Abstrict

LINC00941 is a novel lncRNA that has been found to exhibit protumorigenic and prometastatic behaviors during tumorigenesis. However, its role in metastatic CRC remains unknown. We aimed to investigate the functions and mechanisms of LINC00941 in CRC metastasis. LINC00941 was shown to be upregulated in CRC, and upregulated LINC00941 was associated with poor prognosis. Functionally, LINC00941 promoted migratory and invasive capacities and accelerated lung metastasis in nude mice. Mechanistically, LINC00941 activated EMT in CRC cells, as indicated by the increased expression of key molecular markers of cell invasion and metastasis (Vimentin, Fibronectin, and Twist1) and simultaneous decreased expression of the main invasion suppressors E-cadherin and ZO-1. LINC00941 was found to activate EMT by directly binding the SMAD4 protein MH2 domain and competing with β-TrCP to prevent SMAD4 protein degradation, thus activating the TGF-β/SMAD2/3 signaling pathway. Our data reveal the essential role of LINC00941 in metastatic CRC via activation of the TGF-β/SMAD2/3 axis, which provides new insight into the mechanism of metastatic CRC and a novel potential therapeutic target for advanced CRC.

Subject terms: Metastasis, Epigenetics

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC), a multistep disease in which genetic and epigenetic alterations accumulate, is frequently fatal and one of the most common malignancies [1–3]. Metastasis plays a leading role in cancer-related death, yet the biological and mechanistic details underlying this complex process remain the least understood part of CRC development. Cancer cell epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a compelling feature that enhances cancer cell dissemination and drives the metastatic cascade, is frequently activated and contributes to heterogeneous tumor cell phenotypes that cross lineage boundaries in CRC development [4–7]. However, the in-depth molecular mechanisms behind EMT in metastatic CRC remain largely unclear.

Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) are a class of highly multifunctional noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) larger than 200 nucleotides in size that lack coding potential [8]. Accumulating experimental evidence has highlighted that the dysregulation of lncRNAs plays a causative role in the initiation and propagation of tumorigenesis through epigenetic modifications at both the transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels [9, 10]. It is well recognized that several lncRNAs, HAGLR, HCP5, RP11, ELIT-1, and CASC11, are crucial for EMT [11–16]. However, the role of lncRNA-mediated EMT in metastatic CRC remains largely unclear.

Using the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) network, we identified differentially expressed CRC-related lncRNAs, including the metastasis-regulated and survival-related lncRNA long intergenic non-protein coding RNA 941 (LINC00941). LINC00941, also known as MSC-upregulated factor (lncRNA-MUF), is a novel lncRNA found to exhibit protumorigenic and prometastatic behaviors during tumorigenesis. The upregulation of LINC00941 activated Wnt/β-catenin signaling and EMT in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [17]. The elevated expression of LINC00941 was associated with phosphorylation of the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway in lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) [18]. Overexpression of LINC00941 showed the ability to promote tumors in gastric cancer (GC) development via regulating cancer-related biological processes and EMT [19, 20]. However, the functional significance of LINC00941 in tumorigenesis, especially that in CRC, is far from clear.

Here, we explored expression changes and the biological functions of LINC00941 in CRC and their clinical implications. In particular, we demonstrated the mechanistic role of LINC00941 in EMT activation, and our results showed that LINC00941 promotes the metastasis of CRC via activating the TGF-β/SMAD2/3 signaling pathway through preventing SMAD4 protein degradation.

Materials and methods

Identification of metastasis- and survival-related lncRNAs

Gene expression data and clinical information from CRC patients were obtained from TCGA. CRC patients with a follow-up time exceeding 2000 days were excluded. The details of the data processing procedure were as previously described [20].

Human CRC tissues and cell lines

Surgically excised CRC tissues and surrounding nontumor tissues were obtained from Xijing Hospital, the Air Force Military Medical University. Patients enrolled in this study gave their informed consent, and the study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Air Force Military Medical University and Xijing Hospital. CRC tissue microarrays containing 90 cases of colorectal adenocarcinoma with paired paraneoplastic tissues and follow-up data were purchased from Outdo Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Five CRC cell lines (HT-29, HCT-116, SW480, SW620, and LoVo cells) and immortalized human normal colon epithelial cells (FHC cells) were used in this study. FHC cells were purchased from the Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China), and all CRC cell lines were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Virginia, USA). All cell lines were cultured in DMEM (Gibco, USA) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, USA) after being authenticated and tested for mycoplasma contamination.

Protein preparation and western blot assay

Western blot assays were performed as described previously [21]. In brief, total proteins were extracted from CRC cells by using RIPA buffer supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Merck, Germany), and protein aliquots were separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized using UltraSignal ECL Reagent (4 A Biotech Co., Ltd, China). The primary antibodies used were listed in Table S1.

Immunoprecipitation (IP), co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP), and mass spectrum (MS) analysis

IP and Co-IP were performed by using a Pierce® Co-Immunoprecipitation Kit (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, USA) according to the methods in a previously report [22]. Briefly, cells were lysed and centrifuged, and the supernatant was removed. Then, the precleared lysate was incubated with a mixture of 50 μl of Protein G beads and 5 μg of conjugated primary antibody overnight at 4 °C. IgG antibody (5 μg) was used as a control. Finally, samples were loaded onto an SDS-PAGE gel for Western blot analysis. For the Co-IP assay, the IP lysate was examined by Western blotting with another primary antibody against the protein of interest. MS analysis was performed as previously described [22]. Briefly, the candidate bands were excised from the gel after Coomassie blue staining and subjected to in-gel digestion and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight/time-of-flight mass spectrometry.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and in situ hybridization (ISH)

IHC and ISH were performed with a CRC tissue microarray. For IHC, the tissue microarray was incubated with primary antibody (Table S1), followed by incubation with HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody. Then, the samples were visualized in situ with diaminobenzidine chromogenic substrate. ISH was performed using a 5′- and 3′-digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled locked nucleic acid-based probe specific for LINC00941 with detection using anti-DIG antibody (QIAGEN).

RNA pulldown assays

RNA pulldown assays were performed according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Briefly, biotin-labeled RNA was transcribed with Biotin RNA Labeling Mix and T7 RNA polymerase, and purified. Purified biotin-labeled RNA was then heated and annealed to form secondary structure, mixed with cytoplasmic extract in RIP buffer for 1 h, and incubated with streptavidin agarose beads for 1 h. Finally, the beads were extracted with TRIzol reagent for quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis.

RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP)

RIP was carried out with a Magna RIP™ RNA-Binding Protein Immunoprecipitation Kit (Millipore) with reference to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, cells transfected with the indicated plasmid were harvested and then lysed in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH = 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton-100, 0.1% SDS, 1.5 mM EDTA). Thereafter, cell lysates were incubated with RIP buffer containing magnetic beads. The beads were conjugated with the indicated antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) or anti-IgG (Abcam) as a negative control. Then, the samples were digested by applying DNase I and proteinase K, and the immunoprecipitated RNA was isolated. Eventually, the enrichment of the purified RNAs was detected by RT-qPCR.

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated from CRC cell lines and tissues using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, CA, USA). Reverse transcription (RT) of complementary DNA (cDNA) was carried out by using a PrimeScript Reverse Transcriptase Reagent Kit (TakaRa, Tokyo, Japan). cDNA aliquots were amplified by using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (TaKaRa, Tokyo, Japan). β-Actin served as an endogenous control. The sequences of the sense and antisense primers used were listed in Table S2.

Lentiviral packaging and infection

The lentivirus packaging was carried out following a previously established protocol [23]. Packaging plasmid pMD2.G (GeneChem Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), envelope plasmid pVSVG and pLKO.1-Puro or pLVX-Puro plasmid were mixed in serum-free DMEM at a ratio of 2:1:1 (w/w/w). Transfection to HEK293T was performed with polyethylenimine (PEI) at a PEI:plasmid supplemented with 10% FBS and pen/strep antibiotics was collected at 48 h post-transfection. The infected LoVo and HCT-116 cells were cultured in selection medium (culture medium with 1.5 μg/ml of puromycin) and collected for the downstream analysis at 72 h post-infection.

TGF-β1 or disitertide treatment

TGF-β1 (MedChemExpress, USA) was dissolved in PBS to a concentration of 100 ng/ml and diluted in DMEM to a final concentration of 0.2 ng/ml. Disitertide (MedChemExpress, USA) was dissolved in DMSO to a concentration of 1 mM and diluted in DMEM medium to a final concentration of 10 μmol/L. Before TGF-β1 or Disitertide treatment, the cells were incubated with DMEM medium containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin to achieve 80% cell fusion. Next, the cells were treated with TGF-β1 (0.2 ng/ml) or Disitertide (10 μmol/L) for 12 h.

Dual-luciferase reporter assay

Plasmids containing the wild-type LINC00941-promoter sequence was generated by GeneCopoeia (Shanghai, China). Cells (6 × 104/well) were cotransfected with luciferase reporters and the given plasmids. Cells were harvested and lysed for the luciferase assay after 48 h of incubation by using a Dual Luciferase Assay Kit (GeneCopoeia, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and relative luciferase reporter activities were calculated [24, 25].

In vitro functional studies

In vitro functional assessments of CRC cell invasion and migration were carried out by Transwell assay as previously described [26]. The cell migration assay was performed by using Boyden chambers. Cells (~5 × 104) were suspended in DMEM (200 μl, containing 1% FBS) and seeded into the upper chamber. For the cell invasion assay, cells (~1 × 105) were suspended in DMEM (200 μl, containing 1% FBS) and seeded into the upper chamber, which had been coated with 60 μl of Matrigel (200 mg/ml). Then, a chamber insert was placed into each well of a 24-well dish supplemented with DMEM (600 μl, containing 20% FBS). Cells were incubated for 24 h before fixation and staining with 0.5% crystal violet. Finally, cells on the upper sides of the membranes were removed, and the cells remaining on the undersides of the membranes were observed with a microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) using five randomized fields.

In vivo metastatic assay

In vivo metastatic assays were conducted by using BALB/C nude mice (male, 6 weeks old). Mice were housed in a pathogen-free animal facility under normal conditions. All animal experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Care Committee of the Air Force Military Medical University. A total of 3 × 106 cells were injected into mice through the tail vein, and the mice were sacrificed 10 weeks after injection. Then, the lungs were removed, and histological examinations were performed by hematoxylin and eosin staining.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by using the SPSS version 20.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and Prism version 5.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA) statistical software packages. Statistical analysis of the experimental data was carried out with the two-tailed Student’s t test, and data are presented as means ± standard deviations unless specifically otherwise indicated. Differences in which P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

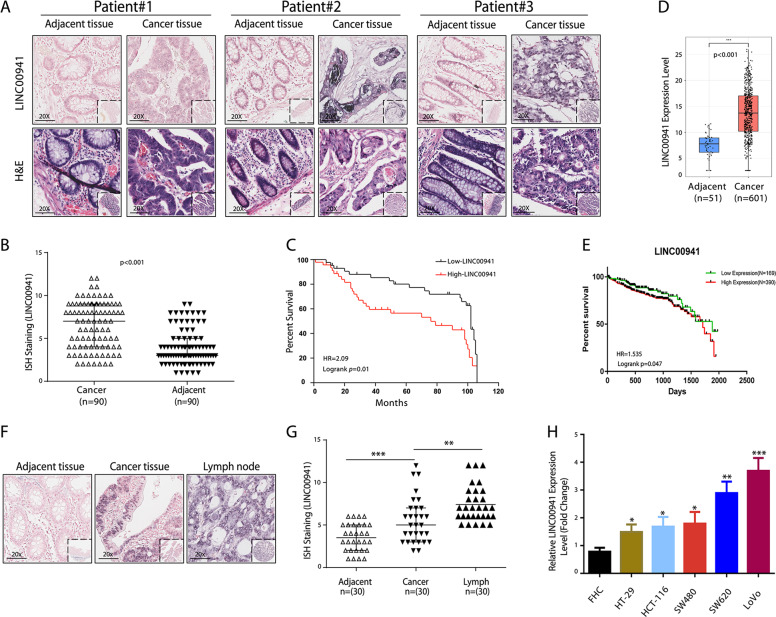

Upregulated LINC00941 expression was associated with poor prognosis in CRC

Amplified expression of LINC00941 in CRC tissues was confirmed with tissue microarray by ISH staining, LINC00941 was mainly localized in the cytoplasm (Fig. 1a) and was upregulated in CRC tissues compared with their adjacent nontumor tissues (Fig. 1b). Meanwhile, the overexpression of LINC00941 was positively associated with lymph node metastasis and the advanced American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) status (Table 1). In addition, Kaplan–Meier survival and Cox proportional hazards analysis showed that CRC patients with higher LINC00941 expression levels had significantly shorter overall survival (OS) times than those with lower LINC00941 expression levels, indicating that the higher LINC00941 level was an independent risk factor for a poor prognosis in CRC patients (Fig. 1c, Tables 2 and 3). Using TCGA network, we identified that LINC00941, which is both a metastasis- and survival-associated lncRNA, was upregulated in CRC tissues compared with their adjacent nontumor tissues (Fig. 1d) and associated with the OS times of CRC patients (Fig. 1e). Then, we selected 30 cases of CRC patients with lymph node metastases and detected the expression of LINC00941 in the adjacent tissues, tumor tissues, and lymph node metastases, respectively. The data further confirmed that the expression of LINC00941 significantly higher in tumor tissues and highest in lymph node metastases (Fig. 1f, g). We also compared LINC00941 expression in CRC cell lines (HT-29, HCT-116, SW480, SW620, and LoVo cells) and immortalized normal colon epithelial cells (FHC cells) and found that LINC00941 was highly expressed in all investigated CRC cell lines and especially overexpressed in highly invasive CRC cell lines (SW620 and LoVo) compared with FHC cells, suggesting that LINC00941 plays an oncogenic role in CRC development (Fig. 1h).

Fig. 1. LINC00941 expression is significantly upregulated during CRC development.

a Representative images of ISH staining of LINC00941 in CRC tissues and paired nontumor tissues of three CRC patients (n = 90). b The level of LINC00941 expression was calculated from CRC tissue arrays analyzed by ISH. c Kaplan–Meier curve depicting the overall survival of 90 CRC patients. d LINC00941 level in 601 CRC tumor samples and 51 normal controls from TCGA data. e Kaplan–Meier curve depicting the overall survival of 559 CRC patients from TCGA database. f and g Representative images of ISH staining of LINC00941 in adjacent normal tissues, tumor tissues, and positive metastatic lymph from CRC tissue arrays analyzed by ISH (n = 30). h The expression of LINC00941 in HCC cell lines was upregulated compared with that in the FHC immortalized human colorectal cell line, as shown by RT-qPCR. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Table 1.

LINC00941 levels and clinicopathological features in 90 CRC patients.

| Characteristics | Total | LINC00941 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | |||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 57 | 26 | 31 | 0.589 |

| Female | 33 | 17 | 16 | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| >60 | 53 | 25 | 28 | 0.890 |

| ≤60 | 37 | 18 | 19 | |

| Location | ||||

| Ascendens | 28 | 16 | 12 | 0.653 |

| Transversum | 15 | 7 | 8 | |

| Descendens | 13 | 5 | 8 | |

| Sigmoideum/rectum | 34 | 15 | 19 | |

| Tumor size(cm) | ||||

| ≤5 | 20 | 12 | 8 | 0.215 |

| >5 | 70 | 31 | 39 | |

| Lymph node metastasis | ||||

| Negative | 53 | 30 | 23 | 0.045 |

| Positive | 37 | 13 | 24 | |

| AJCC stage | ||||

| I\II | 50 | 29 | 21 | 0.030 |

| III\IV | 40 | 14 | 26 | |

Table 2.

Prognostic factors in colon cancer patients by univariate analysis.

| Parameter | n | Cumulative survival rates (%) 3-years 5-years | Mean survival time (mo) | Hazard ratio | 95% Confidence interval | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 57 | 71.6 | 62.8 | 70.8 | 0.70 | 0.38–1.28 | 0.24 |

| Female | 33 | 77.0 | 77.0 | 82.1 | |||

| Age | |||||||

| >60 | 53 | 63.4 | 61.0 | 69.2 | 0.84 | 0.49–1.46 | 0.54 |

| ≤60 | 37 | 86.2 | 77.9 | 82.9 | |||

| Location | |||||||

| Ascendens | 28 | 81.1 | 72.7 | 79.9 | 1.06 | 0.85–1.32 | 0.60 |

| Transversum | 15 | 73.3 | 73.3 | 78.9 | |||

| Descendens | 13 | 46.2 | 36.9 | 52.0 | |||

| Sigmoideum/rectum | 34 | 79.6 | 75.4 | 79.3 | |||

| Tumor size | |||||||

| ≤5 cm | 20 | 95.0 | 90.0 | 94.3 | 1.72 | 0.90–3.29 | 0.10 |

| >5 cm | 70 | 66.6 | 60.9 | 68.7 | |||

| Lymph node metastasis | |||||||

| Negative | 53 | 76.4 | 73.7 | 79.9 | 1.97 | 1.13–3.43 | 0.02 |

| Positive | 37 | 70.0 | 61.6 | 69.8 | |||

| AJCC stage | |||||||

| I/II | 50 | 77.0 | 74.0 | 80.2 | 1.80 | 1.03–3.17 | 0.04 |

| III/IV | 40 | 69.8 | 62.0 | 70.2 | |||

| LINC00941 level | |||||||

| Low | 43 | 88.0 | 77.4 | 85.48 | 2.09 | 1.19–3.67 | 0.01 |

| High | 47 | 62.1 | 56.5 | 64.69 | |||

| Overall | |||||||

| 90 | 73.5 | 66.5 | 75.0 | ||||

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis using the Cox proportional hazards model.

| Parameter | n | Hazard ratio | 95% Confidence interval | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 57 | 0.70 | 0.37–1.30 | 0.256 |

| Female | 33 | |||

| Age | ||||

| >60 | 53 | 1.11 | 0.53–2.32 | 0.784 |

| ≤60 | 37 | |||

| Tumor size | ||||

| ≤5 cm | 20 | 1.69 | 0.71–4.02 | 0.235 |

| >5 cm | 70 | |||

| Lymph node metastasis | ||||

| Negative | 53 | 1.74 | 0.98–3.10 | 0.059 |

| Positive | 37 | |||

| LINC00941 level | ||||

| Low | 43 | 1.94 | 1.10–3.44 | 0.023 |

| High | 47 | |||

LINC00941 promoted migratory and invasive capacities and activated EMT in CRC cells

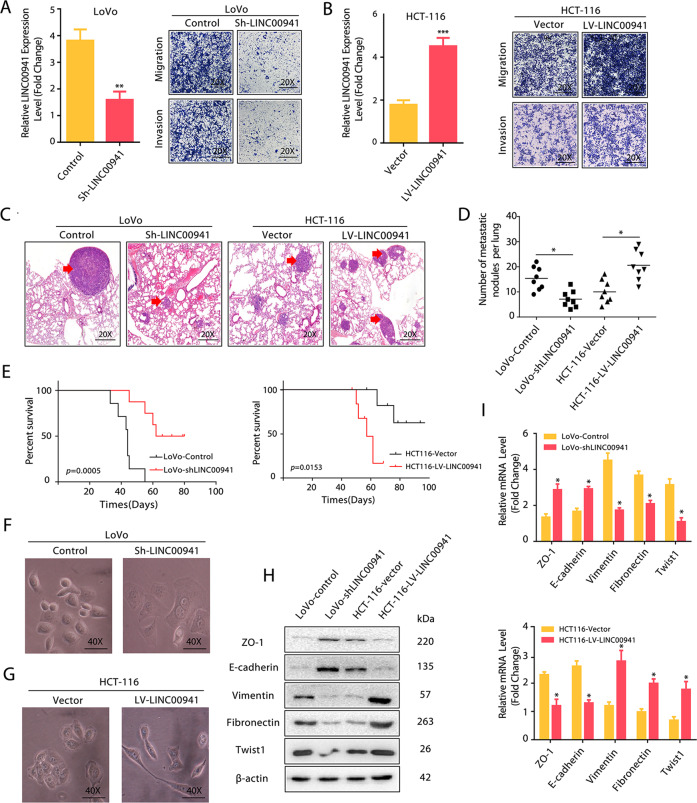

To address the biological significance of LINC00941 in CRC, we overexpressed or silenced LINC00941 in HCT-116 and LoVo cells with lentiviral vectors carrying LINC00941 cDNA or LINC00941-specific small hairpin RNA (sh-LINC00941), respectively. The overexpression of LINC00941 in HCT-116 cells significantly increased cell invasion and migratory capacity compared with those in controls, while the downregulation of LINC00941 in LoVo cells had the reverse effect on cell invasive and migratory abilities (Fig. 2a, b). Consistently, nude mice treated with sh-LINC00941-transfected LoVo cells (LoVo-Sh- LINC00941) generated fewer lung metastatic nodules, while nude mice treated with LINC00941-overexpressing HCT-116 cells (HCT-116-LINC00941) generated more lung metastatic nodules than their corresponding controls (Fig. 2c, d). In addition, nude mice that received HCT-116-LINC00941 cells had the shorter OS compared with the control groups and that received LoVo-Sh- LINC00941 cells had the longer OS compared with the control group (Fig. 2e). These data suggest that LINC00941 has a prometastatic effect on CRC progression. Moreover, LoVo-Sh- LINC00941 cells was downregulated presented a more epithelial morphology, while HCT-116-LINC00941 cells exhibited a more fibroblast-like shape compared with their corresponding controls (Fig. 2f, g), indicating that LINC00941 may promote CRC metastasis by activating EMT. Since EMT is crucial to CRC metastasis, and LINC00941 has been reported to play its oncogenic role in carcinogenesis by activating EMT [17, 20, 27, 28]. Therefore, we evaluated the effect of LINC00941 on EMT during CRC development. HCT-116-LINC00941 showed reduced mRNA and protein levels of ZO-1 and E-cadherin but increased mRNA and protein levels of Vimentin, Fibronectin, and Twist1 (Fig. 2h, i). In contrast, LoVo-Sh- LINC00941 cells showed increased mRNA and protein levels of ZO-1 and E-cadherin but decreased mRNA and protein levels of Vimentin, Fibronectin, and Twist1 (Fig. 2h, i), further confirming that LINC00941 promotes the invasion and migration of CRC cells at least partly through regulating EMT.

Fig. 2. LINC00941 promotes the migratory and invasive capacities of colorectal cancer cells.

a and b Transwell assay of LoVo or HCT-116 cells with the indicated treatment. c LoVo (Control and Sh-LINC00941 groups) and HCT-116 (Vector and LV-LINC00941 groups) cells were injected into nude mice via the tail vein, and the animals were sacrificed 8 weeks after injection. Representative HE staining of lung tissue samples is shown. d The number of lung metastatic foci observed in each group. *from the Kruskal–Wallis test, p < 0.05. e Kaplan–Meier curve depicting the overall survival of each group of nude mice. f and g Morphological changes induced by LINC00941 in LoVo and HCT-116 cells. Photographs using the 40× objective. Western blotting (h) and qRT-PCR assays (i) revealed the increased expression of epithelial markers and decreased expression of mesenchymal markers in LoVo-Sh-LINC00941 cells. In contrast, LINC00941 overexpression decreased the expression of epithelial markers and increased the expression of mesenchymal markers in HCT-116 cells. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

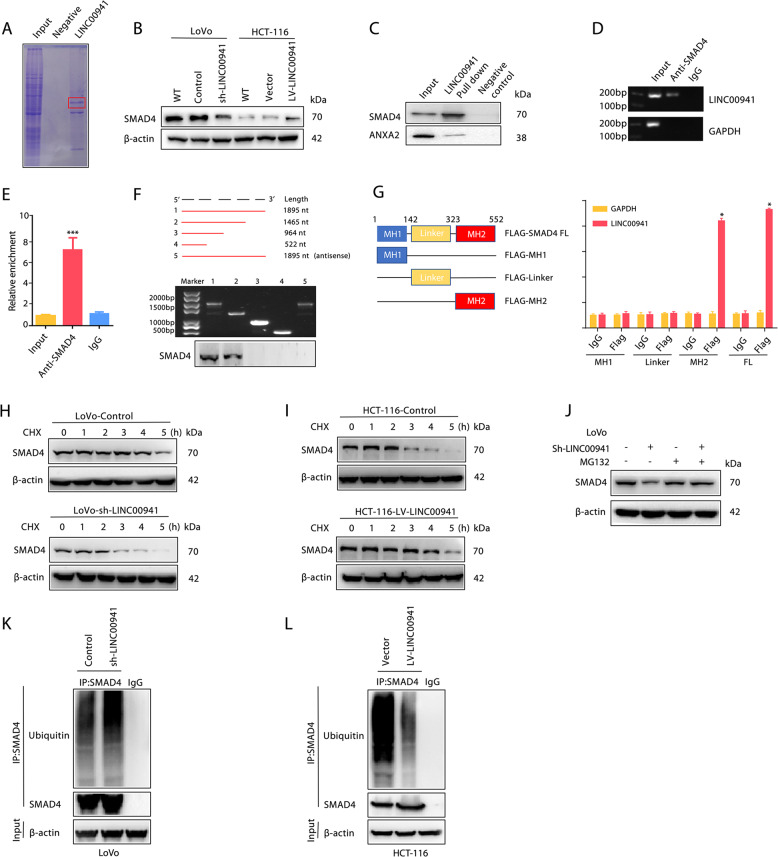

LINC00941 enhanced SMAD4 protein stability by suppressing its ubiquitination

LncRNAs usually affect gene expression by RNA-protein interactions [29, 30]. Therefore, we further examined proteins that could interact with LINC00941 to gain an in-depth mechanistic view of LINC00941-induced EMT in CRC metastasis. RNA pulldown assays followed by MS analysis (Table S3) showed that SMAD4 could specifically bind LINC00941 (Fig. 3a). Meanwhile, the expression of SMAD4 was downregulated in LoVo-Sh- LINC00941 cells and upregulated in HCT-116-LINC00941 cells (Fig. 3b). Consistently, as determined by Western blotting, SMAD4 enriched in the biotin-labeled sense LINC00941 group in an RNA pulldown assay (Fig. 3c). In addition, the interaction between LINC00941 and SMAD4 was further verified by agarose gel electrophoresis and RIP assays (Fig. 3d, e). To clarify the exact regions of LINC00941 and SMAD4 that bind, we constructed a series of truncated LINC00941 and SMAD4 constructs. Nucleotides 1465 to 1895 of LINC00941 could bind SMAD4, and the MH2 domain of SMAD4 and full-length (FL) SMAD4 could bind LINC00941 (Fig. 3f, g), indicating that LINC00941 is a binding partner of SMAD4. Cytoplasmic lncRNAs are usually responsible for the post-transcriptional regulation of protein modification [31]. LINC00941 suppression led to a decrease in the protein expression of SMAD4, whereas LINC00941 overexpression upregulated SMAD4 (Fig. 3b). Moreover, LINC00941 enhanced SMAD4 protein stability by prolonging its degradation half-life, as examined by cycloheximide (CHX) treatment (Fig. 3h, i), implying that LINC00941 can regulate SMAD4 via its protein degradation. As SMAD4 protein degradation is mediated by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, to pinpoint the in-depth mechanism of LINC00941-induced SMAD4 degradation, we treated LoVo-Sh-LINC00941 cells with a proteasome inhibitor (MG132). As determined by Western blot analysis, MG132 significantly restored SMAD4 protein levels in LoVo-Sh-LINC00941 cells (Fig. 3j), indicating that the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway is involved in LINC00941-induced SMAD4 degradation. To further validate this finding, we evaluated SMAD4 polyubiquitination in LINC00941-overexpressing and LINC00941-silenced CRC cells. As expected, SMAD4 ubiquitination was substantially decreased when LINC00941 was overexpressed, while SMAD4 ubiquitination was dramatically increased when LINC00941 was silenced (Fig. 3k, l). Taken together, these data indicated that LINC00941 can stabilize SMAD4 by suppressing its ubiquitination in CRC.

Fig. 3. LINC00941 promotes SMAD4 protein stability.

a Coomassie blue staining showing the results of an RNA pulldown assay with LINC00941. b The expression of SMAD4 in LoVo cells with or without LINC00941 knockdown or in HCT-116 cells with or without LINC00941 overexpression was determined by Western blotting. β-Actin was used as a loading control. c RNA pulldown assay with LINC00941, followed by Western blotting using the indicated antibodies. ANXA2 was used as a loading control. RNA-binding protein immunoprecipitation (RIP) assay for SMAD4 followed by agarose gel electrophoresis (d) and qRT-PCR (e) revealed that LINC00941 could bind the SMAD4 protein. f RNA pulldown assay for full-length or truncated LINC00941 and the indicated antisense probe, followed by Western blotting using the SMAD4 antibody. g RIP assay for Flag-tagged full-length or truncated SMAD4 protein, followed by qRT-PCR assay for LINC00941. The half-life of SMAD4 in LoVo cells with or without LINC00941 knockdown (h) or in HCT-116 cells with or without LINC00941 overexpression (i). Cells were treated with cycloheximide (CHX) for the indicated times; then, SMAD4 levels were analyzed by Western blotting. β-Actin was used as a loading control. j The expression of SMAD4 in LoVo cells with the indicated treatment was determined by Western blotting. The cells were treated with MG132 to inhibit the proteasome. Western blot analysis of ubiquitinated SMAD4 immunoprecipitated from LoVo cells with or without LINC00941 knockdown (k) or HCT-116 cells with or without LINC00941 overexpression (l). The cells were treated with MG132 to inhibit the proteasome. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

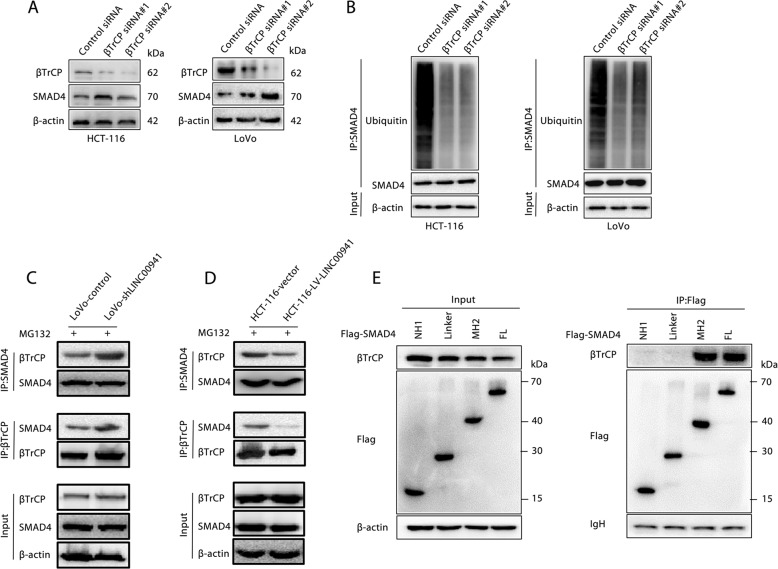

LINC00941 suppressed SMAD4 ubiquitination by competing with β-TrCP

Given that SMAD4 can be polyubiquitinated and degraded by β-TrCP [32–34], we evaluated the functional significance of β-TrCP in SMAD4 ubiquitination and degradation in CRC. Inhibiting β-TrCP expression in LoVo and HCT-116 cells can significantly increase SMAD4 protein expression levels (Fig. 4a). Similarly, after inhibiting the expression of β-TrCP in LoVo and HCT-116 cells, it was found by immunoprecipitation that the level of SMAD4 protein ubiquitination was significantly reduced (Fig. 4b). Next, we found that the absence of LINC00941 significantly increased the binding of SMAD4 and β-TrCP (Fig. 4c). Conversely, overexpression of LINC00941 can significantly inhibit the binding of SMAD4 and β-TrCP (Fig. 4d). Moreover, we further identified that the MH2 domain of SMAD4 and FL SMAD4 could bind β-TrCP (Fig. 4e), suggesting that β-TrCP controlled SMAD4 ubiquitination and degradation by binding the MH2 domain of SMAD4 and FL SMAD4. Given that the MH2 domain of SMAD4 and FL SMAD4 could bind LINC00941, we hypothesized that LINC00941 suppresses SMAD4 ubiquitination by competing with β-TrCP. As expected, competitive RNA pulldown assays further confirmed the competition between LINC00941 and β-TrCP (Fig. 4e). Collectively, these data confirmed that LINC00941 can enhance SMAD4 protein stability by competing with β-TrCP to prevent SMAD4 degradation.

Fig. 4. LINC00941 inhibited the ubiquitination of SMAD4 by blocking the binding of SMAD4 to βTrCP.

a The expression of SMAD4 and βTrCP in HCT-116 and LoVo cells transfected with LINC00941 or control siRNA was determined by Western blotting. β-Actin was used as a loading control. b Western blot analysis of ubiquitinated SMAD4 immunoprecipitated from HCT-116 and LoVo cells transfection with LINC00941 or control siRNA. Total lysates of LoVo cells with or without LINC00941 knockdown (c) or HCT-116 cells with or without LINC00941 overexpression (d) were subjected to IP with anti-SMAD4 or anti-βTrCP Ab, followed by Western blotting using the indicated antibodies (Abs). The cells were treated with MG132 to inhibit the proteasome. e Total lysates from HCT-116 cells overexpressing Flag-tagged full-length or truncated SMAD4 protein were subjected to IP with anti-Flag Ab, followed by Western blotting using the indicated antibodies (Abs). Ig heavy chain (H chain) was used as a loading control. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

LINC00941 was upregulated by TGF-β1 and associated with activation of the SMAD2/3 signaling pathway in metastatic CRC

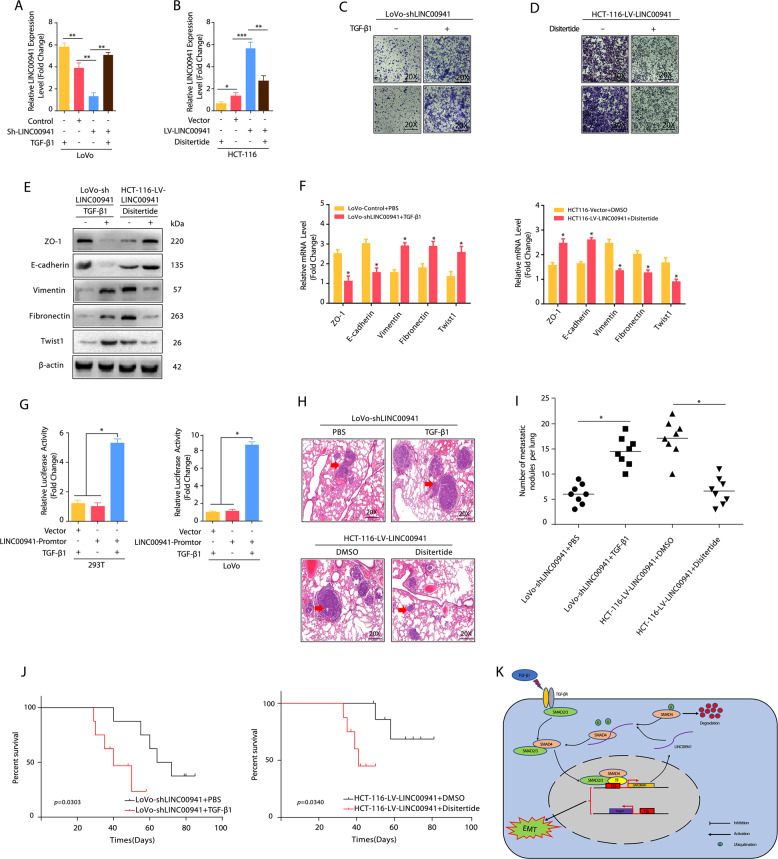

The TGF-β1/SMAD signaling pathway is a key regulator of EMT, and SMAD4 is an important cofactor that binds activated SMAD2 and SMAD3 to form oligomeric complexes that regulate the transcription of target genes [35–37]. Given that LINC00941 is important for SMAD4 stability and that LINC00941 contains predicted TGF-β1-targeting sites (http://www.gene-regulation.com/index2.html), we evaluated the role of LINC00941 in the TGF-β1/SMAD signaling pathways. The results showed that LINC00941 levels were significantly increased when LINC00941-silenced cells were treated with TGF-β1, whereas endogenous LINC0094 levels were significantly decreased when LINC00941-overexpressing cells were subjected to disitertide, an inhibitor of TGF-β1 (Fig. 5a, b). Consistently, treatment with TGF-β1 increased the invasive and migratory abilities of LINC00941-silenced cells compared with controls, while the inhibition of TGF-β1 receptor mitigated the invasive and migratory capacities of LINC00941-overpressing cells (Fig. 5c, d). In addition, LINC00941-overexpressing cells treated with disitertide showed increased mRNA and protein levels of ZO-1 and E-cadherin compared with controls (Fig. 5e, f). In contrast, LINC00941-silenced cells showed decreased mRNA and protein levels of ZO-1 and E-cadherin but increased mRNA and protein levels of Vimentin, Fibronectin, and Twist1 (Fig. 5e, f), further confirming that TGF-β1 is responsible for LINC00941-induced EMT. More importantly, luciferase reporter assays showed that the luciferase activity of the reporter construct was most significantly increased following treatment with TGF-β1 (Fig. 5g and Fig. S1G). Consistently, nude mice treated with LoVo-Sh- LINC00941 cells and TGF-β generated more lung metastatic nodules, while nude mice treated with HCT-116-LINC00941 cells and disitertide generated fewer lung metastatic nodules than their corresponding controls (Fig. 5h, i). In addition, nude mice treated with LoVo-Sh- LINC00941 cells and TGF-β had the shorter OS compared with the control groups and those treated with HCT-116-LINC00941 cells and disitertide had the longer OS compared with the control group (Fig. 5j). These data confirmed the strong interaction between TGF-β1 and LINC00941.

Fig. 5. TGF-β was necessary for LINC00941-induced promotion of metastasis.

The expression of LINC00941 in LoVo (a) and HCT-116 (b) cells with the indicated treatment was detected by qRT-PCR. Disitertide was used as a TGF-β1 receptor blocker. Transwell assay of LoVo-Sh-LINC00941 (c) or HCT-116-LINC00941 cells (d) with the indicated treatment. Disitertide was used as a TGF-β1 receptor blocker. Western blotting (e) and qRT-PCR assays (f) reveal the decreased expression of epithelial markers and increased expression of mesenchymal markers in LoVo-Sh-LINC00941 cells with TGF-β. In contrast, disitertide treatment increased the expression of epithelial markers and decreased the expression of mesenchymal markers in HCT-116-LINC00941 cells. g A luciferase reporter assay showed the regulation of LINC00941 transcription by TGF-β treatment in HEK 293 T and LoVo cells. P values are reported from the Student’s t test, *p < 0.05. h LoVo-Sh- LINC00941 cells and HCT-116-LINC00941 cells were injected into nude mice via the tail vein with TGF-β1 or Disitertide, and the animals were sacrificed 8 weeks after injection. Representative HE staining of lung tissue samples is shown. i The number of lung metastatic foci observed in each group. * from Kruskal–Wallis test, p < 0.05. j Kaplan–Meier curve depicting the overall survival of each group of nude mice. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. k Schematic model depicting that TGF-β-LINC00941-SMAD4 signaling promotes metastasis in CRC. The TGF-β/SMAD2/3 signaling pathway promotes LINC00941 expression, thereby increasing the protein stability of SMAD4. At the same time, LINC00941 can cause metastasis and invasion of colorectal cancer by activating EMT.

Discussion

In this study, we found that LINC00941 enrichment has a prometastatic effect on CRC. In addition, LINC00941 independently predicted poor outcomes in CRC. Furthermore, LINC00941 was shown to promote CRC metastasis via activation of the TGF-β1/SMAD2/3 signaling pathway, preventing SMAD4 protein degradation.

Epigenetic modifications by lncRNAs are one of the key regulatory mechanisms of CRC development [38, 39]. Our results appear to be similar to previous findings that LINC00941 behaves as a protumorigenic and prometastatic factor whose upregulation resulted in increased tumor growth and metastasis in HCC, LUAD, and GC [17–20]. Further in vitro and in vivo functional studies have provided striking evidence that LINC00941 promotes migratory and invasive capacities and activates EMT in CRC. LINC00941 positively accelerated the EMT process in CRC cells, as shown via the upregulation of key molecular markers of cell invasion and metastasis, Vimentin, Fibronectin, and Twist1, and the simultaneous downregulation of the main invasion suppressors E-cadherin and ZO-1 [37, 40]. LncRNAs usually exert their effects by RNA-protein interactions [29, 30]. To further explain the in-depth mechanisms of LINC00941-induced EMT in CRC metastasis, we investigated proteins that could specifically bind LINC00941 in CRC. Our results further confirmed that LINC00941 could directly bind SMAD4, a key factor in metastasis and an indispensable effector of TGF-β-induced EMT [41, 42]. SMAD4 silencing dramatically attenuated bone metastasis and prolonged survival in a BC nude mouse model [43]. In addition, SMAD4 could interact with SMAD3 to form a complex with SNAIL-1 that acted as a corepressor of E-cadherin promoters in BC during TGF-β-induced EMT [44]. Our results further confirmed that nucleotides 1465 to 1895 of LINC00941 could bind SMAD4 and that the MH2 domain of SMAD4 and FL SMAD4 could bind LINC00941, indicating that LINC00941 activates EMT and promotes CRC metastasis at least partly by interacting with SMAD4. In addition, our results further showed that LINC00941 enhanced SMAD4 protein stability by prolonging the degradation half-life, indicating that LINC00941 can regulate SMAD4 via protein degradation. It is well documented that SMAD4 can be polyubiquitinated and degraded by β-TrCP [32–34]. Therefore, we explored the functional significance of LINC00941 in SMAD4 ubiquitination. Our data demonstrated that β-TrCP could control SMAD4 ubiquitination and degradation by binding the MH2 domain of SMAD4 and FL SMAD4. Since the MH2 domain of SMAD4 and FL SMAD4 could bind LINC00941, we further explored whether there is a competitive relationship between LINC00941 and β-TrCP and confirmed that LINC00941 could enhance SMAD4 protein stability by competing with β-TrCP to prevent SMAD4 ubiquitination, thus prolonging its degradation half-life. However, when we depleted SMAD4 in LoVo and HCT-116 cell line and then downregulated or overexpressed LINC00941 expression respectively (Fig. S1A, B), the functional study showed that SMAD4 depletion did not completely block the role of LINC00941 in promoting the migration and invasion (Fig. S1C, D) as well as EMT of colorectal cancer cells (Fig. S1E, F), indicating there are other mechanisms for LINC00941 to promote the metastasis of cancer cells [45]. These results further suggest that the role of LINC00941 in promoting the migration and invasion of colorectal cancer cells depends on SMAD4, but SMAD4 wasn’t necessary for the promoting-metastasis effect of LINC00941.

Given that SMAD4 is essential to TGF-β1-induced EMT and that LINC00941 is important for SMAD4 stability, we therefore assessed the role of LINC00941 in TGF-β1-associated EMT. Our data revealed that in the presence of TGF-β1, the inhibitory effects of EMT caused by LINC00941 downregulation were significantly restored, suggesting that LINC00941 is an important mediator in TGF-β1/SMAD signaling during EMT in CRC. What’s more, we also found that endogenous LINC00941 levels were significantly decreased when LoVo cells were subjected to Disitertide which could revised by exogenously overexpressed LINC00941 by CMV promoter (Fig. S2A). In addition, LINC00941 levels were remarkably increased when HCT-116 cells were treated with TGFβ1 which could revised by transfecting LINC0094 Sh-RNA (Fig. S2B). Consistently, exogenously overexpressed LINC00941 by CMV promoter increased the invasive and migratory abilities of LoVo cells which treatment with Disitertide compared with controls, while downregulation of LINC00941 by Sh-RNA mitigated the invasive and migratory capacities of HCT-116 cells which treatment with TGF-β1 (Fig. S2C, D). Meanwhile, exogenously overexpressed LINC00941 decreased mRNA and protein levels of ZO-1 and E-cadherin but increased mRNA and protein levels of Vimentin, Fibronectin, and Twist1 in LoVo cells which treatment with Disitertide compared with corresponding controls (Fig. S2E, F). In contrast, downregulation of LINC00941 by Sh-RNA in HCT-116 cells which treatment with TGFβ1 could increase mRNA and protein levels of ZO-1 and E-cadherin and decrease mRNA and protein levels of Vimentin, Fibronectin and Twist1 compared with corresponding controls (Fig. S2E, F). Consistently, the xenograft model also showed that exogenously overexpressing LINC00941 in LoVo cells could increase the number of metastatic nodules in the lung when mice were treated by Disitertide. Meanwhile, with a weekly tail vein injection of TGF-β1, the number of metastatic nodules in the lung was dramatically decreased when LINC00941 was downregulated by Sh-RNA in HCT-116 cells (Fig. S2G, H). These results show that TGF-β signaling pathway, as an upstream regulatory mechanism, plays a crucial role in mediating LINC00941 to promote CRC metastasis. At the same time, LINC00941 also promotes the activation of TGF-β signaling pathway by increasing the stability of SMAD4, thus forming a positive feedback loop. Though the loss of SMAD4 through a high-frequency gene mutation is associated with CRC metastasis, accumulating evidence has demonstrated that activation of the TGF-β1/SMAD2/3 signaling pathway is important for CRC metastasis [46, 47]. Because SMAD4 is required to activate SMAD2 and SMAD3, we believe that LINC00941 regulates the SMAD4 prometastatic switch in CRC by activating TGF-β1/SMAD2/3 signaling.

In conclusion, our study confirmed that LINC00941 promotes the metastasis of CRC via activating the TGF-β/SMAD2/3 signaling pathway through preventing SMAD4 protein degradation (Fig. 5k), providing new insight into the mechanism of metastatic CRC and a novel potential therapeutic target for advanced CRC.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgments

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 61471181).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Edited by: RA Knight

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Nan Wu, Mingzuo Jiang, Haiming Liu, Yi Chu

Contributor Information

Yuying Han, Email: 254046797@qq.com.

Bing Xu, Email: xubing@nwu.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version of this article (10.1038/s41418-020-0596-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Okugawa Y, Grady WM, Goel A. Epigenetic alterations in colorectal cancer: emerging biomarkers. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:1204–.e1212. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dienstmann R, Vermeulen L, Guinney J, Kopetz S, Tejpar S, Tabernero J. Consensus molecular subtypes and the evolution of precision medicine in colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17:79–92. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fidler IJ. The pathogenesis of cancer metastasis: the ‘seed and soil’ hypothesis revisited. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:453–8. doi: 10.1038/nrc1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nieto MA, Huang RY, Jackson RA, Thiery JP. EMT: 2016. Cell. 2016;166:21–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thiery JP. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in tumour progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:442–54. doi: 10.1038/nrc822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guinney J, Dienstmann R, Wang X, de Reynies A, Schlicker A, Soneson C, et al. Consens Mol subtypes colorectal cancer. 2015;21:1350–6. doi: 10.1038/nm.3967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engreitz JM, Ollikainen N, Guttman M. Long non-coding RNAs: spatial amplifiers that control nuclear structure and gene expression. Nat Rev Mol cell Biol. 2016;17:756–70. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mercer TR, Dinger ME, Mattick JS. Long non-coding RNAs: insights into functions. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:155–9. doi: 10.1038/nrg2521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ponting CP, Oliver PL, Reik W. Evolution and functions of long noncoding RNAs. Cell. 2009;136:629–41. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang C, Shen S, Zheng X, Ye K, Sun Y, Lu Y, et al. Long noncoding RNA HAGLR acts as a microRNA-143-5p sponge to regulate epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastatic potential in esophageal cancer by regulating LAMP3. FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology 2019: fj201802543RR. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Aoshima T, Niida H, Suzuki T, Inoue Y, Miyazawa K, Kitagawa M, et al. Long noncoding RNA CASC11 promotes osteosarcoma metastasis by suppressing degradation of snail mRNA. Cancer Res. 2019;9:300–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 13.Li C. New functions of long noncoding RNAs during EMT and tumor progression. Cancer Res. 2019;79:3536–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sakai S, Ohhata T, Kitagawa K, Uchida C, Long Noncoding RNA. ELIT-1 acts as a Smad3 cofactor to facilitate TGFbeta/Smad signaling and promote epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Mol Cancer. 2019;79:2821–38. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-3210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu Y, Yang X, Chen Z, Tian L, Jiang G, Chen F, et al. m(6)A-Induc lncRNA RP11 triggers Dissem colorectal cancer cells via upregulation. Zeb1. Mol Cancer. 2019;18:87. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-1014-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang L, Wang R, Fang L, Ge X, Chen L, Zhou M, et al. HCP5 is a SMAD3-responsive long non-coding RNA that promotes lung adenocarcinoma metastasis via miR-203/SNAI axis. Theranostics. 2019;9:2460–74. doi: 10.7150/thno.31097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yan X, Zhang D, Wu W, Wu S, Qian J, Hao Y, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells promote hepatocarcinogenesis via lncRNA-MUF interaction with ANXA2 and miR-34a. Cancer Res. 2017;77:6704–16. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-1915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang L, Zhao H, Xu Y, Li J, Deng C, Deng Y, et al. Systematic identification of lincRNA-based prognostic biomarkers by integrating lincRNA expression and copy number variation in lung adenocarcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2019;144:1723–34. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luo C, Tao Y, Zhang Y, Zhu Y, Minyao DN, Haleem M, et al. Regulatory network analysis of high expressed long non-coding RNA LINC00941 in gastric cancer. Gene. 2018;662:103–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2018.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu H, Wu N, Zhang Z, Zhong X, Zhang H, Guo H, et al. Long non-coding RNA LINC00941 as a potential biomarker promotes the proliferation and metastasis of gastric cancer. Front Genet. 2019;10:5. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2019.00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen D, Wang K, Li X, Jiang M, Ni L, Xu B, et al. FOXK1 plays an oncogenic role in the development of esophageal cancer. Biochemical Biophysical Res Commun. 2017;494:88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.10.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou J, Yang J, Fan X, Hu S, Zhou F, Dong J, et al. Chaperone-mediated autophagy regulates proliferation by targeting RND3 in gastric cancer. Autophagy. 2016;12:515–28. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2015.1136770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.KM C, Z H, L M, J vD ZZ. Divers factors are involved maintaining X chromosome inactivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:16699–704. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107616108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Humphries B, Wang Z, Li Y, Jhan JR, Jiang Y, Yang C. ARHGAP18 downregulation by miR-200b suppresses metastasis of triple-negative breast cancer by enhancing activation of RhoA. Cancer Res. 2017;77:4051–64. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-3141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Z, Zhao Y, Smith E, Goodall GJ, Drew PA, Brabletz T, et al. Reversal and prevention of arsenic-induced human bronchial epithelial cell malignant transformation by microRNA-200b. Toxicological Sci: Off J Soc Toxicol. 2011;121:110–22. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfr029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li X, Jiang M, Chen D, Xu B, Wang R, Chu Y, et al. miR-148b-3p inhibits gastric cancer metastasis by inhibiting the Dock6/Rac1/Cdc42 axis. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2018;37:71. doi: 10.1186/s13046-018-0729-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boesch M, Spizzo G, Seeber A. Concise review: aggressive colorectal cancer: role of epithelial cell adhesion molecule in cancer stem cells and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Stem cells Transl Med. 2018;7:495–501. doi: 10.1002/sctm.17-0289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Robertis M, Poeta ML, Signori E, Fazio VM. Current understanding and clinical utility of miRNAs regulation of colon cancer stem cells. Semin cancer Biol. 2018;53:232–47. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2018.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McHugh CA, Chen CK, Chow A, Surka CF, Tran C, McDonel P, et al. The Xist lncRNA interacts directly with SHARP to silence transcription through HDAC3. Nature. 2015;521:232–6. doi: 10.1038/nature14443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gupta RA, Shah N, Wang KC, Kim J, Horlings HM, Wong DJ, et al. Long non-coding RNA HOTAIR reprograms chromatin state to promote cancer metastasis. Nature. 2010;464:1071–6. doi: 10.1038/nature08975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li C, Wang S, Xing Z, Lin A, Liang K, Song J.et al. A ROR1-HER3-lncRNA signal axis modulates the Hippo-YAP pathway to regulate bone metastasis. Nat Cell Biol. 2017;19:106–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Wan M, Tang Y, Tytler EM, Lu C, Jin B, Vickers SM, et al. Smad4 protein stability is regulated by ubiquitin ligase SCF beta-TrCP1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:14484–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400005200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wan M, Huang J, Jhala NC, Tytler EM, Yang L, Vickers SM, et al. SCF(beta-TrCP1) controls Smad4 protein stability in pancreatic cancer cells. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:1379–92. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62356-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang L, Wang N, Tang Y, Cao X, Wan M. Acute myelogenous leukemia-derived SMAD4 mutations target the protein to ubiquitin-proteasome degradation. Hum Mutat. 2006;27:897–905. doi: 10.1002/humu.20387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Conidi A, Cazzola S, Beets K, Coddens K, Collart C, Cornelis F, et al. Few Smad proteins and many Smad-interacting proteins yield multiple functions and action modes in TGFbeta/BMP signaling in vivo. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2011;22:287–300. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2011.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu F, Liu C, Zhou D, Zhang L. TGF-beta/SMAD Pathway and Its Regulation in Hepatic Fibrosis. The journal of histochemistry and cytochemistry: official journal of. Histochemistry Soc. 2016;64:157–67. doi: 10.1369/0022155415627681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yuan JH, Yang F, Wang F, Ma JZ, Guo YJ, Tao QF, et al. A long noncoding RNA activated by TGF-beta promotes the invasion-metastasis cascade in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:666–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Han D, Wang M, Ma N, Xu Y, Jiang Y, Gao X. Long noncoding RNAs: novel players in colorectal cancer. Cancer Lett. 2015;361:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim T, Croce CM. Long noncoding RNAs: undeciphered cellular codes encrypting keys of colorectal cancer pathogenesis. Cancer Lett. 2018;417:89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jung HY, Fattet L, Yang J. Molecular pathways: linking tumor microenvironment to epithelial-mesenchymal transition in metastasis. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:962–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Derynck R, Gelbart WM, Harland RM, Heldin CH, Kern SE, Massague J, et al. Nomenclature: vertebrate mediators of TGFbeta family signals. Cell. 1996;87:173. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81335-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hao Y, Baker D, Ten Dijke P. TGF-beta-mediated epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer metastasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:2767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Deckers M, van Dinther M, Buijs J, Que I, Lowik C, van der Pluijm G, et al. The tumor suppressor Smad4 is required for transforming growth factor beta-induced epithelial to mesenchymal transition and bone metastasis of breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2202–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vincent T, Neve EP, Johnson JR, Kukalev A, Rojo F, Albanell J, et al. A SNAIL1-SMAD3/4 transcriptional repressor complex promotes TGF-beta mediated epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat cell Biol. 2009;11:943–50. doi: 10.1038/ncb1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xinlong Y, Dongdong Z, Wei W, Shuheng W, Jingfeng Q, Yajing H, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells promote hepatocarcinogenesis via lncRNA-MUF interaction with ANXA2 and miR-34a. Cancer Res. 2017;77:6704–16. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-1915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yu J, Wu WK, Li X, He J, Li XX, Ng SS, et al. Novel recurrently mutated genes and a prognostic mutation signature in colorectal cancer. Gut. 2015;64:636–45. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li H, Zhang Z, Chen L, Sun X, Zhao Y, Guo Q. et al. Cytoplasmic Asporin promotes cell migration by regulating TGF-β/Smad2/3 pathway and indicates a poor prognosis in colorectal cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.