) Photograph showing severe periorbital swelling in the left eye. (B) Photograph showing severe periorbital oedema with proptosis and ophthalmoplegia in the left eye.

The child was conscious and well oriented. He had a temperature of 102 °F with tachycardia. The best-corrected visual acuity in the right eye (RE) was 20/20 and in the LE, it was 20/200. Ophthalmological examination of the LE revealed severe periorbital oedema, proptosis, ophthalmoplegia (figure 1B) and a relative afferent pupillary defect. LE fundus examination revealed a slightly swollen disc with venous engorgement but no evidence of central retinal vein or artery occlusion. Ocular examination of the RE was within normal limits.

Investigations

Complete blood count revealed leukocytosis (13 900 cells/mm3) with elevated neutrophils (68%). CT scan orbit and paranasal sinuses showed proptosis with signs of frontal, ethmoid and maxillary sinusitis with the involvement of the orbit on the left side (figure 2A–C). A diagnosis of LE orbital cellulitis with sinusitis was made. Hence, the patient was referred to seek otorhinolaryngologist opinion and was admitted under the joint care of ophthalmologists and otorhinolaryngologist.

Figure 2.

CT images of orbit and paranasal sinuses. (A) Axial scan showing left eye proptosis with signs of ethmoid sinusitis and involvement of orbital tissue, (B) coronal section showing the involvement of left frontal sinus and orbital tissue and (C) sagittal section showing maxillary sinusitis with orbital involvement.

Differential diagnosis

Unilateral periorbital swelling in a child could be because of allergy or infection. An allergic reaction will be acute in onset with pruritus, periorbital dermatitis, eyelid oedema, erythema and conjunctival injection.3 The ocular movements, vision and pupils will be normal. There will be a history of topical medication, insect bite/allergen. In case of infection, it could be preseptal cellulitis or orbital cellulitis. The clinical signs will help distinguish between these two forms of cellulitis. Preseptal cellulitis is characterised by periorbital oedema with normal ocular movements, normal vision and absence of proptosis.4 5 In orbital cellulitis, along with periorbital oedema, there will be limited ocular motility with decreased vision and proptosis.6 Fever with leukocytosis is a prominent feature in children with orbital cellulitis. CT imaging of orbit and paranasal sinuses is the investigation of choice for differentiating the two forms of cellulitis.

Treatment

Intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotic (amoxicillin–clavulanic acid 30 mg/kg body weight) was given 12 hourly for 5 days, followed by oral amoxicillin–clavulanic acid 375 mg two times per day for 5 days. Tablet ibuprofen (10 mg/kg body weight) was given three times a day along with topical antibiotic (tobramycin 0.3% w/v) four times and nasal decongestant drops (0.025% oxymetazoline) two times a day. In liaison with the otorhinolaryngologist, the patient underwent functional endoscopic sinus surgery under general anaesthesia, after 24 hours of antibiotic therapy. Postoperatively, oral anti-inflammatory drugs and topical antibiotics were continued for a total duration of 1 week.

Outcome and follow-up

The child responded well to treatment. There was a noticeable decrease in proptosis and lid oedema. At 1-week follow-up, there was mild proptosis with ophthalmoplegia and a persisted subtle LE relative afferent pupillary defect (figure 3A). The patient showed complete recovery at 3 weeks follow-up (figure 3B).

Figure 3.

(A) Photograph after treatment showing mild proptosis with ophthalmoplegia in the left eye at 1 week follow-up. (B) Photograph at 3 weeks follow-up showing a complete recovery in the left eye.

Discussion

Orbital and periorbital infections can affect all age groups but they are more common in the paediatric age group.1 2 4 They are at a higher risk of developing severe ocular and intracranial complications.1 When a child presents with signs of inflammation in the periorbital area, it is important to differentiate preseptal cellulitis from orbital cellulitis. Preseptal cellulitis is characterised by periorbital oedema, warmth and tenderness with unaffected visual acuity, absence of proptosis and normal ocular movements.4 5 In orbital cellulitis, along with periorbital oedema, there is proptosis, limited ocular motility and decreased vision.6 Sometimes the periorbital oedema is so severe, precludes eye examination, thus making the distinction between preseptal and orbital cellulitis difficult.

Fever with leucocytosis is a prominent feature in children with orbital cellulitis. A history of upper respiratory tract infection before the onset of the disease is common.7 In 90% of cases, the most common cause of orbital cellulitis is a direct spread of infection from sinuses, most commonly from ethmoid sinus.1 7 CT scan with contrast is the investigation of choice for differentiation of preseptal from orbital cellulitis, for grading of orbital cellulitis and localisation of sinus infection.1 2

Goodyear et al reported a similar case of unilateral periorbital swelling in a 14-year-old boy. He was diagnosed as an allergic reaction and treated with antiallergic drugs. After 4 days, the periorbital swelling worsened with proptosis and restricted ocular movements. The child was treated with endoscopic sinus surgery and intravenous antibiotics.

Orbital cellulitis is an emergency, which requires early diagnosis and aggressive management. Delay in diagnosis can lead to complete loss of vision secondary to optic neuritis resulting from infection, inflammation and compression or central retinal artery occlusion. It is a life-threatening disease as infection can spread to the brain and cause cavernous sinus thrombosis, meningitis and brain abscess.

Learning points.

A child presenting with unilateral periorbital swelling needs to be thoroughly evaluated.

It is important to differentiate preseptal from orbital cellulitis, as the aetiology, line of management and prognosis of these two conditions are completely different.

Orbital cellulitis is an emergency that requires early diagnosis and aggressive management to avoid serious complications.

A high index of suspicion with an early referral from primary care is vital for optimal management of orbital cellulitis.

Footnotes

Twitter: @SarojGu11000096

Contributors: Conception and design, acquisition of data—SG. Drafting the case report or revising it critically for important intellectual content—DS. Final approval of the version published—SG.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Parental/guardian consent obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Jain A, Rubin PA. Orbital cellulitis in children. Int Ophthalmol Clin 2001;41:71–86. 10.1097/00004397-200110000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buchanan MA, Muen W, Heinz P. Management of periorbital and orbital cellulitis. Paediatr Child Health 2012;22:72–7. 10.1016/j.paed.2011.12.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodyear PWA, Firth AL, Strachan DR, et al. Periorbital swelling: the important distinction between allergy and infection. Emerg Med J 2004;21:240–2. 10.1136/emj.2002.004051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watts P Preseptal and orbital cellulitis in children. Paediatr Child Health 2016;26:1–8. 10.1016/j.paed.2015.10.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee S, Yen MT. Management of preseptal and orbital cellulitis. Saudi J Ophthalmol 2011;25:21–9. 10.1016/j.sjopt.2010.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cannon PS, Mc Keag D, Radford R, et al. Our experience using primary oral antibiotics in the management of orbital cellulitis in a tertiary referral centre. Eye 2009;23:612–5. 10.1038/eye.2008.44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaudhry IA, Al-Rashed W, Arat YO. The hot orbit: orbital cellulitis. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol 2012;19:34–42. 10.4103/0974-9233.92114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]