Abstract

Objective

To predict the cost and health effects of routine use of whole-genome sequencing (WGS) of bacterial pathogens compared with those of standard of care.

Design

Budget impact analysis was performed over the following 5 years. Data were primarily from sequencing results on clusters of multidrug-resistant organisms across 27 hospitals. Model inputs were derived from hospitalisation and sequencing data, and epidemiological and costing reports, and included multidrug resistance rates and their trends.

Setting

Queensland, Australia.

Participants

Hospitalised patients.

Interventions

WGS surveillance of six common multidrug-resistant organisms (Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Enterococcus faecium, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Enterobacter sp and Acinetobacter baumannii) compared with standard of care or routine microbiology testing.

Primary and secondary outcomes

Expected hospital costs, counts of patient infections and colonisations, and deaths from bloodstream infections.

Results

In 2021, 97 539 patients in Queensland are expected to be infected or colonised with one of six multidrug-resistant organisms with standard of care testing. WGS surveillance strategy and earlier infection control measures could avoid 36 726 infected or colonised patients and avoid 650 deaths. The total cost under standard of care was $A170.8 million in 2021. WGS surveillance costs an additional $A26.8 million but was offset by fewer costs for cleaning, nursing, personal protective equipment, shorter hospital stays and antimicrobials to produce an overall cost savings of $30.9 million in 2021. Sensitivity analyses showed cost savings remained when input values were varied at 95% confidence limits.

Conclusions

Compared with standard of care, WGS surveillance at a state-wide level could prevent a substantial number of hospital patients infected with multidrug-resistant organisms and related deaths and save healthcare costs. Primary prevention through routine use of WGS is an investment priority for the control of serious hospital-associated infections.

Keywords: microbiology, health economics, infection control

Strengths and limitations of this study.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the projected budget impact for a local government to invest in routine whole-genome sequencing of serious bacterial pathogens to assist hospital infection control teams.

Analyses relied on recent outcomes from sequencing data to identify clusters, hospitalisation data, prevalence of healthcare-associated infections and detailed costing of all hospital resources, while sensitivity analyses assessed variation in inputs and stability of results.

Projected cost savings of a whole-genome sequencing strategy rely on the success of infection control teams to act decisively and effectively on the information of patient clusters.

Introduction

Healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) are the most common complications among hospitalised patients in Australia.1 The associated economic burden is enormous, resulting in longer hospital stays, higher treatment costs, and in severe cases intensive care unit stays and bed closures. Rates of bacterial infections causing septicaemia and deaths rose from the 1980s but have stabilised since 2000.2 Consequently, substantial resources are devoted to controlling HAIs, especially for multidrug-resistant organisms (MROs), with strict infection control practices operating in most hospitals.

Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) of pathogens can identify genetically related isolates and identify patients involved in an outbreak. WGS can confirm or refute suspected related cases of infectious pathogens, discriminate between different strains and classify novel pathogens.3 By detecting different strains with varied transmissibility, patients can be better managed by the infection control team. Currently, usual laboratory tests to confirm infectious pathogens do not provide this granular information on different strains. Through WGS, multiple isolates can be analysed together to uncover the evolution of the pathogen (phylogenetics) and transmission history (who infected whom). In the future, sequencing is expected to identify information about resistance to certain antibiotics, which has potential to guide antibiotic treatment.

There is an emerging body of work on the economic value of WGS surveillance in hospital practice.4–6 While WGS of human tissue can be expensive,7 bacterial and viral genomes are less complex and the sequencing cost is less than one-tenth that for a human genome.5 Nevertheless, whole hospital WGS screening is not yet economical so more judicious uses of pathogen WGS in a confirmatory role have been evaluated. In general, health economic studies have demonstrated favourable cost-effectiveness of WGS compared with standard of care. WGS can lead to reduced transmission and infection rates and lower overall costs.4–6 These promising findings pave the way for a budget analysis to be performed to quantify the actual cost outlays required to adopt WGS on a population-wide scale.

Queensland is the second largest and third most populous state in Australia with a population of over five million. The network of public hospitals spans a large geographical area across 16 hospital and health services. For WGS surveillance in infection control to be routinely implemented in publicly funded Queensland hospitals, a budget impact analysis can assist in resource allocation and planning. The purpose of this study was to undertake a 5-year budget impact analysis of WGS surveillance compared with standard of care using an epidemiological approach from the state government perspective.

Methods

Overview

The analysis focused on six MROs: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Escherichia coli (ESBL E. coli), vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium (VRE), ESBL-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae (ESBL K. pneumoniae), carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales (CPE) and carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (CRAB). These organisms were selected because they are subject to hospital outbreaks with serious consequences and accounted for 95% of all sequenced isolates. A review of Australian hospital infection data, government reports and published studies provided the estimates for the analysis. Sequencing data to identify clusters were examined over 2 years. Costs were aggregated for the state of Queensland based on the expected number of MRO isolates arising in Queensland hospital patients. Costs were calculated annually across 5 years from the base year 2020. The International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research good practice guidelines for budget impact analyses provided the framework for this work.8

Estimated patients infected with MROs

Each quarter, there are 409 972 hospitalisations in Queensland, and these figures were assumed to be stable over the next 5 years with full hospital capacity.9 A recent Australian study showed that the point prevalence of HAIs in Australia was 9.9% of all hospitalisations.10 Using Russo et al’s10 data on 363 HAIs, the frequency of organisms detected was 50 (14%) S. aureus, 32 (9%) E. coli, 21 (6%) E. faecium, 16 (4%) K. pneumoniae, 7 (2%) E. cloacae and 4 (1%) A. baumannii (with 216 (62%) other organisms making up the remainder). Although these HAI data were national and the prevalence varied between hospitals, variations were within expected statistical limits to conclude HAIs could reasonably apply to Queensland.10

For each pathogen, the multidrug resistance rates were based on Wozniak et al,11 according to site of infection—bloodstream, urinary tract and respiratory tract11—and the Australian Group on Antimicrobial Resistance Sepsis Outcomes Programs: 2018 Report.12

We estimated the total number of Queensland patients colonised or infected (N) for each of the six organisms of interest using Equation 1,

| (1) |

where TH is the total number of hospitalisations, HAIs is healthcare-associated infections, Org is the organism of interest, MDR is multidrug resistance and the denominator is the infection fraction (I/(I+C)). The infection fraction is the number of infections (I) as a fraction of the total number of colonisations (C) and infections (I). This is required on the denominator to increase the N and account for colonisations and infections as the true burden of HAI numbers. The infection fraction was calculated from 5 years of MRO surveillance data from the Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital (RBWH), Australia (table 1). The RBWH is the largest public hospital in Australia. Sensitivity analyses were performed on the 95% CI for each of these separate variables.

Table 1.

Parameter values used in estimating the number of hospitalised patients affected by MROs

| Variable | Estimate (95% CI) | Source |

| Number of Queensland hospital admissions per quarter |

409 972 (348 476 to 462 243) | Queensland Health9 |

| Prevalence of all hospitalisations with HAI (%) |

9.9 (8.8 to 11.0) | Russo et al 10 |

| Species of all HAIs* (%) | ||

| Staphylococcus aureus | 13.8 (10.2 to 17.3) | Russo et al 10 |

| Escherichia coli | 8.8 (5.9 to 11.7) | |

| Enterococcus faecium | 5.8 (3.4 to 8.2) | |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 4.4 (2.3 to 6.5) | |

| Enterobacter cloacae | 1.9 (0.5 to 3.3) | |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | 1.1 (0.0 to 2.2) | |

| Multidrug-resistant† (%) | ||

| MRSA | 14.4 (13.3 to 17.2) | Wozniak et al 11 |

| ESBL E. coli | 5.3 (4.5 to 6.5) | |

| VRE | 37.8 (26.7 to 49.2) | |

| ESBL K. pneumoniae | 4.1 (3.6 to 7.7) | |

| CPE | 4.1 (3.9 to 4.3) | Coombs et al 12 |

| CRAB | 3.2 (2.7 to 3.7) | |

| Annual change of species incidence (% points) |

||

| MRSA | 0.3 | |

| ESBL E. coli | 0.9 | |

| VRE | −2.8 | Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care13 |

| ESBL K. pneumoniae | 1.0 | Coombs et al 12 |

| CPE | 0.0 | |

| CRAB | 0.0 | |

| Infection fraction‡ (%) | ||

| MRSA | 20.6 (18.6 to 22.5) | Hospital/clinical data |

| ESBL E. coli | 30.0 (23.9 to 36.1) | |

| VRE | 4.6 (2.9 to 6.3) | |

| ESBL K. pneumoniae | 27.6 (21.1 to 34.0) | |

| CPE | 35.9 (20.8 to 51.0) | |

| CRAB | 15.2 (4.8 to 25.6) | |

| Cluster frequency§ | ||

| MRSA, ESBL E. coli, ESBL K. pneumoniae | 0.02 | |

| VRE | 0.05 | Sequencing data records |

| CPE, CRAB | 0.06 | |

| Decreased cluster size (95% CI) | ||

| MRSA§ | 5.38 (1.37 to 9.38) | |

| ESBL E. coli§ | 10.25 (2.94 to 17.56) | |

| VRE | 8.29 (3.89 to 12.68) | Sequencing data records |

| ESBL K. pneumoniae | 3.25 (1.23 to 5.27) | This is the estimated drop in cluster size with WGS use. |

| CPE | 6.33 (−1.20¶ to 13.87) | |

| CRAB | 4.00 (−1.88¶ to 9.88) |

*The HAI percentage of each organism; the denominator is total HAIs.

†The denominator is the total number of the organism detected.

‡The fraction of infections to infections plus colonisations.

§The probability of a cluster detected from all isolates sequenced for that species.

¶The negative number does not denote an increase in isolates. Two isolates are required to identify the cluster, so this negative value means that no clusters are identified.

**

CPE, carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales; CRAB, carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii; ESBL, extended spectrum beta-lactamases; HAI, healthcare-associated infection; MRO, multidrug-resistant organism; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; VRE, vancomycin-resistant enterococci; WGS, whole-genome sequencing.

Trends in multidrug resistance

Multidrug resistance rates are monitored over time in Australia and differ according to state, type of organism and antimicrobial agents used. For this analysis, annual changes to drug resistance were integrated in the analyses and were 0.3 percentage points for MRSA, 0.009 for ESBL E. coli, −2.8 for VRE (decreasing resistance) and 1.0 for ESBL K. pneumoniae.12 13 No change in resistance rates was used for CPE and CRAB.12

WGS surveillance estimates and detection of clusters

Data from isolates that were sequenced came from a research demonstration project of prospective WGS for isolates of suspected outbreaks, to detect clusters before they became established as larger outbreaks. The routine use of WGS for widespread adoption would also be in this context and not for indiscriminate testing. Two years of sequencing data outcomes on MROs were available from December 2017 to December 2019. MROs were sequenced at a central facility from 27 hospitals across Queensland. Of the 1783 isolates that were sequenced during the period, 90% were from three of the largest Queensland hospitals: RBWH, Queensland Children’s Hospital and Princess Alexandra Hospital. Genetic relatedness was determined by examining the number of core genome single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) that differ between any two isolates (pair-wise core genome SNP distance). Genetically related isolates were subdivided into clusters when the SNP distance between them was under a predefined threshold, adjusted for genome size (5 SNPs/Mb).14 15 Clustering was evident in all six pathogens, and isolates within these clusters demonstrate a high probability that pathogen transmission occurred between patients in the hospital.

Identifying SNP differences, through WGS, to investigate MRO outbreaks has become instrumental in revealing the routes of transmission and guiding the infection control response strategy.16 17 The number of isolates in a cluster required to begin a response differs with each MRO. Based on current clinical practice, a cluster was acted on when two related isolates of an MRO were identified, except for MRSA and ESBL E. coli, where three related isolates were required. The number of clusters ranged from 2 to 18 across the pathogens, with an average number of patients in each cluster ranging from 5 to 13 (table 1).

Effectiveness of WGS surveillance

The effectiveness of WGS was estimated when clusters were identified and the information was provided to the infection control team, an outbreak was confirmed, and appropriate infection control measures mobilised. The effectiveness of WGS was a factor of the number of isolates that comprise a cluster, the number of clusters identified and the expected success of intervening to break the chain of transmission. An implicit assumption in this analysis is that the chain of transmission is broken when the WGS data are acted on immediately. Pathogen transmission is prevented with effective environmental cleaning, patient isolations and contact tracing, which we assume occur in all cases.

The number of patients in whom infection or colonisation could have been prevented was calculated after WGS identified a cluster (two or three patients) and began control measures. The turnaround time for WGS testing was 7 days; this is the time required for WGS to be processed and the results made available to the physicians. For example, if the cluster was identified after two patients were detected, and the cluster size was five, then three patients could potentially avoid infection, providing 7 days had elapsed between patients 2 and 3 in the cluster (table 1, online supplemental figure 1).

bmjopen-2020-041968supp001.pdf (46.7KB, pdf)

Expected deaths

Data on the frequency of deaths in hospital from patients infected with any of the six MROs were obtained from the Australian Group on Antimicrobial Resistance Sepsis Outcomes Programs: 2018 Report12 and ranged from 6.7% for CPE to 36.6% for VRE E. faecium. Sensitivity analyses were performed on the 95% confidence limits of these mortality rates.

Resource use and costs

Patients who were colonised with an MRO accrued hospital costs for health professional personal protective equipment (PPE), microbiology tests, cleaning and extra infection control nursing time associated with contact precautions. Patients who were infected and showed symptoms accrued these same costs, plus costs for antibiotic treatments and bed closures. PPE was valued at $50 per day for each patient isolated.18 The colonisation and infection mean length of stay for each MRO ranged from 9 to 43 days (table 2).19–24 Published estimates for extra length of stay due to infection were used to calculate the additional hospitalisation costs for each MRO (table 2).20 21 23 These were valued at $246 per day.25 Antibiotic treatments were estimated from clinical advice (for infected symptomatic patients only), and their costs sourced from hospital pharmacy records, the Pharmaceutical Benefit Scheme and published studies.11 26 27 Where necessary, costs were inflated to 2019 prices using the Hospital Pricing Index. Sensitivity analyses were performed on the 95% confidence limits of the values and for treatment costs, ±15%.

Table 2.

Variables used in estimating the cost of MRO screening and treatments

| Variable | Estimate (95% CI) | Comment/source |

| Cost of screening for pathogens | ||

| Usual screening: microbiology test and PCR | $82 ($58 to $107) | Elliott et al 5 |

| WGS: microbiology test, PCR and WGS | $437 ($309 to $565) | Elliott et al 5 |

| Cleaning and extra nurse time per detection* | $122 ($90 to $155) | Elliott et al 5 |

| PPE per day in isolation | $50 ($35 to $65) | Otter et al 18 |

| Closed-bed day | $246 ($151 to $342) | Page et al 25† |

| Cost of antibiotic treatment per infected patient | ||

| MRSA (vancomycin)‡ | $580 ($409 to $750) | SA guideline26/hospital pharmacy |

| ESBL Escherichia coli (meropenem)§ | $321 ($227 to $416) | Wozniak28 and hospital pharmacy pricing |

| VRE (linezolid and daptomycin)¶ | $3433 ($2424 to $4443) | |

| CPE (colistin+meropenem** and gentamicin/amikacin††) | $2920 ($2061 to $3778) | Pharmacy infection network27 and hospital pharmacy pricing |

| CRAB (colistin+tigecycline‡‡ and colistin+meropenem**) | $3199 ($2258 to $4139) | Viehman et al 29 and hospital pharmacy pricing |

| MRSA | ||

| Colonisation LOS | 29.2 (16.4 to 51.9) | Kirwin et al 20 |

| Infection LOS | 42.7 (23.6 to 77.2) | Kirwin et al 20 |

| ESBL E. coli | ||

| Colonisation LOS | 16.0 (8.0 to 31.0) | Suzuki et al 23 |

| Infection LOS | 33.0 (18.0 to 64.0) | Suzuki et al 23 |

| VRE | ||

| Colonisation LOS | 15.0 (9.0 to 30.0) | Tan et al 30 |

| Infection LOS | 34.0 (29.6 to 38.4) | Lloyd-Smith et al 21 |

| ESBL Klebsiella pneumoniae | ||

| Colonisation LOS | 16.0 (8.0 to 31.0) | Suzuki et al 23 |

| Infection LOS | 33.0 (18.0 to 64.0) | Suzuki et al 23 |

| CPE | ||

| Colonisation LOS | 12.0 (3.0 to 21.0) | Rodriguez-Acevedo et al 22† |

| Infection LOS | 29.0 (22.7 to 35.3) | Zhen et al 24 |

| CRAB | ||

| Colonisation LOS | 9.0 (6.0 to 22.0) | Álvarez-Marín et al 19 |

| Infection LOS | 21.5 (11.5 to 42.8) | Álvarez-Marín et al 19 |

| Closed-bed days§§ | ||

| MRSA | 35.2 (16.3 to 69.4) | Kirwin et al 20 |

| ESBL E. coli | 16.6 (3.6 to 30.4) | Suzuki et al 23 |

| VRE | 13.8 (10.0 to 16.9) | Lloyd-Smith et al 21 |

| ESBL K. pneumoniae | 16.6 (3.6 to 30.4) | Suzuki et al 23 |

| CPE | 14.5 (11.4 to 17.6) | Assumption¶¶ |

| CRAB | 10.8 (5.8 to 21.4) | Assumption¶¶ |

*Cleaning is for decontamination of the room and nursing time is for isolating the patient, contact precautions and so on.

†Australian study/data.

‡Flucloxacillin administered at 2 g intravenously 6-hourly initially and vancomycin at 2 g.

§Meropenem administered at 1.0–2 g three times daily.

¶Linezolid administered at 2×0.6 g for 14 days and daptomycin 0.6 g daily.

**Colistin administered at 275 mg for 14 days and meropenem administered at 1.0–2 g three times daily.

††Gentamicin administered at 5–7 mg/kg for 14 days and amikacin administered at 15 mg/kg.

‡‡Colistin administered at 275 mg for 14 days and tigecycline administered at 100 mg followed by 50 mg every 12 hours.

§§Closed-bed days were estimated by excess LOS for infections by each species.

¶¶Extra LOS was assumed to be 50% of the infection LOS.

CPE, carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales; CRAB, carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii; ESBL, extended spectrum beta-lactamases; LOS, length of stay; MRO, multidrug-resistant organism; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; PPE, personal protective equipment; SA, South Australia Health; VRE, vancomycin-resistant enterococci; WGS, whole-genome sequencing.

Analyses

Analyses comprised aggregated total of the costs for current practice compared with a WGS surveillance strategy for the six MROs. Analyses were performed in Excel. Multiway sensitivity analyses were undertaken for each variable (eg, organism frequency, MRO rate, cluster frequency, infection fraction and so on), and the high and low values for the six organisms were used simultaneously for each variable. These values were varied within the 95% confidence limits and the results were shown for the overall cost difference between current practice (no WGS) and WGS surveillance (table 1). A sensitivity analysis was performed on a quicker 4-day turnaround time for WGS testing. Outcomes were reported for the number of expected patients with colonisations and infections, the associated hospitalisation costs and the expected deaths.

Patient and public involvement

The research study did not involve patients and the public.

Results

An estimated 8003 patients in Queensland hospitals will be infected with one of six common MROs and 89 535 will be colonised, for a total of 97 539 patients in the first year. MRSA and VRE made up the majority of the six MROs (table 3). The expected number of deaths was 2032 in year 1. Over 5 years, the number of patients infected with these MROs decreased by 15% and the number of colonisations decreased by 27% overall, primarily due to decreasing drug resistance for VRE (table 3).

Table 3.

Estimated number of Queensland patients with MROs and deaths from sepsis

| 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | |

| Number of annual hospitalisations | 1 639 888 | 1 639 888 | 1 639 888 | 1 639 888 | 1 639 888 |

| Number of HAIs | 162 349 | 162 349 | 162 349 | 162 349 | 162 349 |

| Number of HAIs from MROs of interest | 58 141 | 58 141 | 58 141 | 58 141 | 58 141 |

| Number of patients infected with MROs* | |||||

| MRSA | 3223 | 3290 | 3357 | 3424 | 3491 |

| ESBL Escherichia coli | 752 | 881 | 1009 | 1138 | 1267 |

| VRE | 3551 | 3288 | 3025 | 2762 | 2499 |

| ESBL Klebsiellapneumoniae | 292 | 364 | 435 | 507 | 578 |

| CPE | 128 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 128 |

| CRAB | 57 | 57 | 57 | 57 | 57 |

| Total MROs of concern | 8003 | 8008 | 8012 | 8017 | 8021 |

| Total number of patients colonised with MROs | 89 536 | 84 801 | 80 067 | 75 332 | 70 598 |

| Total number of patients expected with infections/colonisations | 97 539 | 92 809 | 88 079 | 83 349 | 78 619 |

| Deaths from sepsis | 2032 | 1982 | 1932 | 1881 | 1831 |

*Adjusted for change in drug resistance rate.

CPE, carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales; CRAB, carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii; ESBL, extended spectrum beta-lactamases; HAI, healthcare-associated infection; MRO, multidrug-resistant organism; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; VRE, vancomycin-resistant enterococci.

This compares with a strategy of routine WGS surveillance, with a turnaround time of 7 days, where WGS use could avoid 2085 infected patients and 34 641 colonised patients (table 4). In total, WGS would avoid 36 726 patients infected/colonised in year 1, decreasing to 26 984 avoided patient infections/colonisations by year 5. The number of patient deaths avoided was estimated at 650 in year 1 to 502 by year 5.

Table 4.

Estimated differences in costs ($A) and patient deaths from current practice versus WGS surveillance

| 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | |

| Current practice | |||||

| Total number of patients expected to have MRO infections/colonisation | 97 539 | 92 809 | 88 079 | 83 349 | 78 619 |

| Cost of microbiology screening | $8 028 283 | $7 638 967 | $7 249 651 | $6 860 335 | $6 471 019 |

| Cost of cleaning and nursing time | $11 911 230 | $11 333 618 | $10 756 006 | $10 178 394 | $9 600 782 |

| Cost of extra length of stay | $44 793 430 | $45 297 162 | $45 800 893 | $46 304 625 | $46 808 356 |

| Cost of PPE | $91 162 386 | $87 836 074 | $84 509 762 | $81 183 450 | $77 857 139 |

| Cost of antibiotic treatment of patients | $14 952 034 | $14 152 425 | $13 352 816 | $12 553 207 | $11 753 598 |

| Total cost: current practice | $170 847 364 | $166 258 246 | $161 669 129 | $157 080 012 | $152 490 895 |

| Expected number of patient deaths | 2032 | 1982 | 1932 | 1881 | 1831 |

| WGS surveillance | |||||

| Total number of potentially avoided infections with WGS (patients) | 2085 | 2003 | 1921 | 1839 | 1757 |

| Total number of potentially avoided colonisations with WGS (patients) | 34 641 | 32 287 | 29 934 | 27 580 | 25 227 |

| Total number of potentially avoided infected/colonised with WGS | 36 726 | 34 290 | 31 855 | 29 419 | 26 984 |

| Cost of WGS | $26 575 746 | $25 573 072 | $24 570 397 | $23 567 723 | $22 565 049 |

| Cost of cleaning and nursing time | $7 426 340 | $7 146 152 | $6 865 964 | $6 585 777 | $6 305 589 |

| Cost of extra length of stay | $36 149 780 | $36 881 764 | $37 613 748 | $38 345 732 | $39 077 716 |

| Cost of PPE | $60 703 607 | $59 267 592 | $57 831 577 | $56 395 563 | $54 959 548 |

| Cost of treating infected patients | $9 123 437 | $8 713 828 | $8 304 219 | $7 894 610 | $7 485 001 |

| Total cost: WGS surveillance | $139 978 910 | $137 582 408 | $135 185 906 | $132 789 404 | $130 392 902 |

| Expected number of patient deaths | 1382 | 1369 | 1356 | 1342 | 1329 |

| Cost savings with WGS surveillance | $30 868 454 | $28 675 839 | $26 483 223 | $24 290 608 | $22 097 992 |

| Patient deaths avoided | 650 | 613 | 576 | 539 | 502 |

| Costs saved per avoided infection | −$14 805 | −$14 317 | −$13 787 | −$13 210 | −$12 579 |

| Costs saved per avoided colonisation | −$891 | −$888 | −$885 | −$881 | −$876 |

MRO, multidrug-resistant organism; PPE, personal protective equipment; WGS, whole-genome sequencing.

The total cost for the current management of these colonised and infected patients was an estimated $170.8 million in year 1, comprising $8.0 million for conventional microbiology screening, $11.9 million for cleaning and nursing time, $44.8 million for closed-bed days, $91.1 million for the cost of PPE and $15.0 million for antibiotic treatments (table 4).

Compared with a strategy of routine WGS surveillance, the sequencing and microbiology cost would be $26.8 million ($18.5 million more than the standard of care), but is offset in the same year by fewer costs for cleaning and nursing, length of stay, PPE and antibiotic treatments (table 4). The total cost savings were $30.9 million in year 1, dropping to $22.1 million by year 5. The cost saved for each avoided patient infection was $6917 and for each colonisation $475 in year 1.

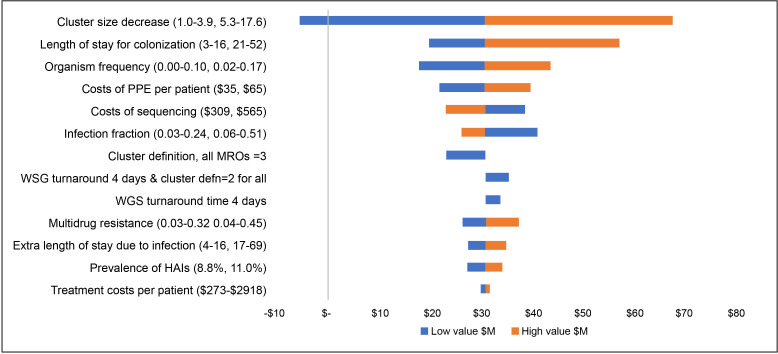

The sensitivity analyses showed that when plausible alternative values were used in the analyses, hospital cost savings were always retained, with one exception (figure 1). The findings were most sensitive to the variation in estimates of preventable patient infections if WGS is undertaken, and if this was the lowest value across all six MROs (simultaneously) it would cost an additional $5.0 million for the WGS strategy. The length of stay for colonisations and organism frequency also changed the base findings by ±$10.0 million, but overall cost savings remained. When higher and lower values were used for expected rates of deaths from the six MROs (simultaneously), the deaths potentially avoided ranged from 411 to 893 in year 1 to 316 to 694 in year 5.

Figure 1.

Tornado diagram of change in the main analysis cost savings of $A30.9 million, with higher and lower input values. HAIs, healthcare-associated infections; MROs, multidrug-resistant organisms; PPE, personal protective equipment; WGS, whole-genome sequencing.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge on the incidence of HAIs, MROs and drug resistance rates, nearly 100 000 patients will be infected or colonised with potentially serious bacterial infections in Queensland hospitals each year. This will cost the government $171 million per year to manage. By routinely using WGS to assist infection control teams in managing patients early in bacterial transmission, the expected cost savings will be $30.9 million per year. Not only will hospital costs be saved but thousands of patients will avoid suffering from infections and the associated risk of death.

Based on the information from WGS, we identified clusters to observe detection patterns of the six MROs among hospital patients. This differs from observing actual transmission among patients because WGS screening was not undertaken on every patient. Retrospectively, we found WGS was performed on between 13% and 93% of the MROs, with 13% for each of S. aureus and E. coli, the most common pathogens. The cost savings are heavily influenced by the cluster sizes and potential to avoid infections/colonisations, breaking the chain of transmission. A quicker testing turnaround is desirable for infection control processes. When we tested the turnaround time from 7 days to 4 days, we saw only two of the six MROs with notable reductions in patients infected, meaning detections in most patients screened were greater than a few days between the first two or three patients.

These findings align with other economic studies looking at the benefits of a WGS surveillance-based infection control programme. Kumar et al’s6 findings from a single-institute US study found WGS surveillance to be less costly and more effective than standard of care. Their results were most sensitive to WGS cost and number of isolates sequenced each year. In the UK, Dymond et al 4 undertook an economic analysis that modelled MRSA genomic surveillance, compared with current practice, and found cost savings for genomic surveillance of ~£730 000 annually to the National Health Service. In Australia, our previous work on an ESBL E. coli outbreak in a single hospital also predicted significant cost savings and patient outcomes if WGS was implemented early as standard of care and avoided delays in response.5 The major criticisms of the previous work in this area are the focus on single organisms or single institutions which can limit the generalisability of the findings and the studies are retrospective. Our cost analysis somewhat overcomes these issues by analysing data from Queensland hospitals for state-wide application, including six common MROs in our setting, and we estimated future trends based on expected changes in multidrug resistance rates.

The cluster information from WGS was not available in real time but part of a demonstration project of prospective WGS in response to suspected outbreaks, to detect clusters before they became established as larger outbreaks. The cluster analysis here was performed retrospectively within a research context. Our cost analysis shows the potential for proactive WGS surveillance to support infection control teams under the premise that testing infrastructure, staffing and fast turnaround times are in place on a wider scale. With the extensive COVID-19 pandemic preparations for widespread testing and additional sequencers now in place for Queensland, this would appear possible for more routine whole-genome pathogen sequencing. An additional benefit of genomic information is the contribution towards phylogenetic libraries and reporting to share knowledge and information with other jurisdictions and the scientific community.

This study should be viewed with some caution as it depends on the accuracy of the estimates used. For example, it is feasible that the estimates of deaths avoided with WGS may be conflated by the MRO not being the main cause of death if the patient’s underlying clinical condition is severe and advanced. Other than the best available evidence for the estimates used in the analysis, the appropriate way to address this is through sensitivity analyses. To deal with the possible uncertainty in the estimates, 95% confidence limits were tested in sensitivity analyses. These found the cost savings were stable despite variation in all but one scenario (ie, low cluster sizes). Estimating the mean length of stay for infections or colonisations is difficult to measure and varies significantly depending on MRO type. Colonisation length of stay directly influences infection control nursing time and PPE costs and is shown to be a major driver of these findings, with high patient numbers. Further research is necessary to avoid measurement bias of length of stay estimates for HAIs.22 A further issue is the assumption that WGS equipment and infrastructure were available at the outset as these costs are not included in an operational budget impact, but rather a capital investment. Economies of scale with wider testing and lower testing are seen in the sensitivity analyses covering a lower unit cost for WGS; however, further streamlining of workflows could see testing in the future as low as $A150 per isolate. Overall, we suggest the findings are conservative because WGS testing was only used infrequently as a total percentage of MRO isolates, and if screening were higher more infections and therefore higher cluster sizes would be apparent (at reasonable cost). The expected consequences of a WGS strategy are also likely to be conservative and other MROs were excluded in the analysis. Furthermore, it is possible that an organism can contribute to more than one type of HAI and therefore the impact of prevention may also be greater.

Implementation of WGS into routine infection control practice would require standardised algorithms leading to early alarms and detection of problems and intervention for all hospitals. Although many hospitals do have systems and decision rules currently in place, a key issue is whether infection control teams would immediately and effectively respond on receiving these advanced data. This is uncertain, as is any significant organisational change, and would require infection control teams to undergo training and time to transition to new protocols. Our analysis assumes full adherence to a new scenario as presented here, as if it were established, and it is recognised this is the result of effective change and uptake by hospitals. Nevertheless, predictions about resource use and costs that might result from routine WGS are useful for decision-makers to understand whether it is warranted on an economic basis to proceed further with new resource allocations.

Conclusion

The proactive use of WGS surveillance for infection control of common MROs was estimated to be cost-saving for hospitals and beneficial for patients. This study has implications for government resource allocation decisions and establishes a favourable value proposition for adopting pathogen WGS into routine clinical practice in Queensland.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully thank Minyon Avent at Queensland Health, who assisted in extracting the hospital pharmacy pricing data for this project.

Footnotes

Twitter: @louisagord, @1healthau, @PLR_aus

Contributors: LGG and TME conceived the study aim and purpose. TME undertook the main analyses with assistance from LGG. BF, PLR, DLP and BM provided data for this study, critically reviewed the study, contributed to drafting the paper and provided subject matter expertise. PNAH, DLP and BF provided clinical and scientific expertise. All authors contributed to drafting the manuscript and reviewed the final version.

Funding: This research received funding from Queensland Government, Queensland Health and Queensland Genomics.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute Human Research Ethics Committee (P2353) and the Queensland Government Public Health Act Human Research Ethics Committee (RD007427).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request to the authors and can be readily and securely emailed to interested readers.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

References

- 1. Mitchell BG, Shaban RZ, MacBeth D, et al. . The burden of healthcare-associated infection in Australian hospitals: a systematic review of the literature. Infect Dis Health 2017;22:117–28. 10.1016/j.idh.2017.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) General record of incidence of mortality (GRIM) data, Cat. No: PHE 229. Canberra: AIHW, 2019. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/life-expectancy-deaths/grim-books [Google Scholar]

- 3. LM L, Grassly NC, Fraser C. Genomic analysis of emerging pathogens: methods, application and future trends. Genome biology 2014;15:541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dymond A, Davies H, Mealing S, et al. . Genomic surveillance of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: a mathematical early modeling study of cost-effectiveness. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2020;70:1613–9. 10.1093/cid/ciz480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Elliott TM, Lee XJ, Foeglein A, et al. . A hybrid simulation model approach to examine bacterial genome sequencing during a hospital outbreak. BMC Infect Dis 2020;20:72 10.1186/s12879-019-4743-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kumar P, Sundermann AJ, Martin EM, et al. . Method for economic evaluation of bacterial whole genome sequencing surveillance compared to standard of care in detecting hospital outbreaks. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2020;9 10.1093/cid/ciaa512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gordon LG, White NM, Elliott TM, et al. . Estimating the costs of genomic sequencing in cancer control. BMC Health Serv Res 2020;20 10.1186/s12913-020-05318-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sullivan SD, Mauskopf JA, Augustovski F, et al. . Budget impact analysis—principles of good practice: report of the ISPOR 2012 budget impact analysis good practice II Task force. Value in Health 2014;17:5–14. 10.1016/j.jval.2013.08.2291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Health Q Quarterly Hospital activity information for October, November, December 2019: Queensland government, 2020. Available: http://www.performance.health.qld.gov.au/Hospital/HospitalActivity/99999

- 10. Russo PL, Stewardson AJ, Cheng AC, et al. . The prevalence of healthcare associated infections among adult inpatients at nineteen large Australian acute-care public hospitals: a point prevalence survey. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2019;8 10.1186/s13756-019-0570-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wozniak TM, Bailey EJ, Graves N. Health and economic burden of antimicrobial-resistant infections in Australian hospitals: a population-based model. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2019;40:320–7. 10.1017/ice.2019.2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Coombs GBJ, Daley D, Collignon P. Australian group on antimicrobial resistance sepsis outcomes programs: 2018 report. Sydney: Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Care ACoSaQiH Australian passive antimicrobial resistance surveillance. first report: multi-resistant organisms. Sydney: ACSQHC, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Octavia S, Wang Q, Tanaka MM, et al. . Delineating community outbreaks of Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium by use of whole-genome sequencing: insights into genomic variability within an outbreak. J Clin Microbiol 2015;53:1063–71. 10.1128/JCM.03235-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stinear TP, Holt KE, Chua K, et al. . Adaptive change inferred from genomic population analysis of the ST93 epidemic clone of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Genome Biol Evol 2014;6:366–78. 10.1093/gbe/evu022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chapman P, Forde BM, Roberts LW, et al. . Genomic Investigation Reveals Contaminated Detergent as the Source of an Extended-Spectrum-β-Lactamase-Producing Klebsiella michiganensis Outbreak in a Neonatal Unit. J Clin Microbiol 2020;58 10.1128/JCM.01980-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Roberts LW, Harris PNA, Forde BM, et al. . Integrating multiple genomic technologies to investigate an outbreak of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacter hormaechei. Nat Commun 2020;11:466 10.1038/s41467-019-14139-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Otter JA, Burgess P, Davies F, et al. . Counting the cost of an outbreak of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae : an economic evaluation from a hospital perspective. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2017;23:188–96. 10.1016/j.cmi.2016.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Álvarez-Marín R, López-Rojas R, Márquez JA, et al. . Colistin dosage without loading dose is efficacious when treating carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii ventilator-associated pneumonia caused by strains with high susceptibility to colistin. PLoS One 2016;11:e0168468 10.1371/journal.pone.0168468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kirwin E, Varughese M, Waldner D, et al. . Comparing methods to estimate incremental inpatient costs and length of stay due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Alberta, Canada. BMC Health Serv Res 2019;19 10.1186/s12913-019-4578-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lloyd-Smith P, Younger J, Lloyd-Smith E, et al. . Economic analysis of vancomycin-resistant enterococci at a Canadian Hospital: assessing attributable cost and length of stay. J Hosp Infect 2013;85:54–9. 10.1016/j.jhin.2013.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rodriguez-Acevedo AJ, Lee XJ, Elliott TM, et al. . Hospitalization costs for patients colonized with carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales during an Australian outbreak. J Hosp Infect 2020;105:146–53. 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Suzuki H, Perencevich EN, Nair R, et al. . Excess length of acute inpatient stay attributable to acquisition of hospital-onset gram-negative bloodstream infection with and without antibiotic resistance: a multistate model analysis. Antibiotics 2020;9:96 10.3390/antibiotics9020096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhen X, Lundborg CS, Sun X, et al. . The clinical and economic impact of antibiotic resistance in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Antibiotics 2019;8:115. 10.3390/antibiotics8030115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Page K, Barnett AG, Graves N. What is a hospital bed day worth? A contingent valuation study of hospital chief executive officers. BMC Health Serv Res 2017;17:137–37. 10.1186/s12913-017-2079-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Health SA Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia (SAB) management clinical guideline. Government of South Australia 2019.

- 27. Network PI Guidance on treatment of CARBAPENAMASE producing Enterobacteriaceae UK clinical pharmacy association, 2016. Available: https://www.nhstaysideadtc.scot.nhs.uk/Antibiotic%20site/pdf%20docs/UKCPA%20CPE%20Guidance.pdf

- 28. Wozniak TM Clinical management of drug-resistant bacteria in Australian hospitals: an online survey of doctors' opinions. Infect Dis Health 2018;23:41–8. 10.1016/j.idh.2017.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Viehman JA, Nguyen MH, Doi Y. Treatment options for carbapenem-resistant and extensively drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infections. Drugs 2014;74:1315–33. 10.1007/s40265-014-0267-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tan D, Htun HL, Koh J, et al. . Comparative epidemiology of vancomycin-resistant enterococci colonization in an acute-care hospital and its affiliated intermediate- and long-term care facilities in Singapore. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2018;62:e01507–18. 10.1128/AAC.01507-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-041968supp001.pdf (46.7KB, pdf)